- Open access

- Published: 07 February 2023

A novel approach to frontline health worker support: a case study in increasing social power among private, fee-for-service birthing attendants in rural Bangladesh

- Dora Curry ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-9418-1548 1 , 2 ,

- Md. Ahsanul Islam 1 ,

- Bidhan Krishna Sarker 3 ,

- Anne Laterra 1 &

- Ikhtiar Khandaker 1

Human Resources for Health volume 21 , Article number: 7 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

2232 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Expanding the health workforce to increase the availability of skilled birth attendants (SBAs) presents an opportunity to expand the power and well-being of frontline health workers. The role of the SBA holds enormous potential to transform the relationship between women, birthing caregivers, and the broader health care delivery system. This paper will present a novel approach to the community-based skilled birth attendant (SBA) role, the Skilled Health Entrepreneur (SHE) program implemented in rural Sylhet District, Bangladesh.

Case presentation

The SHE model developed a public–private approach to developing and supporting a cadre of SBAs. The program focused on economic empowerment, skills building, and formal linkage to the health system for self-employed SBAs among women residents. The SHEs comprise a cadre of frontline health workers in remote, underserved areas with a stable strategy to earn adequate income and are likely to remain in practice in the area. The program design included capacity-building for the SHEs covering traditional techno-managerial training and supervision in programmatic skills and for developing their entrepreneurial skills, professional confidence, and individual decision-making. The program supported women from the community who were social peers of their clients and long-term residents of the community in becoming recognized, respected health workers linked to the public system and securing their livelihood while improving quality and access to maternal health services. This paper will describe the SHE program's design elements to enhance SHE empowerment in the context of discourse on social power and FLHWs.

The SHE model successfully established a private SBA cadre that improved birth outcomes and enhanced their social power and technical skills in challenging settings through the mainstream health system. Strengthening the agency, voice, and well-being of the SHEs has transformative potential. Designing SBA interventions that increase their power in their social context could expand their economic independence and reinforce positive gender and power norms in the community, addressing long-standing issues of poor remuneration, overburdened workloads, and poor retention. Witnessing the introduction of peer or near-peer women with well-respected, well-compensated roles among their neighbors can significantly expand the effectiveness of frontline health workers and offer a model for other women in their own lives.

Peer Review reports

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) for 2030 target reducing the Maternal Mortality Ratio to 70 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. Increased availability of skilled birth attendants (SBAs) is well established as one essential ingredient of reducing maternal mortality and is a primary indicator for documenting progress in this area [ 1 , 2 , 3 ]. Within a system-wide approach to improving maternal health outcomes, universal availability of skilled birthing care is one critical element of achieving progress on this crucial SDG [ 5 , 6 , 7 ]. The WHO Global Strategy for Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030 calls on countries to increase investment in frontline health workers and explore new ways to optimize health service expertise [ 8 ].

Expanding the health workforce to increase the availability of SBAs presents an opportunity. The role of the SBA holds enormous potential to transform the relationship between women, birthing caregivers, and the broader health care delivery system. This paper will focus on the community-based skilled birth attendant (SBA) role and its transformative potential, using a novel approach to SBAs, implemented in rural Sylhet District, Bangladesh, as an illustrative example. The introduction of diverse processes, like this one, to increase the uptake of basic skilled birthing care can play an essential role in improving coverage with skilled birthing attendants. In addition, insights from such new approaches to financing and supporting frontline health workers can contribute to health workforce expansion and quality improvement in health areas beyond safe delivery.

The Skilled Health Entrepreneur (SHE) model developed a public–private approach to developing and training a cadre of SBAs. The program focused on economic empowerment, skills building, and formal linkage to the health system for self-employed SBAs among women residents. This model shifts the view of community-based birth attendants from one of a substandard, stopgap force extender to one of a unique class of skilled providers. The program invests the SHEs with income, autonomy, and external professional recognition. Creating a cadre of providers of similar socioeconomic status and culture to clients enhances the value of the SBA and her services in her clients' eyes.

The Sumanganj District of Bangladesh provides a valuable context to explore these issues in several ways. Not only does the area experience a critical gap in the availability of health care service providers, but a market also exists for fee-for-service health care, as community members are already accustomed to seeking care or unreliable quality from often unskilled private providers due to the gap in the availability of providers in public facilities. In addition, an established cadre of community-based skilled birth attendants already existed, but was underutilized due mainly to inadequate supervision and low community awareness of their capabilities. Finally, women faced barriers to seeking delivery services at facilities due to social norms and religious practices [ 9 ].

Other models exist with some similarities. For example, this model is similar to the Shasthya Shebika (SS) approach. The SHE and the SSs are selected from the community, provided training and supervision, provided community-based services, and rely on their activities to earn compensation. The distinctive element of the SHE approach is that the SHEs charge for their services directly on a fee-for-service basis. SSs receive a financial incentive from relatively small mark-ups of resale health-related products provided or subsidized by a sponsoring organization such as an INGO or the MOH. This feature also sets the SHE model apart from similar models in other countries, like kaders’ posyandu in Indonesia or the LiveWell model in Zambia [ 4 ].

This paper will first present an overview of factors influencing the uptake of skilled birthing care and then describe the SHE model and its transformational potential. The SHE model comprises a cadre of frontline health workers in remote, underserved areas with a stable strategy to earn adequate income and are likely to remain in practice in the area. They can provide high-quality basic clinical skills and access to higher care. The community and the health system recognize them as legitimate. In addition, they are female, come from the same geographical, and cultural background as their clients, and are closer to their clients' socioeconomic peers than most other health workers.

These features of the SHE model can potentially increase clients' uptake of skilled birthing services and contribute positively to social and gender dynamics. Selecting SBAs from among women within traditionally underrepresented and marginalized communities ensures that they have networks, social connections, capital, and a desire to continue building a life there. Designing SBA interventions that increase their power in their social context could expand their economic independence and reinforce positive gender and power norms in the community, addressing long-standing issues of poor remuneration, overburdened workloads, and poor retention.

These shifts could also enhance the perception of quality and accessibility among clients and contribute more to women’s agency. This model amplifies and gives greater weight to client perception and builds on frontline providers’ and clients’ agency, making it more robust in challenging settings, more acceptable to clients, and more sustainable than other options.

This paper is a descriptive exercise depicting a novel intervention in detail. A selective review of relevant literature provides an overview of maternal health strategies to improve skilled birth attendant availability and skill. The literature review included both peer-reviewed publications and "grey" literature. The project description draws on an in-depth desk review of project documentation. The desk review covered the project proposal, routine project reporting covering supportive supervision findings, training materials, activity logs, and internal assessments; midline and end-line reports; and journal articles published on program data. Program monitoring and evaluation data included in the review covered project outputs such as health services delivered, commodities sold, community events conducted, and project outcomes such as the percentage of the coverage area accessing critical maternal and child health services.

International calls for more significant investment in skilled birthing care underestimate the complexity of women's needs and preferences and providers' needs and preferences [ 7 ]. To maximize the impact of such investments, health worker support interventions must offer a specific pathway to address the unique challenges of a range of women's preferences [ 11 ]. Women's preference for birthing care that is convenient, respectful, or culturally congruent may overshadow clinical quality, as defined by technical experts, in their care-seeking.

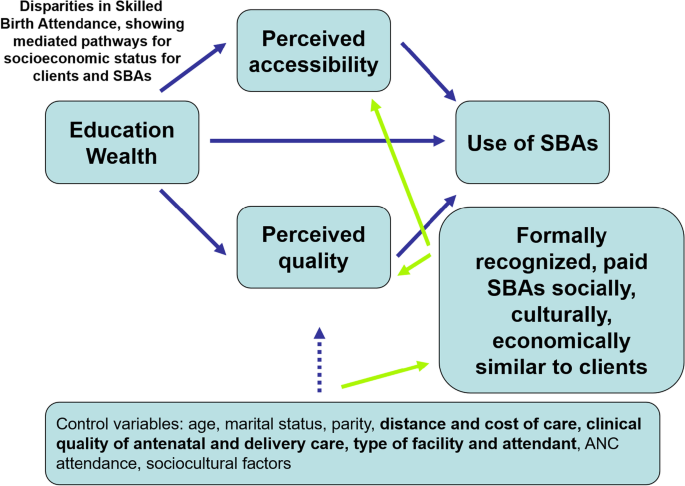

Afulani and Moyer proposed a framework that includes perceived need, accessibility, and quality as three factors affecting the uptake of skilled birthing care [ 12 ]. The critical insight their analysis contributes model is the influence of client perception on their decisions about seeking services. Distinguishing between perceived quality and accessibility, on the one hand, and clinical quality and distance to care, on the other, highlights the connection between client experience and whether a woman chooses skilled birthing care or not. Many factors affect perceived and actual quality and accessibility, such as service cost, quality monitoring, and the governance environment for financing and regulation. This discussion will use the concepts of perceived accessibility and quality, as distinct from objectively measured accessibility and quality, as a framework to consider the influence of the social context for the SHE role and its influence on women's uptake of services and gender and power dynamics.

