- Pregnancy Classes

Breech Births

In the last weeks of pregnancy, a baby usually moves so his or her head is positioned to come out of the vagina first during birth. This is called a vertex presentation. A breech presentation occurs when the baby’s buttocks, feet, or both are positioned to come out first during birth. This happens in 3–4% of full-term births.

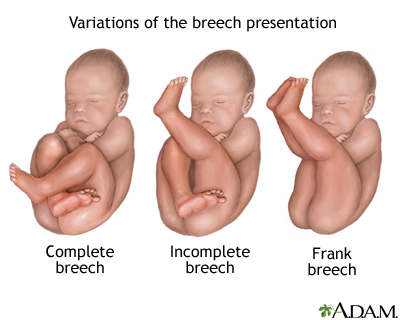

What are the different types of breech birth presentations?

- Complete breech: Here, the buttocks are pointing downward with the legs folded at the knees and feet near the buttocks.

- Frank breech: In this position, the baby’s buttocks are aimed at the birth canal with its legs sticking straight up in front of his or her body and the feet near the head.

- Footling breech: In this position, one or both of the baby’s feet point downward and will deliver before the rest of the body.

What causes a breech presentation?

The causes of breech presentations are not fully understood. However, the data show that breech birth is more common when:

- You have been pregnant before

- In pregnancies of multiples

- When there is a history of premature delivery

- When the uterus has too much or too little amniotic fluid

- When there is an abnormally shaped uterus or a uterus with abnormal growths, such as fibroids

- The placenta covers all or part of the opening of the uterus placenta previa

How is a breech presentation diagnosed?

A few weeks prior to the due date, the health care provider will place her hands on the mother’s lower abdomen to locate the baby’s head, back, and buttocks. If it appears that the baby might be in a breech position, they can use ultrasound or pelvic exam to confirm the position. Special x-rays can also be used to determine the baby’s position and the size of the pelvis to determine if a vaginal delivery of a breech baby can be safely attempted.

Can a breech presentation mean something is wrong?

Even though most breech babies are born healthy, there is a slightly elevated risk for certain problems. Birth defects are slightly more common in breech babies and the defect might be the reason that the baby failed to move into the right position prior to delivery.

Can a breech presentation be changed?

It is preferable to try to turn a breech baby between the 32nd and 37th weeks of pregnancy . The methods of turning a baby will vary and the success rate for each method can also vary. It is best to discuss the options with the health care provider to see which method she recommends.

Medical Techniques

External Cephalic Version (EVC) is a non-surgical technique to move the baby in the uterus. In this procedure, a medication is given to help relax the uterus. There might also be the use of an ultrasound to determine the position of the baby, the location of the placenta and the amount of amniotic fluid in the uterus.

Gentle pushing on the lower abdomen can turn the baby into the head-down position. Throughout the external version the baby’s heartbeat will be closely monitored so that if a problem develops, the health care provider will immediately stop the procedure. ECV usually is done near a delivery room so if a problem occurs, a cesarean delivery can be performed quickly. The external version has a high success rate and can be considered if you have had a previous cesarean delivery.

ECV will not be tried if:

- You are carrying more than one fetus

- There are concerns about the health of the fetus

- You have certain abnormalities of the reproductive system

- The placenta is in the wrong place

- The placenta has come away from the wall of the uterus ( placental abruption )

Complications of EVC include:

- Prelabor rupture of membranes

- Changes in the fetus’s heart rate

- Placental abruption

- Preterm labor

Vaginal delivery versus cesarean for breech birth?

Most health care providers do not believe in attempting a vaginal delivery for a breech position. However, some will delay making a final decision until the woman is in labor. The following conditions are considered necessary in order to attempt a vaginal birth:

- The baby is full-term and in the frank breech presentation

- The baby does not show signs of distress while its heart rate is closely monitored.

- The process of labor is smooth and steady with the cervix widening as the baby descends.

- The health care provider estimates that the baby is not too big or the mother’s pelvis too narrow for the baby to pass safely through the birth canal.

- Anesthesia is available and a cesarean delivery possible on short notice

What are the risks and complications of a vaginal delivery?

In a breech birth, the baby’s head is the last part of its body to emerge making it more difficult to ease it through the birth canal. Sometimes forceps are used to guide the baby’s head out of the birth canal. Another potential problem is cord prolapse . In this situation the umbilical cord is squeezed as the baby moves toward the birth canal, thus slowing the baby’s supply of oxygen and blood. In a vaginal breech delivery, electronic fetal monitoring will be used to monitor the baby’s heartbeat throughout the course of labor. Cesarean delivery may be an option if signs develop that the baby may be in distress.

When is a cesarean delivery used with a breech presentation?

Most health care providers recommend a cesarean delivery for all babies in a breech position, especially babies that are premature. Since premature babies are small and more fragile, and because the head of a premature baby is relatively larger in proportion to its body, the baby is unlikely to stretch the cervix as much as a full-term baby. This means that there might be less room for the head to emerge.

Want to Know More?

- Creating Your Birth Plan

- Labor & Birth Terms to Know

- Cesarean Birth After Care

Compiled using information from the following sources:

- ACOG: If Your Baby is Breech

- William’s Obstetrics Twenty-Second Ed. Cunningham, F. Gary, et al, Ch. 24.

- Danforth’s Obstetrics and Gynecology Ninth Ed. Scott, James R., et al, Ch. 21.

BLOG CATEGORIES

- Can I get pregnant if… ? 3

- Child Adoption 19

- Fertility 54

- Pregnancy Loss 11

- Breastfeeding 29

- Changes In Your Body 5

- Cord Blood 4

- Genetic Disorders & Birth Defects 17

- Health & Nutrition 2

- Is it Safe While Pregnant 54

- Labor and Birth 65

- Multiple Births 10

- Planning and Preparing 24

- Pregnancy Complications 68

- Pregnancy Concerns 62

- Pregnancy Health and Wellness 149

- Pregnancy Products & Tests 8

- Pregnancy Supplements & Medications 14

- The First Year 41

- Week by Week Newsletter 40

- Your Developing Baby 16

- Options for Unplanned Pregnancy 18

- Paternity Tests 2

- Pregnancy Symptoms 5

- Prenatal Testing 16

- The Bumpy Truth Blog 7

- Uncategorized 4

- Abstinence 3

- Birth Control Pills, Patches & Devices 21

- Women's Health 34

- Thank You for Your Donation

- Unplanned Pregnancy

- Getting Pregnant

- Healthy Pregnancy

- Privacy Policy

Share this post:

Similar post.

Episiotomy: Advantages & Complications

Retained Placenta

What is Dilation in Pregnancy?

