- Privacy Policy

Home » Descriptive Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Descriptive Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Table of Contents

Descriptive Research Design

Definition:

Descriptive research design is a type of research methodology that aims to describe or document the characteristics, behaviors, attitudes, opinions, or perceptions of a group or population being studied.

Descriptive research design does not attempt to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables or make predictions about future outcomes. Instead, it focuses on providing a detailed and accurate representation of the data collected, which can be useful for generating hypotheses, exploring trends, and identifying patterns in the data.

Types of Descriptive Research Design

Types of Descriptive Research Design are as follows:

Cross-sectional Study

This involves collecting data at a single point in time from a sample or population to describe their characteristics or behaviors. For example, a researcher may conduct a cross-sectional study to investigate the prevalence of certain health conditions among a population, or to describe the attitudes and beliefs of a particular group.

Longitudinal Study

This involves collecting data over an extended period of time, often through repeated observations or surveys of the same group or population. Longitudinal studies can be used to track changes in attitudes, behaviors, or outcomes over time, or to investigate the effects of interventions or treatments.

This involves an in-depth examination of a single individual, group, or situation to gain a detailed understanding of its characteristics or dynamics. Case studies are often used in psychology, sociology, and business to explore complex phenomena or to generate hypotheses for further research.

Survey Research

This involves collecting data from a sample or population through standardized questionnaires or interviews. Surveys can be used to describe attitudes, opinions, behaviors, or demographic characteristics of a group, and can be conducted in person, by phone, or online.

Observational Research

This involves observing and documenting the behavior or interactions of individuals or groups in a natural or controlled setting. Observational studies can be used to describe social, cultural, or environmental phenomena, or to investigate the effects of interventions or treatments.

Correlational Research

This involves examining the relationships between two or more variables to describe their patterns or associations. Correlational studies can be used to identify potential causal relationships or to explore the strength and direction of relationships between variables.

Data Analysis Methods

Descriptive research design data analysis methods depend on the type of data collected and the research question being addressed. Here are some common methods of data analysis for descriptive research:

Descriptive Statistics

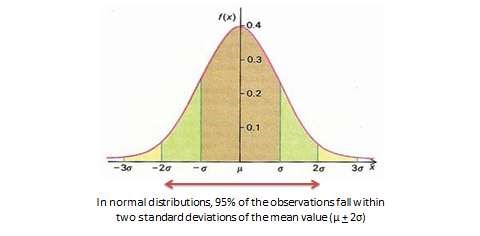

This method involves analyzing data to summarize and describe the key features of a sample or population. Descriptive statistics can include measures of central tendency (e.g., mean, median, mode) and measures of variability (e.g., range, standard deviation).

Cross-tabulation

This method involves analyzing data by creating a table that shows the frequency of two or more variables together. Cross-tabulation can help identify patterns or relationships between variables.

Content Analysis

This method involves analyzing qualitative data (e.g., text, images, audio) to identify themes, patterns, or trends. Content analysis can be used to describe the characteristics of a sample or population, or to identify factors that influence attitudes or behaviors.

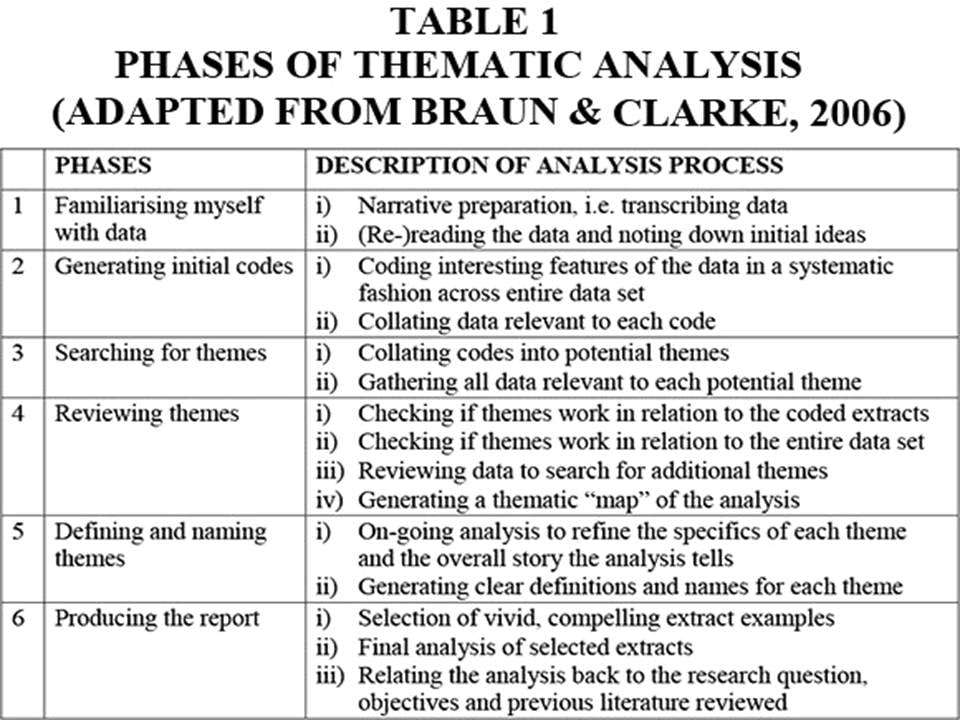

Qualitative Coding

This method involves analyzing qualitative data by assigning codes to segments of data based on their meaning or content. Qualitative coding can be used to identify common themes, patterns, or categories within the data.

Visualization

This method involves creating graphs or charts to represent data visually. Visualization can help identify patterns or relationships between variables and make it easier to communicate findings to others.

Comparative Analysis

This method involves comparing data across different groups or time periods to identify similarities and differences. Comparative analysis can help describe changes in attitudes or behaviors over time or differences between subgroups within a population.

Applications of Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design has numerous applications in various fields. Some of the common applications of descriptive research design are:

- Market research: Descriptive research design is widely used in market research to understand consumer preferences, behavior, and attitudes. This helps companies to develop new products and services, improve marketing strategies, and increase customer satisfaction.

- Health research: Descriptive research design is used in health research to describe the prevalence and distribution of a disease or health condition in a population. This helps healthcare providers to develop prevention and treatment strategies.

- Educational research: Descriptive research design is used in educational research to describe the performance of students, schools, or educational programs. This helps educators to improve teaching methods and develop effective educational programs.

- Social science research: Descriptive research design is used in social science research to describe social phenomena such as cultural norms, values, and beliefs. This helps researchers to understand social behavior and develop effective policies.

- Public opinion research: Descriptive research design is used in public opinion research to understand the opinions and attitudes of the general public on various issues. This helps policymakers to develop effective policies that are aligned with public opinion.

- Environmental research: Descriptive research design is used in environmental research to describe the environmental conditions of a particular region or ecosystem. This helps policymakers and environmentalists to develop effective conservation and preservation strategies.

