How To Write A Research Paper

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + FREE Template

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | March 2024

For many students, crafting a strong research paper from scratch can feel like a daunting task – and rightly so! In this post, we’ll unpack what a research paper is, what it needs to do , and how to write one – in three easy steps. 🙂

Overview: Writing A Research Paper

What (exactly) is a research paper.

- How to write a research paper

- Stage 1 : Topic & literature search

- Stage 2 : Structure & outline

- Stage 3 : Iterative writing

- Key takeaways

Let’s start by asking the most important question, “ What is a research paper? ”.

Simply put, a research paper is a scholarly written work where the writer (that’s you!) answers a specific question (this is called a research question ) through evidence-based arguments . Evidence-based is the keyword here. In other words, a research paper is different from an essay or other writing assignments that draw from the writer’s personal opinions or experiences. With a research paper, it’s all about building your arguments based on evidence (we’ll talk more about that evidence a little later).

Now, it’s worth noting that there are many different types of research papers , including analytical papers (the type I just described), argumentative papers, and interpretative papers. Here, we’ll focus on analytical papers , as these are some of the most common – but if you’re keen to learn about other types of research papers, be sure to check out the rest of the blog .

With that basic foundation laid, let’s get down to business and look at how to write a research paper .

Overview: The 3-Stage Process

While there are, of course, many potential approaches you can take to write a research paper, there are typically three stages to the writing process. So, in this tutorial, we’ll present a straightforward three-step process that we use when working with students at Grad Coach.

These three steps are:

- Finding a research topic and reviewing the existing literature

- Developing a provisional structure and outline for your paper, and

- Writing up your initial draft and then refining it iteratively

Let’s dig into each of these.

Need a helping hand?

Step 1: Find a topic and review the literature

As we mentioned earlier, in a research paper, you, as the researcher, will try to answer a question . More specifically, that’s called a research question , and it sets the direction of your entire paper. What’s important to understand though is that you’ll need to answer that research question with the help of high-quality sources – for example, journal articles, government reports, case studies, and so on. We’ll circle back to this in a minute.

The first stage of the research process is deciding on what your research question will be and then reviewing the existing literature (in other words, past studies and papers) to see what they say about that specific research question. In some cases, your professor may provide you with a predetermined research question (or set of questions). However, in many cases, you’ll need to find your own research question within a certain topic area.

Finding a strong research question hinges on identifying a meaningful research gap – in other words, an area that’s lacking in existing research. There’s a lot to unpack here, so if you wanna learn more, check out the plain-language explainer video below.

Once you’ve figured out which question (or questions) you’ll attempt to answer in your research paper, you’ll need to do a deep dive into the existing literature – this is called a “ literature search ”. Again, there are many ways to go about this, but your most likely starting point will be Google Scholar .

If you’re new to Google Scholar, think of it as Google for the academic world. You can start by simply entering a few different keywords that are relevant to your research question and it will then present a host of articles for you to review. What you want to pay close attention to here is the number of citations for each paper – the more citations a paper has, the more credible it is (generally speaking – there are some exceptions, of course).

Ideally, what you’re looking for are well-cited papers that are highly relevant to your topic. That said, keep in mind that citations are a cumulative metric , so older papers will often have more citations than newer papers – just because they’ve been around for longer. So, don’t fixate on this metric in isolation – relevance and recency are also very important.

Beyond Google Scholar, you’ll also definitely want to check out academic databases and aggregators such as Science Direct, PubMed, JStor and so on. These will often overlap with the results that you find in Google Scholar, but they can also reveal some hidden gems – so, be sure to check them out.

Once you’ve worked your way through all the literature, you’ll want to catalogue all this information in some sort of spreadsheet so that you can easily recall who said what, when and within what context. If you’d like, we’ve got a free literature spreadsheet that helps you do exactly that.

Step 2: Develop a structure and outline

With your research question pinned down and your literature digested and catalogued, it’s time to move on to planning your actual research paper .

It might sound obvious, but it’s really important to have some sort of rough outline in place before you start writing your paper. So often, we see students eagerly rushing into the writing phase, only to land up with a disjointed research paper that rambles on in multiple

Now, the secret here is to not get caught up in the fine details . Realistically, all you need at this stage is a bullet-point list that describes (in broad strokes) what you’ll discuss and in what order. It’s also useful to remember that you’re not glued to this outline – in all likelihood, you’ll chop and change some sections once you start writing, and that’s perfectly okay. What’s important is that you have some sort of roadmap in place from the start.

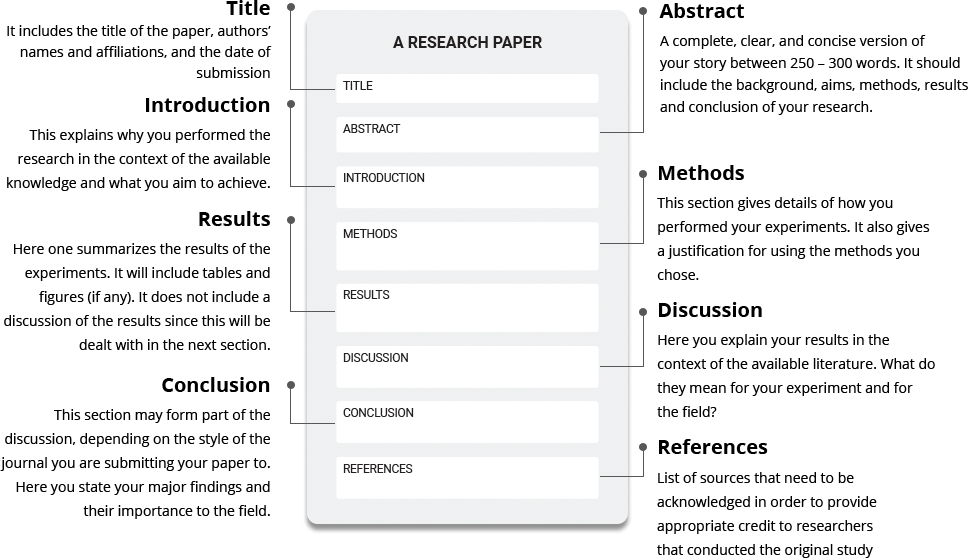

At this stage you might be wondering, “ But how should I structure my research paper? ”. Well, there’s no one-size-fits-all solution here, but in general, a research paper will consist of a few relatively standardised components:

- Introduction

- Literature review

- Methodology

Let’s take a look at each of these.

First up is the introduction section . As the name suggests, the purpose of the introduction is to set the scene for your research paper. There are usually (at least) four ingredients that go into this section – these are the background to the topic, the research problem and resultant research question , and the justification or rationale. If you’re interested, the video below unpacks the introduction section in more detail.

The next section of your research paper will typically be your literature review . Remember all that literature you worked through earlier? Well, this is where you’ll present your interpretation of all that content . You’ll do this by writing about recent trends, developments, and arguments within the literature – but more specifically, those that are relevant to your research question . The literature review can oftentimes seem a little daunting, even to seasoned researchers, so be sure to check out our extensive collection of literature review content here .

