- Interactive Videos

- Overview & Comparison

- THINKING PRO - Curriculum Unit

- Benefits for School Admin

- Benefits for Teachers

- Social Studies

- English Language Learners

- Foundation Giving

- Corporate Giving

- Individual Giving

- Partnerships

The Importance of Critical Thinking for News Media Literacy

With news available at the tap of a finger, keyboard, or remote, we are often exposed to a barrage of news media. Some of it is high quality, informational news, while other pieces may be riddled with biases, inaccuracies, and misinformation. That’s why it’s so important for students to learn to properly evaluate the news they’re consuming. Read on for an exploration of news media literacy and the importance of critical thinking in supporting it.

News Media Literacy

News media literacy is the ability to critically analyze, evaluate, and interpret the information presented in news media. It involves understanding how news is produced, identifying bias and misinformation, and being able to distinguish between fact and opinion. In our modern world, where information is instantly available and constantly changing, news media literacy has become an essential skill for individuals of all ages to navigate the media landscape and make informed decisions.

Students being taught news media literacy develop a variety of interrelated and crucial skills and knowledge. They learn to identify when news sources are presenting biased or misleading information and to seek out additional sources to confirm or refute claims. News literacy also helps students understand how news is produced and distributed, including the role of journalists, media organizations, and the impact of social media on the news cycle.

A study in the Journal of Media Literacy Education found that highly news literate teens were:

- More intrinsically motivated to consume news

- More skeptical

- More knowledgeable about current events

This is important because it can help prevent the spread of misinformation and disinformation, both of which can have serious consequences, such as spreading false information about health, elections, or social issues. News media literacy skills can help students recognize harmful reporting or sharing, and take steps to stop their spread.

The difference news media literacy makes is not limited to the student alone, but can also impact their wider community. Authors Hobbs et al. explore this concept in their article “Learning to Engage: How Positive Attitudes about the News, Media Literacy, and Video Production Contribute to Adolescent Civic Engagement.” They found that “the best predictors of the intent to participate in civic engagement are having positive attitudes about news, current events, reporting, and journalism.”

Given its importance and wide-ranging impact, news media literacy is an essential part of education today. Here’s how teachers can use critical thinking to build up news literacy—and vice versa—in their students.

Critical Thinking Skills for News Literacy

Critical thinking is a key component of news media literacy, as it allows individuals to assess the accuracy and credibility of news sources, identify biases and misinformation, and make informed decisions. Critical thinking involves questioning assumptions, evaluating evidence, and considering multiple perspectives, which are all crucial skills for navigating our complex and constantly evolving media landscape. Let’s explore these critical thinking skills and their impact on news literacy in more depth.

Evaluating Sources and Evidence

One essential critical thinking skill that supports news literacy is the ability to evaluate sources. In today's world, where anyone can publish information online, it is important to be able to distinguish between credible sources and those that lack credibility. This means understanding the differences between primary and secondary sources, recognizing when a source is biased or unreliable, and evaluating the credentials of the author or publisher.

Being able to evaluate sources and evidence for credibility and accuracy allows students to identify fake news and other harmful media. Research on fake news and critical thinking highlights critical thinking as “an essential skill for identifying fake news.”

Analyzing Information

Another critical thinking skill that supports news literacy is the ability to analyze information. This involves breaking down complex information into its component parts, evaluating the evidence presented, and considering the implications of the information. For example, if a news article presents statistics about a particular issue, it is important to evaluate the methodology used to collect the data, the sample size, and the relevance of the statistics to the issue at hand.

Identifying and Evaluating Biases

Critical thinking also allows students to identify and evaluate biases. News sources may have biases based on political or social values, financial interests, or personal opinions. It is important to be able to recognize these biases and to evaluate how they may affect the presentation of information. By developing these critical thinking skills, students can become more discerning consumers of news media, and better equipped to make informed decisions based on the information presented.

How Practicing News Literacy Develops Critical Thinking

Becoming more news literate can also help develop critical thinking skills in turn. By engaging with news media and seeking out diverse perspectives on issues, individuals can develop their ability to question assumptions, evaluate evidence, and consider multiple perspectives. This can lead to a more nuanced understanding of complex issues and a greater appreciation for the diverse perspectives that exist in society.

This creates a powerful education win-win. News literacy and critical thinking effectively support each other and allow students to become informed and discerning consumers of media.

How THINKING PRO Helps Students Build News Literacy

Our THINKING PRO system is built around local news media and teaches students media literacy and critical thinking in a meaningful and impactful way. It walks students through a simple but effective process for analyzing news media, involving:

- Differentiating simple statements (answers to who, what, when, and where questions) and complex claims (answers to why and how questions)

- Evaluating evidence supporting each

- Differentiating evidence and opinion in complex claims

Our interactive learning videos allow students to hone these media literacy and critical thinking skills. With THINKING PRO, students will learn to:

- Identify various categories of claims that can be made within an informational text (e.g.: cause and effect, problem and solution, value judgments)

- Evaluate internal logic of informational text by:

- analyzing the consistency of information within the text and with one’s own background knowledge, and

- identifying conflicting information within the text.

- Synthesize information, as well as claims and their supporting evidence, across multiple passages of texts, and integrate it with one’s own understanding

Here at Thinking Habitats, we use thinking tools to empower young people to lead successful lives and contribute to the wellbeing of their communities. Our online platform has helped students improve their critical thinking, reading comprehension, and news media literacy, and has had significant individual and community impacts. Try THINKING PRO today , and join our students who feel more empowered in decision-making, more mindful with their news engagement, and more connected to their local community!

Hobbs, R., Donnelly, K., Friesem, J., & Moen, M. (2013). Learning to engage: How positive attitudes about the news, media literacy, and video production contribute to Adolescent Civic engagement. Educational Media International , 50 (4), 231–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523987.2013.862364

Machete, P., & Turpin, M. (2020). The use of critical thinking to identify fake news: A systematic literature review. Lecture Notes in Computer Science , 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45002-1_20

Maksl, A., Ashley, S., & Craft, S. (2015). Measuring News Media Literacy. Journal of Media Literacy Education , 6 (3), 29–45. https://doi.org/10.23860/jmle-6-3-3

Research guides: Identifying bias: What is bias? . University of Wisconsin Green Bay. (n.d.). https://libguides.uwgb.edu/bias

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Media Literacy in the Modern Age

How to understand the messages we observe all day every day

Cynthia Vinney, PhD is an expert in media psychology and a published scholar whose work has been published in peer-reviewed psychology journals.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/cynthiavinney-ec9442f2aae043bb90b1e7405288563a.jpeg)

Steven Gans, MD is board-certified in psychiatry and is an active supervisor, teacher, and mentor at Massachusetts General Hospital.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/steven-gans-1000-51582b7f23b6462f8713961deb74959f.jpg)

Morsa Images / Getty Images

How to Practice Media Literacy

Media literacy is the ability to apply critical thinking skills to the messages, signs, and symbols transmitted through mass media .

We live in a world that is saturated with media of all kinds, from newspapers to radio to television to the internet. Media literacy enables us to understand and evaluate all of the media messages we encounter on a daily basis, empowering us to make better choices about what we choose to read, watch, and listen to. It also helps us become smarter, more discerning members of society.

Media literacy is seen as an essential 21st-century skill by educators and scholars, including media psychologists . In fact, the mission statement of Division 46 of the American Psychological Association , the Society for Media Psychology and Technology , includes support for the development of media literacy.

Despite this, many people still dismiss media as harmless entertainment and claim they aren't influenced by its messages. However, research findings consistently demonstrate that people are impacted by the media messages they consume.

Media literacy interventions and education help children and adults recognize the influence media has and give them the knowledge and tools to mitigate its impact.