Descriptive Research Design Examples

Here are some real-time examples of descriptive research designs:

- A restaurant chain wants to understand the demographics and attitudes of its customers. They conduct a survey asking customers about their age, gender, income, frequency of visits, favorite menu items, and overall satisfaction. The survey data is analyzed using descriptive statistics and cross-tabulation to describe the characteristics of their customer base.

- A medical researcher wants to describe the prevalence and risk factors of a particular disease in a population. They conduct a cross-sectional study in which they collect data from a sample of individuals using a standardized questionnaire. The data is analyzed using descriptive statistics and cross-tabulation to identify patterns in the prevalence and risk factors of the disease.

- An education researcher wants to describe the learning outcomes of students in a particular school district. They collect test scores from a representative sample of students in the district and use descriptive statistics to calculate the mean, median, and standard deviation of the scores. They also create visualizations such as histograms and box plots to show the distribution of scores.

- A marketing team wants to understand the attitudes and behaviors of consumers towards a new product. They conduct a series of focus groups and use qualitative coding to identify common themes and patterns in the data. They also create visualizations such as word clouds to show the most frequently mentioned topics.

- An environmental scientist wants to describe the biodiversity of a particular ecosystem. They conduct an observational study in which they collect data on the species and abundance of plants and animals in the ecosystem. The data is analyzed using descriptive statistics to describe the diversity and richness of the ecosystem.

How to Conduct Descriptive Research Design

To conduct a descriptive research design, you can follow these general steps:

- Define your research question: Clearly define the research question or problem that you want to address. Your research question should be specific and focused to guide your data collection and analysis.

- Choose your research method: Select the most appropriate research method for your research question. As discussed earlier, common research methods for descriptive research include surveys, case studies, observational studies, cross-sectional studies, and longitudinal studies.

- Design your study: Plan the details of your study, including the sampling strategy, data collection methods, and data analysis plan. Determine the sample size and sampling method, decide on the data collection tools (such as questionnaires, interviews, or observations), and outline your data analysis plan.

- Collect data: Collect data from your sample or population using the data collection tools you have chosen. Ensure that you follow ethical guidelines for research and obtain informed consent from participants.

- Analyze data: Use appropriate statistical or qualitative analysis methods to analyze your data. As discussed earlier, common data analysis methods for descriptive research include descriptive statistics, cross-tabulation, content analysis, qualitative coding, visualization, and comparative analysis.

- I nterpret results: Interpret your findings in light of your research question and objectives. Identify patterns, trends, and relationships in the data, and describe the characteristics of your sample or population.

- Draw conclusions and report results: Draw conclusions based on your analysis and interpretation of the data. Report your results in a clear and concise manner, using appropriate tables, graphs, or figures to present your findings. Ensure that your report follows accepted research standards and guidelines.

When to Use Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design is used in situations where the researcher wants to describe a population or phenomenon in detail. It is used to gather information about the current status or condition of a group or phenomenon without making any causal inferences. Descriptive research design is useful in the following situations:

- Exploratory research: Descriptive research design is often used in exploratory research to gain an initial understanding of a phenomenon or population.

- Identifying trends: Descriptive research design can be used to identify trends or patterns in a population, such as changes in consumer behavior or attitudes over time.

- Market research: Descriptive research design is commonly used in market research to understand consumer preferences, behavior, and attitudes.

- Health research: Descriptive research design is useful in health research to describe the prevalence and distribution of a disease or health condition in a population.

- Social science research: Descriptive research design is used in social science research to describe social phenomena such as cultural norms, values, and beliefs.

- Educational research: Descriptive research design is used in educational research to describe the performance of students, schools, or educational programs.

Purpose of Descriptive Research Design

The main purpose of descriptive research design is to describe and measure the characteristics of a population or phenomenon in a systematic and objective manner. It involves collecting data that describe the current status or condition of the population or phenomenon of interest, without manipulating or altering any variables.

The purpose of descriptive research design can be summarized as follows:

- To provide an accurate description of a population or phenomenon: Descriptive research design aims to provide a comprehensive and accurate description of a population or phenomenon of interest. This can help researchers to develop a better understanding of the characteristics of the population or phenomenon.

- To identify trends and patterns: Descriptive research design can help researchers to identify trends and patterns in the data, such as changes in behavior or attitudes over time. This can be useful for making predictions and developing strategies.

- To generate hypotheses: Descriptive research design can be used to generate hypotheses or research questions that can be tested in future studies. For example, if a descriptive study finds a correlation between two variables, this could lead to the development of a hypothesis about the causal relationship between the variables.

- To establish a baseline: Descriptive research design can establish a baseline or starting point for future research. This can be useful for comparing data from different time periods or populations.

Characteristics of Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design has several key characteristics that distinguish it from other research designs. Some of the main characteristics of descriptive research design are:

- Objective : Descriptive research design is objective in nature, which means that it focuses on collecting factual and accurate data without any personal bias. The researcher aims to report the data objectively without any personal interpretation.

- Non-experimental: Descriptive research design is non-experimental, which means that the researcher does not manipulate any variables. The researcher simply observes and records the behavior or characteristics of the population or phenomenon of interest.

- Quantitative : Descriptive research design is quantitative in nature, which means that it involves collecting numerical data that can be analyzed using statistical techniques. This helps to provide a more precise and accurate description of the population or phenomenon.

- Cross-sectional: Descriptive research design is often cross-sectional, which means that the data is collected at a single point in time. This can be useful for understanding the current state of the population or phenomenon, but it may not provide information about changes over time.

- Large sample size: Descriptive research design typically involves a large sample size, which helps to ensure that the data is representative of the population of interest. A large sample size also helps to increase the reliability and validity of the data.

- Systematic and structured: Descriptive research design involves a systematic and structured approach to data collection, which helps to ensure that the data is accurate and reliable. This involves using standardized procedures for data collection, such as surveys, questionnaires, or observation checklists.

Advantages of Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design has several advantages that make it a popular choice for researchers. Some of the main advantages of descriptive research design are:

- Provides an accurate description: Descriptive research design is focused on accurately describing the characteristics of a population or phenomenon. This can help researchers to develop a better understanding of the subject of interest.

- Easy to conduct: Descriptive research design is relatively easy to conduct and requires minimal resources compared to other research designs. It can be conducted quickly and efficiently, and data can be collected through surveys, questionnaires, or observations.

- Useful for generating hypotheses: Descriptive research design can be used to generate hypotheses or research questions that can be tested in future studies. For example, if a descriptive study finds a correlation between two variables, this could lead to the development of a hypothesis about the causal relationship between the variables.

- Large sample size : Descriptive research design typically involves a large sample size, which helps to ensure that the data is representative of the population of interest. A large sample size also helps to increase the reliability and validity of the data.

- Can be used to monitor changes : Descriptive research design can be used to monitor changes over time in a population or phenomenon. This can be useful for identifying trends and patterns, and for making predictions about future behavior or attitudes.

- Can be used in a variety of fields : Descriptive research design can be used in a variety of fields, including social sciences, healthcare, business, and education.