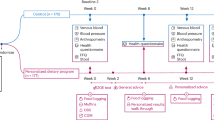

With the introduction and lit review out of the way, the next section of your paper is the research methodology . In a nutshell, the methodology section should describe to your reader what you did (beyond just reviewing the existing literature) to answer your research question. For example, what data did you collect, how did you collect that data, how did you analyse that data and so on? For each choice, you’ll also need to justify why you chose to do it that way, and what the strengths and weaknesses of your approach were.

Now, it’s worth mentioning that for some research papers, this aspect of the project may be a lot simpler . For example, you may only need to draw on secondary sources (in other words, existing data sets). In some cases, you may just be asked to draw your conclusions from the literature search itself (in other words, there may be no data analysis at all). But, if you are required to collect and analyse data, you’ll need to pay a lot of attention to the methodology section. The video below provides an example of what the methodology section might look like.

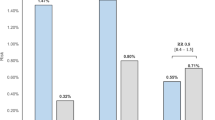

By this stage of your paper, you will have explained what your research question is, what the existing literature has to say about that question, and how you analysed additional data to try to answer your question. So, the natural next step is to present your analysis of that data . This section is usually called the “results” or “analysis” section and this is where you’ll showcase your findings.

Depending on your school’s requirements, you may need to present and interpret the data in one section – or you might split the presentation and the interpretation into two sections. In the latter case, your “results” section will just describe the data, and the “discussion” is where you’ll interpret that data and explicitly link your analysis back to your research question. If you’re not sure which approach to take, check in with your professor or take a look at past papers to see what the norms are for your programme.

Alright – once you’ve presented and discussed your results, it’s time to wrap it up . This usually takes the form of the “ conclusion ” section. In the conclusion, you’ll need to highlight the key takeaways from your study and close the loop by explicitly answering your research question. Again, the exact requirements here will vary depending on your programme (and you may not even need a conclusion section at all) – so be sure to check with your professor if you’re unsure.

Step 3: Write and refine

Finally, it’s time to get writing. All too often though, students hit a brick wall right about here… So, how do you avoid this happening to you?

Well, there’s a lot to be said when it comes to writing a research paper (or any sort of academic piece), but we’ll share three practical tips to help you get started.

First and foremost , it’s essential to approach your writing as an iterative process. In other words, you need to start with a really messy first draft and then polish it over multiple rounds of editing. Don’t waste your time trying to write a perfect research paper in one go. Instead, take the pressure off yourself by adopting an iterative approach.

Secondly , it’s important to always lean towards critical writing , rather than descriptive writing. What does this mean? Well, at the simplest level, descriptive writing focuses on the “ what ”, while critical writing digs into the “ so what ” – in other words, the implications . If you’re not familiar with these two types of writing, don’t worry! You can find a plain-language explanation here.

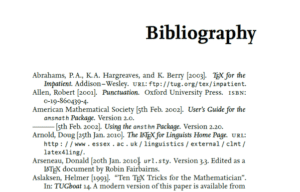

Last but not least, you’ll need to get your referencing right. Specifically, you’ll need to provide credible, correctly formatted citations for the statements you make. We see students making referencing mistakes all the time and it costs them dearly. The good news is that you can easily avoid this by using a simple reference manager . If you don’t have one, check out our video about Mendeley, an easy (and free) reference management tool that you can start using today.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. To recap, the three steps to writing a high-quality research paper are:

- To choose a research question and review the literature

- To plan your paper structure and draft an outline

- To take an iterative approach to writing, focusing on critical writing and strong referencing

Remember, this is just a b ig-picture overview of the research paper development process and there’s a lot more nuance to unpack. So, be sure to grab a copy of our free research paper template to learn more about how to write a research paper.

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

How to Write a Research Paper

Use the links below to jump directly to any section of this guide:

Research Paper Fundamentals

How to choose a topic or question, how to create a working hypothesis or thesis, common research paper methodologies, how to gather and organize evidence , how to write an outline for your research paper, how to write a rough draft, how to revise your draft, how to produce a final draft, resources for teachers .

It is not fair to say that no one writes anymore. Just about everyone writes text messages, brief emails, or social media posts every single day. Yet, most people don't have a lot of practice with the formal, organized writing required for a good academic research paper. This guide contains links to a variety of resources that can help demystify the process. Some of these resources are intended for teachers; they contain exercises, activities, and teaching strategies. Other resources are intended for direct use by students who are struggling to write papers, or are looking for tips to make the process go more smoothly.

The resources in this section are designed to help students understand the different types of research papers, the general research process, and how to manage their time. Below, you'll find links from university writing centers, the trusted Purdue Online Writing Lab, and more.

What is an Academic Research Paper?

"Genre and the Research Paper" (Purdue OWL)

There are different types of research papers. Different types of scholarly questions will lend themselves to one format or another. This is a brief introduction to the two main genres of research paper: analytic and argumentative.

"7 Most Popular Types of Research Papers" (Personal-writer.com)

This resource discusses formats that high school students commonly encounter, such as the compare and contrast essay and the definitional essay. Please note that the inclusion of this link is not an endorsement of this company's paid service.

How to Prepare and Plan Out Writing a Research Paper

Teachers can give their students a step-by-step guide like these to help them understand the different steps of the research paper process. These guides can be combined with the time management tools in the next subsection to help students come up with customized calendars for completing their papers.

"Ten Steps for Writing Research Papers" (American University)

This resource from American University is a comprehensive guide to the research paper writing process, and includes examples of proper research questions and thesis topics.

"Steps in Writing a Research Paper" (SUNY Empire State College)

This guide breaks the research paper process into 11 steps. Each "step" links to a separate page, which describes the work entailed in completing it.

How to Manage Time Effectively

The links below will help students determine how much time is necessary to complete a paper. If your sources are not available online or at your local library, you'll need to leave extra time for the Interlibrary Loan process. Remember that, even if you do not need to consult secondary sources, you'll still need to leave yourself ample time to organize your thoughts.

"Research Paper Planner: Timeline" (Baylor University)

This interactive resource from Baylor University creates a suggested writing schedule based on how much time a student has to work on the assignment.

"Research Paper Planner" (UCLA)

UCLA's library offers this step-by-step guide to the research paper writing process, which also includes a suggested planning calendar.

There's a reason teachers spend a long time talking about choosing a good topic. Without a good topic and a well-formulated research question, it is almost impossible to write a clear and organized paper. The resources below will help you generate ideas and formulate precise questions.

"How to Select a Research Topic" (Univ. of Michigan-Flint)

This resource is designed for college students who are struggling to come up with an appropriate topic. A student who uses this resource and still feels unsure about his or her topic should consult the course instructor for further personalized assistance.

"25 Interesting Research Paper Topics to Get You Started" (Kibin)

This resource, which is probably most appropriate for high school students, provides a list of specific topics to help get students started. It is broken into subsections, such as "paper topics on local issues."

"Writing a Good Research Question" (Grand Canyon University)

This introduction to research questions includes some embedded videos, as well as links to scholarly articles on research questions. This resource would be most appropriate for teachers who are planning lessons on research paper fundamentals.

"How to Write a Research Question the Right Way" (Kibin)

This student-focused resource provides more detail on writing research questions. The language is accessible, and there are embedded videos and examples of good and bad questions.

