An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Trending Articles

- Association between pretreatment emotional distress and immune checkpoint inhibitor response in non-small-cell lung cancer. Zeng Y, et al. Nat Med. 2024. PMID: 38740994

- Characteristics, treatment, and outcomes of early vs. late enrollees of the STRONG-HF trial. Arrigo M, et al. Am Heart J. 2024. PMID: 38740532

- An age-progressive platelet differentiation path from hematopoietic stem cells causes exacerbated thrombosis. Poscablo DM, et al. Cell. 2024. PMID: 38749423

- A Direct Link Implicating Loss of SLC26A6 to Gut Microbial Dysbiosis, Compromised Barrier Integrity and Inflammation. Anbazhagan AN, et al. Gastroenterology. 2024. PMID: 38735402

- Andexanet for Factor Xa Inhibitor-Associated Acute Intracerebral Hemorrhage. Connolly SJ, et al. N Engl J Med. 2024. PMID: 38749032 Clinical Trial.

Latest Literature

- Arch Phys Med Rehabil (1)

- Gastroenterology (2)

- J Am Coll Cardiol (2)

- J Biol Chem (1)

- J Neurosci (2)

- Nat Commun (54)

- Neuron (10)

NCBI Literature Resources

MeSH PMC Bookshelf Disclaimer

The PubMed wordmark and PubMed logo are registered trademarks of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Unauthorized use of these marks is strictly prohibited.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

MEDLINE is the National Library of Medicine's (NLM) premier bibliographic database that contains references to journal articles in life sciences, with a concentration on biomedicine. See the MEDLINE Overview page for more information about MEDLINE.

MEDLINE content is searchable via PubMed and constitutes the primary component of PubMed, a literature database developed and maintained by the NLM National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

Last Reviewed: February 5, 2024

When you choose to publish with PLOS, your research makes an impact. Make your work accessible to all, without restrictions, and accelerate scientific discovery with options like preprints and published peer review that make your work more Open.

- PLOS Biology

- PLOS Climate

- PLOS Complex Systems

- PLOS Computational Biology

- PLOS Digital Health

- PLOS Genetics

- PLOS Global Public Health

- PLOS Medicine

- PLOS Mental Health

- PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases

- PLOS Pathogens

- PLOS Sustainability and Transformation

- PLOS Collections

Breaking boundaries. Empowering researchers. Opening Science.

PLOS is a nonprofit, Open Access publisher empowering researchers to accelerate progress in science and medicine by leading a transformation in research communication.

Every country. Every career stage. Every area of science. Hundreds of thousands of researchers choose PLOS to share and discuss their work. Together, we collaborate to make science, and the process of publishing science, fair, equitable, and accessible for the whole community.

FEATURED COMMUNITIES

- Molecular Biology

- Microbiology

- Neuroscience

- Cancer Treatment and Research

RECENT ANNOUNCEMENTS

Written by Lindsay Morton Over 4 years: 74k+ eligible articles. Nearly 85k signed reviews. More than 30k published peer review history…

The latest quarterly update to the Open Science Indicators (OSIs) dataset was released in December, marking the one year anniversary of OSIs…

PLOS JOURNALS

PLOS publishes a suite of influential Open Access journals across all areas of science and medicine. Rigorously reported, peer reviewed and immediately available without restrictions, promoting the widest readership and impact possible. We encourage you to consider the scope of each journal before submission, as journals are editorially independent and specialized in their publication criteria and breadth of content.

PLOS Biology PLOS Climate PLOS Computational Biology PLOS Digital Health PLOS Genetics PLOS Global Public Health PLOS Medicine PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases PLOS ONE PLOS Pathogens PLOS Sustainability and Transformation PLOS Water

Now open for submissions:

PLOS Complex Systems PLOS Mental Health

ADVANCING OPEN SCIENCE

Open opportunities for your community to see, cite, share, and build on your research. PLOS gives you more control over how and when your work becomes available.

Ready, set, share your preprint. Authors of most PLOS journals can now opt-in at submission to have PLOS post their manuscript as a preprint to bioRxiv or medRxiv.

All PLOS journals offer authors the opportunity to increase the transparency of the evaluation process by publishing their peer review history.

We have everything you need to amplify your reviews, increase the visibility of your work through PLOS, and join the movement to advance Open Science.

FEATURED RESOURCES

Ready to submit your manuscript to PLOS? Find everything you need to choose the journal that’s right for you as well as information about publication fees, metrics, and other FAQs here.

We have everything you need to write your first review, increase the visibility of your work through PLOS, and join the movement to advance Open Science.

Transform your research with PLOS. Submit your manuscript

Navigation group

Home banner.

Where scientists empower society

Creating solutions for healthy lives on a healthy planet.

most-cited publisher

largest publisher

2.5 billion

article views and downloads

Main Content

- Editors and reviewers

- Collaborators

Find a journal

We have a home for your research. Our community led journals cover more than 1,500 academic disciplines and are some of the largest and most cited in their fields.

Submit your research

Start your submission and get more impact for your research by publishing with us.

Author guidelines

Ready to publish? Check our author guidelines for everything you need to know about submitting, from choosing a journal and section to preparing your manuscript.

Peer review

Our efficient collaborative peer review means you’ll get a decision on your manuscript in an average of 61 days.

Article publishing charges (APCs) apply to articles that are accepted for publication by our external and independent editorial boards

Press office

Visit our press office for key media contact information, as well as Frontiers’ media kit, including our embargo policy, logos, key facts, leadership bios, and imagery.

Institutional partnerships

Join more than 555 institutions around the world already benefiting from an institutional membership with Frontiers, including CERN, Max Planck Society, and the University of Oxford.

Publishing partnerships

Partner with Frontiers and make your society’s transition to open access a reality with our custom-built platform and publishing expertise.

Policy Labs

Connecting experts from business, science, and policy to strengthen the dialogue between scientific research and informed policymaking.

How we publish

All Frontiers journals are community-run and fully open access, so every research article we publish is immediately and permanently free to read.

Editor guidelines

Reviewing a manuscript? See our guidelines for everything you need to know about our peer review process.

Become an editor

Apply to join an editorial board and collaborate with an international team of carefully selected independent researchers.

My assignments

It’s easy to find and track your editorial assignments with our platform, 'My Frontiers' – saving you time to spend on your own research.

Experts call for global genetic warning system to combat the next pandemic and antimicrobial resistance

Scientists champion global genomic surveillance using latest technologies and a “One Health” approach to protect against novel pathogens like avian influenza and antimicrobial resistance, catching epidemics before they start.

Safeguarding peer review to ensure quality at scale

Making scientific research open has never been more important. But for research to be trusted, it must be of the highest quality. Facing an industry-wide rise in fraudulent science, Frontiers has increased its focus on safeguarding quality.

Scientists call for urgent action to prevent immune-mediated illnesses caused by climate change and biodiversity loss

Climate change, pollution, and collapsing biodiversity are damaging our immune systems, but improving the environment offers effective and fast-acting protection.

Baby sharks prefer being closer to shore, show scientists

marine scientists have shown for the first time that juvenile great white sharks select warm and shallow waters to aggregate within one kilometer from the shore.

Puzzling link between depression and cardiovascular disease explained at last

It’s long been known that depression and cardiovascular disease are somehow related, though exactly how remained a puzzle. Now, researchers have identified a ‘gene module’ which is part of the developmental program of both diseases.

Air pollution could increase the risk of neurological disorders: Here are five Frontiers articles you won’t want to miss this Earth Day

At Frontiers, we bring some of the world’s best research to a global audience. But with tens of thousands of articles published each year, it’s impossible to cover all of them. Here are just five amazing papers you may have missed.