Track your baby’s development, subscribe to our week-by-week pregnancy newsletter.

- The Bumpy Truth Blog

- Fertility Products Resource Guide

Pregnancy Tools

- Ovulation Calendar

- Baby Names Directory

- Pregnancy Due Date Calculator

- Pregnancy Quiz

Pregnancy Journeys

- Partner With Us

- Corporate Sponsors

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

- Management of breech presentation

Evidence review M

NICE Guideline, No. 201

National Guideline Alliance (UK) .

- Copyright and Permissions

Review question

What is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy?

Introduction

Breech presentation of the fetus in late pregnancy may result in prolonged or obstructed labour with resulting risks to both woman and fetus. Interventions to correct breech presentation (to cephalic) before labour and birth are important for the woman’s and the baby’s health. The aim of this review is to determine the most effective way of managing a breech presentation in late pregnancy.

Summary of the protocol

Please see Table 1 for a summary of the Population, Intervention, Comparison and Outcome (PICO) characteristics of this review.

Summary of the protocol (PICO table).

For further details see the review protocol in appendix A .

Methods and process

This evidence review was developed using the methods and process described in Developing NICE guidelines: the manual 2014 . Methods specific to this review question are described in the review protocol in appendix A .

Declarations of interest were recorded according to NICE’s conflicts of interest policy .

Clinical evidence

Included studies.

Thirty-six randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were identified for this review.

The included studies are summarised in Table 2 .

Three studies reported on external cephalic version (ECV) versus no intervention ( Dafallah 2004 , Hofmeyr 1983 , Rita 2011 ). One study reported on a 4-arm trial comparing acupuncture, sweeping of fetal membranes, acupuncture plus sweeping, and no intervention ( Andersen 2013 ). Two studies reported on postural management versus no intervention ( Chenia 1987 , Smith 1999 ).

Seven studies reported on ECV plus anaesthesia ( Chalifoux 2017 , Dugoff 1999 , Khaw 2015 , Mancuso 2000 , Schorr 1997 , Sullivan 2009 , Weiniger 2010 ). Of these studies, 1 study compared ECV plus anaesthesia to ECV plus other dosages of the same anaesthetic ( Chalifoux 2017 ); 4 studies compared ECV plus anaesthesia to ECV only ( Dugoff 1999 , Mancuso 2000 , Schorr 1997 , Weiniger 2010 ); and 2 studies compared ECV plus anaesthesia to ECV plus a different anaesthetic ( Khaw 2015 , Sullivan 2009 ).

Ten studies reported ECV plus a β2 receptor agonist ( Brocks 1984 , Fernandez 1997 , Hindawi 2005 , Impey 2005 , Mahomed 1991 , Marquette 1996 , Nor Azlin 2005 , Robertson 1987 , Van Dorsten 1981 , Vani 2009 ). Of these studies, 5 studies compared ECV plus a β2 receptor agonist to ECV plus placebo ( Fernandez 1997 , Impey 2005 , Marquette 1996 , Nor Azlin 2005 , Vani 2009 ); 1 study compared ECV plus a β2 receptor agonist to ECV alone ( Robertson 1987 ); and 4 studies compared ECV plus a β2 receptor agonist to no intervention ( Brocks 1984 , Hindawi 2005 , Mahomed 1991 , Van Dorsten 1981 ).

One study reported on ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker versus ECV plus placebo ( Kok 2008 ). Two studies reported on ECV plus β2 receptor agonist versus ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker ( Collaris 2009 , Mohamed Ismail 2008 ). Four studies reported on ECV plus a µ-receptor agonist ( Burgos 2016 , Liu 2016 , Munoz 2014 , Wang 2017 ), of which 3 compared against ECV plus placebo ( Liu 2016 , Munoz 2014 , Wang 2017 ) and 1 compared to ECV plus nitrous oxide ( Burgos 2016 ).

Four studies reported on ECV plus nitroglycerin ( Bujold 2003a , Bujold 2003b , El-Sayed 2004 , Hilton 2009 ), of which 2 compared it to ECV plus β2 receptor agonist ( Bujold 2003b , El-Sayed 2004 ) and compared it to ECV plus placebo ( Bujold 2003a , Hilton 2009 ). One study compared ECV plus amnioinfusion versus ECV alone ( Diguisto 2018 ) and 1 study compared ECV plus talcum powder to ECV plus gel ( Vallikkannu 2014 ).

One study was conducted in Australia ( Smith 1999 ); 4 studies in Canada ( Bujold 2003a , Bujold 2003b , Hilton 2009 , Marquette 1996 ); 2 studies in China ( Liu 2016 , Wang 2017 ); 2 studies in Denmark ( Andersen 2013 , Brocks 1984 ); 1 study in France ( Diguisto 2018 ); 1 study in Hong Kong ( Khaw 2015 ); 1 study in India ( Rita 2011 ); 1 study in Israel ( Weiniger 2010 ); 1 study in Jordan ( Hindawi 2005 ); 5 studies in Malaysia ( Collaris 2009 , Mohamed Ismail 2008 , Nor Azlin 2005 , Vallikkannu 2014 , Vani 2009 ); 1 study in South Africa ( Hofmeyr 1983 ); 2 studies in Spain ( Burgos 2016 , Munoz 2014 ); 1 study in Sudan ( Dafallah 2004 ); 1 study in The Netherlands ( Kok 2008 ); 2 studies in the UK ( Impey 2005 , Chenia 1987 ); 9 studies in US ( Chalifoux 2017 , Dugoff 1999 , El-Sayed 2004 , Fernandez 1997 , Mancuso 2000 , Robertson 1987 , Schorr 1997 , Sullivan 2009 , Van Dorsten 1981 ); and 1 study in Zimbabwe ( Mahomed 1991 ).

The majority of studies were 2-arm trials, but there was one 3-arm trial ( Khaw 2015 ) and two 4-arm trials ( Andersen 2013 , Chalifoux 2017 ). All studies were conducted in a hospital or an outpatient ward connected to a hospital.

See the literature search strategy in appendix B and study selection flow chart in appendix C .

Excluded studies

Studies not included in this review with reasons for their exclusions are provided in appendix K .

Summary of clinical studies included in the evidence review

Summaries of the studies that were included in this review are presented in Table 2 .

Summary of included studies.

See the full evidence tables in appendix D and the forest plots in appendix E .

Quality assessment of clinical outcomes included in the evidence review

See the evidence profiles in appendix F .

Economic evidence

A systematic review of the economic literature was conducted but no economic studies were identified which were applicable to this review question.