Perceived accessibility

In Bangladesh and globally, rural areas face a more limited supply of providers and more significant challenges to ensuring high-quality, respectful care among providers [ 5 ]. The difficulty in improving provider coverage in underserved areas and the prevalence of disrespectful care is well-documented and persistent [ 11 , 13 , 14 ].

The considerable body of evidence on frontline health workers (FLHWs) demonstrates that fundamental issues like adequate, regular pay and safe working conditions are essential prerequisites to maintaining a successful frontline cadre of health workers [ 15 ]. (The term frontline health worker encompasses community skilled birth attendants, midwives, nurses, and physicians) [ 15 ]. Recruitment and retention of midwives, nurses, and physicians through financial incentives and other added compensation are common strategies for a geographic redistribution of skilled providers [ 1 , 16 ]. Unfortunately, these efforts have failed to identify a stable solution to the adequate supply of providers in underserved areas [ 17 ].

While additional factors undoubtedly influence the difficulty of attracting providers in remote areas, the inability to earn an adequate, stable income is critical [ 18 , 19 , 20 ]. Solutions that rely on unpaid or underpaid lay health workers in the community are not viable [ 7 ] and are not sure to improve perceived accessibility.

Perceived quality

The second mediating pathway considered here—perceived quality—is even more complex in its relationship to the uptake of services; the WHO acknowledged in 2014 guidelines on preventing pregnancy-related morbidity and mortality that respectful care still defies definition [ 21 ]. Researchers have identified involving women in their care and preparing a supportive environment that supports the woman's choice of companionship as a crucial element of respect [ 22 ]. In addition to being a fundamental right, respectful care significantly affects whether and where women seek care [ 23 ].

Factors like distance, lack of ancillary services, and desire for a cesarian section affect women's choice to give birth outside a facility. Avoidance of care that does not meet the standards for respectful care is also a significant driver for opting for non-facility deliveries [ 21 , 24 ]. In response to disrespectful care, women frequently seek care from traditional birth attendants and deliver at home [ 25 ].

Simply ensuring an adequate number of providers practicing in underserved areas will not adequately address the challenge of ensuring equitable access to maternity care that is both skilled and respectful [ 13 ]. Underlying factors increasing the likelihood of receiving disrespectful maternity care include caste, class, race discrimination, harmful gender norms, and social status. Strategies that incentivize providers from elsewhere to practice in underserved areas may increase the availability of providers. However, they may not increase perceived accessibility or respectfulness of care if newly recruited providers are more urban, of higher social status, or of different ethnic or language groups than their clients, which is likely.

Approaches to improving perceived quality and accessibility

Approaches to improving quality in ways valued by women are a critical need. For example, an intervention in Afghanistan that prioritized cultural compatibility in underserved areas by working with regional midwifery training centers found high satisfaction among midwives and their clients [ 27 ]. They may enhance the attractiveness of the service to individual clients by marrying clinically high-quality care with respectful, culturally congruent care.

An alternative approach must also establish a mechanism to ensure sustainable financing to ensure adequate provider income in underserved areas and facilitate a respectful relationship between providers and clients. One widely employed strategy to address the need to pay FLHW is to rely on a cadre of "volunteer" community-based providers. A risk in designing programming to extend access to health services is that the FLHW/CHW role may shift responsibility, work burden, and even financial contributions onto FLHWs/CHWs as individuals. For example, Schaaf et al. [ 28 ] observe that targeted vertical programs relied heavily on volunteer or minimally compensated community health workers to extend the program's reach. Closser and Maes discuss the "appropriation" of the role of the CHW. In these situations, the scope of duties and time commitment demanded of "volunteer" CHWs far exceed the typical expectations of a volunteer role [ 29 ]. Over-reliance on these predominantly female, lower-status cadres can decrease their effectiveness and undermine their impact among their social peers in the community as models of women respected and compensated for critical health services.

Skilled Health Entrepreneurs: a new approach

The Skilled Health Entrepreneurs Footnote 1 (SHE) model emerged from a collaboration between CARE International in Bangladesh, Bangladesh's Ministry of Health, and other partners. This coalition proposed creating a sustainable system to ensure SBA services are available in the remote, underserved rural Sunamganj District in the Sylhet Division, the northeast region of Bangladesh. Skilled providers were scarce in government facilities for at least two significant reasons. The cost of staffing many small clinics in remote locations can pose a substantial obstacle to the health system because of the high per-beneficiary cost for staffing in sparsely populated areas [ 30 ]. The government facilities struggled to retain those health workers they successfully recruited in the few rural facilities they could support [ 30 ]. Residents were accustomed to seeking delivery care from untrained private birth attendants [ 31 ]. The robust market for private traditional birthing care signals a gap in publicly provided services, in quality, quantity, or both. While the care provided by traditional birth attendants might not have met clinical quality standards, it was providing value to clients, potentially through convenience and culturally appropriate, respectful care.

The SHE model proposed increasing the availability of high-quality care and stabilizing access to care from SHEs by selecting residents of the area. As community members, they were less likely to leave the site and more motivated to improve health outcomes for those giving birth in their areas. With support from program staff, they also negotiated a standardized, sliding-scale fee schedule that allows them to continue generating revenue independently while ensuring low-income women can access their services [ 5 ].

The program design included measures to increase the capacities of the SHEs in ways beyond the traditional techno-managerial training and supervision in technical skills, such as growing and controlling their earnings and expanding their professional skills. The program intended to support women from the community, as social peers of clients and long-term residents, in becoming recognized, respected health workers linked to the public system while protecting their livelihood and improving quality and access to maternal health services [ 32 ] This paper will describe the SHE program's design elements to enhance SHE empowerment in the academic literature on social power and FLHWs.

Hossain, et al. [ 5 ] described the Skilled Health Entrepreneur program. The project's purpose was to provide clients with the option of a maternal health service provider that meets clients' needs and preferences. Women in the community preferred traditional birth attendants because they were available outside of business hours, accepted non-monetary payments, and shared social norms and beliefs [ 5 ]. The SHE program provided training to fellow community members so that women could receive services from their trusted, culturally congruent providers while ensuring that services offered were safe, high-quality, and linked to referrals for complications.

The project included five central interventions: selection and training of private birth attendants, social entrepreneurship capacity building, community engagement to establish the new cadre in the community, linkages to quality monitoring and referral facilities, and mechanisms to bolster the community's financial support of the program's activities. The program selected participants by inviting applications and conducting interviews and written exams. Women aged 25 to 40 years with at least ten years of schooling were eligible to apply. Over the 5-year life of the project, 319 completed the training.

The project delivered 3 months of training in health service and promotion. The clinical and health promotion training prepared SHEs to support a comprehensive maternal and child package, including antenatal care, assistance in uncomplicated deliveries, postnatal and newborn care, referral for complications, family planning counseling, short-term family planning method provision, and referral. The program used MOH training materials and trainers based on WHO standards. The program also linked SHEs with community support groups, community health workers, government health facilities, and supervisors. See Hossain et al. [ 5 ] for more details on the program in general. Once SHEs were prepared to offer services, the program provided ongoing supervision and professional development, including mobile skill labs and advancement opportunities to serve as trainers for incoming new SHEs.

The program also coordinated an alignment between municipal authorities, the health department, and the SHEs. As a result of CARE's coordination, the Health Department provided SHEs with an ongoing supply of health commodities, such as iron folate tablets, soap, and misoprostol, and refresher training. The SHEs charged clients on a sliding scale negotiated by the local government and community representatives. Prices paid were independently monitored periodically. Program staff collaborated with local leaders to explore mechanisms to extend care to the lowest wealth quintile care free of charge.

