An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Biochem Med (Zagreb)

- v.23(2); 2013 Jun

The Chi-square test of independence

The Chi-square statistic is a non-parametric (distribution free) tool designed to analyze group differences when the dependent variable is measured at a nominal level. Like all non-parametric statistics, the Chi-square is robust with respect to the distribution of the data. Specifically, it does not require equality of variances among the study groups or homoscedasticity in the data. It permits evaluation of both dichotomous independent variables, and of multiple group studies. Unlike many other non-parametric and some parametric statistics, the calculations needed to compute the Chi-square provide considerable information about how each of the groups performed in the study. This richness of detail allows the researcher to understand the results and thus to derive more detailed information from this statistic than from many others.

The Chi-square is a significance statistic, and should be followed with a strength statistic. The Cramer’s V is the most common strength test used to test the data when a significant Chi-square result has been obtained. Advantages of the Chi-square include its robustness with respect to distribution of the data, its ease of computation, the detailed information that can be derived from the test, its use in studies for which parametric assumptions cannot be met, and its flexibility in handling data from both two group and multiple group studies. Limitations include its sample size requirements, difficulty of interpretation when there are large numbers of categories (20 or more) in the independent or dependent variables, and tendency of the Cramer’s V to produce relative low correlation measures, even for highly significant results.

Introduction

The Chi-square test of independence (also known as the Pearson Chi-square test, or simply the Chi-square) is one of the most useful statistics for testing hypotheses when the variables are nominal, as often happens in clinical research. Unlike most statistics, the Chi-square (χ 2 ) can provide information not only on the significance of any observed differences, but also provides detailed information on exactly which categories account for any differences found. Thus, the amount and detail of information this statistic can provide renders it one of the most useful tools in the researcher’s array of available analysis tools. As with any statistic, there are requirements for its appropriate use, which are called “assumptions” of the statistic. Additionally, the χ 2 is a significance test, and should always be coupled with an appropriate test of strength.

The Chi-square test is a non-parametric statistic, also called a distribution free test. Non-parametric tests should be used when any one of the following conditions pertains to the data:

- The level of measurement of all the variables is nominal or ordinal.

- The sample sizes of the study groups are unequal; for the χ 2 the groups may be of equal size or unequal size whereas some parametric tests require groups of equal or approximately equal size.

- The distribution of the data was seriously skewed or kurtotic (parametric tests assume approximately normal distribution of the dependent variable), and thus the researcher must use a distribution free statistic rather than a parametric statistic.

- The data violate the assumptions of equal variance or homoscedasticity.

- For any of a number of reasons ( 1 ), the continuous data were collapsed into a small number of categories, and thus the data are no longer interval or ratio.

Assumptions of the Chi-square

As with parametric tests, the non-parametric tests, including the χ 2 assume the data were obtained through random selection. However, it is not uncommon to find inferential statistics used when data are from convenience samples rather than random samples. (To have confidence in the results when the random sampling assumption is violated, several replication studies should be performed with essentially the same result obtained). Each non-parametric test has its own specific assumptions as well. The assumptions of the Chi-square include:

- The data in the cells should be frequencies, or counts of cases rather than percentages or some other transformation of the data.

- The levels (or categories) of the variables are mutually exclusive. That is, a particular subject fits into one and only one level of each of the variables.

- Each subject may contribute data to one and only one cell in the χ 2 . If, for example, the same subjects are tested over time such that the comparisons are of the same subjects at Time 1, Time 2, Time 3, etc., then χ 2 may not be used.

- The study groups must be independent. This means that a different test must be used if the two groups are related. For example, a different test must be used if the researcher’s data consists of paired samples, such as in studies in which a parent is paired with his or her child.

- There are 2 variables, and both are measured as categories, usually at the nominal level. However, data may be ordinal data. Interval or ratio data that have been collapsed into ordinal categories may also be used. While Chi-square has no rule about limiting the number of cells (by limiting the number of categories for each variable), a very large number of cells (over 20) can make it difficult to meet assumption #6 below, and to interpret the meaning of the results.

- The value of the cell expecteds should be 5 or more in at least 80% of the cells, and no cell should have an expected of less than one ( 3 ). This assumption is most likely to be met if the sample size equals at least the number of cells multiplied by 5. Essentially, this assumption specifies the number of cases (sample size) needed to use the χ 2 for any number of cells in that χ 2 . This requirement will be fully explained in the example of the calculation of the statistic in the case study example.

To illustrate the calculation and interpretation of the χ 2 statistic, the following case example will be used:

The owner of a laboratory wants to keep sick leave as low as possible by keeping employees healthy through disease prevention programs. Many employees have contracted pneumonia leading to productivity problems due to sick leave from the disease. There is a vaccine for pneumococcal pneumonia, and the owner believes that it is important to get as many employees vaccinated as possible. Due to a production problem at the company that produces the vaccine, there is only enough vaccine for half the employees. In effect, there are two groups; employees who received the vaccine and employees who did not receive the vaccine. The company sent a nurse to every employee who contracted pneumonia to provide home health care and to take a sputum sample for culture to determine the causative agent. They kept track of the number of employees who contracted pneumonia and which type of pneumonia each had. The data were organized as follows:

- Group 1: Not provided with the vaccine (unvaccinated control group, N = 92)

- Group 2: Provided with the vaccine (vaccinated experimental group, N = 92)

In this case, the independent variable is vaccination status (vaccinated versus unvaccinated). The dependent variable is health outcome with three levels:

- contracted pneumoccal pneumonia;

- contracted another type of pneumonia; and

- did not contract pneumonia.

The company wanted to know if providing the vaccine made a difference. To answer this question, they must choose a statistic that can test for differences when all the variables are nominal. The χ 2 statistic was used to test the question, “Was there a difference in incidence of pneumonia between the two groups?” At the end of the winter, Table 1 was constructed to illustrate the occurrence of pneumonia among the employees.

Results of the vaccination program.

Calculating Chi-square

With the data in table form, the researcher can proceed with calculating the χ 2 statistic to find out if the vaccination program made any difference in the health outcomes of the employees. The formula for calculating a Chi-Square is:

The first step in calculating a χ 2 is to calculate the sum of each row, and the sum of each column. These sums are called the “marginals” and there are row marginal values and column marginal values. The marginal values for the case study data are presented in Table 2 .

Calculation of marginals.

The second step is to calculate the expected values for each cell. In the Chi-square statistic, the “expected” values represent an estimate of how the cases would be distributed if there were NO vaccine effect. Expected values must reflect both the incidence of cases in each category and the unbiased distribution of cases if there is no vaccine effect. This means the statistic cannot just count the total N and divide by 6 for the expected number in each cell. That would not take account of the fact that more subjects stayed healthy regardless of whether they were vaccinated or not. Chi-Square expecteds are calculated as follows:

Specifically, for each cell, its row marginal is multiplied by its column marginal, and that product is divided by the sample size. For Cell 1, the math is as follows: (28 × 92)/184 = 13.92. Table 3 provides the results of this calculation for each cell. Once the expected values have been calculated, the cell χ 2 values are calculated with the following formula:

The cell χ 2 for the first cell in the case study data is calculated as follows: (23−13.93) 2 /13.93 = 5.92. The cell χ 2 value for each cellis the value in parentheses in each of the cells in Table 3 .

Cell expected values and (cell Chi-square values).

Once the cell χ 2 values have been calculated, they are summed to obtain the χ 2 statistic for the table. In this case, the χ 2 is 12.35 (rounded). The Chi-square table requires the table’s degrees of freedom (df) in order to determine the significance level of the statistic. The degrees of freedom for a χ 2 table are calculated with the formula:

For example, a 2 × 2 table has 1 df. (2−1) × (2−1) = 1. A 3 × 3 table has (3−1) × (3−1) = 4 df. A 4 × 5 table has (4−1) × (5−1) = 3 × 4 = 12 df. Assuming a χ 2 value of 12.35 with each of these different df levels (1, 4, and 12), the significance levels from a table of χ 2 values, the significance levels are: df = 1, P < 0.001, df = 4, P < 0.025, and df = 12, P > 0.10. Note, as degrees of freedom increase, the P-level becomes less significant, until the χ 2 value of 12.35 is no longer statistically significant at the 0.05 level, because P was greater than 0.10.

