Big Five Personality Traits: The OCEAN Model Explained

“Who are you?”

It’s a simple enough question, but it’s one of the hardest ones to answer.

There are many ways to interpret that question. An answer could include your name, your job title, your role in your family, your hobbies or passions, and your place of residence or birth. A more comprehensive answer might include a description of your beliefs and values.

Every one of us has a different answer to this question, and each answer tells a story about who we are. While we may have a lot in common with our fellow humans, like race, religion, sexual orientation, skills, and eye color, there is one thing that makes us each unique: personality.

You can meet hundreds, thousands, or even tens of thousands of people, but no two will be exactly the same. Which raises the question: how do we categorize and classify something as widely varied as personality?

In this article, we’ll define what personality is, explore the different ways personalities can be classified (and how those classifications have evolved), and explain the OCEAN model, one of the most ubiquitous personality inventories in modern psychology.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Strengths Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help your clients realize their unique potential and create a life that feels energizing and authentic.

This Article Contains

What is personality, personality research: a brief review, ocean: the five factors, the trait network, assessing the big five, a take-home message, frequently asked questions.

Personality is an easy concept for most of us to grasp. It’s what makes you, you. It encompasses all the traits, characteristics, and quirks that set you apart from everyone else.

In the world of psychology research, personality is a little more complicated. The definition of personality can be complex, and the way it is defined can influence how it is understood and measured.

According to the researchers at the Personality Project, personality is “the coherent pattern of affect, cognition, and desires (goals) as they lead to behavior” (Revelle, 2013).

Meanwhile, the American Psychological Association (APA) defines personality as “individual differences in characteristic patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving” (2017).

However you define personality, it’s an important part of who you are. In fact, personality shows a positive correlation with life satisfaction (Boyce, Wood, & Powdthavee, 2013). With personality having such a large impact on our lives, it’s important to have a reliable way to conceptualize and measure it.

The most prevalent personality framework is the Big Five, also known as the five-factor model of personality. Not only does this theory of personality apply to people in many countries and cultures around the world (Schmitt et al., 2007), it provides a reliable assessment scale for measuring personality.

To understand how we got to the Big Five, we have to go back to the beginning of personality research.

Ancient Greece

It seems that for as long as there have been humans with personalities, there have been personality theories and classification systems.

The ancient Greek physician Hippocrates hypothesized that two binaries define temperament: hot versus cold and moist versus dry. This theory resulted in four possible temperaments (hot/moist, hot/dry, cold/moist, cold/dry) called humors , which were thought to be key factors in both physical health issues and personality peculiarities.

Later, the philosopher Plato suggested a classification of four personality types or factors: artistic (iconic), sensible (pistic), intuitive (noetic), and reasoning (dianoetic).

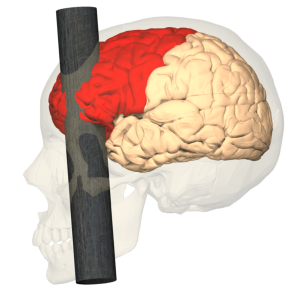

Plato’s renowned student Aristotle mused on a possible connection between the physical body and personality, but this connection was not a widespread belief until the rise of phrenology and the shocking case of Phineas Gage.

Phrenology and Phineas Gage

Phrenology, a pseudoscience that is not based on any verifiable evidence, was promoted by a neuroanatomist named Franz Gall in the late 18th century. Phrenology hypothesizes a direct relationship between the physical properties of different areas of the brain (such as size, shape, and density) and opinions, attitudes, and behaviors.

While phrenology was debunked relatively quickly, it marked one of the first attempts to tether an individual’s traits and characteristics to the physical brain. And it wasn’t long before actual evidence of this connection presented itself.

In 1848, one man’s unfortunate accident forever changed mainstream views on the interconnectivity of the brain and personality.

A railroad construction worker named Phineas Gage was on the job when a premature detonation of explosive powder launched a 3.6 foot (1.1 m), 13.25 pound (6 kg) iron rod into Gage’s left cheek, through his head, and out the other side.

Gage, astonishingly, survived the incident, and his only physical ailments (at first) were blindness in his left eye and a wound where the rod penetrated his head.

However, his friends reported that his personality had completely changed after the accident—suddenly he could not keep appointments, showed little respect or compassion for others, and uttered “the grossest profanity.” He died in 1860 after suffering from a series of seizures (Twomey, 2010).

This was the first case that was widely recognized as clear evidence of a link between the physical brain and personality, and it gained national attention. Interest in the psychological conception of personality spiked, leading to the next phase in personality research.

Sigmund Freud

The Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud is best known as the father of psychoanalysis , an intensive form of therapy that digs deep into an individual’s life—especially childhood—to understand and treat psychological ailments.

However, Freud also focused on personality, and some of his ideas are familiar to many people. One of his most fleshed-out theories held that the human mind consists of three parts: the id, the ego, and the superego.

The id is the primal part of the human mind that runs on instinct and aims for survival at all costs. The ego bridges the gap between the id and our day-to-day experiences, providing realistic ways to achieve the wants and needs of the id and coming up with justifications for these desires.

The superego is the part of the mind that represents humans’ higher qualities, providing the moral framework that humans use to regulate their baser behavior.

While scientific studies have largely not supported Freud’s idea of a three-part mind, this theory did bring awareness to the fact that at least some thoughts, behaviors, and motivations are unconscious. After Freud, people began to believe that behavior was truly the tip of the iceberg when assessing a person’s attitudes, opinions, beliefs, and unique personality.

Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung was influenced by Freud, his mentor, but ultimately came up with his own system of personality. Jung believed that there were some overarching types of personality that each person could be classified into based on dichotomous variables.

For example, Jung believed that individuals were firmly within one of two camps:

- Introverts , who gain energy from the “internal world” or from solitude with the self;

- Extroverts, who gain energy from the “external world” or from interactions with others.

This idea is still prevalent today, and research has shown that this is a useful differentiator between two relatively distinct types of people. Today, most psychologists see introversion and extroversion as existing on a spectrum rather than a binary. It can also be situational, as some situations exhaust our energy one day and on other days, fuel us to be more social.

Jung also identified what he found to be four essential psychological functions:

He believed that each of these functions could be experienced in an introverted or extroverted fashion and that one of these functions is more dominant than the others in each person.

Jung’s work on personality had a huge impact on the field of personality research that’s still felt today. In fact, the popular Myers-Briggs Type Indicator® test is based in part on Jung’s theories of personality.

Abraham Maslow and Carl Rogers

American psychologist Abraham Maslow furthered an idea that Freud brought into the mainstream: At least some aspects or drivers of personality are buried deep within the unconscious mind.

