Current SWHPN Members: We have switched platforms. Your old login will no longer work. Contact [email protected] to access your account.

We're on a mission to revolutionize hospice and palliative care by making it a more equitable experience for everyone involved, including the clinicians at its heart.

If you're a healthcare provider committed to dismantling structures of oppression and crave the support you need for a fulfilling career instead of a draining one, you’re in the right place.

About SWHPN

We offer membership, small group support and continuing education for hospice + palliative care social workers and clinicians making an impact.

Our mission is to enhance hospice and palliative care social work through mentorship, education, community building and advocacy as change agents committed to equity and anti-racism. We start with ourselves to dismantle harms perpetuated within the systems in which we exist.

Join us in defining the future of compassionate, whole-person healthcare — and get the support you need for a sustainable career while you're at it.

Membership Options

Becoming a SWHPN member offers you access to the sweetest + boldest community you've ever met, support for a sustainable career, resources valued at over $1000 per year and more.

Learn With Us

At least once a month we offer continuing education programming that covers the topics that really matter, such as cultivating cultural responsiveness in your practice and how to take care of yourself in ways that actually work.

Support Our Work

Your tax deductible donation fuels the development of anti-oppression curriculum, supports advocacy efforts for healthcare equity, provides genuine assistance to hospice + palliative care clinicians and offers valuable resources to those in need.

What we offer

MENTORSHIP PROGRAM

Applications for our 2024-2025 Mentor-Mentee Cohort are now closed

As a benefit of SWHPN membership, we pair mentors + mentees together for a year long relationship to enhance professional practice.

Thank you to all who applied!

We will be accepting 10 pairs for the 2024-2025 cohort which will run from June 2024 through the SWHPN Annual Conference in 2025.

If you submitted an application you can expect an email with an update by the end of May.

.jpg)

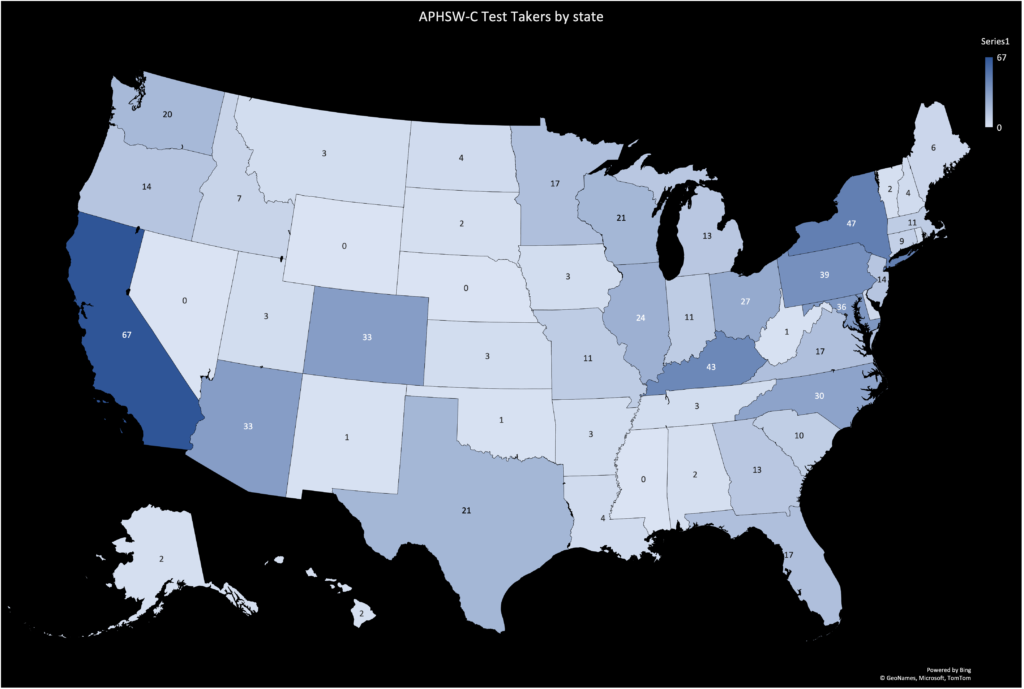

The only evidence based certification for hospice + palliative care workers

Social workers are essential to the practice of hospice and palliative care. The APHSW-C certification recognizes bachelor’s and master’s level social workers with experience, specialized skills and competency in hospice and palliative social work. The APHSW-C assures the public that certified practitioners have the knowledge and skills to provide safe, high-quality care at an advanced level and we have the resources you need to prepare for your exam.

TESTIMONIALS

What people are saying

Alisha McGuire

I joined SWHPN when I transitioned into the world of palliative (and hospice) social work. I have gotten so much out of my membership; ranging from education, professional/career development, mentorship, and lifelong friendships. SWHPN has helped be the platform in the "next steps" of my career from the micro to the macro!

Arika Patneaude

I joined SWHPN because I wanted to be in community with other HAPC social workers and interprofessional colleagues. I remain a SWHPN member because I want to make an impact on HAPC as a field in engaging in and committing to anti-oppression and anti-racist end-of-life care with colleagues and an organization that are committed to this as a mission. As HAPC professionals we cannot provide high quality serious illness care from diagnosis to death without being culturally responsive and anti-racist.

Jennifer Hill Buehrer

Social work in the medical field is lonely - palliative care social work even more so! I love the chance to connect with other professionals who understand that, and who do the same really difficult, emotionally challenging work I do.

STAY IN THE LOOP

Sign up for our newsletter

You Can Also Sign Up For Our Friday Weekly News Brief Here

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Institute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council (US) National Cancer Policy Board; Foley KM, Gelband H, editors. Improving Palliative Care for Cancer. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001.

Improving Palliative Care for Cancer.

- Hardcopy Version at National Academies Press

9 Professional Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Physicians, Nurses, and Social Workers

Hellen Gelband

Institute of Medicine

- INTRODUCTION

In 1997, the Institute of Medicine (IOM, 1997) described a system of professional end-of-life care whose major deficiencies included

- a curriculum in which death is conspicuous mainly by its relative absence;

- educational materials that are notable for their inattention to the end stages of most diseases and their neglect of palliative strategies; and

- clinical experiences for students and residents that largely ignore dying patients and those close to them.

However, it also reported “increasing acknowledgement by practitioners and educators of the compelling need to better prepare clinicians to assess and manage symptoms, to communicate with patients and families, and to participate in interdisciplinary caregiving that meets the varied needs of dying patients and those close to them.” The increasing interest had already translated into new programs by professional societies, medical schools, and private foundations, and these continue. However, impressive as the initiatives are, they are small in scale compared with national needs. The IOM report cautioned that “persistence in their implementation, evaluation, redesign, and extension will be necessary to keep the promise from fading once initial enthusiasm subsides,” and this caution remains appropriate in 2001. This chapter takes as a starting point one of the 1997 report's major recommendations:

Educators and other health professionals should initiate changes in undergraduate, graduate, and continuing education to ensure that practitioners have relevant attitudes, knowledge, and skills to care well for dying patients.

Within medicine, nursing, and social work, the recognition of deficiencies in education are well known, and each profession has at least initiated efforts to improve the status quo. However, the recognition that improvements are needed does not bring the knowledge and tools necessary to accomplish those ends. This is the task that lies ahead and that will require persistent effort and increased and sustained funding for a wide range of activities. Thus far, funding for the major initiatives have been led by private foundations. With successful programs started and ideas for new approaches proliferating however, the amount of funding that can be put to productive use is much greater. Sustained progress at this juncture requires a substantial commitment of support from the public sector as well as continued support for innovation from the private sector.

