UC Berkeley’s Premier Undergraduate Economics Journal

Joblessness: The Effects of Technology on U.S. Jobs

KAT BLESIE – NOVEMBER 22, 2018

The United States has often seen powerful people preaching the importance of working hard and staying busy. Our “bully pulpit” president Theodore Roosevelt once remarked that he’d rather risk wearing out than rusting out. Yet millions of people today find themselves at odds with this once uncompromised ideal of a steady, nine-to-five job that, for the baby-boomer generation, was all but guaranteed. The numbers speak for themselves, especially data from the manufacturing industry, a sector of the economy that is particularly useful to analyze because of the huge chunk that it has, historically, taken up of the U.S.’s economic pie. In the past 20 years the number of manufacturing jobs in the United States has dropped by almost 30%. Between 2000 and 2017 employment in manufacturing fell by 5.5 million jobs . Perhaps more surprisingly, the percentage of prime-age men who have no job and aren’t looking for a job has doubled since the 1970s —a statistic that suggests that our employment crisis is not just material in nature but psychological, as well.

Most economists agree that one of the leading propagators of this loss of U.S. jobs is the exponential growth of the use of technology in industry to increase efficiency and output. Economists have been nervous about technology’s effect on jobs for years—almost a century ago, in 1929, John Keynes warned that rapid technological change would reduce the demand for labor and lead to astounding rates of unemployment. Increasingly we see jobs that were once performed by humans being done by machines—cashiers have become ‘self-checkouts’, factory workers have been replaced (in some cases) by robots, and cars have begun to drive themselves. It’s true that technology makes jobs too—yet perhaps not at the rate that proponents of automation have advertised. 90 percent of workers today are employed in jobs that existed 100 years ago, and only five per cent of the jobs created in the twenty-year period between 1993 and 2013 came from high tech sectors. Researchers at Oxford university have predicted that, twenty years from now, machines may be able to perform half of all American jobs. The repercussions that America faces as a result of the decline in manufacturing run deeper than just unemployment—in many of the areas that were once hubs of industry we can now observe a surge of opioid use and opioid related deaths.

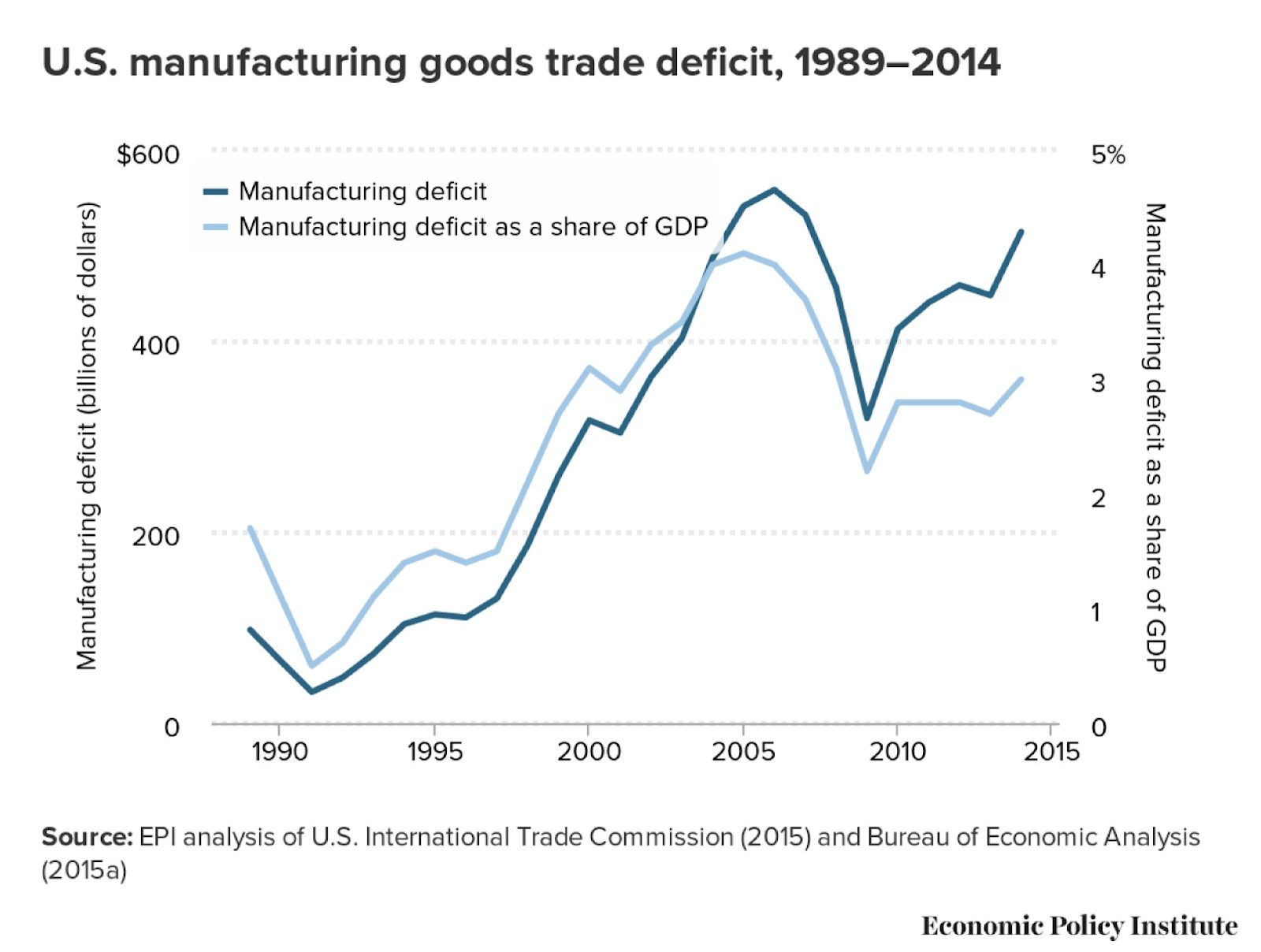

Of course technology isn’t the only threat impinging on US employment. In the realm of manufacturing, especially, recent economic analysis has shown that trade deficits might actually shoulder much of the blame for manufacturing job loss. The US Census Bureau reported in 2015 that the U.S. has run a goods trade deficit in every year since 1974, and with more than 75% of U.S. traded goods being manufactured goods, it’s manufacturing jobs that are taking the hit.

An interesting sub-group of scholars and economists has surfaced (or resurfaced) in the past ten years which argues that the end of jobs, for lack of a better phrase, might not actually be a bad thing. One such thinker, Peter Frase, says that we are conflating the way in which we earn income with the activities that give our life meaning. Frase, along with a select few, actually encourage the end of labor. Benjamin Hunnicutt, a historian at the University of Iowa, believes that America has an irrational belief in work for work’s sake . “Purpose, meaning, identity, fulfillment, creativity, autonomy—all these things that positive psychology has shown us to be necessary for well-being are absent in the average job.” This may all very well be true – but people need to eat, don’t they? Most jobless people today aren’t relishing in their newfound freedom to do meaningful, creative things—they are worrying about where their next meal will come from, and how they will pay their bills. Frase and his contemporaries are not the first to champion the cause of a leisure driven future—acclaimed 20 th century philosopher and social critic Bertrand Russell argued in his essay, In Praise of Idleness, that since the industrial revolution humans have theoretically been able to live with labor taking up a much smaller proportion of their lives than it does. In his words , “only a foolish asceticism, usually vicarious, makes us continue to insist on work in excessive quantities now that the need no longer exists”. These arguments are based on a viable—if not wildly optimistic—premise: why shouldn’t recent advancements in technology be used to shift the labor force, instead of replacing it? Why are we so scared of automation? What causes the cultural majority to identify more with the 19 th century Luddite than the 21 st century technocrat?

