Should universities be worried about the increasing capabilities of AI?

If a piece of writing was 49 per cent written by AI, with the remaining 51 per cent written by a human, is this considered original work? Image: Unsplash/ Danial Igdery

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} Sarah Elaine Eaton

Michael mindzak.

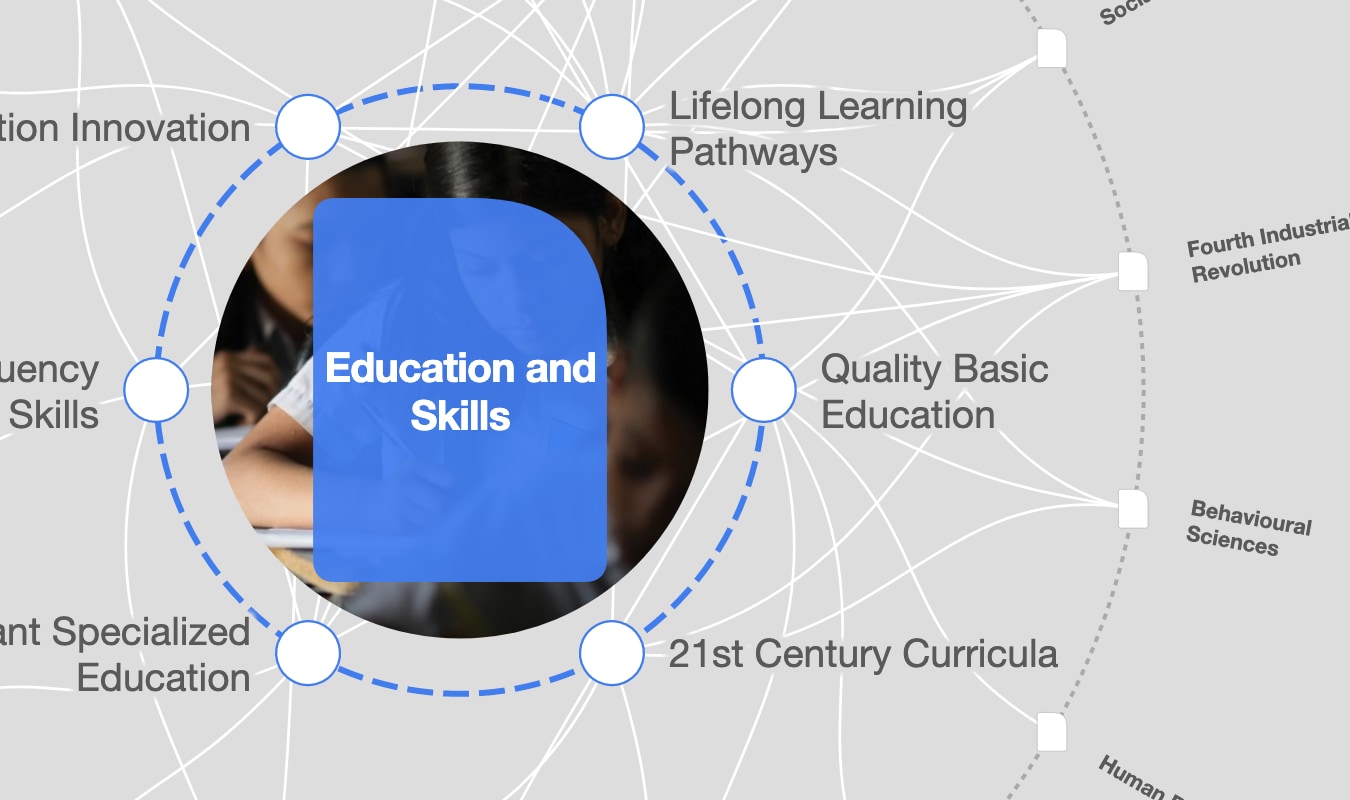

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Education, Gender and Work is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, education, gender and work.

- The use of technology in academic writing is already widespread, with teachers and students using AI-based tools to support the work they are doing.

- However, as AI becomes increasingly advanced, institutions need to properly define what can be defined as AI-assistance and what is plagiarism or cheating, writes an academic.

- For example, if a piece of writing was 49% written by AI, with the remaining 51% written by a human, is this considered original work?

The dramatic rise of online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic has spotlit concerns about the role of technology in exam surveillance — and also in student cheating .

Some universities have reported more cheating during the pandemic, and such concerns are unfolding in a climate where technologies that allow for the automation of writing continue to improve.

Over the past two years, the ability of artificial intelligence to generate writing has leapt forward significantly , particularly with the development of what’s known as the language generator GPT-3. With this, companies such as Google , Microsoft and NVIDIA can now produce “human-like” text .

AI-generated writing has raised the stakes of how universities and schools will gauge what constitutes academic misconduct, such as plagiarism . As scholars with an interest in academic integrity and the intersections of work, society and educators’ labour, we believe that educators and parents should be, at the very least, paying close attention to these significant developments .

AI & academic writing

The use of technology in academic writing is already widespread. For example, many universities already use text-based plagiarism detectors like Turnitin , while students might use Grammarly , a cloud-based writing assistant. Examples of writing support include automatic text generation, extraction, prediction, mining, form-filling, paraphrasing , translation and transcription.

Advancements in AI technology have led to new tools, products and services being offered to writers to improve content and efficiency . As these improve, soon entire articles or essays might be generated and written entirely by artificial intelligence . In schools, the implications of such developments will undoubtedly shape the future of learning, writing and teaching.

Misconduct concerns already widespread

Research has revealed that concerns over academic misconduct are already widespread across institutions higher education in Canada and internationally.

In Canada, there is little data regarding the rates of misconduct. Research published in 2006 based on data from mostly undergraduate students at 11 higher education institutions found 53 per cent reported having engaged in one or more instances of serious cheating on written work, which was defined as copying material without footnoting, copying material almost word for word, submitting work done by someone else, fabricating or falsifying a bibliography, submitting a paper they either bought or got from someone else for free.

Academic misconduct is in all likelihood under-reported across Canadian higher education institutions .

There are different types of violations of academic integrity, including plagiarism , contract cheating (where students hire other people to write their papers) and exam cheating, among others .

Unfortunately, with technology, students can use their ingenuity and entrepreneurialism to cheat. These concerns are also applicable to faculty members, academics and writers in other fields, bringing new concerns surrounding academic integrity and AI such as:

- If a piece of writing was 49 per cent written by AI, with the remaining 51 per cent written by a human, is this considered original work?

- What if an essay was 100 per cent written by AI, but a student did some of the coding themselves?

- What qualifies as “AI assistance” as opposed to “academic cheating”?

- Do the same rules apply to students as they would to academics and researchers?

We are asking these questions in our own research , and we know that in the face of all this, educators will be required to consider how writing can be effectively assessed or evaluated as these technologies improve.

Augmenting or diminishing integrity?

At the moment, little guidance, policy or oversight is available regarding technology, AI and academic integrity for teachers and educational leaders.

Over the past year, COVID-19 has pushed more students towards online learning — a sphere where teachers may become less familiar with their own students and thus, potentially, their writing.

While it remains impossible to predict the future of these technologies and their implications in education, we can attempt to discern some of the larger trends and trajectories that will impact teaching, learning and research.

Have you read?

Professor robot – why ai could soon be teaching in university classrooms, how digital technology is changing the university lecture, this is how university students can emerge from the pandemic stronger, technology & automation in education.

A key concern moving forward is the apparent movement towards the increased automation of education where educational technology companies offer commodities such as writing tools as proposed solutions for the various “problems” within education.