- PHYSICIAN EDUCATION IN END-OF-LIFE CARE

Most U.S. physicians—oncologists, other specialists, and generalists alike—are not prepared by education or experience to satisfy the palliative care needs of dying cancer patients or even to help them get needed services from other providers. With half a million people dying from cancer each year in this country, this is a stark, but robust finding. The strongest sources of supporting evidence are

- studies during the late 1990s documenting end-of-life and palliative care content in undergraduate and residency coursework, and

- studies during the late 1990s of medical textbook content on end-of-life and palliative care.

Consistent with these sources are responses given by oncologists to American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 1998 survey questions about their training in end-of-life and palliative care and their abilities to provide appropriate care of this type (Emanuel, 2000). The evidence is consistent with a lack of funding for end-of-life and palliative care educational initiatives, which has begun to change only recently. Even in 2001, however, the programs are small and funded largely by private grant-making organizations, with little contribution by the federal government. Perhaps even more persuasive is the complete lack of documented disagreement about the poor state of end-of-life medical education.

End-of-Life Care Education During Medical School and Residency Programs

The subject of “death and dying” first entered the medical school curriculum in the 1960s, as a topic of discussion in preclinical coursework. Movement toward integrating end-of-life and palliative care into the clinical curriculum has begun much more recently. In 1999, the Medical School Objectives Project identified “knowledge…of the major ethical dilemmas in medicine, particularly those that arise at the beginning and end of life…” and “knowledge about relieving pain and ameliorating the suffering of patients” as subjects that should be mastered by all undergraduate medical students (Medical School Objectives Writing Group, 1999).

Students in some programs may get the training and opportunities needed, but according to the most recent and most complete survey of medical school and residency end-of-life and palliative care curricula, most do not. Barzansky and colleagues (1999) used three annual surveys that collectively cover all medical school and residency programs to analyze end-of-life and palliative care content. Results for undergraduate medical education and residency programs are summarized separately.

Undergraduate Medical Education

Two surveys provide information on medical school curricula: the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) Annual Medical School Questionnaires for years 1997–1998 and 1998–1999, and the 1998 Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Graduation Questionnaire. The LCME survey goes to the deans of all 125 LCME-accredited medical schools each year, and in the two years described here, all deans responded. The AAMC questionnaire went to all 14,040 students graduating from the 125 medical schools, of whom 88 percent responded.

The LCME survey asked different questions about end-of-life and palliative care in each of the two years. In 1997–1998, the question was whether selected topics related to end-of-life care were included in the curriculum as courses that were required, parts of required courses, electives, or a combination of these. In the second year, schools were asked (1) whether certain topics related to the care of terminally ill patients were covered in required lectures or conferences and (2) whether students spent time during required courses or clerkships in clinical units devoted to care of terminally ill patients. The 1998 AAMC survey asked students to rate the level of time devoted to end-of-life issues (among others) as either inadequate, appropriate, or excessive.

LCME S URVEYS At all schools, students have some exposure to end-of-life coursework, but it is overwhelmingly in broader courses, not in required courses on end-of-life topics ( Table 9-1 ). More than half the schools do not offer even one elective course devoted to end-of-life issues. The survey provides no information on how much time was spent on relevant topics or how they were covered but does suggest that there are substantial gaps. For instance, 30 percent of the schools appear to have no required instruction on at least one of the three topics asked about in 1997–1998. The 1998– 1999 survey also asked about direct experience with patients in hospice care (or other settings in which the focus was on end-of-life or palliative care) ( Table 9-2 ). At 20 percent of the schools, such experience was required, and at another 20 percent, it was not available at all. No information was gathered on the percentage of students who took advantage of the elective opportunity offered in the remaining three-fifths of the schools.

LCME Annual Medical School Questionnaire—Course Content (125 Schools=100%).

LCME Annual Medical School Questionnaire: Experience in Hospice or Other End-of-Life Care Setting, 1998–1999 Survey (125 Schools=100%).

AAMC M EDICAL S CHOOL G RADUATION Q UESTIONNAIRE The AAMC annual survey asks graduating medical students to rate the adequacy of instruction in various areas. In 1998, they were asked about death and dying, and pain management ( Table 9-3 ). The responses are subjective, but again, they suggest strongly that students are not prepared to care for dying patients as well as they could be during their undergraduate medical education.

AAMC Medical School Graduation Questionnaire: Level of Coverage of Death and Dying and Pain Management 1998 Survey (N= 13,861 responses out of 14,040 eligible).

Residency Programs

The 1997–1998 American Medical Association (AMA) Annual Survey of Graduate Medical Education was sent to 7,861 residency programs (all of those accredited by the Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education), of which 96.5 percent responded. The survey asked whether each program had a structured curriculum in end-of-life care. (No more specific definitions of what might be included in an end-of-life curriculum were provided, so the term may have been interpreted differently by different respondents.)

Overall, 60 percent of programs reported that they did have a structured curriculum, but there was tremendous variability among programs in different specialties. Of the types of physicians most likely to care for dying patients

- 92 percent of programs in family practice and internal medicine and 98 percent in critical care medicine reported positively, and

- between 60 percent and 70 percent of programs in obstetrics-gynecology, pediatrics, psychiatry, and surgery reported positively.

The results of these recent surveys suggest that undergraduate medical and residency training lacks adequate content in end-of-life care, but without much detail. One would like to know what topics are covered in end-of-life education, the format (i.e., lectures, discussions, clinical experience), how much time is devoted to each subject, and how well students are prepared by the extent and types of training they receive. This information has not been assembled in a comprehensive way, but pieces of it are explored in the recent literature in different ways. A wide-ranging review of published literature and grant proposals for end-of-life care by Billings and Block (1997) has brought together the relevant material.

Billings and Block (1997) searched the published literature for articles on palliative care and related topics for the years 1980 through 1995 and reviewed palliative care education grants funded by the National Cancer Institute or submitted for funding to the Project on Death in America. One hundred eighty articles—culled from more than 9,000 potentially relevant citations—form the basis of their analysis. Their findings, which complement and support the findings of the recent surveys discussed earlier, are summarized here.

C URRICULUM IN E ND - OF -L IFE C ARE Some of the literature reviewed by Billings and Block (1997) represented reports of the surveys of medical school deans in years earlier than those characterized by Barzansky and colleagues (1999). The following findings were reported from the 1989 survey of medical school deans, which at the time numbered 124, of whom 111 responded (Mermann et al., 1991).

Twelve of the schools had no curriculum at all in death and dying. In 30 schools, one or two lectures on death and dying were included in other courses. In 51 schools, it was taught as a distinct module in a required course, consisting of four to six lectures or a combined lecture and seminar series with small-group discussion. Eighteen schools offered a separate course on death and dying, which was required in the first two years by nearly half of the schools. The format varied from a one-weekend workshop to semester-long lecture and seminar classes, with the lecture format predominating (15 schools). There was very little contact with dying patients in any program.

The class presidents of all U.S. medical schools were polled in 1991 about terminal care education (Holleman et al., 1994). Among the findings highlighted by Billings and Block are

- more than one-quarter reported one hour or less of class time,

- 39 percent recalled some reading on the topic, and

- 37 percent rated the quality of teaching “ineffective” and 3 percent rated it “very effective.”

In contrast to the students' evaluations, a national sample of cancer center directors and directors of nursing oncology reported high levels of satisfaction with supportive care instruction (greater than 90 percent) (Belani et al., 1994). However, in the one institution where students were actually studied, the level of satisfaction was 27 percent.

R ELATED F INDINGS When Billings and Block reviewed the literature in the mid-1990s, they found a number of small, more detailed studies, all of which lend support to the need for more attention to end-of-life care. Their findings span research published from 1980 through 1995; thus, some findings may be less relevant in 2001 than when published, but the pace of change has not been so great that this is necessarily so. Following are some provocative observations from individual studies:

- 30 percent of a random sample of generalists in Oregon recalled medical school training in dealing with dying patients, and 87 percent thought that more such instruction should be given in medical school;

- 39 percent of a sample of young physicians felt they had good or excellent preparation for managing the care of patients who want to die;

- 41 percent of students completing third-year clerkships were never present when an attending physician talked with a dying person, 35 percent had never discussed with an attending physician how to deal with terminally ill patients, 73 percent had never been present when a surgeon told a family about bad news after an operation, and one-third could not identify problems that would arise for family members when a dying patient was discharged to go home.

