Shadow Health Assessment Help | Outline, Sample & Examples

- Carla Johnson

- August 18, 2023

- Writing Guides for MSN students

Shadow Health Assessment is a tool that nurses can use to gather information about a patient’s health. If you are stuck with your Shadow Health Assessment, we can help. Here is an Outline of a Shadow Health Assessment , Shadow Health Promotion Outline, a sample of Tina’s Individualized Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Plan of Care Paper, and 30 Shadow Health Assessment examples.

Outline of a Shadow Health Assessment

· | Transcript

· | Subjective Data Collection

· | Objective Data Collection

· | Education & Empathy

· | Documentation

· Document: Provider Notes

· Document: Vitals

· | Self-Reflection

Shadow Health Promotion Outline

The plan for addressing the health promotion and disease prevention needs for your patient should include:

Demographics:

– Age, gender and race of patient

– Education level (health literacy)

– Access to health care

Insurance/Financial status

– Is the patient able to afford medications and health diet, and other out-of-pocket expenses?

Screening/Risk Assessment

– Identified health concerns based on screening assessments and demographic information

Nutrition/Activity

– What is the patients activity level, is the environment where the patient lives safe for activity

– Nutrition recommendations based on age, race gender and pre-existing medical conditions

– Activity recommendations

Social Support

– Support systems, family members , community resources

Health Maintenance

– Recommended health screening based on age, race, gender and pre-existing medical conditions

Patient Education:

– Identified knowledge deficit areas/patient education needs (medication teaching etc).

– Self-care needs/ Activities of daily living

Tina’s Individualized Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Plan of Care Paper

Introduction

Care plans communicate and organize individualized actions for a patient enabling continuity of care. It is imperative to formulate an individualized plan of nursing care that concentrates on Tina’s personalized health promotion and disease prevention needs . To achieve the goal, the plan factors in details from Tina’s health history, genogram, and assessment to formulate a nursing care plan .

Tina’s Individualized Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Plan of Care

Demographics

The patient is a 28-year-old of African – American woman who is not married and presents for a pre-employment physical examination. Her new employer is desirous of having a recent physical exam for the health insurance

Education level (health literacy)

Tina Jones’s health maintenance practices are up to date with recent tests for HIV/AIDS test; plan to use a condom in sexual encounters, regular Pap smear, eye, and dental exam being up-to-date. Other measures include having smoke detectors at home, strap the seatbelt while driving, and use sunscreens. However, her health maintenance approaches should consist of more self-care activities meat to manage her existing chronic diseases; namely, asthma, which was diagnosed in childhood, Type 2 diabetes (T2DM) diagnosed at 24 years as well as hypertension . While at the moment the patient has no issues with using medication therapy and non-pharmacological interventions like exercises and diet, there is a need for her to keep herself updated on the emerging treatment and management options (ADA, 2019).

Access to health care

With advancing age, she should also consider other types of cancer tests like a mammogram for breast cancer. The patient needs to maintain her regular medical checkup visits and always keep her physician updated on any emerging health issues , especially concerning drug interactions, considering the cocktail of medications she has to take daily.

Using individualized nursing care planning entails outlining strategies to engage the patient, and conduct current health assessments and health risk assessments. Both patient and provider goals are SMART–based so that there are effective care coordination and tracking. The patient’s health insurance status is up to date since she is informal employment. Medicare Part B, which deals with Medical insurance and Medicare Part D (covering prescription drug coverage), means the patient can afford the anti-diabetic drugs. Tina Jones is also in steady employment and, therefore, can provide any medication while meeting all the other out-of-pocket expenses like coinsurance and copayment expenses required to make the personalized nursing care plan a success (Dall et al., 2016).

Tina’s diagnosis of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) means she is likely to have difficulties should she decide to have a child of her own. As such, the care plan involves strategies that will optimize her preconception period health . At the same time, a multi-faceted approach includes but not limited to lifestyle modification and pharmacological treatment (Holton, Hammarberg & Johnson, 2018). Furthermore, the patient is advised to keep away from allergens like dust and pets to avoid asthma exacerbations.

Dietary planning and regular exercises are also to continue to manage her T2DM and hypertension as well.The T2DM friendly meals entail packing in more vegetables and fruits while also eating something every morning.The meal plan also includes fiber, and considering Patient Tina Jones is a small woman; the target is to have 1200 to 1600 calories daily. Asif (2014) also recommends that T2DM patients with comorbidities should also stay active. The care plan recommends having 30 minutes of physical activities a minimum of five days every week.

According to Rakinson, Pillay & Sibanda (2017), individuals like Tina jones living with dT2DM, hypertension, and asthma since all three impose a lifelong psychological burden on both the patient and their significant others who in this case happens to be her male partner. Current studies indicate that social support plays a vital role in the effective management of these conditions. Therefore, the ongoing care plan advises Tina to join a social support group and also include the male partner in the current care plan. Tina should also use diabetes supplies availed through Part D of her medical cover.

Here is an Outline of a Shadow Health Assessment, Shadow Health Promotion Outline, a sample of Tina’s Individualized Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Plan of Care Paper, and 30 Shadow Health Assessment examples.

Considering that the patient is a young adult woman diagnosed with PCOS, regular screenings for some types of cancer like breast, liver, pancreas, and endometrium, among others, is recommended for this patient. ADA (2019) notes that diabetes is closely linked to increased risk of some types of .cancers.

Patient Education

The last component is the development of a diabetes self- management patient education . Chrivala, Sherr & Lipman (2016) note that more than half of diabetic patients do not meet and sustain the recommended target of less than 7% for glycated hemoglobin. At the same, only about 14% achieve the goal of non-smoking, low-density lipoprotein, and blood pressure. Therefore this care plan has a DSME intervention component meant to address this anomaly. Other studies have also determined that hypertension and T2DM can themselves be a risk factor for developing asthma (Lee & Lee, 2019). However, this is not the case with Patient Tina since has asthma was diagnosed at the age of two and a half years. Patient education addresses critical elements of diabetes like types, medication, risk factors, complications if poorly managed, and both pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies. Emphasis is placed on the role of diet and physical exercises as well as adhering to the prescribed medications.

In conclusion, this essay has established the need to shift from the traditional medical evaluation of T2DM and comorbidities, which involved a chief complaint, history of illness, past medical history, and both family and social history. Also included in the traditional evaluation are diagnostic tests followed by assessment before a care plan can be developed. The current evidence-based care plan entails patient engagement, ongoing health assessment , a health risk assessment, then patient goals, and provider goals. The individualized plan then outlines a therapeutic strategy, coordination of care , and finally, tracking.

American Diabetes Association. (2019). 4. Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: standards of medical care in diabetes—2019. Diabetes care , 42 (Supplement 1), S34-S45.

American Diabetes Association. (2019). Standards of medical care in diabetes—2019 abridged for primary care providers. Clinical Diabetes , 37 (1), 11-34.

Asif, M. (2014). The prevention and control of type-2 diabetes by changing lifestyle and dietary patterns. Journal of education and health promotion, 3.

Chrvala, C. A., Sherr, D., & Lipman, R. D. (2016). Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of the effect on glycemic control. Patient education and counseling , 99 (6), 926-943.

Dall, T. M., Yang, W., Halder, P., Franz, J., Byrne, E., Semilla, A. P., & Stuart, B. (2016). Type 2 diabetes detection and management among insured adults. Population health metrics, 14(1), 43.

Holton, S., Hammarberg, K., & Johnson, L. (2018). Fertility concerns and related information needs and preferences of women with PCOS. Human reproduction open , 2018 (4), hoy019.

Lee, K. H., & Lee, H. S. (2019). Hypertension and diabetes mellitus as risk factors for asthma in Korean adults: the Sixth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. International health .

Rakinson, S., Pillay, B. J., & Sibanda, W. (2017). Social support and coping in adults with type 2 diabetes. African journal of primary health care & family medicine, 9(1), 1-8 .

Serrano, V., Rodriguez‐Gutierrez, R., Hargraves, I., Gionfriddo, M. R., Tamhane, S., & Montori, V. M. (2016). Shared decision‐making in the care of individuals with diabetes. Diabetic Medicine , 33 (6), 742-751.

As you continue, premiumacademicaffiates.com has the top and most qualified writers to help with any of your assignments. All you need to do is place an order with us. (Health History and Interview)

Shadow Health Comprehensive Assessment Examples

Working on an assignment with similar concepts or instructions .

A Page will cost you $12, however, this varies with your deadline.

We have a team of expert nursing writers ready to help with your nursing assignments. They will save you time, and improve your grades.

Whatever your goals are, expect plagiarism-free works, on-time delivery, and 24/7 support from us.

Here is your 15% off to get started. Simply:

- Place your order ( Place Order )

- Click on Enter Promo Code after adding your instructions

- Insert your code – Get20

All the Best,

Have a subject expert Write for You

Have a subject expert finish your paper for you, edit my paper for me, have an expert write your dissertation's chapter, worried about your paper we can help, frequently asked questions.

When you pay us, you are paying for a near perfect paper and the time convenience.

Upon completion, we will send the paper to via email and in the format you prefer (word, pdf or ppt).

Yes, we have an unlimited revision policy. If you need a comma removed, we will do that for you in less than 6 hours.

As you Share your instructions with us, there’s a section that allows you to attach as any files.

Yes, through email and messages, we will keep you updated on the progress of your paper.

Start by filling this short order form thestudycorp.com/order

And then follow the progressive flow.

Having an issue, chat with us here

Dr. James Logan – Admin msnstudy.com

Popular Posts

- Academic Writing Guides

- Nursing Care Plan

- Nursing Theory

- Nursing Topics and Ideas

Important Links

Knowledge base, utilize our guides & services for flawless nursing papers: custom samples available.

MSNSTUDY.com helps students cope with college assignments and write papers on various topics. We deal with academic writing, creative writing, and non-word assignments.

All the materials from our website should be used with proper references. All the work should be used per the appropriate policies and applicable laws.

Our samples and other types of content are meant for research and reference purposes only. We are strongly against plagiarism and academic dishonesty.

We Accept:

📕 Studying HQ

30 shadow health comprehensive assessment examples | help, bob cardens.

