Case Study: A Systematic Approach to Early Recognition and Treatment of Sepsis

Submitted by Madeleine Augier RN BSN

Tags: assessment Case Study emergency department guidelines mortality prevention risk factors sepsis standard of care treatment

Share Article:

Sepsis is a serious medical condition that affects 30 million people annually, with a mortality rate of approximately 16 percent worldwide (Reinhart, 2017). The severity of this disease process is not well known to the public or health care workers. Often, health care providers find sepsis difficult to diagnose with certainty. Deaths related to sepsis can be prevented with accurate assessments and timely treatment. Sepsis must be considered an immediate life-threatening condition and needs to be treated as a true emergency.

Relevance and Significance

Sepsis is defined as “the life-threatening organ dysfunction resulting from a dysregulated host response to infection” (Kleinpell, Schorr, & Balk, 2016, p. 459). Jones (2017) study of managing sepsis affirms that the presence of sepsis requires a suspected source of infection plus two or more of the following: hyperthermia (>38.1 degrees Celsius) or hypothermia (<36 degrees Celsius), tachycardia (>91 beats per minute), leukocytosis or leukopenia, altered mental status, tachypnea (>21 breaths per minute), or no urine output for 12 hours. If the infection persists, acute organ dysfunction or failure occurs from widespread inflammation, eventually leading to septic shock (Palleschi, Sirianni, O’Connor, Dunn, & Hasenau, 2013). Palleschi et al. (2013) states that during septic shock, “the cardiovascular system fails, resulting in hypotension, depriving vitals organs of an adequate supply of oxygenated blood” (p. 23). Ultimately the body can go into multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), leading to death if there is inaccurate assessment and inadequate treatment.

The purpose of this case study is to make the nurse practitioner aware of the severity sepsis, and how to accurately diagnose and treat using evidence-based data. Sepsis can affect everyone, despite his or her age or comorbidity. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has diagnosed this problem as a priority and uses sepsis management in determining payment to providers (Tedesco, Whiteman, Heuston, Swanson-Biearman, & Stephens, 2017). This medical diagnosis is unpredictable and presents a challenge to nurse practitioners worldwide. Early recognition and treatment of sepsis by the nurse practitioner is critical to decrease morbidity and mortality.

After completing this case study, the reader should be able to:

- Identify the risk factors of sepsis

- Identify the signs and symptoms of sepsis

- Identify the treatment course of sepsis

Case Presentation

A 65-year-old Asian female presented to the emergency department accompanied by her husband with a chief complaint of altered mental status. Upon assessment, the patient was lethargic, and alert and oriented to person only. The patient’s heart rate was 136, blood pressure 104/50, oral temperature 99 degrees Fahrenheit, oxygen saturation 97% on 4 liters nasal cannula, and respirations 26 per minute. The patient’s blood glucose was obtained with a result 454.

Further orders, such as labs and imaging were made by the provider to rule out potential diagnoses. A rectal temperature was obtained revealing a fever of 103.7 degrees Fahrenheit. The patient remained restless on the stretcher. After one hour in the emergency department, her heart rate spiked to 203 beats per minute, respirations became more rapid and shallow, and she became more lethargic. The patient’s altered mental status, increasing heart rate and respirations caused the providers to act rapidly.

Medical History

The patient’s husband reports that she is a type one diabetic, he denies any other medical conditions. In addition, the patient’s husband states that she has not been exposed to any sick individuals in the past few weeks. The husband reports a family history of diabetes, other wise no significant familial history. No history of smoking, drinking, or illicit drug use was to be noted.

Physical Assessment Findings

The patient appeared lethargic and confused with a Glasgow Coma Scale of 12. She appeared tachypnic, with shallow respirations, and a rate of 28 breaths per minute. Upon auscultation, breath sounds were coarse. Her abdomen was soft and non-tender, no nausea or vomiting noted. The patient appeared diaphoretic, and her legs were mottled.

Laboratory and Diagnostic Testing and Results

During the initial assessment, a complete blood count (CBC), basic metabolic panel (BMP), and lactic acid level were ordered for blood work. A STAT electrocardiogram (EKG), urinalysis, and a chest X-ray were ordered to differentiate possible diagnoses. The CBC revealed leukocytosis with a white blood cell count of 23,000 and an increased lactic acid level of 4.3. The anion gap and potassium level remained within a normal limit, ruling out the possibility of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA). The patient’s EKG showed supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). The chest X-ray revealed infiltrates to the right lung. The urinalysis was free from leukocytes or nitrites. Blood cultures were ordered to confirm their hypothesized diagnosis, septicemia.

Pharmacology

The provider initiated intravenous (IV) fluid treatment with Lactated Ringers at a bolus of 30 mL/kg. Because the patient’s heart rate was elevated, 6 mg of adenosine was ordered to combat the SVT. Additionally, broad-spectrum IV antibiotics were initiated. One gram of vancomycin and 3.375 grams of piperacillin-tazobactam were the preferred antibiotics of choice.

Final Diagnosis

Upon arrival, the providers were ruling out DKA and sepsis, given the patient’s history.

The patient’s elevated white blood cell counts, temperature, lactic acid level, heart/respiratory rate, and altered mental status were all clinical indicators of sepsis. The chest X-ray revealed a right lung infiltrate, persuading the providers to diagnose the patient with sepsis secondary to pneumonia.

Patient Management

After sepsis was ruled as the patient’s diagnosis, rapid antibiotic administration and IV fluid treatment became priority after the patient’s heart rate was controlled. A cooling blanket and a temperature sensing urinary catheter was placed to continuously monitor and control the patient’s fever. Later, the patient was transferred to a critical care unit for further treatment. Shortly after being transferred, the patient went into respiratory failure and was placed on a ventilator. After two days in the ICU, the patient remained in septic shock, and died from multisystem organ failure.

When the patient initially presented to the emergency department, accurate and rapid diagnosis of sepsis was critical in order to stabilize the patient and prevent mortality. A challenge was presented to the provider regarding a rapid diagnosis due to the patient’s history and her presenting signs and symptoms. Increased awareness and interprofessional education regarding sepsis and its’ treatment is vital to decrease mortality. Health care providers need to be competent in recognizing and accurately treating sepsis in a rapid manner.

Research shows that outcomes in sepsis are improved with timely recognition and early resuscitation (Javed et al., 2017). It is important for the provider to identify certain risk factors and symptoms to easily diagnose sepsis. A research study by Henriksen et al. (2015) proved that age, and comorbidities including psychotic disorders, immunosuppression, diabetes, and alcohol abuse served as top risk factors for sepsis.

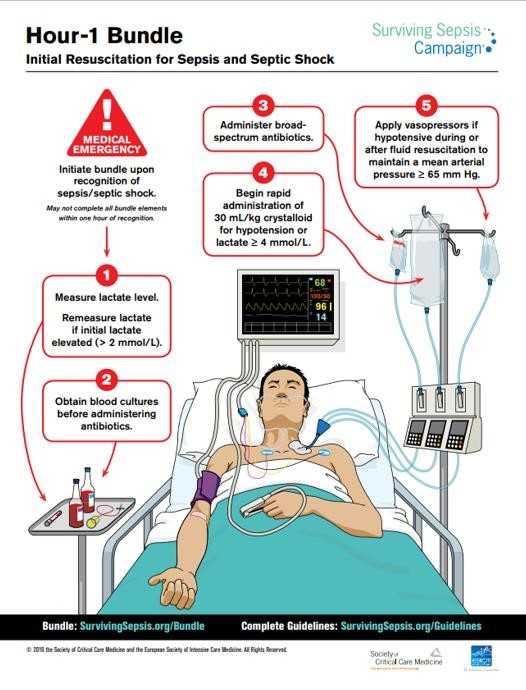

Once the diagnosis of sepsis is determined, rapid treatment must be initiated. The golden standard of treatment consists of a bundle of care that includes blood cultures, broad-spectrum antibiotic agents, and lactate measurement completed within 3 hours as described by Henriksen et al. (2015). A study by Seymour et al. (2017) showed that the more rapid administration of the bundle of care is correlated with a decreased mortality rate. In addition, The Survival of Sepsis Campaign formed a guideline to sepsis treatment; Rhodes et al. (2016) suggests giving a 30 mL/kg of IV crystalloid fluid for hypoperfusion. If hypotension persists (mean arterial pressure <65), vasopressors, preferably norepinephrine, should be initiated (Rhodes et al., 2016). Prompt recognition of sepsis and implementation of the bundle of care can help reduce avoidable deaths.

To increase awareness, interprofessional education regarding sepsis and its’ common signs and symptoms needs to be established. Evidence-based protocols should be utilized in hospital care settings that provide nurse practitioners with a guideline to follow to ensure rapid and accurate treatment is given. Increased awareness and education helps providers and other healthcare workers to properly identify and accurately treat sepsis.

The public and health care providers must become more aware and educated on the severity of sepsis. It is crucial to be able to recognize signs and symptoms of sepsis to prevent further complications such as septic shock and multi-organ failure. Increased awareness, interprofessional education, accurate assessment, and rapid treatment can help reduce incidence and mortality. Sepsis management must focus upon early goal-directed therapy (antibiotic administration, fluid resuscitation, blood cultures, lactate level) and individualized management pertaining to the patient’s history and assessment (Head & Coopersmith, 2016). Misdiagnosis and delay in emergency treatment can result in missed opportunities to save lives.

- Head, L. W., & Coopersmith, C. M. (2016). Evolution of sepsis management:from early goal-directed therapy personalized care. Advances in Surgery, 50 (1), 221-234. doi:10.1016/j.yasu.2016.04.002

- Henriksen, D. P., Pottegard, A., Laursen, C. B., Jensen, T. G., Hallas, J., Pedersen, C., & Lassen, A. T. (2015). Risk factors for hospitalization due to community-acquired sepsis-a population-based case-control study. PLOS ONE, 10 (4), 1-12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0124838

- Javed, A., Guirgis, F. W., Sterling, S. A., Puskarich, M. A., Bowman, J., Robinson, T., & Jones, A. E. (2017). Clinical predictors of early death from sepsis. Journal of Critical Care, 42 , 30-34. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2017.06.024

- Jones, J. (2017). Managing sepsis effectively with national early warning scores and screening tools. British Journal of Community Nursing, 22 (6), 278-281. doi:10.12968/bjcn.2017.22.6.278

- Kleinpell, R. M., Schorr, C. A., & Balk, R. A. (2016). The new sepsis definitions: Implications for critical care. American Journal of Critical Care, 25 (5), 457-464. doi:10.4037/ajcc2016574

- Palleschi, M. T., Sirianni, S., O'Connor, N., Dunn, D., & Hasenau, S. M. (2013). An interprofessioal process to improve early identification and treatment for sepsis. Journal for Healthcare quality, 36 (4), 23-31. doi:10.1111/jhq.12006

- Reinhart, K., Daniels, R., Kissoon, N., Machado, F. R., Schachter, R. D., & Finfer, S. (2017). Recognizing sepsis as a global health priority-A WHO resolution. The New England Journal of Medicine, 377 (5), 414-417. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1707170

- Rhodes, A., Evans, L. E., Alhazzani, W., Levy, M. M., Anotnelli, M., Ferrer, R.,...Beale, R. (2017). Surviving sepsis campaign: International guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Medicine, 43 (3), 304-377. doi:10.1007/s00134-017-4683-6

- Seymour, C. W., Gesten, F., Prescott, H. C., Friedrich, M. E., Iwashyna, T. J., Phillips, G. S.,...Levy, M. M. (2017). Time to treatment and mortality during mandated emergency care for sepsis. The New England Journal of Medicine, 376 (23), 2235-2244. doi:10.1056/NEJMoal1703058

- Tedesco, E. R., Whiteman, K., Heuston, M., Swanson-Biearman, B., & Stephens, K. (2017). Interprofessional collaboration to improve sepsis care and survival within a tertiary care emergency department. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 43 (6), 532-538. doi:10.1016/j.jen.2017.04.014

Career Opportunities

More Like This

Sepsis and Septic Shock

Sepsis and septic shock stand as life-threatening conditions that demand swift and vigilant action from healthcare providers, with nurses playing a pivotal role in their management. As frontline caregivers , nurses are essential in recognizing early signs of sepsis, initiating prompt interventions, and providing comprehensive care to improve patient outcomes.

