Academic Reading Strategies

Completing reading assignments is one of the biggest challenges in academia. However, are you managing your reading efficiently? Consider this cooking analogy, noting the differences in process:

Taylor’s process was more efficient because his purpose was clear. Establishing why you are reading something will help you decide how to read it, which saves time and improves comprehension. This guide lists some purposes for reading as well as different strategies to try at different stages of the reading process.

Purposes for reading

People read different kinds of text (e.g., scholarly articles, textbooks, reviews) for different reasons. Some purposes for reading might be

- to scan for specific information

- to skim to get an overview of the text

- to relate new content to existing knowledge

- to write something (often depends on a prompt)

- to critique an argument

- to learn something

- for general comprehension

Strategies differ from reader to reader. The same reader may use different strategies for different contexts because their purpose for reading changes. Ask yourself “why am I reading?” and “what am I reading?” when deciding which strategies to try.

Before reading

- Establish your purpose for reading

- Speculate about the author’s purpose for writing

- Review what you already know and want to learn about the topic (see the guides below)

- Preview the text to get an overview of its structure, looking at headings, figures, tables, glossary, etc.

- Predict the contents of the text and pose questions about it. If the authors have provided discussion questions, read them and write them on a note-taking sheet.

- Note any discussion questions that have been provided (sometimes at the end of the text)

- Sample pre-reading guides – K-W-L guide

- Critical reading questionnaire

During reading

- Annotate and mark (sparingly) sections of the text to easily recall important or interesting ideas

- Check your predictions and find answers to posed questions

- Use headings and transition words to identify relationships in the text

- Create a vocabulary list of other unfamiliar words to define later

- Try to infer unfamiliar words’ meanings by identifying their relationship to the main idea

- Connect the text to what you already know about the topic

- Take breaks (split the text into segments if necessary)

- Sample annotated texts – Journal article · Book chapter excerpt

After reading

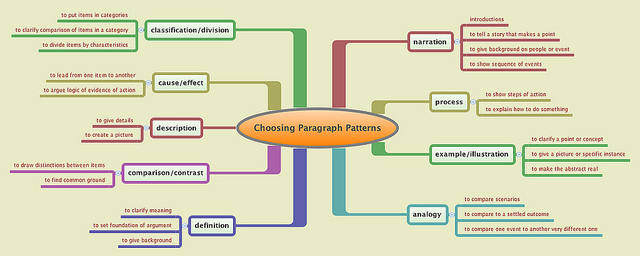

- Summarize the text in your own words (note what you learned, impressions, and reactions) in an outline, concept map, or matrix (for several texts)

- Talk to someone about the author’s ideas to check your comprehension

- Identify and reread difficult parts of the text

- Define words on your vocabulary list (try a learner’s dictionary ) and practice using them

- Sample graphic organizers – Concept map · Literature review matrix

Works consulted

Grabe, W., & Stoller, F. L. (2002). Teaching and researching reading. Harlow: Longman.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout (just click print) and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

If you enjoy using our handouts, we appreciate contributions of acknowledgement.

Essays About Reading: 5 Examples And Topic Ideas

As a writer, you love to read and talk to others about reading books. Check out some examples of essays about reading and topic ideas for your essay.

Many people fall in love with good books at an early age, as experiencing the joy of reading can help transport a child’s imagination to new places. Reading isn’t just for fun, of course—the importance of reading has been shown time and again in educational research studies.

If you love to sit down with a good book, you likely want to share your love of reading with others. Reading can offer a new perspective and transport readers to different worlds, whether you’re into autobiographies, books about positive thinking, or stories that share life lessons.

When explaining your love of reading to others, it’s important to let your passion shine through in your writing. Try not to take a negative view of people who don’t enjoy reading, as reading and writing skills are tougher for some people than others.

Talk about the positive effects of reading and how it’s positively benefitted your life. Offer helpful tips on how people can learn to enjoy reading, even if it’s something that they’ve struggled with for a long time. Remember, your goal when writing essays about reading is to make others interested in exploring the world of books as a source of knowledge and entertainment.

Now, let’s explore some popular essays on reading to help get you inspired and some topics that you can use as a starting point for your essay about how books have positively impacted your life.

For help with your essays, check out our round-up of the best essay checkers

Examples Of Essays About Reading

- 1. The Book That Changed My Life By The New York Times

- 2. I Read 150+ Books in 2 Years. Here’s How It Changed My Life By Anangsha Alammyan

- 3. How My Diagnosis Improved My College Experience By Blair Kenney

4. How ‘The Phantom Tollbooth’ Saved Me By Isaac Fitzgerald

5. catcher in the rye: that time a banned book changed my life by pat kelly, topic ideas for essays about reading, 1. how can a high school student improve their reading skills, 2. what’s the best piece of literature ever written, 3. how reading books from authors of varied backgrounds can provide a different perspective, 4. challenging your point of view: how reading essays you disagree with can provide a new perspective, 1. the book that changed my life by the new york times.

“My error the first time around was to read “Middlemarch” as one would a typical novel. But “Middlemarch” isn’t really about plot and dialogue. It’s all about character, as mediated through the wise and compassionate (but sharply astute) voice of the omniscient narrator. The book shows us that we cannot live without other people and that we cannot live with other people unless we recognize their flaws and foibles in ourselves.” The New York Times

In this collection of reader essays, people share the books that have shaped how they see the world and live their lives. Talking about a life-changing piece of literature can offer a new perspective to people who tend to shy away from reading and can encourage others to pick up your favorite book.

2. I Read 150+ Books in 2 Years. Here’s How It Changed My Life By Anangsha Alammyan

“Consistent reading helps you develop your analytical thinking skills over time. It stimulates your brain and allows you to think in new ways. When you are actively engaged in what you’re reading, you would be able to ask better questions, look at things from a different perspective, identify patterns and make connections.” Anangsha Alammyan

Alammyan shares how she got away from habits that weren’t serving her life (such as scrolling on social media) and instead turned her attention to focus on reading. She shares how she changed her schedule and time management processes to allow herself to devote more time to reading, and she also shares the many ways that she benefited from spending more time on her Kindle and less time on her phone.

3. How My Diagnosis Improved My College Experience By Blair Kenney

“When my learning specialist convinced me that I was an intelligent person with a reading disorder, I gradually stopped hiding from what I was most afraid of—the belief that I was a person of mediocre intelligence with overambitious goals for herself. As I slowly let go of this fear, I became much more aware of my learning issues. For the first time, I felt that I could dig below the surface of my unhappiness in school without being ashamed of what I might find.” Blair Kenney

Reading does not come easily to everyone, and dyslexia can make it especially difficult for a person to process words. In this essay, Kenney shares her experience of being diagnosed with dyslexia during her sophomore year of college at Yale. She gave herself more patience, grew in her confidence, and developed techniques that worked to improve her reading and processing skills.

