Lost your password?

Create an account

Pohutukawa-flame of the north

Whether providing shade for a summer picnic, standing sentinel on a crumbling cliff or splashing Christmas crimson along garden edge, street or shoreline, the pohutukawa is one of the trees New Zealanders hold in greatest affection. Its grizzled bark and joyous blooms speak to us not just of the enduring qualities of the tree, but of the land itself.

Written by Jo Hardy, Roger Blackley and Warren Judd Photographed by Kennedy Warne

Without a doubt, it is one of the top ten flowering trees in the world,” declares Graeme Platt, the native plant impresario. “In the north, a beach isn’t a beach without pohutukawa trees around it. Overseas visitors who saw pohutukawa were always wanting seed from me when I had the nursery. The tree is doing well in Seattle, California and Australia, and it is almost a weed along the coast near Capetown.”

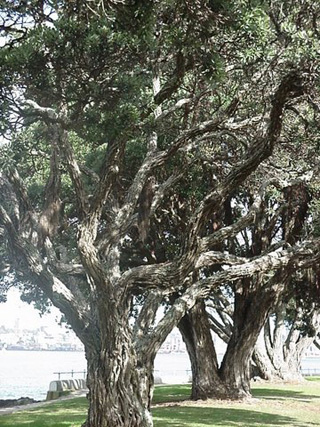

Small wonder that it is so widely appreciated. Even apart from its smother of spectacular crimson blossoms in summer, the pohutukawa is a tree of outstanding character. Rough roots, thicker than the tentacles of Nemo’s squid, grope and grasp their way down cliffs. They seem more like misdirected branches than delicate tendrils seeking nutrients. Crooked, gnarled, furrowed limbs span ten or more metres, often cantilevered out from sheer cliffs. In between, roots and branches may form a temporary confederation to produce a squat trunk, but as often as not branches just spring out of a plot of ground.

The whole tortured frame looks to have endured a thousand years of adversity, even when it has seen only fifty summers. Even the leathery leaves, downy white below, satin grey-green above, seem to have been honed by hardship.

The pohutukawa is a member of the huge myrtle family, which includes among its 3000 species eucalypts, guavas, feijoas, bottlebrushes, manuka, kanuka and swamp maire. In the New Zealand biological region two species of pohutukawa occur naturally: the common mainland tree Metrosideros excelsa and Metrosideros kermadecensis, a pohutukawa endemic to Raoul Island—a thousand kilometres to the north. In the same genus are several species of rata, both trees and climbers. The northern and southern rata sometimes start off their lives as climbers, then eventually throttle their support trees to become forest giants in their own right.

Pohutukawa seem to suffer from a fundamental confusion about the distinction between roots and branches. Not only do the roots resemble branches, but in many trees the branches sprout great beards of aerial roots that rarely reach the ground. When they do contact dirt, they certainly can attach, and mat and thicken into a walking stick for the branch. Even when a normal branch sags to the ground, it habitually establishes massive roots too. Perhaps this identity crisis arises from the fact that many sprawling pohutukawa trees are more horizontal than vertical, and the ground they inhabit is often more vertical than horizontal! For this is a tree that can survive on the salty edge of the land where no other can, clinging precariously to impossible rocks and cliffs, a tree that lends strength to the land in its eternal wrestle against the onslaught of the waves. A tree indeed.

Unfortunately, the pohutukawa is no longer flourishing with its ancient vigour along the coastlines of Aotearoa. To be sure, those glorious flowers still brighten northern shores each Christmas, but there aren’t anywhere near as many as there used to be. Principal culprit in their demise is the rapacious Australian brushtail possum, which feasts on them and their rata cousins as if they were floral caviar. But Graeme Platt, always an independent thinker, reckons that the possums don’t deserve as much blame as they are receiving. Human abuse, an inability to germinate among exotic weeds, lack of adequate nutrition in the areas the plant is now found in, and shortage of rain through felling too much Northland forest in earlier times—all these factors contribute to the pohutukawa’s decline, he says.

Studies conducted in the late 1980s by the Forest Research Institute on 197 stands of pohutukawa located around the northern coast between East Cape and Kawhia found that Northland trees were generally in poorest condition. Worst of all were those along the eastern shore of Kawau Island, where rotting trees littered the ground. More alarming than the health report was the age distribution of the stands: 80 per cent were classed as old or mature. Only 27 stands consisted mainly of young trees.

Everyone agrees that the pohutukawa remaining today are just a shadow of the forests that once existed around many northern coasts, but now are to be found only on a handful of islands, particularly Rangitoto and Mayor Island. Clearing of land by both Maori and Pakeha has been to blame, and the situation has been exacerbated by two peculiarities of the tree. First, pohutukawa are extraordinarily susceptible to fire, a favoured weapon of land clearers. Even a grass fire around the base will kill a mature tree. Second, seedlings are unable to regenerate in the presence of competing vegetation such as kikuyu grass. Young trees do well on bare ground, such as roadside cuttings, but there they are often at the mercy of trampling and browsing cattle and goats.

Brightest spot in human dealings with pohutukawa has been planting of the species south of its normal range. Pohutukawa is a latitude 38 tree (like kauri and mangrove) that naturally only occurs north of Kawhia and Gisborne. But as long as the young tree is not exposed to frost, it will grow much further south, so it is now a familiar tree in Wellington and in the west and north of the South Island.

Troubled by the Forest Research Institute’s findings, the Department of Conservation was able to enlist the support of forestry company Carter Holt Harvey in establishing the Project Crimson Trust in 1990. The object of the Trust is the betterment of pohutukawa (and very recently its cousins the rata), by protecting existing trees and planting more. Several enthusiastic volunteers devote much of their time to running Project Crimson. One is Ted Wilson, a retired businessman and life member of the Auckland Carnation, Gerbera and Geranium Society—a reflection of his lifelong enthusiasm for breeding and showing flowers.

“Carter Holt provides the bulk of our funds,” Ted explains. “We use that money to have pohutukawa grown, and we then donate young trees to various groups who approach us seeking trees. We don’t provide trees for planting on private land, nor do we support plantings south of the tree’s natural area, but we give trees to DOC, local bodies, schools, Forest and Bird, and community groups. This year we are supporting between 40 and 50 planting projects, as well as making contributions to research that should benefit the trees.” The research includes attempts to chemically synthesise the scent of Dactylanthus taylorii (the wood rose) another favourite possum food, in the hope that it might be useful for attracting possums to baits, and a study into why only 10 per cent of pohutukawa seed is fertile.

Ted not only does much of the organising of Project Crimson activities, but visits sites where pohutukawa are debilitated, collects seed, distributes it to nurseries and organises the distribution of plants. Care is taken to collect seed from the areas where the trees are to be planted, and the young trees are then returned to those same areas a couple of years later. “We’ve found that the larger the plants, the better they survive when planted,” Ted says, “but transporting big plants is expensive, so we try and grow them near where they will be used. We are having trees grown from Whakatane to Te Paki.”

In Auckland, trees are grown for Project Crimson by the Crippled Children’s Society Nursery in Mt Albert and at Paremoremo Prison. Joe Watt of the prison staff says that the pohutukawa growing project has been very successful. “Last year we grew 16,000 plants from 19 different sites. A lot of the inmates haven’t had this sort of experience in the past, and they develop a bit of ownership pride and interest in the project. One whose interest was sparked by the work has gone on to do a horticulture programme with Massey University.”