This article aims to highlight the critical importance of nursing in battling sepsis and septic shock, shedding light on the pathophysiology, risk factors, clinical presentations, and evidence-based interventions. By fostering a comprehensive understanding of these conditions, nurses can proactively contribute to saving lives and minimizing the burden of sepsis on patients and healthcare systems.

Table of Contents

- What is Sepsis and Septic Shock?

Pathophysiology

Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, complications, assessment and diagnostic findings, medical management, nursing assessment, planning & goals, nursing interventions, discharge and home care guidelines, documentation guidelines, what is sepsis and septic shock .

One of the most common types of circulatory shock and the incidences of this disease continue to rise despite the technology.

- Sepsis is a systemic response to infection. It is manifested by two or more of the SIRS (Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome) criteria as a consequence of documented or presumed infection.

- Septic shock is associated with sepsis. It is characterized by symptoms of sepsis plus hypotension and hypoperfusion despite adequate fluid volume replacement.

The pathophysiology of sepsis involves an evolving process. The following shows the process of how sepsis works its way inside of our body.

- Microorganisms invade the body tissues and in turn, patients exhibit an immune response.

- The immune response provokes the activation of biochemical cytokines and mediators associated with an inflammatory response.

- Increased capillary permeability and vasodilation interrupt the body’s ability to provide adequate perfusion, oxygen, and nutrients to the tissues and cells.

- Proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines released during the inflammatory response and activates the coagulation system that forms clots whether or not there is bleeding .

- The imbalance of the inflammatory response and the clotting and fibrinolysis cascades are critical elements of the physiologic progression of sepsis in affected patients.

Sepsis has affected a lot of people in the United States and around the world as well. The rise in the numbers of those affected with sepsis is alarming and should be given utmost attention.

- Annually, an estimated 750, 000 people in the United States are affected by sepsis.

- By 2010, the rate may increase up to 1 million cases every year.

- Elderly patients are at most risk for developing sepsis because of decreased physiologic reserves and an aging immune system.

- Gram-positive bacteria accounts for 50% of cases of septic shock.

- It is also estimated that 20% to 30% with severe sepsis may never identify the site of infection.

There are several factors that can put the patient at risk for septic shock, and these include:

- Patients with immunosuppression have greater chances of acquiring septic shock because they have decreased immune system, making it easier for microorganisms to invade the body tissues.

- Extremes of age. Elderly people and infants are more prone to septic shock because of their weak immune system .

- Malnourishment . Malnourishment can lower the body’s defenses, making it susceptible to the invasion of pathogens.

- Chronic illness. Patients with a longstanding illness are put at risk for sepsis because the body’s immune system is already weakened by the existing pathogens.

- Invasive procedures. Invasive procedures can introduce microorganisms inside the body that could lead to sepsis.

The signs and symptoms that are associated with septic shock and sepsis include the following:

- Since the ability of the body to provide oxygen and nutrients is interrupted, the heart compensates by pumping faster.

- Hypotension occurs because of vasodilation .

- To compensate for the decreased oxygen concentration, the patient tends to breathe faster, and also to eliminate more carbon dioxide from the body.

- The inflammatory response is activated because of the invasion of pathogens.

- Decreased urine output. The body conserves water to avoid undergoing dehydration because of the inflammatory process.

- Changes in mentation . As the body slowly becomes acidotic, the patient’s mental status also deteriorates.

- Elevated lactate level. The lactate level is elevated because there is maldistribution of blood .

Before sepsis could invade a patient’s body, it is better to prevent its occurrence here are some ways to prevent sepsis and septic shock.

- Strict infection control practices. To prevent the invasion of microorganisms inside the body, infection must be put at bay through effective aseptic techniques and interventions.

- Prevent central line infections . Hospitals must implement efficient programs to prevent central line infections, which is the most dangerous route that can be involved in sepsis.

- Early debriding of wounds. Wounds should be debrided early so that necrotic tissue would be removed.

- Equipment cleanliness. Equipment used for the patient, especially the ones involved in invasive procedures, must be properly cleaned and maintained to avoid harboring harmful microorganisms that can enter the body.

Complications could happen in a patient with sepsis if it is not properly treated or not treated at all.

- Severe sepsis. Sepsis could progress to severe sepsis with symptoms of organ dysfunction, hypotension or hypoperfusion, lactic acidosis, oliguria, altered level of consciousness, coagulation disorders, and altered hepatic functions.

- Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome . This refers to the presence of altered function of one or more organs in an acutely ill patient requiring intervention and support of organs to achieve physiologic functioning required for homeostasis .

Early assessment and diagnosis of the infection must be established to avoid its progression.

- Blood culture. To identify the microorganism responsible for the disease, a blood culture must be performed.

- Liver function test. This should be performed to detect any alteration in the function of the liver.

- Blood studies. Hematologic test must also be performed to check on the perfusion of the blood.

The current treatment of septic shock and sepsis include identification and elimination of the cause of infection.

- Fluid replacement therapy . The therapy is done to correct the tissue hypoperfusion, so aggressive fluid resuscitation must be implemented.

- Nutritional therapy . Aggressive nutritional supplementation is critical in the management of septic shock because malnutrition further impairs the patient’s resistance to infection.

Nursing Management

Nurses must keep in mind that the risks of sepsis and the high mortality rate associated with sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock.

Assessment is one of the nurse ’s primary responsibilities, and this must be done precisely and diligently.

- Signs and symptoms . Assess if the patient has positive blood culture, currently receiving antibiotics , had an examination or chest x-ray , or has a suspected infected wound.

- Signs of acute organ dysfunction . Assess for presence of hypotension, tachypnea , tachycardia, decreased urine output, clotting disorder, and hepatic abnormalities.

Sepsis can affect a lot of body systems and even cause their failure, so diagnosis is an important part of the process to establish the presence of sepsis.

- Risk for deficient fluid volume related to massive vasodilation.

- Risk for decreased cardiac output related to decreased preload.

- Impaired gas exchange related to interference with oxygen delivery.

- Risk for shock related to infection.

Healthcare team members should be prepared with a care plan for the patient for a more systematic and detailed achievement of the goals.

- Patient will display hemodynamic stability.

- Patient will verbalize understanding of the disease process.

- Patient will achieve timely wound healing .

Nursing interventions pertaining to sepsis should be done timely and appropriately to maximize its effectivity.

- Infection control . All invasive procedures must be carried out with aseptic technique after careful hand hygiene .

- Collaboration . The nurse must collaborate with the other members of the healthcare team to identify the site and source of sepsis and specific organisms involved.

- Management of fever . The nurse must monitor the patient closely for shivering.

- Pharmacologic therapy . The nurse should administer prescribed IV fluids and medications including antibiotic agents and vasoactive medications.

- Monitor blood levels . The nurse must monitor antibiotic toxicity, BUN, creatinine , WBC, hemoglobin, hematocrit, platelet levels, and coagulation studies.

- Assess physiologic status . The nurse should assess the patient’s hemodynamic status, fluid intake and output , and nutritional status.

After implementation of the interventions, the nurse must evaluate their effectiveness.

- Patient displayed hemodynamic stability.

- Patient verbalized understanding of the disease process.

- Patient achieved timely wound healing.

Even after discharge, the patient must still be taught how to establish home and community care regimen.

- Prevent shock episodes . The nurse should instruct the patient and the family strategies to prevent shock episodes through identifying the factors implicated in the initial episodes.

- Instructions on assessment . The patient and the family should be taught about assessments needed to identify the complications that may occur after discharge.

- Treatment modalities . The nurse must teach the patient and the family about treatment modalities such as emergency administration of medications, IV therapy, parenteral or enteral nutrition , skin care, exercise, and ambulation .

Proper documentation must be established both for legal protection and data organization.

- Document individual risk factors.

- Document assessment findings.

- Document results of the laboratory tests and diagnostic studies.

- Document plan of care and teaching plan.

- Document client’s responses to treatment, teaching, and actions performed.

- Document modifications in the plan of care.

Posts related to Sepsis and Septic Shock:

- Risk for Infection

1 thought on “Sepsis and Septic Shock”

I’m not sure if you are aware, but under “Medical Management: Pharmacologic Therapy” Drotrecogin alfa by Eli Lily & Company (pharm company) was taken off the market on Oct of 2011. Good luck with all your endeavors and keep up the good work!

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Sepsis assessment and management in critically Ill adults: A systematic review

Contributed equally to this work with: Mohammad Rababa, Dania Bani Hamad, Audai A. Hayajneh

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Adult Health Nursing Department, Faculty of Nursing, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan

Roles Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

- Mohammad Rababa,

- Dania Bani Hamad,

- Audai A. Hayajneh

- Published: July 1, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270711

- Reader Comments

Early assessment and management of patients with sepsis can significantly reduce its high mortality rates and improve patient outcomes and quality of life.

The purposes of this review are to: (1) explore nurses’ knowledge, attitude, practice, and perceived barriers and facilitators related to early recognition and management of sepsis, (2) explore different interventions directed at nurses to improve sepsis management.

A systematic review method according to the PRISMA guidelines was used. An electronic search was conducted in March 2021 on several databases using combinations of keywords. Two researchers independently selected and screened the articles according to the eligibility criteria.

Nurses reported an adequate of knowledge in certain areas of sepsis assessment and management in critically ill adult patients. Also, nurses’ attitudes toward sepsis assessment and management were positive in general, but they reported some misconceptions regarding antibiotic use for patients with sepsis, and that sepsis was inevitable for critically ill adult patients. Furthermore, nurses reported they either were not well-prepared or confident enough to effectively recognize and promptly manage sepsis. Also, there are different kinds of nurses’ perceived barriers and facilitators related to sepsis assessment and management: nurse, patient, physician, and system-related. There are different interventions directed at nurses to help in improving nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice of sepsis assessment and management. These interventions include education sessions, simulation, decision support or screening tools for sepsis, and evidence-based treatment protocols/guidelines.

Our findings could help hospital managers in developing continuous education and staff development training programs on assessing and managing sepsis in critical care patients.

Nurses have poor to good knowledge, practices, and attitudes toward sepsis as well as report many barriers related to sepsis management in adult critically ill patients. Despite all education interventions, no study has collectively targeted critical care nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice of sepsis management.

Citation: Rababa M, Bani Hamad D, Hayajneh AA (2022) Sepsis assessment and management in critically Ill adults: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 17(7): e0270711. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270711

Editor: Paavani Atluri, Bay Area Hospital, North Bend Medical Center, UNITED STATES

Received: December 1, 2021; Accepted: June 14, 2022; Published: July 1, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Rababa et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the article and its files.

Funding: This study was funded by The deanship of research at Jordan University of Science and Technology (grant number 20200668).