Over the project's life, SHEs accomplished 47,123 skilled deliveries and dispensed 2.7 million folic acid tablets. As of the end of the program, the median monthly earnings of the SHEs was 5000 BDT (67 USD), compared to 1500 BDT (20 USD) at the beginning of the program. SHEs are formally linked with 136 community clinics and 29 union councils on health and family welfare [ 33 ]. A mid-term analysis found that women in the coverage area were more than twice as likely to have delivered with a skilled birth attendant present at their most recent childbirth than at the beginning of the program [ 5 ]. The end-line assessment conducted in 2018 demonstrated significant achievements. The percentage of women using a skilled attendant during birth increased from 13.4 to 37.4% in the intervention area compared to 21.4% to 35.8% in a comparison district. Neonatal, infant, and under-five mortality rates all showed similar improvement [ 33 ] (see Table 1 ).

Compensation: financial and marketing skills building

One of the intervention arms most directly related to an increase in SHEs' social power focused on building their capacity to earn an adequate income. SHEs developed two potential sources of revenue: direct fee-for-service charges for maternal health services and the sale of health-related products. SHE revenue was not the sole source of household income, however. According to the program’s intake questionnaire administered to SHEs, most SHEs have some additional household income from another adult earner, and some may have had other sources of revenue as individuals unrelated to SHE duties. In addition, SHEs may compete with other providers of similar goods and services. Including income as an element of SHE empowerment should not be considered a comprehensive economic analysis but rather one of the multiple components influencing SHEs' social power (Fig. 1 ).

Mediating pathways in uptake of skilled birthing care

The program facilitated a market analysis process with the SHEs. The intervention included a 2-day social entrepreneurship capacity-building workshop drawing on a market analysis of the local market and developing business plans. The workshop covered targeting their service offerings and minimizing conflict with untrained traditional birth attendants. The SHEs received coaching from facilitators skilled in entrepreneurship to determine their potential clients' market size and characteristics. They developed individual business plans targeted to their communities, including outreach to potential clients. The project also conducted promotional and marketing activities ranging from health awareness days to stakeholder meetings to print, video, and media outreach. Another program element connected the SHEs to a supply chain of saleable commodities, such as non-prescription medicine, nutritional supplements, and baby care articles, at wholesale prices. The SHEs then resold these items at a small profit [ 30 ].

Professional engagement and community recognition

Other project elements contributed to SHEs' agency and external recognition by enhancing their recognition as valuable contributors to the community by authorities outside their homes. CARE's training to the SHEs earned them accreditation by the Bangladesh Nursing Council as a community skilled birth attendant, a professionally recognized designation in Bangladesh [ 32 ]. The professional development and skills-building component included coaching by nurses and physicians and organized rotations for the SHEs in healthcare facilities. These inputs conferred legitimacy and status on previously marginalized traditional providers.

Also, the project facilitated negotiation among the SHEs, the local municipal authorities, and the closest primary healthcare facility to establish a formally recognized role for the SHEs. This process set the sliding-scale fee structure discussed above. These negotiations afforded the SHEs recognition as accredited community midwives and secured support from local and neighborhood leaders to provide safe, clean space to perform services and accompaniment on travel to remote locations for home deliveries. The program developed a Memorandum of Understanding between the SHEs and the union parishads and negotiated specific budget line items in UP budgets to supervise the SHEs (These line items did not cover SHE remuneration.)

The formal recognition of their authority and value afforded them greater personal power in negotiating with family and community members about their mobility and control over resources. The provisions for their security removed the threat of violence, stigma, and harassment that could otherwise have accompanied their professional activities.

Agency: personal power to act

A third pillar of the program's approach to empowering SHEs was to build their sense of agency on an individual level. Program activities included group planning sessions among SHEs for the SHEs to engage with each other (As each SHE worked in a different neighborhood geographically, the risk of competition among SHEs was minimal). Also, program facilitators worked one-on-one with SHEs, identifying what changes could further develop their businesses [ 34 ]. For example, when a regular review revealed that one SHE was not earning as much revenue as targeted, program facilitators examined the factors affecting her ability to make money through her work. They found those factors to include a lack of family support and insecurity when visiting clients in remote locations. The action plan included family support for childcare, introductions to community members, and expanding the products she could sell to generate revenue. In the end, her revenue well exceeded her target [ 34 ].

Limitations

The primary limitation of this discussion is that it is a purely descriptive exercise. A deeper examination of the SHE program provides insight into where and how the SHE approach may be broadly relevant. However, the merit of the approach cannot be demonstrated without empirical data analysis. Further research should cover both the causal pathway and the ultimate outcomes of the model.

Also, context presents a dilemma in this approach. One of the keys to the success of the SHE model was its careful observation of the factors driving women's choices in obtaining birthing care in this setting. The participatory design process allowed for significant tailoring to the market forces and client preferences unique to Sylhet District in rural Bangladesh. Notably, birthing care from traditional birth attendants was in demand before the SHE program and was an essential prerequisite. This demand for birthing care may be necessary for this model to be helpful.

According to Renfrew, et al., any comprehensive solution to introducing and supporting an influential health worker cadre must include minimum educational requirements and processes to ensure training, licensure, and regulation and be systematically integrated into the health system [ 7 ]. The SHE program met those criteria and improved birth outcomes. The SHE successfully established a private SBA cadre that enhanced their social power and technical skills in settings challenging to access through the mainstream health system. The SHE model stands out from many adopted globally for this purpose, such as Ethiopia's Women's Development Army and Nepal's Female Community Health Volunteers [ 29 , 35 ]. The SHE model dedicates concerted efforts to enhance women's decision-making authority, status in their work lives, and economic independence.

Witter (2017) cite concrete measures to address gender barriers as an essential element of building a stable health workforce suited to meet the needs of vulnerable populations [ 36 ]. In the SHE program, recognizing the SHEs as sanctioned health service providers legitimizes their status in the community. As community members before receiving SHE training, the SHEs are more likely to be rural, less educated, of marginalized ethnic ups, and lower status than most mainstream service providers. The introduction of peer or near-peer women with well-respected, well-compensated roles among their neighbors may have a powerful effect on other women and offer a model for their lives in different fields.

Focusing on enhancing the SHEs’ agency, voice, and well-being is necessary for this transformative potential. Asking a traditional birth attendant to assume more work for little or no money may increase the burden of unpaid labor on her and also reinforce existing harmful power relations ( 28 ). Calling on CHWs to provide services with no guarantee of compensation and refer to facility-based care providers reinforces the notion that it is her feminine duty to care for her neighbors and is more naturally caring and motivated. The SHE model structurally counters those harmful notions. Instead, the SHE model reinforces the perception that the caretaking work, often performed unpaid, usually by women, is worthy of the respect and economic investment of the community.

The importance of class, caste, and race in these power relations also influences the SHE's role. SHEs are more likely to be of lower status on several criteria, such as wealth and education level, than female FLHWs with more training and authority, such as nurses and female physicians [ 37 ]. Part of the transformative power of a model like the SHEs is that they are women from the same community and background and have less elite status otherwise. Services offered at the site preferred by the client by a social near-peer coach in prioritizing client-centered care communicates a high value placed on the client's preferences [ 36 ].

The sustainability of such approaches is a crucial element of any potential for long-term success or expansion of the SHE model and similar interventions. The fundamental sustainability strategy rests on market forces. The SHEs’ ongoing presence depends on their continued ability to provide services and charge for them. The SHEs could continue earning a substantially increased income from their service provision by the end of the program. The program phased out any direct financial support to the SHEs well before the program concluded. Fundamentally the sustainability strategy is for the SHEs to continue to cost-recover for their services, whether from private clients or through reimbursement from public payers for those unable to pay.

The sustainability of additional support activities remains challenging in at least two ways. First, supervision and entrepreneurship support was provided by grant funding. Supportive supervision and in-service training would require additional approval and investment from health authorities or elsewhere. A combination of health and other agencies at multiple levels (municipal, district, and national) could provide the moderate additional oversight needed to assure quality at a much lower cost than alternatives like providing salary support to community-based SBAs or extending the availability of facility-based SBAs. Secondly, ensuring sustainable financial resources to ensure access to care for lower-income families is a critical challenge for the sustainability of this model. Municipal budgets and community savings groups contributed funding to allow the SHEs to cost-recover services provided to mothers unable to pay during the program. Still, those arrangements were difficult to formalize and vulnerable to changes in budget allocations. Allowing the SHEs to receive reimbursement for skilled delivery services provided outside the facility would be one option for ensuring sustainable financing for SBA services for lower-income clients.

