Case Study: Capsizing Of Costa Concordia

It’s said that history often repeats itself. After 100 years from 1912, when the Titanic met its unfortunate fate, a similar incident happened with a famous cruise ship, making it second in the line of the most infamous shipwrecks.

The ship Costa Concordia was operated by the famous Italian cruise line Costa Crociere, part of Carnival Corporation. It was constructed in Fincantieri’s Sestri Ponente shipyard at a whopping price of €450m. Since 1947, when the company commenced passenger services, it established a good reputation over the years and ultimately became one of the largest cruise operators in the world.

Costa Concordia was the first in the Concordia Class, sistering four other cruises, including the Carnival Splendor. However, the capsizing of one of its star cruise ships, barely seven years in service, left a dent in the company’s reputation and raised serious concerns over international cruising.

The following article sheds light on the reasons behind the capsizing and lists the circumstances that led to the disaster.

Table of Contents

The Accident

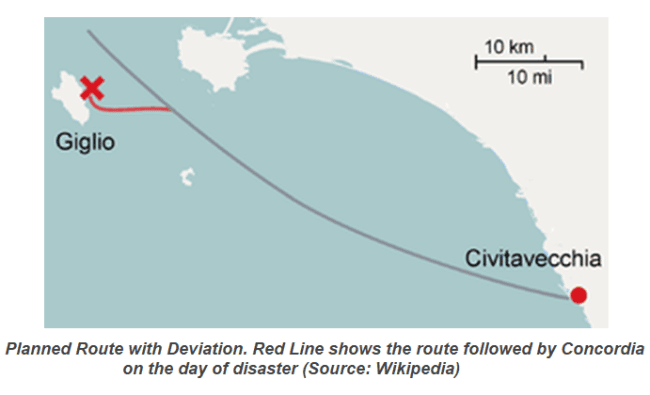

Costa Concordia was taking its passengers on a seven-day journey from Civitavecchia and Savona.

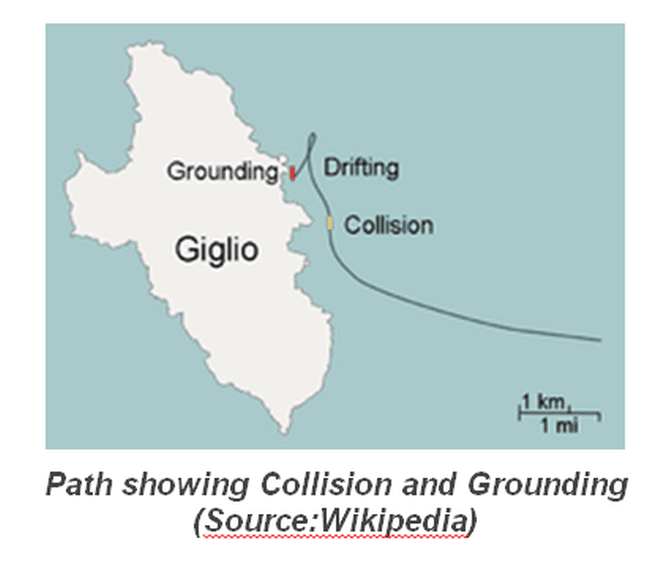

On January 13, 2012, Costa Concordia struck her starboard side on an underwater reef near the island of Isola del Giglio, close to the Italian coast of Tuscany in the Tyrrhenian Sea. The ship immediately lost all propulsive power, and soon after, there was a complete blackout as water reached the electrical panels, propulsion controls and the engine room. The breach resulted in a 60-meter-long gash in the ship’s hull. This led to the rapid flooding of the watertight compartments and ultimately led to its sinking.

It isn’t easy to comprehend that such an incident can happen given the availability of advanced technology and instrumentation providing precise and detailed information of every possible circumstance a ship may face. From rough seas to ocean floor mapping to high-speed winds, all relevant data is available with a vessel at regular intervals. The topography of any area in which the ship sails forth is already available on board a ship.

Despite all this, the ship Costa Concordia struck an underwater reef off the coast of Giglio island and grounded, finally resting on the rocks near the coast.

Since the ship lay in a protected marine region close to the island of Giglio, the environmental reasons, salvage, and the shipwreck posed major concerns to Italy’s Ministry of Infrastructures and Transports.

What went wrong that night?

A big question arises as to why the ship was sailing so near the coast in the first place, which ultimately led to one of the most horrifying disasters in international cruising.

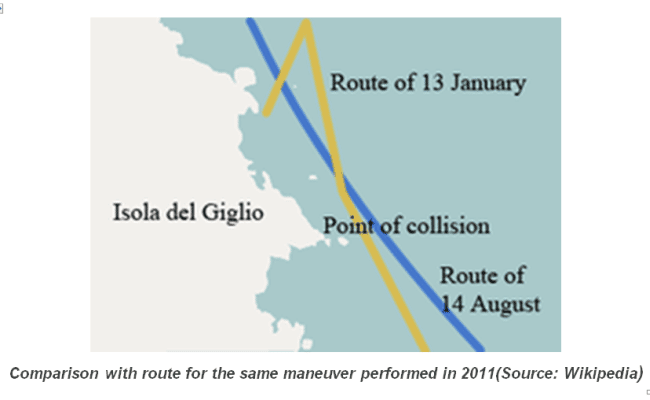

Most cruise ships perform what is called a Sail – By Maneuver. The ship takes a slight deviation from its official course to sail near an island to give the passengers a unique glimpse of it and salute the fellow sailors on land. This routine manoeuvre in cruise lining has been practised successfully worldwide for years. The ship’s deviation course is plotted in such a way so that it is at a minimum safe distance from the island to prevent any situation of grounding in shallow waters or due to the presence of rocks and reefs near the coast. Concordia had also performed it for the same island in its past voyages.

So what possibly went wrong this time, endangering the lives of around 4000 people on board which would ultimately change the cruising industry forever?

Concordia’s deviation course required it to stay at least 1500 ft away from the island. But as it turned out, the ship landed around 659 meters closer to the coast. This egregious error due to a series of miscommunications between the captain, first officers and the officer at the helm is reflected later in the investigative report.

Because of the incorrect heading angles, the ship’s turning radius was much more comprehensive than it was supposed to be as per the chartered deviation, ultimately bringing the vessel close to the shore.

By the time the captain realised the situation and started giving a series of orders for rudder turns, it was too late as the ship was already too close and moving at high speed of 16 knots. The erroneous executions of an order by the helmsman and delay in correcting them ultimately left Concordia no chance to pass safely.

Many passengers said they did not hear the alarm to proceed to lifeboats, and the evacuation process was chaotic.

It was also found through a recorded phone call with Costa Crociere’s crisis coordinator, Roberto Ferrarini, that captain Francesco Schettino tried to cover his actions. He gave false information that the crash occurred due to the blackout instead of the other way round. He was also blamed for delaying rescue as he did not immediately alert the Italian Coast guard and the Search and Rescue Authority.

He boldly referred to maritime superstitions, and his lawyer called the ship unfateful. He mentioned how the champagne bottle failed to break when swung against the hull during her christening ceremony. Everything about the ship was mysterious, his lawyer had said.

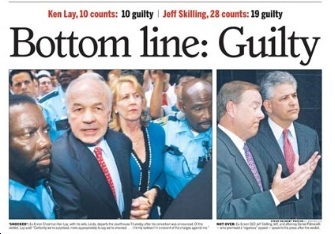

During the 19-month trial, he pleaded to be innocent and that his actions had saved lives. However, the prosecutors called him an ‘idiot’ and charged him with manslaughter for causing the wreck, abandoning the ship and delaying rescue operations.

The Italian courts found captain Schettino, four crew members and an official of the company guilty of the accident and preventing a safe evacuation. The vessel was wreckage due to their negligence and irresponsible actions, which led to the death of 32 people while 4200 were safely rescued, per media and investigation reports.

After four months of the disaster, two salvage companies, Titan and Micoperi, were contacted to salvage the ship, and it was taken to Genoa to be dismantled.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. what happened to costa concordia.