History of Media Literacy

The earliest attempts at media literacy education are often traced back to the British Film Institute's push in the late 1920s and early 1930s to teach analytical skills to media users. Around the same time in America, the Wisconsin Association for Better Broadcasters sought to teach citizens to be more critical consumers of media.

However, the goal of these initial media literacy efforts, which continued into the 1960s, was to protect students from media by warning them against its consumption. Despite this perspective, the dominance of media—and television in particular—continued to grow, even as interest in media literacy education waned.

More recently, the advent of the internet and portable technologies that enable us to consume media anywhere and anytime has led to a resurgence in the call for media literacy. Yet the goal is no longer to prevent people from using media, but to help them become more informed, thoughtful media consumers.

Although media literacy education has now become accepted and successful in English-speaking countries including Australia, Canada, and Britain, it has yet to become a standard part of the curriculum in the United States, where a lack of centralization has led to a scattershot approach to teaching practical media literacy skills.

Impact of Media Literacy

Despite America's lack of a standardized media literacy curriculum, study after study has shown the value of teaching people of all ages media literacy skills.

For example, a review of the research on media literacy education and reduction in racial and ethnic stereotypes found that children as young as 12 can be trained to recognize bias in media depictions of race and ethnicity and understand the harm it can cause.

Though the authors note that this topic is still understudied, they observe that the evidence suggests media literacy education can help adolescents become sensitive to prejudice and learn to appreciate diversity.

Meanwhile, multiple studies have shown that media literacy interventions reduce body dissatisfaction that can be the result of the consumption of media messages.

In one investigation, adolescent girls were shown an intervention video by the Dove Self-Esteem Fund before being shown images of ultra-thin models. While a control group reported lower body satisfaction and body esteem after viewing the images of the models, the group that viewed the intervention first didn't experience these negative effects.

Similarly, another study showed college women (who were at high risk for eating disorders ) reported less body dissatisfaction, a lower desire to be thin, and reduced internalization of societal beauty standards after participating in a media literacy intervention. The researchers concluded that media literacy training could help prevent eating disorders in high-risk individuals.

Moreover, studies have shown that media literacy education can help people better discern the truth of media claims, enabling them to detect "fake news" and make more informed decisions.

For instance, research into young adults' assessment of the accuracy of claims on controversial public issues was improved if the subjects had been exposed to media literacy education. In addition, another study showed that only people who underwent media literacy training engaged in critical social media posting practices that prevented them from posting false information about the COVID-19 pandemic.

The evidence for the benefits of media literacy suggests it is valuable for people of all ages to learn to be critical media consumers. Media scholar W. James Potter observes that all media messages include four dimensions:

- Cognitive : the information that is being conveyed

- Emotional : the underlying feelings that are being expressed

- Aesthetic: the overall precision and artistry of the message

- Moral : the values being conveyed through the message

Media psychologist Karen Dill-Shackleford suggests that we can use these four dimensions as a jumping off point to improve our media literacy skills. For example, let's say while streaming videos online we're exposed to an advertisement for a miracle weight loss drug. In order to better evaluate what the ad is really trying to tell us, we can break it down as follows:

- On the cognitive dimension we can assess what information the ad is conveying to us by asking some of the following questions: What does the ad promise the drug will do? Does it seem likely the drug can deliver on those promises? Who would need this kind of drug?

- On the emotional dimension, we can evaluate the feelings the creator of the ad wants us to feel: Do they want us to feel insecure about our weight? Do they want us to imagine the positive ways this drug could change our lives? Do they want us to envision the satisfaction we would feel after the drug delivers its quick fix?

- On the aesthetic dimension, we can determine how the ad employs messages and images to make us believe the product will deliver on its promises: Does the ad show "before" and "after" images of someone who supposedly took the drug? Does the "before" image look sad and the "after" image happy? Does the ad offer testimonials from people that are identified as experts?

- On the moral dimension, we can examine what the ad makers wanted to say: Are they equating thinness with happiness? Are they sending the message that it's a moral failing when someone is overweight? Are they saying that one has to be thin to be loved and respected?

This is one avenue for learning to practice media literacy in everyday life. Remember, the purpose of media literacy isn't to enjoy media less, it's to give people the tools to be active media consumers.

Not only will media literacy enable you to detect, analyze, and evaluate negative or false media messages, it will actually enable you to enjoy media more because it puts control over the media back into your hands. And research shows this is likely to increase your health and happiness.

About the Society for Media Psychology & Technology . Society for Media Psychology & Technology, Division 46 of the American Psychological Association. 2013.

Dill-Shackleford KE. How Fantasy Becomes Reality . New York: Oxford University Press; 2009.

Arke ET. Media Literacy: History, Progress, and Future Hopes . In: Dill-Shackleford KE, ed. The Oxford Handbook Of Media Psychology . 1st ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195398809.013.0006

Scharrer E, Ramasubramanian S. Intervening in the Media's Influence on Stereotypes of Race and Ethnicity: The Role of Media Literacy Education . Journal of Social Issues . 2015;71(1):171-185. doi:10.1111/josi.12103

Halliwell E, Easun A, Harcourt D. Body dissatisfaction: Can a short media literacy message reduce negative media exposure effects amongst adolescent girls? Br J Health Psychol . 2011;16(2):396-403. doi:10.1348/135910710x515714

Coughlin JW, Kalodner C. Media literacy as a prevention intervention for college women at low- or high-risk for eating disorders . Body Image . 2006;3(1):35-43. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.01.001

Kahne J, Bowyer B. Educating for Democracy in a Partisan Age: Confronting the Challenges of Motivated Reasoning and Misinformation . Am Educ Res J . 2016;54(1):3-34. doi:10.3102/0002831216679817

Melki J, Tamim H, Hadid D, Makki M, El Amine J, Hitti E. Mitigating infodemics: The relationship between news exposure and trust and belief in COVID-19 fake news and social media spreading . PLoS One . 2021;16(6). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0252830

Potter WJ. Media Literacy . 4th ed. Los Angeles: SAGE; 2008.

By Cynthia Vinney, PhD Cynthia Vinney, PhD is an expert in media psychology and a published scholar whose work has been published in peer-reviewed psychology journals.

Media and Information Literacy, a critical approach to literacy in the digital world

What does it mean to be literate in the 21 st century? On the celebration of the International Literacy Day (8 September), people’s attention is drawn to the kind of literacy skills we need to navigate the increasingly digitally mediated societies.

Stakeholders around the world are gradually embracing an expanded definition for literacy, going beyond the ability to write, read and understand words. Media and Information Literacy (MIL) emphasizes a critical approach to literacy. MIL recognizes that people are learning in the classroom as well as outside of the classroom through information, media and technological platforms. It enables people to question critically what they have read, heard and learned.

As a composite concept proposed by UNESCO in 2007, MIL covers all competencies related to information literacy and media literacy that also include digital or technological literacy. Ms Irina Bokova, Director-General of UNESCO has reiterated significance of MIL in this media and information landscape: “Media and information literacy has never been so vital, to build trust in information and knowledge at a time when notions of ‘truth’ have been challenged.”

MIL focuses on different and intersecting competencies to transform people’s interaction with information and learning environments online and offline. MIL includes competencies to search, critically evaluate, use and contribute information and media content wisely; knowledge of how to manage one’s rights online; understanding how to combat online hate speech and cyberbullying; understanding of the ethical issues surrounding the access and use of information; and engagement with media and ICTs to promote equality, free expression and tolerance, intercultural/interreligious dialogue, peace, etc. MIL is a nexus of human rights of which literacy is a primary right.

