- Pollfish School

- Market Research

- Survey Guides

- Get started

What is a Focus Group and How to Use it in Your Market Research

Chances are, you’ve come across focus groups if you’ve looked into market research or other forms of research.

The term focus group is often used as one of the key methods to gather qualitative research , in the market research sphere. Although not quite an interview, this hands-on approach spurs discussions between research participants, which have the potential to go into great depth on a subject of study.

As such, using this technique allows businesses to gain critical insights into their target market, along with all of its segments.

These insights help you hone in on your marketing, branding, advertising and other business processes.

Focus groups can be conducted with other research methods , such as survey research and more.

That’s why you ought to familiarize yourself with this type of research technique. Luckily, this lengthy guide goes into the weeds of this form of research , allowing you to gain an exhaustive understanding and decide whether you should carry out this kind of research method.

This thorough guide explains what a focus group is, how to use it, how it works, its advantages and shortcomings, how it ranks against survey research and more.

Table of Contents: What is a Focus Group and How to Use it in Your Market Research

The role of the moderator, focus group size, the focus group approach, participant discussions, focus group participants, post-research document of findings.

- Data Democratization in Post-Focus Group Research

How long does a focus group last?

The environment of the study, the types of questions used in focus groups, when to use a focus group, how online surveys are superior.

- Benefits That Are Second to None

Reach the Masses and Conduct Quantitative Research

Quantitative + qualitative data = a complete market research experience, no need to worry about recruitment, granular respondent targeting, anonymity, privacy and no social pressures, focus groups vs. an online survey platform: the verdict, defining focus groups.

Let’s begin with the heart of the matter: what is a focus group ? A focus group is a small group of people selected based on their specific shared characteristics, to take part in a discussion for market research , or other types of research .

Focus groups are a kind of primary research . Unlike market research software , which is one of the most popular tools for conducting research in the present day, a focus group does not take place digitally—not before Covid, that is . Now, many events, whether they are research-related or otherwise, take place via online meetings.

At any rate, focus groups occur with all members in one conjoint session , whether it’s in-person or over the internet. Researchers can opt to include a single or multiple focus group sessions, should they require further studies on the same topic or group of participants.

Focus groups are one of the main techniques of qualitative research , which delves into a wide variety of phenomena. These include:

- Motivations

- Reasoning behind actions

- Sentiments

All of these aspects and topics of discussion can focus on the participants about various stimuli, such as current events, past events, plans, fears, culture, etc.

Unlike quantitative data, which works to find the “what” and generate statistics, qualitative data aims at understanding a topic in greater depth.

Focus groups are composed of a small number of people who take part in a studied conversation alongside a moderator. The moderator is one of the main researchers assigned to this kind of study.

The role of the moderator is to ask questions, manage the discussion, make sure everyone speaks up and take notes on the discourse, which are later used to analyze it . Essentially, the moderator is a kind of host in this scenario.

Their role is multi-pronged , as they wear different hats in the study. The degree of their involvement in the study may depend on the other actors involved, typically other researchers who are part of the focus group or the larger research study.

In addition, their roles may differ based on the other market research techniques their organization uses, whether it includes survey research , concept testing, experimental research , or others.

The following lists the different aspects of the role of the focus group moderator:

- Discussion driver

- Interviewer

- Post-session and on-site analyst

The typical size of a focus group ranges between 5-10 people. 5-7 is the ideal amount of focus group participants , as these groups are purposely kept small.

That’s because when there are more than seven people present, it is difficult for every member to speak about a topic , or issue, and especially, to answer a specific question. It would also be difficult for the moderator to control a larger group and ensure everyone provides their insights. Additionally, some topics become irrelevant to continue discussing after the seventh person weighs in.

This method provides an interactive approach for research participants to share their viewpoints and experiences and for researchers to collect critical data on their subjects.

In direct opposition to quantitative market research , focus groups do not involve crunching large numbers or making assumptions based on large quantities. Instead, they focus on a small group of participants who represent different market segments and customer personas .

In keeping with the qualitative research approach, the moderator uses open-ended questions. The moderator may also use multiple-choice questions, but those are almost always followed up with questions to explain the reasoning behind choosing a particular answe r.

Thus, these discussions are typically filled with questions that delve into the “why” and “how,” as they seek to uncover context and motivations.

The purpose of this qualitative research methodology is to gain a wealth of insights into customer behavior , customer preferences , attitudes, beliefs and more, by way of a hands-on approach.

As such, the focus group method is intended to reap key insights from the discussion generated among participants . During the discussion, the participants are not solely encouraged to respond to questions the moderator asks but to engage in conversations with other participants.

In doing so, participants are prompted to reflect on their memories and draw from their own experiences.

The discussion of the focus is based on a pre-selected topic . This is usually tied to a larger market research campaign , which may be part of another business campaign, such as the strategic planning process , a marketing objective, a consumer insights campaign and more.

In market research specifically, the participants of a focus group are members of a business’s or in broader studies, an industry’s target market . This is the broad range of customers who are most likely to buy from a business and are typically the targets of marketing campaigns.

The shared characteristics of the study can be based on demographics, psychographics, geographic location and firmographics . Firmographics characteristics are those that involve business, as such, they would be included in a B2B focus group. This is a study on other businesses, typically those who are clients of a business.

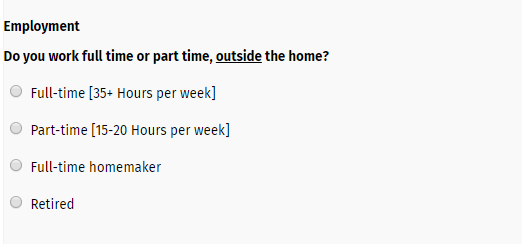

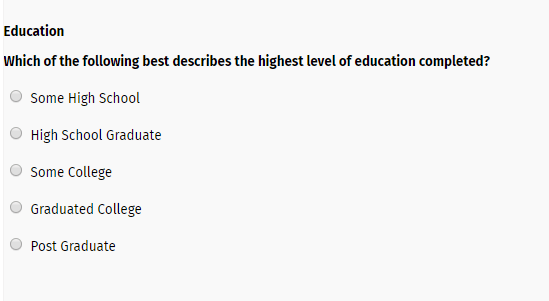

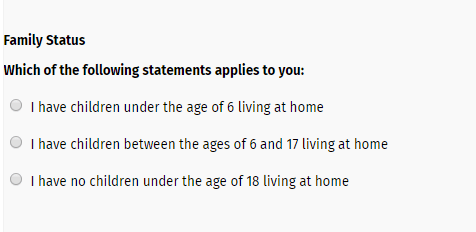

Demographic factors include characteristics such as gender, age range, ethnicity, income, education level, marital status, number of children and other such factors. These can include geographic locations, although geographical factors are considered a separate category in market segmentation .

Post-Focus Group Research

After the interview or set of interviews in this study, the moderator gathers the research and summarizes it. They may conduct their analysis or consult with other researchers on their team.

It is usually the other researchers who are better suited to understand and explain certain communication styles, and body language as well as to conduct further descriptive research . As such, there may be several rounds of analyses on the data from the focus group

Thus, in post-focus group research, which refers to post-interview research , there is usually a team of researchers involved in analyzing the group’s discussion and the data it produced.

After conducting an analysis, the researchers, including the moderator, will consult with one another to turn the raw data and analyzed research into a presentable document. This document should include the following:

- The purpose of the focus group study

- Demographics

- Psychographics

- Geographies

- Firmographics (if business personnel were studied)

- Key findings

- Explanations of key beliefs, sentiments, opinions, or thoughts

- This should include comparing them on a higher level, as each participant can represent a different segment of a target market.

- These can include statistics drawn from other market research methods, such as using an online survey tool , other non-focus group interviews and even sources of secondary research.

- This should include what the researchers plan to do next with the data, especially about other team members.

- After all, most data and research campaigns should be actionable. You wouldn’t want your efforts and highly-coveted data to sit idly and gather dust.

- This should be concise and round off the study.

- It should include a few of the most important findings, along with the plan of action and next steps.

They would then share it with other members of their organization . This often depends on the purpose of the focus group study.

For example, if it was for marketing purposes, the research would be primarily shared with the marketing team. If it was for customer development , it would be shared with the product team and so on.

Data Democratization in Post-Focus Group Research

There are going to be some cases in which the topic scrutinized in this kind of study doesn’t neatly correlate with a single department. This is perfectly fine, as certain business practices can be conducted cross-departmentally, or for the business at large.

This is where the democratization of data comes in. This concept refers to the practice and condition in which everybody in an organization has access to data. In such an environment there are no team members hindering access to the data. As such, there should be no bottlenecks preventing people from either using the data or understanding it.

This points to the need for the data to be both highly accessible and understandable . This underscores the i mportance of creating the post-research document mentioned in the previous section.

It is this document that serves as the go-to source for examining a business’s focus group study , and most importantly, putting the study to good use . This means the actions the focus group yields will go beyond those outlined in the plan of action section in the study’s main document.

