Intercultural Awareness and Multicultural Society in a Global Village Essay

Introduction, intercultural perspective, advantages of intercultural communication.

Culture implies different things to different groups. For example, anthropologists define culture as the way people live. Others define it as the system that incorporates the biological and technical behaviors of community within their verbal and nonverbal systems.

NASW (2001) defined culture as “the integrated pattern of human behavior that includes thoughts, communication, actions, customs, beliefs, values; and the institutions of a racial, ethnic, religious or social group” (NASW, 2001, 1).

It is the totality of behavior passed from one generation to the other. Intercultural awareness campaigns try to figure out how people understand each other irrespective of their cultural differences (NASW 2000). 21 st century living is described as a multicultural society in a global village.

Therefore, one may ask, what kind of communication and interactions are required to create a climate of respect, diversity tolerance with unified common goals? More so, one may wish to find out whether it is possible for neighbors to embrace their cultural differences (NASW, 2007).

Bennet outlined a great scenario on how a group of primates gathered around a bonfire would fight or take off on the sight of another group of primates heading to their fire place. This is exactly how it happens even to the more advanced primates Homo sapiens.

Arguably, our ancestors avoided people from other cultures in the best way they could. If all measures to avoid their interactions were unsuccessful, they opted for other measures such as converting them into their way of life.

Those who became stubborn to assimilations were ripped out of existence through killing; there is evidence of genocide from the history. Therefore, dealing with cultural differences, understanding it, embracing it and respecting it is vital to intercultural awareness and especially communication (Bennet 1998).

Understanding objective culture is very different to understanding a foreign culture. There exist perspectives, which view that learning about other cultures, their social, economic, political way of life, their linguistics, arts and so forth are sufficient to understand culture.

However, there are professors, in such sectors as linguistics, who still are unable to communicate with people from that particular community irrespective of how broad their knowledge is. Understanding objective culture merely adds knowledge about the foreign culture but does not generate much cultural competence.

On the other hand, understanding phenomenological features that define a group, and the way the group reasons and behaves will mark a step to identifying with the culture of that group. It is defined as subjective culture.

Subjective culture is defined by Bennet (1998) as “the learned and shared patterns of beliefs, behaviors, and values of groups of interacting people” (p. 1). This type of perspective is said to be more likely to lead to intercultural competence. However, it requires understanding objective culture to understand subjective culture and to have social reality (Bennet 1998).

Many people ignore the advantages of cultural orientation. Most of them, view intercultural communication as the grammatical rules applied in spoken and written practices.

To some, learning about cultural practices poses a threat to their values. Some of the non verbal perspectives of communication from various cultures are picked from TV programs and movies, which have very little for communication purposes or, which may be of faulty conceptions (Bennet 1998).

Another problem with cultural perspectives is stereotyping and generalization. For example, it is very common to take notice of people discussing that a certain lady is not behaving like a Latin woman and so forth. This is so especially with the Arabic culture and Islam where gender roles are strictly divided.

It is hard to find women from such communities in leading positions in politics or other fields. Stereotypes occur when behavioral assumptions are held by all members of a particular culture as shared traits. Such characteristics assumedly common can be respected by the observer (positive stereotype) or be disrespected (negative stereotype).

Either of the stereotypes is negative in intercultural communication because they often give false conceptions regarding the community or have partial truth in them. Secondly, stereotyping is an act of encouraging prejudice among the cultures.

However, it is important for a culture to develop identity to make a cultural generalization. Assuming that each person is an individual may lead to naive individualism (Martin & Nakayama 1997).

Intercultural communication focuses on interaction in human beings through giving and receiving processes. Intercultural communication emphasizes on learning about one or more cultures in addition to one’s own culture. This way, it helps in understanding importance of interculturalism.

It offers a better way to analyze interactions to enable great adoption (Bennet, 1998). From my perspective, the course supports the existence of unity, cooperation and creative conflict between multicultural societies simultaneously. This way, it renders a platform for our differences and their uniqueness be felt in synergistic harmony.

Intercultural communication and awareness are equally important in the workplace. With the current market globalization, fields like hospitality, tourism, commerce and research have to acknowledge the importance of intercultural differences and mould the diversification into unified goals.

The increasing globalization and thus diversity of the workforce implies that ignoring cultural diversity in the organization can no longer be ignored. The reasons for heterogeneity in behaviors at our places of work are fully attributed to the cultural diversity (Lum 2007).

Therefore, it is up to the management to identify courses that could match the intercultural variations at the place of work. According to Devine, Baum, & Hearns (1999), management of diversity in the workforce implies understanding the diversified population and understanding the concepts of diversity that can be visible and non visible including sex, age, background, personality, disability and work style.

Proper harnessing of such differences implies creation of productive working environment where every body feels valued and where the potential talents can be utilized fully to meet the organization goals (Devine, Baum, & Hearns 1999).

Therefore, it is important to integrate intercultural communication in the curriculum to help the students understand and differentiate between cultural norms, beliefs and habits in a society and possible deviations of such norms in a society. This can be achieved by allowing students to share their native cultures with their foreign colleagues.

Restrictions should be limited by allowing use of student’s native language where necessary. In this manner, there will be a development of social-cultural awareness and social linguistic presence among the students in addition to their native language and way of life.

Espousing intercultural communication is not necessarily implying that one is changing their cultural identity. Their ethnicity, religion and political backgrounds remain solidly unaffected.

Cakir (2006) has claimed that, “students use English well and get acknowledged, but in doing so, it does not imply they are changing their identity. There is no need to become British or American in order to use English well” (p. 12).

Bennet, MJ 1998, Basic concepts of intercultural communication: Selected readings Intercultural communication: A current perspective, Intercultural Press, New York.

Cakir, I 2006, ‘Developing cultural awareness in foreign language teaching’, Turkish online Journal of distance Education , vol. 7, no. 3, p. 12.

Devine, F, Baum, T & Hearns, N 1999, Resource guide: Cultural Awareness for hospitality and tourism. Web.

Lum, D 2010, C ulturally competent Practice: A Framework for Understanding Diverse and Justice Issues , Cengage Learning, New York.

Martin, J & Nakayama, T 1997, Intercultural communication in contexts, Mayfield publishing, Mountain view.

NASW 2000, Cultural competence in the social work profession, NASW press, Washington DC.

NASW 2001, NASW stands for cultural competence in social cork practice. Web.

NASW 2007, Indicators for the Achievement of the NASW standards for cultural competence. Web.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2024, February 1). Intercultural Awareness and Multicultural Society in a Global Village. https://ivypanda.com/essays/intercultural-awareness/

"Intercultural Awareness and Multicultural Society in a Global Village." IvyPanda , 1 Feb. 2024, ivypanda.com/essays/intercultural-awareness/.

IvyPanda . (2024) 'Intercultural Awareness and Multicultural Society in a Global Village'. 1 February.

IvyPanda . 2024. "Intercultural Awareness and Multicultural Society in a Global Village." February 1, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/intercultural-awareness/.

1. IvyPanda . "Intercultural Awareness and Multicultural Society in a Global Village." February 1, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/intercultural-awareness/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Intercultural Awareness and Multicultural Society in a Global Village." February 1, 2024. https://ivypanda.com/essays/intercultural-awareness/.

- The Origin of Man and Primates' Evolution

- Characteristics of the Order Primate

- Nonhuman Primate Conservation: Is It Possible?

- Primate Observation Paper

- Primate Evolutionary Context

- The Behavior of Human Beings and Nonhuman Primates

- Vocal Communications of Humans and Nonhuman Primates

- Male Infanticide and Female Countermeasures in Nonhuman Primates

- Sexual Receptivity explained using a Study on Primate Female Sexuality

- Evolution: Primate Locomotion and Body Configuration

- Essay About Gifted and Talented Students

- Curriculum Development: Understanding Rubrics

- Career Exploration and Awareness Education

- Early Childhood Education and Special Education

- Three Things You Can Do to Help Your Child Do Better in School

What is intercultural awareness and how to develop it

- Redaction Team

- September 10, 2022

- Professional Career , Professional Development

As the world becomes more interconected than ever, and societies have the ease of contacting people from all around the world in a matter of seconds, it is important to understand the similarities and differences that exist between cultures.