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Sepsis is a global health problem that increases morbidity and mortality rates worldwide and which is one of the most common complications documented in intensive care units (ICUs) [ 1 ]. About 48.9 million cases of sepsis and 11 million sepsis-related deaths were documented in 2017 worldwide [ 2 ]. Sepsis is an emergency condition leading to several life-threatening complications, such as septic shock and multiple organ dysfunction and failure [ 3 ]. Sepsis has negative physiological, psychological, and economic consequences. Untreated sepsis can lead to septic shock; multiple organ failure, such as acute renal failure [ 4 ]; respiratory distress syndrome [ 5 ]; cardiac arrhythmia (e.g. Atrial Fibrillation) [ 6 ]; and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) [ 7 ]. Also, sepsis is associated with anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder [ 8 ]. As for the financial burden of sepsis on the healthcare system, the cost of healthcare services and supplies for ICU critical care patients with sepsis is high [ 1 ]. In 2017, the estimated annual cost of sepsis in the United States (US) was over $24 billion [ 2 ].

Previous studies have shown that among nurses, misunderstanding and misinterpretation of the early clinical manifestations of sepsis, poor knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to sepsis, and inadequate training might lead to delayed assessment and management of sepsis [ 9 – 11 ]. Moreover, the limited numbers of specific and sensitive assessment tools and standard protocols for the early identification and assessment of sepsis in critical care patients leads to delayed management, therefore increasing sepsis-related mortality rates [ 10 ].

Critical care nurses, as frontline providers of patient care, play a vital role in the decision-making process for the early identification and prompt management of sepsis [ 11 ]. Therefore, improving nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to the early identification and management of sepsis is associated with improved patient outcomes [ 12 , 13 ]. To date, there remains a wide gap between the findings of previous research and sepsis-related clinical practice in critical care units (CCUs). Furthermore, there is no evidence in the nursing literature regarding nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to the early identification and management of sepsis in adult critical care patients and the association of these factors with patient health outcomes. Therefore, summarizing and synthesizing the existing research on sepsis assessment and management among adult critical care patients is needed to guide future directions of sepsis-related clinical practice and research. Accordingly, this review aims to identify nurses’ knowledge, and attitudes, practices related to the early identification and management of sepsis in adult critical care patients.

Materials and methods

The present review used a systematic review design guided by structured questions constructed after reviewing the nursing literature relevant to sepsis assessment and management in adult critical care patients. The authors (MR, DB, AH) carefully reviewed and evaluated the selected articles and synthesized and analyzed their findings to reach a consensus. This review was guided by the following questions: (a) what are nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to sepsis assessment and management in adult critical care patients?, (b) what are the perceived facilitators of and barriers to the early identification and effective management of sepsis in adult critical care units?, and (c) what are the interventions directed at improving nurses’ sepsis assessment and management?

Eligibility criteria

The review questions were developed according to the PICOS (Participants, Interventions, Comparisons, Outcome, and Study Design) framework, as displayed in Table 1 .

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270711.t001

Inclusion criteria.

The articles were retrieved and assessed independently by two researchers (MR, DB) according to the following inclusion criteria: (1) being written in English, (2) having an abstract and reference list, (3) having been published during the past 10 years, (4) focusing on critical care nurses as a target population, (5) examining knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to the assessment and management of sepsis, and (6) having been conducted in adult critical care units.

Exclusion criteria.

Studies were excluded if they were (1) written in languages other than English, and (2) conducted in pediatric critical care units or non-ICU. Dissertations, reports, reviews, editorials, and brief communications were also excluded.

Search strategy.

An electronic search of the databases CINAHL, MEDLINE/PubMed, EBSCO, Embase, Cochrane, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar was conducted using combinations of the following keywords: critical care, intensive care, critically ill, critical illness, knowledge, awareness, perception, understanding, attitudes, opinion, beliefs, thoughts, views, practice, skills, strategies, approaches, barriers, obstacles, challenges, difficulties, issues, problems, limitations, facilitators, motivators, enablers, sepsis, septic, septic shock, and septicemia. The search terms used in this review were described in S1 File . The search was initially conducted in March 2021, and a search re-run was conducted in April 2022. The search was conducted in the selected databases from inception to 4/2022. The initial search, using the keywords independently, resulted in 1579 articles, and after using the keyword combinations, this number was reduced to 241 articles. Then, after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, the number of articles was reduced to 92. A manual search of the reference lists of the 92 articles was carried out to identify any relevant publications not identified through the search. The researcher (MR) used the function “cited by” on Google Scholar to explore these publications in more depth. The researchers (MR, DB) then screened the identified citations of these publications, applying the eligibility criteria. In case of discrepancies, the researchers (MR, DB) discussed their conflicting points of view until a consensus was reached. Then, after careful reading of the article abstracts, 61 irrelevant articles were excluded, and a total of 31 articles were included in this review. Fig 1 below shows the Preferred Reporting Items for Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist and flow chart used as a method of screening and selecting the eligible studies.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270711.g001

Data extraction

The following data were extracted from each of the selected studies: (1) the general features of the article, including the authors and publication year; (2) the characteristics of the study setting (e.g., single vs. multisite); (3) the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the target population, including mean age, and medical diagnosis (e.g., sepsis, septic shock, and SIRS); (4) the name of the sepsis protocol used, if any; (5) the characteristics of the study methodology (e.g., sample size and measurements); (7) the main significant findings of the study; and (8) the study strengths and limitations. All extracted data were summarized in an evidence-based table ( Table 2 ). Data extraction was performed by two researchers (MR, DB). An expert third researcher (AH) was consulted to reach a consensus between the two researchers throughout the process of data extraction.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270711.t002

Ethical considerations

There was no need to obtain ethical approval to conduct this systematic review since no human subjects were involved.

Quality assessment and data synthesis

A quality assessment of the selected studies was performed independently by two researchers based on the guidelines of Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt [ 14 ]. Disagreements between the two researchers (MR, DB) were identified and resolved through a detailed discussion held during a face-to-face meeting. For complicated cases, the researchers (MR, DB) requested a second opinion from a third researcher (AH). According to the guidelines of Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt [ 14 ], twelve of the studies were at level 3 in terms of quality, four studies at level 5, and nine studies at level 6.

A qualitative synthesis was performed to synthesize the findings of the reviewed studies. The following steps were applied throughout the process of data synthesis:

- The data in the selected studies were assessed, evaluated, contrasted, compared, and summarized in a table ( Table 2 ). This data included the design, purpose, sample, main findings, strengths/limitations, and level of evidence for each of the studies.

- The similarities and differences between the main findings of the selected studies were highlighted.

- The strengths and limitations of the reviewed studies were discussed.

Description of the selected studies

Most of the reviewed studies were conducted in Western countries [ 9 , 11 , 12 ], with only one study conducted in Eastern countries [ 1 ], and two in Middle-Eastern countries [ 15 , 16 ]. The detailed geographical distribution of the studies and other characteristics are described in Table 2 .

Nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices

Nine of the selected studies assessed nurses’ knowledge and attitudes related to sepsis assessment and management in critically ill adult patients [ 1 , 9 , 12 , 15 , 17 – 21 ] ( Table 3 ) . Nucera et al. [ 18 ] found that ICU nurses had poor attitudes towards blood culture collection techniques and timing and poor levels of knowledge related to the early identification, diagnosis, and management of sepsis. For example, the majority of nurses reported that there is no need to sterilize the tops of culture bottles, and there is no specific time for specimen collection [ 18 ]. However, the participating nurses reported good levels of knowledge related to blood culture procedures and the risk factors for sepsis. Similarly, R. J. Roberts et al. [ 19 ] found the participating nurses to have good knowledge of septic shock and good attitudes toward the initiation of antibiotics for critically ill adult patients with sepsis. Only two studies assessed nurses’ practices related to sepsis assessment and management [ 15 , 19 ]. For example, in the study of R. J. Roberts et al. [ 19 ], 40% of the nurse participants reported that they were aware of the importance of initiating antibiotics and IV fluid within one hour of septic shock recognition [ 20 ]. Also, Yousefi et al. [ 15 ] found the participating nurses to have good practices related to sepsis assessment and management.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270711.t003

Barriers to and facilitators of sepsis assessment and management

The reviewed studies identified three types of barriers to the early identification and management of sepsis, namely patient-, nurse-, and system-related barriers ( Table 4 ). Meanwhile, only nurse- and system-related facilitators were reported in the reviewed studies. The most-reported barriers and facilitators were system-related. The reported barriers included (a) the lack of written sepsis treatment protocols or guidelines adopted as hospital policy [ 22 , 23 ]; (b) the complexity and atypical presentation of the early symptoms of sepsis [ 19 ]; (c) nurses’ poor level of education and clinical experience [ 1 , 12 ]; (d) the lack of sepsis educational programs or training workshops for nurses [ 22 , 23 ]; (e) the high comorbid burden among patients with sepsis, which complicates the critical thinking process of sepsis management [ 19 ]; (f) nurses’ deficits in knowledge related to sepsis treatment protocols and guidelines [ 22 – 24 ]; (g) the lack of mentorship programs in which junior nurses’ actions/activities are strictly supervised by experienced nurses [ 17 , 23 ]; (h) heavy workloads or high patient-nurse ratios [ 22 ]; (i) the shortage of well-trained and experienced physicians, particularly in EDs [ 19 , 22 , 23 ]; (j) the lack of awareness related to antibiotic use for patients with sepsis [ 19 , 22 ]; (k) the lack of IV access and unavailability of ICU beds [ 25 ]; (l) the non-use of drug combinations for the treatment of sepsis [ 22 , 26 , 27 ], and (m) poor teamwork and communication skills among healthcare professionals [ 22 , 26 ]. Only three facilitators of sepsis assessment and management were identified in the reviewed studies. These facilitators were (1) nurses’ improved confidence in caring for patients with sepsis, (2) increased consistency in sepsis treatment, and (3) positive enforcement of successful stories of sepsis management [ 22 , 27 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270711.t004

Measurement tools of sepsis-related knowledge, attitudes, and practices

One of the reviewed studies used a Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practice (KAP) questionnaire developed according to the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) guidelines [ 15 ] to measure nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to sepsis assessment and management. Meanwhile, eight studies [ 1 , 9 , 12 , 17 – 21 ] used self-developed questionnaires based on the literature and SSC guidelines and validated by expert panels. Details of these measurement tools and their psychometric properties are summarized in Table 5 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270711.t005

Interventions directed at improving nurses’ sepsis assessment and management

Educational programs..

Only four of the selected studies examined the impact of educational programs on nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to sepsis management and found significant improvements in nurses’ posttest scores ( Table 6 ) [ 11 , 15 , 28 , 29 ]. For example, Drahnak’s study [ 28 ] implemented an educational program developed by the authors and integrated with patients’ health electronic records (HER) and found significant improvements in nurses’ post-test nursing knowledge scores. Another educational program developed by the authors was implemented to improve ICU nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to sepsis and found a significant improvement in posttest scores among the intervention group [ 15 ]. Another study was designed to examine the effectiveness of the Taming Sepsis Educational Program® (TSEP™) in improving nurses’ knowledge of sepsis [ 11 ]. A 15-minute structured educational session was developed to decrease the mean time needed to order a sepsis order set for critically ill patients through improving ER nurses’ knowledge about SSC guidelines and found that the mean time was reduced by 33 minutes among the intervention group [ 29 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270711.t006

Simulation.