An example of this is automated assessment of student work, such as automated grading of student writing . Numerous commercial products already exist for automated grading, though the ethics of these technologies are yet to be fully explored by scholars and educators.

Overall, the traditional landscape surrounding academic integrity and authorship is being rapidly reshaped by technological developments. Such technological developments also spark concerns about a shift of professional control away from educators and ever-increasing new expectations of digital literacy in precarious working environments .

These complexities, concerns and questions will require further thought and discussion. Educational stakeholders at all levels will be required to respond and rethink definitions as well as values surrounding plagiarism, originality, academic ethics and academic labour in the very near future.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Emerging Technologies .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

Why regulating AI can be surprisingly straightforward, when teamed with eternal vigilance

Rahul Tongia

May 28, 2024

How venture capital is investing in AI in the top five global economies — and shaping the AI ecosystem

Piyush Gupta, Chirag Chopra and Ankit Kasare

May 24, 2024

What can we expect of next-generation generative AI models?

Andrea Willige

May 22, 2024

Solar storms hit tech equipment, and other technology news you need to know

Sebastian Buckup

May 17, 2024

Generative AI is trained on just a few of the world’s 7,000 languages. Here’s why that’s a problem – and what’s being done about it

Madeleine North

Critical minerals demand has doubled in the past five years – here are some solutions to the supply crunch

Emma Charlton

May 16, 2024

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Don’t Use A.I. to Cheat in School. It’s Better for Studying.

Generative A.I. tools can annotate long documents, make flashcards, and produce practice quizzes.

By Brian X. Chen

Hello! We’re back with another bonus edition of On Tech: A.I. , a pop-up newsletter that teaches you about artificial intelligence, how it works and how to use it.

Last week, I went over how to turn your chatbot into a life coach . Let’s now shift into an area where many have been experimenting with A.I. since last year: education.

Generative A.I.’s specialty is language — guessing which word comes next — and students quickly realized that they could use ChatGPT and other chatbots to write essays . That created an awkward situation in many classrooms. It turns out, it’s easy to get caught cheating with generative A.I. because it is prone to making stuff up , a phenomena known as “hallucinating.”

But generative A.I. can also be used as a study assistant. Some tools make highlights in long research papers and even answer questions about the material. Others can assemble study aids, like quizzes and flashcards.

One warning to keep in mind: When studying, it’s paramount that the information is correct, and to get the most accurate results, you should direct A.I. tools to focus on information from trusted sources rather than pull data from across the web. I’ll go over how to do that below.

First, let’s explore one of the most daunting studying tasks: reading and annotating long papers. Some A.I. tools, such as Humata.AI , Wordtune Read and various plug-ins inside ChatGPT, act as research assistants that will summarize documents for you.

I prefer Humata.AI because it answers your questions and shows highlights directly inside the source material, which allows you to double check for accuracy.

On the Humata.AI website, I uploaded a PDF of a scientific research paper on the accuracy of smartwatches in tracking cardio fitness. Then I clicked the “Ask” button and asked it how Garmin watches performed in the study. It scrolled down to the relevant part of the document mentioning Garmin, made highlights and answered my question.

Most interesting to me was when I asked the bot whether my understanding of the paper was correct — that on average, wearable devices like Garmins and Fitbits tracked cardio fitness fairly accurately, but there were some individuals whose results were very wrong. “Yes, you are correct,” the bot responded. It followed up with a summary of the study and listed the page numbers where this conclusion was mentioned.

Generative A.I. can also help with rote memorization. While any chatbot will generate flashcards or quizzes if you paste in the information that you’re studying, I decided to use ChatGPT because it includes plug-ins that generate study aids that pull from specific web articles or documents.

(Only subscribers who pay $20 a month for ChatGPT Plus can use plug-ins. We explained how to use them in a previous newsletter .)

I wanted ChatGPT to create flashcards for me to learn Chinese vocabulary words. To do this, I installed two plug-ins: Link Reader, which let me tell the bot to use data from a specific website, and MetaMentor, a plug-in that automatically generates flashcards.

In the ChatGPT dashboard, I selected both plug-ins. Then, I wrote this prompt:

Act as a tutor. I am a native English speaker learning Chinese. Take the vocabulary words and phrases from this link and create a set of flashcards for each: https://preply.com/en/blog/basic-chinese-words/

About five minutes later, the bot responded with a link where I could download the flashcards. They were exactly what I asked for.

Next, I wanted my tutor to quiz me. I told ChatGPT that I was studying for the written exam to get my motorcycle license in California. Again, using the Link Reader plug-in, I pasted a link to the California D.M.V.’s latest motorcycle handbook (an important step because traffic laws vary between states and rules are occasionally updated) and asked for a multiple-choice quiz.

The bot processed the information inside the handbook and produced a quiz, asking me five questions at a time.

Finally, to test my grasp of the subject, I directed ChatGPT to ask me questions without presenting multiple-choice answers. The bot adapted accordingly, and I aced the quiz.

I would have loved having these tools when I was in school. And probably would have earned better grades with them as study companions.

What’s next?

Next week, in the final installment of this how-to newsletter, we’ll take everything we’ve learned and apply it to enriching the time we spend with our families.

Brian X. Chen is the lead consumer technology writer for The Times. He reviews products and writes Tech Fix , a column about the social implications of the tech we use. Before joining The Times in 2011, he reported on Apple and the wireless industry for Wired. More about Brian X. Chen

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty/Staff

News and Media

- News & Media Home

- Research Stories

- School's In

- In the Media

You are here

What do ai chatbots really mean for students and cheating.

The launch of ChatGPT and other artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots has triggered an alarm for many educators, who worry about students using the technology to cheat by passing its writing off as their own. But two Stanford researchers say that concern is misdirected, based on their ongoing research into cheating among U.S. high school students before and after the release of ChatGPT.

“There’s been a ton of media coverage about AI making it easier and more likely for students to cheat,” said Denise Pope , a senior lecturer at Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE). “But we haven’t seen that bear out in our data so far. And we know from our research that when students do cheat, it’s typically for reasons that have very little to do with their access to technology.”

Pope is a co-founder of Challenge Success , a school reform nonprofit affiliated with the GSE, which conducts research into the student experience, including students’ well-being and sense of belonging, academic integrity, and their engagement with learning. She is the author of Doing School: How We Are Creating a Generation of Stressed-Out, Materialistic, and Miseducated Students , and coauthor of Overloaded and Underprepared: Strategies for Stronger Schools and Healthy, Successful Kids.

Victor Lee is an associate professor at the GSE whose focus includes researching and designing learning experiences for K-12 data science education and AI literacy. He is the faculty lead for the AI + Education initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning and director of CRAFT (Classroom-Ready Resources about AI for Teaching), a program that provides free resources to help teach AI literacy to high school students.

Here, Lee and Pope discuss the state of cheating in U.S. schools, what research shows about why students cheat, and their recommendations for educators working to address the problem.

Denise Pope

What do we know about how much students cheat?

Pope: We know that cheating rates have been high for a long time. At Challenge Success we’ve been running surveys and focus groups at schools for over 15 years, asking students about different aspects of their lives — the amount of sleep they get, homework pressure, extracurricular activities, family expectations, things like that — and also several questions about different forms of cheating.

For years, long before ChatGPT hit the scene, some 60 to 70 percent of students have reported engaging in at least one “cheating” behavior during the previous month. That percentage has stayed about the same or even decreased slightly in our 2023 surveys, when we added questions specific to new AI technologies, like ChatGPT, and how students are using it for school assignments.

Isn’t it possible that they’re lying about cheating?

