Literature review: Water quality and public health problems in developing countries

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Reprints and Permissions

- Cite Icon Cite

- Search Site

Eni Muryani; Literature review: Water quality and public health problems in developing countries. AIP Conf. Proc. 23 November 2021; 2363 (1): 050020. https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0061561

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

Water’s essential function as drinking water is a significant daily intake. Contamination by microorganisms (bacteria or viruses) on water sources and drinking water supplies is a common cause in developing countries like Indonesia. This paper will discuss the sources of clean water and drinking water and their problems in developing countries; water quality and its relation to public health problems in these countries; and what efforts that can be make to improve water quality. The method used is a literature review from the latest journals. Water quality is influenced by natural processes and human activities around the water source Among developed countries, public health problems caused by low water quality, such as diarrhea, dysentery, cholera, typhus, skin itching, kidney disease, hypertension, heart disease, cancer, and other diseases the nervous system. Good water quality has a role to play in decreasing the number of disease sufferers or health issues due to drinking and the mortality rate. The efforts made to improve water quality and public health are by improving WASH (water, sanitation, and hygiene) facilities and infrastructure and also WASH education.

Sign in via your Institution

Citing articles via, publish with us - request a quote.

Sign up for alerts

- Online ISSN 1551-7616

- Print ISSN 0094-243X

- For Researchers

- For Librarians

- For Advertisers

- Our Publishing Partners

- Physics Today

- Conference Proceedings

- Special Topics

pubs.aip.org

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

Connect with AIP Publishing

This feature is available to subscribers only.

Sign In or Create an Account

System Approaches to Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene: A Systematic Literature Review

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of Civil, Environmental, and Architectural Engineering, University of Colorado Boulder, Boulder, CO 80309, USA.

- 2 USAID Sustainable WASH Systems Learning Partnership, United State Agency for International Development, Washington, DC 20004, USA.

- 3 College of Engineering, George Fox University, Newberg, OR 97132, USA.

- PMID: 31973179

- PMCID: PMC7037755

- DOI: 10.3390/ijerph17030702

Endemic issues of sustainability in the water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) sector have led to the rapid expansion of 'system approaches' for assessing the multitude of interconnected factors that affect WASH outcomes. However, the sector lacks a systematic analysis and characterization of the knowledge base for systems approaches, in particular how and where they are being implemented and what outcomes have resulted from their application. To address this need, we conducted a wide-ranging systematic literature review of systems approaches for WASH across peer-reviewed, grey, and organizational literature. Our results show a myriad of methods, scopes, and applications within the sector, but an inadequate level of information in the literature to evaluate the utility and efficacy of systems approaches for improving WASH service sustainability. Based on this analysis, we propose four recommendations for improving the evidence base including: diversifying methods that explicitly evaluate interconnections between factors within WASH systems; expanding geopolitical applications; improving reporting on resources required to implement given approaches; and enhancing documentation of effects of systems approaches on WASH services. Overall, these findings provide a robust survey of the existing landscape of systems approaches for WASH and propose a path for future research in this emerging field.

Keywords: WASH; grey literature; systematic literature review; systems approaches.

Publication types

- Research Support, U.S. Gov't, Non-P.H.S.

- Systematic Review

- Sanitation*

- Water Supply / standards*

Advertisement

Attainment of water and sanitation goals: a review and agenda for research

- Original Article

- Published: 23 August 2022

- Volume 8 , article number 146 , ( 2022 )

Cite this article

- Sanjeet Singh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6103-2346 1 , 2 &

- R. Jayaram 2

5683 Accesses

5 Citations

1 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

One-fourth of the global population is without basic drinking water and half of the global population lacks sanitation facilities. The attainment of water and sanitation targets is difficult due to administrative, operational, political, transborder, technical, and policy challenges. Conducted after 5 years from the adoption of sustainable development goals by the United Nations reviews the initiatives for improving access, quality, and affordability of water and sanitation. The bibliometric and thematic analyses are conducted to consolidate the outcomes of scientific papers on sustainable development goal 6 (SDG 6). Africa is struggling in relation with water and sanitation goals, having 17 countries with less than 40% basic drinking water facilities and 16 countries with less than 40% basic sanitation facilities. Globally, the attainment of water and sanitation goals will be depended on economic development, the development of revolutionary measures for wastewater treatment, and creating awareness related to water usage, water recycling, water harvesting, hygiene, and sanitation. Behavioral changes are also required for a new water culture and the attainment of water and sanitation goals by 2030.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Sustainable Development Goal on Water and Sanitation: Learning from the Millennium Development Goals

The Human Right to Water and Sanitation: Reflections on Making the System Effective

Water for all: Exploring determinants of safe water access in developing regions

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The world is rapidly moving towards a global water crisis (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2014 ). In this background, the “Water Action Decade” (2018–2028) has been initiated by UN General Assembly (United Nations Organisation-Sustainable Development Goals, 2021 ). Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 6 aims at ensuring clean water and sanitation for all. According to the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), 2 billion people are struggling for safe drinking water; 4 billion people for sanitation requirements, and 3 billion people are facing challenges for basic hand wash facilities (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2021 ). Six billion people are in the practice of open defecation (UN-Regional Information Centre for Western Europe, 2021 ). A study on Global water status by UN-Water (2020–21) points out that 26% of the world population are struggling for drinking water, 46% for sanitation, and 44% of households are without proper wastewater treatment (United Nations, 2021 ). Anthropogenic wastewater can create serious concern on life on land and water bodies (López-Pacheco et al., 2019 ). The threat of anthropogenic wastewater and lagging performance in this respect is a serious threat to humanity.

The SDG 6 involves 8 targets and 11 indicators, focusing on clean and safe drinking water, reducing the open defecation practices, integrated water resource management by improvement of water quality; enhancing wastewater treatment, promoting water recycling, and eliminating all types of water wastages. The other targets of SDG 6 involve transboundary water co-operations; protection and restoration of water-related ecosystems; local community participation and building networks for the attainment of water and sanitation goals.

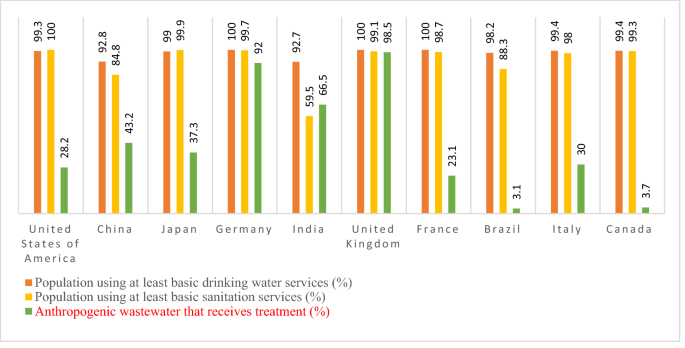

A country-wise analysis into the attainment of SDG 6 by Sustainable Development Report 2021 of the Cambridge University Press (Sachs et al., 2021 ) indicates a serious water crisis among African countries. Eight African countries are with less than 50% of basic drinking water facilities and 15 countries are in the categories below 60% attainment (SDG Index. Org 2021 ). The report exhibits that the average per capita GDP of poorly performing African countries is 762 dollars and the average share of agriculture in GDP is 28.46%. This points out the need for reducing excessive dependence on agriculture, improving economic activities, per capita GDP, and investments in African regions. Sanitation is another challenge in achieving the targets of SDG 6. Both Asian and European countries are on the way to attain sanitation goals. Twelve Asian countries and four South American countries are lagging in their performance related to sanitation goals. The African region is facing severe challenge in providing basic sanitation facilities to its citizen, especially 12 African countries are with below 20% attainment of basic sanitation facilities. Twenty-two countries are successful in providing basic sanitation to the entire population of the country. The average per capita GDP of these countries is 46460 dollars and the percentage of agriculture GDP in gross GDP is 3.19% (United Nations Organisation- Sustainable Development Goals, 2021 ). Seven European countries and Singapore have attained reasonable progress in creating proper facilities for the treatment of anthropogenic wastewater. The average per capita GDP of these countries is 64,560 dollars and the share of agriculture in gross GDP is 2.42%. Fifty countries are without any facilities for proper treatment for anthropogenic wastewater. Sixteen leading countries (countries providing basic sanitation, drinking water, and treatment for anthropogenic wastewater to at least 90% of the population) represent 3.71% of the global population. These countries has an average per capita GDP of 58,209 dollars; average per capita exports of 19,020 dollars; share of exports on GDP stood at 32.76% and share of agriculture in GDP is 2.98% (United Nations Organisation- Sustainable Development Goals, 2021 ). The leading economies like the United States of America, India, China, Japan, Brazil, France, Italy, and Canada are lagging in performance related to sanitation and treatment for anthropogenic wastewater. Urgent actions are needed for ensuring the provision for the treatment of anthropogenic wastewater. Any delay in performance of ensuring treatment for anthropogenic wastewater can negatively affect the access and quality of drinking water and can be a costly and dangerous choice for the goals of safe drinking water and sanitation of future generations (Bondur and Grebenuk, 2001 ; Gelsomino et al., 2006 ; Abdesselem et al., 2012 ). The comparison of ten countries, leading in GDP and performance of SDG 6 is shown in Fig. 1 .