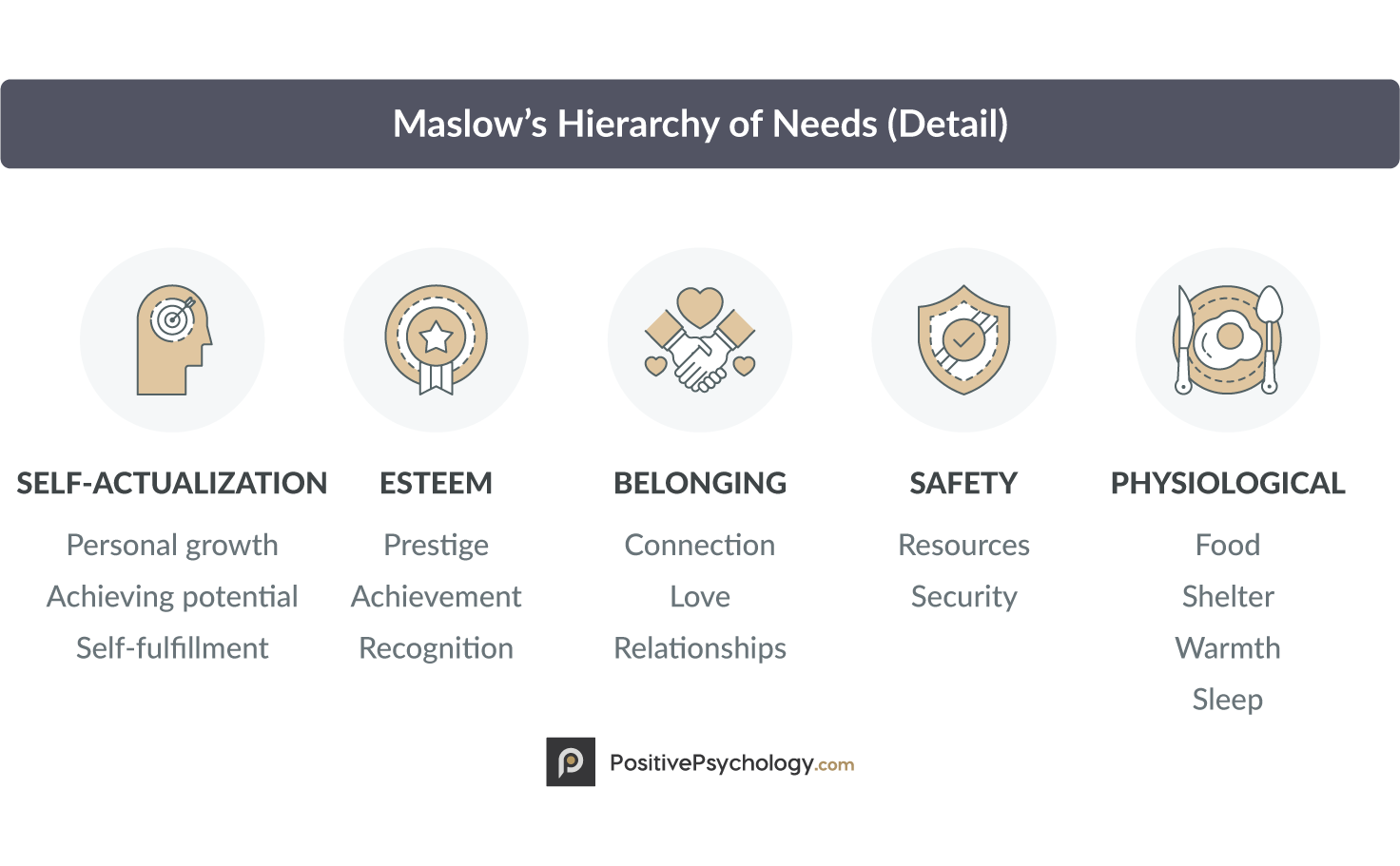

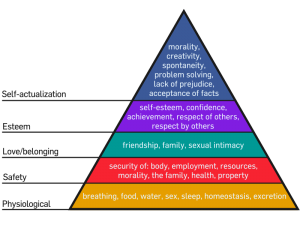

Maslow hypothesized that personality is driven by a set of needs that each human has. He organized these needs into a hierarchy, with each level requiring fulfillment before a higher level can be fulfilled.

The pyramid is organized from bottom to top (pictured to the right), beginning with the most basic need (McLeod, 2007):

- Physiological needs (food, water, warmth, rest);

- Safety needs (security, safety);

- Belongingness and love needs (intimate relationships, friends);

- Esteem needs (prestige and feelings of accomplishment);

- Self-actualization needs (achieving one’s full potential, self-fulfillment).

Maslow believed that all humans aim to fulfill these needs, usually in order from the most basic to the most transcendent, and that these motivations result in the behaviors that make up a personality.

Carl Rogers , another American psychologist, built upon Maslow’s work, agreeing that all humans strive to fulfill needs, but Rogers disagreed that there is a one-way relationship between striving toward need fulfillment and personality. Rogers believed that the many different methods humans use to meet these needs spring from personality, rather than the other way around.

Rogers’ contributions to the field of personality research signaled a shift in thinking about personality. Personality was starting to be seen as a collection of traits and characteristics that were not necessarily permanent rather than a single, succinct construct that can be easily described.

Multiple Personality Traits

In the 1940s, German-born psychologist Hans Eysenck built off of Jung’s dichotomy of introversion versus extroversion, hypothesizing that there were only two defining personality traits : extroversion and neuroticism. Individuals could be high or low on each of these traits, leading to four key types of personalities.

Eysenck also connected personality to the physical body in a greater way than most earlier psychology researchers and philosophers. He posited that differences in the limbic system resulted in varying hormones and hormonal activation. Those who were already highly stimulated (introverts) would naturally seek out less stimulation while those who were naturally less stimulated (extroverts) would search for greater stimulation.

Eysenck’s thoroughness in connecting the body to the mind and personality pushed the field toward a more scientific exploration of personality based on objective evidence rather than solely philosophical musings.

American psychologist Lewis Goldberg may be the most prominent researcher in the field of personality psychology. His groundbreaking work whittled down Raymond Cattell’s 16 “fundamental factors” of personality into five primary factors, similar to the five factors found by fellow psychology researchers in the 1960s.

The five factors Goldberg identified as primary factors of personality are:

Extroversion

Agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism.

- Openness to experience

This five-factor model caught the attention of two other renowned personality researchers, Paul Costa and Robert McCrae, who confirmed the validity of this model. This model was named the “Big Five” and launched thousands of explorations of personality within its framework, across multiple continents and cultures and with a wide variety of populations.

The Big Five brings us right up to the current era in personality research. The Big Five theory still holds sway as the prevailing theory of personality, but some salient aspects of current personality research include:

- Conceptualizing traits on a spectrum instead of as dichotomous variables;

- Contextualizing personality traits (exploring how personality shifts based on environment and time);

- Emphasizing the biological bases of personality and behavior.

Since the Big Five is still the most mainstream and widely accepted framework for personality, the rest of this piece will focus exclusively on this framework.

As noted above, the five factors grew out of decades of personality research, growing from the foundations of Cattell’s 16 factors and eventually becoming the most accepted model of personality to date. This model has been translated into several languages and applied in dozens of cultures, resulting in research that not only confirms its validity as a theory of personality but also establishes its validity on an international level.

These five factors do not provide completely exhaustive explanations of personality, but they are known as the Big Five because they encompass a large portion of personality-related terms. The five factors are not necessarily traits in and of themselves, but factors in which many related traits and characteristics fit.

For example, the factor agreeableness encompasses terms like generosity, amiability, and warmth on the positive side and aggressiveness and temper on the negative side. All of these traits and characteristics (and many more) make up the broader factor of agreeableness.

Below, we’ll explain each factor in more detail and provide examples and related terms to help you get a sense of what aspects and quirks of personality these factors cover.

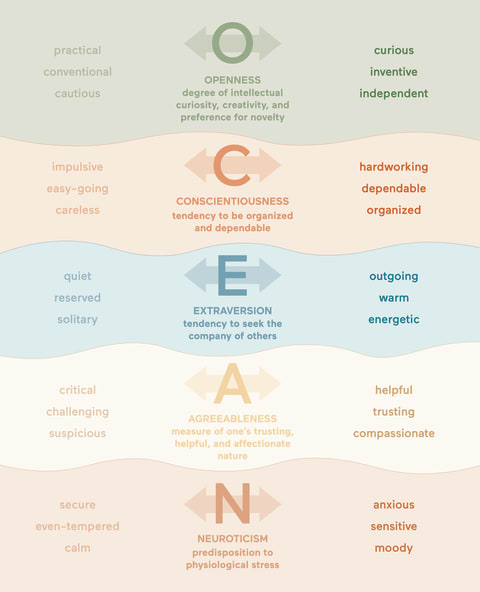

A popular acronym for the Big Five is OCEAN. The five factors are laid out in that order here.

1. Openness to Experience

Openness to experience has been described as the depth and complexity of an individual’s mental life and experiences (John & Srivastava, 1999). It is also sometimes called intellect or imagination.

Openness to experience concerns people’s willingness to try to new things, their ability to be vulnerable, and their capability to think outside the box.

Common traits related to openness to experience include:

- Imagination;

- Insightfulness;

- Varied interests;

- Originality;

- Daringness;

- Preference for variety;

- Cleverness;

- Creativity;

- Perceptiveness;

- Complexity/depth.