Instead, in a democratized data environment, other team members, those who aren’t researchers or analysts, can analyze the data as well. This ability allows them to partake in the data for the decision-making process .

This is important for all companies, as data goes unused in too many businesses. Even though more companies are investing in customer data, up to 80% of all data goes unused . You wouldn’t want to waste your money and efforts on churning out data that goes unused.

As such, data democratization is a must in all market research campaigns, including docs groups.

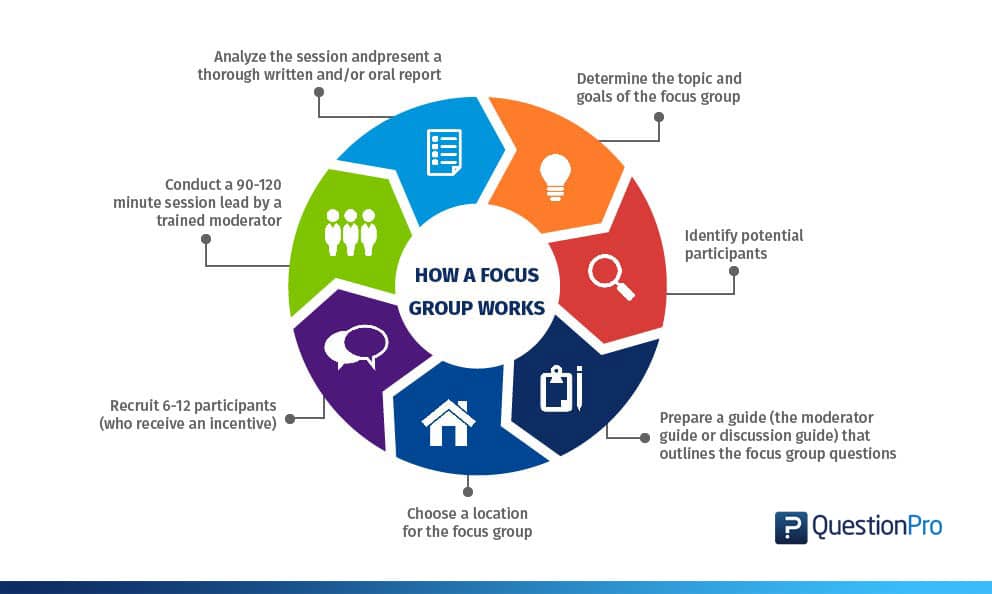

How Focus Groups Work

Focus groups use a specific methodology to clear away any ambiguity. As aforementioned, the small group that makes up a focus group comprises 5-7 people .

The participants are pre-recruited, similar to the mechanism for gaining research participants used in survey panels . They are enlisted based on shared characteristics, which are considered the subject of market research.

To reiterate, these characteristics include demographics, psychographics, purchase history, shopping behaviors, and other factors.

The qualifications that researchers use to recruit participants often bind the participants to a brand’s target market. However, brands can also study people outside their target market to learn how other consumers think and possibly gain them as customers.

Focus group discussions vary; they can involve feedback on a product, experience, or marketing campaign . They can also be used to discuss consumers’ opinions on different matters, such as pop culture, news and politics, especially if they relate to a brand’s industry.

The discussions are led by a moderator , who prompts questions and talking points. The moderator sets the conversation in motion, along with acting as the researcher. As such, the moderator also notes their observations.

The length, both in terms of questions and the discussion of the interviews themselves will vary. It is up to the moderator to decide whether they’ve gleaned enough information from the participants or not before moving on to another question or topic or ending the session .

Typically, these discussions involve using 10-12 questions to draw out responses on key topics that underpin the overall market research campaign. The discussion takes about 30 to 90 minutes.

A focus group environment should be o pen-minded as participants can have varying and even oppositional opinions. No one should be made to feel threatened or silenced, as every insight matters.

Focus groups are NOT to be conducted in the same way as interviews . They are far more interactive, but most importantly, they are not carried out on a one-on-one basis . Instead, they are group-focused activities, in which participants speak with each other instead of solely with an interviewer.

As such, the participants may influence each other , possibly swaying the minds of some members, or reinforcing someone’s opinions. Some participants will draw opposition or even aversion to their responses from others, possibly from the moderators themselves.

This is because they’re in the same broader target market, they are all individuals who hold their own opinions and convictions.

Regardless , the moderator should not input any of their opinions or beliefs into the discussion and be as neutral as possible . They should assume this neutrality even if they severely disagree with any of the participants.

Since focus groups are small, researchers often conduct several (3-4) of them, which includes hosting several interviews per focus group, across different geographic locations. This way they can reap the maximum amount of insights and satisfy all of their research campaigns.

The Pros and Cons of Focus Groups

This market research method offers several advantages. These will help propel you to understand your customer base or subject matter much better. They will also help carry your research to completion. But, they have a few drawbacks as well. Researchers and businesses ought to consider both before choosing this research method.

- Researchers can probe the deep feelings, perceptions and beliefs of their intended subjects.

- When members are engaged, they provide invaluable information that removes any obscurities surrounding a topic.

- They generate results fairly quickly, as each session lasts no more than 90 minutes.

- Researchers can study body language, facial expressions and other non-verbal signs.

- Not all questions need to be premeditated, as they can be produced based on the direction of the conversation.

- Given that this is a discussion, you may discover even more insights than you had originally planned, including on other adjacent topics.

- The thoughts of a small group that fits a target market are useful but are not representative of a larger population.

- Recruitment will take a significant portion of the time.

- Traversing different geographic areas, if need be, is also time-consuming.

- Some members will be dominant while others will contribute less to the discussion.

- Certain participants can sway the discussion, even making it veer towards irrelevant territories.

- They can’t be used for quantitative research.

- They are therefore subject to social pressures and acquiescence bias , in which respondents tend to select positive responses or those with positive connotations.

- As such, there is a lack of accuracy, as these groups are not anonymous.

The moderator of a focus group should ask specialized questions to reap as much intelligence as possible. While this format is generally flexible, there are still certain question types that you should incorporate. These will help you hatch the questions you’ll need.

Here are the four types of questions that are most applicable to a focus group , along with question examples:

- Engagement questions

- These questions are designed to ease participants into the discussion by introducing themselves,

- These are easy questions posed early on to introduce the participants to each other, to make them more at ease, and to acquaint them with the main topic at hand.

- Tell us a bit about yourself.

- What do you generally think about ads in this industry?

- What do you think of this ad campaign?

- Exploration questions

- These questions probe deeper into the topic to get a feel of the participants’ feelings about it.

- These questions are to be asked after participants begin to ease into the conversation and become more active in it.

- Why do you feel that way?

- Have you seen better examples of this type of ad campaign?

- What would be a better way to go about it?

- Why do you feel this way about this [social] issue?

- Follow-up questions

- These are used to gain a better understanding of a previous question answered, or a previous topic addressed.

- These allow the moderator to get into the nitty-gritty of participants’ feelings and motivations.

- How do you go about this issue?

- Why do you feel this way?

- Is there anything that would change your mind about [this issue, method, way, etc]?

- How can this brand improve on serving [you, releasing a campaign, etc]?

- Exit questions

- These questions help conclude the session and should be asked when the moderator is certain that the group has expressed everything they can on the topic.

- They should be used to get confirmation on certain notions.

- Are you sure these are the best approaches?

- Is there anything else on this topic you’d like to add?

Do you need a focus group? If you do, you’ll need to know when to use them, which is rooted in the reason behind conducting them in the first place. As such, the when is closely tied to the why and how.

In short, knowing when to use a focus group depends on what you need it for. This will require you to turn to your research campaigns and needs. The following presents a few key moments and reasonings for when you should use this kind of research technique:

- To better understand the results of primary quantitative research or secondary quantitative data about qualitative aspects.

- Whenever you need to gain an explanation of something, whether it’s a phenomenon, a thing of the past, something current, something you still don’t understand.

- When you seek a more interactive research method as opposed to a textual or digitally-based one.

- When you require information about behaviors, motivations and other phenomena that are too complex for a questionnaire alone to reveal.

- In this case, the senior center already has a batch of possible participants to choose from, being the members of the center.

- In this case, the club can choose from a wide range of students at the college. They can promote their group via signs, a booth, email, etc.

Focus Groups Vs Online Surveys

Now that you’ve learned about the ins and outs of focus groups, it’s time to see how they stack up with another research method: online surveys . It’s key to compare them closely when you decide on the best research method you wish to conduct.

A focus group is a suitable method to garner qualitative research . It is far more interactive than seeking and providing written responses. So how do focus groups measure up against online surveys?

This method is useful for finding deep insights into a topic. It allows researchers to get as granular as possible, since they are speaking with the research subjects themselves and can ask anything that they didn’t include in a survey.

The following expounds on why online surveys provide researchers with more meaningful results and a more comprehensive market research experience. Use these insights to compare with the benefits of focus groups to determine the better option for your research needs.

Benefits that are second to none

An online survey platform , however, offers benefits that are second to no other market research method . That is because surveys offer more definitive results about a population since they are not limited to 10 or fewer research participants.