Pope: Because these surveys are anonymous, students are surprisingly honest — especially when they know we’re doing these surveys to help improve their school experience. We often follow up our surveys with focus groups where the students tell us that those numbers seem accurate. If anything, they’re underreporting the frequency of these behaviors.

Lee: The surveys are also carefully written so they don’t ask, point-blank, “Do you cheat?” They ask about specific actions that are classified as cheating, like whether they have copied material word for word for an assignment in the past month or knowingly looked at someone else’s answer during a test. With AI, most of the fear is that the chatbot will write the paper for the student. But there isn’t evidence of an increase in that.

So AI isn’t changing how often students cheat — just the tools that they’re using?

Lee: The most prudent thing to say right now is that the data suggest, perhaps to the surprise of many people, that AI is not increasing the frequency of cheating. This may change as students become increasingly familiar with the technology, and we’ll continue to study it and see if and how this changes.

But I think it’s important to point out that, in Challenge Success’ most recent survey, students were also asked if and how they felt an AI chatbot like ChatGPT should be allowed for school-related tasks. Many said they thought it should be acceptable for “starter” purposes, like explaining a new concept or generating ideas for a paper. But the vast majority said that using a chatbot to write an entire paper should never be allowed. So this idea that students who’ve never cheated before are going to suddenly run amok and have AI write all of their papers appears unfounded.

But clearly a lot of students are cheating in the first place. Isn’t that a problem?

Pope: There are so many reasons why students cheat. They might be struggling with the material and unable to get the help they need. Maybe they have too much homework and not enough time to do it. Or maybe assignments feel like pointless busywork. Many students tell us they’re overwhelmed by the pressure to achieve — they know cheating is wrong, but they don’t want to let their family down by bringing home a low grade.

We know from our research that cheating is generally a symptom of a deeper, systemic problem. When students feel respected and valued, they’re more likely to engage in learning and act with integrity. They’re less likely to cheat when they feel a sense of belonging and connection at school, and when they find purpose and meaning in their classes. Strategies to help students feel more engaged and valued are likely to be more effective than taking a hard line on AI, especially since we know AI is here to stay and can actually be a great tool to promote deeper engagement with learning.

What would you suggest to school leaders who are concerned about students using AI chatbots?

Pope: Even before ChatGPT, we could never be sure whether kids were getting help from a parent or tutor or another source on their assignments, and this was not considered cheating. Kids in our focus groups are wondering why they can't use ChatGPT as another resource to help them write their papers — not to write the whole thing word for word, but to get the kind of help a parent or tutor would offer. We need to help students and educators find ways to discuss the ethics of using this technology and when it is and isn't useful for student learning.

Lee: There’s a lot of fear about students using this technology. Schools have considered putting significant amounts of money in AI-detection software, which studies show can be highly unreliable. Some districts have tried blocking AI chatbots from school wifi and devices, then repealed those bans because they were ineffective.

AI is not going away. Along with addressing the deeper reasons why students cheat, we need to teach students how to understand and think critically about this technology. For starters, at Stanford we’ve begun developing free resources to help teachers bring these topics into the classroom as it relates to different subject areas. We know that teachers don’t have time to introduce a whole new class, but we have been working with teachers to make sure these are activities and lessons that can fit with what they’re already covering in the time they have available.

I think of AI literacy as being akin to driver’s ed: We’ve got a powerful tool that can be a great asset, but it can also be dangerous. We want students to learn how to use it responsibly.

More Stories

⟵ Go to all Research Stories

Get the Educator

Subscribe to our monthly newsletter.

Stanford Graduate School of Education

482 Galvez Mall Stanford, CA 94305-3096 Tel: (650) 723-2109

- Contact Admissions

- GSE Leadership

- Site Feedback

- Web Accessibility

- Career Resources

- Faculty Open Positions

- Explore Courses

- Academic Calendar

- Office of the Registrar

- Cubberley Library

- StanfordWho

- StanfordYou

Improving lives through learning

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

- Work & Careers

- Life & Arts

Become an FT subscriber

Try unlimited access Only $1 for 4 weeks

Then $75 per month. Complete digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Cancel anytime during your trial.

- Global news & analysis

- Expert opinion

- Special features

- FirstFT newsletter

- Videos & Podcasts

- Android & iOS app

- FT Edit app

- 10 gift articles per month

Explore more offers.

Standard digital.

- FT Digital Edition

Premium Digital

Print + premium digital, ft professional, weekend print + standard digital, weekend print + premium digital.

Essential digital access to quality FT journalism on any device. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- Global news & analysis

- Exclusive FT analysis

- FT App on Android & iOS

- FirstFT: the day's biggest stories

- 20+ curated newsletters

- Follow topics & set alerts with myFT

- FT Videos & Podcasts

- 20 monthly gift articles to share

- Lex: FT's flagship investment column

- 15+ Premium newsletters by leading experts

- FT Digital Edition: our digitised print edition

- Weekday Print Edition

- Videos & Podcasts

- Premium newsletters

- 10 additional gift articles per month

- FT Weekend Print delivery

- Everything in Standard Digital

- Everything in Premium Digital

Complete digital access to quality FT journalism with expert analysis from industry leaders. Pay a year upfront and save 20%.

- 10 monthly gift articles to share

- Everything in Print

- Make and share highlights

- FT Workspace

- Markets data widget

- Subscription Manager

- Workflow integrations

- Occasional readers go free

- Volume discount

Terms & Conditions apply

Explore our full range of subscriptions.

Why the ft.

See why over a million readers pay to read the Financial Times.

International Edition

Subscribe or renew today

Every print subscription comes with full digital access

Science News

How chatgpt and similar ai will disrupt education.

Teachers are concerned about cheating and inaccurate information

Students are turning to ChatGPT for homework help. Educators have mixed feeling about the tool and other generative AI.

Glenn Harvey

Share this:

By Kathryn Hulick

April 12, 2023 at 7:00 am

“We need to talk,” Brett Vogelsinger said. A student had just asked for feedback on an essay. One paragraph stood out. Vogelsinger, a ninth grade English teacher in Doylestown, Pa., realized that the student hadn’t written the piece himself. He had used ChatGPT.

The artificial intelligence tool, made available for free late last year by the company OpenAI, can reply to simple prompts and generate essays and stories. It can also write code.

Within a week, it had more than a million users. As of early 2023, Microsoft planned to invest $10 billion into OpenAI , and OpenAI’s value had been put at $29 billion, more than double what it was in 2021.

It’s no wonder other tech companies have been racing to put out competing tools. Anthropic, an AI company founded by former OpenAI employees, is testing a new chatbot called Claude. Google launched Bard in early February, and the Chinese search company Baidu released Ernie Bot in March.

A lot of people have been using ChatGPT out of curiosity or for entertainment. I asked it to invent a silly excuse for not doing homework in the style of a medieval proclamation. In less than a second, it offered me: “Hark! Thy servant was beset by a horde of mischievous leprechauns, who didst steal mine quill and parchment, rendering me unable to complete mine homework.”

But students can also use it to cheat. ChatGPT marks the beginning of a new wave of AI, a wave that’s poised to disrupt education.

When Stanford University’s student-run newspaper polled students at the university, 17 percent said they had used ChatGPT on assignments or exams at the end of 2022. Some admitted to submitting the chatbot’s writing as their own. For now, these students and others are probably getting away with it. That’s because ChatGPT often does an excellent job.

“It can outperform a lot of middle school kids,” Vogelsinger says. He might not have known his student had used it, except for one thing: “He copied and pasted the prompt.”

The essay was still a work in progress, so Vogelsinger didn’t see it as cheating. Instead, he saw an opportunity. Now, the student and AI are working together. ChatGPT is helping the student with his writing and research skills.

