- Bound reading assignment for the classroom

HINTS AND TIPS:

Before giving away the correct answer, here are some more hints and tips for you to guess the solution on your own!

1. The first letter of the answer is: T

2. the last letter of the answer is: k, 3. there are 3 vowels in the hidden word:.

CORRECT ANSWER :

Other Related Levels

If you successfully solved the above puzzle and are looking for other related puzzles from the same level then select any of the following:

- Diplomatic delegate

- Young not fully mature

- Symbolic representation used in dance or chess

- Metal fencing outside schools maybe

- Single protracted sound voice or note

- 1995 film took Pixar to infinity and beyond

- The premise or trajectory of a novel

- Not crooked in a perfect line

- Kids little ones

- Wet and slimy hard to get a grip of

- Severe throbbing headache

- Velociraptor is a quick and clever one

- Chinese tile matching game

- Wicker cradle

- Measurement from edge to edge across a circle

- Notification so you dont forget an appointment

- Moving through water by using your arms and legs

- Opposite of negative

- Providing food for events parties ceremonies

If you already solved this clue and are looking for other clues from the same puzzle then head over to CodyCross Greece Group 674 Puzzle 5 Answers .

Bound reading assignment for the classroom CodyCross

Thank you for visiting our website, which helps with the answers for the CodyCross game. With this website, you will not need any other help to pass difficult task or level. It helps you with CodyCross Bound reading assignment for the classroom answers, some additional solutions and useful tips and tricks. This game is made by developer Fanatee Inc, who except CodyCross has also other wonderful and puzzling games.

Bound reading assignment for the classroom CodyCross Answers:

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Having trouble solving the crossword clue " Bound reading assignment for the classroom "? Why not give our database a shot. You can search by using the letters you already have!

Bound reading assignment for the classroom – Crossword Clue

Below are possible answers for the crossword clue Bound reading assignment for the classroom .

Add your Clue & Answer to the crossword database now.

Codycross Greece Group 674 Puzzle 5

- Diplomatic delegate

- Young, not fully mature

- Bound reading assignment for the classroom

- Symbolic representation used in dance or chess

- Metal fencing outside schools maybe

- Single protracted sound, voice or note

- 1995 film took Pixar to "infinity and beyond"

- The premise or trajectory of a novel

- Not crooked, in a perfect line

- Kids, little ones

- Wet and slimy, hard to get a grip of

- Severe, throbbing headache

- Velociraptor is a quick and clever one

- Chinese tile matching game

- Wicker cradle

- Measurement from edge to edge across a circle

- Notification so you don't forget an appointment

- Moving through water by using your arms and legs

- Opposite of negative

- Providing food for events, parties, ceremonies

- Planet Earth

- Under The Sea

- Culinary Arts

- Fauna And Flora

- Ancient Egypt

- Amusement Park

- Medieval Times

- Science Lab

- New York New York

- Popcorn Time

- La Bella Roma

- Department Store

- Fashion Show

- Welcome To Japan

- Concert Hall

- Home Sweet Home

Bound Reading Assignment For The Classroom - CodyCross

Bound Reading Assignment For The Classroom Exact Answer for CodyCross Greece Group 674 Puzzle 5 .

Answer for Bound Reading Assignment For The Classroom

Same puzzle crosswords, other worlds, last levels, other games.

3.3 Effective Reading Strategies

Questions to Consider:

- What methods can you incorporate into your routine to allow adequate time for reading?

- What are the benefits and approaches to active and critical reading?

- Do your courses or major have specific reading requirements?

Allowing Adequate Time for Reading

You should determine the reading requirements and expectations for every class very early in the semester. You also need to understand why you are reading the particular text you are assigned. Do you need to read closely for minute details that determine cause and effect? Or is your instructor asking you to skim several sources so you become more familiar with the topic? Knowing this reasoning will help you decide your timing, what notes to take, and how best to undertake the reading assignment.

Depending on the makeup of your schedule, you may end up reading both primary sources—such as legal documents, historic letters, or diaries—as well as textbooks, articles, and secondary sources, such as summaries or argumentative essays that use primary sources to stake a claim. You may also need to read current journalistic texts to stay up to date in local or global affairs. A realistic approach to scheduling your time to allow you to read and review all the reading you have for the semester will help you accomplish what can sometimes seem like an overwhelming task.

When you allow adequate time in your hectic schedule for reading, you are investing in your own success. Reading isn’t a magic pill, but it may seem like it when you consider all the benefits people reap from this ordinary practice. Famous successful people throughout history have been voracious readers. In fact, former U.S. president Harry Truman once said, “Not all readers are leaders, but all leaders are readers.” Writer of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, inventor, and also former U.S. president Thomas Jefferson claimed “I cannot live without books” at a time when keeping and reading books was an expensive pastime. Knowing what it meant to be kept from the joys of reading, 19th-century abolitionist Frederick Douglass said, “Once you learn to read, you will be forever free.” And finally, George R. R. Martin, the prolific author of the wildly successful Game of Thrones empire, declared, “A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies . . . The man who never reads lives only one.”

You can make time for reading in a number of ways that include determining your usual reading pace and speed, scheduling active reading sessions, and practicing recursive reading strategies.

Determining Reading Speed and Pacing

To determine your reading speed, select a section of text—passages in a textbook or pages in a novel. Time yourself reading that material for exactly 5 minutes, and note how much reading you accomplished in those 5 minutes. Multiply the amount of reading you accomplished in 5 minutes by 12 to determine your average reading pace (5 times 12 equals the 60 minutes of an hour). Of course, your reading pace will be different and take longer if you are taking notes while you read, but this calculation of reading pace gives you a good way to estimate your reading speed that you can adapt to other forms of reading.

In the table above, you can see three students with different reading speeds. So, for instance, if Marta was able to read 4 pages of a dense novel for her English class in 5 minutes, she should be able to read about 48 pages in one hour. Knowing this, Marta can accurately determine how much time she needs to devote to finishing the novel within a set amount of time, instead of just guessing. If the novel Marta is reading is 497 pages, then Marta would take the total page count (497) and divide that by her hourly reading rate (48 pages/hour) to determine that she needs about 10 to 11 hours overall. To finish the novel spread out over two weeks, Marta needs to read a little under an hour a day to accomplish this goal.

Calculating your reading rate in this manner does not take into account days where you’re too distracted and you have to reread passages or days when you just aren’t in the mood to read. And your reading rate will likely vary depending on how dense the content you’re reading is (e.g., a complex textbook vs. a comic book). Your pace may slow down somewhat if you are not very interested in what the text is about. What this method will help you do is be realistic about your reading time as opposed to waging a guess based on nothing and then becoming worried when you have far more reading to finish than the time available.

Chapter 2 , “ Managing Your Time and Priorities ,” offers more detail on how best to determine your speed from one type of reading to the next so you are better able to schedule your reading.

Scheduling Set Times for Active Reading

Active reading takes longer than reading through passages without stopping. You may not need to read your latest sci-fi series actively while you’re lounging on the beach, but many other reading situations demand more attention from you. Active reading is particularly important for college courses. You are a scholar actively engaging with the text by posing questions, seeking answers, and clarifying any confusing elements. Plan to spend at least twice as long to read actively than to read passages without taking notes or otherwise marking select elements of the text.

To determine the time you need for active reading, use the same calculations you use to determine your traditional reading speed and double it. Remember that you need to determine your reading pace for all the classes you have in a particular semester and multiply your speed by the number of classes you have that require different types of reading. The table below shows the differences in time needed between reading quickly without taking notes and reading actively.

Practicing Recursive Reading Strategies

One fact about reading for college courses that may become frustrating is that, in a way, it never ends. For all the reading you do, you end up doing even more rereading. It may be the same content, but you may be reading the passage more than once to detect the emphasis the writer places on one aspect of the topic or how frequently the writer dismisses a significant counterargument. This rereading is called recursive reading.

For most of what you read at the college level, you are trying to make sense of the text for a specific purpose—not just because the topic interests or entertains you. You need your full attention to decipher everything that’s going on in complex reading material—and you even need to be considering what the writer of the piece may not be including and why. This is why reading for comprehension is recursive.

Specifically, this boils down to seeing reading not as a formula but as a process that is far more circular than linear. You may read a selection from beginning to end, which is an excellent starting point, but for comprehension, you’ll need to go back and reread passages to determine meaning and make connections between the reading and the bigger learning environment that led you to the selection—that may be a single course or a program in your college, or it may be the larger discipline, such as all biologists or the community of scholars studying beach erosion.

People often say writing is rewriting. For college courses, reading is rereading, but rereading with the intention of improving comprehension and taking notes.

Strong readers engage in numerous steps, sometimes combining more than one step simultaneously, but knowing the steps nonetheless. They include, not always in this order:

- bringing any prior knowledge about the topic to the reading session,

- asking yourself pertinent questions, both orally and in writing, about the content you are reading,

- inferring and/or implying information from what you read,

- learning unfamiliar discipline-specific terms,

- evaluating what you are reading, and eventually,

- applying what you’re reading to other learning and life situations you encounter.

