Ongoing Series

- Collaborations

- Newsletters

- Opportunities

The ‘Lion Capital’: a Buddhist symbol that became India’s National Emblem

In adopting symbols from the Ashokan period, the modern nation of India was borrowing it's ideals and values from a rich and glorious past. Take a deeper look at the Lion Capital kept at the ASI Sarnath Museum, and it's replica at the Rashtrapati Bhavan Museum.

The National Emblem, India’s most visible symbol of national identity, reflects the country’s reaffirmation of it’s ancient ideals of peace and tolerance. Adapted from the design of the Lion Capital of an Ashokan pillar, it was officially adopted on January 26, 1950 along with the motto “Satyameva Jayate” which has been taken from the Mundaka Upanishad and translates to “truth always triumphs”.

On 22 July, 1947, just before India’s independence, Jawaharlal Nehru proposed a resolution, before the Constituent Assembly, for the design of the new Flag and Emblem. Both of these, as Nehru noted, referenced the golden rule of the Mauryan King, Ashoka. In adopting national symbols from the Ashokan period, the modern nation of India was borrowing it’s ideals and values from a rich and glorious past.

“Now BECAUSE I have mentioned the name of Asoka I should like you to think that the Asokan period in Indian history was essentially an international period of Indian history. It was not a narrowly national period. It was a period when India’s ambassadors went abroad to far countries and went abroad not in the way of an empire and imperialism but as ambassadors of Peace and culture and goodwill.” – Jawaharlal Nehru at the Constituent Assembly

Design & Significance

The animals.

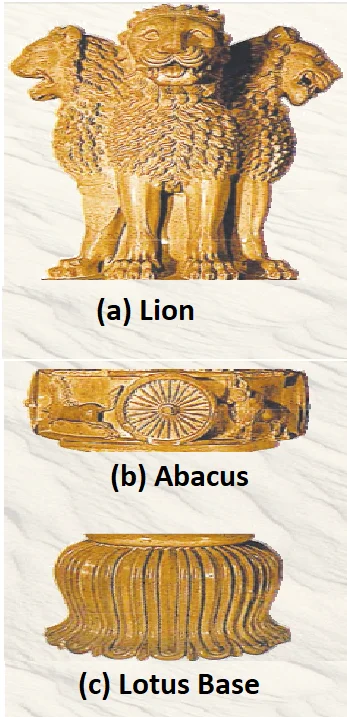

At first glance, you notice the four majestic lions , roaring and facing the four cardinal directions. They represent power, courage, pride, confidence. The Mauryan symbolism of the lions indicate “the power of a universal emperor (chakravarti) who dedicated all his resources to the victory of dharma”. In adopting this symbolism, the modern nation of India pledged to equality and social justice in all spheres of life.

The lions sit atop a cylindrical abacus, which is adorned with representations of a horse, a bull, a lion and an elephant, made in high relief. While some art historians believe that these animals symbolically depict various stages of Buddha’s life, others claim that they represent the reign of Ashoka in the four quarters of the world; the open-mouthed lions facing different directions, suggest the announcement of Buddha’s message to the world.

The Wheel with 24 Spokes : Ashok Chakra / Dharmachakra

The animals are separated by intervening chakras (having 24 spokes). The Chakra also finds representation on the National Flag. This chakra, or the ‘Wheel of Law’ is a prominent Buddhist symbol signifying Buddha’s ideas on the passage of time. Dharma (virtue), according to belief, is eternal, continuously changing & is characterized by uninterrupted continuity. It is also said, that the 24 spokes align with the 24 qualities of a Buddhist follower, as defined by the Buddha in his sermons.

These 24 qualities are: Anurāga(Love), Parākrama(Courage), Dhairya(Patience), Śānti(Peace/charity), Mahānubhāvatva(Magnanimity), Praśastatva(Goodness), Śraddāna(Faith), Apīḍana(Gentleness), Niḥsaṃga(Selflessness), Ātmniyantranā(Self-Control), Ātmāhavana(Self Sacrifice), Satyavāditā(Truthfulness) Dhārmikatva(Righteousness), Nyāyā(Justice), Ānṛśaṃsya(Mercy), Chāya(Gracefulness) Amānitā(Humility), Prabhubhakti(Loyalty), Karuṇāveditā(Sympathy), Ādhyātmikajñāna(Spiritual Knowledge), Mahopekṣā(Forgiveness), Akalkatā(Honesty). Anāditva(Eternity), Apekṣā(Hope)

At the base is an inverted lotus, the most omnipresent symbol of Buddhism, and India’s National Flower. This is however, not part of the Emblem.

The Lion Capital at Sarnath

The Lion capital was originally a part of the pillar constructed by Ashoka, the great emperor of the Mauryan dynasty who created the largest empire of ancient India. After the bloody conquest of Kalinga which claimed more than 1,00,000 lives, a deeply distraught Ashoka found solace in the teachings of Buddha. It wasn’t long before Buddhism directly began to influence the politics of the period, as clearly seen in the pillar constructed by Ashoka at Sarnath.

Ashoka’s administration became known for it’s strong ideals of social justice, compassion , non-violence and tolerance ; he instated a legal code based on Buddha’s teachings and had these inscribed on columns erected all across his kingdom. These edicts (inscriptions on pillars, boulders and even cave walls) focused on social and moral codes that were part of Buddhist beliefs (and not the religious philosophy).

The pillar at Sarnath bore special significance because it was believed that it was here that Buddha gave his first sermon and stated his famous ‘Four Noble Truths’.

Ashokan Pillars: the cornerstone of Mauryan Art

Ashoka’s Pillars, 30-40 ft in height are considered to be the first monumental stone-artworks in India. These pillars extended deep into the ground, and were located across pilgrimage routes, sites associated with the Buddha, and roads leading to Pataliputra (present day Patna). These pillars also had elaborate capitals crafted out of a single block of sandstone. Take a look at this one, for instance:

Art historians have often referred to a Greek influence on the design and craftsmanship of these capitals. In the Lion Capital below, the abacus is decorated with geese.

While most capitals featured a single animal, the Lion Capital at Sarnath (believed to have been erected in 250 BC) was the most elaborate. It was excavated in 1905 by a German-born civil engineer, Friedrich Oscar Oertel.

He started excavating the area following the accounts of the Chinese travellers who visited Sarnath in the early medieval period. Like everything else, the excavated pillar too had deteriorated over time and had broken into three pieces. Fortunately, the Lion Capital had remained intact with its glimmer still visible. It is currently kept at the Sarnath Museum where you can still admire its exquisite craftsmanship.

An ancient symbol for a modern nation:

The question still remains : how did the Lion Capital become the national emblem of India? In 1947, as independence seemed nearer, Nehru and other nationalist leaders realized that their soon nation-to-be lacked a national emblem. Art schools all over India were called for suggesting designs, but nothing suitable could be found. Eventually, Badruddin Tyabji, a civil services officer, and his wife Surayya Tyabji, proposed the usage of the Ashokan capital for the emblem. Years later, Laila Tyabji, their daughter, writes:

So, my mother drew a graphic version and the printing press at the Viceregal Lodge (now Rashtrapati Niwas) made some impressions and everyone loved it. Of course, the four lions have been our emblem ever since.” She further says, “My mother was 28 at the time. My father and she never felt they had “designed” the national emblem – just reminded India of something that had always been part of its identity. Source: The Wire

Artist Dinanath Bhargava, then a student at Shantiniketan was later tasked with designing the final emblem; he then sketched it onto the first page of the Constitution under the able mentorship of Nandalal Bose.

The Lion Capital or the National Emblem is a ubiquitous image in India. You don’t need to go far to fathom its pervasiveness; just open your wallet and you will find it right there – embossed over every coin and every currency note that you possess. Not only this, it’s presence in all prominent government documents and buildings as well as in all our school textbooks or passports has turned it into a symbol that evokes emotional attachment and a sense of national identity.

Classroom Connections:

How can symbols express our values? Can you think of any symbols in your personal life that represent your beliefs / values?

Why is Ashoka relevant to 20th century modern India?

When Le Corbusier designed the modern city of Chandigarh, he asked Nehru for help on symbols. Nehru is believed to have told the French architect to come up with his own symbols instead of referencing India’s known symbols. That is when the ‘Open Hand’ was introduced by Corbusier as the emblem of Chandigarh. Imagine if you were to create symbols for your city (or India) that would represent it’s ethos. What would you create?

Liked reading? Sign up for more!

- National Symbols

Explore More

- Objects / Collections

- Looking At Art

‘Darvesh’ : The S.L. Parasher sculpture inspired by an ancient Sufi dance

‘hiranyagarbha’ (the golden egg) by manaku, ‘salam chechi’ : a tribute to malayali nurses by artist nilima sheikh, ‘the last supper’ in modern indian art, “a typical shantiniketan girl” and other identities of rani chanda, #chalomuseum : visiting museums in india, #chalomuseum: take the pledge, #dollypartonchallenge : the real social-media message for museums, #embracedigitaltalk : the changing role of museum websites, #heritagejigsaw : david sassoon library by foy nissen, click culture.