“[We’re] color-coding,” Vogelsinger says. The parts the student writes are in green. The parts from ChatGPT are in blue. Vogelsinger is helping the student pick and choose a few sentences from the AI to expand on — and allowing other students to collaborate with the tool as well. Most aren’t turning to it regularly, but a few kids really like it. Vogelsinger thinks the tool has helped them focus their ideas and get started.

This story had a happy ending. But at many schools and universities, educators are struggling with how to handle ChatGPT and other AI tools.

In early January, New York City public schools banned ChatGPT on their devices and networks. Educators were worried that students who turned to it wouldn’t learn critical-thinking and problem-solving skills. They also were concerned that the tool’s answers might not be accurate or safe. Many other school systems in the United States and around the world have imposed similar bans.

Keith Schwarz, who teaches computer science at Stanford, said he had “switched back to pencil-and-paper exams,” so students couldn’t use ChatGPT, according to the Stanford Daily .

Yet ChatGPT and its kin could also be a great service to learners everywhere. Like calculators for math or Google for facts, AI can make writing that often takes time and effort much faster. With these tools, anyone can generate well-formed sentences and paragraphs. How could this change the way we teach and learn?

Who said what?

When prompted, ChatGPT can craft answers that sound surprisingly like those from a student. We asked middle school and high school students from across the country, all participants in our Science News Learning education program , to answer some basic science questions in two sentences or less. The examples throughout the story compare how students responded with how ChatGPT responded when asked to answer the question at the same grade level.

What effect do greenhouse gases have on the Earth?

Agnes b. | grade 11, harbor city international school, minn..

Greenhouse gases effectively trap heat from dissipating out of the atmosphere, increasing the amount of heat that remains near Earth in the troposphere.

Greenhouse gases trap heat in the Earth’s atmosphere, causing the planet to warm up and leading to climate change and its associated impacts like sea level rise, more frequent extreme weather events and shifts in ecosystems.

The good, bad and weird of ChatGPT

ChatGPT has wowed its users. “It’s so much more realistic than I thought a robot could be,” says Avani Rao, a sophomore in high school in California. She hasn’t used the bot to do homework. But for fun, she’s prompted it to say creative or silly things. She asked it to explain addition, for instance, in the voice of an evil villain.

Given how well it performs, there are plenty of ways that ChatGPT could level the playing field for students and others working in a second language or struggling with composing sentences. Since ChatGPT generates new, original material, its text is not technically plagiarism.

Students could use ChatGPT like a coach to help improve their writing and grammar, or even to explain subjects they find challenging. “It really will tutor you,” says Vogelsinger, who had one student come to him excited that ChatGPT had clearly outlined a concept from science class.

Educators could use ChatGPT to help generate lesson plans, activities or assessments — perhaps even personalized to address the needs or goals of specific students.

Xiaoming Zhai, an expert in science education at the University of Georgia in Athens, tested ChatGPT to see if it could write an academic paper . He was impressed with how easy it was to summarize knowledge and generate good writing using the tool. “It’s really amazing,” he says.

All of this sounds wonderful, but really big problems exist. Most worrying, ChatGPT and other similar tools can often get things very wrong. They don’t pull facts from databases. Rather, they are trained to generate new text that sounds natural. They remix language without understanding it, which can lead to glaring mistakes.

The news website CNET came under fire earlier this year for using AI to churn out dozens of articles, many of them packed with errors. In an early advertisement for the Bard chatbot, it made a factual error about the James Webb Space Telescope, incorrectly claiming that it had taken the very first picture of an exoplanet. And ChatGPT said in a conversation posted on Twitter that the fastest marine mammal was the peregrine falcon. A falcon, of course, is a bird and doesn’t live in the ocean.

ChatGPT is “confidently wrong,” says Casey Fiesler, an expert in the ethics of technology at the University of Colorado Boulder. “There are mistakes and bad information.” She has made multiple TikTok videos about the pitfalls of ChatGPT .

Most of ChatGPT’s training data come from before September 2021, and it does not provide sources for its information. If asked for sources, it makes them up, Fiesler revealed in one video . Zhai, who sees the tool as an assistant, discovered the exact same thing. When he asked ChatGPT for citations, it gave him sources that looked correct. But they didn’t actually exist.

Define the term biodiversity.

Dante a. | grade 10, clark magnet high school, calif..

Biodiversity refers to the variety of living species and ecosystems that exist in a particular region or on the planet as a whole. It encompasses the different genes, species and ecosystems that make up the natural world and the relationships between them.

Biodiversity refers to the variety of living organisms that inhabit the Earth and the ecosystems they form. It includes the diversity of species, genes and ecosystems, and is important for maintaining the balance of nature and sustaining life on our planet.

How ChatGPT works

ChatGPT’s mistakes make sense if you know how it works. “It doesn’t reason. It doesn’t have ideas. It doesn’t have thoughts,” explains Emily M. Bender, a computational linguist at the University of Washington in Seattle.

ChatGPT was developed using at least two types of machine learning. The primary type is a large language model based on an artificial neural network. Loosely inspired by how neurons in the brain interact, this computing architecture finds statistical patterns in vast amounts of data.

A language model learns to predict what words will come next in a sentence or phrase by churning through vast amounts of text. It places words and phrases into a multidimensional map that represents their relationships to one another. Words that tend to come together, like peanut butter and jelly, end up closer together in this map.

The size of an artificial neural network is measured in parameters. These internal values get tweaked as the model learns. In 2020, OpenAI released GPT-3. At the time, it was the biggest language model ever, containing 175 billion parameters. It had trained on text from the internet as well as digitized books and academic journals. Training text also included transcripts of dialog, essays, exams and more, says Sasha Luccioni, a Montreal-based researcher at Hugging Face, a company that builds AI tools.

OpenAI improved upon GPT-3 to create GPT-3.5. In early 2022, the company released a fine-tuned version of GPT-3.5 called InstructGPT. This time, OpenAI added a new type of machine learning. Called reinforcement learning with human feedback, it puts people into the training process. These workers check the AI’s output. Responses that people like get rewarded. Human feedback can also help reduce hurtful, biased or inappropriate responses. This fine-tuned language model powers freely available ChatGPT. As of March, paying users receive answers powered by GPT-4, a bigger language model.

During ChatGPT’s development, OpenAI added extra safety rules to the model. It will refuse to answer certain sensitive prompts or provide harmful information. But this step raises another issue: Whose values are programmed into the bot, including what it is — or is not — allowed to talk about?

OpenAI is not offering exact details about how it developed and trained ChatGPT. The company has not released its code or training data. This disappoints Luccioni because it means the tool can’t benefit from the perspectives of the larger AI community. “I’d like to know how it works so I can understand how to make it better,” she says.

When asked to comment on this story, OpenAI provided a statement from an unnamed spokesperson. “We made ChatGPT available as a research preview to learn from real-world use, which we believe is a critical part of developing and deploying capable, safe AI systems,” the statement said. “We are constantly incorporating feedback and lessons learned.” Indeed, some experimenters have gotten the bot to say biased or inappropriate things despite the safety rules. OpenAI has been patching the tool as these problems come up.

ChatGPT is not a finished product. OpenAI needs data from the real world. The people who are using it are the guinea pigs. Notes Bender: “You are working for OpenAI for free.”

What are black holes and where are they found?

Althea c. | grade 11, waimea high school, hawaii.

A black hole is a place in space where gravity is so strong that nothing, not even light, may come out.

Black holes are extremely dense regions in space where the gravity is so strong that not even light can escape, and they are found throughout the universe.