Let’s break these steps into manageable chunks, because you are actually doing quite a lot when you read.

Accessing Prior Knowledge

When you read, you naturally think of anything else you may know about the topic, but when you read deliberately and actively, you make yourself more aware of accessing this prior knowledge. Have you ever watched a documentary about this topic? Did you study some aspect of it in another class? Do you have a hobby that is somehow connected to this material? All of this thinking will help you make sense of what you are reading.

Application

Imagine that you were given a chapter to read in your American history class about the Gettysburg Address, now write down what you already know about this historic document. How might thinking through this prior knowledge help you better understand the text?

Asking Questions

Humans are naturally curious beings. As you read actively, you should be asking questions about the topic you are reading. Don’t just say the questions in your mind; write them down. You may ask: Why is this topic important? What is the relevance of this topic currently? Was this topic important a long time ago but irrelevant now? Why did my professor assign this reading?

You need a place where you can actually write down these questions; a separate page in your notes is a good place to begin. If you are taking notes on your computer, start a new document and write down the questions. Leave some room to answer the questions when you begin and again after you read.

Inferring and Implying

When you read, you can take the information on the page and infer , or conclude responses to related challenges from evidence or from your own reasoning. A student will likely be able to infer what material the professor will include on an exam by taking good notes throughout the classes leading up to the test.

Writers may imply information without directly stating a fact for a variety of reasons. Sometimes a writer may not want to come out explicitly and state a bias, but may imply or hint at his or her preference for one political party or another. You have to read carefully to find implications because they are indirect, but watching for them will help you comprehend the whole meaning of a passage.

Learning Vocabulary

Vocabulary specific to certain disciplines helps practitioners in that field engage and communicate with each other. Few people beyond undertakers and archeologists likely use the term sarcophagus in everyday communications, but for those disciplines, it is a meaningful distinction. Looking at the example, you can use context clues to figure out the meaning of the term sarcophagus because it is something undertakers and/or archeologists would recognize. At the very least, you can guess that it has something to do with death. As a potential professional in the field you’re studying, you need to know the lingo. You may already have a system in place to learn discipline-specific vocabulary, so use what you know works for you. Two strong strategies are to look up words in a dictionary (online or hard copy) to ensure you have the exact meaning for your discipline and to keep a dedicated list of words you see often in your reading. You can list the words with a short definition so you have a quick reference guide to help you learn the vocabulary.

Intelligent people always question and evaluate. This doesn’t mean they don’t trust others; they just need verification of facts to understand a topic well. It doesn’t make sense to learn incomplete or incorrect information about a subject just because you didn’t take the time to evaluate all the sources at your disposal. When early explorers were afraid to sail the world for fear of falling off the edge, they weren’t stupid; they just didn’t have all the necessary data to evaluate the situation.

When you evaluate a text, you are seeking to understand the presented topic. Depending on how long the text is, you will perform a number of steps and repeat many of these steps to evaluate all the elements the author presents. When you evaluate a text, you need to do the following:

- Scan the title and all headings.

- Read through the entire passage fully.

- Question what main point the author is making.

- Decide who the audience is.

- Identify what evidence/support the author uses.

- Consider if the author presents a balanced perspective on the main point.

- Recognize if the author introduced any biases in the text.

When you go through a text looking for each of these elements, you need to go beyond just answering the surface question; for instance, the audience may be a specific field of scientists, but could anyone else understand the text with some explanation? Why would that be important?

Analysis Question

Think of an article you need to read for a class. Take the steps above on how to evaluate a text, and apply the steps to the article. When you accomplish the task in each step, ask yourself and take notes to answer the question: Why is this important? For example, when you read the title, does that give you any additional information that will help you comprehend the text? If the text were written for a different audience, what might the author need to change to accommodate that group? How does an author’s bias distort an argument? This deep evaluation allows you to fully understand the main ideas and place the text in context with other material on the same subject, with current events, and within the discipline.

When you learn something new, it always connects to other knowledge you already have. One challenge we have is applying new information. It may be interesting to know the distance to the moon, but how do we apply it to something we need to do? If your biology instructor asked you to list several challenges of colonizing Mars and you do not know much about that planet’s exploration, you may be able to use your knowledge of how far Earth is from the moon to apply it to the new task. You may have to read several other texts in addition to reading graphs and charts to find this information.

That was the challenge the early space explorers faced along with myriad unknowns before space travel was a more regular occurrence. They had to take what they already knew and could study and read about and apply it to an unknown situation. These explorers wrote down their challenges, failures, and successes, and now scientists read those texts as a part of the ever-growing body of text about space travel. Application is a sophisticated level of thinking that helps turn theory into practice and challenges into successes.

Preparing to Read for Specific Disciplines in College

Different disciplines in college may have specific expectations, but you can depend on all subjects asking you to read to some degree. In this college reading requirement, you can succeed by learning to read actively, researching the topic and author, and recognizing how your own preconceived notions affect your reading. Reading for college isn’t the same as reading for pleasure or even just reading to learn something on your own because you are casually interested.

In college courses, your instructor may ask you to read articles, chapters, books, or primary sources (those original documents about which we write and study, such as letters between historic figures or the Declaration of Independence). Your instructor may want you to have a general background on a topic before you dive into that subject in class, so that you know the history of a topic, can start thinking about it, and can engage in a class discussion with more than a passing knowledge of the issue.

If you are about to participate in an in-depth six-week consideration of the U.S. Constitution but have never read it or anything written about it, you will have a hard time looking at anything in detail or understanding how and why it is significant. As you can imagine, a great deal has been written about the Constitution by scholars and citizens since the late 1700s when it was first put to paper (that’s how they did it then). While the actual document isn’t that long (about 12–15 pages depending on how it is presented), learning the details on how it came about, who was involved, and why it was and still is a significant document would take a considerable amount of time to read and digest. So, how do you do it all? Especially when you may have an instructor who drops hints that you may also love to read a historic novel covering the same time period . . . in your spare time , not required, of course! It can be daunting, especially if you are taking more than one course that has time-consuming reading lists. With a few strategic techniques, you can manage it all, but know that you must have a plan and schedule your required reading so you are also able to pick up that recommended historic novel—it may give you an entirely new perspective on the issue.

Strategies for Reading in College Disciplines

No universal law exists for how much reading instructors and institutions expect college students to undertake for various disciplines. Suffice it to say, it’s a LOT.

For most students, it is the volume of reading that catches them most off guard when they begin their college careers. A full course load might require 10–15 hours of reading per week, some of that covering content that will be more difficult than the reading for other courses.

You cannot possibly read word-for-word every single document you need to read for all your classes. That doesn’t mean you give up or decide to only read for your favorite classes or concoct a scheme to read 17 percent for each class and see how that works for you. You need to learn to skim, annotate, and take notes. All of these techniques will help you comprehend more of what you read, which is why we read in the first place. We’ll talk more later about annotating and note-taking, but for now consider what you know about skimming as opposed to active reading.

Skimming is not just glancing over the words on a page (or screen) to see if any of it sticks. Effective skimming allows you to take in the major points of a passage without the need for a time-consuming reading session that involves your active use of notations and annotations. Often you will need to engage in that painstaking level of active reading, but skimming is the first step—not an alternative to deep reading. The fact remains that neither do you need to read everything nor could you possibly accomplish that given your limited time. So learn this valuable skill of skimming as an accompaniment to your overall study tool kit, and with practice and experience, you will fully understand how valuable it is.

When you skim, look for guides to your understanding: headings, definitions, pull quotes, tables, and context clues. Textbooks are often helpful for skimming—they may already have made some of these skimming guides in bold or a different color, and chapters often follow a predictable outline. Some even provide an overview and summary for sections or chapters. Use whatever you can get, but don’t stop there. In textbooks that have some reading guides, or especially in texts that do not, look for introductory words such as First or The purpose of this article . . . or summary words such as In conclusion . . . or Finally . These guides will help you read only those sentences or paragraphs that will give you the overall meaning or gist of a passage or book.

Now move to the meat of the passage. You want to take in the reading as a whole. For a book, look at the titles of each chapter if available. Read each chapter’s introductory paragraph and determine why the writer chose this particular order. Depending on what you’re reading, the chapters may be only informational, but often you’re looking for a specific argument. What position is the writer claiming? What support, counterarguments, and conclusions is the writer presenting?

Don’t think of skimming as a way to buzz through a boring reading assignment. It is a skill you should master so you can engage, at various levels, with all the reading you need to accomplish in college. End your skimming session with a few notes—terms to look up, questions you still have, and an overall summary. And recognize that you likely will return to that book or article for a more thorough reading if the material is useful.

Active Reading Strategies

Active reading differs significantly from skimming or reading for pleasure. You can think of active reading as a sort of conversation between you and the text (maybe between you and the author, but you don’t want to get the author’s personality too involved in this metaphor because that may skew your engagement with the text).

