The Essay: History and Definition

Attempts at Defining Slippery Literary Form

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

"One damned thing after another" is how Aldous Huxley described the essay: "a literary device for saying almost everything about almost anything."

As definitions go, Huxley's is no more or less exact than Francis Bacon's "dispersed meditations," Samuel Johnson's "loose sally of the mind" or Edward Hoagland's "greased pig."

Since Montaigne adopted the term "essay" in the 16th century to describe his "attempts" at self-portrayal in prose , this slippery form has resisted any sort of precise, universal definition. But that won't an attempt to define the term in this brief article.

In the broadest sense, the term "essay" can refer to just about any short piece of nonfiction -- an editorial, feature story, critical study, even an excerpt from a book. However, literary definitions of a genre are usually a bit fussier.

One way to start is to draw a distinction between articles , which are read primarily for the information they contain, and essays, in which the pleasure of reading takes precedence over the information in the text . Although handy, this loose division points chiefly to kinds of reading rather than to kinds of texts. So here are some other ways that the essay might be defined.

Standard definitions often stress the loose structure or apparent shapelessness of the essay. Johnson, for example, called the essay "an irregular, indigested piece, not a regular and orderly performance."

True, the writings of several well-known essayists ( William Hazlitt and Ralph Waldo Emerson , for instance, after the fashion of Montaigne) can be recognized by the casual nature of their explorations -- or "ramblings." But that's not to say that anything goes. Each of these essayists follows certain organizing principles of his own.

Oddly enough, critics haven't paid much attention to the principles of design actually employed by successful essayists. These principles are rarely formal patterns of organization , that is, the "modes of exposition" found in many composition textbooks. Instead, they might be described as patterns of thought -- progressions of a mind working out an idea.

Unfortunately, the customary divisions of the essay into opposing types -- formal and informal, impersonal and familiar -- are also troublesome. Consider this suspiciously neat dividing line drawn by Michele Richman:

Post-Montaigne, the essay split into two distinct modalities: One remained informal, personal, intimate, relaxed, conversational and often humorous; the other, dogmatic, impersonal, systematic and expository .

The terms used here to qualify the term "essay" are convenient as a kind of critical shorthand, but they're imprecise at best and potentially contradictory. Informal can describe either the shape or the tone of the work -- or both. Personal refers to the stance of the essayist, conversational to the language of the piece, and expository to its content and aim. When the writings of particular essayists are studied carefully, Richman's "distinct modalities" grow increasingly vague.

But as fuzzy as these terms might be, the qualities of shape and personality, form and voice, are clearly integral to an understanding of the essay as an artful literary kind.

Many of the terms used to characterize the essay -- personal, familiar, intimate, subjective, friendly, conversational -- represent efforts to identify the genre's most powerful organizing force: the rhetorical voice or projected character (or persona ) of the essayist.

In his study of Charles Lamb , Fred Randel observes that the "principal declared allegiance" of the essay is to "the experience of the essayistic voice." Similarly, British author Virginia Woolf has described this textual quality of personality or voice as "the essayist's most proper but most dangerous and delicate tool."

Similarly, at the beginning of "Walden, " Henry David Thoreau reminds the reader that "it is ... always the first person that is speaking." Whether expressed directly or not, there's always an "I" in the essay -- a voice shaping the text and fashioning a role for the reader.

Fictional Qualities

The terms "voice" and "persona" are often used interchangeably to suggest the rhetorical nature of the essayist himself on the page. At times an author may consciously strike a pose or play a role. He can, as E.B. White confirms in his preface to "The Essays," "be any sort of person, according to his mood or his subject matter."

In "What I Think, What I Am," essayist Edward Hoagland points out that "the artful 'I' of an essay can be as chameleon as any narrator in fiction." Similar considerations of voice and persona lead Carl H. Klaus to conclude that the essay is "profoundly fictive":

It seems to convey the sense of human presence that is indisputably related to its author's deepest sense of self, but that is also a complex illusion of that self -- an enactment of it as if it were both in the process of thought and in the process of sharing the outcome of that thought with others.

But to acknowledge the fictional qualities of the essay isn't to deny its special status as nonfiction.

Reader's Role

A basic aspect of the relationship between a writer (or a writer's persona) and a reader (the implied audience ) is the presumption that what the essayist says is literally true. The difference between a short story, say, and an autobiographical essay lies less in the narrative structure or the nature of the material than in the narrator's implied contract with the reader about the kind of truth being offered.

Under the terms of this contract, the essayist presents experience as it actually occurred -- as it occurred, that is, in the version by the essayist. The narrator of an essay, the editor George Dillon says, "attempts to convince the reader that its model of experience of the world is valid."

In other words, the reader of an essay is called on to join in the making of meaning. And it's up to the reader to decide whether to play along. Viewed in this way, the drama of an essay might lie in the conflict between the conceptions of self and world that the reader brings to a text and the conceptions that the essayist tries to arouse.

At Last, a Definition—of Sorts

With these thoughts in mind, the essay might be defined as a short work of nonfiction, often artfully disordered and highly polished, in which an authorial voice invites an implied reader to accept as authentic a certain textual mode of experience.

Sure. But it's still a greased pig.

Sometimes the best way to learn exactly what an essay is -- is to read some great ones. You'll find more than 300 of them in this collection of Classic British and American Essays and Speeches .

- What is a Familiar Essay in Composition?

- What Does "Persona" Mean?

- What Are the Different Types and Characteristics of Essays?

- Rhetorical Analysis Definition and Examples

- What Is a Personal Essay (Personal Statement)?

- The Writer's Voice in Literature and Rhetoric

- Point of View in Grammar and Composition

- What Is Colloquial Style or Language?

- What Is Literary Journalism?

- Definition and Examples of Formal Essays

- What Is Expository Writing?

- The Difference Between an Article and an Essay

- First-Person Point of View

- What Is Tone In Writing?

- An Introduction to Literary Nonfiction

- Campus Library Info.

- ARC Homepage

- Library Resources

- Articles & Databases

- Books & Ebooks

Baker College Research Guides

- Research Guides

- General Education

COM 1010: Composition and Critical Thinking I

- Understanding Genre and Genre Analysis

- The Writing Process

- Essay Organization Help

- Understanding Memoir

- What is a Book Cover (Not an Infographic)?

- Understanding PowerPoint and Presentations

- Understanding Summary

- What is a Response?

- Structuring Sides of a Topic

- Locating Sources

- What is an Annotated Bibliography?

- What is a Peer Review?

- Understanding Images

- What is Literacy?

- What is an Autobiography?

