<strong data-cart-timer="" role="text"></strong>

- Visual Arts

- African-American History

Norman Rockwell + The Problem We All Live With Learn why a controversial painting became a symbol of the American civil rights movement

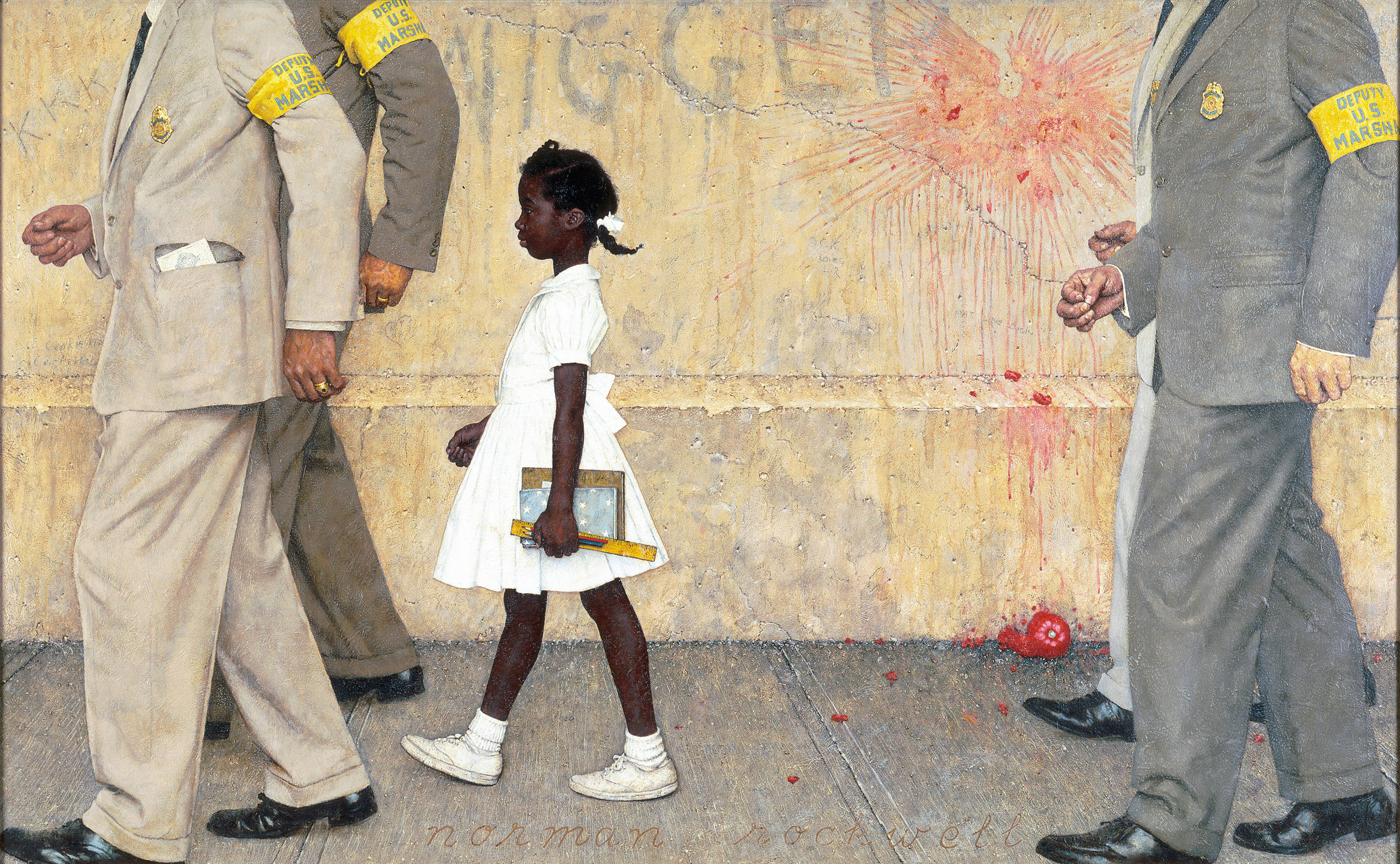

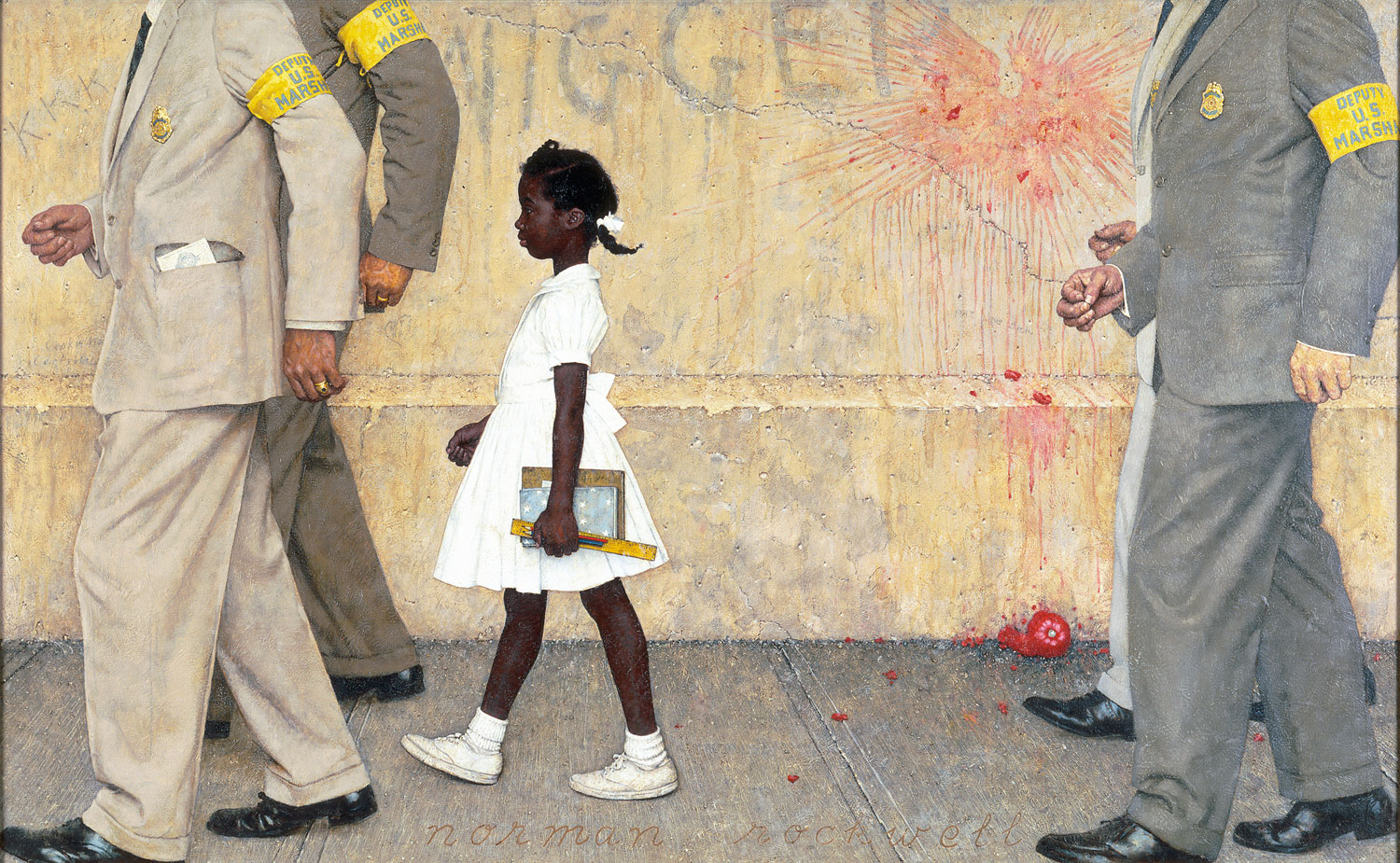

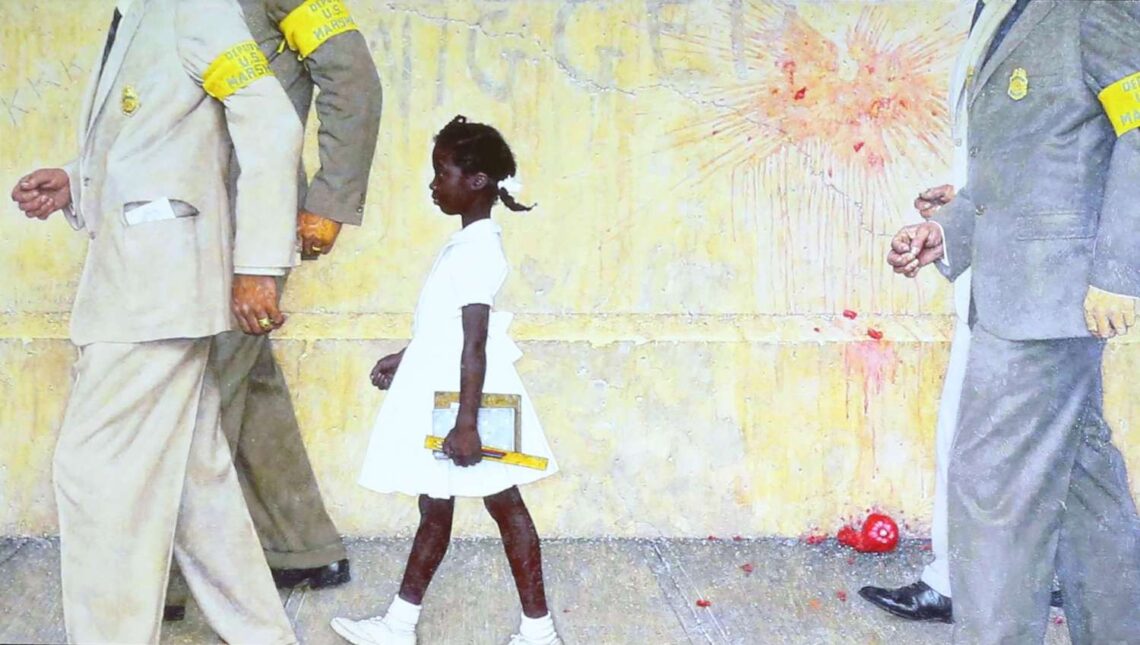

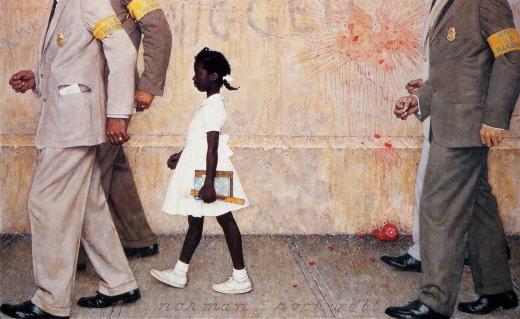

Norman Rockwell, The Problem We All Live With , 1963, oil on canvas, 36 x 58 inches. Illustration for LOOK , January 14, 1964. Norman Rockwell Museum Collections. ©NRELC, Niles, IL.

Lesson Content

Ruby and racism.

Imagine that you are six years old and it’s your first day in a new school. You are wearing a special outfit. You have your notebook, your pencils. You are excited, but a little nervous, too. Official-looking men in suits are there to escort you to the building. A wild, screaming crowd is gathered outside. Could it be a parade? Your teacher greets you warmly, but where are your classmates? Why are you the only student in the room? Why is there no one to eat lunch with you or to play with you on the playground? You are little and confused, but your mom has told you to behave, so you are brave—you don’t cry.

