- Manuscript Preparation

Differentiating between the abstract and the introduction of a research paper

- 3 minute read

- 48.5K views

Table of Contents

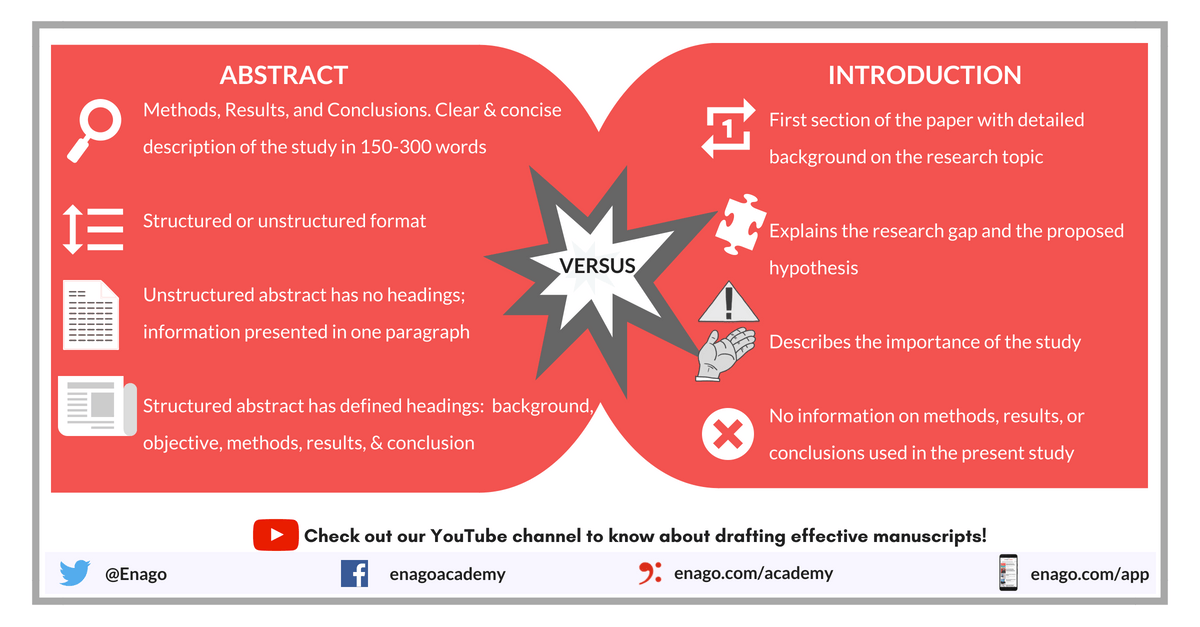

While writing a manuscript for the first time, you might find yourself confused about the differences between an abstract and the introduction. Both are adjacent sections of a research paper and share certain elements. However, they serve entirely different purposes. So, how does one ensure that these sections are written correctly?

Knowing the intended purpose of the abstract and the introduction is a good start!

What is an abstract?

An abstract is a very short summary of all the sections of your research paper—the introduction, objectives, materials and methods, results, and conclusion. It ends by emphasising the novelty or relevance of your study, or by posing questions for future research. The abstract should cover all important aspects of the study, so that the reader can quickly decide if the paper is of their interest or not.

In simple terms, just like a restaurant’s menu that provides an overview of all available dishes, an abstract gives the reader an idea of what the research paper has to offer. Most journals have a strict word limit for abstracts, which is usually 10% of the research paper.

What is the purpose of an abstract?

The abstract should ideally induce curiosity in the reader’s mind and contain strategic keywords. By generating curiosity and interest, an abstract can push readers to read the entire paper or buy it if it is behind a paywall. By using keywords strategically in the abstract, authors can improve the chances of their paper appearing in online searches.

What is an introduction?

The introduction is the first section in a research paper after the abstract, which describes in detail the background information that is necessary for the reader to understand the topic and aim of the study.

What is the purpose of an introduction?

The introduction points to specific gaps in knowledge and explains how the study addresses these gaps. It lists previous studies in a chronological order, complete with citations, to explain why the study was warranted.

A good introduction sets the context for your study and clearly distinguishes between the knowns and the unknowns in a research topic.

Often, the introduction mentions the materials and methods used in a study and outlines the hypotheses tested. Both the abstract and the introduction have this in common. So, what are the key differences between the two sections?

Key differences between an abstract and the introduction:

- The word limit for an abstract is usually 250 words or less. In contrast, the typical word limit for an introduction is 500 words or more.

- When writing the abstract, it is essential to use keywords to make the paper more visible to search engines. This is not a significant concern when writing the introduction.

- The abstract features a summary of the results and conclusions of your study, while the introduction does not. The abstract, unlike the introduction, may also suggest future directions for research.

- While a short review of previous research features in both the abstract and the introduction, it is more elaborate in the latter.

- All references to previous research in the introduction come with citations. The abstract does not mention specific studies, although it may briefly outline previous research.

- The abstract always comes before the introduction in a research paper.

- Every paper does not need an abstract. However, an introduction is an essential component of all research papers.

If you are still confused about how to write the abstract and the introduction of your research paper while accounting for the differences between them, head over to Elsevier Author Services . Our experts will be happy to guide you throughout your research journey, with useful advice on how to write high quality research papers and get them published in reputed journals!

- Research Process

Scholarly Sources: What are They and Where can You Find Them?

What are Implications in Research?

You may also like.

Page-Turner Articles are More Than Just Good Arguments: Be Mindful of Tone and Structure!

A Must-see for Researchers! How to Ensure Inclusivity in Your Scientific Writing

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

Abstract Vs. Introduction — Do you know the difference?

Ross wants to publish his research. Feeling positive about his research outcomes, he begins to draft his manuscript. After completing the abstract, he proceeds to write the introduction. That’s when he pauses in confusion. Do the abstract and introduction mean the same? How is the content for both the sections different?

This is a dilemma faced by several young researchers while drafting their first manuscript. An abstract is similar to a summary except that it is more concise and direct. Whereas, the introduction section of your paper is more detailed. It states why you conducted your study, what you wanted to accomplish, and what is your hypothesis.

This blog will allow us to learn more about the difference between the abstract and the introduction.

What Is an Abstract for a Research Paper?

An abstract provides the reader with a clear description of your research study and its results without the reader having to read the entire paper. The details of a study, such as precise methods and measurements, are not necessarily mentioned in the abstract. The abstract is an important tool for researchers who must sift through hundreds of papers from their field of study.

The abstract holds more significance in articles without open access. Reading the abstract would give an idea of the articles, which would otherwise require monetary payment for access. In most cases, reviewers will read the abstract to decide whether to continue to review the paper, which is important for you.

Your abstract should begin with a background or objective to clearly state why the research was done, its importance to the field of study, and any previous roadblocks encountered. It should include a very concise version of your methods, results, and conclusions but no references. It must be brief while still providing enough information so that the reader need not read the full article. Most journals ask that the abstract be no more than 200–250 words long.