The wrecked remains of the gigantic cruise liner were scrapped in the port of Genoa, Italy. Its 50,000 tonnes of steel were melted for other construction projects.

2. Where is Costa Concordia’s ship captain?

The captain of the ship Costa Concordia, Francesco Schettino, is serving a 16-year prison sentence for manslaughter and other charges. He had ordered the crew to steer the ship away from the designated course towards the shore, known as tourist navigation, to give passengers and people onshore a good view.

3. How much compensation did the passengers get?

During the trial, Costa informed the court that it paid 84 million euros in compensation to the passengers, crew members and relatives of the people who died in the tragic accident, per the Italian media reports of the time.

4. How many people died on the Costa Concordia?

Per investigation reports, 34 people, including 27 passengers, five crew members and two salvage crew, died in the accident. Around 64 people reported non-fatal injuries, and over 4000 were safely rescued.

5. Was the Costa Concordia captain drunk?

The cruise ship captain drank wine with a beautiful lady before the accident. This was claimed by one of the witnesses during the investigation. Many also believe the captain was distracted by a woman he brought onboard the cruise ship.

You might also like to read

- Costa Concordia Cruise Ship: Know The ill-fated Ship

- Watch: Time-Lapse Video Of Costa Concordia Wreck Removal Project

- Watch: Footage Shows Costa Concordia Captain Preparing To Leave The Sinking Ship

- How To Become a Cruise Ship Captain: Qualification, Lifestyle & Responsibilities

- Ship Stability – Understanding Intact Stability of Ships

Disclaimer : The information contained in this website is for general information purposes only. While we endeavour to keep the information up to date and correct, we make no representations or warranties of any kind, express or implied, about the completeness, accuracy, reliability, suitability or availability with respect to the website or the information, products, services, or related graphics contained on the website for any purpose. Any reliance you place on such information is therefore strictly at your own risk.

In no event will we be liable for any loss or damage including without limitation, indirect or consequential loss or damage, or any loss or damage whatsoever arising from loss of data or profits arising out of, or in connection with, the use of this website.

Do you have info to share with us ? Suggest a correction

Related Articles

9 New Aspects of IACS Harmonised Common Structural Rules (CSR) For Ships

What Is The Purpose Of “Torsion Box” In Ships?

Types of Bow Designs Used For Ships

About Author

Shivansh is pursuing Naval Architecture and Ocean Engineering at IMU Visakhapatnam India. He is also the Editor- in- Chief of Learn Ship Design- An Acknowledged Student Initiative.

Read More Articles By This Author >

Daily Maritime News, Straight To Your Inbox

Sign Up To Get Daily Newsletters

Join over 60k+ people who read our daily newsletters

By subscribing, you agree to our Privacy Policy and may receive occasional deal communications; you can unsubscribe anytime.

BE THE FIRST TO COMMENT

It was the ultimate responsibility of the captain to make sure that the helm orders were executed as requested. He cannot escape this respinsability.

I PREFER YOUR DOCUMENTAY AND BELIEVE I WILL BE INSIGHT

I need daily shipping news

@Devender: Please subscribe to our newsletter – https://learn.marineinsight.com/subscribe-to-newsletter/

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Subscribe to Marine Insight Daily Newsletter

" * " indicates required fields

Marine Engineering

Marine Engine Air Compressor Marine Boiler Oily Water Separator Marine Electrical Ship Generator Ship Stabilizer

Nautical Science

Mooring Bridge Watchkeeping Ship Manoeuvring Nautical Charts Anchoring Nautical Equipment Shipboard Guidelines

Explore

Free Maritime eBooks Premium Maritime eBooks Marine Safety Financial Planning Marine Careers Maritime Law Ship Dry Dock

Shipping News Maritime Reports Videos Maritime Piracy Offshore Safety Of Life At Sea (SOLAS) MARPOL

WAIT! Did You Download 13 FREE Maritime eBooks?

Sign-up and download instantly!

We respect your privacy and take protecting it very seriously. No spam!

WAIT! Did You Download 12 FREE Maritime eBooks?

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

The Costa Concordia Disaster: How Human Error Made It Worse

By: Becky Little

Updated: August 10, 2023 | Original: June 23, 2021

Many famous naval disasters happen far out at sea, but on January 13, 2012, the Costa Concordia wrecked just off the coast of an Italian island in relatively shallow water. The avoidable disaster killed 32 people and seriously injured many others, and left investigators wondering: Why was the luxury cruise ship sailing so close to the shore in the first place?

During the ensuing trial, prosecutors came up with a tabloid-ready explanation : The married ship captain had sailed it so close to the island to impress a much younger Moldovan dancer with whom he was having an affair.

Whether or not Captain Francesco Schettino was trying to impress his girlfriend is debatable. (Schettino insisted the ship sailed close to shore to salute other mariners and give passengers a good view.) But whatever the reason for getting too close, the Italian courts found the captain, four crew members and one official from the ship’s company, Costa Crociere (part of Carnival Corporation), to be at fault for causing the disaster and preventing a safe evacuation. The wreck was not the fault of unexpected weather or ship malfunction—it was a disaster caused entirely by a series of human errors.

“At any time when you have an incident similar to Concordia, there is never…a single causal factor,” says Brad Schoenwald, a senior marine inspector at the United States Coast Guard. “It is generally a sequence of events, things that line up in a bad way that ultimately create that incident.”

Wrecking Near the Shore

The Concordia was supposed to take passengers on a seven-day Italian cruise from Civitavecchia to Savona. But when it deviated from its planned path to sail closer to the island of Giglio, the ship struck a reef known as the Scole Rocks. The impact damaged the ship, allowing water to seep in and putting the 4,229 people on board in danger.

Sailing close to shore to give passengers a nice view or salute other sailors is known as a “sail-by,” and it’s unclear how often cruise ships perform these maneuvers. Some consider them to be dangerous deviations from planned routes. In its investigative report on the 2012 disaster, Italy’s Ministry of Infrastructures and Transports found that the Concordia “was sailing too close to the coastline, in a poorly lit shore area…at an unsafe distance at night time and at high speed (15.5 kts).”

In his trial, Captain Schettino blamed the shipwreck on Helmsman Jacob Rusli Bin, who he claimed reacted incorrectly to his order; and argued that if the helmsman had reacted correctly and quickly, the ship wouldn’t have wrecked. However, an Italian naval admiral testified in court that even though the helmsman was late in executing the captain’s orders, “the crash would’ve happened anyway.” (The helmsman was one of the four crew members convicted in court for contributing to the disaster.)

A Questionable Evacuation

Evidence introduced in Schettino’s trial suggests that the safety of his passengers and crew wasn’t his number one priority as he assessed the damage to the Concordia. The impact and water leakage caused an electrical blackout on the ship, and a recorded phone call with Costa Crociere’s crisis coordinator, Roberto Ferrarini, shows he tried to downplay and cover up his actions by saying the blackout was what actually caused the accident.

“I have made a mess and practically the whole ship is flooding,” Schettino told Ferrarini while the ship was sinking. “What should I say to the media?… To the port authorities I have said that we had…a blackout.” (Ferrarini was later convicted for contributing to the disaster by delaying rescue operations.)

Schettino also didn’t immediately alert the Italian Search and Rescue Authority about the accident. The impact on the Scole Rocks occurred at about 9:45 p.m. local time, and the first person to contact rescue officials about the ship was someone on the shore, according to the investigative report. Search and Rescue contacted the ship a few minutes after 10:00 p.m., but Schettino didn’t tell them what had happened for about 20 more minutes.

A little more than an hour after impact, the crew began to evacuate the ship. But the report noted that some passengers testified that they didn’t hear the alarm to proceed to the lifeboats. Evacuation was made even more chaotic by the ship listing so far to starboard, making walking inside very difficult and lowering the lifeboats on one side, near to impossible. Making things worse, the crew had dropped the anchor incorrectly, causing the ship to flop over even more dramatically.

Through the confusion, the captain somehow made it into a lifeboat before everyone else had made it off. A coast guard member angrily told him on the phone to “Get back on board, damn it!” —a recorded sound bite that turned into a T-shirt slogan in Italy.