When you sit down to determine what your different classes expect you to read and you create a reading schedule to ensure you complete all the reading, think about when you should read the material strategically, not just how to get it all done . You should read textbook chapters and other reading assignments before you go into a lecture about that information. Don’t wait to see how the lecture goes before you read the material, or you may not understand the information in the lecture. Reading before class helps you put ideas together between your reading and the information you hear and discuss in class.

Different disciplines naturally have different types of texts, and you need to take this into account when you schedule your time for reading class material. For example, you may look at a poem for your world literature class and assume that it will not take you long to read because it is relatively short compared to the dense textbook you have for your economics class. But reading and understanding a poem can take a considerable amount of time when you realize you may need to stop numerous times to review the separate word meanings and how the words form images and connections throughout the poem.

The SQ3R Reading Strategy

You may have heard of the SQ3R method for active reading in your early education. This valuable technique is perfect for college reading. The title stands for S urvey, Q uestion, R ead, R ecite, R eview, and you can use the steps on virtually any assigned passage. Designed by Francis Pleasant Robinson in his 1961 book Effective Study, the active reading strategy gives readers a systematic way to work through any reading material.

Survey is similar to skimming. You look for clues to meaning by reading the titles, headings, introductions, summary, captions for graphics, and keywords. You can survey almost anything connected to the reading selection, including the copyright information, the date of the journal article, or the names and qualifications of the author(s). In this step, you decide what the general meaning is for the reading selection.

Question is your creation of questions to seek the main ideas, support, examples, and conclusions of the reading selection. Ask yourself these questions separately. Try to create valid questions about what you are about to read that have come into your mind as you engaged in the Survey step. Try turning the headings of the sections in the chapter into questions. Next, how does what you’re reading relate to you, your school, your community, and the world?

Read is when you actually read the passage. Try to find the answers to questions you developed in the previous step. Decide how much you are reading in chunks, either by paragraph for more complex readings or by section or even by an entire chapter. When you finish reading the selection, stop to make notes. Answer the questions by writing a note in the margin or other white space of the text.

You may also carefully underline or highlight text in addition to your notes. Use caution here that you don’t try to rush this step by haphazardly circling terms or the other extreme of underlining huge chunks of text. Don’t over-mark. You aren’t likely to remember what these cryptic marks mean later when you come back to use this active reading session to study. The text is the source of information—your marks and notes are just a way to organize and make sense of that information.

Recite means to speak out loud. By reciting, you are engaging other senses to remember the material—you read it (visual) and you said it (auditory). Stop reading momentarily in the step to answer your questions or clarify confusing sentences or paragraphs. You can recite a summary of what the text means to you. If you are not in a place where you can verbalize, such as a library or classroom, you can accomplish this step adequately by saying it in your head; however, to get the biggest bang for your buck, try to find a place where you can speak aloud. You may even want to try explaining the content to a friend.

Review is a recap. Go back over what you read and add more notes, ensuring you have captured the main points of the passage, identified the supporting evidence and examples, and understood the overall meaning. You may need to repeat some or all of the SQR3 steps during your review depending on the length and complexity of the material. Before you end your active reading session, write a short (no more than one page is optimal) summary of the text you read.

Reading Primary and Secondary Sources

Primary sources are original documents we study and from which we glean information; primary sources include letters, first editions of books, legal documents, and a variety of other texts. When scholars look at these documents to understand a period in history or a scientific challenge and then write about their findings, the scholar’s article is considered a secondary source. Readers have to keep several factors in mind when reading both primary and secondary sources.

Primary sources may contain dated material we now know is inaccurate. It may contain personal beliefs and biases the original writer didn’t intend to be openly published, and it may even present fanciful or creative ideas that do not support current knowledge. Readers can still gain great insight from primary sources, but readers need to understand the context from which the writer of the primary source wrote the text.

Likewise, secondary sources are inevitably another person’s perspective on the primary source, so a reader of secondary sources must also be aware of potential biases or preferences the secondary source writer inserts in the writing that may persuade an incautious reader to interpret the primary source in a particular manner.

For example, if you were to read a secondary source that is examining the U.S. Declaration of Independence (the primary source), you would have a much clearer idea of how the secondary source scholar presented the information from the primary source if you also read the Declaration for yourself instead of trusting the other writer’s interpretation. Most scholars are honest in writing secondary sources, but you as a reader of the source are trusting the writer to present a balanced perspective of the primary source. When possible, you should attempt to read a primary source in conjunction with the secondary source. The Internet helps immensely with this practice.

Researching Topic and Author

During your preview stage, sometimes called pre-reading, you can easily pick up on information from various sources that may help you understand the material you’re reading more fully or place it in context with other important works in the discipline. If your selection is a book, flip it over or turn to the back pages and look for an author’s biography or note from the author. See if the book itself contains any other information about the author or the subject matter.

The main things you need to recall from your reading in college are the topics covered and how the information fits into the discipline. You can find these parts throughout the textbook chapter in the form of headings in larger and bold font, summary lists, and important quotations pulled out of the narrative. Use these features as you read to help you determine what the most important ideas are.

Remember, many books use quotations about the book or author as testimonials in a marketing approach to sell more books, so these may not be the most reliable sources of unbiased opinions, but it’s a start. Sometimes you can find a list of other books the author has written near the front of a book. Do you recognize any of the other titles? Can you do an Internet search for the name of the book or author? Go beyond the search results that want you to buy the book and see if you can glean any other relevant information about the author or the reading selection. Beyond a standard Internet search, try the library article database. These are more relevant to academic disciplines and contain resources you typically will not find in a standard search engine. If you are unfamiliar with how to use the library database, ask a reference librarian on campus. They are often underused resources that can point you in the right direction.

Understanding Your Own Preset Ideas on a Topic

Consider this scenario: Laura really enjoys learning about environmental issues. She has read many books and watched numerous televised documentaries on this topic and actively seeks out additional information on the environment. While Laura’s interest can help her understand a new reading encounter about the environment, Laura also has to be aware that with this interest, she brings forward her preset ideas and biases about the topic. Sometimes these prejudices against other ideas relate to religion or nationality or even just tradition. Without evidence, thinking the way we always have is not a good enough reason; evidence can change, and at the very least it needs honest review and assessment to determine its validity. Ironically, we may not want to learn new ideas because that may mean we would have to give up old ideas we have already mastered, which can be a daunting prospect.

With every reading situation about the environment, Laura needs to remain open-minded about what she is about to read and pay careful attention if she begins to ignore certain parts of the text because of her preconceived notions. Learning new information can be very difficult if you balk at ideas that are different from what you’ve always thought. You may have to force yourself to listen to a different viewpoint multiple times to make sure you are not closing your mind to a viable solution your mindset does not currently allow.

Can you think of times you have struggled reading college content for a course? Which of these strategies might have helped you understand the content? Why do you think those strategies would work?

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/college-success-concise/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Amy Baldwin

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: College Success Concise

- Publication date: Apr 19, 2023

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/college-success-concise/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/college-success-concise/pages/3-3-effective-reading-strategies

© Sep 20, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

14 Activities That Increase Student Engagement During Reading Instruction

Research shows that students whose teachers spend too much time talking are less likely to be engaged during classroom instruction. Luckily, reading instruction can be so much more than lecture, reading practice, memorization, or decoding drills. We, as teachers, can do more to get our students engaged in learning to read.

List of Reading Activities

Here is a list of fourteen student engagement strategies from a webinar presented by Reading Horizons Chief Education Officer, Stacy Hurst, that you can use to increase student engagement during reading instruction or reading intervention:

1. Partner Pretest

Before teaching a new decoding skill or grammar rule, preface the lesson with a pretest. Let your students know that you will not score the test, lowering anxiety and increasing student performance. Pair students up for the pretest and have them use the same set of materials. If the pretest is on a computer or iPad, have students share the device between the two of them. During the pretest, walk around the room to gauge student needs and adjust the lesson accordingly. When lesson material matches student ability and understanding, engagement is higher. Make sure that the pretest is similar to the posttest so you can see how much your students retain during your lesson.

2. Stand Up/Sit Down

You can use this activity to help students learn to differentiate between similar but different reading concepts. For instance, when you’re trying to help your students understand the difference between common nouns and proper nouns, you can give examples of each and have students stand up if it is a common noun or sit down if it is a proper noun. This is a great way to see how much of your class is grasping the material while getting their blood flowing—helping them stay alert.

3. Thumbs Up/Thumbs Down

This activity provides a quick way to gauge if your students are comprehending a story or to test them on different reading skills. Instruct students to put their thumbs up if they agree with a statement or to put their thumbs down if they disagree. When students have a low energy level (i.e. right after lunch) Stand Up/Sit Down may be a better alternative. However, if you need to maintain your students’ current energy level Thumbs Up/Thumbs Down is ideal.