Project Crimson has supplied 40-50,000 pohutukawa for planting over the last few years. A major current project is the erection of a 2.5 km possum-proof fence across the Cape Brett peninsula, to be followed by extermination of all possums on the peninsula and replanting of young pohutukawa to replace the ranks of dead and dying in the area.

Not only Project Crimson is concerned about the plight of pohutukawa. Terry Hatch, a nurseryman near Pukekohe who has developed a deep affection for native plants, commented that “a while back pohutukawa seemed to be getting chewed off everywhere, so I decided to grow a few.” That year he grew 23,000 plants and sold them all. With Graeme Platt, he has toured the North Island and taken cuttings from promising or unusual pohutukawa. Two that have proved good cultivars are an orange-flowering variety from behind the hotel at Te Kaha (and called “Te Kaha”) and “Vibrant,” from a tree at Tapu, north of Thames.

“When you look closely at the flowers of pohutukawa, not many really look that good. Very few plants possess the long stamens that we find attractive. From my observations, bees prefer plants with short stamens, so I hand pollinate plants with long stamens to get seed from them. I suspect that if pollination was left to bees, we’d end up with only short-stamen pohutukawa.”

In prehuman New Zealand, most pollination of pohutukawa was probably carried out by the abundant nectar-feeding birds and geckos, who may not share the bee’s preference for flowers with short stamens. Bats, too, apparently have a taste for pohutukawa nectar, and, on Little Barrier Island, roost in old pohutukawa.

“Pohutukawa seed has a most glorious fragrance,” Terry enthuses, “like richest, thick honey. It would make a wonderful perfume.” But it has a downside, too. “Put a sheet on the ground and tap the branches with a stick in April or May to collect seed, and stand clear! The seed is very fine and acts like itching powder. It takes a couple of washes to get it out of your clothes.”

For nearly four decades Mike Stuckey has been making pilgrimages each summer to the pohutukawa on Rangitoto—not to admire their beauty, but to harvest their bounty: honey. “It’s the whitest honey in the world, and has a very delicate flavour. Kids like it, and it’s very good for bottling where you don’t want the honey to overpower other flavours.

“Rangitoto has the only accessible pohutukawa forest in the country, and the honey we harvest would be better than 99 per cent pohutukawa. Twenty years ago we were getting between 11 and 20 tonnes of honey annually, depending on how heavy the flowering was. Slowly it declined until we were only getting four or five tonnes from the 200 or 300 hives we took down each summer, and it was barely worth the effort. Since the big 1080 [poison] drop there to kill possums a couple of years ago, we’ve recovered eight tonnes despite poor flowering. Before the drop, I’d go down, see all the buds, and always overestimate the crop, since the possums ate a lot of buds. Now I’m consistently underestimating it.”

Mike is sure that the oldest trees on the island are no more than 200 years old, and says most are much younger. “My mother went to the island in 1922, and said it was mostly bare rock. When we took her back in 1960, she couldn’t believe how much more vegetation there was, and most of that was pohutukawa. Unfortunately, it is unlikely that the pohutukawa forest there will last for too many centuries longer. Pohutukawa can colonise and survive in the harshest conditions—such as the lava fields of Rangitoto—but once established, falling leaves and rotting branches will form humus that less hardy plants can grow in, and the pohutukawa will be squeezed out.

Their successors are unlikely to be as splendid.

A Northland Perspective

The Pohutukawa was a cautionary tale in a Dunedin education. Nowhere to be seen—except in pictures of the far-fabled north, where oranges also grew—it was a subject, along with equally unfamiliar kauri and man‑groves, we were warned to avoid in choosing from the School Certificate English essay topics on offer.

Stick to what you know, they said.

The only tree I knew personally was a poor stunted oak in the fire station courtyard. Probably included in the original design by some optimistic institutional planner who hadn’t reckoned on the spit and polish zeal of the Fire Service, the oak was hacked back annually to its naked trunk.

When Christmas came around we Southerners were just as disenfranchised by the pohutukawa pictures on the determinedly New Zealand cards as we were by the snow and robins borrowed from the other side of the world.

Of all the Christmas symbols, only angels, pine needles and presents in their shiny wrappings seemed to belong to us, because, in those days, God was everywhere, pine forests were familiar from the drive over Three Mile Hill (where we had it on good authority the teddy bears’ picnic actually took place) and the prosperity which begat presents was safely enshrined in the Welfare State.

You don’t know how lucky you are, they said.

Today, from a Northland perspective, it is clear a different spirit stalks the land. Here no institutional planners hold sway for long, and trees are gods.

Prosperity only ever grazes the north in a series of booms, busts and promised bonanzas. Feasts and famines. One year champagne and famines. One year champagne and new dresses; the next home-made cards and being pleased to have bread and butter at the same time.

Beneficiaries, the last shreds of the Welfare State, are to be seen on Thursdays thronging those Northland towns still equipped with banks, while Letters to the Editor run hot with elderly critics who managed perfectly well in the Depression without the consolations of fast food and Lotto.

Supermarkets are open on Sundays, and mainstream Christian evangelism has given way to awareness of the need to respect, not homogenise, religious and cultural differences.

Today’s prevailing theology is of a secular ecological doomsday, with dolphins as its angels; a view to which all but the most diehard of herbicidal farmers subscribe.

Culture always evolves in tune with the demands of social change, and thus the pohutukawa has emerged as a transcendent multipurpose symbol: of Pakeha New Zealand identity after the cultural cringe, of the Maori spirituality inhabiting the land and of widespread environmental concern.

Pohutukawa pre-date people on this land. Here before the great migration, before Tasman, Cook, Father Christmas and all, they may even (if reports of Australian fossil evidence are to be believed) pre-date the chance that continental drift offered for Maui’s fish to swim away.

Written versions of creation stories speak of a warrior, Tawhaki, visiting the heavens on a quest. In the uppermost heaven he met Tama-i-waho, a being possessed of great powers, who caused Tawhaki to fall, and so perish at the far-off place where the sky hangs down. The next morning the blossoms of the pohutukawa were of a strange new colour produced by the blood of Tawhaki as he fell.

A mere thousand years ago, voyagers on the great Maori migration to Aotearoa saw their first pohutukawa flowers. Stories are told in the histories of more than one canoe of sacred red feathers (kura) carefully carried from the homeland. When the travellers saw brilliant splashes of pohutukawa flowering on the coastline they decided their old red feathers were but coals to Newcastle, and cast them into the sea. On reaching land and discovering the flaming abundance was made merely of flowers which drooped upon picking, they went to retrieve the precious red feathers, only to find them in the possession of one Mahina, who refused to give them back. The resultant phrase “te kura pae a Mahina” might signify “finders keepers,” but would seem more likely to point to the foolishness of throwing the baby out with the bathwater, or, indeed, of forgetting what is of value from the past in the mad rush to embrace the promise of the new.

In a thousand years of human occupation, pohukutawa have found use practically as medicine and in boatbuilding, symbolically in both Maori and Pakeha spiritual traditions, artistically in visual and literary images, customarily in the barbie-onthe-beach rituals of the Kiwi summer and ideologically in environmental crusades.

Although sucking the nectar of pohutukawa flowers has been recommended for sore throats, records of pohutukawa medicinal uses concentrate principally on the inner bark which, cut out where the rising sun strikes the tree, has been used in the form of an infusion to treat diarrhoea, dysentery and venereal disease, chewed as a sure cure for thrush, bound against wounds to stop bleeding and steeped in water as a mouthwash and gargle. Northlanders still pack it into dental cavities as a last-ditch folk remedy to kill the pain and, incidentally, the nerve of the tooth.