Taken within the growing body of scholarly work demonstrating the potential benefit of supporting positive gender norms and power dynamics among frontline health workers, these findings suggest some recommendations for health service delivery policy and practice:

Support robust investment in financing mechanisms to ensure adequate financial compensation for community health workers, especially predominantly or exclusively female cadres.

Build meaningful commitment to including community-based FLHW cadre in decision-making and planning within the health system through binding agreements among government and private sector stakeholders at local, as well as district and national, levels.

Include support in addressing gender-related barriers to paid work among female frontline health workers in supervision protocols and intervention design (Such support may include items in the SHE approach like coaching in negotiating social norm barriers among families and training on professional business skills such as public speaking and financial management.)

In addition, an assessment of the SHEs' experience and assessing health outcomes and social relations in the broader community can provide insights into the social role she fills. Understanding the effect of the SHEs’ agency on the women in the communities they serve is vital for the effective implementation of recommendations in other contexts.

Building on these learnings and implementing these recommendations could contribute to expanding women’s access to safe, acceptable care and strengthening social norms supportive of women in influential, professional roles.

Availability of data and materials

N/A (No datasets were presented in this article.)

In the first phase of the project the SHEs were known as Private Community Skilled Birth Attendants (PCSBAs) and are mentioned in the cited project documentation interchangeably as SHEs and PCSBAs.

Abbreviations

- Frontline health workers

Skilled birth attendant

Skilled Health Entrepreneurs

Union Parishad

Lassi ZS, Musavi NB, Maliqi B, Mansoor N, de Francisco A, Toure K, et al. Systematic review on human resources for health interventions to improve maternal health outcomes: evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Hum Resour Health. 2016;14(1):10.

Article Google Scholar

Jolivet RR, Moran AC, O’Connor M, Chou D, Bhardwaj N, Newby H, et al. Ending preventable maternal mortality: phase II of a multi-step process to develop a monitoring framework, 2016–2030. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2018;18(1):258.

Girum T, Wasie A. Correlates of maternal mortality in developing countries: an ecological study in 82 countries. Mater Health Neonatol Perinatol. 2017;3(1):19.

Ormel H, Kok M, Kane S, Ahmed R, Chikaphupha K, Rashid SF, de Koning K. Salaried and voluntary community health workers: exploring how incentives and expectation gaps influence motivation. Hum Resour Health. 2019;17(1):1–12.

Bohren MA, Hunter EC, Munthe-Kaas HM, Souza JP, Vogel JP, Gülmezoglu AM. Facilitators and barriers to facility-based delivery in low- and middle-income countries: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Reprod Health. 2014;11(1):71.

Hossain J, Laterra A, Paul RR, Islam A, Ahmmed F, Sarker BK. Filling the human resource gap through public-private partnership: Can private, community-based skilled birth attendants improve maternal health service utilization and health outcomes in a remote region of Bangladesh? PLoS ONE. 2020;15(1): e0226923.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Renfrew MJ, McFadden A, Bastos MH, Campbell J, Channon AA, Cheung NF, et al. Midwifery and quality care: findings from a new evidence-informed framework for maternal and newborn care. Lancet. 2014;384(9948):1129–45.

WHO. WHO guideline on health policy and system support to optimize community health worker programmes. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

Google Scholar

Hossain J, et al. Filling the human resource gap through public-private partnership: Can private, community-based skilled birth attendants improve maternal health service utilization and health outcomes in a remote region of Bangladesh? PLoS ONE. 2020;15(1): e0226923.

Gibson A, Noguchi L, Kinney MV, Blencowe H, Freedman L, Mofokeng T, et al. Galvanizing Collective Action to Accelerate Reductions in Maternal and Newborn Mortality and Prevention of Stillbirths. Global Health: Science and Practice. 2021.

Stanton ME, Kwast BE, Shaver T, McCallon B, Koblinsky M. Beyond the safe motherhood initiative: accelerated action urgently needed to end preventable maternal mortality. Glob Health. 2018;6(3):408–12.

Afulani PA, Moyer C. Explaining disparities in use of skilled birth attendants in developing countries: a conceptual framework. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4): e0154110.

Pitchforth E, van Teijlingen E, Graham W, Dixon-Woods M, Chowdhury M. Getting women to hospital is not enough: a qualitative study of access to emergency obstetric care in Bangladesh. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(3):214–9.

WRA. Respectful maternity care: the universal rights of childbearing women. White Ribbon Alliance; 2017.

Dugani S, Afari H, Hirschhorn LR, Ratcliffe H, Veillard J, Martin G, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with burnout among frontline primary health care providers in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Gates Open Res. 2018;2:4.

Olaniran A, Smith H, Unkels R, Bar-Zeev S, van den Broek N. Who is a community health worker?–a systematic review of definitions. Glob Health Action. 2017;10(1):1272223.

Miyake S, Speakman EM, Currie S, Howard N. Community midwifery initiatives in fragile and conflict-affected countries: a scoping review of approaches from recruitment to retention. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(1):21–33.

Adegoke AA, Atiyaye FB, Abubakar AS, Auta A, Aboda A. Job satisfaction and retention of midwives in rural Nigeria. Midwifery. 2015;31(10):946–56.

Ngilangwa DP, Mgomella GS. Factors associated with retention of community health workers in maternal, newborn and child health programme in Simiyu Region, Tanzania. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2018;10(1):e1–8.

Honda A, Vio F. Incentives for non-physician health professionals to work in the rural and remote areas of Mozambique–a discrete choice experiment for eliciting job preferences. Hum Resour Health. 2015;13:23.

WHO. The prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth: WHO statement. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014.

Moridi M, Pazandeh F, Hajian S, Potrata B. Midwives’ perspectives of respectful maternity care during childbirth: A qualitative study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(3): e0229941.

Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, Jordan K, Leslie HH, Roder-DeWan S, et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(11):e1196–252.

Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, Lutsiv O, Makh SK, Souza JP, et al. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: a mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS Med. 2015;12(6): e1001847.

Shakibazadeh E, Namadian M, Bohren M, Vogel J, Rashidian A, Nogueira PV, et al. Respectful care during childbirth in health facilities globally: a qualitative evidence synthesis. Int J Obstetr Gynaecol. 2018;125(8):932–42.

Sarker BK, Rahman M, Rahman T, Hossain J, Reichenbach L, Mitra DK. Reasons for Preference of Home Delivery with Traditional Birth Attendants (TBAs) in Rural Bangladesh: A Qualitative Exploration. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(1): e0146161.

Turkmani S, Currie S, Mungia J, Assefi N, Javed Rahmanzai A, Azfar P, et al. “Midwives are the backbone of our health system”: lessons from Afghanistan to guide expansion of midwifery in challenging settings. Midwifery. 2013;29(10):1166–72.

Schaaf M, Warthin C, Freedman L, Topp SM. The community health worker as service extender, cultural broker and social change agent: a critical interpretive synthesis of roles, intent and accountability. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(6): e002296.

Closser S, Napier H, Maes K, Abesha R, Gebremariam H, Backe G, et al. Does volunteer community health work empower women? Evidence from Ethiopia’s Women’s Development Army. Health Policy Plan. 2019;34(4):298–306.

Hossain J. Care Bangladesh -GSK 20% reinvestment initiative3-year proposal 2015–2018 proposal. 2015.

Right Kind T. Shuseba Network: Where Next? CARE Bangladesh; 2020.

Islam A. Skilled Health Entrepreneur. Dhaka: CARE; 2109.

Sarker BK, Rahman M, Rahman T, Rahman T, Hasan M, Shahreen T, et al. End line assessment of GSK supported Community Health workers (CHW) initiative in Sunamganj district, Bangladesh. 2019.

TRK. Final Report for Susheba Report. Dhaka: The Right Kind; 2018.

Samuels F, Ancker S. Improving maternal and child health in Asia through innovative partnerships and approaches. London: Overseas Development Institute; 2015.

Witter S, et al. The gendered health workforce: mixed methods analysis from four fragile and post-conflict contexts. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(5):52–62.