Limitation of Descriptive Research Design

Descriptive research design also has some limitations that researchers should consider before using this design. Some of the main limitations of descriptive research design are:

- Cannot establish cause and effect: Descriptive research design cannot establish cause and effect relationships between variables. It only provides a description of the characteristics of the population or phenomenon of interest.

- Limited generalizability: The results of a descriptive study may not be generalizable to other populations or situations. This is because descriptive research design often involves a specific sample or situation, which may not be representative of the broader population.

- Potential for bias: Descriptive research design can be subject to bias, particularly if the researcher is not objective in their data collection or interpretation. This can lead to inaccurate or incomplete descriptions of the population or phenomenon of interest.

- Limited depth: Descriptive research design may provide a superficial description of the population or phenomenon of interest. It does not delve into the underlying causes or mechanisms behind the observed behavior or characteristics.

- Limited utility for theory development: Descriptive research design may not be useful for developing theories about the relationship between variables. It only provides a description of the variables themselves.

- Relies on self-report data: Descriptive research design often relies on self-report data, such as surveys or questionnaires. This type of data may be subject to biases, such as social desirability bias or recall bias.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Questionnaire – Definition, Types, and Examples

Case Study – Methods, Examples and Guide

Observational Research – Methods and Guide

Quantitative Research – Methods, Types and...

Qualitative Research Methods

Explanatory Research – Types, Methods, Guide

- What is descriptive research?

Last updated

5 February 2023

Reviewed by

Cathy Heath

Descriptive research is a common investigatory model used by researchers in various fields, including social sciences, linguistics, and academia.

Read on to understand the characteristics of descriptive research and explore its underlying techniques, processes, and procedures.

Analyze your descriptive research

Dovetail streamlines analysis to help you uncover and share actionable insights

Descriptive research is an exploratory research method. It enables researchers to precisely and methodically describe a population, circumstance, or phenomenon.

As the name suggests, descriptive research describes the characteristics of the group, situation, or phenomenon being studied without manipulating variables or testing hypotheses . This can be reported using surveys , observational studies, and case studies. You can use both quantitative and qualitative methods to compile the data.

Besides making observations and then comparing and analyzing them, descriptive studies often develop knowledge concepts and provide solutions to critical issues. It always aims to answer how the event occurred, when it occurred, where it occurred, and what the problem or phenomenon is.

- Characteristics of descriptive research

The following are some of the characteristics of descriptive research:

Quantitativeness

Descriptive research can be quantitative as it gathers quantifiable data to statistically analyze a population sample. These numbers can show patterns, connections, and trends over time and can be discovered using surveys, polls, and experiments.

Qualitativeness

Descriptive research can also be qualitative. It gives meaning and context to the numbers supplied by quantitative descriptive research .

Researchers can use tools like interviews, focus groups, and ethnographic studies to illustrate why things are what they are and help characterize the research problem. This is because it’s more explanatory than exploratory or experimental research.

Uncontrolled variables

Descriptive research differs from experimental research in that researchers cannot manipulate the variables. They are recognized, scrutinized, and quantified instead. This is one of its most prominent features.

Cross-sectional studies

Descriptive research is a cross-sectional study because it examines several areas of the same group. It involves obtaining data on multiple variables at the personal level during a certain period. It’s helpful when trying to understand a larger community’s habits or preferences.

Carried out in a natural environment

Descriptive studies are usually carried out in the participants’ everyday environment, which allows researchers to avoid influencing responders by collecting data in a natural setting. You can use online surveys or survey questions to collect data or observe.

Basis for further research

You can further dissect descriptive research’s outcomes and use them for different types of investigation. The outcomes also serve as a foundation for subsequent investigations and can guide future studies. For example, you can use the data obtained in descriptive research to help determine future research designs.

- Descriptive research methods

There are three basic approaches for gathering data in descriptive research: observational, case study, and survey.

You can use surveys to gather data in descriptive research. This involves gathering information from many people using a questionnaire and interview .

Surveys remain the dominant research tool for descriptive research design. Researchers can conduct various investigations and collect multiple types of data (quantitative and qualitative) using surveys with diverse designs.

You can conduct surveys over the phone, online, or in person. Your survey might be a brief interview or conversation with a set of prepared questions intended to obtain quick information from the primary source.

Observation

This descriptive research method involves observing and gathering data on a population or phenomena without manipulating variables. It is employed in psychology, market research , and other social science studies to track and understand human behavior.

Observation is an essential component of descriptive research. It entails gathering data and analyzing it to see whether there is a relationship between the two variables in the study. This strategy usually allows for both qualitative and quantitative data analysis.

Case studies

A case study can outline a specific topic’s traits. The topic might be a person, group, event, or organization.

It involves using a subset of a larger group as a sample to characterize the features of that larger group.

You can generalize knowledge gained from studying a case study to benefit a broader audience.

This approach entails carefully examining a particular group, person, or event over time. You can learn something new about the study topic by using a small group to better understand the dynamics of the entire group.

- Types of descriptive research

There are several types of descriptive study. The most well-known include cross-sectional studies, census surveys, sample surveys, case reports, and comparison studies.

Case reports and case series

In the healthcare and medical fields, a case report is used to explain a patient’s circumstances when suffering from an uncommon illness or displaying certain symptoms. Case reports and case series are both collections of related cases. They have aided the advancement of medical knowledge on countless occasions.

The normative component is an addition to the descriptive survey. In the descriptive–normative survey, you compare the study’s results to the norm.

Descriptive survey

This descriptive type of research employs surveys to collect information on various topics. This data aims to determine the degree to which certain conditions may be attained.

You can extrapolate or generalize the information you obtain from sample surveys to the larger group being researched.

Correlative survey

Correlative surveys help establish if there is a positive, negative, or neutral connection between two variables.

Performing census surveys involves gathering relevant data on several aspects of a given population. These units include individuals, families, organizations, objects, characteristics, and properties.

During descriptive research, you gather different degrees of interest over time from a specific population. Cross-sectional studies provide a glimpse of a phenomenon’s prevalence and features in a population. There are no ethical challenges with them and they are quite simple and inexpensive to carry out.

Comparative studies

These surveys compare the two subjects’ conditions or characteristics. The subjects may include research variables, organizations, plans, and people.

Comparison points, assumption of similarities, and criteria of comparison are three important variables that affect how well and accurately comparative studies are conducted.

For instance, descriptive research can help determine how many CEOs hold a bachelor’s degree and what proportion of low-income households receive government help.

- Pros and cons

The primary advantage of descriptive research designs is that researchers can create a reliable and beneficial database for additional study. To conduct any inquiry, you need access to reliable information sources that can give you a firm understanding of a situation.

Quantitative studies are time- and resource-intensive, so knowing the hypotheses viable for testing is crucial. The basic overview of descriptive research provides helpful hints as to which variables are worth quantitatively examining. This is why it’s employed as a precursor to quantitative research designs.