Comparative performance of top 10 economies. Source: Sustainable Development Report 2021

Forty-six countries are outside the 80–100 bracket of achievement of ensuring basic drinking water provisions. Out of the 46 poorly performing countries, 28 countries are in the 60–80 bracket of achievement; 17 countries on the 40–60 bracket; and Chad is in the range of 20–40% achievement. 71 countries are outside the 80–100 bracket of achievement of ensuring basic sanitation provisions. 20 countries are in the 60–80 bracket; 16 countries are in the 40–60 bracket; 22 countries are in the 20–40 bracket and 13 countries are in 0–20 bracket of achievement.

These inequalities in the attainment of basic services of water and sanitation are alarming and smart initiatives towards sanitation goals are essential. The underdevelopment of economic activities, poor per capita GDP, poor per capita exports, and over dependencies in agriculture can be the major causes for the difference in the achievement of water and sanitation goals. The difference in culture, education, and skills, traditions, and habits may also be influential factors for the same.

The existing literature mainly concentrated on efforts to improve access, quality, and affordability of water. Several articles focused on challenges for achieving water and sanitation goals. The findings of this paper can be useful for academicians and scholars for researching SDG 6.

Future empirical studies are essential for concrete proof of the influence of the above factors on the attainment of water and sanitation goals. The analysis and discussion on SDG 6 are very important for the timely achievement of water and sanitation goals by 2030.

Research objectives

To understand the global status of achieving targets of SDG 6.

To consolidate the literature related to SDG 6 from the database of Web of Science.

To develop research themes for future research.

Research questions

What are the challenges for achieving the targets of SDG 6?

What are the initiatives for achieving the targets of SDG 6?

What is the indicator-wise performance of countries on achieving SDG 6?

This paper recommends research on the water and sanitation crisis faced by African countries. Further research can also be on measures for improving quality, access, and affordability for water and sanitation. Research can also be on solutions for problems and challenges faced in ensuring basic drinking water and sanitation for people across the world. The successful models and implementation strategies of leading nations can provide valuable insights for better implementation of policies and schemes. The policymakers and administrators can develop strategies for meeting various challenges associated with SDG 6, especially the challenges associated with the treatment of anthropogenic wastewater. Reforms of the industrial environment, investments, innovative technologies, strong political will, and leadership are essential for achieving the goals of anthropogenic wastewater treatment.

This paper has been divided into six chapters. The introduction of SDG 6 and performance at the global level is included in the first section. The review methodology and the major themes and sub-themes are discussed in the second section. Bibliometric results are discussed in the third section and a thematic analysis by rapid review is the fourth section of this paper. The future agenda for research is the fifth section and the conclusion of the paper is presented in the sixth section.

Review methodology

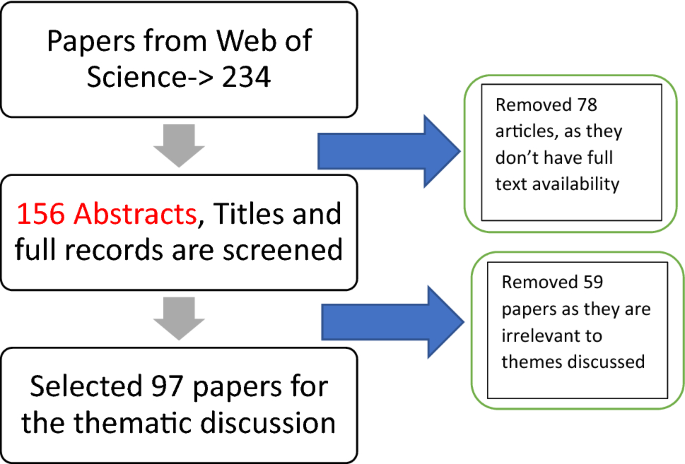

This review on SDG 6 is based on a single-source, Web of Science. Web of Science provides access to multiple databases, covering about 79 million records and 171 million platforms. Moreover, it covers over 256 disciplines. This single-source was used as it is one of the biggest databases of scientific papers and journals on sustainability and SDGs. The single-source-based model is successfully used in the review related to “Variations of the Kanban system” (Lage Junior and Godinho Filho, 2010 ); “review on environmental training in organisations” (Jabbour, 2013 ); and “systematic review on sustainable investments” (Talan and Sharma, 2019 ). The review frameworks and structure of this paper are adopted from the above three inspirational reviews, based on a single data source. Moreover, the review structure, and model adopted in the rapid review on “COVID-19 and Environmental Concerns” (Gagan Deep Sharma et al . , 2020 ) is another motivation behind design and structure of this review. The keywords "Sustainable Development Goal 6" and "SDG 6" are used on 01/07/2021 for drawing papers. 234 papers are obtained on the first query and used for the review. Thematic analysis was conducted after reading the title, abstract, and details. The details of paper selection are highlighted in Fig. 2 . This paper has followed PRISMA guidelines for paper selection. The criteria for paper and journal selection are that, it should be dealing with water and sanitation-related SDGs and the paper should be written after the introduction of sustainable development goals. This paper has conducted a bibliometric review and rigorous and rapid thematic analysis. Relevant papers of any country are included in this study, and there are no inclusion and exclusion criteria for selecting papers on the basis of country but done on the basis of relevance with the topic.

Paper identification and screening process

Bibliometric analysis was conducted on selected papers. The details of the bibliometric analysis are described in the following paragraphs.

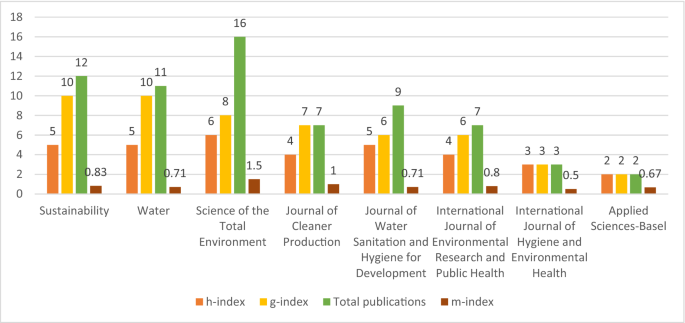

Journal analysis

The source analysis of the leading nine journals is shown in Fig. 3 . The journals are analyzed by h-index, g-index, and m-index, highlighting the source impact. “Science of the Total Environment” published articles related to water quality monitoring using citizen science, global water scarcity, microbial contamination in drinking water, water governance, seasonal drinking water quality, potential solutions for water security, inequality in access of water, water stress indicators, water crisis, and SDG 6 targets in Africa. “Water” focuses on water access, water supply networks, surface water extraction, groundwater vulnerability, integrated water resource management, water governance, water collecting systems, sanitation, fog water collection, remote-sensing technologies, water footprints, and domestic demand and supply of water. The themes published in “Sustainability” are related to water supply networks, use of citizen science monitoring for water-related goals, access to sanitation, citizen and educational initiatives, water supply tariffs, water service sustainability, cross country water co-operations, and water quality governance. The “Journal of Environmental Management” took interest in publishing topics related to fecal sludge management, sanitation, citizen science in sanitation, and water treatment systems. “Journal of Cleaner Production” published on industrial wastewater, groundwater quality, rainwater harvesting, smart waste management systems, and impact of urbanization on water infrastructure. The major themes published in “Journal of Water, Sanitation and Hygiene for Development” are hygiene in healthcare facilities, application of decision support system for attaining water and sanitation targets, urban sanitation, water quality, shared sanitation, toilet waste management, access and affordability of water, and need for behavioral changes for attaining water and sanitation targets. The topics published in “International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health” are related to drinking water and health; sanitation and solid waste management. Fecal pathogen flow and health risks, and innovative sources for clean water are the topics published on the “International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health”. The major works on water and sanitation goals in the journal “Applied Sciences-Basal” are related to soil aquifer treatments, rural water supply, groundwater salinity, and fluoride content in groundwater.

Top journals and source impact

Analysis of authors

Kalin Robert M (University of Strathclyde, Scotland) is the leading researcher on topics related to SDG 6. Twelve documents (all 12 documents are open access) have been written by this author on topics related to SDG 6, with a total of 50 citations and an average citation of 4.17. These 12 documents are published in the years 2021 (2 articles), 2020 (7 articles), and 2019 (2 articles). The h-index of these articles is four. The other influential author of this research domain is Rivett Michael O (University of Strathclyde, Scotland). The author has written nine articles (all 9 documents are open access) with a total citation of 41 and an average of 4.6 citations per article. These nine articles are published in 2021 (2 articles), 2020 (4 articles), and 2019 (3 articles). The h-index of these articles is four.