Format of an Abstract

There are two general formats — structured and unstructured. A structured abstract helps the reader find pertinent information very quickly. It is divided into sections clearly defined by headings as follows:

- Background : Latest information on the topic; key phrases that pique interest (e.g., “…the role of this enzyme has never been clearly understood”).

- Objective : The research goals; what the study examined and why.

- Methods : Brief description of the study (e.g., retrospective study).

- Results : Findings and observations.

- Conclusions : Were these results expected? Whether more research is needed or not?

Authors get tempted to write too much in an abstract but it is helpful to remember that there is usually a maximum word count. The main point is to relay the important aspects of the study without sharing too many details so that the readers do not have to go through the entire manuscript text for finding more information.

The unstructured abstract is often used in fields of study that do not fall under the category of science. This type of abstracts does not have different sections. It summarizes the manuscript’s objectives, methods, etc., in one paragraph.

Related: Create an impressive manuscript with a compelling abstract. Check out these resources and improve your abstract writing process!

Lastly, you must check the author guidelines of the target journal. It will describe the format required and the maximum word count of your abstract.

What Is an Introduction?

Your introduction is the first section of your research paper . It is not a repetition of the abstract. It does not provide data about methods, results, or conclusions. However, it provides more in-depth information on the background of the subject matter. It also explains your hypothesis , what you attempted to discover, or issues that you wanted to resolve. The introduction will also explain if and why your study is new in the subject field and why it is important.

It is often a good idea to wait until the rest of the paper is completed before drafting your introduction. This will help you to stay focused on the manuscript’s important points. The introduction, unlike the abstract, should contain citations to references. The information will help guide your readers through the rest of your document. The key tips for writing an effective introduction :

- Beginning: The importance of the study.

- Tone/Tense: Formal, impersonal; present tense.

- Content: Brief description of manuscript but without results and conclusions.

- Length: Generally up to four paragraphs. May vary slightly with journal guidelines.

Once you are sure that possible doubts on the difference between the abstract and introduction are clear, review and submit your manuscript.

What struggles have you had in writing an abstract or introduction? Were you able to resolve them? Please share your thoughts with us in the comments section below.

Insightful and educating Indeed. Thank You

Quite a helpful and precise for scholars and students alike. Keep it up…

thanks! very helpful.

thanks. helped

Greeting from Enago Academy! Thank you for your positive comment. We are glad to know that you found our resources useful. Your feedback is very valuable to us. Happy reading!

Really helpful as I prepare to write the introduction to my dissertation. Thank you Enago Academy

This gave me more detail finding the pieces of a research article being used for a critique paper in nursing school! thank you!

The guidelines have really assisted me with my assignment on writing argument essay on social media. The difference between the abstract and introduction is quite clear now for me to start my essay…thank you so much…

Quite helpful! I’m writing a paper on eyewitness testimony for one of my undergraduate courses at the University of Northern Colorado, and found this to be extremely helpful in clarifications

This was hugely helpful. Keep up the great work!

This was quite helpful. Keep it up!

Very comprehensive and simple. thanks

As a student, this website has helped me greatly to understand how to formally report my research

Thanks a lot.I can now handle my doubts after reading through.

thanks alot! this website has given me huge clarification on writing a good Introduction and Abttract i really appreciate what you share!. hope to see more to come1 God bless you.

Thank you, this was very helpful for writing my research paper!

That was helpful. geed job.

Thank you very much. This article really helped with my assignment.

Woohoo! Amazing. I couldnt stop listening to the audio; so enlightening.

Thank you for such a clear breakdown!

I am grateful for the assistance rendered me. I was mystified over the difference between an abstract and introduction during thesis writing. Now I have understood the concept theoretically, I will put that in practice. So thanks a lots it is great help to me.

Rate this article Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Enago Academy's Most Popular Articles

- AI in Academia

- Infographic

- Manuscripts & Grants

- Reporting Research

- Trending Now

Can AI Tools Prepare a Research Manuscript From Scratch? — A comprehensive guide

As technology continues to advance, the question of whether artificial intelligence (AI) tools can prepare…

- Old Webinars

- Webinar Mobile App

Demystifying Research Methodology With Field Experts

Choosing research methodology Research design and methodology Evidence-based research approach How RAxter can assist researchers

- Manuscript Preparation

- Publishing Research

How to Choose Best Research Methodology for Your Study

Successful research conduction requires proper planning and execution. While there are multiple reasons and aspects…

Top 5 Key Differences Between Methods and Methodology

While burning the midnight oil during literature review, most researchers do not realize that the…

如何准备高质量的金融和科技领域学术论文

如何寻找原创研究课题 快速定位目标文献的有效搜索策略 如何根据期刊指南准备手稿的对应部分 论文手稿语言润色实用技巧分享

How to Draft the Acknowledgment Section of a Manuscript

Discussion Vs. Conclusion: Know the Difference Before Drafting Manuscripts

Annex Vs. Appendix: Do You Know the Difference?

Sign-up to read more

Subscribe for free to get unrestricted access to all our resources on research writing and academic publishing including:

- 2000+ blog articles

- 50+ Webinars

- 10+ Expert podcasts

- 50+ Infographics

- 10+ Checklists

- Research Guides

We hate spam too. We promise to protect your privacy and never spam you.

I am looking for Editing/ Proofreading services for my manuscript Tentative date of next journal submission:

As a researcher, what do you consider most when choosing an image manipulation detector?

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

Abstract vs. Introduction—What’s the Difference?

3-minute read

- 21st February 2022

If you’re a student who’s new to research papers or you’re preparing to write your dissertation , you might be wondering what the difference is between an abstract and an introduction.

Both serve important purposes in a research paper or journal article , but they shouldn’t be confused with each other. We’ve put together this guide to help you tell them apart.

What’s an Introduction?

In an academic context, an introduction is the first section of an essay or research paper. It should provide detailed background information about the study and its significance, as well as the researcher’s hypotheses and aims.

But the introduction shouldn’t discuss the study’s methods or results. There are separate sections for this later in the paper.

An introduction must correctly cite all sources used and should be about four paragraphs long, although the exact length depends on the topic and the style guide used.

What’s an Abstract?

While the introduction is the first section of a research paper, the abstract is a short summary of the entire paper. It should contain enough basic information to allow you to understand the content of the study without having to read the entire paper.

The abstract is especially important if the paper isn’t open access because it allows researchers to sift through many different studies before deciding which one to pay for.

Since the abstract contains only the essentials, it’s usually much shorter than an introduction and normally has a maximum word count of 200–300 words. It also doesn’t contain citations.

The exact layout of an abstract depends on whether it’s structured or unstructured. Unstructured abstracts are usually used in non-scientific disciplines, such as the arts and humanities, and usually consist of a single paragraph.

Structured abstracts, meanwhile, are the most common form of abstract used in scientific papers. They’re divided into different sections, each with its own heading. We’ll take a closer look at structured abstracts below.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Structuring an Abstract

A structured abstract contains concise information in a clear format with the following headings:

● Background: Here you’ll find some relevant information about the topic being studied, such as why the study was necessary.

