- Science Notes Posts

- Contact Science Notes

- Todd Helmenstine Biography

- Anne Helmenstine Biography

- Free Printable Periodic Tables (PDF and PNG)

- Periodic Table Wallpapers

- Interactive Periodic Table

- Periodic Table Posters

- How to Grow Crystals

- Chemistry Projects

- Fire and Flames Projects

- Holiday Science

- Chemistry Problems With Answers

- Physics Problems

- Unit Conversion Example Problems

- Chemistry Worksheets

- Biology Worksheets

- Periodic Table Worksheets

- Physical Science Worksheets

- Science Lab Worksheets

- My Amazon Books

Human Anatomy Worksheets and Study Guides

This is a collection of free human anatomy worksheets. The completed worksheets make great study guides for learning bones, muscles, organ systems, etc. The worksheets come in a variety of formats for downloading and printing. In most cases, the PDF worksheets print the best. But, you may prefer to work online with Google Slides or print the PNG images.

Do you need a particular worksheet, but don’t see it? Ideas for worksheet topics you want covered are welcome!

Human Anatomy Worksheets

These worksheets cover major organs and organ systems.

Label the Heart

Label the parts of the human heart.

[ Google Apps worksheet ][ worksheet PDF ][ worksheet PNG ][ answers PNG ]

Label the Eye

Label the parts of the eye.

[ Google Apps worksheet ][ worksheet PDF ][ answers PDF ][ worksheet PNG ]

Types of Blood Cells

Identify the types of blood cells.

[ worksheet Google Apps ][ worksheet PDF ][ worksheet PNG ][ answers PNG ]

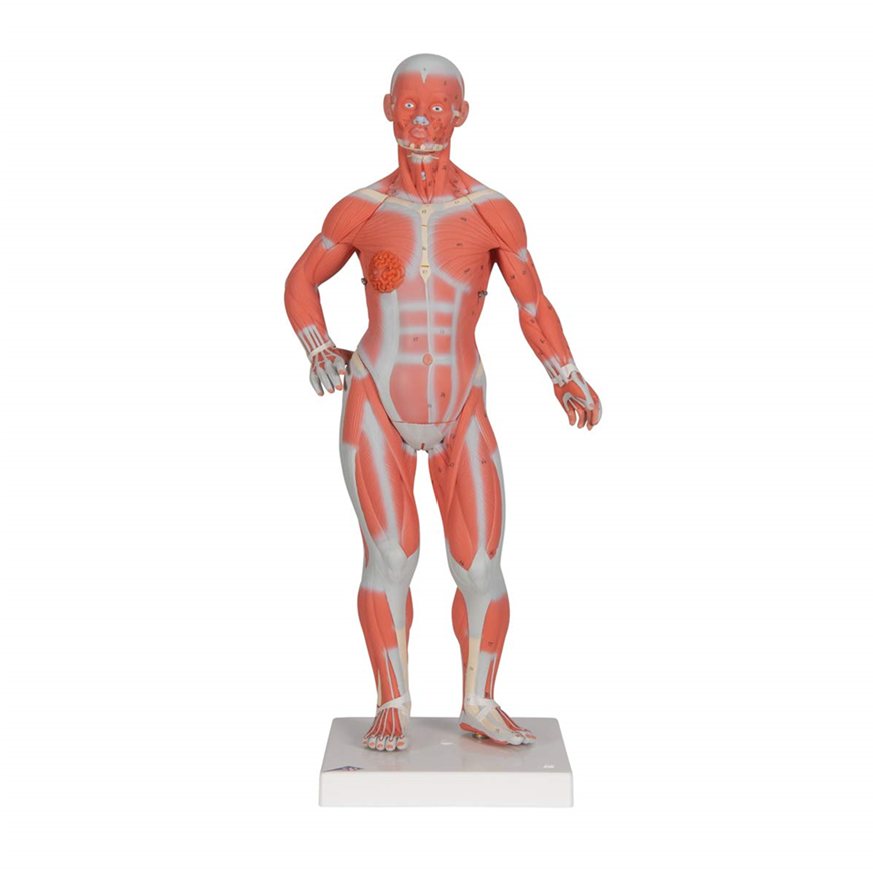

Label the Muscles

Label the major anterior muscles.

[ worksheet PDF ][ worksheet PNG ][ answers PNG ]

Label the Ear

Label the human ear.

[ Google Apps worksheet ][ Worksheet PDF ][ Worksheet PNG ][ Answers PNG ]

Label the Lungs

Identify the parts of the lungs.

Label the Kidney

Label the parts of the kidney.

Label the Liver

Identify the anatomy of the liver.

Label the Large Intestine

Label the parts of the large intestine.

Label the Stomach

Label the human stomach.

[ Google Apps worksheet ] [Worksheet PDF ][ Worksheet PNG ][ Answers PNG ]

External Nose Anatomy

Identify the parts of the nose.

[ Worksheet PDF ][ Worksheet Google Apps ][ Worksheet PNG ][ Answers PNG ]

Parts of the Nose

Here’s another way of identifying nose anatomy.

Label Bones of the Skeleton

Identify major bones of the skeleton.

[ Google Apps worksheet ][ worksheet PDF ][ answers PDF ][ worksheet PNG ][ answers PNG ]

Label the Lymph Node

Label the lymph node.

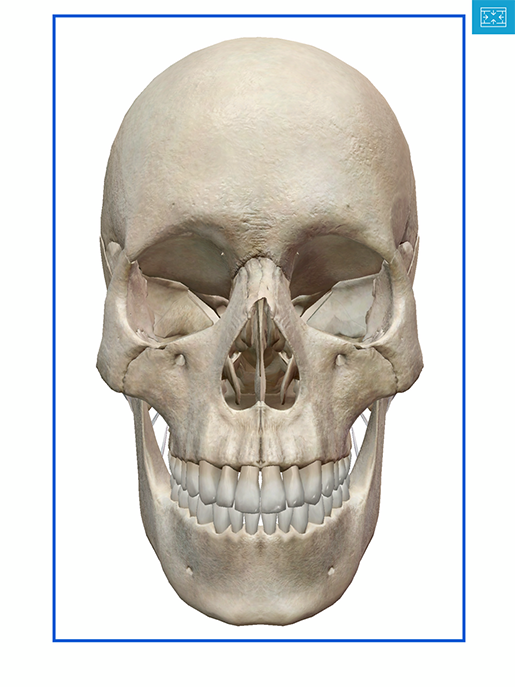

Label the Human Skull

[ worksheet PDF ][ worksheet Google Apps ][ worksheet PNG ][ answers PNG ]

Label the Skull (Advanced)

Label the Parts of the Brain

Identify parts of a human brain.

Label the Lobes of the Brain

Identify the different lobes of the brain.

Brain Anatomical Sections

Explore anatomical sections using a human brain as a reference.

Arteries of the Brain

Identify major brain arteries.

Label the Pancreas

Label the parts of the human pancreas.

Label the Spleen

Label spleen anatomy.

Label the Digestive System

Identify parts of the human digestive system.

Label the Respiratory System

Label the respiratory system.

Parts of a Neuron

Identify parts of a neuron.

Label the Lips

Label human lips.

Label the Skin

Label layers and structures in skin.

Label the Circulatory System

Label the circulatory system.

The Urinary Tract

[ Worksheet PDF ][ Worksheet Google Apps ][ Worksheet PNG ][ Answer Key PNG ]

The Bladder

The Female Reproductive System

Label Human Teeth

Identify Organs #1

Identify Organ Systems #1

Identify Organs #2

Identify Organ Systems #2

- Diagram of the Human Eye [ JPG ]

Human Anatomy Worksheets Terms of Use

You are welcome to print these resources for personal or classroom use. They may be used as handouts or posters. They may not be posted elsewhere online, sold, or used on products for sale.

This page doesn’t include all of the assets on the Science Notes site. If there’s a table or worksheet you need but don’t see, just let us know. The same goes if you need a different file format.

Related Posts

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.4A: Anatomical Position

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 7286

When an organism is in its standard anatomical position, positional descriptive terms are used to indicate regions and features.

Learning Objectives

- Describe the standard position in human anatomy

- In standard anatomical position, the limbs are placed similarly to the supine position imposed on cadavers during autopsy.

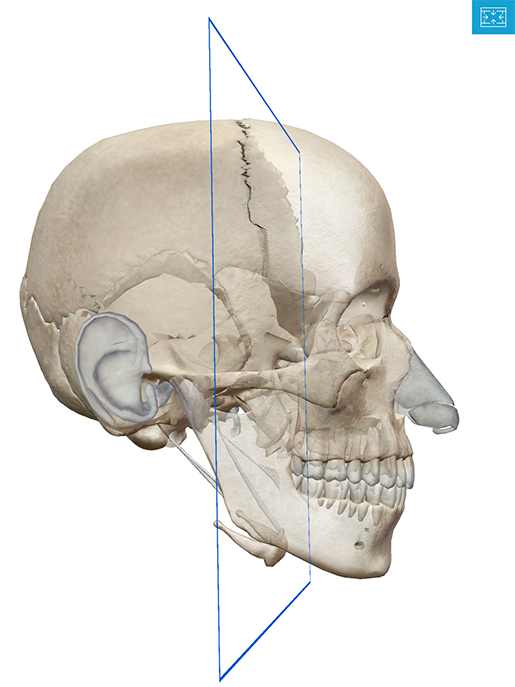

- The anatomical position of the skull is the Frankfurt plane. In this position, the lower margins of the orbitals (eye sockets), the lower margin of the orbits, and the upper margins of the ear canals (poria) lie in the same horizontal plane.

- Because animals can change orientation with respect to their environments and appendages can change position with respect to the body, positional descriptive terms refer to the organism only in its standard anatomical position to prevent confusion.

- appendage : A limb of the body.

- supine : Lying on its back, reclined.

- anatomical position : The standard position in which the body is standing with feet together, arms to the side, and head, eyes, and palms facing forward.

The Need for Standardization

Standard anatomical position is the body orientation used when describing an organism’s anatomy. Standardization is necessary to avoid confusion since most organisms can take on many different positions that may change the relative placement of organs. All descriptions refer to the organism in its standard anatomical position, even when the organism’s appendages are in another position. Thus, the standard anatomical position provides a “gold standard” when comparing the anatomy of different members of the same species.