It is important to have a rough hypothesis or thesis in mind at the beginning of the research process. People who have a sense of what they want to say will have an easier time sorting through scholarly sources and other information. The key, of course, is not to become too wedded to the draft hypothesis or thesis. Just about every working thesis gets changed during the research process.

CrashCourse Video: "Sociology Research Methods" (YouTube)

Although this video is tailored to sociology students, it is applicable to students in a variety of social science disciplines. This video does a good job demonstrating the connection between the brainstorming that goes into selecting a research question and the formulation of a working hypothesis.

"How to Write a Thesis Statement for an Analytical Essay" (YouTube)

Students writing analytical essays will not develop the same type of working hypothesis as students who are writing research papers in other disciplines. For these students, developing the working thesis may happen as a part of the rough draft (see the relevant section below).

"Research Hypothesis" (Oakland Univ.)

This resource provides some examples of hypotheses in social science disciplines like Political Science and Criminal Justice. These sample hypotheses may also be useful for students in other soft social sciences and humanities disciplines like History.

When grading a research paper, instructors look for a consistent methodology. This section will help you understand different methodological approaches used in research papers. Students will get the most out of these resources if they use them to help prepare for conversations with teachers or discussions in class.

"Types of Research Designs" (USC)

A "research design," used for complex papers, is related to the paper's method. This resource contains introductions to a variety of popular research designs in the social sciences. Although it is not the most intuitive site to read, the information here is very valuable.

"Major Research Methods" (YouTube)

Although this video is a bit on the dry side, it provides a comprehensive overview of the major research methodologies in a format that might be more accessible to students who have struggled with textbooks or other written resources.

"Humanities Research Strategies" (USC)

This is a portal where students can learn about four methodological approaches for humanities papers: Historical Methodologies, Textual Criticism, Conceptual Analysis, and the Synoptic method.

"Selected Major Social Science Research Methods: Overview" (National Academies Press)

This appendix from the book Using Science as Evidence in Public Policy , printed by National Academies Press, introduces some methods used in social science papers.

"Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper: 6. The Methodology" (USC)

This resource from the University of Southern California's library contains tips for writing a methodology section in a research paper.

How to Determine the Best Methodology for You

Anyone who is new to writing research papers should be sure to select a method in consultation with their instructor. These resources can be used to help prepare for that discussion. They may also be used on their own by more advanced students.

"Choosing Appropriate Research Methodologies" (Palgrave Study Skills)

This friendly and approachable resource from Palgrave Macmillan can be used by students who are just starting to think about appropriate methodologies.

"How to Choose Your Research Methods" (NFER (UK))

This is another approachable resource students can use to help narrow down the most appropriate methods for their research projects.

The resources in this section introduce the process of gathering scholarly sources and collecting evidence. You'll find a range of material here, from introductory guides to advanced explications best suited to college students. Please consult the LitCharts How to Do Academic Research guide for a more comprehensive list of resources devoted to finding scholarly literature.

Google Scholar

Students who have access to library websites with detailed research guides should start there, but people who do not have access to those resources can begin their search for secondary literature here.

"Gathering Appropriate Information" (Texas Gateway)

This resource from the Texas Gateway for online resources introduces students to the research process, and contains interactive exercises. The level of complexity is suitable for middle school, high school, and introductory college classrooms.

"An Overview of Quantitative and Qualitative Data Collection Methods" (NSF)

This PDF from the National Science Foundation goes into detail about best practices and pitfalls in data collection across multiple types of methodologies.

"Social Science Methods for Data Collection and Analysis" (Swiss FIT)

This resource is appropriate for advanced undergraduates or teachers looking to create lessons on research design and data collection. It covers techniques for gathering data via interviews, observations, and other methods.

"Collecting Data by In-depth Interviewing" (Leeds Univ.)

This resource contains enough information about conducting interviews to make it useful for teachers who want to create a lesson plan, but is also accessible enough for college juniors or seniors to make use of it on their own.

There is no "one size fits all" outlining technique. Some students might devote all their energy and attention to the outline in order to avoid the paper. Other students may benefit from being made to sit down and organize their thoughts into a lengthy sentence outline. The resources in this section include strategies and templates for multiple types of outlines.

"Topic vs. Sentence Outlines" (UC Berkeley)

This resource introduces two basic approaches to outlining: the shorter topic-based approach, and the longer, more detailed sentence-based approach. This resource also contains videos on how to develop paper paragraphs from the sentence-based outline.

"Types of Outlines and Samples" (Purdue OWL)

The Purdue Online Writing Lab's guide is a slightly less detailed discussion of different types of outlines. It contains several sample outlines.

"Writing An Outline" (Austin C.C.)

This resource from a community college contains sample outlines from an American history class that students can use as models.

"How to Structure an Outline for a College Paper" (YouTube)

This brief (sub-2 minute) video from the ExpertVillage YouTube channel provides a model of outline writing for students who are struggling with the idea.

"Outlining" (Harvard)

This is a good resource to consult after completing a draft outline. It offers suggestions for making sure your outline avoids things like unnecessary repetition.

As with outlines, rough drafts can take on many different forms. These resources introduce teachers and students to the various approaches to writing a rough draft. This section also includes resources that will help you cite your sources appropriately according to the MLA, Chicago, and APA style manuals.

"Creating a Rough Draft for a Research Paper" (Univ. of Minnesota)

This resource is useful for teachers in particular, as it provides some suggested exercises to help students with writing a basic rough draft.

Rough Draft Assignment (Duke of Definition)

This sample assignment, with a brief list of tips, was developed by a high school teacher who runs a very successful and well-reviewed page of educational resources.

"Creating the First Draft of Your Research Paper" (Concordia Univ.)

This resource will be helpful for perfectionists or procrastinators, as it opens by discussing the problem of avoiding writing. It also provides a short list of suggestions meant to get students writing.

Using Proper Citations

There is no such thing as a rough draft of a scholarly citation. These links to the three major citation guides will ensure that your citations follow the correct format. Please consult the LitCharts How to Cite Your Sources guide for more resources.

Chicago Manual of Style Citation Guide

Some call The Chicago Manual of Style , which was first published in 1906, "the editors' Bible." The manual is now in its 17th edition, and is popular in the social sciences, historical journals, and some other fields in the humanities.

APA Citation Guide

According to the American Psychological Association, this guide was developed to aid reading comprehension, clarity of communication, and to reduce bias in language in the social and behavioral sciences. Its first full edition was published in 1952, and it is now in its sixth edition.

MLA Citation Guide

The Modern Language Association style is used most commonly within the liberal arts and humanities. The MLA Style Manual and Guide to Scholarly Publishing was first published in 1985 and (as of 2008) is in its third edition.

Any professional scholar will tell you that the best research papers are made in the revision stage. No matter how strong your research question or working thesis, it is not possible to write a truly outstanding paper without devoting energy to revision. These resources provide examples of revision exercises for the classroom, as well as tips for students working independently.

"The Art of Revision" (Univ. of Arizona)

This resource provides a wealth of information and suggestions for both students and teachers. There is a list of suggested exercises that teachers might use in class, along with a revision checklist that is useful for teachers and students alike.