Kane S, Kok M, Ormel H, Otiso L, Sidat M, Namakhoma I, et al. Limits and opportunities to community health worker empowerment: a multi-country comparative study. Soc Sci Med. 2016;164:27–34.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

The Glaxo Smith Kline funded the activities described in this article.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

CARE (formerly for Curry, Islam, and Laterra; current for Khandaker), Atlanta, USA

Dora Curry, Md. Ahsanul Islam, Anne Laterra & Ikhtiar Khandaker

University of Georgia, Athens, Georgia

International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh (formerly CARE-Bangladesh), Dhaka, Bangladesh

Bidhan Krishna Sarker

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

DC compiled materials for desk review, conducted a literature search, and was the lead writer for the manuscript. AI was the program manager for the project described and contributed significant review and feedback. BS, AL, and IK contributed meaningful review and feedback. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Dora Curry .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

The information presented in this article drew on a selective review of relevant literature in both peer-reviewed publications and "grey" literature and an in-depth desk review of project documentation, including the project proposal, routine project reporting, midline, and end-line reports, journal articles previously published on program data, and program monitoring and evaluation data. No human subject data were collected for this article. All evaluations conducted in association with the project described obtained consent for participation and received review and approval from the iccddr,b institutional review board.

Consent for publication

All authors have reviewed the final manuscript and consented to publication in BMC Human Resources for Health journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Curry, D., Islam, M.A., Sarker, B.K. et al. A novel approach to frontline health worker support: a case study in increasing social power among private, fee-for-service birthing attendants in rural Bangladesh. Hum Resour Health 21 , 7 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-022-00773-6

Download citation

Received : 03 February 2022

Accepted : 18 October 2022

Published : 07 February 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-022-00773-6

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Skilled birthing attendants

- Health workforce

Human Resources for Health

ISSN: 1478-4491

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

- 30 May 2024

- Research & Ideas

Racial Bias Might Be Infecting Patient Portals. Can AI Help?

Doctors and patients turned to virtual communication when the pandemic made in-person appointments risky. But research by Ariel Stern and Mitchell Tang finds that providers' responses can vary depending on a patient's race. Could technology bring more equity to portals?

- 21 May 2024

- Cold Call Podcast

The Importance of Trust for Managing through a Crisis

In March 2020, Twiddy & Company, a family-owned vacation rental company known for hospitality rooted in personal interactions, needed to adjust to contactless, remote customer service. With the upcoming vacation season thrown into chaos, President Clark Twiddy had a responsibility to the company’s network of homeowners who rented their homes through the company, to guests who had booked vacations, and to employees who had been recruited by Twiddy’s reputation for treating staff well. Who, if anyone, could he afford to make whole and keep happy? Harvard Business School professor Sandra Sucher, author of the book The Power of Trust: How Companies Build It, Lose It, Regain It, discusses how Twiddy leaned into trust to weather the COVID-19 pandemic in her case, “Twiddy & Company: Trust in a Chaotic Environment.”

- 09 Feb 2024

Slim Chance: Drugs Will Reshape the Weight Loss Industry, But Habit Change Might Be Elusive

Medications such as Ozempic, Wegovy, and Mounjaro have upended a $76 billion industry that has long touted lifestyle shifts as a means to weight loss. Regina Herzlinger says these drugs might bring fast change, especially for busy professionals, but many questions remain unanswered.

- 19 Dec 2023

$15 Billion in Five Years: What Data Tells Us About MacKenzie Scott’s Philanthropy

Scott's hands-off approach and unparalleled pace—helping almost 2,000 organizations and counting—has upended the status quo in philanthropy. While her donations might seem scattershot, an analysis of five years of data by Matthew Lee, Brian Trelstad, and Ethan Tran highlights clear trends and an emerging strategy.

- 09 Nov 2023

What Will It Take to Confront the Invisible Mental Health Crisis in Business?

The pressure to do more, to be more, is fueling its own silent epidemic. Lauren Cohen discusses the common misperceptions that get in the way of supporting employees' well-being, drawing on case studies about people who have been deeply affected by mental illness.

- 03 Oct 2023

- Research Event

Build the Life You Want: Arthur Brooks and Oprah Winfrey Share Happiness Tips

"Happiness is not a destination. It's a direction." In this video, Arthur C. Brooks and Oprah Winfrey reflect on mistakes, emotions, and contentment, sharing lessons from their new book.

- 12 Sep 2023

Can Remote Surgeries Digitally Transform Operating Rooms?

Launched in 2016, Proximie was a platform that enabled clinicians, proctors, and medical device company personnel to be virtually present in operating rooms, where they would use mixed reality and digital audio and visual tools to communicate with, mentor, assist, and observe those performing medical procedures. The goal was to improve patient outcomes. The company had grown quickly, and its technology had been used in tens of thousands of procedures in more than 50 countries and 500 hospitals. It had raised close to $50 million in equity financing and was now entering strategic partnerships to broaden its reach. Nadine Hachach-Haram, founder and CEO of Proximie, aspired for Proximie to become a platform that powered every operating room in the world, but she had to carefully consider the company’s partnership and data strategies in order to scale. What approach would position the company best for the next stage of growth? Harvard Business School associate professor Ariel Stern discusses creating value in health care through a digital transformation of operating rooms in her case, “Proximie: Using XR Technology to Create Borderless Operating Rooms.”

- 28 Aug 2023

How Workplace Wellness Programs Can Give Employees the Energy Boost They Need

At a time when many workers are struggling with mental health issues, workplace wellness programs need to go beyond providing gym discounts and start offering employees tailored solutions that improve their physical and emotional well-being, says Hise Gibson.

- 01 Aug 2023

Can Business Transform Primary Health Care Across Africa?

mPharma, headquartered in Ghana, is trying to create the largest pan-African health care company. Their mission is to provide primary care and a reliable and fairly priced supply of drugs in the nine African countries where they operate. Co-founder and CEO Gregory Rockson needs to decide which component of strategy to prioritize in the next three years. His options include launching a telemedicine program, expanding his pharmacies across the continent, and creating a new payment program to cover the cost of common medications. Rockson cares deeply about health equity, but his venture capital-financed company also must be profitable. Which option should he focus on expanding? Harvard Business School Professor Regina Herzlinger and case protagonist Gregory Rockson discuss the important role business plays in improving health care in the case, “mPharma: Scaling Access to Affordable Primary Care in Africa.”

- 25 Jul 2023

Could a Business Model Help Big Pharma Save Lives and Profit?

Gilead Sciences used a novel approach to help Egypt address a public health crisis while sustaining profits from a key product. V. Kasturi Rangan and participants at a recent seminar hosted by the Institute for the Study of Business in Global Society discussed what it would take to apply the model more widely.

- 23 Jun 2023

This Company Lets Employees Take Charge—Even with Life and Death Decisions

Dutch home health care organization Buurtzorg avoids middle management positions and instead empowers its nurses to care for patients as they see fit. Tatiana Sandino and Ethan Bernstein explore how removing organizational layers and allowing employees to make decisions can boost performance.

- 09 May 2023

Can Robin Williams’ Son Help Other Families Heal Addiction and Depression?

Zak Pym Williams, son of comedian and actor Robin Williams, had seen how mental health challenges, such as addiction and depression, had affected past generations of his family. Williams was diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as a young adult and he wanted to break the cycle for his children. Although his children were still quite young, he began considering proactive strategies that could help his family’s mental health, and he wanted to share that knowledge with other families. But how can Williams help people actually take advantage of those mental health strategies and services? Professor Lauren Cohen discusses his case, “Weapons of Self Destruction: Zak Pym Williams and the Cultivation of Mental Wellness.”

- 26 Apr 2023

How Martine Rothblatt Started a Company to Save Her Daughter

When serial entrepreneur Martine Rothblatt (founder of Sirius XM) received her seven-year-old daughter’s diagnosis of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension (PAH), she created United Therapeutics and developed a drug to save her life. When her daughter later needed a lung transplant, Rothblatt decided to take what she saw as the logical next step: manufacturing organs for transplantation. Rothblatt’s entrepreneurial career exemplifies a larger debate around the role of the firm in creating solutions for society’s problems. If companies are uniquely good at innovating, what voice should society have in governing the new technologies that firms create? Harvard Business School professor Debora Spar debates these questions in the case “Martine Rothblatt and United Therapeutics: A Series of Implausible Dreams.” As part of a new first-year MBA course at Harvard Business School, this case examines the central question: what is the social purpose of the firm?