- Shifting Genres

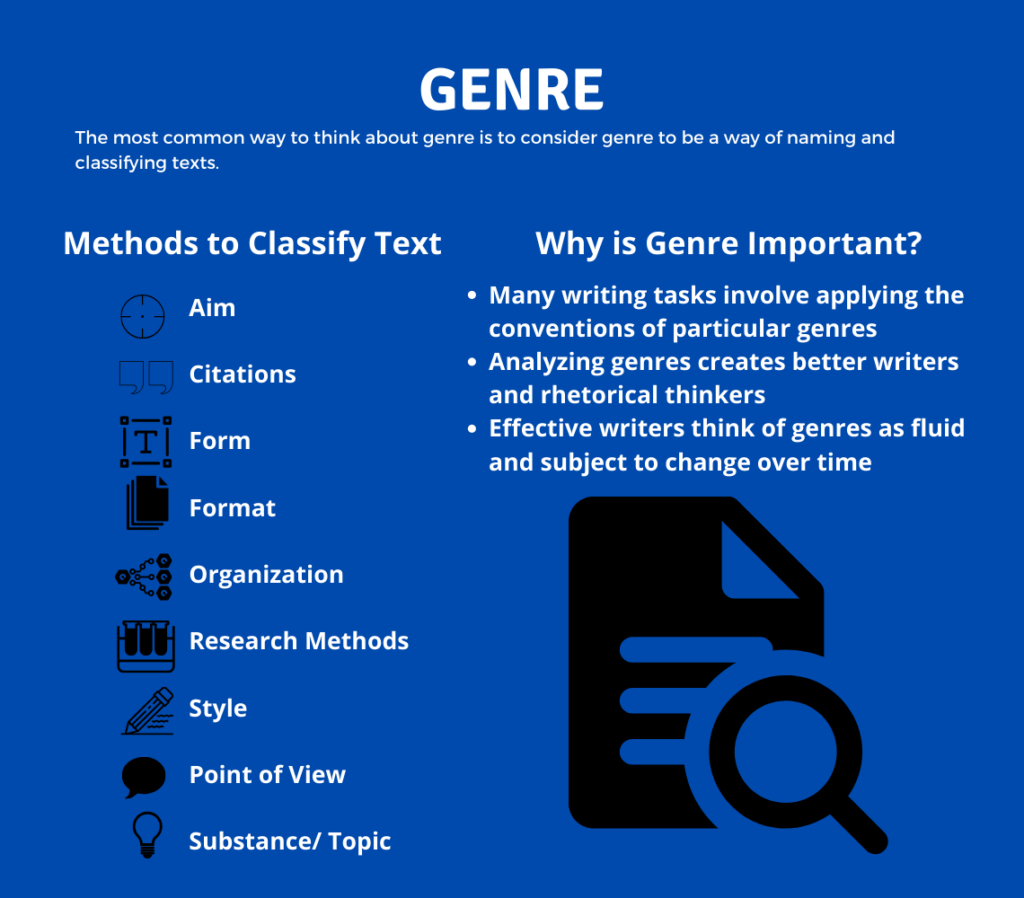

Understanding What is Meant by the Word "Genre"

What do we mean by genre? This means a type of writing, i.e., an essay, a poem, a recipe, an email, a tweet. These are all different types (or categories) of writing, and each one has its own format, type of words, tone, and so on. Analyzing a type of writing (or genre) is considered a genre analysis project. A genre analysis grants students the means to think critically about how a particular form of communication functions as well as a means to evaluate it.

Every genre (type of writing/writing style) has a set of conventions that allow that particular genre to be unique. These conventions include the following components:

- Tone: tone of voice, i.e. serious, humorous, scholarly, informal.

- Diction : word usage - formal or informal, i.e. “disoriented” (formal) versus “spaced out” (informal or colloquial).

- Content : what is being discussed/demonstrated in the piece? What information is included or needs to be included?

- Style / Format (the way it looks): long or short sentences? Bulleted list? Paragraphs? Short-hand? Abbreviations? Does punctuation and grammar matter? How detailed do you need to be? Single-spaced or double-spaced? Can pictures / should pictures be included? How long does it need to be / should be? What kind of organizational requirements are there?

- Expected Medium of Genre : where does the genre appear? Where is it created? i.e. can be it be online (digital) or does it need to be in print (computer paper, magazine, etc)? Where does this genre occur? i.e. flyers (mostly) occur in the hallways of our school, and letters of recommendation (mostly) occur in professors’ offices.

- Genre creates an expectation in the minds of its audience and may fail or succeed depending on if that expectation is met or not.

- Many genres have built-in audiences and corresponding publications that support them, such as magazines and websites.

- The goal of the piece that is written, i.e. a newspaper entry is meant to inform and/or persuade, and a movie script is meant to entertain.

- Basically, each genre has a specific task or a specific goal that it is created to attain.

- Understanding Genre

- Understanding the Rhetorical Situation

To understand genre, one has to first understand the rhetorical situation of the communication.

Below are some additional resources to assist you in this process:

- Reading and Writing for College

Genre Analysis

Genre analysis: A tool used to create genre awareness and understand the conventions of new writing situations and contexts. This a llows you to make effective communication choices and approach your audience and rhetorical situation appropriately

Basically, when we say "genre analysis," that is a fancy way of saying that we are going to look at similar pieces of communication - for example a handful of business memos - and determine the following:

- Tone: What was the overall tone of voice in the samples of that genre (piece of writing)?

- Diction : What was the overall type of writing in the three samples of that genre (piece of writing)? Formal or informal?

- Content : What types(s) of information is shared in those pieces of writing?

- Style / Format (the way it looks): Do the pieces of communication contain long or short sentences? Bulleted list? Paragraphs? Abbreviations? Does punctuation and grammar matter? How detailed do you need to be in that type of writing style? Single-spaced or double-spaced? Are pictures included? If so, why? How long does it need to be / should be? What kind of organizational requirements are there?

- Expected Medium of Genre : Where did the pieces appear? Were they online? Where? Were they in a printed, physical context? If so, what?

- Audience: What audience is this piece of writing trying to reach?

- Purpose : What is the goal of the piece of writing? What is its purpose? Example: the goal of the piece that is written, i.e. a newspaper entry is meant to inform and/or persuade, and a movie script is meant to entertain.

In other words, we are analyzing the genre to determine what are some commonalities of that piece of communication.

For additional help, see the following resource for Questions to Ask When Completing a Genre Analysis .

- << Previous: The Writing Process

- Next: Essay Organization Help >>

- Last Updated: Feb 23, 2024 2:08 PM

- URL: https://guides.baker.edu/com1010

- Search this Guide Search

What is Essay? Definition, Usage, and Literary Examples

Essay definition.

An essay (ES-ey) is a nonfiction composition that explores a concept, argument, idea, or opinion from the personal perspective of the writer. Essays are usually a few pages, but they can also be book-length. Unlike other forms of nonfiction writing, like textbooks or biographies, an essay doesn’t inherently require research. Literary essayists are conveying ideas in a more informal way.

The word essay comes from the Late Latin exigere , meaning “ascertain or weigh,” which later became essayer in Old French. The late-15th-century version came to mean “test the quality of.” It’s this latter derivation that French philosopher Michel de Montaigne first used to describe a composition.

History of the Essay

Michel de Montaigne first coined the term essayer to describe Plutarch’s Oeuvres Morales , which is now widely considered to be a collection of essays. Under the new term, Montaigne wrote the first official collection of essays, Essais , in 1580. Montaigne’s goal was to pen his personal ideas in prose . In 1597, a collection of Francis Bacon’s work appeared as the first essay collection written in English. The term essayist was first used by English playwright Ben Jonson in 1609.

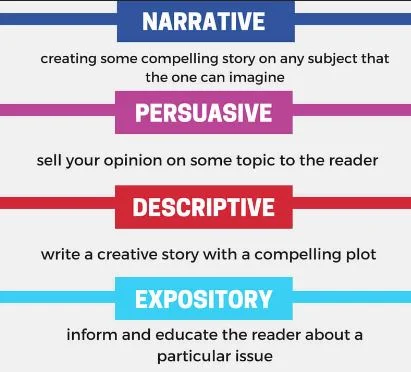

Types of Essays

There are many ways to categorize essays. Aldous Huxley, a leading essayist, determined that there are three major groups: personal and autobiographical, objective and factual, and abstract and universal. Within these groups, several other types can exist, including the following:

- Academic Essays : Educators frequently assign essays to encourage students to think deeply about a given subject and to assess the student’s knowledge. As such, an academic essay employs a formal language and tone, and it may include references and a bibliography. It’s objective and factual, and it typically uses a five-paragraph model of an introduction, two or more body paragraphs, and a conclusion. Several other essay types, like descriptive, argumentative, and expository, can fall under the umbrella of an academic essay.

- Analytical Essays : An analytical essay breaks down and interprets something, like an event, piece of literature, or artwork. This type of essay combines abstraction and personal viewpoints. Professional reviews of movies, TV shows, and albums are likely the most common form of analytical essays that people encounter in everyday life.