An individual who is high in openness to experience is likely someone who has a love of learning, enjoys the arts, engages in a creative career or hobby, and likes meeting new people (Lebowitz, 2016a).

An individual who is low in openness to experience probably prefers routine over variety, sticks to what he or she knows, and prefers less abstract arts and entertainment.

2. Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness is a trait that can be described as the tendency to control impulses and act in socially acceptable ways, behaviors that facilitate goal-directed behavior (John & Srivastava, 1999). Conscientious people excel in their ability to delay gratification, work within the rules, and plan and organize effectively.

Traits within the conscientiousness factor include:

- Persistence;

- Thoroughness;

- Self-discipline ;

- Consistency;

- Predictability;

- Reliability;

- Resourcefulness;

- Perseverance;

People high in conscientiousness are likely to be successful in school and in their careers, to excel in leadership positions , and to doggedly pursue their goals with determination and forethought (Lebowitz, 2016a).

People low in conscientiousness are much more likely to procrastinate and to be flighty, impetuous, and impulsive.

3. Extroversion

It concerns where an individual draws their energy from and how they interact with others. In general, extroverts draw energy from or recharge by interacting with others, while introverts get tired from interacting with others and replenish their energy with solitude.

- Sociableness;

- Assertiveness ;

- Outgoing nature;

- Talkativeness;

- Ability to be articulate;

- Fun-loving nature;

- Tendency for affection;

- Friendliness;

- Social confidence.

The traits associated with extroversion are:

People high in extroversion tend to seek out opportunities for social interaction, where they are often the “life of the party.” They are comfortable with others, are gregarious, and are prone to action rather than contemplation (Lebowitz, 2016a).

People low in extroversion are more likely to be people “of few words who are quiet, introspective, reserved, and thoughtful.

Download 3 Free Strengths Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to discover and harness their unique strengths.

Download 3 Free Strengths Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

4. Agreeableness

This factor concerns how well people get along with others. While extroversion concerns sources of energy and the pursuit of interactions with others, agreeableness concerns one’s orientation to others. It is a construct that rests on how an individual generally interacts with others.

The following traits fall under the umbrella of agreeableness:

- Humbleness;

- Moderation;

- Politeness;

- Unselfishness;

- Helpfulness;

- Sensitivity;

- Amiability;

- Cheerfulness;

- Consideration.

People high in agreeableness tend to be well-liked, respected, and sensitive to the needs of others. They likely have few enemies and are affectionate to their friends and loved ones, as well as sympathetic to the plights of strangers (Lebowitz, 2016a).

People on the low end of the agreeableness spectrum are less likely to be trusted and liked by others. They tend to be callous, blunt, rude, ill-tempered, antagonistic, and sarcastic. Although not all people who are low in agreeableness are cruel or abrasive, they are not likely to leave others with a warm fuzzy feeling.

5. Neuroticism

These traits are commonly associated with neuroticism:

- Awkwardness;

- Pessimism ;

- Nervousness;

- Self-criticism;

- Lack of confidence ;

- Insecurity;

- Instability;

- Oversensitivity.

Those high in neuroticism are generally prone to anxiety, sadness, worry, and low self-esteem. They may be temperamental or easily angered, and they tend to be self-conscious and unsure of themselves (Lebowitz, 2016a).

Individuals who score on the low end of neuroticism are more likely to feel confident, sure of themselves, and adventurous. They may also be brave and unencumbered by worry or self-doubt.

Because the Big Five are so big, they encompass many other traits and bundle related characteristics into one cohesive factor.

Openness to Experience

Openness to experience has been found to contribute to one’s likelihood of obtaining a leadership position , likely due to the ability to entertain new ideas and think outside the box (Lebowitz, 2016a). Openness is also connected to universalism values, which include promoting peace and tolerance and seeing all people as equally deserving of justice and equality (Douglas, Bore, & Munro, 2016).

Further, research has linked openness to experience with broad intellectual skills and knowledge, and it may increase with age (Schretlen, van der Hulst, Pearlson, & Gordon, 2010). This indicates that openness to experience leads to gains in knowledge and skills, and it naturally increases as a person ages and has more experiences to learn from.

Not only has openness been linked to knowledge and skills, but it was also found to correlate positively with creativity, originality, and a tendency to explore their inner selves with a therapist or psychiatrist, and to correlate negatively with conservative political attitudes (Soldz & Vaillant, 1999).

Not only has openness been found to correlate with many traits, but it has also been found to be extremely stable over time—one study explored trait stability over 45 years and found participants’ openness to experience (along with extroversion and neuroticism) remained relatively stable over that period (Soldz & Vaillant, 1999)

Concerning the other Big Five factors, openness to experience is weakly related to neuroticism and extroversion and is mostly unrelated to agreeableness and conscientiousness (Ones, Viswesvaran, & Reiss, 1996).

Openness to experience is perhaps the trait that is least likely to change over time, and perhaps most likely to help an individual grow . Those high in openness to experience should capitalize on their advantage and explore the world, themselves, and their passions. These individuals make strong and creative leaders and are most likely to come up with the next big innovation.

This factor has been linked to achievement, conformity, and seeking out security, as well as being negatively correlated to placing a premium on stimulation and excitement (Roccas, Sagiv, Schwartz, & Knafo, 2002). Those high in conscientiousness are also likely to value order, duty, achievement, and self-discipline, and they consciously practice deliberation and work toward increased competence (Roccas, Sagiv, Schwartz, & Knafo, 2002).

In light of these correlations, it’s not surprising that conscientiousness is also strongly related to post-training learning (Woods, Patterson, Koczwara, & Sofat, 2016), effective job performance (Barrick & Mount, 1991), and intrinsic and extrinsic career success (Judge, Higgins, Thoresen, & Barrick, 1999).

The long-term study by Soldz and Vaillant (1999) found that conscientiousness was positively correlated with adjustment to life’s challenges and mature defensive responses, indicating that those high in conscientiousness are often well-prepared to tackle any obstacles that come their way.

Conscientiousness is negatively correlated with depression, smoking, substance abuse, and engagement in psychiatric treatment. The trait was also found to correlate somewhat negatively with neuroticism and somewhat positively with agreeableness, but it had no discernible relation to the other factors (Ones, Viswesvaran, & Reiss, 1996).

From these results, it’s clear that those gifted with high conscientiousness have a distinct advantage over those who are not. Those with high conscientiousness should attempt to use their strengths to the best of their abilities, including organization, planning, perseverance, and tendency towards high achievement.

As long as the highly conscientious do not fall prey to exaggerated perfectionism, they are likely to achieve many of the traditional markers of success.

Extroverts are often assertive, active, and sociable, shunning self-denial in favor of excitement and pleasure.

Considering these findings, it follows that high extroversion is a strong predictor of leadership , and contributes to the success of managers and salespeople as well as the success of all job levels in training proficiency (Barrick & Mount, 1991).

Over a lifetime, high extroversion correlates positively with a high income, conservative political attitudes, early life adjustment to challenges, and social relationships (Soldz & Vaillant, 1999).

The same long-term study also found that extroversion was fairly stable across the years, indicating that extroverts and introverts do not often shift into the opposite state (Soldz & Vaillant, 1999).

Because of its ease of measurement and general stability over time, extroversion is an excellent predictor of effective functioning and general well-being (Ozer & Benet-Martinez, 2006), positive emotions (Verduyn & Brans, 2012), and overconfidence in task performance (Schaefer, Williams, Goodie, & Campbell, 2004).

When analyzed in relation to the other Big Five factors, extroversion correlated weakly and negatively with neuroticism and was somewhat positively related to openness to experience (Ones, Viswesvaran, & Reiss, 1996).

Those who score high in extroversion are likely to make friends easily and enjoy interacting with others, but they may want to pay extra attention to making well-thought-out decisions and considering the needs and sensitivities of others.

Agreeableness may be motivated by the desire to fulfill social obligations or follow established norms, or it may spring from a genuine concern for the welfare of others. Whatever the motivation, it is rarely accompanied by cruelty, ruthlessness, or selfishness (Roccas, Sagiv, Schwartz, & Knafo, 2002).