Articles on end-of-life care during residency reviewed by Billings and Block (1997) are consistent with the more recent survey findings. A similar survey of 1,068 accredited residency programs in family medicine, internal medicine, pediatrics, and geriatrics, published in 1995 (Hill, 1995) found that

- 26 percent of all residency programs in the United States offer a standard course in end-of-life care,

- almost 15 percent of programs offer no formal training in care of terminally ill patients, and

- 8 percent require a hospice rotation and 9 percent offer an elective one.

More than 1,400 residents in 55 internal medicine residency programs were surveyed by the American Board of Internal Medicine about the adequacy of their training in end-of-life care (reported in Foley, 1997). The percentage of residents reporting “adequate training” in specific areas was

- 72 percent, managing pain and other symptoms;

- 62 percent, telling patients that they are dying;

- 38 percent, describing what the dying process will be like; and

- 32 percent, talking to patients who request assistance in dying.

Conclusions

Most new physicians leave medical school and residency programs with little training or experience in caring for dying patients. In most cases, a few lectures are folded into other courses (in many cases in psychiatry and behavioral sciences, ethics, or the humanities). A few schools offer full-length courses on end-of-life care, but they are nearly all electives. According to the limited information available, most end-of-life training is provided in lectures only. Contact with dying patients, particularly for undergraduate medical students, if any, is limited.

Formal curriculum in end-of-life care is presented predominantly in preclinical years. In clinical training, which tends to be more informal and less systematic, teachers may have no special interest or expertise in end-of-life care. The importance of role models and mentors who are enthusiastic about caring for dying patients has largely been overlooked. There is a tremendous opportunity to train the next generation of physicians in the care of dying patients. At the same time, opportunities must be created to improve the competence of physicians who are already practicing, but who have had inadequate preparation in end-of-life care.

End-of-Life Care in Medical Textbooks

Textbooks play an important role both in educating medical students and in informing practicing physicians of the standard of care for each disease covered. The topics included in textbooks and the way information is organized may be strong influences on the practice of medicine. In the past few years, researchers have looked systematically at the information relating to end-of-life issues that is contained in a variety of medical textbooks. Two landmark studies, one of general medical texts and the other of medical specialty texts, which are the most recent and comprehensive, are presented here (a similar analysis of nursing texts is discussed later in this chapter). Both studies included specific cancers in their analyses.

End-of-Life Content in Four General Medical Textbooks

The study of general medical textbooks (Carron et al., 1999) focused on four widely used books: Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine (Isselbacher et al., 1994), the Merck Manual (Berkow, 1992), Scientific American Medicine on CD-ROM (SAM-CD, 1994), and Manual of Medical Therapeutics (Ewald and McKenzie, 1995; also known as the Washington Manual ). In addition, the authors reviewed (although not in the same quantitative format as the target texts) William Osler's (1899) Principles and Practice of Medicine, and the Mayo Clinic Family Health Book (Larson, 1996) a medical reference for nonprofessionals.

Information was sought from each book on 12 of the leading causes of death in the United States, and for each disease, nine “content domains” were assessed ( Table 9-4 ). In addition to displaying the content score for each domain by disease, a rough overall score was calculated for each book by assigning a value of 1 for each “+” rating and 2 for each “++” rating and dividing the total by the total possible score (i.e., a rating of ++ in each category).

End-of-Life Care in General Medical Textbooks.

The following are some general findings (Carron et al., 1999):

- Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine, the Merck Manual, and Scientific American Medicine characterized medical interventions and prognostic factors but often did not mention decisionmaking or the effect of death and dying on the patient's family.

- The Washington Manual “offered almost no helpful information.”

- Dementia, AIDS, lung cancer, and breast cancer received the most comprehensive coverage of issues related to dying. However, “the best coverage…was scored as presenting useful information in only five of the nine domains.”

Overall scores ranged from 11 percent for The Washington Manual to 38 percent for Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine.

In contrast to the lack of coverage in medical textbooks, the Mayo Clinic Family Health Book contains a chapter on death and dying with a comprehensive discussion of “pain control in a terminal patient, the emotions of a dying patient, hospice care, funeral arrangements, when and how to tell the patient about a terminal diagnosis, and what the family should expect” (Carron et al., 1999).

Osler's 1899 textbook was found to be more straightforward about the fact of death but generally not about how to help patients cope with dying. One exception is Osler's admonition to use opiates for patients dying of hemorrhage into the lungs, to suppress terror and dyspnea. This information did not appear in any other text.

End-of-Life Content in 50 Medical Specialty Textbooks

The end-of-life content of 50 top-selling textbooks in a variety of specialties ( Table 9-5 ) was the subject of the second major review (Rabow et al., 2000). The methodology followed closely the methods used by Carron and colleagues in their study of general medical textbooks, but the content domains were expanded and the medical conditions studied necessarily varied from book to book and were chosen to represent the common causes of death in each specialty. The authors also reviewed the tables of contents for chapters dealing specifically with end-of-life care and searched the indexes for 18 relevant key words. In scoring, rather than calculating an overall score for each book (as Carron and colleagues did), the results are presented as the percentage of instances of “absent,” “minimal,” and “helpful” information.

End-of-Life Care Content of 50 Textbooks: Specialties, Content Domains, Scoring.

When the overall scores for each specialty were calculated (the average of the individual textbook scores in each specialty), there were some differences among specialties but a generalized pattern of 50–70 percent absent content and lower scores (i.e., poorer ratings) for minimal or helpful content (see Rabow et al., 2000, figure 1). Although the differences were not large, the authors noted that textbooks with the least end-of-life content were in the specialties of infectious diseases and AIDS, oncology and hematology, and surgery.

Information on how each domain was covered was presented for the six internal medicine textbooks. The 14 conditions analyzed in these texts included three cancers (breast, colon, and lung). The best-covered domains were epidemiology and natural history (i.e., consistent ratings of 2), and the worst were social, spiritual, and family issues; ethics, and physician responsibilities. In the remaining domains, minimal information (a rating of 1) was most common.

Ten conditions were appropriate to more than one specialty, and these included two cancers: lung cancer and leukemia. Lung cancer was covered in family and primary care medicine, internal medicine, and oncology-hematology; leukemia in family and primary care medicine and pediatrics, in addition to oncology-hematology. For lung cancer, oncology-hematology had the lowest helpful score (11.6 percent), followed by internal medicine (20.5 percent), and family and primary care had the best helpful score (28.2 percent). For leukemia, pediatrics and oncology-hematology helpful scores were similar (21.2 percent and 20.5 percent, respectively), and the lowest score was in family and primary care medicine (10.3 percent).

The analysis of key end-of-life index words showed an overall paucity of references, consistent with the content domain analyses.

Comment on Textbook Studies

A physician consulting a textbook on the treatment of a potentially fatal condition is most likely to find no specific information that will help care for the patient who does, indeed, die. In a minority of cases, useful information may be found. In both studies (Carron et al., 1999; Rabow et al., 2000), the scoring was generous, erring on the side of giving higher rather than lower scores, so even these scores may overestimate the useful content. The investigators also did not rate how useful or complete the information was. However, Carron and colleagues found that more often than not, when information about prognostic factors and disease progression was present, it was vague and would not be helpful in caring for a patient (e.g., the admonition that “supportive care is all that can be offered at this point”).

Knowing that many physicians have little experience with dying and little training to help them, Carron and colleagues commented that “standard reference textbooks should provide at least the essentials of good practice.” Yet, in fact, physicians cannot rely on these texts for much-needed information: on advance care planning, decisionmaking, the effect of death and dying on a patient's family, or symptom management. Most texts do not describe the way that people with a disease generally die.