● Objectives: This section is about the goals the researcher has for the study.

● Methods: Here you’ll find a summary of how the study was conducted.

● Results: Under this heading, the results of the study are presented.

● Conclusions: The abstract ends with the researcher’s conclusions and how the study can inform future research.

Each of these sections, however, should contain less detail than the introduction or other sections of the main paper.

Academic Proofreading

Whether you need help formatting your structured abstract or making sure your introduction is properly cited, our academic proofreading team is available 24/7. Try us out by submitting a free trial document .

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- Key Differences

Know the Differences & Comparisons

Difference Between Abstract and Introduction

On the other hand, the abstract is like a short summary of an academic article or research paper, which discusses the purpose of the study and the outcome of the research. It usually summarizes the research topic, questions, participants, methods, outcome, data collected, analysis and conclusions. The article excerpt given hereunder discusses the difference between abstract and introduction.

Content: Abstract Vs Introduction

Comparison chart, definition of abstract.

An abstract can be described as a concise summary, often found in research work like thesis, dissertations, research articles, review, etc. which helps the reader to have an instant idea of the main purpose of the work. It is about a paragraph long of 150 to 250 words in general.

The information contained in the abstract should be sufficient enough to help the readers judge the nature and importance of the topic, the reasonableness of the strategy used in the investigation, nature of results and conclusions.

An abstract serves a number of purposes such as it allows the readers to get the gist of your paper, so as to decide whether to go through with the rest of the work. It is usually written after the writing of the paperwork is over and that too in the past tense.

An abstract rolls all the important information of the work into a single page, such as the context, general topic, central questions, problem under study, main idea, previous research findings, reasons, research methodology, findings, results, arguments, implications, conclusion and so on. To create an abstract one should pick the main statements from the above-mentioned sections, to draft an abstract.

Types of Abstract

- Descriptive Abstract : It briefly describes the abstract and the length is usually 100-200 words. It indicates the type of information contained in the paper, discusses the purpose of writing, objectives and methods used for research.

- Informative Abstract : As the name suggests, it is a detailed abstract which summarizes all the important points of the study. It includes results and conclusions, along with the purpose, objective, and methods used.

Definition of Introduction

Introduction means to present something to the readers, i.e. by giving a brief description or background information of the document. It is the first and foremost section which expresses the purpose, scope and goals, concerning the topic under study. As an introduction gives an overview of the topic, it develops an understanding of the main text.

An introduction is a gateway to the topic, as it is something which can create interest in the readers to read the document further. It is the crux of the document, which states what is to be discussed in the main body.

Elements of Introduction

An introduction has four basic elements namely: hook, background information, connect and thesis statement.

- Hook is the preliminary sentence of the introduction which is used to fasten the attention of the readers, and so it has to be interesting, attention-grabbing, and readable of course, so as to stimulate the readers to read the complete text.

- Background Information is the main part of the introduction, which presents the background of the research topic, including the problem under study, real-world situation, research questions, and a sneak peek of what the readers can expect from the main body.

- Connect , is a simple line which is used to link or say relate the background information with the research statement, by using words ideas or phrases, so as to ensure the flow and logic of writing the text.

- Thesis statement is the central point of the argument, which is usually a single sentence, whose points of evidence are to be talked about in the following text, i.e. the main body.

Key Differences Between Abstract and Introduction

The difference between abstract and introduction are discussed in the points:

- An abstract is a concise and accurate representation which gives an overview of the main points from the entire document. On the other hand, Introduction is the first section which makes the reader aware of the subject, by giving a brief description of the work, i.e. why the research is needed or important.

- While an abstract will give you an immediate overview of the paper, the introduction is the initial exposure to the subject under study.

- An abstract reports key points of the research, as well as it states why the work is important, what was the main purpose of research, what is the motivation behind choosing the subject, what you learned from the research, what you found out during the research and what you concluded, in a summarized way. As against, an introduction presents a direction to understand what exists in the upcoming portion of the document or book.

- As an abstract has its own introduction, main body and conclusion, it is a standalone document which summarizes the result of the findings and not just the list of topics discussed. As against, the introduction is not a standalone document or piece.

- The main purpose of an abstract is to provide a succinct summary of the research. Conversely, introduction aims at convincing the reader about the need for the research.

- An abstract contains the purpose, problem, methods used, result and conclusion. On the contrary, the introduction includes a hook, background information, connect and thesis statement.

- While abstract is found in a research paper, thesis and dissertations, the introduction is found in a wide range of texts.

An abstract gives a preview of the work, outlines the main points and helps the audience in decision making, i.e. whether they want to read the complete text or not. On the other hand, an introduction is the very first section of the work, which clarifies the purpose of writing.

Without an abstract and introduction, the readers might not be able to know what the work contains and what is the reason or motivation behind the research. So, these two are like thread which goes through the writing and creates an understanding in the reader about the topic under study. While writing these two, one should ensure that they accurately reflect what you cover in the document or book.

You Might Also Like:

Edward says

September 20, 2023 at 1:15 am

fantastic explanations

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- How to Write an Abstract for a Dissertation or Thesis

- Doing a PhD

What is a Thesis or Dissertation Abstract?

The Cambridge English Dictionary defines an abstract in academic writing as being “ a few sentences that give the main ideas in an article or a scientific paper ” and the Collins English Dictionary says “ an abstract of an article, document, or speech is a short piece of writing that gives the main points of it ”.

Whether you’re writing up your Master’s dissertation or PhD thesis, the abstract will be a key element of this document that you’ll want to make sure you give proper attention to.

What is the Purpose of an Abstract?

The aim of a thesis abstract is to give the reader a broad overview of what your research project was about and what you found that was novel, before he or she decides to read the entire thesis. The reality here though is that very few people will read the entire thesis, and not because they’re necessarily disinterested but because practically it’s too large a document for most people to have the time to read. The exception to this is your PhD examiner, however know that even they may not read the entire length of the document.

Some people may still skip to and read specific sections throughout your thesis such as the methodology, but the fact is that the abstract will be all that most read and will therefore be the section they base their opinions about your research on. In short, make sure you write a good, well-structured abstract.

How Long Should an Abstract Be?

If you’re a PhD student, having written your 100,000-word thesis, the abstract will be the 300 word summary included at the start of the thesis that succinctly explains the motivation for your study (i.e. why this research was needed), the main work you did (i.e. the focus of each chapter), what you found (the results) and concluding with how your research study contributed to new knowledge within your field.

Woodrow Wilson, the 28th President of the United States of America, once famously said:

The point here is that it’s easier to talk open-endedly about a subject that you know a lot about than it is to condense the key points into a 10-minute speech; the same applies for an abstract. Three hundred words is not a lot of words which makes it even more difficult to condense three (or more) years of research into a coherent, interesting story.

What Makes a Good PhD Thesis Abstract?

Whilst the abstract is one of the first sections in your PhD thesis, practically it’s probably the last aspect that you’ll ending up writing before sending the document to print. The reason being that you can’t write a summary about what you did, what you found and what it means until you’ve done the work.