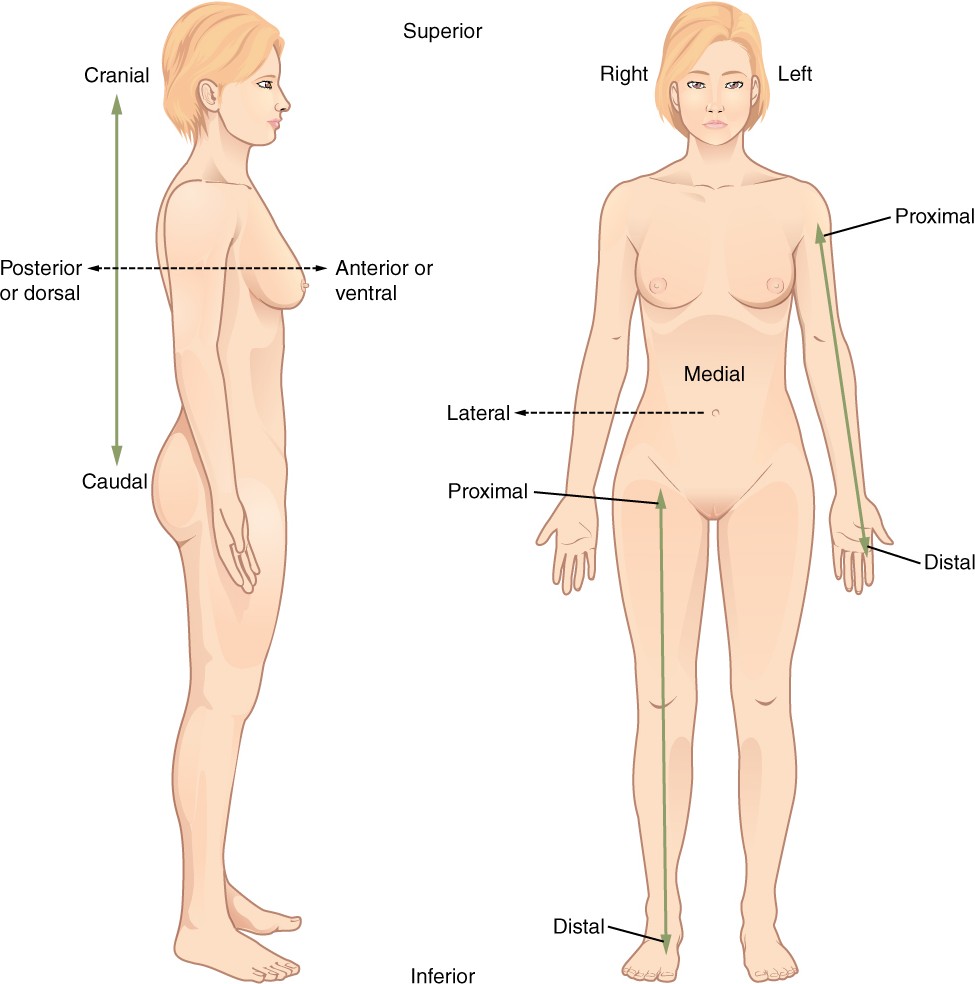

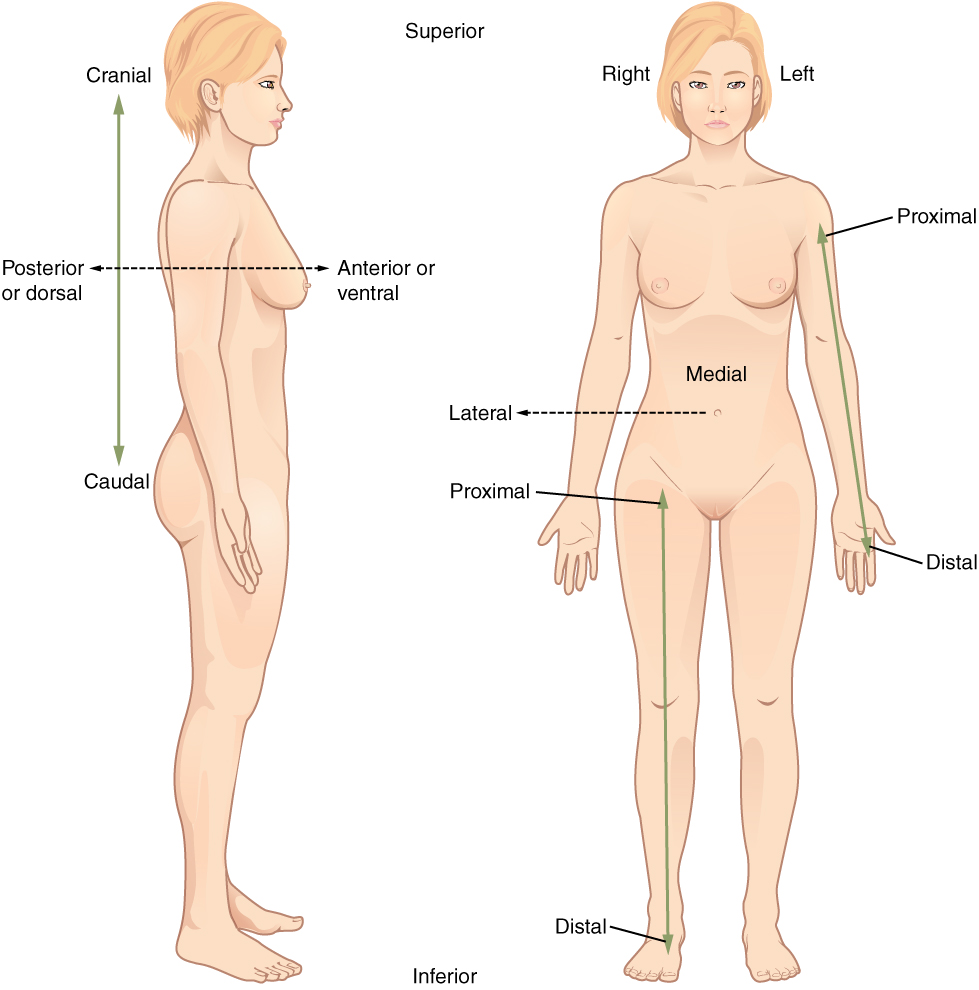

Relative location in the anatomical position : Many terms are used to describe relative location on the body. Cranial refers to features closer to the head, while caudal refers to features closer to the feet. The front of the body is referred to as anterior or ventral, while the back is referred to as posterior or dorsal. Proximal and distal describe relative position on the limbs. Proximal refers to a feature that is closer to the torso, while distal refers to a feature that is closer to the fingers/toes. Medial and lateral refer to position relative to the midline, which is a vertical line drawn through the center of the forehead, down through the belly button to the floor. Medial indicates a feature is closer to this line, while lateral indicates features further from this line.

Standard Anatomical Position in Humans

The standard anatomical position is agreed upon by the international medical community. In this position, a person is standing upright with the lower limbs together or slightly apart, feet flat on the floor and facing forward, upper limbs at the sides with the palms facing forward and thumbs pointing away from the body, and head and eyes directed straight ahead. In addition, the arms are usually placed slightly apart from the body so that the hands do not touch the sides. The positions of the limbs, particularly the arms, have important implications for directional terms in those appendages.

The basis for the standard anatomical position in humans comes from the supine position used for examining human cadavers during autopsies. Dissection of cadavers was one of the primary ways humans learned about anatomy throughout history, which has tremendously influenced the ways by which anatomical knowledge has developed into the scientific field of today.

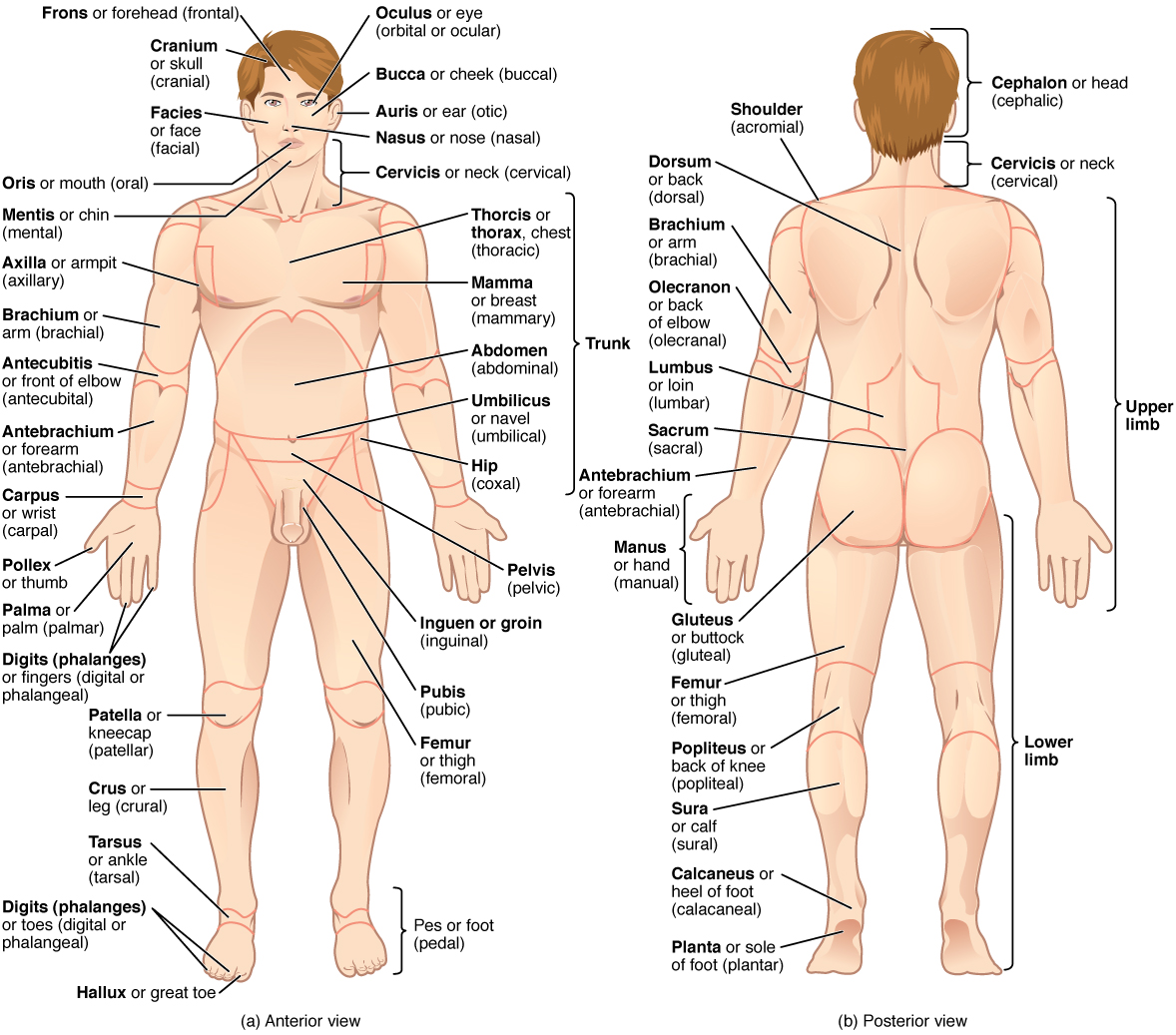

Standard anatomical position : The regions of the body in standard anatomical position, in which the body is erect.

In humans, the standard anatomical position of the skull is called the Frankfurt plane. In this position, the orbitales (eye sockets), lower margins of the orbits, and the poria (ear canal upper margins) all lie in the same horizontal plane. This orientation represents the position of the skull if the subject were standing upright and looking straight ahead.

It is important to note that all anatomical descriptions are based on the standard anatomical position unless otherwise stated.

1.6 Anatomical Terminology

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Demonstrate the anatomical position

- Describe the human body using directional and regional terms

- Identify three planes most commonly used in the study of anatomy

- Distinguish between the posterior (dorsal) and the anterior (ventral) body cavities, identifying their subdivisions and representative organs found in each

- Describe serous membrane and explain its function

Anatomists and health care providers use terminology that can be bewildering to the uninitiated. However, the purpose of this language is not to confuse, but rather to increase precision and reduce medical errors. For example, is a scar “above the wrist” located on the forearm two or three inches away from the hand? Or is it at the base of the hand? Is it on the palm-side or back-side? By using precise anatomical terminology, we eliminate ambiguity. Anatomical terms derive from ancient Greek and Latin words. Because these languages are no longer used in everyday conversation, the meaning of their words does not change.

Anatomical terms are made up of roots, prefixes, and suffixes. The root of a term often refers to an organ, tissue, or condition, whereas the prefix or suffix often describes the root. For example, in the disorder hypertension, the prefix “hyper-” means “high” or “over,” and the root word “tension” refers to pressure, so the word “hypertension” refers to abnormally high blood pressure.

Anatomical Position

To further increase precision, anatomists standardize the way in which they view the body. Just as maps are normally oriented with north at the top, the standard body “map,” or anatomical position , is that of the body standing upright, with the feet at shoulder width and parallel, toes forward. The upper limbs are held out to each side, and the palms of the hands face forward as illustrated in Figure 1.12 . Using this standard position reduces confusion. It does not matter how the body being described is oriented, the terms are used as if it is in anatomical position. For example, a scar in the “anterior (front) carpal (wrist) region” would be present on the palm side of the wrist. The term “anterior” would be used even if the hand were palm down on a table.

A body that is lying down is described as either prone or supine. Prone describes a face-down orientation, and supine describes a face up orientation. These terms are sometimes used in describing the position of the body during specific physical examinations or surgical procedures.

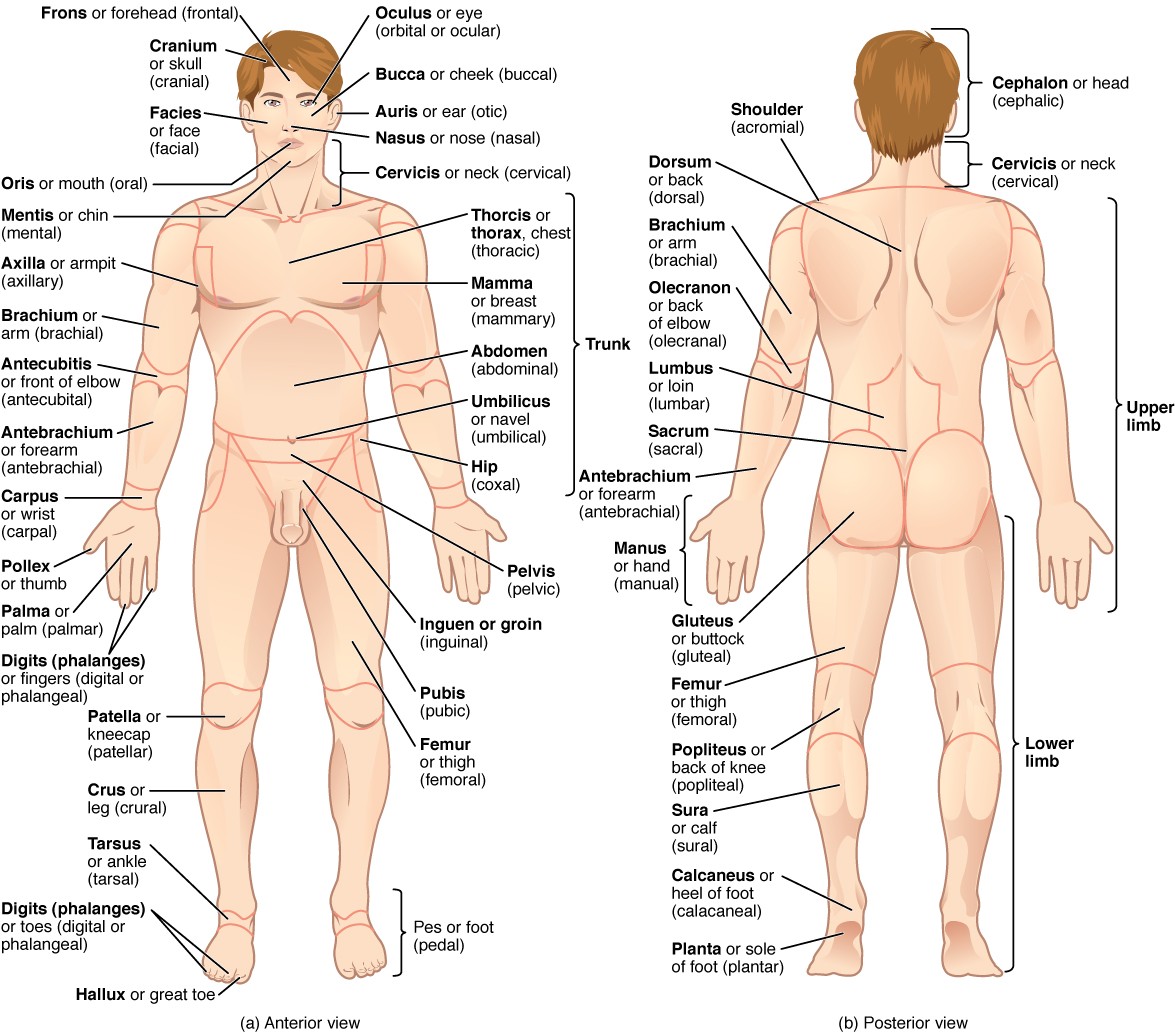

Regional Terms

The human body’s numerous regions have specific terms to help increase precision (see Figure 1.12 ). Notice that the term “brachium” or “arm” is reserved for the “upper arm” and “antebrachium” or “forearm” is used rather than “lower arm.” Similarly, “femur” or “thigh” is correct, and “leg” or “crus” is reserved for the portion of the lower limb between the knee and the ankle. You will be able to describe the body’s regions using the terms from the figure.