“I took that book home to finish reading it. I’d sit somewhat uncomfortably in a tree or against a stone wall or, more often than not, in my sparsely decorated bedroom with the door closed as my mother had hushed arguments with my father on the phone. There were many things in the book that went over my head during my first time reading it. But a land left with neither Rhyme nor Reason, as I listened to my parents fight, that I understood.” Isaac Fitzgerald

Books can transport a reader to another world. In this essay, Fitzgerald explains how Norton Juster’s novel allowed him to escape a difficult time in his childhood through the magic of his imagination. Writing about a book that had a significant impact on your childhood can help you form an instant connection with your reader, as many people hold a childhood literature favorite near and dear to their hearts.

“From the first paragraph my mind was blown wide open. It not only changed my whole perspective on what literature could be, it changed the way I looked at myself in relation to the world. This was heavy stuff. Of the countless books I had read up to this point, even the ones written in first person, none of them felt like they were speaking directly to me. Not really anyway.” Pat Kelly

Many readers have had the experience of feeling like a book was written specifically for them, and in this essay, Kelly shares that experience with J.D. Salinger’s classic American novel. Writing about a book that felt like it was written specifically for you can give you the chance to share what was happening in your life when you read the book and the lasting impact that the book had on you as a person.

There are several topic options to choose from when you’re writing about reading. You may want to write about how literature you love has changed your life or how others can develop their reading skills to derive similar pleasure from reading.

Middle and high school students who struggle with reading can feel discouraged when, despite their best efforts, their skills do not improve. Research the latest educational techniques for boosting reading skills in high school students (the research often changes) and offer concrete tips (such as using active reading skills) to help students grow.

It’s an excellent persuasive essay topic; it’s fun to write about the piece of literature you believe to be the greatest of all time. Of course, much of this topic is a matter of opinion, and it’s impossible to prove that one piece of literature is “better” than another. Write your essay about how the piece of literature you consider the best positive affected your life and discuss how it’s impacted the world of literature in general.

The world is full of many perspectives and points of view, and it can be hard to imagine the world through someone else’s eyes. Reading books by authors of different gender, race, or socioeconomic status can help open your eyes to the challenges and issues others face. Explain how reading books by authors with different backgrounds has changed your worldview in your essay.

It’s fun to read the information that reinforces viewpoints that you already have, but doing so doesn’t contribute to expanding your mind and helping you see the world from a different perspective. Explain how pushing oneself to see a different point of view can help you better understand your perspective and help open your eyes to ideas you may not have considered.

Tip: If writing an essay sounds like a lot of work, simplify it. Write a simple 5 paragraph essay instead.

If you’re stuck picking your next essay topic, check out our round-up of essay topics about education .

Amanda has an M.S.Ed degree from the University of Pennsylvania in School and Mental Health Counseling and is a National Academy of Sports Medicine Certified Personal Trainer. She has experience writing magazine articles, newspaper articles, SEO-friendly web copy, and blog posts.

View all posts

Types Of Reading Skills For Effective Communication

“Reading is to the mind what exercise is to the body,” said English author Joseph Addison. The comparison couldn’t be…

“Reading is to the mind what exercise is to the body,” said English author Joseph Addison.

The comparison couldn’t be more fitting. Just as you need exercise to build your physical strength, you need to read to build your mental muscles.

People read for a variety of reasons—to pass time, to seek answers, or to clear their heads.

Whatever their reasons for reading, it is a great way of exercising the brain and improving your communication skills. Something you really need to grow as a professional. So, what are the different types of reading?

Just as you have simple as well as specialized exercise routines and equipment, you also have different types of reading skills. You can choose the right one depending on your objective.

Different types of reading

It’s important to know the different types of reading skills to make the most of what you are reading. You may reading a novel written by Haruki Murakami or a business report from work. If you’re reading for university, it takes a lot more patience, attention to detail and note-taking. You need to first understand the types of reading there are and then make a case for what you enjoy the most. ( victory.org )

Here are some of the most common types of reading you’ll encounter during your life:

Extensive reading:

Extensive reading is one of the methods of reading that people use for relaxation and pleasure. Adopt this method when the purpose is to enjoy the reading experience. It places no burden upon the reader and due to its indulgent nature, it is seldom used if the text isn’t enjoyable.

This is one of the methods of reading that occurs naturally. It’s how you’ve read as a child and while growing up.

This method of reading helps you understand words in context and enriches your vocabulary.

Intensive reading:

Among the different types of reading skills, intensive reading is used when you want to read carefully by paying complete attention to understand every word of the text. It is where you would examine and decipher each unfamiliar word or expression.

As the term states, intensive means in-depth. This reading method is especially used when reading academic texts, where the goal is to prepare for an exam or to publish a report. This method helps retain information for much longer periods.

Imagine if you went to the Louvre museum only to see the Mona Lisa. You’d quickly walk through all the corridors and rooms merely glancing at the walls until you found it. Scanning is quite similar to that.

It is one of those kinds of reading where you read to search for a particular piece of information. Your eyes quickly skim over the sentences until you find it.

You can use this method when you don’t need to go deep into the text and read every word carefully. Scanning involves rapid reading and is often used by researchers and for writing reviews.

Through this method, you try to understand the text in short. Though one saves a lot of time through this method, one will gain only a shallow understanding of the text.

Skimming is a great way to get a broad idea of the topic being discussed. This method is generally used to judge whether the information is useful or not.

A good example of this is picking up a magazine and flipping through the pages. You take in only the headings or the pictures to get a broad idea of what the magazine covers.

Critical reading:

Among the different types of reading strategies, critical reading has a special place. Here, the facts and information are tested for accuracy. You take a look at the ideas mentioned and analyze them until you reach a conclusion.

You would have to apply your critical faculties when using this method. Critical reading is often used when reading the news on social media, watching controversial advertisements, or reading periodicals.

Various types of reading lead to different outcomes. Choosing the right one can be instrumental in furthering your goals. Further, diversifying your reading habits to include different types of reading will enable you to become a better writer and speaker. Improving your communication skills will enable you to convey your ideas with precision and clarity. It’s not always easy to get your point across. But reading gives you the power to understand multiple perspectives. Building a reading habit can be effective in the short and long run.

To harness the full potential of your reading habit, sign up for Harappa Education’s Reading Deeply course. Learn how to improve comprehension and read for deeper understanding. Sign up now and make the most of everything you read.

Explore blogs about skills and topics such as reading s kills and the l evels of reading in our Harappa Diaries section to improve your reading quotient.

5.2 Effective Reading Strategies

Questions to Consider:

- What methods can you incorporate into your routine to allow adequate time for reading?

- What are the benefits and approaches to active reading?

- Do your courses or major have specific reading requirements?

Allowing Adequate Time for Reading

You should determine the reading requirements and expectations for every class very early in the semester. You also need to understand why you are reading the particular text you are assigned. Do you need to read closely for minute details that determine cause and effect? Or is your instructor asking you to skim several sources so you become more familiar with the topic? Knowing this reasoning will help you decide your timing, what notes to take, and how best to undertake the reading assignment.