A good abstract is one that can clearly explain to the reader in 300 words:

- What your research field actually is,

- What the gap in knowledge was in your field,

- The overarching aim and objectives of your PhD in response to these gaps,

- What methods you employed to achieve these,

- You key results and findings,

- How your work has added to further knowledge in your field of study.

Another way to think of this structure is:

- Introduction,

- Aims and objectives,

- Discussion,

- Conclusion.

Following this ‘formulaic’ approach to writing the abstract should hopefully make it a little easier to write but you can already see here that there’s a lot of information to convey in a very limited number of words.

How Do You Write a Good PhD Thesis Abstract?

The biggest challenge you’ll have is getting all the 6 points mentioned above across in your abstract within the limit of 300 words . Your particular university may give some leeway in going a few words over this but it’s good practice to keep within this; the art of succinctly getting your information across is an important skill for a researcher to have and one that you’ll be called on to use regularly as you write papers for peer review.

Keep It Concise

Every word in the abstract is important so make sure you focus on only the key elements of your research and the main outcomes and significance of your project that you want the reader to know about. You may have come across incidental findings during your research which could be interesting to discuss but this should not happen in the abstract as you simply don’t have enough words. Furthermore, make sure everything you talk about in your thesis is actually described in the main thesis.

Make a Unique Point Each Sentence

Keep the sentences short and to the point. Each sentence should give the reader new, useful information about your research so there’s no need to write out your project title again. Give yourself one or two sentences to introduce your subject area and set the context for your project. Then another sentence or two to explain the gap in the knowledge; there’s no need or expectation for you to include references in the abstract.

Explain Your Research

Some people prefer to write their overarching aim whilst others set out their research questions as they correspond to the structure of their thesis chapters; the approach you use is up to you, as long as the reader can understand what your dissertation or thesis had set out to achieve. Knowing this will help the reader better understand if your results help to answer the research questions or if further work is needed.

Keep It Factual

Keep the content of the abstract factual; that is to say that you should avoid bringing too much or any opinion into it, which inevitably can make the writing seem vague in the points you’re trying to get across and even lacking in structure.

Write, Edit and Then Rewrite

Spend suitable time editing your text, and if necessary, completely re-writing it. Show the abstract to others and ask them to explain what they understand about your research – are they able to explain back to you each of the 6 structure points, including why your project was needed, the research questions and results, and the impact it had on your research field? It’s important that you’re able to convey what new knowledge you contributed to your field but be mindful when writing your abstract that you don’t inadvertently overstate the conclusions, impact and significance of your work.

Thesis and Dissertation Abstract Examples

Perhaps the best way to understand how to write a thesis abstract is to look at examples of what makes a good and bad abstract.

Example of A Bad Abstract

Let’s start with an example of a bad thesis abstract:

In this project on “The Analysis of the Structural Integrity of 3D Printed Polymers for use in Aircraft”, my research looked at how 3D printing of materials can help the aviation industry in the manufacture of planes. Plane parts can be made at a lower cost using 3D printing and made lighter than traditional components. This project investigated the structural integrity of EBM manufactured components, which could revolutionise the aviation industry.

What Makes This a Bad Abstract

Hopefully you’ll have spotted some of the reasons this would be considered a poor abstract, not least because the author used up valuable words by repeating the lengthy title of the project in the abstract.

Working through our checklist of the 6 key points you want to convey to the reader:

- There has been an attempt to introduce the research area , albeit half-way through the abstract but it’s not clear if this is a materials science project about 3D printing or is it about aircraft design.

- There’s no explanation about where the gap in the knowledge is that this project attempted to address.

- We can see that this project was focussed on the topic of structural integrity of materials in aircraft but the actual research aims or objectives haven’t been defined.

- There’s no mention at all of what the author actually did to investigate structural integrity. For example was this an experimental study involving real aircraft, or something in the lab, computer simulations etc.

- The author also doesn’t tell us a single result of his research, let alone the key findings !

- There’s a bold claim in the last sentence of the abstract that this project could revolutionise the aviation industry, and this may well be the case, but based on the abstract alone there is no evidence to support this as it’s not even clear what the author did .

This is an extreme example but is a good way to illustrate just how unhelpful a poorly written abstract can be. At only 71 words long, it definitely hasn’t maximised the amount of information that could be presented and the what they have presented has lacked clarity and structure.

A final point to note is the use of the EBM acronym, which stands for Electron Beam Melting in the context of 3D printing; this is a niche acronym for the author to assume that the reader would know the meaning of. It’s best to avoid acronyms in your abstract all together even if it’s something that you might expect most people to know about, unless you specifically define the meaning first.

Example of A Good Abstract

Having seen an example of a bad thesis abstract, now lets look at an example of a good PhD thesis abstract written about the same (fictional) project:

Additive manufacturing (AM) of titanium alloys has the potential to enable cheaper and lighter components to be produced with customised designs for use in aircraft engines. Whilst the proof-of-concept of these have been promising, the structural integrity of AM engine parts in response to full thrust and temperature variations is not clear.

The primary aim of this project was to determine the fracture modes and mechanisms of AM components designed for use in Boeing 747 engines. To achieve this an explicit finite element (FE) model was developed to simulate the environment and parameters that the engine is exposed to during flight. The FE model was validated using experimental data replicating the environmental parameters in a laboratory setting using ten AM engine components provided by the industry sponsor. The validated FE model was then used to investigate the extent of crack initiation and propagation as the environment parameters were adjusted.

This project was the first to investigate fracture patterns in AM titanium components used in aircraft engines; the key finding was that the presence of cavities within the structures due to errors in the printing process, significantly increased the risk of fracture. Secondly, the simulations showed that cracks formed within AM parts were more likely to worsen and lead to component failure at subzero temperatures when compared to conventionally manufactured parts. This has demonstrated an important safety concern which needs to be addressed before AM parts can be used in commercial aircraft.

What Makes This a Good Abstract

Having read this ‘good abstract’ you should have a much better understand about what the subject area is about, where the gap in the knowledge was, the aim of the project, the methods that were used, key results and finally the significance of these results. To break these points down further, from this good abstract we now know that:

- The research area is around additive manufacturing (i.e. 3D printing) of materials for use in aircraft.

- The gap in knowledge was how these materials will behave structural when used in aircraft engines.

- The aim was specifically to investigate how the components can fracture.

- The methods used to investigate this were a combination of computational and lab based experimental modelling.

- The key findings were the increased risk of fracture of these components due to the way they are manufactured.

- The significance of these findings were that it showed a potential risk of component failure that could comprise the safety of passengers and crew on the aircraft.

The abstract text has a much clearer flow through these different points in how it’s written and has made much better use of the available word count. Acronyms have even been used twice in this good abstract but they were clearly defined the first time they were introduced in the text so that there was no confusion about their meaning.

The abstract you write for your dissertation or thesis should succinctly explain to the reader why the work of your research was needed, what you did, what you found and what it means. Most people that come across your thesis, including any future employers, are likely to read only your abstract. Even just for this reason alone, it’s so important that you write the best abstract you can; this will not only convey your research effectively but also put you in the best light possible as a researcher.