Opening health for all: 7 Research Topics shaping a healthier world

We have picked 7 Research Topics that tackle some of the world's toughest healthcare challenges. These topics champion everyone's access to healthcare, life-limiting illness as a public health challenge, and the ethical challenges in digital public health.

Get the latest research updates, subscribe to our newsletter

Reference management. Clean and simple.

The top list of research databases for medicine and healthcare

3. Cochrane Library

4. pubmed central (pmc), 5. uptodate, frequently asked questions about research databases for medicine and healthcare, related articles.

Web of Science and Scopus are interdisciplinary research databases and have a broad scope. For biomedical research, medicine, and healthcare there are a couple of outstanding academic databases that provide true value in your daily research.

Scholarly databases can help you find scientific articles, research papers , conference proceedings, reviews and much more. We have compiled a list of the top 5 research databases with a special focus on healthcare and medicine.

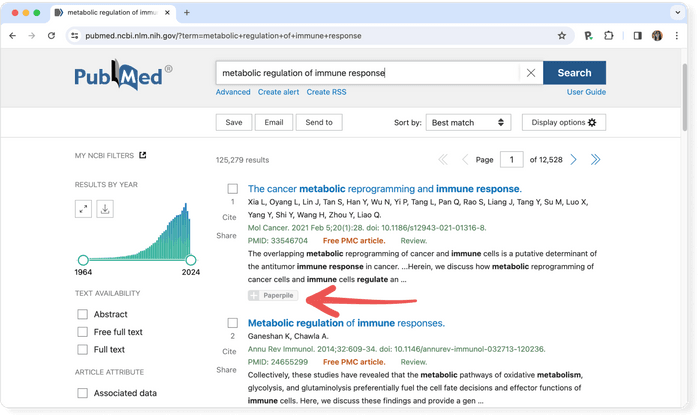

PubMed is the number one source for medical and healthcare research. It is hosted by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and provides bibliographic information including abstracts and links to the full text publisher websites for more than 28 million articles.

- Coverage: around 35 million items

- Abstracts: ✔

- Related articles: ✔

- References: ✘

- Cited by: ✘

- Links to full text: ✔

- Export formats: XML, NBIB

Pro tip: Use a reference manager like Paperpile to keep track of all your sources. Paperpile integrates with PubMed and many popular databases. You can save references and PDFs directly to your library using the Paperpile buttons and later cite them in thousands of citation styles:

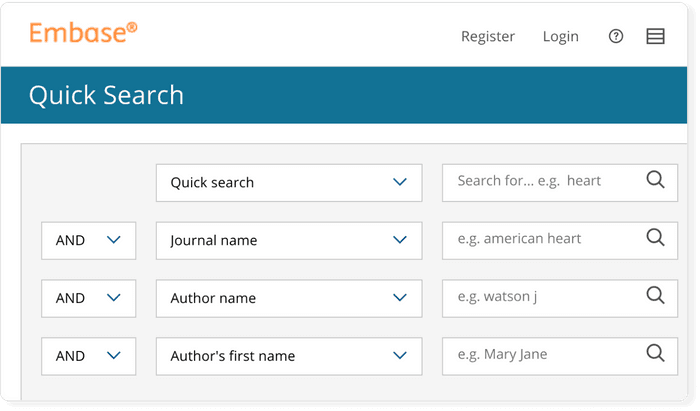

EMBASE (Excerpta Medica Database) is a proprietary research database that also includes PubMed. It can also be accessed by other database providers such as Ovid .

- Coverage: 38 million articles

- References: ✔

- Cited by: ✔

- Full text: ✔ (requires institutional subscription to EMBASE and individual publishers)

- Export formats: RIS

The Cochrane Library is best know for its systematic reviews. There are 53 review groups around the world that ensure that the published reviews are of high-quality and evidence based. Articles are updated over time to reflect new research.

- Coverage: several thousand high quality reviews

- Full text: ✔

- Export formats: RIS, BibTeX

PubMed Central is the free, open access branch of PubMed. It includes full-text versions for all indexed papers. You might also want to check out its sister site Europe PMC .

- Coverage: more than 8 million articles

- Export formats: APA, MLA, AMA, RIS, NBIB

Like the Cochrane Library, UpToDate provides detailed reviews for clinical topics. Reviews are constantly updated to provide an up-to-date view.

- Coverage: several thousand articles from over 420 peer-reviewed journals

- Related articles: ✘

- Full text: ✔ (requires institutional subscription)

- Export formats: ✘

PubMed is the number one source for medical and healthcare research. It is hosted at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and provides bibliographic information including abstracts and links to the full text publisher websites for more than 35 million items.

EMBASE (Excerpta Medica Database) is a proprietary research database that also includes in its corpus PubMed. It can also be accessed by other database providers such as Ovid.

Journal of Medical Internet Research

The leading peer-reviewed journal for digital medicine and health and health care in the internet age. .

Gunther Eysenbach, MD, MPH, FACMI, Founding Editor and Publisher; Adjunct Professor, School of Health Information Science, University of Victoria, Canada

The Journal of Medical Internet Research (JMIR) is the pioneer open access eHealth journal and is the flagship journal of JMIR Publications. It is a leading health services and digital health journal globally in terms of quality/visibility ( Journal Impact Factor™ 7.4 (Clarivate, 2023) ) and is also the largest journal in the field. The journal is ranked #1 on Google Scholar in the 'Medical Informatics' discipline. The journal focuses on emerging technologies, medical devices, apps, engineering, telehealth and informatics applications for patient education, prevention, population health and clinical care.

JMIR is indexed in all major literature indices including National Library of Medicine(NLM)/MEDLINE , Sherpa/Romeo, PubMed, PMC , Scopus , Psycinfo, Clarivate (which includes Web of Science (WoS)/ESCI/SCIE) , EBSCO/EBSCO Essentials, DOAJ , GoOA and others. As a leading high-impact journal in its disciplines, ranking Q1 in both the 'Medical Informatics' and 'Health Care Sciences and Services' categories, it is a selective journal complemented by almost 30 specialty JMIR sister journals , which have a broader scope, and which together receive over 6.000 submissions a year.

As an open access journal, we are read by clinicians, allied health professionals, informal caregivers, and patients alike, and have (as with all JMIR journals) a focus on readable and applied science reporting the design and evaluation of health innovations and emerging technologies. We publish original research, viewpoints, and reviews (both literature reviews and medical device/technology/app reviews). Peer-review reports are portable across JMIR journals and papers can be transferred, so authors save time by not having to resubmit a paper to a different journal but can simply transfer it between journals.

We are also a leader in participatory and open science approaches, and offer the option to publish new submissions immediately as preprints , which receive DOIs for immediate citation (eg, in grant proposals), and for open peer-review purposes. We also invite patients to participate (eg, as peer-reviewers) and have patient representatives on editorial boards.

As all JMIR journals, the journal encourages Open Science principles and strongly encourages publication of a protocol before data collection. Authors who have published a protocol in JMIR Research Protocols get a discount of 20% on the Article Processing Fee when publishing a subsequent results paper in any JMIR journal.

Be a widely cited leader in the digital health revolution and submit your paper today !

