- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Leadership →

- 01 May 2024

- What Do You Think?

Have You Had Enough?

James Heskett has been asking readers, “What do you think?” for 24 years on a wide variety of management topics. In this farewell column, Heskett reflects on the changing leadership landscape and thanks his readers for consistently weighing in over the years. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 26 Apr 2024

Deion Sanders' Prime Lessons for Leading a Team to Victory

The former star athlete known for flash uses unglamorous command-and-control methods to get results as a college football coach. Business leaders can learn 10 key lessons from the way 'Coach Prime' builds a culture of respect and discipline without micromanaging, says Hise Gibson.

- 26 Mar 2024

- Cold Call Podcast

How Do Great Leaders Overcome Adversity?

In the spring of 2021, Raymond Jefferson (MBA 2000) applied for a job in President Joseph Biden’s administration. Ten years earlier, false allegations were used to force him to resign from his prior US government position as assistant secretary of labor for veterans’ employment and training in the Department of Labor. Two employees had accused him of ethical violations in hiring and procurement decisions, including pressuring subordinates into extending contracts to his alleged personal associates. The Deputy Secretary of Labor gave Jefferson four hours to resign or be terminated. Jefferson filed a federal lawsuit against the US government to clear his name, which he pursued for eight years at the expense of his entire life savings. Why, after such a traumatic and debilitating experience, would Jefferson want to pursue a career in government again? Harvard Business School Senior Lecturer Anthony Mayo explores Jefferson’s personal and professional journey from upstate New York to West Point to the Obama administration, how he faced adversity at several junctures in his life, and how resilience and vulnerability shaped his leadership style in the case, "Raymond Jefferson: Trial by Fire."

- 24 Jan 2024

Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago

Aggressive cost cutting and rocky leadership changes have eroded the culture at Boeing, a company once admired for its engineering rigor, says Bill George. What will it take to repair the reputational damage wrought by years of crises involving its 737 MAX?

- 02 Jan 2024

Do Boomerang CEOs Get a Bad Rap?

Several companies have brought back formerly successful CEOs in hopes of breathing new life into their organizations—with mixed results. But are we even measuring the boomerang CEOs' performance properly? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- Research & Ideas

10 Trends to Watch in 2024

Employees may seek new approaches to balance, even as leaders consider whether to bring more teams back to offices or make hybrid work even more flexible. These are just a few trends that Harvard Business School faculty members will be following during a year when staffing, climate, and inclusion will likely remain top of mind.

- 12 Dec 2023

Can Sustainability Drive Innovation at Ferrari?

When Ferrari, the Italian luxury sports car manufacturer, committed to achieving carbon neutrality and to electrifying a large part of its car fleet, investors and employees applauded the new strategy. But among the company’s suppliers, the reaction was mixed. Many were nervous about how this shift would affect their bottom lines. Professor Raffaella Sadun and Ferrari CEO Benedetto Vigna discuss how Ferrari collaborated with suppliers to work toward achieving the company’s goal. They also explore how sustainability can be a catalyst for innovation in the case, “Ferrari: Shifting to Carbon Neutrality.” This episode was recorded live December 4, 2023 in front of a remote studio audience in the Live Online Classroom at Harvard Business School.

- 05 Dec 2023

Lessons in Decision-Making: Confident People Aren't Always Correct (Except When They Are)

A study of 70,000 decisions by Thomas Graeber and Benjamin Enke finds that self-assurance doesn't necessarily reflect skill. Shrewd decision-making often comes down to how well a person understands the limits of their knowledge. How can managers identify and elevate their best decision-makers?

- 21 Nov 2023

The Beauty Industry: Products for a Healthy Glow or a Compact for Harm?

Many cosmetics and skincare companies present an image of social consciousness and transformative potential, while profiting from insecurity and excluding broad swaths of people. Geoffrey Jones examines the unsightly reality of the beauty industry.

- 14 Nov 2023

Do We Underestimate the Importance of Generosity in Leadership?

Management experts applaud leaders who are, among other things, determined, humble, and frugal, but rarely consider whether they are generous. However, executives who share their time, talent, and ideas often give rise to legendary organizations. Does generosity merit further consideration? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 24 Oct 2023

From P.T. Barnum to Mary Kay: Lessons From 5 Leaders Who Changed the World

What do Steve Jobs and Sarah Breedlove have in common? Through a series of case studies, Robert Simons explores the unique qualities of visionary leaders and what today's managers can learn from their journeys.

- 06 Oct 2023

Yes, You Can Radically Change Your Organization in One Week

Skip the committees and the multi-year roadmap. With the right conditions, leaders can confront even complex organizational problems in one week. Frances Frei and Anne Morriss explain how in their book Move Fast and Fix Things.

- 26 Sep 2023

The PGA Tour and LIV Golf Merger: Competition vs. Cooperation

On June 9, 2022, the first LIV Golf event teed off outside of London. The new tour offered players larger prizes, more flexibility, and ambitions to attract new fans to the sport. Immediately following the official start of that tournament, the PGA Tour announced that all 17 PGA Tour players participating in the LIV Golf event were suspended and ineligible to compete in PGA Tour events. Tensions between the two golf entities continued to rise, as more players “defected” to LIV. Eventually LIV Golf filed an antitrust lawsuit accusing the PGA Tour of anticompetitive practices, and the Department of Justice launched an investigation. Then, in a dramatic turn of events, LIV Golf and the PGA Tour announced that they were merging. Harvard Business School assistant professor Alexander MacKay discusses the competitive, antitrust, and regulatory issues at stake and whether or not the PGA Tour took the right actions in response to LIV Golf’s entry in his case, “LIV Golf.”

- 01 Aug 2023

As Leaders, Why Do We Continue to Reward A, While Hoping for B?

Companies often encourage the bad behavior that executives publicly rebuke—usually in pursuit of short-term performance. What keeps leaders from truly aligning incentives and goals? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 05 Jul 2023

What Kind of Leader Are You? How Three Action Orientations Can Help You Meet the Moment

Executives who confront new challenges with old formulas often fail. The best leaders tailor their approach, recalibrating their "action orientation" to address the problem at hand, says Ryan Raffaelli. He details three action orientations and how leaders can harness them.

How Are Middle Managers Falling Down Most Often on Employee Inclusion?

Companies are struggling to retain employees from underrepresented groups, many of whom don't feel heard in the workplace. What do managers need to do to build truly inclusive teams? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 14 Jun 2023

Every Company Should Have These Leaders—or Develop Them if They Don't

Companies need T-shaped leaders, those who can share knowledge across the organization while focusing on their business units, but they should be a mix of visionaries and tacticians. Hise Gibson breaks down the nuances of each leader and how companies can cultivate this talent among their ranks.

Four Steps to Building the Psychological Safety That High-Performing Teams Need

Struggling to spark strategic risk-taking and creative thinking? In the post-pandemic workplace, teams need psychological safety more than ever, and a new analysis by Amy Edmondson highlights the best ways to nurture it.

- 31 May 2023

From Prison Cell to Nike’s C-Suite: The Journey of Larry Miller

VIDEO: Before leading one of the world’s largest brands, Nike executive Larry Miller served time in prison for murder. In this interview, Miller shares how education helped him escape a life of crime and why employers should give the formerly incarcerated a second chance. Inspired by a Harvard Business School case study.

- 23 May 2023

The Entrepreneurial Journey of China’s First Private Mental Health Hospital

The city of Wenzhou in southeastern China is home to the country’s largest privately owned mental health hospital group, the Wenzhou Kangning Hospital Co, Ltd. It’s an example of the extraordinary entrepreneurship happening in China’s healthcare space. But after its successful initial public offering (IPO), how will the hospital grow in the future? Harvard Professor of China Studies William C. Kirby highlights the challenges of China’s mental health sector and the means company founder Guan Weili employed to address them in his case, Wenzhou Kangning Hospital: Changing Mental Healthcare in China.

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW article

The role of leadership in a digitalized world: a review.

- 1 Department of Management, Ca' Foscari University, Venice, Italy

- 2 Department of Business and Management, LUISS Guido Carli University, Rome, Italy

Digital technology has changed organizations in an irreversible way. Like the movable type printing accelerated the evolution of our history, digitalization is shaping organizations, work environment and processes, creating new challenges leaders have to face. Social science scholars have been trying to understand this multifaceted phenomenon, however, findings have accumulated in a fragmented and dispersed fashion across different disciplines, and do not seem to converge within a clear picture. To overcome this shortcoming in the literature and foster clarity and alignment in the academic debate, this paper provides a comprehensive analysis of the contribution of studies on leadership and digitalization, identifying patterns of thought and findings across various social science disciplines, such as management and psychology. It clarifies key definitions and ideas, highlighting the main theories and findings drawn by scholars. Further, it identifies categories that group papers according to the macro level of analysis (e-leadership and organization, digital tools, ethical issues, and social movements), and micro level of analysis (the role of C-level managers, leader's skills in the digital age, practices for leading virtual teams). Main findings show leaders are key actors in the development of a digital culture: they need to create relationships with multiple and scattered stakeholders, and focus on enabling collaborative processes in complex settings, while attending to pressing ethical concerns. With this research, we contribute to advance theoretically the debate about digital transformation and leadership, offering an extensive and systematic review, and identifying key future research opportunities to advance knowledge in this field.