Well, perhaps it is the fact that the four most common jobs in American today (salesperson, cashier, office clerk, and food server) are all jobs at risk of being replaced entirely by automation. Some economists now argue that our increasingly inequitable wage structure has technology to thank. Prior to the 20 th century, technology introduced to the labor market was actually relatively unbiased with respect to skill level—in fact, the major technological invention of “interchangeable parts” that arose in the 20 th century put mainly skilled artisans out of work. So why do we see such a heavy skill bias in technology today? Many economists agree that rising returns to education and an increase in the supply of educated workers has caused this skill bias in technology. As MIT economist Daron Acemoglu writes , if we weren’t facing a skill bias then the aforementioned increase in supply of skilled labor would have depressed the skill premium. Instead, we’ve seen the relative demand for skilled labor rise. Acemoglu emphasizes that we should view technology as an endogenous factor—an outcome of decisions made in industries, rather than an outside force acting on the labor market. This in turn suggests that the increased skill bias of technology in the past 40 is a result of the increase in the supply of skilled workers that came about, in part, because of an increased Vietnam-era push for increased participation in higher education. Why? Because technical change moves towards more profitable areas. Profitability is determined by the price effect and the market size effect. As Acemoglu writes , ceteris paribus, it is most profitable to introduce capital that will be used by a larger number of workers, and, as a consequence of this, a labor market with a high proportion of skilled laborers makes the production of “skill-complementary” machines and technologies highly profitable,

Policy makers, heads of state, and others with a significant say in the direction of our economic policies acknowledge that many workers fear that they won’t have a job in a month, or a year, or a decade. In our most recent presidential race we saw the winning candidate run on a platform which focused, in part, on re-invigorating the automobile manufacturing industry (an industry in which jobs took a huge hit, in large part due to automation). Economic research institutes, perhaps with less self-motivated interests, have also highlighted increasing automation as a problem area of interest. McKinsey Global Institute, in a 2017 executive briefing, proposed several potential steps to take in our increasingly digitized and automated world. They included implementing a universal basic income, improving STEM learning in young children, and incentivizing corporations to treat human capital like they would any other capital. It remains to be seen if, and to what degree, technological innovation will widen the gap between skilled and unskilled workers, although if returns to education continue to increase, and Acemoglu’s analysis proves correct, it seems likely that technology will continue to put lower-skilled jobs at risk of replacement.

Featured Image Source: New Statesman

Disclaimer: The views published in this journal are those of the individual authors or speakers and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of Berkeley Economic Review staff, the UC Berkeley Economics Department and faculty, or the University of California, Berkeley in general.

Share this article:

Related Articles

Partisanship and COVID-19 Response

Interview with Christopher Walters

The Macroeconomics of Happiness: A Case Study of Bhutan

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

subscribe to our Monthly Newsletter!

How a New Jobless Era Will Transform America

The Great Recession may be over, but this era of high joblessness is probably just beginning. Before it ends, it will likely change the life course and character of a generation of young adults. It will leave an indelible imprint on many blue-collar men. It could cripple marriage as an institution in many communities. It may already be plunging many inner cities into a despair not seen for decades. Ultimately, it is likely to warp our politics, our culture, and the character of our society for years to come.

H ow should we characterize the economic period we have now entered? After nearly two brutal years, the Great Recession appears to be over, at least technically. Yet a return to normalcy seems far off. By some measures, each recession since the 1980s has retreated more slowly than the one before it. In one sense, we never fully recovered from the last one, in 2001: the share of the civilian population with a job never returned to its previous peak before this downturn began, and incomes were stagnant throughout the decade. Still, the weakness that lingered through much of the 2000s shouldn’t be confused with the trauma of the past two years, a trauma that will remain heavy for quite some time.

The unemployment rate hit 10 percent in October, and there are good reasons to believe that by 2011, 2012, even 2014, it will have declined only a little. Late last year, the average duration of unemployment surpassed six months, the first time that has happened since 1948, when the Bureau of Labor Statistics began tracking that number. As of this writing, for every open job in the U.S., six people are actively looking for work.

All of these figures understate the magnitude of the jobs crisis. The broadest measure of unemployment and underemployment (which includes people who want to work but have stopped actively searching for a job, along with those who want full-time jobs but can find only part-time work) reached 17.4 percent in October, which appears to be the highest figure since the 1930s. And for large swaths of society—young adults, men, minorities—that figure was much higher (among teenagers, for instance, even the narrowest measure of unemployment stood at roughly 27 percent). One recent survey showed that 44 percent of families had experienced a job loss, a reduction in hours, or a pay cut in the past year.

There is unemployment, a brief and relatively routine transitional state that results from the rise and fall of companies in any economy, and there is unemployment —chronic, all-consuming. The former is a necessary lubricant in any engine of economic growth. The latter is a pestilence that slowly eats away at people, families, and, if it spreads widely enough, the fabric of society. Indeed, history suggests that it is perhaps society’s most noxious ill.

The worst effects of pervasive joblessness—on family, politics, society—take time to incubate, and they show themselves only slowly. But ultimately, they leave deep marks that endure long after boom times have returned. Some of these marks are just now becoming visible, and even if the economy magically and fully recovers tomorrow, new ones will continue to appear. The longer our economic slump lasts, the deeper they’ll be.

If it persists much longer, this era of high joblessness will likely change the life course and character of a generation of young adults—and quite possibly those of the children behind them as well. It will leave an indelible imprint on many blue-collar white men—and on white culture. It could change the nature of modern marriage, and also cripple marriage as an institution in many communities. It may already be plunging many inner cities into a kind of despair and dysfunction not seen for decades. Ultimately, it is likely to warp our politics, our culture, and the character of our society for years.

Since last spring, when fears of economic apocalypse began to ebb, we’ve been treated to an alphabet soup of predictions about the recovery. Various economists have suggested that it might look like a V (a strong and rapid rebound), a U (slower), a W (reflecting the possibility of a double-dip recession), or, most alarming, an L (no recovery in demand or jobs for years: a lost decade). This summer, with all the good letters already taken, the former labor secretary Robert Reich wrote on his blog that the recovery might actually be shaped like an X (the imagery is elusive, but Reich’s argument was that there can be no recovery until we find an entirely new model of economic growth).

No one knows what shape the recovery will take. The economy grew at an annual rate of 2.2 percent in the third quarter of last year, the first increase since the second quarter of 2008. If economic growth continues to pick up, substantial job growth will eventually follow. But there are many reasons to doubt the durability of the economic turnaround, and the speed with which jobs will return.

Historically, financial crises have spawned long periods of economic malaise, and this crisis, so far, has been true to form. Despite the bailouts, many banks’ balance sheets remain weak; more than 140 banks failed in 2009. As a result, banks have kept lending standards tight, frustrating the efforts of small businesses—which have accounted for almost half of all job losses—to invest or rehire. Exports seem unlikely to provide much of a boost; although China, India, Brazil, and some other emerging markets are growing quickly again, Europe and Japan—both major markets for U.S. exports—remain weak. And in any case, exports make up only about 13 percent of total U.S. production; even if they were to grow quickly, the impact would be muted.

Most recessions end when people start spending again, but for the foreseeable future, U.S. consumer demand is unlikely to propel strong economic growth. As of November, one in seven mortgages was delinquent, up from one in 10 a year earlier. As many as one in four houses may now be underwater, and the ratio of household debt to GDP, about 65 percent in the mid-1990s, is roughly 100 percent today. It is not merely animal spirits that are keeping people from spending freely (though those spirits are dour). Heavy debt and large losses of wealth have forced spending onto a lower path.

So what is the engine that will pull the U.S. back onto a strong growth path? That turns out to be a hard question. The New York Times columnist Paul Krugman, who fears a lost decade, said in a lecture at the London School of Economics last summer that he has “no idea” how the economy could quickly return to strong, sustainable growth. Mark Zandi, the chief economist at Moody’s Economy.com, told the Associated Press last fall, “I think the unemployment rate will be permanently higher, or at least higher for the foreseeable future. The collective psyche has changed as a result of what we’ve been through. And we’re going to be different as a result.”