A potent online survey tool allows you to reach thousands of people — in just one survey alone.

This means surveys are the most apt tool for conducting quantitative research, something that a focus group cannot do .

What’s more, is that surveys can include open-ended questions and follow-up questions (depending on the online survey platform you use). This proves that surveys can also forge qualitative market research.

Thus , online survey platforms grant you the power to conduct both quantitative and qualitative research, giving you the most holistic research experience possible.

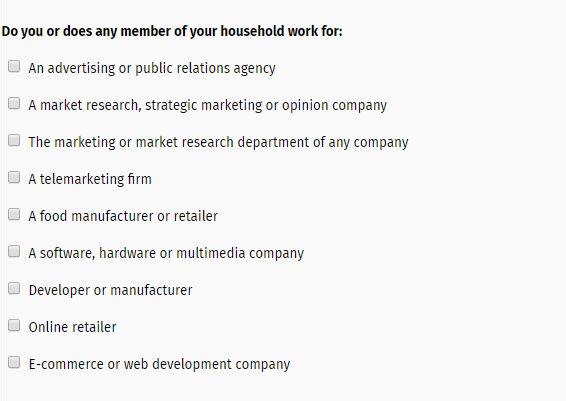

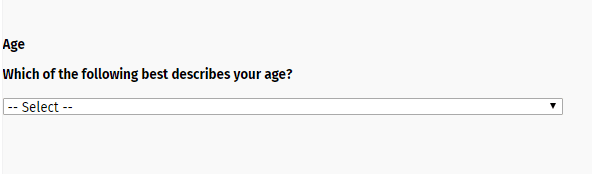

Additionally, there is no recruitment element. The survey platform is the recruiter in this case, as it allows only qualified respondents to take part in a survey .

You can create respondent requirements that are as granular as you wish, covering every minute detail of a customer profile and reaching any population.

This is because a strong online survey platform enables researchers to select precise respondent criteria , the kind that goes far beyond demographic selections alone.

That is because the screener portion of an online survey allows you to ask specific questions and only permits respondents who chose particular answers to take the survey.

When taking an online survey, respondents cannot be swayed by other participants as they would in a focus group as surveys are lone activities. Therefore, respondents take them in privacy.

Most importantly, survey software grants responders anonymity . There is no anonymity in a focus group, so more reserved members will feel less inclined to speak about certain things.

Additionally, when domineering respondents are present, it adds another layer of difficulty to the reticent participants , especially when it comes to speaking about views that are contrary to those of a dominant member.

However, with the anonymity of a survey, respondents are free to speak their minds. As such, surveys too can provide qualitative details — so long as researchers include open-ended questions.

So which is the better research technique? The answer is, it depends on your needs. Most often a focus group is used in tandem with other market research methods. As such, we recommend using both online surveys and focus groups for your research campaigns.

Here’s why:

Researchers can use a focus group to their advantage when they seek deeper insights into the perceptions and thoughts of various business matters.

Whether you’re testing out a new product idea, seeking the sentiment on an ad campaign, trying out new messaging, or seeking insights for any other purpose, a focus group is a useful method. However, they are but one market research method; as such they can and often are used with other market research techniques.

However, survey research is one of the most powerful forms of research , in that it empowers researchers to probe into anything and reach relatively anyone (should the survey platform allow it).

A strong online survey tool will deploy your survey to the most popular websites and apps , and take no more than 2 days to gather the number of respondents you input. In addition, it can send your survey to specific individuals through specific online channel s , such as social media, email, or landing pages. Your survey platform would need to offer the Distribution Link feature to do this.

In addition, the online survey platform you choose should allow you to create logic in your survey, that is, to route respondents to appropriate follow-up questions based on the answer they provide to a question . Choose a platform that offers advanced skip logic to do this.

All in all, researchers who are serious about conducting market research campaigns should use surveys alongside any other research method , including that of a focus group. It provides quantitative data, which focus groups do not, along with a wide breadth of key features and capabilities to complete any market research campaign.

Frequently asked questions

What is a focus group.

A focus group is a small group of survey research subjects, typically composed of 6-10 participants who take part in a moderated discussion about a particular topic. The participants are chosen based upon similar characteristics.

What is the moderator’s role in a focus group?

The moderator of a focus group leads the discussion by asking questions, proposing talking points, studying the responses and taking notes on the findings. The moderator keeps the conversion flowing and ensures that the discussion remains amicable, even when discussing sensitive topics or opposing opinions.

How can focus groups support a qualitative research project?

Focus groups are used in qualitative research to help gain a deeper understanding of the motivations behind the behavior, attitudes, or feelings of a group of people. By directly addressing a portion of the sample population, researchers can delve into the “why” or “how” behind data that has already been collected.

What are some of the benefits of a focus group?What are some of the disadvantages of focus groups? Focus groups are conducted with a smaller group of people, therefore the recruitment phase can take longer and the thoughts of the group may not represent the larger population. In addition, it is possible that stronger voices can dominate the conversation and influence or obscure the findings.

Focus groups allow for the exploration of deep feelings and opinions, can provoke thoughtful insights, provide quick results, allow researchers to study non-verbal signals that accompany the discussion, and can result in unexpected information.

What are some of the disadvantages of focus groups?

Focus groups are conducted with a smaller group of people, therefore the recruitment phase can take longer and the thoughts of the group may not represent the larger population. In addition, it is possible that stronger voices can dominate the conversation and influence or obscure the findings.

Do you want to distribute your survey? Pollfish offers you access to millions of targeted consumers to get survey responses from $0.95 per complete. Launch your survey today.

Privacy Preference Center

Privacy preferences.

- (855) 776-7763

Training Maker

All Products

Qualaroo Insights

ProProfs.com

- Sign Up Free

Do you want a free Survey Software?

We have the #1 Online Survey Maker Software to get actionable user insights.

Focus Group in Market Research: Types, Examples and Best Practices

Focus Group is one of the critical components of market research. It is an interactive group discussion method where selected participants share their thoughts on a particular product, service, or other things.

Suppose you are planning to launch a new product in the market. But before that, you want to undertake extensive market research to understand customers’ thoughts and opinions. Although surveys and questionnaires are helpful to a certain extent in conducting in-depth research, it’s not practical to extract enough actionable insights into a customers’ thought process or feelings. Moreover, they can’t provide quantitative data about the subject.

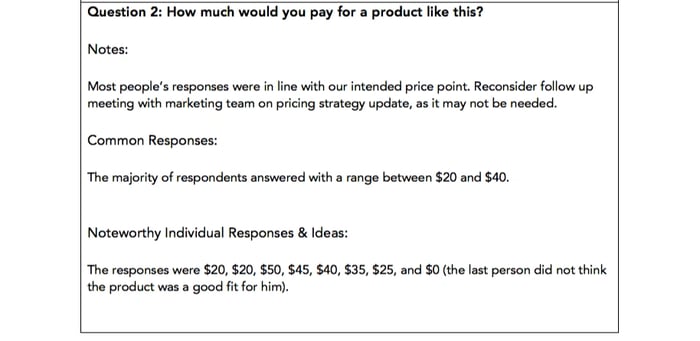

By conducting a focus group, you can understand what your target audience will like, so you can incorporate those elements into it before launching the product in the market. Or how much they are ready to spend so you can set the pricing accordingly.

This blog will discuss what a focus group is, its advantages, examples, and how to conduct one for your next research.

Let’s start.

What Is a Focus Group?

A focus group is one of the most popular and effective market research methods of gathering qualitative data through group interaction. It consists of a small group of people (usually 6-10) and a moderator to participate in a discussion. People are selected based on shared characteristics like geographic location, age group, ethnicity, shopping behavior, shopping history, or other such factors. The participants share their thoughts and feelings on the particular subject so the researcher can collect valuable data and make informed decisions.

The purpose of conducting a focus group is to understand a topic, whether it is a product, service, belief, perception, or anything in greater depth. It is used to identify people’s opinions, attitudes, sentiments and explore the reasons behind these.

Characteristics of Focus Groups

For focus research to be effective, it is essential to have the following given characteristics:

- Small-Group of People

Usually, focus groups consist of 6-10 people. The group needs to be small in size to make a valuable contribution to the discussion. Large groups can hinder the focus discussion as some people may dominate the conversation, and others might not present their thoughts.

- Homogenous Group

It is crucial for focus groups to have a degree of homogeneity. Specific topics can only be explored in greater depth when there is homogeneity among the participants about usage or attitudes toward the product. The participants can be similar in terms of demographic, geographical, psychographic, purchase behavior, attitude, or any other criteria that suit your research.

- Open-Ended Questions

Focus Group consists of pre-decided open-ended questions that enable participants to share their thoughts and feelings about the subject. For example, “what do you think about the features of this product?” It is important not to include close-ended questions like “Yes” or “No” as this will not result in open-ended, free-flowing discussion among the participants.