- 25 Apr 2023

Using Design Thinking to Invent a Low-Cost Prosthesis for Land Mine Victims

Bhagwan Mahaveer Viklang Sahayata Samiti (BMVSS) is an Indian nonprofit famous for creating low-cost prosthetics, like the Jaipur Foot and the Stanford-Jaipur Knee. Known for its patient-centric culture and its focus on innovation, BMVSS has assisted more than one million people, including many land mine survivors. How can founder D.R. Mehta devise a strategy that will ensure the financial sustainability of BMVSS while sustaining its human impact well into the future? Harvard Business School Dean Srikant Datar discusses the importance of design thinking in ensuring a culture of innovation in his case, “BMVSS: Changing Lives, One Jaipur Limb at a Time.”

- 31 Mar 2023

Can a ‘Basic Bundle’ of Health Insurance Cure Coverage Gaps and Spur Innovation?

One in 10 people in America lack health insurance, resulting in $40 billion of care that goes unpaid each year. Amitabh Chandra and colleagues say ensuring basic coverage for all residents, as other wealthy nations do, could address the most acute needs and unlock efficiency.

- 13 Mar 2023

The Power of Personal Connections: How Shared Experiences Boost Performance

Doctors who train together go on to provide better patient care later in their careers. What could teams in other industries learn? Research by Maximilian Pany and J. Michael McWilliams.

- 14 Feb 2023

When a Vacation Isn’t Enough, a Sabbatical Can Recharge Your Life—and Your Career

Burning out and ready to quit? Consider an extended break instead. Drawing from research inspired by his own 900-mile journey, DJ DiDonna offers practical advice to help people chart a new path through a sabbatical.

- 10 Feb 2023

COVID-19 Lessons: Social Media Can Nudge More People to Get Vaccinated

Social networks have been criticized for spreading COVID-19 misinformation, but the platforms have also helped public health agencies spread the word on vaccines, says research by Michael Luca and colleagues. What does this mean for the next pandemic?

- 12 Dec 2022

Buy-In from Black Patients Suffers When Drug Trials Don’t Include Them

Diversifying clinical trials could build trust in new treatments among Black people and their physicians. Research by Joshua Schwartzstein, Marcella Alsan, and colleagues probes the ripple effects of underrepresentation in testing, and offers a call to action for drugmakers.

- 06 Sep 2022

Curbing an Unlikely Culprit of Rising Drug Prices: Pharmaceutical Donations

Policymakers of every leaning have vowed to rein in prescription drug costs, with little success. But research by Leemore Dafny shows how closing a loophole on drugmaker donations could eliminate one driver of rising expenses.

- Liberty University

- Jerry Falwell Library

- Special Collections

- < Previous

Home > ETD > Doctoral > 4621

Doctoral Dissertations and Projects

Leadership support as an influence on frontline healthcare employee retention in the washington metropolitan area (dmv).

Tamika Fair , Liberty University Follow

Graduate School of Business

Doctor of Business Administration (DBA)

John M. Borek, Jr.

healthcare leadership, leadership support, frontline healthcare worker

Disciplines

Recommended citation.

Fair, Tamika, "Leadership Support as an Influence on Frontline Healthcare Employee Retention in the Washington Metropolitan Area (DMV)" (2023). Doctoral Dissertations and Projects . 4621. https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/doctoral/4621

The healthcare industry continues to lose its frontline healthcare employees monthly at unprecedented rates. In the healthcare sector, high staff turnover leads to poor patient care and loss of hospital revenues. The general problem addressed by this case study was how healthcare leadership’s lack of support for frontline hospital workers contributes to higher turnover rates, hurting the organizations’ productivity and patient care outcomes. The purpose of this qualitative case study was to add to the body of knowledge about healthcare leadership’s strategies to reduce frontline hospital workers’ high turnover rate affecting the healthcare industry in the DMV area. The study achieved this purpose by exploring how healthcare leaders engage and interact with frontline workers. The research also explored how well healthcare leaders are prepared and trained to address the challenge of high staff turnover. The researcher conducted a qualitative case study using semistructured interviews with 11 primary healthcare administrators in the DMV region to carry out the study. Based on the identified themes, the implications and strategies include investing in resources and leadership development to reduce employee turnover and fatigue. In addition, the results of this study indicate that additional resources and enhanced leadership strategies are required to reduce the turnover of frontline employees in the healthcare industry. To improve working conditions, healthcare organizations in the DMV region should also increase employee empowerment and cultivate organizational citizenship.

Since July 31, 2023

Included in

Business Commons

- Collections

- Faculty Expert Gallery

- Theses and Dissertations

- Conferences and Events

- Open Educational Resources (OER)

- Explore Disciplines

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS .

Faculty Authors

- Submit Research

- Expert Gallery Login

Student Authors

- Undergraduate Submissions

- Graduate Submissions

- Honors Submissions

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

- Open access

- Published: 06 June 2024

Multi-stage optimization strategy based on contextual analysis to create M-health components for case management model in breast cancer transitional care: the CMBM study as an example

- Hong Chengang 1 ,

- Wang Liping 1 ,

- Wang Shujin 1 ,

- Chen Chen 1 ,

- Yang Jiayue 1 ,

- Lu Jingjing 1 ,

- Hua Shujie 1 ,

- Wu Jieming 1 ,

- Yao Liyan 1 ,

- Zeng Ni 1 ,

- Chu Jinhui 1 &

- Sun Jiaqi 1

BMC Nursing volume 23 , Article number: 385 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

Metrics details

None of the early M-Health applications are designed for case management care services. This study aims to describe the process of developing a M-health component for the case management model in breast cancer transitional care and to highlight methods for solving the common obstacles faced during the application of M-health nursing service.

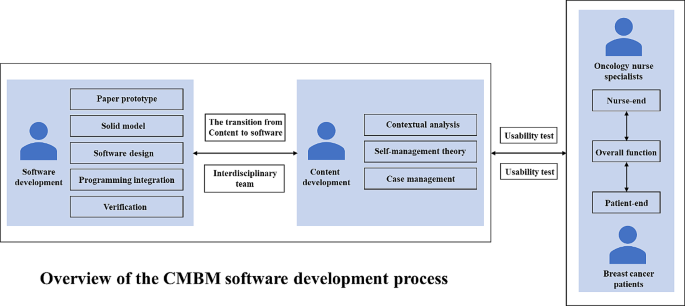

We followed a four-step process: (a) Forming a cross-functional interdisciplinary development team containing two sub-teams, one for content development and the other for software development. (b) Applying self-management theory as the theoretical framework to develop the M-health application, using contextual analysis to gain a comprehensive understanding of the case management needs of oncology nursing specialists and the supportive care needs of out-of-hospital breast cancer patients. We validated the preliminary concepts of the framework and functionality of the M-health application through multiple interdisciplinary team discussions. (c) Adopting a multi-stage optimization strategy consisting of three progressive stages: screening, refining, and confirmation to develop and continually improve the WeChat mini-programs. (d) Following the user-centered principle throughout the development process and involving oncology nursing specialists and breast cancer patients at every stage.