Key values that are needed to be promoted are tolerance and respect, specially when people from other countries have a different set of opinions.

No, there is no perfect country, nor society, but what it makes a better global society is the understanding of each other position and merge what it is the best of both communities.

Regardless of the cultural differences, languages spoken, characteristics, behaviours, religious backgrounds and belief, what makes it possible to manage intercultural relationships is an open attitude towards a positive interaction.

Following up, we will discuss more about intercultural awareness and its development.

What is intercultural awareness?

Intercultural awareness is the ability to understand and appreciate the differences between cultures.

It involves understanding how cultures are similar and how they are different, and being able to effectively communicate with people from other cultures.

Intercultural awareness can contribute to effective communication in several ways.

First, it can teach people to understand, acknowledge and appreciate the perspectives of others.

Second, it can help people to avoid stereotypes and misunderstandings that might come across.

Third, it can help people to build rapport, agreement, appreciation and trust.

Finally, it can support people to resolve conflicts, reduce tension and achieve common goals.

How to develop a better intercultural awareness sensitivity?

There are many ways to improve intercultural awareness.

What is key is to have a proper orientation and willingess to expand the own personal world view.

One way is to attend events that celebrate diversity.

These can be festivals, concerts, or other cultural events. another way is to learn about other cultures by reading books, watching movies, or talking to people from different cultures.

By interacting with different people from around the world will influence your perception to really interpret and build an opinion of your own about the culture.

It is important to be respectful of other cultures and to avoid making any assumptions or judgments about them.

Learning and language teaching is a way of transmitting intercultural knowlege, as it is a point of interaction to understand a society.

Language is a crucial part of the identity of a region, and it sets as well the way of thinking and expressing.

And as well, in linguistic it is not only about the language but as well the body language, and how different cultures express themeselves in different ways.

As well, living abroad could be considered the best way to sumerge into another culture and see the world with your own eyes.

Yes, people might read, listen to stores and watch movies, but to build a proper self-awareness of a different culture is better to live in that country.

The dynamic of living abroad brings a person outside of his or her comfort zone, where the person has to deal with the different aspects of life, like going out to do grocery shopping, being at a restaurant, checking out health care, and working.

If the country where the person is living has a different language, then he has to translate at first all the signs, documents and text that he reads in order to understand.

The curiosity to learn more about the culture will bring the person to outside of his comfort zone, and eventually will create his own point of view of the culture.

Why intercultural communication is important in business?

In today’s business world, it’s more important than ever to be aware of the different cultures that exist within and outside of your company.

By understanding the customs, reactions, traditions, and values of others, you can create a more inclusive environment and avoid potential misunderstandings or conflict.

Additionally, being aware of different cultures can help you tap into new markets and better understand your customers’ needs.

Cultural awareness can affect the workplace in a number of ways.

For example, if employees are not aware of the different cultural backgrounds of their colleagues, they may make assumptions or judgments that are not accurate.

Additionally, cultural awareness can help create a more positive and productive work environment by promoting understanding and respect for differences. When employees are aware of the culture of their workplace, they can be more effective in intercultural communication and collaboration.

Organizational success can be measured in many ways, but one important factor is cultural awareness.

A company that is culturally aware is able to understand and appreciate the differences between cultures effectively across peers, and how those differences can impact business.

This understanding can help a company to avoid misunderstandings and communication problems, and can ultimately lead to better business results.

Ultimately, cultural awareness is key to success in today’s global economy.

Privacy Overview

- INTERPERSONAL SKILLS

- Emotional Intelligence

Intercultural Awareness

Search SkillsYouNeed:

Interpersonal Skills:

- A - Z List of Interpersonal Skills

- Interpersonal Skills Self-Assessment

- Communication Skills

The SkillsYouNeed Guide to Interpersonal Skills

- Myers-Briggs Type Indicators (MBTI)

- MBTI in Practice

- Self-Awareness

- What is Charisma?

- Building Confidence

- Building Workplace Confidence

- Self-Regulation | Self-Management

- Self-Control

- Trustworthiness and Conscientiousness

- Confidentiality

- Personal Change Management

- Recognising and Managing Emotions

- Dealing with Bereavement and Grief

- Innovation Skills

- Self-Motivation

- How Self-Motivated are You? Quiz

- Setting Personal Goals

- Time Management

- How Good Are Your Time Management Skills? Quiz

- Minimising Distractions and Time Wasters

- Avoiding Procrastination

- Work/Life Balance

- What is Empathy?

- Types of Empathy

- Understanding Others

- Understanding and Combating Stereotypes

- Understanding and Addressing Unconscious Bias

- What is Sympathy?

- Talking About Death

- Social Media Etiquette around Death

- Talking About Money

- Political Awareness

- Cultural Intelligence

- Building Cultural Competence

- Intercultural Communication Skills

- Understanding Intersectionality

- Becoming an Ally and Allyship

- Social Skills in Emotional Intelligence

- Networking Skills

- Top Tips for Effective Networking

- Building Rapport

- Tact and Diplomacy

- How to be Polite

- Politeness vs Honesty

- Conflict Resolution and Mediation Skills

- Customer Service Skills

- Team-Working, Groups and Meetings

- Decision-Making and Problem-Solving

- Negotiation and Persuasion Skills

- Personal and Romantic Relationship Skills

Subscribe to our FREE newsletter and start improving your life in just 5 minutes a day.

You'll get our 5 free 'One Minute Life Skills' and our weekly newsletter.

We'll never share your email address and you can unsubscribe at any time.

Intercultural awareness is, quite simply, having an understanding of both your own and other cultures, and particularly the similarities and differences between them.

These similarities and differences may be in terms of values, beliefs, or behaviour. They may be large or small, and they matter very much when you are meeting or interacting with people who are from another cultural background.

Understanding that people from different cultures have different values is the foundation to good intercultural relationships.

The Importance of Intercultural Awareness

In a multicultural world, most of us need at least some intercultural awareness every day. For those who live or work away from our native countries, or who live or work closely with those from another country, it is absolutely vital.

But even just for a two-week holiday abroad, intercultural awareness is a vital quality that can prevent you from causing offence.

Research from the British Council suggests that employers value intercultural skills, including foreign languages, but in particular intercultural awareness, understanding of different viewpoints, and demonstrating respect for others.

There are four groups of people who are most likely to need intercultural awareness:

- Expatriates

- People who work globally

- People who work in multicultural teams

1. Expatriates

Expatriates, or expats, are people who live and work away from their native country.

Usually employed by multi-nationals rather than local companies, expats may be on quite long postings, perhaps two to three years. They are often quite senior in their organisation and are expected to be able to apply skills learned elsewhere to the new location.

Lack of intercultural awareness, and in particular of the way things are done round here , can often damage or derail expat assignments.

2. People Who Work Globally

Even those based in their native country may, in a global economy, need to work with people from other countries and cultures. A little intercultural awareness may prevent them giving or taking offence unnecessarily.

3. People Who Work in Multicultural Teams

There are very few of us who do not have at least some contact with colleagues or acquaintances who are non-native. Some industries and organisations have large numbers of migrant workers, for example, healthcare and social care where nurses are highly sought-after and often recruited from abroad.

Intercultural awareness helps to ease colleague–colleague and colleague–manager interactions and prevent misunderstandings.

4. Tourists

You may feel that two weeks’ holiday does not justify finding out a bit more about the culture of the place you are visiting. But as a visitor, you are, like it or not, seen as a representative of your country. And it is perfectly possible to give offence inadvertently.