ChatGPT’s academic performance

How good is ChatGPT in an academic setting? Catherine Gao, a doctor and medical researcher at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in Chicago, is part of one team of researchers that is putting the tool to the test.

Gao and her colleagues gathered 50 real abstracts from research papers in medical journals and then, after providing the titles of the papers and the journal names, asked ChatGPT to generate 50 fake abstracts. The team asked people familiar with reading and writing these types of research papers to identify which were which .

“I was surprised by how realistic and convincing the generated abstracts were,” Gao says. The reviewers mistook roughly one-third of the AI-generated abstracts as human-generated.

In another study, Will Yeadon and colleagues tested whether AI tools could pass a college exam . Yeadon, a physics instructor at Durham University in England, picked an exam from a course that he teaches. The test asks students to write five short essays about physics and its history. Students have an average score of 71 percent, which he says is equivalent to an A in the United States.

Yeadon used the tool davinci-003, a close cousin of ChatGPT. It generated 10 sets of exam answers. Then Yeadon and four other teachers graded the answers using their typical standards. The AI also scored an average of 71 percent. Unlike the human students, though, it had no very low or very high marks. It consistently wrote well, but not excellently. For students who regularly get bad grades in writing, Yeadon says, it “will write a better essay than you.”

These graders knew they were looking at AI work. In a follow-up study, Yeadon plans to use work from the AI and students and not tell the graders whose is whose.

What is heat?

Precious a. | grade 6, canyon day junior high school, ariz..

Heat is the transfer of kinetic energy from one medium or object to another, or from an energy source to a medium or object through radiation, conduction and convection.

Heat is a type of energy that makes things warmer. It can be produced by burning something or through electricity.

Tools to check for cheating

When it’s unclear whether ChatGPT wrote something or not, other AI tools may help. These tools typically train on AI-generated text and sometimes human-generated text as well. They can tell you how likely it is that text was composed by an AI. Many of the existing tools were trained on older language models, but developers are working quickly to put out new, improved tools.

A company called Originality.ai sells access to a tool that trained on GPT-3. Founder Jon Gillham says that in a test of 10,000 samples of texts composed by models based on GPT-3, the tool tagged 94 percent of them correctly as AI-generated. When ChatGPT came out, his team tested a smaller set of 20 samples. Each only 500 words in length, these had been created by ChatGPT and other models based on GPT-3 and GPT-3.5. Here, Gillham says, the tool “tagged all of them as AI-generated. And it was 99 percent confident, on average.”

In late January 2023, OpenAI released its own free tool for spotting AI writing, cautioning that the tool was “not fully reliable.” The company is working to add watermarks to its AI text, which would tag the output as machine-generated, but doesn’t give details on how. Gillham describes one possible approach: Whenever it generates text, the AI ranks many different possible words for each position. If its developers told it to always choose the word ranked in third place rather than first place at specific points in its output, those words could act as a fingerprint, he says.

As AI writing tools improve, the tools to sniff them out will need to improve as well. Eventually, some sort of watermark might be the only way to sort out true authorship.

What is DNA and how is it organized?

Luke m. | grade 8, eastern york middle school, pa..

DNA, or deoxyribonucleic acid, is kept inside the cells of living things, where it holds instructions for the genetics of the organism it is inhabiting.

DNA is like a set of instructions that tells our cells what to do. It’s organized into structures called chromosomes, which contain all of the DNA in a cell.

ChatGPT and the future of writing

There’s no doubt we will soon have to adjust to a world in which computers can write for us. But educators have made these sorts of adjustments before. As high school student Rao points out, Google was once seen as a threat to education because it made it possible to look up facts instantly. Teachers adapted by coming up with teaching and testing materials that don’t depend as heavily on memorization.

Now that AI can generate essays and stories, teachers may once again have to rethink how they teach and test. Rao says: “We might have to shift our point of view about what’s cheating and what isn’t.”

Some teachers will prevent students from using AI by limiting access to technology. Right now, Vogelsinger says, teachers regularly ask students to write out answers or essays at home. “I think those assignments will have to change,” he says. But he hopes that doesn’t mean kids do less writing.

Teaching students to write without AI’s help will remain essential, agrees Zhai. That’s because “we really care about a student’s thinking,” he stresses. And writing is a great way to demonstrate thinking. Though ChatGPT can help a student organize their thoughts, it can’t think for them, he says.

Kids still learn to do basic math even though they have calculators (which are often on the phones they never leave home without), Zhai acknowledges. Once students have learned basic math, they can lean on a calculator for help with more complex problems.

In the same way, once students have learned to compose their thoughts, they could turn to a tool like ChatGPT for assistance with crafting an essay or story. Vogelsinger doesn’t expect writing classes to become editing classes, where students brush up AI content. He instead imagines students doing prewriting or brainstorming, then using AI to generate parts of a draft, and working back and forth to revise and refine from there.

Though he’s overwhelmed about the prospect of having to adapt his teaching to another new technology, he says he is “having fun” figuring out how to navigate the new tech with his students.

Rao doesn’t see AI ever replacing stories and other texts generated by humans. Why? “The reason those things exist is not only because we want to read it but because we want to write it,” she says. People will always want to make their voices heard.

More Stories from Science News on Tech

Reinforcement learning AI might bring humanoid robots to the real world

Should we use AI to resurrect digital ‘ghosts’ of the dead?

This robot can tell when you’re about to smile — and smile back

AI learned how to sway humans by watching a cooperative cooking game

Why large language models aren’t headed toward humanlike understanding

Could a rice-meat hybrid be what’s for dinner?

How do babies learn words? An AI experiment may hold clues

A new device let a man sense temperature with his prosthetic hand

Subscribers, enter your e-mail address for full access to the Science News archives and digital editions.

Not a subscriber? Become one now .

Universities say AI cheats can't be beaten, moving away from attempts to block AI

A number of universities have told a Senate inquiry it will be too difficult, if not impossible, to prevent students using AI to cheat assessments, and the institutions will have to change how they teach instead.

Key points:

- Universities have warned against banning AI technologies in academia

- Several say AI cheating in tests will be too difficult to stop, and it is more practical to change assessment methods

- The sector says the entire nature of teaching will have to change to ensure students continue to effectively learn

The tertiary sector is on the frontline of change coming from the rise in popularity of generative AI, technologies that can produce fresh content learned from massive databases of information.

Universities have widely reported experiences of students using AI to write essays or cheat assessments, with some returning to pen and paper testing to combat attempts to cheat.

In submissions to a Senate inquiry into the use of generative AI in education, a number now say it is not practical to consider attempting to ban the technologies from use in assessments.

Instead, some such as Monash University in Melbourne say the sector should "decriminalise" AI, and move away from banning it or attempting to detect its use.

"Beyond a desire to encourage responsible experimentation ... an important factor in taking this position is that detection of AI-generated content is unlikely to be feasible," its submission reads.

"Emerging evidence suggests that humans are not reliable in detecting AI-generated content.

"Equally, AI detection tools are non-transparent and unreliable in their testing and reporting of their own accuracy, and are likely to generate an intolerably high proportion of both false positives and false negatives."

Monash submitted that even if regulations were introduced to require AI tools to inject "watermarks" into their code to make AI detectable, other generative AI technologies could still be used to strip out those watermarks.

Instead, it and the nation's other largest universities under the Group of Eight (Go8) umbrella say the sector will have to change how it teaches and assesses students, using more oral or other supervised exams, practical assessments and the use of portfolios.

"Generative AI tools are rapidly evolving and will be part of our collective future – playing an important role in future workplaces and, most likely, our daily lives," tGo8 submitted.

"Entirely prohibiting the use of generative AI in higher education is therefore both impractical and undesirable."