Directional Terms

Certain directional anatomical terms appear throughout this and any other anatomy textbook ( Figure 1.13 ). These terms are essential for describing the relative locations of different body structures. For instance, an anatomist might describe one band of tissue as “inferior to” another or a physician might describe a tumor as “superficial to” a deeper body structure. Commit these terms to memory to avoid confusion when you are studying or describing the locations of particular body parts.

- Anterior (or ventral ) Describes the front or direction toward the front of the body. The toes are anterior to the foot.

- Posterior (or dorsal ) Describes the back or direction toward the back of the body. The popliteus is posterior to the patella.

- Superior (or cranial ) describes a position above or higher than another part of the body proper. The orbits are superior to the oris.

- Inferior (or caudal ) describes a position below or lower than another part of the body proper; near or toward the tail (in humans, the coccyx, or lowest part of the spinal column). The pelvis is inferior to the abdomen.

- Lateral describes the side or direction toward the side of the body. The thumb (pollex) is lateral to the digits.

- Medial describes the middle or direction toward the middle of the body. The hallux is the medial toe.

- Proximal describes a position in a limb that is nearer to the point of attachment or the trunk of the body. The brachium is proximal to the antebrachium.

- Distal describes a position in a limb that is farther from the point of attachment or the trunk of the body. The crus is distal to the femur.

- Superficial describes a position closer to the surface of the body. The skin is superficial to the bones.

- Deep describes a position farther from the surface of the body. The brain is deep to the skull.

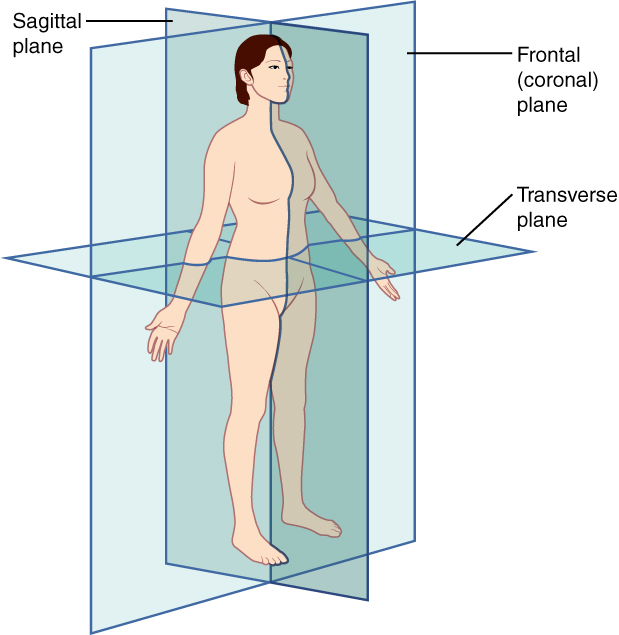

Body Planes

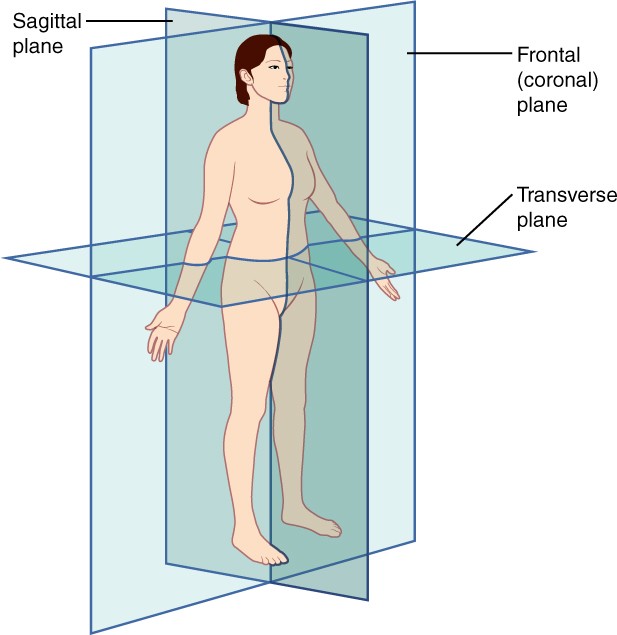

A section is a two-dimensional surface of a three-dimensional structure that has been cut. Modern medical imaging devices enable clinicians to obtain “virtual sections” of living bodies. We call these scans. Body sections and scans can be correctly interpreted, however, only if the viewer understands the plane along which the section was made. A plane is an imaginary two-dimensional surface that passes through the body. There are three planes commonly referred to in anatomy and medicine, as illustrated in Figure 1.14 .

- The sagittal plane is the plane that divides the body or an organ vertically into right and left sides. If this vertical plane runs directly down the middle of the body, it is called the midsagittal or median plane. If it divides the body into unequal right and left sides, it is called a parasagittal plane or less commonly a longitudinal section.

- The frontal plane is the plane that divides the body or an organ into an anterior (front) portion and a posterior (rear) portion. The frontal plane is often referred to as a coronal plane. (“Corona” is Latin for “crown.”)

- The transverse plane is the plane that divides the body or organ horizontally into upper and lower portions. Transverse planes produce images referred to as cross sections.

Body Cavities and Serous Membranes

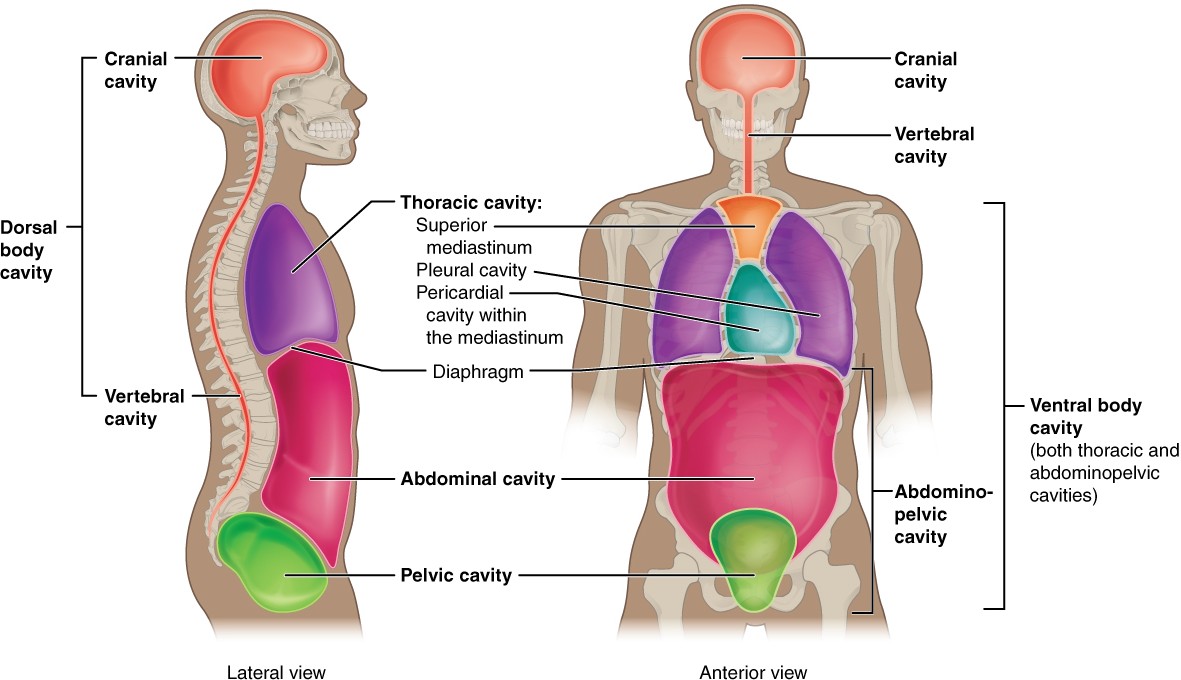

The body maintains its internal organization by means of membranes, sheaths, and other structures that separate compartments. The dorsal (posterior) cavity and the ventral (anterior) cavity are the largest body compartments ( Figure 1.15 ). These cavities contain and protect delicate internal organs, and the ventral cavity allows for significant changes in the size and shape of the organs as they perform their functions. The lungs, heart, stomach, and intestines, for example, can expand and contract without distorting other tissues or disrupting the activity of nearby organs.

Subdivisions of the Posterior (Dorsal) and Anterior (Ventral) Cavities

The posterior (dorsal) and anterior (ventral) cavities are each subdivided into smaller cavities. In the posterior (dorsal) cavity, the cranial cavity houses the brain, and the spinal cavity (or vertebral cavity) encloses the spinal cord. Just as the brain and spinal cord make up a continuous, uninterrupted structure, the cranial and spinal cavities that house them are also continuous. The brain and spinal cord are protected by the bones of the skull and vertebral column and by cerebrospinal fluid, a colorless fluid produced by the brain, which cushions the brain and spinal cord within the posterior (dorsal) cavity.

The anterior (ventral) cavity has two main subdivisions: the thoracic cavity and the abdominopelvic cavity (see Figure 1.15 ). The thoracic cavity is the more superior subdivision of the anterior cavity, and it is enclosed by the rib cage. The thoracic cavity contains the lungs and the heart, which is located in the mediastinum. The diaphragm forms the floor of the thoracic cavity and separates it from the more inferior abdominopelvic cavity. The abdominopelvic cavity is the largest cavity in the body. Although no membrane physically divides the abdominopelvic cavity, it can be useful to distinguish between the abdominal cavity, the division that houses the digestive organs, and the pelvic cavity, the division that houses the organs of reproduction.