Only two studies examined the effect of using simulation in improving the early recognition and prompt treatment of sepsis by critical care nurses ( Table 6 ) [ 30 , 31 ]. Vanderzwan et al. [ 30 ] assessed the effect of a medium-fidelity simulation incorporated into a multimodel nursing pedagogy on nurses’ knowledge of sepsis and showed significant improvements in six of the nine questionnaire items. While Giuliano et al. examined the difference in mean times required for sepsis recognition and treatment initiation between nurses exposed to two different monitor displays in response to simulated case scenarios of sepsis and showed a significant reduction in the mean times required for sepsis recognition and treatment initiation by those nurses who were exposed to enhanced bedside monitor (EBM) display [ 31 ].

Decision support tools.

Four of the selected studies examined the effectiveness of decision support tools, adapted based on the SSC guidelines and the “sepsis alert protocol”, on the early identification and management of sepsis and confirmed the effectiveness of these tools ( Table 7 ) [ 32 – 35 ]. The decision support tools used in three of the studies guided the nurses throughout their decision-making processes to reach effective assessment, high quality and timely management of sepsis, and, in turn, optimal patient outcomes [ 32 , 33 , 35 ]. However, no significant differences in the time of blood culture collection and antibiotic administration were reported between the intervention and control groups in the study of Delawder et al. [ 34 ].

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270711.t007

Sepsis protocols.

Eight of the selected studies examined the effectiveness of sepsis protocols [ 24 , 36 – 38 ] and sepsis screening tools [ 16 , 39 – 41 ] for the early assessment and management of sepsis ( Table 7 ). All of these articles revealed that the implementation of sepsis screening tools or protocols based on the SSC guidelines leads to the early identification and timely management of sepsis, as well as the improvement in nurses’ compliance to the SSC guidelines for the detection and management of sepsis. For example, in one study, patients who received Early Goal-Directed Therapy (EGDT) had a lower mortality rate as compared to patients who received usual care [ 16 ]. The sepsis screening tools and guidelines were also tested to examine their impact on some patient outcomes, and variabilities were identified. For example, the use of the Modified Early Warning Score (MEW-S) tool revealed no significant improvement in patient mortality rate [ 41 ]. In contrast, mortality rates were decreased by using the Nurse Driven Sepsis Protocol (NDS) [ 40 ], Quality Improvement (QI) initiative [ 38 ], and a computerized protocol [ 37 ]. In addition, nurses in the computerized protocol group had better compliance with the SSC guidelines than did nurses in the paper-based group [ 37 ]. One of the selected studies compared between a paper-based sepsis protocol and a computer-based protocol and found that antibiotic administration, blood cultures, and lactate level checks were conducted more often and sooner by nurses in the computerized protocol group [ 37 ]. Two of the selected studies used the EGDT as a screening tool for sepsis and found no significant differences in times of diagnosis, blood culture collection, or lactate measurements between the control and intervention groups [ 16 , 24 ]. However, significant differences were found in the time of antibiotic administration in the study of Oliver et al. [ 24 ]. Although El-khuri et al. [ 16 ] revealed no significant differences in the time of antibiotic administration, the mortality rate among patients in the intervention group declined significantly.

Most of the reviewed studies focused on assessing critical care nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to sepsis assessment and management, revealing poor levels of knowledge, moderate attitude levels, and good practices. Also, this review revealed that the three most common barriers to effective sepsis assessment and management were nursing staff shortages, delayed initiation of antibiotics, and poor teamwork skills. Meanwhile, the three most common facilitators of sepsis assessment and management were the presence of standard sepsis management protocols, professional training and staff development, and positive enforcement of successful stories of sepsis treatment. Moreover, this review reported on a wide variety of interventions directed at improving sepsis management among nurses, including educational sessions, simulations, screening or decision support tools, and intervention protocols. The impacts of these interventions on patient outcomes were also explored.

The findings of our review are consistent with the findings of previous studies which have explored critical care nurses’ knowledge related to sepsis assessment and management [ 42 ]. Also, recent studies conducted in different clinical settings support the findings of our review regarding nurses’ knowledge of sepsis. For example, a recent study conducted in a medical-surgical unit revealed that nurses had good knowledge of early sepsis identification in non-ICU adult patients [ 43 ]. The variations in nurses’ levels of knowledge related to sepsis assessment were attributed to variations in educational level and work environment (i.e., ICU vs. non-ICU).

The evidence indicates that the successful treatment of critically ill patients with suspected or actual sepsis requires early identification or assessment [ 44 , 45 ]. Early assessment is a critical step for the initiation of antibiotics for patients with sepsis, leading to improved patient outcomes and a decline in mortality rates [ 44 ]. The current review also revealed the significant role of educational programs in improving nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to the early recognition and management of sepsis. These findings are in line with the findings of another study, which tested the impact of e-learning educational modules on pediatric nurses’ retention of knowledge about sepsis [ 45 ]. The study revealed that the educational modules improved the nurses’ knowledge acquisition and retention and clinical performance related to sepsis management [ 45 ]. The findings of our review related to sepsis screening and decision support tools are in congruence with the findings of a previous clinical trial which assessed the impact of a prompt telephone call from a microbiologist upon a positive blood culture test on sepsis management [ 46 ]. The study revealed that this screening tool contributed to the prompt diagnosis of sepsis and antibiotic administration, improved patient outcomes, and reduced healthcare costs [ 46 ]. The findings of our review related to the effectiveness of educational programs in improving the assessment and management of sepsis were consistent with the findings of a recent quasi-experimental study. The study found that incorporating sepsis-related case scenarios in ongoing educational and professional training programs improved nurses’ self-efficacy and led to a prompt and accurate assessment of sepsis [ 47 ]. One of the interventions explored in this review was a simulation that facilitated decision-making related to sepsis management. The simulation was found to be effective in mimicking the real stories of patients with sepsis and proved to be a safe learning environment for inexperienced nurses before encountering real patients, increasing nurses’ competency, self-confidence, and critical thinking skills [ 48 ]. Also, a recent study showed that the combination of different interventions aimed at targeting sepsis assessment and management, including educational programs and simulation, may lead to optimal nurse and patient outcomes [ 49 ].

Limitations

The present review has several limitations. There is limited variability in the findings of the reviewed studies in terms of the main variable, sepsis. Moreover, the review excluded studies written in languages other than English and conducted among populations other than critical care nurses. However, there may be studies written in other languages which may have significant findings not considered in this review. Further, only eight databases were used to search for articles related to the topic of interest, which may have limited the number of retrieved studies. Finally, due to the heterogeneity between the selected studies, a meta-analysis was not performed.

Relevance to clinical practice

Our findings could help hospital managers in developing continuous education and staff development training programs on assessing and managing sepsis for critical care patients. Establishing continuous education, workshops, professional developmental lectures focusing on sepsis assessment and management for critical care nurses, as well as training courses on how to use evidence-based sepsis protocol and decision support and screening tools for sepsis, especially for critical care patients are highly recommended. Also, our findings could be used to development of an evidence-based standard sepsis management protocol tailored to the unmet healthcare need of patients with sepsis.

To date, nurses remain to have poor to good knowledge of and attitudes towards sepsis and report many barriers related to the early recognition and management of sepsis in adult critically ill patients. The most-reported barriers were system-related, pertaining to the implementation of evidence-based sepsis treatment protocols or guidelines. Our review indicated that despite all educational interventions, no study has collectively targeted nurses’ knowledge, attitudes, and practices related to the assessment and treatment of sepsis using a multicomponent interactive teaching method. Such a method would aim to guide nurses’ decision-making and critical thinking step by step until a prompt and effective treatment of sepsis is delivered. Also, despite all available protocols and guidelines, no study has used a multicomponent intervention to improve health outcomes in adult critically ill patients. Future research should focus on sepsis-related nurse and patient outcomes using a multilevel approach, which may include the provision of ongoing education and professional training for nurses and the implementation of a multidisciplinary sepsis treatment protocol.

Supporting information

S1 checklist. prisma 2020 checklist..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270711.s001

S1 File. Search strategies.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0270711.s002

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank the Liberian of Jordan University of Science and Technology for his help in conducting this review.

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 14. Melnyk BM, Fineout-Overholt E, editors. Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011.

Early Recognition and Management of Sepsis in the Elderly: A Case Study

Affiliation.

- 1 Alice M. Onawola, College of Nursing, The University of Alabama in Huntsville.

- PMID: 33595964

- DOI: 10.1097/CNQ.0000000000000351

Sepsis is a life-threatening and debilitating sickness in the elderly. This case study explores the importance of adequate assessment of patients on their initial presentation to the emergency department, during hospitalization, and before discharge. The clinical evaluation, recognition, and management of sepsis continue to be essential for patient survival to prevent and decrease the mortality rate. Some changes go on in the elderly organ systems and can lead to delay in identifying and treatment implementation. The use of the Third International Consensus Definition for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3) to anticipate outcomes in septic patients and the use of the Survival Sepsis Campaign for treatment guidelines promptly to improve outcomes are crucial. This article aims to inform clinicians and nurses of the importance of early recognition of subtle signs and symptoms and the management of sepsis in the elderly.

Copyright © 2021 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

- Emergency Service, Hospital

- Shock, Septic

- View All Courses

- Courses by Topic

- Live Webinars

- CE Enduring Activities

- Sponsor Courses

- Virtual Conferences

- Virtual Symposia

- Discussions

- Log In / Home

- Cart (0 items)

- Contact Sepsis Alliance

Sepsis Case Studies

Product not yet rated

Recorded On: 03/18/2020

- CE Information

- Course Contents

Description:

Delve into sepsis case studies that illustrate common assessments and tools used to care for sepsis. This presentation details case studies that cover three different healthcare areas, as well as the team members involved in the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of patients with sepsis. These cases highlight the need for all members of the healthcare team to be aware of acute changes, and the need to communicate them to the appropriate provider. It is also a reminder that patients need to be assessed at every shift for early identification and early treatment.

Learning Objectives:

At the end of the activity, the learner should be able to:

- Identify SIRS and qSOFA criteria;

- Restate the importance of early identification and treatment of sepsis across the continuum of care;

- List clinical pearls from sepsis case studies across different healthcare settings.

Target Audience:

Nurses, advanced practice providers, physicians, emergency responders, pharmacists, medical technologists, respiratory therapists, physical/occupational therapists, infection prevention specialists, data/quality specialists, and more.

Webinar Supporter:

Sepsis Alliance gratefully acknowledges the support provided for this webinar by bioMérieux.

Lori Muhr, DNP, MHSM/MHA

Sepsis program coordinator, jps health network.

Lori brings over 30 years of clinical, managerial, and educational experience to this project. She has a Doctorate Degree in Nursing Practice, a dual Master’s Degree in Management and Administration, is certified Adult Clinical Nurse Specialist, and works as an Advance Practice Nurse. She has experience in ED, Critical Care, and Community Health. Lori has experience working in rural hospitals, Level 1 Trauma centers, For-Profit and Not-for-profit organizations, all of which bring a unique perspective in her ability to reach all levels of healthcare providers. She has recently led JPS Hospital to achieve Joint Commission - Disease Specific Certification in Sepsis and has led them to be the first community safety net hospital to receive this designation. Her ability to simplify complex issues and passion for teaching comes through in her energetic and motivational style.

Provider approved by the California Board of Registered Nursing, Provider Number CEP17068 for 1.6 contact hours.

Other healthcare professionals will receive a certificate of attendance for 1.25 contact hours.

- Medical Disclaimer

The information on or available through this site is intended for educational purposes only. Sepsis Alliance does not represent or guarantee that information on or available through this site is applicable to any specific patient’s care or treatment. The educational content on or available through this site does not constitute medical advice from a physician and is not to be used as a substitute for treatment or advice from a practicing physician or other healthcare professional. Sepsis Alliance recommends users consult their physician or healthcare professional regarding any questions about whether the information on or available through this site might apply to their individual treatment or care.