Introduction

The findings of the latest Eurobarometer survey show the majority of respondents think digitalization has a positive impact on the economy (75 percent), quality of life (67 percent), and society (64 percent) ( European Commission, 2017 ). Indeed, people's daily lives and businesses have been highly transformed by digital technologies in the last years. Digitalization allowed to connect more than 8 billion devices worldwide ( World Economic Forum, 2018 ), modified information value and management, and started to change the nature of organizations, their boundaries, work processes, and relationships ( Davenport and Harris, 2007 ; Lorenz et al., 2015 ; Vidgen et al., 2017 ).

Digital transformation refers to the adoption of a portfolio of technologies that, at varying degrees, have been employed by the majority of firms: Internet (IoT), digital platforms, social media, Artificial Intelligence (AI), Machine Learning (ML), and Big Data ( Harvard Business Review Analytic Services, 2017 ). These tools and instruments are “rapidly becoming as infrastructural as electricity” ( Cascio and Montealegre, 2016 , p. 350). At macro levels, the shift toward different technologies is setting the agenda for new mechanisms of competition, industry structures, work systems, and relations to emerge. At the micro level, the digitalization has impacted on business dynamics, processes, routines, and skills ( Cascio and Montealegre, 2016 ).

Across different sectors and regardless of organization size, companies are converting their workplaces into digital workplaces. As observed by Haddud and McAllen (2018) , many jobs now involve extensive use of technology, and require the ability to exploit it at a fast pace. Yet, digitalization is being perceived both as a global job destroyer and creator, driving a profound transformation of job requirements. In result, leaders need to invest in upskilling employees, in an effort to support and motivate them in the face of steep learning curves and highly cognitively demanding challenges. Moreover, increased connectivity and information sharing is contributing to breaking hierarchies, functions and organizational boundaries, ultimately leading to the morphing of task-based into more project-based activities, wherein employees are required to directly participate in the creation of new added value. As such, the leadership role has become vital to capture the real value of digitalization, notably by managing and retaining talent via better reaching for, connecting and engaging with employees ( Harvard Business Review Analytic Services, 2017 ; World Economic Forum, 2018 ). However, leaders need to be held accountable for addressing new ethical concerns arising from the dark side of digital transformation. For instance, regarding the exploitation of digitalization processes to inflict information overload onto employees, or to further blur the lines between one's work and personal life.

In the last few decades, leadership scholars have been trying to monitor the effects of digitalization processes. Part of the academic debate has been focused on the role of leaders' ability to integrate the digital transformation into their companies and, at the same time, inspire employees to embrace the change, which is often perceived as a threat to the current status quo ( Gardner et al., 2010 ; Kirkland, 2014 ). To bring clarity to this debate, the construct of e-leader has been introduced to describe a new profile of leaders who constantly interact with technology ( Avolio et al., 2000 ; see also Avolio et al., 2014 for a review). Accordingly, e-leadership is defined as a “social influence process mediated by Advanced Information Technology (AIT) to produce a change in attitudes, feelings, thinking, behavior, and/or performance with individuals, groups, and/or organizations” ( Avolio et al., 2000 , p. 617).

Despite the increasing interest in discussing the relationship between digital technology and leadership, contributions have accumulated in a fragmented fashion across various disciplines. This fragmentation has made scholars struggle “to detect larger patterns of change resulting from the digital transformation” ( Schwarzmüller et al., 2018 , p. 114). It also suggests that scholars have relied on multiple theoretical models to explain the phenomenon. Indeed, if, on one hand, it is clear that organizations are changing due to technological improvements, on the other hand, the way in which the transformation is occurring remains under debate. Furthermore, due to the fast-changing development and implementation of digital technology, there is a need to continuously update and consider the latest contributions to the topic.

This article addresses the aforementioned issues by offering a systematization of the literature on digitalization and leadership that has been accumulating across different disciplines, while adopting an interdisciplinary approach and providing a systematization of articles from different fields that analyze digitalization and leadership. Specifically, the present article reviews the literature on how the advent of digital technologies has changed leaders and leadership roles. Moreover, it structures and summarizes the literature, considering both theoretical frameworks and empirical findings, and fostering the understanding of both the content of the debate and its practical underpinnings. Lastly, reflecting on the findings of this review, we offer suggestions for future directions of research.

The present review draws on the following boundary conditions. First, we relied on a broad definition of leadership, in which the leader is understood as a person who guides a group of people, an organization, or empowers their transformational processes. Second, we excluded studies referring to market or industry leaders, in which the leader is represented by an organization. Third, we considered studies that clearly referred to a digital or technological transformation. Fourth, we did not include studies in which there was not a clear link between information technology and leadership (e.g., city leaders protecting the physical and digital infrastructures of urban economies regarding climate change). Therefore, our review was guided by the following research questions: (i) What are the main theoretical frameworks guiding the academic discussion on digital transformation and leadership? (ii) What are the main categories emerging from the contributions that address the relationship between digital transformation and leadership? And (iii) Which are the main future directions of research that scholars should consider?

This paper is structured as follows: First, it describes the methodology used; Second, it proposes a classification of findings based on theoretical frameworks and content. Finally, it describes implications of our findings for both research and practice, and proposes directions for future research.

Research Design

The aim of this paper is to investigate how the debate on digital transformation and leadership has evolved in recent years, to identify key theories and findings, and to propose potential future directions of research. To answer our research questions, we use a mixed method approach, that involves both quantitative research through standard databases and qualitative coding ( Crossan and Apaydin, 2010 ; Peteraf et al., 2013 ; Zupic and Čater, 2015 ).

Data Collection

We collected papers from the Scopus database, one of the most widely used sources of scientific literature ( Zupic and Čater, 2015 ). We also checked Web of Science and Ebsco databases in order to avoid missing articles. Because we did not find any relevant distinction between these databases regarding this topic, we chose to use Scopus only. We firstly accessed the database on September 1st, 2018.

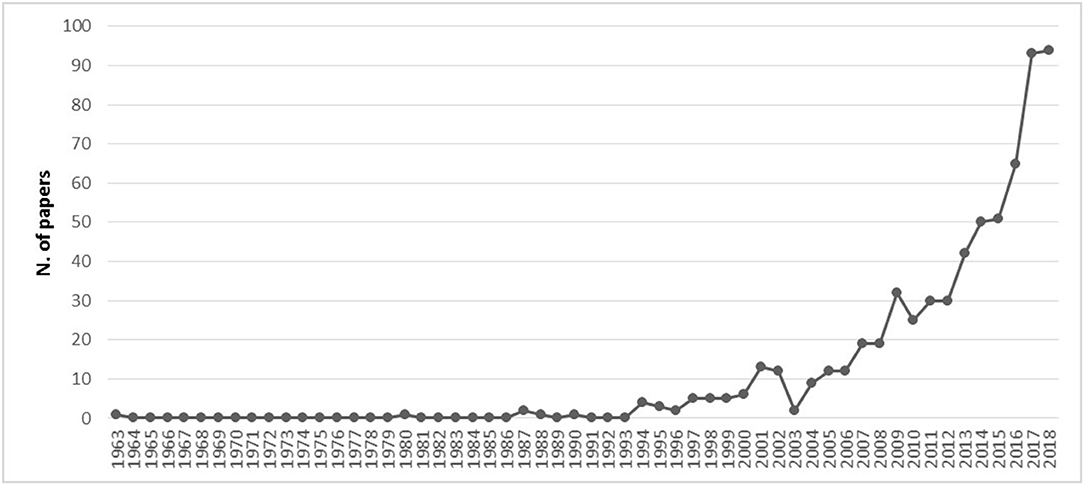

Since our research questions concerned the academic discussion on digital transformation and leadership, the scope of our search was limited to academic articles (not only from peer-reviewed journals but also from unpublished sources, such as unpublished manuscripts). Non-academic books and other publications were outside the scope of our study and were therefore excluded from our search. Our initial search was undertaken using the basic keywords: leader * AND digital * OR e-leader * . The keywords were used as a selection criterion for the topic (title, keywords, or abstract). We searched peer-reviewed papers published in English, in journals focusing on the following subject areas: Business, Management, and Accounting; Psychology; and Social Science, without any additional selection restrictions. We decided to scan articles published in other areas than Business and Management since the topic is covered by several disciplines. These criteria resulted in an initial sample of 790 articles. The following figure ( Figure 1 ) shows how the debate grew since 2000, and significantly expanded since 2015.

Figure 1 . Growth of articles on leadership and digitalization.