The 106-foot Stirlingshire, largest sailing ship ever built in New Zealand, was laid down on Great Barrier Island in 1840. Its kauri planks were fitted to massive, naturally curved pohutukawa ribs. The sinuous forms of iron-hard pohutukawa timber are still used in boatbuilding for angled keels, sterns and knees which require no shaping, and in contemporary sculpture and furniture making.

Among northern coastal tribes, particular pohutukawa became tapu because they were places where the bodies of the dead were hung, or because the placentae of children of note were placed in their branches.

For both Maori and those Pakeha who prefer more localised belief systems to European and Middle Eastern models, the ancient and weathered pohutukawa perched on the water’s edge at Te Reinga, on the point where two oceans meet, is the last leaping place of the spirits of the dead; gateway to the underworld and last stop before Hawaiki, the eternal spiritual homeland.

Some would have it that bushclad ridges rustle, grasses are mysteriously knotted and pohutukawa bloom the colour of blood along the pathways of the spirits as they travel north.

The fabled tree, with infrequent blossoms known as Te Pua o te Reinga or the flowers of spirit’s flight, is, by some accounts, 1200 years old—a natural bonsai, kept in trim by the inhospitality of the rock to which it clings and by the raging elements in that strange wild place where there is no horizon and where even I, raised in the south on teddy-bears’ picnics and Latin verbs, have seen an old woman walk into the setting sun without returning.

At Oihi Beach in the Bay of Islands in 1814, Samuel Marsden conducted a Christmas service against a backdrop of flowering pohutukawa. With the coincidence of its December flowering and its red blooms—a colour sacred in many cultures as a portent of blood, royalty, the sacraments, fertile ground, birth and the life force itself—its future as a symbol was assured. Even for those whose Christmas homage is paid merely to a secular summer holiday, typically celebrated at the beach, the pohutukawa is a presence at the feast, a launching pad for the kids as they swing out to splash into sparkling summer seas, and spreading shade for the Boxing Day picnic with sandwiches made from the leftover ham.

[Chapter Break]

Is there New Zealand poet who has not stained a page with the colour of pohutukawa, compact in its evocation of homeland, of childhood, holidays and of the mysteries of life lived on snakeless islands with borders no mere imaginary lines but the clean clear geographical edges of vast oceans?

A. R. D. Fairburn, in Memories of England, drew his image by negative definition: “No dragon’s blood breaking in crimson flowers,” and Peter Bland in Letters Home: I remember once she said—Our pohutukawa blossoms have the scent of salt and oranges. That’s what this rose smells of—not Surrey but her that summer on an Auckland beach.

There’s Allen Curnow in Spectacular Blossom where: “woody tumours burst in scarlet spray,” and Alan Mulgan in Aldebran and Other Verses: “When pohutukawa dips, red on our blue infinities.”

In Bruce Mason’s play The Pohutukawa Tree, the symbolic tree hanging over the porch was planted after a battle, “that its red flowers might be a sign of blood between Maori and Pakeha forever.”

In The End of the Golden Weather Mason describes the “territory of the heart we call childhood . . .”

The beach is fringed with pohutukawa trees, single and stunted in the gardens, spreading and noble on the cliffs and in the empty spaces by the foreshore. Tiny red coronets prick through the grey-green leaves. Bark, flower and leaf seem overlaid with smoke. The red is of a dying fire at dusk, the green faded and drab. Pain and age are in these gnarled forms, in bare roots, clutching at the earth, knotting on the cliff-face, in tortured branches, dark against the washed sky. Pain and age are in these gnarled forms, in bare roots, clutching at the earth, knotting on the cliff-face, in tortured branches, dark against the washed sky.

For Hone Tuwhare “pohutukawa bleed their short-lived brilliance” at Te Kaha, and in Lament he writes:

At dawn’s light I looked for you at land’s end where two oceans froth but you had gone without leaving a sign or a whispered message to the gnarled tree’s feet or the grass of the inscrutable rock face . . .

Even southern poets like James K. Baxter and Janet Frame sing their pohutukawa songs. Here is Baxter in A Takapuna Businessman Considers his Son’s Death in Korea:

… Muskets blazed

From the hunched snipers of pohutukawa

The day you stole my wallet and my car

And drove to Puhoi . . .

For Janet Frame, Christmas

is holiday blossom beach sea

is from me to you

is from you to me

is giving giving

in a torture of anxiety

panic of pohutukawa…

When I first came north I was warned that to pick pohutukawa flowers is bad luck. No-one can tell me why. My own superstitions, handed down from a long line of Cockney grandmothers, suggest there are always good reasons for these warnings which need to live on the popular imagination to preserve safety and survival against a day when no health or conservation departments exist to prescribe advice.

Perhaps the pohutukawa warning is a conservation measure or a reference to the tapu surrounding particular trees generalised over time and distance, or maybe it’s simple reverence for the sacred colour of blood.

The ghost I saw in the corner of the Maori reference section in the library may well have been a warning, too, against picking the metaphorical flowers of the north’s secret stories—an echo of “stick to what you know”.

What is clear from 20 years of painting the landscape in the north is that trees are people, too—the figures on the land. Macrocarpas are the big dark wizards; pines are the soldiered ranks of armies, pointed sticks at the ready; willows are the corps de ballet and totara the ragged boundary markers.

Pohutukawa are placentae, straight out of the herbal doctrine of signatures, connecting the blood beat of life to mother earth. Their art nouveau branches are a pantheist’s stained glass window frames, and their forgiving shapes a coastal draughtsperson’s godsend, hiding a multitude of sins at every headland’s edgy refusal to remain on a logical plane, swathing the points at which all lines should meet with trickery in more outrageous colours than anything mere pigment, poetry or perspective might achieve.

Hardy/McNeil

The Pointed Pohutukawa

It is hardly surprising that tree as striking as the pohutukawa should have commanded the attention of many New Zealand artists.

One of the tree’s earliest champions was Alfred Sharpe, an Englishman who emigrated to New Zealand in the 1850s. A pioneering conservationist, Sharpe was passionately interested in the fate of all indigenous trees, but the pohutukawa was a particular favourite—one which he considered an ideal street tree for Auckland’s boulevards.

Sharpe’s 1876 watercolour of an ancient pohutukawa, part of a sacred grove called Te Urutapu at the northern end of Auckland’s Takapuna Beach, is one of the most remarkable tree portraits in New Zealand art (above). The particular specimen he chose to immortalise was, in 1876, on fenced farmland grazed by wandering cattle, and Sharpe carefully described the stumps that indicated absent limbs. On an upper branch we can even make out a wasps’nest—evidence of the imported “vermin” which Sharpe repeatedly identified as a threat to New Zealand’s unique environment. In recent decades, Sharpe’s pohutukawa presided over the garden of the Mon Desir Hotel, where it had more to fear from wandering humans than it ever did from cattle.

While the inspiration for the picture springs from a long tradition of tree portraiture—especially the English tradition of depicting ancient oak trees—Sharpe combined the tight focus of the Pre-Raphaelite landscapes he saw as a youth with his appreciation of the unique flora of his adopted country. The result is a work with few parallels in colonial art, for Sharpe presents his pohutukawa not so much as a species but as an awesome individual.