A single economic search was undertaken for all topics included in the scope of this guideline. See supplementary material 2 for details.

Economic studies not included in this review are listed, and reasons for their exclusion are provided in appendix K .

Summary of studies included in the economic evidence review

No economic studies were identified which were applicable to this review question.

Economic model

No economic modelling was undertaken for this review because the committee agreed that other topics were higher priorities for economic evaluation.

Evidence statements

Clinical evidence statements, comparison 1. complementary therapy versus control (no intervention), critical outcomes, cephalic presentation in labour.

No evidence was identified to inform this outcome.

Method of birth

Caesarean section.

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=204) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and control (no intervention) on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.74 (95% CI 0.38 to 1.43).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=200) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture plus membrane sweeping and control (no intervention) on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.29 (95% CI 0.73 to 2.29).

Admission to SCBU/NICU

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=204) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and control (no intervention) on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.19 (95% CI 0.02 to 1.62).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=200) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture plus membrane sweeping and control (no intervention) on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.40 (0.08 to 2.01).

Fetal death after 36 +0 weeks gestation

Infant death up to 4 weeks chronological age, important outcomes, apgar score <7 at 5 minutes.

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=204) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and control (no intervention) on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.32 (95% CI 0.01 to 7.78).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=200) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture plus membrane sweeping and control (no intervention) on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.33 (0.01 to 8.09).

Birth before 39 +0 weeks of gestation

Comparison 2. complementary therapy versus other treatment.

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=207) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and membrane sweeping on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.64 (95% CI 0.34 to 1.22).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=204) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and acupuncture plus membrane sweeping on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.57 (95% CI 0.30 to 1.07).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=203) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture plus membrane sweeping and membrane sweeping on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.13 (95% CI 0.66 to 1.94).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=207) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and membrane sweeping on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.33 (95% CI 0.03 to 3.12).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=204) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and acupuncture plus membrane sweeping on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.48 (95% CI 0.04 to 5.22).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=203) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture plus membrane sweeping and membrane sweeping on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.69 (95% CI 0.12 to 4.02).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=207) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and membrane sweeping on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.02 to 0.02).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=204) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture and acupuncture plus membrane sweeping on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.02 to 0.02).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=203) showed that there is no clinically important difference between acupuncture plus membrane sweeping and membrane sweeping on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.02 to 0.02).

Comparison 3. ECV versus no ECV

- Moderate quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=680) showed that there is clinically important difference favouring ECV over no ECV on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.83 (95% CI 1.53 to 2.18).

Cephalic vaginal birth

- Very low quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=740) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV over no ECV on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.67 (95% CI 1.20 to 2.31).

Breech vaginal birth

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=680) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV and no ECV on breech vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.29 (95% CI 0.03 to 2.84).

- Very low quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=740) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV and no ECV on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.52 (95% CI 0.23 to 1.20).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=60) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV and no ECV on admission to SCBU//NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.50 (95% CI 0.14 to 1.82).

- Very low evidence from 3 RCTs (N=740) showed that there is no statistically significant difference between ECV and no ECV on fetal death after 36 +0 weeks gestation in pregnant women with breech presentation: Peto OR 0.29 (95% CI 0.05 to 1.73) p=0.18.

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV and no ECV on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: Peto OR 0.28 (95% CI 0.04 to 1.70).

Comparison 4. ECV + Amnioinfusion versus ECV only

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=109) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus amnioinfusion and ECV alone on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.74 (95% CI 0.74 to 4.12).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=109) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus amnioinfusion and ECV alone on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.95 (95% CI 0.75 to 1.19).

Comparison 5. ECV + Anaesthesia versus ECV only

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=210) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus anaesthesia and ECV alone on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.16 (95% CI 0.56 to 2.41).

- Very low quality evidence from 5 RCTs (N=435) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus anaesthesia and ECV alone on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.16 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.74).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=108) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus anaesthesia and ECV alone on breech vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.33 (95% CI 0.04 to 3.10).

- Very low quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=263) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus anaesthesia and ECV alone on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.76 (95% CI 0.42 to 1.38).

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=69) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus anaesthesia over ECV alone on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: MD −1.80 (95% CI −2.53 to −1.07).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=126) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus anaesthesia and ECV alone on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.03).

Comparison 6. ECV + Anaesthesia versus ECV + Anaesthesia

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.13 (95% CI 0.73 to 1.74).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=119) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 7.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.81 (95% CI 0.53 to 1.23).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 10mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.96 (95% CI 0.61 to 1.50).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=95) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 0.05mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.69 (95% CI 0.37 to 1.28).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=119) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 7.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.81 (95% CI 0.53 to 1.23).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 10mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.96 (95% CI 0.61 to 1.50).

- Very low evidence from 1 RCT (N=119) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 7.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 10mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.19 (95% CI 0.79 to 1.79).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.92 (95% CI 0.68 to 1.24).

- Very low evidence from 1 RCT (N=119) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 7.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.08 (95% CI 0.78 to 1.50).

- Very low evidence from 1 RCT (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 2.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 10mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.94 (95% CI 0.70 to 1.28).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=119) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 7.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.17 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.61).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=120) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 10mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.03 (95% CI 0.77 to 1.37).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=119) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus 7.5mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl and ECV plus 10mg Bupivacaine plus 0.015mg Fentanyl on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.88 (95% CI 0.64 to 1.20).

Comparison 7. ECV + β2 agonist versus Control (no intervention)

- Moderate quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=256) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus β2 agonist over control (no intervention) on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 4.83 (95% CI 3.27 to 7.11).

- Very low quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=265) showed that there no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and control (no intervention) on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 2.03 (95% CI 0.22 to 19.01).

- Very low quality evidence from 4 RCTs (N=513) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus β2 agonist over control (no intervention) on breech vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.38 (95% CI 0.20 to 0.69).

- Low quality evidence from 4 RCTs (N=513) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus β2 agonist over control (no intervention) on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.53 (95% CI 0.41 to 0.67).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=48) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and control (no intervention) on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.08 to 0.08).

- Very low quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=208) showed that there is no statistically significant difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and control (no intervention) on fetal death after 36 +0 weeks gestation in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD −0.01 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.01) p=0.66.

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=208) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and control (no intervention) on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: Peto OR 0.80 (95% CI 0.31 to 2.10).

Comparison 8. ECV + β2 agonist versus ECV only

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=172) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV only on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.32 (95% CI 0.67 to 2.62).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=58) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV only on breech vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.75 (95% CI 0.22 to 2.50).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=172) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV only on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.79 (95% CI 0.27 to 2.28).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=114) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV only on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.00 (95% CI 0.21 to 4.75).