For the sample table with 3 rows and 2 columns, df = (3−1) × (2−1) = 2 × 1 = 2. A Chi-square table of significances is available in many elementary statistics texts and on many Internet sites. Using a χ 2 table, the significance of a Chi-square value of 12.35 with 2 df equals P < 0.005. This value may be rounded to P < 0.01 for convenience. The exact significance when the Chi-square is calculated through a statistical program is found to be P = 0.0011.

As the P-value of the table is less than P < 0.05, the researcher rejects the null hypothesis and accepts the alternate hypothesis: “There is a difference in occurrence of pneumococcal pneumonia between the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups.” However, this result does not specify what that difference might be. To fully interpret the result, it is useful to look at the cell χ 2 values.

Interpreting cell χ 2 values

It can be seen in Table 3 that the largest cell χ 2 value of 5.92 occurs in Cell 1. This is a result of the observed value being 23 while only 13.92 were expected. Therefore, this cell has a much larger number of observed cases than would be expected by chance. Cell 1 reflects the number of unvaccinated employees who contracted pneumococcal pneumonia. This means that the number of unvaccinated people who contracted pneumococcal pneumonia was significantly greater than expected. The second largest cell χ 2 value of 4.56 is located in Cell 2. However, in this cell we discover that the number of observed cases was much lower than expected (Observed = 5, Expected = 12.57). This means that a significantly lower number of vaccinated subjects contracted pneumococcal pneumonia than would be expected if the vaccine had no effect. No other cell has a cell χ 2 value greater than 0.99.

A cell χ 2 value less than 1.0 should be interpreted as the number of observed cases being approximately equal to the number of expected cases, meaning there is no vaccination effect on any of the other cells. In the case study example, all other cells produced cell χ 2 values below 1.0. Therefore the company can conclude that there was no difference between the two groups for incidence of non-pneumococcal pneumonia. It can be seen that for both groups, the majority of employees stayed healthy. The meaningful result was that there were significantly fewer cases of pneumococcal pneumonia among the vaccinated employees and significantly more cases among the unvaccinated employees. As a result, the company should conclude that the vaccination program did reduce the incidence of pneumoccal pneumonia.

Very few statistical programs provide tables of cell expecteds and cell χ 2 values as part of the default output. Some programs will produce those tables as an option, and that option should be used to examine the cell χ 2 values. If the program provides an option to print out only the cell χ 2 value (but not cell expecteds), the direction of the χ 2 value provides information. A positive cell χ 2 value means that the observed value is higher than the expected value, and a negative cell χ 2 value (e.g. −12.45) means the observed cases are less than the expected number of cases. When the program does not provide either option, all the researcher can conclude is this: The overall table provides evidence that the two groups are independent (significantly different because P < 0.05), or are not independent (P > 0.05). Most researchers inspect the table to estimate which cells are overrepresented with a large number of cases versus those which have a small number of cases. However, without access to cell expecteds or cell χ 2 values, the interpretation of the direction of the group differences is less precise. Given the ease of calculating the cell expecteds and χ 2 values, researchers may want to hand calculate those values to enhance interpretation.

Chi-square and closely related tests

One might ask if, in this case, the Chi-square was the best or only test the researcher could have used. Nominal variables require the use of non-parametric tests, and there are three commonly used significance tests that can be used for this type of nominal data. The first and most commonly used is the Chi-square. The second is the Fisher’s exact test, which is a bit more precise than the Chi-square, but it is used only for 2 × 2 Tables ( 4 ). For example, if the only options in the case study were pneumonia versus no pneumonia, the table would have 2 rows and 2 columns and the correct test would be the Fisher’s exact. The case study example requires a 2 × 3 table and thus the data are not suitable for the Fisher’s exact test.

The third test is the maximum likelihood ratio Chi-square test which is most often used when the data set is too small to meet the sample size assumption of the Chi-square test. As exhibited by the table of expected values for the case study, the cell expected requirements of the Chi-square were met by the data in the example. Specifically, there are 6 cells in the table. To meet the requirement that 80% of the cells have expected values of 5 or more, this table must have 6 × 0.8 = 4.8 rounded to 5. This table meets the requirement that at least 5 of the 6 cells must have cell expected of 5 or more, and so there is no need to use the maximum likelihood ratio chi-square. Suppose the sample size were much smaller. Suppose the sample size was smaller and the table had the data in Table 4 .

Example of a table that violates cell expected values.

Sample raw data presented first, sample expected values in parentheses, and cell follow the slash.

Although the total sample size of 39 exceeds the value of 5 cases × 6 cells = 30, the very low distribution of cases in 4 of the cells is of concern. When the cell expecteds are calculated, it can be seen that 4 of the 6 cells have expecteds below 5, and thus this table violates the χ 2 test assumption. This table should be tested with a maximum likelihood ratio Chi-square test.

When researchers use the Chi-square test in violation of one or more assumptions, the result may or may not be reliable. In this author’s experience of having output from both the appropriate and inappropriate tests on the same data, one of three outcomes are possible:

First, the appropriate and the inappropriate test may give the same results.

Second, the appropriate test may produce a significant result while the inappropriate test provides a result that is not statistically significant, which is a Type II error.

Third, the appropriate test may provide a non-significant result while the inappropriate test may provide a significant result, which is a Type I error.

Strength test for the Chi-square

The researcher’s work is not quite done yet. Finding a significant difference merely means that the differences between the vaccinated and unvaccinated groups have less than 1.1 in a thousand chances of being in error (P = 0.0011). That is, there are 1.1 in one thousand chances that there really is no difference between the two groups for contracting pneumococcal pneumonia, and that the researcher made a Type I error. That is a sufficiently remote probability of error that in this case, the company can be confident that the vaccination made a difference. While useful, this is not complete information. It is necessary to know the strength of the association as well as the significance.

Statistical significance does not necessarily imply clinical importance. Clinical significance is usually a function of how much improvement is produced by the treatment. For example, if there was a significant difference, but the vaccine only reduced pneumonias by two cases, it might not be worth the company’s money to vaccinate 184 people (at a cost of $20 per person) to eliminate only two cases. In this case study, the vaccinated group experienced only 5 cases out of 92 employees (a rate of 5%) while the unvaccinated group experienced 23 cases out of 92 employees (a rate of 25%). While it is always a matter of judgment as to whether the results are worth the investment, many employers would view 25% of their workforce becoming ill with a preventable infectious illness as an undesirable outcome. There is, however, a more standardized strength test for the Chi-Square.

Statistical strength tests are correlation measures. For the Chi-square, the most commonly used strength test is the Cramer’s V test. It is easily calculated with the following formula:

Where n is the number of rows or number of columns, whichever is less. For the example, the V is 0.259 or rounded, 0.26 as calculated below.

The Cramer’s V is a form of a correlation and is interpreted exactly the same. For any correlation, a value of 0.26 is a weak correlation. It should be noted that a relatively weak correlation is all that can be expected when a phenomena is only partially dependent on the independent variable.

In the case study, five vaccinated people did contract pneumococcal pneumonia, but vaccinated or not, the majority of employees remained healthy. Clearly, most employees will not get pneumonia. This fact alone makes it difficult to obtain a moderate or high correlation coefficient. The amount of change the treatment (vaccine) can produce is limited by the relatively low rate of disease in the population of employees. While the correlation value is low, it is statistically significant, and the clinical importance of reducing a rate of 25% incidence to 5% incidence of the disease would appear to be clinically worthwhile. These are the factors the researcher should take into account when interpreting this statistical result.

Summary and conclusions

The Chi-square is a valuable analysis tool that provides considerable information about the nature of research data. It is a powerful statistic that enables researchers to test hypotheses about variables measured at the nominal level. As with all inferential statistics, the results are most reliable when the data are collected from randomly selected subjects, and when sample sizes are sufficiently large that they produce appropriate statistical power. The Chi-square is also an excellent tool to use when violations of assumptions of equal variances and homoscedascity are violated and parametric statistics such as the t-test and ANOVA cannot provide reliable results. As the Chi-Square and its strength test, the Cramer’s V are both simple to compute, it is an especially convenient tool for researchers in the field where statistical programs may not be easily accessed. However, most statistical programs provide not only the Chi-square and Cramer’s V, but also a variety of other non-parametric tools for both significance and strength testing.