One big reason that the economy stabilized last summer and fall is the stimulus; the Congressional Budget Office estimates that without the stimulus, growth would have been anywhere from 1.2 to 3.2 percentage points lower in the third quarter of 2009. The stimulus will continue to trickle into the economy for the next couple of years, but as a concentrated force, it’s largely spent. Christina Romer, the chair of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, said last fall, “By mid-2010, fiscal stimulus will likely be contributing little to further growth,” adding that she didn’t expect unemployment to fall significantly until 2011. That prediction has since been echoed, more or less, by the Federal Reserve and Goldman Sachs.

The economy now sits in a hole more than 10 million jobs deep—that’s the number required to get back to 5 percent unemployment, the rate we had before the recession started, and one that’s been more or less typical for a generation. And because the population is growing and new people are continually coming onto the job market, we need to produce roughly 1.5 million new jobs a year—about 125,000 a month—just to keep from sinking deeper.

Even if the economy were to immediately begin producing 600,000 jobs a month—more than double the pace of the mid-to-late 1990s, when job growth was strong—it would take roughly two years to dig ourselves out of the hole we’re in. The economy could add jobs that fast, or even faster—job growth is theoretically limited only by labor supply, and a lot more labor is sitting idle today than usual. But the U.S. hasn’t seen that pace of sustained employment growth in more than 30 years. And given the particulars of this recession, matching idle workers with new jobs—even once economic growth picks up—seems likely to be a particularly slow and challenging process.

The construction and finance industries, bloated by a decade-long housing bubble, are unlikely to regain their former share of the economy, and as a result many out-of-work finance professionals and construction workers won’t be able to simply pick up where they left off when growth returns—they’ll need to retrain and find new careers. (For different reasons, the same might be said of many media professionals and auto workers.) And even within industries that are likely to bounce back smartly, temporary layoffs have generally given way to the permanent elimination of jobs, the result of workplace restructuring. Manufacturing jobs have of course been moving overseas for decades, and still are; but recently, the outsourcing of much white-collar work has become possible. Companies that have cut domestic payrolls to the bone in this recession may choose to rebuild them in Shanghai, Guangzhou, or Bangalore, accelerating off-shoring decisions that otherwise might have occurred over many years.

New jobs will come open in the U.S. But many will have different skill requirements than the old ones. “In a sense,” says Gary Burtless, a labor economist at the Brookings Institution, “every time someone’s laid off now, they need to start all over. They don’t even know what industry they’ll be in next.” And as a spell of unemployment lengthens, skills erode and behavior tends to change, leaving some people unqualified even for work they once did well.

Ultimately, innovation is what allows an economy to grow quickly and create new jobs as old ones obsolesce and disappear. Typically, one salutary side effect of recessions is that they eventually spur booms in innovation. Some laid-off employees become entrepreneurs, working on ideas that have been ignored by corporate bureaucracies, while sclerotic firms in declining industries fail, making way for nimbler enterprises. But according to the economist Edmund Phelps, the innovative potential of the U.S. economy looks limited today. In a recent Harvard Business Review article , he and his co-author, Leo Tilman, argue that dynamism in the U.S. has actually been in decline for a decade; with the housing bubble fueling easy (but unsustainable) growth for much of that time, we just didn’t notice. Phelps and Tilman finger several culprits: a patent system that’s become stifling; an increasingly myopic focus among public companies on quarterly results, rather than long-term value creation; and, not least, a financial industry that for a generation has focused its talent and resources not on funding business innovation, but on proprietary trading, regulatory arbitrage, and arcane financial engineering. None of these problems is likely to disappear quickly. Phelps, who won a Nobel Prize for his work on the “natural” rate of unemployment, believes that until they do disappear, the new floor for unemployment is likely to be between 6.5 percent and 7.5 percent, even once “recovery” is complete.

It’s likely, then, that for the next several years or more, the jobs environment will more closely resemble today’s environment than that of 2006 or 2007—or for that matter, the environment to which we were accustomed for a generation. Heidi Shierholz, an economist at the Economic Policy Institute, notes that if the recovery follows the same basic path as the last two (in 1991 and 2001), unemployment will stand at roughly 8 percent in 2014.

“We haven’t seen anything like this before: a really deep recession combined with a really extended period, maybe as much as eight years, all told, of highly elevated unemployment,” Shierholz told me. “We’re about to see a big national experiment on stress.”

“I’m definitely seeing a lot of the older generation saying, ‘Oh, this [recession] is so awful,’” Robert Sherman, a 2009 graduate of Syracuse University, told The New York Times in July. “But my generation isn’t getting as depressed and uptight.” Sherman had recently turned down a $50,000-a-year job at a consulting firm, after careful deliberation with his parents, because he hadn’t connected well with his potential bosses. Instead he was doing odd jobs and trying to get a couple of tech companies off the ground. “The economy will rebound,” he said.

Over the past two generations, particularly among many college grads, the 20s have become a sort of netherworld between adolescence and adulthood. Job-switching is common, and with it, periods of voluntary, transitional unemployment. And as marriage and parenthood have receded farther into the future, the first years after college have become, arguably, more carefree. In this recession, the term funemployment has gained some currency among single 20-somethings, prompting a small raft of youth-culture stories in the Los Angeles Times and San Francisco Weekly , on Gawker, and in other venues.

Most of the people interviewed in these stories seem merely to be trying to stay positive and make the best of a bad situation. They note that it’s a good time to reevaluate career choices; that since joblessness is now so common among their peers, it has lost much of its stigma; and that since they don’t have mortgages or kids, they have flexibility, and in this respect, they are lucky. All of this sounds sensible enough—it is intuitive to think that youth will be spared the worst of the recession’s scars.

But in fact a whole generation of young adults is likely to see its life chances permanently diminished by this recession. Lisa Kahn, an economist at Yale, has studied the impact of recessions on the lifetime earnings of young workers. In one recent study, she followed the career paths of white men who graduated from college between 1979 and 1989. She found that, all else equal, for every one-percentage-point increase in the national unemployment rate, the starting income of new graduates fell by as much as 7 percent; the unluckiest graduates of the decade, who emerged into the teeth of the 1981–82 recession, made roughly 25 percent less in their first year than graduates who stepped into boom times.

But what’s truly remarkable is the persistence of the earnings gap. Five, 10, 15 years after graduation, after untold promotions and career changes spanning booms and busts, the unlucky graduates never closed the gap. Seventeen years after graduation, those who had entered the workforce during inhospitable times were still earning 10 percent less on average than those who had emerged into a more bountiful climate. When you add up all the earnings losses over the years, Kahn says, it’s as if the lucky graduates had been given a gift of about $100,000, adjusted for inflation, immediately upon graduation—or, alternatively, as if the unlucky ones had been saddled with a debt of the same size.

When Kahn looked more closely at the unlucky graduates at mid-career, she found some surprising characteristics. They were significantly less likely to work in professional occupations or other prestigious spheres. And they clung more tightly to their jobs: average job tenure was unusually long. People who entered the workforce during the recession “didn’t switch jobs as much, and particularly for young workers, that’s how you increase wages,” Kahn told me. This behavior may have resulted from a lingering risk aversion, born of a tough start. But a lack of opportunities may have played a larger role, she said: when you’re forced to start work in a particularly low-level job or unsexy career, it’s easy for other employers to dismiss you as having low potential. Moving up, or moving on to something different and better, becomes more difficult.

“Graduates’ first jobs have an inordinate impact on their career path and [lifetime earnings],” wrote Austan Goolsbee , now a member of President Obama’s Council of Economic Advisers, in The New York Times in 2006. “People essentially cannot close the wage gap by working their way up the company hierarchy. While they may work their way up, the people who started above them do, too. They don’t catch up.” Recent research suggests that as much as two-thirds of real lifetime wage growth typically occurs in the first 10 years of a career. After that, as people start families and their career paths lengthen and solidify, jumping the tracks becomes harder.