Comparison 9. ECV + β2 agonist versus ECV + Placebo

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=146) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus placebo on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.54 (95% CI 0.24 to 9.76).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=125) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus placebo on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.27 (95% CI 0.41 to 3.89).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=227) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus placebo on breech vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.00 (95% CI 0.33 to 2.97).

- Low quality evidence from 4 RCTs (N=532) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus placebo on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.81 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.92)

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=146) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus placebo on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.78 (95% CI 0.17 to 3.63).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=124) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus placebo on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.03).

Comparison 10. ECV + Ca 2+ channel blocker versus ECV + Placebo

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=310) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus placebo on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.13 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.48).

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=310) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus placebo on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.90 (95% CI 0.73 to 1.12).

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=310) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus placebo on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.11 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.40).

- High quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=310) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus placebo on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: MD −0.20 (95% CI −0.70 to 0.30).

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=310) showed that there is no statistically significant difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus placebo on fetal death after 36 +0 weeks gestation in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.01 to 0.01) p=1.00.

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=310) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus placebo on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: Peto OR 0.52 (95% 0.05 to 5.02).

Comparison 11. ECV + Ca2+ channel blocker versus ECV + β2 agonist

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=90) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus β2 agonist over ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.62 (95% CI 0.39 to 0.98).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=126) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus β2 agonist on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.26 (95% CI 0.55 to 2.89).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=132) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus β2 agonist over ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.42 (95% CI 1.06 to 1.91).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=176) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus β2 agonist on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: Peto OR 0.53 (95% CI 0.05 to 5.22).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=176) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus Ca 2+ channel blocker and ECV plus β2 agonist on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.03).

Comparison 12. ECV + µ-receptor agonist versus ECV only

- High quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=80) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV alone on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.00 (95% CI 0.80 to 1.24).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=80) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV alone on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.00 (95% CI 0.42 to 2.40).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=126) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV alone on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.03).

Comparison 13. ECV + µ-receptor agonist versus ECV + Placebo

Cephalic vaginal birth after successful ecv.

- High quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=98) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus placebo on cephalic vaginal birth after successful ECV in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.00 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.17).

Caesarean section after successful ECV

- Low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=98) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus placebo on caesarean section after successful ECV in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.97 (95% CI 0.33 to 2.84).

Breech vaginal birth after unsuccessful ECV

- High quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=186) showed that there is a clinically important difference favouring ECV plus µ-receptor agonist over ECV plus placebo on breech vaginal birth after unsuccessful ECV in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.10 (95% CI 0.02 to 0.53).

Caesarean section after unsuccessful ECV

- Moderate quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=186) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus placebo on caesarean section after unsuccessful ECV in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.19 (95% CI 1.09 to 1.31).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=137) showed that there is no statistically significant difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus placebo on fetal death after 36 +0 weeks gestation in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.03 to 0.03) p=1.00.

Comparison 14. ECV + µ-receptor agonist versus ECV + Anaesthesia

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=92) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus anaesthesia on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.04 (95% CI 0.84 to 1.29).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=212) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus anaesthesia on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.90 (95% CI 0.61 to 1.34).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=129) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus anaesthesia on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 2.30 (95% CI 0.21 to 24.74).

- Low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=255) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus µ-receptor agonist and ECV plus anaesthesia on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RD 0.00 (95% CI −0.02 to 0.02).

Comparison 15. ECV + Nitric oxide donor versus ECV + Placebo

- Very low quality evidence from 3 RCTs (N=224) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus nitric oxide donor and ECV plus placebo on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.13 (95% CI 0.59 to 2.16).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=99) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus nitric oxide donor and ECV plus placebo on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.78 (95% CI 0.49 to 1.22).

- Low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=125) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus nitric oxide donor and ECV plus placebo on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.83 (95% CI 0.68 to 1.01).

Comparison 16. ECV + Nitric oxide donor versus ECV + β2 agonist

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=74) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus β2 agonist and ECV plus nitric oxide donor on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.56 (95% CI 0.29 to 1.09).

- Very low quality evidence from 2 RCTs (N=97) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus nitric oxide donor and ECV plus β2 agonist on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.98 (95% CI 0.47 to 2.05).

- Very low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=59) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus nitric oxide donor and ECV plus β2 agonist on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.07 (95% CI 0.73 to 1.57).

Comparison 17. ECV + Talcum powder versus ECV + Gel

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=95) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus talcum powder and ECV plus gel on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.02 (95% CI 0.68 to 1.53).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=95) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus talcum powder and ECV plus gel on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.08 (95% CI 0.67 to 1.74).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=95) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus talcum powder and ECV plus gel on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.94 (95% CI 0.67 to 1.33).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=95) showed that there is no clinically important difference between ECV plus talcum powder and ECV plus gel on admission to SCBU/NICU in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.96 (95% CI 0.38 to 10.19).

Comparison 18. Postural management versus No postural management

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=76) showed that there is no clinically important difference between postural management and no postural management on cephalic presentation in labour in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.26 (95% CI 0.70 to 2.30).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=76) showed that there is no clinically important difference between postural management and no postural management on cephalic vaginal birth in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.11 (95% CI 0.59 to 2.07).

Breech vaginal delivery

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=76) showed that there is no clinically important difference between postural management and no postural management on breech vaginal delivery in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.15 (95% CI 0.67 to 1.99).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=76) showed that there is no clinically important difference between postural management and no postural management on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.69 (95% CI 0.31 to 1.52).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=76) showed that there is no clinically important difference between postural management and no postural management on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 0.24 (95% CI 0.03 to 2.03).

Comparison 19. Postural management + ECV versus ECV only

- Moderate quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=100) showed that there is no clinically important difference between postural management plus ECV and ECV only on the number of caesarean sections in pregnant women with breech presentation: RR 1.05 (95% CI 0.80 to 1.38).

- Low quality evidence from 1 RCT (N=100) showed that there is no clinically important difference between postural management plus ECV and ECV only on Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes in pregnant women with breech presentation: Peto OR 0.13 (95% CI 0.00 to 6.55).

Economic evidence statements

No economic evidence was identified which was applicable to this review question.

The committee’s discussion of the evidence

Interpreting the evidence, the outcomes that matter most.

Provision of antenatal care is important for the health and wellbeing of both mother and baby with the aim of avoiding adverse pregnancy outcomes and enhancing maternal satisfaction and wellbeing. Breech presentation in labour may be associated with adverse outcomes for the fetus, which has contributed to an increased likelihood of caesarean birth. The committee therefore agreed that cephalic presentation in labour and method of birth were critical outcomes for the woman, and admission to SCBU/NICU, fetal death after 36 +0 weeks gestation, and infant death up to 4 weeks chronological age were critical outcomes for the baby. Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes and birth before 39 +0 weeks of gestation were important outcomes for the baby.