- Argumentative/Persuasive Essays : In an argumentative or persuasive essay, the essayist offers their opinion on a debatable topic and refutes opposing views. Their goal is to get the reader to agree with them. Argumentative/persuasive essays can be personal, factual, and even both at the same time. They can also be humorous or satirical; Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal is a satirical essay arguing that the best way for Irish people to get out of poverty is to sell their children to rich people as a food source.

- Descriptive Essays : In a descriptive essay, the essayist describes something, someone, or an event in great detail. The essay’s subject can be something concrete, meaning it can be experienced with any or all of the five senses, or abstract, meaning it can’t be interacted with in a physical sense.

- Expository Essay : An expository essay is a factual piece of writing that explains a particular concept or issue. Investigative journalists often write expository essays in their beat, and things like manuals or how-to guides are also written in an expository style.

- Narrative/Personal : In a narrative or personal essay, the essayist tells a story, which is usually a recounting of a personal event. Narrative and personal essays may attempt to support a moral or lesson. People are often most familiar with this category as many writers and celebrities frequently publish essay collections.

Notable Essayists

- James Baldwin, “ Notes of a Native Son ”

- Joan Didion, “ Goodbye To All That ”

- George Orwell, “ Shooting an Elephant ”

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, “ Self-Reliance ”

- Virginia Woolf, " Three Guineas "

Examples of Literary Essays

1. Michel De Montaigne, “Of Presumption”

De Montaigne’s essay explores multiple topics, including his reasons for writing essays, his dissatisfaction with contemporary education, and his own victories and failings. As the father of the essay, Montaigne details characteristics of what he thinks an essay should be. His writing has a stream-of-consciousness organization that doesn’t follow a structure, and he expresses the importance of looking inward at oneself, pointing to the essay’s personal nature.

2. Virginia Woolf, “A Room of One’s Own”

Woolf’s feminist essay, written from the perspective of an unknown, fictional woman, argues that sexism keeps women from fully realizing their potential. Woolf posits that a woman needs only an income and a room of her own to express her creativity. The fictional persona Woolf uses is meant to teach the reader a greater truth: making both literal and metaphorical space for women in the world is integral to their success and wellbeing.

3. James Baldwin, “Everybody’s Protest Novel”

In this essay, Baldwin argues that Harriet Beecher Stowe’s novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin doesn’t serve the black community the way his contemporaries thought it did. He points out that it equates “goodness” with how well-assimilated the black characters are in white culture:

Uncle Tom’s Cabin is a very bad novel, having, in its self-righteous, virtuous sentimentality, much in common with Little Women. Sentimentality […] is the mark of dishonesty, the inability to feel; […] and it is always, therefore, the signal of secret and violent inhumanity, the mask of cruelty.

This essay is both analytical and argumentative. Baldwin analyzes the novel and argues against those who champion it.

Further Resources on Essays

Top Writing Tips offers an in-depth history of the essay.

The Harvard Writing Center offers tips on outlining an essay.

We at SuperSummary have an excellent essay writing resource guide .

Related Terms

- Academic Essay

- Argumentative Essay

- Expository Essay

- Narrative Essay

- Persuasive Essay

Definition of Essay

Essay is derived from the French word essayer , which means “ to attempt ,” or “ to try .” An essay is a short form of literary composition based on a single subject matter, and often gives the personal opinion of the author. A famous English essayist, Aldous Huxley defines essays as, “a literary device for saying almost everything about almost anything. ” The Oxford Dictionary describes it as “ a short piece of writing on a particular subject. ” In simple words, we can define it as a scholarly work in writing that provides the author’s personal argument .

- Types of Essay

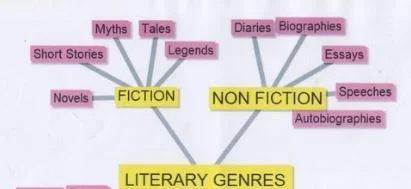

There are two forms of essay: literary and non-literary. Literary essays are of four types:

- Expository Essay – In an expository essay , the writer gives an explanation of an idea, theme , or issue to the audience by giving his personal opinions. This essay is presented through examples, definitions, comparisons, and contrast .

- Descriptive Essay – As it sounds, this type of essay gives a description about a particular topic, or describes the traits and characteristics of something or a person in detail. It allows artistic freedom, and creates images in the minds of readers through the use of the five senses.

- Narrative Essay – Narrative essay is non- fiction , but describes a story with sensory descriptions. The writer not only tells a story, but also makes a point by giving reasons.

- Persuasive Essay – In this type of essay, the writer tries to convince his readers to adopt his position or point of view on an issue, after he provides them solid reasoning in this connection. It requires a lot of research to claim and defend an idea. It is also called an argumentative essay .

Non-literary essays could also be of the same types but they could be written in any format.

Examples of Essay in Literature

Example #1: the sacred grove of oshogbo (by jeffrey tayler).

“As I passed through the gates I heard a squeaky voice . A diminutive middle-aged man came out from behind the trees — the caretaker. He worked a toothbrush-sized stick around in his mouth, digging into the crevices between algae’d stubs of teeth. He was barefoot; he wore a blue batik shirt known as a buba, baggy purple trousers, and an embroidered skullcap. I asked him if he would show me around the shrine. Motioning me to follow, he spat out the results of his stick work and set off down the trail.”

This is an example of a descriptive essay , as the author has used descriptive language to paint a dramatic picture for his readers of an encounter with a stranger.

Example #2: Of Love (By Francis Bacon)

“It is impossible to love, and be wise … Love is a child of folly. … Love is ever rewarded either with the reciprocal, or with an inward and secret contempt. You may observe that amongst all the great and worthy persons…there is not one that hath been transported to the mad degree of love: which shows that great spirits and great business do keep out this weak passion…That he had preferred Helena, quitted the gifts of Juno and Pallas. For whosoever esteemeth too much of amorous affection quitted both riches and wisdom.”

In this excerpt, Bacon attempts to persuade readers that people who want to be successful in this world must never fall in love. By giving an example of famous people like Paris, who chose Helen as his beloved but lost his wealth and wisdom, the author attempts to convince the audience that they can lose their mental balance by falling in love.

Example #3: The Autobiography of a Kettle (By John Russell)

“ I am afraid I do not attract attention, and yet there is not a single home in which I could done without. I am only a small, black kettle but I have much to interest me, for something new happens to me every day. The kitchen is not always a cheerful place in which to live, but still I find plenty of excitement there, and I am quite happy and contented with my lot …”

In this example, the author is telling an autobiography of a kettle, and describes the whole story in chronological order. The author has described the kettle as a human being, and allows readers to feel, as he has felt.

Function of Essay

The function of an essay depends upon the subject matter, whether the writer wants to inform, persuade, explain, or entertain. In fact, the essay increases the analytical and intellectual abilities of the writer as well as readers. It evaluates and tests the writing skills of a writer, and organizes his or her thinking to respond personally or critically to an issue. Through an essay, a writer presents his argument in a more sophisticated manner. In addition, it encourages students to develop concepts and skills, such as analysis, comparison and contrast, clarity, exposition , conciseness, and persuasion .

Related posts:

- Elements of an Essay

- Narrative Essay

- Definition Essay

- Descriptive Essay

- Analytical Essay

- Argumentative Essay

- Cause and Effect Essay

- Critical Essay

- Expository Essay

- Persuasive Essay

- Process Essay

- Explicatory Essay

- An Essay on Man: Epistle I

- Comparison and Contrast Essay

Post navigation

- Have your assignments done by seasoned writers. 24/7

- Contact us:

- +1 (213) 221-0069

- [email protected]

Is Essay a Genre of Literature: Its Structure and Examples

Is Essay a Genre

Essays are one of the many different kinds of texts that students are required to write in their academic journey. Along with other texts such as laboratory writings, research proposals, book reviews, case studies, and others, they can be referred to as genres.