Both the authors had co-authored nine articles. Four articles had been published in the journal “Water” and obtained 18 citations. The articles in “Water” dealt with groundwater vulnerability (Addison et al., 2020a , b ), integrated water resource management (Banda et al., 2019 ; Banda et al., 2020 ), and stranded asset-based investment strategies for SDG 6 (Kalin et al., 2019 ); three articles are on Applied Science-Basel and got six citations. The articles in this journal focused on focusing on sustainable rural water supply (Leborgne et al., 2021 ), groundwater salinity and rural water supply challenges (Rivett et al., 2020 ), and Human and health implications of Fluoride content in groundwater (Addison et al., 2020a , b ), one article on Sustainability are without any citations. The articles focused on the cost of sustainable water supply through network kiosks (Coulson et al., 2021 ) and the article published on Science of the Total Environment (17 citations). This article is related to salinity in aquifers and technologies beyond hand-pumps (Rivett et al., 2019 ).

The individual publications of Kalin Robert M include an article on rural water supply tariffs, published in the journal “Sustainability” with six citations (Truslove et al., 2020 ); one article each on Environmental Science Water Research Technology (1 citation) dealt with barriers to hand pump serviceability in Malawi (Truslove et al., 2020 ); and Journal of Hydrology Regional Studies (2 citations), article related to transboundary aquifers (Fraser et al., 2020 ).

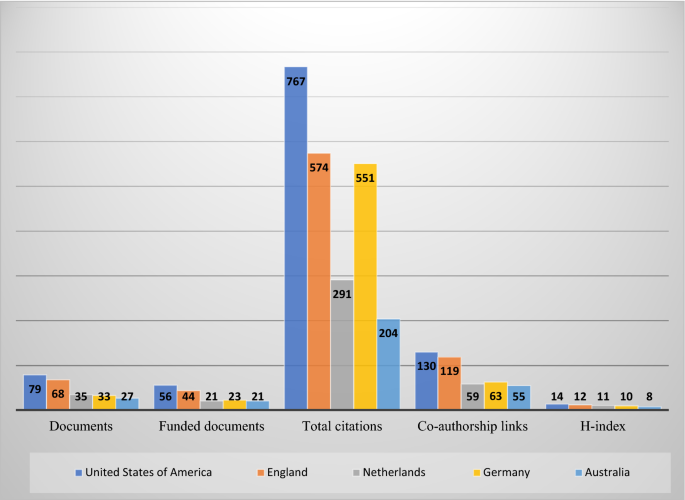

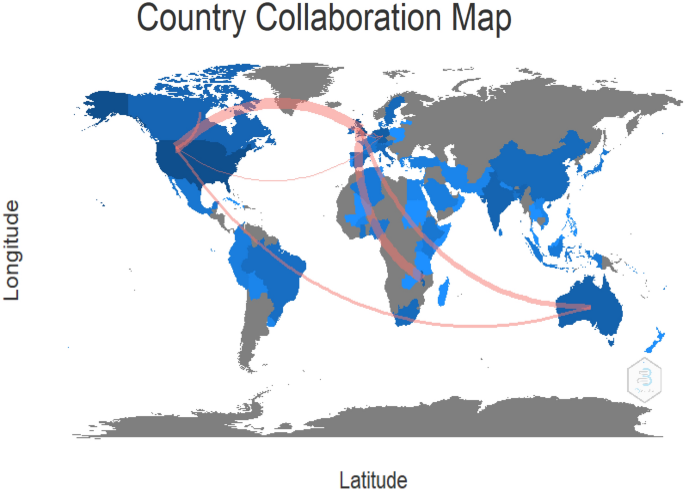

Analysis of countries

The existing literature mainly focused on countries struggling with water and sanitation goals, especially African countries. The contribution of the top five countries has been evaluated on the parameters of several documents, funded documents, total citations, average citations, co-authorship links, and h-index in Fig. 4 . The research collaborations of countries are shown in Fig. 5 . The country collaboration map also shows the most prominent countries. The most prominent countries are in dark blue, and by this, the most influential countries are the United States of America and England. The United States of America is the most influential country in terms of document publications, citations, funded documents, co-authorship links, and h-index (Table 1 ).

Summary of contributions of top five countries on research related to SDG 6

Country collaboration map

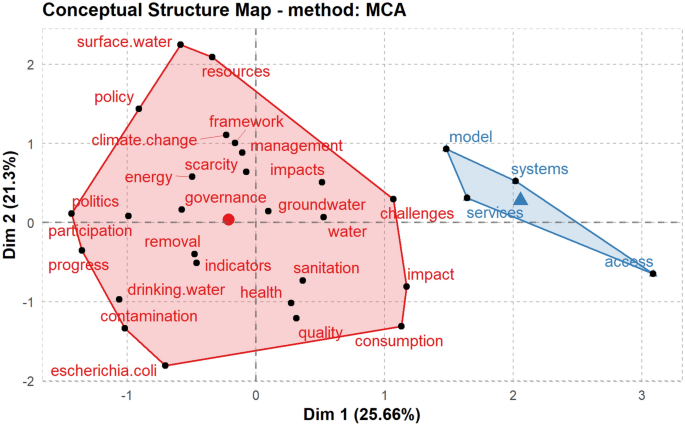

Keyword analysis

The keyword analysis was shown in the conceptual structure map, as shown in Fig. 6 . The most prominent keywords are shown in sanitation (5 occurrences), water (3 occurrences), sustainable development goals (20 occurrences), SDG 6 (15 occurrences), water quality (5 occurrences), groundwater (7 occurrences), and drinking water (3 occurrences). The details of articles details and keywords are provided in the supplementary files.

Conceptual structure map

Scholarships

The leading funding agencies, offering sponsorship for research related to SDG 6 targets for basic drinking water, sanitation, and wastewater treatments are the UK Research Innovation (UKRI) of the United Kingdom, Bill Melinda Gates Foundation of the United States of America, and European Commission. UK Research Innovation (UKRI) of the United Kingdom funded projects on water quality, remote monitoring of water systems in rural areas, governance issues, seasonal drinking water quality, and water resources. Bill Melinda Gates Foundation of the United States of America funded projects on the fecal sludge management system, water quality, and sanitation. The funded projects of the European Union are related to industrial wastewater, ecosystem services, drinking water, sanitation, and crop-water productivity.

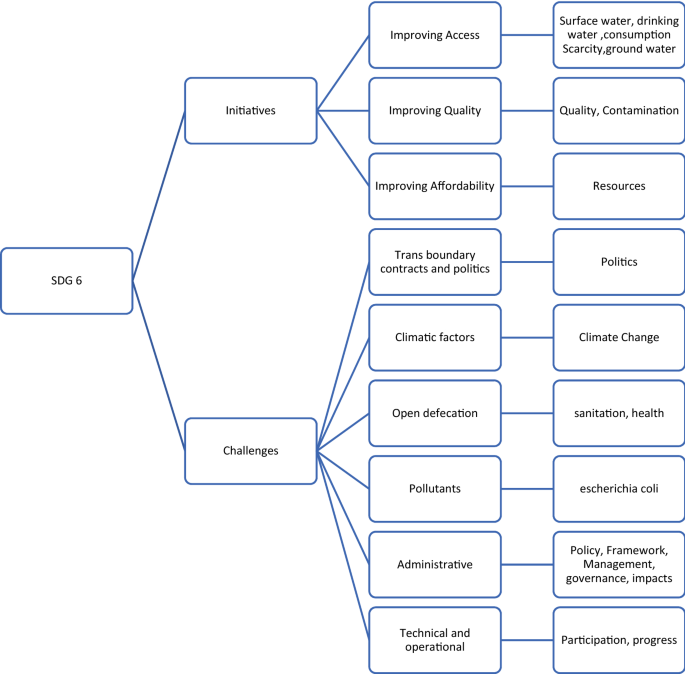

Thematic discussion

The major themes and sub-themes as shown in Fig. 7 have been described in this section. The major themes of research in SDG 6 are initiatives and challenges. The major niches for research on initiatives are the efforts for improving access, quality, and affordability. Similarly, the major sub-themes of research regarding challenges of SDG 6 are pollutants, transboundary contracts, politics, climate factors, open defecation, administrative challenges, operational challenges, and technical challenges.