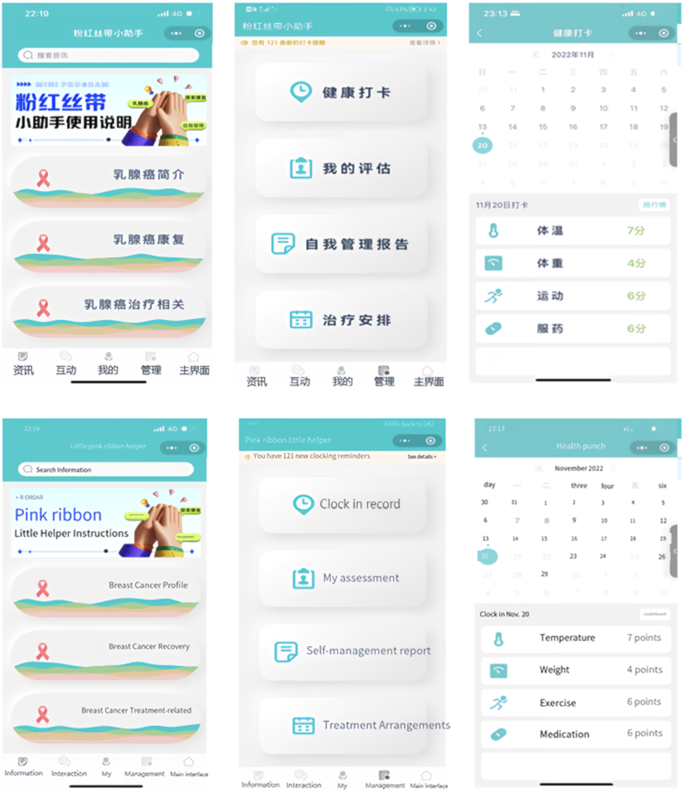

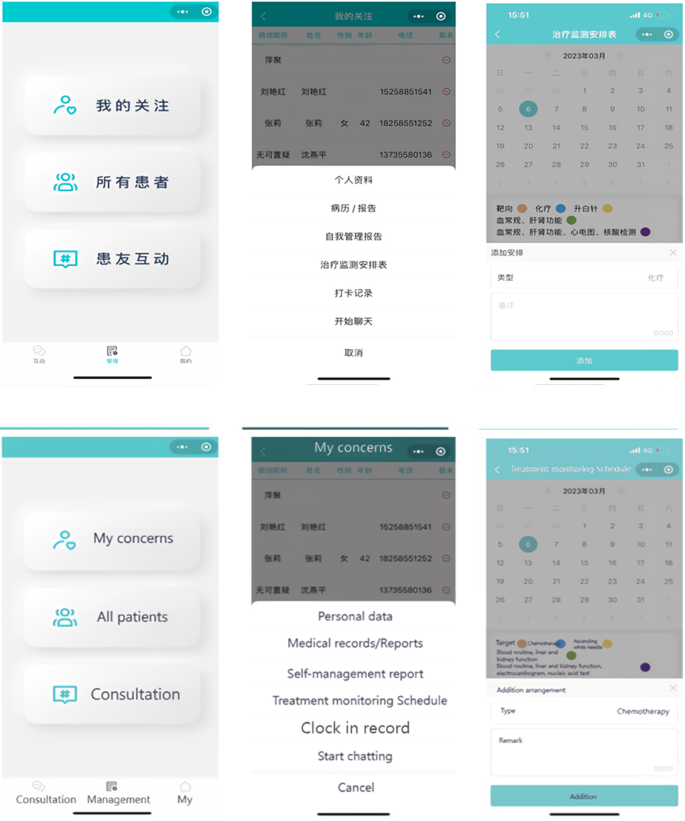

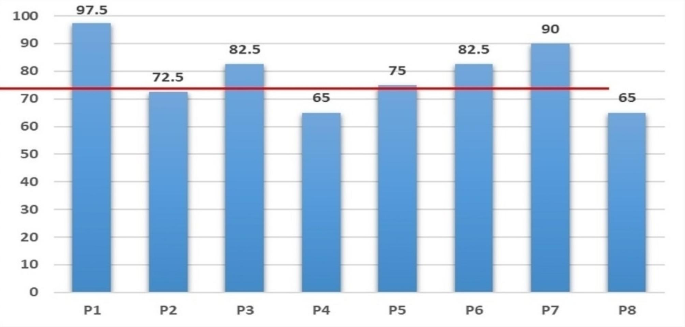

Through a continuous, iterative development process and rigorous testing, we have developed patient-end and nurse-end program for breast cancer case management. The patient-end program contains four functional modules: “Information”, “Interaction”, “Management”, and “My”, while the nurse-end program includes three functional modules: “Consultation”, “Management”, and “My”. The patient-end program scored 78.75 on the System Usability Scale and showed a 100% task passing rate, indicating that the programs were easy to use.

Conclusions

Based on the contextual analysis, multi-stage optimization strategy, and interdisciplinary team work, a WeChat mini-program has been developed tailored to the requirements of the nurses and patients. This approach leverages the expertise of professionals from multiple disciplines to create effective and evidence-based solutions that can improve patient outcomes and quality of care.

Peer Review reports

Female breast cancer is the second leading cause of global cancer incidence in 2022, with an estimated 2.3 million new cases, representing 11.6% of all cancer cases [ 1 ]. Due to surgical trauma, side effects of drugs, fear of the recurrence or metastasis of breast cancer, changes in female characteristics, and lack of knowledge, patients with breast cancer frequently experience a series of physical and psychological health problems [ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ]. These health problems seriously affected patients’ life and work [ 7 , 8 ]. At present, community nursing in China is still in the developing stage, and the oncology specialty nursing service capacity of community nurses is not enough to deal with the health problems of breast cancer patients. It made continuous care for out-of-hospital breast cancer patients a weak link in the Chinese oncology nursing service system.

Nowadays, case management is employed to manage health problems for out-of-hospital breast cancer patients worldwide [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 15 ]. Case management involves regular telephone follow-ups and home visits by case management nurses to provide educational support to patients, thereby ensuring uninterrupted continuity of care [ 16 , 17 ]. The home visits and organization of patient information required for case management tasks consume a significant amount of time, manpower, and material resources [ 17 ]. In China, case management services are primarily undertaken by oncology nursing specialists from tertiary hospitals in their spare time [ 18 ]. However, the shortage of nurses has consistently been one of the major challenges facing the nursing industry in China, especially in tertiary hospitals [ 19 ]. Consequently, the implementation and promotion of case management in China also face great difficulties in reality [ 20 ].

The Global Observatory for eHealth (GOe) of the World Health Organization (WHO) defines mobile health (M-Health) as “medical and public health practice supported by mobile devices, such as mobile phones, patient monitoring devices, personal digital assistants (PDAs), and other wireless devices” [ 21 , 22 ]. With the development of digital technology and the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019, M-Health applications were further integrated into healthcare services, which increased the demand for M-Health applications in turn [ 23 , 24 ]. Compared with the traditional health service model, M-Health service model has the advantages of high-level informatization, fast response speed, freedom from time and location constraints, and resource-saving, etc. In the context of limited nursing human resources, M-Health service provides a new solution for the case management of out-of-hospital breast cancer patients [ 23 , 25 , 26 ].

Researchers have developed a range of M-Health applications targeting breast cancer patients. To our knowledge, none of these developed M-Health applications are designed for case management nursing services.

Early M-Health applications were mostly designed for single interventional goals, such as health education, medication compliance, self-monitoring, etc. Larsen et al. applied a M-Health application to monitor and adjust the dosage of oral chemotherapy drugs in breast cancer patients, and the results suggested that the treatment adherence was effectively improved [ 27 ]. Heo and his team successfully promoted self-breast-examination behavior in women under 30 years old using a M-Health application [ 28 ]. Mccarrol carried out a M-Health diet and exercise intervention in overweight breast cancer patients and found that the weight, BMI, and waist circumference of the intervention group decreased after one month [ 29 ]. Smith’s team found that their application promoted the adoption of healthy diet and exercise behaviors among breast cancer patients [ 30 ]. The application designed by Eden et al. enhanced the ability of breast cancer patients receiving chemotherapy to recognize adverse drug reactions [ 31 ]. Keohane and colleagues designed a health educational application based on the best practices and it proved effective in improving breast cancer-related knowledge [ 32 ]. The guideline-based M-Health application developed by Eden et al. optimized breast cancer patients’ individualized health decision-making regarding mammography [ 33 ].

With the progress of computer technology and the emphasis on physical and mental rehabilitation of breast cancer patients, some universities [ 34 , 35 ] in China have separately developed M-Health applications for comprehensive health management, which provide access to online communication, health education, and expert consultation.

Analyzing these developed applications deeply, three factors could be found that hindered the promotion of applications in real life. Firstly, the developing procedure usually lacks contextual analysis based on the actual usage context during the design phase. Secondly, there is a lack of consistent and long-term monitoring and operation staff in the subsequent program implementation. These factors may be the main reasons why many M-Health applications face difficulties in promotion and continuous operation after the research phase. Furthermore, as applications need to be installed on patients’ smartphones, certain hardware requirements, such as memory, may also pose restrict the adoption of M-Health applications to some extent.