These genres can be easily constructed from a small range into different types of texts. For example, essay questions can be answered in different ways using different answer formats.

People Also Read: How to Censor Words in an Essay: Bad Words in Academic Papers

Is Essay a Genre?

An essay is a genre of writing because essays are a type of academic writing classification. They are a flexible small genre of literature and part of human communication that seeks to express one’s views, argument, or thesis by backing it up with personal or external sources.

They serve purposes such as introducing topics to wide audiences, applying for college and university admissions, and being part of future novels.

Essays have also been selected as common elements of the education process in a lot of countries. They are a very good way of testing the ability and diligence of students.

Also, they are divided into several types with common ones including argumentative, descriptive, expository, and comparative essays.

Reasons Making Essay a Genre in Writing

Essays are genres in writing because they are opinions in which reflections, critiques, personal impressions, and ideas are exposed to evaluate different themes .

These themes are also deeply analyzed and interpreted implying that essays are genres that are rehearsed. Questions on different subjects are problematized based on the writer’s general opinions and conclusions made.

Additionally, essays are a genre because they present attempts at the critical decision and personal point of view in a natural flow of ideas that is required in the academic world.

Thoughts Why Essays Are Not Really a Genre

Essays cannot be considered as writing genres when they are written with no purpose or audience. Almost every writing in the academic world is regarded as an essay .

Even pointless writings that were just written without any aim are considered essays. However, these essays cannot be regarded as genres. An essay that will not be read by an audience cannot be a genre of academic writing.

This means that any form of writing that is not marked by instructors or used for academic purposes cannot be classified as a genre of writing.

People Also Read: How to Write an Ethnography Essay or Research Paper

Main Genres in Academic Writing

1. research paper.

A research paper is the end product of the culmination of critical thinking, research, organization, composition, and source evaluation.

You can explain it as a child growing after as a writer interprets, evaluates, and explores specific sources. It is a genre of writing that depends on the support and interaction of primary and secondary sources.

When every research paper is done, it furthers the field of the topic and provides students with opportunities to increase their knowledge of that particular topic.

The two main types of research papers are argumentative and analytical research papers. Analytical essays ask questions, explore and evaluate the topics while argumentative essay introduces a controversial topic in which the writer is needed to take a stance that will be supported in the essay.

2. Dissertations

A dissertation is a long piece of academic writing based on research that is submitted for Ph.D. and sometimes for Master’s degree purposes.

One purpose of writing dissertations is to make scholarly arguments. For example, dissertations in humanities will have to include evidence that you have gathered from credible books and articles.

Also, dissertations should show that you have done your work. They are crucial in ensuring that graduates get the stamp of approval for their degree credentials from their institutions.

Dissertations are written to professors in various academic departments who have high expertise in different areas of specialization. They are the ones who determine whether students have passed or not.

A thesis is a paper that identifies a specific research question and answers it fully. It includes a thesis statement that provides the stand taken on the research question.

This paper is written mostly by Master’s students after taking core courses in the first half of their program.

It is a culmination of learning to show that the students can easily comprehend and apply theories, practices, principles, and the codes of ethics in a particular field of study.

Report writing is a way of elaborating on a topic formally. The audience is always a thought-out section. For example, a report can be written about a business case or school event.

The main purpose of writing a report is to inform the reader about something without the personal input of the writer on that topic. Therefore, reports only portray facts., charts, solid analysis, data, and tables.

Knowing the audience’s motives is very important because it sets out the set of facts that will be focused on in the report.

5. Field Projects

Field projects involve the integration of theory and practice. As a result, students are allowed to work and write on real-world challenges. The issues that these projects deal with mostly include those of critical aspects of society.

Students research, analyse, and give recommendations on the issues of priority to advance the goals of field project partners. The purpose of these projects is to provide the students with unique learning opportunities where practical first-hand practice in the different professional fields is provided.

The audiences of these projects are the supervisors who often check their programs and grade them after the completion of the project period.

People Also Read: Is an essay formal or informal: characteristics of each

Frequently Asked Questions

What genres of essays are there.

There are four genres of essays. These include exposition, narration, argumentation, and description. These are the type of tasks that are common in essay writing assignments in most institutions.

Therefore, students must understand how to write essays belonging to each of the four genres.

What is an essay in writing?

An essay is a piece of writing that outlines the writer’s views and opinions on a certain story. Essays try to convince the readers about something by shedding light on it through thorough information.

To convince readers, essays must have several components that make them flow logically. These include the introduction, body paragraphs, and conclusion.

Are ALL essays persuasive?

There are different types of essays with each requiring a different approach angle. Persuasive essays differ from other essay types in that they are designed to involve arguments that serve the purpose of making the reader agree with the writer’s point of view.

An argument is made on a single subject or a particular viewpoint and the writer provides evidence that will aid in persuading the reader.

Apart from persuasive essays, others include argumentative essays, descriptive essays, expository essays, and many more.

Is essay fiction or nonfiction?

Essays are nonfiction because the writer is attempting to tell the truth about something.

Essays are not like fictional short stories. For example, in descriptive essays, the writer must dive into deep research on credible information that tells the truth about a certain topic.

Also, in argumentative essays, the writers must show evidence of why they are in favor of a particular point of view

How do you identify a genre in literature?

To identify a genre in literature you will need to identify the tone of writing, the style of writing, the techniques used in the narrative, the length of the essay, and the content of the essay.

Content includes what the essay is all about. It is the aim or main point that the essay tries to prove.

What is the difference between essay and literary forms?

Literary form is the style or manner of constructing, coordinating, and arranging parts of compositions such as poems, novels, and television shows scripts while essays are pieces of writing that just inform the reader about a certain topic.

With over 10 years in academia and academic assistance, Alicia Smart is the epitome of excellence in the writing industry. She is our chief editor and in charge of the writing department at Grade Bees.

Related posts

Titles for Essay about Yourself

Good Titles for Essays about yourself: 31 Personal Essay Topics

How to Write a Diagnostic Essay

How to Write a Diagnostic Essay: Meaning and Topics Example

How Scantron Detects Cheating

Scantron Cheating: How it Detects Cheating and Tricks Students Use

7.3 Glance at Genre: Criteria, Evidence, Evaluation

Learning outcomes.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify and define common characteristics, mediums, key terms, and features of the review genre.

- Identify criteria and evidence to support reviews of different primary sources.

Reviews vary in style and content according to the subject, the writer, and the medium. The following are characteristics most frequently found in reviews:

- Focused subject : The subject of the review is specific and focuses on one item or idea. For example, a review of all Marvel Cinematic Universe movies could not be contained in the scope of a single essay or published review not only because of length but also because of the differences among them. Choosing one specific item to review—a single film or single topic across films, for instance—will allow you to provide a thorough evaluation of the subject.

- Judgment or evaluation: Reviewers need to deliver a clear judgment or evaluation to share with readers their thoughts on the subject and why they would or would not recommend it. An evaluation can be direct and explicit, or it can be indirect and subtle.

- Specific evidence : All reviews need specific evidence to support the evaluation. Typically, this evidence comes in the form of quotations and vivid descriptions from the primary source, or subject of the review. Reviewers often use secondary sources —works about the primary source — to support their claims or provide context.

- Context : Reviewers provide context, such as relevant historical or cultural background, current events, or short biographical sketches, that help readers understand both the primary source and the review.

- Tone : Writers of effective reviews tend to maintain a professional, unbiased tone—attitude toward the subject. Although many reviewers try to avoid sarcasm and dismissiveness, you will find these elements present in professional reviews, especially those in which critics pan the primary source.

These are some key terms to know and use when writing a review:

- Analysis : detailed examination of the parts of a whole or of the whole itself.