Submit a photo of your favourite object from a museum collection to help us improve the coverage of Indian culture, art and heritage related content on the internet beginning with Wikipedia.

Add your Museum Photo

"What is this?" is a crowdsourced campaign featuring museum objects. You can share a photo of an object, and we will share its historical and cultural context for further use with an open license as part of our ongoing endeavour to make culture & knowledge accessible to everyone.

See Examples

Share this story via

Or copy the link

Lion Capital of Ashoka

The Lion Capital of Ashoka is the capital , or head, of a column erected by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka in Sarnath , India, c. 250 BCE . Ashoka erected the column to commemorate the site of Gautama Buddha 's first sermon some two centuries earlier.

Its crowning features are four life-sized lions set back to back on a drum-shaped abacus , representing the four noble truths . The side of the abacus is adorned with wheels in relief, and interspersing them, four animals, a lion, an elephant, a bull, and a galloping horse follow each other from right to left. A bell-shaped lotus forms the lowest member of the capital, and the whole 2.1 metres (7 ft) tall, carved out of a single block of sandstone and highly polished, was secured to its monolithic column by a metal dowel.

The capital eventually fell to the ground and was buried. It was excavated by the Archeological Survey of India (ASI) in the very early years of the 20th century. The column, which had broken before it became buried, remains in its original location in Sarnath, protected but on view for visitors. The Lion Capital was in much better condition, though not undamaged. It was cracked across the neck just above the lotus, and two of its lions had sustained damage to their heads. It is displayed not far from the excavation site in the Sarnath Museum , the oldest site museum of the ASI.

In July 1947, Jawaharlal Nehru, the interim prime minister of India, proposed in the Constituent Assembly of India that the wheel on the abacus be the model for the wheel in the centre of the Dominion of India's new national flag , and the capital itself without the lotus the model for the state emblem of India . The proposal was accepted in December 1947.

Further reading:

- Buddhist architecture

- Buddhist art

- Buddhism in India

- Imported from Wikipedia

Navigation menu

- Architecture

- Living Traditions

- Modern & Contemporary Art

- Photography

- Pre-Modern Art

- Prehistoric Era (–7000 BCE)

- Bronze Age (3300 BCE–1200 BCE)

- Iron Age (1200 BCE–200 BCE)

- Ancient Period (200 BCE–500 CE)

- Early Medieval Period (500 CE–1200 CE)

- Late Medieval Period (1200–1500)

- Early Modern Period (1500–1757)

- Modern Period (1757–1947)

- Post Colonial Period (1947–1990)

- Contemporary (1990–)

- Central India

- Eastern India

- Northeastern India

- Northern India

- Northwestern India & Pakistan

- Peninsular India

- Southern India

- Undivided Bengal

- Western India

- Administrators

- Gallerists & Dealers

- Illustrators

- Photographers

- Art History & Theory

- Awards & Recognitions

- Archaeology

- Architecture & Urban Planning

- Art Education

- Art Markets

- Arts Administration

- Books and Albums

- Ceramics & Pottery

- Chemical & Natural Solutions

- Conservation & Preservation

- Decorative Arts

- Display of Art

- Environmental Art

- Events & Exhibitions

- Film & Video

- Gardens & Landscape Design

- Graphic Design & Typography

- Illustration

- Industrial & Commercial Art

- Installation Art

- Interior Design & Furniture

- Liturgical & Ritual Objects

- Manuscripts

- Mixed-Media

- Museums & Institutions

- Mythological Figures

- Painting & Drawing

- Performance Art & Dance

- Prints & Printmaking

- Scenography

- Sculpture & Carving

- Textiles & Embroidery

- Encyclopedia of Art

- Online Courses

- About the MAP Academy

- What is Art History?

- Opportunities at the MAP Academy

- Partnerships

- Terms and Conditions

- Find us on instagram

Mask of Vaikuntha Vishnu, late 5th century. Learn more about 5th century masks

In an attempt to keep our content accurate and representative of evolving scholarship, we invite you to give feedback on any information in this article.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

I agree to the terms outlined in the MAP Privacy Policy. I would like to subscribe to the MAP Academy mailing list.

Lion Capital, Sarnath

Articles are written collaboratively by the EIA editors. More information on our team, their individual bios, and our approach to writing can be found on our About pages . We also welcome feedback and all articles include a bibliography (see below).

One of the earliest stone sculptures made under the patronage of the Mauryan king Ashoka, the lion capital at Sarnath, Bihar, depicts four male Asiatic lions seated on a round abacus with their backs to each other. The capital is carved from a single block of highly polished Chunar stone that is separate from the block used for the pillar shaft , which features the inscribed edicts of Ashoka. The most elaborately carved of all surviving Ashokan capitals, the lion capital stands at a height of two meters and is dated to ca . 250 BCE. The broken remnants of the pillar, as well as the complete, but detached, capital were formally excavated around the year 1905 by F O Oertel. The capital is believed to have originally been attached on top of the pillar. Also among the findings were fragments of a large dharmachakra stone with thirty-two spokes, which is presumed to have rested on the capital in a likely reference to the Buddha’s first sermon.

The four lions comprising the capital are depicted with their mouths open as if mid-roar and their manes are arranged in neat ringlets. They also portray an understated but carefully studied musculature. Scholars claim that the eye sockets of the lions were once fitted with semi-precious stones. The overall form of the lions is poised, heavily stylised and compact, similar to the lion images carved in Achaemenid Persia, which is a known source of influence for Mauryan architecture. In addition, the abacus features four animals — an elephant, a lion, a bull and a horse, carved in high relief and suggesting that the sculptor(s) may have been familiar with the anatomies of the animals. They appear to be moving in a clockwise direction and are separated by four chakras with twenty-four spokes each. The abacus rests on an upturned, bell-shaped lotus with elongated, fluted petals, which are also believed to have been borrowed from the Achaemenid style of architecture.

Sarnath is the site of the Buddha’s first sermon and the lion capital is believed to have been built to commemorate the occasion. Therefore, the various icons that appear on the capital are recurring symbols within Buddhism. The dharmachakra is a solar symbol with its origin in many faiths and, therefore, has multiple interpretations. Here, it is believed to represent the Buddha “turning the wheel of the law” with his first sermon at Sarnath. It also possibly refers to Ashoka’s title of Chakravartin , meaning “a ruler whose chariot wheels roll everywhere.”

Some sources interpret the lions as personifying the Shakyamuni (of the Shakya , or lion, clan) Buddha who preached his sermons at Sarnath. Their open mouths are interpreted as spreading the Buddha’s teachings, the Four Noble Truths, far and wide. An almost identical lion capital with its mouth open is found at the Sanchi pillar, which is another site where the Buddha is believed to have delivered sermons. Some interpretations suggest that the lions symbolise not only Buddha, but also Ashoka. As a significant ruler of the first historical empire in India with a vast geographical reach, strong relations with foreign states and diverse secular cultures, Ashoka was held in parallel with the Buddha, having limitedly imbibed the Buddhist way of life.

The animals on the abacus are interpreted differently by various scholars. According to Alfred Charles Auguste Foucher, and later accepted by most other scholars, the four animals are associated with the four milestone events in the Buddha’s life: the elephant, representing his mother Queen Maya’s dream of a white elephant entering her womb; the bull, representing his birth under the astrological sign Vrishabha; the horse, representing Kantaka, the horse on which Buddha fled his palace to pursue asceticism; and the lion, representing the enlightened Buddha and often known as Shakyasimha . The animals are depicted running in the clockwise direction and separated by four dharma chakras, possibly signifying the intention of setting the wheel in motion through the cycle of life or representing the Buddha setting the wheel in motion at the sermon at Sarnath. Another prevalent opinion is that these animals face the cardinal directions. They have also been identified as the four perils of samsara — birth, disease, death and decay — following each other in an endless cycle. The upturned lotus that the capital rests on represents purity in Buddhist art, sculpture, ritual and theory and symbolises rising above the mundanity of life to attain enlightenment.

In 1950, three years after Indian independence, the lion capital at Sarnath was adopted as the emblem of the Republic of India, with the lions representing virtues such as pride, power, courage and confidence. The inverted lotus bell has been omitted, and the motto ‘Satyameva Jayate, meaning “truth alone triumphs,” is inscribed in Devanagari script below the abacus. The original lion capital is now preserved at the Sarnath Museum, near Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh.

Bibliography

Our website is currently undergoing maintenance and re-design, due to which we have had to take down some of our bibliographies. While these will be re-published shortly, you can request references for specific articles by writing to [email protected] .

map_academy

Be the first to hear about all the latest MAP Academy articles, online courses and news.