This job environment is not one in which fast-track jobs are plentiful, to say the least. According to the National Association of Colleges and Employers, job offers to graduating seniors declined 21 percent last year, and are expected to decline another 7 percent this year. Last spring, in the San Francisco Bay Area, an organization called JobNob began holding networking happy hours to try to match college graduates with start-up companies looking primarily for unpaid labor. Julie Greenberg, a co-founder of JobNob, says that at the first event, on May 7, she expected perhaps 30 people, but 300 showed up. New graduates didn’t have much of a chance; most of the people there had several years of work experience—quite a lot were 30-somethings—and some had more than one degree. JobNob has since held events for alumni of Stanford, Berkeley, and Harvard; all have been well attended (at the Harvard event, Greenberg tried to restrict attendance to 75, but about 100 people managed to get in), and all have been dominated by people with significant work experience.

When experienced workers holding prestigious degrees are taking unpaid internships, not much is left for newly minted B.A.s. Yet if those same B.A.s don’t find purchase in the job market, they’ll soon have to compete with a fresh class of graduates—ones without white space on their résumé to explain. This is a tough squeeze to escape, and it only gets tighter over time.

Strong evidence suggests that people who don’t find solid roots in the job market within a year or two have a particularly hard time righting themselves. In part, that’s because many of them become different—and damaged—people. Krysia Mossakowski, a sociologist at the University of Miami, has found that in young adults, long bouts of unemployment provoke long-lasting changes in behavior and mental health. “Some people say, ‘Oh, well, they’re young, they’re in and out of the workforce, so unemployment shouldn’t matter much psychologically,’” Mossakowski told me. “But that isn’t true.”

Examining national longitudinal data, Mossakowski has found that people who were unemployed for long periods in their teens or early 20s are far more likely to develop a habit of heavy drinking (five or more drinks in one sitting) by the time they approach middle age. They are also more likely to develop depressive symptoms. Prior drinking behavior and psychological history do not explain these problems—they result from unemployment itself. And the problems are not limited to those who never find steady work; they show up quite strongly as well in people who are later working regularly.

Forty years ago, Glen Elder, a sociologist at the University of North Carolina and a pioneer in the field of “life course” studies, found a pronounced diffidence in elderly men (though not women) who had suffered hardship as 20- and 30-somethings during the Depression. Decades later, unlike peers who had been largely spared in the 1930s, these men came across, he told me, as “beaten and withdrawn—lacking ambition, direction, confidence in themselves.” Today in Japan, according to the Japan Productivity Center for Socio-Economic Development, workers who began their careers during the “lost decade” of the 1990s and are now in their 30s make up six out of every 10 cases of depression, stress, and work-related mental disabilities reported by employers.

A large and long-standing body of research shows that physical health tends to deteriorate during unemployment, most likely through a combination of fewer financial resources and a higher stress level. The most-recent research suggests that poor health is prevalent among the young, and endures for a lifetime. Till Von Wachter, an economist at Columbia University, and Daniel Sullivan, of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, recently looked at the mortality rates of men who had lost their jobs in Pennsylvania in the 1970s and ’80s. They found that particularly among men in their 40s or 50s, mortality rates rose markedly soon after a layoff. But regardless of age, all men were left with an elevated risk of dying in each year following their episode of unemployment, for the rest of their lives. And so, the younger the worker, the more pronounced the effect on his lifespan: the lives of workers who had lost their job at 30, Von Wachter and Sullivan found, were shorter than those who had lost their job at 50 or 55—and more than a year and a half shorter than those who’d never lost their job at all.

J ournalists and academics have thrown various labels at today’s young adults, hoping one might stick—Generation Y, Generation Next, the Net Generation, the Millennials, the Echo Boomers. All of these efforts contain an element of folly; the diversity of character within a generation is always and infinitely larger than the gap between generations. Still, the cultural and economic environment in which each generation is incubated clearly matters. It is no coincidence that the members of Generation X—painted as cynical, apathetic slackers—first emerged into the workforce in the weak job market of the early-to-mid-1980s. Nor is it a coincidence that the early members of Generation Y—labeled as optimistic, rule-following achievers—came of age during the Internet boom of the late 1990s.

Many of today’s young adults seem temperamentally unprepared for the circumstances in which they now find themselves. Jean Twenge, an associate professor of psychology at San Diego State University, has carefully compared the attitudes of today’s young adults to those of previous generations when they were the same age. Using national survey data, she’s found that to an unprecedented degree, people who graduated from high school in the 2000s dislike the idea of work for work’s sake, and expect jobs and career to be tailored to their interests and lifestyle. Yet they also have much higher material expectations than previous generations, and believe financial success is extremely important. “There’s this idea that, ‘Yeah, I don’t want to work, but I’m still going to get all the stuff I want,’” Twenge told me. “It’s a generation in which every kid has been told, ‘You can be anything you want. You’re special.’”

In her 2006 book, Generation Me , Twenge notes that self-esteem in children began rising sharply around 1980, and hasn’t stopped since. By 1999, according to one survey, 91 percent of teens described themselves as responsible, 74 percent as physically attractive, and 79 percent as very intelligent. (More than 40 percent of teens also expected that they would be earning $75,000 a year or more by age 30; the median salary made by a 30-year-old was $27,000 that year.) Twenge attributes the shift to broad changes in parenting styles and teaching methods, in response to the growing belief that children should always feel good about themselves, no matter what. As the years have passed, efforts to boost self-esteem—and to decouple it from performance—have become widespread.

These efforts have succeeded in making today’s youth more confident and individualistic. But that may not benefit them in adulthood, particularly in this economic environment. Twenge writes that “self-esteem without basis encourages laziness rather than hard work,” and that “the ability to persevere and keep going” is “a much better predictor of life outcomes than self-esteem.” She worries that many young people might be inclined to simply give up in this job market. “You’d think if people are more individualistic, they’d be more independent,” she told me. “But it’s not really true. There’s an element of entitlement—they expect people to figure things out for them.”

Ron Alsop, a former reporter for The Wall Street Journal and the author of The Trophy Kids Grow Up: How the Millennial Generation Is Shaking Up the Workplace , says a combination of entitlement and highly structured childhood has resulted in a lack of independence and entrepreneurialism in many 20-somethings. They’re used to checklists, he says, and “don’t excel at leadership or independent problem solving.” Alsop interviewed dozens of employers for his book, and concluded that unlike previous generations, Millennials, as a group, “need almost constant direction” in the workplace. “Many flounder without precise guidelines but thrive in structured situations that provide clearly defined rules.”

All of these characteristics are worrisome, given a harsh economic environment that requires perseverance, adaptability, humility, and entrepreneurialism. Perhaps most worrisome, though, is the fatalism and lack of agency that both Twenge and Alsop discern in today’s young adults. Trained throughout childhood to disconnect performance from reward, and told repeatedly that they are destined for great things, many are quick to place blame elsewhere when something goes wrong, and inclined to believe that bad situations will sort themselves out—or will be sorted out by parents or other helpers.

In his remarks at last year’s commencement, in May, The New York Times reported, University of Connecticut President Michael Hogan addressed the phenomenon of students’ turning down jobs, with no alternatives, because they didn’t feel the jobs were good enough. “My first word of advice is this,” he told the graduates. “Say yes. In fact, say yes as often as you can. Saying yes begins things. Saying yes is how things grow. Saying yes leads to new experiences, and new experiences will lead to knowledge and wisdom. Yes is for young people, and an attitude of yes is how you will be able to go forward in these uncertain times.”

Larry Druckenbrod, the university’s assistant director of career services, told me last fall, “This is a group that’s done résumé building since middle school. They’ve been told they’ve been preparing to go out and do great things after college. And now they’ve been dealt a 180.” For many, that’s led to “immobilization.” Druckenbrod said that about a third of the seniors he talked to that semester were seriously looking for work; another third were planning to go to grad school. The final third, he said, were “not even engaging with the job market—these are the ones whose parents have already said, ‘Just come home and live with us.’”