Schettino argued that he fell into a lifeboat because of how the ship was listing to one side, but this argument proved unconvincing. In 2015, a court found Schettino guilty of manslaughter, causing a shipwreck, abandoning ship before passengers and crew were evacuated and lying to authorities about the disaster. He was sentenced to 16 years in prison. In addition to Schettino, Ferrarini and Rusli Bin, the other people who received convictions for their role in the disaster were Cabin Service Director Manrico Giampedroni, First Officer Ciro Ambrosio and Third Officer Silvia Coronica.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Advertisement

From Titanic to Costa Concordia—a century of lessons not learned

- Open access

- Published: 04 September 2012

- Volume 11 , pages 151–167, ( 2012 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Jens-Uwe Schröder-Hinrichs 1 ,

- Erik Hollnagel 2 , 3 &

- Michael Baldauf 1

33k Accesses

96 Citations

3 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The recent foundering of the Costa Concordia in January 2012 demonstrated that accidents can occur even with ships that are considered masterpieces of modern technology and despite more than 100 years of regulatory and technological progress in maritime safety. The purpose of this paper is, however, not to speculate about the concrete causes of the Costa Concordia accident, but rather to consider some human and organizational factors that were present in the Costa Concordia accident as well as in the foundering of the Titanic a century ago, and which can be found in many other maritime accidents over the years. The paper argues that these factors do not work in isolation but in combination and often together with other underlying factors. The paper critically reviews the focus of maritime accident investigations and points out that these factors do not receive sufficient attention. It is argued that the widespread confidence in the efficacy of new or improved technical regulations, that characterizes the recommendations from most maritime accident investigations, has led to a lack of awareness of complex interactions of factors and components in socio-technical systems. If maritime safety is to be sustainably improved, a systemic focus must be adopted in future accident investigations.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Future of Transportation: Ethical, Legal, Social and Economic Impacts of Self-driving Vehicles in the Year 2025

Triple Bottom Line

Leadership, Engineering and Ethical Clashes at Boeing

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

2012 marks the first century since the Titanic sank in the North Atlantic Ocean after colliding with an iceberg. It is ironic, and not a little sad, that another remarkable and equally unimaginable maritime accident happened only a few months short of the centenary of the sinking of the Titanic. Both cases involved state-of-the-art cruise ships—although the state-of-the-art obviously has changed dramatically in the 100 years in between. Whereas the Titanic collided with an iceberg, the Costa Concordia hit an underwater rock. In both cases the ships were subjected to an unexpected and massive flooding. The Titanic sank to the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean. It was only because the Costa Concordia accident occurred in shallow waters that the ship did not completely founder in the Tyrrhenian Sea.

The purpose of this article is to discuss the extent to which the factors involved in the sinking of the Titanic can also be found in the Costa Concordia accident. We are, of course, not thinking of the physical factors and the immediate causes of the accidents, but rather the underlying factors, sometimes referred to as blunt end factors. In the early 1990s, a growing number of cases demonstrated that satisfactory explanations of accidents were possible only if the actual events and actions were seen relative to conditions determined by factors that were removed in time or in space (cf., Hollnagel 2004 ). The concepts of sharp end and blunt end factors were introduced to describe the difference between proximal factors (working here and now) and distal factors (working there and then), and how these in combination might lead to an accident.

While the maritime technology has changed beyond recognition between 1912 and 2012, the human factors—understood as the psychological and physiological characteristics of seafarers—and the organizational factors have not. If humans change, it happens at the pace of evolution, compared to which 100 years is but the blink of an eye. More interestingly, the organizational factors also seem to be very much the same then as now. Organizations have, of course, changed in the way they carry out their work, due to increased horizontal and vertical integration made possible by ubiquitous information technology. But the thinking and attitudes of management have changed less and may possibly not have changed at all, at least when it comes to such issues as risk taking and prioritization of issues relating to operational safety.

It is not the purpose of this paper to speculate about the direct causes of the Costa Concordia accident. It is still too early to draw any conclusions or to propose recommendations about the many aspects that undoubtedly will be unraveled during the inquest. The purpose is rather to show that accidents still happen for the same underlying human and organizational reasons, despite the technological progress in the last 100 years and despite all safety regulations and precautions. It is remarkable that certain underlying conditions are still the same today as at the time of the Titanic. It is even more remarkable—and worse, regrettable—that the accident investigations and the reactions to accidents more or less are the same now as they were 100 years ago.

2 A review of the factual information of both accidents

Before both accidents are discussed, a basic summary of the two events is provided.

2.1 Sinking of the Titanic in 1912

The Titanic was a state-of-the-art passenger ship on her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York in 1912. The ship foundered after a collision with an iceberg in the early morning of 15 April. The events involved in the accident are taken from the official accident report on the basis of the UK Merchant Shipping Acts, 1894 to 1906 (Report on the loss of the SS Titanic 1990 ). As far as the report states, the following facts can be established:

The ship's track was set 25 miles south of the indicated area for field ice between March and July, well within an area where “Icebergs have been seen within this line in April, May and June.” (p. 24)

The accident investigation report makes reference to several sailing directions that pointed out the danger resulting from ice in this area. (p. 25)

Ice warnings were first received and acknowledged 48 hours before the accident. Several other warnings were received before the collision. (pp. 26–28)

The master and the officers on watch were aware of the presence of ice in the vicinity of the ship and expected to reach it before midnight (the ship collided with the iceberg at 23:40). (p. 29)

The officers were confident of their ability to identify ice at a safe distance (2nd officer about the ice “I judged I should see it (the ice) with sufficient distinctness and at a distance of a mile and a half, more probably two miles.”). (p. 28)

The report mentions several conversations on the bridge between officers and the master about the ice and how likely it would be to see it under the given weather conditions. (pp. 28–29)

From tests made with a sister ship the report concludes that it would have required 37 seconds to change the course of the ship at an assumed speed of 22 knots. This means that the iceberg should have been sighted at a distance of approximately 450 meters or 500 yards off the ship (pp. 29, 30–31). The officer on watch had, however, expected that it would be visible from further away, which would have allowed him to decide what to do without time pressure and to execute all manoeuvres with a safety margin. When he spotted the iceberg, he acted instinctively and made two mistakes—he stopped the engine and gave it full astern while operating with the rudder at the same time.

The total capacity of the lifeboats was 1,178 persons. There were 3,560 life belts on board (p. 18). The report listed 2,201 persons on board—885 crew and 1,316 passengers (p. 23).

A second investigation was undertaken by the US Senate ( 1912 ). Although the accident happened in international waters, a large number of passengers were either US citizens or on their way to the USA. As such, the USA had a substantial interest in finding the possible causes of the accident. The two reports differ in scope and detail, but the facts listed in the US report are in line with the facts taken from the UK report. There are slight differences as far as some numbers, times, and other minutiae are concerned, just as the interpretations of the facts differ in the two reports.

2.2 Sinking of the Costa Concordia in 2012

As already mentioned, the investigation into the sinking of the Costa Concordia has not been concluded at the time of writing. We shall therefore remain with known facts, and refrain from speculating. The facts presented in this paper, unless specified otherwise, were provided in a presentation made by the Italian Maritime Investigative Body on Marine Accidents during the 90th Session of the IMO Maritime Safety Committee (MSC) on 18 May 2012 in London.

The ship left the port of Civitavecchia on 13 January 2012 at 1918 hours local time for a night trip to Savona. At around 2045 hours the ship hit an underwater rock in front of the Island of Giglio. The consequences of this were loss of watertight integrity of the hull and a subsequent massive flooding so that the engines shut down shortly afterwards. The ship returned (intentionally or unintentionally) to the island and capsized in shallow water. The following facts are known:

The voyage plan included a way point with a course alteration of more than 60° (from 278° to 334°) at a distance of 0.9 nautical miles (nm) off Punta della Torricella (Island of Giglio).

The master was on the bridge and took command to carry out the course alteration. He did not reduce the speed of the ship of 15–16 knots when he approached the island.