I understand that this site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply, as well as the MAP Academy Privacy Policy

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

THE ASHOKAN PILLAR -MANY LIVES, MANY MEANINGS

Ashoka's legacy is carreid through the sandstone pillars that were erected during his rule in various parts of northern India. These pillars were inscrbed upon with edicts revealing Ashoka's intended policy framework of Dhamma for his subjects and neighbours. However, there are pillars that have been discovered without either capitals or inscriptions, and in some cases neither Ashokan evidence exists. Therefore, there has been further reason to explore the origins of these pillars. although the initial exploration was driven more by the aesthetic beauty of these pillars. This essay tries to shed light on both perspectives - historical and aesthetic - that make these pillars and their animal capitals powerful symbols in Indian culture.

Related Papers

NMML OCCASIONAL PAPER HISTORY AND SOCIETY New Series 88

Meenakshi Vashisth

Bairat region falls within the present political boundaries of district Jaipur in the state of Rajasthan. Considering that Bairat has yielded two Ashokan Inscriptions—the Calcutta-Bairat Rock Edict and the Minor Rock Edict I—it must have formed a region of importance in Mauryan times. This may well be why Emperor Ashoka chose it as one of the places for the spreading of his messages. This paper is an attempt to study the texts of these Ashokan inscriptions by placing them within their geographical and archaeological landscapes since the selection of places for putting up the royal messages was not arbitrary. So, the language, script, and content of the edicts with their geo-cultural settings are studied in relation with each other. Analysing the archaeological importance and understanding the history and cultural continuity of Bairat region through its material remains while examining and exploring references from textual sources is its focus.

Reimagining Asoka: Memory and History

Himanshu Prabha Ray

In 1905, the Archaeological Survey of India undertook excavations at Sarnath and it was during these operations that an Ashokan pillar was unearthed in a broken and damaged condition along with the lion capital measuring seven feet in height. The lion capital carved out of a single block of sandstone comprised of four magnificent lions standing back to back surmounted on a drum with four animals carved on it placed between four wheels. It was this Sarnath lion capital with a legend from the Mundaka Upanishad reading satyameva jayate or truth alone triumphs that was adapted as an emblem of independent India to be represented on money, official government stationery and so on. The adoption of an ancient symbol by a modern nation is significant and the question that this paper addresses relates to the beginnings of archaeology in the subcontinent, as it was practised through a colonial institution, i.e. the Archaeological Survey of India. Was the choice of Ashokan symbols, i.e. the cakra and the Sarnath lion pillar, a ‘creation’ of a non-sectarian past to suit national expediencies, particularly after the partition of India along religious lines? The issue can be addressed at two levels: one is with reference to the modern history of the ‘discovery’ of Ashoka by the Europeans in the nineteenth and early twentieth century and the extent to which this overshadowed the writing of history in the subcontinent over the last two hundred years. The second is through a reanalysis of the archaeological data and the extent to which it allows for a re-evaluation of a ‘unified state’ as it evolved under the Mauryas.

Ranajit Pal

The vanishing of the twelve magnificent altars set up by Alexander the Great has intrigued many scholars. This article shows that one of the altars was re-inscribed by Emperor Asoka, who was the Indo-Greek King Diodotus I. There is an indication that Alexander may have tried to promote brotherhood in these altars. It is just possible that the four-lion emblem of India may be linked to Alexander.

Srini Kalyanaraman

on Rampurva Aśoka pillars, copper bolt (metal dowel), bull & lion capitals are proclamations, ketu -- yajñasya ketu-- of Soma Yāga performance. All the pillars of Ashoka are built at Buddhist monasteries. “The pillars have four component parts in two pieces: the three sections of the capitals are made in a single piece, often of a different stone to that of the monolithic shaft to which they are attached by a large metal dowel. The shafts are always plain and smooth, circular in cross-section, slightly tapering upwards and always chiselled out of a single piece of stone. The lower parts of the capitals have the shape and appearance of a gently arched bell formed of lotus petals. The abaci are of two types: square and plain and circular and decorated and these are of different proportions. The crowning animals are masterpieces of Mauryan art, shown either seated or standing, always in the round and chiselled as a single piece with the abaci.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pillars_of_Ashoka#cite_ref-7 The appearance of capitals as bells signifies bronze-working competence: kaṁsá1 m. ʻ metal cup ʼ AV., m.n. ʻ bell -- metal ʼ Pat. as in S., but would in Pa. Pk. and most NIA. lggs. collide with kāˊṁsya -- to which L. P. testify and under which the remaining forms for the metal are listed. 2. *kaṁsikā -- . 1. Pa. kaṁsa -- m. ʻ bronze dish ʼ; S. kañjho m. ʻ bellmetal ʼ; A. kã̄h ʻ gong ʼ; Or. kãsā ʻ big pot of bell -- metal ʼ; OMarw. kāso (= kã̄ -- ?) m. ʻ bell -- metal tray for food, food ʼ; G. kã̄sā m. pl. ʻ cymbals ʼ; -- perh. Woṭ. kasṓṭ m. ʻ metal pot ʼ Buddruss Woṭ 109.2. Pk. kaṁsiā -- f. ʻ a kind of musical instrument ʼ; K. k&ebrevdotdot;nzü f. ʻ clay or copper pot ʼ; A. kã̄hi ʻ bell -- metal dish ʼ; G. kã̄śī f. ʻ bell -- metal cymbal ʼ, kã̄śiyɔ m. ʻ open bellmetal pan ʼ.kāˊṁsya -- ; -- *kaṁsāvatī -- ?Addenda: kaṁsá -- 1: A. kã̄h also ʻ gong ʼ or < kāˊṁsya -- .(CDIAL 2576) Bull capital, lion capital on Rampurva Aśoka pillarss An Indus Script hypertext message on the copper bolt which joins the bull capital with the pillar is about metalwork competence of artisans of Rampurva who made the pillar with capital. The decorative motifs on the abacus are also Indus Script hypertexts documenting metallurgical competence. The abacus of the bull capital shows pericarp of lotus, rhizomes, palm fronds. These signify: कर्णिक, कर्णिका f. the pericarp of a lotus rebus: कर्णिका 'steersman, helmsman' (seafaring merchant) PLUS (base of the abacus) tāmarasa 'lotus' rebus: tāmra 'copper' PLUS sippi 'mollusc', śilpin, sippi 'artificer'. Thus, the hypertext message is: helmsman, coppersmith artificer. The abacus of the lion capital show decorative motifs of aquatic birds, hamsa and varāha 'boars'. These Indus Script motifs signify: বরাহ barāha 'boar'Rebus: bāṛaï 'carpenter' (Bengali) bari 'merchant' barea 'merchant' (Santali) बारकश or बारकस [bārakaśa or bārakasa] n ( P) A trading vessel, a merchantman. The animals on the capital are Indus Script hypertexts: 1. Zebu: पोळ pōḷa 'zebu, bos indicus' rebus: पोळ pōḷa 'magnetite (a ferrite ore)' 2.. arā 'lion' rebus: āra 'brass', ārakūṭa 'brass alloy' The pillars upholding the capital are Indus Script hypertexts: skambha 'pillar' rebus: kampaṭṭam, kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'. Thus, these pillars with animal capitals of Rampurva are proclamations of metal- and mint-work by artisans of Rampurva. The tradition of mounting a pillar as a proclamation of performance of Soma Yāga is a tradition documented in R̥gveda which refers to an octagonal pillar as ketu. aṣṭāśri yūpa, a ketu to proclaim a somasamsthā yāga. The expression used describe the purport of the yūpa is: yajñasya ketu (RV 3.8.8). Hieroglyphs on the two-and-a-half feet long Rampurva copper bolt which joinss the bull capital to the pillar: 1. goṭ 'seed' Rebus: koṭe ‘forging (metal) 2. kanda 'fire altar' rebus: khaṇḍa 'metal implements'. 3. goṭ 'round, stone' Rebus: khoṭ 'alloy ingot' PLUS aya khambhaṛā 'fish fin' Rebus: aya kammaṭa 'iron mint' 4. ḍanga 'mountain range' rebus: ḍangar 'blacksmith' PLUS bhaṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace'. Thus, the hypertext on the Rampurva copper bolt is 1. a professional calling card of the metalsmithy/forge artisan with competence in forging metal implements, with iron mint and furnace and 2. proclamation of the performance of a Soma Yāga. Thus, Indus Script hypertexts seen on Rampurva Aśoka pillars, copper bolt, bull & lion capitals are proclamations, ketu -- yajñasya ketu-- of Soma Yāga performance. Fern stems are often referred to as "rhizomes". "In botany and dendrology, a rhizome (/ˈraɪzoʊm/, from Ancient Greek: rhízōma "mass of roots",[1] from rhizóō"cause to strike root")[2] is a modified subterranean stem of a plant that is usually found underground, often sending out roots and shoots from its nodes. Rhizomes are also called creeping rootstalks and rootstocks. Rhizomes develop from axillary buds and grow perpendicular to the force of gravity. The rhizome also retains the ability to allow new shoots to grow upwards." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rhizome Lotus rhizome.कर्णिक, कर्णिका f. the pericarp of a lotus MBh. BhP. &c; f. a knot-like tubercle Sus3r.; f. a round protuberance (as at the end of a reed or a tube) Sus3r. Rebus: कर्णिक m. a steersman W. A fern unrolls a young frond. These young fronds become decorative motifs of Indus Script artifacts. The use of rebus method to apply sound values to glyphs is well-attested in contemporary civilizations of Egypt and Sumer. When sound values related to the glyphs of the Indus writing system were identified from the glosses of the linguistic area, a surprising semantic cluster emerged related to homophones. While the glosses directly relatable to the emphatically, unambiguously identifiable glyphs were listed, the corresponding homophones produced a semantic cluster related to metallurgy, minerals, metals, alloys, smithy, smelters, furnace types and forge. The rebus method automatically justified itself as a valid method and helped decode majority of the unambiguously identified glyphs (both pictorial motifs and signs) of the Indus Script writing system. The decoded rebus readings related to the repertoire of mine-workers, metal worker guild and smithy. That a guild was in vogue is inferred from the glyph of a trough shown in front of not only domesticated animals but also wild animals and the homophone for the trough (pātra, pattar) indicates a guild, pattar, guild of goldsmiths.