Key themes, sub-themes, and associated keywords

Initiatives in favor of SDG 6 goals

Several initiatives has been researched and documented, towards the attainment goals of SDG 6. The initiative can be for improving access, quality, and affordability of clean water. These three concepts are taken as sub-themes under the initiatives in favor of SDG 6. There is positive news related to access to water, but the quality and affordability of water and sanitation remain a serious challenge and it defeats the objective of access to clean water (Coulson et al., 2021 ) (Mitlin and Walnycki, 2020 ). All these three factors are interlinked and should be existing for the successful attainment of SDG 6 (Diaz-Alcaide et al., 2021 ). Water and sanitation taxes, the density of population, revenue of the local government, and income of local people can also be crucial factors for the attainment of SDG 6 (Martinez-Cordoba et al., 2020 ). Similarly, active forums can play a significant role in the attainment of SDG 6 (Paerli and Fischer, 2020 ).

The SDG 6 should be achieved across all cross-sections of society including involuntarily displaced sections of society (Behnke et al., 2018 ). SDG 6 is heavily linked with health-related goals. The initiatives for quality health are related to the availability of clean water and sanitation goals (SDG 6). The prime focus should be on ensuring sanitation, cleanliness, and hygiene in healthcare facilities and proper waste management for prevention and control of infections (Torres-Slimming et al., 2019 ; Abu and Elliott, 2020 ; Abu et al., 2021 ). The improvement in the access and quality of water and sanitation services includes the development of an integrated water database, measuring the cost and affordability (Bressler and Hennessy, 2018 ).

Efforts for improving access

There are several challenges to ensuring access to clean water (Marshall and Kaminsky, 2016 ). One such challenge is the problems associated with fecal sludge management systems. Fecal sludge management is posing a severe threat to the goals of clean water and sanitation, which directly hinders the efforts for access to clean water and sanitation (Devaraj et al., 2021 ; Yesaya and Tilley, 2021 ). The major factors affecting access to clean water are collection time, distance from the household, water quality, affordability, and reliability of water sources, etc. (Diaz-Alcaide et al., 2021 ). The supply of water in the majority of places is intermittent water supply and has several challenges to provide complete access to clean water and achieving SDG 6. This points out the need for migration to a continuous supply of clean water and a hybrid hydraulic model in this regard was developed (El Achi and Rouse 2020 ).

The model of distribution is a challenge in the case of drinking water and the conflict on the model of distribution of water between formal and informal suppliers should be addressed with innovative hybrid models (Agbemor and Smiley, 2021 ). Alternative policies and partnership models would be the key to enhancing access to clean water. Replacement of public distribution models by community-based water supply models together with increased local monitoring of policies and implementations is recommended as a solution for improving access to clean water in Sub-Saharan Africa (Adams et al., 2019 ). A similar shift from the government-regulated water supply chain to unregulated systems is visible in the research outcomes (Fischer et al., 2020 ). The application of the decision support system for the selection of best water and sanitation technology can improve the access of clean water facilities and sanitation (Bouabid and Louis, 2021 ); similarly, the Earth observation and cloud computing for the attainment of SDG 6 targets (Li et al., 2020 ). The promotion of public standpipes, community boreholes, and household water treatments can be some measures towards access to clean and safe water (Abubakar, 2019 ). Rainwater harvesting can be a suitable and economical alternative for improving access to clean water (Dao et al., 2017 ; Alim et al., 2020 ; Bui et al., 2021 ).

The key water management strategies recommended for improving access to water are importing virtual water; water reallocation; strengthening of law and integrated basin management, creation of water market and wastewater network and treatment facilities, and reusing wastewater (Banihabib et al., 2020 ). The other suggestions for improving access for water are water foot prints (Berger et al., 2021 ); integrated water resource management and fresh water health index (Bezerra et al., 2021 ); shared sanitation (Foggitt et al., 2019 ); aquifer recharge and treatment measures (Gronwall and Oduro-Kwarteng, 2018 ); asset audit and using stranded assets for ensuring access of water (Kalin et al., 2019 ); fog water collections is an alternative strategy for improving the access for clean water (Lucier and Qadir, 2018 ; Qadir et al., 2018 ); however, the main challenges in fog water harvesting are lack of expertise, support, affordability, and inequalities (Qadir et al., 2018 ); water service franchising and distribution of bottled water (Walter et al., 2017 ; Lyne, 2020 ); rain water harvesting, water treatment, better distribution and water recharging (Udmale et al., 2016 ); desalination and wastewater reuse (Van Vliet et al., 2021 ); use of smart pumps can enhance the usage and monitoring of water sources and thereby move close towards the goal of improving access for clean water (Swan et al., 2018 ).

Efforts for improving quality and affordability

A framework for water quality and usage monitoring is developed (Charles et al., 2020 ). Similarly, water quality indices can be used for improving the quality of water by restricting the pollutants in water (Bouhezila et al., 2020 ); a scorecard is developed for monitoring the major dimensions of access, availability, quality, acceptability, and affordability of clean water sources (Ezbakhe et al., 2019 ).

A study covering 63% of green star hotels in Egypt had claimed that green hotel practices like energy saving, optimized water consumption, waste management, and waste reduction can positively contribute to the attainment of SDG 6. This can significantly improve the quality of drinking water (Abdou et al., 2020 ). Water quality monitoring is a major challenge (Cronin et al., 2017 ). Appropriate measures for reduced discharge of untreated pharmaceutical contents in wastewater and better treatment of the same can be some measures towards improving the quality of water and waste management (Acuna et al., 2020 ). The use of citizen science can be a strong alternative for efficient monitoring of SDG 6 and thereby quality improvement economically and conveniently (Bishop et al., 2020 ; Capdevila et al., 2020 ; Fraisl et al., 2020 ; Freihardt, 2020 ; Hegarty et al., 2021 ).

The other measures for improving water quality include monitoring sanitation progress through total service gap (Kempster and Hueso, 2018 ); rural–urban water link, wastewater treatment, and reuse, efficient water quality monitoring, innovative ways of fecal management, and change in community behaviors (Kookana et al., 2020 ); local groundwater balance model for groundwater monitoring (Lopez-Maldonado et al., 2017 ); chlorination of drinking water at the point of the collection can be some measures towards the quality improvement of water (Pickering et al., 2019 ); policy implementation, proper monitoring, and data management are key to improvement of quality (Roy and Pramanick, 2019 ); monitoring, treatment, and education and training of water-related technology (Sogbanmu et al., 2020 ).

The issue of affordability of clean water is closely connected with water-related emotional distress. Research has found that emotional challenges can be developed due to poor affordability to water, despite the access and quality (Thomas and Godfrey, 2018 ).

Challenges for the attainment of SDG 6

Several studies across the globe have identified the challenges for access to safe and clean water; clean water, sanitation, and hygiene are in heavily associated with health-related goals (Anthonj et al., 2018 ).

Challenges associated with pollutants, transboundary contracts, climate, open defecation, and politics

The major challenge for the attainment of SDG 6 can be untreated pharmaceutical contents in wastewater (Acuna et al., 2020 ). The discharge of untreated pollutants to water can be a serious threat to access and quality of water (Bouhezila et al., 2020 ). The other challenges associated with pollutants can be a high concentration of fluoride content in weathered basement aquifers, which increases the risk of dental fluorosis (Addison et al., 2020a , b ; Banda, et al., 2020 ); increased levels of Cadmium and Chromium in water sources can also pollute the water sources and increase the risk of non-communicable disease like cancer (Ahmed and Bin Mokhtar, 2020 ); nitrate and phosphate levels can pollute the water (Hegarty et al., 2021 ). The salinity of the water is a major challenge for clean water (Rivett et al., 2019 ; Rivett et al., 2020 ); contamination of water resources through human and animal fecal matter (Buckerfield et al., 2020 ); E. coli contamination (Usman et al., 2018 ; Charles et al., 2020 ) chlorine content, usage of latrine waste as fertilizer and wastewater discharge (Mraz et al., 2021 ); nitrogen and phosphorous content (Van Puijenbroek et al., 2019 ). The fecal contamination, poor sanitation services, and the presence of no fecal matter in fecal sludge (Hurd et al., 2017 ; Quarshie et al., 2021 ).

Politics is an important determinant in ensuring access to clean water, especially in tension-laden areas. The relations of Palestine and Israel can be crucial in the attainment of SDG 6 goals in Palestine (Al-Shalalfeh et al., 2018 ). Hydro-political risks are another issue affecting the SDG 6 and strong transboundary co-operations are essential for the peaceful access of water in the future (Farinosi et al., 2018 ; Hussein et al., 2018 ; Wright-Contreras, 2019 ; Fraser et al., 2020 ; Jimenez et al., 2020 ; Strokal, 2021 ; Yalew et al., 2021 ). Unfavorable climatic factors are major challenges to water and sanitation-related goals (Hurd et al., 2017 ; Fleming et al., 2019 ; Darwish et al., 2021 ). Negative environmental impacts and population pressures are serious threats for SDG 6 (Salmoral et al., 2020 ). Open defecation is a serious challenge for SDG 6, and the major factors promoting open defecation are found to be the poor promotion of programs at the field level, intimidation of adults, and lack of support in families (Akov and Satwah, 2019 ).