According to a recent Pew survey, 10 percent of adults younger than 35 have moved back in with their parents as a result of the recession. But that’s merely an acceleration of a trend that has been under way for a generation or more. By the middle of the aughts, for instance, the percentage of 26-year-olds living with their parents reached 20 percent, nearly double what it was in 1970. Well before the recession began, this generation of young adults was less likely to work, or at least work steadily, than other recent generations. Since 2000, the percentage of people age 16 to 24 participating in the labor force has been declining (from 66 percent to 56 percent across the decade). Increased college attendance explains only part of the shift; the rest is a puzzle. Lingering weakness in the job market since 2001 may be one cause. Twenge believes the propensity of this generation to pursue “dream” careers that are, for most people, unlikely to work out may also be partly responsible. (In 2004, a national survey found that about one out of 18 college freshmen expected to make a living as an actor, musician, or artist.)

Whatever the reason, the fact that so many young adults weren’t firmly rooted in the workforce even before the crash is deeply worrying. It means that a very large number of young adults entered the recession already vulnerable to all the ills that joblessness produces over time. It means that for a sizeable proportion of 20- and 30-somethings, the next few years will likely be toxic.

N o young people were present at a seminar for the unemployed held on November 4 in Reading, Pennsylvania, a blue-collar city about 60 miles west of Philadelphia. The meeting was organized by a regional nonprofit, Joseph’s People, and held in the basement of the St. Catharine’s parish center. All 30 or so attendees, sitting around a U-shaped table, looked to be 40 or older. But one middle-aged man, one of the first to introduce himself to the group, said he and his wife were there on behalf of their son, Errol. “He’s so disgusted that he didn’t want to come,” the man said. “He doesn’t know what to do, and we don’t either.”

I talked to Errol a few days later. He is 28 and has a gentle, straightforward manner. He graduated from high school in 1999 and has lived with his parents since then. He worked in a machine shop for a couple of years after school, and has also held jobs at a battery factory, a sandpaper manufacturer, and a restaurant, where he was a cook. The restaurant closed in June 2008, and apart from a few days of work through temp agencies, he hasn’t had a job since.

He calls in to a few temp agencies each week to let them know he’s interested in working, and checks the newspaper for job listings every Sunday. Sometimes he goes into CareerLink, the local unemployment office, to see if it has any new listings. He does work around the house, or in the small machine shop he’s set up in the garage, just to fill his days, and to try to keep his skills up.

“I was thinking about moving,” he said. “I’m just really not sure where. Other places where I traveled, I didn’t really see much of a difference with what there was here.” He’s still got a few thousand dollars in the bank, which he saved when he was working as a machinist, and is mostly living off that; he’s been trading penny stocks to try to replenish those savings.

I asked him what he foresaw for his working life. “As far as my job position,” he said, “I really don’t know what I want to do yet. I’m not sure.” When he was little, he wanted to be a mechanic, and he did enjoy the machine trade. But now there was hardly any work to be had, and what there was paid about the same as Walmart. “I don’t think there’s any way that you can have a job that you can think you can retire off of,” he said. “I think everyone’s going to have to transfer to another job.” He said the only future he could really imagine for himself now was just moving from job to job, with no career to speak of. “That’s what I think,” he said. “I don’t want to.”

In her classic sociology of the Depression, The Unemployed Man and His Family , Mirra Komarovsky vividly describes how joblessness strained—and in many cases fundamentally altered—family relationships in the 1930s. During 1935 and 1936, Komarovsky and her research team interviewed the members of 59 white middle-class families in which the husband and father had been out of work for at least a year. Her research revealed deep psychological wounds. “It is awful to be old and discarded at 40,” said one father. “A man is not a man without work.” Another said plainly, “During the depression I lost something. Maybe you call it self-respect, but in losing it I also lost the respect of my children, and I am afraid I am losing my wife.” Noted one woman of her husband, “I still love him, but he doesn’t seem as ‘big’ a man.”

Taken together, the stories paint a picture of diminished men, bereft of familial authority. Household power—over children, spending, and daily decisions of all types—generally shifted to wives over time (and some women were happier overall as a result). Amid general anxiety, fears of pregnancy, and men’s loss of self-worth and loss of respect from their wives, sex lives withered. Socializing all but ceased as well, a casualty of poverty and embarrassment. Although some men embraced family life and drew their wife and children closer, most became distant. Children described their father as “mean,” “nasty,” or “bossy,” and didn’t want to bring friends around, for fear of what he might say. “There was less physical violence towards the wife than towards the child,” Komarovsky wrote.

In the 70 years that have passed since the publication of The Unemployed Man and His Family , American society has become vastly more wealthy, and a more comprehensive social safety net—however frayed it may seem—now stretches beneath it. Two-earner households have become the norm, cushioning the economic blow of many layoffs. And of course, relationships between men and women have evolved. Yet when read today, large parts of Komarovsky’s book still seem disconcertingly up-to-date. All available evidence suggests that long bouts of unemployment—particularly male unemployment—still enfeeble the jobless and warp their families to a similar degree, and in many of the same ways.

Andrew Oswald, an economist at the University of Warwick, in the U.K., and a pioneer in the field of happiness studies, says no other circumstance produces a larger decline in mental health and well-being than being involuntarily out of work for six months or more. It is the worst thing that can happen, he says, equivalent to the death of a spouse, and “a kind of bereavement” in its own right. Only a small fraction of the decline can be tied directly to losing a paycheck, Oswald says; most of it appears to be the result of a tarnished identity and a loss of self-worth. Unemployment leaves psychological scars that remain even after work is found again, and, because the happiness of husbands and the happiness of wives are usually closely related, the misery spreads throughout the home.

Especially in middle-aged men, long accustomed to the routine of the office or factory, unemployment seems to produce a crippling disorientation. At a series of workshops for the unemployed that I attended around Philadelphia last fall, the participants were overwhelmingly male, and the men in particular described the erosion of their identities, the isolation of being jobless, and the indignities of downward mobility.

Over lunch I spoke with one attendee, Gus Poulos, a Vietnam-era veteran who had begun his career as a refrigeration mechanic before going to night school and becoming an accountant. He is trim and powerfully built, and looks much younger than his 59 years. For seven years, until he was laid off in December 2008, he was a senior financial analyst for a local hospital.

Poulos said that his frustration had built and built over the past year. “You apply for so many jobs and just never hear anything,” he told me. “You’re one of my few interviews. I’m just glad to have an interview with anybody, even a magazine.” Poulos said he was an optimist by nature, and had always believed that with preparation and hard work, he could overcome whatever life threw at him. But sometime in the past year, he’d lost that sense, and at times he felt aimless and adrift. “That’s never been who I am,” he said. “But now, it’s who I am.”

Recently he’d gotten a part-time job as a cashier at Walmart, for $8.50 an hour. “They say, ‘Do you want it?’ And in my head, I thought, ‘No.’ And I raised my hand and said, ‘Yes.’” Poulos and his wife met when they were both working as supermarket cashiers, four decades earlier—it had been one of his first jobs. “Now, here I am again.”

Poulos’s wife is still working—she’s a quality-control analyst at a food company—and that’s been a blessing. But both are feeling the strain, financial and emotional, of his situation. She commutes about 100 miles every weekday, which makes for long days. His hours at Walmart are on weekends, so he doesn’t see her much anymore and doesn’t have much of a social life.

Some neighbors were at the Walmart a couple of weeks ago, he said, and he rang up their purchase. “Maybe they were used to seeing me in a different setting,” he said—in a suit as he left for work in the morning, or walking the dog in the neighborhood. Or “maybe they were daydreaming.” But they didn’t greet him, and he didn’t say anything. He looked down at his soup, pushing it around the bowl with his spoon for a few seconds before looking back up at me. “I know they knew me,” he said. “I’ve been in their home.”

T he weight of this recession has fallen most heavily upon men, who’ve suffered roughly three-quarters of the 8 million job losses since the beginning of 2008. Male-dominated industries (construction, finance, manufacturing) have been particularly hard-hit, while sectors that disproportionately employ women (education, health care) have held up relatively well. In November, 19.4 percent of all men in their prime working years, 25 to 54, did not have jobs, the highest figure since the Bureau of Labor Statistics began tracking the statistic in 1948. At the time of this writing, it looks possible that within the next few months, for the first time in U.S. history, women will hold a majority of the country’s jobs.