Who was Ashoka. A critical study

daya dissanayake

We have five Aśokas. i). from the inscriptions, ii). from the Sri Lanka Pali chronicles, iii). from the Sanskrit northern literature, iv). Taranata’s History of Buddhism in India, and v). the real historical Aśoka, who may have been a totally different person, a truly humane ruler, or just another Indian Raja who had diverted his megalomania in a different direction. It has become a near impossible task to see and identify the real Aśoka, through all the legends built around him, and the misinterpretation of his inscriptions. The person in the inscriptions called himself Devānampiya Piyadassi Aśoka rājā. Aśoka may not have been the name used, or by which he was known in his time. He was forgotten or ignored after his death and brought back to life by the Lankan Pali chroniclers about 6 – 7 centuries later, and also by the Northern Buddhist writers. Then he was re-introduced to India by Europeans, like a Trojan horse, to be taken up by the Indians fighting for independence. Aśoka could have been a victim of politico-religious manipulations, from his young days. He could have been manipulated by his ministers and the Saṁgha. He continued to be manipulated by the Brahmins, Buddhists, the Pali chroniclers in Lanka and then in recent times by the British, and by Gandhi, Nehru and the Congress, and by Premadasa in Sri Lanka. This book is an attempt to try to learn who the real Aśoka was, from all available data, and the various interpretations, while posing many more questions for the historians, archaeologists, anthropologists and philosophers.

martti kalda

Dennis Cheatham

A critical look at Ashokan edicts in Buddhist India and their similarities to 19th century propaganda.

National Mission on Education, Institute of Lifelong Learning, University of Delhi

Meera Visvanathan

RELATED PAPERS

Indo Nordic Authors Collective

Dr. Uday Dokras

Thomas Voss

Pratna Samiksha

Susmita Basu Majumdar , shoumita chatterjee

Heritage of Indian History, Culture and Archeology (Festschrift to Dr. M.D. Sampath)

Jeyapriya Rajarajan

Indo Nordic Author's Collective

Syeda Yusra

Indo Nordic Autghor's Collective

Monica L. Smith

Osmund Bopearachchi

FROM LOCAL TO GLOBAL, Prof. A.K. Narain Commemoration Volume, Papers in Asian History and Culture (In Three Volumes), edited by Kamal Sheel, Charles Willemen and Kenneth Zysk, Buddhist World Press Delhi-110 052

Sambhav Choudhary

Srinivasan Kalyanaraman

Asian Perspectives

Namita Sugandhi

Hans Loeschner

RAMESH RAGHU

Uparathana Uduwila

Ranabir Chakravarti

rahul abhishek

Umakant Mishra

Handbook of Ancient Afro-Eurasian Economies Volume 1: Contexts

Mamta Dwivedi

Eloquent Spaces: Meaning and Community in Early Indian Architecture (ed. S. Kaul)

Ancient Asia

Krishnamurthy S. , Sachin Tiwary

Vikas Vaibhav

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- IAS Preparation

- NCERT Notes for UPSC

- NCERT Notes Lion Capital And Sanchi Stupa

Sanchi Stupa - Know About Lion Capital [NCERT Notes For UPSC]

In ancient Indian history, Mauryan dynasty had a significant role. Sanchi Stupa is the finest example of Mauryan sculpture. Learning about Sanchi Stupa is important for IAS Exam from the perspective of Art & Culture segment of the syllabus.

NCERT notes on the topic ‘ Sanchi Stupa & Lion Capital’ are useful for the UPSC preparation. These notes will also be useful for other competitive exams like banking PO, SSC, state civil services exams and so on.

Sanchi Stupa (UPSC Notes):- Download PDF Here

Sanchi Stupa – Lion Capital, Sarnath

- One of the finest examples of Mauryan sculpture.

- Located at Sarnath, near Varanasi. Commissioned by Emperor Ashoka . Built-in 250 BCE.

- Made of polished sandstone. The surface is heavily polished.

- Currently, the pillar is in its original place but the capital is on display at the Sarnath Museum.

- The shaft (now broken into many parts)

- A lotus base bell

- A drum on the base bell with 4 animals proceeding clockwise (abacus)

- Figures of 4 lions

- The crowning part, a large wheel (this is also broken and displayed at the museum)

- The capital was adopted as the National Emblem of India after independence without the crowning wheel and the lotus base.

- The four lions are seated back-to-back on a circular abacus. The figures of the lions are grand and evoke magnificence. They are realistic images and the lions are portrayed as if they are holding their breath. The curly manes of the lions are voluminous. The muscles of the feet are shown stretched indicating the weight of the bodies.

- The abacus has four wheels (chakra) with 24 spokes in all four directions. This is part of the Indian National Flag now.

- The wheel represents Dharmachakra in Buddhism (the wheel of dhamma/dharma). Between every wheel, there are animals carved. They are a bull, a horse, an elephant and a lion. The animals appear as if they are in motion. The abacus is supported by the inverted lotus capital.

Sanchi Stupa

- Sanchi Stupa is a UNESCO world heritage site since 1989. Sanchi is in Madhya Pradesh.

- There are many small stupas here with three mains ones – stupa 1, stupa 2 and stupa 3. Stupa 1 is also called the Great Stupa at Sanchi. It is the most prominent and the oldest and is believed to have the Buddha’s relics.

- It was built by Ashoka in the 3rd century BCE.

- The original structure was made out of bricks. Later on, it was covered with stone, vedica , and the torana (gateway).

- There are four gateways to the stupa with the southern one being built first. The others were later added. The gateways are adorned with beautiful sculptures and carvings. Each torana consists of two vertical pillars and three horizontal bars on top. The bars contain exquisite carvings on front and back. They contain images of shalbhanjikas – lady holding the branch of a tree. Stories from the Jataka tales are carved here.

- The structure has a lower and upper pradakshinapatha or circumambulatory path. The upper pradakshinapatha is unique to this stupa.

- On the southern side of the stupa, the Ashokan Lion Capital pillar is found with inscriptions on it.

- The hemispherical dome of the stupa is called the anda . It contains the relics of the Buddha.

- The harmika is a square railing on top of the dome/mound.

- The chhatra is an umbrella on top of the harmika. There is a sandstone pillar in the site on which Ashoka’s Schism Edict is inscribed.

- The original brick dome was expanded into double its size during the reign of the Shunga dynasty with stone slabs covering the original dome.

Also, read the articles linked in the table below:

Frequently Asked Questions on Sanchi Stupa and Lion Capital

Q 1. what are the different components of the lion capital at sarnath.

Ans. There are five components of the Lion Capital in Sarnath:

- A lotus base

- Abacus with sculptures of a bull, a horse, a lion and an elephant

- 4 Lion figures

- The crowning part

Q 2. What is the significance of Sanchi Stupa?

Related Links:

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

IAS 2024 - Your dream can come true!

Download the ultimate guide to upsc cse preparation, register with byju's & download free pdfs, register with byju's & watch live videos.

Win up to 100% Scholarship

- UPSC Online

- UPSC offline and Hybrid

- UPSC Optional Coaching

- UPPCS Online

- BPSC Online

- MPSC Online

- MPPSC Online

- WBPSC Online

- OPSC Online

- UPPCS Offline Coaching

- BPSC Offline Coaching

- UPSC Test Series

- State PSC Test Series

- DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS

- SUBJECT WISE CURRENT AFFAIRS

- DAILY EDITORIAL ANALYSIS

- DAILY CURRENT AFFAIRS QUIZ

- Daily Prelims(MCQs) Practice

- Daily Mains Answer Writing

- Free Resources

- Offline Centers

- NCERT Notes

- UDAAN Notes

- UPSC Syllabus

- UPSC Prelims PYQs

- UPSC Mains PYQs

- Prelims Preparation

NCERT NOTES

Elevate your upsc preparation with ncert notes – because every word matters on your journey to success..