Administrative, technical, and operational challenges

Integrated water resource management is the key to the successful attainment of SDG 6. Despite best efforts for improving access and quality of water, ensuring an integrated water management system is still a challenge (Al-Noaimi, 2020 ). The other administrative challenges can be poor water management and investments, corruption (Adams et al., 2019 ); poor institutional capabilities and fear of failure in monitoring (Rayasam et al., 2020 ) infrastructure-related challenges, and funding and policy challenges (Nhamo et al., 2019 ; Romano and Akhmouch, 2019 ).

The major technical and operational challenges can be the unprotected sources of water and poor coverage of piped water connections (Usman et al., 2018 ; Abubakar, 2019 ). Scarcity of water, rapidly growing populations, unsustainable development, poor management in the usage of water, lack of technical, financial, and institutional performances (Al-Noaimi, 2020 ). Another serious issue to be addressed is the inequality in access to drinking water (Anthonj et al., 2020 ). The issues of capacity shortages and poor law enforcement (Darwish et al., 2021 ); poor accountability and complex governance structure (Gronwall, 2016 ); administration challenges, conflicting goals of other indicators, challenges in local implementation of global goals (Herrera, 2019 ).

The other technical issues include the unaffordability of water and poor coordination of responsibilities (Jama and Mourad, 2019 ); poor latrine constructions and seasonal flooding (Jewitt et al., 2018 ); political will, poor economic background, poor environmental and manpower development, attitude and lack of will of administrative and legislative systems; and poor technological tools are challenges proper water governance (Mycoo, 2018 ); technical, scale and operational efficiencies of water utilities are a serious challenge for goals of clean water (Ngobeni and Breitenbach, 2021 ); installation failures, damages, poor maintenance, non-availability of spare parts and affordability issues and financial constrains (Truslove et al., 2020 ; Coulson, et al., 2021 ); issues associated with poor infrastructure (Udmale et al., 2016 ); affordability, markets, and behavior are the strongest barriers for attainment of SDG 6 (Wight et al., 2021 ) The poor human development, capacity challenges for monitoring sanitation and lack of sufficient data for monitoring and wrong conclusions are creating challenges for SDG 6 (Rahaman et al., 2021 ; Komakech et al., 2019 ; Kirschke et al., 2020 ); behavioral issues, barriers, and habits are posing severe threat to attainment of SDG 6 goals (Mathew et al., 2020 ).

Research suggestions

By reviewing the existing literature, future research can be on improving access, affordability, and quality of drinking water provisions and sanitation. The research on wastewater treatment is an unexplored area. More, specifically, the future research can be in drinking water provisions of African countries; sanitation provisions of African and low-income countries, and the research can be in the wastewater treatment provisions of any countries except a few, those had attained the targets. The detailed agenda for future research has been included in the following section.

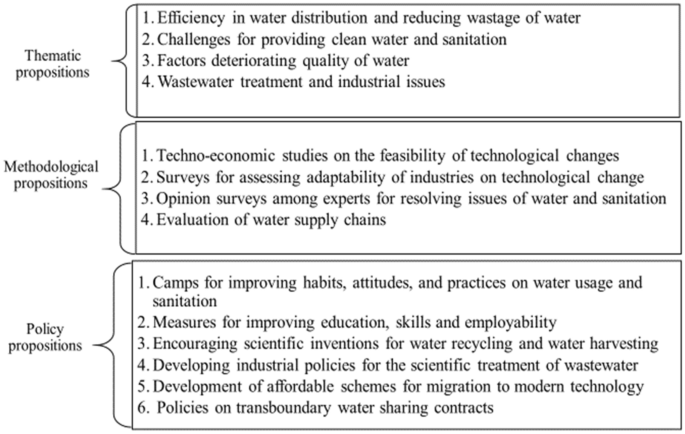

Future research agenda

The existing literature points out the various ways of water wastage and pitfalls in water distribution. This badly affects the access to clean drinking water provisions. Future research can be for various methods for improving access to clean water by controlling wastage of water and improving water supply chains. Several studies had been country-based and the wider acceptance of those concepts and theory validation can be done by extending those country-based studies to similar countries facing challenges on clean water. Future research can be on reducing discharge pollutants, innovative solutions for facilitating treatment for anthropogenic wastewater. Future research can also be on measures for reducing these pollutants and initiating policy measures, the scope for technology changes to control the water pollution.

Research on behavioral changes, affordability, and awareness can be conducted to stop the open defecation practices. Future research can be on developing awareness programs, hygiene and sanitation camps. Empirical studies on the role of education and economic development in solving water and sanitation goals can throw light on the connection between literacy, exports, income, and other related variables on the achievement of water and sanitation goals.

Research can be on international politics and transboundary contracts for improving accessibility to water. The policy initiatives for peaceful contracts, improving the proportion of transboundary contracts can be the future actions for the sustainability of water sources.

The water and sanitary goals are at the mercy of climate in many places. This condition should be changed and future research can be developing climate-resistant initiatives and policies for water security and sanitation. Proper policy initiatives and reform models can be developed in the future to tackle several administrative, technical, and operational challenges. Future research can be for solutions for challenges and constraints related to funding, technology, and skill management associated with water and sanitation goals.

Several technological solutions and innovative strategies for water and sanitation improvement has been documented in the existing literature and future research can be on techno-economic feasibility and practicality in solving the challenges associated with SDG 6. Researches can also be on industrial adaptability to these technological changes. The highlights of the future agenda for research are shown in Fig. 8 .

Conclusions

Access to clean and safe drinking water, sanitation, and proper hygiene are very essential for sustainable living. However, a significant section of the global population is outside the basic facilities for drinking water, sanitation, and hygiene. SDG 6 focuses on the targets of ensuring basic drinking facilities, sanitation, and treatment facilities for wastewater for all. This paper has been tailored to understand the status of water and sanitation-related targets of SDG 6 by consolidating the literature from Web of science and other external sources. Both thematic analysis and bibliometric analysis of existing literature on SDG 6 have been conducted and the future scope for research is discussed. This research on the status of water and sanitation-related goals has found that the provision for drinking water had been reached to the majority of the global population except in few countries of the African region. The poor achievement of targets related to the treatment of wastewater and sanitation is also a global concern.

Even though the implementations are at the country level, this paper invites the need for global attention for solving the challenges of poorly performing regions, especially the African continent, which struggles for provisions of water, sanitation, and wastewater treatment. Out of 54 countries in the continent, 45 countries are lagging to provide basic drinking water solutions. In the case of sanitation, there are 13 countries where more than 70% of the population are outside the provisions for basic sanitation facilities. Similarly, there are 16 African countries with provision of wastewater treatment below 2%. The Asian countries are relatively better performing in respect of providing provisions for drinking water, except Afghanistan and Yemen. Thirteen Asian countries are struggling for providing basic sanitation facilities for the population. All Asian countries except Israel, Bahrain, and Singapore are well behind in the achievement of providing proper facilities for the treatment of anthropogenic wastewater. All the European countries are in above 75% achievement brackets in respect of provisions for basic drinking water facilities and basic sanitation facilities. The 18 European countries are in the 80–100 achievement bracket and the remaining 26 countries are lagging in respect of providing basic provisions for the treatment of anthropogenic wastewater. All the North American and Latin American countries are in 80–100 brackets in providing provisions for basic drinking water and in respect of sanitation, except Bolivia (60.7% achievement) and Nicaragua (74.4% achievement). However, the performance of North American and Latin American countries in providing provisions for wastewater treatment is not robust except Chile (71.9%) and Canada (67.4).

The underachievement of targets related to wastewater treatment is still a global concern except for a few countries. What are the challenges and reasons for this underachievement of water and sanitation goals? This review of scientific papers from the Web of Science database points out the major challenges as water and sanitation taxes, high density of population, resource constraints of local government, poor fecal sludge management practices, long wait for collecting water, pollutants and poor wastewater treatment, transboundary contracts and politics, climatic factors, open defecation, and administrative, technical, and operational challenges.

The literature provides several solutions to water and sanitation targets by engagement of active forums; use of integrated water database; recharging and treatment of; decision support systems; rainwater harvesting; desalination and wastewater reuse; smart pumping; water reallocation; strengthening of law and integrated basin management, creation of water market and wastewater network; asset audit; fog water collections; and chlorination of drinking water.