Recent Articles

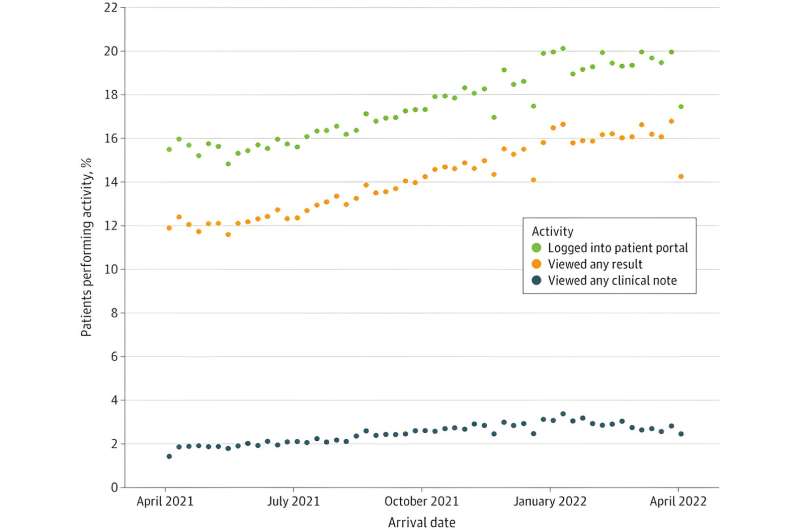

Limiting in-person contact was a key strategy for controlling the spread of the highly infectious novel coronavirus (COVID-19). To protect patients and staff from the risk of infection while providing continued access to necessary health care services, we implemented a new electronic consultation (e-consult) service that allowed referring providers to receive subspecialty consultations for patients who are hospitalized and do not require in-person evaluation by the specialist.

The increased pervasiveness of digital health technology is producing large amounts of person-generated health data (PGHD). These data can empower people to monitor their health to promote prevention and management of disease. Women make up one of the largest groups of consumers of digital self-tracking technology.

Telemedicine offers a multitude of potential advantages, such as enhanced health care accessibility, cost reduction, and improved patient outcomes. The significance of telemedicine has been underscored by the COVID-19 pandemic, as it plays a crucial role in maintaining uninterrupted care while minimizing the risk of viral exposure. However, the adoption and implementation of telemedicine have been relatively sluggish in certain areas. Assessing the level of interest in telemedicine can provide valuable insights into areas that require enhancement.

Digital health and telemedicine are potentially important strategies to decrease health care’s environmental impact and contribution to climate change by reducing transportation-related air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions. However, we currently lack robust national estimates of emissions savings attributable to telemedicine.

The information epidemic emerged along with the COVID-19 pandemic. While controlling the spread of COVID-19, the secondary harm of epidemic rumors to social order cannot be ignored.

Building therapeutic relationships and social presence are challenging in digital services and maybe even more difficult in written services. Despite these difficulties, in-person care may not be feasible or accessible in all situations.

Whether and how the uncertainty about a public health crisis should be communicated to the general public have been important and yet unanswered questions arising over the past few years. As the most threatening contemporary public health crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic has renewed interest in these unresolved issues by both academic scholars and public health practitioners.

No preview text available.

The use of triage systems such as the Manchester Triage System (MTS) is a standard procedure to determine the sequence of treatment in emergency departments (EDs). When using the MTS, time targets for treatment are determined. These are commonly displayed in the ED information system (EDIS) to ED staff. Using measurements as targets has been associated with a decline in meeting those targets.

Artificial intelligence (AI)–based medical devices have garnered attention due to their ability to revolutionize medicine. Their health technology assessment framework is lacking.

Digital twins have emerged as a groundbreaking concept in personalized medicine, offering immense potential to transform health care delivery and improve patient outcomes. It is important to highlight the impact of digital twins on personalized medicine across the understanding of patient health, risk assessment, clinical trials and drug development, and patient monitoring. By mirroring individual health profiles, digital twins offer unparalleled insights into patient-specific conditions, enabling more accurate risk assessments and tailored interventions. However, their application extends beyond clinical benefits, prompting significant ethical debates over data privacy, consent, and potential biases in health care. The rapid evolution of this technology necessitates a careful balancing act between innovation and ethical responsibility. As the field of personalized medicine continues to evolve, digital twins hold tremendous promise in transforming health care delivery and revolutionizing patient care. While challenges exist, the continued development and integration of digital twins hold the potential to revolutionize personalized medicine, ushering in an era of tailored treatments and improved patient well-being. Digital twins can assist in recognizing trends and indicators that might signal the presence of diseases or forecast the likelihood of developing specific medical conditions, along with the progression of such diseases. Nevertheless, the use of human digital twins gives rise to ethical dilemmas related to informed consent, data ownership, and the potential for discrimination based on health profiles. There is a critical need for robust guidelines and regulations to navigate these challenges, ensuring that the pursuit of advanced health care solutions does not compromise patient rights and well-being. This viewpoint aims to ignite a comprehensive dialogue on the responsible integration of digital twins in medicine, advocating for a future where technology serves as a cornerstone for personalized, ethical, and effective patient care.

Large language models showed interpretative reasoning in solving diagnostically challenging medical cases.

Preprints Open for Peer-Review

Open Peer Review Period:

May 16, 2024 - July 11, 2024

May 15, 2024 - July 10, 2024

May 14, 2024 - July 09, 2024

May 09, 2024 - July 04, 2024

May 07, 2024 - July 02, 2024

May 05, 2024 - June 30, 2024

May 03, 2024 - June 28, 2024

May 02, 2024 - June 27, 2024

May 01, 2024 - June 26, 2024

We are working in partnership with

This journal is indexed in

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- BMC Med Inform Decis Mak

Who can you trust? A review of free online sources of “trustworthy” information about treatment effects for patients and the public

Andrew d. oxman.

1 Centre for Informed Health Choices, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, PO Box 4404, Nydalen, N-0403 Oslo, Norway

2 University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Elizabeth J. Paulsen

Associated data.

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and the Additional file 1 .

Information about effects of treatments based on unsystematic reviews of research evidence may be misleading. However, finding trustworthy information about the effects of treatments based on systematic reviews, which is accessible to patients and the public can be difficult. The objectives of this study were to identify and evaluate free sources of health information for patients and the public that provide information about effects of treatments based on systematic reviews.

We reviewed websites that we and our colleagues knew of, searched for government sponsored health information websites, and searched for online sources of health information that provide evidence-based information. To be included in our review, a website had to be available in English, freely accessible, and intended for patients and the public. In addition, it had to have a broad scope, not limited to specific conditions or types of treatments. It had to include a description of how the information is prepared and the description had to include a statement about using systematic reviews. We compared the included websites by searching for information about the effects of eight treatments.

Three websites met our inclusion criteria: Cochrane Evidence , Informed Health , and PubMed Health . The first two websites produce content, whereas PubMed Health aggregated content. A fourth website that met our inclusion criteria, CureFacts , was under development. Cochrane Evidence provides plain language summaries of Cochrane Reviews (i.e. summaries that are intended for patients and the public). They are translated to several other languages. No information besides treatment effects is provided. Informed Health provides information about treatment effects together with other information for a wide range of topics. PubMed Health was discontinued in October 2018. It included a large number of systematic reviews of treatment effects with plain language summaries for Cochrane Reviews and some other reviews. None of the three websites included links to ongoing trials, and information about treatment effects was not reported consistently on any of the websites.

It is possible for patients and the public to access trustworthy information about the effects of treatments using the two of the websites included in this review.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s12911-019-0772-5) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Patients and the public must make choices among different treatment options. We define “treatment” broadly, as any preventive, therapeutic, rehabilitative, or palliative action intended to improve the health or wellbeing of individuals or communities [ 1 ]. This includes, for example, drugs, surgery and other types of “modern medicine”; lifestyle changes, such as changes to what you eat or how you exercise; herbal remedies and other types of “traditional” or “alternative medicine”, and public health interventions. Few people would prefer that decisions about what they should and should not do for their health should be uninformed. Yet, if a decision is going to be well informed rather than misinformed, they need information that is relevant, trustworthy, and accessible. They also need to be able to distinguish between claims about the effects of treatments that are trustworthy and those that are not [ 2 ].