Some experts view this research as untrustworthy and unscientific. However, there is no way to assess the findings because you don’t manipulate any variables statistically.

Cause-and-effect correlations also can’t be established through descriptive investigations. Additionally, observational study findings cannot be replicated, which prevents a review of the findings and their replication.

The absence of statistical and in-depth analysis and the rather superficial character of the investigative procedure are drawbacks of this research approach.

- Descriptive research examples and applications

Several descriptive research examples are emphasized based on their types, purposes, and applications. Research questions often begin with “What is …” These studies help find solutions to practical issues in social science, physical science, and education.

Here are some examples and applications of descriptive research:

Determining consumer perception and behavior

Organizations use descriptive research designs to determine how various demographic groups react to a certain product or service.

For example, a business looking to sell to its target market should research the market’s behavior first. When researching human behavior in response to a cause or event, the researcher pays attention to the traits, actions, and responses before drawing a conclusion.

Scientific classification

Scientific descriptive research enables the classification of organisms and their traits and constituents.

Measuring data trends

A descriptive study design’s statistical capabilities allow researchers to track data trends over time. It’s frequently used to determine the study target’s current circumstances and underlying patterns.

Conduct comparison

Organizations can use a descriptive research approach to learn how various demographics react to a certain product or service. For example, you can study how the target market responds to a competitor’s product and use that information to infer their behavior.

- Bottom line

A descriptive research design is suitable for exploring certain topics and serving as a prelude to larger quantitative investigations. It provides a comprehensive understanding of the “what” of the group or thing you’re investigating.

This research type acts as the cornerstone of other research methodologies . It is distinctive because it can use quantitative and qualitative research approaches at the same time.

What is descriptive research design?

Descriptive research design aims to systematically obtain information to describe a phenomenon, situation, or population. More specifically, it helps answer the what, when, where, and how questions regarding the research problem rather than the why.

How does descriptive research compare to qualitative research?

Despite certain parallels, descriptive research concentrates on describing phenomena, while qualitative research aims to understand people better.

How do you analyze descriptive research data?

Data analysis involves using various methodologies, enabling the researcher to evaluate and provide results regarding validity and reliability.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 11 January 2024

Last updated: 15 January 2024

Last updated: 17 January 2024

Last updated: 12 May 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 18 May 2023

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next.

Users report unexpectedly high data usage, especially during streaming sessions.

Users find it hard to navigate from the home page to relevant playlists in the app.

It would be great to have a sleep timer feature, especially for bedtime listening.

I need better filters to find the songs or artists I’m looking for.

Log in or sign up

Get started for free

Bridging the Gap: Overcome these 7 flaws in descriptive research design

Descriptive research design is a powerful tool used by scientists and researchers to gather information about a particular group or phenomenon. This type of research provides a detailed and accurate picture of the characteristics and behaviors of a particular population or subject. By observing and collecting data on a given topic, descriptive research helps researchers gain a deeper understanding of a specific issue and provides valuable insights that can inform future studies.

In this blog, we will explore the definition, characteristics, and common flaws in descriptive research design, and provide tips on how to avoid these pitfalls to produce high-quality results. Whether you are a seasoned researcher or a student just starting, understanding the fundamentals of descriptive research design is essential to conducting successful scientific studies.

Table of Contents

What Is Descriptive Research Design?

The descriptive research design involves observing and collecting data on a given topic without attempting to infer cause-and-effect relationships. The goal of descriptive research is to provide a comprehensive and accurate picture of the population or phenomenon being studied and to describe the relationships, patterns, and trends that exist within the data.

Descriptive research methods can include surveys, observational studies , and case studies, and the data collected can be qualitative or quantitative . The findings from descriptive research provide valuable insights and inform future research, but do not establish cause-and-effect relationships.

Importance of Descriptive Research in Scientific Studies

1. understanding of a population or phenomenon.

Descriptive research provides a comprehensive picture of the characteristics and behaviors of a particular population or phenomenon, allowing researchers to gain a deeper understanding of the topic.

2. Baseline Information

The information gathered through descriptive research can serve as a baseline for future research and provide a foundation for further studies.

3. Informative Data

Descriptive research can provide valuable information and insights into a particular topic, which can inform future research, policy decisions, and programs.

4. Sampling Validation

Descriptive research can be used to validate sampling methods and to help researchers determine the best approach for their study.

5. Cost Effective

Descriptive research is often less expensive and less time-consuming than other research methods , making it a cost-effective way to gather information about a particular population or phenomenon.

6. Easy to Replicate

Descriptive research is straightforward to replicate, making it a reliable way to gather and compare information from multiple sources.

Key Characteristics of Descriptive Research Design

The primary purpose of descriptive research is to describe the characteristics, behaviors, and attributes of a particular population or phenomenon.

2. Participants and Sampling

Descriptive research studies a particular population or sample that is representative of the larger population being studied. Furthermore, sampling methods can include convenience, stratified, or random sampling.

3. Data Collection Techniques

Descriptive research typically involves the collection of both qualitative and quantitative data through methods such as surveys, observational studies, case studies, or focus groups.

4. Data Analysis

Descriptive research data is analyzed to identify patterns, relationships, and trends within the data. Statistical techniques , such as frequency distributions and descriptive statistics, are commonly used to summarize and describe the data.

5. Focus on Description

Descriptive research is focused on describing and summarizing the characteristics of a particular population or phenomenon. It does not make causal inferences.

6. Non-Experimental

Descriptive research is non-experimental, meaning that the researcher does not manipulate variables or control conditions. The researcher simply observes and collects data on the population or phenomenon being studied.

When Can a Researcher Conduct Descriptive Research?

A researcher can conduct descriptive research in the following situations:

- To better understand a particular population or phenomenon

- To describe the relationships between variables

- To describe patterns and trends

- To validate sampling methods and determine the best approach for a study

- To compare data from multiple sources.

Types of Descriptive Research Design

1. survey research.

Surveys are a type of descriptive research that involves collecting data through self-administered or interviewer-administered questionnaires. Additionally, they can be administered in-person, by mail, or online, and can collect both qualitative and quantitative data.

2. Observational Research

Observational research involves observing and collecting data on a particular population or phenomenon without manipulating variables or controlling conditions. It can be conducted in naturalistic settings or controlled laboratory settings.

3. Case Study Research

Case study research is a type of descriptive research that focuses on a single individual, group, or event. It involves collecting detailed information on the subject through a variety of methods, including interviews, observations, and examination of documents.

4. Focus Group Research

Focus group research involves bringing together a small group of people to discuss a particular topic or product. Furthermore, the group is usually moderated by a researcher and the discussion is recorded for later analysis.

5. Ethnographic Research

Ethnographic research involves conducting detailed observations of a particular culture or community. It is often used to gain a deep understanding of the beliefs, behaviors, and practices of a particular group.

Advantages of Descriptive Research Design

1. provides a comprehensive understanding.