The National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) has also expressed skepticism that universities would be able to completely manage AI misconduct — not only in assessment, but also in research.

"There is a real risk that AI applications will be considerably ahead of current research integrity processes that would detect problems or irregularities," the NTEU submitted.

"It may be that problematic research is not detected for some time, if at all, by which time there could be widespread ramifications."

New system needed to ensure students are actually learning

Universities have also given evidence that they have begun using generative AI across every aspect of what they do.

Monash University described how it has tested using AI "personalised course advisers" to help students navigate their degrees and classes, AI-powered mock job interviews for real positions and simulated customers or clients for learning.

"For example, in health education, the tool provides realistic ‘patients’ with detailed medical histories, personas, and varied willingness to share embarrassing medical details with learners who must put the work in to develop rapport with the patients to obtain relevant information in a realistic virtual clinical environment," it said.

As generative AI begins to be picked up at every part of the learning cycle, the tertiary education union warned that, over time, there was a risk universities may reach a point "where they can no longer assure the required learning has occurred in what they claim to be teaching".

"Teaching staff will need to continuously develop new methods of assessment that assess students at a level beyond the levels of AIs," it said.

The Queensland University of Technology said unless the nature of learning changed, there was a risk AI could promote "laziness and lack of independent thought".

"The possibility of a situation [arises] in which activities are created by the educators using AI, the learners use AI to create their responses, and the educators use AI to mark/grade and even give feedback," Queensland University of Technology wrote.

"At its most extreme, such a scenario suggests the question of who, if anyone, has learnt anything? And what was the purpose of the assessment?"

- X (formerly Twitter)

Related Stories

International students raise alarm about new ai detection tools being used by australian universities.

This university drama class asked Chat GPT to write a play for it — here's what it came up with

ChatGPT's class divide: Are public school bans on the AI tool giving private school kids an unfair edge?

- Access To Education

- Federal Government

- Government and Politics

The College Essay Is Dead

Nobody is prepared for how AI will transform academia.

Suppose you are a professor of pedagogy, and you assign an essay on learning styles. A student hands in an essay with the following opening paragraph:

The construct of “learning styles” is problematic because it fails to account for the processes through which learning styles are shaped. Some students might develop a particular learning style because they have had particular experiences. Others might develop a particular learning style by trying to accommodate to a learning environment that was not well suited to their learning needs. Ultimately, we need to understand the interactions among learning styles and environmental and personal factors, and how these shape how we learn and the kinds of learning we experience.

Pass or fail? A- or B+? And how would your grade change if you knew a human student hadn’t written it at all? Because Mike Sharples, a professor in the U.K., used GPT-3, a large language model from OpenAI that automatically generates text from a prompt, to write it. (The whole essay, which Sharples considered graduate-level, is available, complete with references, here .) Personally, I lean toward a B+. The passage reads like filler, but so do most student essays.

Sharples’s intent was to urge educators to “rethink teaching and assessment” in light of the technology, which he said “could become a gift for student cheats, or a powerful teaching assistant, or a tool for creativity.” Essay generation is neither theoretical nor futuristic at this point. In May, a student in New Zealand confessed to using AI to write their papers, justifying it as a tool like Grammarly or spell-check: “I have the knowledge, I have the lived experience, I’m a good student, I go to all the tutorials and I go to all the lectures and I read everything we have to read but I kind of felt I was being penalised because I don’t write eloquently and I didn’t feel that was right,” they told a student paper in Christchurch. They don’t feel like they’re cheating, because the student guidelines at their university state only that you’re not allowed to get somebody else to do your work for you. GPT-3 isn’t “somebody else”—it’s a program.

The world of generative AI is progressing furiously. Last week, OpenAI released an advanced chatbot named ChatGPT that has spawned a new wave of marveling and hand-wringing , plus an upgrade to GPT-3 that allows for complex rhyming poetry; Google previewed new applications last month that will allow people to describe concepts in text and see them rendered as images; and the creative-AI firm Jasper received a $1.5 billion valuation in October. It still takes a little initiative for a kid to find a text generator, but not for long.

The essay, in particular the undergraduate essay, has been the center of humanistic pedagogy for generations. It is the way we teach children how to research, think, and write. That entire tradition is about to be disrupted from the ground up. Kevin Bryan, an associate professor at the University of Toronto, tweeted in astonishment about OpenAI’s new chatbot last week: “You can no longer give take-home exams/homework … Even on specific questions that involve combining knowledge across domains, the OpenAI chat is frankly better than the average MBA at this point. It is frankly amazing.” Neither the engineers building the linguistic tech nor the educators who will encounter the resulting language are prepared for the fallout.

A chasm has existed between humanists and technologists for a long time. In the 1950s, C. P. Snow gave his famous lecture, later the essay “The Two Cultures,” describing the humanistic and scientific communities as tribes losing contact with each other. “Literary intellectuals at one pole—at the other scientists,” Snow wrote. “Between the two a gulf of mutual incomprehension—sometimes (particularly among the young) hostility and dislike, but most of all lack of understanding. They have a curious distorted image of each other.” Snow’s argument was a plea for a kind of intellectual cosmopolitanism: Literary people were missing the essential insights of the laws of thermodynamics, and scientific people were ignoring the glories of Shakespeare and Dickens.

The rupture that Snow identified has only deepened. In the modern tech world, the value of a humanistic education shows up in evidence of its absence. Sam Bankman-Fried, the disgraced founder of the crypto exchange FTX who recently lost his $16 billion fortune in a few days , is a famously proud illiterate. “I would never read a book,” he once told an interviewer . “I don’t want to say no book is ever worth reading, but I actually do believe something pretty close to that.” Elon Musk and Twitter are another excellent case in point. It’s painful and extraordinary to watch the ham-fisted way a brilliant engineering mind like Musk deals with even relatively simple literary concepts such as parody and satire. He obviously has never thought about them before. He probably didn’t imagine there was much to think about.

The extraordinary ignorance on questions of society and history displayed by the men and women reshaping society and history has been the defining feature of the social-media era. Apparently, Mark Zuckerberg has read a great deal about Caesar Augustus , but I wish he’d read about the regulation of the pamphlet press in 17th-century Europe. It might have spared America the annihilation of social trust .

These failures don’t derive from mean-spiritedness or even greed, but from a willful obliviousness. The engineers do not recognize that humanistic questions—like, say, hermeneutics or the historical contingency of freedom of speech or the genealogy of morality—are real questions with real consequences. Everybody is entitled to their opinion about politics and culture, it’s true, but an opinion is different from a grounded understanding. The most direct path to catastrophe is to treat complex problems as if they’re obvious to everyone. You can lose billions of dollars pretty quickly that way.

As the technologists have ignored humanistic questions to their peril, the humanists have greeted the technological revolutions of the past 50 years by committing soft suicide. As of 2017, the number of English majors had nearly halved since the 1990s. History enrollments have declined by 45 percent since 2007 alone. Needless to say, humanists’ understanding of technology is partial at best. The state of digital humanities is always several categories of obsolescence behind, which is inevitable. (Nobody expects them to teach via Instagram Stories.) But more crucially, the humanities have not fundamentally changed their approach in decades, despite technology altering the entire world around them. They are still exploding meta-narratives like it’s 1979, an exercise in self-defeat.

Read: The humanities are in crisis

Contemporary academia engages, more or less permanently, in self-critique on any and every front it can imagine. In a tech-centered world, language matters, voice and style matter, the study of eloquence matters, history matters, ethical systems matter. But the situation requires humanists to explain why they matter, not constantly undermine their own intellectual foundations. The humanities promise students a journey to an irrelevant, self-consuming future; then they wonder why their enrollments are collapsing. Is it any surprise that nearly half of humanities graduates regret their choice of major ?