"Script for Workshop on Revision" (Vanderbilt University)

Vanderbilt's guide for leading a 50-minute revision workshop can serve as a model for teachers who wish to guide students through the revision process during classtime.

"Revising Your Paper" (Univ. of Washington)

This detailed handout was designed for students who are beginning the revision process. It discusses different approaches and methods for revision, and also includes a detailed list of things students should look for while they revise.

"Revising Drafts" (UNC Writing Center)

This resource is designed for students and suggests things to look for during the revision process. It provides steps for the process and has a FAQ for students who have questions about why it is important to revise.

Conferencing with Writing Tutors and Instructors

No writer is so good that he or she can't benefit from meeting with instructors or peer tutors. These resources from university writing, learning, and communication centers provide suggestions for how to get the most out of these one-on-one meetings.

"Getting Feedback" (UNC Writing Center)

This very helpful resource talks about how to ask for feedback during the entire writing process. It contains possible questions that students might ask when developing an outline, during the revision process, and after the final draft has been graded.

"Prepare for Your Tutoring Session" (Otis College of Art and Design)

This guide from a university's student learning center contains a lot of helpful tips for getting the most out of working with a writing tutor.

"The Importance of Asking Your Professor" (Univ. of Waterloo)

This article from the university's Writing and Communication Centre's blog contains some suggestions for how and when to get help from professors and Teaching Assistants.

Once you've revised your first draft, you're well on your way to handing in a polished paper. These resources—each of them produced by writing professionals at colleges and universities—outline the steps required in order to produce a final draft. You'll find proofreading tips and checklists in text and video form.

"Developing a Final Draft of a Research Paper" (Univ. of Minnesota)

While this resource contains suggestions for revision, it also features a couple of helpful checklists for the last stages of completing a final draft.

Basic Final Draft Tips and Checklist (Univ. of Maryland-University College)

This short and accessible resource, part of UMUC's very thorough online guide to writing and research, contains a very basic checklist for students who are getting ready to turn in their final drafts.

Final Draft Checklist (Everett C.C.)

This is another accessible final draft checklist, appropriate for both high school and college students. It suggests reading your essay aloud at least once.

"How to Proofread Your Final Draft" (YouTube)

This video (approximately 5 minutes), produced by Eastern Washington University, gives students tips on proofreading final drafts.

"Proofreading Tips" (Georgia Southern-Armstrong)

This guide will help students learn how to spot common errors in their papers. It suggests focusing on content and editing for grammar and mechanics.

This final set of resources is intended specifically for high school and college instructors. It provides links to unit plans and classroom exercises that can help improve students' research and writing skills. You'll find resources that give an overview of the process, along with activities that focus on how to begin and how to carry out research.

"Research Paper Complete Resources Pack" (Teachers Pay Teachers)

This packet of assignments, rubrics, and other resources is designed for high school students. The resources in this packet are aligned to Common Core standards.

"Research Paper—Complete Unit" (Teachers Pay Teachers)

This packet of assignments, notes, PowerPoints, and other resources has a 4/4 rating with over 700 ratings. It is designed for high school teachers, but might also be useful to college instructors who work with freshmen.

"Teaching Students to Write Good Papers" (Yale)

This resource from Yale's Center for Teaching and Learning is designed for college instructors, and it includes links to appropriate activities and exercises.

"Research Paper Writing: An Overview" (CUNY Brooklyn)

CUNY Brooklyn offers this complete lesson plan for introducing students to research papers. It includes an accompanying set of PowerPoint slides.

"Lesson Plan: How to Begin Writing a Research Paper" (San Jose State Univ.)

This lesson plan is designed for students in the health sciences, so teachers will have to modify it for their own needs. It includes a breakdown of the brainstorming, topic selection, and research question process.

"Quantitative Techniques for Social Science Research" (Univ. of Pittsburgh)

This is a set of PowerPoint slides that can be used to introduce students to a variety of quantitative methods used in the social sciences.

- PDFs for all 136 Lit Terms we cover

- Downloads of 1931 LitCharts Lit Guides

- Teacher Editions for every Lit Guide

- Explanations and citation info for 40,744 quotes across 1931 books

- Downloadable (PDF) line-by-line translations of every Shakespeare play

Need something? Request a new guide .

How can we improve? Share feedback .

LitCharts is hiring!

Reference management. Clean and simple.

How to start your research paper [step-by-step guide]

1. Choose your topic

2. find information on your topic, 3. create a thesis statement, 4. create a research paper outline, 5. organize your notes, 6. write your introduction, 7. write your first draft of the body, 9. write your conclusion, 10. revise again, edit, and proofread, frequently asked questions about starting your research paper, related articles.

Research papers can be short or in-depth, but no matter what type of research paper, they all follow pretty much the same pattern and have the same structure .

A research paper is a paper that makes an argument about a topic based on research and analysis.

There will be some basic differences, but if you can write one type of research paper, you can write another. Below is a step-by-step guide to starting and completing your research paper.

Choose a topic that interests you. Writing your research paper will be so much more pleasant with a topic that you actually want to know more about. Your interest will show in the way you write and effort you put into the paper. Consider these issues when coming up with a topic:

- make sure your topic is not too broad

- narrow it down if you're using terms that are too general

Academic search engines are a great source to find background information on your topic. Your institution's library will most likely provide access to plenty of online research databases. Take a look at our guide on how to efficiently search online databases for academic research to learn how to gather all the information needed on your topic.

Tip: If you’re struggling with finding research, consider meeting with an academic librarian to help you come up with more balanced keywords.

If you’re struggling to find a topic for your thesis, take a look at our guide on how to come up with a thesis topic .

The thesis statement is one of the most important elements of any piece of academic writing. It can be defined as a very brief statement of what the main point or central message of your paper is. Our thesis statement guide will help you write an excellent thesis statement.

In the next step, you need to create your research paper outline . The outline is the skeleton of your research paper. Simply start by writing down your thesis and the main ideas you wish to present. This will likely change as your research progresses; therefore, do not worry about being too specific in the early stages of writing your outline.

Then, fill out your outline with the following components:

- the main ideas that you want to cover in the paper

- the types of evidence that you will use to support your argument

- quotes from secondary sources that you may want to use

Organizing all the information you have gathered according to your outline will help you later on in the writing process. Analyze your notes, check for accuracy, verify the information, and make sure you understand all the information you have gathered in a way that you can communicate your findings effectively.

Start with the introduction. It will set the direction of your paper and help you a lot as you write. Waiting to write it at the end can leave you with a poorly written setup to an otherwise well-written paper.

The body of your paper argues, explains or describes your topic. Start with the first topic from your outline. Ideally, you have organized your notes in a way that you can work through your research paper outline and have all the notes ready.

After your first draft, take some time to check the paper for content errors. Rearrange ideas, make changes and check if the order of your paragraphs makes sense. At this point, it is helpful to re-read the research paper guidelines and make sure you have followed the format requirements. You can also use free grammar and proof reading checkers such as Grammarly .

Tip: Consider reading your paper from back to front when you undertake your initial revision. This will help you ensure that your argument and organization are sound.

Write your conclusion last and avoid including any new information that has not already been presented in the body of the paper. Your conclusion should wrap up your paper and show that your research question has been answered.