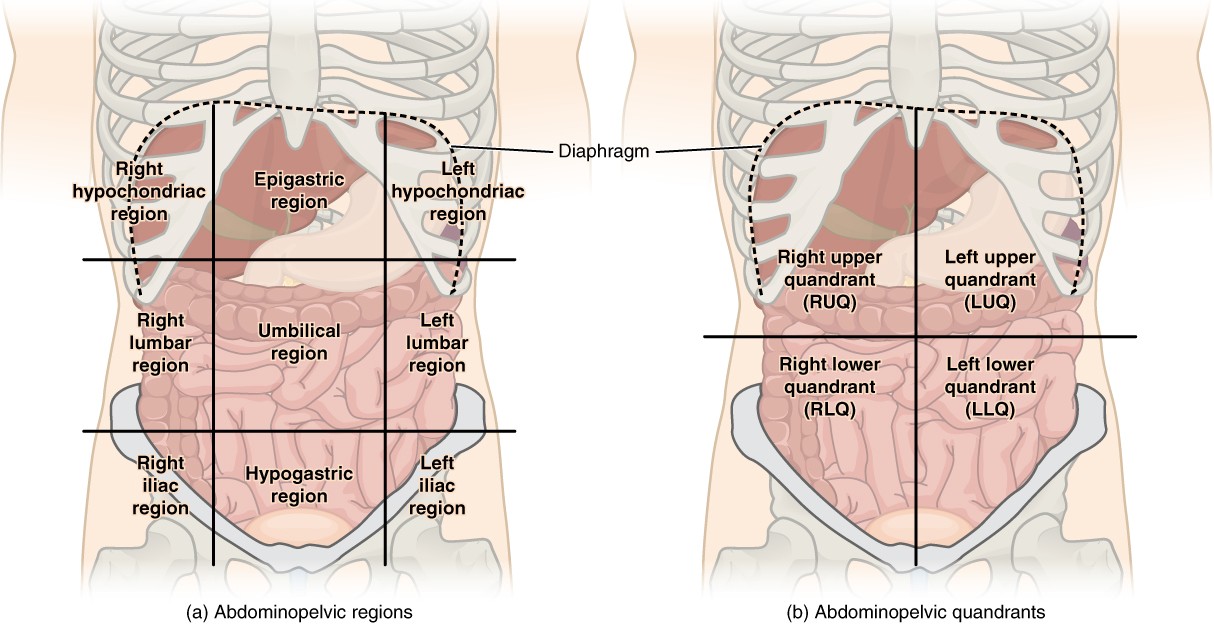

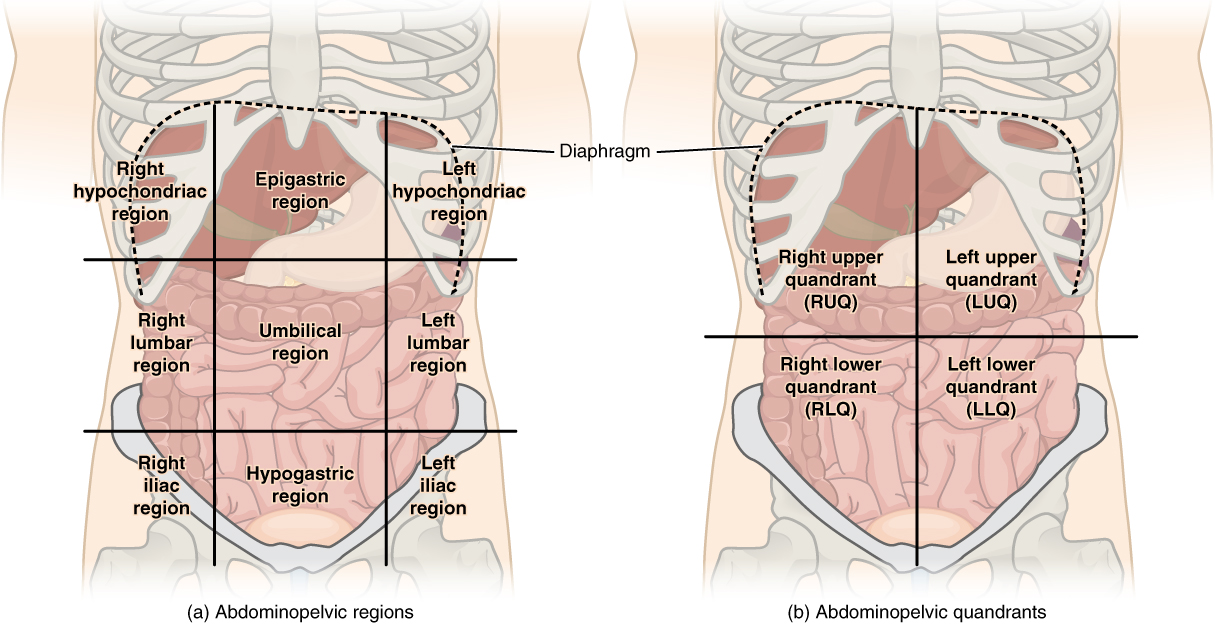

Abdominal Regions and Quadrants

To promote clear communication, for instance about the location of a patient’s abdominal pain or a suspicious mass, health care providers typically divide up the cavity into either nine regions or four quadrants ( Figure 1.16 ).

The more detailed regional approach subdivides the cavity with one horizontal line immediately inferior to the ribs and one immediately superior to the pelvis, and two vertical lines drawn as if dropped from the midpoint of each clavicle (collarbone). There are nine resulting regions. The simpler quadrants approach, which is more commonly used in medicine, subdivides the cavity with one horizontal and one vertical line that intersect at the patient’s umbilicus (navel).

Membranes of the Anterior (Ventral) Body Cavity

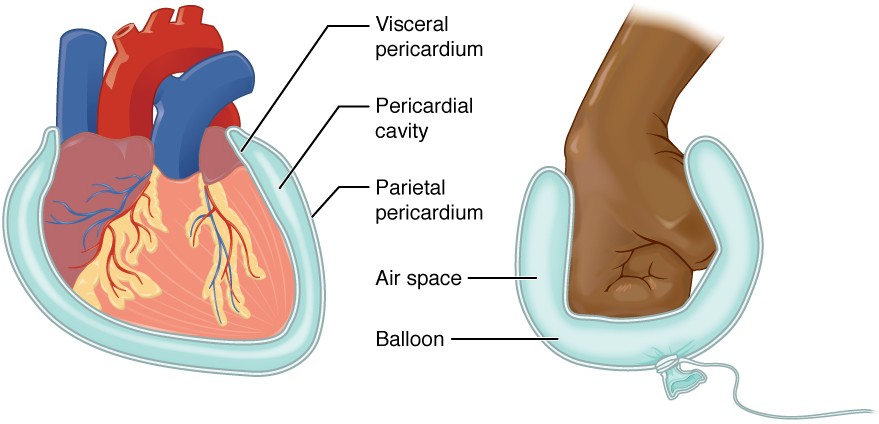

A serous membrane (also referred to a serosa) is one of the thin membranes that cover the walls and organs in the thoracic and abdominopelvic cavities. The parietal layers of the membranes line the walls of the body cavity (pariet- refers to a cavity wall). The visceral layer of the membrane covers the organs (the viscera). Between the parietal and visceral layers is a very thin, fluid-filled serous space, or cavity ( Figure 1.17 ).

There are three serous cavities and their associated membranes. The pleura is the serous membrane that encloses the pleural cavity; the pleural cavity surrounds the lungs. The pericardium is the serous membrane that encloses the pericardial cavity; the pericardial cavity surrounds the heart. The peritoneum is the serous membrane that encloses the peritoneal cavity; the peritoneal cavity surrounds several organs in the abdominopelvic cavity. The serous membranes form fluid-filled sacs, or cavities, that are meant to cushion and reduce friction on internal organs when they move, such as when the lungs inflate or the heart beats. Both the parietal and visceral serosa secrete the thin, slippery serous fluid located within the serous cavities. The pleural cavity reduces friction between the lungs and the body wall. Likewise, the pericardial cavity reduces friction between the heart and the wall of the pericardium. The peritoneal cavity reduces friction between the abdominal and pelvic organs and the body wall. Therefore, serous membranes provide additional protection to the viscera they enclose by reducing friction that could lead to inflammation of the organs.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: J. Gordon Betts, Kelly A. Young, James A. Wise, Eddie Johnson, Brandon Poe, Dean H. Kruse, Oksana Korol, Jody E. Johnson, Mark Womble, Peter DeSaix

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Anatomy and Physiology 2e

- Publication date: Apr 20, 2022

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/1-6-anatomical-terminology

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 1: AN INTRODUCTION TO THE HUMAN BODY

Introduction.

Chapter Objectives

After studying this chapter, you will be able to:

- Distinguish between anatomy and physiology

- Describe the structure of the body, from simplest to most complex

- Use appropriate anatomical terminology to identify key body structures, body regions, and directions in the body

This chapter begins with an overview of anatomy and a preview of the body regions and functions. It introduces a set of standard terms for body structures and for planes and positions in the body that will serve as a foundation for more comprehensive information covered later in the text.

Though you may approach a course in anatomy and physiology strictly as a requirement for your field of study, the knowledge you gain in this course will serve you well in many aspects of your life. An understanding of anatomy and physiology is fundamental to any career in the healthcare.

Overview of Anatomy and Physiology

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Compare and contrast anatomy and physiology

Human anatomy is the scientific study of the body’s structures. Some of these structures are very small and can only be observed and analyzed with the assistance of a microscope. Other larger structures can readily be seen, manipulated, measured, and weighed. The word “anatomy” comes from a Greek root that means “to cut apart.” Human anatomy was first studied by observing the exterior of the body and observing the wounds of soldiers and other injuries. Later, physicians were allowed to dissect bodies of the dead to augment their knowledge. When a body is dissected, its structures are cut apart in order to observe their physical attributes and their relationships to one another. Dissection is still used in medical schools, anatomy courses, and in pathology labs. In order to observe structures in living people, however, a number of imaging techniques have been developed. These techniques allow clinicians to visualize structures inside the living body such as a cancerous tumor or a fractured bone.

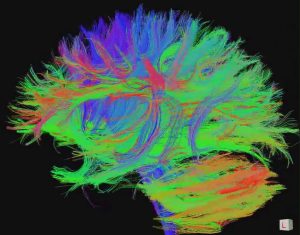

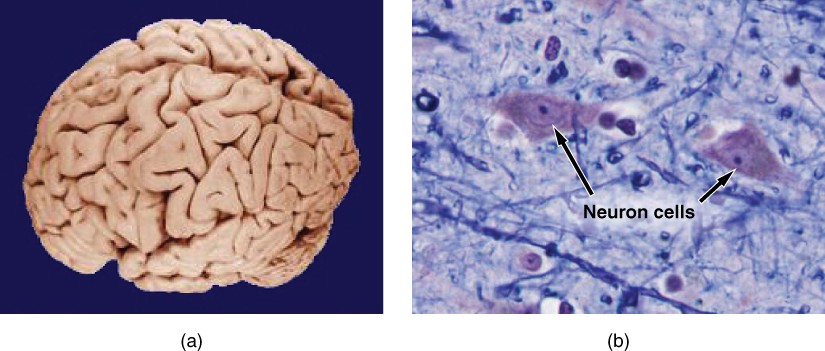

Like most scientific disciplines, anatomy has areas of specialisation. Gross anatomy is the study of the larger structures of the body, those visible without the aid of magnification ( Figure 1.2 a ). Macro- means “large,” thus, gross anatomy is also referred to as macroscopic anatomy. In contrast, micro- means “small,” and microscopic anatomy is the study of structures that can be observed only with the use of a microscope or other magnification devices ( Figure 1.2 b ). Microscopic anatomy includes cytology, the study of cells and histology, the study of tissues. As the technology of microscopes has advanced, anatomists have been able to observe smaller and smaller structures of the body, from slices of large structures like the heart, to the three-dimensional structures of large molecules in the body.

Figure 1.2 Gross and Microscopic Anatomy (a) Gross anatomy considers large structures such as the brain. (b) Microscopic anatomy can deal with the same structures, though at a different scale. This is a micrograph of nerve cells from the brain. LM × 1600. [credit a: “WriterHound”/Wikimedia Commons; credit b: Micrograph provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012]

Anatomists take two general approaches to the study of the body’s structures: regional and systemic. Regional anatomy is the study of the interrelationships of all of the structures in a specific body region, such as the abdomen. Studying regional anatomy helps us appreciate the interrelationships of body structures, such as how muscles, nerves, blood vessels, and other structures work together to serve a particular body region. In contrast, systemic anatomy is the study of the structures that make up a discrete body system—that is, a group of structures that work together to perform a unique body function. For example, a systemic anatomical study of the muscular system would consider all of the skeletal muscles of the body.

Whereas anatomy is about structure, physiology is about function. Human physiology is the scientific study of the chemistry and physics of the structures of the body and the ways in which they work together to support the functions of life. Much of the study of physiology centers on the body’s tendency toward homeostasis. Homeostasis is the state of steady internal conditions maintained by living things. The study of physiology certainly includes observation, both with the naked eye and with microscopes, as well as manipulations and measurements.

Form is closely related to function in all living things. For example, the thin flap of your eyelid can snap down to clear away dust particles and almost instantaneously slide back up to allow you to see again. At the microscopic level, the arrangement and function of the nerves and muscles that serve the eyelid allow for its quick action and retreat. At a smaller level of analysis, the function of these nerves and muscles likewise relies on the interactions of specific molecules and ions. Even the three-dimensional structure of certain molecules is essential to their function.

Structural Organisation of the Human Body

- Describe the structure of the human body in terms of six levels of organization