In order to change the course, the autopilot was switched off and manual steering was done. The course alteration manoeuvre resulted in a position off the track to pass the island, just about 0.3 nm south of Le Scole reef, right in front of the ship. Attempts to change the course of the ship further in order to avoid the charted eastern rock of Le Scole reef with a hard to starboard—hard to port rudder manoeuvre combination failed and the ship hit the eastern rock of Le Scole reef.

All electronic equipment on the bridge that could indicate risk of grounding was working.

Evidence from Automatic Identification System (AIS) records show that a similar close passing of the island was at least made once before, in August 2011 (Lloyd's List 2012 ).

The media have carried numerous discussions and speculations about the maneuvers prior to and after the collision with the rock. There has also been considerable debate about the evacuation of the ship as well as the timing of the information to the passengers and the emergency response forces ashore. Those aspects can only be reviewed once the accident investigation report has been published and are anyway not germane to the purpose of this paper. The question debated here is why people—and organizations—seem to underestimate the risks that exist in operating large ships with many passengers in such dangerous situations.

2.3 Similarities between the two accidents

As already mentioned, the technologies of 1912 and 2012 are so different that they hardly can be compared. Differences exist in the materials used, the principles of ship's constructions, the equipment available to assist the decision makers, and the technology to support navigation. Whereas the Titanic only had access to wireless radio communication, the Costa Concordia had all kinds of support and computer systems, including Global Positioning System (GPS), Electronic Chart Display and Information System (ECDIS), Automatic Radar Plotting Aid (ARPA), AIS etc. Yet despite these differences and despite the fact that the two accidents happened in different sea areas and under different circumstances, the “mechanisms” were basically the same—colliding with an underwater object that caused significant structural damage to the hull. A closer look at the two accidents reveals even further similarities:

Both masters were very experienced and had immaculate service records prior to the accidents. They had spent their entire professional life at sea without larger accidents.

Both masters were aware of the potential dangers, but felt that the risks were so small that they could easily be controlled.

In case of the Titanic, no officer on the bridge objected to the navigation of the ship. So far, no information has been published to show that officers on the Costa Concordia disagreed with the manoeuvres of the master.

In both cases, the shipping companies (White Star Line and Costa Crociere, respectively) either tacitly approved or even encouraged the masters' decisions to prioritize performance over safety.

Both accidents resulted into emergency situations for which the ships were not built (beyond design-base accidents). Both scenarios were also considered as being highly unlikely.

In both accident scenarios, difficulties during the evacuation occurred.

In the case of the Titanic, regulatory follow-up was initiated after the accident (International conference on safety at sea 1914 ). Several communications made by regulatory bodies after the Costa Concordia accident foresee that existing rules will be reviewed (IMO 2012 ; Cruise & Ferry Info 2012 ) and are likely to change. This type of response to accidents can be found in most domains.

The fact that there are so many similarities between two major maritime accidents a century apart raises the question of why these underlying factors remain when the technology has changed significantly during the same time. To understand this, it is necessary to look at the human and organizational factors of the accidents. But it is also necessary to consider how accidents are investigated and how the information produced by such investigations is used in the follow-up, by shipping companies and regulatory authorities.

As far as the latter is concerned, the traditional way of reacting to accidents is to insist on compliance to rules or procedures, to add new rules or procedures (and expect them to be followed), or to introduce new technology (Psaraftis 2002 ; Schröder-Hinrichs 2010 ). Hollnagel ( 2008 ) has discussed the extent to which the focus of an accident investigation may influence the results. In other words—that accident investigations seem to follow the What-You-Look-For-Is-What-You-Find principle and that solutions follow the What-You-Find-Is-What-You-Fix principle. In both cases, the outcome becomes limited by the unspoken assumptions of the investigation.

3 Discussion of the two accidents

In order to show the important similarities between the two accidents, we shall evaluate them from several perspectives that broadly can be labeled human factors issues. The term “human factors” today covers a multidisciplinary set of topics and perspectives, ranging from the design of equipment, interfaces, and tasks to selection, training, and organization of teamwork. The discussion in this paper will limit itself to the accepted role of human factors in safety, and consider the consequences of putting the focus on people at the sharp end and the blunt end, respectively.

As previously mentioned, the sharp end refers to the people who are directly involved in a specific activity, in our case the crew on the bridge. People at the sharp end are responsible for the hands-on control of what is going on; they are therefore also the people who directly experience the consequences if and when something goes awry. The blunt end refers to people who are separated from the activity by time or space, typically as designers, administrators, or managers of the activity in question. The distinction is used because it often is impossible to understand actions at the sharp end without reference to decisions made in the past with regard to, e.g., workplace design, technology, work schedules, manning, training, etc.

To illustrate the need of a human factors perspective, neither the crew on the Titanic nor on the Costa Concordia noticed that the risks increased by how they were sailing. This is sometimes alluded to by the analogy of “drifting” into failure (Rasmussen 1997 ). The failure to notice a changed situation can be explained in terms of individual factors such as complacency, in terms of factors relating to the social nature of the work such as authority gradient, or in terms of organizational influences. The focus of maritime accident investigations has in recent years moved from individual human factors to organizational influences, inspired by Reason ( 1990 ). This change has, however, not produced a deeper insight into the organizational contribution (Schröder-Hinrichs et al. 2011 ). Reason's “Swiss cheese” model has rather been interpreted in a linear way to suggest that causal factors in accident developments can be traced back to higher management levels. Although some classical maritime accident examples, such as the sinking of the Herald Of Free Enterprise in 1987 (Department of Transport 1987 ) or the fire on the Scandinavian Star in 1990 (Norwegian Official Reports 1991 ) have a considerable management contribution, the generalization that management responsibility is behind all accidents is misleading and with scarce empirical support.

While the influence of management in maritime accidents has been addressed by the International Safety Management (ISM) Code (IMO 1993 ), specific human factors are still not sufficiently considered. It was only in the recent revision of the International Convention on Standards of Training, Certification and Watchkeeping for Seafarers 1978 (STCW Convention) (IMO 2010 ) that some of the factors related to communication on the bridge were addressed in more detail. But there are other specific factors, such as the unanticipated side-effects of introducing new technologies on board or the constant struggle to find a balance between safety and economical considerations, the so-called efficiency-thoroughness trade-off (ETTO) (Hollnagel 2009 ). And even when such factors are considered, they are treated as if they were independent, i.e., one by one. However, these factors depend on each other and usually occur in combination with other factors, resulting in complex interactions.

A review of all possible human factors is beyond the scope of this paper. Instead we will concentrate on the issues mentioned above. These factors were involved in the Titanic and the Costa Concordia accidents, and can be found in a great number of other accidents. They are furthermore not limited to the maritime field, but show up in most other areas including health care, the nuclear industry, and aviation.

3.1 Authority gradient and its influence on communication

The term “authority gradient” refers to the distribution of decision-making and the balance—or imbalance—of authority and power in a group or organization, usually in relation to a specific type of situation. Although it is rarely considered by the maritime industry, it plays an important role in, e.g., health care or aviation. It is used to describe how easy or difficult it may be for someone with a lower authority to question or challenge somebody with a higher authority. The authority gradient is itself influenced by a number of other factors, such as education, social background, gender, age, professional roles, and perceived expertise (cf., Sasou and Reason 1999 ; Cosby and Croskerry 2004 ).

From the information provided in the accident investigation reports, it appears that the master of the Titanic was not challenged by his subordinates with respect to his assessment of the situation or the conduct of the ship. But the absence of documentation of a disagreement between the master and the officers does not mean that all the officers agreed that the overall risk of a collision with an iceberg was under control and that an iceberg close to the ship could be identified in time. The authority gradient may nevertheless have prevented individual officers from voicing their concerns.

It remains to be seen whether the master of the Costa Concordia was challenged by his bridge team when the ship approached the Island of Giglio. But there are several other maritime accidents where the authority gradient played a role.