4. Secret Answer

This activity is great for students that might not be confident in their answers—students that look around the class when doing Stand Up/Sit Down or Thumbs Up/Thumbs Down to see how the other students’ answer before they answer themselves. To give students a secret way to answer, assign different responses a number and have students hold up the number of fingers that correspond to the answer they think is correct. To do this exercise properly, have your students place their hand near their heart (physically) with the appropriate number of fingers raised to indicate their answer. This way, especially if all the students are facing the teacher, it is difficult for students to copy their neighbor’s answer.

5. Response Cards

This is a great way to mix things up a bit. Have students create a stack of typical responses, including agree/disagree, true/false, yes/no, greater than/less than, multiple-choice options, and everyday emotions. After students have created their response cards, you can have them use them to respond in various settings. For example, while reading a book together as a class, you may pause and ask your students what they think the character is feeling right now. The students then select one of the everyday emotion cards from their personal stack of cards and lift it up to answer the question.

6. Think-Pair-Share

This activity allows students to pause and process what they have just learned. After reading a passage in a book, ask your class a question that they must first consider by themselves. After giving them time to think, have them discuss the question with their neighbor. Once they’ve discussed the question, invite students to share their answers with the class. By giving them this time to process, you enable them to be more engaged in their learning.

7. Quick Writes

Studies show that the proper ratio of direct instruction to reflection time for students is ten to two. That means that teachers need to provide students with two minutes of reflection for every ten minutes of instruction. This activity is a great way to give students that much-needed reflection time! In this activity, ask a question about a reading passage and have students write a response to share with a neighbor or the entire class.

8. One Word Splash

After reading a passage or learning new vocabulary terms, ask your students to write down one word that they feel sums up that material. This might seem overly simplistic, but it requires higher processing skills to help your students digest what they are reading. Students can do this with pencil/paper or a dry erase marker/personal whiteboard.

9. Quick Draw

This activity is perfect for visual learners or students who aren’t entirely writing yet. After reading a part of a story or learning a new concept or topic, have your students draw a picture about what they’ve just read or understood. For example, after reading part of the story Jack and the Beanstalk, have your students draw what has happened in the story up to that point. A student may draw a picture of a boy planting seeds with a beanstalk growing in the background.

10. Gallery Walk

To help students get some of their energy out, have them do a Gallery Walk to see their peers’ work. This activity is an excellent add-on to Quick Writes and Quick Draw. Because students seek approval from their peers, they will put more effort into their work when they know the class will view it.

11. A-Z Topic Summary

Help students connect the dots after finishing a book, a learning module, or a lesson. Have your students complete an A-Z Topic Summary either as individuals or in pairs. If it is an individual activity, have students write either a word or a sentence that connects to the book, module, or lesson for each letter of the alphabet. For example, if you learned about baking, they might write a sentence for the letter A such as: “Always preheat the oven before baking.” To speed up the activity, you can assign students to work in pairs or assign a letter to each student or team and have them write a sentence for that letter rather than the whole alphabet.

This is a quick way to help students process reading or lesson material when you’re pressed for time. First, have your students write three facts they learned from something they read or learned in class that day. Next, have students write two questions about the book or topic that wasn’t covered or discussed in class. Finally, have your students write one opinion they have about the reading material or lesson. This activity can also help you plan for the next lesson on the topic or book.

13. Find Your Match

This is another activity that gets your students up and moving. Create card matches that correlate to a storyline in a book, vocabulary terms, figures of speech, grammar rules, etc. For example, your card matches might include the following concepts (depending on grade level): rhyming words, uppercase/lowercase, antonyms/synonyms, words/definitions, problem/solution, and words/pictures. Hand out one card to each student in the class and then get up and find the other student with the matching card.

14. Dictation

One of our favorite teaching activities is Dictation! It is highly effective in engaging students because it is multisensory explicit phonics instruction involving: auditory, visual, kinesthetic, and tactile senses. Having a multisensory approach increases working memory and integrates all language skills/modalities. To do Dictation, have students listen to a word, repeat the word out loud, write it out on paper, and then have them read the word out loud again. View an example of Dictation in action here .

Subscribe to the podcast digest and never miss an episode!

We’ll send you summaries of every session, links for the resources discussed on each show (and some extra goodies) so that your learning never stops.

Do you love Literacy Talks?

Subscribe wherever you listen to your favorite Podcasts!

Join Our Community

We’re in this together. Join our community of educators and stay on top of professional learning opportunities, emerging research, and education trends!

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Professional Learning

- International

Quick Links

- Help Center

- Become a Literacy Leader

- Certified Facilitators

- PL Pay-Per-Seat Training

- Find Your Representative

Subscribe to our newsletter.

The latest news, articles, and resources, sent to your inbox.

© 2024 Reading Horizons. All rights reserved.

- You Need A Username And Password To Do This

- The Egyptian Underworld And Home Of Anubis

- Ridges Made By The Folding Of The Stomach Wall

- Public Commerce Square Or Shopping Mall

- Child's Toy Made By Bratz And Cabbage Patch

- Quickly, Landlady Of The Boar's Head Tavern

- Someone Skilled In Art, A Craftsperson

- Relates To The Penetrability Of A Rock By A Liquid

- Located, In A Specific Place

- Lean On Me Writer And Singer Bill

- Dedicated Outdoor Space For Kids To Have Fun

- Dubai's Airport Code

- Church Assembly For Debating Doctrines Of Faith

- Ash's Friend In Pokèmon, Master Of Rock Types

- Tart Like A Lemon

- Nigerian Singer, Won Grammy For Wait For U Collab

- John , Three's Company Star Died At Just 54

- To Remove The Packaging

- Search For Water With A Forked Stick

- Asks Someone To Prove Courage

- Planet Earth

- Under The Sea

- Culinary Arts

- Fauna And Flora

- Ancient Egypt

- Amusement Park

- Medieval Times

- Science Lab

- New York New York

- Popcorn Time

- La Bella Roma

- Department Store

- Fashion Show

- Welcome To Japan

- Concert Hall

- Home Sweet Home

- Cruise Ship

- Small World

- Train Travel

- Brazilian Tour

- Campsite Adventures

- Trip To Spain

- Fantasy World

- Performing Arts

- Space Exploration

- Student Life

- Mesopotamia

- Futuristic City

- Treasure Island

- Tracking Time

- House Of Horrors

- Architectural Styles

- Codycross' Spaceship

- Working From Home

- All Things Water

- Street Fair

- World Of Sounds

- Renaissance

- Botanical Garden

- Past And Present Tech

- Sense Of Smell

- Making A Documentary

- Professions

- African Grasslands

- Taking Care Of Our Planet

- Odd And Imaginary Creatures

- Deserts Of The World

- Babies And Toddlers

- Tundra And Taiga

- Time For A Check-Up

Bound Reading Assignment For The Classroom

Bound Reading Assignment For The Classroom Answers. Updated and verified solutions for all the levels of CodyCross Greece Group 674

Bound reading assignment for the classroom Answer

CodyCross Greece Group 674

CodyCross Greece Group 674 Answers

Join Now to View Premium Content

GradeSaver provides access to 2361 study guide PDFs and quizzes, 11008 literature essays, 2769 sample college application essays, 926 lesson plans, and ad-free surfing in this premium content, “Members Only” section of the site! Membership includes a 10% discount on all editing orders.

Prometheus Bound Lesson Plan

Reading assignment, questions, vocabulary.

Read lines 832-end.

Common Core Objectives

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.11-12.2 Determine two or more themes or central ideas of a text and analyze their development over the course of the text, including how they interact and build on one another to produce a complex account; provide an objective summary of the text.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.11-12.3 Analyze the impact of the author's choices regarding how to develop and relate elements of a story or drama (e.g., where a story is set, how the action is ordered, how the characters are introduced and developed).

Note that it is perfectly fine to expand any day’s work into two days depending on the characteristics of the class,...

Already a member? Log in

Prometheus Bound Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for Prometheus Bound is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

Example of Irony:

Prometheus stole fire from the gods and gave it to humanity, and ironically, the humans now use that gift to destroy him.

Example of Paradox:

Prometheus is bound and tied, he is captive, but his mind remains free. Oceanus and...

Prometheus bound

Prometheus Bound is a play by Aeschylus that portrays the rebellious nature of Prometheus, a Titan who defies the gods by giving fire to humanity and is punished for his actions. Throughout the play, Prometheus demonstrates his defiance and...

Gifts that Prometheus gave to humans

The prometheus gave fire to mankind a gift so precious and useful. Fire transformed the world of primitive men to reach for the stars. Technology and knowledge also a gift to mankind credited with the creation of humanity from clay. In Greek...

Study Guide for Prometheus Bound

Prometheus Bound study guide contains a biography of Aeschylus, literature essays, a complete e-text, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- About Prometheus Bound

- Prometheus Bound Summary

- Character List

- Lines 1-127 Summary and Analysis

Essays for Prometheus Bound

Prometheus Bound literature essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of Prometheus Bound.