- Indian Economy

- Physical Geography

- Indian Society

- Science & Tech

- Human Geography

- Art & Culture

Art of Mauryan Period : Pillars, Lion capital, Yaksha and Yakshini

Emergence of Mauryan Power: A Cultural Shift in the 6th Century BCE Gangetic Valley

Around the 6th century BCE, the Gangetic Valley buzzed with fresh ideas. New religions like Buddhism and Jainism sprang up, challenging traditional Hindu beliefs. Meanwhile, Magadha grew as a powerhouse, paving the way for the Mauryas.

Pillars: Sculpting the Past by Exploring the Art of Mauryan Period

- Structure: Pillars are vertical structural members in architecture and building construction, insert keyword art of mauryan period in paragraph.

- Single Unit: They can be made of a single piece of stone or wood, or built up of units, such as bricks.

- Material: Pillars, usually made of chunar sandstone, are a symbol of the state.

- It assumed great significance throughout the entire Mauryan Empire.

- Objectives: To propagate the Buddhist ideology and court orders in the entire Mauryan empire, the art of Mauryan period manifested in the construction of pillars that stood as monumental symbols of both structural ingenuity and ideological dissemination.

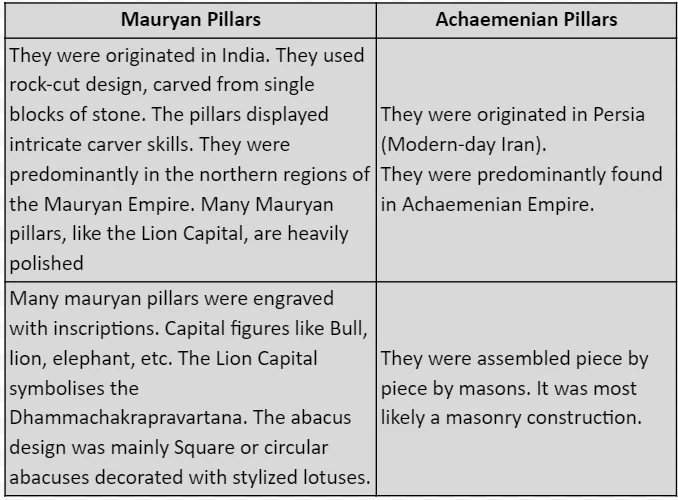

Difference between Mauryan and Achamenian

- The contrast in pillar construction between the Mauryan and Achaemenian periods reveals distinctive features in the art of Mauryan period.

- Features: All the figures on the pillars were vigorously carved, standing proudly on either square or circular abacuses adorned with stylized lotuses.

- Renowned examples of such pillars have been unearthed at locations including Basarah-Bakhira, Lauriya-Nandangarh in Bihar, and Sankisa and Sarnath in Uttar Pradesh.

The Sarnath Lion Capital: A Pinnacle of Art in the Mauryan Period and National Emblem

The Mauryan pillar capital found at Sarnath, Varanasi popularly known as the Lion Capital is the finest example of Mauryan architecture.

- It is also our national emblem.

- It was commissioned by Ashoka, it commemorates Buddha’s first sermon, known as Dhammachakrapravartana.

- Components of the Capital

- This wheel is now damaged and showcased in the site museum at Sarnath.

- Currently, the lion capital is housed in the archaeological museum at Sarnath.

- They have strong facial features and lifelike details.

- They have a heavily polished surface, which is typical of Mauryan art.

- They have curly, protruding manes and well-defined muscles.

Comparison and Legacy

- The lion-capital-pillar motif persisted in subsequent periods, showcasing its lasting influence.

- A significant number of these statues, especially those of Yakshas and Yakhinis, have been discovered in places like Patna, Vidisha, and Mathura.

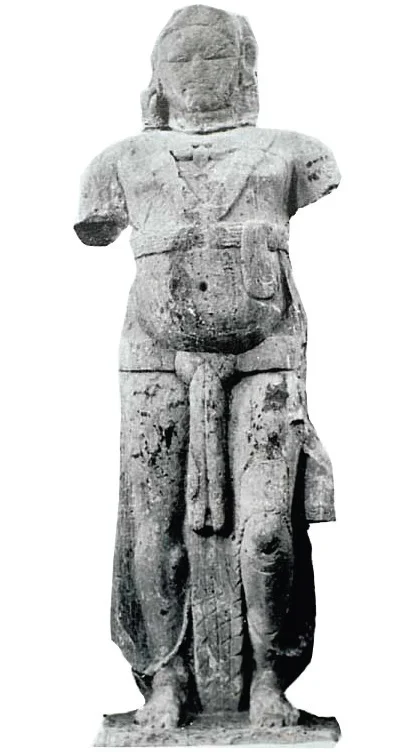

Yaksha and Yakshini Sculpture and its influence

- Region: Large statues of Yakshas and Yakhinis are found in many places like Patna, Vidisha and Mathura.

- Position: These monumental images are mostly in the standing position.

- Worship: Yaksha and yakshini sculptures demonstrate worship’s influence in Buddhist and Jaina monuments.

- One of the finest examples is a Yakshi figure from Didarganj, Patna , which is tall and well-built.

- It shows sensitivity towards depicting the human physique. The image has a polished surface.

Mauryan Masterpieces: The Artistic Splendor of the Didarganj Yakshini

- The statue is showcased in the Patna Museum.

- It is crafted from sandstone, boasts a polished surface and embodies a free-standing sculpture in the round.

Artistic Features

- The face features round, plump cheeks with sharp eyes, nose, and lips.

- Necklace beads hang gracefully to the belly, and the garment’s tight fit accentuates a protruding belly.

The Detailed Craftsmanship of Mauryans Period Bodily Representations

- Neatly Tied Hair: The hairs are neatly tied in a knot.

- Bareback and Drapery Contrast: The bareback contrasts with the drapery covering the legs.

- Continuity in Design: The chauri’s incised lines continue onto the statue’s back, showcasing continuity in design.

- Semi-Transparent Effect: The lower garment clings to the legs, producing a semi-transparent effect.

- A thick bell-ornaments ornament embellishes her feet, showcasing the ornate features commonly found in the art of Mauryan period.

UPDATED :

Recommended For You

Latest comments, the most learning platform.

Learn From India's Best Faculty

Our Courses

Our initiatives, beginner’s roadmap, quick links.

PW-Only IAS came together specifically to carry their individual visions in a mission mode. Infusing affordability with quality and building a team where maximum members represent their experiences of Mains and Interview Stage and hence, their reliability to better understand and solve student issues.

Subscribe our Newsletter

Sign up now for our exclusive newsletter and be the first to know about our latest Initiatives, Quality Content, and much more.

Contact Details

G-Floor,4-B Pusha Road, New Delhi, 110060

- +91 9920613613

- [email protected]

Download Our App

Biginner's roadmap, suscribe now form, fill the required details to get early access of quality content..

Join Us Now

(Promise! We Will Not Spam You.)

CURRENT AF.

<div class="new-fform">

Select centre Online Mode Hybrid Mode PWonlyIAS Delhi (ORN) PWonlyIAS Delhi (MN) PWonlyIAS Lucknow PWonlyIAS Patna Other

Select course UPSC Online PSC ONline UPSC + PSC ONLINE UPSC Offline PSC Offline UPSC+PSC Offline UPSC Hybrid PSC Hybrid UPSC+PSC Hybrid Other

</div>

Lion Capital, Ashokan Pillar at Sarnath

Lion Capital, Ashokan Pillar at Sarnath, c. 250 B.C.E., polished sandstone, 210 x 283 cm, Sarnath Museum, India (photo: AS Mysore for Vincent Arthur Smith, not in copyright – pre Independence princely state publication)

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

About Lion Capital & Sanchi Stupa in Details

Sanchi Stupa & Lion Capital are prime examples of Mauryan architecture. Learn the significance of Lion Capital and its adoption as Indian emblem. For UPSC 2023 preparation.

Table of Contents

Lion Capital & Sanchi Stupa

Sanchi’s stupa is one of India’s very first and most important Buddhist sites. And some of the country’s oldest stone buildings can be found in this location. The British captain Edward Fell wrote one of the earliest accounts of the stupa of Sanchi in 1819. More specifically, it was claimed that Sir John Marshall’rediscovered’ the location 93 years after it had previously been “lost.” and afterwards another seven before it was changed to its present state. For UPSC preparation, the NCERT notes on the subject of “that is Sanchi Stupa & Lion Capital” are helpful.

Lion Capital & Sanchi Stupa Background

Beautiful caves and inscriptions illustrate Indian architecture from the Mauryan era, which began in the third century BCE, through the later mediaeval era’s fall, which began around the eleventh century CE. The Mahastupa, or Great Stupa, is rumoured to be the complex’s claim to fame. The Ashokan pillar features beautiful toran gateways and inscribed architecture.