Browse PhDs Now

Join thousands of students.

Join thousands of other students and stay up to date with the latest PhD programmes, funding opportunities and advice.

university writing center

Just another weblog

university writing center Pages

The difference between an abstract and an introduction.

Introductions and abstracts are two things that seem very similar, but are actually quite different. However, once you know the difference, they are easy to keep separate from each other.

An abstract is, at its most basic level, a summary. It outlines all of the important parts of your paper to the reader, so they can figure out if your paper is worth reading. This is why abstracts are important in the scientific field. They are a fast way for someone to analyze what is going to be said, and if that information is going to be beneficial for them.

An introduction provides the reader with detailed background information about a topic. This helps the reader make sense of what is going to be said later in the paper. If they do not understand the most basic parts of your topic, then they are not going to understand what you are trying to convey.

Now that you know the difference between the two, here is some advice for writing them:

The abstract is easiest to write last. By that point, you will have already written everything else, and you should know the important takeaways of your work. In the abstract, you should introduce your topic, discuss why you choose this topic, state your hypothesis, and reveal the results of your study. Remember, the abstract is like a summary. You should not go into a lot of detail here. Provide the reader with enough information that they can digest what you are saying. You will explain everything else in detail later in your paper.

The introduction is one of the most important parts of your paper. However, introductions vary based on the genre of paper. For this blog post, introductions for scientific papers are going to be discussed because abstracts are a staple of scientific reports. An introduction for a scientific paper should explain the reasoning behind why you choose this experiment, provide background information about the topic, reference other studies done on similar topics, and state your hypothesis. You want to make sure your reader can understand what is going to be said later in the paper.

Here are a few websites that have some more information about the two:

https://writingcenter.gmu.edu/writing-resources/different-genres/writing-an-abstract

https://writing.wisc.edu/handbook/assignments/writing-an-abstract-for-your-research-paper/

https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/graduate_writing/graduate_writing_genres/graduate_writing_genres_abstracts_new.html

Introduction:

https://guides.lib.uci.edu/c.php?g=334338&p=2249903

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4548565/

https://dept.writing.wisc.edu/wac/writing-an-introduction-for-a-scientific-paper/

https://abrilliantmind.blog/how-to-write-the-introduction-of-scientific-article/

An Abstract or an Introduction — What’s the Difference?

Are you working on a paper or scholarly article? Need to know the difference between an abstract and an introduction? Here’s what you need to know.

An abstract and an introduction are two different sections of a research paper, thesis, or dissertation. An abstract is a short summary of the entire piece, and it comes before the table of contents. An introduction is a full-length chapter, and often includes a layout of the rest of the piece.

Abstract vs. Introduction — Key Takeaways

An abstract.

- Can be very short — a basic abstract only needs four sentences.

- A summary of the entire work.

- Used in scholarly, academic, or scientific papers and articles.

- Comes before the table of contents. The page is not numbered.

An Introduction

- Is a full-length chapter.

- Often includes a map or layout of the piece to come.

- Found in papers, articles, books, essays, compendiums, and more.

- After the table of contents. Considered a part of the work itself.

An abstract is a brief summary of the entire paper, that provides a concise overview of the research question, methods, results, and conclusions. According to the Chicago Manual of Style, an abstract may be “as many as a few hundred words but often much shorter.”

It should be able to stand alone as a summary of the paper, allowing readers to quickly determine whether the paper is relevant to their interests.

An Example Abstract Format

For those in the sciences, the American Medical Association says, “Abstracts should summarize the main point(s) of an article and include the objective, methods, results, and conclusions of a study.”

In the arts and humanities — my field — a basic abstract format includes four statements:

- They say/I say

Methodology

What do these all mean? Let’s dive in.

They Say/I say

This is where you position your research within the broader field of scholarship. For example:

Many scholars believe that vampires don’t like sunshine (they say), but most aren’t considering all the vampires who do like sunshine (I say). Tweet

This is where you discuss the kind of research you did. For example:

Over the course of one year, I trekked across Transylvania looking at ancient records and interviewing contemporary vampires.

This is where you summarize the main argument (thesis) that your paper asserts. For example:

This paper reveals that 77% of vampires do in fact tolerate or even enjoy sunshine.

The takeaway answers the question, So what? This is where you make a case for the broader implications of your claim. For example:

By understanding the diurnal (daytime) nature of most vampires, we can renovate our understanding of their culture and begin to break down barriers between vampires and non-vampires.

Introductions

As opposed to an abstract, which comes before a paper, the introduction is the first section of the paper , which introduces the research question, provides background information on the topic, and outlines the purpose and objectives of the study. The introduction sets the stage for the research and helps readers understand why the research was conducted and what it hopes to achieve. I had a professor who used to say that the introduction “sets the table for the meal of the paper to come.”

Information from the abstract may appear in the introduction, but it will be expanded upon and more detailed.

The Format of an Introduction

An introduction, unlike most abstracts, will contain multiple paragraphs. While the abstract comes before the table of contents, the introduction comes after, and, according to the Oxford Style guide and common academic practice, begins on page #1.

An introduction will often include the following information:

- Opening Gambit — An anecdote, joke, personal narrative, etc. to ‘hook’ the reader.

- They Say/I say — Position your work in the broader field of study. This will be more fleshed out than in the abstract.

- Thesis Statement — Your main argument.

- Methodology — An overview of the kind of research you conducted. (Note that the methodology comes after the thesis statement in an introduction, unlike in the abstract.)

- Map of the Paper — This is where you tell your reader what to expect from each section of the paper. “In chapter 1, I look at…” etc.

- Restate the Thesis — Restate your main argument.

As to the “map of the paper,” I should note that not everyone agrees on this — the Chicago Manual of Style advises against it. And yet, it is a common academic practice. When in doubt, always check with your teacher or publisher.

Abstracts and Introductions

The main difference between an abstract and an introduction is that an abstract is a brief summary of the entire paper which appears before the table of contents, while an introduction provides a more in-depth view of the research question, background information, and the purpose of the study. Unlike abstracts, many introductions include a map of the paper that follows.

Need Help with Abstracts, Introductions, and More?

EditorNinja is here to help! We’re a team of professional content editors, across line editing, copy editing, and proofreading. All EditorNinja editors are MFA trained and look forward to editing your written content!

Schedule a free editorial assessment today to see how using EditorNinja can save you days of time, buy back hours that you can use to create more content or work on other things, and make on average a 3.5x ROI, or at least $12,000+, on your investment.

What this handout is about

This handout provides definitions and examples of the two main types of abstracts: descriptive and informative. It also provides guidelines for constructing an abstract and general tips for you to keep in mind when drafting. Finally, it includes a few examples of abstracts broken down into their component parts.

What is an abstract?