Descriptive research provides a comprehensive picture of the characteristics, behaviors, and attributes of a particular population or phenomenon, which can be useful in informing future research and policy decisions.

2. Non-invasive

Descriptive research is non-invasive and does not manipulate variables or control conditions, making it a suitable method for sensitive or ethical concerns.

3. Flexibility

Descriptive research allows for a wide range of data collection methods , including surveys, observational studies, case studies, and focus groups, making it a flexible and versatile research method.

4. Cost-effective

Descriptive research is often less expensive and less time-consuming than other research methods. Moreover, it gives a cost-effective option to many researchers.

5. Easy to Replicate

Descriptive research is easy to replicate, making it a reliable way to gather and compare information from multiple sources.

6. Informs Future Research

The insights gained from a descriptive research can inform future research and inform policy decisions and programs.

Disadvantages of Descriptive Research Design

1. limited scope.

Descriptive research only provides a snapshot of the current situation and cannot establish cause-and-effect relationships.

2. Dependence on Existing Data

Descriptive research relies on existing data, which may not always be comprehensive or accurate.

3. Lack of Control

Researchers have no control over the variables in descriptive research, which can limit the conclusions that can be drawn.

The researcher’s own biases and preconceptions can influence the interpretation of the data.

5. Lack of Generalizability

Descriptive research findings may not be applicable to other populations or situations.

6. Lack of Depth

Descriptive research provides a surface-level understanding of a phenomenon, rather than a deep understanding.

7. Time-consuming

Descriptive research often requires a large amount of data collection and analysis, which can be time-consuming and resource-intensive.

7 Ways to Avoid Common Flaws While Designing Descriptive Research

1. Clearly define the research question

A clearly defined research question is the foundation of any research study, and it is important to ensure that the question is both specific and relevant to the topic being studied.

2. Choose the appropriate research design

Choosing the appropriate research design for a study is crucial to the success of the study. Moreover, researchers should choose a design that best fits the research question and the type of data needed to answer it.

3. Select a representative sample

Selecting a representative sample is important to ensure that the findings of the study are generalizable to the population being studied. Researchers should use a sampling method that provides a random and representative sample of the population.

4. Use valid and reliable data collection methods

Using valid and reliable data collection methods is important to ensure that the data collected is accurate and can be used to answer the research question. Researchers should choose methods that are appropriate for the study and that can be administered consistently and systematically.

5. Minimize bias

Bias can significantly impact the validity and reliability of research findings. Furthermore, it is important to minimize bias in all aspects of the study, from the selection of participants to the analysis of data.

6. Ensure adequate sample size

An adequate sample size is important to ensure that the results of the study are statistically significant and can be generalized to the population being studied.

7. Use appropriate data analysis techniques

The appropriate data analysis technique depends on the type of data collected and the research question being asked. Researchers should choose techniques that are appropriate for the data and the question being asked.

Have you worked on descriptive research designs? How was your experience creating a descriptive design? What challenges did you face? Do write to us or leave a comment below and share your insights on descriptive research designs!

extremely very educative

Indeed very educative and useful. Well explained. Thank you

Simple,easy to understand

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

![can descriptive research be qualitative and quantitative What is Academic Integrity and How to Uphold it [FREE CHECKLIST]](https://www.enago.com/academy/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/FeatureImages-59-210x136.png)

Ensuring Academic Integrity and Transparency in Academic Research: A comprehensive checklist for researchers

Academic integrity is the foundation upon which the credibility and value of scientific findings are…

- Publishing Research

- Reporting Research

How to Optimize Your Research Process: A step-by-step guide

For researchers across disciplines, the path to uncovering novel findings and insights is often filled…

- Industry News

- Trending Now

Breaking Barriers: Sony and Nature unveil “Women in Technology Award”

Sony Group Corporation and the prestigious scientific journal Nature have collaborated to launch the inaugural…

Achieving Research Excellence: Checklist for good research practices

Academia is built on the foundation of trustworthy and high-quality research, supported by the pillars…

- Promoting Research

Plain Language Summary — Communicating your research to bridge the academic-lay gap

Science can be complex, but does that mean it should not be accessible to the…

Choosing the Right Analytical Approach: Thematic analysis vs. content analysis for…

Comparing Cross Sectional and Longitudinal Studies: 5 steps for choosing the right…

Research Recommendations – Guiding policy-makers for evidence-based decision making

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

Root out friction in every digital experience, super-charge conversion rates, and optimize digital self-service

Uncover insights from any interaction, deliver AI-powered agent coaching, and reduce cost to serve

Increase revenue and loyalty with real-time insights and recommendations delivered to teams on the ground

Know how your people feel and empower managers to improve employee engagement, productivity, and retention

Take action in the moments that matter most along the employee journey and drive bottom line growth

Whatever they’re are saying, wherever they’re saying it, know exactly what’s going on with your people

Get faster, richer insights with qual and quant tools that make powerful market research available to everyone

Run concept tests, pricing studies, prototyping + more with fast, powerful studies designed by UX research experts

Track your brand performance 24/7 and act quickly to respond to opportunities and challenges in your market

Explore the platform powering Experience Management

- Free Account

- For Digital

- For Customer Care

- For Human Resources

- For Researchers

- Financial Services

- All Industries

Popular Use Cases

- Customer Experience

- Employee Experience

- Net Promoter Score

- Voice of Customer

- Customer Success Hub

- Product Documentation

- Training & Certification

- XM Institute

- Popular Resources

- Customer Stories

- Artificial Intelligence

Market Research

- Partnerships

- Marketplace

The annual gathering of the experience leaders at the world’s iconic brands building breakthrough business results, live in Salt Lake City.

- English/AU & NZ

- Español/Europa

- Español/América Latina

- Português Brasileiro

- REQUEST DEMO

- Experience Management

- Descriptive Research

Try Qualtrics for free

Descriptive research: what it is and how to use it.

8 min read Understanding the who, what and where of a situation or target group is an essential part of effective research and making informed business decisions.

For example you might want to understand what percentage of CEOs have a bachelor’s degree or higher. Or you might want to understand what percentage of low income families receive government support – or what kind of support they receive.

Descriptive research is what will be used in these types of studies.

In this guide we’ll look through the main issues relating to descriptive research to give you a better understanding of what it is, and how and why you can use it.

Free eBook: 2024 global market research trends report

What is descriptive research?

Descriptive research is a research method used to try and determine the characteristics of a population or particular phenomenon.

Using descriptive research you can identify patterns in the characteristics of a group to essentially establish everything you need to understand apart from why something has happened.

Market researchers use descriptive research for a range of commercial purposes to guide key decisions.

For example you could use descriptive research to understand fashion trends in a given city when planning your clothing collection for the year. Using descriptive research you can conduct in depth analysis on the demographic makeup of your target area and use the data analysis to establish buying patterns.

Conducting descriptive research wouldn’t, however, tell you why shoppers are buying a particular type of fashion item.

Descriptive research design

Descriptive research design uses a range of both qualitative research and quantitative data (although quantitative research is the primary research method) to gather information to make accurate predictions about a particular problem or hypothesis.