In order to avoid a potential publication bias ( O'Boyle et al., 2017 ), and to scan recent studies that might not have had the time to go through the entire publication process, we performed a search within conference proceedings since 2015, using the same aforementioned criteria. The initial sample comprised 113 articles.

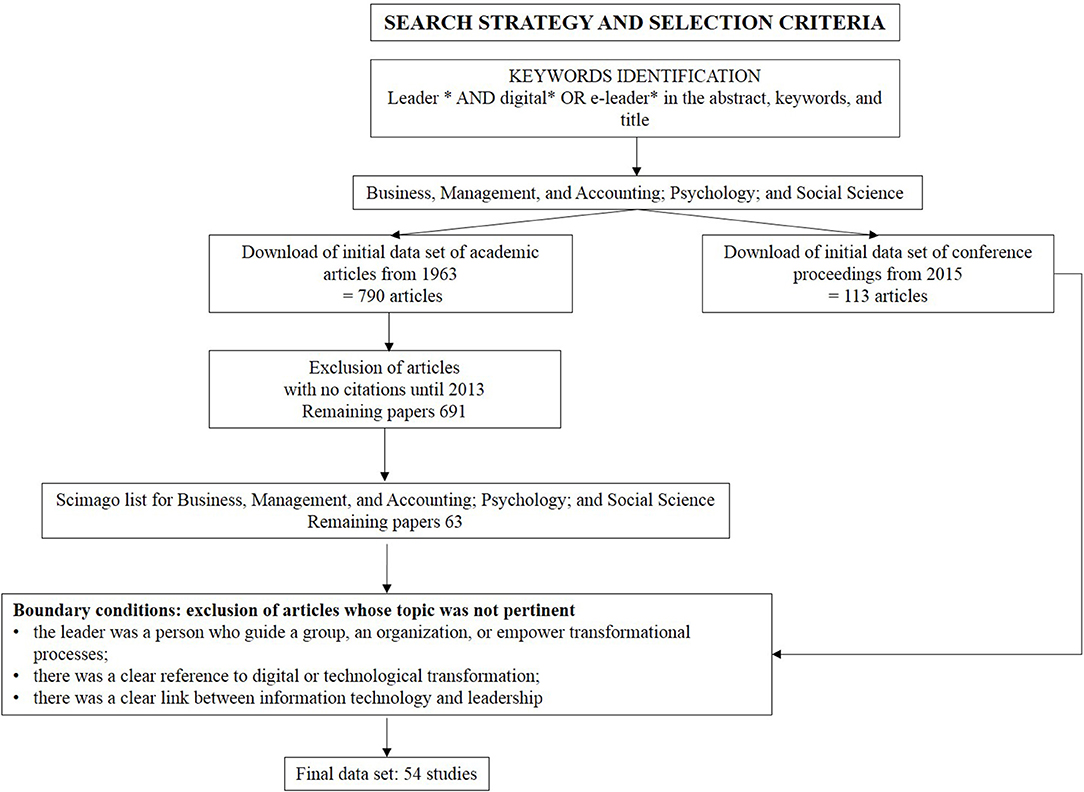

The second step within our data collection process involved a qualitative selection of articles. We first considered publications with at least one citation among those published before 2013, seen that the number of citations is a common criterion of scientific rigor and impact in academia ( Garfield, 1979 , 2004 ; Peteraf et al., 2013 ). As citation-based methods may discriminate against recent publications ( Crossan and Apaydin, 2010 ), we kept all papers published after 2013. Based on the assumption that top journals publish high quality papers, we discarded studies that were not included within the first 200 journals appearing in the Scimago list within the Management and Business, Social Science, and Psychology areas. Then, both peer-reviewed articles and conference proceedings were filtered based on the assessment of whether the abstracts were in alignment with the topic and the boundary conditions. Articles were selected based on the following criteria: (i) the leader was a person who guides a group, organization, or empowers their transformational processes; (ii) there was a clear reference to digital or technological transformation; (iii) there was a clear link between information technology and leadership. Articles that focused on either digital transformation or leadership only were excluded, as well as papers that were outside our boundary conditions, such as studies on industry leaders using digital platforms. Figure 2 summarizes the selection criteria and the boundary conditions used to scan the articles. The search criteria resulted in a final dataset of 54 studies.

Figure 2 . Search strategy and selection criteria.

Data Analysis and Qualitative Coding

To attain a “systematic, transparent and reproducible review process” ( Zupic and Čater, 2015 , p. 429), and identify research streams and seminal works, we first performed a bibliometric analysis of the initial dataset of 790 articles. In order to map the origin and evolution of the academic debate on digital transformation and leadership, a systematic coding analysis was conducted on the entire set of articles. Then, the iterative reading and discussion of the final dataset of articles highlighted the following emerging categories that guided our analysis ( Strauss and Corbin, 1998 ): (i) theoretical or empirical papers; (ii) research methodology; (iii) level of analysis (micro and macro); (iv) definition of leadership and digitalization; (v) main themes or objectives of the article; (v) main underlying theories; (vi) field of study (e.g., Management and Planning, Economics and Business, Psychology and so forth). Based on this coding scheme, the three authors independently read and coded all articles. Subsequently, they discussed their coding attribution until an agreement on the final coding of each article was reached.