Allow a few days to pass after you finished writing the final draft of your research paper, and then start making your final corrections. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill gives some great advice here on how to revise, edit, and proofread your paper.

Tip: Take a break from your paper before you start your final revisions. Then, you’ll be able to approach your paper with fresh eyes.

As part of your final revision, be sure to check that you’ve cited everything correctly and that you have a full bibliography. Use a reference manager like Paperpile to organize your research and to create accurate citations.

The first step to start writing a research paper is to choose a topic. Make sure your topic is not too broad; narrow it down if you're using terms that are too general.

The format of your research paper will vary depending on the journal you submit to. Make sure to check first which citation style does the journal follow, in order to format your paper accordingly. Check Getting started with your research paper outline to have an idea of what a research paper looks like.

The last step of your research paper should be proofreading. Allow a few days to pass after you finished writing the final draft of your research paper, and then start making your final corrections. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill gives some great advice here on how to revise, edit and proofread your paper.

There are plenty of software you can use to write a research paper. We recommend our own citation software, Paperpile , as well as grammar and proof reading checkers such as Grammarly .

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

- Research Papers

How to Write a Research Paper

Last Updated: February 18, 2024 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by Chris Hadley, PhD . Chris Hadley, PhD is part of the wikiHow team and works on content strategy and data and analytics. Chris Hadley earned his PhD in Cognitive Psychology from UCLA in 2006. Chris' academic research has been published in numerous scientific journals. There are 14 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 4,188,977 times.

Whether you’re in a history, literature, or science class, you’ll probably have to write a research paper at some point. It may seem daunting when you’re just starting out, but staying organized and budgeting your time can make the process a breeze. Research your topic, find reliable sources, and come up with a working thesis. Then create an outline and start drafting your paper. Be sure to leave plenty of time to make revisions, as editing is essential if you want to hand in your best work!

Sample Research Papers and Outlines

Researching Your Topic

- For instance, you might start with a general subject, like British decorative arts. Then, as you read, you home in on transferware and pottery. Ultimately, you focus on 1 potter in the 1780s who invented a way to mass-produce patterned tableware.

Tip: If you need to analyze a piece of literature, your task is to pull the work apart into literary elements and explain how the author uses those parts to make their point.

- Authoritative, credible sources include scholarly articles (especially those other authors reference), government websites, scientific studies, and reputable news bureaus. Additionally, check your sources' dates, and make sure the information you gather is up to date.

- Evaluate how other scholars have approached your topic. Identify authoritative sources or works that are accepted as the most important accounts of the subject matter. Additionally, look for debates among scholars, and ask yourself who presents the strongest evidence for their case. [3] X Trustworthy Source Purdue Online Writing Lab Trusted resource for writing and citation guidelines Go to source

- You’ll most likely need to include a bibliography or works cited page, so keep your sources organized. List your sources, format them according to your assigned style guide (such as MLA or Chicago ), and write 2 or 3 summary sentences below each one. [4] X Research source

- Imagine you’re a lawyer in a trial and are presenting a case to a jury. Think of your readers as the jurors; your opening statement is your thesis and you’ll present evidence to the jury to make your case.

- A thesis should be specific rather than vague, such as: “Josiah Spode’s improved formula for bone china enabled the mass production of transfer-printed wares, which expanded the global market for British pottery.”

Drafting Your Essay

- Your outline is your paper’s skeleton. After making the outline, all you’ll need to do is fill in the details.

- For easy reference, include your sources where they fit into your outline, like this: III. Spode vs. Wedgewood on Mass Production A. Spode: Perfected chemical formula with aims for fast production and distribution (Travis, 2002, 43) B. Wedgewood: Courted high-priced luxury market; lower emphasis on mass production (Himmelweit, 2001, 71) C. Therefore: Wedgewood, unlike Spode, delayed the expansion of the pottery market.

- For instance, your opening line could be, “Overlooked in the present, manufacturers of British pottery in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries played crucial roles in England’s Industrial Revolution.”

- After presenting your thesis, lay out your evidence, like this: “An examination of Spode’s innovative production and distribution techniques will demonstrate the importance of his contributions to the industry and Industrial Revolution at large.”

Tip: Some people prefer to write the introduction first and use it to structure the rest of the paper. However, others like to write the body, then fill in the introduction. Do whichever seems natural to you. If you write the intro first, keep in mind you can tweak it later to reflect your finished paper’s layout.

- After setting the context, you'd include a section on Josiah Spode’s company and what he did to make pottery easier to manufacture and distribute.

- Next, discuss how targeting middle class consumers increased demand and expanded the pottery industry globally.

- Then, you could explain how Spode differed from competitors like Wedgewood, who continued to court aristocratic consumers instead of expanding the market to the middle class.

- The right number of sections or paragraphs depends on your assignment. In general, shoot for 3 to 5, but check your prompt for your assigned length.

- If you bring up a counterargument, make sure it’s a strong claim that’s worth entertaining instead of ones that's weak and easily dismissed.

- Suppose, for instance, you’re arguing for the benefits of adding fluoride to toothpaste and city water. You could bring up a study that suggested fluoride produced harmful health effects, then explain how its testing methods were flawed.

- Sum up your argument, but don’t simply rewrite your introduction using slightly different wording. To make your conclusion more memorable, you could also connect your thesis to a broader topic or theme to make it more relatable to your reader.

- For example, if you’ve discussed the role of nationalism in World War I, you could conclude by mentioning nationalism’s reemergence in contemporary foreign affairs.

Revising Your Paper

- This is also a great opportunity to make sure your paper fulfills the parameters of the assignment and answers the prompt!

- It’s a good idea to put your essay aside for a few hours (or overnight, if you have time). That way, you can start editing it with fresh eyes.

Tip: Try to give yourself at least 2 or 3 days to revise your paper. It may be tempting to simply give your paper a quick read and use the spell-checker to make edits. However, revising your paper properly is more in-depth.

- The passive voice, such as “The door was opened by me,” feels hesitant and wordy. On the other hand, the active voice, or “I opened the door,” feels strong and concise.

- Each word in your paper should do a specific job. Try to avoid including extra words just to fill up blank space on a page or sound fancy.

- For instance, “The author uses pathos to appeal to readers’ emotions” is better than “The author utilizes pathos to make an appeal to the emotional core of those who read the passage.”

- Read your essay out loud to help ensure you catch every error. As you read, check for flow as well and, if necessary, tweak any spots that sound awkward. [13] X Trustworthy Source University of North Carolina Writing Center UNC's on-campus and online instructional service that provides assistance to students, faculty, and others during the writing process Go to source

- It’s wise to get feedback from one person who’s familiar with your topic and another who’s not. The person who knows about the topic can help ensure you’ve nailed all the details. The person who’s unfamiliar with the topic can help make sure your writing is clear and easy to understand.