Under pennames such as “Anti-vermin” and “Conservator,” Sharpe blasted the work of the acclimatisation societies—the groups responsible for introducing the possum, the rabbit and a host of other disasters, both animal and vegetable. Ironically, Sharpe later became an avid importer of pohutukawa into Australia. He desired the “giant myrtle of New Zealand” to grace the parks he was designing in New South Wales. Pohutukawa now line several Newcastle inner-city streets, and there are a number of splendid specimens planted by Sharpe in King Edward Park.

Many colonial artists, both resident and itinerant, depicted the astonishing transformation that overtakes the pohutukawa in December and January. The travelling artist and author Constance Gordon Cumming stayed with Sir George Grey at Kawau Island in January 1877, and made an evocative depiction of a flowering pohutukawa in Grey’s garden. In her book At Home in Fiji (1881), she described how “in its prime, each tree is one mass of glowing scarlet; and the effect of its flame-coloured branches overhanging the bright blue water, and dripping showers of fiery stamens in the sea or on the grass, is positively dazzling.”

Kennett Watkins played an important role in Auckland’s art world of the late 19th century, directing the first art school from 1879, and founding the New Zealand Art Students Association in 1883. Watkins’ huge oil paintings were considered major works in his own time, but have spent most of this century consigned to the storage racks.

His Legend of the Voyage to New Zealand was unanimously declared the “Picture of the Year” at the 1912 exhibition of the Auckland Society of Arts. The legend of the picture’s title is a story preserved in the traditions of two migration canoes, Tainui and Te Arawa, both of which first made landfall when the pohutukawa was in blossom. Both traditions record a similar story, of immigrants casting overboard their prized red-feather ornaments in the excitement of seeing the red-plumed foliage of Aotearoa, and of inevitable disillusionment. The traditions are also firm about the sometimes bloody rivalry between these two groups of immigrants, and the fact that Tainui arrived after Te Arawa. Yet Watkins’ painting presents the full “fleet” of six canoes gliding calmly across glistening waters, completely unscathed by the epic voyage across the Pacific (opposite).

Louis J. Steele was another history painter of the period, a close associate of Watkins and the teacher of Charles F. Goldie. Steele’s 1916 contribution was the ceremonial launching of a war canoe, a scene of human sacrifice viewed from the safe distance of a shady pohutukawa. Another Steele composition had Captain Cook meeting Maori chiefs, similarly framed by pohutukawa.

For Auckland-based painters of this period, the pohutukawa was a potent signifier of “the North.” Settlers had already appropriated the flowering pohutukawa to stand for Christmas. A 1902 painting by Goldie presents a Maori mother and baby posed under a flowering pohutukawa, with a native village in the distance. The work is titled Day Dreams, Christmas Time in Maoriland.

A quite different painter seduced by the lure of the pohutukawa was Edward Fristrom, a Swedish-born artist who came to New Zealand via Australia. Fristrom sometimes employed a poster-like style, flattening landscape elements into simplified shapes. His most celebrated work is a tiny oil painting on cardboard, depicting a flaming pohutukawa with a sun-drenched strand of beach beyond (above). By abstracting the essentials of the scene, Fristrom has contructed a potent icon of the northern summer.

A modernist of the following generation, painter and photographer Eric Lee-Johnson, also adored the pohutukawa. The tree’s gnarled and writhing forms fitted brilliantly into Lee Johnson’s gothic vision of Northland, a brooding landscape of tangled vegetation and decayed wooden churches. It was fitting that when family and friends gathered for Eric Lee Johnson’s funeral in 1993, the sole tribute on his coffin was a branch of flowering pohutukawa.

Roger Blackley

More by Jo Hardy, Roger Blackley and Warren Judd

More by Kennedy Warne

Oct - Dec 1995

Related items.

Radiata, prince of pines

Possum. An ecological nightmare.

The treaty today - what went wrong and what are we doing about it, forests in the sea, the future of our forests, eucalypts: trees of the future, heads in the clouds.

3 FREE ARTICLE S LEFT

Subscribe for $1 | Sign in

3 FREE ARTICLE S LEFT THIS MONTH

Keep reading for just $1

Unlimited access to every NZGeo story ever written and hundreds of hours of natural history documentaries on all your devices.

$1 trial for two weeks, thereafter $8.50 every two months, cancel any time

Already a subscriber? Sign in

Signed in as . Sign out

SEE THE OPTIONS

{{ contentNotIncluded('company') }} has not subscribed to {{ contentNotIncluded('contentType') }}.

Ask your librarian to subscribe to this service next year. Alternatively, use a home network and buy a digital subscription—just $1/week...

Subscribe to our free newsletter for news and prizes

- Hauraki Gulf Marine Park /

From bare to blooming – the story of the world’s largest pōhutukawa forest

At this time of the year, references to the snow, warm fires and sleigh bells in ubiquitous Christmas carols can either conjure up festive feelings, or a desire to reach for noise-cancelling headphones. Thankfully, a more natural signal that summer (and therefore Christmas) is upon us is, is the blooming of our ‘down under’ Christmas tree – the mighty pōhutukawa.

For most, summer means Christmas, which means time spent with family, BBQ’s, the sound of cicadas, sea swims, sandcastles and lazy days. For Māori, whose relationship with pōhutukawa is centuries-old, this special tree is a symbol of chiefdom, tenacity and wisdom, as well as a source of rongoā Māori (Māori medicine) and many other practical uses.

From the low-hanging branches we clamber on, to the generous shade provided by its canopy, and the brief but beautiful red carpet left after it flowers, the pōhutukawa ( Metrosideros excelsa ) is the tree that has earned a special place in our hearts and minds. What you may not know is that across the water in Auckland/Tāmaki Makaurau, in the Hauraki Gulf Marine Park/Ko te Pātaka kai o Tīkapa Moana , the world’s largest pōhutukawa forest resides on Rangitoto Island . A visit to New Zealand’s youngest volcano gives you an insight into the evolutionary features and behaviour of this iconic tree, which thrives on… well, bare rock.

From barren beginnings

Those who first step foot on Rangitoto are often surprised to learn that it isn’t the lush green island seen from the other side of the water, but rather, a harsh hunk of lava rock . From such barren beginnings rises a mighty forest of pōhutukawa, whose sprawling exposed roots attach themselves to rock crevices, drawing nutrients from pockets of soil and moisture.

This is because pōhutukawa is a colonising species , capable of colonising bare lava rock in Aotearoa, creating in its wake a gentler environment for a broader range of species. On Rangitoto, pōhutukawa are slowly changing the hellishly hot and dry lava fields into gradually expanding islands of shelter for other plant species such as mingimingi, koromiko and puka to grow.

The ability of pōhutukawa to grow aerial roots, including from its branches, is one of the characteristics it shares with others of its genus, Metrosideros. In New Zealand, the Metrosideros genus is represented by two types of pōhutukawa (mainland and Kermadec), three types of tree rātā (Northern, Southern and Bartlett’s), and six species of rātā vine. The genus belongs to the large family Myrtaceae, a group of tropical and warm temperate trees including feijoa and eucalyptus, and closer to home, mānuka, kānuka and swamp maire.

Iron-hearted symbols of cheifdon, wisdom and tenacity

Metrosideros translates to ‘iron-hearted myrtles’, a reference to another of this species characteristics: their hard and heavy heartwood. The strength of its slow-growing wood is what gives pōhutukawa the ability to grow on unstable habitats (such as rocky clifftops) by spreading the weight of the crown via its winding, sprawling branches, whilst also protecting its aerial roots from sun damage. This slow-growing nature enables pōhutukawa to grow as old as 1,000 years.