- List the eleven organ systems of the human body

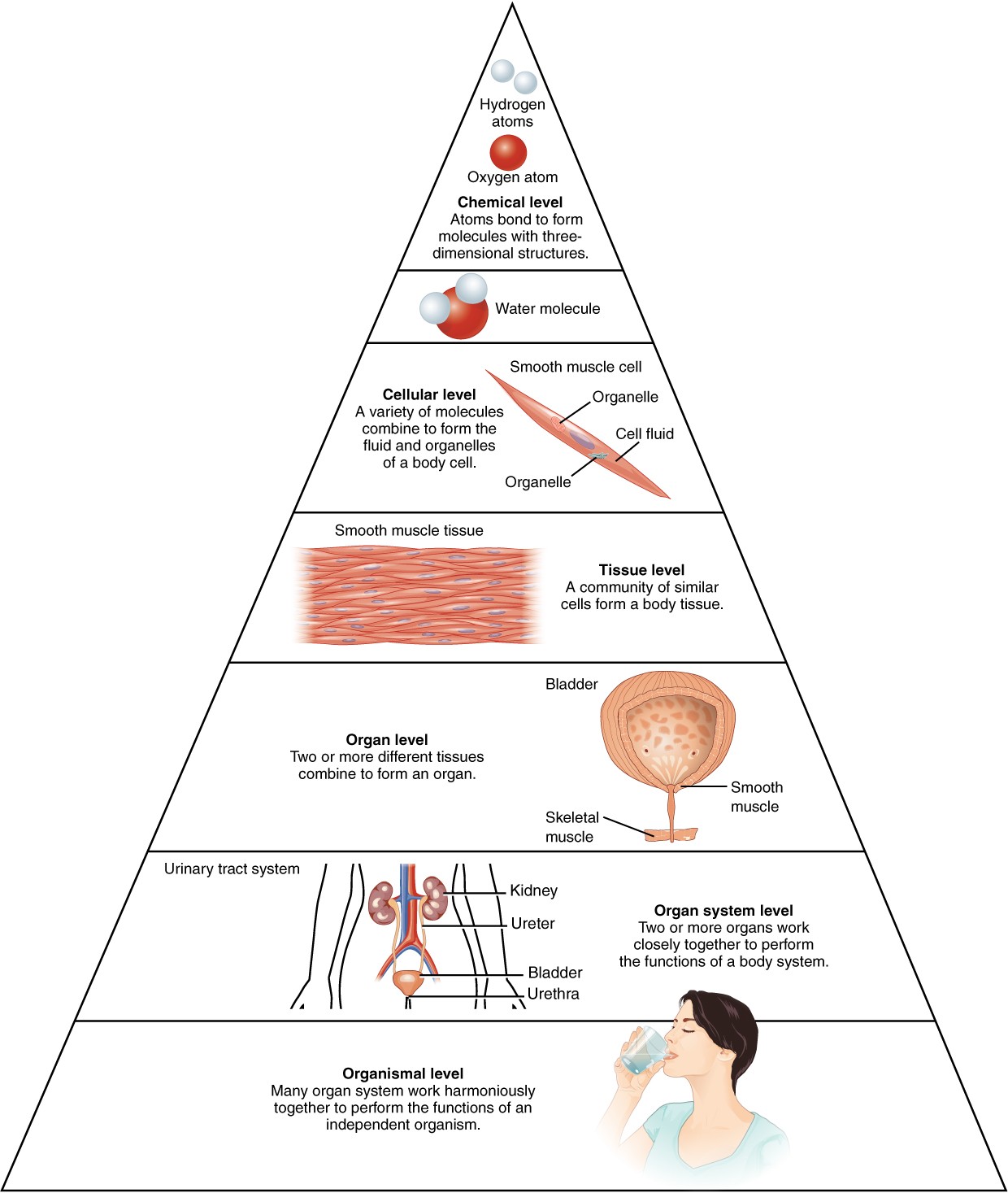

Before you begin to study the different structures of the human body, it is helpful to consider its basic architecture; that is, how its smallest parts are assembled into larger structures. It is convenient to consider the structures of the body in terms of fundamental levels of organization that increase in complexity: subatomic particles, atoms, molecules, organelles, cells, tissues, organs, organ systems, organisms and biosphere ( Figure 1.3 ).

Figure 1.3 Levels of Structural Organisation of the Human Body The organisation of the body often is discussed in terms of six distinct levels of increasing complexity, from the smallest chemical building blocks to a unique human organism.

The Levels of Organisation

A cell is the smallest independently functioning unit of a living organism. Even bacteria, which are extremely small, independently-living organisms, have a cellular structure. Each bacterium is a single cell. All living structures of human anatomy contain cells.

A human cell typically consists of flexible membranes that enclose cytoplasm, a water-based cellular fluid together with a variety of tiny functioning units called organelles . In humans, as in all organisms, cells perform all functions of life. A tissue is a group of many similar cells (though sometimes composed of a few related types) that work together to perform a specific function. An organ is an anatomically distinct structure of the body composed of two or more tissue types. Each organ performs one or more specific physiological functions. An organ system is a group of organs that work together to perform major functions or meet physiological needs of the body. The human body is comprised of eleven distinct organ systems.

INTERACTIVE ACTIVITY

The organism level is the highest level of organisation. An organism is a living being that has a cellular structure and that can independently perform all physiologic functions necessary for life. In multicellular organisms, including humans, all cells, tissues, organs, and organ systems of the body work together to maintain the life and health of the organism.

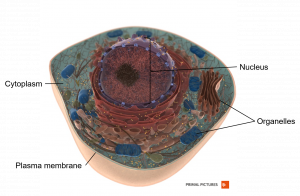

- Describe the basic structure of the cell

The body contains at least 200 distinct cell types. These cells contain essentially the same internal structures yet they vary enormously in shape and function. The different types of cells are not randomly distributed throughout the body; rather they occur in organized layers, a level of organization referred to as tissue.

The variety in shape reflects the many different roles that cells fulfill in your body. The human body starts as a single cell at fertilization. As this fertilized egg divides, it gives rise to trillions of cells, each built from the same blueprint, but organizing into tissues and becoming irreversibly committed to a developmental pathway. Despite differences in structure and function, all living cells in multicellular organisms have a surrounding cell membrane. As the outer layer of your skin separates your body from its environment, the cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane) separates the inner contents of a cell from its exterior environment. The cell membrane is an extremely pliable structure composed primarily of back-to-back phospholipids (a “bilayer”). This cell membrane provides a protective barrier around the cell and regulates which materials can pass in or out.

Now that you have learned that the cell membrane surrounds all cells, you can dive inside of a prototypical human cell to learn about its internal components and their functions. All living cells in multicellular organisms contain an internal cytoplasmic compartment, and a nucleus within the cytoplasm. Cytosol , the jelly-like substance within the cell, provides the fluid medium necessary for biochemical reactions. Eukaryotic cells also contain various cellular organelles. An organelle (“little organ”) is one of several different types of membrane-enclosed bodies in the cell, each performing a unique function. Just as the various bodily organs work together in harmony to perform all of a human’s functions, the many different cellular organelles work together to keep the cell healthy and performing all of its important functions. The organelles and cytosol, taken together, compose the cell’s cytoplasm . The nucleus is a cell’s central organelle, which contains the cell’s DNA ( Figure 3.13 ). The nucleus is generally considered the control center of the cell because it stores all of the genetic instructions for manufacturing proteins.

Figure 3.13 Prototypical Human Cell While this image is not indicative of any one particular human cell, it is a prototypical example of a cell containing the primary components. [Created in Anatomy.TV, Primal Pictures]

Types of Tissues

- Identify and describe the four main tissue types

- Identify and describe the main types of tissue membranes

The term tissue is used to describe a group of cells found together in the body. The cells within a tissue share a common embryonic origin. Microscopic observation reveals that the cells in a tissue share morphological features and are arranged in an orderly pattern that achieves the tissue’s functions.

Although there are many types of cells in the human body, they are organized into four broad categories of tissues: epithelial, connective, muscle, and nervous. Each of these categories is characterized by specific functions that contribute to the overall health and maintenance of the body. A disruption of the structure is a sign of injury or disease. Such changes can be detected through histology , the microscopic study of tissue appearance, organization, and function.

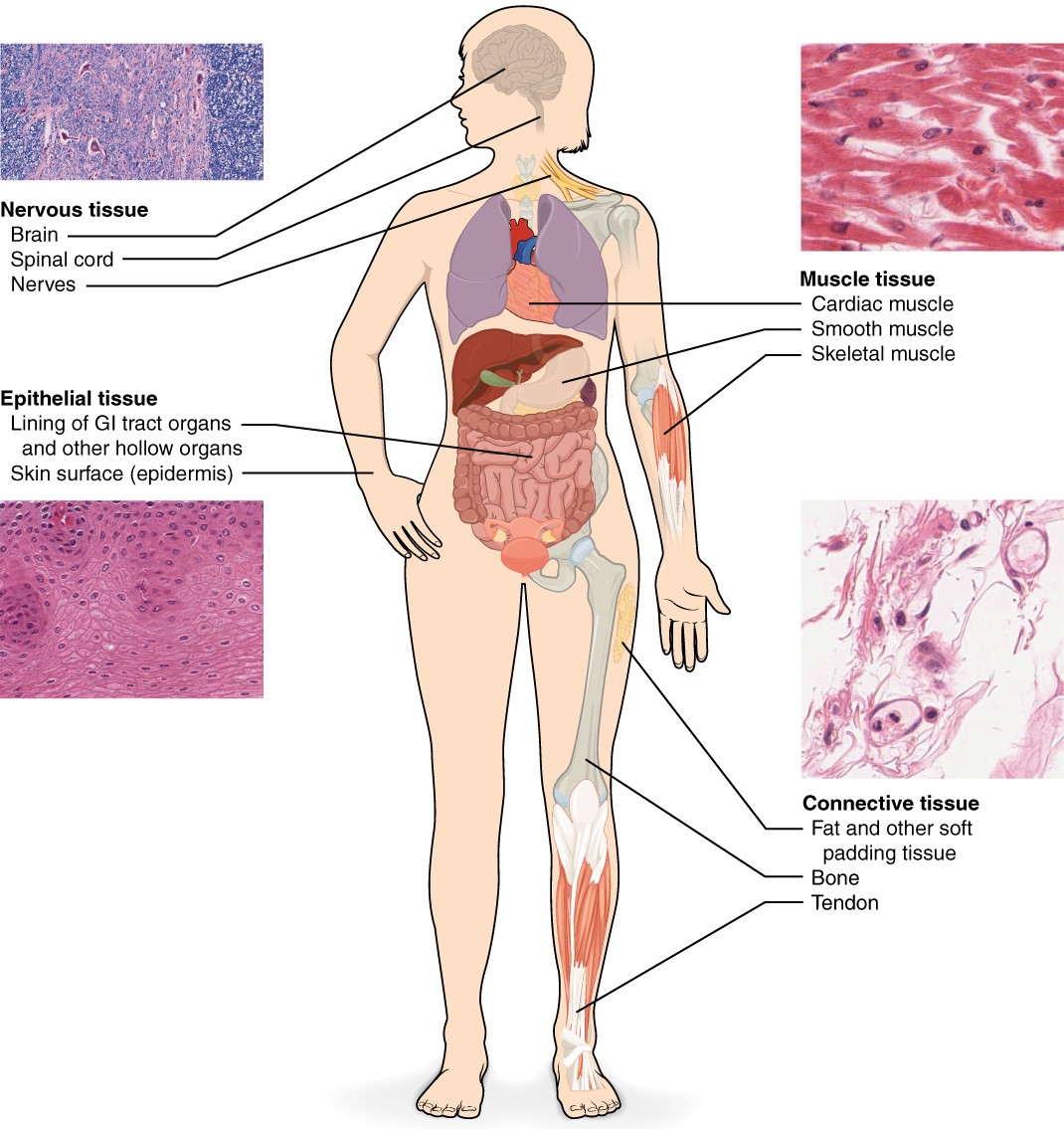

The Four Types of Tissues

Epithelial tissue , also referred to as epithelium, refers to the sheets of cells that cover exterior surfaces of the body, lines internal cavities and passageways, and forms certain glands. Connective tissue , as its name implies, binds the cells and organs of the body together and functions in the protection, support, and integration of all parts of the body. Muscle tissue is excitable, responding to stimulation and contracting to provide movement, and occurs as three major types: skeletal (voluntary) muscle, smooth muscle, and cardiac muscle in the heart. Nervous tissue is also excitable, allowing the propagation of electrochemical signals in the form of nerve impulses that communicate between different regions of the body ( Figure 4.2 ).

The next level of organization is the organ, where several types of tissues come together to form a working unit. Just as knowing the structure of cells helps you in your study of tissues, knowledge of tissues will help you to identify and describe the structure of organs. The epithelial and connective tissues are discussed in detail in this chapter. Muscle and nervous tissues will be discussed only briefly in this chapter.

Figure 4.2 Four Types of Tissue: Body The four types of tissues are exemplified in nervous tissue, stratified squamous epithelial tissue, cardiac muscle tissue, and connective tissue in small intestine. Clockwise from nervous tissue, LM × 872, LM × 282, LM × 460, LM × 800. [Micrographs provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012]

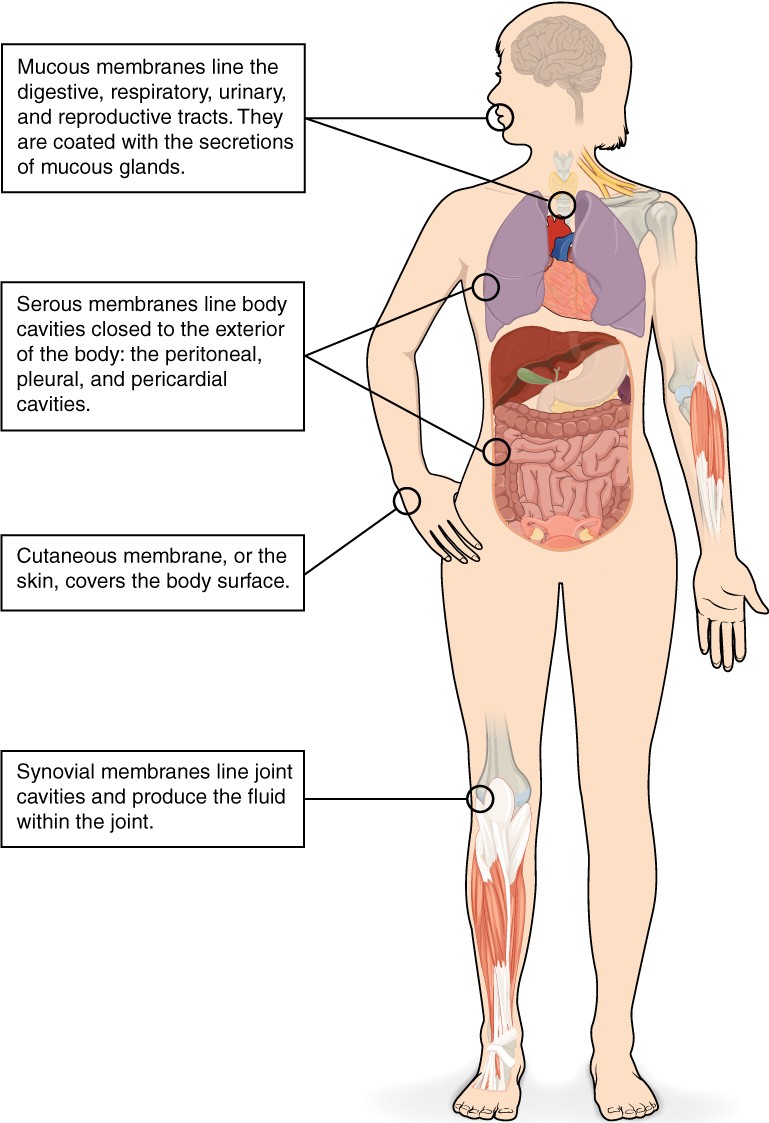

Tissue Membranes

A tissue membrane is a thin layer or sheet of cells that covers the outside of the body (for example, skin), the organs (for example, pericardium), internal passageways that lead to the exterior of the body (for example, abdominal mesenteries), and the lining of the moveable joint cavities. There are two basic types of tissue membranes: connective tissue and epithelial membranes ( Figure 4.3 ).