- August 25, 2022

- How to Guides , Nursing

Shadow Health Comprehensive Assessment (SHCA) helps in evaluating and identifying the needs of patients. If you are looking for a competent nursing writer to take your shadow health assessments for you, look no further because we can help. Check out the Shadow Health Comprehensive Assessment Examples for guidance.

What You'll Learn

Outline of a shadow health history assignment

- Subjective Data Collection

- Objective Data Collection

- Education & Empathy

- Documentation / Electronic Health Record

- Information Processing

- Lab Pass: Certificate of Completion

Subjective Data Collection:

- Chief Complaint

- History of Present Illness

- Medical History

- Social History

- Review of Systems

Current Shadow Health Comprehensive Assessment Examples

30 shadow health comprehensive assessment examples.

Shadow Health Comprehensive Assessment (SHCA) helps in evaluating and identifying the needs of patients . If you are looking for a competent nursing writer to take your shadow health assessments for you, look no further, because we can help. Check out the Shadow Health Comprehensive Assessment Examples for guidance.

Start by filling this short order form order.studyinghq.com

And then follow the progressive flow.

Having an issue, chat with us here

Cathy, CS.

New Concept ? Let a subject expert write your paper for You

Have a subject expert write for you now, have a subject expert finish your paper for you, edit my paper for me, have an expert write your dissertation's chapter, popular topics.

Business Analysis Examples Essay Topics and Ideas How to Guides Nursing

- Nursing Solutions

- Study Guides

- Free College Essay Examples

- Privacy Policy

- Writing Service

- Discounts / Offers

Study Hub:

- Studying Blog

- Topic Ideas

- How to Guides

- Business Studying

- Nursing Studying

- Literature and English Studying

Writing Tools

- Citation Generator

- Topic Generator

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Conclusion Maker

- Research Title Generator

- Thesis Statement Generator

- Summarizing Tool

- Terms and Conditions

- Confidentiality Policy

- Cookies Policy

- Refund and Revision Policy

Our samples and other types of content are meant for research and reference purposes only. We are strongly against plagiarism and academic dishonesty.

Contact Us:

📞 +15512677917

2012-2024 © studyinghq.com. All rights reserved

Official website of the State of California

2023-104 The California Labor Commissioner’s Office

Inadequate Staffing and Poor Oversight Have Weakened Protections for Workers

Published: May 29, 2024 | Report Number: 2023-104

May 29, 2024 2023‑104

The Governor of California President pro Tempore of the Senate Speaker of the Assembly State Capitol Sacramento, California 95814

Dear Governor and Legislative Leaders:

As directed by the Joint Legislative Audit Committee, my office conducted an audit of the Department of Industrial Relations’ Division of Labor Standards Enforcement, also known as the Labor Commissioner’s Office (LCO), and its role in processing wage theft claims. We reviewed the backlog of wage claims submitted by workers from fiscal years 2017–18 through 2022–23, and determined that the LCO is not providing timely adjudication of wage claims for workers primarily because of insufficient staffing to process those claims.

According to the LCO’s data, it had 47,000 backlogged claims at the end of fiscal year 2022–23. Its Wage Claims Adjudications Unit (Adjudications Unit) lacks a sufficient number of staff throughout its field offices and thus can neither process new wage claims in a timely manner nor efficiently reduce the extensive backlog of wage claims. Further, the LCO lacks complete and accurate data to enable it to provide proper oversight and ensure compliance with statutory requirements. We analyzed the LCO’s staffing and available workload data, and estimated that it needs hundreds of additional positions under its existing process to resolve the backlog. The lack of adequate staffing is exacerbated by the fact that the LCO currently has a high vacancy rate, and an inefficient and lengthy recruitment process.