- Connotation: implied feelings or thoughts associated with a word. Connotations can be positive or negative. Reviewers often use words with strong positive or negative connotations that support their praise or criticism. For example, a writer may refer to a small space positively as “cozy” instead of negatively as “cramped.”

- Criteria : standards by which something is judged. Reviewers generally make their evaluation criteria clear by listing and explaining what they are basing their review on. Each type of primary source has its set of standards, some or all of which reviewers address.

- Critics : professional reviewer who typically publishes reviews in well-known publications.

- Denotation : the literal or dictionary definition of a word.

- Evaluation : judgment based on analysis.

- Fandom : community of admirers who follow their favorite works and discuss them online as a group.

- Genre : broad category of artistic compositions that share similar characteristics such as form, subject matter, or style. For example, horror, suspense, and drama are common film and literary genres. Hip hop and reggae are common music genres.

- Medium : way in which a work is created or delivered (DVD, streaming, book, vinyl, etc.). Works can appear in more than one medium.

- Mode : sensory method through which a person interacts with a work. Modes include linguistic, visual, audio, spatial, and gestural.

- Primary Sources : in the context of reviewing, the original work or item being reviewed, whether a film, book, performance, business, or product. In the context of research, primary sources are items of firsthand, or original, evidence, such as interviews, court records, diaries, letters, surveys, or photographs.

- Recap : summary of an individual episode of a television series.

- Review : genre that evaluates performances, exhibitions, works of art (books, movies, visual arts), services, and products

- Secondary source: source that contains the analysis or synthesis of someone else, such as opinion pieces, newspaper and magazine articles, and academic journal articles.

- Subgenre : category within a genre. For example, subgenres of drama include various types of drama: courtroom drama, historical/costume drama, and family drama.

Establishing Criteria

All reviewers and readers alike rely on evidence to support an evaluation. When you review a primary source, the evidence you use depends on the subject of your evaluation, your audience, and how your audience will use your evaluation. You will need to determine the criteria on which to base your evaluation. In some cases, you will also need to consider the genre and subgenre of your subject to determine evaluation criteria. In your review, you will need to clarify your evaluation criteria and the way in which specific evidence related to those criteria have led you to your judgment. Table 7.1 illustrates evaluation criteria in four different primary source types.

Even within the same subject, however, evaluation criteria may differ according to the genre and subgenre of the film. Audiences have different expectations for a horror movie than they do for a romantic comedy, for example. For your subject, select the evaluation criteria on the basis of your knowledge of audience expectations. Table 7.2 shows how the evaluation criteria might be different in film reviews of different genres.

Providing Objective Evidence

You will use your established evaluation criteria to gather specific evidence to support your judgment. Remember, too, that criteria are fluid; no reviewer will always use the same criteria for all works, even those in the same genre or subgenre.

Whether or not the criteria are unique to the particular task, a reviewer must look closely at the subject and note specific details from the primary source or sources. If you are evaluating a product, look at the product specifications and evaluate product performance according to them, noting details as evidence. When evaluating a film, select either quotations from the dialogue or detailed, vivid descriptions of scenes. If you are evaluating an employee’s performance, observe the employee performing their job and take notes. These are examples of primary source evidence: raw information you have gathered and will analyze to make a judgment.

Gathering evidence is a process that requires you to look closely at your subject. If you are reviewing a film, you certainly will have to view the film several times, focusing on only one or two elements of the evaluation criteria at a time. If you are evaluating an employee, you might have to observe that employee on several occasions and in a variety of situations to gather enough evidence to complete your evaluation. If you are evaluating a written argument, you might have to reread the text several times and annotate or highlight key evidence. It is better to gather more evidence than you think you need and choose the best examples rather than try to base your evaluation on insufficient or irrelevant evidence.

Modes of Reviews

Not all reviews have to be written; sometimes a video or an audio review can be more engaging than a written review. YouTube has become a popular destination for project reviews, creating minor celebrities out of popular reviewers. However, a written review of a movie might work well because the reviewer can provide just enough information to avoid spoiling the movie, whereas some reviews require more visual interaction to understand.

Take reviewer Doug DeMuro ’s popular YouTube channel. DeMuro reviews cars—everything from sports cars to sedans to vintage cars. Car buyers need to interact with a car to want to buy it, and YouTube provides the next best thing by giving viewers an up-close look.

Technology is another popular type of review on YouTube. YouTube creators like Marques Brownlee discuss rumors about the next Apple iPhone or Samsung Galaxy and provide unboxing videos to record their reactions to the latest phones and laptops. Like DeMuro’s viewers, Brownlee’s audience can get up close to the product. Seeing a phone in Brownlee’s hands helps audience members imagine it in their hands.

On the other hand, reviews don’t always need to be about products you can touch, as Paul Lucas demonstrates on his YouTube channel “Wingin’ It!” Lucas reviews travel experiences (mainly airlines and sometimes trains), evaluating the service of airlines around the world and in various ticket classes.

What do these reviews have in common? First, they are all in the video medium. YouTube ’s medium is video; a podcast’s medium is audio. They also share a mode. YouTube ’s mode is viewing or watching; a podcast’s mode is listening.

These examples all use the genre conventions of reviews discussed in this chapter. The reviewers present a clear evaluation: should you buy this car, phone, or airline ticket? They base their evaluation on evidence that fits a set of evaluation criteria. Doug DeMuro might evaluate a family sedan on the basis of seating, trunk storage, and ride comfort. Marques Brownlee might judge a phone on the basis of battery life, design, and camera quality. Paul Lucas might grade an airline on service, schedules, and seat comfort. While the product or service being reviewed might be different, all three reviewers use similar frameworks.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Authors: Michelle Bachelor Robinson, Maria Jerskey, featuring Toby Fulwiler

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Writing Guide with Handbook

- Publication date: Dec 21, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/1-unit-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/writing-guide/pages/7-3-glance-at-genre-criteria-evidence-evaluation

© Dec 19, 2023 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- Basics for GSIs

- Advancing Your Skills

Writing in a Genre

What kind of paper do you want your students to produce?

It often helps students if you are explicit about the features and rhetorical situation of the papers you want them to write. Remember that in some entering students’ experience, “academic essay” may call to mind a five-paragraph paper giving a summary or opinion. How can you bridge from their previous understanding of formal writing to the understanding they need to develop in your R&C course?

One strategy is to work with the idea of genres. The five-paragraph essay is useful in some contexts, but in college work students are expected to write in multiple academic genres. What are the expectations of the genre you are assigning? You can make your expectations explicit by working through a handout such as the one reproduced below and analyzing an example paper as a class, using the description on the handout. This one emphasizes developing an intellectual voice and framework.

The Genre of Academic Interpretive Argumentation

The task of an academic interpretive argument is to articulate a good case for seeing a text, event, or artifact in a particular way, using the best available evidence and valid reasoning.

Although in the school context it may sometimes seem that students write papers merely for an instructor to grade, really good essays explore an interesting or puzzling question or idea that you can share with others.

Assume that your audience is as well-educated as you are, takes a different perspective, and wants to challenge their understanding by reading your essay. In other words, you are an intelligent person in conversation with another intelligent person through your writing, and the topic interests you both.

Assume that your audience has read the same primary text you have. You do not need to summarize the plot for your reader. Instead, refer to passages briefly — just enough to let the reader know what passage you are analyzing — and focus on what you have to say about the passage.

Interpretive Argumentation

Most really interesting questions or problems are complex and can be approached in a variety of ways. Multiple approaches are possible and yield multiple ways to pose and answer questions. Good interpretive arguments explain why a topic represents a problem from a certain point of view. Identify your argument and from what perspective it makes sense of the problem or question you have chosen.

While there may be many ways to approach a question, all possible answers are not equally good. Some arguments are more plausible and validly presented than others, and some arguments may ignore important, relevant evidence. In developing your question or issue around a topic, you discipline yourself to select the most relevant evidence and to use valid logic, and you anticipate questions your readers might raise and address them as part of your presentation.