Learning through social media

In today’s 21 st century societies, it is necessary that all peoples acquire MIL competencies (knowledge, skills and attitude). Media and Information Literacy is for all, it is an integral part of education for all. Yet we cannot neglect to recognize that children and youth are at the heart of this need. Data shows that 70% of young people around the world are online. This means that the Internet, and social media in particular, should be seen as an opportunity for learning and can be used as a tool for the new forms of literacy.

The Policy Brief by UNESCO Institute for Information Technologies in Education, “Social Media for Learning by Means of ICT” underlines this potential of social media to “engage students on immediate and contextual concerns, such as current events, social activities and prospective employment.

UNESCO MIL CLICKS - To think critically and click wisely

For this reason, UNESCO initiated a social media innovation on Media and Information Literacy, MIL CLICKS (Media and Information Literacy: Critical-thinking, Creativity, Literacy, Intercultural, Citizenship, Knowledge and Sustainability).

MIL CLICKS is a way for people to acquire MIL competencies in their normal, day-to-day use of the Internet and social media. To think critically and click wisely. This is an unstructured approach, non-formal way of learning, using organic methods in an online environment of play, connecting and socializing.

MIL as a tool for sustainable development

In the global, sustainable context, MIL competencies are indispensable to the critical understanding and engagement in development of democratic participation, sustainable societies, building trust in media, good governance and peacebuilding. A recent UNESCO publication described the high relevance of MIL for the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

“Citizen's engagement in open development in connection with the SDGs are mediated by media and information providers including those on the Internet, as well as by their level of media and information literacy. It is on this basis that UNESCO, as part of its comprehensive MIL programme, has set up a MOOC on MIL,” says Alton Grizzle, UNESCO Programme Specialist.

UNESCO’s comprehensive MIL programme

UNESCO has been continuously developing MIL programme that has many aspects. MIL policies and strategies are needed and should be dovetailed with existing education, media, ICT, information, youth and culture policies.

The first step on this road from policy to action is to increase the number of MIL teachers and educators in formal and non-formal educational setting. This is why UNESCO has prepared a model Media and Information Literacy Curriculum for Teachers , which has been designed in an international context, through an all-inclusive, non-prescriptive approach and with adaptation in mind.

The mass media and information intermediaries can all assist in ensuring the permanence of MIL issues in the public. They can also highly contribute to all citizens in receiving information and media competencies. Guideline for Broadcasters on Promoting User-generated Content and Media and Information Literacy , prepared by UNESCO and the Commonwealth Broadcasting Association offers some insight in this direction.

UNESCO will be highlighting the need to build bridges between learning in the classroom and learning outside of the classroom through MIL at the Global MIL Week 2017 . Global MIL Week will be celebrated globally from 25 October to 5 November 2017 under the theme: “Media and Information Literacy in Critical Times: Re-imagining Ways of Learning and Information Environments”. The Global MIL Feature Conference will be held in Jamaica under the same theme from 24 to 27 October 2017, at the Jamaica Conference Centre in Kingston, hosted by The University of the West Indies (UWI).

Alton Grizzle , Programme Specialist – Media Development and Society Section

Other recent news

Common Sense Media

Movie & TV reviews for parents

- For Parents

- For Educators

- Our Work and Impact

Or browse by category:

- Get the app

- Movie Reviews

- Best Movie Lists

- Best Movies on Netflix, Disney+, and More

Common Sense Selections for Movies

50 Modern Movies All Kids Should Watch Before They're 12

- Best TV Lists

- Best TV Shows on Netflix, Disney+, and More

- Common Sense Selections for TV

- Video Reviews of TV Shows

Best Kids' Shows on Disney+

Best Kids' TV Shows on Netflix

- Book Reviews

- Best Book Lists

- Common Sense Selections for Books

8 Tips for Getting Kids Hooked on Books

50 Books All Kids Should Read Before They're 12

- Game Reviews

- Best Game Lists

Common Sense Selections for Games

- Video Reviews of Games

Nintendo Switch Games for Family Fun

- Podcast Reviews

- Best Podcast Lists

Common Sense Selections for Podcasts

Parents' Guide to Podcasts

- App Reviews

- Best App Lists

Social Networking for Teens

Gun-Free Action Game Apps

Reviews for AI Apps and Tools

- YouTube Channel Reviews

- YouTube Kids Channels by Topic

Parents' Ultimate Guide to YouTube Kids

YouTube Kids Channels for Gamers

- Preschoolers (2-4)

- Little Kids (5-7)

- Big Kids (8-9)

- Pre-Teens (10-12)

- Teens (13+)

- Screen Time

- Social Media

- Online Safety

- Identity and Community

Explaining the News to Our Kids

- Family Tech Planners

- Digital Skills

- All Articles

- Latino Culture

- Black Voices

- Asian Stories

- Native Narratives

- LGBTQ+ Pride

- Best of Diverse Representation List

Celebrating Black History Month

Movies and TV Shows with Arab Leads

Celebrate Hip-Hop's 50th Anniversary

What is media literacy, and why is it important?

The word "literacy" usually describes the ability to read and write. Reading literacy and media literacy have a lot in common. Reading starts with recognizing letters. Pretty soon, readers can identify words -- and, most importantly, understand what those words mean. Readers then become writers. With more experience, readers and writers develop strong literacy skills. ( Learn specifically about news literacy .)

Media literacy is the ability to identify different types of media and understand the messages they're sending. Kids take in a huge amount of information from a wide array of sources, far beyond the traditional media (TV, radio, newspapers, and magazines) of most parents' youth. There are text messages, memes, viral videos, social media, video games, advertising, and more. But all media shares one thing: Someone created it. And it was created for a reason. Understanding that reason is the basis of media literacy. ( Learn how to use movies and TV to teach media literacy. )

The digital age has made it easy for anyone to create media . We don't always know who created something, why they made it, and whether it's credible. This makes media literacy tricky to learn and teach. Nonetheless, media literacy is an essential skill in the digital age.

Specifically, it helps kids:

Learn to think critically. As kids evaluate media, they decide whether the messages make sense, why certain information was included, what wasn't included, and what the key ideas are. They learn to use examples to support their opinions. Then they can make up their own minds about the information based on knowledge they already have.

Become a smart consumer of products and information. Media literacy helps kids learn how to determine whether something is credible. It also helps them determine the "persuasive intent" of advertising and resist the techniques marketers use to sell products.

Recognize point of view. Every creator has a perspective. Identifying an author's point of view helps kids appreciate different perspectives. It also helps put information in the context of what they already know -- or think they know.

Create media responsibly. Recognizing your own point of view, saying what you want to say how you want to say it, and understanding that your messages have an impact is key to effective communication.

Identify the role of media in our culture. From celebrity gossip to magazine covers to memes, media is telling us something, shaping our understanding of the world, and even compelling us to act or think in certain ways.

Understand the author's goal. What does the author want you to take away from a piece of media? Is it purely informative, is it trying to change your mind, or is it introducing you to new ideas you've never heard of? When kids understand what type of influence something has, they can make informed choices.

When teaching your kids media literacy , it's not so important for parents to tell kids whether something is "right." In fact, the process is more of an exchange of ideas. You'll probably end up learning as much from your kids as they learn from you.

Media literacy includes asking specific questions and backing up your opinions with examples. Following media-literacy steps allows you to learn for yourself what a given piece of media is, why it was made, and what you want to think about it.

Teaching kids media literacy as a sit-down lesson is not very effective; it's better incorporated into everyday activities . For example:

- With little kids, you can discuss things they're familiar with but may not pay much attention to. Examples include cereal commercials, food wrappers, and toy packages.

- With older kids, you can talk through media they enjoy and interact with. These include such things as YouTube videos , viral memes from the internet, and ads for video games.