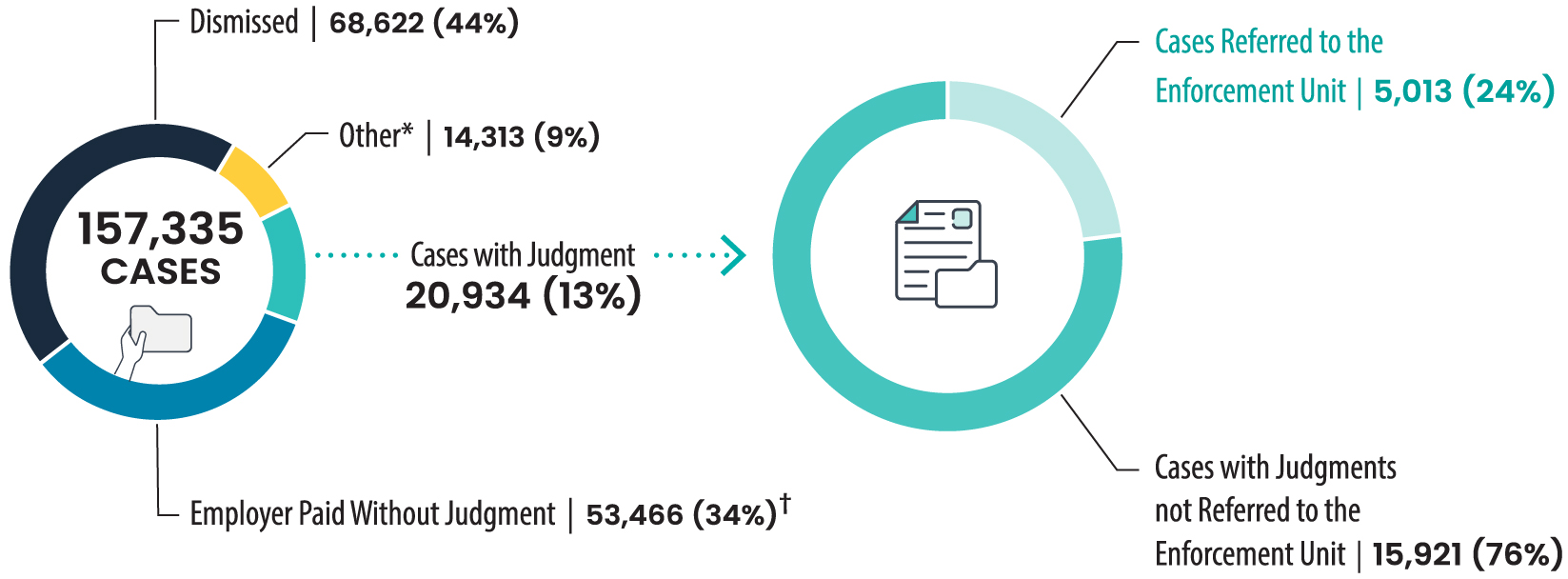

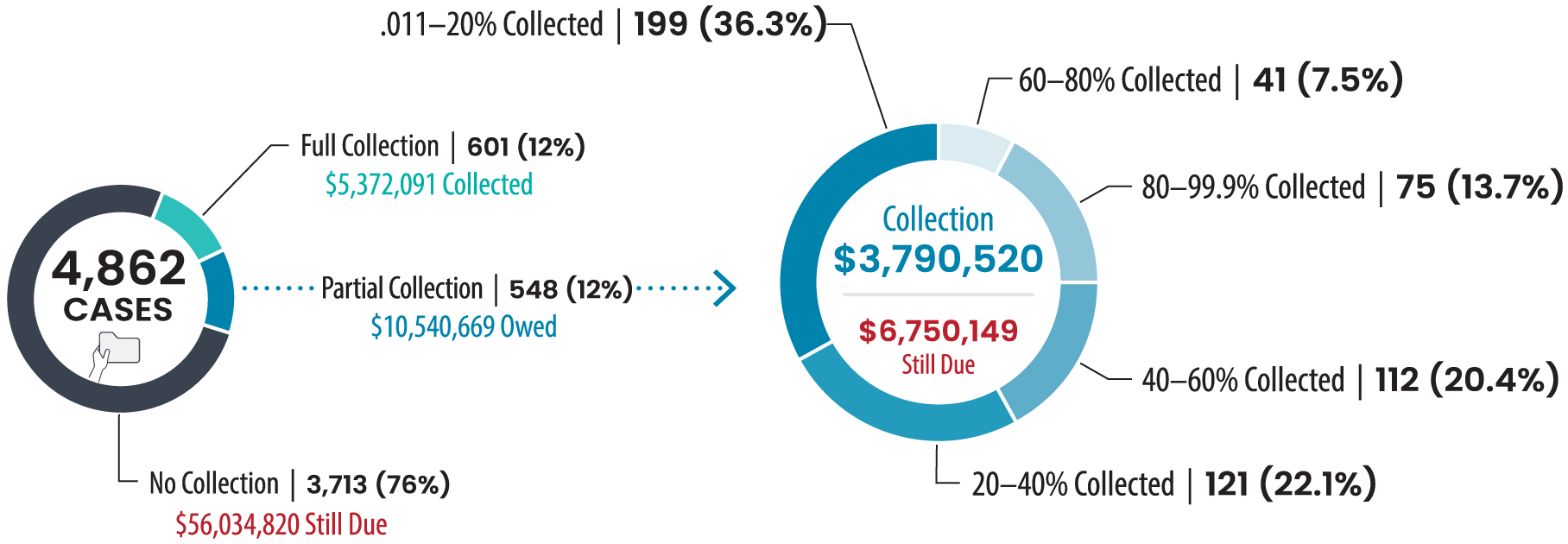

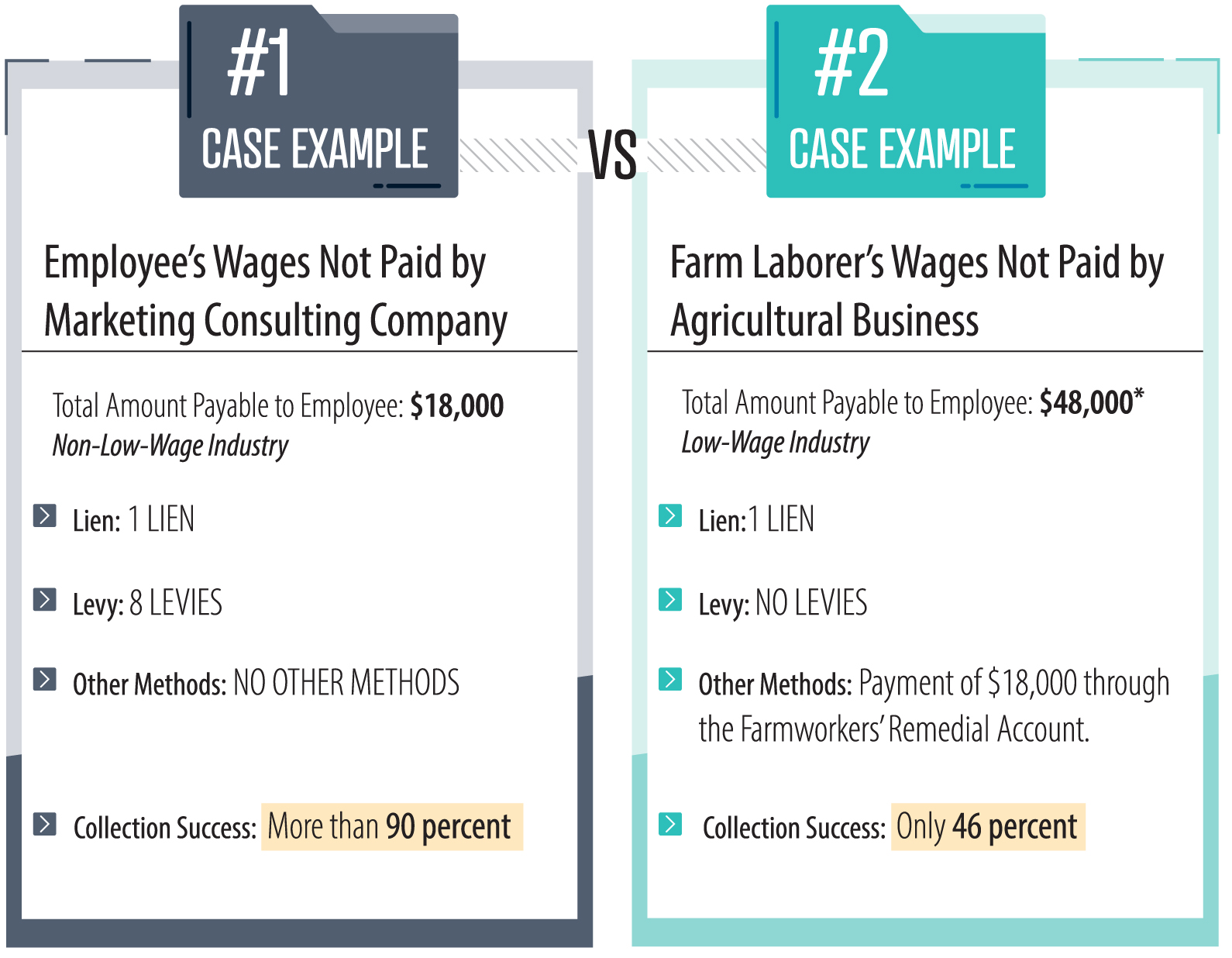

In addition to its delays in processing wage claims, the LCO has not been successful in collecting judgments from employers. For those workers who choose to have the LCO’s Judgment Enforcement Unit (Enforcement Unit) attempt to collect payment, the Enforcement Unit was successful in collecting the entire amount owed in only 12 percent of cases from 2018 through November 2023. A possible factor contributing to its low collection rate is that the Enforcement Unit does not consistently use all of the methods available to it for collecting payments owed to workers.

Respectfully submitted,

GRANT PARKS California State Auditor

Selected Abbreviations Used in This Report

When an employer does not pay wages due to an employee, that failure to pay is called wage theft . State law provides workers with a recourse for recovering these unpaid wages through the Division of Labor Standards Enforcement, also known as the Labor Commissioner’s Office (LCO), an agency within the Department of Industrial Relations (DIR). The LCO is responsible for investigating and resolving wage theft claims (wage claims). However, the LCO is not providing timely recourse to thousands of workers and has an extensive backlog of wage claims. The primary cause of the agency’s sometimes‑years‑long delays in resolving workers’ wage claims is the inadequate staffing at the agency itself.

The LCO Often Takes Two Years or Longer to Process Wage Claims

Although state law requires the LCO to issue a decision on a wage claim within a maximum of 135 days after it is filed, as of the end of fiscal year 2022–23, the agency had taken a median of 854 days to issue decisions—more than six times longer than the law allows. The backlog of claims had grown from 22,000 at the end of fiscal year 2017–18 to 47,000 at the end of fiscal year 2022–23. As of November 1, 2023, more than 2,800 claims had been open for five years or more; these claims equated to more than $63.9 million in unpaid wages.

Field Offices Have Insufficient Staffing to Process Wage Claims

As of June 2023, the majority of the LCO’s Wage Claim Adjudication Unit’s (Adjudication Unit) 17 field offices had staff vacancy rates equal to or greater than 10 percent, and 13 field offices had a vacancy rate of 30 percent or more.

We estimated that the LCO needs hundreds of additional positions under its existing processes to resolve its backlog. Contributing to the LCO’s high vacancy rate is an ineffective and lengthy hiring process and non‑competitive salaries for several LCO positions.

The LCO Has Not Always Provided Critical Training and Oversight to Its Field Offices

The LCO has not ensured that new staff receive formal training in wage claim processing. It has only had a dedicated training unit since April 2022. Field office supervisors have not always assigned claims to staff for processing in a timely manner and are sometimes unaware of existing tools for doing so.

The Enforcement Unit’s Work Results in Only a Small Percentage of Successful Payments to Workers

Between January 2018 and November 2023, about 28 percent of employers did not make LCO‑ordered payments. The LCO consequently obtained judgments against those employers. In roughly 24 percent of judgments during that time, or about 5,000 cases, the workers referred their judgments to the Enforcement Unit. The unit successfully collected the entire judgment amount in only 12 percent of those judgments, or in about 600 cases.

Agency Comments

DIR agreed with our recommendations, explained some actions it is already taking to implement them, and stated that it will provide updates at required intervals.

Introduction

Wage theft occurs when an employer does not pay owed wages or benefits to an employee. Wage theft is a problem across the United States, and when it occurs in California, a worker may file a wage theft claim (wage claim) with the Department of Industrial Relations’ (DIR) Division of Labor Standards Enforcement, also known as the Labor Commissioner’s Office (LCO). The LCO is responsible for ensuring appropriate pay in every workplace in the State and for promoting economic justice by enforcing the State’s labor laws.

The LCO’s process for resolving wage claims begins when a worker files a claim. That claim provides the LCO with the potentially liable employer’s name, the employer’s business type, the claimed wage theft amount, and the time frame during which the claimed wage theft occurred. If necessary information is missing from a filed claim, the worker may experience a delay in its processing. In December 2021, the LCO launched a web‑based claim filing system, which allows workers to file claims online. However, a worker may also file a claim by completing a form and submitting it at a local field office in person or by mailing or emailing the form to the LCO. In fiscal year 2022–23, the LCO received about 39,000 wage claims.

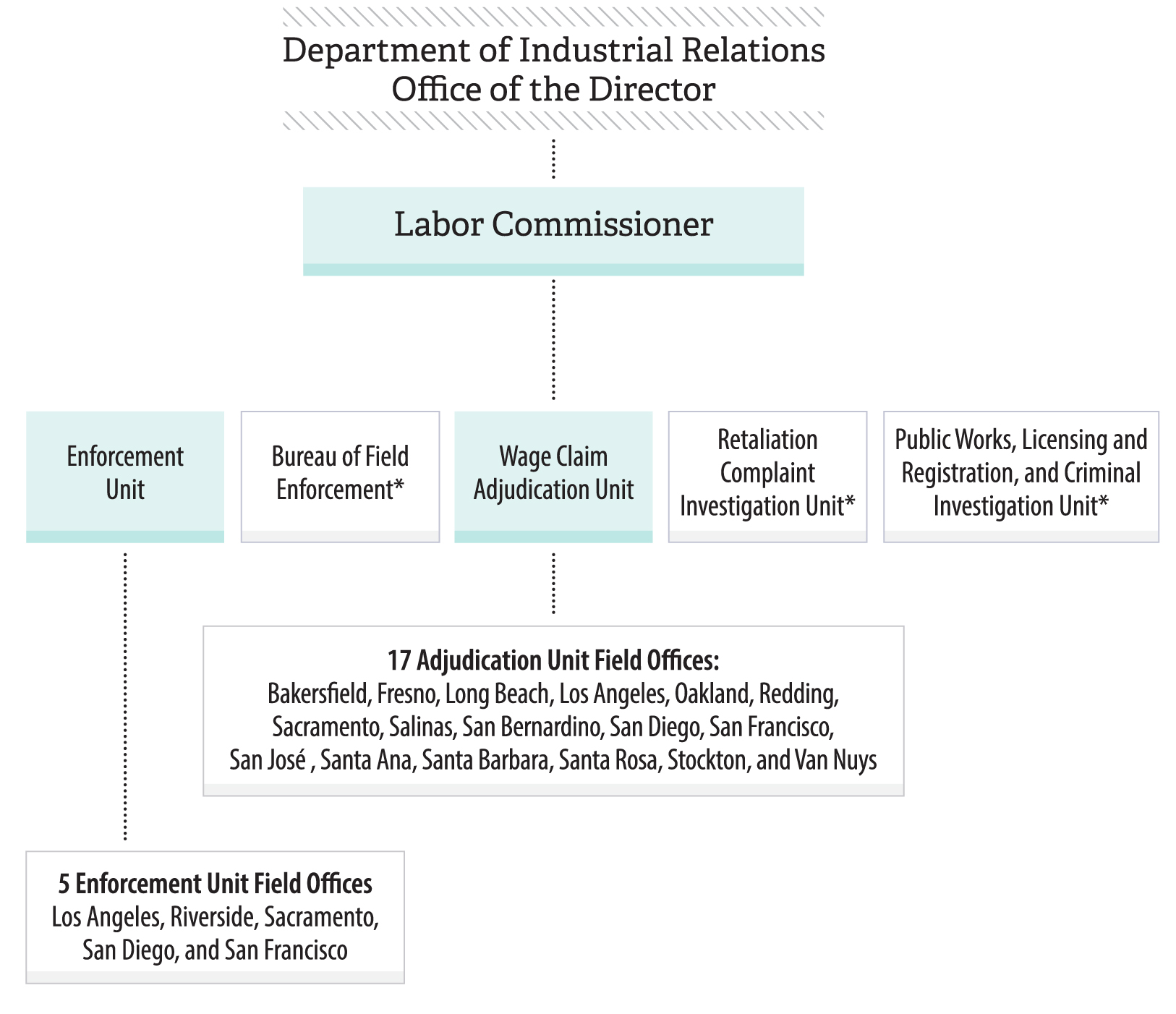

As Figure 1 shows, the LCO maintains several units that address wage theft. Its Wage Claims Adjudication Unit (Adjudication Unit) has 17 field offices throughout the State to receive and adjudicate wage claims. The work of the Judgment Enforcement Unit (Enforcement Unit) occurs after the adjudication process: the Enforcement Unit helps workers enforce judgments against employers to collect owed amounts. The Adjudication Unit had 286 authorized staff positions and a salaries and wages budget of $124 million in fiscal year 2023–24.