The outcomes of this paper can be a strong motivation for developing policies for the improvement of skill sets and education of the local population, which can economically empower the poor and enhance their affordability to water and sanitation solutions. Similarly, the awareness related to sanitation, hygiene, water recycling, need for reducing water consumption, and preservation are inevitable in inculcating a new culture among people. Moreover, this paper recommends strengthening the water and sanitation supply chain by streamlining water distribution, reducing wastages, and scientifically treating the wastewater. The performance of global economies towards the treatment of anthropological wastewater is discouraging. Strong policy actions based on research should be initiated to improve the provisions for the treatment of anthropological wastewater. Academicians and scholars can use the outcomes of this paper for enhancing their research networks and developing new themes for research. This paper had recommended several thematic, methodological, and policy propositions for the attainment of sustainable development goal 6-related targets by 2030. The future themes specified in this paper can be used for taking scholarships and funded projects related to water, sanitation, hygiene, and sustainability of water resources.

Scholarships and funded projects can be targeted in the research related to providing solutions for anthropological wastewater treatment, technologies, implementation plans, and associated policy reforms. Future research should consider the avoidable challenges and develop inclusive reforms by taking care of all stakeholders. Scholars can focus on the African continent and some pockets of Asia and Latin America, the regions faced by acute shortage for drinking water and sanitation. Future projects can be on the solutions for improving access, affordability, and improving quality of basic provisions for water and sanitation. Minor projects can also be on the achievement strategies on drinking water and sanitation by European and North American countries.

The research outcomes of this paper should be read along with the limitations of using secondary sources. Similarly, the scope for future research and scholarships are not offers but the outcomes of thematic and bibliometric analysis.

Abdesselem K et al (2012) Wastewater discharge impact on groundwater quality of Béchar city. An anthropogenic activities mapping approach, Southwestern Algeria. Procedia Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.proeng.2012.01.1200

Article Google Scholar

Abdou AH, Hassan TH, El Dief MM (2020) A description of green hotel practices and their role in achieving sustainable development. Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12229624

Abu TZ, Elliott SJ (2020) When it is not measured, how then will it be planned for? WASH a critical indicator for universal health coverage in Kenya. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165746

Abu TZ, Elliott SJ, Karanja D (2021) When you preach water and you drink wine’: WASH in healthcare facilities in Kenya. J Water Sanit Hyg Dev. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2021.238

Abubakar IR (2019) Factors influencing household access to drinking water in Nigeria. Utilit Policy 58:40–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jup.2019.03.005

Acuna V et al (2020) Management actions to mitigate the occurrence of pharmaceuticals in river networks in a global change context. Environ Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105993

Adams EA, Sambu D, Smiley SL (2019) Urban water supply in Sub-Saharan Africa: historical and emerging policies and institutional arrangements. Int J Water Resour Dev 35(2):240–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2017.1423282

Addison MJ, Rivett MO, Phiri P, Mleta P, Mblame E, Banda M et al (2020a) Identifying groundwater fluoride source in a weathered basement aquifer in Central Malawi: human health and policy implications. Appl Sci Basel. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10145006

Addison MJ, Rivett MO, Phiri P, Mleta P, Mblame E, Wanangwa G et al (2020b) Predicting groundwater vulnerability to geogenic fluoride risk: a screening method for Malawi and an opportunity for national policy redefinition. Water. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12113123

Agbemor BD, Smiley SL (2021) Tensions between formal and informal water providers: receptivity toward mechanised boreholes in the Sunyani west district, Ghana. J Dev Stud 57(3):383–399. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2020.1786059

Ahmed MF, Bin Mokhtar M (2020) Assessing cadmium and chromium concentrations in drinking water to predict health risk in Malaysia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082966

Akov T, Satwah S (2019) Children unwelcome—socio-physical study of children’s community toilets usage in Mumbai’s slums. Eur J Sustain Dev 8(3):20–30. https://doi.org/10.14207/ejsd.2019.v8n3p20

Alim MA et al (2020) Feasibility analysis of a small-scale rainwater harvesting system for drinking water production at Werrington, New South Wales, Australia. J Clean Prod. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.122437

Al-Noaimi MA (2020) SDG goal 6 monitoring in the Kingdom of Bahrain. Desalin Water Treat 176:406–427. https://doi.org/10.5004/dwt.2020.25552

Al-Shalalfeh Z, Napier F, Scandrett E (2018) Water Nakba in Palestine: sustainable development goal 6 versus Israeli hydro-hegemony. Local Environ 23(1):117–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2017.1363728

Anthonj C et al (2018) Health risk perceptions are associated with domestic use of basic water and sanitation services-evidence from rural Ethiopia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15102112

Anthonj C et al (2020) Geographical inequalities in drinking water in the Solomon Islands. Sci Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.1115241

Banda LC et al (2019) Water-isotope capacity building and demonstration in a developing world context: isotopic baseline and conceptualization of a Lake Malawi catchment. Water (switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/w11122600

Banda LC et al (2020) Seasonally variant stable isotope baseline characterisation of Malawi’s shire river basin to support integrated water resources management. Water. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12051410

Banihabib ME et al (2020) Prioritization of sustainable water management strategies in arid and semi-arid regions using swot coupled ahp technique in addressing SDGs. Acta Sci Pol Form Circum 19(2):35–52

Behnke N et al (2018) Improving environmental conditions for involuntarily displaced populations: water, sanitation, and hygiene in orphanages, prisons, and refugee and IDP settlements. J Water Sanit Hyg Dev 8(4):785–791. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2018.019

Berger M et al (2021) Advancing the water footprint into an instrument to support achieving the SDGS—recommendations from the “Water as a global resources—research initiative (GRoW). Water Resour Manag 35(4):1291–1298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11269-021-02784-9

Bezerra MO et al (2021) Operationalizing integrated water resource management in Latin America: insights from application of the freshwater health index. Environ Manag. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-021-01446-1

Bishop IJ et al (2020) Citizen science monitoring for sustainable development goal indicator 6.3.2 in England and Zambia. Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410271

Bondur VG, Grebenuk YV (2001) Remote indication of anthropogenic influence on marine environment caused by depth wastewater plum: modeling, experiments. Issledovanie Zemli Iz Kosmosa 6:49–68

Google Scholar

Bouabid A, Louis G (2021) Decision support system for selection of appropriate water supply and sanitation technologies in developing countries. J Water Sanit Hyg Dev 11(2):208–221. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2021.203

Bouhezila F, Hacene H, Aichouni M (2020) Water quality assessment in Reghaia (North of Algeria) lake basin by using traditional approach and water quality indices. Kuwait J Sci 47(4):57–71

Bressler JM, Hennessy TW (2018) Results of an Arctic council survey on water and sanitation services in the Arctic. Int J Circumpolar Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/22423982.2017.1421368

Buckerfield SJ et al (2020) Chronic urban hotspots and agricultural drainage drive microbial pollution of karst water resources in rural developing regions. Sci Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140898

Bui TT et al (2021) Rainwater as a source of drinking water: a resource recovery case study from Vietnam. J Water Process Eng. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwpe.2020.101740

Capdevila ASL et al (2020) Success factors for citizen science projects in water quality monitoring. Sci Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.137843

Charles KJ, Nowicki S, Bartram JK (2020) A framework for monitoring the safety of water services: from measurements to security. NPJ Clean Water. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41545-020-00083-1

Coulson AB et al (2021) The cost of a sustainable water supply at network kiosks in Peri-Urban Blantyre, Malawi. Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13094685

Cronin AA et al (2017) Piloting water quality testing coupled with a national socioeconomic survey in Yogyakarta province, Indonesia, towards tracking of sustainable development goal 6. Int J Hyg Environ Health 220(7):1141–1151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.07.001

Dao AD, Nguyen DC, Han MY (2017) Design and operation of a rainwater for drinking (RFD) project in a rural area: case study at cukhe elementary school, Vietnam. J Water Sanit Hyg Dev 7(4):651–658. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2017.055

Darwish T et al (2021) Sustaining the ecological functions of the Litani river basin, Lebanon. Int J River Basin Manag. https://doi.org/10.1080/15715124.2021.1885421

Devaraj R et al (2021) Planning fecal sludge management systems: challenges observed in a small town in southern India. J Environ Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111811

Diaz-Alcaide S et al (2021) Mapping ground water access in two rural communes of Burkina Faso. Water. https://doi.org/10.3390/w13101356

El Achi N, Rouse MJ (2020) A hybrid hydraulic model for gradual transition from intermittent to continuous water supply in Amman, Jordan: a theoretical study. Water Supply 20(1):118–129. https://doi.org/10.2166/ws.2019.142

Ezbakhe F, Giné-Garriga R, Pérez-Foguet A (2019) Leaving no one behind: evaluating access to water, sanitation and hygiene for vulnerable and marginalized groups. Sci Total Environ 683:537–546. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.207

Farinosi F et al (2018) An innovative approach to the assessment of hydro-political risk: a spatially explicit, data driven indicator of hydro-political issues. Glob Environ Change 52:286–313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.07.001