The quality of the evidence

The quality of the evidence for interventions for managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (that is breech presentation) in late pregnancy ranged from very low to high, with most of the evidence being of a very low or low quality.

This was predominately due to serious overall risk of bias in some outcomes; imprecision around the effect estimate in some outcomes; indirect population in some outcomes; and the presence of serious heterogeneity in some outcomes, which was unresolved by subgroup analysis. The majority of included studies had a small sample size, which contributed to imprecision around the effect estimate.

No evidence was identified to inform the outcomes of infant death up to 4 weeks chronological age and birth before 39 +0 weeks of gestation.

There was no publication bias identified in the evidence. However, the committee noted the influence pharmacological developers may have in these trials as funders, and took this into account in their decision making.

Benefits and harms

The committee discussed that in the case of breech presentation, a discussion with the woman about the different options and their potential benefits, harms and implications is needed to ensure an informed decision. The committee discussed that some women may prefer a breech vaginal birth or choose an elective caesarean birth, and that her preferences should be supported, in line with shared decision making.

The committee discussed that external cephalic version is standard practice for managing breech presentation in uncomplicated singleton pregnancies at or after 36+0 weeks. The committee discussed that there could be variation in the success rates of ECV based on the experience of the healthcare professional providing the ECV. There was some evidence supporting the use of ECV for managing a breech presentation in late pregnancy. The evidence showed ECV had a clinically important benefit in terms of cephalic presentations in labour and cephalic vaginal deliveries, when compared to no intervention. The committee noted that the evidence suggested that ECV was not harmful to the baby, although the effect estimate was imprecise relating to the relative rarity of the fetal death as an outcome.

Cephalic (head-down) vaginal birth is preferred by many women and the evidence suggests that external cephalic version is an effective way to achieve this. The evidence suggested ECV increased the chance for a cephalic vaginal birth and the committee agreed that it was important to explain this to the woman during her consultation.

The committee discussed the optimum timing for ECV. Timing of ECV must take into account the likelihood of the baby turning naturally before a woman commences labour and the possibility of the baby turning back to a breech presentation after ECV if it is done too early. The committee noted that in their experience, current practice was to perform ECV at 37 gestational weeks. The majority of the evidence demonstrating a benefit of ECV in this review involved ECV performed around 37 gestational weeks, although the review did not look for studies directly comparing different timings of ECV and their relative success rates.

The evidence in this review excluded women with previous complicated pregnancies, such as those with previous caesarean section or uterine surgery. The committee discussed that a previous caesarean section indicates a complicated pregnancy and that this population of women are not the focus of this guideline, which concentrates on women with uncomplicated pregnancies.

The committee’s recommendations align with other NICE guidance and cross references to the NICE guideline on caesarean birth and the section on breech presenting in labour in the NICE guideline on intrapartum care for women with existing medical conditions or obstetric complications and their babies were made.

ECV combined with pharmacological agents

There were some small studies comparing a variety of pharmacological agents (including β2 agonists, Ca 2+ channel blockers, µ-receptor agonists and nitric oxide donors) given alongside ECV. Overall the evidence typically showed no clinically important benefit of adding any pharmacological agent to ECV except in comparisons with a control arm with no ECV where it was not possible to isolate the effect of the ECV versus the pharmacological agent. The evidence tended toward benefit most for β2 agonists and µ-receptor agonists however there was no consistent or high quality evidence of benefit even for these agents. The committee agreed that although these pharmacological agents are used in practice, there was insufficient evidence to make a recommendation supporting or refuting their use or on which pharmacological agent should be used.

The committee discussed that the evidence suggesting µ-receptor agonist, remifentanil, had a clinically important benefit in terms reducing breech vaginal births after unsuccessful ECV was biologically implausible. The committee noted that this pharmacological agent has strong sedative effects, depending on the dosage, and therefore studies comparing it to a placebo had possible design flaws as it would be obvious to all parties whether placebo or active drug had been received. The committee discussed that the risks associated with using remifentanil such as respiratory depression, likely outweigh any potential added benefit it may have on managing breech presentation.

There was some evidence comparing different anaesthetics together with ECV. Although there was little consistent evidence of benefit overall, one small study of low quality showed a combination of 2% lidocaine and epinephrine via epidural catheter (anaesthesia) with ECV showed a clinically important benefit in terms of cephalic presentations in labour and the method of birth. The committee discussed the evidence and agreed the use of anaesthesia via epidural catheter during ECV was uncommon practice in the UK and could be expensive, overall they agreed the strength of the evidence available was insufficient to support a change in practice.

Postural management

There was limited evidence on postural management as an intervention for managing breech presentation in late pregnancy, which showed no difference in effectiveness. Postural management was defined as ‘knee-chest position for 15 minutes, 3 times a day’. The committee agreed that in their experience women valued trying interventions at home first which might make postural management an attractive option for some women, however, there was no evidence that postural management was beneficial. The committee also noted that in their experience postural management can cause notable discomfort so it is not an intervention without disadvantages.

Cost effectiveness and resource use

A systematic review of the economic literature was conducted but no relevant studies were identified which were applicable to this review question.

The committee’s recommendations to offer external cephalic version reinforces current practice. The committee noted that, compared to no intervention, external cephalic version results in clinically important benefits and that there would also be overall downstream cost savings from lower adverse events. It was therefore the committee’s view that offering external cephalic version is cost effective and would not entail any resource impact.

Andersen 2013

Brocks 1984

Bujold 2003

Burgos 2016

Chalifoux 2017

Chenia 1987

Collaris 2009

Dafallah 2004

Diguisto 2018

Dugoff 1999

El-Sayed 2004

Fernandez 1997

Hindawi 2005

Hilton 2009

Hofmeyr 1983

Mahomed 1991

Mancuso 2000

Marquette 1996

Mohamed Ismail 2008

NorAzlin 2005

Robertson 1987

Schorr 1997

Sullivan 2009

VanDorsten 1981

Vallikkannu 2014

Weiniger 2010

Appendix A. Review protocols

Review protocol for review question: What is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy? (PDF, 260K)

Appendix B. Literature search strategies

Literature search strategies for review question: What is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy? (PDF, 281K)

Appendix C. Clinical evidence study selection

Clinical study selection for: What is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy? (PDF, 113K)

Appendix D. Clinical evidence tables

Clinical evidence tables for review question: What is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy? (PDF, 1.2M)

Appendix E. Forest plots

Forest plots for review question: What is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy? (PDF, 678K)

Appendix F. GRADE tables

GRADE tables for review question: What is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy? (PDF, 1.0M)

Appendix G. Economic evidence study selection

Economic evidence study selection for review question: what is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy, appendix h. economic evidence tables, economic evidence tables for review question: what is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy, appendix i. economic evidence profiles, economic evidence profiles for review question: what is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy, appendix j. economic analysis, economic evidence analysis for review question: what is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy.