Depending on the makeup of your schedule, you may end up reading both primary sources—such as legal documents, historic letters, or diaries—as well as textbooks, articles, and secondary sources, such as summaries or argumentative essays that use primary sources to stake a claim. You may also need to read current journalistic texts to stay current in local or global affairs. A realistic approach to scheduling your time to allow you to read and review all the reading you have for the semester will help you accomplish what can sometimes seem like an overwhelming task.

When you allow adequate time in your hectic schedule for reading, you are investing in your own success. Reading isn’t a magic pill, but it may seem like it when you consider all the benefits people reap from this ordinary practice. Famous successful people throughout history have been voracious readers. In fact, former U.S. president Harry Truman once said, “Not all readers are leaders, but all leaders are readers.” Writer of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, inventor, and also former U.S. president Thomas Jefferson claimed “I cannot live without books” at a time when keeping and reading books was an expensive pastime. Knowing what it meant to be kept from the joys of reading, 19th-century abolitionist Frederick Douglass said, “Once you learn to read, you will be forever free.” And finally, George R. R. Martin, the prolific author of the wildly successful Game of Thrones empire, declared, “A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies . . . The man who never reads lives only one.”

You can make time for reading in a number of ways that include determining your usual reading pace and speed, scheduling active reading sessions, and practicing recursive reading strategies.

Determining Reading Speed and Pacing

To determine your reading speed, select a section of text—passages in a textbook or pages in a novel. Time yourself reading that material for exactly 5 minutes, and note how much reading you accomplished in those 5 minutes. Multiply the amount of reading you accomplished in 5 minutes by 12 to determine your average reading pace (5 times 12 equals the 60 minutes of an hour). Of course, your reading pace will be different and take longer if you are taking notes while you read, but this calculation of reading pace gives you a good way to estimate your reading speed that you can adapt to other forms of reading.

So, for instance, if Marta was able to read 4 pages of a dense novel for her English class in 5 minutes, she should be able to read about 48 pages in one hour. Knowing this, Marta can accurately determine how much time she needs to devote to finishing the novel within a set amount of time, instead of just guessing. If the novel Marta is reading is 497 pages, then Marta would take the total page count (497) and divide that by her hourly reading rate (48 pages/hour) to determine that she needs about 10 to 11 hours overall. To finish the novel spread out over two weeks, Marta needs to read a little under an hour a day to accomplish this goal.

Calculating your reading rate in this manner does not take into account days where you’re too distracted and you have to reread passages or days when you just aren’t in the mood to read. And your reading rate will likely vary depending on how dense the content you’re reading is (e.g., a complex textbook vs. a comic book). Your pace may slow down somewhat if you are not very interested in what the text is about. What this method will help you do is be realistic about your reading time as opposed to waging a guess based on nothing and then becoming worried when you have far more reading to finish than the time available.

Chapter 3 , offers more detail on how best to determine your speed from one type of reading to the next so you are better able to schedule your reading.

Scheduling Set Times for Active Reading

Active reading takes longer than reading through passages without stopping. You may not need to read your latest sci-fi series actively while you’re lounging on the beach, but many other reading situations demand more attention from you. Active reading is particularly important for college courses. You are a scholar actively engaging with the text by posing questions, seeking answers, and clarifying any confusing elements. Plan to spend at least twice as long to read actively than to read passages without taking notes or otherwise marking select elements of the text.

To determine the time you need for active reading, use the same calculations you use to determine your traditional reading speed and double it. Remember that you need to determine your reading pace for all the classes you have in a particular semester and multiply your speed by the number of classes you have that require different types of reading.

Practicing Recursive Reading Strategies

One fact about reading for college courses that may become frustrating is that, in a way, it never ends. For all the reading you do, you end up doing even more rereading. It may be the same content, but you may be reading the passage more than once to detect the emphasis the writer places on one aspect of the topic or how frequently the writer dismisses a significant counterargument. This rereading is called recursive reading.

For most of what you read at the college level, you are trying to make sense of the text for a specific purpose—not just because the topic interests or entertains you. You need your full attention to decipher everything that’s going on in complex reading material—and you even need to be considering what the writer of the piece may not be including and why. This is why reading for comprehension is recursive.

Specifically, this boils down to seeing reading not as a formula but as a process that is far more circular than linear. You may read a selection from beginning to end, which is an excellent starting point, but for comprehension, you’ll need to go back and reread passages to determine meaning and make connections between the reading and the bigger learning environment that led you to the selection—that may be a single course or a program in your college, or it may be the larger discipline, such as all biologists or the community of scholars studying beach erosion.

People often say writing is rewriting. For college courses, reading is rereading.

Strong readers engage in numerous steps, sometimes combining more than one step simultaneously, but knowing the steps nonetheless. They include, not always in this order:

- bringing any prior knowledge about the topic to the reading session,

- asking yourself pertinent questions, both orally and in writing, about the content you are reading,

- inferring and/or implying information from what you read,

- learning unfamiliar discipline-specific terms,

- evaluating what you are reading, and eventually,

- applying what you’re reading to other learning and life situations you encounter.

Let’s break these steps into manageable chunks, because you are actually doing quite a lot when you read.

Accessing Prior Knowledge

When you read, you naturally think of anything else you may know about the topic, but when you read deliberately and actively, you make yourself more aware of accessing this prior knowledge. Have you ever watched a documentary about this topic? Did you study some aspect of it in another class? Do you have a hobby that is somehow connected to this material? All of this thinking will help you make sense of what you are reading.

Application

Imagining that you were given a chapter to read in your American history class about the Gettysburg Address, write down what you already know about this historic document. How might thinking through this prior knowledge help you better understand the text?

Asking Questions

Humans are naturally curious beings. As you read actively, you should be asking questions about the topic you are reading. Don’t just say the questions in your mind; write them down. You may ask: Why is this topic important? What is the relevance of this topic currently? Was this topic important a long time ago but irrelevant now? Why did my professor assign this reading?

You need a place where you can actually write down these questions; a separate page in your notes is a good place to begin. If you are taking notes on your computer, start a new document and write down the questions. Leave some room to answer the questions when you begin and again after you read.

Inferring and Implying

When you read, you can take the information on the page and infer , or conclude responses to related challenges from evidence or from your own reasoning. A student will likely be able to infer what material the professor will include on an exam by taking good notes throughout the classes leading up to the test.

Writers may imply information without directly stating a fact for a variety of reasons. Sometimes a writer may not want to come out explicitly and state a bias, but may imply or hint at his or her preference for one political party or another. You have to read carefully to find implications because they are indirect, but watching for them will help you comprehend the whole meaning of a passage.

Learning Vocabulary

Vocabulary specific to certain disciplines helps practitioners in that field engage and communicate with each other. Few people beyond undertakers and archeologists likely use the term sarcophagus in everyday communications, but for those disciplines, it is a meaningful distinction. Looking at the example, you can use context clues to figure out the meaning of the term sarcophagus because it is something undertakers and/or archeologists would recognize. At the very least, you can guess that it has something to do with death. As a potential professional in the field you’re studying, you need to know the lingo. You may already have a system in place to learn discipline-specific vocabulary, so use what you know works for you. Two strong strategies are to look up words in a dictionary (online or hard copy) to ensure you have the exact meaning for your discipline and to keep a dedicated list of words you see often in your reading. You can list the words with a short definition so you have a quick reference guide to help you learn the vocabulary.