In this respect, the recession has merely intensified a long-standing trend. Broadly speaking, the service sector, which employs relatively more women, is growing, while manufacturing, which employs relatively more men, is shrinking. The net result is that men have been contributing a smaller and smaller share of family income.

“Traditional” marriages, in which men engage in paid work and women in homemaking, have long been in eclipse. Particularly in blue-collar families, where many husbands and wives work staggered shifts, men routinely handle a lot of the child care today. Still, the ease with which gender bends in modern marriages should not be overestimated. When men stop doing paid work—and even when they work less than their wives—marital conflict usually follows.

Last March, the National Domestic Violence Hotline received almost half again as many calls as it had one year earlier; as was the case in the Depression, unemployed men are vastly more likely to beat their wives or children. More common than violence, though, is a sort of passive-aggressiveness. In Identity Economics , the economists George Akerloff and Rachel Kranton find that among married couples, men who aren’t working at all, despite their free time, do only 37 percent of the housework, on average. And some men, apparently in an effort to guard their masculinity, actually do less housework after becoming unemployed.

Many working women struggle with the idea of partners who aren’t breadwinners. “We’ve got this image of Archie Bunker sitting at home, grumbling and acting out,” says Kathryn Edin, a professor of public policy at Harvard, and an expert on family life. “And that does happen. But you also have women in whole communities thinking, ‘This guy’s nothing.’” Edin’s research in low-income communities shows, for instance, that most working women whose partner stayed home to watch the kids—while very happy with the quality of child care their children’s father provided—were dissatisfied with their relationship overall. “These relationships were often filled with conflict,” Edin told me. Even today, she says, men’s identities are far more defined by their work than women’s, and both men and women become extremely uncomfortable when men’s work goes away.

The national divorce rate fell slightly in 2008, and that’s not unusual in a recession: divorce is expensive, and many couples delay it in hard times. But joblessness corrodes marriages, and makes divorce much more likely down the road. According to W. Bradford Wilcox, the director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia, the gender imbalance of the job losses in this recession is particularly noteworthy, and—when combined with the depth and duration of the jobs crisis—poses “a profound challenge to marriage,” especially in lower-income communities. It may sound harsh, but in general, he says, “if men can’t make a contribution financially, they don’t have much to offer.” Two-thirds of all divorces are legally initiated by women. Wilcox believes that over the next few years, we may see a long wave of divorces, washing no small number of discarded and dispirited men back into single adulthood.

Among couples without college degrees, says Edin, marriage has become an “increasingly fragile” institution. In many low-income communities, she fears it is being supplanted as a social norm by single motherhood and revolving-door relationships. As a rule, fewer people marry during a recession, and this one has been no exception. But “the timing of this recession coincides with a pretty significant cultural change,” Edin says: a fast-rising material threshold for marrying, but not for having children, in less affluent communities.

Edin explains that poor and working-class couples, after seeing the ravages of divorce on their parents or within their communities, have become more hesitant to marry; they believe deeply in marriage’s sanctity, and try to guard against the possibility that theirs will end in divorce. Studies have shown that even small changes in income have significant effects on marriage rates among the poor and the lower-middle class. “It’s simply not respectable to get married if you don’t have a job—some way of illustrating to your neighbors that you have at least some grasp on some piece of the American pie,” Edin says. Increasingly, people in these communities see marriage not as a way to build savings and stability, but as “a symbol that you’ve arrived.”

Childbearing is the opposite story. The stigma against out-of-wedlock children has by now largely dissolved in working-class communities—more than half of all new mothers without a college degree are unmarried. For both men and women in these communities, children are commonly seen as a highly desirable, relatively low-cost way to achieve meaning and bolster identity—especially when other opportunities are closed off. Christina Gibson-Davis, a public-policy professor at Duke University, recently found that among adults with no college degree, changes in income have no bearing at all on rates of childbirth.

“We already have low marriage rates in low-income communities,” Edin told me, “including white communities. And where it’s really hitting now is in working-class urban and rural communities, where you’re just seeing astonishing growth in the rates of nonmarital childbearing. And that would all be fine and good, except these parents don’t stay together. This may be one of the most devastating impacts of the recession.”

Many children are already suffering in this recession, for a variety of reasons. Among poor families, nutrition can be inadequate in hard times, hampering children’s mental and physical development. And regardless of social class, the stresses and distractions that afflict unemployed parents also afflict their kids, who are more likely to repeat a grade in school, and who on average earn less as adults. Children with unemployed fathers seem particularly vulnerable to psychological problems.

But a large body of research shows that one of the worst things for children, in the long run, is an unstable family. By the time the average out-of-wedlock child has reached the age of 5, his or her mother will have had two or three significant relationships with men other than the father, and the child will typically have at least one half sibling. This kind of churning is terrible for children—heightening the risks of mental-health problems, troubles at school, teenage delinquency, and so on—and we’re likely to see more and more of it, the longer this malaise stretches on.

“We could be headed in a direction where, among elites, marriage and family are conventional, but for substantial portions of society, life is more matriarchal,” says Wilcox. The marginalization of working-class men in family life has far-reaching consequences. “Marriage plays an important role in civilizing men. They work harder, longer, more strategically. They spend less time in bars and more time in church, less with friends and more with kin. And they’re happier and healthier.”

Communities with large numbers of unmarried, jobless men take on an unsavory character over time. Edin’s research team spent part of last summer in Northeast and South Philadelphia, conducting in-depth interviews with residents. She says she was struck by what she saw: “These white working-class communities—once strong, vibrant, proud communities, often organized around big industries—they’re just in terrible straits. The social fabric of these places is just shredding. There’s little engagement in religious life, and the old civic organizations that people used to belong to are fading. Drugs have ravaged these communities, along with divorce, alcoholism, violence. I hang around these neighborhoods in South Philadelphia, and I think, ‘This is beginning to look like the black inner-city neighborhoods we’ve been studying for the past 20 years.’ When young men can’t transition into formal-sector jobs, they sell drugs and drink and do drugs. And it wreaks havoc on family life. They think, ‘Hey, if I’m 23 and I don’t have a baby, there’s something wrong with me.’ They’re following the pattern of their fathers in terms of the timing of childbearing, but they don’t have the jobs to support it. So their families are falling apart—and often spectacularly.”

I n his 1996 book , When Work Disappears , the Harvard sociologist William Julius Wilson connected the loss of jobs from inner cities in the 1970s to the many social ills that cropped up after that. “The consequences of high neighborhood joblessness,” he wrote,

are more devastating than those of high neighborhood poverty. A neighborhood in which people are poor but employed is different from a neighborhood in which many people are poor and jobless. Many of today’s problems in the inner-city ghetto neighborhoods—crime, family dissolution, welfare, low levels of social organization, and so on—are fundamentally a consequence of the disappearance of work.

In the mid-20th century, most urban black men were employed, many of them in manufacturing. But beginning in the 1970s, as factories moved out of the cities or closed altogether, male unemployment began rising sharply. Between 1973 and 1987, the percentage of black men in their 20s working in manufacturing fell from roughly 37.5 percent to 20 percent. As inner cities shed manufacturing jobs, men who lived there, particularly those with limited education, had a hard time making the switch to service jobs. Service jobs and office work of course require different interpersonal skills and different standards of self-presentation from those that blue-collar work demands, and movement from one sector to the other can be jarring. What’s more, Wilson’s research shows, downwardly mobile black men often resented the new work they could find, and displayed less flexibility on the job than, for instance, first-generation immigrant workers. As a result, employers began to prefer hiring women and immigrants, and a vicious cycle of resentment, discrimination, and joblessness set in.

It remains to be seen whether larger swaths of the country, as male joblessness persists, will eventually come to resemble the inner cities of the 1970s and ’80s. In any case, one of the great catastrophes of the past decade, and in particular of this recession, is the slippage of today’s inner cities back toward the depths of those brutal years. Urban minorities tend to be among the first fired in a recession, and the last rehired in a recovery. Overall, black unemployment stood at 15.6 percent in November; among Hispanics, that figure was 12.7 percent. Even in New York City, where the financial sector, which employs relatively few blacks, has shed tens of thousands of jobs, unemployment has increased much faster among blacks than it has among whites.