Those high in agreeableness are also more likely to have positive peer and family relationships, model gratitude and forgiveness , attain desired jobs, live long lives, experience relationship satisfaction, and volunteer in their communities (Ozer & Benet-Martinez, 2006).

Agreeableness affects many life outcomes because it influences any arena in which interactions with others are important—and that includes almost everything. In the long-term, high agreeableness is related to strong social support and healthy midlife adjustment but is slightly negatively correlated to creativity (Soldz & Vaillant, 1999).

Those who are friendly and endearing to others may find themselves without the motivation to achieve a traditional measure of success, and they might choose to focus on family and friends instead.

Agreeableness correlates weakly with extroversion and is somewhat negatively related to neuroticism and somewhat positively correlated to conscientiousness (Ones, Viswesvaran, & Reiss, 1996).

Individuals high in agreeableness are likely to have many close friends and a good relationship with family members, but there is a slight risk of consistently putting others before themselves and missing out on opportunities for success, learning, and development.

Those who are friendly and agreeable to others can leverage their strengths by turning to their social support networks for help when needed and finding fulfillment in positive engagement with their communities.

Neuroticism has been found to correlate negatively with self-esteem and general self-efficacy , as well as with an internal locus of control (feeling like one has control over his or her own life) (Judge, Erez, Bono, & Thoresen, 2002). In fact, these four traits are so closely related that they may fall under one umbrella construct.

In addition, neuroticism has been linked to poorer job performance and lower motivation, including motivation related to goal-setting and self-efficacy (Judge & Ilies, 2002). It likely comes as no surprise that instability and vulnerability to stress and anxiety do not support one’s best work.

The anxiety and self-consciousness components of neuroticism are also positively linked to more traditional values and are negatively correlated with achievement values.

The hostility and impulsiveness components of neuroticism relate positively to hedonism (or seeking pleasure without regards to the long-term and a disregard for right and wrong) and negatively relate to benevolence, tradition, and conformity (Roccas, Sagiv, Schwartz, & Knafo, 2002).

The 45-year-long study from researchers Soldz and Vaillant showed that neuroticism, over the course of the study, was negatively correlated with smoking cessation and healthy adjustment to life and correlated positively with drug usage, alcohol abuse, and mental health issues (1999).

Neuroticism was found to correlate somewhat negatively with agreeableness and conscientiousness, in addition to a weak, negative relationship with extroversion and openness to experience (Ones, Viswevaran, & Reiss, 1996).

Overall, high neuroticism is related to added difficulties in life, including addiction, poor job performance, and unhealthy adjustment to life’s changes. Scoring high on neuroticism is not an immediate sentence to a miserable life, but those in this group would benefit from investing in improvements to their self-confidence, building resources to draw on in times of difficulty, and avoiding any substances with addictive properties.

Big Five Inventory

This inventory was developed by Goldberg in 1993 to measure the five dimensions of the Big Five personality framework. It contains 44 items and measures each factor through its corresponding facets:

- Extroversion;

- Gregariousness;

- Assertiveness;

- Excitement-seeking;

- Positive emotions ;

- Agreeableness;

- Straightforwardness;

- Compliance;

- Tender-mindedness;

- Conscientiousness;

- Competence;

- Dutifulness;

- Achievement striving;

- Self-discipline;

- Deliberation;

- Neuroticism;

- Angry hostility;

- Depression;

- Self-consciousness;

- Impulsiveness;

- Vulnerability;

- Openness to experience;

- Aesthetics;

The responses to items concerning these facets are combined and summarized to produce a score on each factor. This inventory has been widely used in psychology research and is still quite popular, although the Revised NEO Personality Inventory has also gained much attention in recent years.

To learn more about the BFI or to see the items, click here to find a PDF with more information.

Revised NEO Personality Inventory

The original NEO Personality Inventory was created by personality researchers Paul Costa Jr. and Robert McCrae in 1978. It was later revised several times to keep up with advancements (in 1990, 2005, and 2010). Initially, the NEO Personality Inventory was named for the three main domains as the researchers understood them at the time: neuroticism, extroversion, and openness.

This scale is also based on the six facets of each factor and includes 240 items rated on a 5-point scale. For a shorter scale, Costa and McCrae also offer the NEO Five-Factor Inventory, which contains only 60 items and measures just the overall domains instead of all facets.

The NEO PI-R requires only a 6th-grade reading level and can be self-administered without a scoring professional.

Access to the NEO PI-R isn’t as widely available as the BFI, so you will have to dig around to obtain it.

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

Personality is a complex topic of research in psychology, and it has a long history of shifting philosophies and theories. While it’s easy to conceptualize personality on a day-to-day level, conducting valid scientific research on personality can be much more complex.

The Big Five can help you to learn more about your own personality and where to focus your energy and attention. The first step in effectively leveraging your strengths is to learn what your strengths are.

Whether you use the Big Five Inventory, the NEO PI-R, or something else entirely, we hope you’re able to learn where you fall on the OCEAN spectrums.

What do you think about the OCEAN model? Do you think the traits it describes apply to your personality? Let us know in the comments below.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Strengths Exercises for free .

The most widely used Big Five personality test is the Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R), which contains a total of 240 questions (Costa & McCrae, 1992).

Yes, the Big Five personality test is generally considered to be reliable, with research indicating that the five dimensions of personality are consistent across different cultures and can reliably predict a range of behaviors and outcomes (Costa & McCrae, 2008).

A quick example of a few personality questions includes:

- Do you prefer spending time alone or with a large group of people?

- How often do you take risks or try new things?

- When faced with a problem, do you rely more on your intuition or your logical thinking?

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Personality. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/topics/personality/

- Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The big five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta‐analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44 (1), 1-26.

- Boyce, C. J., Wood, A. M., & Powdthavee, N. (2013). Is personality fixed? Personality changes as much as “variable” economic factors and more strongly predicts changes to life satisfaction. Social Indicators Research, 111, 287-305.

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI): Professional manual . Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (2008). The revised NEO personality inventory (NEO-PI-R). In G. J. Boyle, G. Matthews, & D. H. Saklofske (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of personality theory and assessment: Vol. 2 . Personality measurement and testing (pp. 179-198). Sage Publications.

- Douglas, H. E., Bore, M., & Munro, D. (2016). Openness and intellect: An analysis of the motivational constructs underlying two aspects of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 99 , 242-253.

- John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big-Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research (Vol. 2, pp. 102-138). New York: Guilford Press.

- Judge, T. A., Higgins, C. A., Thoresen, C. J., & Barrick, M. R. (1999). The Big Five personality traits, general mental ability, and career success across the life span. Personnel Psychology, 52 , 621-652.

- Judge, T. A., Erez, A., Bono, J. E., & Thoresen, C. J. (2002). Are measures of self-esteem, neuroticism, locus of control, and generalized self-efficacy indicators of a common core construct? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 693-710.

- Judge, T. A., & Ilies, R. (2002). Relationship of personality to performance motivation: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 797-807.

- Lebowitz, S. (2016a). The ‘Big 5’ personality traits could predict who will and won’t become a leader. Business Insider. Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com/big-five-personality-traits-predict-leadership-2016-12

- Lebowitz, S. (2016b). Scientists say your personality can be deconstructed into 5 basic traits. Business Insider. Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com/big-five-personality-traits-2016-12

- McLeod, S. (2007). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Simply Psychology. Retrieved from https://www.simplypsychology.org/maslow.html

- Ones, D. S., Viswesvaran, C., & Reiss, A. D. (1996). Role of social desirability in personality testing for personnel selection: The red herring. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81 , 660-679.

- Ozer, D. J., & Benet-Martinez, V. (2006). Personality and the prediction of consequential outcomes. Annual Review of Psychology, 57 , 401-421.

- Revelle, W. (2013). Personality theory and research. Personality Project. Retrieved from https://www.personality-project.org/index.html

- Roccas, S., Sagiv, L., Schwartz, S. H., & Knafo, A. (2002). The Big Five personality factors and personal values. Personality and Social Psychology, 28, 789-801.