Intelligent people always question and evaluate. This doesn’t mean they don’t trust others; they just need verification of facts to understand a topic well. It doesn’t make sense to learn incomplete or incorrect information about a subject just because you didn’t take the time to evaluate all the sources at your disposal. When early explorers were afraid to sail the world for fear of falling off the edge, they weren’t stupid; they just didn’t have all the necessary data to evaluate the situation.

When you evaluate a text, you are seeking to understand the presented topic. Depending on how long the text is, you will perform a number of steps and repeat many of these steps to evaluate all the elements the author presents. When you evaluate a text, you need to do the following:

- Scan the title and all headings.

- Read through the entire passage fully.

- Question what main point the author is making.

- Decide who the audience is.

- Identify what evidence/support the author uses.

- Consider if the author presents a balanced perspective on the main point.

- Recognize if the author introduced any biases in the text.

When you go through a text looking for each of these elements, you need to go beyond just answering the surface question; for instance, the audience may be a specific field of scientists, but could anyone else understand the text with some explanation? Why would that be important?

Analysis Question

Think of an article you need to read for a class. Take the steps above on how to evaluate a text, and apply the steps to the article. When you accomplish the task in each step, ask yourself and take notes to answer the question: Why is this important? For example, when you read the title, does that give you any additional information that will help you comprehend the text? If the text were written for a different audience, what might the author need to change to accommodate that group? How does an author’s bias distort an argument? This deep evaluation allows you to fully understand the main ideas and place the text in context with other material on the same subject, with current events, and within the discipline.

When you learn something new, it always connects to other knowledge you already have. One challenge we have is applying new information. It may be interesting to know the distance to the moon, but how do we apply it to something we need to do? If your biology instructor asked you to list several challenges of colonizing Mars and you do not know much about that planet’s exploration, you may be able to use your knowledge of how far Earth is from the moon to apply it to the new task. You may have to read several other texts in addition to reading graphs and charts to find this information.

That was the challenge the early space explorers faced along with myriad unknowns before space travel was a more regular occurrence. They had to take what they already knew and could study and read about and apply it to an unknown situation. These explorers wrote down their challenges, failures, and successes, and now scientists read those texts as a part of the ever-growing body of text about space travel. Application is a sophisticated level of thinking that helps turn theory into practice and challenges into successes.

Preparing to Read for Specific Disciplines in College

Different disciplines in college may have specific expectations, but you can depend on all subjects asking you to read to some degree. In this college reading requirement, you can succeed by learning to read actively, researching the topic and author, and recognizing how your own preconceived notions affect your reading. Reading for college isn’t the same as reading for pleasure or even just reading to learn something on your own because you are casually interested.

In college courses, your instructor may ask you to read articles, chapters, books, or primary sources (those original documents about which we write and study, such as letters between historic figures or the Declaration of Independence). Your instructor may want you to have a general background on a topic before you dive into that subject in class, so that you know the history of a topic, can start thinking about it, and can engage in a class discussion with more than a passing knowledge of the issue.

If you are about to participate in an in-depth six-week consideration of the U.S. Constitution but have never read it or anything written about it, you will have a hard time looking at anything in detail or understanding how and why it is significant. As you can imagine, a great deal has been written about the Constitution by scholars and citizens since the late 1700s when it was first put to paper (that’s how they did it then). While the actual document isn’t that long (about 12–15 pages depending on how it is presented), learning the details on how it came about, who was involved, and why it was and still is a significant document would take a considerable amount of time to read and digest. So, how do you do it all? Especially when you may have an instructor who drops hints that you may also love to read a historic novel covering the same time period . . . in your spare time , not required, of course! It can be daunting, especially if you are taking more than one course that has time-consuming reading lists. With a few strategic techniques, you can manage it all, but know that you must have a plan and schedule your required reading so you are also able to pick up that recommended historic novel—it may give you an entirely new perspective on the issue.

Strategies for Reading in College Disciplines

No universal law exists for how much reading instructors and institutions expect college students to undertake for various disciplines. Suffice it to say, it’s a LOT.

For most students, it is the volume of reading that catches them most off guard when they begin their college careers. A full course load might require 10–15 hours of reading per week, some of that covering content that will be more difficult than the reading for other courses.

You cannot possibly read word-for-word every single document you need to read for all your classes. That doesn’t mean you give up or decide to only read for your favorite classes or concoct a scheme to read 17 percent for each class and see how that works for you. You need to learn to skim, annotate, and take notes. All of these techniques will help you comprehend more of what you read, which is why we read in the first place. We’ll talk more later about annotating and note-taking, but for now consider what you know about skimming as opposed to active reading.

Skimming is not just glancing over the words on a page (or screen) to see if any of it sticks. Effective skimming allows you to take in the major points of a passage without the need for a time-consuming reading session that involves your active use of notations and annotations. Often you will need to engage in that painstaking level of active reading, but skimming is the first step—not an alternative to deep reading. The fact remains that neither do you need to read everything nor could you possibly accomplish that given your limited time. So learn this valuable skill of skimming as an accompaniment to your overall study tool kit, and with practice and experience, you will fully understand how valuable it is.

When you skim, look for guides to your understanding: headings, definitions, pull quotes, tables, and context clues. Textbooks are often helpful for skimming—they may already have made some of these skimming guides in bold or a different color, and chapters often follow a predictable outline. Some even provide an overview and summary for sections or chapters. Use whatever you can get, but don’t stop there. In textbooks that have some reading guides, or especially in text that does not, look for introductory words such as First or The purpose of this article . . . or summary words such as In conclusion . . . or Finally . These guides will help you read only those sentences or paragraphs that will give you the overall meaning or gist of a passage or book.

Now move to the meat of the passage. You want to take in the reading as a whole. For a book, look at the titles of each chapter if available. Read each chapter’s introductory paragraph and determine why the writer chose this particular order. Depending on what you’re reading, the chapters may be only informational, but often you’re looking for a specific argument. What position is the writer claiming? What support, counterarguments, and conclusions is the writer presenting?

Don’t think of skimming as a way to buzz through a boring reading assignment. It is a skill you should master so you can engage, at various levels, with all the reading you need to accomplish in college. End your skimming session with a few notes—terms to look up, questions you still have, and an overall summary. And recognize that you likely will return to that book or article for a more thorough reading if the material is useful.

Active Reading Strategies

Active reading differs significantly from skimming or reading for pleasure. You can think of active reading as a sort of conversation between you and the text (maybe between you and the author, but you don’t want to get the author’s personality too involved in this metaphor because that may skew your engagement with the text).