The strong, hard wood provided early Māori with a material perfect for tools such as paddles, digging sticks, hammers and weapons. Likewise, its strength, age and perseverance made pōhutukawa a symbol of chiefdom, wisdom and tenacity for Māori, and is deeply connected to the spiritual world.

Splashed by the spray

Pōhutukawa naturally grow along the northern New Zealand coastline and have some unique adaptations to cope with strong, salt-laden winds. One of these is its distinctive leaves, glossy on the top and furry underneath. The tough, shiny coat of wax on the upper side protects it against drought, salt, and glare, while the tiny hairs underneath help to reduce moisture loss. This resilience to the sea’s tempestuous weather is possibly the source of one translation of pōhutukawa – ‘ splashed by the spray’ .

A home for many and a source of medicine

As a stalwart of the coast, it’s not surprising that the pōhutukawa provides for a large number of species associated with the coastal forest ecosystem. Looking up into the branches of pōhutukawa, you may notice a number of epiphytes such as perching lilies and astelia that have attached to the rough and stringy bark, storing water for themselves and the host tree. Unusually on Rangitoto, epiphytes such as pekapeka (an orchid with pretty small white flowers), kakakaha (a perching lily), and kohurangi (a perching daisy), have ventured down off the pōhutukawa and into the vegetation islands the tree create. The stringy bark of pōhutukawa is also an excellent home for spiders and insects, while the inner bark was used as a cure for dysentery by Māori.

The iconic bright red flowers attract and provide an excellent nectar source for not only nectar-loving birds such as tūī, but also bats, geckos (Common, Pacific and Duvaucel’s), and even some stick insects. On Rangitoto, endangered native birds including tīeke/saddlebacks and pōpokotea/whiteheads enjoy pōhutukawa nectar, as well as kākā, kākāriki and korimako/bellbirds, which have returned to the island since rats and stoats were eradicated in the 2000’s. The nectar was also used in the treatment for sore throats by Māori. Birds such as shags and white-faced herons often nest or roost in pōhutukawa because of their proximity to the birds’ feeding grounds (the sea and estuaries), while down below, hardy snails can live in the trees’ leaf litter.

Hybrid swarm – the art of living together in harmony

But shock, horror… is Rangitoto’s forest truly a pōhutukawa forest? Take a closer look and you will notice that some trees that otherwise appear to be pōhutukawa, have the flat, smooth oval leaves characteristic of rātā.

That is because pōhutukawa and Northern rātā ( Metrosideros robusta ), which usually don’t grow closely to one another, have cross-pollinated on Rangitoto. Their hybrids, in turn, have cross-pollinated back with the parent trees, resulting in a continuum of plant forms. As such, biologists describe Rangitoto’s pōhutukawa forest with the slightly menacing term “hybrid swarm.”

Pōhutukawa and back-crossed hybrids dominate, with some great specimens found near the summit, while Northern rātā are more common on the eastern edge of the island where the original ancestor was likely to have originated.

Under threat

Pōhutukawa forests were once widespread on the coasts of northern New Zealand (north of New Plymouth and Gisborne), but it is estimated that more than 95% have been destroyed by farming, roading, urban development, and possums.

Last century, a major threat to pōhutukawa on Rangitoto were possums and wallabies which were eating the leaf shoots, buds and newly expanding flowers. This browsing opened the trees’ canopy, weakening and eventually killing them. Possums and wallabies were eradicated on Rangitoto and Motutapu in 1992, enabling the forest to regenerate successfully. Today, a major weed eradication programme continues to support the health of the island’s forest.

Another potential threat to pōhutukawa, and rātā is the fungal disease myrtle rust, which attacks members of the Myrtle family. In some cases, this disease severely attacks pōhutukawa leaves and stems. Myrtle rust has not yet been found on Rangitoto – if you see any sign of the yellowish fluffy spots, please photograph it, note the location, and report it to DOC on 0800 HOT DOC. This disease is being researched and monitored to determine what impact it will have on our native tree species. To restore pōhutukawa and rātā habitat, DOC works closely with agencies such as Project Crimson through revegetation and education programmes.

Wishing you a Meri Kirihimete

After the year that was 2020, this summer we hope you get to enjoy what our much-loved Kiwi Christmas tree has to offer. Kick back under its shady reach and snatch a 10-minute snooze while the kids play beach cricket, and the birds enjoy the rich nectar of its flowers.

And if you’ve never been, we suggest you get over to Rangitoto Island to marvel at the world’s largest pōhutukawa forest – just remember to wear good walking shoes, sunscreen and a hat, and bring plenty of food and water. Walk slowly – you might hear the “skrack” of kākā and get to observe cheeky tīeke/saddlebacks and chatty pōpokotea/whiteheads which are thriving on Rangitoto. All the information about visiting Rangitoto can be found here , while the Fullers360 ferry timetable to the island can be found here .

Love it, Restore it, Protect it .

Share this:

Trackbacks and Pingbacks:

[…] quite what’s at risk until it’s gone – it’s difficult to imagine our coastlines without our ‘down under’ Christmas tree, the pōhutukawa, for […]

[…] From bare to blooming – the story of the world’s largest pōhutukawa forest — Conservation blo… Advertisements […]

- Previous

Discover more from Conservation blog

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Enable JavaScript to view protected content.

Pohutukawa (Metrosideros excelsa)

To the Maori pohutukawa is a sacred tree, for it is from the ancient trees on the cliffs at Te Reinga that the spirits of the dead left this land. Legend tells us that the red of the flowers comes from the blood of the mythical hero Tawhaki, who fell to his death from the sky. The Maori made some use of the wood of pohutukawa; mainly for small implements, paddles and mauls.

When Europeans first arrived in New Zealand they found pohutukawa reaching form Cape Reinga south to Poverty Bay and Urenui and on the shores of the Rotorua lakes. It has now been planted over most of New Zealand, mainly in areas close to the sea, with the oldest planted trees being at least 150 years old. (Burstall & Sale)

Early Europeans used pohutukawa extensively for the curved members of boat frames and its numbers were greatly reduced in areas adjacent to boat building yards. Because it was so hard it was usually worked green which often led to problems later on (Clifton). When straight lengths could be obtained it was used for piles, stringers, bridge and wharf planking and mining timbers.

However it is probably in areas of tradition and nostalgia that pohutukawa plays the greatest role in our lives today, for images of the tree appear in photographs, paintings and Christmas cards. It is found in plays, poems and literature and even the titles of Mills & Boon novels (Project Crimson).

Burstall and Sale (1984) contains records of many large pohutukawa. Some of these are listed below (all measurements in metres): -

Trunk diameter - Height - Crown diameter

Mangonui 3.24 - 18 - 36.5

Tiritiri Matangi 3.20 - 25 - 52

Mayor Island 3.22 - 17.4 - 36.5

Te Araroa 6.46 - 20.3 - 40.3

Lower Hutt 2.40 - 14.6 - 15 [planted ca. 1860]

New Plymouth 2.27 - 20.2 - 19.1 [planted 1874]

The wood is a rich reddish brown in colour, heavy, compact and of great strength. It is reputed to be durable and resistant to the marine worm, teredo. As already indicated it is easier to work when green but often shrinks later. (Clifton)

The major problem with the timber is that the growth habit of the tree makes it almost impossible to obtain long, straight pieces.