Figure 4.3 Tissue Membranes The two broad categories of tissue membranes in the body are (1) connective tissue membranes, which include synovial membranes, and (2) epithelial membranes, which include mucous membranes, serous membranes, and the cutaneous membrane, in other words, the skin.

Anatomical Terminology

- Demonstrate the anatomical position

- Describe the human body using directional and regional terms

- Identify three planes most commonly used in the study of anatomy

- Distinguish between the posterior (dorsal) and the anterior (ventral) body cavities, identifying their subdivisions and representative organs found in each

- Describe serous membrane location and structure

Anatomists and health care providers use terminology that can be challenging to remember. However, the purpose of this language is not to confuse, but rather to increase precision and reduce medical errors. For example, is a scar “above the wrist” located on the forearm two or three inches away from the hand? Or is it at the base of the hand? Is it on the palm- side or back-side? By using precise anatomical terminology, we eliminate ambiguity. Anatomical terms derive from ancient Greek and Latin words. Because these languages are no longer used in everyday conversation, the meaning of their words does not change.

Anatomical terms are made up of roots, prefixes, and suffixes. The root of a term often refers to an organ, tissue, or condition, whereas the prefix or suffix often describes the root. For example, in the disorder hypertension, the prefix “hyper- ” means “high” or “over,” and the root word “tension” refers to pressure, so the word “hypertension” refers to abnormally high blood pressure.

Anatomical Position

To further increase precision, anatomists standardise the way in which they view the body. Just as maps are normally oriented with north at the top, the standard body “map,” or anatomical position , is that of the body standing upright, with the feet at shoulder width and parallel, toes forward. The upper limbs are held out to each side, and the palms of the hands face forward as illustrated in Figure 1.12 . Using this standard position reduces confusion. It does not matter how the body being described is oriented, the terms are used as if it is in anatomical position. For example, a scar in the “anterior (front) carpal (wrist) region” would be present on the palm side of the wrist. The term “anterior” would be used even if the hand were palm down on a table.

Figure 1.12 Regions of the Human Body The human body is shown in anatomical position in an (a) anterior view and a (b) posterior view. The regions of the body are labeled in boldface.

A body that is lying down is described as either prone or supine. Prone describes a face-down orientation, and supine describes a face up orientation. These terms are sometimes used in describing the position of the body during specific physical examinations or surgical procedures.

Regional Terms

The human body’s numerous regions have specific terms to help increase precision (see Figure 1.12 ). Notice that the term “brachium” or “arm” is reserved for the “upper arm” and “antebrachium” or “forearm” is used rather than “lower arm.” Similarly, “femur” or “thigh” is correct, and “leg” or “crus” is reserved for the portion of the lower limb between the knee and the ankle. You will be able to describe the body’s regions using the terms from the figure.

INTERACTIVE LINK

Explore the body plan organisation in this interactive lesson from Anatomy.TV (Primal Pictures). Simply click on any topic you are interested in to learn more. Note: In order for the embedded Anatomy.TV content to open and run correctly, you first need to click the following link to login to the Anatomy.TV database from the QUT library – it will open in a new tab, so leave that tab open in the background. When you return to this page, you may then need to refresh it (press the F5 key).

https://libguides.library.qut.edu.au/databases/anatomytv

Directional Terms

Certain directional anatomical terms appear throughout this and any other anatomy textbook ( Figure 1.13 ). These terms are essential for describing the relative locations of different body structures. For instance, an anatomist might describe one band of tissue as “inferior to” another or a physician might describe a tumor as “superficial to” a deeper body structure. Commit these terms to memory to avoid confusion when you are studying or describing the locations of particular body parts.

- Anterior (or ventral ) Describes the front or direction toward the front of the body. The toes are anterior to the foot.

- Posterior (or dorsal ) Describes the back or direction toward the back of the body. The popliteus is posterior to the patella.

- Superior (or cranial ) describes a position above or higher than another part of the body proper. The orbits are superior to the oris.

- Inferior (or caudal ) describes a position below or lower than another part of the body proper; near or toward the tail (in humans, the coccyx, or lowest part of the spinal column). The pelvis is inferior to the abdomen.

- Lateral describes the side or direction toward the side of the body. The thumb (pollex) is lateral to the digits.

- Medial describes the middle or direction toward the middle of the body. The hallux is the medial toe.

- Proximal describes a position in a limb that is nearer to the point of attachment or the trunk of the body. The brachium is proximal to the antebrachium.

- Distal describes a position in a limb that is farther from the point of attachment or the trunk of the body. The crus is distal to the femur.

- Superficial describes a position closer to the surface of the body. The skin is superficial to the bones.

- Deep describes a position farther from the surface of the body. The brain is deep to the skull.

Figure 1.13 Directional Terms Applied to the Human Body Paired directional terms are shown as applied to the human body.

Body Planes

A section is a two-dimensional surface of a three-dimensional structure that has been cut. Modern medical imaging devices enable clinicians to obtain “virtual sections” of living bodies. We call these scans. Body sections and scans can be correctly interpreted, however, only if the viewer understands the plane along which the section was made. A plane is an imaginary two-dimensional surface that passes through the body. There are three planes commonly referred to in anatomy and medicine, as illustrated in Figure 1.14 .

- The sagittal plane is the plane that divides the body or an organ vertically into right and left sides. If this vertical plane runs directly down the middle of the body, it is called the midsagittal or median plane. If it divides the body into unequal right and left sides, it is called a parasagittal plane or less commonly a longitudinal section.

- The frontal plane is the plane that divides the body or an organ into an anterior (front) portion and a posterior (rear) portion. The frontal plane is often referred to as a coronal plane. (“Corona” is Latin for “crown.”)

- The transverse plane is the plane that divides the body or organ horizontally into upper and lower portions. Transverse planes produce images referred to as cross sections.

Figure 1.14 Planes of the Body The three planes most commonly used in anatomical and medical imaging are the sagittal, frontal (or coronal), and transverse plane.

Body Cavities and Serous Membranes

The body maintains its internal organization by means of membranes, sheaths, and other structures that separate compartments. The dorsal (posterior) cavity and the ventral (anterior) cavity are the largest body compartments ( Figure 1.15 ). These cavities contain and protect delicate internal organs, and the ventral cavity allows for significant changes in the size and shape of the organs as they perform their functions. The lungs, heart, stomach, and intestines, for example, can expand and contract without distorting other tissues or disrupting the activity of nearby organs.

Figure 1.15 Dorsal and Ventral Body Cavities The ventral cavity includes the thoracic and abdominopelvic cavities and their subdivisions. The dorsal cavity includes the cranial and vertebral (spinal) cavities.

Subdivisions of the Posterior (Dorsal) and Anterior (Ventral) Cavities

The posterior (dorsal) and anterior (ventral) cavities are each subdivided into smaller cavities. In the posterior (dorsal) cavity, the cranial cavity houses the brain, and the vertebral cavity (or spinal cavity) encloses the spinal cord. Just as the brain and spinal cord make up a continuous, uninterrupted structure, the cranial and vertebral cavities that house them are also continuous. The brain and spinal cord are protected by the bones of the skull and vertebral column and by cerebrospinal fluid, a colorless fluid produced by the brain, which cushions the brain and spinal cord within the posterior (dorsal) cavity.

The anterior (ventral) cavity has two main subdivisions: the thoracic cavity and the abdominopelvic cavity (see Figure 1.15 ). The thoracic cavity is the more superior subdivision of the anterior cavity, and it is enclosed by the rib cage. The thoracic cavity contains the lungs and the heart, which is located in the mediastinum. The diaphragm forms the floor of the thoracic cavity and separates it from the more inferior abdominopelvic cavity. The abdominopelvic cavity is the largest cavity in the body. Although no membrane physically divides the abdominopelvic cavity, it can be useful to distinguish between the abdominal cavity, the division that houses the digestive organs, and the pelvic cavity, the division that houses the organs of reproduction.

Abdominal Regions and Quadrants

To promote clear communication, for instance about the location of a patient’s abdominal pain or a suspicious mass, health care providers typically divide up the cavity into either nine regions or four quadrants ( Figure 1.16 ).

Figure 1.16 Regions and Quadrants of the Peritoneal Cavity There are (a) nine abdominal regions and (b) four abdominal quadrants in the peritoneal cavity.

The more detailed regional approach subdivides the cavity with one horizontal line immediately inferior to the ribs and one immediately superior to the pelvis, and two vertical lines drawn as if dropped from the midpoint of each clavicle (collarbone). There are nine resulting regions. The simpler quadrants approach, which is more commonly used in medicine, subdivides the cavity with one horizontal and one vertical line that intersect at the patient’s umbilicus (navel).

Membranes of the Anterior (Ventral) Body Cavity

A serous membrane (also referred to a serosa) is one of the thin membranes that cover the walls and organs in the thoracic and abdominopelvic cavities. The parietal layers of the membranes line the walls of the body cavity (pariet- refers to a cavity wall). The visceral layer of the membrane covers the organs (the viscera). Between the parietal and visceral layers is a very thin, fluid-filled serous space, or cavity ( Figure 1.17 ).

Figure 1.17 Serous Membrane Serous membrane lines the pericardial cavity and reflects back to cover the heart—much the same way that an underinflated balloon would form two layers surrounding a fist.

There are three serous cavities and their associated membranes. The pleura is the serous membrane that surrounds the lungs in the pleural cavity; the pericardium is the serous membrane that surrounds the heart in the pericardial cavity; and the peritoneum is the serous membrane that surrounds several organs in the abdominopelvic cavity.The serous membranes form fluid-filled sacs, or cavities, that are meant to cushion and reduce friction on internal organs when they move, such as when the lungs inflate or the heart beats. Both the parietal and visceral serosa secrete the thin, slippery serous fluid located within the serous cavities. The pleural cavity reduces friction between the lungs and the body wall. Likewise, the pericardial cavity reduces friction between the heart and the wall of the pericardium. The peritoneal cavity reduces friction between the abdominal and pelvic organs and the body wall. Therefore, serous membranes provide additional protection to the viscera they enclose by reducing friction that could lead to inflammation of the organs.

abdominopelvic cavity division of the anterior (ventral) cavity that houses the abdominal and pelvic viscera

anatomical position standard reference position used for describing locations and directions on the human body

anatomy science that studies the form and composition of the body’s structures

anterior describes the front or direction toward the front of the body; also referred to as ventral

anterior cavity larger body cavity located anterior to the posterior (dorsal) body cavity; includes the serous membrane- lined pleural cavities for the lungs, pericardial cavity for the heart, and peritoneal cavity for the abdominal and pelvic organs; also referred to as ventral cavity

caudal describes a position below or lower than another part of the body proper; near or toward the tail (in humans, the coccyx, or lowest part of the spinal column); also referred to as inferior

cell smallest independently functioning unit of all organisms; in animals, a cell contains cytoplasm, composed of fluid and organelles

control centre compares values to their normal range; deviations cause the activation of an effector

cranial describes a position above or higher than another part of the body proper; also referred to as superior

cranial cavity division of the posterior (dorsal) cavity that houses the brain

deep describes a position farther from the surface of the body

development changes an organism goes through during its life

distal describes a position farther from the point of attachment or the trunk of the body

dorsal describes the back or direction toward the back of the body; also referred to as posterior

dorsal cavity posterior body cavity that houses the brain and spinal cord; also referred to the posterior body cavity

frontal plane two-dimensional, vertical plane that divides the body or organ into anterior and posterior portions

gross anatomy study of the larger structures of the body, typically with the unaided eye; also referred to macroscopic anatomy

growth process of increasing in size

homeostasis steady state of body systems that living organisms maintain

inferior describes a position below or lower than another part of the body proper; near or toward the tail (in humans, the coccyx, or lowest part of the spinal column); also referred to as caudal

lateral describes the side or direction toward the side of the body

medial describes the middle or direction toward the middle of the body

microscopic anatomy study of very small structures of the body using magnification

organ functionally distinct structure composed of two or more types of tissues

organ system group of organs that work together to carry out a particular function

organism living being that has a cellular structure and that can independently perform all physiologic functions necessary for life

pericardium sac that encloses the heart

peritoneum serous membrane that lines the abdominopelvic cavity and covers the organs found there

physiology science that studies the chemistry, biochemistry, and physics of the body’s functions

plane imaginary two-dimensional surface that passes through the body

pleura serous membrane that lines the pleural cavity and covers the lungs

posterior describes the back or direction toward the back of the body; also referred to as dorsal

posterior cavity posterior body cavity that houses the brain and spinal cord; also referred to as dorsal cavity

pressure force exerted by a substance in contact with another substance

prone face down

proximal describes a position nearer to the point of attachment or the trunk of the body

regional anatomy study of the structures that contribute to specific body regions

sagittal plane two-dimensional, vertical plane that divides the body or organ into right and left sides

section in anatomy, a single flat surface of a three-dimensional structure that has been cut through

serosa membrane that covers organs and reduces friction; also referred to as serous membrane

serous membrane membrane that covers organs and reduces friction; also referred to as serosa

superficial describes a position nearer to the surface of the body

superior describes a position above or higher than another part of the body proper; also referred to as cranial

supine face up

systemic anatomy study of the structures that contribute to specific body systems

thoracic cavity division of the anterior (ventral) cavity that houses the heart, lungs, esophagus, and trachea

tissue group of similar or closely related cells that act together to perform a specific function

transverse plane two-dimensional, horizontal plane that divides the body or organ into superior and inferior portions

ventral describes the front or direction toward the front of the body; also referred to as anterior

ventral cavity larger body cavity located anterior to the posterior (dorsal) body cavity; includes the serous membrane- lined pleural cavities for the lungs, pericardial cavity for the heart, and peritoneal cavity for the abdominal and pelvic organs; also referred to as anterior body cavity

vertebral cavity division of the dorsal cavity that houses the spinal cord; also referred to as vertebral cavity

Chapter 1: AN INTRODUCTION TO THE HUMAN BODY Copyright © 2020 by Queensland University of Technology. All Rights Reserved.