Fischer A et al (2020) Risky responsibilities for rural drinking water institutions: the case of unregulated self-supply in Bangladesh. Glob Environ Change Hum Policy Dimens. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102152

Fleming L et al (2019) Urban and rural sanitation in the Solomon Islands: how resilient are these to extreme weather events? Sci Total Environ 683:331–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.05.253

Foggitt E et al (2019) Experiences of shared sanitation—towards a better understanding of access, exclusion and ‘toilet mobility’ in low-income urban areas. J Water Sanit Hyg Dev 9(3):581–590. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2019.025

Fraisl D et al (2020) Mapping citizen science contributions to the UN sustainable development goals. Sustain Sci 15(6, SI):1735–1751. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-020-00833-7

Fraser CM et al (2020) A national border-based assessment of Malawi’s transboundary aquifer units: towards achieving sustainable development goal 6.5.2. J Hydrol Reg Stud. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrh.2020.100726

Freihardt J (2020) Can citizen science using social media inform sanitation planning? J Environ Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.110053

Gagan Deep Sharma et al (2020) COVID-19 and environmental concerns: a rapid review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 148(January)

Gelsomino A et al (2006) Changes in chemical and biological soil properties as induced by anthropogenic disturbance: a case study of an agricultural soil under recurrent flooding by wastewaters. Soil Biol Biochem 38(8):2069–2080. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soilbio.2005.12.025

Gronwall J (2016) Self-supply and accountability: to govern or not to govern groundwater for the (peri-) urban poor in Accra, Ghana. Environ Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-016-5978-6

Gronwall J, Oduro-Kwarteng S (2018) Groundwater as a strategic resource for improved resilience: a case study from peri-urban Accra. Environ Earth Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-017-7181-9

Hegarty S et al (2021) Using citizen science to understand river water quality while filling data gaps to meet United Nations sustainable development goal 6 objectives. Sci Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.146953

Herrera V (2019) Reconciling global aspirations and local realities: challenges facing the sustainable development goals for water and sanitation. World Dev 118:106–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.02.009

Hurd J et al (2017) Behavioral influences on risk of exposure to fecal contamination in low-resource neighborhoods in Accra, Ghana. J Water Sanit Hyg Dev 7(2):300–311. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2017.128

Hussein H, Menga F, Greco F (2018) Monitoring transboundary water cooperation in SDG 6.5.2: how a critical hydropolitics approach can spot inequitable outcomes. Sustainability (switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/su10103640

Jabbour CJC (2013) Environmental training in organisations: from a literature review to a framework for future research. Resour Conserv Recycl 74:144–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2012.12.017

Jama AA, Mourad KA (2019) ‘Water services sustainability: institutional arrangements and shared responsibilities. Sustainability (switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/su11030916

Jewitt S, Mahanta A, Gaur K (2018) Sanitation sustainability, seasonality and stacking: Improved facilities for how long, where and whom? Geogr J 184(3):255–268. https://doi.org/10.1111/geoj.12258

Jimenez A et al (2020) Unpacking water governance: a framework for practitioners. Water. https://doi.org/10.3390/w12030827

Kalin RM et al (2019) Stranded assets as a key concept to guide investment strategies for sustainable development goal 6. Water (switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/w11040702

Kempster S, Hueso A (2018) Moving up the ladder: assessing sanitation progress through a total service gap. Water (switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/w10121735

Kirschke S et al (2020) Capacity challenges in water quality monitoring: understanding the role of human development. Environ Monit Assess. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10661-020-8224-3

Komakech HC et al (2019) What proportion counts? Disaggregating access to safely managed sanitation in an emerging town in Tanzania. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16183328

Kookana RS et al (2020) Urbanisation and emerging economies: issues and potential solutions for water and food security. Sci Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139057

Lage Junior M, Godinho Filho M (2010) Variations of the Kanban system: literature review and classification. Int J Prod Econ 125(1):13–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2010.01.009

Leborgne R et al (2021) True 2-D resistivity imaging from vertical electrical soundings to support more sustainable rural water supply borehole siting in Malawi. Appl Sci Basel. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11031162

Li W et al (2020) Earth observation and cloud computing in support of two sustainable development goals for the river nile watershed countries. Remote Sens. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs12091391

Lopez-Maldonado Y et al (2017) Local groundwater balance model: stakeholders’ efforts to address groundwater monitoring and literacy. Hydrol Sci J 62(14):2297–2312. https://doi.org/10.1080/02626667.2017.1372857

López-Pacheco IY et al (2019) Anthropogenic contaminants of high concern: existence in water resources and their adverse effects. Sci Total Environ 690:1068–1088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.07.052

Lucier KJ, Qadir M (2018) Gender and community mainstreaming in fog water collection systems. Water. https://doi.org/10.3390/w10101472

Lyne I (2020) Bottling water differently, and sustaining the water commons? Social innovation through water service franchising in Cambodia. Water Altern 13(3, SI):731–751

Marshall L, Kaminsky J (2016) When behavior change fails: evidence for building wash strategies on existing motivations. J Water Sanit Hyg Dev 6(2):287–297. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2016.148

Martinez-Cordoba P-J et al (2020) Achieving sustainable development goals. Efficiency in the Spanish clean water and sanitation sector. Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12073015

Mathew DJ et al (2020) Awareness and practices of sanitary latrine usage and environmental cleanliness in rural Etawah, Uttar Pradesh. J Evol Med Dent Sci 9(18):1490–1493. https://doi.org/10.14260/jemds/2020/325

Mitlin D, Walnycki A (2020) Informality as experimentation: water utilities’ strategies for cost recovery and their consequences for universal access. J Dev Stud 56(2):259–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2019.1577383

Mraz AL et al (2021) Why pathogens matter for meeting the united nations’ sustainable development goal 6 on safely managed water and sanitation. Water Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2020.116591

Mycoo MA (2018) Achieving SDG 6: water resources sustainability in Caribbean Small island developing states through improved water governance. Nat Res Forum 42(1):54–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/1477-8947.12141

Ngobeni V, Breitenbach MC (2021) Production and scale efficiency of South African water utilities: the case of water boards. Water Policy. https://doi.org/10.2166/wp.2021.055

Nhamo G, Nhemachena C, Nhamo S (2019) Is 2030 too soon for Africa to achieve the water and sanitation sustainable development goal? Sci Total Environ 669:129–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.109

Paerli R, Fischer M (2020) Implementing the Agenda 2030-what is the role of forums? Int J Sustain Dev World 27(5):443–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504509.2020.1719546

Pickering AJ et al (2019) Effect of in-line drinking water chlorination at the point of collection on child diarrhoea in urban Bangladesh: a double-blind, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health 7(9):E1247–E1256. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30315-8

Qadir M et al (2018) Fog water collection: challenges beyond technology. Water (switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/w10040372

Quarshie AM et al (2021) Conceptual behaviour underpinning the occurrence of nonfaecal matter in faecal sludge in some urban communities, Ghana. J Environ Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/2672491

Rahaman MM, Galib AI, Azmi F (2021) Achieving drinking water and sanitation related targets of SDG 6 at Shahidbug slum, Dhaka. Water Int. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508060.2021.1901189

Rayasam SDG, Rao B, Ray I (2020) The reality of water quality monitoring for SDG 6: a report from a small town in India. J Water Sanit Hyg Dev 10(3):589–595. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2020.131

Rivett MO et al (2019) Responding to salinity in a rural African alluvial valley aquifer system: to boldly go beyond the world of hand-pumped groundwater supply? Sci Total Environ 653:1005–1024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.10.337

Rivett MO et al (2020) Paleo-geohydrology of Lake chilwa, Malawi is the source of localised groundwater salinity and rural water supply challenges. Appl Sci Basel. https://doi.org/10.3390/app10196909

Romano O, Akhmouch A (2019) Water governance in cities: current trends and future challenges. Water (switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/w11030500

Roy A, Pramanick K (2019) Analysing progress of sustainable development goal 6 in india: past, present, and future. J Environ Manag 232:1049–1065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.11.060

Sachs J et al (2021) Sustainable development report 2021. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009106559

Salmoral G et al (2020) Water-related challenges in nexus governance for sustainable development: insights from the city of Arequipa, Peru. Sci Total Environ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141114

SDG Index. Org (2021) Sustainable development report, sustainable development report. https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/profiles . Accessed 3 Apr 2022

Sogbanmu TO et al (2020) Drinking water quality and human health risk evaluations in rural and urban areas of Ibeju-Lekki and Epe local government areas, Lagos, Nigeria. Hum Ecol Risk Assess 26(4):1062–1075. https://doi.org/10.1080/10807039.2018.1554428

Strokal V (2021) Transboundary rivers of Ukraine: perspectives for sustainable development and clean water. J Integr Environ Sci 18(1):67–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/1943815X.2021.1930058

