- Social Media

The Importance of Maintaining Native Language

The United States is often proudly referred to as the “melting pot.” Cultural diversity has become a part of our country’s identity. However, as American linguist, Lilly Wong Fillmore, pointed out in her language loss study, minority languages remain surprisingly unsupported in our education system (1991, p. 342). Although her research was conducted more than twenty years ago, this fact still rings true. Many non-minority Americans are not aware of the native language loss that has become prevalent in children of immigrant parents. While parents can maintain native language, children educated in U.S. schools quickly lose touch with their language heritage. This phenomenon, called subtractive bilingualism, was first discovered by psychologist Wallace Lambert, in his study of the language acquisition of French-Canadian children. The term refers to the fact that learning a second language directly affects primary language, causing loss of native language fluency (Fillmore, 1991, p. 323). This kind of language erosion has been integral to the narrative of this country for some time. Many non-minority Americans can trace their family tree back to a time when their ancestors lost fluency in a language that was not English. Today, due to the great emphasis on assimilation into the United States’ English-speaking culture, children of various minorities are not only losing fluency, but also their ability to speak in their native language, at all (Fillmore, 1991, p. 324).

The misconceptions surrounding bilingual education has done much to increase the educational system’s negative outlook on minority languages. In Lynn Malarz’s bilingual curriculum handbook, she states that “the main purpose of the bilingual program is to teach English as soon as possible and integrate the children into the mainstream of education” (1998). This handbook, although written in 1998, still gives valuable insight into how the goals of bilingual education were viewed. Since English has become a global language, this focus of bilingual education, which leads immigrant children to a future of English monolingualism, seems valid to many educators and policymakers. Why support minority languages in a country where English is the language of the prosperous? Shouldn’t we assimilate children to English as soon as possible, so that they can succeed in the mainstream, English-speaking culture? This leads us to consider an essential question: does language loss matter? Through the research of many linguists, psychologists, and language educators, it has been shown that the effect of native language loss reaches far. It impacts familial and social relationships, personal identity, the socio-economic world, as well as cognitive abilities and academic success. This paper aims to examine the various benefits of maintaining one’s native language, and through this examination, reveal the negative effects of language loss.

Familial Implications

The impact of native language loss in the familial sphere spans parent-child and grandparent-grandchild relationships, as well as cultural respects. Psychologists Boutakidis, Chao, and Rodríguez, (2011) conducted a study of Chinese and Korean immigrant families to see how the relationships between the 9th-grade adolescences and their parents were impacted by native language loss. They found that, because the adolescents had limited understanding and communicative abilities in the parental language, there were key cultural values that could not be understood (Boutakidis et al., 2011, p. 129). They also discovered there was a direct correlation between respect for parents and native language fluency. For example, honorific titles, a central component of respect unique to Chinese and Korean culture, have no English alternatives (p.129). They sum up their research pertaining to this idea by stating that “children’s fluency in the parental heritage language is integral to fully understanding and comprehending the parental culture” (Boutakidis et al., 2011, p. 129). Not only is language integral to maintaining parental respect, but also cultural identity.

In her research regarding parental perceptions of maintaining native language, Ruth Lingxin Yan (2003) found that immigrant parents not only agree on the importance of maintaining native language, but have similar reasoning for their views. She discovered that maintaining native language was important to parents, because of its impact on heritage culture, religion, moral values, community connections, and broader career opportunities.

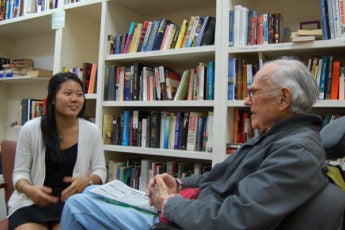

Melec Rodriguez, whose parents immigrated to the United States before he was born, finds that his native language loss directly impacts his relationship with his grandparents. Rodriguez experienced his language loss in high school. He stated that due to his changing social group and the fact that he began interacting with his family less, he found himself forgetting “uncommon words in the language.” His “struggle to process information” causes him to “take a moment” to “form sentences in [his] mind during conversations” (M. Rodriguez, personal communication, Nov. 3, 2019). Of his interactions with his grandparents, who have a limited understanding of English, he stated:

“I find very often that I simply cannot think of a way to reply while conveying genuine emotion, and I know they feel I am detached at times because of that. I also struggle to tell exciting stories about my experiences and find it hard to create meaningful conversations with family” (M. Rodriguez, personal communication, Nov. 3, 2019).

Rodriguez’s native language loss creates a distinct communicative barrier between him and his grandparents, causing him difficulty in genuine connection building. Although this is a relatively obvious implication of native language loss, it is nonetheless a concerning effect.

Personal Implications

Native language, as an integral part of the familial sphere, also has strong connections on a personal level. The degree of proficiency in one’s heritage language is intrinsically connected to self-identity. The Intercultural Development Research Association noted this connection, stating that “the child’s first language is critical to his or her identity. Maintaining this language helps the child value his or her culture and heritage, which contributes to a positive self-concept. (“Why Is It Important to Maintain the Native Language?” n.d.). Grace Cho, professor and researcher at California State University, concluded “that [heritage language] development can be an important part of identity formation and can help one retain a strong sense of identity to one's own ethnic group” (Cho, 2000, p. 369). In her research paper, she discussed the “identity crisis” many Korean American students face, due to the lack of proficiency they have in their heritage language (p. 374). Cho found that students with higher levels of fluency could engage in key aspects of their cultural community, which contributed greatly to overcoming identity crises and establishing their sense of self (p. 375).

Social Implications

Native language loss’ connections to family relationships and personal identity broaden to the social sphere, as well. Not only can native language loss benefit social interactions and one’s sense of cultural community, it has large-scale socioeconomic implication. In Cho’s study (2000) she found that college-aged participants with Korean ancestry were faced with many social challenges due to limited fluency in Korean. Participants labeled with poor proficiency remarked on the embarrassment they endured, leading them to withdraw from social situations that involved their own ethnic group (p. 376). These students thus felt isolated and excluded from the heritage culture their parents actively participated in. Native language loss also caused students to face rejection from their own ethnic communities, resulting in conflicts and frustration (p. 377). Participants that did not complain of any conflict actively avoided their Korean community due to their lack of proficiency (p. 378). Participants who were labeled as highly proficient in Korean told of the benefits this had, allowing them to “participate freely in cultural events or activities” (p. 374). Students who were able to maintain their native language were able to facilitate meaningful and beneficial interactions within their cultural community.

Melec Rodriguez made similar comments in his experience as a Spanish and English- speaking individual. Although his native language loss has negatively affected his familial relationships, he has found that, in the past, his Spanish fluency “allowed for a greater social network in [his] local community (school, church, events) as [he] was able to more easily understand and converse with others” (M. Rodriguez, personal communication, Nov. 3, 2019). As this research suggests, native language fluency has a considerate influence on social interactions. Essentially, a lack of fluency in one’s native language creates a social barrier; confident proficiency increases social benefits and allows genuine connections to form in one’s cultural community.

Benefits to the Economy

Maintaining native language not only benefits personal social spheres, but also personal career opportunities, and thereby the economy at large. Peeter Mehisto and David Marsh (2011), educators central to the Content and Language Integrated Learning educational approach, conducted research into the economic implications of bilingualism. Central to their discussion was the idea that “monolingualism acts as a barrier to trade and communication” (p. 26). Thus, bilingualism holds an intrinsic communicative value that benefits the economy. Although they discovered that the profits of bilingualism can change depending on the region, they referred to the Fradd/Boswell 1999 report, that showed Spanish and English-speaking Hispanics living in the United States earned more than Hispanics who had lost their Spanish fluency (Mehisto & Marsh, 2011, p. 22). Mehisto and Marsh also found that bilingualism makes many contributions to economic growth, specifically “education, government, [and] culture…” (p. 25). Bilingualism is valuable in a society in which numerous services are demanded by speakers of non-English languages. The United States is a prime example of a country in which this is the case.