- Qualitative Data

Another essential characteristic of the focus group is that it offers qualitative data that is comprehensive in nature and not numerical. It provides a platform for in-depth discussion. Also, there is a lot more than the group interview. Essentially, it involves sharing first-hand opinions and experiences by participants.

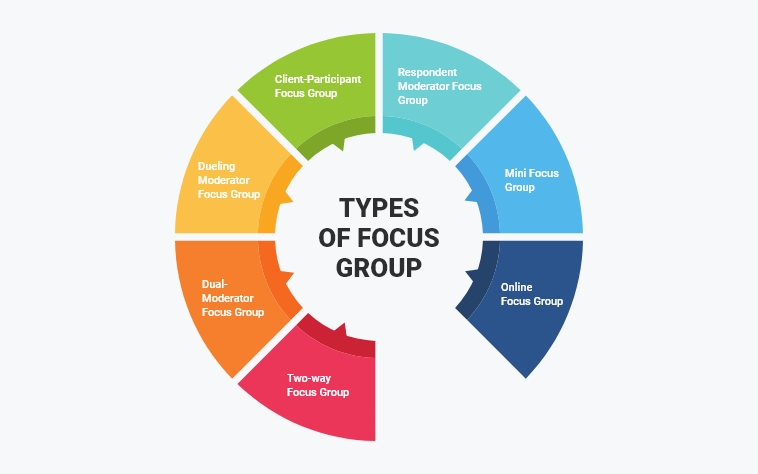

Types of Focus Group

Basically, there are 7 types of focus groups. Based on your research, you can select any type. Let’s have a look at them:

- Two-Way Focus Group

It involves two groups; each group with its own moderator. One group discusses the topic while the other group listens and observes them. Then, the second group discusses the subject by observing the thoughts of the first group. This arrangement aims to facilitate more discussion and additional insights about the particular topic.

- Dual-Moderator Focus Group

In this type of opinion group, two moderators are used. One moderator ensures smooth execution of the session, the other guarantees that each question is covered in the discussion.

- Dueling Moderator Focus Group

Just like the Dual-Moderator focus group, it also involves two moderators. The difference is that both moderators purposefully take opposite sides of the topic to explore both sides of an issue and generate new insights regarding the subject.

- Client-Participant Focus Group

In this type of arrangement, a client who asked to conduct the focus group is also sitting as a participant with the group. It gives the client more control over the discussion, and he can lead the qualitative discussion wherever he wants to.

- Respondent Moderator Focus Group

In this type of focus group, the researcher asks some participants to act as moderators for a temporary period to avoid unintentional bias. This type of arrangement changes the groups’ dynamics and makes people more open and honest with their answers.

- Mini Focus Group

In contrast to a regular research focus group with 6-10 people, a mini focus group has only 4-5 people. This type of event is suitable when a more intimate approach is needed as ordered by the client and subject matter.

- Online Focus Group

Using a teleconference or the internet, the remote or online focus group brings together people from different places who might not meet in person. Here, participants interact through a video call, and the moderator asks the questions and leads the conversation.

How to Conduct a Focus Group

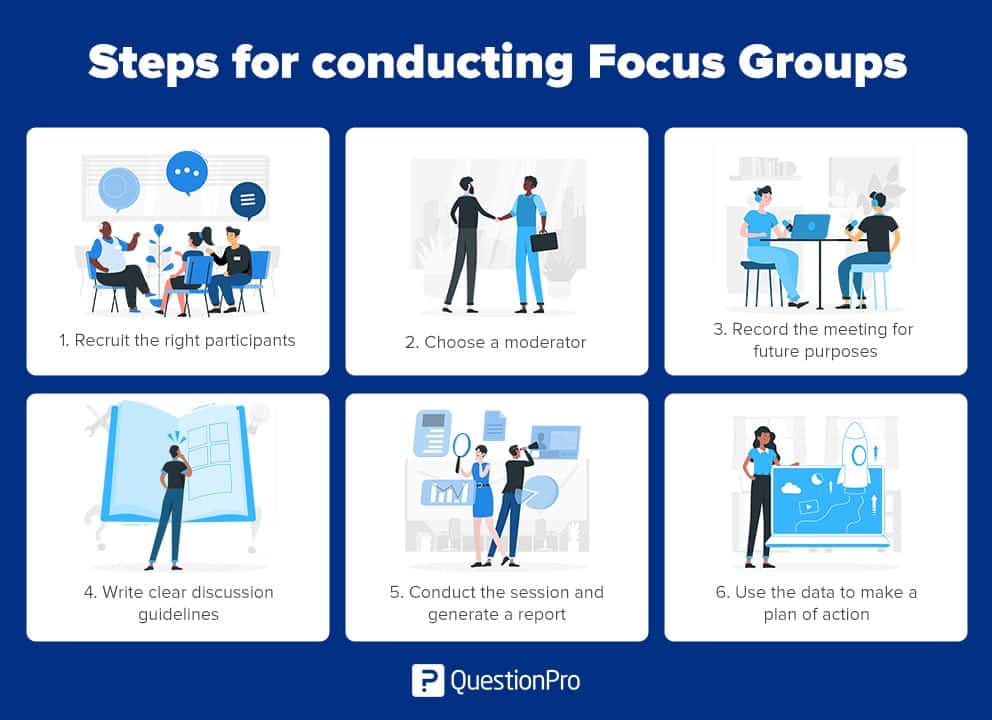

As discussed above, not all focus groups are the same. But there are some general steps that you can follow that help gather data from customers efficiently. Let’s discuss how to run a focus group:

1. Set Your Focus Group Objectives

Before you select the focus group participants, it is crucial to determine what you want to achieve from this activity. Why are you conducting this survey? For example, do you want to launch a new product or service? Or want to study in detail about your existing customers? Setting clear specific objectives will help you efficiently plan your focus group.

2. Select the Right Audience and Moderator

Establishing clear goals will help you decide the right target audience for focus groups. You need to select the people who have adequate knowledge of the topic so that they can add a valuable contribution to your group research.

It is also equally necessary to select the right moderator. Your moderator should understand the topic, ensure participation from all members, and that group discussion is steering in the right direction that aligns with research objectives.

3. Choose Time and Venue

You can either conduct focus groups offline or online mode. Having a group discussion online will have greater flexibility as more people worldwide will be able to join the focus grouping from the comfort of their homes. If you decide to get together in person, make sure to select the location that is easy to find and access and is large enough to accommodate your participants in one space, like a meeting room or hall.

Also, ensure to select the proper time when your target audience will be available. For instance, if your focus group requires professionals, you should go for weekends or after work hours.

4. Write The Questions

The objective of conducting a focus group is to gather rich information. Hence, it is crucial to write the survey questions engagingly before you actually complete the event. Ensure to keep the questions open-ended with no particular answer implied. You can start questions with words like “how,” “why,” and “what” to get more participation from participants. For instance, “How do you feel about using this product?”

5. Conduct the Session and Analyze the Data

The next step is conducting the focus groups. While following the list of topics to be covered is vital, the moderator should also remain open-minded and allow participants to speak about the things that they believe are significant. Make sure to record or document the entire conversation that will help you analyze the data and make conclusions.

Focus Group Research Best Practices

Running a successful focus group requires a lot of careful planning. So, if you’re new to this concept, you can follow the below tips to best utilize this qualitative research method .

- Have a Clear Strategy

For a focus group to be successful, it is important to have a clear plan before inviting the participants. You should be clear in your approach what end-result you want to achieve. For instance, you want qualitative data regarding the launch of new products or the effect of change in the pricing of existing products.

- Ask Important Questions in the Beginning

Usually, the participants are most focused at the beginning of the event. So, try to ask the most crucial focus group questions at the event’s start and steer the conservation in the direction that matches the research objectives. This will also ensure that all the essential questions are covered before the time runs out.

- Use Ice Breaker Questions

You can ask the participants to introduce themselves or ask quick icebreaker questions at the beginning of the event. It will help people ease up and interact more with other participants during the focus group discussions.

- Select the Convenient Venue

It is vital to select a public place for the focus group discussion that is easy to access, well connected by public transport, and has good parking. It will ensure that participants arrive on time without facing any significant difficulties. You can also provide clear instructions on reaching the location to your audience before the event.

- Create a Relaxing Environment

Participants will speak openly and freely only when they feel comfortable. Ensure to set a comfortable temperature in the hall/room, proper seating space, and arrange water bottles for everyone. You can also offer light snacks if you think the discussion will take more than 1 hour.

- Try to Interact More With Quiet Participants

In a focus group, some individuals may sometimes dominate the topic, so make sure to approach quiet participants directly so you can gain insights from everyone. You don’t have to be demanding; simply go around the room and direct particular focus group questionnaires to specific people.

- Keep the Duration Short

In general, the longer your focus group runs, the less interested people are likely to be in it. This can make it more challenging for people to come up with creative ideas or have a lively debate. Try to keep it short by not exceeding 1-2 hour duration.