As a survey method, descriptive research designs will help researchers identify characteristics in their target market or particular population.

These characteristics in the population sample can be identified, observed and measured to guide decisions.

Descriptive research characteristics

While there are a number of descriptive research methods you can deploy for data collection, descriptive research does have a number of predictable characteristics.

Here are a few of the things to consider:

Measure data trends with statistical outcomes

Descriptive research is often popular for survey research because it generates answers in a statistical form, which makes it easy for researchers to carry out a simple statistical analysis to interpret what the data is saying.

Descriptive research design is ideal for further research

Because the data collection for descriptive research produces statistical outcomes, it can also be used as secondary data for another research study.

Plus, the data collected from descriptive research can be subjected to other types of data analysis .

Uncontrolled variables

A key component of the descriptive research method is that it uses random variables that are not controlled by the researchers. This is because descriptive research aims to understand the natural behavior of the research subject.

It’s carried out in a natural environment

Descriptive research is often carried out in a natural environment. This is because researchers aim to gather data in a natural setting to avoid swaying respondents.

Data can be gathered using survey questions or online surveys.

For example, if you want to understand the fashion trends we mentioned earlier, you would set up a study in which a researcher observes people in the respondent’s natural environment to understand their habits and preferences.

Descriptive research allows for cross sectional study

Because of the nature of descriptive research design and the randomness of the sample group being observed, descriptive research is ideal for cross sectional studies – essentially the demographics of the group can vary widely and your aim is to gain insights from within the group.

This can be highly beneficial when you’re looking to understand the behaviors or preferences of a wider population.

Descriptive research advantages

There are many advantages to using descriptive research, some of them include:

Cost effectiveness

Because the elements needed for descriptive research design are not specific or highly targeted (and occur within the respondent’s natural environment) this type of study is relatively cheap to carry out.

Multiple types of data can be collected

A big advantage of this research type, is that you can use it to collect both quantitative and qualitative data. This means you can use the stats gathered to easily identify underlying patterns in your respondents’ behavior.

Descriptive research disadvantages

Potential reliability issues.

When conducting descriptive research it’s important that the initial survey questions are properly formulated.

If not, it could make the answers unreliable and risk the credibility of your study.

Potential limitations

As we’ve mentioned, descriptive research design is ideal for understanding the what, who or where of a situation or phenomenon.

However, it can’t help you understand the cause or effect of the behavior. This means you’ll need to conduct further research to get a more complete picture of a situation.

Descriptive research methods

Because descriptive research methods include a range of quantitative and qualitative research, there are several research methods you can use.

Use case studies

Case studies in descriptive research involve conducting in-depth and detailed studies in which researchers get a specific person or case to answer questions.

Case studies shouldn’t be used to generate results, rather it should be used to build or establish hypothesis that you can expand into further market research .

For example you could gather detailed data about a specific business phenomenon, and then use this deeper understanding of that specific case.

Use observational methods

This type of study uses qualitative observations to understand human behavior within a particular group.

By understanding how the different demographics respond within your sample you can identify patterns and trends.

As an observational method, descriptive research will not tell you the cause of any particular behaviors, but that could be established with further research.

Use survey research

Surveys are one of the most cost effective ways to gather descriptive data.

An online survey or questionnaire can be used in descriptive studies to gather quantitative information about a particular problem.

Survey research is ideal if you’re using descriptive research as your primary research.

Descriptive research examples

Descriptive research is used for a number of commercial purposes or when organizations need to understand the behaviors or opinions of a population.

One of the biggest examples of descriptive research that is used in every democratic country, is during elections.

Using descriptive research, researchers will use surveys to understand who voters are more likely to choose out of the parties or candidates available.

Using the data provided, researchers can analyze the data to understand what the election result will be.

In a commercial setting, retailers often use descriptive research to figure out trends in shopping and buying decisions.

By gathering information on the habits of shoppers, retailers can get a better understanding of the purchases being made.

Another example that is widely used around the world, is the national census that takes place to understand the population.

The research will provide a more accurate picture of a population’s demographic makeup and help to understand changes over time in areas like population age, health and education level.

Where Qualtrics helps with descriptive research

Whatever type of research you want to carry out, there’s a survey type that will work.

Qualtrics can help you determine the appropriate method and ensure you design a study that will deliver the insights you need.

Our experts can help you with your market research needs , ensuring you get the most out of Qualtrics market research software to design, launch and analyze your data to guide better, more accurate decisions for your organization.

Related resources

Market intelligence 10 min read, marketing insights 11 min read, ethnographic research 11 min read, qualitative vs quantitative research 13 min read, qualitative research questions 11 min read, qualitative research design 12 min read, primary vs secondary research 14 min read, request demo.

Ready to learn more about Qualtrics?

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Descriptive Research Design | Definition, Methods & Examples

Descriptive Research Design | Definition, Methods & Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 10 October 2022.

Descriptive research aims to accurately and systematically describe a population, situation or phenomenon. It can answer what , where , when , and how questions , but not why questions.

A descriptive research design can use a wide variety of research methods to investigate one or more variables . Unlike in experimental research , the researcher does not control or manipulate any of the variables, but only observes and measures them.

Table of contents

When to use a descriptive research design, descriptive research methods.

Descriptive research is an appropriate choice when the research aim is to identify characteristics, frequencies, trends, and categories.

It is useful when not much is known yet about the topic or problem. Before you can research why something happens, you need to understand how, when, and where it happens.

- How has the London housing market changed over the past 20 years?

- Do customers of company X prefer product Y or product Z?

- What are the main genetic, behavioural, and morphological differences between European wildcats and domestic cats?

- What are the most popular online news sources among under-18s?

- How prevalent is disease A in population B?

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Descriptive research is usually defined as a type of quantitative research , though qualitative research can also be used for descriptive purposes. The research design should be carefully developed to ensure that the results are valid and reliable .

Survey research allows you to gather large volumes of data that can be analysed for frequencies, averages, and patterns. Common uses of surveys include:

- Describing the demographics of a country or region

- Gauging public opinion on political and social topics

- Evaluating satisfaction with a company’s products or an organisation’s services

Observations

Observations allow you to gather data on behaviours and phenomena without having to rely on the honesty and accuracy of respondents. This method is often used by psychological, social, and market researchers to understand how people act in real-life situations.

Observation of physical entities and phenomena is also an important part of research in the natural sciences. Before you can develop testable hypotheses , models, or theories, it’s necessary to observe and systematically describe the subject under investigation.

Case studies

A case study can be used to describe the characteristics of a specific subject (such as a person, group, event, or organisation). Instead of gathering a large volume of data to identify patterns across time or location, case studies gather detailed data to identify the characteristics of a narrowly defined subject.

Rather than aiming to describe generalisable facts, case studies often focus on unusual or interesting cases that challenge assumptions, add complexity, or reveal something new about a research problem .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2022, October 10). Descriptive Research Design | Definition, Methods & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/descriptive-research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, a quick guide to experimental design | 5 steps & examples, correlational research | guide, design & examples, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods.