Please Log In

Find sepsis education.

- Sepsis Program Overviews and Performance Improvement

- Sepsis Core Measure and Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines

- Sepsis and Technology

- Infection Prevention and Sepsis Prevention

- Sepsis Recognition, Diagnosis, Treatment, and Monitoring

- Sepsis Populations and Comorbidities

- Pre-Hospital and Post-Acute Sepsis

- Specialty Topics

- Sepsis Stories (Patients, Family, and Caregivers)

- CE Enduring Courses

- Courses by Speaker

- Privacy Policy

- Funding and Sponsorship Policy

Copyright ©2024 Sepsis Alliance. All rights reserved.

Sepsis Alliance is a tax-exempt organization under Sections 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code. Contributions are deductible for computing income estate taxes. Sepsis Alliance tax ID 38-3110993

Sepsis Patient Case Study

Executive Summary

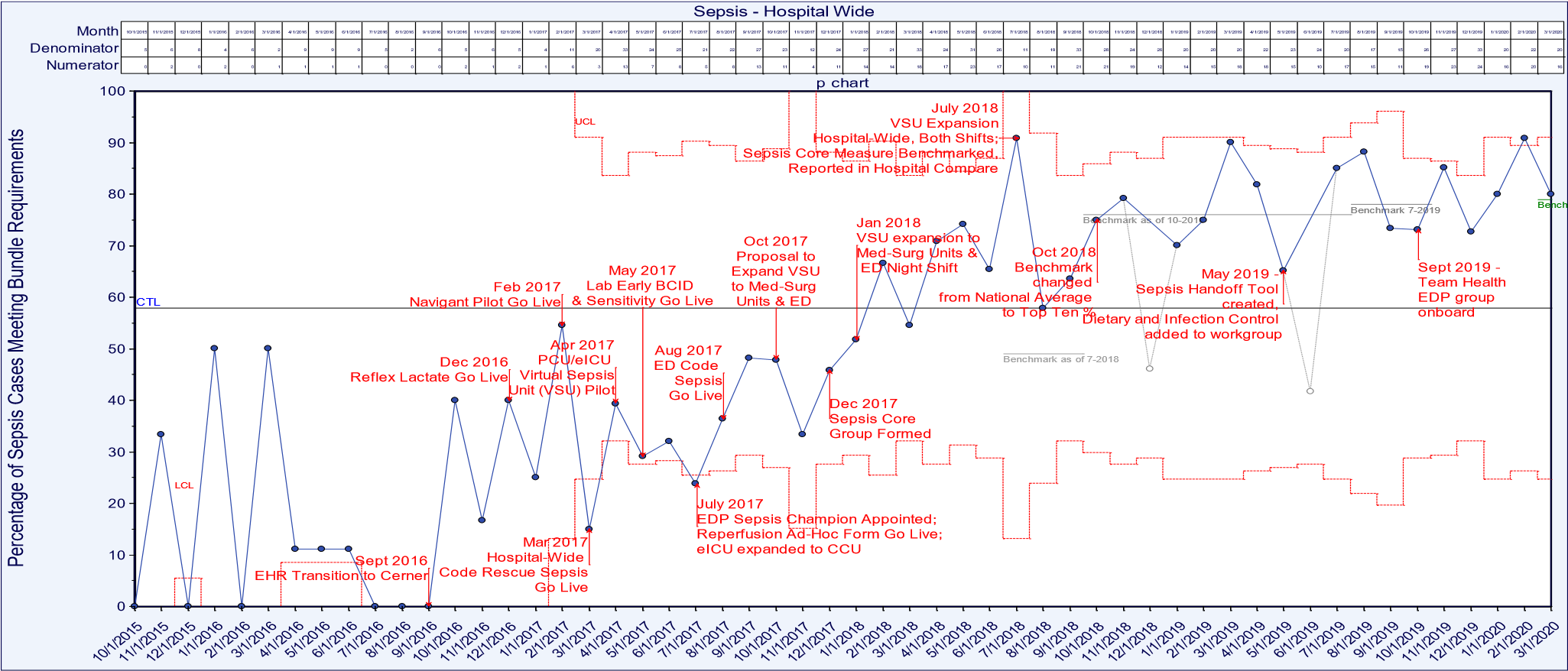

The percentage of sepsis patient cases meeting bundle requirements was below benchmark and there was opportunity to improve both mortality and length of stay (LOS).

Key Stakeholders

Medical Staff, nursing, performance improvement, virtual sepsis unit (VSU), healthcare informatics, laboratory personnel, pharmacy and patients.

People, Process and Technology

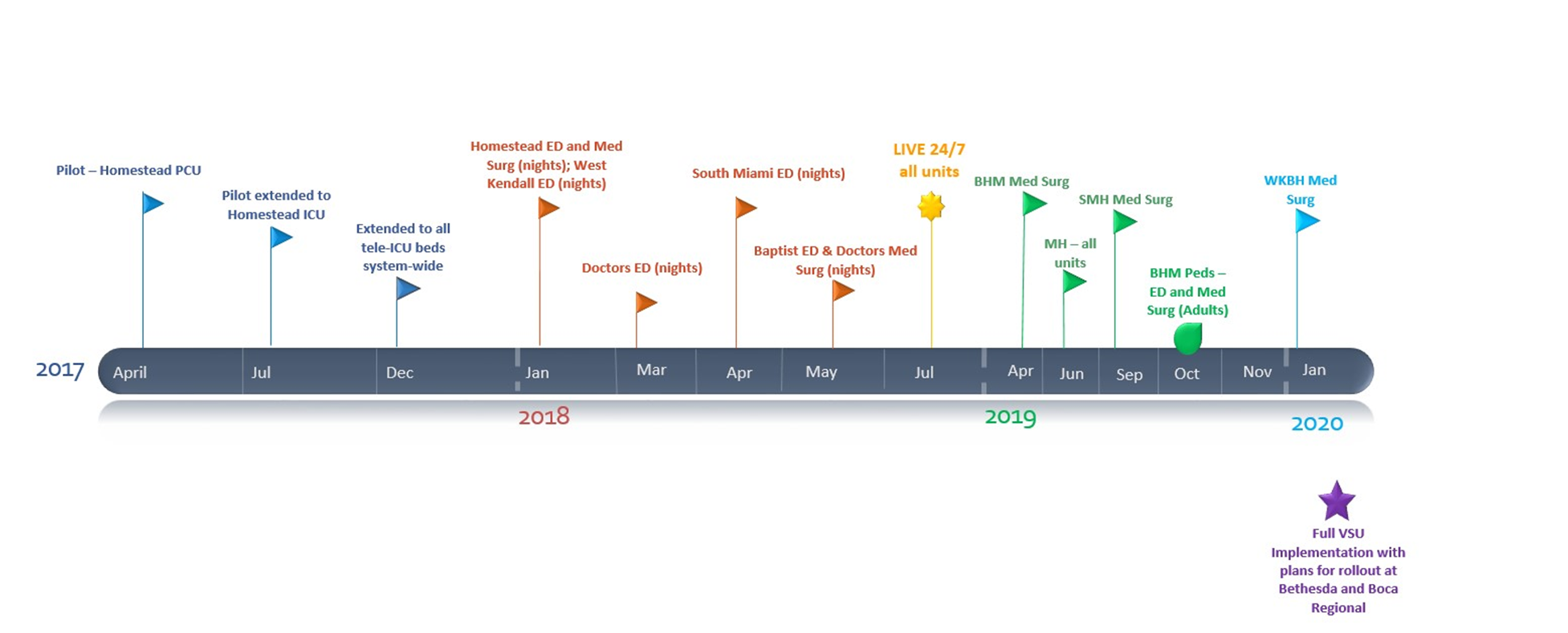

- Interdisciplinary Committee, established December 2017

- Assign patient champions

- Ongoing Physician Education (Team Health EDP group onboard)

- VSU/eICU (PCU/ICU and Med-Surg Units) April 2017; January 2018

- Sepsis Handoff Tool – May 2019

- Sepsis Bundles

- Device integration

- Bedside specimen collection and scanning

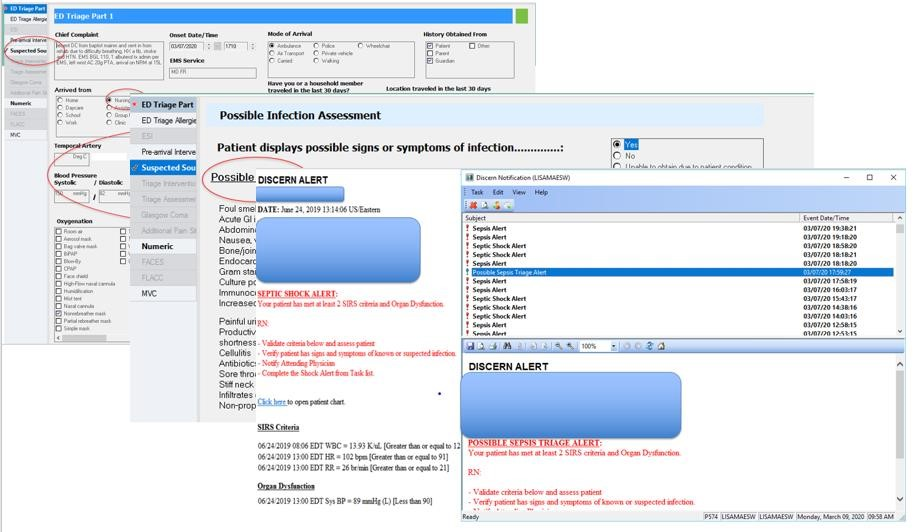

- Clinical decision support (CDS)–Alerts

- Care team communication

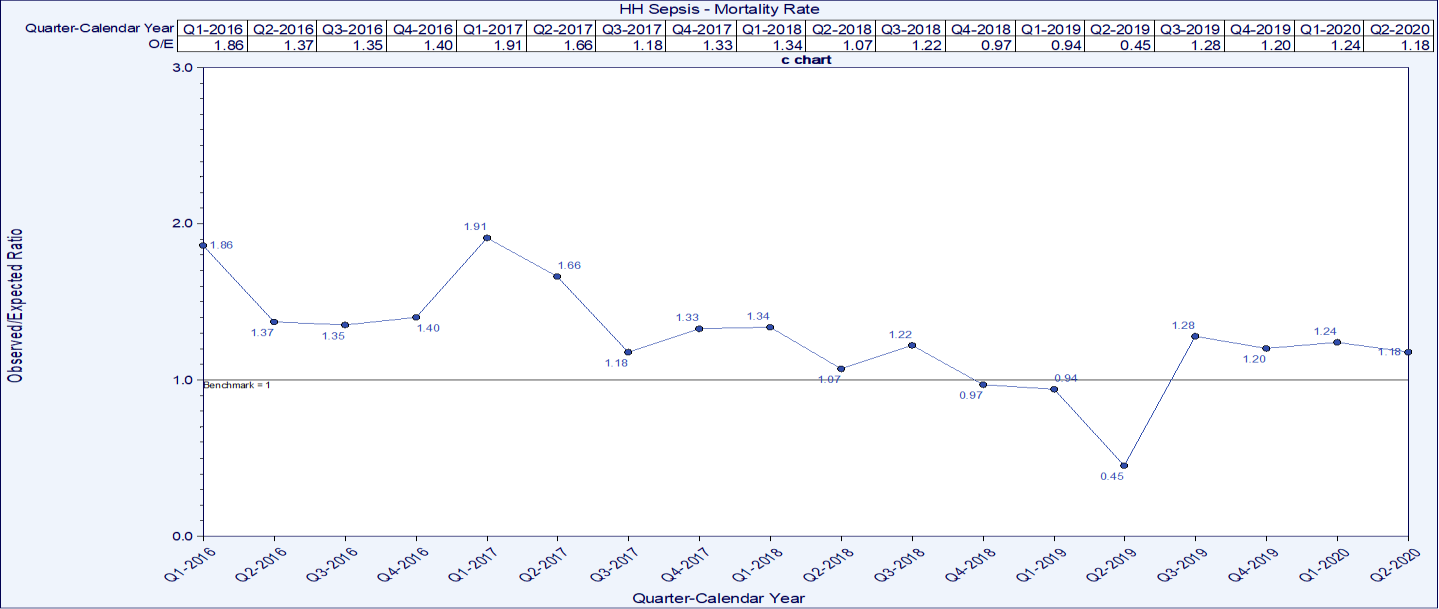

The sepsis patient mortality rate decreased from as high as 1.91 in Q1 2017 to as low as 0.45 in 2019. Cases meeting the bundle compliance increased from as low as 52% in Jan 2018 to as high as 88% in August 2019. LOS also decreased from a high of 6.83 days on average in January of 2017 to as low as 3.88 days on average in August of 2019.