Here are the key questions to ask when teaching kids media literacy :

- Who created this? Was it a company? Was it an individual? (If so, who?) Was it a comedian? Was it an artist? Was it an anonymous source? Why do you think that?

- Why did they make it? Was it to inform you of something that happened in the world (for example, a news story)? Was it to change your mind or behavior (an opinion essay or a how-to)? Was it to make you laugh (a funny meme)? Was it to get you to buy something (an ad)? Why do you think that?

- Who is the message for? Is it for kids? Grown-ups? Girls? Boys? People who share a particular interest? Why do you think that?

- What techniques are being used to make this message credible or believable? Does it have statistics from a reputable source? Does it contain quotes from a subject expert? Does it have an authoritative-sounding voice-over? Is there direct evidence of the assertions its making? Why do you think that?

- What details were left out, and why? Is the information balanced with different views -- or does it present only one side? Do you need more information to fully understand the message? Why do you think that?

- How did the message make you feel? Do you think others might feel the same way? Would everyone feel the same, or would certain people disagree with you? Why do you think that?

- As kids become more aware of and exposed to news and current events , you can apply media-literacy steps to radio, TV, and online information.

Common Sense Media offers the largest, most trusted library of independent age-based ratings and reviews. Our timely parenting advice supports families as they navigate the challenges and possibilities of raising kids in the digital age.

- Arts & Culture

- Civic Engagement

- Economic Development

- Environment

- Human Rights

- Social Services

- Water & Sanitation

- Foundations

- Nonprofits & NGOs

- Social Enterprise

- Collaboration

- Design Thinking

- Impact Investing

- Measurement & Evaluation

- Organizational Development

- Philanthropy & Funding

- Current Issue

- Sponsored Supplements

- Global Editions

- In-Depth Series

- Stanford PACS

- Submission Guidelines

Strengthen Media Literacy to Win the Fight Against Misinformation

If the world is going to stop deliberate or unintentional misinformation and its insidious effects, we need to radically expand and accelerate our counterattacks, particularly human-centered solutions focused on improving people's media and information literacy.

- order reprints

- related stories

By Kristin M. Lord & Katya Vogt Mar. 18, 2021

The deliberate or unintentional spread of misinformation, despite capturing widespread public attention, remains as rampant as ever, showing up recently in the form of false claims about COVID-19 vaccines , the Capitol riot , and many other topics . This “ infodemic ” is polarizing politics , endangering communities , weakening institutions , and leaving people unsure what to believe or whom to trust . It threatens the foundations of democratic governance , social cohesion , national security , and public health .

Misinformation is a long-term problem that demands long-term, sustainable solutions as well as short-term interventions. We've seen a number of quicker, technological fixes that improve the social media platforms that supply information. Companies like Facebook and Twitter, for example, have adjusted their algorithms or called out problematic content . We've also seen slower, human-centered approaches that make people smarter about the media they demand to access online. Evidence-driven educational programs, for instance, have made people better at discerning the reliability of information sources, distinguishing facts from opinions, resisting emotional manipulation, and being good digital citizens.

It hasn't been enough. If we're to stop misinformation and its insidious effects, we need to radically expand and accelerate our counterattacks. It will take all sectors of society: business, nonprofits, advocacy organizations, philanthropists, researchers, governments, and more. We also need to balance our efforts. For too long, too many resources and debates have focused on changing the technology, not educating people. This emphasis on the supply side of the problem without a similar investment in the demand side may be a less effective use of time and energy.

While technology-centered, self-policing solutions—filtering software, artificial intelligence, modified algorithms, and content labeling—do have the ability to make changes quickly and at scale, they face significant ethical, financial, logistical, and legal constraints.

Are you enjoying this article? Read more like this, plus SSIR's full archive of content, when you subscribe .

For one, social media business models thrive on engagement, which incentivizes emotionally charged and freely flowing content. Tech leaders like Facebook's founder, Mark Zuckerberg, hesitate taking action over concerns about free speech and have tried to avoid political debates until pressed . When they do take action, they face scrutiny for an inconsistent approach. Additionally, research shows that some of the most commonly employed methods for combatting misinformation on social media—such as banners that display fact-checks—have little impact on people’s likelihood to believe deliberately misleading news, and some even backfire. And because people often have a deeply held desire to share what they know with others—particularly information that seems threatening or exciting —tech companies can only go so far to regulate content. There is also the challenge of volume. Tech platforms struggle to keep pace with the many forms and producers of disinformation. Stopping them resembles a high-stakes, never-ending game of Whac-A-Mole.

Given these challenges, we need to invest more into human-centered solutions focused on improving people's media and information literacy. They not only demonstrate a much deeper and longer-lasting impact, but also may be easier and cheaper to implement than commonly believed.

Research from the RAND Corporation and others shows media and information literacy improves critical thinking , awareness of media bias , and the desire to consume quality news —all of which help beat back misinformation. Even brief exposure to some training can improve competencies in media literacy, including a better understanding of news credibility or a more robust ability to evaluate biases . Media literacy has a stronger impact than political knowledge on the ability to evaluate the accuracy of political messages, regardless of political opinion. Digital media literacy reduced the perceived accuracy of false news, and training remains effective when delivered in different ways and by different groups .

Media literacy training has lasting impact. A year and a half after adults went through a program from IREX (a nonprofit where the authors work), they continued to be 25 percent more likely to check multiple news sources and 13 percent more likely to discern between disinformation and a piece of objective reporting. In Jordan and Serbia, participants in IREX's training also improved their media literacy skills up to 97 percent .

Media literacy programs can also be affordably and extensively delivered through schools. Finland and Sweden incorporated media literacy into their education systems decades ago with positive results, and Ukraine is beginning to do the same . In Britain, youth who had training in schools showed an improvement in media literacy skills .

Critics may say that improving people's media literacy and other human-centered solutions are resource-intensive and will not address the problem quickly enough or at sufficient scale. These are real challenges, but the long-term efficacy of such programs is exactly what is needed in the never-ending battle with misinformation. We need to invest more in them while continuing to pursue technology solutions, or we may never create and sustain the accurately informed citizenry that healthy democracies demand.

The effort will require all sectors of societies across the globe collaborating to fully understand and solve the problem. We need nonprofits and advocacy organizations to raise the alarm with the people they serve. We need philanthropists to step up with funding to scale solutions. We need more researchers to provide evidence-based answers to the full scope of the problem and the efficacy of fixes. We need governments to integrate media literacy standards into schools and incentivize training. We need tech companies to do more than tweak their platforms—they need to invest in educating the people who use them, too.

The tools to blunt the power of misinformation are in our hands, but we have to work smarter and faster or risk losing an ever-intensifying fight. Much learning, coalition-building, scaling, and communication remains to be done to " emerge from information bankruptcy ." Solutions are complex but within our reach. And the consequences of inaction are dire: the increasingly severe and invasive destabilization of our societies and daily lives as lies trample the truth.

Support SSIR ’s coverage of cross-sector solutions to global challenges. Help us further the reach of innovative ideas. Donate today .

Read more stories by Kristin M. Lord & Katya Vogt .

SSIR.org and/or its third-party tools use cookies, which are necessary to its functioning and to our better understanding of user needs. By closing this banner, scrolling this page, clicking a link or continuing to otherwise browse this site, you agree to the use of cookies.

CURRICULUM, INSTRUCTION, AND PEDAGOGY article

Enhancing critical thinking skills and media literacy in initial vocational education and training via self-nudging: the contribution of nerdvet project.