41.1 What Is Descriptive Research?

The type of question asked by the researcher will ultimately determine the type of approach necessary to complete an accurate assessment of the topic at hand. Descriptive studies, primarily concerned with finding out "what is," might be applied to investigate the following questions: Do teachers hold favorable attitudes toward using computers in schools? What kinds of activities that involve technology occur in sixth-grade classrooms and how frequently do they occur? What have been the reactions of school administrators to technological innovations in teaching the social sciences? How have high school computing courses changed over the last 10 years? How do the new multimediated textbooks compare to the print-based textbooks? How are decisions being made about using Channel One in schools, and for those schools that choose to use it, how is Channel One being implemented? What is the best way to provide access to computer equipment in schools? How should instructional designers improve software design to make the software more appealing to students? To what degree are special-education teachers well versed concerning assistive technology? Is there a relationship between experience with multimedia computers and problem-solving skills? How successful is a certain satellite-delivered Spanish course in terms of motivational value and academic achievement? Do teachers actually implement technology in the way they perceive? How many people use the AECT gopher server, and what do they use if for?

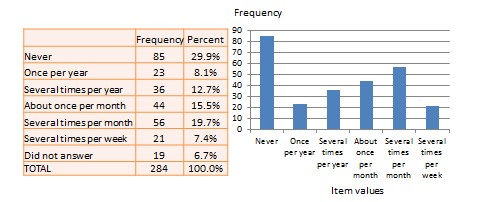

Descriptive research can be either quantitative or qualitative. It can involve collections of quantitative information that can be tabulated along a continuum in numerical form, such as scores on a test or the number of times a person chooses to use a-certain feature of a multimedia program, or it can describe categories of information such as gender or patterns of interaction when using technology in a group situation. Descriptive research involves gathering data that describe events and then organizes, tabulates, depicts, and describes the data collection (Glass & Hopkins, 1984). It often uses visual aids such as graphs and charts to aid the reader in understanding the data distribution. Because the human mind cannot extract the full import of a large mass of raw data, descriptive statistics are very important in reducing the data to manageable form. When in-depth, narrative descriptions of small numbers of cases are involved, the research uses description as a tool to organize data into patterns that emerge during analysis. Those patterns aid the mind in comprehending a qualitative study and its implications.

Most quantitative research falls into two areas: studies that describe events and studies aimed at discovering inferences or causal relationships. Descriptive studies are aimed at finding out "what is," so observational and survey methods are frequently used to collect descriptive data (Borg & Gall, 1989). Studies of this type might describe the current state of multimedia usage in schools or patterns of activity resulting from group work at the computer. An example of this is Cochenour, Hakes, and Neal's (1994) study of trends in compressed video applications with education and the private sector.

Descriptive studies report summary data such as measures of central tendency including the mean, median, mode, deviance from the mean, variation, percentage, and correlation between variables. Survey research commonly includes that type of measurement, but often goes beyond the descriptive statistics in order to draw inferences. See, for example, Signer's (1991) survey of computer-assisted instruction and at-risk students, or Nolan, McKinnon, and Soler's (1992) research on achieving equitable access to school computers. Thick, rich descriptions of phenomena can also emerge from qualitative studies, case studies, observational studies, interviews, and portfolio assessments. Robinson's (1994) case study of a televised news program in classrooms and Lee's (1994) case study about identifying values concerning school restructuring are excellent examples of case studies.

Descriptive research is unique in the number of variables employed. Like other types of research, descriptive research can include multiple variables for analysis, yet unlike other methods, it requires only one variable (Borg & Gall, 1989). For example, a descriptive study might employ methods of analyzing correlations between multiple variables by using tests such as Pearson's Product Moment correlation, regression, or multiple regression analysis. Good examples of this are the Knupfer and Hayes (1994) study about the effects of the Channel One broadcast on knowledge of current events, Manaev's (1991) study about mass media effectiveness, McKenna's (1993) study of the relationship between attributes of a radio program and it's appeal to listeners, Orey and Nelson's (1994) examination of learner interactions with hypermedia environments, and Shapiro's (1991) study of memory and decision processes.

On the other hand, descriptive research might simply report the percentage summary on a single variable. Examples of this are the tally of reference citations in selected instructional design and technology journals by Anglin and Towers (1992); Barry's (1994) investigation of the controversy surrounding advertising and Channel One; Lu, Morlan, Lerchlorlarn, Lee, and Dike's (1993) investigation of the international utilization of media in education (1993); and Pettersson, Metallinos, Muffoletto, Shaw, and Takakuwa's (1993) analysis of the use of verbo-visual information in teaching geography in various countries.

Descriptive statistics utilize data collection and analysis techniques that yield reports concerning the measures of central tendency, variation, and correlation. The combination of its characteristic summary and correlational statistics, along with its focus on specific types of research questions, methods, and outcomes is what distinguishes descriptive research from other research types.

Three main purposes of research are to describe, explain, and validate findings. Description emerges following creative exploration, and serves to organize the findings in order to fit them with explanations, and then test or validate those explanations (Krathwohl, 1993). Many research studies call for the description of natural or man-made phenomena such as their form, structure, activity, change over time, relation to other phenomena, and so on. The description often illuminates knowledge that we might not otherwise notice or even encounter. Several important scientific discoveries as well as anthropological information about events outside of our common experiences have resulted from making such descriptions. For example, astronomers use their telescopes to develop descriptions of different parts of the universe, anthropologists describe life events of socially atypical situations or cultures uniquely different from our own, and educational researchers describe activities within classrooms concerning the implementation of technology. This process sometimes results in the discovery of stars and stellar events, new knowledge about value systems or practices of other cultures, or even the reality of classroom life as new technologies are implemented within schools.

Educational researchers might use observational, survey, and interview techniques to collect data about group dynamics during computer-based activities. These data could then be used to recommend specific strategies for implementing computers or improving teaching strategies. Two excellent studies concerning the role of collaborative groups were conducted by Webb (1982), and Rysavy and Sales (1991). Noreen Webb's landmark study used descriptive research techniques to investigate collaborative groups as they worked within classrooms. Rysavy and Sales also apply a descriptive approach to study the role of group collaboration for working at computers. The Rysavy and Sales approach did not observe students in classrooms, but reported certain common findings that emerged through a literature search.

Descriptive studies have an important role in educational research. They have greatly increased our knowledge about what happens in schools. Some of the important books in education have reported studies of this type: Life in Classrooms, by Philip Jackson; The Good High School, by Sara Lawrence Lightfoot; Teachers and Machines: The Classroom Use of Technology Since 1920, by Larry Cuban; A Place Called School, by John Goodlad; Visual Literacy: A Spectrum of Learning, by D. M. Moore and Dwyer; Computers in Education: Social, Political, and Historical Perspectives, by Muffoletto and Knupfer; and Contemporary Issues in American Distance Education, by M. G. Moore.