Dataset Description

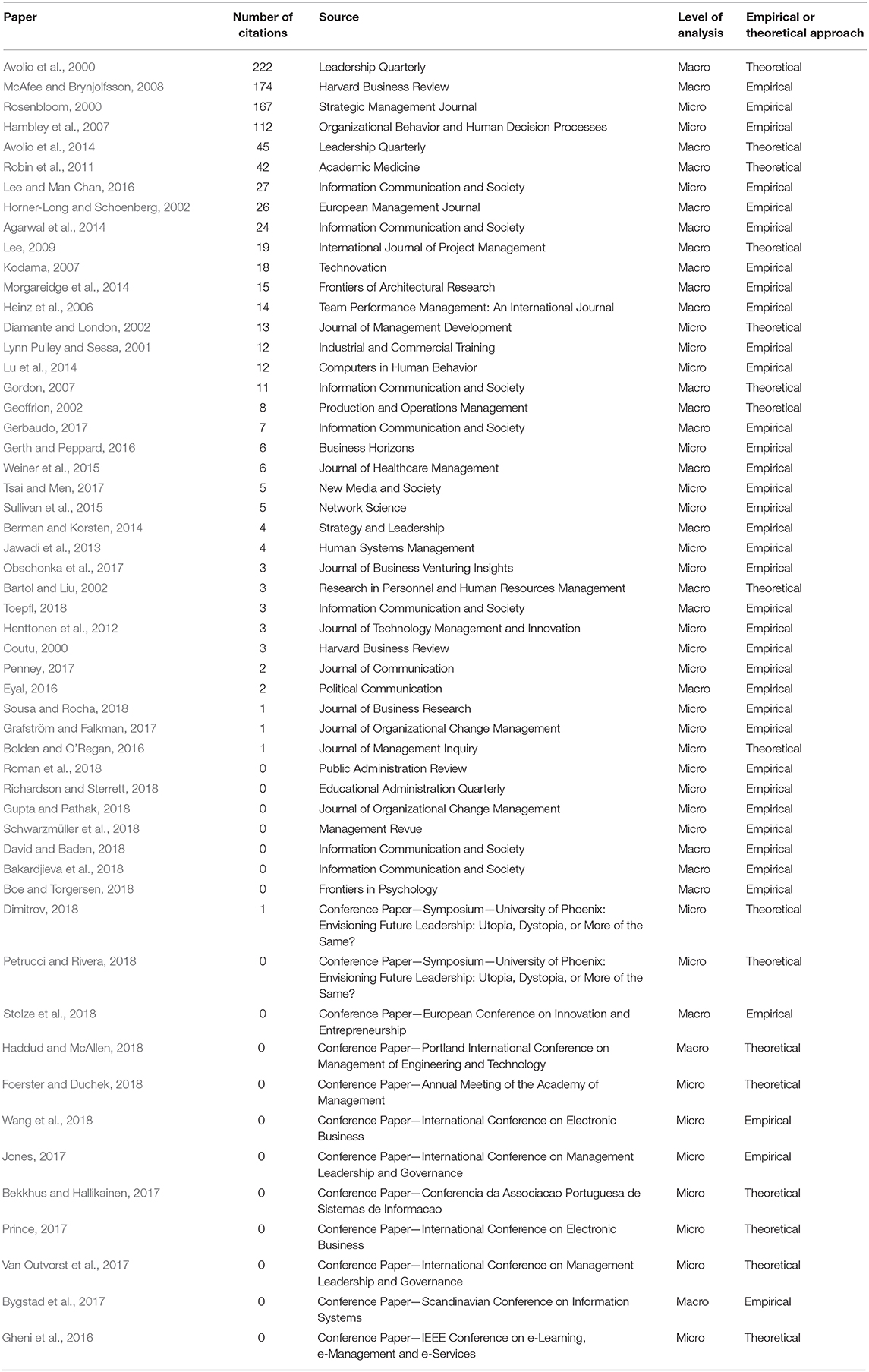

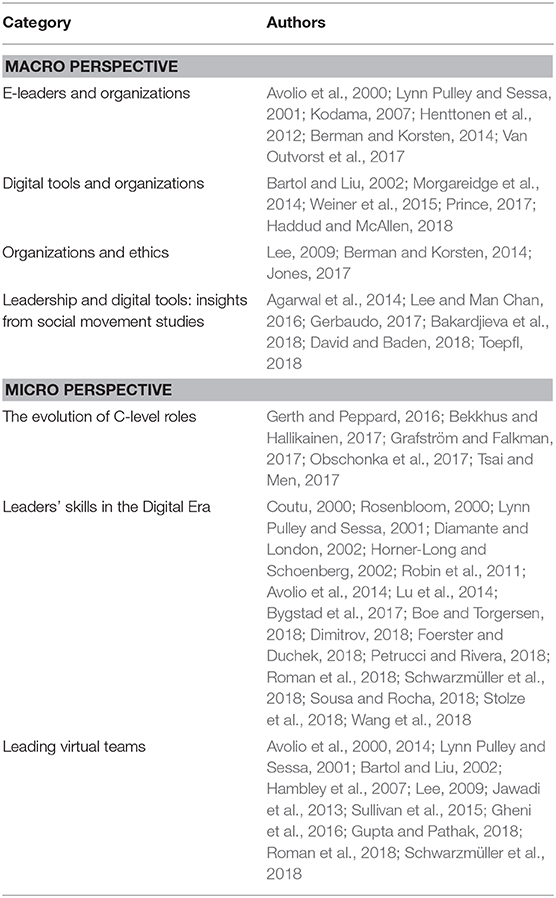

The final database comprises 54 articles, of which 42 are peer-reviewed papers published by 33 journals, while the remaining 12 papers are conference proceedings (see Table 1 ).

Table 1 . Dataset citations, source, level of analysis and empirical/theoretical approach.

Regarding the peer reviewed articles in our dataset, most of them stem from Economic, Business and Management (22 articles), and Information and Communication Sciences (10 articles). Only three studies come from the Psychology discipline. As for the sources wherein these articles are published, we count two journals that specifically address the leadership field, such as “The Leadership Quarterly” and “Strategy and Leadership”, whereas the remaining 31 other journals are spread across areas such as Economics, Business and Management, Information and Communication Sciences, Psychology, Educational, Heath and Political Sciences. The novelty of the topic and the breadth of journals in which it is published confirms that the field of digital transformation and leadership has garnered interest from several difference disciplines. Such fragmentation of the literature and the different perspectives it has enabled, justifies the need for systematization and alignment of future research.

As for the conference proceedings, half of the articles come from international and peer-reviewed conferences advancing the debate of digital transformation in business, such as the International Conference on Electronic Business, the Scandinavian Conference on Information Systems, the IEEE Conference on e-Learning, e-Management and e-Services.

Among the top five most cited articles in our sample, three come from journals that specifically relate to Human Resources: “Leadership Quarterly” and “Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes.” In these articles the authors focus on the characteristics of digital leaders in terms of roles and behaviors, stressing the idea that technology is deeply changing the way in which leaders conceive communication and cope with their followers ( Avolio et al., 2000 , 2014 ; Horner-Long and Schoenberg, 2002 ; Hambley et al., 2007 ).

As shown in Figure 1 , the early 2000s witnessed an initial interest in the topic, when pioneering work began to consider the changes that digitalization brings in the area of leadership and how the concept and practice of leadership are affected by new technologies ( Avolio et al., 2000 ; Coutu, 2000 ). However, it has been mostly over the last decade that the topic garnered seesawing attention. It is plausible to assert that the much stronger impact that technological development has had within organizations recently, and the expectation that technological evolution will be even more disruptive in the near future, has accelerated the interest on the topic. Indeed, while all peer-reviewed articles in our sample are from 2000 on, 60 percent were published after 2014. As for conference proceedings, we only considered the contributions presented after 2015 in order to understand how the debate has been developing in recent years.

Regarding the level of analysis (micro vs. macro), the majority of contributions within our sample are at the micro-level (30 articles), while 24 adopt a macro perspective. Within the latter, it is interesting to notice that a considerable number of articles do not pertain to the management field. As to the type of contribution, the majority of articles in our sample (37) are empirical studies, while only a few articles are conceptual. This imbalance reveals there is still a lack of theorization about the impact of technology on leadership. Nevertheless, in the next session we systematize the main theoretical frameworks that have been used to address this topic.

Main Theoretical Frameworks

The analysis of the theoretical content of our dataset highlighted that only a small set of studies explicitly refers to the extant theoretical frameworks describing the impact of digital transformation on leadership. Advanced information technologies theory ( Huber, 1990 ), according to which the adoption of information technologies influences changes in organization structure, information use, and decision-making processes, is used as common ground. Scholars agree on the high impact of technology in leadership behavior and identify Information Technologies (IT) developments as a driver for creating disruptive changes in businesses and in leadership roles across different organizational functions ( Bartol and Liu, 2002 ; Geoffrion, 2002 ; Weiner et al., 2015 ; Sousa and Rocha, 2018 ). These changes are so dramatic that scholars started to adopt a new terminology to characterize the e-world, e-business and e-organizations ( Horner-Long and Schoenberg, 2002 ). Recent studies have been discussing the notion of digital ubiquity ( Gerth and Peppard, 2016 ; Schwarzmüller et al., 2018 ), describing the pervasive proliferation of technology ( Roman et al., 2018 ). With this term, scholars refer to a context in which technological equipment is prevalent and constantly interacts with humans. It describes a scenario in which “computer sensors (such as radio frequency identification tags, wearable technology, smart watches) and other equipment (tablets, mobile devices) are unified with various objects, people, information, and computers as well as the physical environment” ( Cascio and Montealegre, 2016 , p. 350).

In terms of leadership theoretical frameworks, scholars seem to turn to a plethora of different theories and definitions. Horner-Long and Schoenberg (2002) contrapose two main theoretical approaches: universal theories and contingency theories. The former supports the view that leaders differ from other individuals due to a generic set of leadership traits and behaviors which can be applied to all organizations and business environments (see for example Lord et al., 1986 ; Kirkpatrick and Locke, 1991 ). The latter argues that, in order to be effective, leadership should adopt a style and behaviors that match the context (e.g., Tannenbaum and Schmidt, 1973 ; Goleman, 2000 ). The authors empirically explore leadership profile characteristics, comparing e-business leaders and leaders from traditional bricks and mortar organizations. Results do not clearly support any of the two approaches. They suggest that in both contexts most of leadership characteristics are equally valued. However, certain characteristics distinguish e-world leaders from leaders in traditional industries. While Horner-Long and Schoenberg (2002) analyze leader profile differences across industries, Richardson and Sterrett (2018) adopt a longitudinal design, exploring how digital innovations influenced the role of technology-savvy K-12 district leaders across time. They base their work on a unified model of effective leadership practices that influence learning ( Hitt and Tucker, 2016 ). Although the leadership practice model is maintained across time, the authors recognize some shifts in the way those practices are implemented.

Only Obschonka et al. (2017) specifically adopt a universal perspective, drawing from trait approach theory ( Stogdill, 1974 ). By analyzing the language used to communicate via Twitter, the authors identify the personality characteristics that distinguish the most successful managers and entrepreneurs.

Heinz et al. (2006) follow a contingency approach, emphasizing the need to take into account the context and consider situational aspects that can influence leadership and cooperation practices.

Most studies in our sample assume that the change in context due to technological advancement may influence leadership. According to Lu et al. (2014 , p. 55), it cannot be assumed that “leadership skills identified in offline context should be transferred to virtual leadership without any adjustment.”

However, some authors make this assumption tacitly (e.g., Schwarzmüller et al., 2018 ), without explicitly addressing any related theoretical framework. Bolden and O'Regan (2016 , p. 439) report that “there is no one approach to leadership,” since leadership is context specific and must to be adapted to the needs of the day. Similarly, Lu et al. (2014) maintain that effective leadership behaviors are determined by the situation in which leadership is developed.

To address the diversity of situations and contexts, Jawadi et al. (2013) overcome the limits of a pure contingency approach and embrace complexity, adopting the framework of leadership behavioral complexity theory ( Denison et al., 1995 ). In a context characterized by complex and unanticipated demands, a leader needs to develop a behavioral repertoire that allows dealing with contradictory and paradoxical situations ( Denison et al., 1995 ). As contingencies are evolving so rapidly as to be considered in a state of flux, an effective leader needs to be able to conceive and perform multiple behaviors and roles.

Avolio et al. (2000 , 2014 ), make a step forward in defining the role of context.