An abstract is a self-contained, short, and powerful statement that describes a larger work. Components vary according to discipline. An abstract of a social science or scientific work may contain the scope, purpose, results, and contents of the work. An abstract of a humanities work may contain the thesis, background, and conclusion of the larger work. An abstract is not a review, nor does it evaluate the work being abstracted. While it contains key words found in the larger work, the abstract is an original document rather than an excerpted passage.

Why write an abstract?

You may write an abstract for various reasons. The two most important are selection and indexing. Abstracts allow readers who may be interested in a longer work to quickly decide whether it is worth their time to read it. Also, many online databases use abstracts to index larger works. Therefore, abstracts should contain keywords and phrases that allow for easy searching.

Say you are beginning a research project on how Brazilian newspapers helped Brazil’s ultra-liberal president Luiz Ignácio da Silva wrest power from the traditional, conservative power base. A good first place to start your research is to search Dissertation Abstracts International for all dissertations that deal with the interaction between newspapers and politics. “Newspapers and politics” returned 569 hits. A more selective search of “newspapers and Brazil” returned 22 hits. That is still a fair number of dissertations. Titles can sometimes help winnow the field, but many titles are not very descriptive. For example, one dissertation is titled “Rhetoric and Riot in Rio de Janeiro.” It is unclear from the title what this dissertation has to do with newspapers in Brazil. One option would be to download or order the entire dissertation on the chance that it might speak specifically to the topic. A better option is to read the abstract. In this case, the abstract reveals the main focus of the dissertation:

This dissertation examines the role of newspaper editors in the political turmoil and strife that characterized late First Empire Rio de Janeiro (1827-1831). Newspaper editors and their journals helped change the political culture of late First Empire Rio de Janeiro by involving the people in the discussion of state. This change in political culture is apparent in Emperor Pedro I’s gradual loss of control over the mechanisms of power. As the newspapers became more numerous and powerful, the Emperor lost his legitimacy in the eyes of the people. To explore the role of the newspapers in the political events of the late First Empire, this dissertation analyzes all available newspapers published in Rio de Janeiro from 1827 to 1831. Newspapers and their editors were leading forces in the effort to remove power from the hands of the ruling elite and place it under the control of the people. In the process, newspapers helped change how politics operated in the constitutional monarchy of Brazil.

From this abstract you now know that although the dissertation has nothing to do with modern Brazilian politics, it does cover the role of newspapers in changing traditional mechanisms of power. After reading the abstract, you can make an informed judgment about whether the dissertation would be worthwhile to read.

Besides selection, the other main purpose of the abstract is for indexing. Most article databases in the online catalog of the library enable you to search abstracts. This allows for quick retrieval by users and limits the extraneous items recalled by a “full-text” search. However, for an abstract to be useful in an online retrieval system, it must incorporate the key terms that a potential researcher would use to search. For example, if you search Dissertation Abstracts International using the keywords “France” “revolution” and “politics,” the search engine would search through all the abstracts in the database that included those three words. Without an abstract, the search engine would be forced to search titles, which, as we have seen, may not be fruitful, or else search the full text. It’s likely that a lot more than 60 dissertations have been written with those three words somewhere in the body of the entire work. By incorporating keywords into the abstract, the author emphasizes the central topics of the work and gives prospective readers enough information to make an informed judgment about the applicability of the work.

When do people write abstracts?

- when submitting articles to journals, especially online journals

- when applying for research grants

- when writing a book proposal

- when completing the Ph.D. dissertation or M.A. thesis

- when writing a proposal for a conference paper

- when writing a proposal for a book chapter

Most often, the author of the entire work (or prospective work) writes the abstract. However, there are professional abstracting services that hire writers to draft abstracts of other people’s work. In a work with multiple authors, the first author usually writes the abstract. Undergraduates are sometimes asked to draft abstracts of books/articles for classmates who have not read the larger work.

Types of abstracts

There are two types of abstracts: descriptive and informative. They have different aims, so as a consequence they have different components and styles. There is also a third type called critical, but it is rarely used. If you want to find out more about writing a critique or a review of a work, see the UNC Writing Center handout on writing a literature review . If you are unsure which type of abstract you should write, ask your instructor (if the abstract is for a class) or read other abstracts in your field or in the journal where you are submitting your article.

Descriptive abstracts

A descriptive abstract indicates the type of information found in the work. It makes no judgments about the work, nor does it provide results or conclusions of the research. It does incorporate key words found in the text and may include the purpose, methods, and scope of the research. Essentially, the descriptive abstract describes the work being abstracted. Some people consider it an outline of the work, rather than a summary. Descriptive abstracts are usually very short—100 words or less.

Informative abstracts

The majority of abstracts are informative. While they still do not critique or evaluate a work, they do more than describe it. A good informative abstract acts as a surrogate for the work itself. That is, the writer presents and explains all the main arguments and the important results and evidence in the complete article/paper/book. An informative abstract includes the information that can be found in a descriptive abstract (purpose, methods, scope) but also includes the results and conclusions of the research and the recommendations of the author. The length varies according to discipline, but an informative abstract is rarely more than 10% of the length of the entire work. In the case of a longer work, it may be much less.

Here are examples of a descriptive and an informative abstract of this handout on abstracts . Descriptive abstract:

The two most common abstract types—descriptive and informative—are described and examples of each are provided.

Informative abstract:

Abstracts present the essential elements of a longer work in a short and powerful statement. The purpose of an abstract is to provide prospective readers the opportunity to judge the relevance of the longer work to their projects. Abstracts also include the key terms found in the longer work and the purpose and methods of the research. Authors abstract various longer works, including book proposals, dissertations, and online journal articles. There are two main types of abstracts: descriptive and informative. A descriptive abstract briefly describes the longer work, while an informative abstract presents all the main arguments and important results. This handout provides examples of various types of abstracts and instructions on how to construct one.

Which type should I use?

Your best bet in this case is to ask your instructor or refer to the instructions provided by the publisher. You can also make a guess based on the length allowed; i.e., 100-120 words = descriptive; 250+ words = informative.

How do I write an abstract?

The format of your abstract will depend on the work being abstracted. An abstract of a scientific research paper will contain elements not found in an abstract of a literature article, and vice versa. However, all abstracts share several mandatory components, and there are also some optional parts that you can decide to include or not. When preparing to draft your abstract, keep the following key process elements in mind:

- Reason for writing: What is the importance of the research? Why would a reader be interested in the larger work?

- Problem: What problem does this work attempt to solve? What is the scope of the project? What is the main argument/thesis/claim?

- Methodology: An abstract of a scientific work may include specific models or approaches used in the larger study. Other abstracts may describe the types of evidence used in the research.

- Results: Again, an abstract of a scientific work may include specific data that indicates the results of the project. Other abstracts may discuss the findings in a more general way.

- Implications: What changes should be implemented as a result of the findings of the work? How does this work add to the body of knowledge on the topic?

(This list of elements is adapted with permission from Philip Koopman, “How to Write an Abstract.” )

All abstracts include:

- A full citation of the source, preceding the abstract.

- The most important information first.

- The same type and style of language found in the original, including technical language.

- Key words and phrases that quickly identify the content and focus of the work.

- Clear, concise, and powerful language.