In June 1999, the journalist Ellis Cose wrote in Newsweek that it was then “the best time ever” to be black in America. He ticked through the reasons: employment was up, murders and out-of-wedlock births down; educational attainment was rising, and poverty less common than at any time since 1967. Middle-class black couples were slowly returning to gentrifying inner-city neighborhoods. “Even for some of the most persistently unfortunate—uneducated black men between 16 and 24—jobs are opening up,” Cose wrote.

But many of those gains are now imperiled. Late last year, unemployment among black teens ages 16 to 19 was nearly 50 percent, and the unemployment rate for black men age 20 or older was almost 17 percent. With so few jobs available, Wilson told me, “many black males will give up and drop out of the labor market, and turn more to the underground economy. And it will be very difficult for these people”—especially those who acquire criminal records—“to reenter the labor market in any significant way.” Glen Elder, the sociologist at the University of North Carolina, who’s done field work in Baltimore, said, “At a lower level of skill, if you lose a job and don’t have fathers or brothers with jobs—if you don’t have a good social network—you get drawn back into the street. There’s a sense in the kids I’ve studied that they lost everything they had, and can’t get it back.”

In New York City, 18 percent of low-income blacks and 26 percent of low-income Hispanics reported having lost their job as a result of the recession in a July survey by the Community Service Society. More still had had their hours or wages reduced. About one in seven low-income New Yorkers often skipped meals in 2009 to save money, and one in five had had the gas, electricity, or telephone turned off. Wilson argues that once neighborhoods become socially dysfunctional, it takes a long period of unbroken good times to undo the damage—and they can backslide very quickly and steeply. “One problem that has plagued the black community over the years is resignation,” Wilson said—a self-defeating “set of beliefs about what to expect from life and how to respond,” passed from parent to child. “And I think there was sort of a feeling that norms of resignation would weaken somewhat with the Obama election. But these hard economic times could reinforce some of these norms.”

Wilson, age 74, is a careful scholar, who chooses his words precisely and does not seem given to overstatement. But he sounded forlorn when describing the “very bleak” future he sees for the neighborhoods that he’s spent a lifetime studying. There is “no way,” he told me, “that the extremely high jobless rates we’re seeing won’t have profound consequences for the social organization of inner-city neighborhoods.” Neighborhood-specific statistics on drug addiction, family dysfunction, gang violence, and the like take time to compile. But Wilson believes that once we start getting detailed data on the conditions of inner-city life since the crash, “we’re going to see some horror stories”—and in many cases a relapse into the depths of decades past. “The point I want to emphasize,” Wilson said, “is that we should brace ourselves.”

No one tries harder than the jobless to find silver linings in this national economic disaster. Many of the people I spoke with for this story said that unemployment, while extremely painful, had improved them in some ways: they’d become less materialistic and more financially prudent; they were using free time to volunteer more, and were enjoying that; they were more empathetic now, they said, and more aware of the struggles of others.

In limited respects, perhaps the recession will leave society better off. At the very least, it’s awoken us from our national fever dream of easy riches and bigger houses, and put a necessary end to an era of reckless personal spending. Perhaps it will leave us humbler, and gentler toward one another, too—at least in the long run. A recent paper by the economists Paola Giuliano and Antonio Spilimbergo shows that generations that endured a recession in early adulthood became more concerned about inequality and more cognizant of the role luck plays in life. And in his book, Children of the Great Depression , Glen Elder wrote that adolescents who experienced hardship in the 1930s became especially adaptable, family-oriented adults; perhaps, as a result of this recession, today’s adolescents will be pampered less and counted on for more, and will grow into adults who feel less entitled than recent generations.

But for the most part, these benefits seem thin, uncertain, and far off. In The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth , the economic historian Benjamin Friedman argues that both inside and outside the U.S., lengthy periods of economic stagnation or decline have almost always left society more mean-spirited and less inclusive, and have usually stopped or reversed the advance of rights and freedoms. A high level of national wealth, Friedman writes, “is no bar to a society’s retreat into rigidity and intolerance once enough of its citizens lose the sense that they are getting ahead.” When material progress falters, Friedman concludes, people become more jealous of their status relative to others. Anti-immigrant sentiment typically increases, as does conflict between races and classes; concern for the poor tends to decline.

Social forces take time to grow strong, and time to dissipate again. Friedman told me that the phenomenon he’s studied “is not about business cycles … It’s not about people comparing where they are now to where they were a year ago.” The relevant comparisons are much broader: What opportunities are available to me, relative to those of my parents? What opportunities do my children have? What is the trajectory of my career?

It’s been only about two years since this most recent recession started, but then again, most people hadn’t been getting ahead for a decade. In a Pew survey in the spring of 2008, more than half of all respondents said that over the past five years, they either hadn’t moved forward in life or had actually fallen backward, the most downbeat assessment that either Pew or Gallup has ever recorded, in nearly a half century of polling. Median household income in 2008 was the lowest since 1997, adjusting for inflation. “On the latest income data,” Friedman said, “we’re 11 years into a period of decline.” By the time we get out of the current downturn, we’ll likely be “up to a decade and a half. And that’s surely enough.”

Income inequality usually falls during a recession, and the economist and happiness expert Andrew Clark says that trend typically provides some emotional salve to the poor and the middle class. (Surveys, lab experiments, and brain readings all show that, for better or worse, schadenfreude is a powerful psychological force: at any fixed level of income, people are happier when the income of others is reduced.) But income inequality hasn’t shrunk in this recession. In 2007–08, the most recent year for which data is available, it widened.

Indeed, this period of economic weakness may reinforce class divides, and decrease opportunities to cross them—especially for young people. The research of Till Von Wachter, the economist at Columbia University, suggests that not all people graduating into a recession see their life chances dimmed: those with degrees from elite universities catch up fairly quickly to where they otherwise would have been if they’d graduated in better times; it’s the masses beneath them that are left behind. Princeton’s 2009 graduating class found more jobs in financial services than in any other industry. According to Princeton’s career-services director, Beverly Hamilton-Chandler, campus visits and hiring by the big investment banks have been down, but that decline has been partly offset by an uptick in recruiting by hedge funds and boutique financial firms.

In the Internet age, it is particularly easy to see the bile that has always lurked within American society. More difficult, in the moment, is discerning precisely how these lean times are affecting society’s character. In many respects, the U.S. was more socially tolerant entering this recession than at any time in its history, and a variety of national polls on social conflict since then have shown mixed results. Signs of looming class warfare or racial conflagration are not much in evidence. But some seeds of discontent are slowly germinating. The town-hall meetings last summer and fall were contentious, often uncivil, and at times given over to inchoate outrage. One National Journal poll in October showed that whites (especially white men) were feeling particularly anxious about their future and alienated by the government. We will have to wait and see exactly how these hard times will reshape our social fabric. But they certainly will reshape it, and all the more so the longer they extend.

A slowly sinking generation; a remorseless assault on the identity of many men; the dissolution of families and the collapse of neighborhoods; a thinning veneer of national amity—the social legacies of the Great Recession are still being written, but their breadth and depth are immense. As problems, they are enormously complex, and their solutions will be equally so.

Of necessity, those solutions must include measures to bolster the economy in the short term, and to clear the way for faster long-term growth; to support the jobless today, and to ensure that we are creating the kinds of jobs (and the kinds of skills within the population) that can allow for a more broadly shared prosperity in the future. A few of the solutions—like more-aggressive support for the unemployed, and employer tax credits or other subsidies to get people back to work faster—are straightforward and obvious, or at least they should be. Many are not.

At the very least, though, we should make the return to a more normal jobs environment an unflagging national priority. The stock market has rallied, the financial system has stabilized, and job losses have slowed; by the time you read this, the unemployment rate might be down a little. Yet the difference between “turning the corner” and a return to any sort of normalcy is vast.