Case study: Getting it badly wrong

In June 2015, British tourist Eleanor Hawkins was arrested in Malaysia. Her crime? Along with several others, to strip naked on top of a mountain which locals viewed as sacred. This might have been overlooked had there not been an earthquake a few days later, which locals put down to the mountain spirit being angry with the group of tourists.

In the UK, stripping off is not a big deal. It might offend a few people if you did it in a town centre, but it’s more likely to raise a laugh. In Malaysia, it’s quite another thing. Eleanor Hawkins’ trip was cut short and she returned home sadder and wiser.

Degrees of Intercultural Awareness: A Spectrum

We can define four levels of intercultural awareness, which can broadly be considered as a spectrum.

Developing Intercultural Awareness

What can you do to develop intercultural awareness? Here are some ideas:

Admit that you don’t know. Acknowledging your ignorance is the first step towards learning about other cultures.

Develop an awareness of your own views, assumptions and beliefs, and how they are shaped by your culture. Ask yourself questions like: what do I see as ‘national’ characteristics in this country? Which ‘national’ characteristic do I like and dislike in myself?

Take an interest. Read about other countries and cultures, and start to consider the differences between your own culture and what you have read.

Don’t make judgements. Instead, start by collecting information. Ask neutral questions and clarify meaning before assuming that you know what’s going on. See our pages on Questioning and Clarifying for more.

Once you have collected information, start to check your assumptions. Ask colleagues or friends who know more about the culture than you, and systematically review your assumptions to make sure that they are correct.

Develop empathy. Think about how it feels to be in the other person’s position. See our page on Empathy for more.

Look for what you can gain, not what you could lose. If you can take the best from both your own and someone else’s views and experiences, you could get a far greater whole that will benefit both of you. But this requires you to take the approach that you don’t necessarily know best, and even that you don’t necessarily know at all.

The Importance of Celebrating Diversity

In the final analysis, intercultural awareness leads ideally to a point of celebrating diversity.

That is, recognising that everyone, of whatever background, skills or experience, brings something unique to the table. If you, collectively, can harness that and bring everyone’s skills together, the group can be better than the sum of its parts.

Continue to: Intercultural Communication Cultural Intelligence

See also: Understanding Intersectionality Becoming an Ally and Allyship Politeness - How to be Polite

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Cultural Awareness—How to Be More Culturally Aware & Improve Your Relationships

Wendy Wisner is a health and parenting writer, lactation consultant (IBCLC), and mom to two awesome sons.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/28685632_10156312296594515_9028950978590849197_n-815354ed2f8e44be900fda9060a465f5.jpg)

Ivy Kwong, LMFT, is a psychotherapist specializing in relationships, love and intimacy, trauma and codependency, and AAPI mental health.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Ivy_Kwong_headshot_1000x1000-8cf49972711046e88b9036a56ca494b5.jpg)

The Importance of Cultural Awareness

How to be more culturally aware, what if i say the wrong thing, cultural awareness and sensitivity in intercultural/interracial relationships, can i ask someone to help me learn about their culture, pitfalls of not developing cultural awareness.

Cultural awareness, sometimes referred to as cultural sensitivity , is defined by the NCCC (National Center for Cultural Competence) as being cognizant, observant, and conscious of the similarities and differences among and between cultural groups.

Becoming more culturally aware is a continual process and it can help to have curiosity, an open mind, a willingness to ask questions, a desire to learn about the differences that exist between cultures, and an openness to becoming conscious of one’s own culturally shaped values, beliefs, perceptions, and biases.

The Value of Cultural Awareness

Cultural awareness is important because it allows us to see and respect other perspectives and to appreciate the inherent value of people who are different than we are. It leads to better relationships, healthier work environments, and a stronger, more compassionate society.

Read on to learn more about cultural awareness, including the impacts it can have, how to become more culturally aware, how to approach conversations about cultural awareness, and how to address cultural awareness in intercultural relationships.

Cultural awareness involves learning about cultures that are different from your own. But it’s also about being respectful about these differences, says Natalie Page Ed.D., chief diversity officer at Saint Xavier University in Chicago. “It’s about being sensitive to the similarities and differences that can exist between different cultures and using this sensitivity to effectively communicate without prejudice and racism,” she explains.

5 Reasons Why Cultural Awareness Is Important

Here are five reasons why it’s important to become more culturally aware:

- When you strive to become more culturally aware, you gain knowledge and information about different cultures, which leads to greater cultural competence, says Dr. Page

- Engaging in cultural awareness makes you more sensitive to the differences between cultures that are different than your own, Dr. Page says; you also become less judgmental of people who are different than you.

- Studies have found that greater cultural awareness in the workplace leads to an overall better workplace culture for everyone involved.

- Research has found that cultural awareness creates better outcomes for people in healthcare environments, and in other environments where people are receiving care from others.

- According to Nika White, PhD, author of Inclusion Uncomplicated: A Transformative Guide to Simplify DEI , cultural awareness can improve your interpersonal relationships. “Just like any other relationship, you must understand their culture to truly understand someone’s lived experiences and how they show up to the world,” Dr. White describes.

Knowing about the importance of being more culturally aware is one thing, but actually taking steps to do so is something else.

It’s about being sensitive to the similarities and differences that can exist between different cultures and using this sensitivity to effectively communicate without prejudice and racism.

Here are a few tips for how to go about becoming more culturally aware.

Understand That It’s a Process

“Becoming culturally aware is a process that is fluid, birthed out of a desire to learn more about other cultures,” says Dr. Page.

She says it can be helpful to study the model laid out by Dr. Ibram Kendi, the author of How To Be An Antiracist . Dr. Kendi says that there are basically three paths to growing cultural awareness:

- “The first is moving from the fear zone, where you are afraid and would rather stay in your own culture comfort zone,” Dr. Page describes.

- Next is moving into the learning zone, where you strive to learn about different cultures, how people acquire their cultures, and culture's important role in personal identities, practices, and mental and physical health of individuals and communities. The learning zone can also include becoming more aware of your own culturally shaped values, beliefs, and biases and how they impact the way you see yourself and others.

- “The last phase is the growth zone, where you grow in racial advocacy and allyship,” says Dr. Page.

Ask Questions

Dr. White says that asking questions is a vital part of becoming more culturally aware. You can start by asking yourself some important questions, such as: “How is my culture affecting how I interact with and perceive others?” Dr. White suggests.

You can also respectfully ask others about their lives. But make sure the exchanges aren’t one-sided, she recommends: when you ask others about their cultures, tell them about yours, too. “Tell your own stories to engage, build relationships, find common ground, and become more culturally aware of someone from a different culture,” she says.

Educate Yourself and Do the Work

There’s no way around it: if you want to become more culturally aware, you need to take action and educate yourself.

“Don’t lean on assumptions,” says Dr. White. “Actually research cultures different from yours.” This can help you become more aware of how culture affects every aspect of your life and the lives of others. In addition to research, educating yourself often involves seeking and participating in meaningful interactions with people of differing cultural backgrounds. “Expand your network to include people from different cultures into your circle,” Dr. White recommends.

Study the Cultural Competence Continuum Model

The Cultural Competence Continuum Model is an assessment tool that helps us understand where people are on their journey to becoming more culturally competent.

Different people fall into various categories along the continuum. Categories include cultural destructiveness, cultural incapacity, cultural blindness, cultural pre-competence, cultural competence, and cultural proficiency.

Studying this model can help us become more aware of the process of moving toward more cultural sensitivity, and become more patient with ourselves and others as we move through the process.

Acknowledge Your Own Bias

We all have our own biases when it comes to cultural awareness, because we all begin by looking at the world and at others through our own cultural lens.

It is important to acknowledge this as it can help us see how our cultural biases may prevent us from being as culturally sensitive as we wish to be.