Increased Job Opportunites

Melec Rodriguez, although he has experienced native language loss, explained that he experienced increased job opportunities due to his Spanish language background. He stated:

“Living in south Texas, it is very common for people to struggle with either English or Spanish, or even be completely unable to speak one of the languages. There are many restaurants or businesses which practice primarily in one language or the other. Being bilingual greatly increased the opportunity to get a job at many locations and could make or break being considered as a candidate” (M. Rodriguez, personal communication, Nov. 3, 2019).

Rodriguez went on to explain that if he were more confident in his native language, he would have been able to gain even more job opportunities. However, as his language loss has increased through the years, Spanish has become harder to utilize in work environments. Thus, maintaining one’s native language while assimilating to English is incredibly valuable, not only to the economy but also to one’s own occupational potential.

Cognitive and Academic Implications

Those who are losing native language fluency due to English assimilation are missing out on the cognitive and academic benefits of bilingualism. The Interculteral Development Research Association addresses an important issue in relation to immigrant children and academic success. When immigrant children begin at U. S. schools, most of their education is conducted in English. However, since these students are not yet fluent in English, they must switch to a language in which they function “at an intellectual level below their age” (“Why Is It Important to Maintain the Native Language?” n.d.). Thus, it is important that educational systems understand the importance of maintaining native language. It is also important for them to understand the misconceptions this situation poses for the academic assessments of such students.

In Enedina Garcia-Vazquez and her colleague's (1997) study of language proficiency’s connection to academic success, evidence was found that contradicted previous ideas about the correlation. The previous understanding of bilingualism in children was that it caused “mental confusion,” however, this was accounted for by the problematic methodologies used (Garcia- Vazquez, 1997, p. 395). In fact, Garcia-Vazquez et al. discuss how bilingualism increases “reasoning abilities” which influence “nonverbal problem-solving skills, divergent thinking skills, and field independence” (p. 396). Their study of English and Spanish speaking students revealed that proficiency in both languages leads to better scores on standardized tests (p. 404). The study agreed with previous research that showed bilingual children to exceed their monolingual peers when it came to situations involving “high level…cognitive control” (p. 396). Bilingualism thus proves to have a distinct influence on cognitive abilities.

Mehisto and Marsh (2011) discuss similar implications, citing research that reveals neurological differences in bilingual versus monolingual brains. This research indicates that the “corpus callosum in the brain of bilingual individuals is larger in area than is the case for monolinguals” (p. 30). This proves to be an important difference that reveals the bilingual individual’s superiority in many cognitive functions. When it comes to cognitive ability, Mehisto and Marsh discuss how bilinguals are able to draw on both languages, and thus “bring extra cognitive capacity” to problem-solving. Not only can bilingualism increase cognitive abilities, but it is also revealed to increase the “cognitive load” that they are able to manage at once (p.30). Many of the academic benefits of bilingualism focus on reading and writing skills. Garcia-Vazquez’s study focuses on how students who were fluent in both Spanish and English had superior verbal skills in both writing and reading, as well as oral communication (p. 404). However, research indicates that benefits are not confined to this area of academics. Due to increased cognition and problem-solving skills, research indicates that bilingual individuals who are fluent in both languages achieved better in mathematics than monolinguals, as well as less proficient bilinguals (Clarkson, 1992). Philip Clarkson, a mathematics education scholar, conducted one of many studies with students in Papua New Guinea. One key factor that Clarkson discovered was the importance of fluency level (p. 419). For example, if a student had experienced language loss in one of their languages, this loss directly impacted their mathematical competence. Not only does Clarkson’s research dissuade the preconceived notions that bilingualism gets in the way of mathematical learning, it actually proves to contribute “a clear advantage” for fluent bilingual students (p. 419). Clarkson goes on to suggest that this research disproves “the simplistic argument that has held sway for so long for not using languages other than English in Papua New Guinea schools” (p. 420). He thus implies the importance of maintaining the native language of the students in Papua New Guinea since this bilingual fluency directly impacts mathematical competency.

Both Garcia-Vazquez et al. and Mehisto and Marsh reveal how proficiency in two languages directly benefits a brain’s functions. Their research thus illustrates how maintaining one’s native language will lead to cognitive and academic benefits. Clarkson expands on the range of academic benefits a bilingual student might expect to have. It is important to note that, as Clarkson’s research showed, the fluency of a bilingual student has much influence on their mathematical abilities. Thus, maintaining a solid fluency in one’s native language is an important aspect of mathematical success.

Suggested Educational Approach

The acculturation that occurs when immigrants move to the United States is the main force causing language loss. Because of the misconceptions of bilingual education, this language loss is not fully counteracted. Policymakers and educators have long held the belief that bilingual education is essentially a “cop-out” for immigrants who do not wish to assimilate to the United States’ English-speaking culture (Fillmore, 1991, p. 325). However, bilingual education is central to the maintenance of native language. Due to the misconceptions and varied views on this controversial subject, there are two extremes of bilingual education in the United States. In Malarz’s (1998) curriculum handbook, she explains the two different viewpoints of these approaches. The first pedological style’s goal is to fully assimilate language-minority students to English as quickly and directly as possible. Its mindset is based on the idea that English is the language of the successful, and that by teaching this language as early as possible, language- minority children will have the best chance of prospering in mainstream society. However, this mindset is ignorant of the concept of subtractive bilingualism, and thus is not aware that its approach is causing native language loss. The second approach Malarz discusses is the bilingual education that places primary importance on retaining the student’s heritage culture, and thereby, their native language. This approach faces much criticism ,since it seems to lack the appropriate focus of a country that revolves around its English-speaking culture. Neither of these approaches poses a suitable solution to the issue at hand. Maintaining native language, as we have discussed, is extremely valuable. However, learning English is also an important goal for the future of language-minority students. Thus, the most appropriate bilingual educational approach is one of careful balance. Native language, although important, should not be the goal, just as English assimilation should not be the central focus. Instead, the goal of bilingual education should be to combine the two former goals and consider them as mutually inclusive. This kind of balanced education is certainly not mainstream, although clearly needed. In Yan’s research regarding parental perceptions of maintaining native language, she found that parents sought after “bilingual schools or those that provided instruction with extra heritage language teaching” (2003, p. 99). Parents of language-minority students recognize the importance of this kind of education and educators and policymakers need to, as well.

The ramifications of native language loss should not be disregarded. Unless bilingual children are actively encouraged and assisted by parents and teachers to maintain their native language, these children will lose their bilingualism. They will not only lose their native fluency and the related benefits, but they will also experience the drawbacks associated with language loss. As the research presented in this article illustrates, there are several specific advantages to maintaining native language. The familial implications reveal that native language loss is detrimental to close relationships with parents and grandparents. Maintaining native language allows for more meaningful communication that can facilitate respect for these relationships as well as heritage culture as a whole. Native language maintenance is also an important factor in the retainment of personal identity. In regard to the social sphere, isolation and a feeling of rejection can occur if native language is not maintained. Additionally, it was found that maintaining native language allows for greater involvement in one’s cultural community. Other social factors included the benefits of bilingualism to the economy as well as the greater scope of job opportunities for bilingual individuals. A variety of studies concluded that there are many cognitive and academic benefits of retaining bilingualism. Due to the many effects of native language loss and the variety of benefits caused by maintaining native language, it can be determined that native language retainment is incredibly important.