The case for the value of humanities in a technologically determined world has been made before. Steve Jobs always credited a significant part of Apple’s success to his time as a dropout hanger-on at Reed College, where he fooled around with Shakespeare and modern dance, along with the famous calligraphy class that provided the aesthetic basis for the Mac’s design. “A lot of people in our industry haven’t had very diverse experiences. So they don’t have enough dots to connect, and they end up with very linear solutions without a broad perspective on the problem,” Jobs said . “The broader one’s understanding of the human experience, the better design we will have.” Apple is a humanistic tech company. It’s also the largest company in the world.

Despite the clear value of a humanistic education, its decline continues. Over the past 10 years, STEM has triumphed, and the humanities have collapsed . The number of students enrolled in computer science is now nearly the same as the number of students enrolled in all of the humanities combined.

And now there’s GPT-3. Natural-language processing presents the academic humanities with a whole series of unprecedented problems. Practical matters are at stake: Humanities departments judge their undergraduate students on the basis of their essays. They give Ph.D.s on the basis of a dissertation’s composition. What happens when both processes can be significantly automated? Going by my experience as a former Shakespeare professor, I figure it will take 10 years for academia to face this new reality: two years for the students to figure out the tech, three more years for the professors to recognize that students are using the tech, and then five years for university administrators to decide what, if anything, to do about it. Teachers are already some of the most overworked, underpaid people in the world. They are already dealing with a humanities in crisis. And now this. I feel for them.

And yet, despite the drastic divide of the moment, natural-language processing is going to force engineers and humanists together. They are going to need each other despite everything. Computer scientists will require basic, systematic education in general humanism: The philosophy of language, sociology, history, and ethics are not amusing questions of theoretical speculation anymore. They will be essential in determining the ethical and creative use of chatbots, to take only an obvious example.

The humanists will need to understand natural-language processing because it’s the future of language, but also because there is more than just the possibility of disruption here. Natural-language processing can throw light on a huge number of scholarly problems. It is going to clarify matters of attribution and literary dating that no system ever devised will approach; the parameters in large language models are much more sophisticated than the current systems used to determine which plays Shakespeare wrote, for example . It may even allow for certain types of restorations, filling the gaps in damaged texts by means of text-prediction models. It will reformulate questions of literary style and philology; if you can teach a machine to write like Samuel Taylor Coleridge, that machine must be able to inform you, in some way, about how Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote.

The connection between humanism and technology will require people and institutions with a breadth of vision and a commitment to interests that transcend their field. Before that space for collaboration can exist, both sides will have to take the most difficult leaps for highly educated people: Understand that they need the other side, and admit their basic ignorance. But that’s always been the beginning of wisdom, no matter what technological era we happen to inhabit.

- Newsletters

- Account Activating this button will toggle the display of additional content Account Sign out

A.I. Is Making It Easier Than Ever for Students to Cheat

Look out, educators. You’re about to confront a pernicious new challenge that is spreading, kudzu-like , into your student writing assignments: papers augmented with artificial intelligence.

The first online article generator debuted in 2005. Now, A.I.-generated text can now be found in novels , fake news articles and real news articles , marketing campaigns, and dozens of other written products. The tech is either free or cheap to use, which places it in the hands of anyone. And it’s probably already burrowing into America’s classrooms right now.

Using an A.I. program is not “plagiarism” in the traditional sense—there’s no previous work for the student to copy, and thus no original for teachers’ plagiarism detectors to catch. Instead, a student first feeds text from either a single or multiple sources into the program to begin the process. The program then generates content by using a set of parameters on a topic, which then can be personalized to the writer’s specifications. With a little bit of practice, a student can use AI to write his or her paper in a fraction of the time that it would normally take to write an essay.

I wanted to see what would happen if I fed an A.I. text generator like Sudowrite some sample texts for assignments. (Sudowrite is just one such program; I could name more, but I’d rather not make it even easier for students to cheat.) The results showed that teachers must be made aware of what is coming to their classrooms.

Say a student wanted to write an essay about U.S.-China policy and decided to use an A.I. program to speed along the process. I fed it the first few lines from a recent Pentagon report : “The PRC is increasingly clear in its ambitions and intentions. Beijing seeks to reshape the international order to better align with its authoritarian system and national interests, as a vital component of its strategy to achieve the ‘great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.’ ” The A.I. text generator provided these following sentences:

It is increasingly willing to disregard—or to actively undermine—existing international rules and norms when it feels its vital interests are at stake. The U.S. and its allies face a rapidly modernizing military, whose capabilities are growing rapidly, especially in the air and at sea. China has also made great strides in its development of cyber capabilities, and it is focused on the ability to degrade or disrupt critical U.S. military technology, as well as on targeting civilian infrastructure. In addition to being a challenge to the U.S. military and its allies, China’s activities in cyberspace have the potential to degrade U.S. political and economic institutions, and the global information infrastructure is at risk.

If a high school student turned that in verbatim, their teacher would probably suspect that there was something amiss. But if this were turned in at the undergraduate or graduate level, and especially if the student were to edit the text, it would be much harder to detect.

Or let’s say they need to write a paper about climate change. Here’s what came up when I fed Sudowrite the first few lines from an article on climate change impacts from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration website:

Though we often think about human-induced climate change as something that will happen in the future, it is an ongoing process. Ecosystems and communities in the United States and around the world are being impacted today.

It’s not particularly insightful, but it provides the A.I. program some basic building blocks. The artificial intelligence continued along this slightly edited line of reasoning:

The consensus view emerging from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and other respected assessments is that the planet is warming because of the accumulation of heat-trapping gases in the atmosphere caused by human activity. The level of scientific consensus that human activities are primarily responsible for climate change is like the consensus finding on smoking causing lung cancer.

The program had likely already been trained to know the term “climate change” was connected to the IPCC; by making certain inferences it could generate text which seemed like a reasonable extension of the idea.

What about ninth-grade English? Channeling my 14-year-old self, I wrote these lines:

“Romeo and Juliet” is a play that explores many different topics such as romance, betrayal, and tragedy. It has interesting characters that make it such a good story, even 400 years later.

The computer spat back this take (which I’ve edited slightly):

Romeo, the main character, is a very passionate and immature young man who is torn between his love for Rosaline and his love for Juliet. He is also very rash and desperate to get Juliet and will do almost anything to win her. His desperation for Juliet is an interesting trait and is one that the younger kids can relate to, as well as older adults with first crushes. Romeo is an interesting character and is very different from how kids would imagine him to be. But he is also a great inspiration, showing that love is worth fighting for.

Again, the A.I. program had been previously trained to know that Romeo and Juliet contained certain characters, themes, and plot elements. But what stood out to me was that the text was crafted at an appropriate writing level for a high schooler, who would be reading about these star-crossed lovers for the first time. The awkward phrasing and the syntax errors baked into the program make it seem convincing.

I’ve struggled to find the right analogy to describe this phenomenon. Is using A.I. to write graded papers like athletes taking performance-enhancing drugs? As a society and as a sporting culture, we’ve decided certain drugs are forbidden, as they provide the user unfair advantages. Further, the cocktail of drugs flowing through these competitors and malicious sports programs could cause real physical and psychological harm to the athletes themselves. Would individuals using AI in writing be likewise considered in the same boat—a cheat to the system providing undue advantages, which also creates harm in the long run by impeding writing skills?