Community Q&A

- Remember that your topic and thesis should be as specific as possible. Thanks Helpful 5 Not Helpful 0

- Researching, outlining, drafting, and revising are all important steps, so do your best to budget your time wisely. Try to avoid waiting until the last minute to write your paper. Thanks Helpful 6 Not Helpful 2

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/assignments/planresearchpaper/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/evaluating-print-sources/

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/conducting_research/research_overview/index.html

- ↑ https://poorvucenter.yale.edu/writing/graduate-writing-lab/writing-through-graduate-school/working-sources

- ↑ https://opentextbc.ca/writingforsuccess/chapter/chapter-5-putting-the-pieces-together-with-a-thesis-statement/

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/the_writing_process/developing_an_outline/index.html

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/introductions/

- ↑ https://academicguides.waldenu.edu/writingcenter/writingprocess/counterarguments

- ↑ https://writingcenter.fas.harvard.edu/pages/ending-essay-conclusions

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/revising-drafts/

- ↑ https://academicguides.waldenu.edu/formandstyle/writing/scholarlyvoice/activepassive

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/editing-and-proofreading/

- ↑ https://writingcenter.unc.edu/tips-and-tools/reading-aloud/

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/general_writing/the_writing_process/proofreading/index.html

About This Article

To write a research paper, start by researching your topic at the library, online, or using an academic database. As you conduct your research and take notes, zero in on a specific topic that you want to write about and create a 1-2 sentence thesis to state the focus of your paper. Then, create an outline that includes an introduction, 3 to 5 body paragraphs to present your arguments, and a conclusion to sum up your main points. Once you have your paper's structure organized, draft your paragraphs, focusing on 1 argument per paragraph. Use the information you found through your research to back up your claims and prove your thesis statement. Finally, proofread and revise your content until it's polished and ready to submit. For more information on researching and citing sources, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Private And Discrete

Aug 2, 2020

Did this article help you?

Jan 3, 2018

Oct 29, 2016

Maronicha Lyles

Jul 24, 2016

Maxwell Ansah

Nov 22, 2019

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

How to Write a Research Paper

If you already have a headache trying to understand what research paper is all about, we have created an ultimate guide for you on how to write a research paper. You will find all the answers to your questions regarding structure, planning, doing investigation, finding the topic that appeals to you. Plus, you will find out the secret to an excellent paper. Are you at the edge of your seat? Let us start with the basics then.

- What is a Research Paper

- Reasons for Writing a Research Paper

- Report Papers and Thesis Papers

- How to Start a Research Paper

- How to Choose a Topic for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Proposal for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Plan

- How to Do Research

- How to Write an Outline for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Thesis Statement for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Paper Rough Draft

- How to Write an Introduction for a Research Paper

- How to Write a Body of a Research Paper

- How to Write a Conclusion for a Research Paper

- How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper

- How to Revise and Edit a Research Paper

- How to Write a Bibliography for a Research Paper

- What Makes a Good Research Paper

Research Paper Writing Services

What is a research paper.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

You probably know the saying ‘the devil is not as black as he is painted’. This particular saying is absolutely true when it comes to writing a research paper. Your feet are cold even with the thought of this assignment. You have heard terrifying stories from older students. You have never done this before, so certainly you are scared. What is a research paper? How should I start? What are all these requirements about?

Luckily, you have a friend in need. That is our writing service. First and foremost, let us clarify the definition. A research paper is a piece of academic writing that provides information about a particular topic that you’ve researched . In other words, you choose a topic: about historical events, the work of some artist, some social issues etc. Then you collect data on the given topic and analyze it. Finally, you put your analysis on paper. See, it is not as scary as it seems. If you are still having doubts, whether you can handle it yourself, we are here to help you. Our team of writers can help you choose the topic, or give you advice on how to plan your work, or how to start, or craft a paper for you. Just contact us 24/7 and see everything yourself.

5 Reasons for Writing a Research Paper

Why should I spend my time writing some academic paper? What is the use of it? Is not some practical knowledge more important? The list of questions is endless when it comes to a research paper. That is why we have outlined 5 main reasons why writing a research paper is a good thing.

- You will learn how to organize your time

If you want to write a research paper, you will have to learn how to manage your time. This type of assignment cannot be done overnight. It requires careful planning and you will need to learn how to do it. Later, you will be able to use these time-managing skills in your personal life, so why not developing them?

- You will discover your writing skills

You cannot know something before you try it. This rule relates to writing as well. You cannot claim that you cannot write until you try it yourself. It will be really difficult at the beginning, but then the words will come to your head themselves.

- You will improve your analytical skills

Writing a research paper is all about investigation and analysis. You will need to collect data, examine and classify it. These skills are needed in modern life more than anything else is.

- You will gain confidence

Once you do your own research, it gives you the feeling of confidence in yourself. The reason is simple human brain likes solving puzzles and your assignment is just another puzzle to be solved.

- You will learn how to persuade the reader

When you write your paper, you should always remember that you are writing it for someone to read. Moreover, you want this someone to believe in your ideas. For this reason, you will have to learn different convincing methods and techniques. You will learn how to make your writing persuasive. In turns, you will be able to use these methods in real life.

What is the Difference between Report and Thesis Papers?

A common question is ‘what is the difference between a report paper and a thesis paper?’ The difference lies in the aim of these two assignments. While the former aims at presenting the information, the latter aims at providing your opinion on the matter. In other words, in a report paper you have to summarize your findings. In a thesis paper, you choose some issue and defend your point of view by persuading the reader. It is that simple.

A thesis paper is a more common assignment than a report paper. This task will help a professor to evaluate your analytical skills and skills to present your ideas logically. These skills are more important than just the ability to collect and summarize data.

How to Write a Research Paper Step by Step

Research comes from the French word rechercher , meaning “to seek out.” Writing a research paper requires you to seek out information about a subject, take a stand on it, and back it up with the opinions, ideas, and views of others. What results is a printed paper variously known as a term paper or library paper, usually between five and fifteen pages long—most instructors specify a minimum length—in which you present your views and findings on the chosen subject.

It is not a secret that the majority of students hate writing a research paper. The reason is simple it steals your time and energy. Not to mention, constant anxiety that you will not be able to meet the deadline or that you will forget about some academic requirement.

We will not lie to you; a research paper is a difficult assignment. You will have to spend a lot of time. You will need to read, to analyze, and to search for the material. You will probably be stuck sometimes. However, if you organize your work smart, you will gain something that is worth all the effort – knowledge, experience, and high grades.

The reason why many students fail writing a research paper is that nobody explained them how to start and how to plan their work. Luckily, you have found our writing service and we are ready to shed the light on this dark matter.

We have created a step by step guide for you on how to write a research paper. We will dwell upon the structure, the writing tips, the writing strategies as well as academic requirements. Read this whole article and you will see that you can handle writing this assignment and our team of writers is here to assist you.

How to Start a Research Paper?

It all starts with the assignment. Your professor gives you the task. It may be either some general issue or specific topic to write about. Your assignment is your first guide to success. If you understand what you need to do according to the assignment, you are on the road to high results. Do not be scared to clarify your task if you need to. There is nothing wrong in asking a question if you want to do something right. You can ask your professor or you can ask our writers who know a thing or two in academic writing.

It is essential to understand the assignment. A good beginning makes a good ending, so start smart.

Learn how to start a research paper .

Choosing a Topic for a Research Paper

We have already mentioned that it is not enough to do great research. You need to persuade the reader that you have made some great research. What convinces better that an eye-catching topic? That is why it is important to understand how to choose a topic for a research paper.