Boutakidis, I. P., Chao, R. K., & Rodríguez, J. L. (2011). The role of adolescent’s native language fluency on quality of communication and respect for parents in Chinese and Korean immigrant families. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 2(2), 128–139. doi: 10.1037/a0023606.

Cho, G. (2000). The role of heritage language in social interactions and relationships: Reflections from a language minority group. Bilingual Research Journal, 24(4), 369-384. doi:10.1080/15235882.2000.10162773

Clarkson, P. C. (1992). Language and mathematics: A comparison of bilingual and monolingual students of mathematics. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 23(4), 417.

Fillmore, L. W. (1991). When learning a second language means losing the first. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 6(3), 323–346. doi: 10.1016/s0885-2006(05)80059-6

Garcia-Vazquez, E., Vazquez, L. A., Lopez, I. C., & Ward, W. (1997). Language proficiency and academic success: Relationships between proficiency in two languages and achievement among Mexican American students. Bilingual Research Journal, 21(4), 395.

Malarz, L. (1998). Bilingual Education: Effective Programming for Language-Minority Students. Retrieved November 10, 2019, from http://www.ascd.org/publications/curriculum_handbook/413/chapters/Biling... n@_Effective_Programming_for_Language-Minority_Students.aspx .

Mehisto, P., & Marsh, D. (2011). Approaching the economic, cognitive and health benefits of bilingualism: Fuel for CLIL. Linguistic Insights - Studies in Language and Communication, 108, 21-47.

Rodriguez, M. (2019, November 3). Personal interview.

Why is it Important to Maintain the Native Language? (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.idra.org/resource-center/why-is-it-important-to-maintain-the... language/.

Yan, R. (2003). Parental Perceptions on Maintaining Heritage Languages of CLD Students.

Bilingual Review / La Revista Bilingüe, 27(2), 99-113. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/25745785

Search form

- Find Stories

- For Journalists

Image credit: Getty Images

The power of language: How words shape people, culture

Speaking, writing and reading are integral to everyday life, where language is the primary tool for expression and communication. Studying how people use language – what words and phrases they unconsciously choose and combine – can help us better understand ourselves and why we behave the way we do.

Linguistics scholars seek to determine what is unique and universal about the language we use, how it is acquired and the ways it changes over time. They consider language as a cultural, social and psychological phenomenon.

“Understanding why and how languages differ tells about the range of what is human,” said Dan Jurafsky , the Jackson Eli Reynolds Professor in Humanities and chair of the Department of Linguistics in the School of Humanities and Sciences at Stanford . “Discovering what’s universal about languages can help us understand the core of our humanity.”

The stories below represent some of the ways linguists have investigated many aspects of language, including its semantics and syntax, phonetics and phonology, and its social, psychological and computational aspects.

Understanding stereotypes

Stanford linguists and psychologists study how language is interpreted by people. Even the slightest differences in language use can correspond with biased beliefs of the speakers, according to research.

One study showed that a relatively harmless sentence, such as “girls are as good as boys at math,” can subtly perpetuate sexist stereotypes. Because of the statement’s grammatical structure, it implies that being good at math is more common or natural for boys than girls, the researchers said.

Language can play a big role in how we and others perceive the world, and linguists work to discover what words and phrases can influence us, unknowingly.

How well-meaning statements can spread stereotypes unintentionally

New Stanford research shows that sentences that frame one gender as the standard for the other can unintentionally perpetuate biases.

Algorithms reveal changes in stereotypes

New Stanford research shows that, over the past century, linguistic changes in gender and ethnic stereotypes correlated with major social movements and demographic changes in the U.S. Census data.

Exploring what an interruption is in conversation

Stanford doctoral candidate Katherine Hilton found that people perceive interruptions in conversation differently, and those perceptions differ depending on the listener’s own conversational style as well as gender.

Cops speak less respectfully to black community members

Professors Jennifer Eberhardt and Dan Jurafsky, along with other Stanford researchers, detected racial disparities in police officers’ speech after analyzing more than 100 hours of body camera footage from Oakland Police.

How other languages inform our own

People speak roughly 7,000 languages worldwide. Although there is a lot in common among languages, each one is unique, both in its structure and in the way it reflects the culture of the people who speak it.

Jurafsky said it’s important to study languages other than our own and how they develop over time because it can help scholars understand what lies at the foundation of humans’ unique way of communicating with one another.

“All this research can help us discover what it means to be human,” Jurafsky said.

Stanford PhD student documents indigenous language of Papua New Guinea

Fifth-year PhD student Kate Lindsey recently returned to the United States after a year of documenting an obscure language indigenous to the South Pacific nation.

Students explore Esperanto across Europe

In a research project spanning eight countries, two Stanford students search for Esperanto, a constructed language, against the backdrop of European populism.

Chris Manning: How computers are learning to understand language

A computer scientist discusses the evolution of computational linguistics and where it’s headed next.

Stanford research explores novel perspectives on the evolution of Spanish

Using digital tools and literature to explore the evolution of the Spanish language, Stanford researcher Cuauhtémoc García-García reveals a new historical perspective on linguistic changes in Latin America and Spain.

Language as a lens into behavior

Linguists analyze how certain speech patterns correspond to particular behaviors, including how language can impact people’s buying decisions or influence their social media use.

For example, in one research paper, a group of Stanford researchers examined the differences in how Republicans and Democrats express themselves online to better understand how a polarization of beliefs can occur on social media.

“We live in a very polarized time,” Jurafsky said. “Understanding what different groups of people say and why is the first step in determining how we can help bring people together.”

Analyzing the tweets of Republicans and Democrats

New research by Dora Demszky and colleagues examined how Republicans and Democrats express themselves online in an attempt to understand how polarization of beliefs occurs on social media.

Examining bilingual behavior of children at Texas preschool

A Stanford senior studied a group of bilingual children at a Spanish immersion preschool in Texas to understand how they distinguished between their two languages.

Predicting sales of online products from advertising language

Stanford linguist Dan Jurafsky and colleagues have found that products in Japan sell better if their advertising includes polite language and words that invoke cultural traditions or authority.

Language can help the elderly cope with the challenges of aging, says Stanford professor

By examining conversations of elderly Japanese women, linguist Yoshiko Matsumoto uncovers language techniques that help people move past traumatic events and regain a sense of normalcy.

Shaping the future: Our strategy for research and innovation in humanitarian response.

- Our History

- Work For Us

- Our Annual Reviews

- Anti-racism

- Our Programmes

- Our strategy

- Our long-term commitments

- Focus Areas

- What We Fund

- Global Prioritisation Exercise

- Tools & Research

- Funding Opportunities

- R2HC Support

- HIF Support

- News & Blogs

The value of communicating in the local language

Albert Einstein once commented “If I were given one hour to save the planet, I would spend 59 minutes defining the problem and one minute solving it.”

What is the most important problem or barrier to be addressed when giving someone the knowledge and confidence to do a mission critical job? We suggest it is how you communicate the key information to empower locals and then the ease with which they can translate that knowledge into practical action.

For aid organisations seeking to make training as effective and impactful as possible communication in local languages can make all the differnece. On the one hand working through the local language allows making information as accessible as possible to people who may find themselves in the frontline of an outbreak. On the other hand, it encompasses a participatory approach empowering the local communities. Communicating in ‘their language’ as opposed to ‘our language’ is a critical element in local empowerment, whilst not using their local language can have all kinds of often unintended, but damaging consequences. We carried out a literature search to explore studies in linguistics and healthcare. Local languages are often seen as “minor implementation issue, a mere communication problem, easily overcome with bilingual translators” (Henderson et al. 2014).