- Themes Spawned from the Conflict between Prometheus and Zeus

- The Responsibility of Choice

- Suffering on Hope: Comparing Prometheus and Io

- Bondage in Frankenstein (Shelley) and ‘Prometheus Bound’ (Aeschylus)

Lesson Plan for Prometheus Bound

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to Prometheus Bound

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- Prometheus Bound Bibliography

E-Text of Prometheus Bound

Prometheus Bound e-text contains the full text of Prometheus Bound by Aeschylus.

- Argument and History

- List of Characters

- Text of Prometheus Bound

Wikipedia Entries for Prometheus Bound

- Introduction

- Textual styles

- Departures from Hesiod

- Prometheus Trilogy

- Grades 6-12

- School Leaders

NEW: Classroom Clean-Up/Set-Up Email Course! 🧽

Close Reading Strategies: A Step-by-Step Teaching Guide

Slow down, think, annotate, and reflect.

In the age of ChatGPT and other AI , using close reading strategies doesn’t come naturally to students. When students get a new assignment, their first instinct may be to race to the finish line rather than engage with text. This means students will miss a lot of nuance and meaning as they move through school.

On the other hand, a close reading of text requires students to slow down, think, annotate, and reflect. The ultimate idea? We get more information and enjoyment from reading and working with the text when we use close reading strategies.

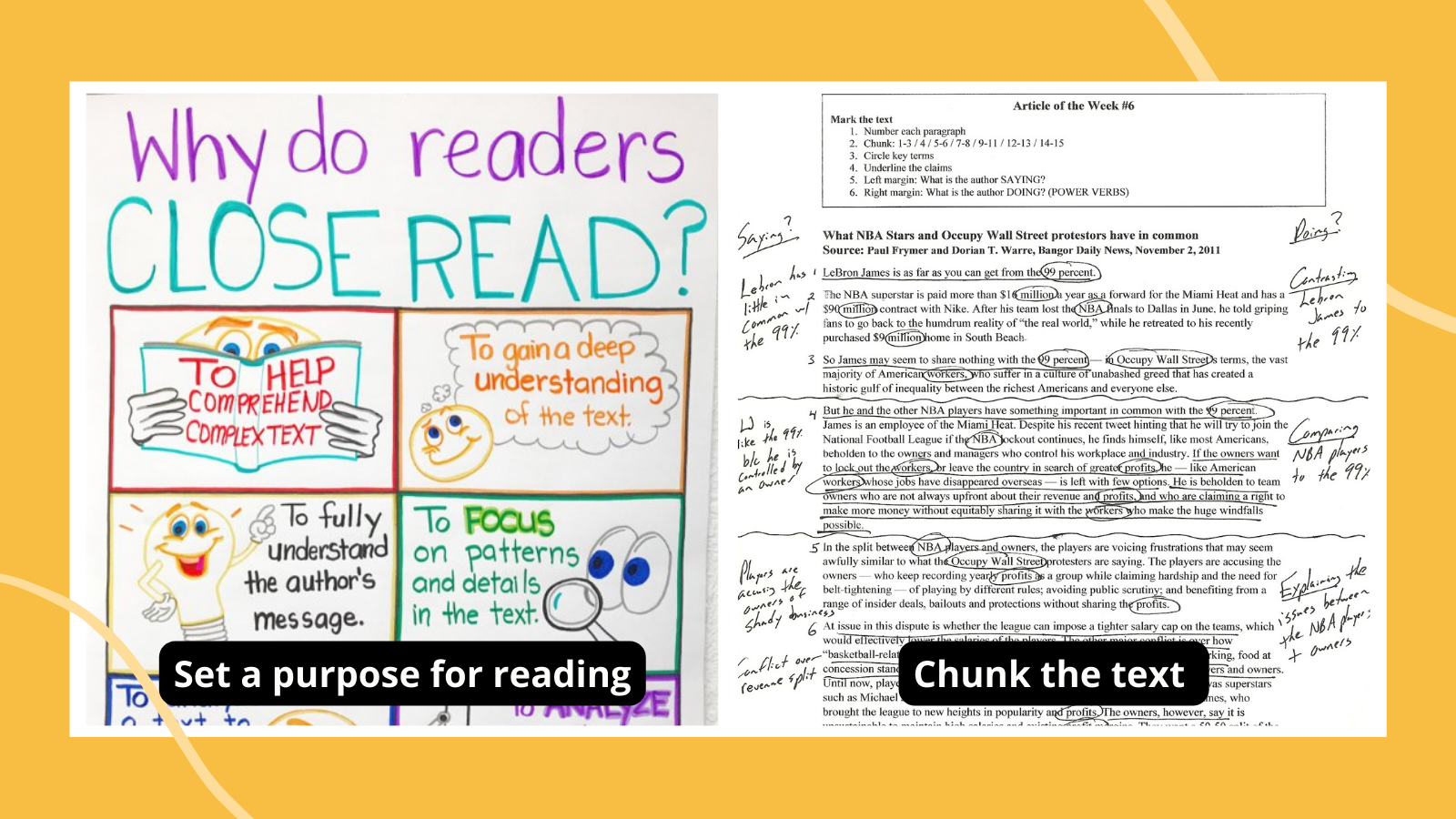

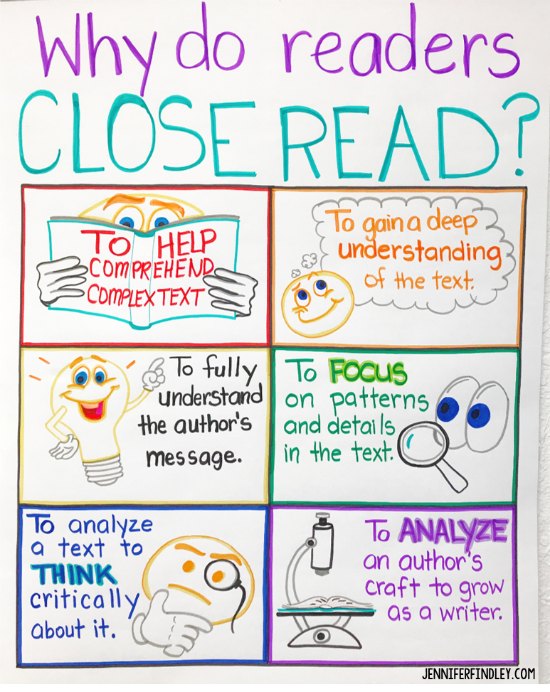

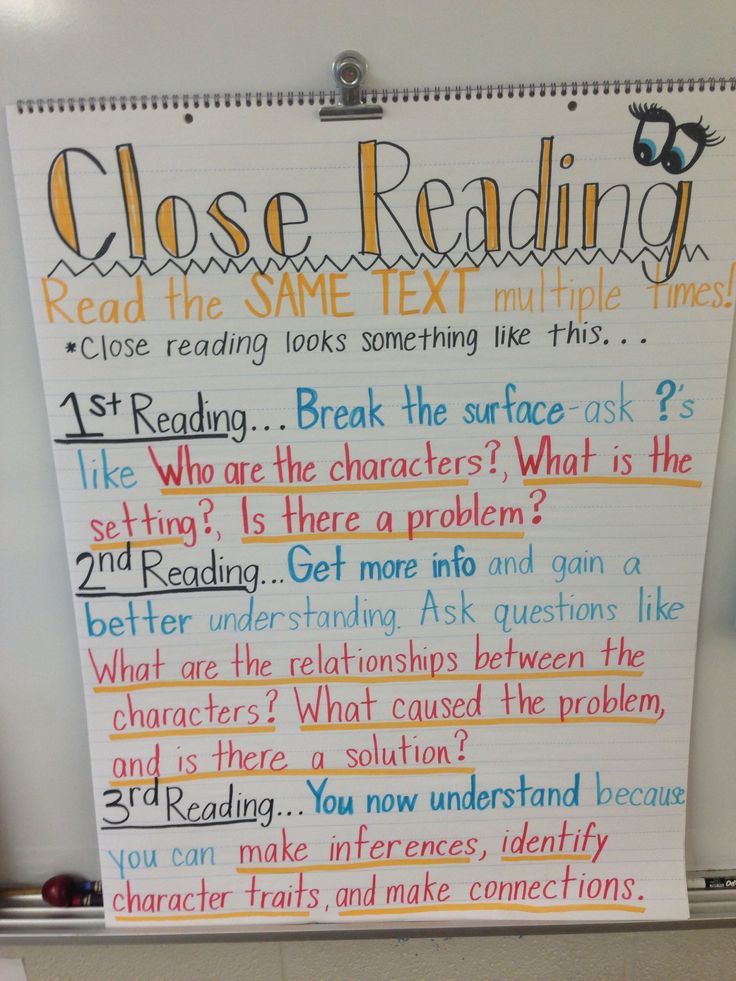

What is close reading?

Close reading is a way to read and work with text that moves beyond comprehension into interpretation and analysis. Put another way, close reading helps readers get from literal to inferential understanding of text.