First, you need to delimit the general idea to a more specific one. Secondly, you need to find what makes this topic interesting for you and for the academia. Finally, you need to refine you topic. Remember, it is not something you will do in one day. You can be reshaping your topic throughout your whole writing process. Still, reshaping not changing it completely. That is why keep in your head one main idea: your topic should be precise and compelling .

Learn how to choose a topic for a research paper .

How to Write a Proposal for a Research Paper?

If you do not know what a proposal is, let us explain it to you. A proposal should answer three main questions:

- What is the main aim of your investigation?

- Why is your investigation important?

- How are you going to achieve the results?

In other words, proposal should show why your topic is interesting and how you are going to prove it. As to writing requirements, they may differ. That is why make sure you find out all the details at your department. You can ask your departmental administrator or find information online at department’s site. It is crucial to follow all the administrative requirements, as it will influence your grade.

Learn how to write a proposal for a research paper .

How to Write a Research Plan?

The next step is writing a plan. You have already decided on the main issues, you have chosen the bibliography, and you have clarified the methods. Here comes the planning. If you want to avoid writer’s block, you have to structure you work. Discuss your strategies and ideas with your instructor. Think thoroughly why you need to present some data and ideas first and others second. Remember that there are basic structure elements that your research paper should include:

- Thesis Statement

- Introduction

- Bibliography

You should keep in mind this skeleton when planning your work. This will keep your mind sharp and your ideas will flow logically.

Learn how to write a research plan .

How to Do Research?

Your research will include three stages: collecting data, reading and analyzing it, and writing itself.

First, you need to collect all the material that you will need for you investigation: films, documents, surveys, interviews, and others. Secondly, you will have to read and analyze. This step is tricky, as you need to do this part smart. It is not enough just to read, as you cannot keep in mind all the information. It is essential that you make notes and write down your ideas while analyzing some data. When you get down to the stage number three, writing itself, you will already have the main ideas written on your notes. Plus, remember to jot down the reference details. You will then appreciate this trick when you will have to write the bibliography.

If you do your research this way, it will be much easier for you to write the paper. You will already have blocks of your ideas written down and you will just need to add some material and refine your paper.

Learn how to do research .

How to Write an Outline for a Research Paper?

To make your paper well organized you need to write an outline. Your outline will serve as your guiding star through the writing process. With a great outline you will not get sidetracked, because you will have a structured plan to follow. Both you and the reader will benefit from your outline. You present your ideas logically and you make your writing coherent according to your plan. As a result, this outline guides the reader through your paper and the reader enjoys the way you demonstrate your ideas.

Learn how to write an outline for a research paper . See research paper outline examples .

How to Write a Thesis Statement for a Research Paper?

Briefly, the thesis is the main argument of your research paper. It should be precise, convincing and logical. Your thesis statement should include your point of view supported by evidence or logic. Still, remember it should be precise. You should not beat around the bush, or provide all the possible evidence you have found. It is usually a single sentence that shows your argument. In on sentence you should make a claim, explain why it significant and convince the reader that your point of view is important.

Learn how to write a thesis statement for a research paper . See research paper thesis statement examples .

Should I Write a Rough Draft for a Research Paper?

Do you know any writer who put their ideas on paper, then never edited them and just published? Probably, no writer did so. Writing a research paper is no exception. It is impossible to cope with this assignment without writing a rough draft.

Your draft will help you understand what you need to polish to make your paper perfect. All the requirements, academic standards make it difficult to do everything flawlessly at the first attempt. Make sure you know all the formatting requirements: margins, words quantity, reference requirements, formatting styles etc.

Learn how to write a rough draft for a research paper .

How to Write an Introduction for a Research Paper?

Let us make it more vivid for you. We have narrowed down the tips on writing an introduction to the three main ones:

- Include your thesis in your introduction

Remember to include the thesis statement in your introduction. Usually, it goes at the end of the first paragraph.

- Present the main ideas of the body

You should tell the main topics you are going to discuss in the main body. For this reason, before writing this part of introduction, make sure you know what is your main body is going to be about. It should include your main ideas.

- Polish your thesis and introduction

When you finish the main body of your paper, come back to the thesis statement and introduction. Restate something if needed. Just make it perfect; because introduction is like the trailer to your paper, it should make the reader want to read the whole piece.

Learn how to write an introduction for a research paper . See research paper introduction examples .

How to Write a Body of a Research Paper?

A body is the main part of your research paper. In this part, you will include all the needed evidence; you will provide the examples and support your argument.

It is important to structure your paragraphs thoroughly. That is to say, topic sentence and the evidence supporting the topic. Stay focused and do not be sidetracked. You have your outline, so follow it.

Here are the main tips to keep in head when writing a body of a research paper:

- Let the ideas flow logically

- Include only relevant information

- Provide the evidence

- Structure the paragraphs

- Make the coherent transition from one paragraph to another

See? When it is all structured, it is not as scary as it seemed at the beginning. Still, if you have doubts, you can always ask our writers for help.

Learn how to write a body of a research paper . See research paper transition examples .

How to Write a Conclusion for a Research Paper?

Writing a good conclusion is important as writing any other part of the paper. Remember that conclusion is not a summary of what you have mentioned before. A good conclusion should include your last strong statement.

If you have written everything according to the plan, the reader already knows why your investigation is important. The reader has already seen the evidence. The only thing left is a strong concluding thought that will organize all your findings.

Never include any new information in conclusion. You need to conclude, not to start a new discussion.

Learn how to write a conclusion for a research paper .

How to Write an Abstract for a Research Paper?

An abstract is a brief summary of your paper, usually 100-200 words. You should provide the main gist of your paper in this short summary. An abstract can be informative, descriptive or proposal. Depending on the type of abstract, you need to write, the requirements will differ.

To write an informative abstract you have to provide the summary of the whole paper. Informative summary. In other words, you need to tell about the main points of your work, the methods used, the results and the conclusion of your research.

To write a descriptive abstract you will not have to provide any summery. You should write a short teaser of your paper. That is to say, you need to write an overview of your paper. The aim of a descriptive abstract is to interest the reader.

Finally, to write a proposal abstract you will need to write the basic summary as for the informative abstract. However, the difference is the following: you aim at persuading someone to let you write on the topic. That is why, a proposal abstract should present your topic as the one worth investigating.

Learn how to write an abstract for a research paper .

Should I Revise and Edit a Research Paper?

Revising and editing your paper is essential if you want to get high grades. Let us help you revise your paper smart:

- Check your paper for spelling and grammar mistakes

- Sharpen the vocabulary

- Make sure there are no slang words in your paper

- Examine your paper in terms of structure

- Compare your topic, thesis statement to the whole piece

- Check your paper for plagiarism

If you need assistance with proofreading and editing your paper, you can turn to the professional editors at our service. They will help you polish your paper to perfection.

Learn how to revise and edit a research paper .

How to Write a Bibliography for a Research Paper?

First, let us make it clear that bibliography and works cited are two different things. Works cited are those that you cited in your paper. Bibliography should include all the materials you used to do your research. Still, remember that bibliography requirements differ depending on the formatting style of your paper. For this reason, make sure you ask you professor all the requirements you need to meet to avoid any misunderstanding.

Learn how to write a bibliography for a research paper .