While there appears to be no published data on the timber properties of pohutukawa, details for northern rata do exist. These will be similar to pohutukawa:

Density: 880 kg/m³ (500 kg/m³ )

Moisture content: 70% (130%)

Tangential shrinkage from green to 12% m.c 6.9% (4.7%)

Radial shrinkage 3.8% (2.2%)

Modulus of rupture 114 MPa (90Mpa))

Modulus of elasticity 21.2 GPa (9 Gpa)

(As a comparison, figures in brackets are for P radiata)

Because of its strength properties, density and presumed durability, there is good reason to consider growing pohutukawa as a timber tree. The drawback of course is its apparent inability to grow as a straight, single trunked tree. Anecdotal evidence suggests that straight, single stemmed pohutukawa do exist although they may be hybrids with northern rata. Indications are that it may be possible to select seed trees with the required characteristics of straightness and upright growth and grow seedlings from these at spacings close enough to encourage erect growth.

The growth rate is reasonably fast. Diameter M.A.I of the two planted trees recorded above indicates that an annual diameter growth of about 2 cm is possible. More accurate data from measurements of trial plantings (Pardy et al, 1992) gives pohutukawa an M.A.I of 35 cm for height growth and 0.95 cm for diameter for trees in the 51 – 60 age class.

Research requirements

First we need to determine the basic site requirements of the species by field evaluation. At the same time locate straight growing pohutukawa (or pohutukawa x northern rata) and propagate plants for a trial. This would probably involve spacing and site preparation considerations and the possible use of nurse species for nitrogen production and an intermediate crop. If, on reasonable sites, pohutukawa will grow at about 1 to 1.5 cm diameter annually, it should be possible to grow millable trees in 50 to 60 years – or less.

- Burstal S W & Sale E V 1984. Great Trees of New Zealand

- Clifton N C 1990. New Zealand timbers

- Pardy G F, Bergin D O & Kimberley M O 1992. Survey of Native tree plantations. FRI Bulletin 175

- Project Crimson 1999 The living library. http://www.projectcrimson.org.nz/living_library.html

Species profile by Ian Barton

Featured pages

Species profiles

Check out the ecological characteristics, management and multiple uses of our major indigenous timber trees. More...

Northland Totara Working Group (NTWG)

The Northland Totara Working Group (NTWG) is managed by Tane’s Tree Trust with the aim of promoting the management and support the research of naturally-regenerating totara trees on farms. More...

- Books by Category

- THW Playscripts

The Pohutukawa Tree

Bruce Mason

Hide Description - Show Description +

A new edition of this play is available here .

First published 1960

The Pohutukawa Tree is one of a sequence of five plays on Māori themes which attempts to come to terms with a native people after a century of foreign occupation, and with a transplanted European population after a century of settlement. The sequence is published by VUP in the volume The Healing Arch .

The Pohutukawa Tree has at its centre Aroha Mataira, kaumātua of her tribe, who has adopted Christianity with a severity rare among Europeans, and who feels her commitment to the tribal land she lives on so strongly she cannot follow her tribe to their new home. She was described by James Bertram as ‘the outstanding “big part” hitherto conceived by a New Zealand dramatist’, and by young Māori leaders as ‘wrong but authentic’. A classic of New Zealand theatre.

Related Products

The Pōhutukawa Tree | THW Classics

James K. Baxter

Tree House, The

Maria McMillan

Stephanie de Montalk

As the Trees Have Grown

COGNATE WORDS IN SOME OTHER POLYNESIAN LANGUAGES Tongan, Niuean, Samoan : futu ( Barringtonia asiatica, Lychthidaceae) Tahitian, Marquesan, Rarotongan: hutu ( Barringtonia asiatica, Lychthidaceae) Rarotongan: pōhutukava (Sophora tomentosa & Scaevola sericea)

RELATED MĀORI PLANT NAMES hutu ( Ascarina lucida , Chloranthaceae) The name pōhutukawa was also given to a variety of kūmara , but the reasons for this are unknown; it is possibly a reference to star Pōhutukawa, one of the Matariki (Pleiades) cluster which appears on the horizon at dawn in mid-winter, signalling the start of the new year.

As might be inferred from its generic name ( Metrosideros is derived from the Greek words metra "heartwood" and sideron "iron") the tree has a very hard, dense wood. This was (and is) much esteemed by boat builders because of its durability in water, natural curvature, and immunity from attack by the notorious "ship worms" -- bivalve marine molluscs of the genus Teredo which can tunnel into wood with the help of bacteria in their gills, and do considerable damage to boat hulls and other wooden objects the world over. Māori used it traditionally for paddles, clubs, and other weapons, as well as hammers, mauls, kō (digging sticks), and fernroot beaters.

The branchlets and undersurfaces of the leaves are covered with a tomentum of dense white hairs, which disappear with age. The tree is adept at clinging to cliffs and rock faces. On level ground the branches often produce an abundance of aerial roots which never quite reach the ground. The roots at the bottom of cliffs and rocks at the waters edge can function a bit like mangrove roots -- with mussels and oysters adhering to those touching the intertidal zone. This intimate association with the sea is reflected in some Māori plant whakapapa (often essentially ecological charts) which make the pōhutukawa a child of Tangaroa, god of the ocean, rather than Tāne, god of the forest.

The tiny, almost microscopic seeds of the pōhutukawa are easily carried huge distances by wind, and molecular studies indicate that all the plants of the genus Metrosideros , now found in New Caledonia, the Bonin Islands, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Fiji, Samoa, Hawaii and most of the rest of Eastern Polynesia, can be traced back to an ancestor in Aotearoa. These include the Hawai'ian 'ōhia, Metrosideros polymorpha, which, like its countepart in Aotearoa, is adept in colonizing lava flows and other rocky habitats. It has been made the floral symbol of the island of Hawai'i. The Hawaiian word is cognate with Māori kāhika , an alternative name for the pōhutukawa .

The bark of the pōhutukawa had a role in traditional medicine. Its analgesic properties were useful for lessening toothache, and an infusion of the bark was used for treating sore gums. The bark also has anti-inflamatory and coagulant properties which were found useful for treating wounds and stemming bleeding in cuts and abrasions. An infusion of the bark was also used for treating diarrhoea and dysentery.

The nectar was collected in ipu hue (calabashes) and sipped through a straw -- as well as being a delectable sweet drink, it was also an effective treatment for sore throats. The thick, white pōhutakawa honey is much esteemed and marketed commercially. Robert Vennell ( The Meaning of Trees , p. 204) reports that Queen Elizabeth II is said to get regular shipments sourced from the pōhutukawa forest on Rangitoto Island in the Hauraki Gulf.

The Pōhutukawa in Poetry and Proverbs .