The findings from these textbook reviews are so stark that they cannot, and in fact have not, been ignored. Partly in response to these studies, some textbook publishers have commissioned updates for particular chapters. In addition, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation has begun a Textbook Revisions Project with the goal of working with publishers and editors to ensure that end-of-life chapters are added to textbooks and that end-of-life information is added to other chapters as appropriate (Gibson, 2000).

The 1998 ASCO Survey

In 1998, American Society of Clinical Oncology conducted the first and only large-scale survey of U.S. oncologists about their experiences in providing care to dying patients. The questionnaire consisted of 118 questions about end-of-life care under eight headings, one of which was education and training (Hilden et al., 2001). All U.S. oncologists who reported that they managed patients at the end of life, and were ASCO members, were eligible for the survey, a total of 6,645 (the small number of ASCO members from England and Canada was also included). About 40 percent (2,645) responded (see table below) (Emanuel, 2000). No information is available to compare the characteristics of those who responded with those who did not.

This survey documented serious shortcomings in the training and current practices of a large proportion of oncologists who responded. Among the key findings are the following:

- Most oncologists have not had adequate formal training in the key skills needed for them to provide excellent palliative and end-of-life care. Less than one-third reported their formal training “very helpful” in communicating with dying patients, coordinating their care, shifting to palliative care, or beginning hospice care. About 40 percent found their training very helpful in managing dying patients' symptoms.

- Slightly more than half (56 percent) reported “trial and error in clinical practice” as one important source of learning about end-of-life care. About 45 percent also ranked role models during fellowships and in practice as important. Traumatic patient experiences ranked higher as a source of learning than did lectures during fellowship, medical school role models, and clinical clerkships.

Recommendations to Improve End-of-Life Medical Education

In 1997, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the Project on Death in America brought together 94 academic leaders (selected through a structured nomination process) in a national consensus conference on medical education for end-of-life care (Barnard et al., 1999). Their task was to develop recommendations to guide teaching in end-of-life care, based on evidence from the literature and expert opinion. The work was carried out by eight working groups in the following areas:

Preclinical years

Primary care and ambulatory care

Acute care hospitals

Emergency medicine

Intensive care

Long-term institutional care

Home care and hospice care

Each working group addressed five questions:

How do death and dying manifest themselves in your setting?

What are the tasks of end-of-life care in your setting?

What are the major opportunities and barriers to learning about end-of-life care?

What can be done to improve teaching about end-of-life care in your setting?

What currently available and new resources are needed to facilitate change?

A set of guiding principles for undergraduate medical education provides a framework for the recommendations of all the working groups (Billings and Block, 1997). The recommendations at the end of this chapter address how these principles might be advanced. This report does not make recommendations about the precise content of educational materials or programs, but the general skills and knowledge required are summarized well in the IOM report, Approaching Death (IOM, 1997).

Basic Principles for Enhancing Undergraduate Medical Education in Palliative Care 1

The care of dying persons and their families is a core professional task of physicians. Medical schools have a responsibility to prepare students to provide skilled, compassionate end-of-life care.

The following key content areas related to end-of-life care must be appropriately addressed in undergraduate medical education (NOTE: this list will differ depending on the setting and to some extent, patient population, e.g., children vs. adults.)

Medical education should encourage students to develop positive feelings about dying patients and their families and about the role of the physician in terminal care.

Enhanced teaching about death, dying, and bereavement should occur throughout the span of medical education.

Educational content and process should be tailored to students' developmental stage.

The best learning grows out of direct experiences with patients and families, particularly when students have an opportunity to follow patients longitudinally and develop a sense of intimacy and manageable personal responsibility for suffering persons.

Teaching and learning about death, dying, and bereavement should emphasize humanistic attitudes.

Teaching should address communication skills.

Students need to see physicians offering excellent medical care to dying people and their families, and finding meaning in their work.

Medical education should foster respect for patients' personal values and an appreciation of cultural and spiritual diversity in approaching death and dying.

The teaching process itself should mirror the values to which physicians aspire in working with patients.

A comprehensive, integrated understanding of and approach to death, dying, and bereavement is enhanced when students are exposed to the perspectives of multiple disciplines working together.

Faculty should be taught how to teach about end-of-life care, including how to be mentors and to model ideal behaviors and skills.

Student competence in managing prototypical clinical settings related to death, dying, and bereavement should be evaluated.

Educational programs should be evaluated using state-of-the-art methods.

Additional resources will be required to implement these changes.

Programs and Activities Needed to Advance End-of-Life Medical Education 2

Faculty development.

Few medical faculty, at either the undergraduate or the graduate level, are knowledgeable and enthusiastic about end-of-life care and therefore are not likely to be effective teachers. To compound this, there is little end-of-life care included in the grand rounds, teaching conferences, or journal clubs of traditional continuing medical education (CME) programs.

The end-of-life skills of interns and residents, who often act as role models for medical students in hospitals, may be lacking and should also be enhanced through special programs for house staff (Weissman et al., 1999).

More intense faculty development programs should be offered to improve communication, mentoring, and other teaching skills. Educators need ready access to end-of-life educational resource materials (e.g., handouts, pocket guides).

Improved Educational Materials

New materials have to be created and existing materials improved for training new and practicing physicians. This includes adding end-of-life content to medical textbooks, producing pocket guides and other references for interns and residents, and developing continuing education materials for practicing physicians.

Coordination of Medical Schools and Teaching Hospitals

Medical education takes place in a number of settings throughout the schooling process. Each medical school should develop a plan for teaching end-of-life care. This could be overseen by a committee with responsibility to review content across the entire curriculum, including preclinical and all phases of clinical education in outpatient, acute care hospital, long-term care, and home and hospice settings.

Coordination should also emphasize the need for interdisciplinary teamwork in caring for dying patients. Students should experience working together with physicians of different specialties, nurses, social workers, psychologists, other mental health workers, and clergy. They should also be instructed in caring for, and have opportunities to interact with, dying patients and their families (Weissman et al., 1999).

Residency Program Guidelines

The residency review committees that establish guidelines for clinical training have generally not mandated the inclusion of end-of-life and palliative care instruction. Perhaps presaging change, however, the internal medicine residency review committee has revised its guidelines to require instruction in palliative care and recommend clinical experience in hospice and home care.

Evaluation of Clinical Competence in End-of-Life and Palliative Care

Competence in these areas should be tested in the same way as for other clinical topics. Structured clinical examinations should be designed to assess the relevant skills in clinical care, decisionmaking, reasoning, and ethical problem solving.

In the hospital setting, communication and clinical decisionmaking skills can be observed by attending physicians or residents and they can give immediate feedback to students. Students' attitudes can be assessed by consulting hospital staff, patients, and family members, and medical charts can be reviewed to evaluate clinical practice (Weissman et al., 1999).

Licensing and Certifying Examinations

Both undergraduate licensing and graduate certification examinations have begun to include more questions on end-of-life care, but the content is still minimal. More questions on these exams will likely promote appropriate additions to the curriculum.

Improving the Research Base for Palliative Care Education

In addition to the many unanswered clinical questions surrounding end-of-life care, there is research to be done that could directly benefit the education process. The “epidemiology of dying” would describe where, how, and under whose care patients die in different settings, including the interactions of physicians, nurses, social workers, clergy, family, and other caregivers. Information about the effect on physicians (and others) of caring for dying patients could also help guide medical education.

The transition period of “prognostic uncertainty,” when choices must be made in the face of an uncertain outcome, is relatively unstudied in terms of the choices for patients and physicians.

Activities of Professional Organizations

Medical societies of various kinds, as well as societies of medical educators, can take a leadership role in placing end-of-life care prominently on the educational agenda. They can assess the educational needs of their members, develop clinical practice guidelines, encourage research, highlight end-of-life care at annual and other meetings, and undertake other activities (Weissman et al., 1999).