Or might using A.I. be more like using performance-enhancing gear in sports, which is both acceptable and encouraged? To use another sports analogy, even beginner tennis players today use high-performance carbon composite rackets instead of 1960s-era wooden racket technology. Swimmers wear nylon and elastane suits and caps to reduce drag. Bikers have stronger, lighter bicycles than their counterparts used a generation ago. Baseball bats evolved from wood to aluminum and developed better grips; baseball mitts have become more specialized over the decades.

Numerous educators assert that A.I. is more like the former. They consider using these programs violate academic integrity. Georgetown University professor Lise Howard told me, “I do think it’s unethical and an academic violation to use AI to write paragraphs, because academic work is all about original writing.” Written assignments have two purposes, argues Ani Ross Grubb, part-time faculty member in the Carroll School of Management at Boston College: “First is to test the learning, understanding, and critical thinking skills of students. Second is to provide scaffolding to develop those skills. Having AI write your assignments would go against those goals.”

Certainly, one can argue that this topic has already been covered in university academic integrity codes. Using A.I. might open students to serious charges. For instance, American University indicates, “All papers and materials submitted for a course must be the student’s original work unless the sources are cited” while the University of Maryland similarly notes that it is prohibited to use dishonesty to “gain an unfair advantage, and/or using or attempting to use unauthorized materials, information, or study aids in any academic course or exercise.”

But some study aids are generally considered acceptable. When writing papers, it is perfectly fine to use grammar- and syntax-checking products standard on Microsoft Word and other document creating programs. Other A.I. programs like Grammarly help write better sentences and fix errors. Google Docs finishes sentences in drafts and emails.

So the border between using those kinds of assistive computer programs and full-on cheating remains fuzzy. Indeed, as Jade Wexler, associate professor of special education at the University of Maryland, noted, A.I. could be a valuable tool to help level the playing field for some students. “It goes back to teachers’ objectives and students’ needs,” she said. “There’s a fine balance making sure both of those are met.”

Thus there are two intertwined questions at work. First: Should institutions permit A.I.-enhanced writing? If the answer is no, then the second question is: How can professors detect it? After all, it’s unclear whether there’s a technical solution to keeping A.I. from worming into student papers. An educator’s up-to-date knowledge on relevant sources will be of limited utility since the verbiage has not been swiped from pre-existing texts.

Still, there may be ways to minimize these artificial enhancements. One is to codify at the institutional level what is acceptable and what is not; in July the Council of Europe took a few small steps, publishing new guidelines which begin to grapple with these new technologies creating fraud in education. Another would be to keep classes small and give individual attention to students. As Jessica Chiccehitto Hindman, associate professor of English at Northern Kentucky University, noted, “When a writing instructor is in a classroom situation where they are unable to provide individualized attention, the chance for students to phone it in—whether this is plagiarism, A.I., or just writing in a boring, uninvested way—goes up.” More in-class writing assignments—no screens allowed—could also help. Virginia Lee Strain, associate professor of English and director of the honors program at Loyola University Chicago, further argued, “AI is not a problem in the classroom when a student sits down with paper and pencil.”

But in many settings, more one-on-one time simply isn’t a realistic solution, especially at high schools or colleges with large classes. Educators juggle multiple classes and courses, and for them to get to know every student every semester isn’t going to happen.

A more aggressive stance would be for high schools and universities to explicitly declare using A.I. will be considered an academic violation—or at least update their honor codes to reflect what they believe is the right side of the line concerning academic integrity. That said, absent a mechanism to police students, it might paradoxically introduce students to a new way to generate papers faster.

Educators realize some large percentage of students will cheat or try to game the system to their advantage. But perhaps, as Hindman says, “if a professor is concerned that students are using plagiarism or AI to complete assignments, the assignments themselves are the problem, not the students or the AI.” If an educator is convinced that students are using these forbidden tools, he or she might consider using alternate means to generate grades such as assigning oral exams, group projects, and class presentations. Of course, as Hindman notes, “these types of high-impact learning practices are only feasible if you have a manageable number of students.”

AI is here to stay whether we like it or not. Provide unscrupulous students the ability to use these shortcuts without much capacity for the educator to detect them, combined with other crutches like outright plagiarism, and companies that sell papers, homework, and test answers, and it’s a recipe for—well, not disaster, but the further degradation of a type of assignment that has been around for centuries.

Future Tense is a partnership of Slate , New America , and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society.

Students Are Using AI Text Generators to Write Papers—Are They Cheating?

High school and college students are awakening to the grade-boosting possibilities of text-generating software. their teachers are struggling to catch up..

When West—not his real name—enrolled in college last year at the University of Rhode Island, he quickly realized that his professors expected a lot out of him. He had scheduled teaching, he had assignments, he had tests—and he didn’t want to devote an equal amount of time to all of them.

“I would like to say I’m pretty smart,” West said. So he turned to a homework-completion trick he’d started using the year before in high school. He logged into GPT-3, a text-generating tool developed by OpenAI, which can create written content from simple prompts. Trained on a vast corpus of preexisting language drawn from Wikipedia, Common Crawl, and other sources, GPT-3 is intended as a tool for automating writing tasks. But it’s also increasingly helping students like West avoid some of the tedium of academic writing and skip right to the fun part (being done).

“I was like, ‘Holy shit,’ you know, like, it was insane,” he said. “When people are children, they imagine that a machine can do their homework. And I just happened to stumble upon that machine.”

- TODAY Plaza

- Share this —

- Watch Full Episodes

- Read With Jenna

- Inspirational

- Relationships

- TODAY Table

- Newsletters

- Start TODAY

- Shop TODAY Awards

- Citi Concert Series

- Listen All Day

Follow today

More Brands

- On The Show

Teachers sound off on ChatGPT, the new AI tool that can write students’ essays for them

Teachers are talking about a new artificial intelligence tool called ChatGPT — with dread about its potential to help students cheat, and with anticipation over how it might change education as we know it.

On Nov. 30, research lab OpenAI released the free AI tool ChatGPT , a conversational language model that lets users type questions — “What is the Civil War?” or “Who was Leonardo da Vinci?” — and receive articulate, sophisticated and human-like responses in seconds. Ask it to solve complex math equations and it spits out the answer, sometimes with step-by-step explanations for how it got there.

According to a fact sheet sent to TODAY.com by OpenAI, ChatGPT can answer follow-up questions, correct false information, contextualize information and even acknowledge its own mistakes.

Some educators worry that students will use ChatGPT to get away with cheating more easily — especially when it comes to the five-paragraph essays assigned in middle and high school and the formulaic papers assigned in college courses. Compared with traditional cheating in which information is plagiarized by being copied directly or pasted together from other work, ChatGPT pulls content from all corners of the internet to form brand new answers that aren't derived from one specific source, or even cited.

Therefore, if you paste a ChatGPT-generated essay into the internet, you likely won't find it word-for-word anywhere else. This has many teachers spooked — even as OpenAI is trying to reassure educators .

"We don’t want ChatGPT to be used for misleading purposes in schools or anywhere else, so we’re already developing mitigations to help anyone identify text generated by that system," an OpenAI spokesperson tells TODAY.com "We look forward to working with educators on useful solutions, and other ways to help teachers and students benefit from artificial intelligence."

Still, #TeacherTok is weighing in about potential consequences in the classroom.

"So the robots are here and they’re going to be doing our students' homework,” educator Dan Lewer said in a TikTok video . “Great! As if teachers needed something else to be worried about.”

“If you’re a teacher, you need to know about this new (tool) that students can use to cheat in your class,” educational consultant Tyler Tarver said on TikTok .

“Kids can just tell it what they want it to do: Write a 500-word essay on ‘Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows,’” Tarver said. “This thing just starts writing it, and it looks legit.”

Taking steps to prevent cheating