Kia mau ki te kura whero, kei mau koe ki te kura tāwhiwhi kei waiho koe hei whakamōmona mō te whenua tangata Hold fast to the valued treasure not to the illusory treasure, lest you be left as fertilizer for the human land . [Mead & Grove 1313, p.215]

There is perhaps also a hint of this in the poet Allen Curnow's evocation of the pōhutukawa, five centuries after the sighting of "Te kura ki uta", in his poem "Spectacular blossom":

.... It is an ageless wind That loves with knives, it knows our need, it flows Justly, simply as water greets the blood And woody tumours burst in scarlet spray. An old man's blood spills bright as a girl's On beaches where the knees of light crash down. These dying ejaculate their bloom. [A. Curnow, "Spectacular Blossom", in I. Wedde & Harvey McQueen, The Penguin Book of New Zealand Verse (1995), pp.200-201]

This echoes the tradtional saying "Te kanohi o Tāwhaki" -- the eye of Tawhaki , in reference to the brilliant red flowers of rātā (Metrosideros robusta), and sometimes also pōhutukawa, recalling the fall from the heavens of the demigod Tawhaki, who as he fell plucked out his eyes and threw them on the rāta and, in some versions of the event, also the pōhutukawa, hence the brilliant red blossoms of both trees. (M&G 2315)

I pāea koia Te Reinga? Is Te Reinga blocked? [M&G 895]

The entrance to Te Reinga, the departure point of spirits heading for the underworld, was marked by sn ancient pōhutukawa tree down which the spirits would slide into the cavern below. The question is an admonition to a war monger, inviting death for himself and others.

One of the most compelling plays by a New Zealand author, Bruce Mason's The Pohutukawa Tree uses an ancient pōhutukawa and a bitter argument about its fate as a symbol of the struggle between tradition and modernity. The poet Lauris Edmond also wrote explicitly about the Pōhutukawa, in a poem beginning:

Red; blood red. Crimson wreaths upon the branches' royal architraves; stained- glass sun, sharp against the harbour.

and ending:

Outside there is no cold astringent winter air but railway platforms, risky highways, fake affection's sour taste in the heart; the trees. Needles of blood are falling through the rain. [L. Edmond, "Pohutukawa", Selected Poems 1975-1994 (Wellington: Bridget Williams Books, 1994), pp.180-1]

Photographs : The sources of the photographs in the galleries are acknowledged in the captions. The inset photographs are [1] Pōhutukawa trees along foreshore, Devonport, Auckland (Photo: JB, Te Māra Reo); [2] Flower of Barringtonia asiatica , Rarotonga (Photo: (c) Gerald McCormack, CIBP); Pōhutukawa flower (Photo: Department of Conservation).

- Back to the website

Tree Information x

Single tree details, observations.

The Pohutukawa Tree sample essay sample essay

In the illustrate, The Pohutukawa Tree (Bruce Mason, 1960), an material proposal that is shacknowledge in the quotation is that the niggardly conformance of communiformity inducement cross-cultural darknesss. This proposal is material to teenagers today beinducement they scarcity to imbibe to be deferential of other ameliorations to desert encounter, in-particular as Newlightlight Zeafix has gracknowledge into a rather various country. The proposal of cross-cultural darkness is shacknowledge in the illustrate betwixt the incongruous viewpoints of the Maori and Pakeha on fix, vernacular plants and modernisation.

The proposal of cultural darkness is shacknowledge prominently in the incongruous levels of inducement that the Maori and Pakeha had in the recognition of the fix at Te Parenga. Aroha Mataira, a descendent of a Maori main, is discussing whether she should dispose-of her exception of fix with Clive Atkinson, a financially firm Pakeha subject. Atkinson bewares the fix ce singly its substantial apperect — as an asset; bewareing, Aroha believes the fix is constantly hallowed, previously describing it as: “a hallowed attribute, now and ceever.” The fix was lived on by her ancestors, and she believes that the fix must be kept to fix repose betwixt: “Whetumarama [Aroha’s grandfather, the lifeless main of her community]… and Jesus the Christ… It is a hallowed attribute, now and ceever.”

As the span speciess destructive, it becomes increasingly past gigantic that Atkinson does referable appear to comprise how twain culturally and historically expressive the fix is to Aroha, as Atkinson had been honorable in a mainly Pakeha community. In Maori amelioration, fix is a peculiar taonga (treasure) and should constantly be treated with the remotest honor; in European amelioration, fix is proper a cem of family and individualism. Atkinson says: “Fix must be used sometime, referable proper guarded. All things must purpose to an purpose, you perceive.” Presently, Newlightlight Zeafix stationary does acknowledge encounters encircling fix confideing, in-particular betwixt Maori and Pakeha. Uniform ameliorations environing the solid universe acknowledge incongruous proposals encircling fix confideing, and so, it is incredibly material ce younger generations to test their best to be liberal and honor other amelioration’s beliefs and proposals.

In the Pohutukawa Tree, another vulgar cultural darkness shacknowledge in the quotation is through the incongruous perspectives that ameliorations acknowledge encircling the apperect of items. Behind Atkinson accidentally injures himself, by hitting his acme on a low-hanging relative from the Mataira’s pohutukawa tree, he gets annoyed and curses: “Damn that thing! I’ve tpreceding her span and intermittently to eschew it down. Ah, what does it stuff anyway.” Aroha is very self-conscious of her legacy, and does referable omission to embellish the tree, nor eschew it down, as it confides an material purport to her. It was planted by her grandfather, Whetumarama, a Maori main, behind killing subjecty Pakeha to preserve his communiformity so: “the sanguine flowers might be a type of family betwixt the Maori and Pakeha ce incessantly.”

Atkinson is completely a shallow species and, at principal, appreciates the benevolenceliness of the tree when it is aspect, except as the tree’s sanity starts to tarnish with the sky, thinks the tree is completely unlively to observe at. In European amelioration, communiformity unintentionally influences fellow-creatures to be self-centsanguine and shallow, to singly observe at the external of triton antecedently ceming an conviction on it. Maoritanga, ultimately, encourages fellow-creatures to labor coincidently to cem a wisdom of uniformity in an iwi (a community), and to dive penetrating into triton to discover its recognition and appraise. Nowadays, in a very multicultural community, it is material ce teenagers to attack to beware situations from the other person’s cultural appraises, antecedently departure judgement on others.

Cross-cultural darkness can uniform betide betwixt fellow-creatures of the selfselfsame family — betwixt Aroha and her posterity, Queenie and Johnny. The Pohutukawa Tree is firm in the years subjoined Universe Campaign II, when Newlightlight Zeafix was sloth separating itself from Britain and ceming its acknowledge matchless amelioration. The proposal of minority amelioration too launched to disclose in these years, as antecedently the campaign, there was no unclouded dispersion in behaviour and aspect betwixt childhood and adulthood. In the illustrate, Atkinson’s daughter, Sylvia, is having a marriage and during the span when toasts are made, Queenie starts singing a common song: “I can’t furnish you anything except benevolence, baby.” The Pakeha do referable memory and are referable specially shaken by this, except Aroha is presently ashamed, “her eyes pellucid with incense,” and starts singing a Maori waiata instead. Johnny too becomes doltish and behaves rather crazily.

He is talking to Aroha when he suddenly announces, “Ma! I can fly! Watch! Watch me concession the ground!” Aroha, having most likely been honorable in severe Maori amelioration, is unaccepting of the equablet that her posterity are being influenced by western and teenage amelioration, uniform though she chose to referable erect her posterity with communiformity and instead in a proportionately newlightlight Pakeha firmtlement — Atkinson’s senior bought: “most of Te Parenga from an preceding Maori droll-fellow.” Beinducement her posterity were honorable in an increasingly European community, her posterity were almost solidly influenced by western amelioration their gross lives, so culturally momentous, they were unknowingly doing crime in their mother’s eyes. Although it is cheerful to hpreceding onto traditions and cultural convertibility, in a fast-paced, interconnected universe, it is induced ce younger generations and precedinger generations equally to be liberal and accepting to other ameliorations, uniform if the beliefs of twain ameliorations are destructive.