Share This Book

- Lesson Plans

- Technology in Education

Welcome to the Visible Body Blog!

Free lesson plan: anatomical planes, positions, and directional terms.

Posted on 3/6/20 by Laura Snider

For students, the beginning of an A&P course can feel like wading through a sea of confusing new terminology. Who knew there were so many ways to describe where things are located in the body, or how the body is positioned, or what plane a cross-section is on?

If you’re looking for a way to help your students navigate these concepts, Visible Body is here to help! 3D visualization of human anatomy is our specialty, after all.

Check out our video on planes, positions, and directional terms!

Here are some short class (or homework) activities in Visible Body Suite that your students can do to explore anatomical planes, positions, and directional terms!

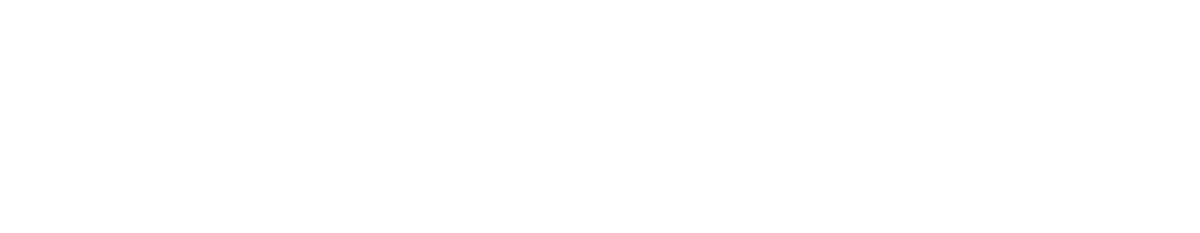

Use Gross Anatomy Lab (GAL) views to distinguish between prone and supine positions

One of the principal distinctions students need to understand is the difference between prone and supine anatomical positions. In this class activity, students will use the Gross Anatomy Lab views in VB Suite to explore the differences in dissecting models in prone and supine positions.

First, have students select the first GAL view (Back) in VB Suite. If there is space in the lab or classroom for them to do so, they can interact with the 3D model in AR mode.

Students should explore this view, dissecting away layers of skin and muscle to see which internal structures are easiest to access with the model in the prone position. They can switch between a male and a female model via the settings button.

When they’re finished examining the model in the prone position, they should hit the refresh button at the top of the screen to bring back all the structures they dissected away. Then, they should use the “supine” button in the info box to flip the model over.

From there, they can explore the male and female models in supine position.

Have students discuss with a partner why it might be important for certain medical and imaging procedures to position the patient in either a prone or supine orientation.

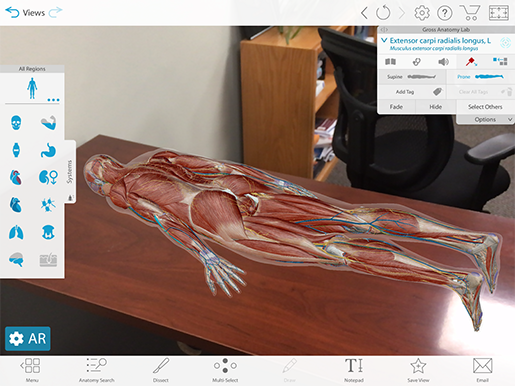

Use the 3D Draw tool to illustrate directional terms and planes of section

When you were in school, did you always secretly want to draw in your textbooks? Did you take notes in multiple colors, or get yelled at for doodling in your notebook? Well, the 3D draw feature in VB Suite is a dream come true for students who yearn to take a digital paintbrush to their class materials.

In these two mini-activities, students will use the 3D draw tool to create notecards illustrating directional term pairs and planes of section.

1. Directional Terms

Have students go through each of the following pairs of directional terms:

- Superior/inferior

- Dorsal/ventral

- Lateral/medial

- Distal/proximal

- Superficial/deep

For each pair, students will select a view to illustrate the contrast. I’ll use distal/proximal as an example.

First, select a view: in this case, the Axilla view from the Regional views will do nicely. Then, zoom and position the model and select the Draw tool from the menu at the bottom of the screen.

Here’s how I illustrated the distal/proximal distinction. After adjusting the depth of the drawing, I added a double-headed arrow stretching from the hand to the shoulder. You can move the model and add more drawings as you go—I added “distal” near the hand and “proximal” near the shoulder to complete my notecard.

Students can save their notecards using the Save Note button at the bottom of the screen. Then, they can compare the views and illustration method(s) they chose with those of a partner or members of a small group.

Note: students can feel free to get creative with the views they choose. Regions, systems, GAL, cross-sections—anything goes as long as it clearly demonstrates a contrast appropriately!

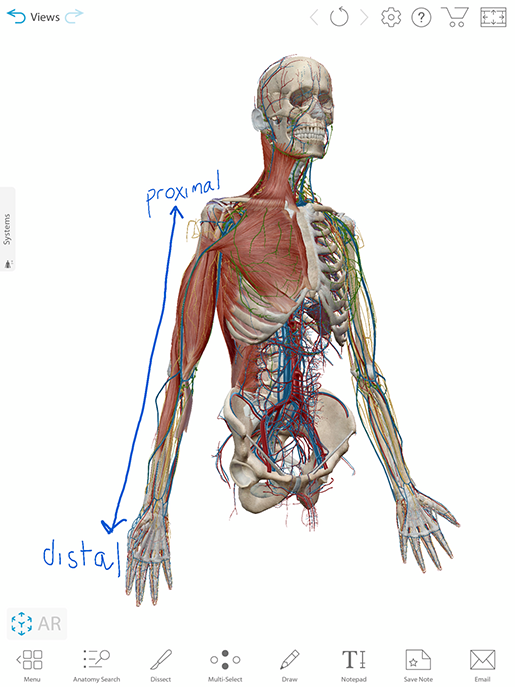

2. Planes of section

For this activity, have students open up the skull model in VB Suite. Then, they can either work alone or as a group to illustrate the following anatomical planes using the skull:

- Frontal (coronal)

You can walk them through your preferred method of illustration using the frontal/coronal plane. Personally, I’ve found that the easiest way to do this is by using squares in the Draw tool, so feel free to use these instructions.

Make sure the skull is facing front and isn’t tilted up, down, or to either side. Also make sure there’s a little bit of space around the outside of the skull. Select the Draw tool and adjust the depth of the drawing by moving the blue area over part of the model.

Then, start your drawing. Choose the rectangle tool in the Draw box at the top right of the screen. Click/tap and drag to create a rectangle that surrounds the skull, like so:

Rotate the model to check out your coronal section!

Have students rotate the model and add similar drawings to illustrate transverse and sagittal sections.

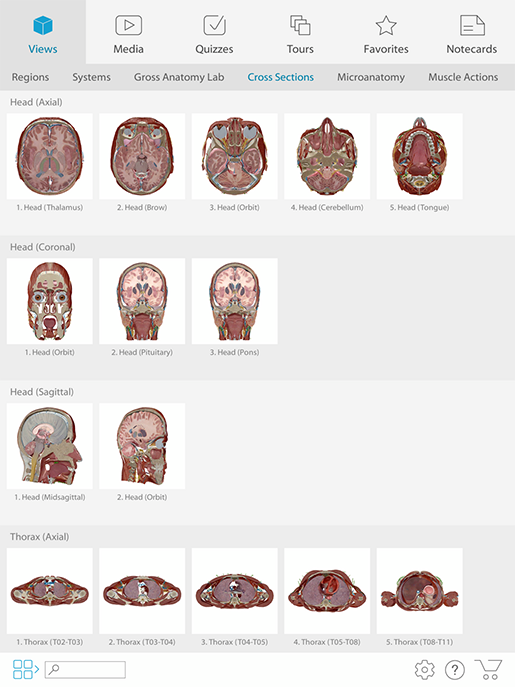

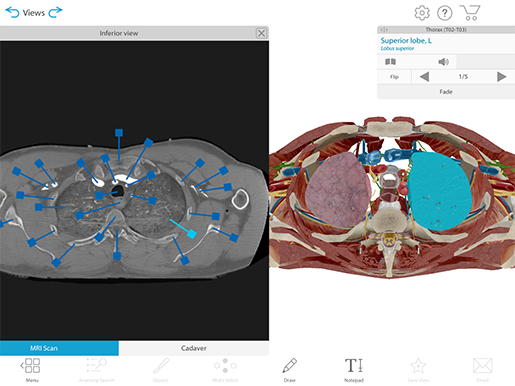

Use cross-section views to explore slices across different planes

To look at what different slices (coronal, sagittal, and axial) look like as 3D models, MRI or CT scan images, and photos of real cadavers, have students explore the Cross Sections series of views in VB Suite.

Encourage them to tap or click around to see which parts of which organs are visible in the different cross sections. The MRI, CT, and cadaver images also have labels students can click on to identify various structures.

Once students have had time to familiarize themselves with the 3D models and medical images of the slices, you can test their knowledge using pickles. Yes, pickles! You can also use cucumbers, zucchinis, summer squash, or any other oblong fruit or vegetable.

The following activity is adapted from the open source A&P I lab manual from the University of Georgia.

Each student will need:

- A pickle on a plate

- 4 toothpicks

Students should poke the toothpicks into the pickle to represent the arms and legs (they will serve as markers to differentiate the sagittal and coronal slices). Then, have students count off to divide the class into at least 3 groups. If you want to incorporate parasagittal and oblique slices into your lesson, you can add two additional groups.

Each group will be assigned to slice their pickle along a different plane:

- Group 1 → Sagittal (Midsagittal/Median)

- Group 2 → Coronal (Frontal)

- Group 3 → Axial (Transverse/Horizontal)

- Group 4 (optional) → Parasagittal

- Group 5 (optional) → Oblique

Once students have sliced their pickles, they should compare their slice with others in their group and contrast it with others outside their group. Students should take photos or draw representations of one of each type of slice.

We hope you and your students enjoy these activities! For more fun with planes and positions, check out these other VB blog posts:

- Anatomy and Physiology: Anatomical Planes and Cavities

- Anatomy and Physiology: Anatomical Position and Directional Terms

If you want to learn more about using 3D anatomy technology in your classroom, visit our instructors page and our education resources page.

But wait, there’s more! You can also download our free Planes & Positions eBook for a quick reference tool you can share with your students:

Be sure to subscribe to the Visible Body Blog for more anatomy awesomeness!

Are you an instructor? We have award-winning 3D products and resources for your anatomy and physiology course! Learn more here

- Anatomy & Physiology ,

- Technology in Anatomy Education ,

- Lesson Plans ,

Get free instructor access to Courseware

Subscribe to the visible body blog, most popular.

For students

For instructors

Get our awesome anatomy emails!

When you select "Subscribe" you will start receiving our email newsletter. Use the links at the bottom of any email to manage the type of emails you receive or to unsubscribe. See our privacy policy for additional details.

- Teaching Anatomy in 3D

- Teaching Biology in 3D

- Webcasts & Demos

- For K-12 Instructors

- K-12 Funding Guide

- Premade Courses

- Anatomy Learn Site

- Biology Learn Site

- Visible Body Blog

- eBooks and Lab Activities

- Premade Tours

- Premade Flashcard Decks

- Customer Stories

- Company News

- Support Site

- Courseware FAQ

- Submit a Ticket

©2024 Visible Body. All Rights Reserved.