After a close reading, students should understand what the text says and understand ideas embedded in the text, like a cultural perspective or religious opinion. They’ll also have an idea of what the text means to them, and what their opinion about it is based on more than just an offhand feeling. In class, close reading may take multiple class periods to complete and should have a goal at the end—a discussion or essay or some way for students to share what they’ve learned.

Read more: What is close reading anyway?

Here is our step-by-step guide with strategies for teaching close reading:

1. choose the perfect passage.

Image: Jennifer Findley

As you’re planning texts for a lesson or unit, start with what you want students to get out of what they’re reading. So, if you’re studying text structure, choose books or articles with interesting text structures. If you’re studying character development, find a passage that shows how a character changes or evolves. The point: There has to be something to find in text so that students aren’t grasping at straws.

Read more: How To Choose the Perfect Passage for Close Reading

Tip: Texts should be at or just above students’ grade and reading level, but they don’t have to be dense with text. Here’s how to use picture books in close reading lessons .

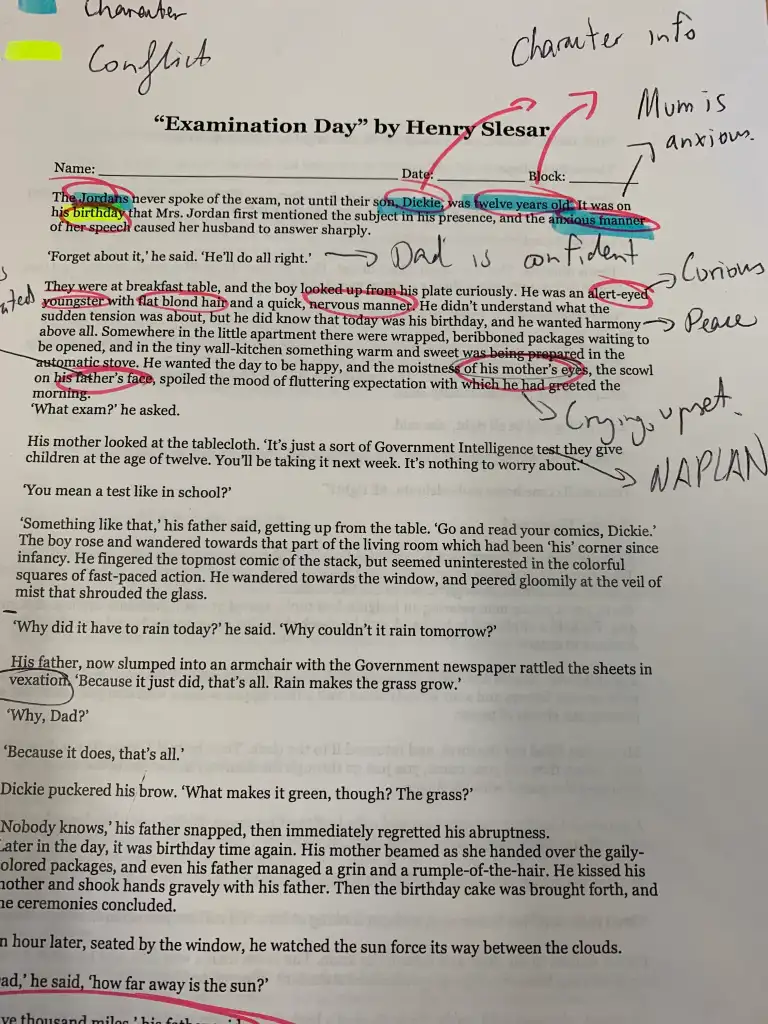

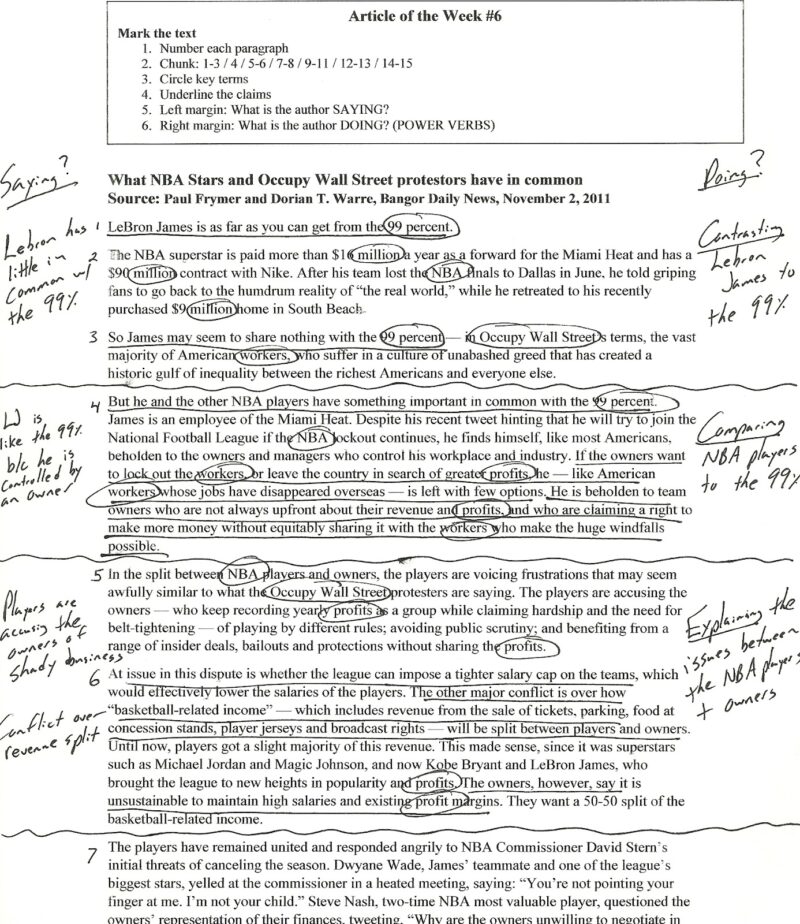

2. Prepare students by teaching annotation

Source: The English Classroom

Close reading will require some prep work. Students have to know how to annotate effectively, pulling out and making notes on the most important parts, i.e., not highlighting everything. Spend some time at the start of the year or unit teaching students how to identify and mark the most important parts of a text (new or key words, main ideas, pivotal plot points).

3. Students read the text for literal comprehension

First, have students read the entire text. The text should take less than one class period to read through once, so a chapter or article or even a few paragraphs could be enough. The first time students read, they’re reading for a general understanding and the main idea. They can think through:

- What is this story about?

- What information does this article contain?

- What is literally happening?

- What is the message or purpose?

4. Check in

After the first reading, check in with students to make sure they have a clear, literal understanding of the text. If they don’t, clear up misconceptions. If they do, move on to the second reading.

5. Chunk text in preparation for read 2

Image: iTeach. iCoach. iBlog.

Before the second reading, have students separate the text into paragraphs or chunks. Number each chunk. This way, when students review the text, they can easily refer back to paragraph 1 or chunk 2 and all be on the same page.

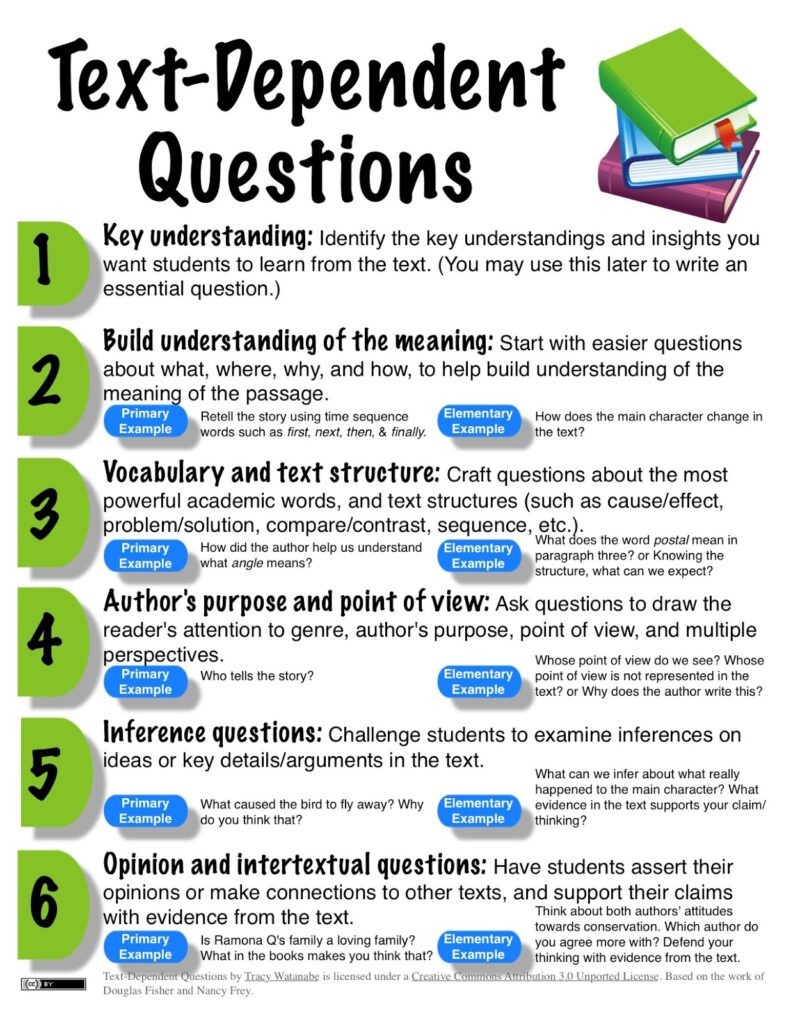

6. Work with text-dependent questions

Image: Instructional Coach

Now that students have a clear understanding of what the text is about, introduce the text-dependent questions that students will be working with in their close reading. Text-dependent questions are those that can only be answered using the text. For example, a question like “Why did Jeremiah eat a bullfrog?” rather than “Why is it not a good idea to eat a bullfrog?”