Often, people don’t want to address topics having to do with culture or race because they are afraid they will say the wrong thing or make a mistake while talking to someone.

The truth is, most people make mistakes on their journey toward cultural awareness, and that’s understandable, says Dr. Page.

“If you make a mistake, simply apologize and let the person that you may have offended know that you are learning and be open to any suggestions they may have,” she recommends. Sometimes it even makes sense to apologize in advance, if you are saying something you are unsure of. You can say, “I may have this wrong, so I apologize beforehand but…” Dr. Page suggests. “The key is to be sincere in your conversations and always open to learning from others,” she says.

Making mistakes is a necessary part of the learning process and it is important to approach these topics and conversations with shared respect, compassion, and grace.

If you are in a relationship with someone who is of a different race or culture than you, it’s important to have open, honest discussions about this. “If a person is going to grow in interracial and intercultural relationships, you have to step out of your cultural comfort zone and seek an understanding about other cultures,” says Dr. Page.

Questions to Ask Someone to Learn About Their Culture

Having a genuine discussion with someone about your differences can feel awkward, and it can be helpful to kick-start the conversation with a few open-ended questions. Dr. White shared some helpful questions:

- Can you tell me about your culture?

- Tell me a little something about how you were raised?

- What role does religion play in your life?

Here are some additional questions that could be asked with respect and consent, to another (and also to yourself!):

- What holidays and celebrations are important in your culture?

- What customs and etiquette are important in your culture?

- What is your favorite food in your culture?

- Is religion an important part of life in your culture? If so, what religion do people practice most often and why do you think that is?

- How do you express your cultural identity?

- What stereotypes or misconceptions do people from your culture often face and what do you wish more people knew?

- Is there anything about your culture that you find challenging?

- How has your culture changed over time?

- How do you think your culture has influenced your personal values and beliefs?

- What is the importance of family in your culture?

One of the important ways to develop culture awareness is to educate yourself about other cultures. Learning directly from people of different cultures is a fantastic way to get authentic information. But it’s important to engage in conversations with others about their cultures in respectful , appropriate manners.

When you decide to ask others about their culture, be mindful that they may not want to answer, and know that that’s okay, says Dr. White. It’s also important to make the conversation a two-way street. Don’t just ask them about their culture—talk about your culture as well. “Share your culture first to model the behavior and let others know it is safe to talk about their culture,” Dr. White suggests.

Finally, make sure to take it upon yourself to do some of the work. “Once you learn of someone’s culture you wish to cultivate a relationship with, do your homework to learn as much as you can,” Dr. White says. Don't simply rely on others to educate you—this may be seen as insensitive, Dr. White says.

The main pitfalls of not developing cultural awareness is that we don’t expand our understanding of other cultures, we don’t deepen our relationship with people who are different than we are, and that we risk continuing to have a narrow view of the world around us.

“We live in an ever-changing diverse world,” Dr. Page says. “We rob ourselves when we only hang out with people from our cultural groups. We have to branch out and experience the beauty that others bring.”

Angelis T. In search of cultural competence . Monitor on Psychology. 2015;46(3):64.

Shepherd SM, Willis-Esqueda C, Newton D, et al. The challenge of cultural competence in the workplace: perspectives of healthcare providers . BMC Health Services Research. 2019;19:135. doi:10.1186/s12913-019-3959-7

Kaihlanen AM., Hietapakka L, Heponiemi T. Increasing cultural awareness: qualitative study of nurses’ perceptions about cultural competence training . BMC Nursing. 2019;18(38). doi:10.1186/s12912-019-0363-x

Calkins H. How You Can Be More Culturally Competent . Good Practice. 2020:13-16.

Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Improving Cultural Competence .

By Wendy Wisner Wendy Wisner is a health and parenting writer, lactation consultant (IBCLC), and mom to two awesome sons.

Intercultural Communication Essay Topics Examples?

Delve into the engaging world of Intercultural Communication Essay Topics & Examples . This comprehensive guide, enriched with enlightening Intercultural Communication Examples , is your gateway to understanding and exploring the multifaceted aspects of intercultural interactions. Whether you’re a student crafting an essay, a teacher seeking topic inspiration, or a curious learner, these examples and topics will ignite your creativity and deepen your insight into the complexities and beauty of intercultural communication.

What are Intercultural Communication Essay Topics, Examples?

Intercultural communication essay topics and examples refer to ideas and scenarios that are used to write essays about how people from different cultural backgrounds communicate and interact with each other. These topics often explore the challenges, strategies, and importance of understanding and respecting different cultures in communication. Examples might include real-life situations, like how businesses from different countries negotiate deals, or theoretical discussions, like the role of language in bridging cultural gaps. These topics and examples help students and writers understand and analyze the ways in which our cultural backgrounds influence the way we communicate and interact with others in a diverse world.

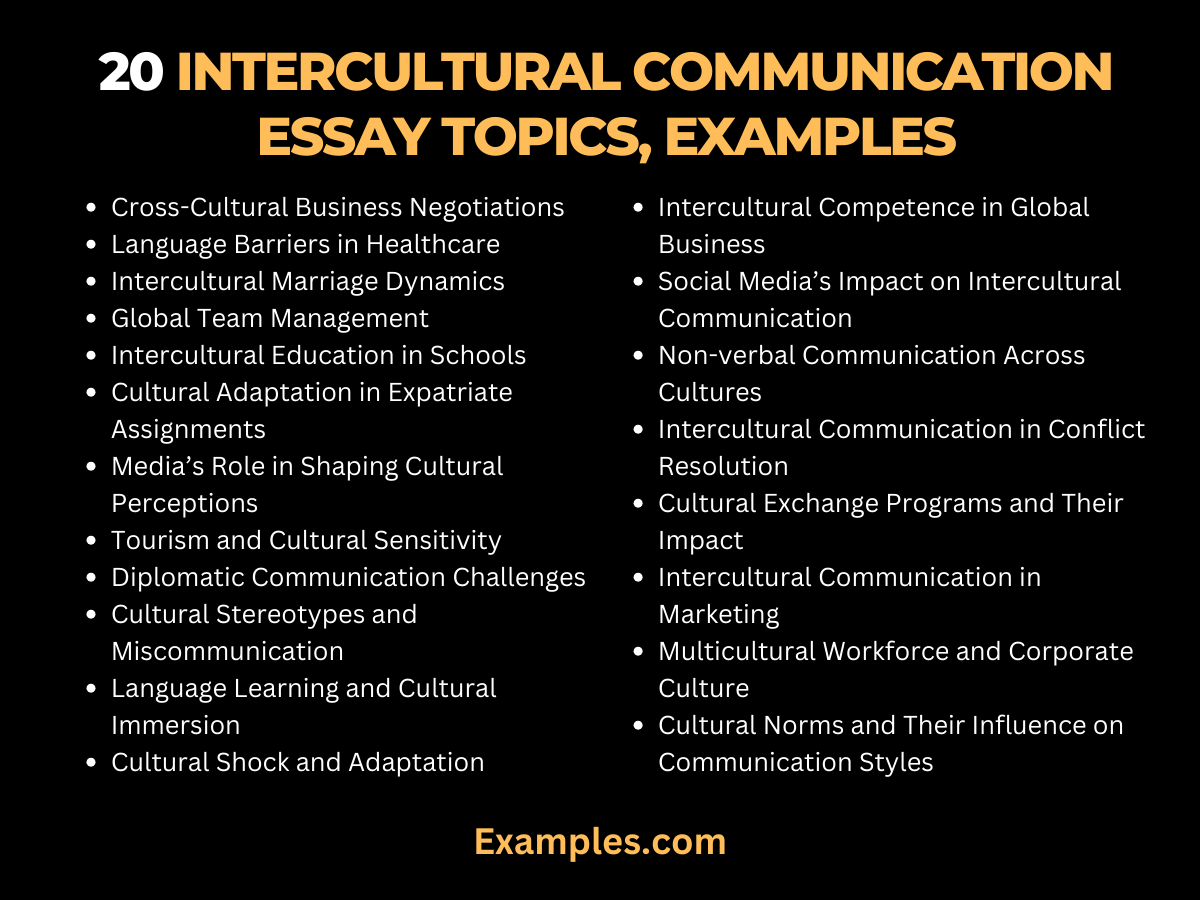

20 Intercultural Communication Essay Topics, Examples

Discover a diverse range of Intercultural Communication Essay Topics & Examples , ideal for deepening your understanding of global communication. These topics, rich in cultural insights, are perfect for exploring the nuances of cross-cultural interactions. From business negotiations to personal relationships, these examples illustrate the complexity and beauty of communicating across cultures. Whether for academic essays or personal growth, these topics and examples provide a thorough understanding of the challenges and strategies in intercultural communication.