The LCO Operates as a Division Within DIR

Source: DIR organization charts.

* The Bureau of Field Enforcement; Retaliation Complaint Investigation Unit; Public Works, Licensing and Registration; and Criminal Investigation Unit do not handle the adjudication of wage claim cases and were therefore not subject to this audit.

Figure 1 is a color coded organization chart that illustrates the Industrial Relations authority over the Division of Labor Standards, which includes various units and field offices. The teal colored boxes show the division and its units that were directly involved in the audit. The following departments are coded as teal: Division of Labor Standards/ Labor Commissioner, Judgement Enforcement Unit (Enforcement Unit), and the Wage Claim Adjudication Unit (Adjudication Unit). The Enforcement Unit includes five field offices, and the Adjudication Unit includes seventeen field offices. Non-color coded departments include the following: Bureau of Field Enforcement, Retaliation Complaint Investigation Unit, and Public Works, Licensing and Registration, and Criminal Investigation Unit. These units were not included in the audit scope.

The Adjudication Unit Processes, Investigates, and Rules on Wage Claims

The text box shows key Adjudication Unit staff who work in field offices on claims processing. Because the deputy labor commissioner classification includes three levels, each with unique duties, we refer to these classifications by the duties they perform: the field office supervisor, hearing officer, and deputy. The field office supervisor manages the workload of the office and its staff. Once the field office supervisor assigns a claim to a deputy, the deputy investigates the claim. The hearing officer holds hearings for claims to determine whether a violation of labor law occurred, and the office technicians and industrial relations representatives review the claims and gather all information and supporting documentation. Regional managers oversee multiple field offices but generally do not supervise the daily processing of claims except in the most complex cases.

Adjudication Unit Key Positions That Work on Claims Processing

Deputy Labor Commissioner III (field office supervisor)

- Reviews and assigns claims

- Conducts training

- Performs all tasks performed by hearing officers and deputies.

Deputy Labor Commissioner II (hearing officer)

- Conducts hearings

- Writes orders, decisions, or awards

- Facilitates settlements

Deputy Labor Commissioner I (deputy)

- Investigates claims

- Schedules and conducts settlement conferences

Industrial Relations Representative

- Analyzes filed claims

Office Technician

- Enters data

- Writes and processes correspondence

Source: DIR job classification duty statements.

Once assigned a claim to investigate, the deputy gathers relevant facts to determine whether the LCO will take further action on the claim. The deputy may determine that no further action will be taken for certain reasons, such as the LCO’s not having jurisdiction. The field office supervisor must approve a deputy’s determination to take no further action. For all other claims, the deputy attempts to facilitate a resolution to the claim with the worker and employer. The deputy may discuss the claim with the employer to resolve the claim or hold a settlement conference with the worker and the employer to settle the claim.

If the deputy cannot facilitate the claim’s settlement with the worker and the employer, the deputy schedules a hearing with a hearing officer. As Figure 2 shows, state law requires the LCO to determine whether a hearing is required and notify the parties within 30 days of the claim’s filing. In certain cases, claims may go directly to civil litigation, skipping the settlement conference and hearing steps. For example, the LCO filed lawsuits in August 2020 against two ride‑sharing companies after the agency received thousands of complaints against the companies. These lawsuits were still ongoing as of March 2024.

Every Stage of the LCO’s Wage Claim Process Must Meet a Statutory Time Frame

Source: Analysis of state law and LCO’s wage claim processing procedures.

* The LCO can litigate a claim immediately instead of holding a settlement conference or a hearing.

† Parties have an extra five days from the date the notice was served if it was served by mail to an in‑state address and an extra 10 days from the date the notice was served if it was served to an out‑of‑state address.

Figure 2 is a flowchart describing each stage of the wage claim process, using statutory timeframes. The process to resolve a claim is expected to be completed within a maximum of 135 days. When a worker submits a claim, it is received by one of the Adjudication Units, pertinent information is gathered to complete the claim, and a settlement conference is scheduled. If the claim is not settled prior to, or at the settlement conference, the Adjudication Unit determines if a hearing is necessary, or if the claim will be dismissed. This should all occur within 30 days. Note: parties can settle at any time during the claim resolution process. If the claim is not dismissed nor settled at the conference, a hearing shall be held within 90 days. Within 15 days after a hearing is concluded, an order, decision, or award shall be filed. Upon receipt of the order, decision, or award, the parties can appeal within 10 days, or the order, decision, or award, is filed with the superior court, and a judgement is processed against the employer. If a judgement is issued, the worker can choose to refer the claim to the Enforcement Unit for help collecting the owed wages.

State law requires that the LCO hold a hearing within 90 days of determining that a hearing is required. The assigned hearing officer presides over the hearing and reviews all information presented. A hearing can last from a few hours to multiple days, depending on the complexity of the alleged violations under consideration, and state law requires that the LCO issue a decision within 15 days of the hearing’s conclusion. After a hearing, the hearing officer issues a decision on the claim—commonly known as the order, decision, or award . Although the average amount awarded on a claim between 2018 and November 2023 was about $1,900, the awards ranged from less than a dollar to more than $507,000.

The worker or the employer may file an appeal with the relevant county Superior Court within 10 days of the date the notice of the decision was served. Parties have an extra 5 days to appeal if the decision is served by mail to an in‑state address and an extra 10 days from the date of service if the decision is served to an out‑of‑state address. If the employer appeals the decision, the LCO may represent the worker at the worker’s request as the worker may be unable to afford hiring legal counsel in the appeal proceedings. However, if the worker appeals the decision, the LCO does not participate in the appeal. Cases before a county Superior Court judge are no longer under the jurisdiction of the LCO. Workers have the choice to represent themselves or hire an attorney to represent them.

The LCO’s Enforcement Unit Provides Judgment Collection Services Free of Charge

If a settlement conference or hearing results in the LCO ordering an employer to pay a worker, the employer has a limited time after service of the LCO’s decision to file an appeal, as explained above . If the employer does not appeal within that period, the LCO files a certified copy of the decision with the appropriate Superior Court and obtains a judgment against the employer for the amount owed. As a matter of practice, the LCO does not request that the judgment be entered against employers who pay within the 10‑day period before the judgment is considered final. When the LCO does request that the court enter the judgment against the employer, the worker can choose the option of referring the judgment to the LCO’s Enforcement Unit for the unit to collect the judgment amount on behalf of the worker. The LCO offers this collection service free of charge, but the worker must choose to refer the judgment to the Enforcement Unit. Workers who choose not to refer the judgment to the Enforcement Unit may pursue collection on their own.

The LCO’s chief deputy and several LCO supervisors report that one or more of three factors may contribute to workers’ decisions not to refer their cases to the Enforcement Unit. After LCO obtains a judgment, staff may not follow up with the worker to determine whether the worker would like to refer the case; the worker may not respond to communications required to complete a referral; or the worker may choose to ask external partners, such as private attorneys or advocacy groups, to help collect the judgment amount. When the worker chooses referral, the Adjudication Unit refers the case to the Enforcement Unit.

The Enforcement Unit uses a variety of means to collect judgment amounts, including levies against employers’ bank accounts and liens on properties. The Enforcement Unit also calculates the interest accrued on any outstanding judgment amounts and includes that in the amount it tries to collect. In response to the unit’s collection efforts, employers may send to the appropriate field office a payment, typically in the form of a check or money order made out to the worker. The field office staff then contact the worker and either mail the payment to the worker or arrange for the worker to pick up the payment from the field office.