Communications quickly coalesce around a single dominant international language. Locals who speak the major language become brokers for services, acting as translators and possibly even becoming part of the local capacity building initiatives. This special role of these often-male brokers who also have a particular role in the community is then also the bottleneck as the validity of the translation cannot be assessed. And of course, bilinguals are people who speak two languages and not professional translators. Providing access to services through majority languages are the harbingers of language endangerment. The local language and knowledge is de-valorised as communication has to be accomplished through a majority language and much is lost in translation. Later, access to aid, resources and support is only possible through the majority language in operation.

The effectiveness of interventions is often hampered due to Western essentialist models of behaviour change and a lack of appropriate knowledge transmission through the local language. It is the local language which encompasses trust and known concepts of illness and healing and treatment practices not the majority language often the language of the rich and powerful. Unintentionally this perspective of local languages as a minor implementation issue is also reinforcing inequalities around education, language, literacy and gender. Longer term they undermine the local languages and cultural practices that are the basis of the local sense of identity, cohesion in communities and resilience going forwards.

In our ebuddi work, we did see these issues at work. When we reached out to many different stakeholders whilst developing the concept of ebuddi many brilliant ideas were shared with us. A musician who had been recording traditional music in West Africa commented how easy it would be to record the voice-overs in different dialects in the field. Using only the simplest of recording devices such as a smartphone, he believed it would be possible to create a database of voiceovers from the Ebola affected region that the trainee – frontline health workers – could select from. We set out to test this idea.

We soon found local voices engaged the trainees more quickly, built a trusted rapport, and were more easily understood. This became evident in the anecdotal feedback from the early trials, when the quality of the voice over, dialect and accent were often commented upon in the evaluation. We did not have the opportunity to systematically explore the value of a local dialect, or gender for that matter; but we believed it important to create a simulated learning environment that was as authentic and immersive as possible.

The first prototype had the option of Krio. We recorded the voiceover working with Diaspora volunteers in London. In trials this was easily identified as ‘London Krio’. During the next phase, we recorded the voices locally – in the communities where ebuddi was being trialled. An additional benefit came from offering choice as well, enabling learners to choose the language they were most comfortable being communicated with, as opposed to the enforced use of an international language for training.

One might expect that communicating in local languages creates an additional complexity in the process of contextualising local capacity building, but what we showed with our development work during the Ebola crisis was that this need not be the case, and the added benefits from authenticity engagement, and equality are overwhelming.

Co-authored by Nicholas Mellor, MiiHealth, and Dr Mandana Seyfeddinipur, Director of the Endangered Languages Documentation Programme, at the Department of Linguistics at SOAS, University of London.

Photo Credit: MiiHealth

Related Project Blogs

Learning from failure -and getting a second chance, innovating in real time, ten requirements for re-imagining public health training in emergencies, we are a force for change. join the conversation....

Subscribe to our newsletters....

You are seeing this because you are using a browser that is not supported. The Elrha website is built using modern technology and standards. We recommend upgrading your browser with one of the following to properly view our website:

- Google Chrome

- Mozilla Firefox

- Microsoft Edge

- Apple Safari

Please note that this is not an exhaustive list of browsers. We also do not intend to recommend a particular manufacturer's browser over another's; only to suggest upgrading to a browser version that is compliant with current standards to give you the best and most secure browsing experience.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

English as a local language: Multilingual practices and post-colonial identities

Related Papers

Cristina Jaimungal

This thesis highlights the sociopolitics of English as a dominant/colonial language by focusing on the linkage between language, power, and race. Grounded in critical language theory, comparative education theory, and anti-racism research methodology, this research examines the inextricable relationship between language, power, and race. With this in mind, this thesis argues that language, specifically English, is not a neutral tool of communication but a highly contentious issue that is deeply embedded in sociopolitical ideologies and practices. The contexts of Japan and Trinidad and Tobago are used to illustrate how colonialism continues to impact English language policy, practice, and perceptions. In sum, this research aims to bridge the gap between critical language theory, comparative education theory, and anti-racism studies in a way that (1) highlights the complexity of language politics, (2) explores ideological assumptions inherent in the discourse of the “native” language,...

This thesis highlights the sociopolitics of English as a dominant/colonial language by focusing on the linkage between language, power, and race. Grounded in critical language theory, comparative education theory, and anti-racism research methodology, this research examines the inextricable relationship between language, power, and race. With this in mind, this thesis argues that language, specifically English, is not a neutral tool of communication but a highly contentious issue that is deeply embedded in sociopolitical ideologies and practices. The contexts of Japan and Trinidad and Tobago are used to illustrate how colonialism continues to impact English language policy, practice, and perceptions. In sum, this research aims to bridge the gap between critical language theory, comparative education theory, and anti-racism studies in a way that (1) highlights the complexity of language politics, (2) explores ideological assumptions inherent in the discourse of the “native” language, and (3) underscores the overlooked ubiquity of race.

Journal of Sociolinguistics

Nazima Rassool

Annual Review of Applied Linguistics - ANNU REV APPL LINGUIST

Brian Morgan

Applied Linguistics

Seyyed-Abdolhamid Mirhosseini

Ruanni Tupas

Awad Ibrahim

Cloris Porto Torquato

This article aims to reflect on the coloniality of language as a vertex of coloniality that acts with coloniality of being, power and knowledge; besides this reflection, it is also my aim to propose alternative ways to challenge the coloniality of language in the context of language education and teachers' education. In the first part of this article, I present some aspects of the coloniality of language, where race and racialisation play an important role (Garcés 2007; Veronelli 2015; Fanon 1967; Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o 1997). In the second part of the article, I propose alternatives to challenge the coloniality of language mainly in the context of language education, focusing on a diversity of voices and knowledges (as plurality) associated with the perspective of language deregulation, as proposed by the Brazilian applied linguist Inês Signorini (2002) and the perspective of heterodiscourse/ heteroglossia as proposed by Mikhail Bakhtin (1981).

Christina Higgins

Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education

Paul J. Meighan

Translanguaging and plurilingual approaches in English Language Education (ELE) have been important for envisaging more equitable language education. However, the languages implemented in translanguaging or plurilingual classrooms predominantly reflect the knowledge and belief systems of dominant, nation-state, “official”, and/or colonial languages as opposed to those of endangered and Indigenous languages. This paper contends that privileging dominant colonial knowledges, languages, and neoliberal valorizations of diversity is Colonialingualism. Colonialingualism, covertly or overtly, upholds colonial legacies, imperial mindsets, and inequitable practices. Colonial languages carry colonial legacies and can perpetuate an imperialistic and neoliberal worldview. Languages can be disembodied from place and commodified as mere “resources”, important only for economic “value” rather than cultural importance, in a “modern” global, neoliberal empire. Colonialingualism resides in the “epistemological error” in dominant western thought, characterized by linguistic imperialism and cognitive imperialism; the view that humans are superior to nature; and white (epistemological) supremacy. This “epistemological error” dominates the current mainstream western worldview, institutions, pedagogies, mindsets, and ways of languaging. Colonialingualism is subtractive and detrimental to multilingual, multicultural learners’ identities and heritages; endangered, Indigenous languages and knowledges; minoritized communities; and our environment. This paper argues that: (1) colonialingualism illustrates the “transformative limits” of translanguaging and plurilingualism; and (2) an epistemic “unlearning” of the western “epistemological error” is required to enable equitable use of all languages, languaging processes, and knowledge systems, including those Indigenous and minoritized, in ELE. The example of heritage language pedagogy in the Canadian context will demonstrate how epistemic “unlearning” while languaging can take place.