- Schaefer, P. S., Williams, C. C., Goodie, A. S., & Campbell, W. K. (2004). Overconfidence and the Big Five. Journal of Research in Personality, 38 , 473-480.

- Schmitt, D. P., Allik, J., McCrae, R. R., Benet-Martinez, V., Alcalay, L., Ault, L., …, & Zupanèiè, A. (2007). The geographic distribution of Big Five personality traits: Patterns and profiles of human self-description across 56 nations. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38 , 173-212.

- Schretlen, D. J., van der Hulst, E., Pearlson, G. D., & Gordon, B. (2010). A neuropsychological study of personality: Trait openness in relation to intelligence, fluency, and executive functioning. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 32, 1068-1073.

- Soldz, S., & Vaillant, G. E. (1999). The Big Five personality traits and the life course: A 45-year longitudinal study. Journal of Research in Personality, 33 , 208-232.

- Twomey, S. (2010, January). Phineas Gage: Neuroscience’s most famous patient. Smithsonian. Retrieved from http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/phineas-gage-neurosciences-most-famous-patient-11390067/

- Verduyn, P., & Brans, K. (2012). The relationship between extroversion, neuroticism, and aspects of trait affect. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 664-669.

- Woods, S. A., Patterson, F. C., Koczwara, A., & Sofat, J. A. (2016). The value of being a conscientious learner: Examining the effects of the big five personality traits on self-reported learning from training. Journal of Workplace Learning, 28 , 424-434.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

To me the problem with the OCEAN model is that the Big Five have long lists of “positive” traits while the opposite has short “negative” traits. (See for example extroversion compared to introversion). I have noticed this in books on the topic as well. This seems biased to me as if some traits are preferred more than others.

This overview of the Big Five is the easiest to follow and comprehend for the not-so-psychology-educated psychology-interested person… Love it…

I agree with Mr. Bakker. This article leads me to questions I didn’t know I had! Thanks very much indeed.

There seem to be areas of the brain that become inactive, or drugged or damaged. It seems to me this topic is still trying to address mind/consciousness/soul? from a collection of factors that may intersect, have unions that are not exclusive. (not well expressed, sorry).

What part of the big five or the big five inventory can’t be attributed to genetics? How much of our personalities are inherited?

Interesting question! Research on the heritability of Big Five traits has shown genetic influence varying from 41-61% for each respective facet. This article outlines these findings nicely. If you are interested to read about the role of genetics in the manifestation of Big Five traits and the Dark Triad traits, then this article is also quite interesting.

I hope this helps!

Kind regards, -Caroline | Community Manager

After nearly twenty years of reading blogs, this is the only one I continue to read (and I do it without fail each and every day).

What a wonderful experience it has been to “get to know” about this platform and all of the excellent stuff that you guys are providing.

You all are such a ray of sunshine in this world; I always come here to read your arguments, and after I do, I can’t help but grin because not many people have taken the time to write something that is interesting to the people who are reading it.

Thank you for all the love, positive thoughts, and best wishes that are being sent your way.

After nearly twenty years of reading blogs, this is the only one I continue to read (and I do it without fail each and every day). What a wonderful experience it has been to “get to know” about this platform and all of the excellent stuff that you guys are providing. Thank you. Weldon and I want to encourage you to keep up the fantastic effort.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Jungian Psychology: Unraveling the Unconscious Mind

Alongside Sigmund Freud, the Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961) is one of the most important innovators in the field of modern depth [...]

12 Jungian Archetypes: The Foundation of Personality

In the vast tapestry of human existence, woven with the threads of individual experiences and collective consciousness, lies a profound understanding of the human psyche. [...]

Personality Assessments: 10 Best Inventories, Tests, & Methods

Do you coach or manage a group of vastly different people? Perhaps they respond differently to news, or react differently to your feedback. They voice [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (30)

- Positive Communication (22)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (19)

- Positive Parenting (16)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (18)

- Relationships (43)

- Resilience & Coping (38)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

Big Five Personality Traits: The 5-Factor Model of Personality

Annabelle G.Y. Lim

Psychology Graduate

BA (Hons), Psychology, Harvard University

Annabelle G.Y. Lim is a graduate in psychology from Harvard University. She has served as a research assistant at the Harvard Adolescent Stress & Development Lab.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

The Big Five Personality Traits, also known as OCEAN or CANOE, are a psychological model that describes five broad dimensions of personality: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. These traits are believed to be relatively stable throughout an individual’s lifetime.

- Conscientiousness – impulsive, disorganized vs. disciplined, careful

- Agreeableness – suspicious, uncooperative vs. trusting, helpful

- Neuroticism – calm, confident vs. anxious, pessimistic

- Openness to Experience – prefers routine, practical vs. imaginative, spontaneous

- Extraversion – reserved, thoughtful vs. sociable, fun-loving

The Big Five remain relatively stable throughout most of one’s lifetime. They are influenced significantly by genes and the environment, with an estimated heritability of 50%. They also predict certain important life outcomes such as education and health.

Each trait represents a continuum. Individuals can fall anywhere on the continuum for each trait.

Unlike other trait theories that sort individuals into binary categories (i.e. introvert or extrovert ), the Big Five Model asserts that each personality trait is a spectrum.

Therefore, individuals are ranked on a scale between the two extreme ends of five broad dimensions:

For instance, when measuring Extraversion, one would not be classified as purely extroverted or introverted, but placed on a scale determining their level of extraversion.

By ranking individuals on each of these traits, it is possible to effectively measure individual differences in personality.

Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness describes a person’s ability to regulate impulse control to engage in goal-directed behaviors (Grohol, 2019). It measures elements such as control, inhibition, and persistence of behavior.

Facets of conscientiousness include the following (John & Srivastava, 1999):

- Dutifulness

- Achievement striving

- Self-disciplined

- Deliberation

- Incompetent

- Disorganized

- Procrastinates

- Indiscipline

Conscientiousness vs. Lack of Direction

Those who score high on conscientiousness can be described as organized, disciplined, detail-oriented, thoughtful, and careful. They also have good impulse control, which allows them to complete tasks and achieve goals.

Those who score low on conscientiousness may struggle with impulse control, leading to difficulty in completing tasks and fulfilling goals.

They tend to be more disorganized and may dislike too much structure. They may also engage in more impulsive and careless behavior.

Agreeableness

Agreeableness refers to how people tend to treat relationships with others. Unlike extraversion which consists of the pursuit of relationships, agreeableness focuses on people’s orientation and interactions with others (Ackerman, 2017).

Facets of agreeableness include the following (John & Srivastava, 1999):

- Trust (forgiving)

- Straightforwardness

- Altruism (enjoys helping)

- Sympathetic

- Insults and belittles others

- Unsympathetic

- Doesn’t care about how other people feel

Agreeableness vs. Antagonism

Those high in agreeableness can be described as soft-hearted, trusting, and well-liked. They are sensitive to the needs of others and are helpful and cooperative. People regard them as trustworthy and altruistic.

Those low in agreeableness may be perceived as suspicious, manipulative, and uncooperative. They may be antagonistic when interacting with others, making them less likely to be well-liked and trusted.

Extraversion

Extraversion reflects the tendency and intensity to which someone seeks interaction with their environment, particularly socially. It encompasses the comfort and assertiveness levels of people in social situations.

Additionally, it also reflects the sources from which someone draws energy.

Facets of extraversion include the following (John & Srivastava, 1999):

- Energized by social interaction

- Excitement-seeking

- Enjoys being the center of attention

- Prefers solitude

- Fatigued by too much social interaction

- Dislikes being the center of attention

Extraversion vs. Introversion

Those high on extraversion are generally assertive, sociable, fun-loving, and outgoing. They thrive in social situations and feel comfortable voicing their opinions. They tend to gain energy and become excited from being around others.

Those who score low in extraversion are often referred to as introverts . These people tend to be more reserved and quieter. They prefer listening to others rather than needing to be heard.