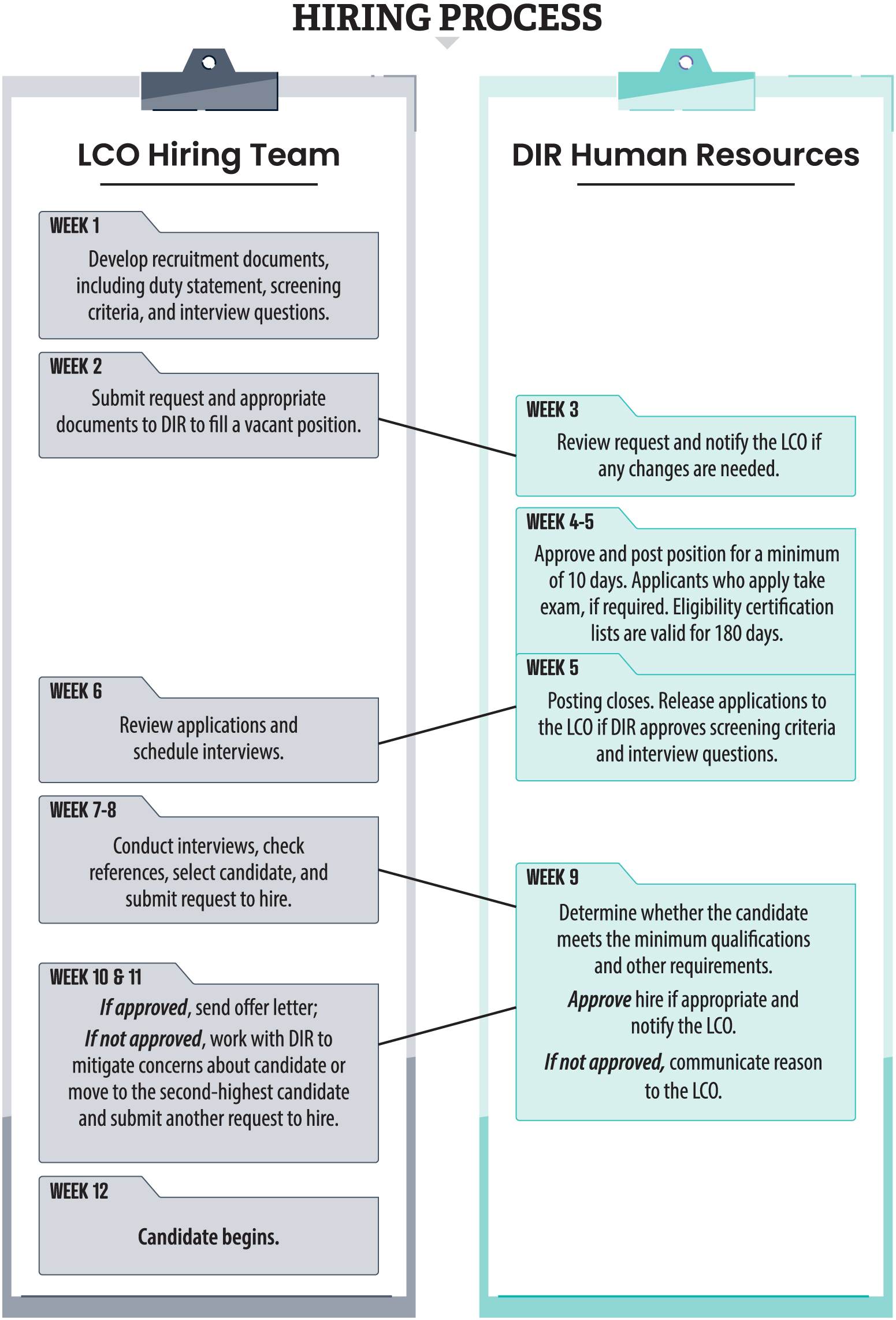

DIR and the LCO Coordinate to Hire LCO Staff

When the LCO needs to fill a vacant position, it coordinates with DIR’s Human Resources staff on the recruitment process. Figure 3 shows DIR’s recruitment process, which ideally takes around 12 weeks. As the figure shows, hiring staff in the LCO must receive approval from DIR’s Human Resources staff before LCO can interview and have the new employee start work. When the LCO identifies a need to fill a position, it submits a request to DIR. After DIR approves the request, it then opens a recruitment to fill the position. The assistant personnel officer of DIR explained that the human resources functions are divided in this way because LCO staff have the subject matter expertise to establish screening criteria, conduct effective interviews, and choose a candidate, and the DIR Human Resources staff have the expertise regarding merit‑based civil service hiring.

DIR’s Hiring Process

Source: DIR’s recruitment and hiring guidelines.

Figure 3 is a color coded flowchart describing Industrial Relations and Labor Commissioner’s hiring process within a twelve week duration. The grey boxes on the left side of the flowchart indicate Labor Commissioner’s human resources hiring process from weeks one to twelve. The teal boxes on the right side of the flow chart indicate Industrial Relations human resources hiring process from weeks three to nine. There are lines connected to certain boxes that represent the process flow between the Labor Commissioner’s Office hiring team and Industrial Relations Human Resources. The grey boxes on the left describe the process of the Labor Commissioner’s Office developing recruitment documents, including duty statements, screening criteria, and interview questions during week one, submitting the request and appropriate documents to Industrial Relations to fill a vacant position during week two. There is a connecting line from the LCO Hiring Team’s week 2 to the Industrial Relations week 3. The teal boxes on the right describe the process of Industrial Relations reviewing the recruitment documents from the Labor Commissioner’s Office during week three, approving and posting the position during weeks four through five, and closing the posting and releasing candidate applications during week five. The next line is from Industrial Relations Human Resources week 5 to the LCO Hiring Teams week 6. The grey boxes on the left describe the process of the Labor Commissioner’s Office reviewing applications and scheduling interviews during week 6, and conducting interviews, checking references, selecting a candidate, and submitting a request to hire the candidate during weeks seven through eight. Then, there is a line from the LCO Hiring Team’s weeks 7-8 to the Industrial Relations Human Resources week 9. During week nine, Industrial Relations either approves or does not approve the chosen candidate. The last line is from Industrial Relations Human Resources week 9 to the LCO Hiring Team’s week 10 & 11. If the candidate is approved by Industrial Relations, an offer letter is sent to the candidate. If the candidate is not approved, the Labor Commissioner’s Office, will work to mitigate concerns about the candidate, or start the hiring process with the next candidate, which takes place during weeks ten and eleven. During week twelve, the hired candidate begins work.

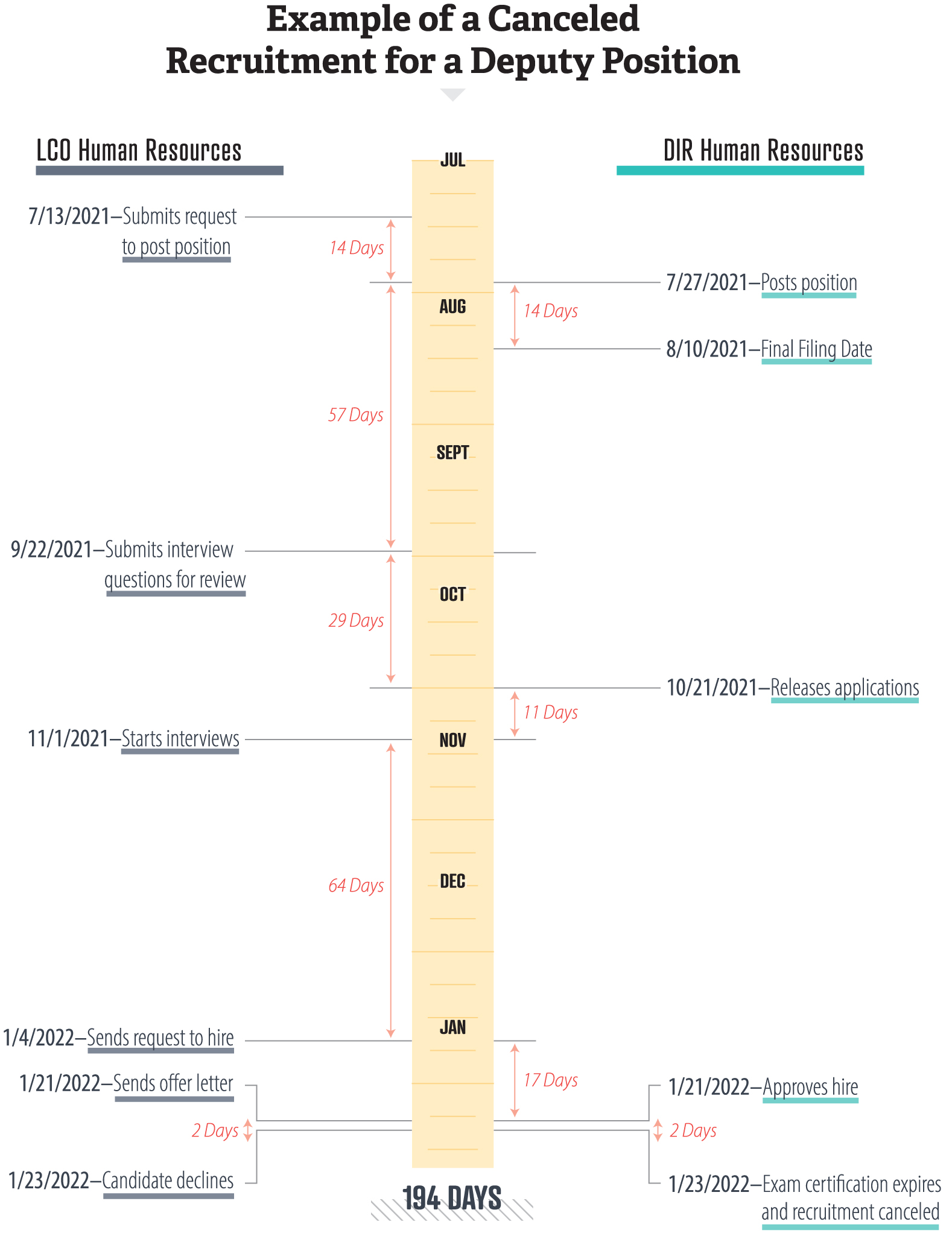

As part of the application process, candidates generally must take a qualifying exam. DIR Human Resources staff then order a certification report of all candidates who are eligible. However, the certification report expires six months after it is generated for a specific recruitment. With rare exceptions, the LCO must fill the position within that time frame or else it must re‑post the job and begin the recruitment process again. After the LCO identifies its top candidate for the position, DIR verifies that the candidate meets the minimum qualifications for the position. If the candidate fails to meet minimum qualifications, the LCO can move to the candidate that ranked second in its selection process. Field office supervisors generally fulfill LCO’s responsibility to conduct interviews of potential candidates, and the LCO must make an offer to a candidate before the expiration of the eligibility certification list. If the LCO does not fill the position within that time, it cancels the recruitment and starts the process again from the beginning.

The LCO Has Not Always Provided Critical Training and Oversight to Its Field Offices

The enforcement unit’s work results in only a small percentage of successful payments to workers.

- State law requires the LCO to issue a decision on a claim within 135 days of the claim’s filing. However, as of the end of fiscal year 2022–23, the LCO took a median time of 854 days to issue a decision, more than six times longer than statute allows.

- The delay in processing claims has created a large backlog of unprocessed claims, which more than doubled in the last five years from 22,000 claims in fiscal year 2017–18 to 47,000 claims at the end of fiscal year 2022–23.

- The LCO’s use of settlement conferences to determine whether to hold a hearing on a claim contributed to the LCO’s ongoing lack of statutory compliance and growing backlog because of significant delays in claim resolution.