- User Agreement

- Permissions

1.4 Anatomical Terminology

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Use appropriate anatomical terminology to identify key body structures, body regions, and directions in the body

- Demonstrate the anatomical position

- Describe the human body using directional and regional terms

- Identify three planes most commonly used in the study of anatomy

- Distinguish between major body cavities

Anatomists and health care providers use terminology that can be bewildering to the uninitiated; however, the purpose of this language is not to confuse, but rather to increase precision and reduce medical errors. For example, is a scar “above the wrist” located on the forearm two or three inches away from the hand? Or is it at the base of the hand? Is it on the palm-side or back-side? By using precise anatomical terminology, we eliminate ambiguity. For example, you might say a scar “on the anterior antebrachium 3 inches proximal to the carpus”. Anatomical terms are derived from ancient Greek and Latin words. Because these languages are no longer used in everyday conversation, the meaning of their words do not change.

Anatomical terms are made up of roots, prefixes, and suffixes. The root of a term often refers to an organ, tissue, or condition, whereas the prefix or suffix often describes the root. For example, in the disorder hypertension, the prefix “hyper-” means “high” or “over,” and the root word “tension” refers to pressure, so the word “hypertension” refers to abnormally high blood pressure.

Anatomical Position

To further increase precision, anatomists standardize the way in which they view the body. Just as maps are normally oriented with north at the top, the standard body “map,” or anatomical position , is that of the body standing upright, with the feet at shoulder width and parallel, toes forward. The upper limbs are held out to each side, and the palms of the hands face forward as illustrated in Figure 1.4.1 . Using this standard position reduces confusion. It does not matter how the body being described is oriented, the terms are used as if it is in anatomical position. For example, a scar in the “anterior (front) carpal (wrist) region” would be present on the palm side of the wrist. The term “anterior” would be used even if the hand were palm down on a table.

A body that is lying down is described as either prone or supine. Prone describes a face-down orientation, and supine describes a face up orientation. These terms are sometimes used in describing the position of the body during specific physical examinations or surgical procedures.

Regional Terms

The human body’s numerous regions have specific terms to help increase precision (see Figure 1.4.1 ). Notice that the term “brachium” or “arm” is reserved for the “upper arm” and “antebrachium” or “forearm” is used rather than “lower arm.” Similarly, “femur” or “thigh” is correct, and “leg” or “crus” is reserved for the portion of the lower limb between the knee and the ankle. You will be able to describe the body’s regions using the terms from the figure.

Directional Terms

Certain directional anatomical terms appear throughout this and any other anatomy textbook ( Figure 1.4.2 ). These terms are essential for describing the relative locations of different body structures. For instance, an anatomist might describe one band of tissue as “inferior to” another or a physician might describe a tumor as “superficial to” a deeper body structure. Commit these terms to memory to avoid confusion when you are studying or describing the locations of particular body parts.

- Anterior (or ventral ) describes the front or direction toward the front of the body. The toes are anterior to the foot.

- Posterior (or dorsal ) describes the back or direction toward the back of the body. The popliteus is posterior to the patella.

- Superior (or cranial ) describes a position above or higher than another part of the body proper. The orbits are superior to the oris.

- Inferior (or caudal ) describes a position below or lower than another part of the body proper; near or toward the tail (in humans, the coccyx, or lowest part of the spinal column). The pelvis is inferior to the abdomen.

- Lateral describes the side or direction toward the side of the body. The thumb (pollex) is lateral to the digits.

- Medial describes the middle or direction toward the middle of the body. The hallux is the medial toe.

- Proximal describes a position in a limb that is nearer to the point of attachment or the trunk of the body. The brachium is proximal to the antebrachium.

- Distal describes a position in a limb that is farther from the point of attachment or the trunk of the body. The crus is distal to the femur.

- Superficial describes a position closer to the surface of the body. The skin is superficial to the bones.

- Deep describes a position farther from the surface of the body. The brain is deep to the skull.

Body Planes

A section is a two-dimensional surface of a three-dimensional structure that has been cut. Modern medical imaging devices enable clinicians to obtain “virtual sections” of living bodies. We call these scans. Body sections and scans can be correctly interpreted, only if the viewer understands the plane along which the section was made. A plane is an imaginary, two-dimensional surface that passes through the body. There are three planes commonly referred to in anatomy and medicine, as illustrated in Figure 1.4.3 .

- The sagittal plane divides the body or an organ vertically into right and left sides. If this vertical plane runs directly down the middle of the body, it is called the midsagittal or median plane. If it divides the body into unequal right and left sides, it is called a parasagittal plane or less commonly a longitudinal section.

- The frontal plane divides the body or an organ into an anterior (front) portion and a posterior (rear) portion. The frontal plane is often referred to as a coronal plane. (“Corona” is Latin for “crown.”)

- The transverse (or horizontal) plane divides the body or organ horizontally into upper and lower portions. Transverse planes produce images referred to as cross sections.

Body Cavities

The body maintains its internal organization by means of membranes, sheaths, and other structures that separate compartments. The main cavities of the body include the cranial, thoracic and abdominopelvic (also known as the peritoneal) cavities. The cranial bones create the cranial cavity where the brain sits. The thoracic cavity is enclosed by the rib cage and contains the lungs and the heart, which is located in the mediastinum. The diaphragm forms the floor of the thoracic cavity and separates it from the more inferior abdominopelvic/peritoneal cavity. The abdominopelvic/peritoneal cavity is the largest cavity in the body. Although no membrane physically divides the abdominopelvic cavity, it can be useful to distinguish between the abdominal cavity, (the division that houses the digestive organs), and the pelvic cavity, (the division that houses the organs of reproduction).

Abdominal Regions and Quadrants

To promote clear communication, for instance, about the location of a patient’s abdominal pain or a suspicious mass, health care providers typically divide up the cavity into either nine regions or four quadrants ( Figure 1.4.4 ).

The more detailed regional approach subdivides the cavity with one horizontal line immediately inferior to the ribs and one immediately superior to the pelvis, and two vertical lines drawn as if dropped from the midpoint of each clavicle (collarbone). There are nine resulting regions. The simpler quadrants approach, which is more commonly used in medicine, subdivides the cavity with one horizontal and one vertical line that intersect at the patient’s umbilicus (navel).

Chapter Review

Ancient Greek and Latin words are used to build anatomical terms. A standard reference position for mapping the body’s structures is the normal anatomical position. Regions of the body are identified using terms such as “occipital” that are more precise than common words and phrases such as “the back of the head.” Directional terms such as anterior and posterior are essential for accurately describing the relative locations of body structures. Images of the body’s interior commonly align along one of three planes: the sagittal, frontal, or transverse.

Review Questions

Critical thinking questions.

In which direction would an MRI scanner move to produce sequential images of the body in the frontal plane, and in which direction would an MRI scanner move to produce sequential images of the body in the sagittal plane?

If the body were supine or prone, the MRI scanner would move from top to bottom to produce frontal sections, which would divide the body into anterior and posterior portions, as in “cutting” a deck of cards. Again, if the body were supine or prone, to produce sagittal sections, the scanner would move from left to right or from right to left to divide the body lengthwise into left and right portions.

This work, Anatomy & Physiology, is adapted from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax , licensed under CC BY . This edition, with revised content and artwork, is licensed under CC BY-SA except where otherwise noted.

Images, from Anatomy & Physiology by OpenStax , are licensed under CC BY except where otherwise noted.

Access the original for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction .

Anatomy & Physiology Copyright © 2019 by Lindsay M. Biga, Staci Bronson, Sierra Dawson, Amy Harwell, Robin Hopkins, Joel Kaufmann, Mike LeMaster, Philip Matern, Katie Morrison-Graham, Kristen Oja, Devon Quick, Jon Runyeon, OSU OERU, and OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.10: Laboratory Activities and Assignment

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 53515

- Rosanna Hartline

- West Hills College Lemoore

Laboratory Activities and Assignment

Part 1: human organ systems.

The 11 human organ systems are listed below with an abbreviation for each. Put the letters relating to each body system to indicate the organ system each organ or structure listed below belongs to. There are more than one answer in some cases.

Part 2: Anatomical Position and Directional Terms

1. Fill in the blank with the appropriate directional term to complete the following sentences. More than one answer may be correct.

a. The heart is ___________ to the lungs.

b. The knee is ___________ to the hip.

c. The wrist is ___________ to the hand.

d. The mouth is ___________ to the nose.

e. The thorax is ___________ to the abdomen.

f. The thumb is ___________ to the ring finger.

g. The sternum is ___________ to the heart.

h. The skull is ___________ to the scalp.

i. The ears are ___________ to the nose.

j. Dorsal refers to the ___________ of the human body, while ventral refers to the ___________ of the human body.

2. Use the information below to put "incus" in the correct white box on the figure below to label incus, a part of the human auditory system:

a. incus is superior to and lateral to the cochlear nerve

b. incus is medial to malleus

c. incus is lateral to stapes

Part 3: Planes and Sections

1. Name the type of section performed in the brain shown. Write your answers on the lines given.

_____________________ ___________________ ___________________

2. Use your knowledge of the different body planes/sections, fill in the blanks with the appropriate body plane for each of the following descriptions.

a. The plane that divides the body into anterior and posterior parts is the ___________ plane.

b. A transverse plane divides the body into ___________ and ___________ regions.

c. A ___________ or ___________ plane divides the body into right and left parts.

3. Label the two images below with the appropriate anatomical planes and directional terms:

Part 4: Anatomical Adjectives for Body Locations

1. Label the anatomical model of the muscle person below with the anatomical adjectives for body locations in the listed. Label BOTH the anterior view and the posterior view with as many of the labels as possible for each view.

Part 5: Abdominopelvic Regions and Abdominopelvic Quadrants

1. Label the four abdominopelvic quadrants and the nine abdominopelvic regions on the anatomical models below as appropriate.

Part 6: Body Cavities and Serosa

1. Fill in the blank with the appropriate body cavity:

a. The two main body cavities are the ___________ and the ___________ cavities.

b. The stomach is found in the ___________ cavity.

c. The heart is found in the ___________ cavity, which is part of the larger ___________ cavity.

d. The brain is found within the ___________ cavity which is part of the larger ___________ cavity

e. The urinary bladder and reproductive organs are found within the ___________ cavity.

2. Fill in each box in the figure below with either the cavity shown (white boxes) or the name of the serous membrane (gray boxes).

Attributions

Part 2: anatomical position & directional terms.

- "Anatomy of the Human Ear" by Lars Chittka; Axel Brockmann , Wikipedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

- "BIOL 250 Human Anatomy Lab Manual SU 19" by Yancy Aquino , Skyline College is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Part 3: Planes & Sections

- "Anatomy 204L: Laboratory Manual (Second Edition)" by Ethan Snow , University of North Dakota is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

- "Anatomy and Physiology I Lab" by Victoria Vidal is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Part 5: Abdominopelvic Regions & Abdominopelvic Quadrants

- Anatomy and Physiology I Lab" by Victoria Vidal is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Part 6: Body Cavities & Serosa

- "Anatomy and Physiology Lab Homework" by Laird C Sheldahl is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Human Bio Media

Anatomical Position

(sample lesson), description.

Anatomists use a standardized body pose called the anatomical position to assign directional terms (e.g. front, back, sides) to the body regions.

A body in the anatomical position ……

- is erect with the arms placed to the sides,

- the legs and feet are at shoulder width and parallel,

- and the face, palms, and feet are directed forward.

Terms of Use

The assigned directional terms still apply even if the body regions change position. For example, the palmer surface of the hand is still considered to be anterior even if the wrist is turned over and the palmar surface faces backward. Without this standardized approach, assigning directional terms to the body’s moveable parts would become much more confusing.

Page Attributions

OpenStax College , Anatomy and Physiology

Access for free at – https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction

Reference: “ Overview of Anatomy and Physiology “

Wikipedia , the free encyclopedia

Reference: “ Standard Anatomical Position “

2024 Kentucky Derby post positions set: Here's where each horse landed

The 2024 Kentucky Derby is quickly approaching.

Post positions were drawn Saturday ahead of the 150th running of the annual horse race, which is set to take place on May 4 at the legendary Churchill Downs in Louisville. The draw that determines the starting gate for each horse traditionally takes place Monday before the race, but the draw was held a full week ahead this year.

Post 5 and Post 10 have produced more winners since the Kentucky Derby began using a starting gate in 1940, according to the Louisville Courier Journal , part of the USA TODAY Network. But post position doesn't solely determine success – Mage won the 2023 Kentucky Derby with a time of 2:01 with veteran jockey Javier Castellano and trainer Gustavo Delgado from Post 8, one of the least favorable positions.

From NFL plays to college sports scores, all the top sports news you need to know every day.

2024 KENTUCKY DERBY: Date, time and how to watch

The Kentucky Derby officially kicks off the first leg of the Triple Crown, followed by the Preakness Stakes on May 18 and Belmont Stakes in early June.

Here's the post positions for the 2024 Kentucky Derby:

2024 Kentucky Derby post positions

The starting post position for each horse is determined by a draw, where one official pulls a horse's name out of a pile, while another official draws a gate number out of a separate pile.

Here's where each horse landed, in addition to the horse's trainer, jockey and odds:

1. Dornoch , Danny Gargan, Luis Saez, 20-1

2. Sierra Leone , Chad Brown, Tyler Gaffalione, 3-1

3. Mystik Dan , Kenny McPeek, Brian Hernandez Jr., 20-1

4. Catching Freedom , Brad Cox, Flavien Prat, 8-1

5. Catalytic , Saffie Joseph Jr., Jose Ortiz, 30-1

6. Just Steel , D. Wayne Lukas, Keith Asmussen, 20-1

7. Honor Marie , Whit Beckman, Ben Curtis, 20-1