Abstracts may include:

- The thesis of the work, usually in the first sentence.

- Background information that places the work in the larger body of literature.

- The same chronological structure as the original work.

How not to write an abstract:

- Do not refer extensively to other works.

- Do not add information not contained in the original work.

- Do not define terms.

If you are abstracting your own writing

When abstracting your own work, it may be difficult to condense a piece of writing that you have agonized over for weeks (or months, or even years) into a 250-word statement. There are some tricks that you could use to make it easier, however.

Reverse outlining:

This technique is commonly used when you are having trouble organizing your own writing. The process involves writing down the main idea of each paragraph on a separate piece of paper– see our short video . For the purposes of writing an abstract, try grouping the main ideas of each section of the paper into a single sentence. Practice grouping ideas using webbing or color coding .

For a scientific paper, you may have sections titled Purpose, Methods, Results, and Discussion. Each one of these sections will be longer than one paragraph, but each is grouped around a central idea. Use reverse outlining to discover the central idea in each section and then distill these ideas into one statement.

Cut and paste:

To create a first draft of an abstract of your own work, you can read through the entire paper and cut and paste sentences that capture key passages. This technique is useful for social science research with findings that cannot be encapsulated by neat numbers or concrete results. A well-written humanities draft will have a clear and direct thesis statement and informative topic sentences for paragraphs or sections. Isolate these sentences in a separate document and work on revising them into a unified paragraph.

If you are abstracting someone else’s writing

When abstracting something you have not written, you cannot summarize key ideas just by cutting and pasting. Instead, you must determine what a prospective reader would want to know about the work. There are a few techniques that will help you in this process:

Identify key terms:

Search through the entire document for key terms that identify the purpose, scope, and methods of the work. Pay close attention to the Introduction (or Purpose) and the Conclusion (or Discussion). These sections should contain all the main ideas and key terms in the paper. When writing the abstract, be sure to incorporate the key terms.

Highlight key phrases and sentences:

Instead of cutting and pasting the actual words, try highlighting sentences or phrases that appear to be central to the work. Then, in a separate document, rewrite the sentences and phrases in your own words.

Don’t look back:

After reading the entire work, put it aside and write a paragraph about the work without referring to it. In the first draft, you may not remember all the key terms or the results, but you will remember what the main point of the work was. Remember not to include any information you did not get from the work being abstracted.

Revise, revise, revise

No matter what type of abstract you are writing, or whether you are abstracting your own work or someone else’s, the most important step in writing an abstract is to revise early and often. When revising, delete all extraneous words and incorporate meaningful and powerful words. The idea is to be as clear and complete as possible in the shortest possible amount of space. The Word Count feature of Microsoft Word can help you keep track of how long your abstract is and help you hit your target length.

Example 1: Humanities abstract

Kenneth Tait Andrews, “‘Freedom is a constant struggle’: The dynamics and consequences of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement, 1960-1984” Ph.D. State University of New York at Stony Brook, 1997 DAI-A 59/02, p. 620, Aug 1998

This dissertation examines the impacts of social movements through a multi-layered study of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement from its peak in the early 1960s through the early 1980s. By examining this historically important case, I clarify the process by which movements transform social structures and the constraints movements face when they try to do so. The time period studied includes the expansion of voting rights and gains in black political power, the desegregation of public schools and the emergence of white-flight academies, and the rise and fall of federal anti-poverty programs. I use two major research strategies: (1) a quantitative analysis of county-level data and (2) three case studies. Data have been collected from archives, interviews, newspapers, and published reports. This dissertation challenges the argument that movements are inconsequential. Some view federal agencies, courts, political parties, or economic elites as the agents driving institutional change, but typically these groups acted in response to the leverage brought to bear by the civil rights movement. The Mississippi movement attempted to forge independent structures for sustaining challenges to local inequities and injustices. By propelling change in an array of local institutions, movement infrastructures had an enduring legacy in Mississippi.

Now let’s break down this abstract into its component parts to see how the author has distilled his entire dissertation into a ~200 word abstract.

What the dissertation does This dissertation examines the impacts of social movements through a multi-layered study of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement from its peak in the early 1960s through the early 1980s. By examining this historically important case, I clarify the process by which movements transform social structures and the constraints movements face when they try to do so.

How the dissertation does it The time period studied in this dissertation includes the expansion of voting rights and gains in black political power, the desegregation of public schools and the emergence of white-flight academies, and the rise and fall of federal anti-poverty programs. I use two major research strategies: (1) a quantitative analysis of county-level data and (2) three case studies.

What materials are used Data have been collected from archives, interviews, newspapers, and published reports.

Conclusion This dissertation challenges the argument that movements are inconsequential. Some view federal agencies, courts, political parties, or economic elites as the agents driving institutional change, but typically these groups acted in response to movement demands and the leverage brought to bear by the civil rights movement. The Mississippi movement attempted to forge independent structures for sustaining challenges to local inequities and injustices. By propelling change in an array of local institutions, movement infrastructures had an enduring legacy in Mississippi.

Keywords social movements Civil Rights Movement Mississippi voting rights desegregation

Example 2: Science Abstract

Luis Lehner, “Gravitational radiation from black hole spacetimes” Ph.D. University of Pittsburgh, 1998 DAI-B 59/06, p. 2797, Dec 1998

The problem of detecting gravitational radiation is receiving considerable attention with the construction of new detectors in the United States, Europe, and Japan. The theoretical modeling of the wave forms that would be produced in particular systems will expedite the search for and analysis of detected signals. The characteristic formulation of GR is implemented to obtain an algorithm capable of evolving black holes in 3D asymptotically flat spacetimes. Using compactification techniques, future null infinity is included in the evolved region, which enables the unambiguous calculation of the radiation produced by some compact source. A module to calculate the waveforms is constructed and included in the evolution algorithm. This code is shown to be second-order convergent and to handle highly non-linear spacetimes. In particular, we have shown that the code can handle spacetimes whose radiation is equivalent to a galaxy converting its whole mass into gravitational radiation in one second. We further use the characteristic formulation to treat the region close to the singularity in black hole spacetimes. The code carefully excises a region surrounding the singularity and accurately evolves generic black hole spacetimes with apparently unlimited stability.

This science abstract covers much of the same ground as the humanities one, but it asks slightly different questions.

Why do this study The problem of detecting gravitational radiation is receiving considerable attention with the construction of new detectors in the United States, Europe, and Japan. The theoretical modeling of the wave forms that would be produced in particular systems will expedite the search and analysis of the detected signals.

What the study does The characteristic formulation of GR is implemented to obtain an algorithm capable of evolving black holes in 3D asymptotically flat spacetimes. Using compactification techniques, future null infinity is included in the evolved region, which enables the unambiguous calculation of the radiation produced by some compact source. A module to calculate the waveforms is constructed and included in the evolution algorithm.