Potential conflict of interest

None declared.

Accessibility Links

- Skip to content

- Skip to search IOPscience

- Skip to Journals list

- Accessibility help

- Accessibility Help

Click here to close this panel.

Purpose-led Publishing is a coalition of three not-for-profit publishers in the field of physical sciences: AIP Publishing, the American Physical Society and IOP Publishing.

Together, as publishers that will always put purpose above profit, we have defined a set of industry standards that underpin high-quality, ethical scholarly communications.

We are proudly declaring that science is our only shareholder.

A study of Hepatitis B virus infection using chi-square statistic

Oluwole A Odetunmibi 1 , Adebowale O Adejumo 2 and Timothy A Anake 1

Published under licence by IOP Publishing Ltd Journal of Physics: Conference Series , Volume 1734 , International Conference on Recent Trends in Applied Research (ICoRTAR) 2020 14-15 August 2020, Nigeria Citation Oluwole A Odetunmibi et al 2021 J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 1734 012010 DOI 10.1088/1742-6596/1734/1/012010

Article metrics

22817 Total downloads

Share this article

Author e-mails.

Author affiliations

1 Department of Mathematics, Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria

2 Department of Statistics, University of Ilorin, Ilorin, Nigeria

Buy this article in print

Hepatitis B is caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV) and it affects livers. It has been established that the disease is a serious medical condition caused by an overpowering immune response to infection. To this effect, there is a need for cross examination of records of patients on this disease to ascertain the factors that could be responsible for the survival or dying from this disease. Descriptive analysis of the data showed that sexually active age bracket (31 – 50) are greatly affected by the disease while female accounted for majority of those that are tested positive to the disease. Chi squared statistic was used to test for independence between age and gender of those who tested positive to disease between 2006 and 2015 in Lagos state, Nigeria. It was discovered that, both variables of age and gender are not independent which means there is association between the Age and Gender of HBV patients.

Export citation and abstract BibTeX RIS

Content from this work may be used under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 licence . Any further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the title of the work, journal citation and DOI.

- Open access

- Published: 17 May 2024

Association between preoperative anxiety states and postoperative complications in patients with esophageal cancer and COPD: a retrospective cohort study

- Yu Rong 1 ,

- Yanbing Hao 1 ,

- Dong Wei 1 ,

- Yanming Li 1 ,

- Wansheng Chen 1 ,

- Li Wang 2 &

- Tian Li 3

BMC Cancer volume 24 , Article number: 606 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

Esophageal cancer brings emotional changes, especially anxiety to patients. Co-existing anxiety makes the surgery difficult and may cause complications. This study aims to evaluate effects of anxiety in postoperative complications of esophageal cancer patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease ( COPD).

Patients with esophageal cancer and co-existing COPD underwent tumor excision. Anxiety was measured using Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD) before surgery. Clavien-Dindo criteria were used to grade surgical complications. A multiple regression model was used to analyze the relationship between anxiety and postoperative complications. The chi-square test was used to compare the differences in various types of complications between the anxiety group and the non-anxiety group. A multinomial logistic regression model was used to analyze the influencing factors of mild and severe complications.

This study included a total of 270 eligible patients, of which 20.7% had anxiety symptoms and 56.6% experienced postoperative complications. After evaluation by univariate analysis and multivariate logistic regression models, the risk of developing complications in anxious patients was 4.1 times than non-anxious patients. Anxious patients were more likely to develop pneumonia, pyloric obstruction, and arrhythmia. The presence of anxiety, surgical method, higher body mass index (BMI), and lower preoperative oxygen pressure may increase the incidence of minor complications. The use of surgical methods, higher COPD assessment test (CAT) scores, and higher BMI may increase the incidence of major complications, while anxiety does not affect the occurrence of major complications ( P = 0.054).

Preoperative anxiety is associated with postoperative complications in esophageal cancer patients with co-existing COPD. Anxiety may increase the incidence of postoperative complications, especially minor complications in patient with COPD and esophageal cancer.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

With the rapid advance of medical technology, the theranostics of cancer patients has significantly improved [ 1 ]. However, a neoplastic pathological report usually means “death penalty” and trigger strong emotional changes [ 2 ]. Research on the psychological distress of cancer patients had already begun in the 1980s [ 3 ]. Anxiety is a type of mental disorder, and a nationwide epidemiological study in China reported that anxiety is the most common type of mental disorder [ 4 ]. Among cancer patients, anxiety is an emotional response to uncertainty, distress, and the threat of death., which are due to the uncertainty of therapeutic outcomes, fear of pain, and the possibility of death [ 5 ]. Indeed, anxiety has a motivating effect on patients to endure cancer treatment despite potential pain. However, it can also lead to a decrease in quality of life, compliance with treatment, and increased hospital stays and disability rates [ 6 ].

Globally, in 2020, the age-standardized incidence and mortality rate were 6.3 cases and 5.6 cases per 100,000 people, respectively [ 7 ]. Research has found that anxiety may be an pivotal factor contributing to the incidence of esophageal cancer [ 8 ]. Among patients who have already developed esophageal cancer, most of them are already in advanced stages when seeking medical attention. Surgical treatment is still the main treatment method for esophageal cancer patients at present [ 9 ]. However, only one-third of patients have the opportunity to receive surgical treatment. Anxiety may be due to the heavy burden of medical expenses, obvious difficulties in eating, fear of surgical risks, as well as restrictive and absorptive changes in gastrointestinal physiology and various postoperative complications [ 10 , 11 , 12 ].

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a disease characterized by irreversible expiratory airflow limitation [ 13 ], is an independent risk factor for postoperative pulmonary complications in esophageal cancer [ 14 ]. As the global aging population accelerates, the proportion of esophageal cancer patients with COPD will further increase [ 15 ]. The prevalence of anxiety is high among COPD patients, with a review indicating that 10–90% of COPD patients experience anxiety [ 16 ]. However, previous studies rarely investigated the impact of anxiety on postoperative complications in patients with esophageal cancer and COPD. Therefore, we conducted this study to evaluate whether anxiety would have an impact on the occurrence and severity of postoperative complications in patients with esophageal cancer complicated by COPD, aiming to provide better guidance for the perioperative management.

Study design

This study retrospectively reviewed patients with esophageal cancer who underwent surgical treatment in Department of Thoracic, First Affiliated Hospital of Hebei North University between Jan 2010 to Dec 2018. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Hebei North University (K2018075). The inclusion criteria for patients were: (1) postoperative pathology suggests squamous cell carcinoma; (2) exclusion of other organ metastasis by imaging examination; (3) pathological staging ranging from stage IA to IVA. The exclusion criteria were: (1) lack of pulmonary function test results; (2) history of other malignant tumors within five years; (3) FEV1/FVC > 70% after bronchodilator use; (4) non-curative surgery for esophageal cancer. None of the patients had received preoperative neoadjuvant therapy. The postoperative pathological staging of esophageal cancer was performed according to the eighth edition of the esophageal cancer staging system [ 17 ].