RELATED PAPERS

Conrad Masabo

Thomas Cornet

SPEKTRUM INDUSTRI

Imam Santosa

Studi Budaya Nusantara

Aditya Nirwana

New Readings University of Cardiff

Heather Norris Nicholson

Edite do Carmo Guerra Regueiro

Dermatologic Surgery

Nino Japaridze

Archiv Euromedica

Anahit Karapetyan

Materials Chemistry Frontiers

Siobhan Loughnan

Acta Cirurgica Brasileira

samuel miranda

Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences

Julian Dodson

Medical Technology and Public Health Journal

Aisy Rahmania

Thais Batista

2010 23rd SIBGRAPI Conference on Graphics, Patterns and Images

Eduardo Valle

Phụ Nữ Mang Thai Mắc Chứng Ống Cổ Tay Có Nguy Hiểm Không

baubi sausinh

hjhds jyuttgf

LydiaNa SITOHANG

Espaço Ameríndio

Marcos Alexandre Albuquerque

Occupational and Environmental Medicine

youssef mohamed

Clinical Therapeutics

Carla Tavares

IET Microwaves, Antennas & Propagation

Shiban Koul

DOMINIC NWANKWO

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

- Study Abroad /

Should you Learn the Local Language Before Studying in Certain Countries?

- Updated on

- Aug 9, 2023

Language is a major tool that helps people communicate and express themselves. It is also a significant part of a culture. Native or local languages have ancestral and historic values cherished by the people of a community. If you are a study abroad student, then learning the local language spoken at your dream destination can benefit you in a lot of ways. Let’s unravel them through this blog!

This Blog Includes:

Should you learn the local language before studying in certain countries, 1. learning the local language can make life simpler, 2. language is the best way to experience the culture, 3. learning a new language is a beneficial move, 4. learning a new language will help you connect with native speakers always, 5. learning a new language helps you befriend people.

It’s almost time for admissions, and many students prefer to travel overseas to study abroad, to explore new places, people, and new cultures. One of the top study-abroad countries is France, Spain, and Germany where they have their own native languages like French, Spanish, and German. Exploring a new and unique culture means learning a new language as well. But why not spend a couple of minutes a day learning just the basics of the native language being spoken in the country where you are going to study? You don’t have to learn the whole language in a week or a month. You could just learn some of the basics to understand the country or the town better and to navigate yourself within the local areas around your destination. There are many reasons why you should learn the local language before studying in a country, they are:

- You get treated well by the locals if you know their language

- You could have interesting and short conversations with people

- You can understand signs around the place or your institution

- You get connected to local culture and learn to appreciate it

- You can make yourself understood well in extreme situations

- You could also pursue a career in the language if you are interested

Here are some quick tips on – How to Learn a New Language?

Five Advantages of Learning the Local Language

Here are the 5 major reasons for learning local languages before starting your study abroad journey:

You will be able to manage daily activities and routines in the country after you learn the language. There are also ways in which life can become simpler if you learn the language. On a regular basis, think of all the minor experiences you have like navigating, asking and giving directions, or using mass transit. Once they are in a different language, those routine interactions would be a bit difficult. When a cashier inquires, “Did you manage to find everything alright?”, you can fail to understand them.

Don’t get scared about that. That’s part of the learning curve, and if you learn, it’ll become incredibly easy fast. You’ll become a pro when traveling the subway after stumbling for a while, offering directions, and perhaps even being mistaken as a local.

Must Read: How to Become a Language Translator

Language and culture have also been identified as indistinguishable and they have a deeply complicated relationship. Language is not only the true measure of words, linguistic concepts, and creation of sentences but also special cultural values, societal structures, and processes of comprehension. You understand what the goals of a nation are as you learn the tales behind the language. That’s when society starts to understand you. You can learn, hear and reflect about a culture, but hearing its natural language is the best way to profoundly understand a culture.

The process of learning a foreign language helps human brains in several aspects. French, German and Spanish are one of the best foreign languages to learn in this aspect. It enhances memory, boosts imagination and improves the capacity to solve problems. It has also been proven that learning a foreign language enhances your cognitive skills while helping to stave off dementia as you grow old. You also benefit from learning a foreign language in the corporate world.The more languages you know, the more commercially viable you become in this rapidly global business environment. Getting linguistic skills on your application will make prospective employers select you.

Even if you have finished your course in an institution abroad and come back to your home country, if you know the language of your study abroad country and people from there come to visit or you go somewhere else, you can always strike up a conversation in that language to the speakers. If you speak a multi-national language, such as Spanish or French, you will be able to adapt the knowledge you have acquired in one nation to some other area where people speak the local language.

For example, if you had gone to Germany for your higher studies and you learned the language there and you are back and you see a German struggling to converse in your language. You could always help him out. As a speaker of another native language, you can get acquainted with thousands of people all around the country easily. The more fluent you become in this language, the more you can connect to people all over the world!

The world is filled with awesome people. But not many of these people can be English speakers. If you’ve the necessary skills for day-to-day interaction, you can open up your opportunity to speak to dozens of new people! When you understand the local language, people you will meet every day have the opportunity of becoming your future business partner, your closest friend, or your soul mate.

When you learn how to interact with natives, you understand their lives, interests, and aspirations, and how much they’ve become the people they are today. You come to realize that these individuals are much more than a representation of a stereotype. They’re individuals with narratives.

So, we hope that these advantages encourage you to learn that language you’ve always been wanting to learn. Making preparations for language proficiency exams such as IELTS or TOEFL? Our Leverage Live experts are all here to help you develop the perfect training plan, use the best study materials and a doubt clearing session as your comprehensive test preparation! Register for a demo session today!

Team Leverage Edu

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Leaving already?

8 Universities with higher ROI than IITs and IIMs

Grab this one-time opportunity to download this ebook

Connect With Us

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

September 2024

January 2025

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

We're celebrating 50 years of transforming education across the country!

COVID-19 Updates: Visit our Learning Goes On site for news and resources for supporting educators, families, policymakers and advocates.

- Resource Center

Why is it Important to Maintain the Native Language?