One example is the collision of the US Coast Guard cutter Cuyahoga with the Santa Cruz II in October 1978 (US Coast Guard 1979 ). The master of the Cuyahoga misinterpreted the movement of the Santa Cruz II at night. He thought, he would overtake the vessel, although the ship was on a reciprocal course. The officers on the bridge realized that the Santa Cruz II was on a reciprocal course but did not question the orders given by the master, although it was clear that they would lead to a collision between the two ships. Another example is the grounding and subsequent loss of the tanker Böhlen in 1976 (Seekammer der DDR 1977 ). The Böhlen was sailing in the Atlantic towards Europe. During a transfer of the position of the ship from one sea chart to another, a mistake in the fix resulted in a chart position approximately 30 nm north of the real position. The radio officer used radio direction finders to estimate the position of the ship. He identified the deviation well in advance of the grounding. However, his comments were dismissed by the navigation officers because of the radio officer's lack of qualification. Other examples involving the authority gradient are, e.g., the grounding of the Green Lily in 1997 (Marine Accident Investigation Branch 1999 ; Manuel 2011 ) or the explosion and subsequent sinking of the Bow Mariner in 2004 (US Coast Guard 2005 ; Barnett 2005 ; Manuel 2011 ). In both cases, it was difficult for the people involved to question arrangements made by their superiors.

The navigation of ships has from a historical point of view always been characterized by semi military organizational structures and decision making by a single person in command. This may foster the development of a steep authority gradient. Although there are some sources that require collective agreement before taking a risk, such as the Rolls of Oléron in the 12th Century where article 2 requires the master to consult the crew before setting sails (Mukherjee 2002 , p. 31), instances where a collective bargaining about risk perception is suggested or required are rare.

3.2 Group think and the desire for harmony

The authority gradient is not the only factor that may hinder critical comments from crew members to decisions made by their superiors. Other factors are group think and the desire for harmony in a group (cf., Janis 1972 ; Hart 1991 ; Turner and Pratkanis 1998 ). When the Bow Eagle collided in 2002 with the fishing vessel Cistude (Bureau Enquêtes - Accidents/Mer 2003 ; Manuel 2011 ), the Cistude asked for help. However, the officer on watch wanted immediately to move away from the accident scene, as the collision had not been noticed by others on the Bow Eagle except the bridge team. He convinced the lookout to keep quiet about the accident. The lookout need not have felt threatened by the officer in charge of the navigational watch, but may have acted out of sympathy or as a good mate in a team. In the same way, the master of the Titanic may have benefited from a general group think of the bridge team who may have not wanted to become involved in open conflict. It remains to be seen if there was an analogous situation on the Costa Concordia.

It is notoriously difficult to overcome the natural desire for harmony in working environments. The people involved in a developing situation may be reluctant to challenge the assessments and decisions made by their colleagues unless categorical indications or alarms are presented by technology. The lack of effective interaction among crew members during the development of a critical situation may to some extent be mitigated by effective use of sophisticated technology. The introduction of new technology is, however, not without risks of its own, as discussed later.

3.3 Cognitive hysteresis—resistance to revising a situation assessment

The term cognitive hysteresis—or psychological fixation—describes the situation where people fail to revise their initial assessments in response to new evidence, particularly evidence that diverges from the expected (Woods et al. 2010 ). While the initial situation assessment may have been appropriate at the time it was made, the cognitive hysteresis means that neither the assessment nor the chosen course of action is revised even if an opportunity for that arises.

The collision of the Cuyahoga mentioned above can be seen as a case of cognitive hysteresis on the part of the master. Having been involved in earlier patrols with his ship on this river he may have experienced situations where he, while overtaking another ship on her starboard side, suddenly had to give way, when she wanted to turn to starboard in order, e.g., to enter a side-arm of the river. He may have been excessively influenced by this experience and therefore only paid attention to some of the position lights of the upcoming vessel, leading to the incorrect “recognition” that he was again overtaking a ship in an inconvenient navigational situation. He might have been so convinced by this wrong mental picture of the situation that it would have required some external questioning by his officers to force him to realize that the situation was different from what he assumed. A similar lack of critical voices in the case of the Titanic or the Costa Concordia may have contributed to a situation where the masters held on to an imprecise or incorrect picture of the situation.

3.4 Unanticipated consequences of new technology

Another reason for underestimating risks may be reliance on new technology. The Titanic was considered a masterpiece of naval architecture in 1912. This may have led to the belief that a collision with an iceberg could be survived and that the ship would stay afloat even with severe structural damage to the hull, in the same way as the Arizona in 1879 (Fry 1896 ) or the Knight Bachelor in 1897 (Board of Trade 1897 ). In 2012, the Costa Concordia was equipped with significantly better technology. The navigation equipment alone provided an accurate position of the ship at any time on the sea chart and also showed the predicted future positions given the current course and speed. In addition, the cruise line industry has for several years argued that the probability of such an accident was low or insignificant (IMO 2008a ). Trust in technology may in both cases have affected the attitude of the navigators of such ships.

New technology may often create a false sense of confidence, and thereby lead to an increase in the acceptance of risks. A classical example of that is provided by the collision of the Stockholm and the Andrea Doria in 1956 (Mattsson et al. 2003 ). The two ships sailed towards each other in dense fog with the assistance of radar. The Andrea Doria misinterpreted the intentions of the Stockholm and maneuvered in the same direction and the ships subsequently collided. The radar technology on board the ships did not prevent the collision but may actually have contributed to the accident by implying safety margins in fog that in reality were not there. Without this technology, the ships would likely have operated in a different way, although it cannot be known with certainty that the collision could have been avoided if radars had not been available. There are, however, a number of other “radar assisted collisions” in the 1960s and 1970s that confirmed that the introduction of radar created a new accident category (cf., Fricker 1973 ; Kemp 1973 ).

There are also examples where the information given by electronic devices is trusted blindly and never questioned. The Royal Majesty ran aground in 1995 (National Transportation Safety Board 1997 ), after the loss of the GPS position had gone unnoticed for several days. In the end, the ship was nearly 15 nm off its track, and even though a number of navigational marks had been missed by the ship, none of the officers on watch questioned the technology and the position. Inappropriate design meant that the display of the error indicator in the GPS receiver was so small, that it was easy to overlook it (Lützhöft and Dekker 2002 ).

While reliable technology is important for safe navigation and can be used to support a correct overall understanding of a specific traffic situation, humans unfortunately use and “abuse” the technology provided in various ways. New technology may also easily change the risk perception of officers on watch, and thereby end up defeating the purpose for which it was developed. Although there are countless examples of this in the human factors literature, it usually comes as a great surprise to equipment designers, who consistently fail to realize that there is a significant difference between work-as-imagined and work-as-done.

3.5 Organizational influences (latent conditions)

In the wake of accidents such as the meltdown in the nuclear power plants at Three Mile Island, the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger, or the capsizing of the Herald Of Free Enterprise, the notion of latent conditions as a result of unsuitable management decisions gained popularity (Reason 1990 ). This led to a new generation of accident causation models which described how latent conditions could undermine the safety features of a system and in combination with active failures result in accidents.

The discussion of these ideas had led to important maritime safety instruments like the ISM Code (IMO 1993 ) following the Herald Of Free Enterprise capsizing. In recent years, a debate has started as to whether this view of organizational factors is too narrow, since it tends to attribute all responsibility for accidents to management and leaves people at the sharp end with limited influence. While the ideas behind such concepts are understandable, and in single cases such as the Herald Of Free Enterprise possibly even valid, these considerations are in general too simple. It is easy to find examples where individual actions can lead to adverse outcomes even though the actions are not the results of management decisions. The common understanding of the way management involvement works is also too simple because it is based on a linear explanation of accident causation.

If the Titanic example is once again considered, the question of undue management influence was raised in the investigations. The UK report (Report of the loss of SS Titanic 1990 ) quotes on page 24 the procedures of the shipping company when first appointing masters to command. The masters received a letter which they had to sign and return. The letter stated that “You are to dismiss all idea of competitive passages with other vessels and to concentrate your attention upon a cautious, prudent and ever watchful system of navigation, which shall lose time or suffer any other temporary inconvenience rather than incur the slightest risk which can be avoided.”