When you sit down to determine what your different classes expect you to read and you create a reading schedule to ensure you complete all the reading, think about when you should read the material strategically, not just how to get it all done . You should read textbook chapters and other reading assignments before you go into a lecture about that information. Don’t wait to see how the lecture goes before you read the material, or you may not understand the information in the lecture. Reading before class helps you put ideas together between your reading and the information you hear and discuss in class.

Different disciplines naturally have different types of texts, and you need to take this into account when you schedule your time for reading class material. For example, you may look at a poem for your world literature class and assume that it will not take you long to read because it is relatively short compared to the dense textbook you have for your economics class. But reading and understanding a poem can take a considerable amount of time when you realize you may need to stop numerous times to review the separate word meanings and how the words form images and connections throughout the poem.

The SQ3R Reading Strategy

You may have heard of the SQ3R method for active reading in your early education. This valuable technique is perfect for college reading. The title stands for S urvey, Q uestion, R ead, R ecite, R eview, and you can use the steps on virtually any assigned passage. Designed by Francis Pleasant Robinson in his 1961 book Effective Study, the active reading strategy gives readers a systematic way to work through any reading material.

Survey is similar to skimming. You look for clues to meaning by reading the titles, headings, introductions, summary, captions for graphics, and keywords. You can survey almost anything connected to the reading selection, including the copyright information, the date of the journal article, or the names and qualifications of the author(s). In this step, you decide what the general meaning is for the reading selection.

Question is your creation of questions to seek the main ideas, support, examples, and conclusions of the reading selection. Ask yourself these questions separately. Try to create valid questions about what you are about to read that have come into your mind as you engaged in the Survey step. Try turning the headings of the sections in the chapter into questions. Next, how does what you’re reading relate to you, your school, your community, and the world?

Read is when you actually read the passage. Try to find the answers to questions you developed in the previous step. Decide how much you are reading in chunks, either by paragraph for more complex readings or by section or even by an entire chapter. When you finish reading the selection, stop to make notes. Answer the questions by writing a note in the margin or other white space of the text.

You may also carefully underline or highlight text in addition to your notes. Use caution here that you don’t try to rush this step by haphazardly circling terms or the other extreme of underlining huge chunks of text. Don’t over-mark. You aren’t likely to remember what these cryptic marks mean later when you come back to use this active reading session to study. The text is the source of information—your marks and notes are just a way to organize and make sense of that information.

Recite means to speak out loud. By reciting, you are engaging other senses to remember the material—you read it (visual) and you said it (auditory). Stop reading momentarily in the step to answer your questions or clarify confusing sentences or paragraphs. You can recite a summary of what the text means to you. If you are not in a place where you can verbalize, such as a library or classroom, you can accomplish this step adequately by saying it in your head; however, to get the biggest bang for your buck, try to find a place where you can speak aloud. You may even want to try explaining the content to a friend.

Review is a recap. Go back over what you read and add more notes, ensuring you have captured the main points of the passage, identified the supporting evidence and examples, and understood the overall meaning. You may need to repeat some or all of the SQR3 steps during your review depending on the length and complexity of the material. Before you end your active reading session, write a short (no more than one page is optimal) summary of the text you read.

Reading Primary and Secondary Sources

Primary sources are original documents we study and from which we glean information; primary sources include letters, first editions of books, legal documents, and a variety of other texts. When scholars look at these documents to understand a period in history or a scientific challenge and then write about their findings, the scholar’s article is considered a secondary source. Readers have to keep several factors in mind when reading both primary and secondary sources.

Primary sources may contain dated material we now know is inaccurate. It may contain personal beliefs and biases the original writer didn’t intent to be openly published, and it may even present fanciful or creative ideas that do not support current knowledge. Readers can still gain great insight from primary sources, but readers need to understand the context from which the writer of the primary source wrote the text.

Likewise, secondary sources are inevitably another person’s perspective on the primary source, so a reader of secondary sources must also be aware of potential biases or preferences the secondary source writer inserts in the writing that may persuade an incautious reader to interpret the primary source in a particular manner.

For example, if you were to read a secondary source that is examining the U.S. Declaration of Independence (the primary source), you would have a much clearer idea of how the secondary source scholar presented the information from the primary source if you also read the Declaration for yourself instead of trusting the other writer’s interpretation. Most scholars are honest in writing secondary sources, but you as a reader of the source are trusting the writer to present a balanced perspective of the primary source. When possible, you should attempt to read a primary source in conjunction with the secondary source. The Internet helps immensely with this practice.

What Students Say

- How engaging the material is or how much I enjoy reading it.

- Whether or not the course is part of my major.

- Whether or not the instructor assesses knowledge from the reading (through quizzes, for example), or requires assignments based on the reading.

- Whether or not knowledge or information from the reading is required to participate in lecture.

- I read all of the assigned material.

- I read most of the assigned material.

- I skim the text and read the captions, examples, or summaries.

- I use a systematic method such as the Cornell method or something similar.

- I highlight or underline all the important information.

- I create outlines and/or note-cards.

- I use an app or program.

- I write notes in my text (print or digital).

- I don’t have a style. I just write down what seems important.

- I don't take many notes.

You can also take the anonymous What Students Say surveys to add your voice to this textbook. Your responses will be included in updates.

Students offered their views on these questions, and the results are displayed in the graphs below.

What is the most influential factor in how thoroughly you read the material for a given course?

What best describes your reading approach for required texts/materials for your classes?

What best describes your note-taking style?

Researching Topic and Author

During your preview stage, sometimes called pre-reading, you can easily pick up on information from various sources that may help you understand the material you’re reading more fully or place it in context with other important works in the discipline. If your selection is a book, flip it over or turn to the back pages and look for an author’s biography or note from the author. See if the book itself contains any other information about the author or the subject matter.

The main things you need to recall from your reading in college are the topics covered and how the information fits into the discipline. You can find these parts throughout the textbook chapter in the form of headings in larger and bold font, summary lists, and important quotations pulled out of the narrative. Use these features as you read to help you determine what the most important ideas are.

Remember, many books use quotations about the book or author as testimonials in a marketing approach to sell more books, so these may not be the most reliable sources of unbiased opinions, but it’s a start. Sometimes you can find a list of other books the author has written near the front of a book. Do you recognize any of the other titles? Can you do an Internet search for the name of the book or author? Go beyond the search results that want you to buy the book and see if you can glean any other relevant information about the author or the reading selection. Beyond a standard Internet search, try the library article database. These are more relevant to academic disciplines and contain resources you typically will not find in a standard search engine. If you are unfamiliar with how to use the library database, ask a reference librarian on campus. They are often underused resources that can point you in the right direction.

Understanding Your Own Preset Ideas on a Topic

Laura really enjoys learning about environmental issues. She has read many books and watched numerous televised documentaries on this topic and actively seeks out additional information on the environment. While Laura’s interest can help her understand a new reading encounter about the environment, Laura also has to be aware that with this interest, she also brings forward her preset ideas and biases about the topic. Sometimes these prejudices against other ideas relate to religion or nationality or even just tradition. Without evidence, thinking the way we always have is not a good enough reason; evidence can change, and at the very least it needs honest review and assessment to determine its validity. Ironically, we may not want to learn new ideas because that may mean we would have to give up old ideas we have already mastered, which can be a daunting prospect.