- 1 Department of Human Science, University of Verona, Verona, Italy

- 2 ENAIP Veneto Foundation, Padova, Italy

Vocational Education and Training (VET) programs are fuelled by technical and practical educational modules. The teaching staff adopts both traditional and innovative pedagogical frameworks to increase the generalization and maintenance of practical skills. At the same time, VET teachers and trainers have a few occasions to promote and include disciplines and educational programs for enhancing students' soft skills, e.g., critical thinking skills (CT) and media literacy (ML). Following the European VET framework and literature of the field, CT and ML represent a social challenge that requires even more efforts by academics, practitioners, and policymakers. Thisstudy situates into this context with the aim of introducing a novel educational approach for supporting the teaching staff in the promotion of students' CT and ML. This educational approach has been realized by the team of researchers and trainers of the NERDVET project, an Erasmus+ KA3 project devoted to the promotion of new tools and policies for enhancing CT and ML in VET. To pursue this aim, the team has employed the self-nudging model which regards the individuals' set of cognitive and behavioral strategies that individuals can develop to target a specific objective. By framing pedagogical strategies into this perspective, the team realized an initial approach for educational activities and teaching strategies to promote students' CT and ML.

Introduction

Vocational education and training (VET) programs aim at equipping students and learners with a supply of technical and practical skills aligned with the labor market's needs. This is notable not only in VET pedagogical frameworks, and in the choice of educational modules of VET providers, but also more institutionally in normative definitions and operationalization of VET centers. This is due to the nature of the purpose of VET to equip students with skills as the glue in between the new workforce and the productivity of specific working sectors. The transformations concerning the labor market underline that the labor market benefits more from the VET sector than other educational pathways. However, this entails that the promotion of technical and practical skills can be insufficient with respect to the promotion of additional skills, e.g., critical thinking skills and media literacy. Focusing more on technical skills at the expense of metacognitive skills may compromise individuals' citizenship behavior ( Pfaff-Rüdiger and Riesmeyer, 2016 ; Tommasi et al., 2021a ; Perini et al., 2022 ). The lack of educational models for the promotion of metacognitive competences in VET-led scholarly authors, practitioners, and policymakers to move toward the creation of pathways aimed at the development of these specific components. For example, the European Union (EU) has made skills like critical thinking and media literacy key objectives for the education and training sectors. Following this trend, the EU countries and the European Commission (EC) have used and financed multiple initiatives (e.g., Erasmus+, the Connecting Europe Facility, ( European Commission, 2020b )).

It is in this context that the Think smart! Enhancing critical thinking skills and media literacy in VET (NERDVET, n.d.) project, an Erasmus+ KA3 project co-funded by the European Commission 1 , takes place with the proposition of developing a novel educational program to support VET teaching staff in increasing CT and ML skills of their students. The NERDVET educational program is based on different techniques, among which a novel concept of self-nudging has been developed: according to this new self-nudging concept, teachers and trainers can foster students' capacity to create a set of specific personal strategies to reach a target or to tailor their behavior for a proactive purpose, e.g., behaving critically in a digital environment. Through self-nudging, it is possible to develop the proactive commitment of individuals in the processing of information, also aiming at supporting the creation of specific individuals' strategies to critically evaluate information and adopt a specific behavior.

The aim of this study is to present the NERDVET proposal to use the self-nudging model for enhancing students' critical thinking skills and media literacy. At the base (i.e., ontologically, Creswell, 2014 ), critical thinking and media literacy represent two linked metacognitive competences. On the one hand, critical thinking is a metacognitive competence concerning the knowledge and skills of reflection, analysis, and questioning of information, which results in proactive and citizenship behavior. On the other hand, media literacy as a metacognitive competence includes the knowledge and skills to think critically about media information through understanding media representations, structures, and implications ( Tommasi et al., 2021a ). Studying critical thinking and media literacy via a psychological (behavioral-cognitive) approach finds a connection with the notion of self-nudging, that is the individuals' own set of metacognitive strategies to pursue personal targets ( Hertwig and Grüne-Yanoff, 2017 ; Torma et al., 2018 ). With this framework, we propose indications of possible ways through which teachers and trainers can enhance critical thinking and media literacy among VET students. Our indications serve to create the basis for realizing learning strategies to be implemented within the classroom. Ultimately, this proposal covers both the theoretical background and educational suggestions on implementing exercises whose purpose is the development of these metacognitive competences.

In the following sections, we will first report the current trends for the enhancement of CT and ML in the context of VET. Given the area of intervention of the NERDVET project, we will focus on the European trends for the enhancement of CT and ML in the VET context. Then, we will introduce how CT and ML are considered at the academic level. Here, we will report the definitions of CT and ML as well as an overview of the practices for the enhancement of CT and ML in VET. Second, considering these pieces of knowledge as a reference framework, we will report the self-nudging approach for the implementation of training techniques in the context of VET. We will refer to the ontological similarities between the notions of critical thinking, media literacy, and self-nudging theory to propose a novel approach serving learning strategies within the classroom. Lastly, we will end the discussion of the NERDVET approach for the enhancement of CT and ML by presenting the direct users and beneficiaries of this novel approach for training VET students.

Approaches to critical thinking and media literacy

European trends for the enhancement in the vet context.

The integration of CT and ML in VET curricula is still very scant at the European level, although some preliminary initiatives have been carried out successfully in the last few years. The European institutions have introduced several policies and financial initiatives to support the goal of enhancing CT and ML in the context of vocational training, especially following the COVID-19 outbreak. This is the case of the EC Recommendation on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning, which has outlined a set of eight competencies that all individuals need for personal fulfillment and development, active citizenship, social inclusion, and employment. Similarly, the New Skills Agenda for Europe highlights 10 actions to make relevant training, skills, and support available to EU citizens. The European Trend 2020 strategic framework promotes peer learning, including through the collection and dissemination of good practices in the field of CT and ML, while paying special attention to effectively reaching out to disadvantaged learners and those at risk of marginalization. Also, the Commission's Digital Education Action Plan contains 11 actions to make better use of digital technology for teaching, learning, and developing digital competencies, based on the precondition that digital competence includes the confident, creative, and critical use of information and communications technology, which is also considered a crucial component of media literacy. To promote ML and CT, EU funds and programs, such as Erasmus+, the Connecting Europe Facility, the European Structural and Investment Funds, Horizon 2020, Creative Europe and Europe for Citizens, have been utilized by EU countries and the EC. Overall, experts in the field (e.g., policymakers, practitioners, and researchers) agree on the fact that “critical thinking is a widely accepted educational goal […] and its adoption as an educational goal has been recommended based on respect for students' autonomy and preparing students for success in life and democratic citizenship” ( Hitchcock, 2018 ).

In contrast to this background, in the VET sector, there is little to no integration of critical thinking skills and media literacy within VET curricula or competence standards. In contrast to other countries ( Decreto 220, 1998 ; Decreto 254, 2009 ; Australian Government Department of Education Training, 2016 ), VET curricula at the European level rarely contemplate systematic or integrated teaching of critical thinking either as specific content or as a transversal one ( European Commission, 2020a ). The organization of teaching sessions devoted to the development of such competences for students is thus left to VET schools, which–however–do not often have the means and opportunity to do so. Although some transversal skills related to critical thinking are embedded in different subjects and skills, they are neither sufficiently highlighted nor presented in a structured form. The largest part of learning projects remains grounded in implementations meant as a singular intervention and, even when it is not so, it tends to focus exclusively on specific aspects of critical thinking and media literacy. Quite often, these aspects are not treated in an integrated way, but their focus depends on the specific purpose of the project or lesson being carried out ( Bergstrom et al., 2018 ).