Introverts often need periods of solitude in order to regain energy as attending social events can be very tiring for them.

Of importance to note is that introverts do not necessarily dislike social events, but instead find them tiring.

Openness to Experience

Openness to experience refers to one’s willingness to try new things as well as engage in imaginative and intellectual activities. It includes the ability to “think outside of the box.”

Facets of openness include the following (John & Srivastava, 1999):

- Imaginative

- Open to trying new things

- Unconventional

- Predictable

- Not very imaginative

- Dislikes change

- Prefer routine

- Traditional

Openness vs. Closedness to Experience

Those who score high on openness to experience are perceived as creative and artistic. They prefer variety and value independence. They are curious about their surroundings and enjoy traveling and learning new things.

People who score low on openness to experience prefer routine. They are uncomfortable with change and trying new things, so they prefer the familiar over the unknown.

As they are practical people, they often find it difficult to think creatively or abstractly.

Neuroticism

Neuroticism describes the overall emotional stability of an individual through how they perceive the world. It takes into account how likely a person is to interpret events as threatening or difficult.

It also includes one’s propensity to experience negative emotions.

Facets of neuroticism include the following (John & Srivastava, 1999):

- Angry hostility (irritable)

- Experiences a lot of stress

- Self-consciousness (shy)

- Vulnerability

- Experiences dramatic shifts in mood

- Doesn”t worry much

- Emotionally stable

- Rarely feels sad or depressed

Neuroticism vs. Emotional Stability

Those who score high on neuroticism often feel anxious, insecure and self-pitying. They are often perceived as moody and irritable. They are prone to excessive sadness and low self-esteem.

Those who score low on neuroticism are more likely to calm, secure and self-satisfied. They are less likely to be perceived as anxious or moody. They are more likely to have high self-esteem and remain resilient.

Behavioral Outcomes

Relationships.

In marriages where one partner scores lower than the other on agreeableness, stability, and openness, there is likely to be marital dissatisfaction (Myers, 2011).

Neuroticism seems to be a risk factor for many health problems, including depression, schizophrenia, diabetes, asthma, irritable bowel syndrome, and heart disease (Lahey, 2009).

People high in neuroticism are particularly vulnerable to mood disorders such as depression . Low agreeableness has also been linked to higher chances of health problems (John & Srivastava, 1999).

There is evidence to suggest that conscientiousness is a protective factor against health diseases. People who score high in conscientiousness have been observed to have better health outcomes and longevity (John & Srivastava, 1999).

Researchers believe that such is due to conscientious people having regular and well-structured lives, as well as the impulse control to follow diets, treatment plans, etc.

A high score on conscientiousness predicts better high school and university grades (Myers, 2011). Contrarily, low agreeableness and low conscientiousness predict juvenile delinquency (John & Srivastava, 1999).

Conscientiousness is the strongest predictor of all five traits for job performance (John & Srivastava, 1999). A high score of conscientiousness has been shown to relate to high work performance across all dimensions.

The other traits have been shown to predict more specific aspects of job performance. For instance, agreeableness and neuroticism predict better performance in jobs where teamwork is involved.

However, agreeableness is negatively related to individual proactivity. Openness to experience is positively related to individual proactivity but negatively related to team efficiency (Neal et al., 2012).

Extraversion is a predictor of leadership, as well as success in sales and management positions (John & Srivastava, 1999).

Media Preference

Manolika (2023) examined how the Big Five personality traits relate to preferences for different genres of movies and books. The study surveyed 386 university students on their Big Five traits and preferences for 21 movie and 27 book types.

Results showed openness to experience predicted liking complex movies like documentaries and unconventional books like philosophy. This aligns with past research showing open people like cognitively challenging art (Swami & Furnham, 2019).

Conscientiousness predicted preferring informational books, while agreeableness predicted conventional genres like family movies and romance books.

Neuroticism only predicted preferring light books, not movies. Extraversion did not predict preferences, contrary to hypotheses.

Overall, the Big Five traits differentially predicted media preferences, suggesting people select entertainment that satisfies psychological needs and reflects aspects of their personalities (Rentfrow et al., 2011).

Open people prefer complex stimulation, conscientious people prefer practical content, agreeable people prefer conventional genres, and neurotic people use light books for mood regulation. Extraversion may relate more to social motivations for media use.

Critical Evaluation

Descriptor rather than a theory.

The Big Five was developed to organize personality traits rather than as a comprehensive theory of personality. Therefore, it is more descriptive than explanatory and does not fully account for differences between individuals (John & Srivastava, 1999). It also does not sufficiently provide a causal reason for human behavior.

Cross-Cultural Validity

Although the Big Five has been tested in many countries and its existence is generally supported by findings (McCrae, 2002), there have been some studies that do not support its model. Most previous studies have tested the presence of the Big Five in urbanized, literate populations.

A study by Gurven et al. (2013) was the first to test the validity of the Big Five model in a largely illiterate, indigenous population in Bolivia. They administered a 44-item Big Five Inventory but found that the participants did not sort the items in consistency with the Big Five traits.

More research on illiterate and non-industrialized populations is needed to clarify such discrepancies.

Gender Differences

Differences in the Big Five personality traits between genders have been observed, but these differences are small compared to differences between individuals within the same gender.

Costa et al. (2001) gathered data from over 23,000 men and women in 26 countries. They found that “gender differences are modest in magnitude, consistent with gender stereotypes, and replicable across cultures” (p. 328). Women reported themselves to be higher in Neuroticism, Agreeableness, Warmth (a facet of Extraversion), and Openness to Feelings compared to men. Men reported themselves to be higher in Assertiveness (a facet of Extraversion) and Openness to Ideas.

Another interesting finding was that bigger gender differences were reported in Western, industrialized countries. Researchers proposed that the most plausible reason for this finding was attribution processes.

They surmised that the actions of women in individualistic countries would be more likely to be attributed to their personality, whereas actions of women in collectivistic countries would be more likely to be attributed to their compliance with gender role norms.

Factors that Influence the Big 5

Like with all theories of personality , the Big Five is influenced by both nature and nurture . Twin studies have found that the heritability (the amount of variance that can be attributed to genes) of the Big Five traits is 40-60%.

Jang et al. (1996) conducted a study with 123 pairs of identical twins and 127 pairs of fraternal twins. They estimated the heritability of conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, openness to experience, and extraversion to be 44%, 41%, 41%, 61%, and 53%, respectively. This finding was similar to the findings of another study, where the heritability of conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, openness to experience and extraversion were estimated to be 49%, 48%, 49%, 48%, and 50%, respectively (Jang et al., 1998).

Such twin studies demonstrate that the Big Five personality traits are significantly influenced by genes and that all five traits are equally heritable. Heritability for males and females does not seem to differ significantly (Leohlin et al., 1998).

Studies from different countries also support the idea of a strong genetic basis for the Big Five personality traits (Riemann et al., 1997; Yamagata et al., 2006).

Roehrick et al. (2023) examined how Big Five traits (extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, openness) and context relate to smartphone use. The study used surveys, experience sampling, and smartphone sensing to track college students’ personality, context, and hourly smartphone behaviors over one week.

They found extraverts used their phones more frequently once checked, but conscientious people were less likely to use their phone and used them for shorter durations. Smartphones were used in public, with weaker social ties, and during class/work activities. They were used less with close ties. Perceived situations didn’t relate much to use.

Most variability in use was within-person, suggesting context matters more than personality for smartphone behaviors. Comparisons showed context-explained duration of use over traits and demographics, but not frequency.

The key implication is that both personality and context are important to understanding digital behavior. Extraversion and conscientiousness were the most relevant of the Big Five for smartphone use versus non-use and degree of use. Contextual factors like location, social ties, and activities provided additional explanatory power, especially for the duration of smartphone use.

Stability of the Traits

People’s scores of the Big Five remain relatively stable for most of their life with some slight changes from childhood to adulthood. A study by Soto & John (2012) attempted to track the developmental trends of the Big Five traits.

They found that overall agreeableness and conscientiousness increased with age. There was no significant trend for extraversion overall although gregariousness decreased and assertiveness increased.