- The LCO’s lack of technological infrastructure and its incomplete and inaccurate data hinder its ability to monitor its compliance with statutory requirements and accurately analyze and assess the effectiveness of its wage claims processing.

The LCO Continues to Exceed the Statutory Time Frame for Processing Wage Claims, Resulting in a Large Backlog

From fiscal year 2017–18 through fiscal year 2022–23, the LCO has not complied with statutorily required claim processing times for issuing a decision after receiving a claim. As we discuss in the Introduction , state law requires that the LCO issue a decision on a claim within 135 days after it is filed. However, as Figure 4 shows, the LCO used a median time of 854 days to issue a decision on a claim during fiscal year 2022–23, which is more than six times longer than the maximum of 135 days allowed by law. Further, the median time to process claims has increased since fiscal year 2017–18, meaning the LCO has been taking longer to issue decisions for more than half the claims it processed during this time. In fact, the percentage of claims for which the LCO issued a decision within the statutorily required time over the years has steadily decreased. For example, the LCO issued decisions within 135 days for 157 of about 5,800 claims for which it issued decisions during fiscal year 2017–18. However, it issued decisions within 135 days for only two of more than 3,100 claims for which it issued decisions during fiscal year 2022–23.

The Average and Median Number of Days the LCO Takes to Issue a Decision on Claims Continues to Increase

Source: Analysis of LCO wage claim data.

Note: As Appendix B discusses, we found the LCO’s data to be of undetermined reliability; however, the data were the best available source of information on wage claims.

* The number of claims for which the LCO issued a decision within a year ranged from about 5,800 claims in fiscal year 2017–18 to 3,100 in fiscal year 2022–23.

Figure 4 is a color-coded line graph that describes the average and median number of days the Labor Commissioner’s Office takes to issue a decision on claims from fiscal year 2017-2018 to fiscal year 2022-2023. The y- axis (on the left) illustrates the number of days from zero to 1,080, in increments of 135 days, and the x-axis (at the bottom) illustrates fiscal years 2017-2018, 2018-2019, 2019-2020, 2020-2021, 2021-2022, and 2022-2023 from left to right. A yellow line illustrating the maximum number of days allowed to issue a decision on a claim during those fiscal years follows the x-axis at 135 days. The teal-colored line illustrates the average number of days for the LCO to issue a decision on claims. The teal-colored line starts on the left side of the line graph, and rises as it continues to the right side of the line graph. The following numbers are included on the teal line: an average of 420 days in fiscal year 2017-2018, 457 days in fiscal year 2018-2019, 522 days in fiscal year 2019-2020, 629 days in fiscal year 2020- 2021, 807 days in fiscal year 2021-2022, and 890 days in fiscal year 2022-2023. The grey colored line illustrates an increase of the median number of days the LCO takes to issue a decision on claims during the same period of time. The grey colored line also starts on the left side of the line graph and rises as it continues to the right side of the line graph. The following numbers are included on the grey line: a median of 379 days in fiscal year 2017-2018, 418 days in 2018-2019, 464 days in 2019-2020, 552 days in 2020-2021, 776 days in 2021-2022, and 854 days in 2022-2023.

Although all Adjudication Unit field offices have generally taken more than the statutorily allowed time to process claims, six field offices took much longer than the statewide average of 890 days to process claims before issuing a decision during fiscal year 2022–23. As Table 1 shows, the Los Angeles field office issued a decision on a claim an average of 1,123 days after receiving a claim. It took the Oakland field office an average of 1,483 days to issue a decision after receiving a claim. Similarly, those who filed claims with the San Francisco field office waited an average of 1,435 days for a decision. During these long delays, workers may have gone without wages that they had counted on receiving months or years ago. The delays also increase the potential risk that the employers will have closed their businesses, filed for bankruptcy, or liquidated assets in the meantime, which would make recovering owed wages increasingly difficult.

Continuous delays in processing claims have resulted in a corresponding increase in the backlog of unresolved claims—claims open more than the statutorily allowed 120 days between the LCO’s receiving a claim and holding a hearing—each fiscal year. 1 As Table 2 shows, the LCO closed fewer claims from fiscal years 2017–18 through 2022–23 than it received in all but one fiscal year. Consequently, the number of open claims has generally increased over the years. The pandemic that affected fiscal year 2020–21 sharply reduced the number of claims the LCO received to 15,000 claims, compared to the usual average of about 30,000 claims per fiscal year. However, in the following fiscal year, the number of claims that the LCO received returned to the previous average after the LCO launched the online claim portal in English and Spanish and reopened claims that had been closed because of extenuating circumstances stemming from the pandemic. The LCO’s backlog increased significantly, from 28,000 claims at the beginning of fiscal year 2020–21 to 47,000 claims at the end of fiscal year 2022–23, further emphasizing the fact that the LCO struggles to resolve new wage claims and those in its backlog in the time frames set by state law.

Our review of the LCO’s claims processing data found that nearly 33,000 claims have been part of the LCO’s backlog for a minimum of three years as of November 2023. Between January 2018 and November 2023, the LCO had processed and closed almost 2,400 claims that had remained unresolved for five years or more. However, more than 2,800 claims that were in the LCO’s backlog for five years or more were still open as of November 2023. This part of the backlog represents 2,600 workers who may be owed more than $63.9 million in unpaid wages, an average of more than $24,000 per worker. As Table 3 shows, all 17 field offices experienced an increase in backlog ranging from 7 percent to more than 1,900 percent from the beginning of fiscal year 2017–18 through the beginning of fiscal year 2023–24. Although the Redding and Van Nuys field offices managed to reduce their backlogs of claims from fiscal years 2017–18 through 2022–23, both had larger backlogs at the beginning of fiscal year 2023–24 than they had at the beginning of fiscal year 2017–18. In fact, as of November 1, 2023, the LCO’s Van Nuys field office had 28 new claims that had not been scheduled for a conference or hearing, despite having been received between 2017 and 2021.

The lengthy delays and backlog mean that workers must wait months, if not years, to receive owed wages, potentially undermining the timelines outlined in California law. In one egregious example, a worker filed a claim with the Van Nuys field office in September 2014. According to LCO’s case management system’s data, the Van Nuys field office held the first settlement conference in January 2015 but did not schedule a hearing for another four years until July 2019. The delay extended even further when the LCO improperly served the notice of hearing and held another settlement conference before scheduling the hearing. The LCO subsequently rescheduled the hearing an additional four years later, in August 2023, but the case management notes do not provide a reason for the extensive delay in rescheduling the hearing. Then, because of the assigned hearing officer’s unavailability, the LCO canceled the hearing and instead facilitated a third conference on the hearing date. The worker offered to settle the claim for less than half of what the LCO identified as owed to the worker; however, the defendant refused the settlement offer at the conference. The LCO had yet to reschedule the hearing as of March 2024. According to LCO’s case management notes, the worker, who served as a caregiver for clients who are since deceased, has more than $71,000 in outstanding claims—not including interest—for unpaid overtime, unpaid mileage reimbursements, and for wages that were paid at a rate less than the minimum wage. Almost 10 years after filing the claim for unpaid wages, the worker still has not received a decision on the claim. We discuss the factors contributing to such delays later in this report.

The LCO’s Current Process for Determining the Need for a Hearing Is Inefficient and Ineffective

The LCO’s process for scheduling the settlement conference makes it impossible for it to comply with the statutory requirement to determine whether a hearing is necessary. State law requires the LCO to determine whether a hearing is to be held for a claim and notify the parties within 30 days of the claim’s filing. Although not required by state law, the LCO requires staff to hold a settlement conference to determine whether a hearing is needed. In order to determine within 30 days whether a hearing is needed, the LCO would have to hold a settlement conference within 30 days of receiving the claim. However, the LCO expects its staff to notify the involved parties of the scheduled settlement conference between 45 days and 60 days before the date of the conference. Providing 45 to 60 days’ notice makes it impossible for the LCO to hold a settlement conference within 30 days of receiving a claim.

Moreover, the LCO’s data show that settlement conferences often do not yield intended results. Although holding settlement conferences can potentially decrease the need for holding a hearing because a settlement between the parties eliminates the need for a hearing to decide the claim, the LCO’s data show that nearly 40 percent of scheduled conferences result in an absence by either one or both parties to the claim. According to the LCO’s guidance for workers filing claims, if the employer does not attend the settlement conference, the claim still proceeds to a hearing. If the worker fails to attend the settlement conference and cannot show good cause for not attending, the LCO will close the worker’s claim.

Additionally, the LCO data show that settlement conferences result in a small percentage of settlements and thus often do not prevent claims from requiring a hearing. The LCO scheduled settlement conferences for approximately 130,000 claims between July 2018 and November 2023 to determine whether a hearing was required. However, the LCO data show that only 21,000 claims, or 16 percent of claims for which the LCO scheduled settlement conferences, were actually settled during the conference, which suggests that settlement conferences do not result in significantly fewer hearings. Further, nothing prevents the parties to the claim from settling before a hearing, even in the absence of a settlement conference. In fact, in more than 9,400 of the claims for which deputies determined that a hearing was necessary, the claims were settled before the hearing or at the hearing. These data show that the LCO can continue to attempt to settle claims without requiring that staff hold a settlement conference before making a determination about the necessity of a hearing.

The LCO Lacks the Technological Infrastructure and Staffing Necessary to Effectively Oversee and Improve Its Data and Wage Claim Process

The LCO began using the Salesforce platform in 2016 to host the LCO’s cloud‑based database and case management system for all wage claims. The LCO uses this case management system to track and monitor the progress of each claim and the various stages of claim processing. This system allows the LCO to customize the database and reports to fit its needs. The database allows field office supervisors, regional managers, and LCO leadership to generate various reports for overseeing field offices’ claims processing efforts and aligning staff availability with claim processing efforts. However, the database does not use key data fields to support statutory compliance, and the existing data is incomplete and some of it is inaccurate. Significantly, the agency lacks a process for ensuring the accuracy of the data placed into its database. These weaknesses hamper the LCO management’s ability to provide proper oversight of the claims process.