1. Cross-Cultural Business Negotiations : Explore how businesses from different cultural backgrounds negotiate deals. Understand the importance of cultural sensitivity, non-verbal cues, and the role of hierarchy in business discussions.

2. Language Barriers in Healthcare : Analyze the impact of language barriers in healthcare settings and the importance of interpreters. Discuss the challenges faced by healthcare providers and patients in understanding each other’s cultural and linguistic backgrounds.

3. Intercultural Marriage Dynamics : Examine communication in intercultural marriages. Focus on the importance of mutual cultural understanding, respecting differences, and adapting communication styles.

4. Global Team Management : Discuss the challenges of managing a culturally diverse team. Highlight strategies for effective communication, conflict resolution, and leveraging cultural diversity to enhance team performance.

5. Intercultural Education in Schools : Evaluate the role of schools in fostering intercultural communication among students. Discuss initiatives like exchange programs and multicultural events that promote cultural understanding.

6. Cultural Adaptation in Expatriate Assignments : Explore the experiences of expatriates adapting to a new culture. Discuss the importance of cultural immersion, coping strategies, and the role of cross-cultural training.

7. Media’s Role in Shaping Cultural Perceptions : Analyze how media influences perceptions of different cultures. Discuss the impact of stereotypes, cultural representation, and the need for culturally sensitive media content.

8. Tourism and Cultural Sensitivity : Examine the role of cultural sensitivity in tourism. Discuss how tourists can respect local customs and traditions while exploring new cultures.

9. Diplomatic Communication Challenges : Explore communication challenges in international diplomacy. Discuss the importance of cultural intelligence, protocol understanding, and maintaining international relations.

10. Cultural Stereotypes and Miscommunication : Investigate how cultural stereotypes lead to miscommunication. Discuss ways to overcome stereotypes and promote understanding.

11. Language Learning and Cultural Immersion : Discuss the role of language learning in cultural immersion. Highlight the importance of language in understanding a culture and effective communication.

12. Cultural Shock and Adaptation : Explore the concept of cultural shock and strategies for adaptation. Discuss personal experiences and coping mechanisms in a new cultural environment.

13. Intercultural Competence in Global Business : Evaluate the importance of intercultural competence in global business. Discuss strategies for developing cultural awareness and sensitivity in a business context.

14. Social Media’s Impact on Intercultural Communication : Analyze the role of social media in bridging or widening cultural gaps. Discuss the opportunities and challenges social media presents in understanding different cultures.

15. Non-verbal Communication Across Cultures : Examine the role of non-verbal communication in different cultures. Discuss how gestures, eye contact, and body language vary and affect communication.

16. Intercultural Communication in Conflict Resolution : Explore the role of intercultural communication in resolving conflicts. Discuss strategies for mediating and understanding different cultural perspectives in conflicts.

17. Cultural Exchange Programs and Their Impact : Analyze the impact of cultural exchange programs on students and professionals. Discuss how these programs enhance cultural understanding and communication skills.

18. Intercultural Communication in Marketing : Explore how marketing strategies are adapted for different cultural audiences. Discuss the importance of understanding cultural nuances in creating effective marketing campaigns.

19. Multicultural Workforce and Corporate Culture : Examine the influence of a multicultural workforce on corporate culture. Discuss strategies for creating an inclusive workplace that respects cultural differences.

20. Cultural Norms and Their Influence on Communication Styles : Investigate how cultural norms influence communication styles. Discuss the importance of understanding these norms for effective intercultural interaction.

Intercultural Communication Essay Discussion Topics

Embark on a journey of cultural discovery with these Intercultural Communication Essay Discussion Topics . Perfect for fostering insightful debates and deep analysis, these topics are designed to engage students and enthusiasts in the complexities of intercultural dialogue. From exploring the role of technology in bridging cultural divides to understanding the impact of cultural identity on communication, these topics offer a rich ground for exploration and discussion, enhancing one’s intercultural awareness and skills.

1. Impact of Globalization on Cultural Identities : Discuss how globalization affects cultural identities and communication. Consider both positive and negative impacts on cultural preservation and exchange.

2. Cultural Intelligence in Leadership : Explore the role of cultural intelligence in effective leadership. Discuss how leaders can cultivate this skill to manage diverse teams.

3. Role of Intercultural Communication in Conflict Zones : Analyze the importance of intercultural communication in resolving conflicts in multicultural regions. Discuss techniques and strategies used.

4. Digital Platforms as Tools for Intercultural Understanding : Evaluate how digital platforms can foster intercultural understanding. Discuss both the opportunities and challenges they present.

5. Intercultural Communication Barriers in Online Education : Explore the barriers faced in online education settings. Discuss strategies to overcome these challenges for a more inclusive learning environment.

6. The Influence of Culture on Consumer Behavior : Discuss how culture influences consumer behavior. Explore implications for international marketing and advertising strategies.

7. Intercultural Misunderstandings in the Workplace : Examine common intercultural misunderstandings in the workplace. Discuss strategies for prevention and resolution.

8. Ethical Considerations in Intercultural Communication : Analyze the ethical dimensions of intercultural communication. Discuss the balance between cultural respect and freedom of expression.

9. The Role of Language in Cultural Identity : Explore the relationship between language and cultural identity. Discuss the impact of language loss on cultural heritage.

10. Cultural Adaptation vs. Cultural Assimilation : Discuss the difference between adaptation and assimilation in intercultural contexts. Consider the implications for individual identity and cultural preservation.

Intercultural Communication Examples in Everyday Life

Intercultural Communication Examples in Everyday Life illustrate how cultural diversity enriches our daily interactions. These examples showcase real-life scenarios where understanding and adapting to different cultural contexts enhance communication and relationships. They offer insightful glimpses into the practical application of intercultural communication skills, proving invaluable for those looking to navigate our diverse world with greater empathy and effectiveness.

1. Ordering Food in a Multicultural Restaurant : Navigating menu choices and communicating dietary preferences in a multicultural restaurant. Understanding and respecting culinary traditions and practices.

2. Participating in a Cultural Festival : Engaging in a local cultural festival, learning about traditional customs, and communicating respectfully with participants from different cultural backgrounds.

3. Multilingual Signage in Public Spaces : Observing and understanding multilingual signage in airports or public transport. Appreciating linguistic diversity in communal areas.

4. Cultural Norms in Public Greetings : Adapting to different greeting customs in public interactions. Understanding varying norms for handshakes, bows, or verbal greetings.

5. Intercultural Dynamics in Sports Teams : Playing in or supporting multicultural sports teams. Communicating and collaborating with team members from diverse cultural backgrounds.

6. Shopping in Ethnic Markets : Shopping in ethnic markets, understanding cultural significance of products, and interacting respectfully with vendors.

7. Cultural Nuances in Neighbourhood Gatherings : Participating in neighbourhood gatherings with residents from diverse cultures. Sharing and respecting different cultural perspectives and traditions.

8. Watching Foreign Language Films with Subtitles : Watching and understanding foreign language films with subtitles. Gaining insights into different cultural narratives and expressions.