Results This code is shown to be second-order convergent and to handle highly non-linear spacetimes. In particular, we have shown that the code can handle spacetimes whose radiation is equivalent to a galaxy converting its whole mass into gravitational radiation in one second. We further use the characteristic formulation to treat the region close to the singularity in black hole spacetimes. The code carefully excises a region surrounding the singularity and accurately evolves generic black hole spacetimes with apparently unlimited stability.

Keywords gravitational radiation (GR) spacetimes black holes

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Belcher, Wendy Laura. 2009. Writing Your Journal Article in Twelve Weeks: A Guide to Academic Publishing Success. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Press.

Koopman, Philip. 1997. “How to Write an Abstract.” Carnegie Mellon University. October 1997. http://users.ece.cmu.edu/~koopman/essays/abstract.html .

Lancaster, F.W. 2003. Indexing And Abstracting in Theory and Practice , 3rd ed. London: Facet Publishing.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 3. The Abstract

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

An abstract summarizes, usually in one paragraph of 300 words or less, the major aspects of the entire paper in a prescribed sequence that includes: 1) the overall purpose of the study and the research problem(s) you investigated; 2) the basic design of the study; 3) major findings or trends found as a result of your analysis; and, 4) a brief summary of your interpretations and conclusions.

Writing an Abstract. The Writing Center. Clarion University, 2009; Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper. The Writing Center, University of Wisconsin, Madison; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-first Century . Oxford, UK: Chandos Publishing, 2010;

Importance of a Good Abstract

Sometimes your professor will ask you to include an abstract, or general summary of your work, with your research paper. The abstract allows you to elaborate upon each major aspect of the paper and helps readers decide whether they want to read the rest of the paper. Therefore, enough key information [e.g., summary results, observations, trends, etc.] must be included to make the abstract useful to someone who may want to examine your work.

How do you know when you have enough information in your abstract? A simple rule-of-thumb is to imagine that you are another researcher doing a similar study. Then ask yourself: if your abstract was the only part of the paper you could access, would you be happy with the amount of information presented there? Does it tell the whole story about your study? If the answer is "no" then the abstract likely needs to be revised.

Farkas, David K. “A Scheme for Understanding and Writing Summaries.” Technical Communication 67 (August 2020): 45-60; How to Write a Research Abstract. Office of Undergraduate Research. University of Kentucky; Staiger, David L. “What Today’s Students Need to Know about Writing Abstracts.” International Journal of Business Communication January 3 (1966): 29-33; Swales, John M. and Christine B. Feak. Abstracts and the Writing of Abstracts . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2009.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types of Abstracts

To begin, you need to determine which type of abstract you should include with your paper. There are four general types.

Critical Abstract A critical abstract provides, in addition to describing main findings and information, a judgment or comment about the study’s validity, reliability, or completeness. The researcher evaluates the paper and often compares it with other works on the same subject. Critical abstracts are generally 400-500 words in length due to the additional interpretive commentary. These types of abstracts are used infrequently.

Descriptive Abstract A descriptive abstract indicates the type of information found in the work. It makes no judgments about the work, nor does it provide results or conclusions of the research. It does incorporate key words found in the text and may include the purpose, methods, and scope of the research. Essentially, the descriptive abstract only describes the work being summarized. Some researchers consider it an outline of the work, rather than a summary. Descriptive abstracts are usually very short, 100 words or less. Informative Abstract The majority of abstracts are informative. While they still do not critique or evaluate a work, they do more than describe it. A good informative abstract acts as a surrogate for the work itself. That is, the researcher presents and explains all the main arguments and the important results and evidence in the paper. An informative abstract includes the information that can be found in a descriptive abstract [purpose, methods, scope] but it also includes the results and conclusions of the research and the recommendations of the author. The length varies according to discipline, but an informative abstract is usually no more than 300 words in length.

Highlight Abstract A highlight abstract is specifically written to attract the reader’s attention to the study. No pretense is made of there being either a balanced or complete picture of the paper and, in fact, incomplete and leading remarks may be used to spark the reader’s interest. In that a highlight abstract cannot stand independent of its associated article, it is not a true abstract and, therefore, rarely used in academic writing.

II. Writing Style

Use the active voice when possible , but note that much of your abstract may require passive sentence constructions. Regardless, write your abstract using concise, but complete, sentences. Get to the point quickly and always use the past tense because you are reporting on a study that has been completed.

Abstracts should be formatted as a single paragraph in a block format and with no paragraph indentations. In most cases, the abstract page immediately follows the title page. Do not number the page. Rules set forth in writing manual vary but, in general, you should center the word "Abstract" at the top of the page with double spacing between the heading and the abstract. The final sentences of an abstract concisely summarize your study’s conclusions, implications, or applications to practice and, if appropriate, can be followed by a statement about the need for additional research revealed from the findings.

Composing Your Abstract

Although it is the first section of your paper, the abstract should be written last since it will summarize the contents of your entire paper. A good strategy to begin composing your abstract is to take whole sentences or key phrases from each section of the paper and put them in a sequence that summarizes the contents. Then revise or add connecting phrases or words to make the narrative flow clearly and smoothly. Note that statistical findings should be reported parenthetically [i.e., written in parentheses].

Before handing in your final paper, check to make sure that the information in the abstract completely agrees with what you have written in the paper. Think of the abstract as a sequential set of complete sentences describing the most crucial information using the fewest necessary words. The abstract SHOULD NOT contain:

- A catchy introductory phrase, provocative quote, or other device to grab the reader's attention,

- Lengthy background or contextual information,

- Redundant phrases, unnecessary adverbs and adjectives, and repetitive information;

- Acronyms or abbreviations,

- References to other literature [say something like, "current research shows that..." or "studies have indicated..."],

- Using ellipticals [i.e., ending with "..."] or incomplete sentences,

- Jargon or terms that may be confusing to the reader,

- Citations to other works, and

- Any sort of image, illustration, figure, or table, or references to them.

Abstract. Writing Center. University of Kansas; Abstract. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Abstracts. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Borko, Harold and Seymour Chatman. "Criteria for Acceptable Abstracts: A Survey of Abstracters' Instructions." American Documentation 14 (April 1963): 149-160; Abstracts. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Hartley, James and Lucy Betts. "Common Weaknesses in Traditional Abstracts in the Social Sciences." Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 60 (October 2009): 2010-2018; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-first Century. Oxford, UK: Chandos Publishing, 2010; Procter, Margaret. The Abstract. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Riordan, Laura. “Mastering the Art of Abstracts.” The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 115 (January 2015 ): 41-47; Writing Report Abstracts. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing Abstracts. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-First Century . Oxford, UK: 2010; Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper. The Writing Center, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Writing Tip

Never Cite Just the Abstract!

Citing to just a journal article's abstract does not confirm for the reader that you have conducted a thorough or reliable review of the literature. If the full-text is not available, go to the USC Libraries main page and enter the title of the article [NOT the title of the journal]. If the Libraries have a subscription to the journal, the article should appear with a link to the full-text or to the journal publisher page where you can get the article. If the article does not appear, try searching Google Scholar using the link on the USC Libraries main page. If you still can't find the article after doing this, contact a librarian or you can request it from our free i nterlibrary loan and document delivery service .