Similarly to Bartol and Liu (2002) , the authors adopt a structurational perspective (Adaptive Structure Theory) (AST; DeSanctis and Poole, 1994 ) as the main theoretical framework. According to their point of view, digital technologies and leadership reciprocally influence and change each other in a recursive relationship. In their perspective, not only technology influences leadership, but also leaders appropriate technology, and it is through the interaction between information technology and organizational structures that the effect of technology on individuals, groups, and organizations emerges. In this view, the context is not only shaping and shaped by leaders; it is part and parcel of the construct of e-leadership itself. Avolio et al. (2000 , 2014 ) remarkably paved the way for the conceptualization of e-leadership, which has since been adopted by many other authors to inform their studies ( Avolio et al., 2000 ; Lynn Pulley and Sessa, 2001 ; Roman et al., 2018 ).

Similarly, Orlikowski (1992) develop a Structurational Model of Technology, whereby technology influences the context in which actors perform but is also designed and socially constructed by its users ( Van Outvorst et al., 2017 ).

Looking at leaders' relationships with their teams, scholars refer to the following main theories: transactional leadership theory, transformational leadership theory ( Burns, 1978 ; Bass, 1981 , 1985 ), and leader-member exchange theory (LMX; Graen and Scandura, 1987 ). Transactional and transformational leadership are among the most influential and discussed behavioral leadership theories of the last decade ( Diaz-Saenz, 2011 ). They distinguish transformational leaders, who focus on motivating and inspiring followers to perform above expectations, from transactional leaders, who perceive the relationship with followers as an exchange process, in which follower compliance is gained through contingent reinforcement and rewards ( Bass, 1985 ). Previous studies reveal that leadership styles may influence virtual team interactions and performance (e.g., Sosik et al., 1997 ; Sosik et al., 1998 ; Kahai and Avolio, 2006 ). As such, Hambley et al. (2007) explore the effects of transactional and transformational leadership on team interactions and outcomes, comparing teams interactions across different communication media: face-to-face, desktop videoconference, or text-based chat. Likewise, Lu et al. (2014) compare virtual and offline interactions, drawing on transactional and transformational leadership theories to understand whether leadership styles of individuals playing in Massive Multiplayer Online Games (MMOGs) can be associated to their leadership status in offline contexts. However, this association is found to be significant only with offline leadership roles in voluntary organizations, not in companies. Results in Hambley et al. (2007) also show that the association between leadership style and team interaction and performance does not depend on the communication medium being used.

While transactional and transformational leadership theories adopt a behavioral perspective in which the focal point is the leader behavior with regards to the follower, leader-member exchange theory (LMX) introduces a dyadic point of view. Leader-member exchange theory focuses on the nature and quality of the relationship between leaders and their team members. The quality of this relationship, which is characterized by trust, respect, and mutual obligation, is thought to predict individual, group and organizational outcomes ( Gerstner and Day, 1997 ). Jawadi et al. (2013) use the concept of leader-member exchange as a dependent variable, exploring how multiple leadership roles influence cooperative and collaborative relationships in virtual teams. Bartol and Liu (2002) build on leader-member exchange theory to suggest policies and practices HRM professionals can use to implement IT-information sharing and positively influence employee perceptions.

The democratization of informational power gave momentum to distributed power dynamics. Moving beyond the centrality of the sole vertical leader, the shared leadership approach emphasizes the role of teams as potential source of leadership ( Pearce, 2004 ; Ensley et al., 2006 ; Pearce et al., 2009 ). Shared leadership is “a manifestation of fully developed empowerment in teams” ( Pearce, 2004 , p. 48) in which leadership behaviors that “guide, structure, or facilitate the group may be performed by more than one individual, and different individuals may perform the same leadership behaviors at different times” ( Carte et al., 2006 : p. 325).

Acknowledging the relevance of increased connectivity in the digital era, some studies underscore the importance to take into account a network perspective. Lynn Pulley and Sessa (2001) contrapose the industrial economy to the current networked economy. Bartol and Liu (2002) define networked organizations as those organizations characterized by three major types of connectivity: inter-organizational (also known as boundaryless; Nohria and Berkley, 1994 ), intra-organizational, and extra-organizational. Kodama (2007) views the organization as the integration of different types of networked strategic communities, wherein knowledge is shared and assessed. Sullivan et al. (2015) use a network representation to depict shared leadership. Gordon (2007) explores how the network is embedded in the concept of web that is currently accepted.

The Macro Perspective of Analysis: Main Categories

The studies on digitalization and leadership that adopt a macro-perspective of analysis can be classified in four different categories, according to whether they focus on: (1) The relationship between e-leaders and organizations; (2) How leaders adopt technology to solve complex organizational problems; (3) The impact of digital technologies on ethical leadership; or (4) The leader's use of digital technologies to influence social movements.

The Relationship Between E-Leaders and Organizations

The studies within our sample that take a macro or organizational-level approach are considerably less than those which investigate the micro dynamics occurring within organizations. A summary is shown in Table 2 . This imbalance is probably due to the relatively greater urgency and challenge to understand the role of leaders and leadership in guiding and implementing the digitalization process within organizations, rather than what new forms of organizations are emerging as a result of the digital transformation. As observed by a recent Harvard Business Review Analytic Services report (2017 ), leaders have increasingly become the key players in driving positive results from the investments on digital tools and technologies.

Table 2 . Main categories summary.

In the last few years, scholars have begun to adopt the construct of e-leader in order to specifically refer to those leaders who have initiated a massive process of digitalization in their organizations. Despite the call to understand how organizations and e-leaders are intertwined, few studies provide an empirical explanation of the new organizational configurations emerging from the interaction between technology and the human/social system. Berman and Korsten (2014) is one among the few. By surveying a large sample of CEOs, running companies of different sizes and across 64 countries and 18 industries, the authors showed that outperforming organizations had leaders that created open, connected and highly collaborative organizational cultures. The authors suggest future leaders should base their organizations on three pillars: (1) Assuring a highly connected and open working environment at any hierarchical levels and units in organizations; (2) Engaging customers by gathering knowledge about the whole person; and (3) Establishing more integrated and networked relationships with partners and competitors ( Berman and Korsten, 2014 ). They posit these three pillars transform the organizations at all levels. This implies organizations are becoming boundaryless, at both the internal and external levels. Further, the organizational structure is no longer a static feature, but an ongoing process ( Van Outvorst et al., 2017 ). While a shift toward an ecological perspective— one where organizations' boundaries are loose and permeable—requires higher coordination, collaboration and individual responsibility, it also enhances innovative capabilities ( Lynn Pulley and Sessa, 2001 ). According to Kodama (2007) , managers at any level can foster innovation if they go beyond the formal organization, to create real or virtual networks among internal and/or external communities of practice. These communities of practice enable a more agile response to change, promoting the free-flow of information and breaking down information silos ( Petrucci and Rivera, 2018 ), thereby empowering both managers and employees to integrate, transform and stimulate knowledge that fosters innovation. This way, information and communication technology enables the creation of shared information pools wherein diverse staff across the organization contribute to a collaborative and dynamic process of idea generation. Moreover, such co-generation of ideas and knowledge cultivates stronger relationships between disparate organizational units, further facilitating open innovation processes ( Henttonen et al., 2012 ).

In sum, by breaking the organizational boundaries within and between internal and external stakeholders, the traditional leader-centered information and decision-making process is giving way to novel processes that democratize access to information and share decision power among all parties involved.

Digital Tools and Organizations: How Technology Enhances the Optimization of Complex Organizational Environments

Although most papers adopting a macro perspective reflect on the novel structures of organizations, they tend to underestimate the effect of digital transformation on organizational processes. That is, however, not the case with Weiner et al. (2015) , who discuss how the effective achievement of operational goals relies on the fit between strategic planning and information technology, particularly in operationally complex organizations, such as hospitals. Their empirical study shows that digital tools could highly contribute in the planning and monitoring of internal processes, increasing the transparency and accountability across all levels of management, and engaging customers' trust. For instance, the intelligent use of data through sophisticated digital tools, allowed hospitals administrators to lead improvements in decision-making processes and service quality by enhancing the usage of traditional management tools, such as key performance indicators (KPIs), and storage of critical data, namely on infections and diseases. Notably, this study offers empirical evidence on the need to adopt digital technology to develop efficient internal organizational processes and guarantee high quality service to customers. In another empirical study conducted in a hospital, the authors confirmed that the use of digital tools helped leaders solve complex issues related to personnel and operational costs. Similarly to the previous study aforementioned, data were used to re-design the entire organization with the aim of optimizing the efficiency in the use of both facilities and processes ( Morgareidge et al., 2014 ).

Leaders are responsible for verifying the suitability of technological tools being adopted or implemented in relation to the organizational needs and objectives. Moreover, while we acknowledge that digital technologies hold the potential for improving the efficiency of organizational processes, we contend that they need to be internalized and integrated within employees' routine tasks in order for organizations to minimize attritions from their adoption and fully capture its benefits.