Definition and measurement methods of variables

Anxiety was assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HAD) during routine evaluation upon admission. The evaluation period covered the patient’s emotional state in the past month. A score of 0–7 was considered as no anxiety, while a score greater than 7 indicated the presence of anxiety. If the patient was unable to read, the attending physician would read the content of the scale and ask the patient to make an assessment. The pulmonary function test was performed after the bronchodilator was inhaled. FEV1/FVC < 70% was used to classify the severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease according to the GOLD guidelines. Mild: FEV1 ≥ 80% predicted value, moderate: 50% predicted value ≤ FEV1 < 80% predicted value, severe: 30% predicted value ≤ FEV1 < 50% predicted value, very severe: FEV1 < 30% predicted value. The Clavien-Dindo classification system (CDC) was used to grade postoperative complications [ 18 ]. According to the level of treatment required for postoperative complications, they are divided into the following five grades: Grade I: no medication, surgery, endoscopy, radiation intervention or other treatments are required (use of antiemetics, analgesics, diuretics, electrolytes, and physical therapy is allowed). Grade II: other medications are required to treat Grade I complications. Grade IIIa: surgical, endoscopic or radiation treatment under local anesthesia. Grade IIIb: surgical, endoscopic or radiation treatment under general anesthesia. Grade IVa: single organ dysfunction, IVb: multiple organ dysfunction. Grade V: death. This includes both pulmonary and other postoperative complications, with Grade II and below being classified as mild complications, and Grade III and above being classified as severe complications [ 19 ]. The highest grade of complications experienced by a patient is recorded as the overall grade of that patient. Pneumonia is defined as a respiratory tract infection that requires antibiotic treatment, and is diagnosed if one or more of the following criteria are met: new onset of cough or change in the character of sputum, chest X-ray or computed tomography scan showing new infiltrates or worsening of existing infiltrates compared to previous images, fever (temperature > 38.0℃), and/or white blood cell count > 12 × 10 9 /L [ 20 ]. Bronchial asthma is defined as expiratory wheezing newly discovered after treatment with bronchodilators. Acute exacerbation of COPD is defined as worsening respiratory symptoms, increased sputum production, difficulty breathing, and asthma attacks compared to before [ 21 ]. Sepsis is defined as a clear infectious focus and meeting two or more of the following conditions: body temperature < 36 °C or > 38 °C; or heart rate > 90 beats/minute; or respiratory rate > 20 breaths/minute; or PaCO2 < 32mmHg; or white blood cell count < 4000/mm³ or > 12,000/mm³; or more than 10% immature neutrophils [ 22 ]. Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is defined as arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2)/fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) < 200, positive end-expiratory pressure > 5 cm H 2 O, and duration > 24 h [ 23 ].

Treatment methods and procedures

All patients underwent esophageal cancer resection and thoracic or cervical anastomosis. The choice of minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) or open esophagectomy (OE) was based on the preference of the patient or surgeon. In particular, MIE procedure typically employs McKeown procedure and Ivor-Lewis procedure, with the selection of procedure primarily contingent upon the tumor’s location in the patient. In the case of patients presenting with a tumor positioned at upper thoracic esophagus, McKeown procedure is typically employed to perform an anastomosis at the cervical region. This approach is undertaken to enhance the likelihood of achieving a greater negative rate at the esophageal margin. Conversely, for patients with a tumor located at a lower level, Ivor-Lewis procedure is more frequently chosen as it allows for the preservation of a longer esophagus and a reduction in the occurrence of postoperative reflux. A two-field lymphadenectomy were performed for all patients. The lymph node dissection performed during minimally invasive esophagectomy (MIE) encompasses a comprehensive range of lymph nodes, including those located in the thoracic region (such as the left and right recurrent laryngeal nerve, paraesophageal, paratracheal, subcarinal, supradiaphragmatic, and posterior mediastinal lymph nodes) as well as those in the abdominal region. All patients were routinely admitted to the intensive care unit to stabilize their condition and remove the tracheal tube after surgery. Patients whose symptoms were stable were transferred back to the general ward on 1st day. Patient-controlled analgesia with a pain pump was used for postoperative pain management. If the patient’s condition is stable, electrolyte-containing fluids can be administered through a gastric or jejunal nutrition tube 48 h after surgery. If there is no abdominal pain or abnormal drainage from the closed chest drainage tube, enteral nutrition solution can be given 96 h after surgery. When the patient is able to consume liquid diet and there is no obvious food residue in the drainage from the chest drainage tube, and the daily amount of drainage is less than 200 ml, removal of the chest drainage tube can be considered for discharge preparation. After discharge, supplementary feeding was continued through a gastric or jejunal nutrition tube.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range). Categorical variables are expressed as frequency (%). T-test is used to compare the differences between continuous variables with normal distribution and equal variances. Chi-square test is used to compare the differences between categorical variables. Whether to adjust for covariates is based on the following two criteria: the regression coefficient p -value of the covariate on the outcome variable is < 0.10, or introducing the covariate into the basic model leads to a change in the regression coefficient of the risk factor of more than 10% [ 24 ]. We used a binary logistic regression model to assess the relationship between anxiety and postoperative complications. Three models were used, adjusting for confounding variables that may affect the association between anxiety and postoperative complications in a stepwise manner. Model 1 was unadjusted, model was 2 adjusted for demographic parameters in model 1: gender (male, female), age (continuous), and model 3 was adjusted for Body mass index (BMI), COPD Assessment Test (CAT) score, preoperative arterial oxygen pressure (PaO 2 ), Surgical procedure (MIE and OE), FEV1 as a percentage of predicted value (FEV1% Predicted), smoking index, and tumor staging based on model 2. Multinomial logistic regression was used to analyze the factors affecting minor and major postoperative complications. Data were analyzed using the statistical packages R (The R Foundation; http://www.r-project.org ; version 4.2.0 2022-04-22), EmpowerStats (R) ( www.empowerstats.com , X&Y Solutions, inc. Boston MA), and SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp). All tests were conducted at a two-sided significance level of P < 0.05.

Baseline data of patients

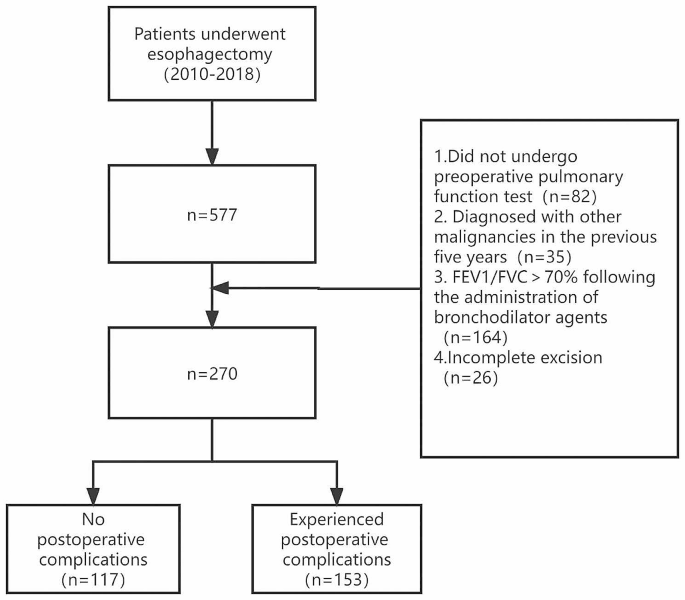

A total of 577 patients underwent radical esophagectomy during this period. Excluding 82 patients who did not undergo preoperative pulmonary function tests, 35 patients who developed other malignant tumors within five years, 164 patients without COPD, and 26 patients who underwent palliative resection, a total of 270 (242 males) eligible patients were finally included in the study. The mean age was 62.8 ± 8.6 years. There were 56 patients with anxiety (20.7%), and a total of 153 patients (56.6%) experienced postoperative complications. The patients’ mean BMI was 20.9 ± 2.2, mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 61.7 ± 4.2, and 132 patients underwent minimally invasive surgery (48.9%). The age-corrected comorbidity index was 3.3 ± 1.1, and tumor staging was as follows: stage I: 83 (30.7%), stage II: 73 (27.0%), stage III: 94 (34.8%), stage IV: 20 (7.4%). The baseline data of the patients are summarized in Table 1 . The study flow chart is presented in Fig. 1 .

Study Flow Diagram

Relationship between anxiety and postoperative complications

Table 2 shows the results of the univariate analysis. These results suggest that BMI, CAT score, surgical procedures, FEV1 as a percentage of predicted, anxiety, and smoking index may be associated with the occurrence of postoperative complications. In contrast, gender, age, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), PaO 2 , preoperative CO2 pressure (PaCO2), preoperative albumin concentration, FVC, FEV1, FEV1/FVC, alcohol consumption, smoking, and tumor staging are not significantly associated with the occurrence of complications. The results of the multivariate logistic regression are shown in Table 3 , including the unadjusted model and the adjusted models. In the unadjusted model, the risk of developing complications in patients with anxiety was four times higher than that in non-anxious patients (OR: 4.0, 95% CI: 2.0 to 8.2, P < 0.001). In adjusted model 1 (adjusting for demographic characteristics: age, gender), the OR was 4.1 (95% CI: 2.0 to 8.3, P < 0.001). In adjusted model 2 (fully adjusted model), the risk of developing complications in anxious patients was 4.1 times higher than that in non-anxious patients (OR: 4.1, 95% CI: 1.9 to 8.9, P < 0.001).