Swan A et al (2018) Using smart pumps to help deliver universal access to safe and affordable drinking water. Proc Inst Civ Eng Eng Sustain 171(6):277–285. https://doi.org/10.1680/jensu.16.00013

Talan G, Sharma GD (2019) Doing well by doing good: a systematic review and research agenda for sustainable investment. Sustainability (switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/su11020353

Thomas V, Godfrey S (2018) Understanding water-related emotional distress for improving water services: a case study from an Ethiopian small town. J Water Sanit Hyg Dev 8(2):196–207. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2018.167

Torres-Slimming PA et al (2019) Achieving the sustainable development goals: a mixed methods study of health-related water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) for indigenous shawi in the Peruvian Amazon. Int J Environ Res Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16132429

Truslove JP et al (2020) Reflecting SDG 6.1 in rural water supply tariffs: considering ‘affordability’ versus ‘operations and maintenance costs’ in Malawi. Sustainability. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12020744

Udmale P et al (2016) The status of domestic water demand: supply deficit in the Kathmandu Valley, Nepal. Water (switzerland). https://doi.org/10.3390/w8050196

United Nations (2021) UN water, UN water. https://www.sdg6data.org/ . https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals#clean-water-and-sanitation . Accessed 15 July 2021

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2014) International decade for action ‘Water forlLife’ 2005–2015, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. https://www.un.org/waterforlifedecade/scarcity.shtml . Accessed 8 Aug 2021

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (2021) Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal6 . Accessed 8 Aug 2021

United Nations Organisation-Sustainable Development Goals (2021) Water action decade, 2018–2028: averting a global water crisis, United Nations Organisation-Sustainable Development Goals. Available at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/water-action-decade/ . Accessed 8 July 2021

UN-Regional Information Centre for Western Europe (2021) Clean water and sanitation, UN-Regional Information Centre for Western Europe. https://unric.org/en/sdg-6/ . Accessed 8 July 2021

Usman MA, Gerber N, Pangaribowo EH (2018) Drivers of microbiological quality of household drinking water—a case study in rural Ethiopia. J Water Health 16(2):275–288. https://doi.org/10.2166/wh.2017.069

Van Puijenbroek PJTM, Beusen AHW, Bouwman AF (2019) Global nitrogen and phosphorus in urban waste water based on the shared socio-economic pathways. J Environ Manag 231:446–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.10.048

Van Vliet MTH et al (2021) Global water scarcity including surface water quality and expansions of clean water technologies. Environ Res Lett. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abbfc3

Walter CT, Kooy M, Prabaharyaka I (2017) The role of bottled drinking water in achieving SDG 6.1: an analysis of affordability and equity from Jakarta, Indonesia. J Water Sanit Hyg Dev 7(4):642–650. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2017.046

Wight C, Garrick D, Iseman T (2021) Mapping incentives for sustainable water use: global potential, local pathways. Environ Res Commun. https://doi.org/10.1088/2515-7620/abf15c

Wright-Contreras L (2019) A transnational urban political ecology of water infrastructures: global water policies and water management in Hanoi. Public Works Manag Policy 24(2):195–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087724X18780045

Yalew SG, Kwakkel J, Doorn N (2021) Distributive justice and sustainability goals in transboundary rivers: case of the Nile Basin. Front Environ Sci. https://doi.org/10.3389/fenvs.2020.590954

Yesaya M, Tilley E (2021) Sludge bomb: the impending sludge emptying and treatment crisis in Blantyre, Malawi. J Environ Manag. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.111474

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University Centre for Research and Development, Chandigarh University, Gharuan, Mohali, Punjab, 140413, India

Sanjeet Singh

University School of Business, Chandigarh University, Gharuan, Mohali, Punjab, 140413, India

Sanjeet Singh & R. Jayaram

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sanjeet Singh .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Singh, S., Jayaram, R. Attainment of water and sanitation goals: a review and agenda for research. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 8 , 146 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40899-022-00719-9

Download citation

Received : 27 October 2021

Accepted : 03 August 2022

Published : 23 August 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s40899-022-00719-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Sustainable development goals

- Water recycle

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Barriers and facilitators to Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WaSH) practices in Southern Africa: A scoping review

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation School of Nursing and Public Health, College of Health Sciences, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Howard Campus, Durban, South Africa

Roles Data curation, Methodology

Roles Supervision, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Bill and Joyce Cummings Institute of Global Health, University of Global Health Equity (UGHE), Kigali, Rwanda, Institute of Global Health Equity Research (IGHER), University of Global Health Equity (UGHE), Kigali, Rwanda

Affiliation Department of Behavioural Science, Medical and Health Sciences, Great Zimbabwe University, Masvingo, Zimbabwe

- Nkeka P. Tseole,

- Tafadzwa Mindu,

- Chester Kalinda,

- Moses J. Chimbari

- Published: August 2, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0271726

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

A healthy and a dignified life experience requires adequate water, sanitation, and hygiene (WaSH) coverage. However, inadequate WaSH resources remain a significant public health challenge in many communities in Southern Africa. A systematic search of peer-reviewed journal articles from 2010 –May 2022 was undertaken on Medline, PubMed, EbscoHost and Google Scholar from 2010 to May 2022 was searched using combinations of predefined search terms with Boolean operators. Eighteen peer-reviewed articles from Southern Africa satisfied the inclusion criteria for this review. The general themes that emerged for both barriers and facilitators included geographical inequalities, climate change, investment in WaSH resources, low levels of knowledge on water borne-diseases and ineffective local community engagement. Key facilitators to improved WaSH practices included improved WaSH infrastructure, effective local community engagement, increased latrine ownership by individual households and the development of social capital. Water and sanitation are critical to ensuring a healthy lifestyle. However, many people and communities in Southern Africa still lack access to safe water and improved sanitation facilities. Rural areas are the most affected by barriers to improved WaSH facilities due to lack of WaSH infrastructure compared to urban settings. Our review has shown that, the current WaSH conditions in Southern Africa do not equate to the improved WaSH standards described in SDG 6 on ensuring access to water and sanitation for all. Key barriers to improved WaSH practices identified include rurality, climate change, low investments in WaSH infrastructure, inadequate knowledge on water-borne illnesses and lack of community engagement.

Citation: Tseole NP, Mindu T, Kalinda C, Chimbari MJ (2022) Barriers and facilitators to Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WaSH) practices in Southern Africa: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 17(8): e0271726. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0271726

Editor: Balasubramani Ravindran, Kyonggi University, REPUBLIC OF KOREA

Received: September 12, 2021; Accepted: July 6, 2022; Published: August 2, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Tseole et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Global Health Research programme (16/136/33), UK and the University of KwaZulu-Natal. We also acknowledge University Administration Support Program (UASP) funding for this manuscript.

Competing interests: There are no competing interests for this manuscript.

Introduction

Inadequate water, access to improved sanitation, and hygiene (WaSH) are global health challenges affecting about one-third of the world’s population [ 1 , 2 ]. Improved sanitation and hygiene are essential because they reduce environmental health risks [ 3 ]. Global diarrheal disease statistics show that more than one million annual deaths are related to poor WaSH practices as over one-third of the world’s population do not have basic sanitation [ 4 ]. Although adequate WaSH coverage is critical for improving quality of life, globally about 2 billion people do not have access to clean water [ 5 ] and over 263 million people walk long distances to collect water from rivers, streams and lakes. Furthermore, at least 159 million people drink water from unsafe sources [ 5 ].

In Africa, about 70 percent of rural water schemes are non-functional or intermittently functional at any given time [ 6 ] resulting in compromised human wellbeing [ 7 ]. Due to poor WaSH practices in Africa, about 28 percent of the population in the region still practice open defecation [ 1 ]. Unsafe sanitation behaviours are responsible for around 775, 000 world deaths annually of which 5 percent are in low-income countries [ 1 ]. Universal, affordable, and sustainable access to WaSH is one of the key public health and developmental issues. Plans to improve WaSH coverage are instituted in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) goal 6 which seeks to ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all by 2030 [ 8 ]. Even though this SDG advocates for progressive reduction of inequalities related to hygiene and universal access to clean water and sanitation [ 8 ], continued inequalities in access to clean water and improved sanitation between rural and urban settings are still a challenge [ 8 – 11 ].

Improved WaSH practices have the potential to reduce the prevalence of diseases such as schistosomiasis, cholera, diarrhea, polio, and typhoid which are prevalent in most sub-Saharan African countries. However, people still lack adequate information on WaSH leading to poor sanitation and hygiene practices. Southern Africa is among regions with very low rates of WaSH coverage in the world [ 8 ]. The provision of clean water to most rural communities in Southern Africa is insufficient and this exacerbates challenges associated with sanitation and hygiene [ 12 ]. For instance, hand washing is a cost-effective and simple approach used for the control of water-based infections and yet despite its simplicity and effectiveness it is not widely used [ 13 ].