In order to meet the needs of supportive care for out-of-hospital breast cancer patients and the needs of case management for oncology nurse specialists, we formed a multidisciplinary research team and collaboratively developed a WeChat mini-program for breast cancer case management in the CMBM (M-health for case management model in breast cancer transitional care) project. WeChat is chosen as the program development platform based on the following considerations. Firstly, WeChat is the most popular and widely used social software in China. As of December 31, 2020, the monthly active users of WeChat have exceeded 1.2 billion, and the daily active users of WeChat mini-programs exceeded 450 million [ 36 ]. Secondly, users can access and use the services of the mini-program directly within the WeChat platform, without the need to download or install additional mobile applications. This reduces the hardware requirements for software applications. The above two factors allow for a positive user experience and a realistic foundation for software promotion.

The purpose of this study is to describe the process of developing a tailored M-health component for the case management model in breast cancer transitional care and to highlight methods for solving the common obstacles faced during the application of M-health nursing service.

Methods and results

The development process was conducted in four steps: (a) An interdisciplinary development team was formed, consisting of two sub-teams dedicated to content and software development. (b) Using the self-management theory as the theoretical framework, contextual analysis was used to understand the case management needs of oncology nursing specialists and the supportive care needs of out-of-hospital breast cancer patients. Through iterative discussion within the interdisciplinary team, the preliminary conception of the application framework and function was formed. (c) A multi-stage optimization strategy was adopted to develop and regularly update the WeChat mini-programs, including three stages (screening, refining, and confirming). (d) During the entire development process, a user-centered principle was followed with the involvement of oncology nursing specialists and breast cancer patients, including development, testing, and iterative development phases.

The interdisciplinary team

An important prerequisite for developing M-health applications is the formation of an interdisciplinary development team. We built a multidisciplinary team consisting of researchers, oncology nursing specialists, and software developers. Each team member brought their expertise from their respective fields, and all individuals were considered members of the same team rather than separate participants with a common goal.

Two sub-teams were established, one responsible for content development, and the other for software development. The content development team consisted of researchers and six senior breast oncology nursing specialists with bachelor’s degrees and over 10 years of clinical experience. Their work included contextual analysis, functional framework design, and content review of the “Information” module. The software development team included researchers and experienced software developers. Their tasks involved developing the mini-program based on the functional framework and requirements designed by the content development team.

The development team used contextual analysis to identify the actual usage needs of two target groups for the mini-program: oncologist nurse specialists and out-of-hospital breast cancer patients.

Involvement of oncology nursing specialists and breast cancer patients following user-centered design principle

Since the oncology nursing specialists and breast cancer patients are targeted users of the mini-program, the two groups fully participated in the development according to the user-centered principle. Nursing specialists who in charge of case management were interviewed about the preliminary functional framework of the mini-program. The interview results are presented in the section “Driving the Development Process via the Contextual Analysis Findings.” Semi-structured in-depth interviews were conducted in the testing and iteration stage to gain user feedback from nursing specialists to improve the applicability and usability of the mini-program. The interview guide can be found in the supplementary material.

Breast cancer patients fully engaged in the three developing phases (Screening, Refining, and Confirming). In the Screening Phase, since the self-management theory was selected as the theoretical framework, the supportive care needs of out-of-hospital breast cancer patients were explored, and the functional framework of the mini-program was constructed accordingly. In the Refining Phase, patients were invited to evaluate the usability and practicality of the mini-program through system tests and semi-structured in-depth interviews. The results of the system test are presented in the Results of System Test section. The feedback from interviews and corresponding iterative updates are listed in Table 1 . In the Confirming Phase, our research team is conducting clinical trials in out-of-hospital breast cancer patients to find out the actual effect of the mini-program on recovery.

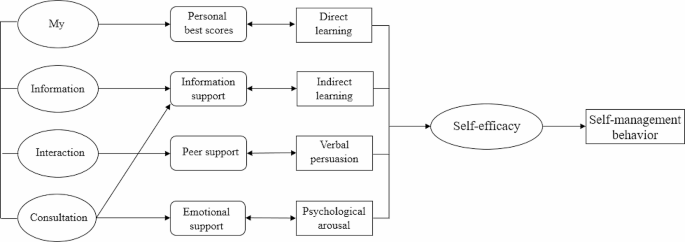

The theory framework of the mini-program

This study applied the self-management theory [ 37 ] as the theoretical framework. The self-management theory explains how individual factors and environmental factors influence an individual’s self-efficacy, which ultimately affects the generation and development of individual behaviors. Self-efficacy is influenced by direct experience, indirect learning, verbal persuasion, and psychological arousal. By providing individuals with sufficient knowledge, healthy beliefs, skills, and support, their self-efficacy is increased, and they are likely to engage in beneficial health behaviors and self-management. Individuals who are confident in their abilities to apply self-management behaviors and overcome obstacles by improving their self-management skills and persevere in their efforts to manage their health [ 37 ]. Self-efficacy is directly and linearly positively related to the active adoption of health management behaviors [ 38 ]. The functions of the various parts of the mini-program designed using self-management theory can broaden the pathways and levels of efficacy information generation in four ways: direct experience, indirect learning, verbal persuasion, and mental arousal. Patients with high self-efficacy will take positive steps to achieve desired goals and possess disease-adapted behaviors. The form of the mini-application function block diagram is shown in Fig. 1 .

Driving the development process via the contextual analysis findings

Contextual analysis [ 39 ] is a method of discerning the profound significance and influence of language, behavior, events, and so forth, by examining them within a particular environment or background. Rather than being an afterthought, contextual analysis sheds light on the meaning and inner dynamics of our primary subject of interest. Through contextual analysis, we can gain a deeper understanding of the user’s usage scenarios, including their motivations, goals, environment, and behavior. This helps us better understand user needs, as well as the problems and challenges they may encounter when using the software.

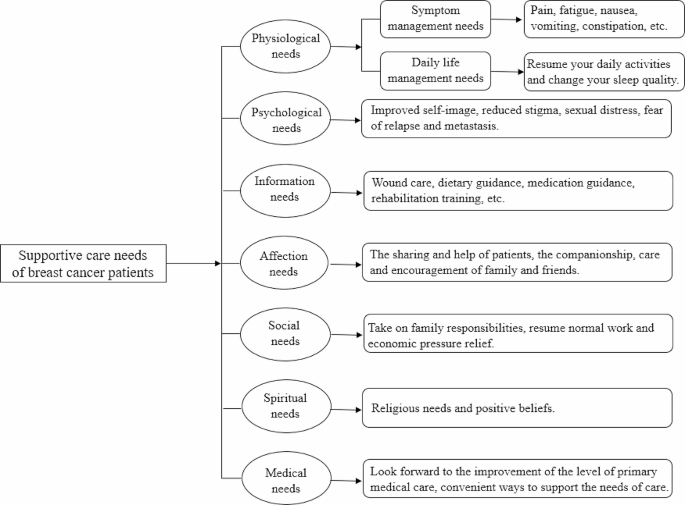

In this paper, we adopted contextual analysis to gain a detailed understanding of the needs of oncology nurse specialists and out-of-hospital breast cancer patients. The research team adopted a mixed research strategy to achieve contextual analysis of the target users. A cross-sectional study was conducted among 286 patients and qualitative semi-structured in-depth interviews were applied in 12 patients to find out the supportive care needs of out-of-hospital breast cancer patients. According to the contextual analysis results from patients, the functional framework of the mini-program was constructed. See Fig. 2 for details.

Supportive care needs of out-of-hospital breast cancer patients

Contextual analysis of breast cancer case management nurses was conducted through focus group interview. The interview results were listed as three themes: health information, personal self-management, and case management needs. Health information included breast cancer-related knowledge, the side effects of chemotherapy drugs, and symptom management measures. The key task of personal self-management contained temperature monitoring, weight management, functional exercise, and symptom management. Case management needs involved storage and management of patients’ medical records and development of a nurse-end program.

Based on the contextual analysis results of out-of-hospital breast cancer patients and the oncology case management nurses, the framework and functional block of the mini-program were formed. An overview of the CMBM Software development process is listed in Fig. 3 .

Overview of the CMBM software development process

Patient-end program functional modules

Using the results of the contextual analysis, we design the functional modules of the patient-end program based on the patient’s supportive care needs. For example, the “Information” section is designed to meet the “Information need” of breast cancer patients; the “social needs” and “spiritual needs” of patients suggest that breast cancer patients lack peer support, and for this reason, the"Interaction” section for patients has been added to the app to provide a communication platform for patients.