Overview of reference definitions and current practices

Notwithstanding the institutional context, academics in the field of VET have produced several contributions to CT and ML in recent years. The term critical thinking regards the human metacognitive ability to think clearly and rationally about something. Through critical thinking, individuals can (a) understand logical connections between ideas, (b) identify and evaluate arguments, (c) detect inconsistencies and common mistakes in reasoning and (d) achieve other fundamental aspects (e.g., daily decision-making process) ( Kenyon, 2014 ; Bergstrom et al., 2018 ; Tommasi et al., 2021a , b ). Critical thinking is also crucial to moving through the wide world of news that we read every day and avoiding judgment errors ( Ceschi et al., 2019 ; Ceschi and Fioretti, 2021 ; Tommasi et al., 2021a , b , c ). It also helps us to judge and understand a lot of aspects of what we read in the media. In this context, critical thinking is viewed at the same level of optimal decision-making competence which relates to the ability to avoid cognitive errors and the use of heuristics ( Kenyon, 2014 ). Moreover, it is also an antecedent of positive social skills to critical thinking with issues such as body image, racial stereotypes, and gender ( Bergstrom et al., 2018 ).

As for other terms such as information and digital abilities ( Bolaños Cerda et al., 2020 ; Bolaños and Pilerot, 2021 ), media literacy is also characterized by terminological ambiguity as it has been discussed in a plurality of different forms with multiple arguments on how to improve it ( van Laar et al., 2017 ; Bolaños et al., 2022 ). This partially reflects the lack of consensus on how to enhance media literacy among VET students, namely how to define media literacy in such context and to consider it in line with critical thinking. Arguments have been proposed that media literacy is linked to the notion of critical thinking and regards the ability to identify different types of media and understand the messages they are sending. Media literacy represents a core characteristic of citizenship behavior as well as an indispensable aspect for dealing with the huge amount of information presented in different shapes. Despite the agreement on its importance, authors reported different definitions and attributes of what media literacy means, such as the ability to critically access, analyze, evaluate, and create media messages ( Banerjee et al., 2015 ; Schilder and Redmond, 2019 ). Other authors considered media literacy as the cognitive awareness of the importance of media messages and their impact on the public. Such awareness is meant to foster individuals' responsibility to critically evaluate media messages ( Geers et al., 2020 ). Moreover, other authors considered media literacy as the ability to reach and understand the information within the media context, although the authors did not provide a clear idea about how such a process is sustained ( Cohen and Mihailidis, 2013 ). In particular, they support the idea that individuals can make meaning of the contents and enhance their ability to make decisions.

However, there is still a certain degree of uncertainty concerning the agreement on what could be done to support teaching staff in the promotion of CT and ML in VET students. With respect to these, there are different ways of approaching CT and ML in VET. Some authors refer to the model of social interactions as a learning process to promote these competences ( Bandura, 1986 ). This theory has been used to support the idea that CT and ML, as learning processes, may be the result of the vision and interaction between students and teachers ( Banerjee et al., 2015 ). Other authors propose a broad social view of the importance of CT and ML, using the human capital theory model to sustain the need to actualize educational models on CT and ML in the context of VET ( Edokpolor and Abusomwan, 2019 ). Similarly, others refer to Watson and Glaser (2002) model to argue that the promotion of critical thinking and media literacy is a consequence of a greater sense of belonging among students and, if promoted, also better active citizenship. Finally, through a cognitive approach, other authors use cognitive psychology models of the so-called debiasing as an intervention tool for the promotion of critical thinking and media literacy in the context of Initial VET (iVET) and citizenship behavior through teaching error recognition and cognitive distortions ( Kenyon, 2014 ).

Such uncertainty is due to the multiplicity and complexity of factors interviewing on CT and ML, which makes it even more difficult to realize effective educational models for their promotion. Reviewing the literature in the field, Tommasi et al. (2021a) argued that there is a wide range of relevant factors for students, teachers, group-class, and communities that scholarly authors have been considering to propose training interventions. These include teaching techniques that, through stimulating reflectiveness, can help promote critical thinking and media literacy, also beyond the iVET context. Although there is not vast literature in this regard, this literature review suggests the existence of possible strategies which allow for improving individuals' disposal, personal resources, and reducing biases and cognitive prejudices ( Noorani et al., 2019 ). In this regard, the teacher's role becomes crucial because they are called to set up the right conditions in the learning contexts to enhance those metacognitive skills. It is important to give appropriate input and tools that can support these processes to offer students the chance to keep implementing those metacognitive competences through personal and self-developed stimuli. Teachers may use significant samples, combined with the possible specific contextualization, to foster the comprehension of the consequent benefits of applying critical thinking and media literacy. In addition, this contribution aims to suggest learning practices and cues for personalizing the interventions toward the enhancement of critical thinking and media literacy in the context of iVET. This entails the importance of focusing on the individual and the comprehension of where to apply those skills in their specific situations.

The NERDVET approach

Considering the very definitions and practices ( Tommasi et al., 2021a ), and the very institutional approaches as well, these can be interpreted through a behavioral-cognitive psychology approach and in particular via nudging and self-nudging models. At the base (i.e., ontologically, Creswell, 2014 ), critical thinking skills and media literacy regard how individuals understand information and concepts as well as promote specific cognitive and behavioral strategies. This echoes both the theoretical and empirical knowledge of the bunch of psychology and behavioral sciences devoted to the study of the human decision-making process ( Cohen and Jaffray, 1980 ; Bell et al., 1988 ). In this, scholars have proposed an approach aiming to make ideal normative decision-makers, considering their cognitive limitations and trying to help them through the implementation of particularly difficult tasks and operations as a reframing action ( Baron, 2000 ). Accordingly, individuals would be equipped with a set of logical abilities linked thanks to their reflective abilities in problem-solving activities, and their comprehension of the causes and effects of possible flawed choices. Trainers are asked to support the decision-making process of individuals with methods that help to reduce or eradicate errors. For example, the observation of commonly used reactions that are inconsistent with certain information for problem-solving can be considered to think more deeply about these inconsistencies, i.e., heuristics and biases, and foster critical thinking ( Cohen and Jaffray, 1980 ; Bell et al., 1988 ).

Practically (e.g., epistemologically, Creswell, 2014 ), behavior economy and cognitive psychology propose training techniques are meant to remove the occurrences of mistakes for decision-making process optimization. The underlying idea of this method is to work with individuals' common cognitive errors indicating logical inconsistencies and inconsistent perceptions of reality (Gerling, 2009). Bias removal (Debiasing) programmers are similar to the prescriptive method and the use of reminders, such as warning individuals to consider the base rate of success in the workplace before concluding. Different problems offered by Soll et al. (2014) include training programs in which students share professional experiences about overwhelming errors (to correct underestimation of rare events) and providing new tips and methods for trained employees to critique. Nudging and self-nudging approaches serve for interpreting the multiplicity of these perspectives for the realization of an educational toolkit for enhancing CT and ML in VET students. In this framework, the urgency is to (a) supporting the use of specific procedures to understand whether the information is fake or real; (b) enhancing the awareness of cognitive errors (e.g., cognitive biases) supporting the idea that all people can be irrational, as irrationality is embedded in humans but it can be reduced by the awareness of biases; (c) enhancing the individuals' tools to develop personal skills and procedural activities to address information.