Questions that you work with should also range in their complexity. If the passage is more complex in terms of structure, content, or vocabulary, the questions may be less complex. But if a passage is easier for students to work with, the questions can be more advanced.

7. Set the end goal

Students shouldn’t be reading just to read. Explain the end goal—a Socratic seminar discussion, a partner discussion, an essay, a project. Once students know how they are going to respond to the questions, they’re better able to think through how they’re going to show what they know.

Here are creative ways to use close reading .

8. Time for reads 2 and 3

Image: Reading Ladies

Now that students have the question, the text, and the end goal, they’re ready to reread. The second time students read the text, they’re reading it to annotate for their own understanding. This is also the point where you’ll want to break students into groups—which students can work independently and which need some, or a lot of, support to complete the read?

Some texts will require a third reading for students to fully prepare, or students may need to reread chunks or paragraphs even more to get what they need. The important part is that students understand that rereading is an important part of close reading.

9. Respond to the text

This is it! The final close reading discussion. In this response, students will:

- Summarize what they read.

- Answer the text-dependent questions.

- Include evidence to support their ideas.

- Draw conclusions about the meaning of the text.

Have some way for students to plan out what they are going to say or write, and have them turn in their annotated reading so you can refer back to it if you’re confused about how they got from point A to Z.

10. Reflect

Every so often, reflect on how close reading is changing what students are taking away from what they read. Close reading should shape their reading skills and how they approach text beyond your class, but students may need support seeing the connection.

11. Level up

As students get more comfortable with close reading, you can level up their discussions by:

- Having students develop their own questions after they read a text or as you progress through a longer text.

- Using texts that are more complex in terms of content or structure.

- Challenging students to do a close reading of a picture book or graphic novel, rather than full-on text.

What strategies do you use to teach close reading in your classroom? Share in our WeAreTeachers HELPLINE group on Facebook.

Read why close reading can be the most fun lesson in your week ..

You Might Also Like

All the Best Kindergarten Classroom Management Tips and Ideas

Let's start at the very beginning. Continue Reading

Copyright © 2024. All rights reserved. 5335 Gate Parkway, Jacksonville, FL 32256

- Assignments , Motivating Students

Reading Assignments, Activities, and Approaches to Promote Learning

- By Maryellen Weimer

- June 1, 2017

A collection of resources on getting students to read what's assigned and strategies for developing college-level reading skills

Many students do not arrive in our courses with college-level reading skills. That usually ends up meaning a couple of things. First off, they don’t like to read and will challenge (usually quietly and covertly) teacher announcements and syllabus admonitions telling them they must do the reading. They’ll come to class, sit quietly, take a few notes, and see what happens if they aren’t prepared. If there are no negative consequences, they decide maybe they don’t have to do the reading or they can put it off until just before the exam. In the Relevant Research section below you’ll find a study that documents the number of students who come to class not having done the reading as well as what they say is the most effective tactic for encouraging them to read what’s assigned.

To continue reading, you must be a Teaching Professor Subscriber. Please log in or sign up for full access.

- Tags: college-level reading , getting students to read , reading assignments

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Related Articles

2718 Dryden Drive Madison, WI 53704 1-800-433-0499

Magna Publications © 2024 All rights reserved

Are you signed up for free weekly Teaching Professor updates?

You'll get notified of the newest articles..

June 7-9, 2024 • New Orleans

Connect with fellow educators at the teaching professor conference.

Top 3 Product Matches

Adventures of Tom Sawyer

Retail Price: $9.95 Our Price: $7.46 or less

Reproducible

Our Price: $19.95

Downloadable PDF File

Our Price: $14.95

- Prestwick House Blog

- Free Library

- Teaching Guides

- Grammar & Writing

Holding Students Accountable for Reading Assignments

- by Derek Spencer

It happens in classes across the country, whether in person, remotely, or in between.

Your students don't do the reading you assign—reading you assign because you want to actually teach them about what's going on in that part of the text. You don't want to waste valuable time creating daily tasks no one will complete or explaining to half the class what the reading was about, while the others are bored because they actually read the text.

As much as we wish every student would eagerly read the books assigned to them, we know that some students need a little extra push. The following are four techniques you can use to improve student accountability when it comes to reading assignments.

Set Clear Expectations from the Start

Take a look at your syllabus. Does it tell students, in no uncertain terms, what is expected from them? More specifically, does it lay out what it means to be ready for class?

Being ready for class involves more than just showing up (or logging in), and your students need to know that. Being ready for class means being prepared to tackle the topic du jour , whatever that may be. In cases when a reading is assigned for homework, students who come to class prepared to discuss the text are ready for class.

By having a clear set of expectations, you’re demonstrating that you believe in each student’s ability to do the work. Studies have shown that when teachers believe in them, students tend to achieve at higher levels. Setting expectations—and enforcing them—may give students a sense of responsibility and help motivate them to do their assignments.

Give Students Specific Reading Pointers

When you assign students their reading homework, you may want to prime them by telling them about key things they should look for in the text.

One way to do this is by telling them what the next class is going to focus on. Instead of saying, "Okay, read pages 78-90," say, "For homework, read pages 78-90. Tomorrow, we're going to discuss how the events in this chapter foreshadow a major change in Sarah's characterization."

Asking students to look for something specific in the text gives them a purpose for reading and can help them stay focused on the assignment. Plus, it gives you something to use during the next class to gauge whether they actually read the section.

Ask Students to Keep Reading Journals

A reading journal is a free-form type of diary in which students jot down their thoughts about the book they're reading. But it can be more than that, too. Students can use reading journals to:

- Speculate about upcoming plot points based on what's happened thus far in the text

- Write about their favorite characters and what makes them so awesome

- Ask questions they have about the text

- Write poems or lyrics about the book

- Draw scenes and characters

- Create charts linking characters and/or events

The only requirement of these reading journals is that each entry should be about the current reading. Otherwise, students should feel free to use their creativity to make something unique. If you decide to make these journals part of your students' grades, it's a good idea to grade only for completion and a good-faith effort to engage with the text.

Reading journals are also effective for keeping track of students’ progress during distance learning. Try asking your students to log their thoughts in a Google Doc or Word file, adding to it as they continue the book. Need inspiration? We have several free Google Docs literary journal templates you can adapt for your classes.

No matter the format, encourage students to truly make these journals their own. They might even find themselves having that elusive element they tend to associate with anything other than school: fun .

Do your students need more guidance when it comes to journaling? Take a look at our Response Journals . Each title-specific unit is filled with thought-provoking writing prompts that will encourage your students to reflect on the text and how it relates to their lives.

Have Students Complete RAFT Writing Prompts

RAFT stands for:

- Role of the writer

You can use the RAFT method to create writing prompts to use after each reading assignment. Perhaps you want your students to write a letter from Hamlet to Ophelia in which he apologizes for how he treated her and explains why he believes that what he's doing is necessary. The RAFT would look like this:

- F: Personal Letter

- T: Apology/Explanation for acting badly

Students would then use what they know about the characters and the plot to complete the writing prompt. Not only is this a good way to determine how well your students understand the text, but it's also a great way to get students to write in different genres and for different purposes.

If you’re looking for other ways to have students engage with the text, check out our Activity Packs . These title-specific guides contain plenty of literature-based activities and writing prompts that help students think critically about the text while learning about literary elements such as theme, symbolism, characterization, allusion, and more.

Having trouble holding students’ attention with long texts? Reading Literature has what you need. In each book, you’ll find a carefully-selected collection of famous short stories and poems appropriate for its corresponding grade level (9-12). Annotations throughout each text provide students with vocabulary word definitions, explanations of unfamiliar allusions, and interpretations of difficult passages, helping them better understand and appreciate the work.

Newsletter Signup

Information and Products

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Service

- Popular Searches

- Payment Information

- Grammar & Writing

- More Resources

- Order By Catalog Code

Customer Service

1.800.932.4593

Connect With Us

Copyright 2024 Prestwick House. All Rights Reserved.