Types of complications and anxiety

Among the complications that occurred, the incidence rates in the group with combined anxiety were as follows: pneumonia (37.5%), arrhythmia (21.4%), atelectasis requiring bronchoscopy (19.6%), acute exacerbation of COPD (16.1%), pleural effusion requiring additional drainage (14.3%), anastomotic fistula (14.3%), wound infection (14.3%), recurrent laryngeal nerve injury (12.5%), pyloric obstruction (7.1%), asthma (7.1%), ARDS (7.1%), gastroparesis (5.4%), pneumothorax requiring re-intubation (3.6%), systemic sepsis (3.6%), heart failure (1.8%), and death (1.8%). The incidence rates in the group without anxiety were as follows: pneumonia (24.3%), atelectasis requiring bronchoscopy (13.6%), pleural effusion requiring additional drainage (12.6%), acute exacerbation of COPD (10.7%), recurrent laryngeal nerve injury (9.3%), anastomotic fistula (7.9%), wound infection (7.5%), arrhythmia (6.1%), asthma (5.6%), ARDS (5.6%), pneumothorax requiring re-intubation (3.7%), heart failure (3.7%), gastroparesis (2.8%), chylothorax (1.9%), pyloric obstruction (0.9%), systemic sepsis (0.9%), and death (0.9%). Table 4 shows the differences in the types of complications between the group with anxiety and without anxiety. Patients with anxiety were more likely to develop pneumonia (OR: 1.9, 95% CI: 1.0 to 3.5, P = 0.048), pyloric obstruction (OR: 8.2, 95% CI: 1.5 to 45.7, P = 0.022), and arrhythmia (OR: 4.2, 95% CI: 1.8 to 10.0, P < 0.001).

Severity of complications and anxiety

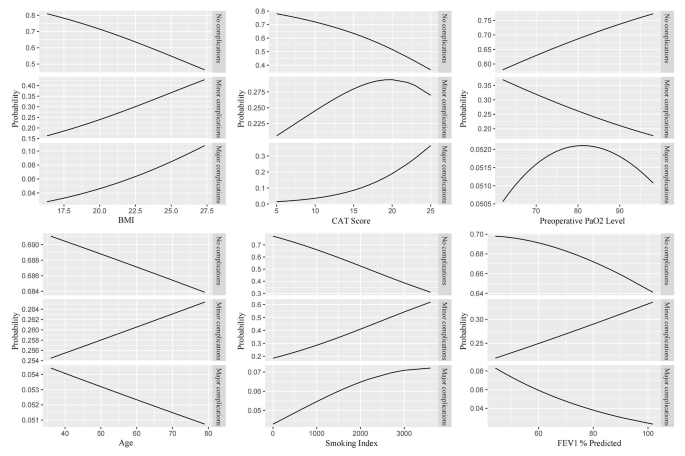

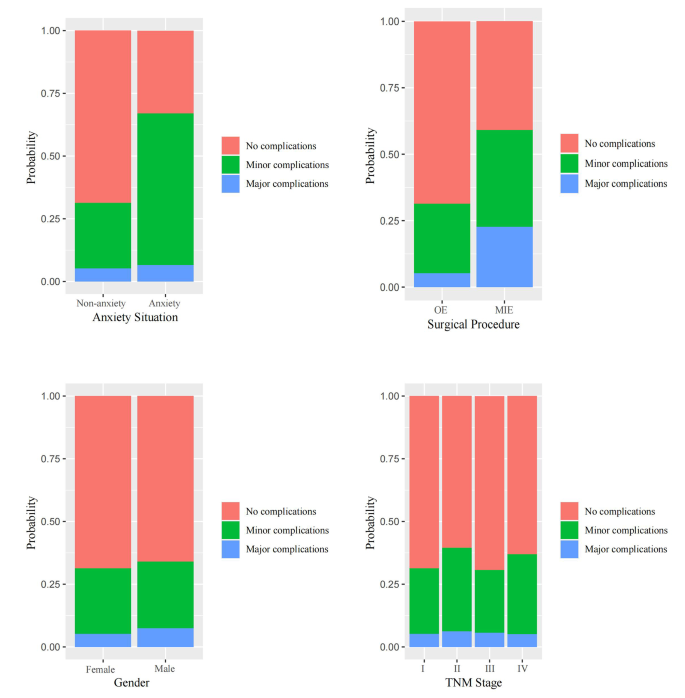

Among all 153 patients who experienced complications, there were 98 cases of minor complications, of which 32 cases (32.6%) had anxiety; 55 cases of major complications, of which 13 cases (23.6%) had anxiety. The results of the multinomial logistic regression (Table 5 ) showed that compared with patients without complications, the presence of anxiety (OR: 4.8, 95% CI: 2.2 to 10.6, P < 0.001), the use of OE procedure (OR: 2.3, 95% CI: 1.3 to 4.4, P = 0.007), higher BMI (OR: 1.1, 95% CI: 1.0 to 1.3, P = 0.041), and lower PaO 2 (OR: 1.0, 95% CI: 0.9 to 1.0, P = 0.041) may increase the occurrence of minor complications. The use of OE procedure (OR: 7.3, 95% CI: 3.2 to 16.6, P < 0.001), higher CAT scores (OR: 1.2, 95% CI: 1.1 to 1.4, P = 0.007), and higher BMI (OR: 1.2, 95% CI: 1.0 to 1.4, P = 0.034) may increase the occurrence of major complications, while anxiety does not affect the occurrence of major complications ( P = 0.054). The predictive results of each variable for the severity of complications are shown in Figs. 2 and 3 .

The predictive results of each continuous independent variable on the severity of complications

The predictive results of each categorical independent variable on the severity of complications

Main finding and interpretation

In this study, we found a significant correlation between anxiety and postoperative complications in patients with esophageal cancer combined with COPD. Neoplasms remain the main chronic diseases worldwide [ 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 ]. The results suggest that anxiety is a contributing factor to the occurrence of postoperative complications. After controlling for other variables, the likelihood of postoperative complications in patients with anxiety was approximately 4.1 times higher than in patients without anxiety. Among the types of complications, the incidence of postoperative pneumonia, arrhythmia, and pyloric obstruction was higher in anxious patients than non-anxious patients. Compared to patients without complications, anxiety increased the incidence of mild postoperative complications.

A study on the complications related to esophagectomy using an internationally standardized dataset showed that the overall incidence of postoperative complications after esophagectomy was approximately 59%, with pneumonia being the most common complication among all [ 31 ]. Our study results are similar to those of the standardized study. Approximately one-fifth of patients in previous studies were found to have anxiety, while the proportion of anxiety in esophageal cancer patients found in previous studies was even higher, accounting for as much as one-fourth or more [ 32 , 33 ]. One possible reason for this difference is that our study did not include late-stage patients who were no longer eligible for surgery, while late-stage cancer patients often have a shorter survival time, more obvious symptoms, and are more likely to experience anxiety [ 34 , 35 , 36 ]. Another possible reason is that different cultural backgrounds may lead to differences in the perception of emotional states. For example, some studies have shown that anxiety levels in Asian populations tend to be lower than those in non-Asian populations [ 37 , 38 ].

In the 1980s, researchers began to pay attention to the impact of preoperative anxiety on postoperative recovery [ 39 , 40 ]. These studies have shown that preoperative anxiety may lead to delayed postoperative recovery and increased incidence of complications. Measures such as preoperative decompression and sedatives have been used to alleviate patients’ anxiety in order to better promote postoperative recovery. Research suggests that anxiety is a contributing factor to postoperative complications [ 41 ]. This is consistent with our research findings. One reason is that preoperative psychological factors can affect physiological functions. Anxiety can cause overactivation of the sympathetic nervous system, which in turn leads to changes in the secretion levels of hormones such as cortisol and catecholamines [ 42 , 43 , 44 ]. The consequences of these elevated hormones include suppression of the immune system, making patients more susceptible to postoperative complications such as wound infection, anastomotic fistula, and pneumonia [ 45 ]. In addition, patients with preoperative anxiety require higher doses of sedatives to achieve adequate levels of sedation [ 46 ], and higher doses of sedatives are closely related to postoperative nausea, vomiting, and cardiorespiratory complications [ 47 ].