With every reading situation about the environment, Laura needs to remain open-minded about what she is about to read and pay careful attention if she begins to ignore certain parts of the text because of her preconceived notions. Learning new information can be very difficult if you balk at ideas that are different from what you’ve always thought. You may have to force yourself to listen to a different viewpoint multiple times to make sure you are not closing your mind to a viable solution your mindset does not currently allow.

Can you think of times you have struggled reading college content for a course? Which of these strategies might have helped you understand the content? Why do you think those strategies would work?

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/college-success/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Amy Baldwin

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: College Success

- Publication date: Mar 27, 2020

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/college-success/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/college-success/pages/5-2-effective-reading-strategies

© Sep 20, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

Teach the Seven Strategies of Highly Effective Readers

To improve students’ reading comprehension, teachers should introduce the seven cognitive strategies of effective readers: activating, inferring, monitoring-clarifying, questioning, searching-selecting, summarizing, and visualizing-organizing. This article includes definitions of the seven strategies and a lesson-plan template for teaching each one.

To assume that one can simply have students memorize and routinely execute a set of strategies is to misconceive the nature of strategic processing or executive control. Such rote applications of these procedures represents, in essence, a true oxymoron-non-strategic strategic processing. — Alexander and Murphy (1998, p. 33)

If the struggling readers in your content classroom routinely miss the point when “reading” content text, consider teaching them one or more of the seven cognitive strategies of highly effective readers. Cognitive strategies are the mental processes used by skilled readers to extract and construct meaning from text and to create knowledge structures in long-term memory. When these strategies are directly taught to and modeled for struggling readers, their comprehension and retention improve.

Struggling students often mistakenly believe they are reading when they are actually engaged in what researchers call mindless reading (Schooler, Reichle, & Halpern, 2004), zoning out while staring at the printed page. The opposite of mindless reading is the processing of text by highly effective readers using cognitive strategies. These strategies are described in a fascinating qualitative study that asked expert readers to think aloud regarding what was happening in their minds while they were reading. The lengthy scripts recording these spoken thoughts (i.e., think-alouds) are called verbal protocols (Pressley & Afflerbach, 1995). These protocols were categorized and analyzed by researchers to answer specific questions, such as, What is the influence of prior knowledge on expert readers’ strategies as they determine the main idea of a text? (Afflerbach, 1990b).

The protocols provide accurate “snapshots” and even “videos” of the ever-changing mental landscape that expert readers construct during reading. Researchers have concluded that reading is “constructively responsive-that is, good readers are always changing their processing in response to the text they are reading” (Pressley & Afflerbach, 1995, p. 2). Instructional Aid 1.1 defines the seven cognitive strategies of highly effective readers, and Instructional Aid 1.2 provides a lesson plan template for teaching a cognitive strategy.

Instructional aids

Liked it share it.

McEwan, 2004. 7 Strategies of Highly Effective Readers: Using Cognitive Research to Boost K-8 Achievement. Wood, Woloshyn, & Willoughby, 1995. Cognitive Strategy Instruction for Middle and High Schools.

McEwan, E.K., 40 Ways to Support Struggling Readers in Content Classrooms. Grades 6-12, pp.1-6, copyright 2007 by Corwin Press. Reprinted by permission of Corwin Press, Inc.

Visit our sister websites:

Reading rockets launching young readers (opens in a new window), start with a book read. explore. learn (opens in a new window), colorín colorado helping ells succeed (opens in a new window), ld online all about learning disabilities (opens in a new window), reading universe all about teaching reading and writing (opens in a new window).

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

1.1 Reading and Writing in College

Learning objectives.

- Understand the expectations for reading and writing assignments in college courses.

- Understand and apply general strategies to complete college-level reading assignments efficiently and effectively.

- Recognize specific types of writing assignments frequently included in college courses.

- Understand and apply general strategies for managing college-level writing assignments.

- Determine specific reading and writing strategies that work best for you individually.

As you begin this chapter, you may be wondering why you need an introduction. After all, you have been writing and reading since elementary school. You completed numerous assessments of your reading and writing skills in high school and as part of your application process for college. You may write on the job, too. Why is a college writing course even necessary?

When you are eager to get started on the coursework in your major that will prepare you for your career, getting excited about an introductory college writing course can be difficult. However, regardless of your field of study, honing your writing skills—and your reading and critical-thinking skills—gives you a more solid academic foundation.

In college, academic expectations change from what you may have experienced in high school. The quantity of work you are expected to do is increased. When instructors expect you to read pages upon pages or study hours and hours for one particular course, managing your work load can be challenging. This chapter includes strategies for studying efficiently and managing your time.

The quality of the work you do also changes. It is not enough to understand course material and summarize it on an exam. You will also be expected to seriously engage with new ideas by reflecting on them, analyzing them, critiquing them, making connections, drawing conclusions, or finding new ways of thinking about a given subject. Educationally, you are moving into deeper waters. A good introductory writing course will help you swim.

Table 1.1 “High School versus College Assignments” summarizes some of the other major differences between high school and college assignments.

Table 1.1 High School versus College Assignments

This chapter covers the types of reading and writing assignments you will encounter as a college student. You will also learn a variety of strategies for mastering these new challenges—and becoming a more confident student and writer.

Throughout this chapter, you will follow a first-year student named Crystal. After several years of working as a saleswoman in a department store, Crystal has decided to pursue a degree in elementary education and become a teacher. She is continuing to work part-time, and occasionally she finds it challenging to balance the demands of work, school, and caring for her four-year-old son. As you read about Crystal, think about how you can use her experience to get the most out of your own college experience.

Review Table 1.1 “High School versus College Assignments” and think about how you have found your college experience to be different from high school so far. Respond to the following questions:

- In what ways do you think college will be more rewarding for you as a learner?

- What aspects of college do you expect to find most challenging?

- What changes do you think you might have to make in your life to ensure your success in college?

Reading Strategies

Your college courses will sharpen both your reading and your writing skills. Most of your writing assignments—from brief response papers to in-depth research projects—will depend on your understanding of course reading assignments or related readings you do on your own. And it is difficult, if not impossible, to write effectively about a text that you have not understood. Even when you do understand the reading, it can be hard to write about it if you do not feel personally engaged with the ideas discussed.

This section discusses strategies you can use to get the most out of your college reading assignments. These strategies fall into three broad categories:

- Planning strategies. To help you manage your reading assignments.

- Comprehension strategies. To help you understand the material.

- Active reading strategies. To take your understanding to a higher and deeper level.

Planning Your Reading

Have you ever stayed up all night cramming just before an exam? Or found yourself skimming a detailed memo from your boss five minutes before a crucial meeting? The first step in handling college reading successfully is planning. This involves both managing your time and setting a clear purpose for your reading.