But there was also a conflicting message from management. In the Titanic accident report, Lord Mersey, the Judge heading the investigation, commented on the performance of the master in the following manner (Report of the loss of SS Titanic 1990 , p. 30):

“Why, then, did the master persevere in his course and maintain his speed? The answer is to be found in the evidence. It was shown that for many years past, indeed, for a quarter of a century or more, the practice of liners using this track when in the vicinity of ice at night had been in clear weather to keep the course, to maintain the speed and to trust to a sharp look-out to enable them to avoid the danger. This practice, it was said, had been justified by experience, no casualties having resulted from it. I accept the evidence as to the practice and as to the immunity from casualties which is said to have accompanied it. But the event has proved the practice to be bad. Its root is probably to be found in the competition and in the desire of the public for quick passages rather in the judgement of the navigators.”

The two messages constitute a double-bind (Bateson 1972 ), i.e., a communication dilemma in which an individual (or group) receives two—or more—messages that are in conflict with each other. A similar dilemma can be found in the case of Costa Concordia, where the company advertised that the ship would sail a “touristy” sailing course close to land. The case is not simply that organizations (the blunt end) give one message—like “safety first”—but neglect to follow-up on it. The case is rather that organizations want to have their cake and eat it too, by emphasizing both safety and productivity. This creates a psychological and social conflict at the sharp end, where the outcome is uncertain. In this respect it should be mentioned that safety culture and how to achieve it in the shipping sector has been discussed for a number of years already (cf., Mathiesen 1994 ; Veiga 2002 ; Manuel 2011 ). However, further progress is needed.

3.6 Efficiency-thoroughness trade-off

In shipping operations, as in any other industry, time and resource constraints affect the day to day routines. The time and the measures taken to ensure safety operations have to be balanced with economical considerations in the commercial operation of a ship. Hollnagel ( 2009 ) refers to these as trade-offs between efficiency and thoroughness. The question is how thorough an operator can be in the performance of a duty and still also be considered as efficient—by himself/herself, by the social group, or by the company. The dilemma facing sharp end operators is that they are supposed to be efficient rather than thorough, except in cases where the outcome shows that they should have been thorough rather than efficient. Making these efficiency-thoroughness trade-offs is essential for the efficacy of overall performance but can also lead to accidents.

In the case of the Titanic, examples of “ETTOing” can easily be found. The Titanic was on its maiden voyage and the steam engines needed time to deliver their full performance (US Senate 1912 , p. 7). At the time of the collision with the iceberg, the ship still had almost two more days at full speed (roughly 1,000 nautical miles) ahead on its way to New York. Given the time lost due to the engine performance and given that the weather in the North Atlantic suddenly can change and cause further delays due to strong winds and currents, the master may have found there was no need to reduce the speed of the ship in a situation where he felt that the risks of ice in the area could be controlled. (Add to that the management pressure alluded to in the quotation from Lord Mersey.) Collisions with icebergs were not unusual accidents at that time, although they rarely resulted in loss of life. This may have contributed to underestimating the possible consequences of a collision with an iceberg as discussed above.

Another clear-cut illustration of the ETTO principle is the grounding of the Torrey Canyon in 1967 (Rothblum et al. 2002 ). In this case the master decided to revise the course alteration made by an officer, intended to steer clear from a dangerous area, and instead proceeded through that area in order to arrive with the ship on time. The desire to arrive in time with the ship has indeed often played a fatal role in accidents, such as Herald Of Free Enterprise in1987 (DoT 1987 ), Jan Heweliusz in 1993 (European Court of Human Rights 2005 ), Estonia in 1994 (Joint Accident Investigation Commission 1997 ), Sleipner in 1999 (Norwegian Official Reports 2000 ) or the MSC Napoli in 2007 (Marine Accident Investigation Branch 2008 ) and many others.

4 Maritime accident investigation and persistent human factors issues

The general concern in accident investigations is to find a cause, or a set of causes, both to explain what happened and as a basis for remedial actions. Accident investigations subscribe to a strong belief in causality—a causality credo—which can be formulated as follows: Adverse outcomes (accidents and incidents) happen when something goes wrong; adverse outcomes therefore have causes, which can be found and treated—and preferably eliminated.

Maritime accident investigations have since long been a good example of that. In 1838, a suggestion was made in the UK to establish courts of marine inquiry in order to investigate causes of shipwrecks, censor ship masters and owners, suspend licenses, reward acts of skill, humanity and courage and publish the outcomes of such inquiries. In 1860, a clarification was made that the objective of maritime casualty investigation was “not so much to punish anyone who may be at fault, as to prevent wrecks in the future”. Despite this clarification, part VIII of the 1876 Merchant Shipping Act (Boyd 1876 , p. 365) established a two-tier system of investigation, namely the preliminary investigation followed by a formal investigation headed by a judge, advised by specialist assessors, as in the case of the Titanic. The UK system is the basis for domestic legal provisions for maritime accident investigations in a number of countries. Although the objectives of accident investigations often are stated as being to support the overall system improvement rather than to focus on single individuals, the fact that they usually are carried out in front of a judge automatically introduces legal concepts of fault and liability. Under such circumstances it may be very difficult fully to acknowledge the complexity of factors involved in an accident, particularly if such factors are seen as indirect rather than direct.

Similar problems exist with the recommendations that follow investigations. For a long time, the preferred response to shipping accidents was to introduce new technical standards in order to provide the best possible support to navigating officers and thereby to reduce the probability of accidents. The complexity of factors involved in shipping operations has, however, for many years not only been underestimated but also been neglected in investigations and recommendations from such investigations therefore rarely take them into consideration (Ghirxi 2010 ; Schröder-Hinrichs et al. 2011 ). This leaves purely technical and/or administrative solutions which may fail to address the actual problems. In any case, the effectiveness of technical and administrative solutions does not stand on its own but depends on the human operators and the conditions that they are facing in their everyday work. This was finally recognized in International Maritime Organization (IMO) discussions following the capsize of the Herald Of Free Enterprise in 1987. However, it was not until 2010 that the new IMO Casualty Investigation Code (IMO 2008b ) pointed out that safety investigations should be a main priority for administrations. Specific guidance for human factor investigations are still under preparation. In the meantime, accident investigations very often seem to be constrained by the principles of What-You-Look-For-Is-What-You-Find and What-You-Find-Is-What-You-Fix (Hollnagel 2008 ).

The earlier discussed Cuyahoga accident demonstrates some of the interaction of the different human factors discussed here. The situational analysis of the master with regard to the maneuvering situation was inaccurate. A possible reason for that could be cognitive hysteresis as described above. Although some of the officers clearly were aware of the situation, his analysis was not challenged. There may have been a steep authority gradient that prevented this. It was, however, not until the master tried a local ETTO optimization by overtaking the assumed slower ship in an unusual—and again undisputed—maneuver, that the accident happened. It is this combination of events and actions that often can be found in large scale accidents. The actions and events may in themselves often be insignificant, like in the Torrey Canyon accident. However, in a complex system, such as shipping, they can unexpectedly combine in ways that can neither be predicted nor controlled by individual technical and administrative solutions.

It is increasingly acknowledged, willingly or reluctantly, that present day work environments on land, at sea, and in the air are dominated by complex socio-technical systems that defy time-honored methods and familiar ways of thinking. Two central issues are how to account for outcomes that are out of proportion to the initiating events—so-called non-linear outcomes—and how to describe outcomes that are emergent rather than resultant in the sense that they cannot be accounted for by component characteristics and cause-effect relations.

While the need to develop new methods to be able to deal with the current socio-technical complexity is beyond question, not all problems are due to rampant technological developments, to expanding system boundaries, or to ever tighter couplings among system functions. The comparison between the Titanic and Costa Concordia accidents show there are other common issues, then as now. Since the science of human factors only came into the world around or shortly after the Second World War, few of these issues could be named in 1912, but they were present nevertheless, as demonstrated by the examples given in this paper.

5 Summary and conclusions

Maritime accident investigations have traditionally looked for one or more distinct causes and tried to address them one by one, as if they were independent of each other. The near universal assumption, expressed by the causality credo , is that every effect has a cause, and that the cause usually can be determined to be a failure or malfunction of a “component”—be it technological, human, or organizational. According to this logic, if we can find and fix the failure or the malfunction, then the risk will be reduced or even eliminated and safety therefore increased.