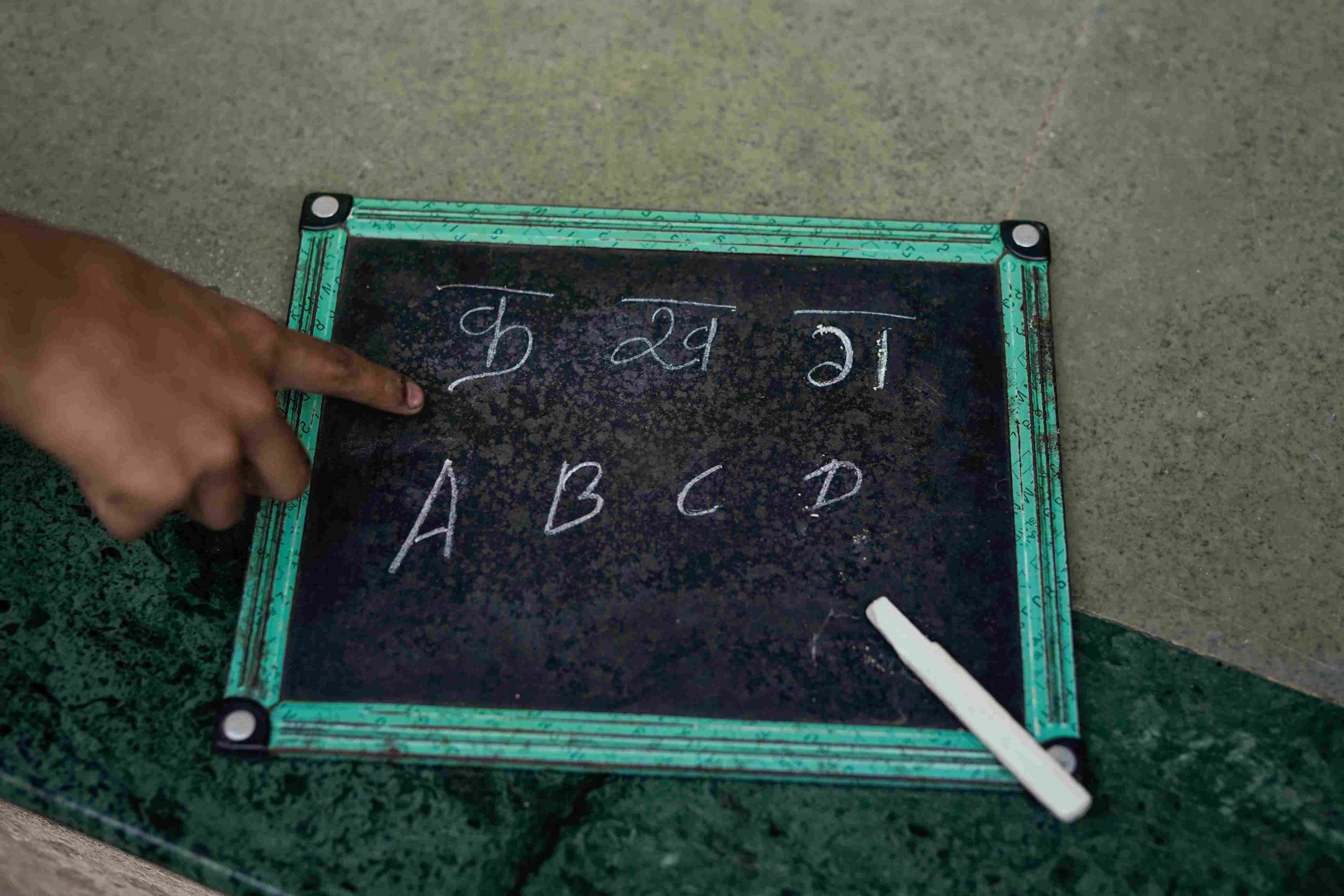

• by National Clearinghouse for Bilingual Education • IDRA Newsletter • January 2000 •

Children who speak a language other than English enter U.S. schools with abilities and talents similar to those of native English-speaking children. In addition, these children have the ability to speak another language that, if properly nurtured, will benefit them throughout their lives. In school, children who speak other languages will learn to speak, read and write English. However, unless parents and teachers actively encourage maintenance of the native language, the child is in danger of losing it and with that loss, the benefits of bilingualism. Maintaining the native language matters for the following reasons.

The child’s first language is critical to his or her identity. Maintaining this language helps the child value his or her culture and heritage, which contributes to a positive self-concept.

When the native language is not maintained, important links to family and other community members may be lost. By encouraging native language use, parents can prepare the child to interact with the native language community, both in the United States and overseas.

Intellectual:

Students need uninterrupted intellectual development. When students who are not yet fluent in English switch to using only English, they are functioning at an intellectual level below their age. Interrupting intellectual development in this manner is likely to result in academic failure. However, when parents and children speak the language they know best with one another, they are both working at their actual level of intellectual maturity.

Educational:

Students who learn English and continue to develop their native language have higher academic achievement in later years than do students who learn English at the expense of their first language.

Better employment opportunities in this country and overseas are available for individuals who are fluent in English and another language.

Collier, V. “Acquiring a Second Language for School,” Directions in Language and Education (1995) 1(4).

Cummins, J. Bilingualism and Minority-Language Children (Toronto, Ontario: The Ontario Institute for Studies in Education, 1981).

Cummins, J. et.al. Schooling and Language-Minority Students: A Theoretical Framework (Los Angeles, California: California State University, School of Education, 1994).

Wong-Fillmore, L. “When Learning a Second Language Means Losing the First,” Early Childhood Research Quarterly (1991) 6, 323-346.

Reprinted with permission from the National Clearinghouse for Bilingual Education’s “AskNCBE” web site (www.ncbe.gwu.edu/askncbe/faqs). NCBE is funded by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Bilingual Education and Minority Languages Affairs (OBEMLA) and is operated by the George Washington University, Graduate School of Education and Human Development, Center for the Study of Language and Education.

Comments and questions may be directed to IDRA via e-mail at [email protected] .

[©2000, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the January 2000 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]

- Classnotes Podcast

Explore IDRA

- Data Dashboards & Maps

- Educator & Student Support

- Families & Communities

- IDRA Valued Youth Partnership

- IDRA VisonCoders

- IDRA Youth Leadership Now

- Policy, Advocacy & Community Engagement

- Publications & Tools

- SEEN School Resource Hub

- SEEN - Southern Education Equity Network

- Semillitas de Aprendizaje

- YouTube Channel

- Early Childhood Bilingual Curriculum

- IDRA Newsletter

- IDRA Social Media

- Southern Education Equity Network

- School Resource Hub – Lesson Plans

5815 Callaghan Road, Suite 101 San Antonio, TX 78228

Phone: 210-444-1710 Fax: 210-444-1714

© 2024 Intercultural Development Research Association

British Council

Why schools should teach young learners in home language, by professor angelina kioko, 16 january 2015 - 13:25.

Photo: British Council

In countries where English is not the first language, many parents and communities believe their children will get a head-start in education by going 'straight for English' and bypassing the home language. However, as Professor Kioko points out, the evidence suggests otherwise.

Many governments, like Burundi recently, are now making English an official national language. Their motivation behind this is to grow their economies and improve the career prospects of their younger generations. Alongside this move, we are seeing a trend, particularly across Sub-Saharan Africa, to introduce English as a medium of instruction in basic education.

However, research findings consistently show that learners benefit from using their home language in education in early grade years (ahead of a late primary transition stage). Yet, many developing countries continue to use other languages for teaching in their schools.

In Kenya, the language of instruction is English, and some learners in urban and some cosmopolitan settings speak and understand some English by the time they join school. But learners in the rural areas enter school with only their home language. For these learners, using the mother tongue in early education leads to a better understanding of the curriculum content and to a more positive attitude towards school. There are a number of reasons for this.

First, learning does not begin in school. Learning starts at home in the learners’ home language. Although the start of school is a continuation of this learning, it also presents significant changes in the mode of education. The school system structures and controls the content and delivery of a pre-determined curriculum where previously the child was learning from experience (an experiential learning mode).

On starting school, children find themselves in a new physical environment. The classroom is new, most of the classmates are strangers, the centre of authority (the teacher) is a stranger too. The structured way of learning is also new. If, in addition to these things, there is an abrupt change in the language of interaction, then the situation can get quite complicated. Indeed, it can negatively affect a child’s progress. However, by using the learners’ home language, schools can help children navigate the new environment and bridge their learning at school with the experience they bring from home.

Second, by using the learners’ home language, learners are more likely to engage in the learning process. The interactive learner-centred approach – recommended by all educationalists – thrives in an environment where learners are sufficiently proficient in the language of instruction. It allows learners to make suggestions, ask questions, answer questions and create and communicate new knowledge with enthusiasm. It gives learners confidence and helps to affirm their cultural identity. This in turn has a positive impact on the way learners see the relevance of school to their lives.

But when learners start school in a language that is still new to them, it leads to a teacher-centred approach and reinforces passiveness and silence in classrooms. This in turn suppresses young learners’ potential and liberty to express themselves freely. It dulls the enthusiasm of young minds, inhibits their creativity, and makes the learning experience unpleasant. All of which is bound to have a negative effect on learning outcomes.