Lesson Learned

- Teamwork and collaboration were instrumental in the success of bundle build and increasing bundle compliance. Accountability and the ability to measure outcomes and compliance are critical

- Assign a patient champion who is an expert in sepsis management

- Utilization of a VSU such as an eICU provides another layer of surveillance.

- CDS, alerts, dashboards and direct communication with the care teams are part of the direct communication in place to improve care.

Define the Clinical Problem and Pre-Implementation Performance

Local problem.

Our goal was to reduce clinical variation in the care of sepsis patients at Homestead Hospital and throughout the system at Baptist Health South Florida (BHSF). We engaged the care team in improving processes related to the treatment of patients presenting to respective Emergency Departments (ED), via direct admission, or who become septic during their stay.

Sepsis affects over 26 million people worldwide every year, and the organization treats over 3,000 patients annually with sepsis, severe sepsis or septic shock. Sepsis is the body’s response to an infection that has become overwhelming and can lead to tissue damage, organ failure, amputations and death. Mortality increases 8% for every hour that treatment is delayed and as many as 80% of sepsis deaths could have been prevented with rapid diagnosis and treatment. Sepsis patients have the largest cost of hospitalizations in the United States consuming more than $24 billion dollars each year. Sepsis patients also have almost double the average cost per stay at around $18,400 per admission.

Previous work to improve bundle compliance was achieved through the BHSF Accelerated Change Team (ACT), which developed system wide order sets. The reflex lactate was also implemented through the BHSF ACT enabling lab to automatically order a timed lactate to achieve follow-up lactate compliance.

Homestead Hospital has a robust sepsis patient committee that meets monthly, reviewing outcome measures and providing education, mock codes, as well as reviewing cases month to month. The organization partnered with Navigant on the T2020 initiative which includes redesigning care for select DRGs. Navigant and the organization decided upon a structure of a Sepsis Steering Committee as well as two design groups: An ED team and an inpatient and ICU team. These teams collaborated on creating clinical specification to ensure sepsis patients got the same care every patient, every time. BHSF facilities such as Homestead Hospital had varied levels of success in completing the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) 3-hour and 6-hour bundles for patients identified as septic. The inconsistency of implementing the two bundles in a timely manner led to significant LOS and improved mortality opportunities. Earlier identification and implementation of the interventions described in the bundles led to better outcomes for sepsis patients and a decrease in the LOS.

The mortality rate decreased from as high as 1.91 in Q1 2017 to as low as 0.45 in 2019. Sepsis patient cases meeting bundle compliance increased from as low as 52% in Jan 2018 to as high as 88% in August 2019. LOS also decreased from a high of 6.83 days on average in January of 2017 to as low as 3.88 days on average in August of 2019.

All patients >18 years of age are screened for sepsis, the numerator is the total count of patients treated in compliance with the bundle and the denominator includes all patients with the MS-DRG of sepsis (positive screen). Mortality rates are based on severity adjusted benchmarks and LOS is based on the average LOS against the benchmark of CMS and Premier.

Targeted performance

To meet and/or exceed the benchmark.

Benchmark data

BHSF benchmarks sepsis patient data against CMS, the Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV severity of disease classification system (ICU/PCU), Premier, and internal goals.

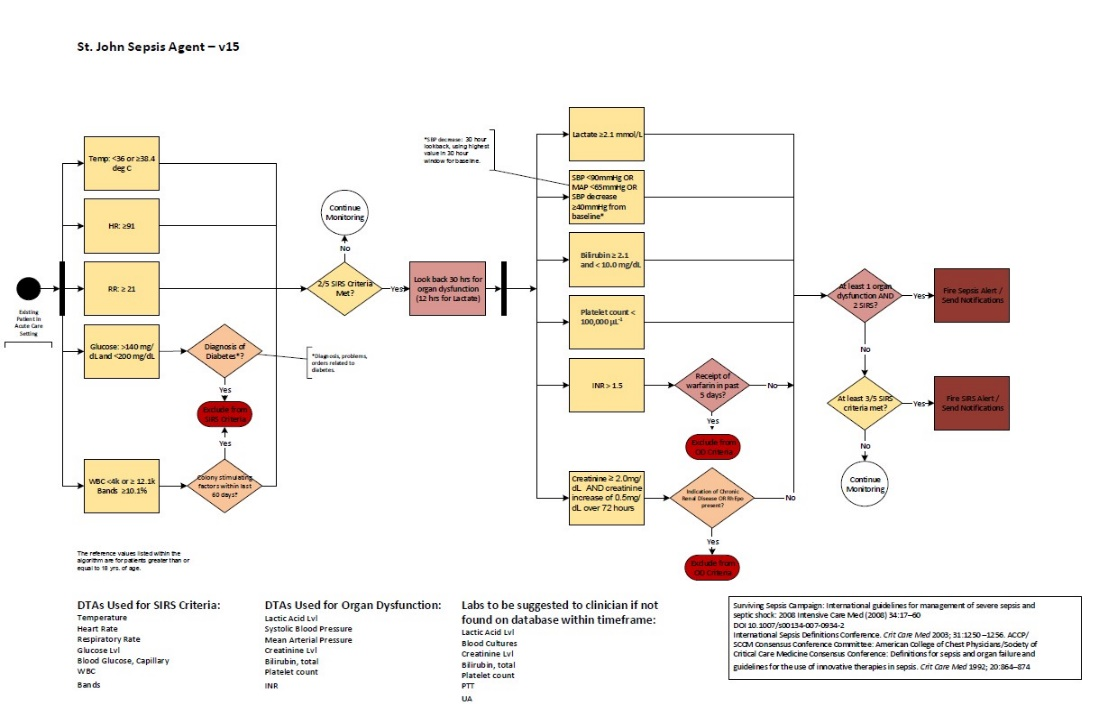

Technology initiatives

Electronic health record (EHR) data, CDS such as the St. Johns Sepsis Alert, clinical dashboards, Ascom phones for communication, the eICU for virtual care management, bedside specimen collection scanning, device integration for clinical data and bundle management via PowerPlans™.

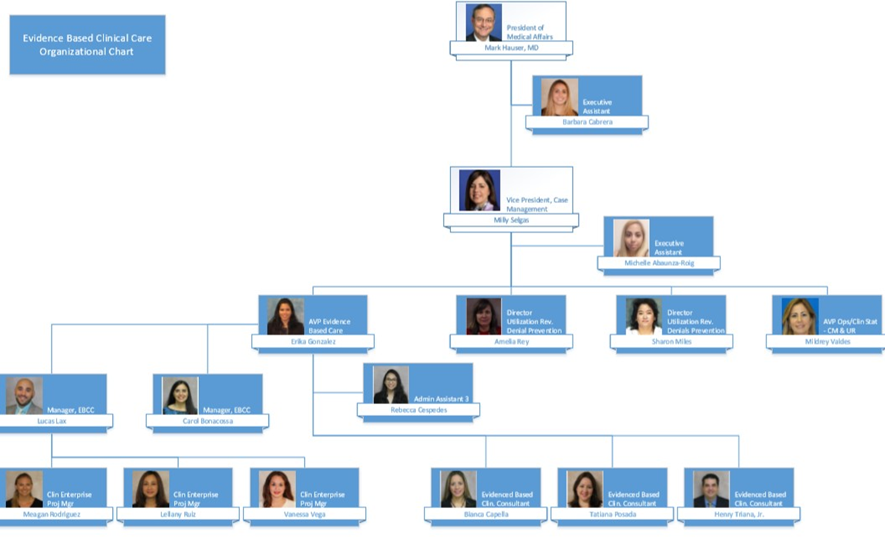

People and Process

The evidence-based clinical care (EBCC) committee oversees the organizational structure for process waves which identify areas for improvement. The VSU is a component that enhances people, process and technology. The sepsis patient champions help to optimize infection management and emphasize the importance of early recognition and timely treatment, they also facilitate sepsis patient care and optimize patient outcomes. Ongoing physician and team education are available via lunch and learns with classroom time, elbow to elbow support, web-based learning, online formats on the EBCC website via the intranet and on the Baptist Health South website which is available in the public domain. The continuing education is a vital component to the hospital-wide code rescue response team.

Design and Implementation Model Practices and Governance

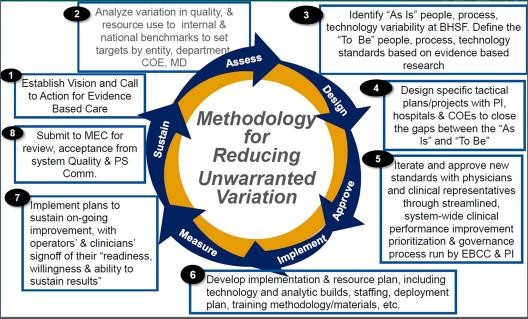

Baptist Health South Florida’s EBCC initiative is a strategic system-wide standardization effort to reduce variation and unnecessary costs while focusing on evidence-based, quality care. The process is driven by key stakeholders and is supported by real-time, statistically supported benchmarked data. The charter was signed in 2016 and provides the foundation for a methodical approach to improve patient outcomes (Figure 1).

The methodology begins with a call to action to for an evidenced based care assessment of current and future state, design plan, team approval, development of an implementation plan, measurement and sustainment plans (Figure 2).

Each specific project is supported by a sub-group who are experts in on the focus topic. The Service Line Collaborative includes:

- Cardiac and Vascular

- Critical Care

- Emergency Department

- Gastrointestinal

- Infectious Disease

- Neonatology

- Neuroscience

- Orthopedics

- Surgery/PEI/ERAS/NSQIP

Navigant and BHSF decided upon a structure for a Sepsis Steering Committee to reduce variation in the management of sepsis to improve the sepsis patient mortality rate.

Education was completed via lunch and learns with classroom time, online formats on the EBCC website via the intranet and on the organization’s website which is available in the public domain.

PowerPlan™ education is a consistent part of physician education and CME education is available with every MS-DRG or pathway as it rolls out. The pilot for the sepsis patient go-live began in February 2017 and the hospital wide go-live was April 2017. The iterations over time have continued based on new benchmarks and evidence as it becomes available.