Unlike other studies, all patients included in our study had COPD. The incidence of anxiety is higher in COPD patients, and the incidence of postoperative complications is significantly increased [ 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 ]. The results of these studies are consistent with the findings observed in our study. Therefore, anxiety may have an impact on the occurrence of postoperative complications in patients through the pathways mentioned above. As we found in our research, pneumonia is the most common complication with the highest incidence rate. Firstly, due to the longer duration of esophageal cancer surgery, a larger amount of fluid (including colloidal fluids and blood transfusions) is administered during the operation, which increases the load on the pulmonary circulation and makes it prone to postoperative pneumonia [ 53 ]. Secondly, airway is governed by the autonomic nervous system, which provides continuous control over the smooth muscle, secretory cells, and vascular system of the airway [ 54 , 55 ]. The autonomic nervous system consists of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. The parasympathetic nervous system is innervated by the left and right vagus nerves running in the posterior mediastinum between the trachea and esophagus. In clinical practice, some inhaled drugs that alter the activity of autonomic nervous system receptors, including anticholinergic agents and beta-adrenergic agonists, are the main medications for treating COPD. Under normal circumstances, the vagus nerve prevents lung overinflation by participating in the cough reflex and Hering-Breuer reflex [ 56 ]. At the same time, the pulmonary C-fibers (PCFs) in the vagus nerve play a crucial role in sensing and responding to lung infections and inflammatory cytokines [ 57 ]. The vagus nerve is a major component of the parasympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system. Anxiety can cause widespread activation of the sympathetic nervous system [ 58 ]. Therefore, under the comprehensive impact of the above mechanisms, it is possible to significantly increase the incidence of pneumonia Our research has found that cardiac arrhythmia is another postoperative complication that exists differently due to anxiety. This is consistent with previous studies that have found anxiety to be an independent risk factor for cardiac arrhythmia [ 59 ]. Pyloric obstruction is a common postoperative complication in the digestive tract, with one cause being surgical operation [ 60 ]. On the other hand, weakened vagal nerve activity in anxious patients may also be a possible cause of postoperative pyloric obstruction [ 61 ].

As far as we know, this is currently the largest study on the relationship between emotional status and postoperative complications in esophageal cancer patients with COPD. It is also the first to confirm that anxiety increases the incidence of postoperative complications in this patient population. This study highlights the need for clinical doctors to pay more attention to anxiety as a commonly overlooked preoperative emotional status that may require more intervention.

Limitations

However, there are some limitations to this study. Firstly, it lacks sociodemographic data on patients, such as their education level, income, and place of residence, which may also be factors affecting patient anxiety. Future studies could include this type of information. Secondly, this study is a retrospective study. Although multivariate regression can adjust for measured covariates, it cannot account for potential residual confounding effects. Finally, the study population was limited to esophageal cancer patients with COPD, and the results may not necessarily apply to other populations.

Although there are limitations as mentioned above, our research provides further support that preoperative anxiety could be associated with postoperative complications in esophageal cancer patients with co-existing COPD. Anxiety may lead to an increased incidence of postoperative complications, especially minor complications, in this population. These complications mainly include pneumonia, pyloric obstruction, and arrhythmia.

Data availability

Data are available from corresponding author upon reasonable requests.

Abbreviations

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

Clavien-Dindo classification system

Forced Vital Capacity

Forced Expiratory Volume in one second

COPD Assessment Test

Body Mass Index

Odds ratios

Confidence interval

Mullard A. Addressing cancer’s grand challenges. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2020;19(12):825–6.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Tan SM, Beck KR, Li H, Lim EC, Krishna LK. Depression and anxiety in cancer patients in a Tertiary General Hospital in Singapore. Asian J Psychiatr. 2014;8:33–7.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Derogatis LR, Morrow GR, Fetting J, et al. The prevalence of psychiatric disorders among cancer patients. JAMA. 1983;249(6):751–7.

Huang Y, Wang Y, Wang H, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(3):211–24.

Traeger L, Greer JA, Fernandez-Robles C, Temel JS, Pirl WF. Evidence-based treatment of anxiety in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(11):1197–205.

Berard RM. Depression and anxiety in oncology: the psychiatrist’s perspective. J Clin Psychiatry 2001 62 Suppl 8:58–61; discussion 2–3.

Morgan E, Soerjomataram I, Rumgay H, et al. The Global Landscape of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and esophageal adenocarcinoma incidence and mortality in 2020 and projections to 2040: new estimates from GLOBOCAN 2020. Gastroenterology. 2022;163(3):649–58e2.

Zhu J, Zhou Y, Ma S, et al. The association between anxiety and esophageal cancer: a nationwide population-based study. Psychooncology. 2021;30(3):321–30.

Obermannová R, Alsina M, Cervantes A, et al. Oesophageal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2022;33(10):992–1004.

Chan RJ, Gordon LG, Tan CJ, et al. Relationships between Financial Toxicity and Symptom Burden in Cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57(3):646–60e1.

Verdonschot R, Baijens LWJ, Vanbelle S, et al. Affective symptoms in patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia: a systematic review. J Psychosom Res. 2017;97:102–10.

Housman B, Flores R, Lee DS. Narrative review of anxiety and depression in patients with esophageal cancer: underappreciated and undertreated. J Thorac Dis. 2021;13(5):3160–70.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (2021 report). In.; 2020: https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/GOLD-REPORT-1-v1.1-25Nov20_WMV.pdf .

Ohi M, Toiyama Y, Omura Y, et al. Risk factors and measures of pulmonary complications after thoracoscopic esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Surg Today. 2019;49(2):176–86.

Chiang CL, Hu YW, Wu CH, et al. Spectrum of cancer risk among Taiwanese with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Clin Oncol. 2016;21(5):1014–20.

Hynninen KM, Breitve MH, Wiborg AB, Pallesen S, Nordhus IH. Psychological characteristics of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a review. J Psychosom Res. 2005;59(6):429–43.

Rice TW, Ishwaran H, Ferguson MK, Blackstone EH, Goldstraw P. Cancer of the Esophagus and Esophagogastric Junction: an Eighth Edition staging primer. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(1):36–42.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205–13.

Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, et al. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250(2):187–96.

Ou X, Wang Q, Li C, Zhao H, Guo L. Magnetic Resonance Imaging Based on Wavelet Algorithm in the Diagnosis and Treatment of Tibial Osteomyelitis Wound Infection. Scientific Programming 2021, 2021:2130089.

Rabe KF, Watz H. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The Lancet. 2017;389(10082):1931–40.

Article Google Scholar

Karalapillai D, Weinberg L, Peyton P, et al. Effect of intraoperative low tidal volume vs conventional tidal volume on postoperative pulmonary complications in patients undergoing major surgery: a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020;324(9):848–58.

Matthay MA, Ware LB, Zimmerman GA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(8):2731–40.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Kernan WN, Viscoli CM, Brass LM, et al. Phenylpropanolamine and the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2000;343(25):1826–32.

Feng Y, Yang Y, Fan C, et al. Pterostilbene inhibits the growth of human esophageal Cancer cells by regulating endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2016;38(3):1226–44.

Hu W, Yang Y, Fan C, et al. Clinical and pathological significance of N-Myc downstream-regulated gene 2 (NDRG2) in diverse human cancers. Apoptosis. 2016;21(6):675–82.

Li T, Yang Z, Jiang S, et al. Melatonin: does it have utility in the treatment of haematological neoplasms? Br J Pharmacol. 2018;175(16):3251–62.

Ma Z, Fan C, Yang Y, et al. Thapsigargin sensitizes human esophageal cancer to TRAIL-induced apoptosis via AMPK activation. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35196.

Sun M, Liu X, Xia L, et al. A nine-lncRNA signature predicts distant relapse-free survival of HER2-negative breast cancer patients receiving taxane and anthracycline-based neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Biochem Pharmacol. 2021;189:114285.

Yang Z, Jiang S, Lu C, et al. SOX11: friend or foe in tumor prevention and carcinogenesis? Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2019;11:1758835919853449.

Low DE, Kuppusamy MK, Alderson D, et al. Benchmarking complications Associated with Esophagectomy. Ann Surg. 2019;269(2):291–8.

Bergquist H, Ruth M, Hammerlid E. Psychiatric morbidity among patients with cancer of the esophagus or the gastro-esophageal junction: a prospective, longitudinal evaluation. Dis Esophagus. 2007;20(6):523–9.