9. Intercultural Exchanges in Language Learning Classes : Engaging in language learning classes with students from various cultures. Sharing cultural insights and learning from each other.

10. Cultural Representation in Art Exhibitions : Visiting art exhibitions showcasing works from different cultures. Appreciating the diversity in artistic expressions and cultural stories.

In conclusion, this comprehensive guide on Intercultural Communication Essay Topics, Examples, How to Write & Tips provides invaluable insights and practical examples for anyone keen to explore the rich tapestry of intercultural communication. It serves as an essential resource, offering guidance, inspiration, and a deeper understanding of how to navigate and articulate the complexities of communicating across diverse cultural landscapes.

AI Generator

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Intercultural Communication Essay Topics, Examples

10 Intercultural Communication Essay Topics

10 Intercultural Communication Examples

10Intercultural Communication Essay Discussion Topics

10 Intercultural Communication Examples in Everyday Life

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Communication and Culture

- Communication and Social Change

- Communication and Technology

- Communication Theory

- Critical/Cultural Studies

- Gender (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies)

- Health and Risk Communication

- Intergroup Communication

- International/Global Communication

- Interpersonal Communication

- Journalism Studies

- Language and Social Interaction

- Mass Communication

- Media and Communication Policy

- Organizational Communication

- Political Communication

- Rhetorical Theory

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Intercultural competence.

- Lily A. Arasaratnam Lily A. Arasaratnam Director of Research, Department of Communication, Alphacrucis College

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228613.013.68

- Published online: 03 February 2016

The phrase “intercultural competence” typically describes one’s effective and appropriate engagement with cultural differences. Intercultural competence has been studied as residing within a person (i.e., encompassing cognitive, affective, and behavioral capabilities of a person) and as a product of a context (i.e., co-created by the people and contextual factors involved in a particular situation). Definitions of intercultural competence are as varied. There is, however, sufficient consensus amongst these variations to conclude that there is at least some collective understanding of what intercultural competence is. In “Conceptualizing Intercultural Competence,” Spitzberg and Chagnon define intercultural competence as, “the appropriate and effective management of interaction between people who, to some degree or another, represent different or divergent affective, cognitive, and behavioral orientations to the world” (p. 7). In the discipline of communication, intercultural communication competence (ICC) has been a subject of study for more than five decades. Over this time, many have identified a number of variables that contribute to ICC, theoretical models of ICC, and quantitative instruments to measure ICC. While research in the discipline of communication has made a significant contribution to our understanding of ICC, a well-rounded discussion of intercultural competence cannot ignore the contribution of other disciplines to this subject. Our present understanding of intercultural competence comes from a number of disciplines, such as communication, cross-cultural psychology, social psychology, linguistics, anthropology, and education, to name a few.

- intercultural competence

- intercultural communication

- appropriate

A Brief Introduction

With increasing global diversity, intercultural competence is a topic of immediate relevance. While some would question the use of the term “competence” as a Western concept, the ability to understand and interact with people of different cultures in authentic and positive ways is a topic worth discussing. Though several parts of the world do remain culturally homogenous, many major cities across the world have undergone significant transformation in their cultural and demographic landscape due to immigration. Advances in communication technologies have also facilitated intercultural communication without the prerequisite of geographic proximity. Hence educational, business, and other projects involving culturally diverse workgroups have become increasingly common. In such contexts the success of a group in accomplishing its goals might not depend only on the group members’ expertise in a particular topic or ability to work in a virtual environment but also on their intercultural competence (Zakaria, Amelinckx, & Wilemon, 2004 ). Cultural diversity in populations continues to keep intercultural competence (or cultural competence, as it is known in some disciplines) on the agenda of research in applied disciplines such as medicine (Bow, Woodward, Flynn, & Stevens, 2013 ; Charles, Hendrika, Abrams, Shea, Brand, & Nicol, 2014 ) and education (Blight, 2012 ; Tangen, Mercer, Spooner-Lane, & Hepple, 2011 ), for example.

As noted in the historiography section, early research in intercultural competence can be traced back to acculturation/adaptation studies. Labels such as cross-cultural adaptation and cross-cultural adjustment/effectiveness were used to describe what we now call intercultural competence, though adaptation and adjustment continue to remain unique concepts in the study of migrants. It is fair to say that today’s researchers would agree that, while intercultural competence is an important part of adapting to a new culture, it is conceptually distinct.

Although our current understanding of intercultural competence is (and continues to be) shaped by research in many disciplines, communication researchers can lay claim to the nomenclature of the phrase, particularly intercultural communication competence (ICC). Intercultural competence is defined by Spitzberg and Chagnon ( 2009 ) as “the appropriate and effective management of interaction between people who, to some degree or another, represent different or divergent affective, cognitive, and behavioral orientations to the world” (p. 7), which touches on a long history of intercultural competence being associated with effectiveness and appropriateness. This is echoed in several models of intercultural competence as well. The prevalent characterization of effectiveness as the successful achievement of one’s goals in a particular communication exchange is notably individualistic in its orientation. Appropriateness, however, views the communication exchange from the other person’s point of view, as to whether the communicator has communicated in a manner that is (contextually) expected and accepted.

Generally speaking, research findings support the view that intercultural competence is a combination of one’s personal abilities (such as flexibility, empathy, open-mindedness, self-awareness, adaptability, language skills, cultural knowledge, etc.) as well as relevant contextual variables (such as shared goals, incentives, perceptions of equality, perceptions of agency, etc.). In an early discussion of interpersonal competence, Argyris ( 1965 ) proposed that competence increases as “one’s awareness of relevant factors increases,” when one can solve problems with permanence, in a manner that has “minimal deterioration of the problem-solving process” (p. 59). This view of competence places it entirely on the abilities of the individual. Kim’s ( 2009 ) definition of intercultural competence as “an individual’s overall capacity to engage in behaviors and activities that foster cooperative relationships in all types of social and cultural contexts in which culturally or ethnically dissimilar others interface” (p. 62) further highlights the emphasis on the individual. Others, however, suggest that intercultural competence has an element of social judgment, to be assessed by others with whom one is interacting (Koester, Wiseman, & Sanders, 1993 ). A combination of self and other assessment is logical, given that the definition of intercultural competence encompasses effective (from self’s perspective) and appropriate (from other’s perspective) communication.

Before delving further into intercultural competence, some limitations to our current understanding of intercultural competence must be acknowledged. First, our present understanding of intercultural competence is strongly influenced by research emerging from economically developed parts of the world, such as the United States and parts of Europe and Oceania. Interpretivists would suggest that the (cultural) perspectives from which the topic is approached inevitably influence the outcomes of research. Second, there is a strong social scientific bias to the cumulative body of research in intercultural competence so far; as such, the findings are subject to the strengths and weaknesses of this epistemology. Third, because many of the current models of intercultural competence (or intercultural communication competence) focus on the individual, and because individual cultural identities are arguably becoming more blended in multicultural societies, we may be quickly approaching a point where traditional definitions of intercultural communication (and by association, intercultural competence) need to be refined. While this is not an exhaustive list of limitations, it identifies some of the parameters within which current conceptualizations of intercultural competence must be viewed.

The following sections discuss intercultural competence, as we know it, starting with what it is and what it is not . A brief discussion of well-known theories of ICC follows, then some of the variables associated with ICC are identified. One of the topics of repeated query is whether ICC is culture-general or culture-specific. This is addressed in the section following the discussion of variables associated with ICC, followed by a section on assessment of ICC. Finally, before delving into research directions for the future and a historiography of research in ICC over the years, the question of whether ICC can be learned is addressed.