The causality credo , however, limits the scope of investigations to concrete and tangible causes, but neglects a host of other factors that are less conspicuous and have a more indirect influence. As the comparison of the fates that befell the Titanic and the Costa Concordia however shows, accidents seem to happen for the same underlying human and organizational reasons even though they are separated by a century of improvements to technology and safety regulations.

In the wider perspective, the really important question is therefore not why these and many other ships have foundered, but rather why these reasons remain and why accident investigations and the reactions to them are more or less the same now as they were 100 years ago.

One explanation is that safety thinking, whether in the context of accident investigation or safety regulation, focuses on things that go wrong or could go wrong, such as near misses, incidents, and accidents. This corresponds to a definition of Safety-I as situations where little or nothing goes wrong (Hollnagel 2012a ). In Safety-I, the purpose of safety efforts is consequently to ensure that this condition is sustained and it is therefore sufficient to find the immediate and direct causes. The alternative perspective, called Safety-II, focuses on the situations of everyday work where things go right. In this case the purpose of safety efforts is to facilitate the performance adjustments that are necessary for everyday work to succeed, i.e., not only try to avoid things going wrong, but also try to ensure that they go right. This cannot be done without understanding how things happen, including the many human and organizational factors that determine how work is carried out, for example the authority gradient, group think, cognitive hysteresis, unanticipated consequences of new technology, latent organizational conditions, and the ubiquitous trade-offs between efficiency and thoroughness.

Another explanation is that it is far more convenient to deal with direct causes than with the indirect ones. It is first of all easier to propose concrete responses, whether they are of a technical or administrative nature, for instance improved technology or increased procedure compliance. It is also requires less investment of time and resources to address a clearly defined cause than to deal with a combination of factors and conditions—at least in the short run. The expected results are also assumed to be more concrete hence easier to evaluate, and happen without extensive delays.

The differences in the understanding of what safety is determine how accidents are investigated, and therefore also which causes are taken into consideration. If no one is looking for the human and organizational factors described in this paper, no one will find them. And if no one finds them, no one will do anything about them. Yet investigations of accidents in today's complex work environments cannot afford to look only at “component” malfunctions and failures. Actual safety improvements will not occur until we understand how functions depend on each other and at how seemingly subtle changes and performance variability can lead to out-of-scale outcomes (Hollnagel 2012b ).

Accident investigation has an important role to play in shaping the safety culture (IMO 2008b , Part I, Chapter 2.11). The question is to which extent the human factors and organizational issues described in this paper become accepted by investigators and used in the context of the IMO Casualty Investigation Code. Ghirxi ( 2010 ) identified an unwillingness of accident investigators to apply even Reason's model (Reason 1990 ), although it was specifically recommended in the previous IMO resolutions on casualty investigation (IMO 1999 ). Ghirxi's study, however, does not show whether the reluctance by investigators to take the academic concepts into consideration is due to perceived weaknesses or due to a deeper resistance towards academic approaches in general. It is hoped that the examples given in this paper and the supporting arguments will raise the awareness and importance of a systemic view on accident causation and lead it to be considered in the new guidance for maritime accident investigation currently under discussion in IMO.

So far, the public discussion following the Costa Concordia accident has mainly focussed on the master of the Costa Concordia. This reflects the social dynamics in risk communication described by Kasperson et al. ( 2003 ). It is, however, to be hoped that the discussions about this accident may become more system oriented once the accident investigation report is available. In the light of the IMO Casualty Investigation Code, the master is just a part of a wider system and it is the system that needs to be improved. Isolated discussions about single actors and single causes in a system, no matter how important they are, will not lead to sustainable system improvements. It is time for a fundamental change to the way we look at maritime accidents and to the understanding of how we can improve maritime safety by addressing human and organizational factors.

Barnett ML (2005) Searching for the root causes of maritime casualties—individual competence or organisational culture? WMU J Marit Aff 4(2):131–145

Article Google Scholar

Bateson G (1972) Steps to an ecology of mind: collected essays in anthropology, psychiatry, evolution and epistemology. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Google Scholar

Board of Trade (1897) No. 5606. Knight Bachelor (S.S.). Report and opinion of an enquiry into the cause of the collision of the British steamer Knight Bachelor with an iceberg, in lat. 42 N. and 48 W, held before H.W. Smith, R.N.R., Chairman of the Board of Examiners of Masters and Mates, at the Marine and Fisheries Office, Halifax, N.S., on the 2nd, 4th, and 5th August, 1897. Board of Trade, London

Boyd AC (1876) The merchant shipping laws. Stevens & Sons, London

Bureau Enquêtes - Accidents/Mer (2003) Abordage survenu au large de l'ile de sein le 26 aout 2002 entre le chalutier français Cistude (quatre victimes) et le navire-citerne (chimiquier) norvegien Bow Eagle. Secretariat d'etat aux transportes & a la mer, Inspection générale des services des affaires maritimes, Bureau enquêtes - accidents/mer (BEAmer), Paris.

Cosby KS, Croskerry P (2004) Profiles in patient safety: authority gradients in medical error. Acad Emerg Med 11(12):1341–1345

Cruise & Ferry Info (2012) Costa's new safety standards might partially become passenger ship industry policy. June, p 33

Department of Transport (1987) The Merchant Shipping Act 1894. mv Herald of Free Enterprise. Report of Court no. 8074. Formal investigation. HMSO, London

European Court of Human Rights (2005) Brudnicka and others v. Poland. Application no. 54723/00. European Court of Human Rights, Strasbourg

Fricker FW (1973) Three classic collisions. J Navig 26:299–310

Fry H (1896) The history of North Atlantic steam navigation with some account of early ships and shipowners. Sampson, Low & Marston, London

Ghirxi KT (2010) The stopping rule is no rule at all—exploring maritime safety investigation as an emergent process within a selection of IMO member states. World Maritime University, Malmö, PhD thesis

Hart P (1991) Irving L. Janis' victims of groupthink. Polit Psychol 12(2):247–278

Hollnagel E (2004) Barriers and accident prevention. Ashgate, Aldershot

Hollnagel E (2008) Investigation as an impediment to learning. In: Hollnagel E, Nemeth CP, Dekker SWA (eds) Remaining sensitive to the possibility of failure. Aldershot, Ashgate, pp 259–268, Resilience Engineering Perspectives, vol. 1

Hollnagel E (2009) The ETTO principle: efficiency-thoroughness trade-off: why things that go right sometimes go wrong. Ashgate, Farnham

Hollnagel E (2012a) Proactive approaches to safety management. The Health Foundation, London, Thought paper, May 2012

Hollnagel E (2012b) FRAM—the Functional Resonance Analysis Method. Modelling complex socio-technical systems. Ashgate, Farnham

IMO (1993) International management code for the safe operation of ships and for pollution prevention (International Safety Management (ISM) Code). International Maritime Organization, London, IMO document Res. A.741(18) adopted on 4 November 1993

IMO (1999) Amendments to the code for the investigation of marine casualties and incidents (Resolution A.849(20)). International Maritime Organization, London, IMO document Res. A.884(21) adopted on 25 November 1999

IMO (2008a) FSA—cruise ships: details of the formal safety assessment. International Maritime Organization, London, IMO document MSC 85/INF.2, dated 21 July 2008

IMO (2008b) Adoption of the code of the international standards and recommended practices for a safety investigation into a marine casualty or marine incident (Casualty investigation code). International Maritime Organization, London, IMO document Res. MSC.255(84), adopted on 16 May 2008

IMO (2010) Adoption of the final act and any instruments, resolutions and recommendations resulting from the work of the conference. International Maritime Organization, London, IMO document STCW/CONF.2/32, dated 1 July 2010

IMO (2012) Passenger ship safety provisions. International Maritime Organization, London, IMO document MSC 90/27, dated 14 February 2012

International Conference on Safety at Sea (1914) H. M. Stationary Office, London

Janis IL (1972) Victims of groupthink: A psychological study of foreign policy decisions and fiascos. Houghton Mifflin, Boston

Joint Accident Investigation Commission of Estonia, Finland and Sweden (1997) Final report on the capsizing on 28th September 1994 in the Baltic Sea of the Ro-Ro passenger vessel MV Estonia. Edita, Helsinki