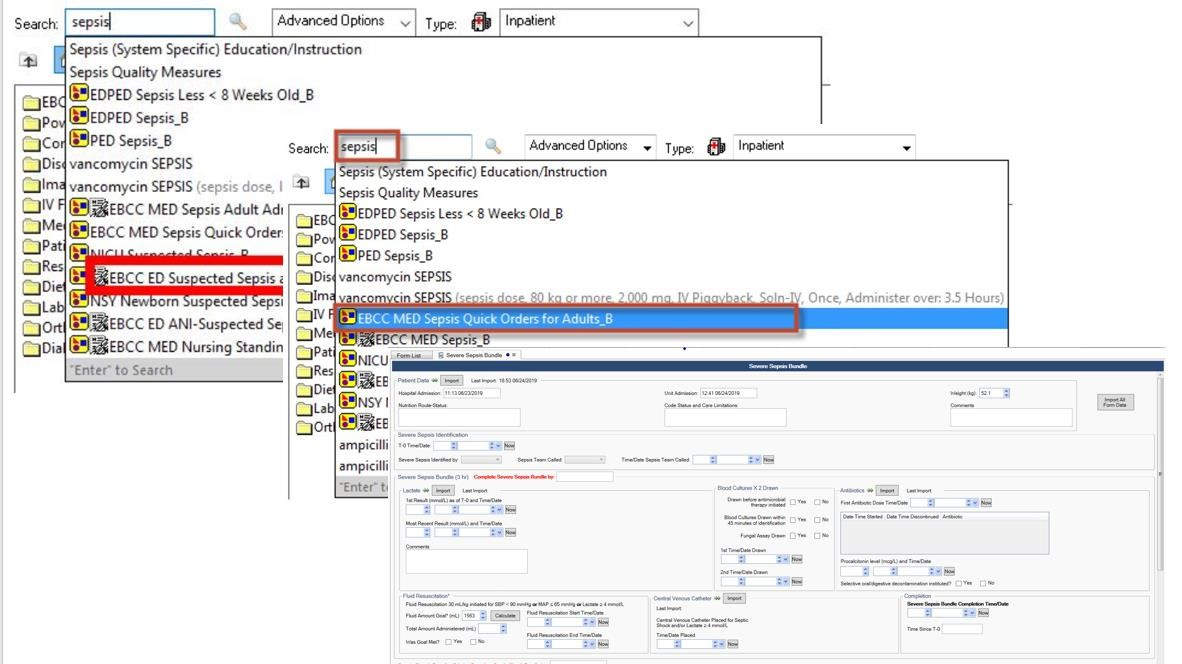

Technologies include: the physiologic data within the EHR, device integration, CDS, bedside specimen collection, sepsis algorithm, support from the eICU/VSU, dashboards and PowerPlans™ for the care bundle.

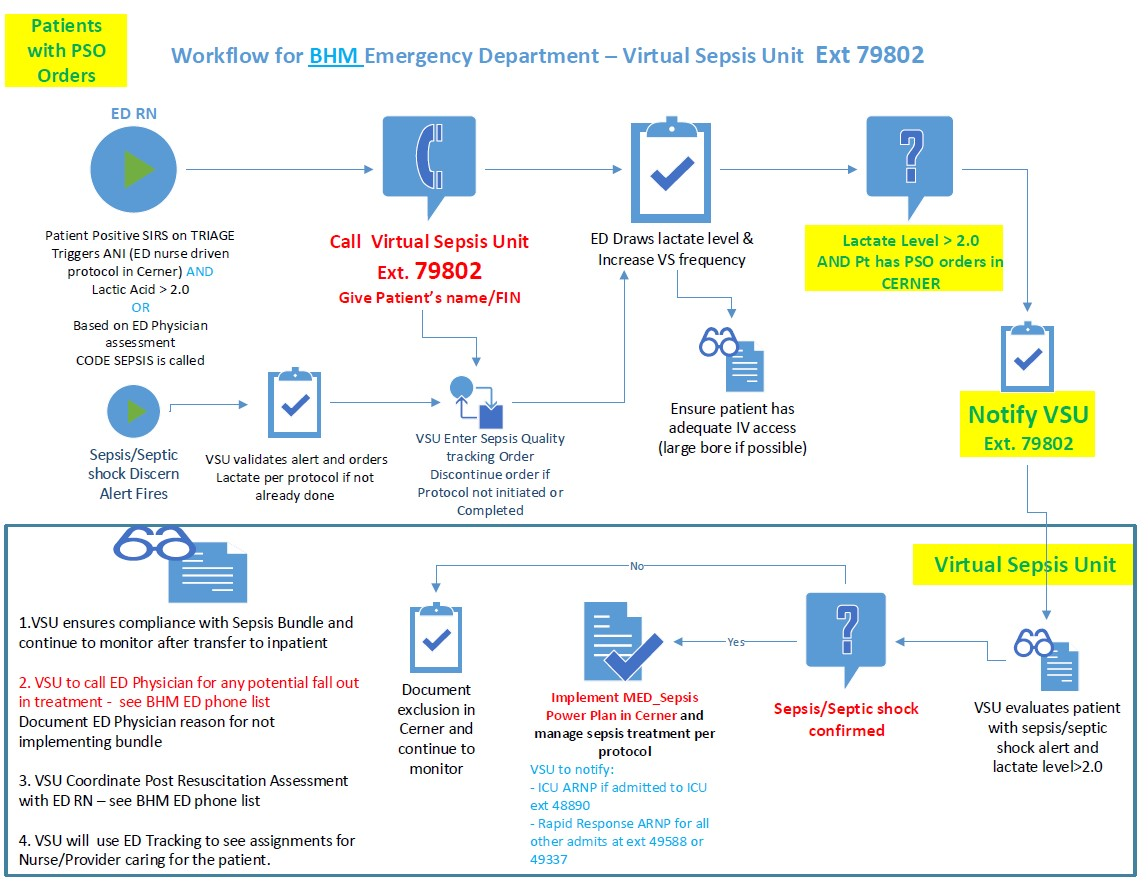

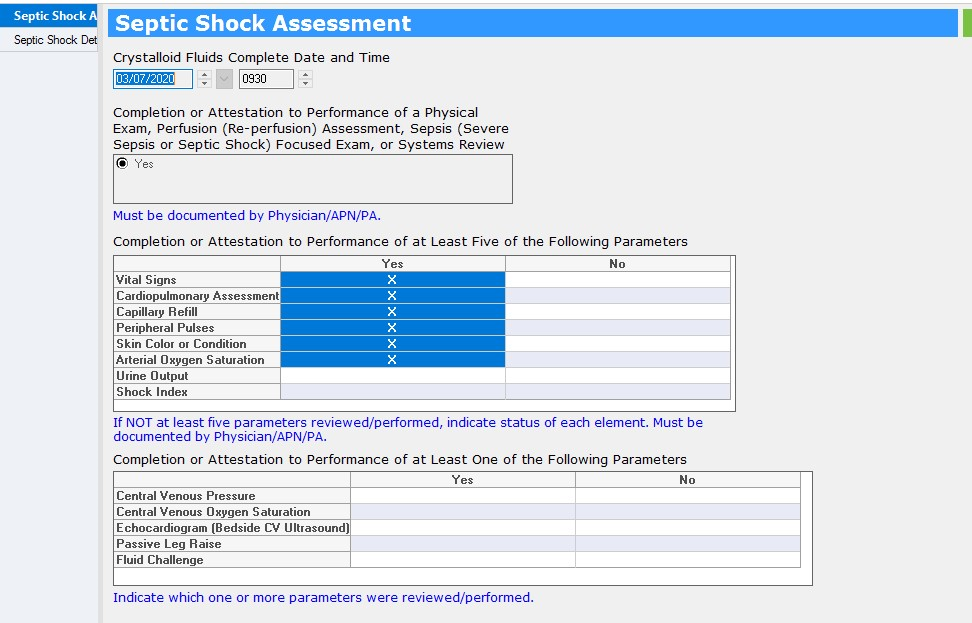

Clinical Transformation enabled through Information and Technology

To reduce clinical variation in the care of sepsis patients throughout the health system at BHSF, we engaged the care teams to improve processes related to the treatment of patients presenting to respective EDs, via direct admission, or who become septic during their stay. The workflows are geared to meet the care requirements as outlined by the industry in evidenced based research such as CMS and the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s Surviving Sepsis Campaign (Figure 3). While the overarching goal is the same throughout the venues of care, the workflows are created to meet clinical specification to ensure sepsis patients get the same care—every patient, every time. The utilization of the bundle is the foundation for minimizing the variation in care, and the people, process and technology as overseen by the EBCC committee provides the balance to drive action.

The workflows for the ED begin at triage and lead to the engagement of the VSU (Figure 4). The VSU is “air traffic control” for compliance and workflows are also designed for the ICU/PCU and med/surg areas (Figures 5 and 6). The VSU is operated out of the eICU and the virtual team streamlines the workflows to improve compliance to CMS guidelines, improving outcomes and reducing reimbursement penalties.

The algorithm that drives the alert is embedded into the EHR (Figure 7). The EHR supplies the clinical data required for the alert by integrating technologies such as vital sign devices, bedside specimen collection and scanning and lab values. Dashboards are available in the VSU, ED and nursing units to enhance access to the alerts, as well as alerting within the EHR.

Documentation of care takes place in the EHR and the CDS for the algorithm generates the alert (Figure 8).

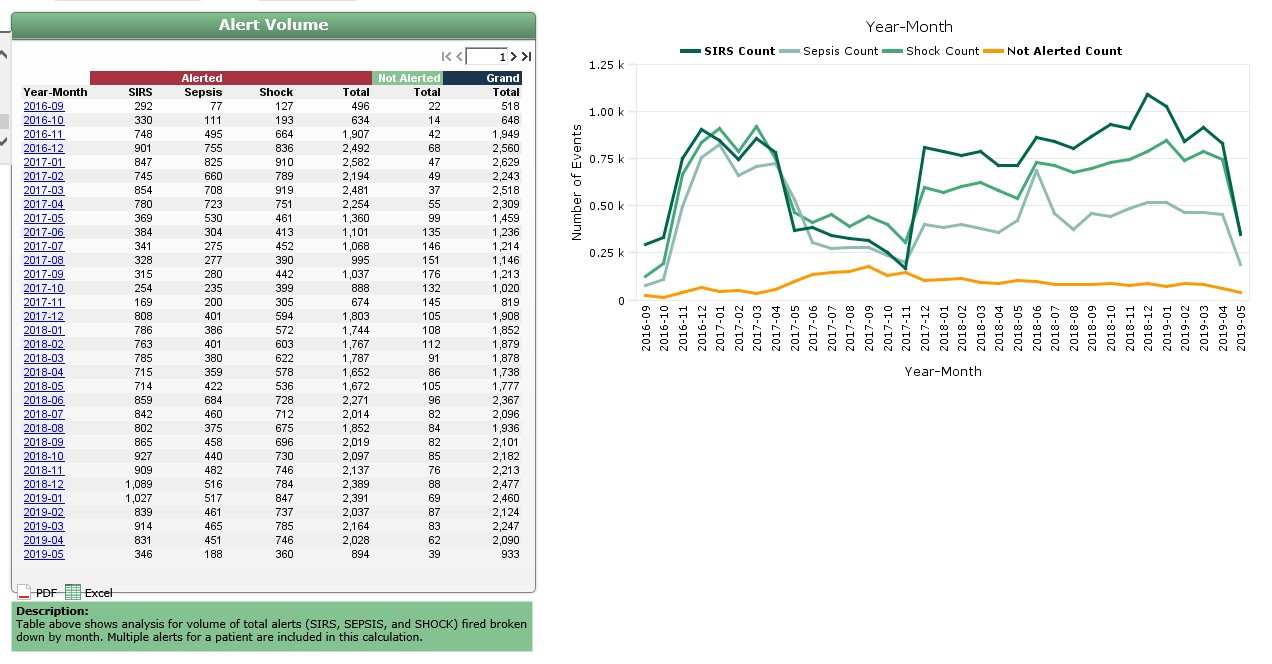

Managing the alert volume to prevent alert fatigue is a key responsibility of the VSU. The VSU reduces the number of non-actionable alerts going to physicians and nurses. Fewer alerts help to improve the specificity of the alert and provides clinical validation. (Figure 9).