Openness to experience and neuroticism decreased slightly from adolescence to middle adulthood. The researchers concluded that there were more significant trends in specific facets (i.e. adventurousness and depression) rather than in the Big Five traits overall.

History and Background

The Big Five model resulted from the contributions of many independent researchers. Gordon Allport and Henry Odbert first formed a list of 4,500 terms relating to personality traits in 1936 (Vinney, 2018). Their work provided the foundation for other psychologists to begin determining the basic dimensions of personality.

In the 1940s, Raymond Cattell and his colleagues used factor analysis (a statistical method) to narrow down Allport’s list to sixteen traits.

However, numerous psychologists examined Cattell’s list and found that it could be further reduced to five traits. Among these psychologists were Donald Fiske, Norman, Smith, Goldberg, and McCrae & Costa (Cherry, 2019).

In particular, Lewis Goldberg advocated heavily for five primary factors of personality (Ackerman, 2017). His work was expanded upon by McCrae & Costa, who confirmed the model’s validity and provided the model used today: conscientiousness, agreeableness, neuroticism, openness to experience, and extraversion.

The model became known as the “Big Five” and has seen received much attention. It has been researched across many populations and cultures and continues to be the most widely accepted theory of personality today.

Each of the Big Five personality traits represents extremely broad categories which cover many personality-related terms. Each trait encompasses a multitude of other facets.

For example, the trait of Extraversion is a category that contains labels such as Gregariousness (sociable), Assertiveness (forceful), Activity (energetic), Excitement-seeking (adventurous), Positive emotions (enthusiastic), and Warmth (outgoing) (John & Srivastava, 1999).

Therefore, the Big Five, while not completely exhaustive, cover virtually all personality-related terms.

Another important aspect of the Big Five Model is its approach to measuring personality. It focuses on conceptualizing traits as a spectrum rather than black-and-white categories (see Figure 1). It recognizes that most individuals are not on the polar ends of the spectrum but rather somewhere in between.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is 5 really the magic number.

A common criticism of the Big Five is that each trait is too broad. Although the Big Five is useful in terms of providing a rough overview of personality, more specific traits are required to be of use for predicting outcomes (John & Srivastava, 1999).

There is also an argument from psychologists that more than five traits are required to encompass the entirety of personality.

A new model, HEXACO, was developed by Kibeom Lee and Michael Ashton, and expands upon the Big Five Model. HEXACO retains the original traits from the Big Five Model but contains one additional trait: Honesty-Humility, which they describe as the extent to which one places others’ interests above their own.

What are the differences between the Big Five and the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator?

The Big Five personality traits and the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) are both popular models used to understand personality. However, they differ in several ways.

The Big Five traits represent five broad dimensions of personality. Each trait is measured along a continuum, and individuals can fall anywhere along that spectrum.

In contrast, the MBTI categorizes individuals into one of 16 personality types based on their preferences for four dichotomies: extraversion/introversion, sensing/intuition, thinking/feeling, and judging/perceiving. This model assumes that people are either one type or another rather than being on a continuum.

Overall, while both models aim to describe and categorize personality, the Big Five is thought to have more empirical research and more scientific support, while the MBTI is more of a theory and often lacks strong empirical evidence.

Is it possible to improve certain Big Five traits through therapy or other interventions?

It can be possible to improve certain Big Five traits through therapy or other interventions.

For example, individuals who score low in conscientiousness may benefit from therapy that focuses on developing planning, organizational, and time-management skills. Those with high neuroticism may benefit from cognitive-behavioral therapy, which helps individuals manage negative thoughts and emotions.

Additionally, therapy such as mindfulness-based interventions may increase scores in traits such as openness and agreeableness. However, the extent to which these interventions can change personality traits long-term is still a topic of debate among psychologists.

Is it possible to have a high score in more than one Big Five trait?

Yes, it is possible to have a high score in more than one Big Five trait. Each trait is independent of the others, meaning that an individual can score high on openness, extraversion, and conscientiousness, for example, all at the same time.

Similarly, an individual can also score low on one trait and high on another. The Big Five traits are measured along a continuum, so individuals can fall anywhere along that spectrum for each trait.

Therefore, it is common for individuals to have a unique combination of high and low scores across the Big Five personality traits.

Ackerman, C. (2017, June 23). Big Five Personality Traits: The OCEAN Model Explained . PositivePsychology.com. https://positivepsychology.com/big-five-personality-theory

Cherry, K. (2019, October 14). What Are the Big 5 Personality Traits? Verywell Mind . Retrieved 12 June 2020, from https://www.verywellmind.com/the-big-five-personality-dimensions-2795422

Costa, P., Terracciano, A., & McCrae, R. (2001). Gender Differences in Personality Traits Across Cultures: Robust and Surprising Findings . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81 (2), 322-331. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.81.2.322

Fiske, D. W. (1949). Consistency of the factorial structures of personality ratings from different sources. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 44 (3), 329-344. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0057198

Grohol, J. M. (2019, May 30). The Big Five Personality Traits . PsychCentral. Retrieved 10 June 2020, from https://psychcentral.com/lib/the-big-five-personality-traits

Gurven, M., von Rueden, C., Massenkoff, M., Kaplan, H., & Lero Vie, M. (2013). How universal is the Big Five? Testing the five-factor model of personality variation among forager-farmers in the Bolivian Amazon . Journal of personality and social psychology, 104 (2), 354–370. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030841

Jang, K. L., Livesley, W. J., & Vemon, P. A. (1996). Heritability of the Big Five Personality Dimensions and Their Facets: A Twin Study . Journal of Personality, 64 (3), 577–592. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1996.tb00522.x

Jang, K. L., McCrae, R. R., Angleitner, A., Riemann, R., & Livesley, W. J. (1998). Heritability of facet-level traits in a cross-cultural twin sample: Support for a hierarchical model of personality. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74 (6), 1556–1565.

John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big-Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (Vol. 2, pp. 102–138). New York: Guilford Press.

Lahey B. B. (2009). Public health significance of neuroticism. The American psychologist, 64 (4), 241–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015309

Loehlin, J. C., McCrae, R. R., Costa, P. T., & John, O. P. (1998). Heritabilities of Common and Measure-Specific Components of the Big Five Personality Factors . Journal of Research in Personality, 32 (4), 431–453. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1998.2225

Manolika, M. (2023). The Big Five and beyond: Which personality traits do predict movie and reading preferences? Psychology of Popular Media, 12 (2), 197–206

McCrae, R. R. (2002). Cross-Cultural Research on the Five-Factor Model of Personality . Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 4 (4). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1038

Myers, David G. (2011). Psychology (10th ed.) . Worth Publishers.

Neal, A., Yeo, G., Koy, A., & Xiao, T. (2012). Predicting the form and direction of work role performance from the Big 5 model of personality traits . Journal of Organizational Behavior, 33 (2), 175–192. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.742

Riemann, R., Angleitner, A., & Strelau, J. (1997). Genetic and Environmental Influences on Personality: A Study of Twins Reared Together Using the Self‐ and Peer Report NEO‐FFI Scales . Journal of Personality, 65 (3), 449-475.

Roehrick, K. C., Vaid, S. S., & Harari, G. M. (2023). Situating smartphones in daily life: Big Five traits and contexts associated with young adults’ smartphone use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 125 (5), 1096–1118.

Soto, C. J., & John, O. P. (2012). Development of Big Five Domains and Facets in Adulthood: Mean-Level Age Trends and Broadly Versus Narrowly Acting Mechanism . Journal of Personality, 80 (4), 881–914. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2011.00752.x

Vinney, C. (2018, September 27). Understanding the Big Five Personality Traits . ThoughtCo. Retrieved 12 June 2020, from https://www.thoughtco.com/big-five-personality-traits-4176097

Yamagata, S., Suzuki, A., Ando, J., Ono, Y., Kijima, N., Yoshimura, K., . . . Jang, K. (2006). Is the Genetic Structure of Human Personality Universal? A Cross-Cultural Twin Study From North America, Europe, and Asia. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90 (6), 987-998. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.6.987

Keep Learning

- Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI)

- McCrae, R. R., & Terracciano, A. (2005). Universal features of personality traits from the observer’s perspective: data from 50 cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88 (3), 547.