Organizations and Ethics

Ethics in leadership roles has been an issue of concern to scholars especially since the emergence of the transformational leadership paradigm ( Burns, 1978 ; Bass and Avolio, 1993 ). In general, ethical leadership is defined as “the demonstration of normatively appropriate conduct through personal actions and interpersonal relationships, and the promotion of such conduct to followers through two-way communication, reinforcement, and decision-making” ( Brown et al., 2005 , p. 120). With the advent of digital transformation and the massive use of data, scholars have begun to call into question the integrity of leaders. Indeed, the use of data and technologies exposes leaders to new dilemmas, which nature is intertwined with ethical concerns. For instance, the use of sensitive data is driving leaders' increased concerns about privacy protection and controlling mechanisms in the workplace ( Kidwell and Sprague, 2009 ). Electronic surveillance (ES) is a way to collect data about employees and their behavior, so as to improve productivity and monitor behaviors in the workplace ( Kidwell and Sprague, 2009 ). ES rules vary across countries and cultures. For instance, the US Supreme Court of Justice obliged employers to adopt ES to monitor employees in order to prevent sexual harassment ( Kidwell and Sprague, 2009 ). Notwithstanding, Europe has been more concerned with individual privacy. Notably, in 1986, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) approved a declaration on social aspects of technological change, whereby member states “were concerned that employers and unions ensure that workers' privacy be protected when technological change occurs” ( Kidwell and Sprague, 2009 , p. 199). Perhaps the boldest manifestation of this concern is the recently adopted EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which has just come into force the past May 25th, 2019.

In this scenario, leaders are required to set clear guidelines and practices that lie within national and international data security policies. In particular, they need to monitor the use of personal sensitive data, if not for the ethical concern per se , because if otherwise caught in unlawful data practices, their organizations' reputation, trustworthiness, and brand image could suffer irreparable damage (e.g., the recent scandal of Cambridge Analytica about an inappropriate use of personal data, has affected the reputation of all organizations involved) ( Gheni et al., 2016 ; Jones, 2017 ). Leaders also need to set clear expectations for employees and act as role models for all members of the organization in order to clarify what ethical behavior regarding personal sensitive data looks like. This is especially true for organizations that strongly rely on virtual communications, as these tend to stimulate more aggressive and unethical behavior, due to their lack of face-to-face interactions ( Gheni et al., 2016 ). Leaders, therefore, have a pivotal role in weeding out potential unethical behaviors from their organizations.

Finally, an emerging topic in leadership concerns the unlawful appropriation of technology from private and public organizations. Specifically, it refers to situations wherein technology is used for purposes other than those it had originally been intended ( Jones, 2017 ). For instance, improper use of technology may result in unauthorized access to data and lead to cyber security breaches ( Jones, 2017 ).

Despite the interdisciplinary relevance of ethics, the debate of ethical concerns within e-leadership seems to be currently confined to the literature on governance and information technology. Yet, there is room for more theoretical and empirical discussion about how ethics is affecting power relations, surveillance, safety perceptions in the workplace, and human resource processes.

Leadership and Digital Tools: Insights From Social Movement Studies

A complementary perspective of leadership and digitalization is provided by several recent studies that analyze social and political events, in particular grassroots movements such as the Occupy and Tea Party ( Agarwal et al., 2014 ), the Umbrella Movement in China ( Lee and Man Chan, 2016 ) and the political tensions in Russia ( Toepfl, 2018 ). These contributions share the notion of leader as someone who directs collective action and creates collective identities ( Morris and Staggenborg, 2004 ). These studies, mainly rooted in communication and political sciences, are certainly relevant to our review as they shed light on the social nature of leadership in the new digital era.

These studies focus on how social media and digital tools are disrupting traditional forms of leadership, altering the structure, norms and hierarchy of organizations, and creating new practices to manage and sustain consensus ( David and Baden, 2018 ). New forms of leadership are for instance defined as horizontal and leaderless ( Castells, 2012 ; Bennett and Segerberg, 2013 ). The horizontality defines movements and groups in which authority is dismissed, whereas leaderless points to the lack of power stratification among the participants ( Sitrin, 2006 ; Gerbaudo, 2017 ).

In a similar vein, recent studies looking at the use of digital tools by participants in social movements, observe how power struggles were changed by new information and communication technologies (ICTs): “ICTs have transformed the power dynamics of social movement politics by challenging traditional forms of [social] organizations” ( Agarwal et al., 2014 , p. 327).

The single case study of the ultra-orthodox community illustrates for instance how authoritarian leadership can be broken down by digital tools and social media ( David and Baden, 2018 ). When the leadership of a closed and conservative religious community is questioned in social media, that creates a new space to renegotiate the community's boundaries and modify its power dynamics: “the fluidity and temporality of digital media have advanced to become an influential, independent factor shaping community opinion” ( David and Baden, 2018 , p. 14). As such, the identity of a closed and inaccessible community and its leadership are challenged by both internal and external actors through the use of digital media.

The study of different digital tools is also considered a relevant subject matter to gain understanding about what tools are more efficient in organizing and mobilizing resources ( Agarwal et al., 2014 ). Technology and digital tools are not value-neutral nor value free, because they influence how people organize, coordinate, and communicate with others ( Hughes, 2004 ; Agarwal et al., 2014 ). For instance, the study on the Russian activists shows how the long-term success of the movement was a result of a centralized, formalized and stable network, wherein its leading representatives and other members were bonded together by a new digital tool ( Toepfl, 2018 ). The use of digital instruments enabled the transformation of an organization that was initially chaotic into a more structured one, as they facilitated the discussion and coordination between the leader and its followers ( Toepfl, 2018 ). This resulted in a more efficient and effective way to achieve consensus.

Taken together, these studies show how technology is far from being a neutral instrument. Rather, digital tools influence power dynamics in any type of organization (e.g., flat, bureaucratic or networked), and at any level. If on one hand, digital tools can lead to the de-structuring of extant hierarchies and challenge organizational boundaries and rules, on the other hand, they can be used as communication and coordination mechanisms that allow leaders to build structured networks from scratch and, through them, reinforce their power.

In sum, these studies stress that, despite the participatory dynamics that characterize social movements, power struggles and hierarchies are still the underlying forces that bond heterogenous groups of people together. Leaders are then the key actors in identifying objectives, orienting followers, and providing a clear identity to organizations, by means of a shared vision ( Gerbaudo, 2017 ; Bakardjieva et al., 2018 ).

The Micro Level of Analysis: Main Categories

The studies that adopt a micro-perspective to the topic of leadership and digital technology can be classified in three different categories, depending on whether they focus on: (1) The increased complexity of C-level roles; (2) The skills e-leaders need; and (3) The practices for leading virtual teams effectively.

The Evolution of C-Level Roles

The huge impact that digitalization has had in the competitive business environment, transforming markets, players, distribution channels, and relationships with customers, has made it necessary for organizations to adopt a high-level strategic view on digital transformation. New responsibilities on the selection of digital technologies that will drive an organization's ability to remain competitive in a highly digitized world, are given mainly to its CEO ( Gerth and Peppard, 2016 ). CEOs in the Digital Age assume the additional role of digital change agents and digital enablers, implying that they should recognize the opportunities offered by new technologies, and also push for their implementation. As suggested by Avolio et al. (2000) , e-leaders have a fundamental role in appropriating the right technology that is suitable to their organizations' needs, but also in transmitting a positive attitude to employees about their adopting of new technology. CEOs are required to instill a digital culture into the top management team, involving it in actively sustain a digital change inside the organization ( Gerth and Peppard, 2016 ). For this matter, a greater interaction is needed between the CEO and the Chief Information Officer (CIO), who will increasingly become a key player in the digital strategy definition and implementation, rather stay confined to an “IT-is-a-mess-now-fix-it” flavor of a role ( Gerth and Peppard, 2016 ; Bekkhus and Hallikainen, 2017 ). Bekkhus and Hallikainen (2017) acknowledge an increased ambidexterity in the role of CIOs and develop a toolbox related to their role as gatekeepers and contributors. In order to reach their goals successfully, CIOs need to have a clear picture of both the characteristics of the digital strategy and the organizational needs it is supposed to satisfy. They should also carefully evaluate the readiness of the organization in every step of the changing process in order to adopt the proper pace. To avoid IT project failures, CEOs need to facilitate the recognition of the CIO's role, as well as promote collaboration between the CIO and other top managers ( Bygstad et al., 2017 ).