Often the problem is too much information rather than too little. For example, a Google search for “back pain” yields over 60 million hits [ 3 ]. PubMed, a free search engine for accessing MEDLINE and other databases maintained by the United States National Library of Medicine, includes over 27 million citations [ 4 ], and this represents only a fraction of the biomedical literature. The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, a bibliographic database that is restricted to controlled trials of treatments, contains over a million citations [ 5 ]. It is not practical for people making decisions about treatments to use search engines or databases such as these to find relevant information, critically appraise the studies they find, synthesize them, and interpret the results.

Systematic reviews reduce the risk of being misled by bias (systematic errors) and the play of chance (random errors), by using systematic and explicit methods to identify, select, and critically appraise relevant studies, and to collect and analyse data from them [ 6 ]. For information about treatment effects to be trustworthy, it should be based on systematic reviews. For it to be accessible to patients and the public, it should be easy to find and should be clearly communicated in plain language [ 7 ].

Unfortunately, a large amount of information about treatment effects is not based on systematic reviews and is not trustworthy [ 8 – 19 ]. This includes handouts for patients [ 8 , 9 ], internet-based information [ 10 , 11 ], information in social and mass media [ 12 – 18 ], information produced by patient organisations [ 8 , 9 , 12 ]. press releases [ 18 ], and advertisements [ 19 ]. Studies of the trustworthiness of health information have used a variety of criteria, but have consistently found important limitations [ 8 – 19 ]. Although trustworthy information about treatment effects can be found, evidence-based information is frequently written for health professionals or researchers, rather than for patients and the public [ 7 ].

There is an abundance of health information on the internet, which has become an important source of health information over the past two decades [ 10 , 11 , 20 – 24 ], but patients and the public find it difficult to search the internet for trustworthy information [ 21 – 23 ], and are unlikely to critically appraise the information that they do find [ 22 , 23 ].

There are a number of websites that aim to improve access to trustworthy health information for patients and the public. The objectives of this study were to identify free sources of health information for patients and the public which provide information about the effects of treatments based on systematic reviews, and to evaluate those websites.

Our motivation for undertaking this review grew out of a desire to respond to people who were looking for trustworthy information about the effects of specific treatments and landed on Testing Treatments international [ 25 ], a website for promoting critical thinking about treatment claims. Rather than simply noting that the Testing Treatments website does not provide the information they were seeking, we wanted to help them by directing them to sources that do provide this information. Given this motivation, we restricted our review of websites to ones with a broad scope. There were two reasons for this. First, websites with a broad scope can meet the needs of most people seeking trustworthy information about treatment effects. Furthermore, although disease-specific websites can be useful, it would be impractical to assess any more than a small sample of websites for specific conditions or types of treatments. Second, it is easier to become familiar with one or a small number of websites than it is to use multiple websites for questions about different conditions or types of treatments.

We considered any website that defined itself as providing “health information”, which included information about treatments. To be included in this review a website needed to be:

- Available in English

- Freely accessible (i.e. non-commercial with no cost to users or membership fees)

- That described itself as being intended for patients and the public

- Broad in scope (not limited to specific conditions or types of treatments)

- Explicitly based on systematic reviews (i.e. there had to be a description of how the information is prepared and the description had to include a statement about using systematic reviews)

We identified websites that potentially met those criteria by considering websites that we and our colleagues (see Acknowledgements) knew of. The first author (AO) searched for government sponsored websites in English speaking countries (including Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, the UK, and the USA); searched Google for “health information” and “patient information” to identify websites that are frequently accessed for health information; and checked links to other websites on the websites that were identified. On 29 January 2018, AO conducted a final set of searches using the following terms: “health information”, “patient information”, “evidence-based health information”, and “evidence-based patient information”; and these search engines: Google [ 3 ], Bing [ 26 ], DuckDuckGo [ 27 ], and HONsearch patients [ 28 ]. Google and Bing are the two most popular search engines, DuckDuckGo is not affected by your previous search history, and HONsearch searches “trustworthy” health websites. The first 20 hits for each search were screened, and any websites that looked like they might meet our inclusion criteria were checked.

AO assessed each identified website for inclusion and the second author (EP) checked those judgements using information provided on the websites. In addition, we emailed each excluded website to confirm that our reason for excluding it was correct.

AO collected the following information for each included website:

- The stated purpose

- A statement that information about treatment effects is based on systematic reviews

- Availability of links to the systematic reviews

- Reporting size of effects

- Reporting certainty of the evidence; i.e. a judgement using GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) [ 29 – 31 ] or another formal approach or an informal judgement about how sure we can be about the reported effects

- Availability of links to ongoing trials

- Information about how up-to-date information about treatment effects is

- What other information is provided

- What tools there are for searching, sorting, and filtering information

- Use of plain language (i.e. summaries written for patients and the public) and the availability of a glossary

EP checked all of the information that was recorded and the judgements that were made. To inform these judgements, both authors independently searched each included website for eight questions about treatments to assess the ease of finding information (AO on 22 December 2017 and EP on 9 January 2018). We selected the eight questions by searching Google for “common health questions” and selecting the first relevant list that we found ( 25 Questions About Your Health Answered - Oprah.com ). Many of the questions in that list were not about treatment effects and we modified some of the questions with the intention of having a variety of questions for different types of conditions and treatments. Table 1 shows the original question from that list, our question, the conditions, the treatments, and the initial search terms that we used to find information about treatment effects on each website.

Questions about treatments used to assess the included websites

We then independently assessed what was reported about treatment effects, the consistency of reporting, and the advantages and disadvantages of each website. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Based on these assessments and the information we had collected for each website we suggested how the websites could be improved and provided tips for website users.

For each question, we searched for information using plain language terms without Boolean logic (using the first terms shown for each question in the last column of Table Table1). 1 ). We recorded the number of hits for each search and each relevant summary that we found. We assessed the search as easy if we found relevant information using plain language terms without Boolean logic and the relevant information was one of the first few hits. We assessed searches as hard if we had to use technical terms or Boolean logic, or if we could not find relevant information; and as moderate if finding relevant information required some minor fiddling with the search terms or screening more than a few hits.

For each relevant summary that we found, we recorded whether any information was provided about benefits of the treatment and harms of the treatment, whether quantitative information was provided for at least one outcome, and whether a formal or informal assessment of the certainty of the evidence was provided. We then ranked the three websites for each question based on an overall assessment of how hard it was to find relevant information and the completeness of the information about the effects of the treatments.

We considered 35 websites for inclusion. Of these, 26 were excluded because information about treatment effects was not explicitly based on systematic reviews (Table 2 ), five were excluded because they were not intended for patients and the public (Table 3 ), and one was under development (Table 4 ). Three of the 34 websites met our inclusion criteria: Cochrane Evidence , Informed Health , and PubMed Health (Table 5 ). Cochrane Evidence and Informed Health produce content, whereas PubMed Health , which was discontinued in October 2018, aggregated content, including content from the first two websites.

Websites excluded because they are not explicitly based on systematic reviews a

a These websites were excluded because they do not include a description of how information is prepared that includes a statement about using or being based on systematic reviews of research evidence. It is unclear to what extent information about treatment effects on these websites is based on systematic reviews

Websites excluded because they are not intended for patients and the public a

a These websites were excluded because they are not primarily intended for patients and the general public. However, some patients and members of the general public use these databases

Websites under development a

a Last accessed 14 February 2018

Included websites

a The headings used were inconsistent for all three

b We got an error message (“A technical error has occurred. Please try again later.”) when we used AND to limit searches on Informed Health , and no search results when we used quotation marks (e.g. “back pain”). It was possible to use this logic on the other two websites

Cochrane Evidence provides plain language summaries of over 7500 Cochrane Reviews, most of which are systematic reviews of the effects of treatments. The systematic reviews and the plain language summaries are prepared and updated by Cochrane review groups. Cochrane is a global independent network of researchers, professionals, patients, carers, and people interested in health, with over 37,000 contributors from more than 130 countries.