Any given essay in this genre does not necessarily reflect its author’s permanent opinion on the topic; the essay is usually more like a snapshot of the author’s best thinking at the time of the writing.

How would you describe the elements of an essay that make sense in your field?

It is also important to show students examples of essays or articles and analyze them closely for the traits you want (and don’t want) to see in students’ work. The full-class discussion and analysis can be followed up with a small-group activity analyzing another short paper, or with a homework assignment in which students compare their own paper or draft with the description of the genre.

Exploring Different Essay Genres: Your In-Depth Guide

.png)

Essays, as a literary form, have deep historical roots. Their origins can be traced back to ancient Greece and Rome, where philosophers and scholars penned texts that shared knowledge, insights, and reflections. Over the centuries, essays have evolved into a versatile medium for expressing ideas, emotions, and information. This evolution has led to the development of various essay genres, each tailored to serve a distinct purpose.

Imagine the ancient Greek philosophers like Plato and Aristotle or the Roman statesman and philosopher Seneca using essays to convey their profound thoughts and philosophical musings. Fast forward to modern times, and we see how essays have adapted to our changing world, becoming a cornerstone of communication and education.

Exploring Different Essay Genres: Short Description

In this article, we'll unravel various essay genres, from narrative to expository, argumentative to descriptive, and many more. We'll break them down by explaining what they are and what makes them unique. You'll find examples that show how these essays work in the real world, along with tips to help you become a pro at writing them. Whether you're a student looking to ace your assignments or a writer seeking to sharpen your skills, we've got you covered with all you need to know about different kinds of essays.

What Type of Essays Are There: The Diversity of Essay Genres

Before we dive into the specifics of different essay genres, let's take a moment to appreciate the rich tapestry of essay writing. Essays come in various forms, each with its own unique characteristics and purposes. From narratives that tell compelling stories to expository essays that explain complex topics and persuasive essays that aim to change minds, custom essay writers of our persuasive essay writing service will explore this diverse landscape to help you understand which genre suits your needs and how to master it.

- Essays Are Like Handy Tools : Think of essays as tools that can help you communicate in many different ways. Just like a Swiss Army knife has different functions, essays can be used for various purposes in writing.

- Choose Your Words Wisely : Different situations need different ways of talking or writing. Essays let you choose the best way to say what you want, whether you're telling a personal story, explaining something, or trying to convince someone of your point of view.

- Boost Your Writing Skills : Learning about different essay types can make you a better writer. It can help you write more effectively, whether you're working on a school assignment, a blog post, or an important letter.

- Essays Have Made History : Throughout history, essays have been a big deal. They've shaped our culture and society. From old classics to modern essays, they've had a big impact.

- Stand Out in the Online World : In today's digital world, where there's a lot of information and not much time, knowing how to write different types of essays can help you get noticed. Being good at different styles of writing is a useful skill in a world full of information.

The Descriptive Essay

In a descriptive essay, the objective is to immerse the reader in the experience of what you're describing. For instance, when contemplating how to write an article review , utilizing descriptive writing allows you to vividly depict the subject matter, creating a rich and immersive portrayal through words.

A. Definition and Characteristics

- What is it? A descriptive essay is like a word painting. It uses lots of details and vivid words to create a picture in the reader's mind.

- Characteristics:

- Lots of sensory details: Descriptive essays make you feel like you're right there by using words that describe what you can see, hear, smell, taste, or touch.

- Vivid language and imagery: They use colorful words and phrases to make the reader really imagine what's being described.

B. Examples and Use Cases

- When do we use it? Imagine describing your favorite place, like a cozy cabin in the woods, or a memorable experience, like your first day at school. These are common subjects for descriptive essays.

- Describing a beautiful sunset over the ocean.

- Painting a picture of your childhood home, room by room.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Descriptive Essay

- Show, Don't Tell: Instead of just saying something is 'nice,' show why it's nice by describing the details that make it special.

- Organize Details: Arrange your descriptions in an order that makes sense. Start with the big picture and then focus on the smaller details.

Engage the Senses: Make sure your writing appeals to all the senses. Describe how things look, sound, smell, taste, and feel to create a complete picture.

Ready to Craft a One-of-a-Kind Essay?

Order now for a tailored essay - Our expert wordsmiths are armed with creativity, precision, and a sprinkle of genius!

The Expository Essay

In an expository essay, your job is to be a great teacher. You're presenting information in a way that's easy to understand and follow so the reader can learn something new or gain a deeper insight into a subject.

- What is it? An expository essay is like a friendly explainer. It provides clear and factual information about a topic, idea, or concept.

- It's all about facts: Expository essays rely on solid evidence, data, and information to explain things.

- Clear and organized: They follow a logical structure with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion.

- When do we use it? Think of when you need to explain something, like how photosynthesis works, how to bake a cake, or the causes of climate change. These topics are perfect for expository essays.

- Explaining the steps to solve a math problem.

- Describing the history and significance of a famous landmark.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Expository Essay

- Clear Thesis Statement: Start with a strong and clear thesis statement that tells the reader what your essay is all about.

- Organized Structure: Divide your essay into clear sections or paragraphs that each cover a specific aspect of the topic.

- Supporting Evidence and Citations: Use reliable sources and provide evidence like facts, statistics, or examples to back up your explanations.

The Argumentative Essay

In this example of essay type, your goal is to persuade the reader to agree with your point of view or take action on a specific issue. It's like being a lawyer presenting your case in court, but instead of a judge and jury, you have your readers.

- What is it? An argumentative essay is like a debate on paper. It's all about taking a clear stance on a controversial topic and providing strong reasons and evidence to support your point of view.

- A strong thesis statement: Argumentative essays start with a clear and assertive thesis statement that tells the reader your position.

- Counter Arguments: They also consider opposing viewpoints and then refute them with evidence.

- When do we use it? Imagine you want to convince someone that your favorite book is the best ever or that recycling should be mandatory. These are situations where you'd use an argumentative essay.

- Arguing for or against a particular law or policy.

- Debating the pros and cons of a controversial technology like artificial intelligence.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Argumentative Essay

- Strong Thesis: Make sure your thesis is clear, specific, and debatable.

- Evidence and Logic: Back up your arguments with solid evidence and use logical reasoning.

- Address Counterarguments: Acknowledge opposing views and explain why your perspective is more valid.

The Narrative Essay

In a narrative essay, you assume the role of the storyteller, guiding your readers through your personal experiences. This style is particularly apt when contemplating how to write a college admission essay . It offers you the opportunity to share a piece of your life story and forge a connection with your audience through the captivating art of storytelling.

- What is it? A narrative essay is like sharing a personal story. It's all about recounting an experience, event, or moment in your life in a way that engages the reader.

- It's personal: Narrative essays often use 'I' because they're about your own experiences.

- Storytelling: They have a beginning, middle, and end, just like a good story.

- When do we use it? Think of moments in your life that you want to share, like a funny incident, a life-changing event, or a memorable trip. These are perfect for narrative essays.

- Sharing a personal childhood memory that taught you a valuable lesson.

- Describing an adventure-filled vacation that had a big impact on your life.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Narrative Essay

- Engaging Start: Begin with a captivating hook to draw the reader into your story.

- Show, Don't Tell: Use descriptive language to help the reader visualize the events and feel the emotions.

- Reflect and Conclude: Wrap up your narrative by reflecting on the experience and why it was meaningful or significant.

The Contrast Essay

In this type of essays, your goal is to help the reader understand how two or more things are distinct from each other. It's a way to bring out the unique qualities of each subject and make comparisons that highlight their differences.

- What is it? A contrast essay is like a spotlight on differences. It's all about showing how two or more things are different from each other.

- Comparison: Contrast essays focus on comparing two or more subjects and highlighting their dissimilarities.