A crucial learning aim in the early years of education is the development of basic literacy skills: reading, writing and arithmetic. Essentially, the skills of reading and writing come down to the ability to associate the sounds of a language with the letters or symbols used in the written form. These skills build on the foundational and interactional skills of speaking and listening. When learners speak or understand the language used to instruct them, they develop reading and writing skills faster and in a more meaningful way. Introducing reading and writing to learners in a language they speak and understand leads to great excitement when they discover that they can make sense of written texts and can write the names of people and things in their environment. Research in Early Grade Reading (EGRA) has shown that pupils who develop reading skills early have a head-start in education.

It has also been shown that skills and concepts taught in the learners’ home language do not have to be re-taught when they transfer to a second language. A learner who knows how to read and write in one language will develop reading and writing skills in a new language faster. The learner already knows that letters represent sounds, the only new learning he or she needs is how the new language ‘sounds’ its letters. In the same way, learners automatically transfer knowledge acquired in one language to another language as soon as they have learned sufficient vocabulary in the new language. For example, if you teach learners in their mother tongue, that seeds need soil, moisture and warmth to germinate. You do not have to re-teach this in English. When they have developed adequate vocabulary in English, they will translate the information. Thus, knowledge and skills are transferable from one language to another. Starting school in the learners’ mother tongue does not delay education but leads to faster acquisition of the skills and attitudes needed for success in formal education.

Use of the learners’ home language at the start of school also lessens the burden on teachers, especially where the teacher speaks the local language well (which is the case in the majority of the rural schools in multilingual settings). Research has shown that in learning situations where both the teacher and the learner are non-native users of the language of instruction, the teacher struggles as much as the learners, particularly at the start of education. But when teaching starts in the teachers’ and learners’ home language, the experience is more natural and less stressful for all. As a result, the teacher can be more creative and innovative in designing teaching/learning materials and approaches, leading to improved learning outcomes.

In summary, the use of learners’ home language in the classroom promotes a smooth transition between home and school. It means learners get more involved in the learning process and speeds up the development of basic literacy skills. It also enables more flexibility, innovation and creativity in teacher preparation. Using learners’ home language is also more likely to get the support of the general community in the teaching/learning process and creates an emotional stability which translates to cognitive stability. In short, it leads to a better educational outcome.

Angelina Kioko is a professor of English and Linguistics at United States International University, Nairobi, Kenya.

Join other education professionals at our LinkedIn group on language-learning in Africa. You can also read more by Professor Angelina Kioko and other writers on this and related topics in our conference publication , which was released as part of a programme called Language Rich Africa. The programme started in March 2014 and continues to involve governments, experts, academics and others in tackling issues concerning multilingual education and the role of English in Sub-Saharan Africa.

The British Council values multilingualism. For more on our stance on language in Africa, please see the Juba conference statement from 2012 (pp.7-8).

Register for an education fair near you.

You might also be interested in:

- How should Africa teach its multilingual children?

- Should non-English-speaking countries teach in English?

View the discussion thread.

British Council Worldwide

- Afghanistan

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Czech Republic

- Hong Kong, SAR of China

- Korea, Republic of

- Myanmar (Burma)

- Netherlands

- New Zealand

- North Macedonia

- Northern Ireland

- Occupied Palestinian Territories

- Philippines

- Saudi Arabia

- Sierra Leone

- South Africa

- South Sudan

- Switzerland

- United Arab Emirates

- United States of America

Language and Literature in a Glocal World

- © 2018

- Sandhya Rao Mehta 0

Sultan Qaboos University, Muscat, Oman

You can also search for this editor in PubMed Google Scholar

- Timely, well researched and broad in scope with examples from a variety of geographical contexts

- Addresses the contemporary concerns of the global-local as articulated in literature and language

- Includes original contributions from renowned academics in the areas of literature and language

6253 Accesses

7 Citations

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this book

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Other ways to access

Licence this eBook for your library

Institutional subscriptions

Table of contents (14 chapters)

Front matter, introduction: framing studies in glocalization.

Sandhya Rao Mehta

Exploring Glocal Discourse

Language in a glocalized world.

- Chandrika Balasubramanian

Code Alternation and Entextualization in Bilingual Advertising: The Construction of Glocal Identities in India’s Amul Butter Ads

English in thai tourism: global english as a nexus of practice.

- Andrew Jocuns

You Are What You Tweet: A Divergence in Code-Switching Practices in Cebuano and English Speakers in Philippines

- Glenn Abastillas

Naming Food and Creating Identity in Transnational Contexts

- Rashmi Jacob, Alka Sharma

The Semiotics of Flags: The New Zealand Flag Debate Deconstructed

- George Horvath

On Gender Silencing in Translation: A Case Study in Poland

- Agnieszka Pantuchowicz

Exploring Glocal Literature

Looking at myth in modern mexican literature, “you inside me inside you”: singularity and multitude in mohsin hamid’s how to get filthy rich in rising asia.

- Micah Robbins

Fears of Dissolution and Loss: Orhan Pamuk’s Characters in Relation to the Treaty of Sèvres

- Fran Hassencahl

Global Connections on a Local Scale: A Writer’s Vision

- Simona Klimkova

Textual Deformation in Translating Literature: An Arabic Version of Achebe’s Things Fall Apart

- Mohamed-Habib Kahlaoui

Pedagogical Perspectives on Travel Literature

- Rosalind Buckton-Tucker

Back Matter

- global forms of knowledge

- decentred world literature

- Ubuntu ethics

- Orhan Pamuk and Turkish literature

- bilingual advertising

- English in Thai tourism

- translation studies

- history of the development of Arabic

- travel literature

- literary diction

About this book

This collection of critical essays investigates the intersections of the global and local in literature and language. Exploring the connections that exist between global forms of knowledge and their local, regional applications, this volume explores multiple ways in which literature is influenced, and in turn, influences, movements and events across the world and how these are articulated in various genres of world literature, including the resultant challenges to translation. This book also explores the way in which languages, especially English, transform and continue to be reinvented in its use across the world. Using perspectives from sociolinguistics, discourse analysis and semiotics, this volume focuses on diasporic literature, travel literature, and literature in translation from different parts of the world to study the ways in which languages change and grow as they are sought to be ‘owned’ by the communities which use them in different contexts. Emphasizing on interdisciplinary studies and methodologies, this collection centralizes both research that theorizes the links between the local and the global and that which shows, through practical evidence, how the local and global interact in new and challenging ways.

Editors and Affiliations

About the editor.

Sandhya Rao Mehta is presently with the Department of English Language and Literature at Sultan Qaboos University in Muscat, Oman. She has published widely in the fields of English Language, with particular focus on English Language teaching (ELT) and critical thinking in language teaching. She has also worked on Diaspora Studies, gendered migration and postcolonial fiction, focusing on literature of the Indian diaspora. She is the co-editor of Language Studies: Stretching the Boundaries and editor of Exploring Gender in the Literature of the Indian Diaspora .

Bibliographic Information

Book Title : Language and Literature in a Glocal World

Editors : Sandhya Rao Mehta

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-8468-3

Publisher : Springer Singapore

eBook Packages : Social Sciences , Social Sciences (R0)

Copyright Information : Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd. 2018

Hardcover ISBN : 978-981-10-8467-6 Published: 12 July 2018

Softcover ISBN : 978-981-13-4160-1 Published: 23 December 2018

eBook ISBN : 978-981-10-8468-3 Published: 29 June 2018

Edition Number : 1

Number of Pages : XIX, 240

Number of Illustrations : 1 b/w illustrations, 34 illustrations in colour

Topics : Language Education , Language and Literature , Postcolonial/World Literature

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Explore All Courses

- New Build Your Professional Resume

- New Master Class

- Terms & Conditions

- Refer & Earn

- Hire From Us

- Hire from us

- Secure Your Salary

- Our Company

- New Refer, Earn with ELC

- Help Center

- Terms & Conditions

- The Importance of Learning Regional Languages in India

Subscribe to EduBridge Blogs

Introduction.