Standard-setting organizations, such as the Joint Commission on the Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) can promote more comprehensive end-of-life care requirements for hospitals, nursing homes, and other institutions. They also can help to educate medical administrators about quality end-of-life care (Weissman et al., 1999).

Recent and Ongoing End-of-Life Medical Education Project: Funding and Aims

Work on many of the identified needs has been started, mainly through foundation grants. These projects have succeeded in raising awareness of the need for improvement and stimulating innovative ideas. The major projects and funding sources are characterized in Table 9-6 . The National Cancer Institute also funded a group of grants through a one-time initiative but has no ongoing program for soliciting proposals in this area.

Recent and Ongoing End-of-Life Medical Education Projects.

- NURSING EDUCATION IN END-OF-LIFE CARE

Nurses are expected to provide physical, emotional, spiritual, and practical care for patients in every phase of life. They spend more time with patients near the end of life than do any other health professionals. Yet, like physicians, most nurses in the United States do not receive the training and practical experience they need to carry out these duties in the best fashion. The nursing curriculum has been less studied than the medical curriculum, but this has been changing, particularly in response to debates about assisted suicide and euthanasia (Ferrell et al., 2000).

The 1997 Institute of Medicine report (IOM, 1997) reviewed studies of the nursing curriculum and found that coursework varied greatly from school to school. Nurses were found to have had little supervised clinical experience with dying patients and had been given minimal guidance on handling their personal reactions and involvement with dying patients. Criticisms were also raised that the end-of-life curriculum is out of date and not based on current models of death education.

End-of-Life Nursing Curriculum and Nurses' Preparedness for End-of-Life Care

Analytical studies of the U.S. nursing curriculum for end-of-life content have not yet been done, but a recent survey of nursing faculty and members of state nursing boards about their perceptions of this content provides a useful starting point (Ferrell et al., 1999). The survey is part of a larger project (funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation) in which the three main nursing education associations are taking part, and the members of these three organizations were surveyed: the National Council of State Boards of Nursing, Inc.; the American Association of Colleges of Nursing; and the National League for Nursing Accreditation Commission.

Of the 725 respondents (the number surveyed was not reported), one-third were deans or chairpersons of schools of nursing, just over half were faculty members, and four percent were consultants or staff of state nursing boards (the rest had various roles). The key finding was that the adequacy of end-of-life content in these schools was rated at 6–7 on a scale of 0 (not adequate) to 10 (very adequate). This held for each of 10 specific content areas (e.g., death and dying, pain management, ethical issues).

The survey respondents also called for resources to help faculty improve end-of-life content in the form of

- Case studies

- Access to clinical sites

- Internet resources

- Audiovisuals

- Access to speakers, experts

- Lecture guides or outlines on end-of-life topics

- Computer-assisted instruction

- Standardized curriculum

As part of the same overall project, a sample of nurses completed a survey on a number of end-of-life topics, including their assessment of the effectiveness of nursing education in this area. The nurses surveyed included volunteers (300 who mailed in the survey, which was published in two general nursing journals) and 2,033 oncology nurses solicited directly (out of 5,000 who were mailed the survey), so the results should be considered descriptive only. They were asked about nine aspects of nursing education:

pain management,

overall content,

role and needs of family caregivers,

other symptom management,

grief and bereavement,

understanding the goals of palliative care,

ethical issues,

care of patients at time of death, and

communication with patients and families.

Less than 13 percent of those responding rated their education in all nine aspects as adequate. Most frequently rated as not adequate were pain management (71 percent), overall content (62 percent), and roles and needs of family caregivers (61 percent), but more than half reported “not adequate” education in each of the nine areas.

Most other relevant studies have focused on nurses' knowledge in the area of cancer pain management and palliative care, and these have found major deficiencies, most likely resulting from deficiencies in training (see, e.g., Ferrell and McCaffery, 1997; McCaffery and Ferrell, 1995).

End-of-Life Care in Nursing Textbooks

A major review of nursing textbooks for end-of-life content was completed recently (Ferrell et al., 1999b). Fifty current nursing textbooks, both general and specialty, used heavily in nursing programs were selected for analysis ( Table 9-7 ). “Critical content areas” were identified as key items that should appear in complete discussions of each content area (the pharmacology texts were treated somewhat differently, appropriate to their different scope), and included:

End-of-Life Care Content in 50 Nursing Textbooks.

- Palliative care defined

- Quality of life

- Other symptom assessment and management

- Communication with dying patients and their family members

- Role/needs of caregivers in end-of-life care

- Issues of policy, ethics, and law

- Bereavement

For each critical content area, a list of specific types of information were prespecified as important for inclusion in a text. For examples, under “Pain,” the topics identified were:

- definition of pain;

- assessment of pain—physical;

- assessment of meaning of pain—scales;

- pharmacologic management of pain at end of life (classes of analgesics);

- use of invasive techniques;

- principles of addiction, tolerance, and dependence;

- nonpharmacologic management of pain at end of life;

- physical pain versus suffering;

- side effects of opioids;

- barriers to pain management;

- fear of opioids hastening death or opioids near death;

- equianalgesia; and

- recognition of nurses' own burden in pain management.

The authors tallied the presence of end-of-life information in various ways, including examining tables of contents and indexes for mentions, as well as analyzing each text for the critical content areas. Among the key findings are the following:

- 1.4 percent of all chapters (24 out of 1,750) and 2 percent of all content (902 out of 45,683 pages) were devoted to any end-of-life topic;

- 30 percent of the texts had at least one chapter devoted to end-of-life issues (the vast majority were devoted only to pain);

- the strongest coverage was in the two areas of pain and issues of policy or ethics; end-of-life topics with the poorest coverage were quality of life issues and role and needs of family caregivers; and

- overall, 74 percent of the prespecified content was absent, 15 percent was present and 11 percent was present and useful or commendable.

The authors also qualitatively analyzed the information that was found in the texts, drawing a number of conclusions, among them:

- most end-of-life content focused only on cancer and AIDS;

- although pain was frequently discussed, the text referred mainly to acute or chronic pain, and not pain at the end of life; minimal content was found on pain assessment, neuropathic pain, or pain assessment in the cognitively impaired or nonverbal patient;

- outdated drug approaches were frequently recommended, and there was virtually no information on pain management at the end of life;

- minimal information was found on symptoms other than pain at the end of life; and

- the four pharmacology texts all included erroneous information and lacked information on current approaches to pain and symptom management.

The overarching finding was a lack of content on essential topics for end-of-life care.

Ongoing Programs and Initiatives

As is the case for education programs for physicians, much of support for nursing education comes from private foundations ( Table 9-8 ).

Major Recent and Ongoing End-of-Life Nursing Education Projects.

- SOCIAL WORK EDUCATION IN END-OF-LIFE CARE

Social workers are central to counseling, case management, and advocacy services for the dying and for bereaved families. With their focus on the psychosocial aspects of the dying process, they work not only with patients but with those around them in making decisions about treatment options, marshaling resources, helping families cope with terminal illness and death of a relative, and generally encouraging the best quality of life for all concerned. The demands on social workers have changed over time. A major reason is the shift from largely hospital-based care for those who are dying to home, hospice, and other settings, which has required social workers to coordinate a broadening array of services and providers and to navigate a more complex set of rules and regulations.

Just as nursing and medicine have begun to do, the social work profession has been examining its education process for preparing practitioners to care for dying patients and their families. Efforts to improve undergraduate and master's level social work training in this area are just getting under way in the United States, in comparison to the more mature field in Canada and England, and in comparison to medical and nursing education. Quite recently, opportunities have been identified, and some programs initiated, to begin making the needed changes.