- Clear Structure: They often use a structured format, discussing one point of difference at a time.

- When do we use it? Imagine you want to explain how two cars you're considering for purchase are different, or you're comparing two historical figures for a school project. These are situations where you'd use a contrast essay.

- Contrasting the pros and cons of two different smartphone models.

- Comparing the lifestyles and philosophies of two famous authors.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Contrast Essay

- Choose Clear Criteria: Decide on the specific criteria or aspects you'll use to compare the subjects.

- Organized Structure: Use a clear and organized structure, such as a point-by-point comparison or a subject-by-subject approach.

- Highlight Key Differences: Ensure you emphasize the most significant differences between the subjects.

The Definition Essay

In a definition essay, you take on the role of a language detective, seeking to unravel the intricate layers of meaning behind a term. It's a chance to explore the nuances and variations in how people understand and use a specific word or concept.

- What is it? A definition essay is like a word detective. It's all about explaining the meaning of a specific term or concept, often one that's abstract or open to interpretation.

- Clarity: Definition essays aim to provide a clear, precise, and comprehensive definition of the chosen term.

- Exploration: They explore the various facets, interpretations, and nuances of the term.

- When do we use it? Think of terms or concepts that people might misunderstand or have different opinions about, like 'freedom,' 'happiness,' or 'justice.' These are great candidates for definition essays.

- Defining the concept of 'success' and what it means to different people.

- Exploring the various definitions and interpretations of 'love' in different cultures and contexts.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Definition Essay

- Choose a Complex Term: Select a term that has multiple meanings or interpretations.

- Research and Explore: Investigate the term thoroughly, including its history, etymology, and various definitions.

- Provide Examples: Use real-life examples, anecdotes, or scenarios to illustrate your definition.

The Persuasive Essay

In a persuasive essay, your goal is to be a persuasive speaker through your writing. You're trying to win over your readers and get them to agree with your perspective or take action on a particular issue. It's all about presenting a compelling argument that makes people see things from your point of view.

- What is it? A persuasive essay is like a friendly argument with facts. It's all about convincing the reader to agree with your point of view on a particular topic or issue.

- Strong Opinion: Persuasive essays start with a clear and strong opinion or position.

- Evidence-Based: They rely on solid evidence, logic, and reasoning to support their argument.

- When do we use it? Think of situations where you want to persuade someone to see things your way, like convincing your parents to extend your curfew or advocating for a cause you believe in. These are scenarios where you'd use a persuasive essay.

- Arguing for stricter environmental regulations to combat climate change.

- Convincing readers to support a specific charity or volunteer for a cause.

C. Tips for Writing an Effective Persuasive Essay

- Clear Thesis Statement: Start with a strong thesis statement that clearly states your opinion.

- Evidence and Logic: Back up your arguments with solid evidence, statistics, and logical reasoning.

- Address Counterarguments: Acknowledge and respond to opposing views to strengthen your argument.

How to Identify the Genre of an Essay

Identifying the genre of an essay is like deciphering the code that unlocks its purpose and style. This skill is crucial for both readers and writers because it helps set expectations and allows for a deeper understanding of the text. Here are some insightful tips on how to identify the genre of an essay from our thesis writing help :

1. Analyze the Introduction:

- The introductory paragraph often holds valuable clues. Look for keywords, phrases, or hints that reveal the writer's intention. For example, a narrative essay might start with a personal anecdote, while a synthesis essay may introduce a topic with a concise explanation.

2. Examine the Tone and Language

- The tone and language used in the essay provide significant clues. A persuasive essay may employ passionate and convincing language, whereas an informative essay tends to maintain a neutral and factual tone.

3. Check the Structure

- Different genres of essays follow specific structures. Narrative essays typically have a chronological structure, while argumentative essays present a clear thesis and structured arguments. Understanding the essay's organizational pattern can help pinpoint its genre.

4. Consider the Content

- The subject matter and content of the essay can also indicate its genre. Essays discussing personal experiences or emotions often lean towards the narrative or descriptive genre, while those presenting facts and analysis typically fall into the expository or argumentative category.

5. Identify the Author's Intent

- Sometimes, the author's intent becomes apparent when considering why they wrote the essay. Are they trying to entertain, inform, persuade, or reflect on a personal experience? Understanding the author's purpose can be a powerful tool for genre identification.

6. Recognize Genre Blending

- Keep in mind that some essays may blend multiple genres. For instance, a personal essay might incorporate elements of both narrative and descriptive writing. In such cases, it's essential to identify the dominant genre and any secondary influences.

7. Seek Contextual Clues

- Context can provide valuable insights. Consider where you encountered the essay — in a literature class, a news outlet, or a personal blog. The context can often hint at the intended genre.

8. Ask Questions

- Don't hesitate to ask questions as you read. What is the author trying to achieve? Is the focus on storytelling, providing information, arguing a point, or something else? Questions like these can guide you toward identifying the genre.

Final Thoughts

In the tapestry of writing, we've unraveled the threads of diverse essay styles, from the vivid descriptions of the descriptive essay to the informative clarity of expository pieces. Each genre brings its unique charm to the literary world. Embrace this versatility in your own writing journey, adapting your style to engage, inform, and persuade. In the realm of essays, your creative potential has boundless opportunities. Should you ever require help with the request, ' write papers for me ,' you can be confident that our professional writers will deliver an exceptional paper tailored to your needs!

Table of Contents

Ai, ethics & human agency, collaboration, information literacy, writing process.

- © 2023 by Joseph M. Moxley - University of South Florida

Genre may reference a type of writing, art, or musical composition; socially-agreed upon expectations about how writers and speakers should respond to particular rhetorical situations; the cultural values; the epistemological assumptions about what constitutes a knowledge claim or authoritative research method; the discourse conventions of a particular discourse community . This article reviews research and theory on 6 different definitions of genre, explains how to engage in genre analysis, and explores when during the writing process authors should consider genre conventions. Develop your genre knowledge so you can discern which genres are appropriate to use—and when you need to remix genres to ensure your communications are both clear and persuasive.

Genre Definition

G enre may refer to

- by the aim of discourse

- by discourse conventions

- by discourse communities

- by a type of technology

- a social construct

- the situated actions of writers and readers

- the situated practices and epistemological assumptions of discourse communities

- a form of literacy .

Related Concepts: Deductive Order, Deductive Reasoning, Deductive Writing ; Interpretation ; Literacy ; Mode of Discourse ; Organizational Schema; Rhetorical Analysis ; Rhetorical Reasoning ; Voice ; Tone ; Persona

Genre Knowledge – What You Need to Know about Genre

Genre plays a foundational role in meaning-making activities, including interpretation , reading , writing, and speaking.

In order to communicate with clarity , writers and speakers need to understand the expectations of their audiences regarding the appropriate content, style, design, citation style, and medium. Genres facilitate communication between writers and readers, authors and audiences, and writers/speakers and readers/listeners. Genre and genre knowledge increase the likelihood of clarity in communications .

Writers use their knowledge of genre to jumpstart composing: a genre presumes a formula for how to organize a document, how to develop and present a research question , how to substantiate claims–and more. For writers, genres are an efficient way to respond to recurring situations . Rather than reinvent the wheel every time, writers save time by considering how others have responded in the same or a similar situation . Genres are like big Lego chunks that can be re-used to start a new Lego creation that is similar to past Lego creations you’ve created.

In turn, readers use genres to more quickly scan information . Because they know the formula, because they share with the author as members of a discourse community a common language, common topoi , archive , canonical texts , and expectations about what to say and how to say it in, they can skip through a document and grab the highlights.

Six Definitions of Genre

1. genre refers to a naming and categorization scheme for sorting types of writing.