No economic analysis was conducted for this review question.

Appendix K. Excluded studies

Excluded clinical and economic studies for review question: what is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy, clinical studies, table 24 excluded studies.

View in own window

Economic studies

No economic evidence was identified for this review.

Appendix L. Research recommendations

Research recommendations for review question: what is the most effective way of managing a longitudinal lie fetal malpresentation (breech presentation) in late pregnancy.

No research recommendations were made for this review question.

Evidence reviews underpinning recommendation 1.2.38

These evidence reviews were developed by the National Guideline Alliance, which is a part of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists

Disclaimer : The recommendations in this guideline represent the view of NICE, arrived at after careful consideration of the evidence available. When exercising their judgement, professionals are expected to take this guideline fully into account, alongside the individual needs, preferences and values of their patients or service users. The recommendations in this guideline are not mandatory and the guideline does not override the responsibility of healthcare professionals to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual patient, in consultation with the patient and/or their carer or guardian.

Local commissioners and/or providers have a responsibility to enable the guideline to be applied when individual health professionals and their patients or service users wish to use it. They should do so in the context of local and national priorities for funding and developing services, and in light of their duties to have due regard to the need to eliminate unlawful discrimination, to advance equality of opportunity and to reduce health inequalities. Nothing in this guideline should be interpreted in a way that would be inconsistent with compliance with those duties.

NICE guidelines cover health and care in England. Decisions on how they apply in other UK countries are made by ministers in the Welsh Government , Scottish Government , and Northern Ireland Executive . All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn.

- Cite this Page National Guideline Alliance (UK). Management of breech presentation: Antenatal care: Evidence review M. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); 2021 Aug. (NICE Guideline, No. 201.)

- PDF version of this title (2.2M)

In this Page

Other titles in this collection.

- NICE Evidence Reviews Collection

Related NICE guidance and evidence

- NICE Guideline 201: Antenatal care

Supplemental NICE documents

- Supplement 1: Methods (PDF)

- Supplement 2: Health economics (PDF)

Related information

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Similar articles in PubMed

- Review Identification of breech presentation: Antenatal care: Evidence review L [ 2021] Review Identification of breech presentation: Antenatal care: Evidence review L National Guideline Alliance (UK). 2021 Aug

- Vaginal delivery of breech presentation. [J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009] Vaginal delivery of breech presentation. Kotaska A, Menticoglou S, Gagnon R, MATERNAL FETAL MEDICINE COMMITTEE. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009 Jun; 31(6):557-566.

- Review Cephalic version by moxibustion for breech presentation. [Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005] Review Cephalic version by moxibustion for breech presentation. Coyle ME, Smith CA, Peat B. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Apr 18; (2):CD003928. Epub 2005 Apr 18.

- [Fetal expulsion: Which interventions for perineal prevention? CNGOF Perineal Prevention and Protection in Obstetrics Guidelines]. [Gynecol Obstet Fertil Senol. 2...] [Fetal expulsion: Which interventions for perineal prevention? CNGOF Perineal Prevention and Protection in Obstetrics Guidelines]. Riethmuller D, Ramanah R, Mottet N. Gynecol Obstet Fertil Senol. 2018 Dec; 46(12):937-947. Epub 2018 Oct 28.

- Foetal weight, presentaion and the progress of labour. II. Breech and occipito-posterior presentation related to the baby's weight and the length of the first stage of labour. [J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1961] Foetal weight, presentaion and the progress of labour. II. Breech and occipito-posterior presentation related to the baby's weight and the length of the first stage of labour. BAINBRIDGE MN, NIXON WC, SMYTH CN. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Emp. 1961 Oct; 68:748-54.

Recent Activity

- Management of breech presentation Management of breech presentation

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

Breech Presentation and Delivery

- First Online: 06 August 2021

Cite this chapter

- Uche A. Menakaya 5 , 6

1261 Accesses

Breech presentation refers to the presence of the fetal buttocks, knees or feet at the lower pole of the gravid uterus during pregnancy. At term, up to 4% of pregnancies are breech. The term breech foetus faces peculiar challenges in resource restricted countries with its lack of consensus on management and limited investments in health care systems and training of health care providers. This chapter describes the different types of breech presentation, the risk factors for term breech presentation and the antenatal management options including external cephalic version available to women presenting with a term breech foetus. The chapter also describes the techniques for performing external cephalic version and the maneuvers critical for a successful vaginal breech delivery and highlights the limitations of the evidence for and against vaginal breech delivery in the sub-Saharan continent.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Hofmeyr GJ, Lockwood CJ, Barss VA. Overview of issues related to breech presentation: Uptodate Topic 6776 Version 24.0.

Google Scholar

Scheer K, Nubar J. Variation of fetal presentation with gestational age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;125(2):269–70.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hickok DE, Gordon DC, Milberg JA, Williams MA, Daling JR. The frequency of breech presentation by gestational age at birth: a large population-based study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166(3):851–2.

Albrechtsen S, Rasmussen S, Dalaker K, Irgens LM. Reproductive career after breech presentation: subsequent pregnancy rates, inter pregnancy interval, and recurrence. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92(3):345.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ford JB, Roberts CL, Nassar N, Giles W, Morris JM. Recurrence of breech presentation in consecutive pregnancies. BJOG. 2010;117(7):830.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Nordtveit TI, Melve KK, Albrechtsen S, Skjaerven R. Maternal and paternal contribution to intergenerational recurrence of breech delivery: population based cohort study. BMJ. 2008;336(7649):872.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hofmeyr GJ. Abnormal fetal presentation and position. In: Chapter 34, Turnbull's obstetrics; 2000.

Thorp JM Jr, Jenkins T, Watson W. Utility of Leopold maneuvers in screening for malpresentation. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78(3 Pt 1):394.

PubMed Google Scholar

Grootscholten K, Kok M, Oei SG, Mol BW, van der Post JA. External cephalic version-related risks: a meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;112(5):1143.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R, West HM. External cephalic version for breech presentation at term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Apr;4:CD000083.

De Hundt M, Velzel J, de Groot CJ, Mol BW, Kok M. Mode of delivery after successful external cephalic version: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(6):1327.