End-of-Life Care Training in Social Work Education 3

Studies in the 1990s began to look at the end-of-life content of social work education and the preparedness of social workers to care for dying patients and their bereaved families. Four small but prominent studies set the stage for the most definitive review of this issue, by Christ and Sormanti (1999).

Briefly, of the four earlier studies, one was a survey of 108 hospice social workers from around the country, which found a uniform lack of preparation at the master's level for end-of-life care (Kovacs and Bronstein, 1998). The second consisted of a focus group of 10 oncology social work supervisors who described serious gaps in the social work curriculum related to end-of-life care (Sormanti, 1995).

A survey of social work programs found that in most, the end-of-life content was folded into courses on “human behavior and the social environment” or into gerontology courses. Less than a quarter of all students enrolled in these courses when they were electives (Dickinson et al., 1992). The last study was based on a questionnaire given to 50 M.S.W. students at the beginning of the second year, who reported feeling “a little” or “somewhat” prepared to deal with dying patients and their families (Kramer, 1998).

Though small and of varied types, these studies suggest that, like medicine and nursing, social work students have insufficient training—both didactic and practical—to provide the best care at the end of life. (No studies of social work textbooks for end-of-life care content have yet been carried out.)

Christ and Sormanti (1999) extended the earlier efforts with surveys and focus groups designed to address the following issues (of which the last two are of most interest in this section):

barriers to effective social work practice in palliative care and care of the bereaved,

the adequacy of M.S.W. practitioners' preparedness for this work, and

the extent of social work educators' experiences in teaching and research in bereavement and end-of-life care.

The first survey involved 48 oncology social workers attending the 1998 annual meeting of the Association of Oncology Social Workers. Regarding education, they were asked about their preparation in M.S.W. programs and about postgraduate training and educational opportunities. The practitioners uniformly reported insufficient training in end-of-life issues to prepare them for the work they were doing. None except for the few who had trained in hospice settings had clinical experience with dying patients. The respondents were asked about their preparation in 10 skill categories, with the result that in only two—supportive counseling and advocacy—did less than half rate their preparation as “unsatisfactory.” At least 50 percent rated end-of-life training in symptom management, communication, bereavement, education, ethics, case management, decisionmaking, and discharge planning as unsatisfactory.

Only one continuing education program associated with a school of social work was identified among the 48 participants. Overall, most lacked access to continuing education programs that were at all satisfactory. Even where programs exist, finding funds to attend and being able to take time away from work are significant barriers. In addition, most programs highlight medicine and nursing, and few social workers speak in the relevant courses. Five focus groups were held with social workers who provide end-of-life services, and they largely corroborated the findings of the survey.

Finally, 35 faculty members from 30 schools of social work were surveyed about end-of-life care content in their own programs and about research on related topics. They reported that only a small proportion of students receive instruction in end-of-life issues and that it comes in small parts of courses on human behavior and the social environment, policy, and practice. It usually consists of one or two lectures. More comprehensive elective courses were taken by a minority of students. Only one-quarter of survey participants believed that their schools adequately prepared students for end-of-life work.

Research funding was a very scarce commodity: about one-quarter reported even modest monetary support for their ongoing research. They reported that they were aware of no money targeted specifically for end-of-life research in social work.

Opportunities for Improving Social Work End-of-Life Education

Some specific areas that could benefit from funding and development of programs are

- better undergraduate and master's level curricula in end-of-life care;

- innovative programs that integrate coursework with clinical work through alliances between schools and practice sites;

- accessible continuing education designed and provided by social work experts in end-of-life care; and

- collaborative educational programs with other professions working with dying patients and bereaved families.

Also key is funding earmarked for social work research to provide a better foundation for the development of innovative methods of care.

The Project on Death in America has begun a program of Social Work Leadership Development Awards to promote innovative research and training projects for collaborations between schools of social work and practice sites that will advance the ongoing development of social work practice, education, and training in the care of the dying. The Hartford Foundation also provides support for gerontology social workers. The National Cancer Institute does not currently fund any social work education projects.

- RECOMMENDATIONS FOR IMPROVING PROFESSIONAL EDUCATION FOR PHYSICIANS, NURSES, AND SOCIAL WORKERS IN END-OF-LIFE CARE

Leaders in medicine, nursing, and social work have recognized that training in end-of-life care has been inadequate. These leaders have systematically documented at least some of the shortcomings in the education process and continue to add to the information base. This has been effective both in broadening recognition among the professions of the need for improvements and in serving as a basis for determining what tasks must be accomplished to effect improvements. The work has been concentrated among a small group of experts nationwide, and funding has come almost exclusively from private foundations, which have catalyzed these movements. At this point, the groundwork has been laid for larger-scale activities, which could move quickly with significant funding from the federal government, in particular, the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and other National Institutes of Health.

Few medical, nursing, or social work faculty, either at the undergraduate or graduate level, are knowledgeable and enthusiastic about end-of-life care and therefore are unlikely to be effective teachers. To compound this, little end-of-life care is included in the grand rounds, teaching conferences, or journals clubs of traditional continuing education programs. More intense faculty development programs should be offered to improve communication, mentoring, and other teaching skills.

Recommendation: NCI should fund a national oncology faculty development programs along the lines of the Project on Death in America Faculty Scholars Program.

New materials have to be created and existing materials improved for training new and practicing physicians, nurses, and social workers. This includes adding end-of-life content to textbooks, producing pocket guides and other references, and developing continuing education materials for practicing professionals.

Recommendation: NCI should make funding available for the development of appropriate materials, which could be pilot-tested by students and fellows in NCI-designated cancer centers. This could be accomplished through the “R25” mechanism, which was used to fund a small number of recent grants after a one-time call for proposals.

Coordination of Medical, Nursing, and Social Work Schools and Teaching Hospitals

Education takes place in a number of settings throughout the schooling process. Each medical, nursing, and social work school should develop a plan for teaching end-of-life care. This could be overseen by a committee with responsibility to review content across the entire curriculum, including preclinical and all phases of clinical education in outpatient, acute care hospital, long-term care, and home and hospice settings.

Coordination should also emphasize the need for interdisciplinary teamwork in caring for dying patients. Students should experience working together with physicians of different specialties, nurses, social workers, psychologists, other mental health workers, and clergy. They should also be instructed in caring for and have opportunities to interact with, dying patients and their families (Weissman et al., 1999).

Recommendation: In addition to coordination by the schools themselves, NCI should provide clinical training fellowship slots at all NCI-designated cancer centers that have clinical programs, including training in both clinical care and palliative or end-of-life care research for all of the relevant professions. Specific cancer centers could also be developed as “centers of excellence” for palliative and end-of-life care training and research.

The residency review committees that establish guidelines for clinical training have generally not mandated the inclusion of end-of-life or palliative care instruction. Perhaps presaging change, however, the internal medicine residency review committee has revised its guidelines to require instruction in palliative care and recommend clinical experiences in hospice and home care.

Recommendation: All residency review committees should be canvassed to determine the status of end-of-life care in each set of guidelines. Each specialty should be encouraged to consider appropriate changes, and technical assistance should be offered, if necessary. This activity would not require large amounts of funding, but some money for coordination and consultation should be made available by either the government, academic institutions, or foundations.

Both undergraduate licensing and graduate certification examinations have begun to include more questions on end-of-life care, but the content is still minimal. More questions on these exams will likely promote appropriate additions to the curricula.

Recommendation: Licensing and certifying bodies should be encouraged and assisted in developing appropriate examination questions.

This should be coordinated with curriculum development and textbook revisions. A coordinating function might be helpful in ensuring communication among the key players, funded by public or private sector sources.

In addition to the many unanswered clinical questions surrounding end-of-life care, there is research to be done that could directly benefit the education process. The “epidemiology of dying” would describe where, how, and under whose care patients die in different settings, including the interactions of physicians, nurses, social workers, clergy, family, and other caregivers. Information about the effect on physicians and other caregivers of caring for dying patients could also help guide education.