Henry J. Becker's (1986) series of survey reports concerning the implementation of computers into schools across the United States as well as Nancy Nelson Knupfer's (1988) reports about teacher's opinions and patterns of computer usage also fit partially within the realm of descriptive research. Both studies describe categories of data and use statistical analysis to examine correlations between specific variables. Both also go beyond the bounds of descriptive research and conduct further statistical procedures appropriate to their research questions, thus enabling them to make further recommendations about implementing computing technology in ways to support grassroots change and equitable practices within the schools. Finally, Knupfer's study extended the analysis and conclusions in order to yield suggestions for instructional designers involved with educational computing.

41.1.1 The Nature of Descriptive Research

The descriptive function of research is heavily dependent on instrumentation for measurement and observation (Borg & Gall, 1989). Researchers may work for many years to perfect such instrumentation so that the resulting measurement will be accurate, reliable, and generalizable. Instruments such as the electron microscope, standardized tests for various purposes, the United States census, Michael Simonson's questionnaires about computer usage, and scores of thoroughly validated questionnaires are examples of some instruments that yield valuable descriptive data. Once the instruments are developed, they can be used to describe phenomena of interest to the researchers.

The intent of some descriptive research is to produce statistical information about aspects of education that interests policy makers and educators. The National Center for Education Statistics specializes in this kind of research. Many of its findings are published in an annual volume

called Digest of Educational Statistics. The center also administers the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), which collects descriptive information about how well the nation's youth are doing in various subject areas. A typical NAEP publication is The Reading Report Card, which provides descriptive information about the reading achievement of junior high and high school students during the past 2 decades.

On a larger scale, the International Association for the Evaluation of Education Achievement (IEA) has done major descriptive studies comparing the academic achievement levels of students in many different nations, including the United States (Borg & Gall, 1989). Within the United States, huge amounts of information are being gathered continuously by the Office of Technology Assessment, which influences policy concerning technology in education. As a way of offering guidance about the potential of technologies for distance education, that office has published a book called Linking for Learning: A New Course for Education, which offers descriptions of distance education and its potential.

There has been an ongoing debate among researchers about the value of quantitative (see 40.1.2) versus qualitative research, and certain remarks have targeted descriptive research as being less pure than traditional experimental, quantitative designs. Rumors abound that young researchers must conduct quantitative research in order to get published in Educational Technology Research and Development and other prestigious journals in the field. One camp argues the benefits of a scientific approach to educational research, thus preferring the experimental, quantitative approach, while the other camp posits the need to recognize the unique human side of educational research questions and thus prefers to use qualitative research methodology. Because descriptive research spans both quantitative and qualitative methodologies, it brings the ability to describe events in greater or less depth as needed, to focus on various elements of different research techniques, and to engage quantitative statistics to organize information in meaningful ways. The citations within this chapter provide ample evidence that descriptive research can indeed be published in prestigious journals.

Descriptive studies can yield rich data that lead to important recommendations. For example, Galloway (1992) bases recommendations for teaching with computer analogies on descriptive data, and Wehrs (1992) draws reasonable conclusions about using expert systems to support academic advising. On the other hand, descriptive research can be misused by those who do not understand its purpose and limitations. For example, one cannot try to draw conclusions that show cause and effect, because that is beyond the bounds of the statistics employed.

Borg and Gall (1989) classify the outcomes of educational research into the four categories of description, prediction, improvement, and explanation. They say that descriptive research describes natural or man-made educational phenomena that is of interest to policy makers and educators. Predictions of educational phenomenon seek to determine whether certain students are at risk and if teachers should use different techniques to instruct them. Research about improvement asks whether a certain technique does something to help students learn better and whether certain interventions can improve student learning by applying causal-comparative, correlational, and experimental methods. The final category of explanation posits that research is able to explain a set of phenomena that leads to our ability to describe, predict, and control the phenomena with a high level of certainty and accuracy. This usually takes the form of theories.

The methods of collecting data for descriptive research can be employed singly or in various combinations, depending on the research questions at hand. Descriptive research often calls upon quasi-experimental research design (Campbell & Stanley, 1963). Some of the common data collection methods applied to questions within the realm of descriptive research include surveys, interviews, observations, and portfolios.

Survey descriptive research: Method, design, and examples

- November 2, 2022

What is survey descriptive research?

The observational method: monitor people while they engage with a subject, the case study method: gain an in-depth understanding of a subject, survey descriptive research: easy and cost-effective, types of descriptive research design, what is the descriptive survey research design definition by authors, 1. quantitativeness and qualitatively, 2. uncontrolled variables, 3. natural environment, 4. provides a solid basis for further research, describe a group and define its characteristics, measure data trends by conducting descriptive marketing research, understand how customers perceive a brand, descriptive survey research design: how to make the best descriptive questionnaire, create descriptive surveys with surveyplanet.

Survey descriptive research is a quantitative method that focuses on describing the characteristics of a phenomenon rather than asking why it occurs. Doing this provides a better understanding of the nature of the subject at hand and creates a good foundation for further research.

Descriptive market research is one of the most commonly used ways of examining trends and changes in the market. It is easy, low-cost, and provides valuable in-depth information on a chosen subject.

This article will examine the basic principles of the descriptive survey study and show how to make the best descriptive survey questionnaire and how to conduct effective research.

It is often said to be quantitative research that focuses more on the what, how, when, and where instead of the why. But what does that actually mean?

The answer is simple. By conducting descriptive survey research, the nature of a phenomenon is focused upon without asking about what causes it.

The main goal of survey descriptive research is to shed light on the heart of the research problem and better understand it. The technique provides in-depth knowledge of what the research problem is before investigating why it exists.

Survey descriptive research and data collection methods

Descriptive research methods can differ based on data collection. We distinguish three main data collection methods: case study, observational method, and descriptive survey method.

Of these, the descriptive survey research method is most commonly used in fields such as market research, social research, psychology, politics, etc.

Sometimes also called the observational descriptive method, this is simply monitoring people while they engage with a particular subject. The aim is to examine people’s real-life behavior by maintaining a natural environment that does not change the respondents’ behavior—because they do not know they are being observed.

It is often used in fields such as market research, psychology, or social research. For example, customers can be monitored while dining at a restaurant or browsing through the products in a shop.

When doing case studies, researchers conduct thorough examinations of individuals or groups. The case study method is not used to collect general information on a particular subject. Instead, it provides an in-depth understanding of a particular subject and can give rise to interesting conclusions and new hypotheses.

The term case study can also refer to a sample group, which is a specific group of people that are examined and, afterward, findings are generalized to a larger group of people. However, this kind of generalization is rather risky because it is not always accurate.

Additionally, case studies cannot be used to determine cause and effect because of potential bias on the researcher’s part.

The survey descriptive research method consists of creating questionnaires or polls and distributing them to respondents, who then answer the questions (usually a mix of open-ended and closed-ended).