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Tan JM, Macario A, Carvalho B, Druzin ML, El-Sayed YY. Cost-effectiveness of external cephalic version for term breech presentation. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10:3.

Gifford DS, Keeler E, Kahn KL. Reductions in cost and caesarean rate by routine use of external cephalic version: a decision analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85(6):930–6.

Ben-Meir A, Erez Y, Sela HY, Shveiky D, Tsafrir A, Ezra Y. Prognostic parameters for successful external cephalic version. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21(9):660.

Kok M, Cnossen J, Gravendeel L, van der Post J, Opmeer B, Mol BW. Clinical factors to predict the outcome of external cephalic version: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(6):630.e1.

Article Google Scholar

Ebner F, Friedl TW, Leinert E, Schramm A, Reister F, Lato K, Janni W, De Gregorio N. Predictors for a successful external cephalic version: a single centre experience. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2016;293(4):749.

Buhimschi CS, Buhimschi IA, Wehrum MJ, Molaskey-Jones S, Sfakianaki AK, Pettker CM, Thung S, Campbell KH, Dulay AT, Funai EF, Bahtiyar MO. Ultrasonographic evaluation of myometrial thickness and prediction of a successful external cephalic version. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118(4):913–20.

Fortunato SJ, Mercer LJ, Guzick DS. External cephalic version with tocolysis: factors associated with success. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72(1):59.

Boucher M, Bujold E, Marquette GP, Vezina Y. The relationship between amniotic fluid index and successful external cephalic version: a 14-year experience. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(3):751.

Hofmeyr GJ, Sadan O, Myer IG, Galal KC, Simko G. External cephalic version and spontaneous version rates: ethnic and other determinants. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1986;93(1):13.

Hofmeyr GJ. Effect of external cephalic version in late pregnancy on breech presentation and caesarean section rate: a controlled trial. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1983;90(5):392.

Collins S, Ellaway P, Harrington D, Pandit M, Impey LW. The complications of external cephalic version: results from 805 consecutive attempts. BJOG. 2007;114(5):636.

Holmes WR, Hofmeyr GJ. Management of breech presentation in areas with high prevalence of HIV infection. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2004;87(3):272.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. External cephalic version. Practice Bulletin No. 161. Obstet Gynecol. 2016;127:e54.

Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. External Cephalic Version (ECV) and Reducing the Incidence of Breech Presentation (Green-top Guideline No. 20a). https://www.rcog.org.uk/en/guidelines-researchservices/guidelines/gtg20a/ . Accessed on 12 May 2016.

Ben-Meir A, Elram T, Tsafrir A, Elchalal U, Ezra Y. The incidence of spontaneous version after failed external cephalic version. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196(2):157.e1.

Hutton EK, Hannah ME, Ross SJ, Delisle MF, Carson GD, Windrim R, Ohlsson A, Willan AR, Gafni A, Sylvestre G, Natale R, Barrett Y, Pollard JK, Dunn MS, Turtle P. Early ECV2 Trial Collaborative Group. The Early External Cephalic Version (ECV) 2 Trial: an international multicentre randomised controlled trial of timing of ECV for breech pregnancies. BJOG. 2011;118(5):564.

Hutton EK, Hofmeyr GJ, Dowswell T. External cephalic version for breech presentation before term. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;7:CD000084.

Hutton EK, Kaufman K, Hodnett E, Amankwah K, Hewson SA, McKay D, Szalai JP, Hannah ME. External cephalic version beginning at 34 weeks' gestation versus 37 weeks' gestation: a randomized multicenter trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(1):245.

Nassar N, Roberts CL, Raynes-Greenow CH, Barratt A, Peat B. Decision aid for breech presentation trial collaborators evaluation of a decision aid for women with breech presentation at term: a randomised controlled trial [ISRCTN14570598]. BJOG. 2007;114(3):325.

Cluver C, Gyte GM, Sinclair M, Dowswell T, Hofmeyr GJ. Interventions for helping to turn term breech babies to head first presentation when using external cephalic version. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Feb;2:CD000184.

Rosman AN, Vlemmix F, Fleuren MA, Rijnders ME, Beuckens A, Opmeer BC, Mol BW, van Zwieten MC, Kok M. Patients' and professionals' barriers and facilitators to external cephalic version for breech presentation at term, a qualitative analysis in the Netherlands. Midwifery. 2014;30(3):324.

Hofmeyr GJ. Sonnendecker EW Cardiotocographic changes after external cephalic version. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1983;90(10):914.

Menakaya UA, Trivedi A. Qualitative assessment of women experiences with ECV. Women Birth. 2013;26(1):41–4.

ACOG Committee on Obstetric Practice ACOG Committee Opinion No. 340. Mode of term singleton breech delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108 (1):235.

Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologist (RCOG). The management of breech presentation. London: RCOG; 2006.

Westgren M, Edvall H, Nordström L, Svalenius E, Ranstam J. Spontaneous cephalic version of breech presentation in the last trimester. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1985;92(1):19.

Coyle ME, Smith CA, Peat B. Cephalic version by moxibustion for breech presentation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;5:CD003928.

Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R. Cephalic version by postural management for breech presentation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD000051.

Glezerman M. Five years to the term breech trial: the rise and fall of a randomized controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(1):20.

Menticoglou SM. Why vaginal breech delivery should still be offered. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006;28(5):380.

Hannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, Hodnett ED, Saigal S, Willan AR. Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2000;356(9239):1375.

Vlemmix F, Bergenhenegouwen L, Schaaf JM, Ensing S, Rosman AN, Ravelli AC, Van Der Post JA, Verhoeven A, Visser GH, Mol BW, Kok M. Term breech deliveries in the Netherlands: did the increased caesarean rate affect neonatal outcome? A population-based cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2014;93(9):888.

Whyte H, Hannah ME, Saigal S, Hannah WJ, Hewson S, Amankwah K, Cheng M, Gafni A, Guselle P, Helewa M, Hodnett ED, Hutton E, Kung R, McKay D, Ross S, Willan A, Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Outcomes of children at 2 years after planned cesarean birth versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: The International Randomized Term Breech Trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191(3):864–71.

Adegbola O, Akindele OM. Outcome of term singleton breech deliveries at a University Teaching Hospital in Lagos. Nigeria Niger Postgrad Med J. 2009;16(2):154–7.

Hartnack Tharin JE, Rasmussen S, Krebs L. Consequences of the term breech trial in Denmark. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90(7):767.

Vistad I, Klungsøyr K, Albrechtsen S, Skjeldestad FE. Neonatal outcome of singleton term breech deliveries in Norway from 1991 to 2011. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2015;94(9):997.