Clarification of Nomenclature

As noted in the summary section, one of the most helpful definitions of intercultural competence is provided by Spitzberg and Chagnon ( 2009 ), who define it as “the appropriate and effective management of interaction between people who, to some degree or another, represent different or divergent affective, cognitive, and behavioral orientations to the world” (p. 7). However, addressing what intercultural competence is not is just as important as explaining what it is, in a discussion such as this. Conceptually, intercultural competence is not equivalent to acculturation, multiculturalism, biculturalism, or global citizenship—although intercultural competence is a significant aspect of them all. Semantically, intercultural efficiency, cultural competence, intercultural sensitivity, intercultural communication competence, cross-cultural competence, and global competence are some of the labels with which students of intercultural competence might be familiar.

The multiplicity in nomenclature of intercultural competence has been one of the factors that have irked researchers who seek conceptual clarity. In a meta-analysis of studies in intercultural communication competence, Bradford, Allen, and Beisser ( 2000 ) attempted to synthesize the multiple labels used in research; they concluded that intercultural effectiveness is conceptually equivalent to intercultural communication competence. Others have proposed that intercultural sensitivity is conceptually distinct from intercultural competence (Chen & Starosta, 2000 ). Others have demonstrated that, while there are multiple labels in use, there is general consensus as to what intercultural competence is (Deardorff, 2006 ).

In communication literature, it is fair to note that intercultural competence and intercultural communication competence are used interchangeably. In literature in other disciplines, such as medicine and health sciences, cultural competence is the label with which intercultural competence is described. Some have also proposed the phrase cultural humility as a deliberate alternative to cultural competence, suggesting that cultural humility involves life-long learning through self-awareness and critical reflection (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998 ).

The nature of an abstract concept is such that its reality is defined by the labels assigned to it. Unlike some concepts that have been defined and developed over many years within the parameters of a single discipline, intercultural competence is of great interest to researchers in multiple disciplines. As such, researchers from different disciplines have ventured to study it, without necessarily building on findings from other disciplines. This is one factor that has contributed to the multiple labels by which intercultural competence is known. This issue might not be resolved in the near future. However, those seeking conceptual clarity could look for the operationalization of what is being studied, rather than going by the name by which it is called. In other words, if what is being studied is effectiveness and appropriateness in intercultural communication (each of these terms in turn need to be unpacked to check for conceptual equivalency), then one can conclude that it is a study of intercultural competence, regardless of what it is called.

Theories of Intercultural Competence

Many theories of intercultural (communication) competence have been proposed over the years. While it is fair to say that there is no single leading theory of intercultural competence, some of the well-known theories are worth noting.

There are a couple of theories of ICC that are identified as covering laws theories (Wiseman, 2002 ), namely Anxiety Uncertainty Management (AUM) theory and Face Negotiation theory. Finding its origins in Berger and Calabrese ( 1975 ), AUM theory (Gudykunst, 1993 , 2005 ) proposes that the ability to be mindful and the effective management of anxiety caused by the uncertainty in intercultural interactions are key factors in achieving ICC. Gudykunst conceptualizes ICC as intercultural communication that has the least amount of misunderstandings. While AUM theory is not without its critics (for example, Yoshitake, 2002 ), it has been used in a number of empirical studies over the years (examples include Duronto, Nishida, & Nakayama, 2005 ; Ni & Wang, 2011 ), including studies that have extended the theory further (see Neuliep, 2012 ).

Though primarily focused on intercultural conflict rather than intercultural competence, Face Negotiation theory (Ting-Toomey, 1988 ) proposes that all people try to maintain a favorable social self-image and engage in a number of communicative behaviours designed to achieve this goal. Competence is identified as being part of the concept of “face,” and it is achieved through the integration of knowledge, mindfulness, and skills in communication (relevant to managing one’s own face as well as that of others). Face Negotiation theory has been used predominantly in intercultural conflict studies (see Oetzel, Meares, Myers, & Lara, 2003 ). As previously noted, it is not primarily a theory of intercultural competence, but it does address competence in intercultural settings.

From a systems point of view, Spitzberg’s ( 2000 ) model of ICC and Kim’s ( 1995 ) cultural adaptation theory are also well-known. Spitzberg identifies three levels of analysis that must be considered in ICC, namely the individual system, the episodic system, and the relational system. The factors that contribute to competence are delineated in terms of characteristics that belong to an individual (individual system), features that are particular to a specific interaction (episodic system), and variables that contribute to one’s competence across interactions with multiple others (relational system). Kim’s cultural adaptation theory recognizes ICC as an internal capacity within an individual; it proposes that each individual (being an open system) has the goal of adapting to one’s environment and identifies cognitive, affective, and behavioral dimensions of ICC.

Wiseman’s ( 2002 ) chapter on intercultural communication competence, in the Handbook of International and Intercultural Communication provides further descriptions of theories in ICC. While there have been several models of ICC developed since then, well-formed and widely tested theories of ICC remain few.

Variables Associated with Intercultural Competence

A number of variables have been identified as contributors to intercultural competence. Among these are mindfulness (Gudykunst, 1993 ), self and other awareness (Deardorff, 2006 ), listening skills (Ting-Toomey & Kurogi, 1998 ), positive attitude toward other cultures, and empathy (Arasaratnam & Doerfel, 2005 ), to name a few. Further, flexibility, tolerance for ambiguity, capacity for complexity, and language proficiency are also relevant. There is evidence to suggest that personal spiritual wellbeing plays a positive role in intercultural competence (Sandage & Jankowski, 2013 ). Additionally, there is an interesting link between intercultural competence and a biological variable, namely sensation seeking. Evidence suggests that, in the presence of a positive attitude towards other cultures and motivation to interact with people from other cultures, there is a positive relationship between sensation seeking and intercultural competence (Arasaratnam & Banerjee, 2011 ). Sensation seeking has also been associated with intercultural friendships (Morgan & Arasaratnam, 2003 ; Smith & Downs, 2004 ).

Cognitive complexity has also been identified with intercultural competence (Gudykunst & Kim, 2003 ). Cognitive complexity refers to an individual’s ability to form multiple nuanced perceptual categories (Bieri, 1955 ). A cognitively complex person relies less on stereotypical generalizations and is more perceptive to subtle racism (Reid & Foels, 2010 ). Gudykunst ( 1995 ) proposed that cognitive complexity is directly related to effective management of uncertainty and anxiety in intercultural communication, which in turn leads to ICC (according to AUM theory).

Not all variables are positively associated with intercultural competence. One of the variables that notably hinder intercultural competence is ethnocentrism. Neuliep ( 2002 ) characterizes ethnocentrism as, “an individual psychological disposition where the values, attitudes, and behaviors of one’s ingroup are used as the standard for judging and evaluating another group’s values, attitudes, and behaviors” (p. 201). Arasaratnam and Banerjee ( 2011 ) found that introducing ethnocentrism into a model of ICC weakened all positive relationships between the variables that otherwise contribute to ICC. Neuliep ( 2012 ) further discovered that ethnocentrism and intercultural communication apprehension debilitate intercultural communication. As Neuliep observed, ethnocentrism hinders mindfulness because a mindful communicator is receptive to new information, while the worldview of an ethnocentric person is rigidly centered on his or her own culture.

This is, by no means, an exhaustive list of variables that influence intercultural competence, but it is representative of the many individual-centered variables that influence the extent to which one is effective and appropriate in intercultural communication. Contextual variables, as noted in the next section, also play a role in ICC. It must further be noted that many of the ICC models do not identify language proficiency as a key variable; however, the importance of language proficiency has not been ignored (Fantini, 2009 ). Various models of intercultural competence portray the way in which (and, in some cases, the extent to which) these variables contribute to intercultural competence. For an expansive discussion of models of intercultural competence, see Spitzberg and Chagnoun ( 2009 ).

If one were to broadly summarize what we know thus far about an interculturally competent person, one could say that she or he is mindful, empathetic, motivated to interact with people of other cultures, open to new schemata, adaptable, flexible, able to cope with complexity and ambiguity. Language skills and culture-specific knowledge undoubtedly serve as assets to such an individual. Further, she or he is neither ethnocentric nor defined by cultural prejudices. This description does not, however, take into account the contextual variables that influence intercultural competence; highlighting the fact that the majority of intercultural competence research has been focused on the individual.