Managing Your Reading Time

You will learn more detailed strategies for time management in Section 1.2 “Developing Study Skills” , but for now, focus on setting aside enough time for reading and breaking your assignments into manageable chunks. If you are assigned a seventy-page chapter to read for next week’s class, try not to wait until the night before to get started. Give yourself at least a few days and tackle one section at a time.

Your method for breaking up the assignment will depend on the type of reading. If the text is very dense and packed with unfamiliar terms and concepts, you may need to read no more than five or ten pages in one sitting so that you can truly understand and process the information. With more user-friendly texts, you will be able to handle longer sections—twenty to forty pages, for instance. And if you have a highly engaging reading assignment, such as a novel you cannot put down, you may be able to read lengthy passages in one sitting.

As the semester progresses, you will develop a better sense of how much time you need to allow for the reading assignments in different subjects. It also makes sense to preview each assignment well in advance to assess its difficulty level and to determine how much reading time to set aside.

College instructors often set aside reserve readings for a particular course. These consist of articles, book chapters, or other texts that are not part of the primary course textbook. Copies of reserve readings are available through the university library; in print; or, more often, online. When you are assigned a reserve reading, download it ahead of time (and let your instructor know if you have trouble accessing it). Skim through it to get a rough idea of how much time you will need to read the assignment in full.

Setting a Purpose

The other key component of planning is setting a purpose. Knowing what you want to get out of a reading assignment helps you determine how to approach it and how much time to spend on it. It also helps you stay focused during those occasional moments when it is late, you are tired, and relaxing in front of the television sounds far more appealing than curling up with a stack of journal articles.

Sometimes your purpose is simple. You might just need to understand the reading material well enough to discuss it intelligently in class the next day. However, your purpose will often go beyond that. For instance, you might also read to compare two texts, to formulate a personal response to a text, or to gather ideas for future research. Here are some questions to ask to help determine your purpose:

How did my instructor frame the assignment? Often your instructors will tell you what they expect you to get out of the reading:

- Read Chapter 2 and come to class prepared to discuss current teaching practices in elementary math.

- Read these two articles and compare Smith’s and Jones’s perspectives on the 2010 health care reform bill.

- Read Chapter 5 and think about how you could apply these guidelines to running your own business.

- How deeply do I need to understand the reading? If you are majoring in computer science and you are assigned to read Chapter 1, “Introduction to Computer Science,” it is safe to assume the chapter presents fundamental concepts that you will be expected to master. However, for some reading assignments, you may be expected to form a general understanding but not necessarily master the content. Again, pay attention to how your instructor presents the assignment.

- How does this assignment relate to other course readings or to concepts discussed in class? Your instructor may make some of these connections explicitly, but if not, try to draw connections on your own. (Needless to say, it helps to take detailed notes both when in class and when you read.)

- How might I use this text again in the future? If you are assigned to read about a topic that has always interested you, your reading assignment might help you develop ideas for a future research paper. Some reading assignments provide valuable tips or summaries worth bookmarking for future reference. Think about what you can take from the reading that will stay with you.

Improving Your Comprehension

You have blocked out time for your reading assignments and set a purpose for reading. Now comes the challenge: making sure you actually understand all the information you are expected to process. Some of your reading assignments will be fairly straightforward. Others, however, will be longer or more complex, so you will need a plan for how to handle them.

For any expository writing —that is, nonfiction, informational writing—your first comprehension goal is to identify the main points and relate any details to those main points. Because college-level texts can be challenging, you will also need to monitor your reading comprehension. That is, you will need to stop periodically and assess how well you understand what you are reading. Finally, you can improve comprehension by taking time to determine which strategies work best for you and putting those strategies into practice.

Identifying the Main Points

In college, you will read a wide variety of materials, including the following:

- Textbooks. These usually include summaries, glossaries, comprehension questions, and other study aids.

- Nonfiction trade books. These are less likely to include the study features found in textbooks.

- Popular magazine, newspaper, or web articles. These are usually written for a general audience.

- Scholarly books and journal articles. These are written for an audience of specialists in a given field.

Regardless of what type of expository text you are assigned to read, your primary comprehension goal is to identify the main point : the most important idea that the writer wants to communicate and often states early on. Finding the main point gives you a framework to organize the details presented in the reading and relate the reading to concepts you learned in class or through other reading assignments. After identifying the main point, you will find the supporting points , the details, facts, and explanations that develop and clarify the main point.

Some texts make that task relatively easy. Textbooks, for instance, include the aforementioned features as well as headings and subheadings intended to make it easier for students to identify core concepts. Graphic features, such as sidebars, diagrams, and charts, help students understand complex information and distinguish between essential and inessential points. When you are assigned to read from a textbook, be sure to use available comprehension aids to help you identify the main points.

Trade books and popular articles may not be written specifically for an educational purpose; nevertheless, they also include features that can help you identify the main ideas. These features include the following:

- Trade books. Many trade books include an introduction that presents the writer’s main ideas and purpose for writing. Reading chapter titles (and any subtitles within the chapter) will help you get a broad sense of what is covered. It also helps to read the beginning and ending paragraphs of a chapter closely. These paragraphs often sum up the main ideas presented.

- Popular articles. Reading the headings and introductory paragraphs carefully is crucial. In magazine articles, these features (along with the closing paragraphs) present the main concepts. Hard news articles in newspapers present the gist of the news story in the lead paragraph, while subsequent paragraphs present increasingly general details.

At the far end of the reading difficulty scale are scholarly books and journal articles. Because these texts are written for a specialized, highly educated audience, the authors presume their readers are already familiar with the topic. The language and writing style is sophisticated and sometimes dense.

When you read scholarly books and journal articles, try to apply the same strategies discussed earlier. The introduction usually presents the writer’s thesis , the idea or hypothesis the writer is trying to prove. Headings and subheadings can help you understand how the writer has organized support for his or her thesis. Additionally, academic journal articles often include a summary at the beginning, called an abstract, and electronic databases include summaries of articles, too.

For more information about reading different types of texts, see Chapter 12 “Writing a Research Paper” .

Monitoring Your Comprehension

Finding the main idea and paying attention to text features as you read helps you figure out what you should know. Just as important, however, is being able to figure out what you do not know and developing a strategy to deal with it.

Textbooks often include comprehension questions in the margins or at the end of a section or chapter. As you read, stop occasionally to answer these questions on paper or in your head. Use them to identify sections you may need to reread, read more carefully, or ask your instructor about later.

Even when a text does not have built-in comprehension features, you can actively monitor your own comprehension. Try these strategies, adapting them as needed to suit different kinds of texts:

- Summarize. At the end of each section, pause to summarize the main points in a few sentences. If you have trouble doing so, revisit that section.

- Ask and answer questions. When you begin reading a section, try to identify two to three questions you should be able to answer after you finish it. Write down your questions and use them to test yourself on the reading. If you cannot answer a question, try to determine why. Is the answer buried in that section of reading but just not coming across to you? Or do you expect to find the answer in another part of the reading?