The Key Secret to a Good Research Paper

Now when you know all the stages of writing a research paper, you are ready to find the key to a good research paper:

- Choose the topic that really interests you

- Make the topic interesting for you even if it is not at the beginning

- Follow the step by step guide and do not get sidetracked

- Be persistent and believe in yourself

- Really do research and write your paper from scratch

- Learn the convincing writing techniques and use them

- Follow the requirements of your assignment

- Ask for help if needed from real professionals

Feeling more confident about your paper now? We are sure you do. Still, if you need help, you can always rely on us 24/7.

We hope we have made writing a research paper much easier for you. We realize that it requires lots of time and energy. We believe when you say that you cannot handle it anymore. For this reason, we have been helping students like you for years. Our professional team of writers is ready to tackle any challenge.

All our authors are experienced writers crafting excellent academic papers. We help students meet the deadline and get the top grades they want. You can see everything yourself. All you need to do is to place your order online and we will contact you. Writing a research paper with us is truly easy, so why do not you check it yourself?

Additional Resources for Research Paper Writing:

- Anthropology Research

- Career Research

- Communication Research

- Criminal Justice Research

- Health Research

- Political Science Research

- Psychology Research

- Sociology Research

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

Home / Guides / Writing Guides / Paper Types / How to Write a Research Paper

How to Write a Research Paper

Research papers are a requirement for most college courses, so knowing how to write a research paper is important. These in-depth pieces of academic writing can seem pretty daunting, but there’s no need to panic. When broken down into its key components, writing your paper should be a manageable and, dare we say it, enjoyable task.

We’re going to look at the required elements of a paper in detail, and you might also find this webpage to be a useful reference .

Guide Overview

- What is a research paper?

- How to start a research paper

- Get clear instructions

- Brainstorm ideas

- Choose a topic

- Outline your outline

- Make friends with your librarian

- Find quality sources

- Understand your topic

- A detailed outline

- Keep it factual

- Finalize your thesis statement

- Think about format

- Cite, cite and cite

- The editing process

- Final checks

What is a Research Paper?

A research paper is more than just an extra long essay or encyclopedic regurgitation of facts and figures. The aim of this task is to combine in-depth study of a particular topic with critical thinking and evaluation by the student—that’s you!

There are two main types of research paper: argumentative and analytical.

Argumentative — takes a stance on a particular topic right from the start, with the aim of persuading the reader of the validity of the argument. These are best suited to topics that are debatable or controversial.

Analytical — takes no firm stance on a topic initially. Instead it asks a question and should come to an answer through the evaluation of source material. As its name suggests, the aim is to analyze the source material and offer a fresh perspective on the results.

If you wish to further your understanding, you can learn more here .

A required word count (think thousands!) can make writing that paper seem like an insurmountable task. Don’t worry! Our step-by-step guide will help you write that killer paper with confidence.

How to Start a Research Paper

Don’t rush ahead. Taking care during the planning and preparation stage will save time and hassle later.

Get Clear Instructions

Your lecturer or professor is your biggest ally—after all, they want you to do well. Make sure you get clear guidance from them on both the required format and preferred topics. In some cases, your tutor will assign a topic, or give you a set list to choose from. Often, however, you’ll be expected to select a suitable topic for yourself.

Having a research paper example to look at can also be useful for first-timers, so ask your tutor to supply you with one.

Brainstorm Ideas

Brainstorming research paper ideas is the first step to selecting a topic—and there are various methods you can use to brainstorm, including clustering (also known as mind mapping). Think about the research paper topics that interest you, and identify topics you have a strong opinion on.

Choose a Topic

Once you have a list of potential research paper topics, narrow them down by considering your academic strengths and ‘gaps in the market,’ e.g., don’t choose a common topic that’s been written about many times before. While you want your topic to be fresh and interesting, you also need to ensure there’s enough material available for you to work with. Similarly, while you shouldn’t go for easy research paper topics just for the sake of giving yourself less work, you do need to choose a topic that you feel confident you can do justice to.

Outline Your Outline

It might not be possible to form a full research paper outline until you’ve done some information gathering, but you can think about your overall aim; basically what you want to show and how you’re going to show it. Now’s also a good time to consider your thesis statement, although this might change as you delve into your source material deeper.

Researching the Research

Now it’s time to knuckle down and dig out all the information that’s relevant to your topic. Here are some tips.

Make Friends With Your Librarian

While lots of information gathering can be carried out online from anywhere, there’s still a place for old-fashioned study sessions in the library. A good librarian can help you to locate sources quickly and easily, and might even make suggestions that you hadn’t thought of. They’re great at helping you study and research, but probably can’t save you the best desk by the window.

Find Quality Sources

Not all sources are created equal, so make sure that you’re referring to reputable, reliable information. Examples of sources could include books, magazine articles, scholarly articles, reputable websites, databases and journals. Keywords relating to your topic can help you in your search.

As you search, you should begin to compile a list of references. This will make it much easier later when you are ready to build your paper’s bibliography. Keeping clear notes detailing any sources that you use will help you to avoid accidentally plagiarizing someone else’s work or ideas.

Understand Your Topic

Simply regurgitating facts and figures won’t make for an interesting paper. It’s essential that you fully understand your topic so you can come across as an authority on the subject and present your own ideas on it. You should read around your topic as widely as you can, before narrowing your area of interest for your paper, and critically analyzing your findings.

A Detailed Outline

Once you’ve got a firm grip on your subject and the source material available to you, formulate a detailed outline, including your thesis statement and how you are going to support it. The structure of your paper will depend on the subject type—ask a tutor for a research paper outline example if you’re unsure.

Get Writing!

If you’ve fully understood your topic and gathered quality source materials, bringing it all together should actually be the easy part!

Keep it Factual

There’s no place for sloppy writing in this kind of academic task, so keep your language simple and clear, and your points critical and succinct. The creative part is finding innovative angles and new insights on the topic to make your paper interesting.

Don’t forget about our verb , preposition , and adverb pages. You may find useful information to help with your writing!

Finalize Your Thesis Statement

You should now be in a position to finalize your thesis statement, showing clearly what your paper will show, answer or prove. This should usually be a one or two sentence statement; however, it’s the core idea of your paper, and every insight that you include should be relevant to it. Remember, a thesis statement is not merely a summary of your findings. It should present an argument or perspective that the rest of your paper aims to support.

Think About Format

The required style of your research paper format will usually depend on your subject area. For example, APA format is normally used for social science subjects, while MLA style is most commonly used for liberal arts and humanities. Still, there are thousands of more styles . Your tutor should be able to give you clear guidance on how to format your paper, how to structure it, and what elements it should include. Make sure that you follow their instruction. If possible, ask to see a sample research paper in the required format.

Cite, Cite and Cite

As all research paper topics invariably involve referring to other people’s work, it’s vital that you know how to properly cite your sources to avoid unintentional plagiarism. Whether you’re paraphrasing (putting someone else’s ideas into your own words) or directly quoting, the original source needs to be referenced. What style of citation formatting you use will depend on the requirements of your instructor, with common styles including APA and MLA format , which consist of in-text citations (short citations within the text, enclosed with parentheses) and a reference/works cited list.

The Editing Process