The torans and the fencing are claimed to be designed in a manner that is similar to the bamboo craftspeople in the neighbourhood. If one pays close attention to the fencing around the stupa, it is possible to infer that the torans’ design is evocative of bamboo craft and that they are connected.

The Sanchi Stupa

The Mauryan dynasty played a very important part in the history of ancient India. The best specimen of Mauryan sculpture is the stupa in Sanchi. From the perspective of the Art & Culture section of the syllabus, understanding the stupa of Sanchi is crucial for the IAS.

We can assert with some interest that Lord Buddha never went to Sanchi. Neither did foreign tourists like Hiuen Tsang. He was the one who meticulously recorded the sacred Buddhist route in India. However, he hardly ever made reference to Sanchi in his writings. Marshall wrote about Sanchi, which was not as venerated as other Buddhist pilgrimage destinations in India, in his 1938 book The Monuments of Sanchi.

According to academics like Sir Alfred A Foucher, the iconic representations of Buddha at the Sanchi, such as the Bodhi tree, a horse without a rider, an empty throne, etc., are the result of Graeco-Buddhist architectural interaction. Sanchi’s lion capital is comparable to the one at Sarnath. The monument’s representation of Sanchi as an abacus rather than a chakra is the fundamental distinction between the two.

However, the Sanchi Stupa’s impact on our country’s mentality extends beyond the lion’s capital. Several contemporary structures were designed as a result of it, with Rashtrapati Bhavan serving as the principal example. Lord Charles Hardinge wanted the renowned architect Edwin Lutyens to add a symbol of historical Indian architecture into the structure, and he designed the colonnade to have a Sanchi dome and balustrade railing.

The Lion Capital of India

In India, the Sanchi stupa is a popular tourist destination. According to reports, it is located in the Madhya Pradesh state of Sanchi in the Raisen district. The Great Stupa of Stupa, which was initially ordered by the monarch Ashoka, is the oldest stone building in the nation of India. Sanchi’s stupa is situated atop a hill that rises to a height of 91 metres (298.48 feet). In 1989, UNESCO designated the Sanchi stupa as a World Heritage monument.

For Buddhist travellers to India, the Sanchi stupa is a popular destination. The stupa at Sanchi, the oldest stone structure in India, is very magnificent. It was built on a commission from Ashoka the Great, who lived in the third century BCE.

The stupa of Sanchi, which was formerly known by the names Kakanaya, Kakanadabota, and Bota-Sri Parvata, is notable for also containing exquisite copies of Buddhist art and architecture. The early Mauryan period, or the third century BC to the twelfth century AD, is covered by this. The stupa at Sanchi is known as Stupas throughout the world. Other attractions include temples, monasteries, and a plethora of sculpture, as well as monolithic Asokan pillars.

Sharing is caring!

Lion Capital & Sanchi Stupa FAQs

What is lion capital in sanchi stupa.

There are four lions. A pillar which is of finely polished sandstone, there is one of the Pillars of Ashoka. It was also said to be erected on the side of the main Torana gateway at Sanchi. The capital, which is bell-shaped, consists of four lions which probably supported a law of the wheel.

Why was the Lion Capital adopted as the national emblem?

The national emblem is an adaptation of the Lion Capital, originally found atop the Ashoka Column at Sarnath, established in 250 BC. The capital has four Asiatic lions—symbolising power, courage, pride and confidence—seated on a circular abacus.

Who built the Lion Capital of India?

The Lion capital comes from a column at Sarnath in Uttar Pradesh, built by Ashoka, the Mauryan king who flourished in the third century BC.

What is the four lion capital at Sanchi?

The Sanchi Capital refers to a polished, monolithic, sandstone Ashokan pillar and capital, surmounted by four lions with their backs to each other, found at the Buddhist site of Sanchi, in modern-day Madhya Pradesh.

Which city is known as Lion Capital?

Sarnath is known as Lion Capital.

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- UPSC Online Coaching

- UPSC Exam 2024

- UPSC Syllabus 2024

- UPSC Prelims Syllabus 2024

- UPSC Mains Syllabus 2024

- UPSC Exam Pattern 2024

- UPSC Age Limit 2024

- UPSC Calendar 2024

- UPSC Syllabus in Hindi

- UPSC Full Form

Recent Posts

- UPPSC Exam 2024

- UPPSC Calendar

- UPPSC Syllabus 2024

- UPPSC Exam Pattern 2024

- UPPSC Application Form 2024

- UPPSC Eligibility Criteria 2024

- UPPSC Admit card 2024

- UPPSC Salary And Posts

- UPPSC Cut Off

- UPPSC Previous Year Paper

BPSC Exam 2024

- BPSC 70th Notification

- BPSC 69th Exam Analysis

- BPSC Admit Card

- BPSC Syllabus

- BPSC Exam Pattern

- BPSC Cut Off

- BPSC Question Papers

IB ACIO Exam

- IB ACIO Salary

- IB ACIO Syllabus

CSIR SO ASO Exam

- CSIR SO ASO Exam 2024

- CSIR SO ASO Result 2024

- CSIR SO ASO Exam Date

- CSIR SO ASO Question Paper

- CSIR SO ASO Answer key 2024

- CSIR SO ASO Exam Date 2024

- CSIR SO ASO Syllabus 2024

Study Material Categories

- Daily The Hindu Analysis

- Daily Practice Quiz for Prelims

- Daily Answer Writing

- Daily Current Affairs

- Indian Polity

- Environment and Ecology

- Art and Culture

- General Knowledge

- Biographies

IMPORTANT EXAMS

- Terms & Conditions

- Return & Refund Policy

- Privacy Policy

Essay on National Symbols of India

Students are often asked to write an essay on National Symbols of India in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on National Symbols of India

Introduction.

India, a diverse and culturally rich country, has several national symbols. These symbols represent the country’s identity and heritage.

National Flag

The Indian National Flag, also known as the ‘Tricolor’, has three equal horizontal bands of saffron, white, and green, with a blue Ashoka Chakra in the middle.

National Emblem

The National Emblem of India is derived from the Sarnath Lion Capital of Ashoka. It signifies power, courage, and confidence.

National Anthem and Song

The National Anthem is ‘Jana Gana Mana’ and the National Song is ‘Vande Mataram’. Both songs evoke a sense of patriotism.

National Animal, Bird, and Flower

The National Animal is the Bengal Tiger, the National Bird is the Indian Peafowl, and the National Flower is the Lotus. They symbolize strength, grace, and purity respectively.

Also check:

- 10 Lines on National Symbols of India

- Speech on National Symbols of India

250 Words Essay on National Symbols of India

India, a country with rich cultural heritage and history, is home to numerous national symbols that represent its unique identity. These symbols, ranging from the national flag to the national animal, encapsulate the essence of the nation, reflecting its diversity, values, and aspirations.

The Indian National Flag, often referred to as the ‘Tricolour’, is a horizontal tricolour of saffron, white, and green, with a blue Ashoka Chakra in the center. The saffron signifies courage and sacrifice, white stands for peace and truth, while green represents prosperity. The Ashoka Chakra, a 24-spoke wheel, symbolizes the eternal wheel of law or Dharma.

The National Emblem of India is an adaptation of the Lion Capital of Ashoka at Sarnath. It comprises four Asiatic lions standing back to back, symbolizing power, courage, pride, and confidence. The emblem also features the Ashoka Chakra and a bull, a galloping horse, and a lion separated by intervening wheels.

National Animal and Bird

The Royal Bengal Tiger, known for its strength, agility, and grace, is India’s national animal, symbolizing the country’s rich wildlife and biodiversity. The Indian Peafowl, or Peacock, is the national bird, chosen for its rich religious and legendary involvement in Indian traditions.

In essence, the national symbols of India are not just mere representations but are imbued with profound philosophical and cultural significance. They serve as a reminder of the country’s vibrant history, diverse culture, and commitment to uphold the principles of justice, liberty, equality, and fraternity.

500 Words Essay on National Symbols of India

India, a diverse nation with a rich cultural heritage, is symbolized by several national symbols. These symbols, embodying the essence of India, play a crucial role in representing the country’s identity and unity. They are not merely symbols; they carry a profound meaning and historical significance.

The National Flag

India’s national flag, also known as the Tricolor or ‘Tiranga’, is a symbol of the country’s freedom. It consists of three equal horizontal bands – saffron at the top, signifying courage and sacrifice; white in the middle, representing peace and truth; and green at the bottom, symbolizing fertility, growth, and auspiciousness. The Ashoka Chakra, a 24-spoke wheel in navy blue at the center, represents the eternal wheel of law.

The National Emblem

The National Emblem of India is derived from the Lion Capital of Ashoka at Sarnath. It comprises four Asiatic lions standing back to back, symbolizing power, courage, pride, and confidence. Only three lions are visible from any angle, suggesting the hidden potential within us. The emblem also includes a wheel (Dharma Chakra), a bull, and a galloping horse, symbolizing the dynamic and steadfast spirit of India.