Self-nudging

The NERDVET community builds up on these previous ontological and epistemological interpretations ( Creswell, 2014 ) and refers to the notion of self-nudging as a general behavioral-cognitive process which can be supported among individuals to help them to reach their targets. The self-nudging is a novel notion whose roots are in the nudge theory. This latter is defined as a strategy to design individuals' choice environments, guiding their behavior to increase wellbeing and work efficacy, productivity, and social engagement ( Johnson et al., 2012 ; Lehner et al., 2016 ). The impact of nudges is widely recognized, and authors are even more supportive of the idea that individuals can create a simple set of nudges that can be used to apply specific reasoning and behaviors ( Thaler and Sunstein, 2008 ). The self-nudging concept instead is based on the idea of autonomous implementation of nudges, which are non-regulatory and non-monetary strategies that may change the choice architecture to target behavior in a predictable way, toward their ultimate goals, without eliminating any options or significantly changing personal incentives ( Thaler and Sunstein, 2008 ). Nudges are aids or signals that individuals experience all the time: some are designed to initiate or shape new behaviors; others can be used to provide information or guide thinking. In turn, self-nudging is a behavioral science strategy that focuses on individuals' capacity to define a set of strategies to improve their self-control. The idea behind self-nudging is that people can design and structure their environments in ways that make it easier for them to make the right choices and also to reach long-term goals. Also, self-nudging requires consciousness about a connection between one's behavior and the environment's architecture, as well as knowledge of a procedure that can help to modify that connection ( Torma et al., 2018 ).

Considering the congruency of the understanding of CT and ML as two interconnected metacognitive competences ( Tommasi et al., 2021a ) while assuming the orientation of the self-nudging approach to developing an individual set of behavioral-cognitive strategies ( Torma et al., 2018 ), training bases on eliciting the application of proactive engagement in information processing and also supporting the creation of specific individuals' strategies for critically assessing external information and personal reasoning ( Hertwig and Grüne-Yanoff, 2017 ). By facilitating the use of self-nudge, people have the opportunity, through adequate training, to become architects of their own choices in a fully conscious way. For this reason, it becomes necessary to address people on the causes related to probable behavioral problems and on how to deal with them. According, behavioral researchers are often called to contribute to the change process, but at the same time, they are limited in how they can modify the underlying environment or the entire chosen architecture. Often, they try to push in the context of complex systems in which they can at the most change behavior in a marginal way. Therefore, moving on to reducing “sludge,” like eliminating obstacles that make decision-making difficult, could be more productive, which is indeed the idea behind self-nudging training.

Self-nudging for CT and ML in VET

By raising awareness about individuals' social responsibility, it becomes possible to improve responsible thinking, critical interpretation, and information comprehension. In an educational context, nudges can thus help increase motivation in students, and encourage them to become more interested and involved in the proposed initiatives; moreover, highly motivated peers contribute to promoting the quality of support and discussion between subjects ( Ebert and Freibichler, 2017 ).

According to this definition, a key factor to enhance CT and ML in VET students is identifying which are the learning purposes associated with self-nudging. Specifically, interventions are meant to develop in subjects the competence to autonomously create nudges for the self, addressed to social responsibility. A significant aspect of this process is the maintenance of motivation, which may aid the growth of critical thinking and media literacy. Another relevant factor is the ability of teachers and trainers of managing to influence the habits of students regarding comprehension and interpretation of information. Those who work in these contexts should pay great attention and provide constant support to any thinking process and proactive behavior.

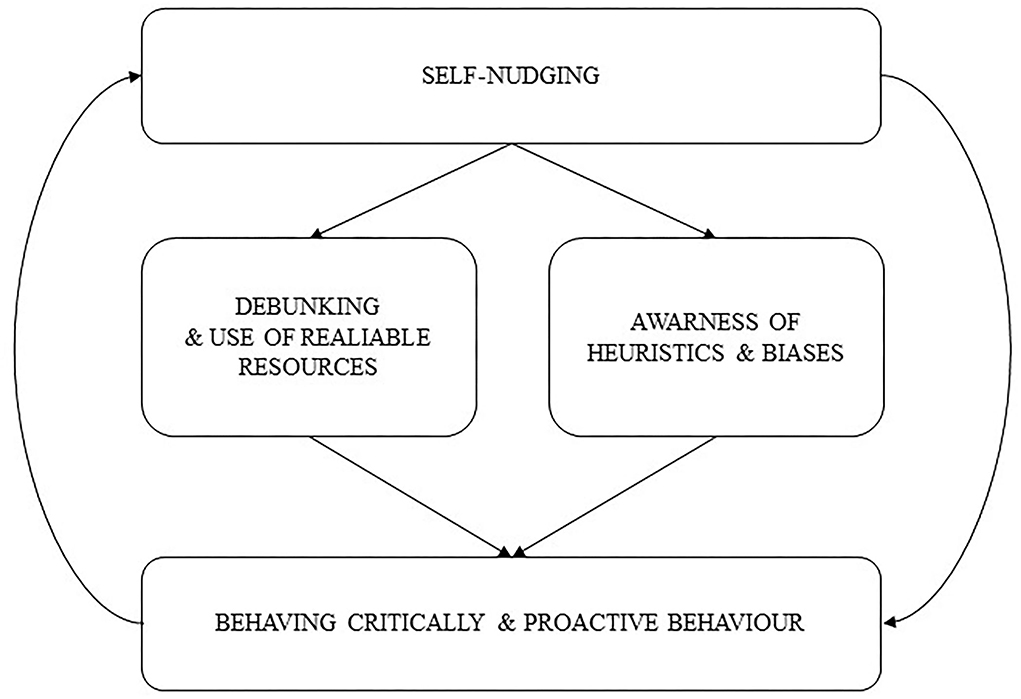

In this framework, we propose that to enhance CT and ML, the teaching staff can follow the self-nudging circuit of behaving and thinking critically ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1 . Self-nudging circuit of behaving and thinking critically.

The focus is on eliciting the application of CT and ML by supporting students' proactive engagement in information processing and supporting the creation of specific individuals' strategies for critically assessing information and adopting informed behavior. Teachers and trainers represent one of the key elements for students' creation of their cognitive-behavioral strategies. Thus, the circuit comprehends students' ability to understand the role of personal nudges (cognitive strategies) via which activating self-nudging activities influence their behavior. That is, self-nudging as an individual approach to CT and ML leads students to behave critically in a proactive way. In turn, behaving critically and proactively leads to strengthening one's strategies (personal nudges) as well as creating new ones. As noted, individuals can themselves create a simple set of nudges that can be used to apply specific reasoning and behaviors ( Thaler and Sunstein, 2008 ).

Self-nudging techniques

In the digital era, the problem of fake news affects both the quantitative and qualitative aspects of the information environments. The challenge of recognizing fake news worldwide can be addressed by developing learners' ability to evaluate and chose better sources of information. In these terms, self-nudging can focus on supporting the use of debunking strategies and the use of reliable sources. This means teaching students how to understand whether the information is fake or real by enhancing their awareness of the relevance of the sources. Thus, teachers can help students to realize specific strategies to control the source of data in reading and choosing information. An efficient way for developing these self-nudging strategies can be supporting the use of debunking by providing resources for students to debunk, such as a guide on how to flag suspicious stories on social media networks and a list of websites that have carried false or satirical articles. Alongside, this approach should also include training on the use of reliable sources, which means teaching students how and to what extent sources of information matter and how to find good sources.

To behave and think critically, individuals also need to avoid their prejudices and irrational beliefs, which may be due to the use of specific cognitive shortcuts, i.e., heuristics and biases. In these terms, the main aspect of reducing the incidence of cognitive biases and prejudices (i.e., irrational beliefs) is to develop awareness about them. Teaching people what cognitive biases are, how to recognize them, and what their effects can be, help reduce their incidence but also, in the view of self-nudging, help support the creation of specific strategies to avoid their use in fast reasoning. As already mentioned, CT is also related to addressing irrational beliefs (i.e., stimulating emotional strategies), which are usually connected to prejudice and emotional judgments ( Kahneman, 2003 ). Applying self-nudging to counter bad heuristics processes could result in both stopping them and creating good ones: in this context, some examples of nudges could be forcing oneself to consider more options, using checklists, activating reminders, and learning to practice rewording in the presence of ambiguous information ( Orosz et al., 2016 ).