Dempster M, McCorry NK, Brennan E, et al. Psychological distress among survivors of esophageal cancer: the role of illness cognitions and coping. Dis Esophagus. 2012;25(3):222–7.

Johanes C, Monoarfa RA, Ismail RI, Umbas R. Anxiety level of early- and late-stage prostate cancer patients. Prostate Int. 2013;1(4):177–82.

Meyer F, Fletcher K, Prigerson HG, Braun IM, Maciejewski PK. Advanced cancer as a risk for major depressive episodes. Psychooncology. 2015;24(9):1080–7.

Xie Q, Sun C, Fei Z, Yang X. Accepting Immunotherapy after Multiline Treatment failure: an exploration of the anxiety and depression in patients with Advanced Cancer Experience. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2022;16:1–9.

Kalwar SK. Comparison of human anxiety based on different cultural backgrounds. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2010;13(4):443–6.

Guerrini CJ, Schneider SC, Guzick AG, et al. Psychological distress among the U.S. General Population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:642918.

Johnston M, Carpenter L. Relationship between pre-operative anxiety and post-operative state. Psychol Med. 1980;10(2):361–7.

Reading AE. The effects of psychological preparation on pain and recovery after minor gynaecological surgery: a preliminary report. J Clin Psychol. 1982;38(3):504–12.

Pan X, Wang J, Lin Z, Dai W, Shi Z. Depression and anxiety are risk factors for Postoperative Pain-related symptoms and complications in patients undergoing primary total knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2019;34(10):2337–46.

van Goozen SH, Matthys W, Cohen-Kettenis PT, et al. Salivary cortisol and cardiovascular activity during stress in oppositional-defiant disorder boys and normal controls. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;43(7):531–9.

Poon JA, Turpyn CC, Hansen A, Jacangelo J, Chaplin TM. Adolescent substance Use & psychopathology: interactive effects of Cortisol reactivity and emotion regulation. Cognit Ther Res. 2016;40(3):368–80.

Ozbay F, Fitterling H, Charney D, Southwick S. Social support and resilience to stress across the life span: a neurobiologic framework. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008;10(4):304–10.

Pössel P, Ahrens S, Hautzinger M. Influence of cosmetics on emotional, autonomous, endocrinological, and immune reactions. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2005;27(6):343–9.

Maranets I, Kain ZN. Preoperative anxiety and intraoperative anesthetic requirements. Anesth Analg. 1999;89(6):1346–51.

Liang Z, Gu Y, Duan X, et al. Design of multichannel functional near-infrared spectroscopy system with application to propofol and sevoflurane anesthesia monitoring. Neurophotonics. 2016;3(4):045001.

Wagena EJ, van Amelsvoort LG, Kant I, Wouters EF. Chronic bronchitis, cigarette smoking, and the subsequent onset of depression and anxiety: results from a prospective population-based cohort study. Psychosom Med. 2005;67(4):656–60.

Kim HJ, Lee J, Park YS, et al. Impact of GOLD groups of chronic pulmonary obstructive disease on surgical complications. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:281–7.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Dai J, He Y, Maneenil K, et al. Timing of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease diagnosis in lung cancer prognosis: a clinical and genomic-based study. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2021;10(3):1209–20.

Xu K, Cai W, Zeng Y, et al. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for primary lung cancer resections in patients with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2021;10(6):2603–13.

Xiao H, Zhou H, Liu K, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic nomogram for predicting post-operative pulmonary infection in gastric cancer patients following radical gastrectomy. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):14587.

Russotto V, Sabaté S, Canet J. Development of a prediction model for postoperative pneumonia: a multicentre prospective observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2019;36(2):93–104.

Ikeda T, Anisuzzaman AS, Yoshiki H, et al. Regional quantification of muscarinic acetylcholine receptors and β-adrenoceptors in human airways. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;166(6):1804–14.

Undem BJ, Potenzieri C. Autonomic neural control of intrathoracic airways. Compr Physiol. 2012;2(2):1241–67.

Belvisi MG. Overview of the innervation of the lung. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2002;2(3):211–5.

Huang Y, Zhao C, Su X. Neuroimmune regulation of lung infection and inflammation. QJM. 2019;112(7):483–7.

Roth WT, Doberenz S, Dietel A, et al. Sympathetic activation in broadly defined generalized anxiety disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;42(3):205–12.

Carnevali L, Vacondio F, Rossi S, et al. Cardioprotective effects of fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitor URB694, in a rodent model of trait anxiety. Sci Rep. 2015;5:18218.

Urschel JD, Blewett CJ, Young JE, Miller JD, Bennett WF. Pyloric drainage (pyloroplasty) or no drainage in gastric reconstruction after esophagectomy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Dig Surg. 2002;19(3):160–4.

Greaves-Lord K, Ferdinand RF, Sondeijker FE, et al. Testing the tripartite model in young adolescents: is hyperarousal specific for anxiety and not depression? J Affect Disord. 2007;102(1–3):55–63.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thanked Home for Researcher for language editing service.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Thoracic Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Hebei North University, 12 Changqing Road, 075000, Zhangjiakou, China

Yu Rong, Yanbing Hao, Dong Wei, Yanming Li & Wansheng Chen

Department of Anesthesiology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Hebei North University, 075000, Zhangjiakou, China

School of Basic Medicine, Fourth Military Medical University, 710032, Xi’an, China

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

YR and WSC conceived the study. LW collected the clinical data. YML conducted statistical analysis on the data. YR and DW drafted the manuscript. YBH and TL wrote and revised the manuscript rigorously. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Yanbing Hao or Tian Li .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The study was approved by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Hebei North University, with an ethics number of K2018075. Based on the retrospective design and the anonymous nature of the data collection, written informed consent was waived by the ethics committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Hebei North University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare no Competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Rong, Y., Hao, Y., Wei, D. et al. Association between preoperative anxiety states and postoperative complications in patients with esophageal cancer and COPD: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Cancer 24 , 606 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-11884-9

Download citation

Received : 10 June 2023

Accepted : 15 January 2024

Published : 17 May 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12885-024-11884-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Esophageal neoplasms

- Postoperative complications

- Retrospective study

ISSN: 1471-2407

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Statistics Made Easy

When to Use a Chi-Square Test (With Examples)

In statistics, there are two different types of Chi-Square tests:

1. The Chi-Square Goodness of Fit Test – Used to determine whether or not a categorical variable follows a hypothesized distribution.

2. The Chi-Square Test of Independence – Used to determine whether or not there is a significant association between two categorical variables.

Note that both of these tests are only appropriate to use when you’re working with categorical variables . These are variables that take on names or labels and can fit into categories. Examples include:

- Eye color (e.g. “blue”, “green”, “brown”)

- Gender (e.g. “male”, “female”)

- Marital status (e.g. “married”, “single”, “divorced”)

This tutorial explains when to use each test along with several examples of each.

The Chi-Square Goodness of Fit Test

You should use the Chi-Square Goodness of Fit Test whenever you would like to know if some categorical variable follows some hypothesized distribution.

Here are some examples of when you might use this test:

Example 1: Counting Customers

A shop owner wants to know if an equal number of people come into a shop each day of the week, so he counts the number of people who come in each day during a random week.

He can use a Chi-Square Goodness of Fit Test to determine if the distribution of customers follows the theoretical distribution that an equal number of customers enters the shop each weekday.

Example 2: Testing if a Die is Fair

Suppose a researcher would like to know if a die is fair. She decides to roll it 50 times and record the number of times it lands on each number.

She can use a Chi-Square Goodness of Fit Test to determine if the distribution of values follows the theoretical distribution that each value occurs the same number of times.

Example 3: Counting M&M’s

Suppose we want to know if the percentage of M&M’s that come in a bag are as follows: 20% yellow, 30% blue, 30% red, 20% other. To test this, we open a random bag of M&M’s and count how many of each color appear.

We can use a Chi-Square Goodness of Fit Test to determine if the distribution of colors is equal to the distribution we specified.

For a step-by-step example of a Chi-Square Goodness of Fit Test, check out this example in Excel.

The Chi-Square Test of Independence

You should use the Chi-Square Test of Independence when you want to determine whether or not there is a significant association between two categorical variables.