Currently, the Adjudication Unit does not use fields in its case management system that, if used consistently and accurately, would allow the LCO to readily track and monitor compliance with all statutory requirements for claims as they are processed. Our review of the data fields available in Salesforce for case management identified nearly 30 data fields that exist on the platform and would greatly improve the Adjudication Unit’s oversight of the claims process, yet the Adjudication Unit does not use those fields. For example, the Adjudication Unit’s case management system does not include a field to capture the date on which the LCO notified parties of whether a hearing is needed. However, there are several data fields in Salesforce, currently used by another unit within the LCO, that the Adjudication Unit could use to capture various data, including the date when the LCO notifies parties that it has determined that a hearing is necessary. Without this date, the LCO cannot track whether it complied with the requirement to determine within 30 days of receiving a complaint whether a hearing is needed. In fact, because the LCO lacks data to determine the LCO’s compliance with this requirement, we had to use the settlement conference date to measure its backlog.

Furthermore, the date that the LCO received claims was sometimes missing or incorrect, which impedes the LCO’s ability to readily identify and track key claim processing benchmarks. For example, we identified nearly 6,000 claims of more than 200,000 (about three percent) for which the claim‑received date was missing. Without this date, the LCO can neither track how long these claims have been active nor track how long these claims have taken to move through each stage of the claim process. The LCO staff speculated that these errors were likely caused by the migration of data from an old database system to the new case management system and were not a result of human error. However, when we reviewed 48 randomly selected claims that the LCO received after the completion of the data migration, we found that the claim‑received dates for 20 claims occurred after the dates those claims were closed. The LCO confirmed that only four of these 20 errors were a result of data migration. The LCO attributed the incorrect dates for the remaining 16 claims to staff incorrectly entering dates into the database. Upon reviewing the 48 claims, the LCO further determined that the case closure dates for eight claims were entered incorrectly. Although the LCO took steps in June 2023 to require that the claim‑received date be entered and to ensure that the field is automatically populated for claims filed online, the missing or incorrect claim‑received date is just one example of the significant concerns regarding data accuracy and completeness that we identified during the course of this audit.

Also of concern is that the LCO lacks a process to ensure the accuracy of claims data. This absence of a quality control for its data significantly impairs the agency’s ability to precisely identify and track backlogged claims. For example, we identified a claim for $3,300 that the LCO received in June 1996 and closed in August 2022, appearing to have been in the backlog for 26 years. However, upon further review, we found that the claim was actually filed in March 2022 and was open for only five months. LCO staff had incorrectly entered the worker’s date of birth as the date the claim was received. The LCO corrected these errors after we made LCO management aware of them. The LCO failed to catch these errors because it does not have a process to review and correct data entry errors on an ongoing basis. The lack of accurate and complete data impedes the LCO’s ability to ensure statutory compliance and to monitor the effectiveness of its claims processing.

Moreover, although the case management system provides the LCO with data entry and reporting functions for each stage of the claim process, the reports it generates do not allow the LCO to track and monitor each wage claim across the life cycle of the claim. Although the LCO has the ability to extract all data for every claim, the case management system ineffectively generates duplicate records in certain report formats: we found that it requires considerable time, effort, and knowledge to derive reliable data from those reports for further analysis. Currently, if LCO staff generate a report that captures data from all conferences and hearings on a claim, the case management system will create multiple records that require further filtering for data analysis. For example, the LCO created a report for us with all data related to all claims between July 2017 and November 2023. However, when we extracted the data from the report for further analysis, the extracted data contained multiple rows of data for the same claims. Specifically, we identified more than 150,000 duplicate claims from approximately 525,000 claims that were closed after July 2017 or were still open as of November 2023. The LCO has not yet determined whether the issue is inherent to the design of the case management system and whether it is correctable.

Upon further review, we also found that many of these duplicate records were related to settlement conferences and were erroneously entered by field office deputies. Specifically, according to LCO staff, some deputies created multiple entries in the case management system for rescheduled conferences instead of revising the entry for the original conference. The LCO asserts that these erroneous entries are not consistent with the training and procedures that deputies receive. However, the erroneous settlement conference entries present additional data accuracy concerns. The LCO has limited ability to review the claim process to identify staffing needs or identify bottlenecks in the process that contribute to long wait times and the growing backlog.

The LCO recently began a business process improvement initiative to redesign the case management system to improve the quality of claim data collected when workers file claims and to increase training resources for the LCO staff to improve user experiences. However, the labor commissioner stated that the LCO has not had a formal technology business team as part of its infrastructure to support the LCO’s rollout and use of the case management system and to provide timely technical support to the LCO staff. The LCO instead had relied on a team of experienced users to provide support and ad hoc training to others, under the leadership of a former LCO assistant chief who retired in 2023. The labor commissioner intends to add resources in the LCO headquarters to provide ongoing support and training to staff and work with DIR staff to fix system issues.

Ultimately, the lack of sufficient technology resources and infrastructure, coupled with inaccurate and incomplete data, limits the LCO’s ability to manage and improve its wage claim process. The LCO cannot efficiently respond to inquiries on claims, and its management team is hindered in its oversight of wage claim processing at the field office level. Further, the lack of quality data limits the LCO’s ability to assess its workload and staffing for resolving claims within statutory time limits, which we discuss later .

- High vacancy rates that range from 10 percent to 45 percent in most field offices are the primary reason for the many delays in processing claims. Existing staff workloads are high, preventing supervisors from assigning claims and scheduling conferences and hearings in a timely manner.

- The LCO has performed limited staffing analysis. However, drawing on our analysis of available data, we estimate that the LCO needs additional positions to resolve the backlog.

- Salaries for key positions in the Adjudication Unit are not comparable to similar state and local government positions. These low wages contribute to the agency’s retention problems and difficulty filling positions.

- The hiring process takes too long, resulting in numerous canceled recruitments for the LCO that exacerbate the vacancy rate and wage claim backlog.

Inadequate Staffing Is the Primary Reason for the LCO’s Delays in Processing Wage Claims

Since the LCO’s case management system does not include any global data on the reasons that claim processing was delayed, we judgmentally selected 40 claims that were closed more than 135 days after the office received them, five each from field offices in Los Angeles, Oakland, Long Beach, Sacramento, San Diego, San Bernardino, Stockton, and Santa Rosa. We selected the Los Angeles, Oakland, and Long Beach field offices because they had the highest backlog of claims in calendar year 2022, the most recent complete year available at the time of our review, and those filed offices had the highest average number of days from receipt of the claim to the claim closure date. We selected the field offices in Sacramento, San Bernardino, San Diego, Santa Rosa, and Stockton because they had the highest percentage increase in backlog of claims in the past three years. Although these offices had processed some claims within the required 135 days, the vast majority of the claims these offices closed between 2018 and November 2023 had been open for more than 135 days.

Our review found that field offices did not hold settlement conferences and did not make decisions about whether the LCO would take further action on claims in a timely manner for the claims we reviewed. In accordance with the LCO’s process, 34 of the 40 claims we reviewed required a settlement conference, the first step in resolving a claim and one that helps to determine whether a hearing is necessary. State law requires the LCO to make the determination to hold a hearing and notify the parties of that decision within 30 days of receiving the claim. However, for all 34 claims we reviewed that required a settlement conference, the assigned deputies did not hold settlement conferences within 30 days to determine whether a hearing was necessary. For 20 of these 34 claims, the assigned deputies did not hold a settlement conference within 135 days, which is the maximum statutory deadline for completely resolving a claim and issuing a decision. Of the 40 claims we reviewed, seven were closed due to various reasons. A field office can take no further action on a claim for certain procedural reasons, such as the LCO not having jurisdiction. However, field offices were also late in making these determinations—from 510 to 1,631 days after the seven claims were received. In one claim that the LCO did not assign to a deputy until 438 days after receiving it, the worker died before the hearing. Consequently, the claim was closed.

According to the field office staff responsible for processing the claims we reviewed, lack of staff was the primary factor for delays in adjudicating claims. For nine claims at five of the eight field offices we reviewed, the respective field office supervisor did not assign a deputy to the claim for more than 100 days, generally because the field office had too few deputies. For instance, for one of the claims we reviewed at the Sacramento field office, the field office supervisor assigned a deputy to the claim 370 days—more than a year—after the claim was received. The supervisor stated that the delay in assigning the claim to a deputy occurred because all deputies maintained substantial workloads at the time.

At the Oakland field office, a claim was reassigned multiple times, which added to the delay. The field office supervisor explained that the claim was initially assigned to a deputy who was then promoted to hearing officer, which reduced the number of available deputies. The field office supervisor noted that she could not immediately reassign the claim because there was an insufficient number of deputies available. In December 2023, at the same field office, which receives some of the highest numbers of claims of any field office each year, the office’s only deputy retired. As a result, the Oakland office did not have a deputy to process claims as of February 2024, when the field office supervisor stated that the office had more than 3,000 unassigned claims. To remedy the situation, the field office supervisor began monitoring the claims to close them or to determine the potential next steps. However, also in February 2024, the field office supervisor transferred to another department. LCO management stated that as of March 2024, a request to hire for a deputy position was currently pending. Management explained that it also plans to use an expedited time frame to re‑hire a retired deputy for that office as a retired annuitant and is recruiting for additional deputy positions for the Oakland field office. However, the workers whose claims are unassigned will face a long delay in having their claims heard and may face financial hardship in the interim.

Significant delays also occurred in holding the hearing for the claims that deputies had determined required a hearing. State law requires the LCO to hold a hearing within 90 days of determining that a hearing is necessary, a determination that generally occurs after the settlement conference, according to the LCO’s process. Of the 34 claims we reviewed for which the field offices held a settlement conference, 21 required a hearing. However, deputies did not schedule a hearing for these claims until 48 days to 1,589 days after they had determined that a hearing was necessary. For six of these 21 claims, the deputies scheduled the hearing more than 500 days after determining that a hearing was necessary. For example, the San Diego field office did not hold a hearing for one of the claims for 921 days after the settlement conference. The Long Beach field office held a hearing for a claim 895 days after the settlement conference. In the most extreme case, the Oakland field office did not hold a hearing until 1,589 days after the settlement conference.