The National Anthem and Song

The National Anthem, “Jana Gana Mana,” written by Rabindranath Tagore, is a hymn to the motherland, reflecting India’s diversity and unity. The National Song, “Vande Mataram,” from Bankim Chandra Chatterjee’s novel Anandamath, played a vital role in India’s struggle for independence. Both these songs evoke a sense of patriotism and national pride.

The National Animal, Bird, and Flower

The Royal Bengal Tiger, the national animal, symbolizes India’s wildlife wealth. The national bird, the Indian Peacock, known for its grace, joy, beauty, and love, is a representation of India’s rich avian biodiversity. The Lotus, India’s national flower, signifies purity, spirituality, and enlightenment, reflecting the core values of Indian philosophy.

The National Tree and Fruit

The Banyan tree, India’s national tree, symbolizes immortality, epitomizing the country’s strength and longevity. The Mango, the national fruit, represents the tropical climate of India. Both are deeply rooted in Indian culture and folklore, and they signify the country’s lush natural bounty.

India’s national symbols are not merely physical entities; they are the embodiment of the country’s ethos, diversity, and unity. They represent the historical legacy, cultural richness, biodiversity, and philosophical depth of this ancient civilization. These symbols, deeply ingrained in the hearts of Indians, continually inspire them to uphold the values of courage, truth, peace, and harmony. Understanding the significance of these symbols can help one appreciate the essence of India’s vibrant heritage and the principles that the nation holds dear.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on My Ideal India

- Essay on Monuments of India

- Essay on Monsoon in India

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Share full article

Stephen Hiltner/The New York Times

The sculpted facade of a 2,000-year-old tomb glows in the late-afternoon sun at Hegra, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Crowds of Muslim pilgrims gather outside the Prophet’s Mosque in Medina.

Camels march through the desert on the outskirts of the Empty Quarter, the world’s largest sand sea.

For many years these Saudi Arabian scenes, including the lively open-air markets in Jeddah, were off limits to most travelers.

But not anymore. As it undergoes a profound transformation, Saudi Arabia is spending lavishly to lure tourists with its luxe new resorts ...

... its rich cultural heritage ...

... and its sublime natural beauty.

Can the Saudi government persuade would-be visitors to look past — or reconsider — its longstanding associations with religious extremism, ultraconservatism and human rights abuses?

Will the kingdom’s $800 billion bet on tourism pay off?

Supported by

Surprising, Unsettling, Surreal: Roaming Through Saudi Arabia

To witness the kingdom’s profound transformation and assess its ambitious tourism projects, a Times journalist spent a month on the road there. Here’s what he saw.

By Stephen Hiltner

An editor and photojournalist for the Travel section, Stephen Hiltner drove 5,200 miles and visited all 13 of Saudi Arabia’s provinces while reporting and shooting this story.

Wandering alone along the southern fringes of Saudi Arabia’s mountainous Asir Province, some eight miles from the Yemeni border, in a nondescript town with a prominent sculpture of a rifle balanced on an ornately painted plinth, I met a man, Nawab Khan, who was building a palace out of mud.

Actually, he was rebuilding the structure, restoring it. And when I came across him, he hadn’t yet begun his work for the day; he was seated on the side of the road beneath its red-and-white windows — cross-legged, on a rug, leaning over a pot of tea and a bowl of dates.

Two weeks earlier, on the far side of the country, a fellow traveler had pointed at a map and described the crumbling buildings here, in Dhahran al-Janub, arranged in a colorful open-air museum. Finding myself nearby, I’d detoured to have a look — and there was Mr. Khan, at first looking at me curiously and then waving me over to join him. Sensing my interest in the cluster of irregular towers, he stood up, produced a large key ring and began opening a series of padlocks. When he vanished through a doorway, I followed him into a shadowy stairwell.

This, of course, was my mother’s worst nightmare: Traveling solo, I’d been coaxed by a stranger into an unlit building in a remote Saudi village, within a volatile border area that the U.S. Department of State advises Americans to stay away from .

By now, though, more than halfway through a 5,200-mile road trip, I trusted Mr. Khan’s enthusiasm as a genuine expression of pride, not a ploy. All across Saudi Arabia, I’d seen countless projects being built, from simple museums to high-end resorts. These were the early fruits of an $800 billion investment in the travel sector, itself part of a much larger effort, Vision 2030 , to remake the kingdom and reduce its economic dependence on oil.

But I’d begun to see the building projects as something else, too: the striving of a country — long shrouded to most Westerners — to be seen, reconsidered, accepted. And with its doors suddenly flung open and the pandemic behind us, visitors like me were finally beginning to witness this new Saudi Arabia, much to Mr. Khan’s and all the other builders’ delight.

Few countries present as complicated a prospect for travelers as Saudi Arabia.

Long associated with Islamic extremism, human rights abuses and the oppression of women, the kingdom has made strides in recent years to refashion its society and its reputation abroad.

The infamous religious police, which upheld codes of conduct based on an ultraconservative interpretation of Islam, were stripped of their power. Public concerts, once banned, are now ubiquitous. Women have been granted new rights — including the freedom to drive and to travel without permission from a male guardian — and are no longer required to wear floor-length robes in public or to cover their hair.

These changes are part of a broad set of strategies to diversify the kingdom’s economy, elevate its status in the world and soften its image — the last of which is a tall order for a government that has killed a newspaper columnist , kidnapped and tortured dissidents , precipitated a humanitarian crisis in Yemen and imprisoned people for supporting gay rights , among a number of other recent abuses .

Central to the transformations led by 38-year-old Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the kingdom’s de facto ruler, is a major push for international visitors. It represents a sea change in a country that, until 2019, issued no nonreligious tourist visas and instead catered almost exclusively to Muslim pilgrims visiting Mecca and Medina, Islam’s two holiest cities. In February, by contrast, my tourist e-visa was approved online in minutes.

Saudi Arabia has already transformed one of its premier destinations — Al-Ula, with its UNESCO-listed Nabatean tombs — from a neglected collection of archaeological sites into a lavish retreat with a bevy of activities on offer, including guided tours, wellness festivals, design exhibitions and hot air balloon rides.

Another project will create a vast array of luxury resorts on or near the Red Sea.

Still more projects include the development of Diriyah , the birthplace of the first Saudi state; the preservation and development of the coastal city of Jeddah ; an offshore theme park called the Rig ; and Neom , the futuristic city that has garnered the lion’s share of attention.

All told, the country is hoping to draw 70 million international tourists per year by 2030, with tourism contributing 10 percent of its gross domestic product. (In 2023, the country logged 27 million international tourists, according to government figures , with tourism contributing about 4 percent of G.D.P.)

At-Turaif, a UNESCO World Heritage site, was the birthplace of the kingdom of Saudi Arabia. It is now the centerpiece of the $63 billion Diriyah project, a new center of culture just outside Riyadh.

Nujuma, a Ritz-Carlton Reserve on a remote island in the Red Sea, opened in late May. (A one-bedroom villa costs about $2,500 per night, excluding taxes and fees.) It is one of 50 properties scheduled to open in the area by 2030.

The preservation and development of Jeddah, a coastal city famous for its historic district built largely from blocks of coral, comes with a price tag of some $20 billion.

Al-Ula is a cornerstone of Saudi Arabia’s tourism ambitions. Part of the city’s Old Town, long crumbling in neglect, has now been painstakingly restored.

To get a sense of these projects and the changes unfolding in Saudi society, I spent a month exploring the kingdom by car. I traveled alone, without a fixer, driver or translator. Per New York Times ethics guidelines, I declined the government’s many offers of discounts and complimentary services.

Much of the time I felt I’d been tossed the keys to the kingdom. But there were moments, too, when I faced a more complicated reality, one epitomized by a road sign that forced me to abruptly exit the highway some 15 miles from the center of Mecca. “Obligatory for Non Muslims,” it read, pointing to the offramp.

To me, the sign broadcast the lines being drawn to compartmentalize the country, which is now marketing itself to two sets of travelers with increasingly divergent — and sometimes contradictory — expectations: luxury tourists at ease with bikinis and cocktails, and pilgrims prepared for modesty and strict religious adherence. It’s hard to know whether the kingdom can satisfy both without antagonizing either.

My trip began in Jeddah, where, after spending two days exploring its historic district, I rented a car and drove eight hours north to Al-Ula, a benchmark for the new Saudi tourism initiatives.

Saudi Arabia

Reporter’s route

Dhahran al-Janub

Wadi al-Disah

Red Sea Resort

The name Al-Ula refers to both a small city and a broader region packed with attractions: Hegra , the kingdom’s first UNESCO World Heritage site and its biggest archaeological draw, is a 30-minute drive north of Old Town, a maze of crumbling mud-brick buildings now partly restored. Between the two, and fanning out to the east and west, are several other archaeological sites, as well as a smattering of resorts, event spaces and adventure outfitters. Farther northeast, beyond Hegra, is the Sharaan Nature Reserve , a vast protected zone used for conservation efforts.