The transition period of “prognostic uncertainty,” when choices must be made in the face of an uncertain outcome, is relatively unstudied in terms of what the choices are for patients and physicians.

Recommendation: NCI should initiate a grant program for these activities by issuing a request for proposals in this area and by continuing such a program over the long term.

Standard-setting organizations such as JCAHO can promote more comprehensive end-of-life care requirements for hospitals, nursing homes, and other institutions. They also can help to educate medical administrators about quality end-of-life care (Weissman et al., 1999).

Recommendation: Private sector organizations should be encouraged by government to undertake these activities and should be provided with technical assistance, if needed. Funding could come from either public or private sector sources.

- American Medical Association. The EPEC Project . 2000. Web page, http://222 .ama-asn.org/ethic/epec/epec .htm .

- Barnard D, Quill T, Hafferty FW, et al. Preparing the ground: contributions of the preclinical years to medical education for care near the end of life . Academic Medicine 1999 ; 74:499– 505. [ PubMed : 10353280 ]

- Barzansky B, Veloski JJ, Miller R, Jonas HS. Palliative care and end-of-life education . Aca demic Medicine 1999 ; 74(10):S102–104. [ PubMed : 10536608 ]

- Begg L. National Cancer Institute, Cancer Training Branch. Personal communication, June 21, 2000.

- Belani CP, Belcher AE, Sridhara R, Schimper SC. Instruction in the techniques and concept of supportive care in oncology . Supportive Care Cancer . 1994; 2:50–55. Cited in Billings and Block (1997). [ PubMed : 8156257 ]

- Berkow R, editor. , ed. 1992. The Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy . 16 th ed. Rahway, NJ: Merck Research Laboratories.

- Billings, JS, Block S. Palliative care in undergraduate medical education . JAMA 1997 ; 28:733– 738. [ PubMed : 9286833 ]

- Block SD, Bernier GM, Crawley LM. Incorporating palliative care into primary care education . JGIM; 1998 ; 13:768–773. [ PMC free article : PMC1497022 ] [ PubMed : 9824524 ]

- Carron AT, Lynn J, Keaney P. End-of-life care in medical textbooks . Arch Intern Med 1999 ; 130:82–6. [ PubMed : 9890873 ]

- Christ GH, Sormanti M. Advancing social work practice in end-of-life care . Social Work in Health Care 1999 ; 30(2):81–99. [ PubMed : 10839248 ]

- Dickinson G, Sumner E, Frederick L. Death education in selected health professions . Death Studies 1992 ; 16:281–289. Cited in Christ and Sormanti (1999). [ PubMed : 10118944 ]

- Emanuel EJ. National Cancer Institute. Personal communication (unpublished data), 2000.

- Ewald GA, editor; , McKenzie CR, editor. , eds. 1995. Manual of Medical Therapeutics . 28 th edition. Boston: Little, Brown.

- Ferrell BR, Grant M, Virani R. Strengthening nursing education to improve end-of-life care . Nursing Outlook 1999a ; 47:252–256. [ PubMed : 10626282 ]

- Ferrell BR, McCaffery M. Nurses' knowledge about equianalgesia and opioid dosing . Cancer Nursing 1997 ; 20(3):201–212. [ PubMed : 9190095 ]

- Ferrell B, Virani R, Grant M. Analysis of end-of-life content in nursing textbooks . Oncol Nurs Forum 1999b ; 26(5):869–876. [ PubMed : 10382185 ]

- Ferrell B, Virani R, Grant M, et al. Beyond the Supreme Court decision: nursing perspectives on end-of-life care . Oncology Nursing Forum 2000 ; 27(3):445–455. [ PubMed : 10785899 ]

- Foley KM. Competent care for the dying instead of physician-assisted suicide . New England Journal of Medicine 1997 ; 336:54–58. [ PubMed : 8970941 ]

- Gibson R. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation projects to promote professional education and training. Personal communication, June 2000.

- Hilden JM, Emanuel EJ, Fairclough DL, Link MP, Foley KM, Clarridge BC, Schnipper LE, Mayer RJ. Attitudes and practices among pediatric oncologists regarding end-of-life care: results of the 1998 American Society of Clinical Oncology survey . JCO 2001 ; 19: 205–212. [ PubMed : 11134214 ]

- Hill TP. Treating the dying patient: the challenge for medical education . Arch Intern Med 1995 ; 155:1265–1269. Cited in Billings and Block (1997). [ PubMed : 7778956 ]

- Holleman WL, Holleman MC, Gershenshorn S. Death education curricula in U.S. medical schools . Teaching Learning Med 1994 ; 6:260–263. Cited in Billings and Block (1997).

- Institute of Medicine (IOM). 1997. Approaching Death: Improving Care at the End of Life , Field MJ, editor; , Cassel CK, editor. , eds. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press. [ PubMed : 25121204 ]

- Isselbacher K, editor; , Martin W, editor; , Kasper F, editor. , eds. 1994. Harrison's principles of internal medicine , 13th ed . New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Kovacs P, Bronstein L. Preparation for oncology settings: what hospice social workers say they need . Social Work in Health Care 1999 ; 24(1):57–64. Cited in Christ and Sormanti (1999). [ PubMed : 14533420 ]

- Kramer B. Preparing social workers for the inevitable: A preliminary investigation of a course on grief, death, and loss . Journal of Social Work Education 1998 ; 34(2):1–17. Cited in Christ and Sormanti (1999).

- Larson DE, editor. , ed. 1996. Mayo Clinic Family Health Book . 2 nd edition. New York: W.Morrow.

- McCaffery M, Ferrell BR. Nurses' knowledge about cancer pain: a survey of five countries . Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 1995 ; 10(5):356–369. [ PubMed : 7673768 ]

- Medical School Objectives Writing Group. Learning objectives for medical student education: guidelines for medical schools. Report I of the Medical School Objectives Project . Aca demic Medicine 1999 ; 74:418–422. [ PubMed : 9934288 ]

- Mermann AC, Gunn DB, Dickinson GE. Learning to care for the dying: a survey of medical schools and a model course . Academic Medicine 1991 ; 66(1):25–28. [ PubMed : 1985674 ]

- Osler W. 1899. Principles and Practice of Medicine , 3 rd edition. New York: D.Appleton.

- Rabow MW, Hadie GE, Fair JM, McPhee SJ. End-of-life care content in 50 textbooks from multiple specialties . JAMA 2000 ; 283:771–778. [ PubMed : 10683056 ]

- SAM-CD. 1994. Scientific American Medicine on CD-ROM: A Comprehensive Knowledge- Base of Internal Medicine . New York: Scientific American Medicine.

- Sormanti M. Fieldwork instruction in oncology social work: supervisory issues . Journal of Psychosocial Oncology 1994 ; 12(3):73–87. Cited in Christ and Sormanti (1999).

- Weissman DE, Block SD, Blank L et al. Recommendations for incorporating palliative care education into the acute care hospital setting . Academic Medicine 1999 ; 74:871–877. [ PubMed : 10495725 ]

The section is taken verbatim from Billings and Block (1997).

Drawn and adapted largely from Block et al. (1998) except as noted.

This section is largely based on the work of Christ and Sormanti (1999).

- Cite this Page Institute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council (US) National Cancer Policy Board; Foley KM, Gelband H, editors. Improving Palliative Care for Cancer. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2001. 9, Professional Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Physicians, Nurses, and Social Workers.

- PDF version of this title (6.2M)

In this Page

Related information.

- PMC PubMed Central citations

- PubMed Links to PubMed

Recent Activity

- Professional Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Physicians, Nurses... Professional Education in Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Physicians, Nurses, and Social Workers - Improving Palliative Care for Cancer

Your browsing activity is empty.

Activity recording is turned off.