Lyons J, Pressey T, Bartholomew S, Liu S, Liston RM, Joseph KS. Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System (Public Health Agency of Canada) Delivery of breech presentation at term gestation in Canada, 2003-2011. Obstet Gynecol. 2015;125(5):1153.

Goffinet F, Carayol M, Foidart JM, Alexander S, Uzan S, Subtil D, Bréart G, PREMODA Study Group. Is planned vaginal delivery for breech presentation at term still an option? Results of an observational prospective survey in France and Belgium. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194(4):1002.

Kotaska A, Menticoglou S, Gagnon R, Farine D, Basso M, Bos H, Delisle MF, Grabowska K, Hudon L, Mundle W, Murphy-Kaulbeck L, Ouellet A, Pressey T, Roggensack A. Maternal Fetal Medicine Committee, Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada. Vaginal delivery of breech presentation. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2009;31 (6):557.

Goffinet F, Blondel B, Breart G. Breech presentation: questions raised by the controlled trial by Hannah et al. on systematic use of caesarean section for breech presentations. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod. 2001;30:187–90.

CAS Google Scholar

Glezerman M. Five years to the term breech trial: the risk and fall of a randomised controlled trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:20–5.

Hauth JC, Cunningham FG. Vaginal breech delivery is still justified. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:1115–6.

Hull AD, Moore TR. Multiple repeat caesareans and the threat of placenta accreta: incidence, diagnosis, management. Clin Perinatol. 2011;38(2):285.

Moore WT, Steptoe PP. The experience of the John Hopkins hospital with breech presentation: an analysis of 1444 cases. South Med J. 1943;36:295.

Piper EB, Bachman C. The prevention of fetal injuries in breech delivery. J Am Med Assoc. 1929;92:217–21.

DeLee JB. Year book of obstetrics and gynaecology. Chicago: Year Book Medical Publishers; 1939.

Azria E, Le Meaux JP, Khoshnood B, Alexander S, Subtil D, Goffinet F. PREMODA Study Group Factors associated with adverse perinatal outcomes for term breech fetuses with planned vaginal delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;207(4):285.e1–9. Epub 2012 Aug 17

Alarab M, Regan C, O'Connell MP, Keane DP, O'Herlihy C, Foley ME. Singleton vaginal breech delivery at term: still a safe option. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103(3):407.

Hofmeyr GJ, Lockwood CJ, Barss VA. Delivery of the fetus in breech presentation. Uptodate.com 2016 Topic 5384 version 18.

De Hundt M, Vlemmix F, Bais JM, Hutton EK, de Groot CJ, Mol BW, Kok M. Risk factors for developmental dysplasia of the hip: a meta-analysis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2012;165(1):8.

Kenfack B, Ateudjieu J, Ymele FF, et al. Does the advice to Assumethe knee-chest position at the 36th to 37th weeks of gestation reduce the incidence of breech presentation at delivery? Clin Mother Child Health. 2012;9:1–5.

Dobbit JS, Foumane P, Tochie JN, Mamoudou F, Mazou N, Temgoua MN, Tankeu R, Aletum V, Mboudou E. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of vaginal breech delivery for singleton term pregnancies in a carefully selected Cameroonian population: a cohort study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e017198.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

JUNIC Specialist Imaging and Women’s Centre, Coombs, ACT, Australia

Uche A. Menakaya

Calvary Public Hospital, Bruce, ACT, Australia

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Uche A. Menakaya .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Centre of Excellence in Reproductive Health Innovation, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Benin, Benin City, Nigeria

Friday Okonofua

College of Health Sciences, Chicago State University, Chicago, IL, USA

Joseph A. Balogun

Roswell Park Cancer Institute, Buffalo, NY, USA

Kunle Odunsi

Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Weil Cornell Medicine, Doha, Qatar

Victor N. Chilaka

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Menakaya, U.A. (2021). Breech Presentation and Delivery. In: Okonofua, F., Balogun, J.A., Odunsi, K., Chilaka, V.N. (eds) Contemporary Obstetrics and Gynecology for Developing Countries . Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75385-6_17

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-75385-6_17

Published : 06 August 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-75384-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-75385-6

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Health Topics

- Drugs & Supplements

- Medical Tests

- Medical Encyclopedia

- About MedlinePlus

- Customer Support

Breech - series—Types of breech presentation

- Go to slide 1 out of 7

- Go to slide 2 out of 7

- Go to slide 3 out of 7

- Go to slide 4 out of 7

- Go to slide 5 out of 7

- Go to slide 6 out of 7

- Go to slide 7 out of 7

There are three types of breech presentation: complete, incomplete, and frank.

Complete breech is when both of the baby's knees are bent and his feet and bottom are closest to the birth canal.

Incomplete breech is when one of the baby's knees is bent and his foot and bottom are closest to the birth canal.

Frank breech is when the baby's legs are folded flat up against his head and his bottom is closest to the birth canal.

There is also footling breech where one or both feet are presenting.

Review Date 11/21/2022

Updated by: LaQuita Martinez, MD, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Emory Johns Creek Hospital, Alpharetta, GA. Also reviewed by David C. Dugdale, MD, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.

Related MedlinePlus Health Topics

- Childbirth Problems

Uptodate Reference Title

Overview of breech presentation.

INTRODUCTION — Breech presentation, which occurs in approximately 3 percent of fetuses at term, describes the fetus whose presenting part is the buttocks and/or feet. Although most breech fetuses have normal anatomy, this presentation is associated with an increased risk for congenital malformations and mild deformations, torticollis, and developmental dysplasia of the hip. Pregnant people with fetuses in breech presentation at or near term are usually offered external cephalic version (ECV) because a persistent breech presentation is often delivered by planned cesarean, which is associated with a clinically significant decrease in perinatal/neonatal mortality and neonatal morbidity compared with vaginal birth.

This topic will provide an overview of major issues related to breech presentation, including choosing the best route for delivery. Techniques for breech delivery, with a focus on the technique for vaginal breech delivery, are discussed separately. (See "Delivery of the singleton fetus in breech presentation" .)

TYPES OF BREECH PRESENTATION — The main types of breech presentation are:

● Frank breech – Both hips are flexed and both knees are extended so that the feet are adjacent to the head ( figure 1 ); accounts for 50 to 70 percent of breech fetuses at term.

● Complete breech – Both hips and both knees are flexed ( figure 2 ); accounts for 5 to 10 percent of breech fetuses at term.

● Incomplete breech – One or both hips are not completely flexed ( figure 3 ); accounts for 10 to 40 percent of breech fetuses at term.