My first priority during my five-day stay in Al-Ula was a visit to Hegra.

Like Petra , its better-known counterpart in Jordan, Hegra was built by the Nabateans, an ancient people who flourished 2,000 years ago. The site contains more than 100 tombs that were carved from solid rock, their entrances adorned with embellishments. Most impressive among them, set apart and standing some 70 feet tall, is a tomb colloquially called the Lonely Castle.

Not long ago, visitors could hire private guides and wander the area on foot, climbing in and out of — and no doubt damaging — the many tombs. Not anymore: I boarded an air-conditioned tour bus and zipped past most of them, stopping at just four locations.

At the penultimate stop, we exited the bus and trudged several hundred feet along a sandy path to the front of the Lonely Castle. Even in the late afternoon, the heat was stifling. I craned my neck to take in the details of the sculpted facade, which emerged like a mirage from one side of a massive boulder: its four pilasters, the rough chisel marks near the bottom, its characteristic five-stepped crown. Ten minutes evaporated, and I turned to find my group being shepherded back onto the bus. I jogged through the sand to catch up.

A few miles north of Hegra, I hopped in the back of a Toyota Land Cruiser — accompanied by an Italian graduate student and his mother — for a drive through the sandy expanse of the Sharaan Nature Reserve.

The scenery was sublime: Slipping through a narrow slot canyon, we emerged into a vast, open desert plain, then settled into a wide valley enclosed by an amphitheater of cliffs. Occasionally our guide stopped and led us on short hikes to petroglyphs, some pockmarked by bullet holes, or to lush fields of wildflowers, where he plucked edible greens and invited us to sample their lemony tang.

Gabriele Morelli, the graduate student, had first come to Al-Ula a few years ago — a different era, he said, given how quickly the place had transformed. He described a version that no longer exists, rife with cheap accommodation, lax rules and a free-for-all sensibility.

Some of the changes, of course, have been necessary to protect delicate ecosystems and archaeological sites from ever-growing crowds. But several people I met in Al-Ula — Saudis and foreigners alike — quietly lamented the extent of the high-end development and the steady erosion of affordability. Many of the new offerings, like the Banyan Tree resort, they pointed out, are luxury destinations that cater to wealthy travelers.

These hushed criticisms were among my early lessons on how difficult it can be to gauge the way Saudis feel about the pace and the pervasiveness of the transformations reshaping their society.

I got a taste of Al-Ula’s exclusivity — and of the uncanniness that occasionally surfaced throughout my trip — at a Lauryn Hill concert in an event space called Maraya . To reach the hall, I passed through a security gate, where an attendant scanned my e-ticket and directed me two miles up a winding road into the heart of the Ashar Valley, home to several high-end restaurants and resorts.

Rounding the final bend, I felt as if I’d stumbled into a computer-generated image: Ant-size humans were dwarfed by a reflective structure that both asserted itself and blended into the landscape. Inside, waiters served hors d’oeuvres and brightly colored mocktails to a chic young crowd.

The surreality peaked when, midway through the show, I left my plush seat to join some concertgoers near the stage — only to turn and see John Bolton, former President Donald J. Trump’s national security adviser, seated in the front row.

Where else, I wondered, could I attend a rap concert in the middle of the desert with a longtime fixture of the Republican Party — amid a crowd that cheered when Ms. Hill mentioned Palestine — but this strange new corner of Saudi Arabia?

The mirrored facade at Maraya, a vast event space in Al-Ula, warps and reflects the surrounding desert landscape.

The building is in some ways a precursor to the kingdom’s most ambitious architectural design: the project at Neom called the Line, a 106-mile linear city that will also feature a mirrored surface.

Lauryn Hill performing in front of a large crowd at Maraya.

After Al-Ula, I drove to another of the kingdom’s extravagant schemes: the Red Sea project, billed as the “world’s most ambitious regenerative tourism destination.” After weaving through a morass of construction-related traffic, I boarded a yacht — alongside a merry band of Saudi influencers — and was piloted some 15 miles to a remote island, where I disembarked in a world of unqualified opulence at the St. Regis Red Sea Resort .

I was chauffeured around in an electric golf cart — past 43 beachside “dune” villas and onto two long boardwalks that connect the rest of the resort to 47 “coral” villas, built on stilts over shallow turquoise water. Along the way, I listened to Lucas Julien-Vauzelle, an executive assistant manager, wax poetic about sustainability. “We take it to the next level,” he said, before rattling off a list of facts and figures: 100 percent renewable energy, a solar-powered 5G network , plans to enhance biologically diverse habitats.

By 2030, he said, the Red Sea project will offer 50 hotels across its island and inland sites. Citing the Maldives, he mentioned the kingdom’s plans to claim a share of the same high-end market.

Another prediction came by way of Keith Thornton, the director of restaurants, who said he expects the resort to legally serve alcohol by the end of the year. (While a liquor store for non-Muslim diplomats recently opened in Riyadh, the Saudi government has made no indication that it plans to reconsider its broader prohibition of alcohol.)

The hotel was undeniably impressive. But there’s an inescapable irony to a lavish resort built at unfathomable expense in the middle of the sea — with guests ferried out by chartered boat and seaplane — that flaunts its aspirations for sustainability.

Toward the end of my several-hour visit, I learned that every piece of vegetation, including 646 palm trees, had been transplanted from an off-site nursery. Later, reviewing historical satellite images, I found visual evidence that the island — described to me as pristine — had been dramatically fortified and, in the process, largely remade. Its footprint had also been significantly altered. It was, in a sense, an artificial island built where a smaller natural island once stood.

Something else struck me, too: The place was nearly empty, save for the staff and the Saudi influencers. Granted, the resort had just opened the month before — but the same was true at the nearby Six Senses Southern Dunes , an inland Red Sea resort that opened in November. Fredrik Blomqvist, the general manager there, told me that its isolated location in a serene expanse of desert — part of its appeal — also presented a challenge in drawing customers. “The biggest thing,” he said, “is to get the message out that the country is open.”

Since the country began issuing tourist visas, influencers have been documenting their experiences in places like Jeddah and Al-Ula, their trips often paid for by the Saudi government. Their breezy content contributes to the impression that the kingdom is awaiting discovery by foreign visitors with out-of-date prejudices. To an extent, for a certain segment of tourists, that’s true.

For many travelers, though, the depiction of the kingdom as an uncomplicated getaway could be dangerously misleading.

Speech in Saudi Arabia is strictly limited; dissent is not tolerated — nor is the open practice of any religion other than the government’s interpretation of Islam. In its travel advisory , the U.S. Department of State warns that “social media commentary — including past comments — which Saudi authorities may deem critical, offensive, or disruptive to public order, could lead to arrest.” Punishment for Saudi nationals has been far worse: In 2023, a retired teacher was sentenced to death after he criticized the ruling family via anonymous accounts. As of late 2023, he remained in prison.

Other restrictions are harder to parse. L.G.B.T.Q. travelers are officially welcome in the kingdom but face a conundrum: They might face arrest or other criminal penalties for openly expressing their sexual orientation or gender identity. As recently as 2021, an independent U.S. federal agency included Saudi Arabia on a list of countries where same-sex relationships are punishable by death , noting that “the government has not sought this penalty in recent years.”

When asked how he would convince a same-sex couple that it was safe to visit, Jerry Inzerillo, a native New Yorker and the group chief executive of Diriyah, said: “We don’t ask you any questions when you come into the country or when you leave.”

“Maybe that’s not conclusive enough,” he added, “but a lot of people have come.”

Female travelers might also face difficulties, since advancements in women’s rights are not equally distributed throughout the kingdom.

The changes were more visible in big cities and tourist centers. Ghydda Tariq, an assistant marketing manager in Al-Ula, described how new professional opportunities had emerged for her in recent years. Maysoon, a young woman I met in Jeddah, made extra money by occasionally driving for Uber. Haneen Alqadi, an employee at the St. Regis Red Sea, described how women there are free to wear bikinis without fear of repercussions.

Outside such places, though, I sometimes went for days without seeing more than a handful of women, invariably wearing niqabs, let alone seeing them engaged in public life or tourism. My photographs reflect that imbalance.

As an easily identifiable Western man, I moved through the country with an array of advantages: the kindness and cheery curiosity of strangers, the ease of passage at military checkpoints, and the freedom to interact with a male-dominated society at markets, museums, parks, restaurants, cafes. Not all travelers could expect the same treatment.

Roaming in the far north and south, I often found the earlier version of the kingdom — with lax rules and less development — that had been described to me in Al-Ula.

I trekked to the northern city of Sakaka to see an archaeological site promoted as the Stonehenge of Saudi Arabia: a set of monoliths called the Rajajil Columns thought to have been erected some 6,000 years ago but about which little is definitively known.