The plain language summaries include links to the full reviews. The full reviews are available in The Cochrane Library, which can be accessed for free in countries that have a national subscription or if the review or an update was published more than one year previously. The headings and content of the plain language summaries are inconsistent. The summaries include some background information, the authors’ conclusions, and links to other summaries that may be of interest. There is variability in the quality of the summaries. Some summaries include pop-up definitions (but not links to longer explanations) for some research and medical terms, and there is a glossary of terms relevant for Cochrane Reviews available on the Cochrane website. The summaries are translated into Chinese, Croatian, Czech, French, German, Japanese, Korean, Malay, Polish, Portuguese, Romanian, Russian, Spanish, Tamil, and Thai. The glossary is only in English.

No other information regarding treatments is provided in Cochrane Evidence , besides the plain language summaries of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane website, where Cochrane Evidence is found has other information about the Cochrane Colaboration. Navigation tools for Cochrane Evidence are limited to a simple search for the entire Cochrane website. It is possible to sort findings by relevance, alphabetically, or by date of publication; and to filter the summaries by broad health topics and whether the reviews are new or updated.

Informed Health is the English-language version of the German website Gesundheitsinformation.de. The website is prepared by the Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG) in Germany. IQWiG is a professionally-independent, scientific institute established under the Health Care Reform 2004.

The Informed Health website provides information about treatment effects together with other information for a wide range of topics. The website includes “research summaries” for some but not all treatments. “These are objective, brief summaries of the latest findings on a research question described in the title. They usually summarize the results of studies, for instance the results of one or (rarely) several systematic reviews or IQWiG reports. They also describe the study/studies in more detail and explain how the researchers came to their conclusions.” The website states that they “mainly use systematic reviews of studies to answer questions about the benefits and harms of medical interventions.” Links to systematic reviews are provided when these are used, but the reviews may not be freely available.

All of the research summaries that we examined (Additional file 1 ) included quantitative information about the size of the benefits, and they included frequencies for at least one outcome, but most often only for one outcome. The certainty of the evidence is not reported. All of the information is in plain language, written for patients and the public. There are hyperlinks to background information (but not pop-up definitions). There is a glossary of “medical and scientific” terms that includes primarily medical terms and few research terms.

In addition to information about treatments, Informed Health includes information about symptoms, causes, outlook, diagnosis, everyday life, where to learn more, and explanations (“Extras”) of topics such as how the body works, how treatments work, and types of treatments. Navigation tools for Informed Health include browsing by broad topic areas, an index (A to Z list) and a simple search. Search results can be sorted by relevance, the date information on the website was created, or the date it was updated.

PubMed Health specialized in systematic reviews of clinical effectiveness research. It included plain language summaries and abstracts of Cochrane Reviews; abstracts (technical summaries) of systematic reviews in the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) up to 31 March 2015; full texts of reviews from public agencies; information developed by public agencies for consumers and clinicians based on systematic reviews; and methods resources about the best research and statistical techniques for systematic reviews and clinical effectiveness research. PubMed Health was a service provided by the National Center for Biotechnology Information at the U.S. National Library of Medicine. It was discontinued October 31, 2018 “in an effort to consolidate similar resources and make information easier to find”. It included information from over 40,000 systematic reviews from a variety of sources, but plain language summaries were not available for most of those reviews. Links to the systematic reviews were provided, but not all of the reviews were freely available.

The reporting was inconsistent. Headings, reporting of effects, and reporting of the certainty of the evidence were inconsistent. PubMed Health had an extensive glossary (Health A – Z) and background information on drugs. Navigation tools included a simple search. Search results could be sorted by date of publication and filtered by Article types (including “Consumer information”); when information was added to PubMed Health , Content providers (including Cochrane and IQWiG); and Reviews with a quality assessment.

None of the three included websites includes links to ongoing trials and adverse effects are not consistently reported on any of the websites. All three include information about how up-to-date the information about treatment effects is.

PubMed Health was the easiest website to search, despite the large number of records that it includes. However, we had difficulties searching all three websites. We found information easily in Cochrane Evidence and Informed Health for one of the eight questions in Table Table1, 1 , and for three of the questions in PubMed Health (Additional file 1 ). Conversely, it was hard to find information (or we did not find any information) for the five questions in Cochrane Evidence , six questions in Informed Health , and three questions in PubMed Health . It was not possible to use Boolean logic when searching Informed Health . This was possible on the other two websites, but none of the three provided any instructions or help for searching.

When we found information, it was consistently available about benefits, but only Informed Health consistently reported this information quantitatively in the plain language summaries. Quantitative information was provided in the linked scientific abstracts. None of the websites consistently reported information about harms or the certainty of the evidence, although Cochrane plain language summaries in Cochrane Evidence and PubMed Health frequently reported the certainty of the evidence. When the certainty of the evidence was reported using GRADE or another systematic approach, there was not a link to an explanation of what the grade means.

Overall we were most satisfied with Cochrane Evidence for 2 questions, with Informed Health for one question, and with PubMed Health for 3 of our questions. We did not find information about treatment effects on any of the three websites for two questions: “Should I stop using phone, tablet, computer, and TV screens before going to bed (for insomnia)?” and “Should I get my osteoarthritic knee replaced?” Informed Health provided advice for the first question (“For instance, it might help to only listen to relaxing music before going to bed and keep from talking on the phone or playing computer or mobile phone games”), but no reference to research evidence for that advice. We easily found relevant systematic reviews for both of these questions in Epistemonikos (Additional file 1 ).

We identified three websites for patients and the public that provide free information about treatment effects based on systematic reviews. A fourth, promising website, CureFacts, was under development (Table (Table4), 4 ), and is still under development as of February 2019. Twenty-two other websites that provide free information for patients and the public claim to provide trustworthy, evidence-based information. However, it is not possible to know the extent to which the information they provide about treatment effects is based on systematic reviews, so is therefore less likely to be trustworthy. We considered four websites that provide access to systematic reviews, but none of these is intended for patients and the public (Table (Table3). 3 ). Nonetheless, some people may find these useful, particularly Epistemonikos . It includes over 100,000 systematic reviews with the abstracts translated to Arabic, Chinese, Dutch, French, German, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish. It is aimed for health professionals, researchers and policymakers but plain language summaries are not available for most of the reviews. Although it is not intended for patients and the public, it “has been used by well-informed lay people and journalists successfully” (Table (Table3 3 ).

We did not consider databases that are not free, such as Trip Pro, which includes access to over 100,000 systematic reviews; or patient information from web-based medical compendia for clinicians, such as Best Practice , Dynamed , and UptoDate. We also did not consider websites that provide information for patients and the public based on guidelines, such as the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance for patients; or websites that are limited to specific conditions or types of treatments.

The three websites for patients and the public that explicitly provided information about treatment effects based on systematic reviews were likely to appeal to different people and their appeal may vary depending on the question being asked. We found that we preferred each of the websites for at least one of the eight questions we used as test cases (Table (Table1). 1 ). We found PubMed Health somewhat easier to search, despite the large number of records it includes, and we found both Cochrane plain language summaries and Health Information research summaries when searching PubMed Health . Simple instructions regarding the use of Boolean logic and the use of quotations to limit searches would help improve the ease of use for all three websites. For example, the default for Cochrane Evidence appears to be to insert OR between words, resulting in large numbers of irrelevant hits.