Just as field staff explained that claims processing was delayed because of the shortage of deputies to process claims, field office staff also explained that the hearing officer shortage was the reason for the delays in holding hearings. For instance, the Long Beach field office took more than 300 days after the settlement conference to hold a hearing for two claims we reviewed. The field office supervisor explained that the office lacked an adequate number of hearing officers at that time, which created delays. The former supervisor for the Oakland field office, which did not hold a hearing for one of the claims we reviewed for more than 1,500 days after the settlement conference, stated that the primary cause for the delay was lack of staffing.

Other field office staff we interviewed also pointed to inadequate staffing as the primary cause for delays in processing claims. We selected 20 field office staff to interview about various topics related to the audit, including the wage claim backlog and delays in processing claims. We chose five office technicians, four industrial relations representatives, five deputies, and six hearing officers from seven field offices. When we asked these staff for their perspectives on the cause of the backlog, several pointed to insufficient staffing. For example, an industrial relations representative noted that their field office was supposed to have five office technicians but that all five positions were vacant. A deputy at a different field office explained that having too few office technicians made it difficult to process claims more effectively and assign them quickly. A hearing officer at another field office told us that having insufficient staffing resulted in existing staff’s having to perform the duties of multiple positions.

Several staff also stated that answering calls from workers who had already filed claims or from those who had questions about doing so and providing information to the public consumed an inordinate amount of their time. For example, a deputy explained that they could not concentrate on conducting conferences because they divide much of their time across administrative tasks, including answering phones. Although deputies are expected to perform some public information duties, some of the deputies we interviewed said that they had to devote so much time to this task that it interfered with their other duties. One deputy explained that when staff leave the department, the public information duties for remaining staff, such answering calls, increases. Another deputy believed that a separate unit should handle those duties.

The LCO’s data show that most field offices have high vacancy rates. As Table 4 shows, the vacancy rates for the field offices we reviewed ranged from 44 percent at Sacramento to 33 percent at San Bernardino and San Diego, as of June 2023. Only Santa Rosa had no vacancies, as of June 2023. In fact, the number of statewide vacancies for the Adjudication Unit has steadily increased from 12 positions of 196 in fiscal year 2017–18 to 91.5 positions of 274.5 in fiscal year 2022–23, an increase in vacant positions of more than 600 percent. Field offices with high vacancy rates also have large backlogs, as Table 4 shows.

These vacancies include all the key positions in the Adjudication Unit, particularly deputies, as Table 5 shows. Specifically, 38 percent of the deputy positions in the Adjudication Unit were vacant as of the end of fiscal year 2022–23. Although the Santa Rosa field office had no vacancies at that point, that office still had a backlog of wage claims. Later in the report, we discuss the number of filled positions the LCO would need to process both the backlog and new claims. Appendix A presents additional detailed information on the numbers of vacant and filled positions at each field office.

Insufficient staffing affects the workload each deputy carries and affects the availability of those deputies to focus on processing claims. As the text box shows, the LCO has developed workload expectations for various staff positions in the Adjudication Unit; these expectations include the number of conferences or hearings that staff should schedule each month. LCO management explained that field office supervisors are expected to monitor and track the number of conferences and hearings that staff have scheduled each month. However, field office staff stated that they have more claims assigned than they are expected to process or can handle. One deputy stated that they currently have more than 700 claims assigned to them in different stages of the wage claim adjudication process. Another deputy stated they were managing more than 300 claims. These caseloads far exceed the 40 to 50 settlement conferences for which a deputy should be responsible at any given point. The high workloads affect other staff as well. An office technician we interviewed stated that the work became very overwhelming and that the field office had to switch the technician’s duties with those of a more experienced office technician.

Monthly Workload Expectations for Adjudication Unit Staff

Industrial relations representative

- 35 settlement conferences for less complex claims

- 40 to 50 settlement conferences depending on complexity of claims

Hearing officer

- 30 to 40 hearings related to wage theft claims

- 1 to 2 citations hearings

Source: 2022 DIR Adjudication Unit expectations memo.

The LCO has made some efforts to reduce the backlog in field offices with significant numbers of backlogged claims, but not all efforts have been successful. For example, the LCO piloted a strategy in May 2022 that focused on expediting claims for low‑wage workers at four field offices. However, LCO management explained that low staffing levels and an inconsistent categorization of cases as “low‑wage” meant that deputies had to spend time determining whether a case was properly designated as a low‑wage case and, if not, reassign the case. The backlog of non‑low‑wage cases also grew as a result of this effort. LCO management stated that it subsequently determined that the four field offices did not have the staff capacity to ensure the success of the effort at this time. The LCO noted that statistics showed that low‑wage claims did get processed faster and that although it put the project on hold, LCO management plans to continue it in the future.

The LCO initiated another program in May 2022 at the San Bernardino and San Diego field offices that has been more successful. This program involved scheduling conferences for claims that were not complex in nature during a very short period. For example, LCO management stated that in August 2022, 665 conferences were held at the two field offices. The conferences were expanded during 2023 to additional field offices, including Oakland. According to LCO management, the pilot program helped to decrease the backlog of wage claims by 60 percent for claims awaiting a conference. For example, the LCO stated that the San Bernardino field office had approximately 5,000 claims with pending conferences, the oldest claim having been filed in 2019. The LCO told us that after the pilot program closed, there were approximately 2,000 claims left in the backlog, the oldest having been received in August 2022. LCO management stated that it plans to perform additional concentrated conferences in the future as the LCO refines the process and that it has already conducted multiple conferences for claims involving employers with multiple claims filed against them.

The LCO Has Not Adequately Identified Staffing Needs for Balancing Staff Workload

Although insufficient staffing is the primary reason for delays in processing claims, the LCO has performed limited analysis to determine the estimated workload for its existing staff who are currently processing wage claims and to support the Budget Change Proposals it submitted to the Department of Finance requesting additional staff. The LCO said that it required a number of additional staff to resolve new claims in the time frame required by state law and to resolve its backlogged claims. Using its limited analysis, the LCO has requested and received approval for additional staff positions since fiscal year 2016–17; however, many authorized positions remain vacant as of fiscal year 2022–23. As a result, as we discuss earlier , the LCO is still struggling to resolve claims within statutory time frames, resulting in longer wait times and a rapidly growing backlog of claims.

Further, according to the LCO, claims have become more complex because of new laws, and the claims’ increasing complexity has resulted in more workers’ claims being referred to a hearing and in an increase in employer appeals of field enforcement citations. The LCO explained that such developments can affect its ability to hold timely hearings on all claims. For example, a law that became effective in January 2003 requires certain employers to provide written notices 60 days in advance of mass layoffs, relocations, or terminations to employees and various public agencies. Under the provisions of Assembly Bill 1601 specific to call center workers, which became effective January 1, 2023, investigations of employers’ call center relocation violations can require the LCO staff to spend significant time to analyze the call center’s call volume to determine whether a violation occurred. Assembly Bill 1601 also increased the LCO’s authority to issue citations for violations of the notice requirements. Under existing law, employers can contest citations by requesting an informal hearing, which the LCO’s Adjudication Unit hearing officers conduct. The LCO is also statutorily required to issue a decision on the citation appeal within 15 days of the hearing’s conclusion.

In a different example, existing law permits an employee to accrue and use paid sick days for certain purposes, including caring for an employee’s family member. Effective in January 2023, the definition of “family member” expanded to include a designated person , which is defined as a person identified by the employee at the time the employee requests paid sick days. This means that an additional person who is not otherwise already identified in statute can be the employee’s designated person for purposes of using paid sick leave. The LCO expects that the new law could increase the complexity of the claims, some of which are already complex, requiring additional time and staff resources to process.

The LCO asserted that regardless of staffing, it may not be able to meet required time frames for processing all claims because of the complexities of some claims. However, the LCO does not have the necessary data to quantify the affect these new laws have had or will have on its workload. However, the LCO does not identify which claims are complex, and it has not performed any analysis to support its assertion. Although some claims’ complexities resulting from changes in laws will affect the LCO’s ability to process those claims within the required time frames, the LCO cannot quantify the extent to which it cannot meet required time frames because it lacks data. Drawing on available data, we estimated the number of staff that the LCO currently needs to resolve all claims. To determine whether the LCO has the required number of staff to process all claims in a timely manner, we obtained from the LCO its estimate of the average number of hours that staff in each position spend on different activities related to processing each claim and on activities not related to processing claims. We then multiplied these estimated hours for various activities by the number of existing and new claims to determine the total number of hours needed, by position, to resolve those claims. Using 1,776 hours that the State identifies as hours that a staff in a full‑time position works during a year, we determined the total number of staff needed to process all claims by position classification. We determined the number of field office supervisors and management by using a ratio prescribed by the California Department of Human Resources (CalHR).

Our analysis of the LCO’s staffing and workload data determined that its Adjudication Unit, as currently staffed, does not have the capacity to resolve claims in a timely fashion nor to provide adequate levels of supervision to monitor and track claim processing. We estimate that the LCO needs at least 892 total full‑time positions to resolve the backlog and new claims and provide appropriate supervisory coverage, as Table 6 shows. Further, we estimate that the LCO would need 209 deputies to address backlog and new claims as of November 1, 2023. It currently has 80 authorized positions for deputies. Thus, it would need an additional 129 deputy positions. We estimate that the LCO needs 64 additional hearing officers to hear existing claims and 140 additional field office supervisors and regional manager positions. Our analysis did not include the approximately 36 IT staff and IT supervisors that the LCO estimates are needed to create technology infrastructure and provide technical support related to its case management system.

By assessing its current procedures for processing claims, however, the LCO may be able to reduce the number of staff required. As we describe earlier, the LCO’s current procedure of requiring a settlement conference before deciding whether a hearing is needed contributes to the delays in processing claims. If the LCO were to remove the requirement to hold a settlement conference before determining whether to hold a hearing, the agency could significantly reduce the number of staff and supervisors needed from 892 to 702, as Table 6 shows.

The director of DIR asserts that the LCO must fill its 159 current vacant positions before requesting additional position authorizations through a budget change proposal. However, our analysis of the backlog, new claims, existing staffing structure, and staff workloads shows that the LCO’s need for additional staff and appropriate supervisor allocations to resolve new claims in a timely manner in addition to resolving the existing backlog is urgent and should not be tied solely to the filling of existing vacancies.

Low Salaries May Contribute to the LCO’s High Staff Vacancy Rates