We are in a very deep hole, and we’ve been in it for a relatively long time already. Concerns over deficits are understandable, but in these times, our bias should be toward doing too much rather than doing too little. That implies some small risk to the government’s ability to continue borrowing in the future; and it implies somewhat higher taxes in the future too. But that seems a trade worth making. We are living through a slow-motion social catastrophe, one that could stain our culture and weaken our nation for many, many years to come. We have a civic—and indeed a moral—responsibility to do everything in our power to stop it now, before it gets even worse.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Cope If You’ve Lost Your Job Amidst The Coronavirus Pandemic

Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/VW-MIND-Amy-2b338105f1ee493f94d7e333e410fa76.jpg)

Steven Gans, MD is board-certified in psychiatry and is an active supervisor, teacher, and mentor at Massachusetts General Hospital.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/steven-gans-1000-51582b7f23b6462f8713961deb74959f.jpg)

Mahir KART / Shutterstock

Key Takeaways

- Research shows that unemployment is associated with increased depression and anxiety.

- Acknowledging your feelings can help you heal from the loss and move on.

- When you feel overwhelmed, focus on what you can control and take action.

The stress of unemployment can take a serious toll on your well-being under any circumstance. But during the coronavirus pandemic, your stress levels may be even higher than usual.

With our current situation and the state of the global economy , there is a much lower chance of landing a new job anytime soon. And it’s unclear when social distancing measures will end or what shape the economy will be in when you are able to return to work.

Add in the fear of getting sick, the inability to leave home, and the need to educate your children, and you’ve got a recipe for an increased risk of mental health issues.

Fortunately, there are some things you can do to cope with the stress in a healthy way if you’ve lost your job. Managing your distress and taking positive action may help you maintain your mental health during this crisis.

The Link Between Unemployment and Mental Health

Unemployment has been linked to a greater risk of depression, anxiety, suicide, substance abuse , and violence .

In fact, studies show people who lose their jobs are twice as likely to report depression and anxiety symptoms when compared with people who remain stably employed.

Here are several reasons why not having a job can take a serious toll on your psychological well-being:

- Difficulty paying for basic necessities : Reduced income makes it difficult to purchase food and pay for housing. The associated stress makes it difficult to stay mentally healthy.

- Lack of purpose : Not contributing to society and not bringing home any income to support the family can leave some people feeling as though their lives lack meaning and purpose.

- Reduced social interaction : Not having a job can mean less social interaction, which takes a direct toll on mood and well-being.

- Fewer resources available to maintain mental health : When your time and energy have to go into managing your life (food, housing, and basic necessities), you have fewer resources left to devote to behaviors that promote good mental health (exercising, maintaining social relationships, etc).

- Unhealthy coping skills may be more tempting : While some people may respond to unemployment by cutting things that cost extra, others turn to unhealthy coping skills like drugs and alcohol, which can take a toll on health and well-being.

There are two main things you can do to manage your mental health when faced with this situation: address your unemployment, and address how you feel about being unemployed.

Tackle the Problem

It’s important to take action that will help solve your problems when you’re unemployed, such as looking for resources that help you manage your financial strain and looking for employment.

During the coronavirus pandemic, looking for work might not be so easy. You might be waiting for businesses to open up, so you can return to your old job. Or you might not be certain if your old job will even exist when this is over.

There are few places hiring right now, so your chances of getting another job at the moment are limited. But this doesn’t mean you should idly wait for things to get better. You can take action now to manage your finances and address your employment situation.

This action might include things such as:

- Apply for unemployment : Filing for unemployment may reduce your financial strain.

- Look for new job opportunities : Whether you search for a new full-time job, or you look for ways to make money in the “gig economy,” actively searching for work can help you feel better.

- Create a budget : Creating a budget can help you gain a better sense of control over your financial situation.

- Manage your payments : Explaining your situation to your credit card company, mortgage lender, and other financial institutions may help lower your payments. Financial institutions may also grant you more time to pay your bills.

- Search for helpful resources : Whether you want to talk to a career counselor, or you’re looking for help with paying your electric bill, there may be resources available.

- Further your education : Taking classes for credit or signing up for an online course for your own enrichment could be helpful to your career.

- Update your resume : Updating your resume (and asking for feedback from others) might increase your chances of landing a job if you start applying for new positions.

Tackle How You Feel About the Problem

In addition to addressing your employment issues, you can also address your emotional distress head-on.

- Practice good self-care : Getting plenty of sleep and eating a healthy diet is key to managing your distress. You need to take care of your body if you want your mind to function at an optimal level.

- Maintain social interaction : While you may not be able to meet with your friends and family in person, it’s important to stay in contact. Video chat, talk on the phone, or message one another regularly. Positive social interaction can greatly improve your mental health.

- Structure your day : Staying on a schedule can help you feel better. Create time to work on your job situation, time for leisure, and time to do things that help improve your mental health.

- Get physically active : Exercise is a key component to good mental health. During the pandemic, you may need to get creative since most gyms are closed. But working out in your living room with an app or video can go a long way toward helping you stay physically and mentally healthy.

- Reach for healthy coping skills : Writing in a journal, meditating, deep breathing, and yoga are just a few examples of healthy ways to relieve stress. Make sure you have plenty of healthy coping skills at your disposal, so you can reach for something healthy when your distress starts to increase.

- Eliminate unhealthy coping skills : You might be tempted to turn to things that give you some immediate relief—like alcohol or food. But these things will cause more problems for you in the long term. So make unhealthy coping skills harder to access, and monitor your use. You don’t want to accidentally create bigger problems or introduce new problems into your life.

- “Change the channel” when you’re ruminating : Dwelling on things you have no control over will keep you stuck in an unhealthy state. If you find yourself thinking about how awful your life is, or you’re making catastrophic predictions, then interrupt yourself. Get up and do something to change the channel in your brain. Distract yourself with a chore or activity.

- Talk to a professional if you’re struggling : If you’re feeling depressed or anxious, or you’re having difficulty functioning, contact a mental health professional. Talk therapy or medication may help you feel better.

Resources That Can Help

There are many employment and financial resources that have become available during the coronavirus pandemic for individuals who have lost their jobs.

Whether you’re concerned about health insurance, or you’re having difficulty paying your utility bill, 211 may be able to direct you to someone who can help. They specialize in locating helpful resources, and it’s free of charge.

State Government Websites

Every state offers slightly different benefits and services, so it’s important to go to your state’s website . The website can help you locate financial assistance programs and an application for unemployment.

CareerOneStop

This website explains unemployment benefits and can help you discover your eligibility.

Families First Coronavirus Response Act

This bill , enacted in March 2020, explains unemployment benefits, paid sick leave rules, and food assistance benefits during the pandemic.

Small Business Administration (SBA)

Small businesses may apply for low-interest disaster loans, some of which may be forgiven. Learn more here

Feeding America

The Feeding America website provides information on local food banks and how to access them during this crisis.

What This Means For You

It’s frustrating and scary to be unemployed. And it’s tough to plan for the future right now due to the uncertainty of the situation. But taking care of yourself and your mental health can help you cope with some of the distress you’re feeling.

If you’re struggling to manage your mental health, however, it’s not a sign of weakness. Don’t be afraid to ask for help. Talking to a therapist can help. And there are many ways to reach out to a therapist online right now, so you don’t even have to leave home to do it.

Helpful Links

How to Protect Your Mental Health During the COVID-19 Pandemic

How to Transition To Online Therapy

The information in this article is current as of the date listed, which means newer information may be available when you read this. For the most recent updates on COVID-19, visit our coronavirus news page .

Goldman-Mellor, SJ. Unemployment and mental health . In: Encyclopedia of Mental Health . Elsevier; 2016:350-355. doi:10.1016/b978-0-12-397045-9.00053-7

By Amy Morin, LCSW Amy Morin, LCSW, is a psychotherapist and international bestselling author. Her books, including "13 Things Mentally Strong People Don't Do," have been translated into more than 40 languages. Her TEDx talk, "The Secret of Becoming Mentally Strong," is one of the most viewed talks of all time.