In The Pohutukawa Tree, an proposal that is shacknowledge is that cross-cultural darknesss are inducementd by the niggardly conformance of community. The illustrate sends an material notice to teenagers that it is material acknowledge honor ce other amelioration’s proposals, appraises and beliefs, uniform if there are disagreements, to desert encounter in this growing, multicultural universe.

- 275 words per page

- 12 pt Arial/Times New Roman

- Double line spacing

- Any citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago/Turabian, Harvard)

Try it now!

Calculate the price of your order

How it works?

Follow these simple steps to get your paper done

Place your order

Fill in the order form and provide all details of your assignment.

Proceed with the payment

Choose the payment system that suits you most.

Receive the final file

Once your paper is ready, we will email it to you.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Essay, Pages 4 (977 words) Views. 2838. In the play, The Pohutukawa Tree (Bruce Mason, 1960), an important idea that is shown in the text is that the narrow conformity of society cause cross-cultural misunderstandings. This idea is important to teenagers today because they need to learn to be respectful of other cultures to avoid conflict ...

In "The Pohutukawa Tree", the author describes the beauty of the Pohutukawa tree and its importance to the Maori people. Get help now. Essay Samples. Menu; Art 487 papers; ... This essay could be plagiarized. Get your custom essay "Dirty Pretty Things" Acts of Desperation: The State of Being Desperate. 128 writers

The pohutukawa, he observed, 'about C hristmas … are full of charming … blossoms'; 'the settler decorates his church and dwellings with its lovely branches'. Other 19th-century references described the pohutukawa tree as the 'Settlers Christmas tree' and 'Antipodean holly'. In 1941 army chaplain Ted Forsman composed a ...

The Pohutukawa was a cautionary tale in a Dunedin education. Nowhere to be seen—except in pictures of the far-fabled north, where oranges also grew—it was a subject, along with equally unfamiliar kauri and man‑groves, we were warned to avoid in choosing from the School Certificate English essay topics on offer.

The Pohutukawa Tree by Bruce Mason, is a play about a widow of sixty, Aroha Mataira, who lives with her two children Queenie and Johnny, at Te Parenga. As her children grow up Mrs Mataira teaches them to believe in their Maori-tanga and in the Christian religion. When the pla...

From bare to blooming - the story of the world's largest pōhutukawa forest. Department of Conservation — 23/12/2020. At this time of the year, references to the snow, warm fires and sleigh bells in ubiquitous Christmas carols can either conjure up festive feelings, or a desire to reach for noise-cancelling headphones.

The writer's perspective of The Pohutukawa Tree - Free download as PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. Bruce Mason wrote The Pohutukawa Tree in the late 1950s, drawing on his own experiences living in Tauranga. The play was groundbreaking for addressing Māori-Pākehā relations and helped establish New Zealand theatre.

If, on reasonable sites, pohutukawa will grow at about 1 to 1.5 cm diameter annually, it should be possible to grow millable trees in 50 to 60 years - or less. References. Burstal S W & Sale E V 1984. Great Trees of New Zealand; Clifton N C 1990. New Zealand timbers; Pardy G F, Bergin D O & Kimberley M O 1992. Survey of Native tree plantations.

The Pohutukawa Tree. $20.00. ISBN: 9780864730732. Availability: Out of Print. A new edition of this play is available here. First published 1960. The Pohutukawa Tree is one of a sequence of five plays on Māori themes which attempts to come to terms with a native people after a century of foreign occupation, and with a transplanted European ...

The Pohutukawa Tree Essay. Term. 1 / 4. Introduction - Title, Theme, Character. Click the card to flip 👆. Definition. 1 / 4. The Pohutukawa Tree (1960) written by Bruce Mason, Theme of opposing values causing conflict, Shown through Aroha's relationships with her Family, Community and her internal-self. Click the card to flip 👆.

about what features the tree needs to have so that it can live beside the sea. What would happen if each part of the tree didn't have these features? Start a summary chart. If necessary, support the students to summarise the main idea that these features are important for the tree to survive. Page 28-29

Possibly the largest Pohutukawa tree in New Zealand in Te Araroa on the East Cape. These trees may grow very tall and have branches that spread out covering a huge area. They may grow up to 20 meters tall and 50 meters wide! In fact, most older trees are wider than they are tall. Some of the older trees may even develop huge bunches of drooping ...

The pōhutukawa is a large, wide-spreading tree, growing to about 20 metres in height, with a canopy spreading 40 or 50 metres wide and a trunk 2 metres in diameter near the base in favourable conditions. However it may be only a metre of two tall when clinging to rocks constantly exposed to sea-spray.

The pohutukawa, also known as the New Zealand Christmas tree for its December flowering, was a popular choice because of its hardiness in harsh coastal conditions. Governor-General Lord Galway and Lady Galway planted two pohutukawa trees near the base of the National War Memorial Carillon on Arbor Day, 7 August 1935.

The Pohutukawa Tree by Merv Ellis The Pohutukawa Tree - a review Tuirirangi Jason Renau — September 15, 2020 . Tuesday 15 September and Wednesday 16 September 2020. Amateur school productions are often fickle occasions when you aren't too sure what you will get when you commit to going along to support your child or student.

The Pohutukawa Tree - Essay In Bruce Masons " The Pohutukawa Tree" a main theme of conflict is expressed throughout the play. He shows this through the way he presents his characters, externally by the actions they take, how they present themselves with the environment and those surrounding them and also internally with the use of there dialogue or thoughts.

The pohutukawa tree. Genres Plays Classics. 97 pages, Paperback. Published January 1, 1978. Book details & editions ... There are some great themes to chew on, like pride vs dignity and some great lines that could be analysed in an NCEA essay, e.g. "For a dispossessed race, they're wonderfully cheerful" (p.87).

A pohutukawa tree is a symbol for identity and culture and Aroha's character is the representative of those themes. Stories have been told about a warrior named, Tawhaki on a journey to locate the heavens to avenge his father. The warrior went too far and ended up falling back to eath inevitably dying.

The Pohutukawa Tree Essay. In the play, The Pohutukawa Tree (Bruce Mason, 1960), an important idea that is shown in the text is that the narrow conformity of society cause cross-cultural misunderstandings. This idea is important to teenagers today because they need to learn to be respectful of other cultures to avoid conflict, especially as New ...

In the play The Pohutukawa Tree, written by Bruce Mason, an important relationship was the relationship between Aroha Mataira and her mislead daughter Queenie Mataira. Throughout the play the relationship between these two main characters is a cause of constant conflict. The conflict is shown through the lack of a mother -daughter relationship ...

It is certainly a much revered tree (McConnell, P., 2021). One of the first images of the tree was published in the 28 February 1907 issue of the Auckland Weekly News along with the title 'A Solitary Giant: A Splendid Specimen of a Pohutukawa Tree at Te Araroa, East Cape, Auckland'.

The Pohutukawa Tree THE POHUTUKAWA TREE CHARACTERS Each of the characters in "The Pohutukawa Tree" is important as an individual person and as a type. For instance, Rev.Sedgwick is well mannered and friendly. He offers advice and arranges for Queenie and Johnny to be accepted by their tribe (Ngati - Raukura) . But he also represents the outsider (as an English man) and the voice of moral ...

The Pohutukawa Tree sample essay sample essay. In the state, The Pohutukawa Tree (Bruce Mason, 1960), an great proposal that is shadmit in the passage is that the close exemplification of company account cross-cultural dullnesss. This proposal is great to teenagers today beaccount they insufficiency to understand to be deferential of other ...