All of the websites could be improved by more consistent use of headings and consistent reporting of both benefits and (especially) harms; inclusion of quantitative information about the size of the effects; and information about the certainty of the evidence based on the use of a consistent set of criteria, such as GRADE [ 29 – 31 ], and links to explanations of what the grades mean. Because many systematic reviews, including Cochrane Reviews, do not consistently provide this information, plain language summaries based on systematic reviews cannot always provide this information. However, they can alert users to the absence of trustworthy information about adverse effects, when this is the case, and it is possible to provide an assessment of the certainty of the evidence even when review authors have not done this [ 32 , 33 ].

All three websites provided plain language summaries of systematic reviews and all three had glossaries. However, none of the websites included both pop-up short definitions (which can be quickly accessed and read as scroll overs without having to go to another webpage) and links to longer explanations (that can be easily accessed when needed).

None of the websites included links to ongoing trials. This is something that, for example, NHS Choices does [ 34 ]. This is important because when there is important uncertainty about the effects of treatments, participating in a randomised trial may be the best option for patients [ 35 , 36 ].

We are not aware of any other studies that have attempted to systematically identify and evaluate websites that provide free access to information about the effects of treatments for patients and the public which is based on systematic reviews. There are thousands of websites that provide health information and we did not systematically screen all of these. Although we believe it is unlikely that there are other websites that meet our inclusion criteria, we did not consider websites for specific conditions or types of interventions, non-English language websites, or websites that were not freely accessible. Others might want to assess these and other sources of information about treatment effects in future studies.

"The evaluation criteria that we used were based on our judgement about what information is important and what is needed to make that information accessible. For example, providing a link to the systematic review enables people to go to the source of information about treatment effects for more information, if they desire. It also makes the basis of the information clear. Information about the size of effects and the certainty of the evidence is essential for making well-informed decisions. Basic search tools are necessary to make it easy to find information on the websites, and summaries that are written in plain language for patients and the public are more likely to be understandable than abstracts written for researchers or health professionals. Consistent headings, content, and use of language make it easier for users to become familiar with the websites and to find and understand information.

Our evaluation was based in part on searching for answers for eight treatment questions (Table (Table1). 1 ). The criteria that we used to assess what we found for each question did not require a great deal of judgement. Consequently, there were only minor disagreements in our assessments (Additional file 1 ), and those were easily resolved. It is uncertain how representative what we found for those questions is for what would be found for other treatment questions, but we believe they provided a fair basis for assessing the websites. Moreover, we sent full drafts of this report to people responsible for each website and their corrections did not substantially alter our assessments or conclusions.

We did not evaluate the readability of the plain language summaries and, although we described other information that each website provides, we did not evaluate whether the websites provided other information that patients and the public want or need to make informed decisions; for example, information about other treatment alternatives, costs, and people’s experiences with the treatment [ 37 , 38 ]. We also did not evaluate how users of the websites experience them [ 39 ]. All of these are potential areas for future research."

Conclusions

It is possible for patients and the public to access trustworthy information about the effects of treatments based on systematic reviews using two of the three websites included in this review. However, all three of these websites could be improved and made more useful and easier to use by consistently reporting information about the size of both the benefits and harms of treatments and the certainty of the evidence, and by making it easier to find relevant information.

Searching the three websites frequently yielded much irrelevant information. Users can limit searches by using Boolean logic - inserting AND between terms (e.g. for the condition and for the treatment) and quotation marks to indicate that words need to be next to each other; e.g. “back pain”. However, this is unlikely to be obvious to novice users. Some users may want to use sources that are not intended for patients and the public, such as Epistemonikos , if they are unable to find information on one of these websites. They also might want to consider searching for ongoing trials, if there is important uncertainty about the effects of relevant treatments.

There are many other websites that claim to provide evidence-based or reliable information about treatments, but it is difficult to assess the reliability of the information about treatment effects provided on those websites since they do not explicitly base that information on systematic reviews.

Additional file

Appendix review of online evidence-based patient info. Assessments of three included websites. Description of data: Search results and assessments of the information found in the three included websites for eight common health questions. (XLSX 29 kb)

Acknowledgements

With support from the James Lind Initiative, Anita Peerson prepared an earlier unpublished version of this review with advice from Iain Chalmers, Douglas Badenoch, Sarah Rosenbaum, and Astrid Austvoll-Dahlgren. We would like to thank the following colleagues for helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper: Astrid Austvoll-Dahlgren, Atle Fretheim, Claire Glenton, Hilda Bastian, Iain Chalmers, Jon Brasey, Karla Soares-Weiser, Marit Johansen, Marita Sporstøl Fønhus, Sarah Rosenbaum, Signe Flottorp.

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Abbreviations, authors’ contributions.

AO made all of the initial assessments and wrote the first draft of this report. EP checked all of the assessments and contributed to revisions of this report. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent for publication, competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Andrew D. Oxman, Email: on.enilno@namxo .

Elizabeth J. Paulsen, Email: [email protected] .

is an online, open access journal, dedicated to publishing medical research from all disciplines and therapeutic areas.

Impact Factor: 2.9 Citescore: 4.4 All metrics >>

The journal publishes all research study types, from protocols through phase I trials to meta-analyses, including small, specialist studies, and negative studies. Publishing procedures are built around fully open peer review and continuous publication, publishing research online as soon as the article is ready.

BMJ Open aims to promote transparency in the publication process by publishing reviewer reports and previous versions of manuscripts as pre-publication histories. Authors are asked to pay article-publishing charges on acceptance; the ability to pay does not influence editorial decisions.

All papers are included in MEDLINE/PubMed and Science Citation Index Expanded (Web of Science).

BMJ Open accepts submissions on a range of article types, including original research, cohort profiles and protocols.

The Author Information section provides specific article requirements to help you turn your research into an article suitable for BMJ Open.

Information is also provided on editorial policies and open access .

Press Releases

Health policy :

16 April 2024

Epidemiology :

26 March 2024

Complementary medicine :

13 February 2024

9 February 2024

Most Read Articles

Public health :

16 May 2023

Cardiovascular medicine :

28 March 2024

Evidence based practice :

22 May 2023

30 March 2024

Mental Health

Mental health :

15 May 2024

Recent Articles

17 May 2024

Anaesthesia :

Renal medicine :

General practice / Family practice :

Health services research :

Content Editors picks Highly accessed Open access

29 April 2024

Highly accessed Press release

17 April 2024

In the news Press release

27 March 2024

Highly accessed

Related Journals

BMJ Open Respiratory Research

BMJ Open Sport & Exercise Medicine

Isle of Man (GB) (IM)

Recruiter: Peel Medical Group Practice

Recruiter: Cwm Taf Morgannwg University Health Board

Worcester, Worcestershire

Recruiter: University of Worcester

Recruiter: Elysium Healthcare

Recruiter: The Shrewsbury and Telford Hospital NHS Trust

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Health Topics

- Drugs & Supplements

- Medical Tests

- Medical Encyclopedia

- About MedlinePlus

- Customer Support

Welcome to MedlinePlus

MedlinePlus is an online health information resource for patients and their families and friends. It is a service of the National Library of Medicine (NLM), the world's largest medical library, which is part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Learn more about MedlinePlus

For Businesses

For students & teachers, how to find credible medical websites for research.

EVERFI Content Team

The Internet is a powerful tool, but it is not without pitfalls. It is no secret that the Internet is the primary form of research for our students — medical information included.

Teaching our students how to use the Internet for medical information comes with a unique set of challenges. Below, we’ll break down how to judge the credibility of online sources.