- Cobb-Clark, DA & Schurer, S. The stability of big-five personality traits. Economics Letters. 2012; 115 (2): 11–15.

- Marsh, H. W., Nagengast, B., & Morin, A. J. (2013). Measurement invariance of big-five factors over the life span: ESEM tests of gender, age, plasticity, maturity, and la dolce vita effects. Developmental psychology, 49 (6), 1194.

- Power RA, Pluess M. Heritability estimates of the Big Five personality traits based on common genetic variants. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5 :e604.

- Personality Theories Book Chapter

- The Cambridge Handbook of Personality Psychology

Related Articles

Personality

Exploring the MMPI-3 in a Transgender and Gender Diverse Sample

Are Developmental Trajectories of Personality and Socioeconomic Factors Related to Later Cognitive Function

Do Life Events Lead to Enduring Changes in Adult Attachment Styles?

Thin-Slicing Judgments In Psychology

Authoritarian Personality

Soft Determinism In Psychology

Advertisement

What are the big 5 personality traits inside psychology's core personality system.

An individual's "personality" refers to their patterns of behaviors, thoughts, and feelings. To help capture the seemingly infinite number of personalities that appear across humankind, researchers have developed models for measuring their most common manifestations.

Many psychologists consider the so-called Big Five personality traits the most reputable. This model states that personality comes down to five core factors: openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism.

We asked psychology experts to help us unpack the Big 5 personality traits and the ways in which mental health professionals use them.

What are the Big Five personality traits?

The Big Five personality traits are openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. These five fundamental traits attempt to summarize the human personality on a comparative scale.

"Personality is defined as someone's usual patterns of behaviors, feelings, and thoughts. While these usual patterns are complex, there are some personality traits that organize our understanding of someone's personality," explains licensed clinical psychologist Ernesto Lira de la Rosa, Ph.D. , of the Hope for Depression Research Foundation . That's where personality frameworks like the Big Five, also known as the Five Factor model , come in.

According to the Big Five theory of personality, all human personalities are composed of these five core personality dimensions, and any individual's personality boils down to where they fall on each of these five scales. Although not without its criticisms, decades of research have validated this theory.

The Big Five personality framework was first developed in 1949 by personality psychologist D.W. Fiske. Later, other scientists, including Warren T. Norman, Robert McCrae & Paul Costa, Gene M. Smith, and Lewis R. Goldberg, further developed Fiske's theories and research.

As with any personality test, there is controversy over the model itself and how it is best applied, says psychotherapist Lee Phillips, Ed.D., LCSW, CST . That said, today the Big Five personality traits are widely accepted as an accurate way of understanding human personality among most psychologists in the United States and in the broader Western world, supported by ample research.

And as one 2020 paper in The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences notes, "The five factors have provided a framework for understanding psychopathology. Neuroscience has identified neural correlates of the five factors, and cross-cultural research has underscored how people across the globe are both similar and different."

Below is a breakdown of each of the Big Five personality traits:

Openness

Openness to experience represents intellectual curiosity, creative imagination, and valuable insights. This trait includes thinking outside the box and being willing to learn new things.

According to Lira de la Rosa, "People who score high on openness tend to enjoy trying new things, playing with complex ideas, and considering alternative perspectives. Those who score lower on openness may dislike change, trying new things, and dislike abstract concepts."

Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness indicates organization, productivity, responsibility, and impulse control. Highly conscientious people have goal-oriented behaviors. Phillips says, "Conscientiousness measures the organizational skills of the individual. For example, it looks at how careful, deliberate, and self-disciplined they are. Conscientiousness looks at the foretelling of employee productivity."

According to Lira de la Rosa, those who score high on conscientiousness may spend more time preparing for things. They pay close attention to detail and enjoy a set schedule. "However, those who score low on conscientiousness may dislike structure and schedules and may procrastinate on important tasks," he says.

Extroversion

Extroversion looks at how sociable and outgoing a person is, and where they feel most energized. High scores indicate a person energized by the company of others and excited by being the center of attention. Low scores indicate a more reserved person who enjoys solitude.

Introverts don't necessarily dislike social gatherings; however, they may get fatigued by them and require time alone to regain their energy.

Agreeableness

Agreeableness is aligned with attributes like kindness, affection, and trust. People with high scores are interested in others. They are emphatic and enjoy contributing to others' happiness.

"Those who score high may feel empathy and concern for others, enjoy helping others and contributing to their happiness. They love to assist those who are in need. In contrast, those who score low on agreeableness may take little interest in others, insult or belittle others, and have little interest in other people's problems," says Lira de la Rosa.

Neuroticism

Neuroticism indicates emotional instability. It often refers to sadness and moodiness .

Phillips explains that "high scores indicate the person is anxious, irritable, they are capable of anger outbursts, and they can have dramatic shifts in their mood. Low scores indicate the person does not worry as much, they are calm and emotionally stable, and they rarely feel sad or depressed."

Why are the Big Five personality traits so important?

The Big Five personality traits model helps people identify on a spectrum, recognizing that all people exhibit some of these traits at some point in their lives.

"These traits are important because they are useful in understanding our social interactions with others. They are also helpful in increasing our self-awareness and how our personality traits may impact how others perceive or experience us," Lira de la Rosa tells mbg.

The Big Five model has evolved with time, research, and technology. These days, it's regularly applied in social, academic, and professional contexts.

The Big Five personality traits are foundational to personality tests that have become popular in dating, family, and work. Drawing from the same scientific research that generated the Big Five, the Myers-Briggs (MBTI) , Likability Test , and the Difficult Person Test are related personality assessments meant to understand how an individual's traits manifest in relationships with others. Tools and tests like these are often used to build relationships, romantic or professional.

In the field of organizational behavior, tests based on the Big Five personality traits are often used in employee assessment tests, offering rubrics to understand employee character and to guide teams composed of diverse individuals.

Psychology and research.

The Big Five model of personality has been studied by psychologists over the course of nearly a century, starting with D.W. Fiske's research in 1949.

Gordon Allport, an American psychologist sometimes described as a founder of the field of personality psychology, published in the 1920s about what he termed "cardinal traits," core characteristics thought to define a person's personality. His research developed a lexicon of over 4,500 vocabulary words to describe personality traits. Then in 1949, through a study of clinical trainees, Fiske attempted to find consistent structural factors of personalities 1 . He identified a core group of four similar factors, with three distinct levels of behavioral ratings.

As the field of psychology developed, personality research became more refined and competing, but related frameworks developed—some with as many as 16 factors and others with as few as four. But, somehow the number five kept coming up. Robert Costa and Paul McCrae developed the so-called Five Factor Model in 1987, and Lewis Goldberg developed the " Big Five Model " in 1993, both using the same core personality factors: openness, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism. Since then, these Big Five personality traits have been studied and validated time and time again by many researchers over decades.

Some of the most interesting recent research suggests that biological and environmental factors play a role in personality development. For example, a 2015 study of the personalities of twins 2 suggests that both nature and nurture affect the development of each of the Big Five personality traits. In that study, 127 pairs of fraternal twins and 123 pairs of identical twins were put to the Big Five test. The findings showed the heritability of openness and neuroticism, and subsequent research has been done to further explore the genetic basis for some of the other traits.

There is also some valid criticism of the Big Five personality traits. "In particular, most of the research on personality is done with people from western, educated, industrialized, rich, and democratic countries," explains Lira de la Rosa. "As such, the Big Five personality traits may not capture personality traits across cultures." He says that research shows that some of the Big Five personality traits are not observed as often in some other cultures.

Phillips also adds that critics ask, "How can one test determine a person's personality?" After all, personalities may shift over time. And it's the mix of traits—not each one individually—that defines our personalities. So, tests like these—when not taken under the supervision of a trained professional—can sometimes be used to justify ill-conceived or overly simplified conclusions about people's characters.