Regional language is a term used to refer to a language that is spoken by a sizeable number of people but is not the de facto language of communication in the rest of the country. A language is considered regional when it is mostly spoken by people who reside largely in one particular area of a state or country.

The status of regional language is often given to languages that satisfy two main criteria:

- The language is used by people who have a population less than the majority of the state or nation

- It is not the official language of the country.

What are Regional Languages

Regional languages are languages spoken in specific regions or areas within a country. They are distinct from the official or national languages of the country and are often used to communicate within a particular geographic region. Regional languages may vary in vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation and writing system compared to the official languages. These languages play a significant role in preserving local cultures, traditions and identities. Next, let’s look at the number of regional languages in India.

How many Regional Languages are there in India

Even though Article 343(1) of the Indian Constitution states that “the official language of the Union shall be Hindi in Devanagari Script”, there are 22 officially recognized regional languages in India which include:

01. Assamese 02. Bengali 03. Bodo 04. Dogri 05. Gujarati 06. Kannada 07. Kashmiri 08. Konkani 09. Maithili 10. Malayalam 11. Manipuri 12. Marathi 13. Nepali 14. Odia 15. Punjabi 16. Sanskrit 17. Santali 18. Sindhi 19. Tamil 20. Telugu 21. Tulu 22. Urdu

Significance of Regional Languages Pre-Independence

The vernacular press was crucial in the Indian Freedom Struggle. The first organized insurrection against the British by patriotic Indians, mainly credited to Mangal Pandey and the ‘Sepoy Mutiny,’ was the first organized revolt against the British by patriotic Indians. With the establishment of the first vernacular press only 1 year shy of 4 decades ago, regional language newspapers and other written media began to substantially propagate the same nationalistic zeal through vernacular media. This grew into a significant movement, and many local Indians began to speak out. In order to curb this rising tide of nationalistic enthusiasm, the British passed the Vernacular Press Act in 1878, which Indians termed “the Gagging Act” since it regulated the press freedom in the country and applied to the vernacular medium alone. However, it was repealed in 1882, following which the nationalistic fervor of the country steadily grew. Some of the most popular vernacular media at the time include the Bengal Gazette, Kesari, Paridasak, and Moon Nayak, among others.

The importance of Regional Language

Regional languages in India hold vital roles in different aspects. The preservation and promotion of regional languages alongside the official languages to maintain linguistic diversity and uphold the cultural fabric of society. Let’s understand what’s the importance of regional language in brief:

- Cultural identity: Regional languages in India are closely tied to the cultural heritage and identity of specific regions or communities. They preserve and transmit unique customs, traditions, folklore, literature and oral histories that contribute to the rich cultural diversity of a country.

- Communication and Inclusion: Regional languages serve as a means of communication for millions of people who may not be fluent in the official or national language. They enable effective communication within local communities, fostering social cohesion and inclusion.

- Education and Literacy: Learning in one’s mother tongue or regional language has proven benefits for education and literacy. Children tend to grasp concepts better when taught in a language they understand well, this is one of the importance of regional language in education. Regional language instruction also helps preserve indigenous knowledge and encourages the development of bilingualism or multilingualism.

- Economic Development: One of the importance of regional language is the role it plays in economic activities within specific regions. It facilitates local trade, commerce, tourism and cultural industries, contributing to the overall economic development and growth of the region.

- Political Representation: In countries with diverse linguistic communities, recognizing and promoting regional languages can ensure political representation and participation from different regions. Regional languages in India empower local communities, giving them a voice in governance and decision-making processes.

- Preserving Linguistic Diversity: Regional languages represent the linguistic diversity of a country or region. Protecting and promoting regional languages is essential for maintaining the richness of human languages and ensuring their survival for future generations.

- Emotional Connection: Regional languages in India often evoke a sense of belonging, emotional attachment and pride among speakers. They foster a deeper connection to one’s roots, heritage and local community, strengthening individual and collective identities.

Why regional languages should be taught in schools?

In an era when the entire world is quickly globalizing, what role does regional language play? Shouldn’t we be focusing on educating pupils to speak global languages like English and Spanish? This is a compelling question, but the answer requires careful pragmatic analysis of the spread and reach of those languages in the inner workings of a country, as well as how much effort needs to be put into retraining the majority of the working population in that language – which requires not only an additional blog, but also a lot of linguistic and cultural research, which is not the subject of this blog.

This is presented not as a counterargument to the claim mentioned above, but rather as an alternative approach to its opposite paradigm – what’s the advantage of learning regional languages?

Helps People Connect With The Language’s Culture

Every regional language has a rich complex history, especially in a multicultural culture like India with a history of over 5000 years. People who do not speak this language and are not familiar with its culture are completely cut off from it. Teaching regional languages to pupils allows them to gain an insider’s perspective on the secret knowledge and culture concealed beneath the veil of that language.

In this context, culture includes more than simply literature; it also includes dance, music, sculpture, architecture, and other arts.

Easier Communication for Education

Education has the strange dichotomy of being structured on an industrial scale while still being profoundly individualized in nature. This produces a mismatch in thinking among pupils, particularly those who are not comfortable with English as a medium of instruction. Regional language can address this gap by having the teacher describe the subject in the student’s native tongue so that the student can understand the main notion and replicate it in the exam in their own words.

Knowing an Extra Language

The more languages you know, the more people you will be able to communicate effectively with. There is no shame associated with either knowing or not knowing a language, but it would be better to know as many languages as possible for a more wholesome and holistic all-round education.

Are regional languages mandatory in schools?

In India, the language policy for schools varies depending on the state and region. The Constitution of India recognizes both regional languages and the official languages of the country, which include Hindi and English. The respective state government decides the inclusion and teaching of regional languages in schools.

Many states in India do include regional languages as a compulsory subject in the school curriculum. In these states, students are required to study the regional language as a subject alongside the language they are pursuing their education. The importance of regional language in education is to ensure cultural continuity and provide education in the mother tongue or the language of the local region.

E.g. Students in Maharashtra pursuing their education from the State Board of Maharashtra- Learning the Marathi language is a must.

As you can see, regional languages have played, continue to play, and will continue to play a vital role in a nation’s socioeconomic, political, and educational growth. It has the potential to bring people together and help them connect with one another better.

This is not an attempt to glorify a specific regional language or downplay the importance of national languages; rather, it is a reminder to connect with one’s roots and understand the cultural relevance and historical significance of something that is simply considered one’s mother tongue – knowledge has a lot more power than meets the eye.

FAQs related to the Importance of Learning Regional Languages

What are the important regional languages of india.

India is a linguistically diverse country with numerous regional languages spoken across its different states and regions. Some of the important regional languages in India as in chronological order, the first ranking is Hindi -52.83 crore speakers followed by the others i.e. Bengali – 9.72 crore speakers, Marathi – 8.30 crore speakers, Telugu – 8.11 crore speakers, Tamil – 6.90 crore speakers, Gujarati – 5.54 crore speakers, Urdu – 5.07 crore speakers, Kannada – 4.37 crore speakers, Odia – 3.75 crore speakers and Malayalam – 3.48 crore speakers

What is the importance of Local language in India?