The identification of variables associated with intercultural competence raises a number of further questions. For example, is intercultural competence culture-general or culture-specific; can it be measured; and can it be taught or learned? These questions merit further exploration.

Culture General or Culture Specific

A person who is an effective and appropriate intercultural communicator in one context might not be so in another cultural context. The pertinent question is whether there are variables that facilitate intercultural competence across multiple cultural contexts. There is evidence to suggest that there are indeed culture-general variables that contribute to intercultural competence. This means there are variables that, regardless of cultural perspective, contribute to perception of intercultural competence. Arasaratnam and Doerfel ( 2005 ), for example, identified five such variables, namely empathy, experience, motivation, positive attitude toward other cultures, and listening. The rationale behind their approach is to look for commonalities in emic descriptions of intercultural competence by participants who represent a variety of cultural perspectives. Some of the variables identified by Arasaratnam and Doerfel’s research are replicated in others’ findings. For example, empathy has been found to be a contributor to intercultural competence in a number of other studies (Gibson & Zhong, 2005 ; Nesdale, De Vries Robbé, & Van Oudenhoven, 2012 ). This does not mean, however, that context has no role to play in perception of ICC. Contextual variables, such as the relationship between the interactants, the values of the cultural context in which the interaction unfolds, the emotional state of the interactants, and a number of other such variables no doubt influence effectiveness and appropriateness. Perception of competence in a particular situation is arguably a combination of culture-general and contextual variables. However, the aforementioned “culture-general” variables have been consistently associated with perceived ICC by people of different cultures. Hence they are noteworthy. The culture-general nature of some of the variables that contribute to intercultural competence provides an optimistic perspective that, even in the absence of culture-specific knowledge, it is possible for one to engage in effective and appropriate intercultural communication. Witteborn ( 2003 ) observed that the majority of models of intercultural competence take a culture-general approach. What is lacking at present, however, is extensive testing of these models to verify their culture-general nature.

The extent to which the culture-general nature of intercultural competence can be empirically verified depends on our ability to assess the variables identified in these models, and assessing intercultural competence itself. To this end, a discussion of assessment is warranted.

Assessing Intercultural Competence

Researchers have employed both quantitative and qualitative techniques in the assessment of intercultural competence. Deardorff ( 2006 ) proposed that intercultural competence should be measured progressively (at different points in time, over a period of time) and using multiple methods.

In terms of quantitative assessment, the nature of intercultural competence is such that any measure of this concept has to be one that (conceptually) translates across different cultures. Van de Vijver and Leung ( 1997 ) identified three biases that must be considered when using a quantitative instrument across cultures. First, there is potential for construct biases where cultural interpretations of a particular construct might vary. For example, “personal success” might be defined in terms of affluence, job prestige, etc., in an individualistic culture that favors capitalism, while the same construct could be defined in terms of sense of personal contribution and family validation in a collectivistic culture (Arasaratnam, 2007 ). Second, a method bias could be introduced by the very choice of the use of a quantitative instrument in a culture that might not be familiar with quantifying abstract concepts. Third, the presence of an item that is irrelevant to a particular cultural group could introduce an item bias when that instrument is used in research involving participants from multiple cultural groups. For a more detailed account of equivalence and biases that must be considered in intercultural research, see Van de Vijver and Leung ( 2011 ).

Over the years, many attempts have been made to develop quantitative measures of intercultural competence. There are a number of instruments that have been designed to measure intercultural competence or closely related concepts. A few of the more frequently used ones are worth noting.

Based on the Developmental Model of Intercultural Sensitivity (DMIS) (Bennett, 1986 ), the Intercultural Development Inventory (IDI) measures three ethnocentric and three ethno-relative levels of orientation toward cultural differences, as identified in the DMIS model (Hammer, Bennett, & Wiseman, 2003 ). This instrument is widely used in intercultural research, in several disciplines. Some examples of empirical studies that use IDI include Greenholtz ( 2000 ), Sample ( 2013 ), and Wang ( 2013 ).

The Intercultural Sensitivity Inventory (ICSI) is another known instrument that approaches intercultural competence from the perspective of a person’s ability to appropriately modify his or her behavior when confronted with cultural differences, specifically as they pertain to individualistic and collectivistic cultures (Bhawuk & Brislin, 1992 ). It must be noted, however, that intercultural sensitivity is not necessarily equivalent to intercultural competence. Chen and Starosta ( 2000 ), for example, argued that intercultural sensitivity is a pre-requisite for intercultural competence rather than its conceptual equivalent. As such, Chen and Starosta’s Intercultural Sensitivity scale should be viewed within the same parameters. The authors view intercultural sensitivity as the affective dimension of intercultural competence (Chen & Starosta, 1997 ).

Although not specifically designed to measure intercultural competence, the Multicultural Personality Questionnaire (MPQ) measures five dimensions, namely open mindedness, emotional stability, cultural empathy, social initiative, and flexibility (Van Oudenhoven & Van der Zee, 2002 ), all of which have been found to be directly related to intercultural competence, in other research (see Matsumoto & Hwang, 2013 ).

Quantitative measures of intercultural competence almost exclusively rely on self-ratings. As such, they bear the strengths and weaknesses of any self-report (for a detailed discussion of self-knowledge, see Bauer & Baumeister, 2013 ). There is some question as to whether Likert-type scales favor individuals with higher cognitive complexity because such persons have a greater capacity for differentiating between constructs (Bowler, Bowler, & Cope, 2012 ). Researchers have also used other methods such as portfolios, reflective journals, responses to hypothetical scenarios, and interviews. There continues to be a need for fine-tuned methods of assessing intercultural competence that utilize others’ perceptions in addition to self-reports.

Can Intercultural Competence Be Learned?

If competence is the holy grail of intercultural communication, then the question is whether it can be learned. On the one hand, many researchers suggest that the process of learning intercultural competence is developmental (Beamer, 1992 ; Bennett, 1986 ; Hammer, Bennett, & Wiseman, 2003 ). Which means that over time, experiences, and deliberate reflection, people can learn things that cumulatively contribute to intercultural competence. Evidence also suggests that collaborative learning facilitates the development of intercultural competence (Helm, 2009 ; Zhang, 2012 ). On the other hand, given research shows that there are many personality variables that contribute to intercultural competence; one could question whether these are innate or learned. Further, many causal models of intercultural competence show that intercultural competence is the product of interactions between many variables. If some of these can be learned and others are innate, then it stands to reason that, given equal learning opportunities, there would still be variations in the extent to which one “achieves” competence. There is also evidence to suggest that there are certain variables, such as ethnocentrism, that debilitate intercultural competence. Thus, it is fair to conclude that, while there is the potential for one to improve one’s intercultural competence through learning, not all can or will.

The aforementioned observation has implications for intercultural training, particularly training that relies heavily on dissemination of knowledge alone. In other words, just because someone knows facts about intercultural competence, it does not necessarily make them an expert at effective and appropriate communication. Developmental models of intercultural competence suggest that the learning process is progressive over time, based on one’s reaction to various experiences and one’s ability to reflect on new knowledge (Saunders, Haskins, & Vasquez et al., 2015 ). Further, research shows that negative attitudes and attitudes that are socially reinforced are the hardest to change (Bodenhausen & Gawronski, 2013 ). Hence people with negative prejudices toward other cultures, for example, may not necessarily be affected by an intercultural training workshop. While many organizations have implemented intercultural competency training in employee education as a nod to embracing diversity, the effectiveness of short, skilled-based training bears further scrutiny. For more on intercultural training, see the Handbook of Intercultural Training by Landis, Bennett, and Bennett ( 2004 ).

Research Directions