Focus Group Examples

A Focus group is used in various fields to collect quantitative data about a subject. It is used in situations where public opinions guide an action. Let’s look at some of the focus group examples:

Focus Group in Political Field

Suppose a political party is interested to know how the working population would react to change in a specific policy. They can conduct the focus group research method in this scenario, where they can select some of the respondents who will act as the representative sample of a population. By observing the respondents discussing those policies, market researchers would analyze the data and report their findings to the party.

Focus Group in Marketing Field

Focus groups are also used in the Marketing and Sales domain. For example, a marketing firm wants to launch a new cosmetic product for its female customers. So, they will conduct the focus group of females, where they will discuss what features are essential for them, how much they are willing to pay for those benefits, which product they are currently using, why they like it, and what problems they face while using the product. The researcher can collect in-depth data based on these discussions and draw a suitable conclusion.

Focus Group Question Examples

Focus group questions fall into four categories, each of which is discussed below.

Introductory Questions

Introductory Questions are usually open-ended questions that are asked at the beginning of the focus group. The purpose of these questions is to stimulate the members to interact with each other and set the tone of the discussion. You can use introductory focus group questions to drive the discussion in the way you want it to go.

- Today we are here to discuss product X. What are your thoughts about it?

- When was the last time you used product X?

- What is your favorite brand of product X? Why?

- How often do you use this product?

- From where did you hear about product X?

- What do you like the best about product X?

- What do you not like about product X?

Exploration Questions

As the name suggests, these questions explore the subject more deeply. They stimulate responses from the audience that offer detailed insight into what they think of the particular topic. Exploration questions should be structured to draw out as much information from members as possible. Let’s discuss some focus group questions examples in this case.

- What will you like to change about product X?

- What first comes to your mind when you think of product X?

- Why have you stopped using product X?

- What do you like about brand X as compared to brand Y?

- Has your usage of product X declined or increased in the last three years?

- What are your specific expectations while selecting this product?

- If brand X is not available in the market, which brand will you choose and why?

Follow-up Questions

After exploration questions are asked, follow-up questions are used to collect specific insights to clarify anything that is unclear or to invite more participation from participants. Let’s discuss some of the focus group examples for follow-up questions.

- How can product X be improved?

- You said …………………….. about product X. What do you mean by that?

- Can anyone else relate to this (Name) experience?

- What is it about product X that makes you feel this way?

- Is there anyone in the group that doesn’t feel this way about product X?

- What are the chances that you will recommend this product to others?

Exit Questions

After all the pre-decided topics have been covered, you can ask exit questions to ensure that nothing has been left unsaid. Make sure that your participants don’t leave the event with any lingering doubt. Exit questions are designed in a way to wrap the event. Let’s discuss some focus group questions examples in this case.

- Is there anything else that you would like to add about product X?

- Would you like to discuss any other topic related to the product?

- Anything else that you feel essential has not been covered during the discussion?

- We discussed in detail about brand X but not Y. Would you like to add anything about brand Y?

Advantages of Focus Group

The best part of focus groups is their interactive nature. It allows participants to interact and discuss topics in detail that offers rich qualitative data. Focus Groups are beneficial because they provide an alternate way of collecting data from target consumers without using surveys that only produce quantitative data. Getting into the minds of customers is extremely difficult. But the focus group research method provides an engaging way to gather first-hand information of customer thoughts, opinions, and perception of your brand, service, or product.

Also, focus groups are flexible by design. You can understand what customers feel about the subject by their body language and way of speaking. Moreover, you can steer the discussion to match your research objectives to collect the information you want.

Ready to Collect Qualitative Data to Obtain Rich Customer Insight?

By now, you must have understood the importance of a focus group. There is no better way to collect in-depth customer insights than conducting this extensive market research method. Focus groups can be utilized in different fields where the action is based on the customer’s opinion. It is an excellent way to get into a customer’s head.

Focus groups can also be combined with other research methods like interviews and surveys to make it more effective. Based on the type of research and data you need, a focus group can be used with other research methods to offer actionable insights. You can use a robust survey tool to quickly deploy your survey and combine it with a focus group for efficient results.

About the author

Emma David is a seasoned market research professional with 8+ years of experience. Having kick-started her journey in research, she has developed rich expertise in employee engagement, survey creation and administration, and data management. Emma believes in the power of data to shape business performance positively. She continues to help brands and businesses make strategic decisions and improve their market standing through her understanding of research methodologies.

Popular Posts in This Category

50+ NPS Survey Questions Examples for Every Scenario

How to Create Popup Surveys for Your Website

How to Use Surveys for Content Marketing

10 Best Customer Experience Management Software in 2024

How to Calculate Customer Effort Score to Grow Your Business

How to Analyze Survey Data Like a Pro

What Is a Focus Group and How to Conduct It? (+ Examples)

Appinio Research · 14.09.2023 · 19min read

Have you ever wondered how businesses gain deep insights into consumer behavior, preferences, and opinions? Introducing focus groups—a powerful tool that unlocks the authentic voices of participants and reveals invaluable qualitative data. In this guide, we'll walk you through every step of the focus group process, from meticulous planning and skillful moderation to insightful analysis and actionable recommendations. Whether you're a researcher, marketer, or decision-maker, this guide equips you with the knowledge and strategies to harness the potential of focus groups and make informed, impactful decisions.

What is a Focus Group?

At its core, a focus group is a structured conversation involving a small group of individuals who share their thoughts, feelings, and experiences regarding a particular subject. The primary purpose of a focus group is to uncover nuanced insights that might not emerge through other research methods . You're essentially providing a platform for participants to express themselves freely, leading to a richer, more holistic understanding of the topic.

Why are Focus Groups Important in Market Research?

Focus groups play a pivotal role in market research . They allow you to delve into consumers' motivations, desires, and pain points, helping businesses tailor their products and services to better meet customer needs. Unlike quantitative data, focus groups provide qualitative context, shedding light on "why" people feel the way they do.

Focus groups serve as invaluable tools for gaining insights into people's opinions, attitudes, and perceptions. They bring together a diverse group of participants to engage in open discussions on a specific topic, offering qualitative data that goes beyond quantitative surveys.

Benefits of Conducting Focus Groups

Conducting focus groups offers a range of benefits that contribute to informed decision-making and improved outcomes:

- Rich Insights: Focus groups elicit detailed responses, offering a deeper understanding of participants' perspectives.

- Real-time Interaction: Observing participants' interactions in real-time provides valuable non-verbal cues that text-based surveys can't capture.

- Group Dynamics: Group discussions can stimulate new ideas as participants bounce thoughts off each other.

- Uncovering Unconscious Factors: Focus groups can reveal subconscious opinions or emotions that participants might not even be aware of.

- Flexible Approach: The open-ended nature of focus groups allows for unexpected insights to emerge.

How to Set Up a Focus Group?

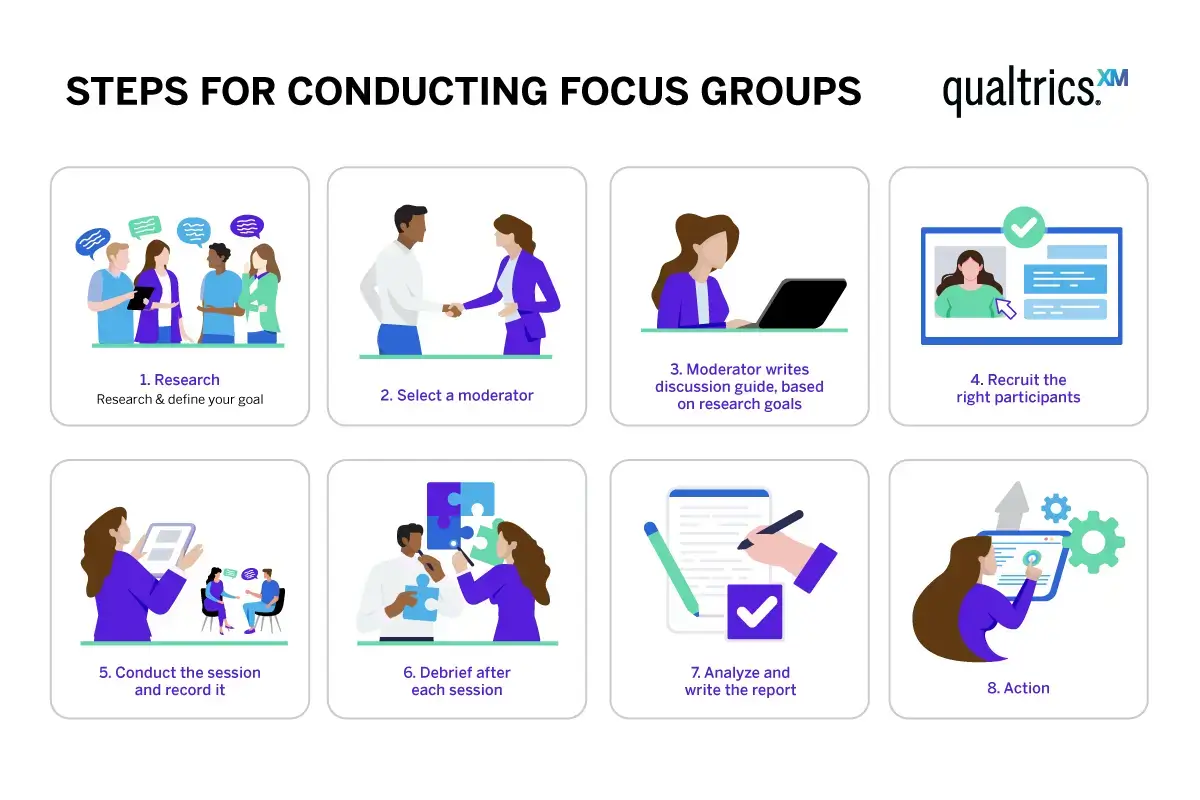

Before you embark on your focus group journey, thorough planning and meticulous preparation are crucial to ensuring the success of your sessions. Let's delve deeper into each step of this vital phase.