What Do We Risk?

In a world defined by instant access to communication, we run the risk of our students leaping to incorrect conclusions. For medical information (used to inform medical decisions), this is incredibly dangerous.

Wrong, unsafe, or incorrectly understood medical information can have a very real impact on the lives of our students.

Online Medical Information: How Do We Determine Credibility?

The Who: Always Look to the Source First

The first step in gauging credibility is to analyze the source. Consider publications from the following:

- Mayo Clinic, a nonprofit academic medical center

- National Institutes of Health (NIH), a part of U.S. Department of Health and Human Services

- Johns Hopkins Hospital, one of the world’s premier teaching and biomedical research hospitals

The above institutions are examples of nonprofit, publicly funded, or university-affiliated medical centers. As a general rule of thumb, students can consider information from these sources to be impartial and accurate.

On the other hand, imagine information from the following fictional organizations:

- The Academy of Tobacco Studies, a for-profit research center funded by tobacco companies

- “Aunt Betsy Knows Best”, a blog selling herbal remedies for serious medical conditions

Clearly, these are not credible medical websites for research!

Yes, the examples are extreme. The core approach, however, remains the same — look to the source. If the source has an agenda, the website may lack credibility.

Tip: Websites ending in “.gov” (government) or “.edu” (top level domain for education) tend to be the most credible.

The What: What Information is Offered?

Consider the information offered by the website. For example, this article on the common cold from the Mayo Clinic gives a comprehensive overview of the disease. It offers general treatment tips, of course, but it doesn’t push a product — at best, it briefly mentions a generic medicine brand once or twice.

Tip: If a medical information website is telling the visitor to buy a specific product, it’s likely best to run in the other direction.

The When: Is the Information Current?

Outdated medical information is as potentially hazardous as incorrect content. It’s best to teach students to always check for a publication date.

Tip: The most credible online medical resources probably have the budget for quality web design. If the website looks and feels questionable, it probably is.

The Where: Where Did the Information Come From?

A few minutes spent poking around online can yield “evidence” that the 1969 Moon Landing is a government conspiracy and that smoking is good for your health. It’s vital that students understand where information comes from.

When our students stumble across medical information online, have them consider the following:

- What evidence does it provide?

- Is the evidence from a respectable, peer-reviewed medical publication?

- If the website provides studies as sources, do the studies back up the website author’s claims?

Tip: Medical studies have published abstracts — taking a minute to verify a study supports a website’s information is quick and easy.

The Why: Why Does This Website Exist?

As a pair of general rules:

- Credible online medical resources inform; they do not diagnose.

- Credible sources may recommend treatments; they do not sell medication.

Ask your students to take a minute and consider why a medical website exists. Informative articles from the Mayo Clinic, NIH, or Johns Hopkins exist to provide an objective understanding of a medical issue.

The more we instill a healthy sense of skepticism in our students, the better equipped they will be.

Tip: If a website pushes a treatment or recommends self-diagnosis without a doctor present, run for the hills!

What Are Some Credible Medical Websites For Research?

Our students can develop an appreciation for quality online medical information below:

- Johns Hopkins Medicine : premier teaching and biomedical research center

- Mayo Clinic : Nonprofit medical center

- DailyMed : Government-run drug information website

- MedlinePlus : Government-run health information website

- National Institutes of Health : Government-run health information website

Better Students, Better Research

There’s a lot of medical information on the Internet. Instilling our students with the right mindset for how to find credible medical information online is vital.

If our students can differentiate between credible medical websites and illegitimate ones, we can breathe a sigh of relief.

Real World Learning Matters

EVERFI empowers teachers to bring critical skills education into their classrooms at no cost. Get activated and join 50,000+ educators across North America!

Credible Sources for Students FAQs

Why do students need credible sources in their research papers.

Incorporating credible sources into research papers is a crucial aspect of academic writing. It serves multiple purposes, such as ensuring the accuracy and validity of the information presented, avoiding plagiarism, developing critical thinking skills, and building a strong academic reputation.

Want to prepare students for career and life success, but short on time?

Busy teachers use EVERFI’s standards-aligned, ready-made digital lessons to teach students to thrive in an ever-changing world.

Explore More Resources

10 teacher tips to encourage self-awareness in teens.

Check out these 10 tips for teachers to help guide teenagers toward becoming independent, healthy, and happy adults.

10 Teacher Mental Health Tips You Can Put Into Practice Today

There has been little focus on teachers balancing COVID-19 & remote teaching. That’s why we put together ten mental health tips for t ...

Elementary Schooled Podcast: What is the NFL Character Playbook Program for Students? with ...

Character Playbook course for middle and high school students, where students learn about character building and specific skills for ...

Teaching Data Literacy Skills

Students aren’t equipped with the best analytical tool kit to take in and process all this information. How do we go about teaching d ...

Teaching Budgeting: 3 Ways Educators Bring Budgeting to Life

A budget is just a plan for our money. When we are teaching budgeting basics to our students, we can frame that plan the way we would ...

Class Activities for Teaching the Psychology of Spending Money

Here are some interesting findings we can share with our students to help them understand spending habits and lesson ideas to help th ...

- Open access

- Published: 05 May 2024

The quality of life of men experiencing infertility: a systematic review

- Zahra Kiani ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4548-7305 1 ,

- Masoumeh Simbar ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2843-3150 2 ,

- Farzaneh Rashidi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7497-4180 3 ,

- Farid Zayeri ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7791-8122 4 &

- Homayoon Banaderakhsh ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8982-9381 5

BMC Public Health volume 24 , Article number: 1236 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

414 Accesses

Metrics details

Men experiencing infertility encounter numerous problems at the individual, family, and social levels as well as quality of life (QOL). This study was designed to investigate the QOL of men experiencing infertility through a systematic review.

Materials and methods

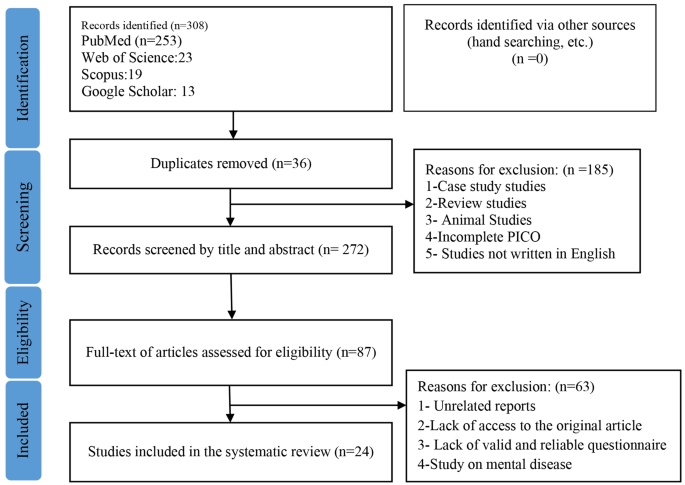

This systematic review was conducted without any time limitation (Retrieval date: July 1, 2023) in international databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, and Google Scholar. The search was performed by two reviewers separately using keywords such as QOL, infertility, and men. Studies were selected based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. The quality of the articles were evaluated based on the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. In the initial search, 308 studies were reviewed, and after removing duplicates and checking the title and abstract, the full text of 87 studies were evaluated.

Finally, 24 studies were included in the final review based on the research objectives. Based on the results, men’s QOL scores in different studies varied from 55.15 ± 13.52 to 91.45 ± 13.66%. Of the total reviewed articles, the lowest and highest scores were related to mental health problems and physical dimensions, respectively.