Book Bound Classroom

- My Products (2)

- Ratings & Reviews

- Ask a Question

- Independent Work Packet

I am a 3rd year middle school teacher. all 3 years have been in ELA, specifically in 6th and 7th grade. I have taught in a co-tight setting all 3 years.

Yet to be added

I have a bachelors degree in middle school education, specifically for ELA and science.

4 th , 5 th , 6 th , 7 th , 8 th

English Language Arts , Reading , Writing

- We're hiring

- Help & FAQ

- Privacy policy

- Student privacy

- Terms of service

- Tell us what you think

Don't forget to check out my featured products!

Item added to your cart

How to spiral bind books for your classroom.

Let's face it - teachers LOVE being organized and there's nothing more that can bring a smile to a teacher's face than a freshly printed and binded book for their classroom! For years, I simply made mini packets for my students that I would staple. Although they did the job, I found myself repeating the process over and over again throughout the year.

Over the summer, I realized that Staples and other office supply stores bind for you. I excitedly went over and had a packet spiral bound. It turned out amazing but the sticker shock of the price was hard to swallow. At a little over $7.00 PER PACKET after taxes, I quickly realized this was not a financially feasible option for teachers on a budget.

I looked into many options online and read hundreds of review before I decided to take the plunge and order the following binding machine.

This machine is incredibly sturdy. Many of the other binding machines online are made out of plastic and do not hold up to long term usage, especially within a classroom setting. Because of its solid base, it makes it easier to make clear punches through the paper without it ripping in the process. It was very easy to put together right out of the box!

It came with over 100 accessories to start spiral binding your booklets. Both metal and plastic spiral binding was included. Most of the spiral binding included was meant for smaller booklets. So, if you plan to make smaller sectioned booklets this would be perfect as is.

When completed, the wire binding looks like this:

I did end up ordering some larger plastic spines to accommodate the year-long curriculum I was hoping to have for my students.

To start binding, you simply take a small section of paper and press down on the level. You will have perfectly sectioned punches on all your paper. I was able to punch over 100 pieces of paper in about two minutes.

This spiral binding machine will pay for itself after a handful of uses!

If you are ready to get one for your classroom, i have a discount code for you use the code 10wbmoff for an additional 10% off and free shipping to your house.

INTERESTED IN SOME YEAR LONG PACKETS TO BIND? CLICK THE PICTURES BELOW TO CHECK THEM OUT

Leave a comment

Please note, comments need to be approved before they are published.

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.

Welcome to Bound Brook School District

Summer Assignments ELA and MATH

Links attached:

- Bound Brook High School Summer Reading Info Graphic – English

- Bound Brook High School Summer Reading Info Graphic – Spanish

- Quantitative Reasoning 2022 Summer Assignment

- Summer Assignment 2022 Incoming Algebra 1 Honors

- Summer Assignment 2022 Incoming Algebra 1 CP

- Summer Assignment 2022 Incoming Algebra 2 Honors

- Summer Assignment 2022 Incoming Geometry Honors

- Summer Assignment 2022 Incoming Pre-Calculus Honors

- AP Statistics Assignments

- Congratulations to the Bound Brook School District’s Teachers and Specialists of the Year!

- Bound Brook High School students learn to fly drones, while earning college credits through Raritan Valley Community College

- Bound for the Future: A Look into the BBHS AVID Program

- Bound Brook School District’s tentative budget to expand programs and decrease taxes

Announcements

- NJDA SFSP NOTIFICATION TO THE COMMUNITY OPEN SITES

- New Covid Guidelines 4.2024

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Please find below the answer for Bound reading assignment for the classroom. CodyCross is one of the most popular games which is available for both iOS and Android. This crossword clue belongs to CodyCross Greece Group 674 Puzzle 5. The answer we have below for Bound reading assignment for the classroom has a total of 8 letters. HINTS AND TIPS:

Here are all the Bound reading assignment for the classroom answers. This question is part of the popular game CodyCross! This game has been developed by Fanatee Games, a very famous video game company. Since you are already here then chances are that you are stuck on a specific level and are looking for our help.

Thank you for visiting our website, which helps with the answers for the CodyCross game. With this website, you will not need any other help to pass difficult task or level. It helps you with CodyCross Bound reading assignment for the classroom answers, some additional solutions and useful tips and tricks.

Below are possible answers for the crossword clue Bound reading assignment for the classroom.In an effort to arrive at the correct answer, we have thoroughly scrutinized each option and taken into account all relevant information that could provide us with a clue as to which solution is the most accurate.

CodyCross Bound Reading Assignment For The Classroom Exact Answer for Greece Group 674 Puzzle 5.

Determining Reading Speed and Pacing. To determine your reading speed, select a section of text—passages in a textbook or pages in a novel. Time yourself reading that material for exactly 5 minutes, and note how much reading you accomplished in those 5 minutes. Multiply the amount of reading you accomplished in 5 minutes by 12 to determine ...

Stop and reread the sentences before and after the word. Think of a potential synonym for the new word. Plug that synonym in and see if it makes sense. If it makes sense, keep reading. If it does not make sense, either try again or try another vocabulary hack, like a dictionary or asking a peer. 8. Teach annotation.

Here is a list of fourteen student engagement strategies from a webinar presented by Reading Horizons Chief Education Officer, Stacy Hurst, that you can use to increase student engagement during reading instruction or reading intervention: 1. Partner Pretest. Before teaching a new decoding skill or grammar rule, preface the lesson with a ...

Bound Reading Assignment For The Classroom Answers. Updated and verified solutions for all the levels of CodyCross Greece Group 674. Answer. Bound reading assignment for the classroom Answer . T E X T B O O K. Symbolic Representation Used In Dance Or Chess. Young, Not Fully Mature . CodyCross Greece Group 674.

The Prometheus Bound lesson plan is designed to help teachers and educators plan classroom activities and instruction. ... Prometheus Bound Lesson Plan Reading Assignment, Questions, Vocabulary. Read lines 276-564. Common Core Objectives. 1. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.11-12.1

Watch. Watch our webcast Make Reading Count (opens in a new window), featuring literacy experts Isabel Beck, Nanci Bell, and Sharon Walpole. They discuss the essential components for developing good reading comprehension skills in young children, identify some of the potential stumbling blocks, and offer research-based comprehension strategies teachers can use in the classroom to teach all ...

The Prometheus Bound lesson plan is designed to help teachers and educators plan classroom activities and instruction. ... Prometheus Bound Lesson Plan Reading Assignment, Questions, Vocabulary. Read lines 832-end. Common Core Objectives. 1. CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.11-12.2

In the Classroom. Browse our library of evidence-based teaching strategies, learn more about using classroom texts, find out what whole-child literacy instruction looks like, and dive deeper into comprehension, content area literacy, writing, and social-emotional learning. ... Having context-bound and vague knowledge of the word's meaning ...

Here's how to use picture books in close reading lessons. 2. Prepare students by teaching annotation. Source: The English Classroom. Close reading will require some prep work. Students have to know how to annotate effectively, pulling out and making notes on the most important parts, i.e., not highlighting everything.

Without good reading skills, students often resort to dubious approaches when tackling their reading assignments. With brightly colored markers, they underline entire paragraphs, if not whole pages. They attempt the reading while attending to numerous distractions; TV, music, and electronic devices of various sorts.

Give Students Specific Reading Pointers. When you assign students their reading homework, you may want to prime them by telling them about key things they should look for in the text. One way to do this is by telling them what the next class is going to focus on. Instead of saying, "Okay, read pages 78-90," say, "For homework, read pages 78-90.

This is an independent reading/ choice reading accountability assignment I have created for my middle school classroom. Each student gets one each week and are required to fill this in at least 3 times that they . Subjects: English Language Arts, Reading, Writing ... Ask Book Bound Classroom a question. They will receive an automated email and ...

CommonLit is a comprehensive literacy program with thousands of reading lessons, full-year ELA curriculum, benchmark assessments, and standards-based data for teachers. Get started for free. for teachers, students, & families. Explore school services.

Adapted from: P. Kluth & Chandler-Olcott, K. (2007). "A land we can share": Teaching literacy to students with autism.. The read aloud helps teachers build and experience a sense of community in the classroom, provides common ground for discussion, entertains, requires little formal student response (giving all learners a time to feel confident and competent), and connects the group to ...

To start binding, you simply take a small section of paper and press down on the level. You will have perfectly sectioned punches on all your paper. I was able to punch over 100 pieces of paper in about two minutes. Once all the pages have been punched, you can either feed the metal wire spine (included) into the holes and punch done to create ...

Studies do find small group instruction to offer some benefits, at least under certain circumstances (Lou, et al., 1996). For instance, small group math instruction seems to deliver positive benefits — both larger and more consistent learning payoffs than in reading. Reading studies often report that the amount of small group instruction ...

Once you join, you will be able to access your summer reading assignment for Bound Brook students grades 7-12. If you are a High School Honors, RVCC, or AP student, summer reading is required. If you are a middle school or high school college prep student, summer reading is optional, but comes with rewards and prizes.