1. Identify Research Objectives

Research objectives serve as the compass guiding your focus group sessions. Clearly define what you aim to achieve through these discussions. Are you seeking insights into customer preferences, testing a new product concept, or exploring perceptions of a brand? Align your objectives with the overarching goals of your research to maintain focus and relevance.

2. Select Participant Demographics

Choosing the right participants is instrumental in obtaining diverse and representative insights. Consider the characteristics that are relevant to your research objectives. These may include:

- Income level

By selecting participants who mirror your target audience, you enhance the accuracy and applicability of your findings.

3. Recruit Participants

Effective participant recruitment is crucial for the success of your focus groups. Utilize various channels such as social media, online forums, email lists, and professional networks. Craft clear and compelling recruitment messages that communicate the focus group's purpose and participation benefits. Ensure that participants are genuinely interested, reliable, and willing to engage in open discussions.

4. Create Discussion Guidelines

Discussion guidelines provide structure to your focus group sessions while allowing for spontaneous conversations. Clearly outline the scope of the discussion, the key topics you intend to cover, and any specific areas of interest. Having a flexible framework ensures that discussions remain on track while permitting organic exploration of the subject matter.

5. Choose a Skilled Moderator

The role of the moderator is pivotal in shaping the dynamics and outcomes of your focus group. Opt for a skilled moderator who possesses strong facilitation and interpersonal skills. The moderator should be capable of guiding discussions, managing group dynamics, and ensuring that all participants have an equal opportunity to contribute. A skilled moderator can navigate unexpected twists in the conversation and encourage deeper insights.

How to Design a Focus Group?

Designing your focus group sessions requires thoughtful consideration of various elements to create an environment conducive to rich discussions.

1. Determine Group Size

The size of your focus group impacts the quality of interactions and the depth of insights. Aim for a balance between having a sufficiently diverse group and maintaining a manageable discussion. Generally, a group of 6 to 10 participants is optimal, allowing for a variety of viewpoints without overwhelming the conversation.

2. Select the Location

The choice of location plays a significant role, particularly for in-person focus groups. Select a comfortable and neutral venue that minimizes distractions and fosters open dialogue. If virtual sessions are more practical, ensure that the online platform is user-friendly and accessible to all participants, regardless of their technical proficiency.

3. Set the Duration

The duration of your focus group session impacts participant engagement and the quality of insights. Sessions typically last between 1 to 2 hours, striking a balance between allowing participants to delve into the topic without exhausting their attention spans. Longer sessions may lead to participant fatigue, which can hinder the quality of responses.

4. Prepare Stimuli (if applicable)

If your research involves presenting stimuli such as visuals, prototypes, or samples, careful preparation is essential. Ensure that your material is ready and relevant to the discussion topics. Stimuli can serve as conversation starters and tangible references for participants, enriching the depth of their responses.

5. Develop Open-Ended Questions

Crafting open-ended questions is an art that drives meaningful conversations. These questions encourage participants to openly share their thoughts, feelings, and experiences. Avoid closed-ended or leading questions, as they limit the scope of responses. Developing thoughtful and open-ended prompts creates opportunities for participants to express themselves authentically.

As you move forward with your focus group journey, remember that every aspect of planning and designing contributes to the quality of insights you'll gain. Your meticulous preparation sets the stage for rich, valuable discussions that uncover nuances and perspectives that quantitative data alone can't provide.

How to Conduct a Focus Group?

With your meticulous planning in place, it's time to bring your focus group to life. Conducting a focus group involves skillful facilitation, attentive moderation, and the ability to navigate diverse perspectives.

Let's explore the intricacies of this process and how to ensure a successful session.

Icebreaker Activities

Begin your focus group session with engaging icebreaker activities. Icebreakers serve multiple purposes, from easing participants into the conversation to creating a comfortable atmosphere for open sharing.

Some common icebreaker activities include:

- Introduction Round: Have each participant introduce themselves, sharing their name, background, and a fun fact related to the topic.

- "Two Truths and a Lie": Participants share two factual statements and one false statement about themselves, prompting discussion as others guess the lie.

Establishing Group Norms

Setting clear group norms from the outset creates a respectful and productive discussion environment. Norms ensure participants feel valued, heard, and safe sharing their viewpoints.

- Active Listening: Encourage attentive listening by asking participants to refrain from interrupting while others speak.

- Respectful Interaction: Emphasize the importance of respectful disagreement and constructive feedback.

- Confidentiality: Stress that participants should keep the discussion content confidential, fostering an environment of trust.

- Equal Participation: Encourage balanced participation by ensuring everyone has a chance to share their thoughts.

Moderator's Role and Techniques

The role of the moderator is pivotal in guiding discussions while maintaining a balanced and focused conversation. A skilled moderator employs various techniques to facilitate meaningful interactions:

- Active Listening: The moderator listens attentively to participants' responses, demonstrating that their opinions are valued.

- Probing: The moderator asks follow-up questions to dig deeper into participants' responses and uncover underlying motivations.

- Reflection: Summarizing participants' contributions shows that their thoughts are being accurately captured.

- Redirecting: If discussions veer off-topic, the moderator gently guides the conversation back to the main subject.

Encouraging Balanced Participation

Balanced involvement ensures that all participants have the opportunity to contribute. Some individuals naturally dominate discussions, while others might hesitate to speak up.

Techniques to encourage balanced participation include:

- Direct Questions: Address specific questions to participants who haven't spoken much, inviting their input.

- Round-Robin Sharing: Go around the group, giving each participant a chance to share their thoughts on a particular topic.

- Thought Pairing: Ask participants to pair up and share their perspectives with a partner before sharing with the larger group.

Probing for Deeper Insights

As discussions progress, employing probing techniques helps uncover deeper insights beneath surface-level responses. Probing involves asking follow-up questions that encourage participants to elaborate on their thoughts and feelings:

- "Why" Questions: Ask participants to explain the reasoning behind their opinions. For example, "Why do you think this approach would be effective?"

- "Tell Me More" Prompt: Encourage participants to elaborate by simply asking them to share more details about a specific point they made.

- Hypothetical Scenarios: Present hypothetical scenarios related to the topic and ask participants how they would respond, leading to more nuanced insights.

By skillfully employing these techniques, you can create an environment where participants feel comfortable expressing their opinions and where discussions naturally flow, leading to in-depth insights that you can later analyze.

How to Collect Focus Group Data?

With your focus group sessions successfully conducted, the next phase involves extracting meaningful insights from the rich discussions. We'll look at popular data collection and analysis methods to ensure that your findings are both accurate and actionable.

Recording and Transcribing Sessions

Recording focus group sessions is essential to capture participants' responses in their own words and preserve the nuances of the conversation.

- Recording: Use audio or video recording equipment to capture the entire discussion. Ensure that participants are comfortable with being recorded and understand the purpose of the recording.

- Transcribing: Transcribe the recorded sessions verbatim. Transcriptions provide a textual version of the discussions, which is easier to review and analyze.

Identifying Key Themes and Patterns

As you review the transcribed discussions, focus on identifying emerging themes and patterns. Themes are recurring topics or ideas that participants discuss, while patterns involve the connections between these themes. Look for insights that align with your research objectives.

- Open Coding: Start with open coding, where you assign preliminary labels to sections of the text corresponding to certain themes.

- Axial Coding: Organize the open codes into broader categories or themes, establishing relationships between them.

- Selective Coding: Refine the codes further, focusing on the most significant themes and their connections.

Coding and Categorizing Responses

Coding and categorization involve systematically organizing participants' responses based on identified themes and patterns. This process allows you to aggregate and compare the data, making it easier to draw conclusions.

- Codebook Development: Create a codebook that outlines the themes, definitions, and examples for each code.

- Applying Codes: Read through the transcribed data and apply the relevant codes to sections corresponding to each theme.

- Categorization: Group similar codes together to form categories that encapsulate broader concepts.

Using Qualitative Analysis Software

Qualitative analysis software can streamline the process of coding, categorization, and data management. Platforms like Appinio offer features that enhance the efficiency and accuracy of your analysis:

- Code Management: Software allows you to easily create, apply, and modify codes.