Finally, another relevant aspect related to CT is the ability to break down information or problems to solve a small problem or analyze a simpler piece of information at a time. Using self-nudging in this framework would mean helping people to foster their abilities to practice continuous but simpler problem-solving and to constantly check their activities against a prior detailed plan they had formulated.

Direct users and beneficiaries

Following our model, teachers and trainers represent one of the key targets as direct users of the NERDVET approach. The contemporary setup of VET contexts underlines (a) the need for VET teachers and trainers to equip students with critical thinking skills and media literacy as well as (b) the lack of formal training paths on the identified topics, thus supporting teachers and trainers in empowering students to become the future generation of EU citizens. The role teachers and trainers can play has crucial importance as long as they are (1) better equipped and trained, (2) well-aware of the direct benefits for and impact on students, (3) capitalizing on the expertise developed at the European and national levels by other VET peers, having direct access to successful practices and teaching and training methods.

Furthermore, the upskilling proposal is expected to have a direct impact on iVET students as beneficiaries of the NERDVET approach. Motivation and active engagement are two key factors for a successful teaching and learning process, especially in the iVET sector where major challenges derive from the disadvantaged socioeconomic background owned by students. In fact, these pre-conditions affect not only students' performance but also their willingness to contribute to the overall learning process proposed by teachers and trainers. Following a motivational-oriented approach and applying active teaching methods, the target is to put students at the very center of the learning process with a double scope: (1) to equip iVET students with both technical and soft skills that are considered crucial to entering the labor market, (2) to allow teachers or trainers to be perceived as proactive actors–mentors and not as mere instructors–who are capable to turn teaching into a mutual learning process, where dialogue and support pave the way for students' personal and professional development.

Evaluating the NERDVET approach

The NERDVET project is administrated by teachers and researchers to propose forward normative instruments and projects characterized by high effectiveness to promote students learning. Hence, the evaluation of the NERDVET approach should focus on the outcomes of students and teachers involved in the training activities. A valuable pathway for the evaluation of the effectiveness of the NERDVET approach to enhance CT and ML should be based on the use of mix-methods involving qualitative interviews and quantitative instruments for students' performance assessment ( Sartori and Ceschi, 2013 ; Creswell, 2014 ). First, a qualitative evaluation approach could be based on Vergani's (2004) core-methodological perspective. Vergani proposed a system of qualitative evaluation based on viewing the prospects of participants in training activities and creating the evaluation system itself. He suggested considering the point of view of the evaluated rather than applying a standardized system and making inferences on the effectiveness of the training programs (2004). By the explicit comparison between all the data collected, i.e., documents, and interviews, the evaluation of a training project can emerge and core aspects of the students' competence development. Hence, researchers could collect qualitative data after the training in class and in the workplace using interviews coupled with document analysis. Students and teachers can be interviewed with a semi-structured questionnaire about their experience in the study. Moreover, qualitative methods aim to understand the features of the project as a result of the experiential contents, and the comparison with the documents made by teachers and authorities involved.

Second, quantitative methods can be used to assess students' and teachers' competence development ( Sartori et al., 2015 ). To pursue this aim, researchers can develop a new self-report questionnaire for teachers and students. We suggest the use of a self-evaluation tool for allowing teachers and trainers to verify their level of CT-ML, whether there is room for improvement, and whether the task was effective for the learning process. Results would be easily interpreted by looking at the range of the answers by assessing students before and after training to have a quantitative indication of their improvement in CT and ML.

We proposed this contribution to offer initial suggestions on the possibility of applying a novel educational approach. This limits this work to a mere presentation of the state of the art of literature on CT and ML in the context of VET, and the self-nudging approach realized by the NERDVET project. In this framework, our ultimate aim is to offer a link between the social need for the promotion of CT and ML and the progress of research in cognitive-behavioral psychology. Considering the actual limitations in promoting CT and ML in the VET world, this work represents the first step, by setting a theoretical approach that can be further developed and implemented in educational programs. Indeed, the present contribution contains both a terminological orientation and a general depiction of the possibilities of using self-nudging in VET for promoting CT and ML. Future applied research activities may use this work as a starting point to devise training interventions. Similarly, this study can lead to realizing policy recommendations and novel educational frameworks in the field of VET.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

FT and RS are responsible for the title, the abstract, the general idea of the paper, and wrote the manuscript. FT, RS, AC, and MF developed the concept behind the manuscript. SG and SB provided the literature sources and contributed to the design of the model. AC, MF, SG, and SB edited the final version of the manuscript. MF is, in particular, responsible for the introduction and the conclusion. All authors contributed to the elaboration of the concept to a publishable topic, have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Authors' work on this paper was supported by of the European Union funding for the project NERDVET, ERASMUS + KA3 - Support for Policy Reform, Social inclusion through education, training, and youth.

Acknowledgments

We gladly acknowledge the NERDVET project's partners, who envisioned the study of critical thinking and media literacy in the context of iVET, as they have contributed to the development of this study. They are representative of the following VET centers in Europe: ENAIP NET (Italy), Centro San Viator (Spain), Stichting Clusius College (The Netherlands), INOVINTER (Portugal), and American Farm School (Greece). We particularly thank Alfredo Garmendia, Ainhoa De La Cruz, Lara Meijer, Ryanne Sandstra, Clara Bovenberg, Yrina Res-Drost, Susanne Libbenga, Paula Cristina Soares Pedro, Susana Isabel Rodrigues Casimiro, Stavroula Antonopoulou, and Erikaiti Fintzou for their comments and discussions on our study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^ NERDVET - Think smart! Enhancing critical thinking skills and media literacy in VET - Project no. 621537-EPP-1-2020-1-IT-EPPKA3-IPI-SOC-IN | Erasmus+ KA3 - Support for policy reform - Call EACEA/34/2019. Website: https://www.nerdvet.eu/ .

Australian Government Department of Education Training (2016). Fact Sheet Foundation Skills . Available online at: https://www.myskills.gov.au/media/1777/back-to-basics-foundation-skills.pdf (accessed February 2, 2022).

Google Scholar

Bandura, A. (1986). Social Foundations of Thought and Action . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Sage. 23–28.

Banerjee, A., Duflo, E., Glennerster, R., and Kinnan, C. (2015). The miracle of microfinance? Evidence from a randomized evaluation. Ame. Econ. J. Appl. Econ. 7, 22–53. doi: 10.1257/app.20130533

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Baron, J. (2000). Thinking and Deciding . Cambridge University Press.

Bell, D. E., Raiffa, H., and Tversky, A. (1988). Decision Making: Descriptive, Normative, and Prescriptive Interactions . Cambridge University Press.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Bergstrom, A. M., Flynn, M., and Craig, C. (2018). Deconstructing media in the college classroom: a longitudinal critical media literacy intervention. J. Media Lit. Educ. 10, 113–131. doi: 10.23860/JMLE-2018-10-03-07

Bolaños Cerda, I., Hernández Pinell, D., Cisneros López, R. M., and Esquivel Zelaya, G. (2020). Turismo, una alternativa de desarrollo local con enfoque de g?nero . Caso de estudio: La Garita-Salinas Grandes, León, Nicaragua.

Bolaños, F., and Pilerot, O. (2021). Digital abilities, between instrumentalization and empowerment: a discourse analysis of chilean secondary technical and vocational public policy documents. J. Vocat. Educ. Train . 1–20. doi: 10.1080/13636820.2021.1973542

Bolaños, F., Salinas, A., and Pilerot, O. (2022). Instructional techniques and tools reported as being used by teachers within empirical research focusing on in-class digital ability development: a literature review. J. Comput. Educ . (2022). doi: 10.1007/s40692-022-00222-2