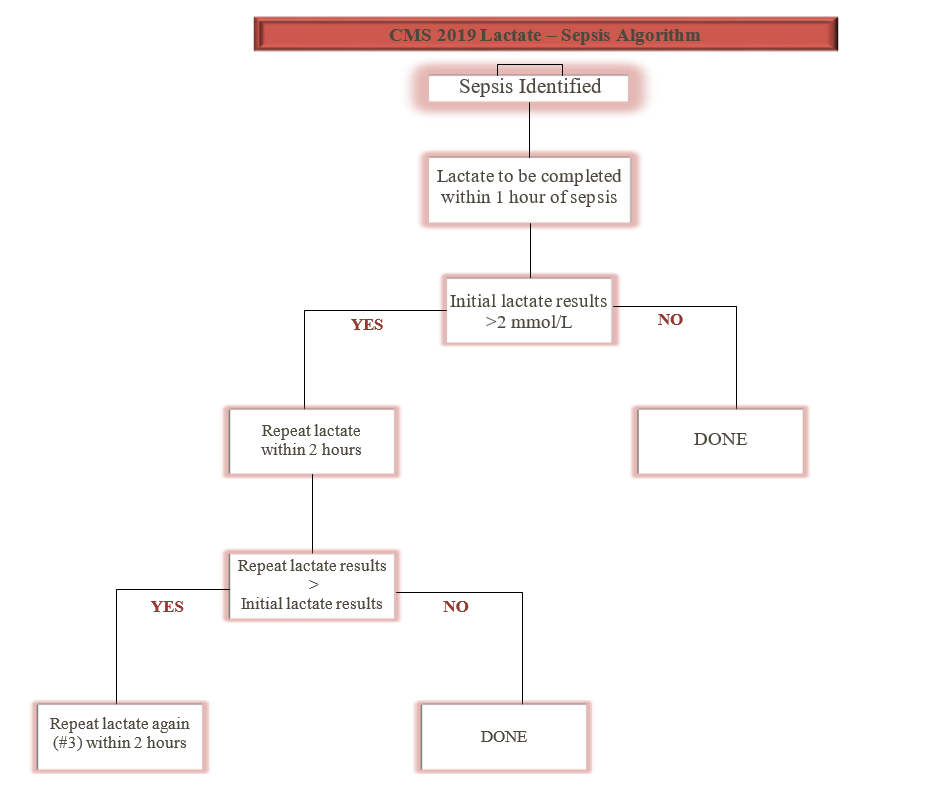

In 2019, new guidelines were released for the recommendation of lactate measures and these recommendations were built into the bundle and the workflows (Figure 10).

Examples of documentation for the bundle includes suspected sepsis patient and a quick bundle (Figure 9). Education for all care is available in the electronic version of ‘what I need to know’ (eWINK), a BHSF online education tool in the public domain which also offers CMEs/CEUs. Education for staff also includes lunch and learns with classroom time, elbow to elbow support and online formats on the EBCC website via the intranet. PowerPlan™ education is a consistent part of physician education and WINK collateral, CME education is available with every MS-DRG or pathway as it rolls out (Figure 11).

Using existing infrastructure of the eICU, virtual sepsis management was incorporated into exiting workflows. PowerPlans™ are used for bundle documentation, integration of clinical data within the EHR is supported by device integration and specimen collection and the EBCC drives pushing the current evidence to the point of care and keeps the educational material up to date.

Improving Adherence to the Standard of Care

All patients >18 years of age are screened for sepsis upon triage in the ED and all inpatients >18 years of age are monitored via CDS surveillance with the sepsis alert running within the EHR. The numerator is the total count of patients treated in compliance with the bundle and the denominator includes all patients with the MS-DRG of sepsis (positive screen). The organization transitioned to the current EHR in September of 2016 and implemented the bundle PowerPlans™ and sepsis initiative in 2017. Prior data indicated the facilities had varied levels of success in completing the bundles for patients identified as septic and the inconsistency led to opportunities to improve LOS and mortality rate.

Over time, at Homestead Hospital the compliance rate for the CMS 3-hour sepsis bundle increased from ~35% in 2015 to >90% in February 2020, with the data steward being CMS (Figure 12).

Homestead Hospital followed the standard process of change management and care redesign as outlined in the EBCC methodology. The EBCC is the governing body driving the utilization of evidence-based care focused on eliminating variation in care delivery.

Improving Patient Outcomes

The sepsis severity adjusted mortality rate decreased from as high as 1.91 in Q1 2017 to as low as 0.45 in 2019 (Figure 13). Average LOS also decreased from a high of 6.83 days on average in January of 2017 to as low as 3.88 days on average in August of 2019 (Figure 14). The risk adjusted mortality and O:E ratio are generated from Premier data.

Accountability and Driving Resilient Care Redesign

BHSF and Homestead Hospital rely on a data driven and evidence based clinical care approach to guide the design and implementation of sepsis patient care bundles. The goals of the organization’s EBCC are to decrease variation across the clinical areas and provide predictable, data-driven high quality, affordable care. Having the tools to collect as close to real-time as possible compliance data and report on that data in near-real-time reflects the ability of the organization to target and successfully improve care delivery, and ultimately improve the clinical outcomes.

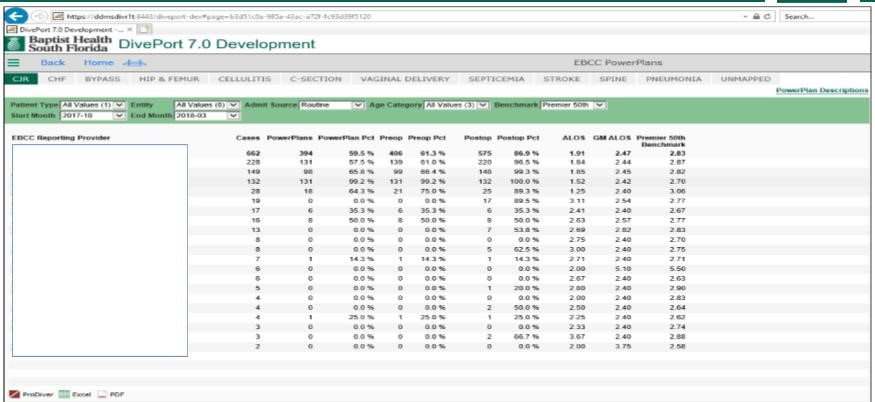

In near-real-time, the clinical team document the compliance of bundle utilization and the data is then accessible in their DivePort analytics dashboard (Figures 15 and 16). The dashboard is designed to provide statistical analysis, benchmark information and severity adjusted data with the capability to drill in multiple layers.

PowerPlans™ and bundle utilization is also available in DivePort, lending to the capability of measuring and reporting not only on the outcomes, but also to the compliance of the guidelines (Figure 17).

Using analytics to find variation

- APR-DRG Population Group is identified based on cost opportunity when compared to HCUP 40th percentile (Total Cost Per Case and ALOS).

- EBCC and Analytics Integrity Committee members review MS-DRG specific groupings that correspond with APR-DRG grouping.

- Premier benchmark levels of 50th and 75th percentile variable cost opportunities are used to further validate the data.

- MS-DRGs are recommended for EBCC team redesign based on variable cost opportunity, average LOS and volume.

- EBCC DivePort 7.0 Portal reporting is updated as DRGs waves are defined for tracking outcomes.

The rollout of the VSU is an example of using data to further refine the care redesign to complement the people, process and technology to enhance care delivery (Figure 18).

The views and opinions expressed in this content or by commenters are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of HIMSS or its affiliates.

HIMSS Davies Awards

The HIMSS Davies Award showcases the thoughtful application of health information and technology to substantially improve clinical care delivery, patient outcomes and population health.

Begin Your Path to a Davies Award

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

7: Case Study #6- Sepsis

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 9901

- 7.1: Learning Objectives

- 7.2: Patient- George Thomas

- 7.3: Sleepy Hollow Care Facility

- 7.4: Emergency Room

- 7.5: Day 1- Medical Ward

- 7.6: Day 2- Medical Ward

This website is intended for healthcare professionals

- { $refs.search.focus(); })" aria-controls="searchpanel" :aria-expanded="open" class="hidden lg:inline-flex justify-end text-gray-800 hover:text-primary py-2 px-4 lg:px-0 items-center text-base font-medium"> Search

Search menu

Berg D, Gerlach H. Recent advances in understanding and managing sepsis [version 1; peer review: 3 approved].: F1000 Research; 2018 https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.15758.1

Churpek MM, Snyder A, Han X Quick sepsis-related organ failure assessment, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and early warning scores for detecting clinical deterioration in infected patients outside the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med.. 2017; 195:(7)906-911 https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201604-0854OC

Daniels R, Nutbeam T, McNamara G, Galvin C. The sepsis six and the severe sepsis resuscitation bundle: a prospective observational cohort study. Emerg Med J.. 2011; 28:(6)507-512 https://doi.org/10.1136/emj.2010.095067

The sepsis manual. 2019. https://sepsistrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/5th-Edition-manual-080120.pdf (accessed 10 November 2020)

Gotts JE, Matthay MA. Sepsis: pathophysiology and clinical management. BMJ.. 2016; 353 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1585

Gyawali B, Ramakrishna K, Dhamoon AS. Sepsis: The evolution in definition, pathophysiology, and management. SAGE Open Med.. 2019; 21:(7) https://doi.org/10.1177/2050312119835043

Kumar P, Jordan M, Caesar J, Miller S. Improving the management of sepsis in a district general hospital by implementing the ‘Sepsis Six’ recommendations. BMJ Qual Improv Rep.. 2015; 4:(1) https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjquality.u207871.w4032

Lavallée JF, Gray TA, Dumville J, Russell W, Cullum N. The effects of care bundles on patient outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Implement Sci.. 2017; 12:(1) https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0670–0

Lee SM, An WS. New clinical criteria for septic shock: serum lactate level as new emerging vital sign. J Thorac Dis.. 2016; 8:(7)1388-90 https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd.2016.05.55

NHS England. Improving outcomes for patients with sepsis: a cross-system action plan. 2015. https://tinyurl.com/gm4zkps (accessed 10 November 2020)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Neutropenic sepsis: prevention and management in people with cancer. Clinical guideline CG151. 2012. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg151 (accessed 10 November 2020)

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Sepsis: recognition, diagnosis and early management. NICE guideline NG51. 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng51 (accessed 10 November 2020)

Porth CM. Essentials of pathophysiology, 4th edn. Philadelphia (PA): Wolters Kluwer; 2015

Royal College of Physicians. National Early Warning Score (NEWS) 2. Standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS. Updated report of a working party. 2017. https://tinyurl.com/y5kbsnoa (accessed 10 November 2020)

Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA.. 2016; 315:(8)801-810 https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.0287