As described before, digital technologies are not only used to support internal processes, but are also a way to build relationships with different actors in the external environment. Social media platforms in particular, are de facto powerful tools that C-level executives use to build communications channels with their followers ( Obschonka et al., 2017 ). In a study analyzing the rhetoric of CEOs in social media, Grafström and Falkman (2017) suggest that CEOs' willingness and ability to construct a continuative dialogue through digital channels is a powerful way not only to manage organizational crisis but also to sustain the reputation and the image of the organization, positioning the brand and communicating the organizational values. Thus, as Tsai and Men (2017) unveil, by properly using social media, CEOs, as organizational leaders and spokespersons, can build trust, satisfaction and advocacy among their followers. According to the authors, digital technologies, and social media in particular, support CEOs in becoming “Chief Engagement Officers [who develop] meaningful interpersonal interactions and relationships with today's media savvy publics” ( Tsai and Men, 2017 , p. 1859). Even if CEOs have always been considered the personification of the organization, the rising need for transparency and authenticity has led CEOs to embrace the task of visible, approachable and social leaders who actively contribute to the engagement of followers and costumers ( Tsai and Men, 2017 ).

In sum, C-level managers are faced with higher complexity of roles, related not only to new responsibilities in the digital strategy development, but also in the engagement of stakeholders across the organization's boundaries.

Leaders' Skills in the Digital Era

Defining what skills characterize leaders in the digital era has become a matter of interest in the literature. Studies analyze what are the relevant skills e-leaders should display in order to be effective. In line with the debate on universal and contingency theories, scholars ask to what extent the skills leaders need in order to lead e-businesses differ from the ones needed in traditional organizations ( Horner-Long and Schoenberg, 2002 ). Most studies are based on expert surveys that engage with digital experts, managers, CEOs and Managing Directors of e-businesses ( Lynn Pulley and Sessa, 2001 ; Horner-Long and Schoenberg, 2002 ; Schwarzmüller et al., 2018 ; Sousa and Rocha, 2018 ). A few studies also integrate expert surveys with interviews to IT specialists ( Sousa and Rocha, 2018 ) and C-level managers ( Horner-Long and Schoenberg, 2002 ).

Scholars agree that the introduction of digital tools affects the design of work, and, particularly, how people work together ( Barley, 2015 ; Schwarzmüller et al., 2018 ). For example, digitalization opens up new possibilities such as virtual teams and smart working, introduces new communication tools, increases speed and information access, influences power structures, and increases efficiency and standardization. In order to steer organizations and help them reap the benefits from such digital transformations, leaders may need to develop a variety of different skills. We present below the main skills leaders need in the digital transformation era that have been highlighted in the literature.

Communicating through digital media

Global connectivity and fast exchange of information have created a much more competitive and turbulent environment for e-businesses, which must deal with rapid and discontinuous changes in demand, competition and technology ( Horner-Long and Schoenberg, 2002 ). Scholars agree that the need for speed, flexibility, and easier access to information has facilitated the adoption of flatter and more decentralized organizational structures ( Horner-Long and Schoenberg, 2002 ). In the digital context, knowledge and information become more visible and easier to share, allowing followers to gain more autonomy ( Schwarzmüller et al., 2018 ) and to make their voices heard at all levels of the organization ( Lynn Pulley and Sessa, 2001 ). As information becomes more distributed within the organization, power tends to be decentralized. Digital transformation allows real-time involvement of followers in many decision processes, increasing their participation. Therefore, leaders are expected to adopt a more inclusive style of leading ( Schwarzmüller et al., 2018 ), asking for and taking into account followers' ideas into everyday decision making, using a two-way communication and interaction. Scholars maintain that followers' higher autonomy and participation can lead to a higher sense of responsibility for the work they are accountable for. This in turn should reduce the need for control-seeking behaviors previously exerted by leaders ( Horner-Long and Schoenberg, 2002 ; Schwarzmüller et al., 2018 ).

At the same time, inspiring and motivating employees have become pivotal skills for leaders to master ( Horner-Long and Schoenberg, 2002 ), and seem to be required to an even greater extent in order to encourage the continuous involvement and active participation of followers. Indeed, the same digital tools that provide autonomy to followers, may also drive them toward greater isolation ( Lynn Pulley and Sessa, 2001 ). According to Van Wart et al. (2017) and Roman et al. (2018) , some of the most common problems generated by the digitalization of organizations are worker alienation, weak social bonding, and poor accountability. It is therefore extremely important that leaders support and help followers in dealing with the challenges of greater autonomy and increased job demands, by adopting coaching behaviors that promote their development, provide resources, and assist them in handling tasks ( Schwarzmüller et al., 2018 ).

Similarly, the ability to create a positive organizational environment that fosters a strong sense of collaboration and unity among employees has become vital for leaders to have. Yet, e-leaders' reliance on traditional social skills, such as the abilities of active listening and understanding others' emotions and points of view, may not be enough to warrant success in creating such environments. Rather, they need to integrate these social skills with the ability to master a variety of virtual communication methods ( Roman et al., 2018 ). According to Carte et al. (2006 , p. 326), “while leadership in the more traditional face-to-face context may emerge using a variety of mechanisms, in the virtual context it likely relies largely on the communication effectiveness of the leader.”

Roman et al. (2018 , p. 5) label this skill as e-communication, and define it as “the ability to communicate via ICTs in a manner that is clear and organized, avoids errors and miscommunication, and is not excessive or detrimental to performance.” The leader needs to set the appropriate tone for the communication, while organizing it and providing clear messages. Moreover, the leader needs to master different communication tools, as their communication effectiveness depends largely on the ability to choose the right communication tool. Roman et al. (2018) provide a set of major selection criteria, which includes richness of the tool, synchronicity, speed of feedback, ease of understanding by non-experts, and reprocessing capability (ability to use the communication artifact multiple times in different venues). This ability allows to adapt the communication to the receiver preferences (as it would otherwise happen in a face-to-face interaction), so as to provide a variety of cues that enhance social bonding ( Shachaf and Hara, 2007 ; Stephens and Rains, 2011 ), convey the right message to the target audience, and better manage urgency and complexity.

High speed decision making

One way in which the introduction of technology has changed the organizational life has been the greater need for speed. Scholars agree that e-business leaders are forced to make decisions more rapidly ( Lynn Pulley and Sessa, 2001 ; Horner-Long and Schoenberg, 2002 ). This seems to suggest that decisiveness, and problem-solving abilities keep being extremely relevant for e-leaders, and may become even more prominent in the future ( Horner-Long and Schoenberg, 2002 ). According to Lynn Pulley and Sessa (2001) , never-ending urgency can create situations in which leaders needs to make decisions without having all information or without having time to think and analyze the problem properly, which may lead to falling back onto habitual responses, instead of creating novel and innovative ideas. To help navigate such situations, leaders need to be able to tolerate ambiguity, while being creative at the same time ( Horner-Long and Schoenberg, 2002 ; Schwarzmüller et al., 2018 ). If it is true that the digital world forces leaders to examine problems and provide innovative answers at a faster peace, the use of information technology also allows them to make more informed decisions. Information systems can provide enormous amounts of real-time data. For this reason, the ability to process high volumes of fast-paced incoming and outgoing data (e.g., Big data), in order to analyze it, prioritize and make sense of the relevant information for decision-making, has become and will be even more relevant in the future. Recent research points out that leaders will increasingly need to collaborate with IT managers, providing directions for data analysis and offering meaningful interpretations of results ( Harris and Mehrotra, 2014 ; Vidgen et al., 2017 ).

Managing disruptive change

The fast-paced technological evolution places high demands on organizations' ability to deal with continuously changing conditions and players. Lynn Pulley and Sessa (2001) highlight the constant need for organizations to adapt, foresee opportunities, and sometimes improvise, in order to maintain their competitiveness in the market. Under increasing pressure to innovate, leaders need to undertake an active role in identifying the need for change, as well as handling, and initiating change within their teams and organizations ( Schwarzmüller et al., 2018 ). Horner-Long and Schoenberg (2002) findings confirm that e-leaders tend to show more entrepreneurial and risk-taking characteristics than leaders in traditional contexts. However, continuous change should not disrupt the focus and mission of the organization. While promoting a flexible and innovative attitude in the organization, the leader needs to clarify a common direction. Lynn Pulley and Sessa (2001) identify the ability to inspire and share a common vision about the future of the organization as one of the challenges of e-leaders, who are frequently confronted with the need for change. While acknowledging the importance of this skill, Horner-Long and Schoenberg (2002) did not find it to characterize e-leaders any more than traditional leaders.

Managing connectivity

Scholars maintain that e-leaders also need to foster their networking abilities. Beyond the need to explore and create networks to lobby for resources and stakeholder support ( Horner-Long and Schoenberg, 2002 ) developing social interactions seems to play a key role in favoring innovation. As innovation becomes a top priority, leaders need to understand how to take advantage of networking opportunities ( Avolio et al., 2014 ). The hyper-connected environment, in which leaders operate, especially with the ubiquitous use of social media and other digital platforms, provides new networking opportunities due both to an easier access to larger groups of individuals, and the possibility to establish connections through more immediate communication. New technologies and especially the advent of social networks might have reinforced the perception that being persistently part of the network is compulsory. As reported in Horner-Long and Schoenberg (2002 , p. 616) “in the new economy some leaders do nothing but network - there is no commercial need. It is simply networking for networking's sake.” Although it is a general requirement to be able to create and maintain social relationships with various stakeholders, effective leaders differ specifically in the ability to recognize those relationships that lead to tangible benefits ( Horner-Long and Schoenberg, 2002 ).