- Search and Retrieval: Quickly search for specific keywords or themes within the transcribed data.

- Visualization: Some tools provide visual representations of the data, making it easier to identify patterns and trends.

Extracting Actionable Insights

From the coded and categorized data, you can extract actionable insights that inform decision-making. These insights are drawn from the participants' perspectives and can lead to improvements in products, services, or strategies:

- Quoting Participant Responses: Use direct quotes from participants to illustrate key points and provide authenticity to your findings.

- Patterns and Trends: Identify overarching patterns and trends that provide a holistic understanding of participants' opinions.

- Identify Opportunities: Look for opportunities for innovation, improvements, or addressing pain points that participants highlight.

By meticulously analyzing the transcribed data and extracting meaningful insights, you bridge the gap between raw conversation and actionable recommendations that can drive positive change.

How to Analyze Focus Group Data?

As you move into the interpretation and reporting phase of your focus group research, you'll synthesize the gathered insights into a coherent narrative. Here's how you can effectively interpret and communicate your findings to various stakeholders.

1. Summarize Findings

Summarizing the key findings of your focus group sessions provides a concise overview of the insights gathered. Focus on the most salient themes, patterns, and opinions that emerged during the discussions. This summary sets the stage for more in-depth exploration in the subsequent sections.

2. Relate Findings to Research Objectives

Connect the dots between your findings and the initial research objectives you established. Highlight how each identified theme or pattern addresses specific research goals. This linkage reinforces the relevance of your insights and underscores the value of your focus group research.

3. Provide Rich Descriptions

Enrich your report with detailed descriptions of participants' responses. These descriptions add depth and context to your findings, helping stakeholders understand the nuances of participants' opinions and perspectives. Paint a vivid picture of the discussions to ensure your audience gains a comprehensive understanding.

4. Incorporate Participant Quotes

Incorporating direct quotes from participants adds authenticity and humanizes your findings. Quotes allow stakeholders to hear participants' voices firsthand, making the insights more relatable. Select quotes that encapsulate key points, emotions, or unique perspectives shared during the focus group discussions.

5. Make Data-Driven Recommendations

Formulate actionable recommendations based on the insights extracted from your focus group data. These recommendations should be grounded in the participants' perspectives and aligned with your research objectives. Whether refining a marketing strategy, modifying a product feature, or enhancing customer service, your recommendations should be informed and practical.

How to Lead a Focus Group?

Conducting focus groups comes with its own set of challenges. By adhering to best practices, you can navigate these challenges effectively and ensure the integrity of your research.

- Ensure Objectivity and Impartiality: Maintain objectivity throughout your focus group research. As the moderator, your role is facilitating discussions, not influencing outcomes. Avoid expressing personal opinions or steering the conversation in a particular direction.

- Minimize Groupthink and Bias: Be vigilant about group dynamics that might lead to groupthink, where participants conform to the majority opinion. Encourage diverse viewpoints and foster an environment where participants feel comfortable expressing dissenting views.

- Deal with Dominant Participants: In some focus groups, specific individuals may dominate the conversation. Gently redirect the discussion to ensure all participants have an equal contribution opportunity. Use techniques like directly addressing quieter participants for their input.

- Address Sensitive Topics: When discussing sensitive topics, create a supportive and nonjudgmental environment. Approach these discussions with empathy and use considerate language. Clearly communicate that participants are free to share their thoughts without fear of judgment.

- Adapt to Virtual Focus Groups: Virtual focus groups offer convenience but present unique challenges. Ensure participants are comfortable with the technology and provide clear instructions for joining the virtual session. Be prepared to troubleshoot technical issues that may arise.

Navigating these best practices and challenges ensures that your focus group research is conducted ethically, rigorously, and effectively.

Focus Group Examples

Let's explore how focus groups can be applied across various domains to extract valuable insights and drive informed decisions.

Example 1: SaaS Product Development

Imagine a SaaS company aiming to enhance its project management software. To gather insights for improvements, they conduct a focus group with current users:

- Planning: The company identifies research objectives, including user experience enhancement and feature preferences.

- Participants: They recruit a diverse group of existing users, ranging from freelancers to project managers.

- Discussion: The focus group discusses pain points, desired features, and overall user satisfaction.

- Analysis: The company analyzes transcribed discussions, identifying recurring themes like seamless collaboration and customizable dashboards.

- Insights: These insights lead to data-driven decisions, resulting in feature updates like improved collaboration tools and a user-customizable interface.

Example 2: Business Strategy Alignment

A retail chain considers expanding its product offerings. To align their business strategy with customer preferences, they conduct a focus group:

- Planning: The company defines research objectives to understand customer preferences and potential demand.

- Participants: They select a mix of loyal and potential new customers from various demographics.

- Discussion: The focus group explores participants' shopping habits, preferences, and thoughts on the proposed products.

- Analysis: The company identifies patterns, discovering that participants value eco-friendly products and unique offerings.

- Insights: Equipped with insights, the retail chain refines its expansion strategy to include sustainable products and innovative offerings, resonating with customer expectations.

Example 3: Academic Research

An academic researcher is exploring attitudes toward online learning. They decide to use focus groups to delve into students' perspectives:

- Planning: The researcher outlines research objectives centered around understanding students' experiences with online learning.

- Participants: A mix of online and in-person students with varying academic backgrounds and preferences.

- Discussion: The focus group conversations revolve around challenges, advantages, and suggestions for enhancing online education.

- Analysis: The researcher uncovers recurring themes, such as the importance of interactive content and effective communication.

- Insights: The researcher contributes to developing more engaging online courses, prioritizing interactive elements and clear communication channels.

These examples showcase the versatility of focus groups in capturing nuanced insights across diverse domains. Whether it's shaping software features, refining business strategies, or informing academic research, focus groups provide a platform to tap into authentic participant perspectives, resulting in well-informed decisions and strategies.

Focus groups are not just discussions—they're windows into understanding, catalysts for improvement, and sources of innovation. Following the steps outlined in this guide, you've gained the tools to orchestrate meaningful conversations, extract nuanced insights, and translate those insights into actionable recommendations. Remember, each participant's voice adds a unique brushstroke to the canvas of insights, and your role as a skilled moderator brings those brushstrokes to life.

As you venture into focus groups, approach each session with curiosity and openness. Listen actively, probe gently, and navigate group dynamics with finesse. Whether you're fine-tuning a marketing campaign, shaping the next product iteration, or charting the course for your organization's future, the authentic perspectives gathered through focus groups will guide your way. Embrace the art of facilitation, savor the richness of discussion, and let the insights gained propel you toward confident decisions and successful outcomes. Your commitment to the power of dialogue ensures that participants' voices continue to shape meaningful change.

How to Conduct a Focus Group online in Minutes?

Discover the revolutionary way to conduct focus groups and gain invaluable insights in just minutes. Appinio , a dynamic real-time market research platform, empowers companies to tap into consumer perspectives swiftly and effectively.

By handling the research and technology complexities, Appinio frees you to focus on what truly matters – swift, data-driven decision-making. Uncover the excitement of seamless integration, intuitive processes, and lightning-fast answers to fuel your business success.

Why Appinio?

- Transformative Speed: From questions to insights in minutes, Appinio ensures rapid access to the consumer pulse.

- Seamless Integration: Integrate real-time consumer insights seamlessly into everyday decision-making.

- Empower Your Choices: Embrace the power of data-driven decisions without the hassle of traditional research methods.

Join the loop 💌

Be the first to hear about new updates, product news, and data insights. We'll send it all straight to your inbox.

Get the latest market research news straight to your inbox! 💌

Wait, there's more

16.05.2024 | 30min read

Time Series Analysis: Definition, Types, Techniques, Examples

14.05.2024 | 30min read

Experimental Research: Definition, Types, Design, Examples

07.05.2024 | 29min read

Interval Scale: Definition, Characteristics, Examples

- Our Process

- Research & Strategy

- Student Ambassadors

- On Campus Media

- Digital Reach

- Experiential / Events

- Student Nano Social Influencers

- Case Studies

- Campus Insider

The Ultimate Focus Group Marketing Guide: Definition, Benefits & More

Struggling to understand your customers’ deepest thoughts? Focus groups have been unlocking consumer insights since the 1940s. Our ultimate guide offers you key tactics to tap into what really makes your audience tick through effective focus group marketing.

Dive in and discover how!

Key Takeaways

- Focus groups provide qualitative insights by bringing together 6 – 10 people to discuss and give feedback on topics, helping marketers understand consumer behavior and opinions.

- They originated in the mid – 20th century for sociological studies and have evolved with technology, now including virtual formats that expand reach across locations.

- The role of a skilled moderator is crucial to guide discussions, maintain engagement, and ensure every participant has a voice during the focus group session.

- Best practices include establishing clear ground rules before discussion, seeking diverse participant representation, using co-creation for idea development, and involving clients to add credibility.

- Consider alternatives to focus groups when statistical data is required or when time constraints demand quicker research methods.