- Do not read in a vacuum. Look for opportunities to discuss the reading with your classmates. Many instructors set up online discussion forums or blogs specifically for that purpose. Participating in these discussions can help you determine whether your understanding of the main points is the same as your peers’.

These discussions can also serve as a reality check. If everyone in the class struggled with the reading, it may be exceptionally challenging. If it was a breeze for everyone but you, you may need to see your instructor for help.

As a working mother, Crystal found that the best time to get her reading done was in the evening, after she had put her four-year-old to bed. However, she occasionally had trouble concentrating at the end of a long day. She found that by actively working to summarize the reading and asking and answering questions, she focused better and retained more of what she read. She also found that evenings were a good time to check the class discussion forums that a few of her instructors had created.

Choose any text that that you have been assigned to read for one of your college courses. In your notes, complete the following tasks:

- Summarize the main points of the text in two to three sentences.

- Write down two to three questions about the text that you can bring up during class discussion.

Students are often reluctant to seek help. They feel like doing so marks them as slow, weak, or demanding. The truth is, every learner occasionally struggles. If you are sincerely trying to keep up with the course reading but feel like you are in over your head, seek out help. Speak up in class, schedule a meeting with your instructor, or visit your university learning center for assistance.

Deal with the problem as early in the semester as you can. Instructors respect students who are proactive about their own learning. Most instructors will work hard to help students who make the effort to help themselves.

Taking It to the Next Level: Active Reading

Now that you have acquainted (or reacquainted) yourself with useful planning and comprehension strategies, college reading assignments may feel more manageable. You know what you need to do to get your reading done and make sure you grasp the main points. However, the most successful students in college are not only competent readers but active, engaged readers.

Using the SQ3R Strategy

One strategy you can use to become a more active, engaged reader is the SQ3R strategy , a step-by-step process to follow before, during, and after reading. You may already use some variation of it. In essence, the process works like this:

- Survey the text in advance.

- Form questions before you start reading.

- Read the text.

- Recite and/or record important points during and after reading.

- Review and reflect on the text after you read.

Before you read, you survey, or preview, the text. As noted earlier, reading introductory paragraphs and headings can help you begin to figure out the author’s main point and identify what important topics will be covered. However, surveying does not stop there. Look over sidebars, photographs, and any other text or graphic features that catch your eye. Skim a few paragraphs. Preview any boldfaced or italicized vocabulary terms. This will help you form a first impression of the material.

Next, start brainstorming questions about the text. What do you expect to learn from the reading? You may find that some questions come to mind immediately based on your initial survey or based on previous readings and class discussions. If not, try using headings and subheadings in the text to formulate questions. For instance, if one heading in your textbook reads “Medicare and Medicaid,” you might ask yourself these questions:

- When was Medicare and Medicaid legislation enacted? Why?

- What are the major differences between these two programs?

Although some of your questions may be simple factual questions, try to come up with a few that are more open-ended. Asking in-depth questions will help you stay more engaged as you read.

The next step is simple: read. As you read, notice whether your first impressions of the text were correct. Are the author’s main points and overall approach about the same as what you predicted—or does the text contain a few surprises? Also, look for answers to your earlier questions and begin forming new questions. Continue to revise your impressions and questions as you read.

While you are reading, pause occasionally to recite or record important points. It is best to do this at the end of each section or when there is an obvious shift in the writer’s train of thought. Put the book aside for a moment and recite aloud the main points of the section or any important answers you found there. You might also record ideas by jotting down a few brief notes in addition to, or instead of, reciting aloud. Either way, the physical act of articulating information makes you more likely to remember it.

After you have completed the reading, take some time to review the material more thoroughly. If the textbook includes review questions or your instructor has provided a study guide, use these tools to guide your review. You will want to record information in a more detailed format than you used during reading, such as in an outline or a list.

As you review the material, reflect on what you learned. Did anything surprise you, upset you, or make you think? Did you find yourself strongly agreeing or disagreeing with any points in the text? What topics would you like to explore further? Jot down your reflections in your notes. (Instructors sometimes require students to write brief response papers or maintain a reading journal. Use these assignments to help you reflect on what you read.)

Choose another text that that you have been assigned to read for a class. Use the SQ3R process to complete the reading. (Keep in mind that you may need to spread the reading over more than one session, especially if the text is long.)

Be sure to complete all the steps involved. Then, reflect on how helpful you found this process. On a scale of one to ten, how useful did you find it? How does it compare with other study techniques you have used?

Using Other Active Reading Strategies

The SQ3R process encompasses a number of valuable active reading strategies: previewing a text, making predictions, asking and answering questions, and summarizing. You can use the following additional strategies to further deepen your understanding of what you read.

- Connect what you read to what you already know. Look for ways the reading supports, extends, or challenges concepts you have learned elsewhere.

- Relate the reading to your own life. What statements, people, or situations relate to your personal experiences?

- Visualize. For both fiction and nonfiction texts, try to picture what is described. Visualizing is especially helpful when you are reading a narrative text, such as a novel or a historical account, or when you read expository text that describes a process, such as how to perform cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

- Pay attention to graphics as well as text. Photographs, diagrams, flow charts, tables, and other graphics can help make abstract ideas more concrete and understandable.

- Understand the text in context. Understanding context means thinking about who wrote the text, when and where it was written, the author’s purpose for writing it, and what assumptions or agendas influenced the author’s ideas. For instance, two writers might both address the subject of health care reform, but if one article is an opinion piece and one is a news story, the context is different.

- Plan to talk or write about what you read. Jot down a few questions or comments in your notebook so you can bring them up in class. (This also gives you a source of topic ideas for papers and presentations later in the semester.) Discuss the reading on a class discussion board or blog about it.

As Crystal began her first semester of elementary education courses, she occasionally felt lost in a sea of new terms and theories about teaching and child development. She found that it helped to relate the reading to her personal observations of her son and other kids she knew.

Writing at Work

Many college courses require students to participate in interactive online components, such as a discussion forum, a page on a social networking site, or a class blog. These tools are a great way to reinforce learning. Do not be afraid to be the student who starts the discussion.

Remember that when you interact with other students and teachers online, you need to project a mature, professional image. You may be able to use an informal, conversational tone, but complaining about the work load, using off-color language, or “flaming” other participants is inappropriate.

Active reading can benefit you in ways that go beyond just earning good grades. By practicing these strategies, you will find yourself more interested in your courses and better able to relate your academic work to the rest of your life. Being an interested, engaged student also helps you form lasting connections with your instructors and with other students that can be personally and professionally valuable. In short, it helps you get the most out of your education.

Common Writing Assignments

College writing assignments serve a different purpose than the typical writing assignments you completed in high school. In high school, teachers generally focus on teaching you to write in a variety of modes and formats, including personal writing, expository writing, research papers, creative writing, and writing short answers and essays for exams. Over time, these assignments help you build a foundation of writing skills.

In college, many instructors will expect you to already have that foundation.