Turn recording back on

Connect with NLM

National Library of Medicine 8600 Rockville Pike Bethesda, MD 20894

Web Policies FOIA HHS Vulnerability Disclosure

Help Accessibility Careers

- What Is Social Work?

- How Long Does it Take to Become a Social Worker?

- LMSW vs. LCSW: What’s the difference?

- Macro, Mezzo, and Micro Social Work

- Associate Degree in Social Work (ASW)

- Online BSW Programs

- Online Clinical MSW Programs

- Advanced Standing Online MSW Programs

- Online MSW Programs with No GRE Required

- SocialWork@Simmons

- Howard University’s Online MSW

- OnlineMSW@Fordham

- Syracuse University’s Online MSW

- Online Social Work at CWRU

- Is an Online Master’s in Social Work (MSW) Degree Worth it?

- MSW Programs in California

- MSW Programs in Colorado

- MSW Programs in Massachusetts

- MSW Programs in New York

- MSW Programs in Ohio

- MSW Programs in Texas

- MSW vs LCSW

- What is a Master of Social Work (MSW) Degree?

- What Can I Do with an MSW Degree? MSW Career Paths

- HBCU MSW Programs – Online and On-Campus Guide

- DSW vs. Ph.D. in Social Work

- Ph.D. in Social Work

- Social Work Continuing Education

- Social Work Licensure

- How to Become a Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW)

- Community Social Worker

- Child and Family Social Worker

- Forensic Social Worker

- Geriatric Social Worker

- Hospice Social Worker

- Medical Social Worker

- Mental Health Social Worker

- Resources for Military Social Workers

- Oncology Social Worker

- Psychiatric Social Worker

- Resources for School Social Workers

- Social Work Administrator

- Social Work vs. Therapy

- Social Work Salary

- Social Work Collaborations

- Social Work Career Pathways

- Social Work vs. Sociology

- Benefits of a Part-Time MSW Program

- MSW vs. MPH

- Social Work vs. Counseling

- Social Work vs. Psychology

- Bachelor’s in Psychology Programs Online

- Master’s Degree in Counseling

- Become a School Counselor

- School Counselor Salary

- Become a Mental Health Counselor

- Advantages of Veterinary Social Work

- Practicing Anti-Racism in Social Work: A Guide

- Social Work License Exam Prep

- Theoretical Approaches in Social Work: Systems Theory

- Social Learning Theory

- Sarah Frazell on Racism

- Lisa Primm on Macro Social Work

- Jessica Holton on Working With Clients Who Are Deaf and Hard of Hearing

- Cornell Davis III on Misperceptions About the Child Welfare Field

- Morgan Gregg on Working with Law Enforcement

- Social Work Grants

- Social Work Scholarships

- Social Work Internships

- Social Work Organizations

- Social Work Volunteer Opportunities

- Social Worker Blogs

- Social Work Podcasts

- Social Workers on Twitter

- Ethnic and Minority Social Work Resources

- Resources for LGBTQIA Social Work

- Mental Health Resources List

Home / Social Work Careers / Hospice Social Worker

Guide to Becoming a Hospice and Palliative Care Social Worker

Hospice and palliative care social workers work alongside medical workers to provide end-of-life care for patients. If you decide to pursue this challenging and rewarding branch of social work, you may need additional training and certification depending on your educational background. Below, we provide you with some resources to help you pursue your career as a hospice and palliative care social worker.

What is a Palliative and Hospice Social Worker?

Palliative social work and hospice social work have subtle, usually overlapping distinctions. Hospice social work is a category within palliative care that specifically deals with end-of-life care for people with terminal illnesses. Palliative care may or may not deal with people suffering from terminal illnesses; the focus is on managing symptoms rather than curing a condition that might be incurable.

Your day-to-day responsibilities in this field will vary. In general, social workers in palliative care settings help all parties—patients, medical professionals, families—communicate with each other.

Sponsored online social work programs

University of Denver

Master of social work (msw).

The University of Denver’s Online MSW Program is delivered by its top-ranked school of social work and offers two programs. Students can earn their degree in as few as 12 months for the Online Advanced-Standing MSW or 27 months for the Online MSW.

- Complete the Online Advanced-Standing MSW in as few as 12 months if you have a BSW; if you do not have a BSW, the Online MSW Program may be completed in as few as 27 months.

- No GRE Required

- Customizable pathway options include Mental Health and Trauma or Health, Equity and Wellness concentrations

Fordham University

Fordham’s skills-based, online MSW program integrates advanced relevant social work competencies, preparing students to serve individuals and communities while moving the profession forward. This program includes advanced standing and traditional MSW options.

- Traditional and advanced standing online MSW options are available.

- There are four areas of focus: Individuals and Families, Organizations and Community, Evaluation, and Policy Practice and Advocacy.

- Pursue the degree on a full-time or part-time track.

Hawaii Pacific University

Master of social work.

The online Master of Social Work prepares aspiring social work leaders to develop a multicultural social work practice, advocate for social and economic justice, and empower diverse communities affected by systemic inequities within civilian and military-focused areas.

- Learn how to develop a multicultural social work practice.

- Pending accreditation by the Council on Social Work Education (CSWE).

- Complete in 18 months full time, or in 36 months part time on the traditional track.

- Complete in 12 months full time or 24 months part time on the Advanced Standing Track.

Simmons University

Aspiring direct practitioners can earn their MSW online from Simmons University in as few as 9 months . GRE scores are not required, and the program offers full-time, part-time, accelerated, and advanced standing tracks.

- Prepares students to pursue licensure, including LCSW

- Full-time, part-time, and accelerated tracks

- Minimum completion time: 9 months

Howard University

The online Master of Social Work program from Howard University School of Social Work prepares students for advanced direct or macro practice in culturally diverse communities. Two concentrations available: Direct Practice and Community, Administration, and Policy Practice. No GRE. Complete in as few as 12 months.

- Concentrations: Direct Practice and Community, Administration, and Policy Practice

- Complete at least 777-1,000 hours of agency-based field education

- Earn your degree in as few as 12 months

Syracuse University

Syracuse University’s online Master of Social Work program does not require GRE scores to apply and is focused on preparing social workers who embrace technology as an important part of the future of the profession. Traditional and Advanced Standing tracks are available.

- Traditional and Advanced Standing tracks

- No GRE required

- Concentrate your degree in integrated practice or clinical practice

Case Western Reserve University

In as few as a year and a half, you can prepare for social work leadership by earning your Master of Social Work online from Case Western Reserve University’s school of social work.

- CSWE-accredited

- No GRE requirement

- Complete in as few as one and a half years

info SPONSORED

Steps to Become a Palliative Care and Hospice Social Worker

Below are some common steps to become a palliative care and hospice social worker:

1. Complete Your Social Work Education

A common first step to becoming a palliative care or hospice care social worker is obtaining an appropriate background in generalized social work education at an accredited school. For some entry-level jobs, a bachelor’s degree in social work or a related major, such as psychology, is sufficient; some jobs in the social work field (such as aides) may only require a high school diploma. More commonly, however, social workers obtain a Master of Social Work (MSW) to meet state licensing guidelines.

2. Gain Fieldwork Experience

Education may need to be supplemented with fieldwork, which both BSW and MSW programs will likely require. Specifications for required hours will vary by state, requirements such as these are not uncommon.

3. Apply for and Pass the ASWB Exam

To obtain a social work license, you likely will need to pass a licensing exam administered by the Association of Social Work Boards (ASWB).

4. Apply for Licensure

Once you pass your ASWB exam and scores are sent to your state of practice, you may then apply for state licensure as a licensed social worker.

5. Pursue Employment

Finally, you will need to look for work in palliative care or at a hospice. You may already have contacts through your fieldwork; otherwise, you can search for jobs using keywords such as “hospice social worker,” “end-of-life social worker,” or “palliative care social worker.”

Should I Become a Hospice Social Worker?