The reported findings vary across various studies conducted in different countries. Analysis of the factors affecting these differences is necessary, and it is recommended to design a standard tool for assessing the quality of life of infertile men. Given the importance of the QOL in men experiencing infertility, it is crucial to consider it in the health system. Moreover, a plan should be designed, implemented and evaluated according to each country’s contex to improve the quality of life of infertile men.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Defined as the absence of pregnancy after one or two years of unprotected sexual intercourse (without the use of contraceptive methods) [ 1 ], infertility is recognized as both a medical and social issue [ 2 ]. Based on the latest Word Health Organization (WHO) report in 2023, the pooled lifetime and period prevalence of infrtility are reported as 17.5% and 12.6%, respectively [ 3 ]. In this regard, male factors play a role in 50% of infertilities [ 4 ].

Complicated treatment protocol, difficult treatment process, semen analysis, multiple ultrasounds, invasive treatments, long waiting lists, and high financial costs for the clients who seek assisted reproductive techniques have been described as psychological stresses for infertile couples [ 5 , 6 ]. Moreover, the diagnosis and treatment of infertility can have negative impact on the frequency of sexual intercourse, self-esteem, and body image [ 5 ]. However, these men usually tend to suppress or deny their problems which may diminish their quality of life (QOL) over time [ 7 ]. This decreased QOL, in turn, can have a detrimental effect on their response to treatment [ 8 ].

The function of infertile people is under the influence of society, family, and the society culture. In many societies, infertility is primarily viewed as a medical problem, often neglecting its individual and social dimensions [ 9 ]. In other words, despite having the right attitude toward infertility, infertile people sometimes cannot adapt to the problem. Thus, non-compliance during the behavioral process may lead to additional problems and impair one’s QOL [ 10 ].

The WHO describes the QOL as people’s perspective of their life circumstances in terms of the cultural systems and standards of their environment, and how these perspectives are associated with their objectives, prospects, ideals, and apprehensions [ 11 ]. Recently, the QOL of men experiencing infertility as a main subject has been carefully considered by health investigators. Furthermore, because of men’s essential role in future phases of life, their QOL can significantly affect their health at both individual and societal levels [ 12 ].

Given the significance of QOL, its precise measurement is substantially important. In this regard, various tools have been designed and used in studies to examine this concept. A systematic study used the World Health Organization Quality Of Life )WHOQOL), 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36 ), and general QOL questionnaires. Based on the results, the QOL of men experiencing infertility was reported to be low in two studies that had used the SF-36 questionnaire. By contrast, the QOL of these men was high in a study that used the WHOQOL questionnaire. It was noted in this systematic review that although infertility has a negative effect on the mental health and sexual relationships of couples, there is no consensus regarding its effect on the QOL of infertile couples [ 13 ].

In Almutawa et al.‘s systematic review and meta-analysis 2023, it has been shown that the psychological disturbances in infertile women are higher than in men, and this difference in couples needs further investigation [ 14 ]. Chachavomich et al. 2010 showed that women’s quality of life is more affected by infertility than men study, which was a systematic review [ 12 ], . This study was conducted 14 years ago and due to the increase in the number of articles in this field, it needs to be re-examined.Given that no systematic review had been conducted to address the QOL of men experiencing infertility and considering the significance of this issue in therapeutic responses, this study examined the QOL of men experiencing infertility in the form of a systematic review.

Search strategy

To search and review the studies, reputable international databases and sites such as Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed, and Google Scholar were used. The search was performed using keywords such as QOL, infertility, and men (Table 1 ), without time limitation (Retrieval date: July 1, 2023), and using AND and OR operators, and specific search strategies were used for each database.

The search strategy of PubMed, Web of Science, and Scopus databases is as follows:

Pubmed (retrieval date: July 1, 2023)

Male [tiab] OR Males [tiab] OR Men [tiab] OR Man [tiab] OR Boy [tiab] OR Boys [tiab] AND Quality of Life [tiab] OR Health-Related Quality of Life [tiab] AND Infertility [tiab] OR Sterility OR Reproductive [tiab] OR Reproductive Sterility [tiab] OR Subfertility [tiab] Sub-Fertility [tiab].

Web of science (retrieval date: July 1, 2023)

((TI=(male OR males OR man OR men OR boy OR boys)) AND TI=(Quality of Life OR Health-Related Quality of Life OR Health-Related Quality of Life)) AND TI=(Infertility OR Sterility OR Reproductive OR Reproductive Sterility).

Scopus (retrieval date: July 1, 2023)

TITLE ( male OR males OR men OR man OR boy OR boys ) AND TITLE (quality AND of AND life OR health-related AND quality AND of AND life ) AND TITLE ( infertility OR sterility OR reproductive).

The method of presenting the article, describing the problem, data collection, data analysis, discussion, and conclusion of the findings were based on preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) 2020 [ 15 ]. The reviews were conducted separately by two reviewers, and the third reviewer was also used in case of disagreement between them.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Those studies with the following criteria were included in the review: (1) Observational studies; (2) Cross-sectional data from longitudinal studies; (3) Using valid tools for measuring the QOL; (4) Studies conducted on men of infertile couples (by men experiencing infertility we mean those men whose unprotected sexual intercourse during the past year did not lead to any pregnancy); (5) Minimum sample size of 30 subjects; (6) Subjects with no chronic disease, and (7) those men of infertile couples who were within the diagnostic process for infertility and before starting infertility treatment. The search and review process for this study were conducted in English, and there were no restrictions imposed on the inclusion of open-access studies.

Exclusion criteria included: (1) Case report studies; (2) Review studies; (3) Animal studies; (4) Studies on mental syndromes; (5) Studies not written in English; (6) Lack of access to the full text of the article, and (7) Unrelated reports.

The patient, intervention, comparison, outcome, and study design (PICOS)

PICOS model was used to help break down the searchable elements of the research question into (P) participants: men experiencing infertility (primary or secondary infertility) (I) intervention/exposure: not applicable; (C) control group: not applicable; (O) outcomes: evaluate infertile men’s QOL, which was measured using standard tools such as general or specific QOL questionnaire and (S) study type: Observational studies and Cross-sectional data from longitudinal studies.

Data extraction

The two reviewers independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the articles following the inclusion criteria, and the studies which did not have the required criteria were excluded. Then, the full text of the articles with inclusion criteria was reviewed and if appropriate, they were included in the study.

Required information, including authors’ names, year of publication, research location, sample size, QOL score, type of tool, type of infertility, mean age of men, and duration of infertility, were extracted from the studies.

Outcome measurement

The main outcome of this study was to evaluate QOL of men experiencing infertility, which was measured using standard tools such as a general or specific QOL questionnaire.

Quality evaluation

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale checklist was used to assess the quality of nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses [ 16 ]. This checklist consists of 5 parts that are representativeness of the sample, sample size, non-respondents, ascertainment of anxiety, and quality of descriptive statistics reporting. Each part gets a score of zero and one. Given the fact that the checklist has 5 items, the minimum, and maximum scores are 0 and 5, respectively. Then, studies were divided into high- and low-risk groups if their scores were ≤ 3 and more than 3 [ 16 ]. The quality assessment in this study was performed by two reviewers independently, and in case of disagreement between them, the third reviewer was asked to help. The coefficient of agreement of 0.7 and more among the reviewers was acceptable.

Ethical consideration

Ethics approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee, Faculty of Pharmacy and Nursing.

Midwifery, Shahid Beheshti University (Ethical code: IR.SBMU.PHARMACY.REC.1400.214). All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

After reviewing the title, abstract, and text of the articles in different stages (Fig. 1 ), finally, 24 articles were reviewed based on the inclusion criteria and research objectives and the coefficient of agreement among the reviewers was K = 0.81 (Table 2 ).

Flowchart for selection of studies