The renaissance of technical skills

Lastly, scholars underscore the increased value of technical competencies. This represents a shift from the latest paradigm established over the past four decades, whereby leadership primarily requires emotional and social intelligence competencies that enable the leader to understand, motivate and manage his team effectively. Notwithstanding, leaders also need to understand and manage the use of various technologies. Indeed, IT knowledge and skills have become high on demand requirements to operate in a digitalized environment ( Horner-Long and Schoenberg, 2002 ). Furthermore, the mastery of current technologies must be balanced with the ability to stay current on the newest technological developments ( Roman et al., 2018 ). This emphasizes the need to adopt a life-long learning approach to developing one's digital skills.

Developing leadership skills in the digital era

To lead in the era of digital transformation requires individuals to be both people-oriented and technically minded ( Diamante and London, 2002 ). These two skills often characterize very different profiles of people that, yet, need to come together in order to implement an effective digital transformation in their organization. The case study presented by Coutu (2000) , highlights the need to establish a profitable exchange relationship between leaders of people-oriented (e.g., sales), and IT functions, in order to create a cross-functional and cross-skill contamination. Systematic knowledge dissemination from the individual to the group is highlighted as the most effective way to spread knowledge and expertise across the organization ( Boe and Torgersen, 2018 ). Coutu (2000) addresses how this cross-skill contamination can be performed, by means of implementing reverse-mentoring programs. Nonetheless, the author uncovers the problem of potential generational conflicts, whereby newer generations, who tend to be more knowledgeable and skilled in digital technologies, may gain informational power over others, generating concern and skepticism in older, change averse, individuals ( Coutu, 2000 ).

Studying modern military operational environments, Boe and Torgersen (2018) highlight the need to lead under volatile, uncertain and complex situations, characteristics they find similarly describe the context of modern e-businesses. According to the authors, leadership training needs to combine both technology and change, creating simulations of scenarios in which ambiguous information and improvisation create complex and uncertain conditions.

One way in which exposure to technology and simulations can be combined is through training in virtual spaces ( Lisk et al., 2012 ; Lu et al., 2014 ). In large community games, leaders may have to recruit, motivate, reward, and retain talented team members. They have to make quick decisions that may affect their outcomes in the long-run, for which they need to analyze the environment in order to build and keep their competitive advantage ( Avolio et al., 2014 ). Lu et al. (2014) adopt experiential learning theory ( Kolb and Kolb, 2005 ) to explain e-leadership skills development, referring to activities in which learning is performed in a virtual context. Their study attempts to empirically examine the transferability of virtual experiences into in-role job situations. Results show partial association between virtual games behaviors and hierarchical position of the participants, however, conclusions concerning the transferability of certain skills or experiences gained in virtual games may be highly affected by reverse causality. Ducheneaut and Moore (2005) , conduct a virtual ethnography to show that people participating in multiplayer role-playing games train behaviors related to networking, management and coordination in small groups. However, in a recent review on the use of games, based on digital tools or virtual realities, for training leadership skills, Lopes et al. (2013) highlight a general lack of theoretical grounding in the development and analysis of virtual games. Moreover, they find extant studies rarely show these games affect leadership skill outcomes ( Lopes et al., 2013 ). Robin et al. (2011) find that while simulations facilitate learning, they do not seem to lead to better results than traditional methods. The authors suggest simulations' main advantage lies in the possibility to enable learning in situations where it would otherwise be difficult or impossible. They thus propose the use of a combination of traditional and technology-based training to achieve the most effective learning outcomes.

Leading Virtual Teams

The introduction of digital tools has enable the organizational structure to become not only flatter and decentralized, but also dispersed. One way in which digital technology has shaped organizational life and people management has been by enabling the potential use of virtual teams. Virtual teams are defined as “interdependent groups of individuals that work across time, space, and organizational boundaries with communication links that are heavily dependent upon advanced information technologies” ( Hambley et al., 2007 , p. 1). They have become increasingly pervasive in the last years, especially in multinational organizations ( Gupta and Pathak, 2018 ).

Indeed, several benefits of virtual teams have been acknowledged in the literature. First, the use of virtual teams has allowed for a dramatic reduction of travel times and costs ( Bartol and Liu, 2002 ; Bergiel et al., 2008 ). Second, it has enabled teams to draw upon a varied array of expertise, regardless of location ( Jawadi et al., 2013 ), making it easier to access and recruit talent across the globe. Third, by facilitating the heterogeneity of team members, it has fostered creativity and innovation, due to the possibility of combining different perspectives ( Gupta and Pathak, 2018 ).

Despite its advantages, certain specificities of virtual teams' challenge the traditional way in which teams are managed and led. For instance, virtual teams are characterized by geographical and/or organizational distance. This implies that leaders cannot physically observe team members' behavior nor rely on verbal cues, facial expressions, and other non-verbal communication in order to understand the team's thoughts, feelings, moods and actions. This is considered one of the biggest barriers to developing and managing interpersonal relationships ( Jawadi et al., 2013 ). The heavy dependence on ICT may lead to communication problems, such as failing to distribute information to all team members, understand or convey the level of urgency or importance of the information, and interpret silence ( Cascio and Montealegre, 2016 ). Geographical dispersion often implies cultural diversity between team members, which may affect leaders' ability to build and maintain team spirit and trust ( Gupta and Pathak, 2018 ). According to Sullivan et al. (2015) , space may suppress leadership capacity, even in situations of shared leadership. Moreover, virtual teams are subject to time differences.

In order to overcome these challenges, virtual team leaders need to adopt specific behaviors and practices. One of the most important practices highlighted in the literature involves the setting and periodical revision of communication norms within the team ( Jawadi et al., 2013 ). Instead of focusing on behavioral norms, as in traditional teams, virtual teams require a clear definition of the norms pertaining to their use of communication tools, through witch information flows and activities are performed. Clear communication norms entail a number of advantages for virtual teams, such as: correct exchange of information, regular interaction and feedback, less ambiguity about teamwork processes, better monitoring of each member's contributions, faster detection of problems and mistakes. Moreover, because leaders play a fundamental role in enabling and mediating the communication between team members, they are able to lead them in the construction of a common language. This involves gaining a deep understanding of the underlying meaning of words and expressions used in the team. The mutual understanding of the organizational and social context in which each team member is embedded facilitates this process ( Plowman et al., 2007 ; Bjørn and Ngwenyama, 2009 ; Rafaeli et al., 2009 ).

As mentioned in the previous section, virtual team leaders also need to be able to choose the right communication tools and navigate well through their functionalities and the interactivity across various tools, if they are to avoid disruptions in communication and achieve a more vivid and open communication that favors positive team member relationships ( Jawadi et al., 2013 ). While synchronous communication is considered more appropriate to manage complex, interdependent tasks ( Hambley et al., 2007 ), asynchronous instruments may allow for team members with different backgrounds to adopt their own pace in processing others' ideas or generating new ones ( Malhotra et al., 2007 ). Moreover, asynchronous communication facilitates a continuous flow of information and the ability to work for a greater number of hours ( Gupta and Pathak, 2018 ). Furthermore, leaders need to use multiple channels with different levels of richness ( Hambley et al., 2007 ). According to Hambley et al. (2007) , “a rich medium allows for transmitting multiple verbal and nonverbal clues, using natural language, providing immediate feedback, and conveying personal feelings and emotions.” A richer tool is supposed to lead to better team cohesion. Yet, the authors found mixed results in terms of the association between constructive interaction and task performance ( Hambley et al., 2007 ).

Virtual teams often group together individuals from different educational, functional, geographical and cultural backgrounds. On one hand, such heterogeneity should promote innovative solutions, but on the other hand, it may also undermine collaboration. A virtual team leader thus needs to have good cross-cultural skills ( Schwarzmüller et al., 2018 ), to identify different cultures' characteristics and understand similarities and differences across cultures. Especially at the early stages of a virtual team's lifecycle, the leader needs to assure that the diversity of team members is understood, appreciated, and leveraged. As virtual teams do not usually have the chance to enjoy in-person informal activities typically used to share personal characteristics and abilities and foster team building, the leader needs to share and manage personal information virtually and ensure the team has a clear understanding of each team member's expertise and skills ( Malhotra et al., 2007 ). Once the diversification of skills is acknowledged, virtual teams can also benefit from a clear distribution of roles and tasks ( Jawadi et al., 2013 ). Especially if virtual teams adopt asynchronous communication tools, tasks and schedules need to be clearly defined to avoid delays due to task misallocation or overlapping.