Table of Contents

What is a Focus Group?

A focus group is a research powerhouse, assembling selected individuals to deep dive into opinions and attitudes about products or services, providing marketers with invaluable qualitative insights.

This dynamic tool has evolved over the years to become a crucial element in gauging consumer response before market strategies are carved in stone.

Definition and History

A focus group is a market research method that gathers people to discuss and provide feedback on products, marketing campaigns, or ideas. It presents a dynamic way to collect qualitative insights from participants through interactive group discussions.

Typically, the discussion happens under the guidance of a moderator who steers the conversation towards critical talking points while ensuring everyone has an opportunity to share their thoughts.

The origins of focus groups trace back to sociological studies and opinion polling in the mid-20th century. Social scientist Robert Merton is often credited with developing this technique during World War II when it was used to assess the effectiveness of propaganda.

Since then, marketers have harnessed focus groups for consumer behavior analysis, concept testing, and gathering consumer insights crucial for product positioning and market segmentation.

This method has expanded over time with technological advancements allowing online focus groups and virtual formats that accommodate broader participation across geographical locations.

Focus Group Format

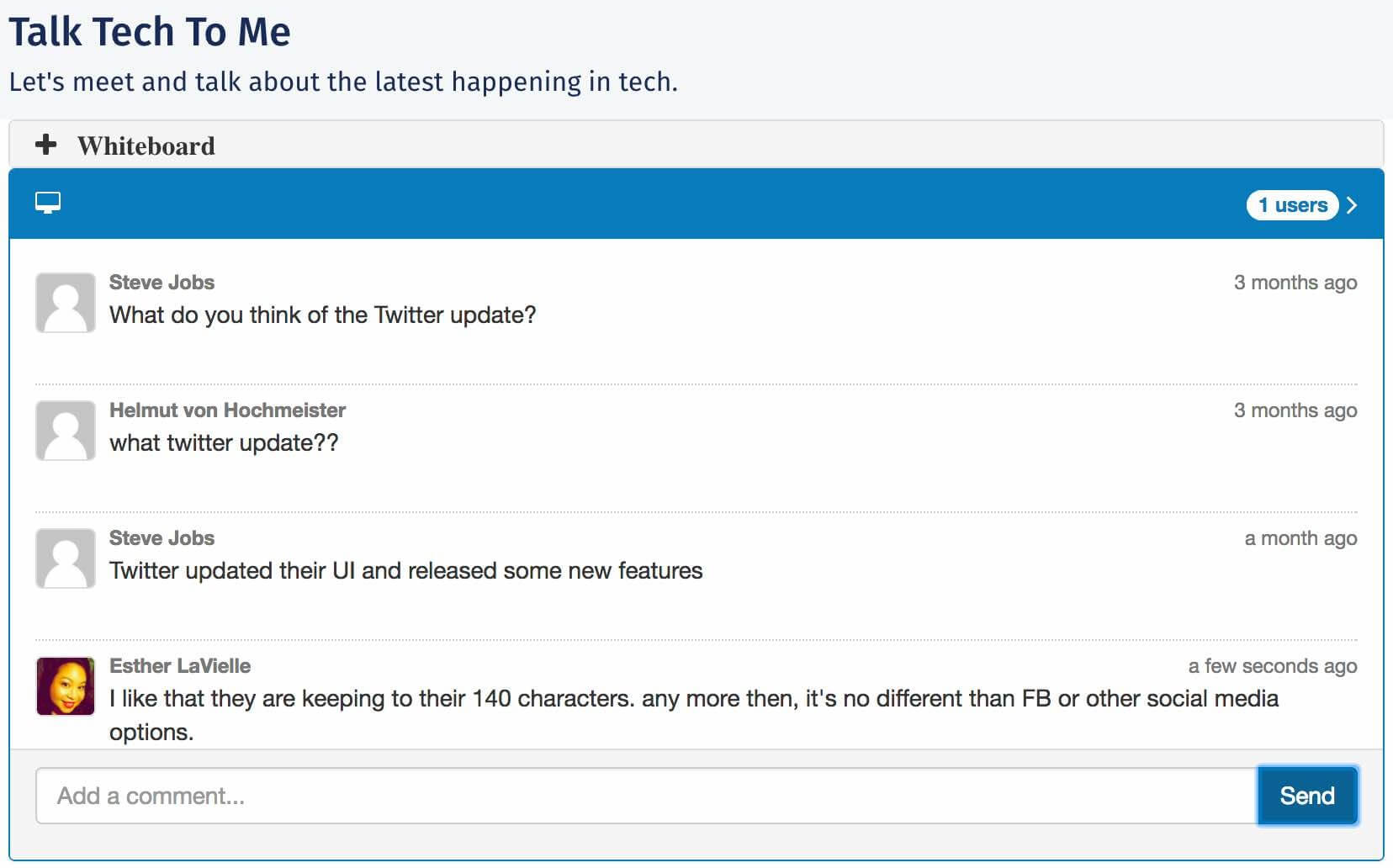

In a focus group, typically 6-10 people come together to discuss and give feedback on specific topics or products. The session often takes place in a comfortable room with one-way mirrors for observers.

Each group follows a structured format that includes an introduction by the moderator, who explains the purpose of the discussion and sets out any rules. Participants are then encouraged to openly share their thoughts, which creates valuable qualitative insights into consumer behavior.

The moderator plays a crucial role throughout; they keep the conversation on track while ensuring everyone has an opportunity to speak. Audio or video recordings capture everything said so that nothing is missed during analysis.

Tools like whiteboards or projectors may be used to stimulate discussion and showcase concepts for participant reaction. This interactive group setup allows for dynamic exchanges between participants, sparking deeper discussions about market segmentation, product positioning, and customer insights.

Pros and Cons

After discussing the format of focus groups, it’s important to weigh their advantages and disadvantages to better understand their role in market research.

Moving forward, understanding how to run a focus group effectively is crucial for harnessing these benefits while mitigating the drawbacks.

How to Run a Focus Group

Diving into the heart of qualitative market research, we uncover the steps necessary to steer a focus group from inception to insightful conclusion. It’s about orchestrating an environment conducive to candid conversation and extracting valuable nuggets of truth that can pivot your marketing strategy in real-time.

Choosing a Topic

Selecting an engaging topic is vital for the success of a focus group. The chosen subject must resonate with your participants and align with the objectives of your market research.

It should delve into areas where you seek qualitative insights, such as consumer behavior or product positioning. Aim to identify gaps in your understanding or aspects of consumer feedback that could significantly influence your marketing strategy.

Pick a theme that encourages interactive group discussion and keeps everyone invested throughout the session. This ensures that each participant has ample opportunity to contribute their unique perspectives, leading to richer data analysis later on.

Once the topic is set, you’ll move on to crafting questions designed to probe deeply into participants’ thoughts and experiences.

Preparing Questions

Once you’ve pinpointed the topic, crafting questions for your focus group comes next. These questions are vital tools that guide the interactive group discussion toward valuable insights.

Make sure they are open-ended to encourage participants to share their thoughts in detail. Your inquiries should tap into consumer behavior and explore different aspects of product positioning and brand perception.

Design every question with a clear purpose in mind, aiming to gather qualitative research data that highlights market segmentation issues or identifies customer insights during product testing.

Questions must be structured in a way that prevents confusion and keeps the conversation on track for actionable feedback. Avoid leading or biased wording which could skew the results; instead, prioritize clarity and neutrality to ensure authentic responses from your target audience.

Recruiting and Scheduling Participants

Recruiting the right participants for a focus group is crucial. Scheduling them effectively ensures a smooth market research process.

- Identify your target audience to make sure the feedback is relevant and insightful.

- Use various channels such as social media, email campaigns, or recruitment agencies to find potential participants.

- Screen candidates with surveys or quick phone calls to verify they match your market segmentation criteria.

- Provide clear information about the focus group’s purpose and what will be expected from the participants.

- Offer incentives that appeal to your demographic, whether it’s cash, gift cards, or products.

- Schedule sessions at different times to accommodate diverse schedules and increase attendance rates.

- Confirm participation with reminders via email or text messages as the date approaches.

- Prepare backup participants in case of last – minute dropouts to keep your focus group fully staffed.

- Ensure that privacy policies are explained and consent forms are sent out ahead of time for a seamless start during the actual event.

- Use online scheduling tools for virtual focus groups to manage time differences and technical setup.

The Role of the Moderator

The moderator serves as the navigator of a focus group, ensuring the conversation stays on course and every voice is heard. They create an inviting atmosphere where participants feel comfortable sharing their honest thoughts and reactions.

It’s the moderator’s job to probe deeper into responses for clearer understanding while keeping discussions lively yet focused. Their skill in asking the right questions at just the right time can unearth valuable consumer insights that might otherwise remain hidden.

A skilled moderator effectively manages group dynamics, preventing any one participant from dominating and encouraging quieter members to contribute. They’re adept at reading non-verbal cues, sensing when someone has more to add or if a topic shift is needed to maintain engagement.