Example 1: Voting Preference & Gender

Researchers want to know if gender is associated with political party preference in a certain town so they survey 500 voters and record their gender and political party preference.

They can perform a Chi-Square Test of Independence to determine if there is a statistically significant association between voting preference and gender.

Example 2: Favorite Color & Favorite Sport

Researchers want to know if a person’s favorite color is associated with their favorite sport so they survey 100 people and ask them about their preferences for both.

They can perform a Chi-Square Test of Independence to determine if there is a statistically significant association between favorite color and favorite sport.

Example 3: Education Level & Marital Status

Researchers want to know if education level and marital status are associated so they collect data about these two variables on a simple random sample of 2,000 people.

They can perform a Chi-Square Test of Independence to determine if there is a statistically significant association between education level and marital status.

For a step-by-step example of a Chi-Square Test of Independence, check out this example in Excel.

Additional Resources

The following calculators allow you to perform both types of Chi-Square tests for free online:

Chi-Square Goodness of Fit Test Calculator Chi-Square Test of Independence Calculator

Featured Posts

Hey there. My name is Zach Bobbitt. I have a Masters of Science degree in Applied Statistics and I’ve worked on machine learning algorithms for professional businesses in both healthcare and retail. I’m passionate about statistics, machine learning, and data visualization and I created Statology to be a resource for both students and teachers alike. My goal with this site is to help you learn statistics through using simple terms, plenty of real-world examples, and helpful illustrations.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Join the Statology Community

Sign up to receive Statology's exclusive study resource: 100 practice problems with step-by-step solutions. Plus, get our latest insights, tutorials, and data analysis tips straight to your inbox!

By subscribing you accept Statology's Privacy Policy.

- Open access

- Published: 14 May 2024

Pregnancy-related complications in patients with endometriosis in different stages

- Khadijeh Shadjoo 1 ,

- Atefeh Gorgin 2 ,

- Narges Maleki 2 ,

- Arash Mohazzab 3 ,

- Maryam Armand 2 ,

- Atiyeh Hadavandkhani 2 ,

- Zahra Sehat 2 &

- Aynaz Foroughi Eghbal 4

Contraception and Reproductive Medicine volume 9 , Article number: 23 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

109 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Endometriosis is one of the most common and costly diseases among women. This study was carried out to investigate pregnancy outcomes in women with endometriosis because of the high prevalence of endometriosis in reproductive ages and its effect on pregnancy-related complications outcomes.

This was a cross-sectional study performed on 379 pregnant women with endometriosis who were referred to the endometriosis clinic of the Avicenna Infertility Treatment Center from 2014 to 2020. Maternal and neonatal outcomes were assessed for the endometriosis group and healthy mothers. The group with endometriosis was further divided into two groups: those who underwent surgery and those who either received medication alone or were left untreated before becoming pregnant. The analysis of the data was done using SPSS 18.

The mean age of the patients was 33.65 ± 7.9 years. The frequency of endometriosis stage ( P = 0.622) and surgery ( P = 0.400) in different age groups were not statistically significant. The highest rates of RIF and infertility were in stages 3 ( N = 46, 17.2%) ( P = 0.067), and 4 ( N = 129, 48.3%) ( P = 0.073), respectively, but these differences were not statistically different, and the highest rate of pregnancy with ART/spontaneous pregnancy was observed in stage 4 without significant differences ( P = 0.259). Besides, the frequency of clinical/ectopic pregnancy and cesarean section was not statistically different across stages ( P > 0.05). There is no significant relationship between endometriosis surgery and infertility ( P = 0.089) and RIF ( P = 0.232). Most of the people who had endometriosis surgery with assisted reproductive methods got pregnant, and this relationship was statistically significant ( P = 0.002) in which 77.1% ( N = 138) of ART and 63% ( N = 264) of spontaneous pregnancies were reported in patients with endometriosis surgery. The rate of live births (59.4%) was not statistically significant for different endometriosis stages ( P = 0.638). There was no stillbirth or neonatal death in this study. All cases with preeclampsia ( N = 5) were reported in stage 4. 66.7% ( N = 8) of the preterm labor was in stage 4 and 33.3% ( N = 4) was in stage 3 ( P = 0.005). Antepartum bleeding, antepartum hospital admission, preterm labor, gestational diabetes, gestational hypertension, abortion, placental complications and NICU admission were higher in stage 4, but this difference had no statistical difference.

Endometriosis is significantly correlated with infertility. The highest rates of RIF and infertility are observed in stages 3 and 4 of endometriosis. The rate of pregnancy with ART/spontaneous pregnancy, preterm labor, preeclampsia and pregnancy-related complications is higher in stage 4. Most of the people who had endometriosis surgery with assisted reproductive methods got significantly pregnant. Clinical/ectopic pregnancy, cesarean sections, and live birth were not affected by the endometriosis stages.

Introduction

The presence of endometrial-like glandular tissue, stroma, or endometrial tissue outside the uterine cavity is known as endometriosis, a chronic gynecological disease that affects 30 to 50% of infertile women [ 1 ]. Endometriosis commonly affects various parts of the female reproductive system, including the pelvic area, ovaries, posterior cul-de-sac, uterine ligaments, pelvic peritoneum, rectovaginal septum, cervix, vulva, vagina, as well as the intestines and urinary system. Endometriosis can cause symptoms like infertility, dysmenorrhea, and chronic pelvic inflammatory disease, which can worsen pain, dyspareunia, and painful bowel movements, ultimately lowering the quality of life for the affected woman [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ]. Laparoscopic surgery is both the standard surgical procedure and the best treatment for endometriosis [ 14 ]. However, endometriosis remains a problematic issue due to its negative impact on ovarian reserve and the recurrence rate of 40–50% after 5 years of surgery [ 15 , 16 ]. Numerous studies have shown the negative effects of endometriosis on pregnancy, including the increase in preterm labor, placental abruption and cesarean delivery, preeclampsia, placental problems and postpartum hemorrhage, premature rupture of membranes (PROM), preterm birth, small for gestational age (SGA), NICU admission, neonatal mortality and morbidity, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (HDP) with low birth weight (LBW) [ 2 , 5 , 6 , 17 ]. Since the effects of endometriosis on the course of pregnancy are still controversial, this work aimed to first identify the negative effects of endometriosis on pregnancy and then determine whether laparoscopic surgery or other drug interventions before pregnancy were beneficial.

Materials and methods

This cross-sectional study was carried out on 379 pregnant women with a history of endometriosis and pregnancy who were referred to the endometriosis clinic of the Avicenna Infertility Treatment Center between January 2014 and January 2020. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Avicenna Infertility Treatment Center (IR.ACECR.AVICENNA.REC.1398.031) in accordance with the tents of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the patient’s oral and written consent was obtained to ensure that they participated in the study voluntarily. Specific means of identifying endometriosis were approved after laparoscopic surgery with pathologic confirmation, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), ultrasound imaging, and clinically confirmed presence of symptoms. Exclusion criteria were less than 22 weeks of gestation at the time of delivery, fetal malformations, and incomplete medical files. Maternal and neonatal outcomes were assessed for the endometriosis group and healthy mothers. The group with endometriosis was further divided into two groups: those who underwent surgery and those who either received medication alone or were left untreated before becoming pregnant. A history of laparoscopic surgery or other surgeries and hormonal therapies (oral contraceptive pills, progestin, and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists) were obtained from the patient’s medical files. Maternal characteristics in this study included maternal age, parity, pre-pregnancy weight and BMI, pre-pregnancy blood pressure, chronic hypertension, diabetes mellitus (DM), cholestasis, and assisted reproductive technology (ART). Outcomes evaluated included gestational age, ectopic pregnancy, clinical pregnancy, mode of delivery, antepartum hemorrhage, antepartum hospitalization, preterm labor (< 37 weeks of gestation), labor dystocia, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), gestational hypertension, gestational cholestasis, placental abruption and placenta previa, PROM, and abortion. Neonatal characteristics included birth weight, height, SGA, stillbirth, neonatal death, and NICU admission.

Statistical analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS 18. Normality was checked using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Continuous variables with a normal distribution were summarized as mean and standard deviation and compared between the two groups using an independent t-test. Categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentage to be compared between the two groups using either the Fisher’s exact test or the chi-square ( x 2 ) test. The significance level was defined as p < 0.05.