Kasperson JX, Kasperson RE, Pidgeon N, Slovic P (2003) The social amplification of risk: assessing fifteen years of research and theory. In: Pidgeon N, Kasperson RE, Slovic P (eds) The social amplification of risk. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 13–46

Chapter Google Scholar

Kemp JF (1973) Behaviour patterns in encounters between ships. J Navig 26:417–423

Lloyd's List (2012) Exclusive: Costa Concordia in previous close call. 18 January

Lützhöft M, Dekker SWA (2002) On your watch: automation on the bridge. J Navig 55(1):83–96

Manuel ME (2011) Maritime risk and organizational learning. Ashgate, Farnham

Marine Accident Investigation Branch (1999) Report of the inspector's inquiry into the loss of mv Green Lily on the 19 November 1997 off the east coast of Bressay, Shetland Islands. Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions, Marine Accident Investigation Branch, London, Marine Accident Report 5/99

Marine Accident Investigation Branch (2008) Report on the investigation of the structural failure of MSC Napoli English Channel on 18 January 2007. Marine Accident Investigation Branch, Southampton, Report No. 9/2008

Mathiesen T-C (1994) Safety in shipping—an investment in competitiveness. In: BIMCO (ed) BIMCO Review 1994. BIMCO, Copenhagen, pp 56–58

Mattsson A, Fisher RE, Paulsen BG, Paulsen GW (2003) Out of the fog: the sinking of Andrea Doria. Cornell Maritime Press, Centreville

Mukherjee PK (2002) Maritime legislation. WMU Publications, Malmö

National Transportation Safety Board (1997) Grounding of the Panamanian passenger ship Royal Majesty on the Rose and Crown Shoal near Nantucket, Massachusetts June 10, 1995. National Transportation Safety Board, Washington

Norwegian Official Reports (1991) The Scandinavian Star disaster of 7 April 1990: Report of the Committee appointed by Royal Decrees of 20 April and 4 May 1990: Submitted to the Ministry of Justice and Police in January 1991, Government Printing Service, Oslo, Report NOU 1991 1:1 E

Norwegian Official Reports (2000) Hurtigbåten MS Sleipners forlis 26. november 1999. Government Printing Service, Oslo, Report NOU 2000:31

Psaraftis HN (2002) Maritime safety: to be or not to be proactive. WMU J Marit Aff 1(1):3–16

Rasmussen J (1997) Risk management in a dynamic society: a modelling problem. Saf Sci 27(2–3):183–213

Reason J (1990) Human error. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Book Google Scholar

Report of the loss of SS Titanic (1990) Reprint of the 1912 Investigation Report by the UK Wreck Commissioner. Adam Sutton Publishing, Gloucester

Rothblum A, Wheal D, Withington S, Shappell SA, Wiegmann DA, Boehm W, Chaderjian M (2002) Improving incident investigation through inclusion of human factors, United States Department of Transportation Publications & Papers. US Department of Transportation, Washington

Sasou K, Reason JT (1999) Team errors: definition and taxonomy. Reliab Eng Syst Saf 65(1):1–9

Schröder-Hinrichs J-U (2010) Human and organizational factors in the maritime world—are we keeping up to speed? WMU J Marit Aff 9(1):1–3

Schröder-Hinrichs J-U, Baldauf M, Ghirxi KT (2011) Accident investigation reporting deficiencies related to organizational factors in machinery space fires and explosions. Accid Anal Prev 43(5):1187–1196

Seekammer der DDR (1977) Havariespruch in dem Havarieverfahren MT “Böhlen” - Sinken vor der französischen Küste am 14.10.1976, Seekammer der DDR, Rostock. Havariespruch 9/77

Turner ME, Pratkanis AR (1998) Twenty-five years of groupthink theory and research: Lessons from the evaluation of a theory. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 73(2/3):105–115

US Coast Guard (1979) USCG Cuyahoga, M/V Santa Cruz II (Argentine); Collision in Chesapeake Bay on 20 October 1978 with loss of life. US Coast Guard, Washington, US Coast Guard Document Report No. USCG 16732/92368

US Coast Guard (2005) Explosion and sinking of the chemical tanker Bow Mariner in the Atlantic Ocean on February 28, 2004 with loss of life and pollution. Washington: US Department of Homeland Security, US Coast Guard

US Senate (1912) Titanic disaster. Government Printing Office, Washington, 62nd Congress, 2nd Session, Report no. 806

Veiga JL (2002) Safety culture in shipping. WMU J Marit Aff 1(1):17–31

Woods DD, Dekker S, Cook R, Johannesen L, Sarter N (2010) Behind human error. Ashgate, Farnham

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Maritime Risk and Safety (MaRiSa) Research Group, World Maritime University, Malmö, Sweden

Jens-Uwe Schröder-Hinrichs & Michael Baldauf

Center for Quality Improvement, Middelfart, Denmark

Erik Hollnagel

University of Southern Denmark, Odense, Denmark

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Jens-Uwe Schröder-Hinrichs .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Schröder-Hinrichs, JU., Hollnagel, E. & Baldauf, M. From Titanic to Costa Concordia—a century of lessons not learned. WMU J Marit Affairs 11 , 151–167 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13437-012-0032-3

Download citation

Received : 19 June 2012

Accepted : 15 August 2012

Published : 04 September 2012

Issue Date : October 2012

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13437-012-0032-3

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Maritime human factors

- Accident causation

- Maritime accident investigation

- Maritime safety

- Socio-technical systems

- Costa Concordia

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

M/V Costa Concordia accident

Related Papers

Michael Baldauf

Jonathan Earthy

The paper presents a systematic re-analysis of the Costa Concordia incident using the domains of Human Factors Integration (HFI) completed by undergraduate naval architects. The importance of the human element in the passenger ship industry, from the design stage of a ship to the end of its operational life, has developed through time. Human element considerations are becoming increasingly significant as a tool for creating efficient and safe working environments in the shipping industry. The area of passenger ships is particularly important in the understanding of the human element, due to the increased level of complexity of human interaction with the ship. The work was carried out in collaboration between Lloyd’s Register and Southampton Marine and Maritime Institute of the University of Southampton. An applicable understanding of the human element topic was developed using textbooks, public bodies of information and EU project HCD training. Methodologies used by investigative bo...

Global Journal of Researches in Engineering

Julius O Anyanwu

Ocean Engineering

Dracos Vassalos

Paola Di Maio

Abstract: This paper introduces core principles that define a 'socio-systemic analysis' of a disaster', with particular emphasis on the role of information, communication and decision-making, and discusses their application to the recent sinking of the Costa Concordia, concluding with some lessons learned and recommendations. Keywords: socio-systemic approaches; risk mitigation; citizen preparedness; Costa Concordia NOTE, THIS PAPER IS A DRAFT

Il diritto marittimo

Maria Luisa Chiarella

Helen Sampson

2015 2nd International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Disaster Management (ICT-DM)

12th International Conference on the Stability of Ships and Ocean Vehicles (STAB 2015)

RELATED PAPERS

Mathematics Magazine

Angel Plaza

The Brain & Neural Networks

Hiroyoshi Miyakawa

Spectrochimica acta. Part A, Molecular and biomolecular spectroscopy

Water Resources Research

Lifetime Data Analysis

Per Andersen

Zbornik rezimea II, Drugi međunarodni naučno-stručni skup Umetnost i obrazovanje

Teodora Peng

National Journal of Community Medicine

Rujee Rattanasathien

Ralph Gottschalg

Colección Transitoria

Nuno Gonçalves

Annals of Saudi Medicine

Wasil Jastaniah

Thin Solid Films

Tetsuo Soga

CHEST Journal

Erick martinez

Health Psychology Report

Sajjad Rezaei

Willbert Fialho

Journal of Cleaner Production

Lukas Andel

Journal of General Internal Medicine

Sylvie Perreault

American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology

Robert Sokol

Le français aujourd'hui

catherine canaveilles

gfhg hgjhjh

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Lessons from the Costa Concordia: A Case For Company Values

by Jesse Lyn Stoner | 30 comments

Why didn’t they know?