“… [L]et me define “genres” as types of writing produced every day in our culture, types of writing that make possible certain kinds of learning and social interaction.” (Cooper 1999, p. 25)

G enre refers to types of writing, art, and musical compositions. For instance

- alphabetical texts may be categorized as Expository Writing, Descriptive Writing, Persuasive Writing, or Narrative Writing .

- movies may be categorized as Action & Adventure, Children & Family Movies, Comedies, Documentaries, Dramas.

- music may be categorized as Artist, Album, Country, New Age, Jazz, and so on.

There are many different ways to define and sort genres. For instance, genres may defined based on their content, organization, and style. Or, genres may be defined and categorized based on

- Examples: Drama, Fable, Fairy Tale, etc.

- Move 1 Establish a territory

- Move 2 Establish a niche

- Move 3 Occupy the niche (Swales and Feak 2004)

- A research article written for a scientific audience most likely uses some for of an “IMRAC structure”–i.e., an introduction, methods, results, and conclusion

- An article in the sciences and social sciences would use APA style for citations

- by the type of technology used by the sender and the receiver of the information.

2. Genre is a Social Construct

“Genres are conventions, and that means they are social – socially defined and socially learned.” (Bomer 1995:112) “… [A] genre is a socially standard strategy, embodied in a typical form of discourse, that has evolved for responding to a recurring type of rhetorical situation.” (Coe and Freedman 1998, p. 137)

Genre is more than a way to sort types of texts by discourse aim or some other classification scheme: Genres are social, cultural, rhetorical constructs. For example,

- writers draw on their expectations about what they believe their readers will know about a genre–how it’s structured ( what it’s formula is! ) and when it’s socially useful.

- readers draw on their past experiences as readers and as members of particular discourse communities. They hold expectations about the appropriate use of particular textual patterns in specific situations.

Or, consider this example: in the social situation of seeking a job, an applicant knows from the archive , the culture, the conversations about job seeking , that they are expected to create a letter of application and a résumé . More than that, they know the point of view they are to take as well as the tone –and more.

Writers and readers develop textual expectations tacitly — by reading and speaking with others — and formally: by studying genres in school. Students are inculcated in textual practices of particular disciplines (e.g., engineering or biology) as part of their academic and professional training.

3. Genres Reflect the Situated Actions of Writers and Readers

“a rhetorically sound definition of genre must be centered not on the substance or the form of discourse but on the action it is used to accomplish” (Miller 1984, p. 151)

Carolyn Miller (1984) extends this social view of genre in her article Genre as Social Action by operationalizing genre from a rhetorical perspective. Miller asserts genres are the embodiment of situated actions. In her rhetorical model of genre, Miller theorizes

- writers enter a rhetorical situation guided by aims (e.g., to persuade users to support a proposal ). The writer assesses the rhetorical situation (e.g., considers audience , purpose , voice , style ) to more fully understand the situation and the motives of stakeholders.

- For instance, a researcher could dip into a research study seeking empirical support for a claim . A graphic designer could open a magazine looking for layout ideas.

4. Genres Embody the Situated Practices and Values of Discourse Communities

“Genre not only allows the scholar to report her research, but its conventions and constraints also give structure to the actual investigations she is reporting” (Joliffe 1996, p. 283).

The textual practices of discourse communities reflect the epistemological assumptions of practitioners regarding what constitutes an appropriate rhetorical stance , research method , or knowledge claim . For instance, a scientist doesn’t insert their subjective opinions into the methods section of a lab report because they understand their audience expect them to follow empirical methods and an academic writing prose style

Academic documents, business documents, legal briefs, medical records—these sorts of texts are grounded in the situated practices of members of particular discourse communities . Practitioners — e.g., scientists in a research lab, accountants in an accountancy firm, or engineers in an engineering firm— share assumptions, conventions, and values about how documents should be researched, written, and shared. Discourse communities develop unique ways of communicating with one another. Their daily work, their situated practices, reflect their assumptions about what constitutes knowledge , appropriate research methods, or authoritative sources . Genres reflect the values of communities . They provide a roadmap to rhetors for how to engage with community members in expected ways. (For more on this, see Research ).

5. Genre Knowledge Constitutes a Form of Literacy

Genres are created in the forge of recurring rhetorical situations . Particular exigencies call for particular genres . Applying for a job? Well, then, a résumé and cover letter are called for. Trying to report on an experiment in organic chemistry? Well, then a lab report is due. Thus, being able to recognize which genre is called for by a particular exigency, a particular call to write , is a form of literacy : If you’re unfamiliar with a genre and your reader’s expectations for that genre, then you may as well be from mars.

Genre Analysis – How to Engage in Genre Analysis

When we enter a rhetorical situation , guided by a sense of purpose like an explorer clutching a compass, we invariably compare the present situation to past situations. We reflect on whether we have read the work of other writers who have also addressed the same or somewhat equivalent rhetorical situation , the topic, we’re facing. If you have a proposal due, for instance, it helps to look at some samples of past proposals–particularly if you can access proposals funded by the organization from whom you are seeking support.

For genre theorists, these are acts of typification –a moment where we typify a situation: “What recurs is not a material situation (a real, objective, factual event) but our construal of a type” (Miller 157).

In other words, genres are conceptual tools, ways we relate situated actions to recurring rhetorical situations. When first entering a situation, we assess whether this is a recurring rhetorical situation and whether past responses will work equally well for this new situation—or if we’ll need to tweak our response, our text, a bit. For instance, if applying for a job, you might look at previous drafts of job application letters

Genres are like prefabricated Lego pieces that we can use to jumpstart a new Lego masterpiece.

We abbreviate the experiences of our lives by creating idealized versions–i.e., metatexts that capture the gist of those experiences. Or, we access the archive , or our memory of the archive, and seek exemplars — canonical texts , the works of others who addressed similar exigencies , similar rhetorical situations.

To make this less abstract, let’s consider what might go through the mind of a writer who wants to write a New Year’s party invitation. If the writer were an American, they might reflect on the ritual ball drop in Times Square in New York City. They might recall past texts associated with New Year’s celebrations (party invitations, menus, greeting cards, party hats, songs, and resolutions) as well as rituals (fireworks, champagne, or a New Year’s kiss). They might even conduct an internet search for New Year’s Eve party invitations or download a party template from Google Docs or Microsoft Word. Over time, that writer’s sense of the ideal New Year’s party invitation becomes typified —a condensation of the texts and rituals and stories.

Because we tend to have unique experiences and because we have different personalities, motives, and aims , our sense of an ideal New Year’s Eve invitation might be somewhat different from those of our friends and family—or even the broader society. Rather than assuming it’s a good time to go out and party and dance, you may think it’s a good time to stay home and meditate. After all, as writers, we experience events, texts and rituals subjectively and uniquely. Thus, we don’t all have the same ideas about what should happen at a New Year’s party or even what the best party invite should look like. Still, when we sit down to write a party invitation for New Year’s Eve, this is a reoccurring situation for us, and we cannot help but be influenced by all of the past invitations we’ve received, what our friends and loved ones have recommended, and what we see online for party invite templates (if we engage in strategic searching).

Sample Genre Analysis

Below are some sample questions and perspectives you may consider when engaging in Genre Analysis.

1. When During Composing Should I Engage in Genre Analysis?

Early in the writing process — during prewriting — you are wise to identify the genre your audience expects you to follow. Then, engage in strategic searching to identify exemplars and canonical texts that typify the genre.

Next, you might begin your first draft by outlining the sections of discourse associated with the genre you’re writing in. For example, if you are writing an Aristotelian argument for a school paper, you might jumpstart your first draft by listing the rhetorical moves associated with Aristotelian argument as your subject headings:

- Introduce the Topic

- Introduce Claims

- Appeal to Ethos & Persona to Establish an Appropriate Tone

- Appeal to Emotions

- Appeal to Logic

- Present Counterarguments

- Search for a Compromise and Call for a Higher Interest

- Speculate About Implications in Conclusions