This is what actually happened to Ruby Bridges on her first day at William Franz Elementary School in New Orleans on November 14, 1960. Ruby was the first African American child to attend the school after a federal court ordered the New Orleans school system to integrate. The public outcry was so great that white parents withdrew their children from school so they would not have to sit with a Black girl. Ruby spent an entire year in a classroom by herself.

Artist and magazine illustrator Norman Rockwell is known for his idyllic images of American life in the twentieth century. But his work had a new sense of purpose in 1960s when he was hired by LOOK magazine. There, he produced his famous painting The Problem We All Live With , a visual commentary on segregation and the problem of racism in America. The painting depicts Ruby’s courageous walk to school on that November day. She dutifully follows faceless men—the yellow armbands reveal them to be federal marshals—past a wall smeared with racist graffiti and the juice of a thrown tomato. The canvas is arranged so that the viewer is at Ruby’s height, seeing the scene from her perspective.

Rockwell’s painting, created a few years after Ruby made her fateful entrance at school, was produced at the height of the Civil Rights Movement. It is now considered a symbol of that struggle. Bridges never met Rockwell, but as an adult, she came to admire his decision to tell her story: “Here was a man that had been doing lots of work, painting family images, and all of a sudden decided this is what I’m going to do…it’s wrong, and I’m going to say that it’s wrong…the mere fact that [Norman Rockwell] had enough courage to step up to the plate and say I’m going to make a statement, and he did it in a very powerful way…even though I had not had an opportunity to meet him, I commend him for that.”

Ruby’s walk to school was part of a larger history dating back to the Civil War. Despite Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation and the passage of an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that abolished slavery, African Americans were never truly free. By the late 1800s, “Jim Crow” laws in the Southern states prevented Black people from sharing public accommodations with white people, such as train cars, bathrooms, swimming pools, and schools.

This began to change in the 1950s when the National Association of Colored People (NAACP) challenged school segregation in the courts, and NAACP lawyer Thurgood Marshall argued the now-famous Brown v. Board of Education case before the Supreme Court. In 1954, the Court handed down its landmark decision: school segregation was unconstitutional because it violated the 14th Amendment, which guarantees all citizens—of all races—“equal protection under the law.”

But the South was slow to comply with the ruling, and it looked like Black civilians would have to force the issue. When nine students in Little Rock, Arkansas, decided to integrate Central High School in 1957, they were threatened by angry mobs, prompting President Dwight Eisenhower to call in U.S. paratroopers to escort the teenagers safely to school. By 1960, New Orleans was still fighting integration in its schools. They lost their case, allowing Ruby to break a long-standing barrier for herself as well as future generations.

Norman Rockwell

For many decades Rockwell’s illustrations appeared on the covers of the leading magazines of his day, including Saturday Evening Post , Leslie’s Weekly , Life , and LOOK . During World War II, he painted the Four Freedoms series, inspired by a speech made by President Franklin Roosevelt. He is best known for his sentimental images of American life, which evoke nostalgia for a time when life was slower, when families spent evenings around the dinner table sharing stories, and feeling safe and happy in their own homes.

Yet by the 1960s, the country had changed and so had the artist. Rockwell began to address more controversial themes such as poverty and racism. The Problem We All Live With , published in LOOK in 1964, took on the issue of school segregation. While some readers missed the Rockwell of happier times, others praised him for tackling serious issues. Together, his early idyllic and later realistic views of American life represent the artist’s personal portrait of our nation.

Rockwell died on November 8, 1978, at age of 84. He lived through two world wars, painted the portraits of several U.S. presidents, witnessed a man walk on the moon, and produced more than 4,000 works of art. He is an American icon. No wonder that, in 2011, President Barack Obama borrowed The Problem We All Live With for a special White House exhibition to commemorate the walk Ruby Bridges took to William Franz Elementary School 50 years earlier.

“Rockwell painted the American dream —better than anyone.”—Steven Spielberg

Lisa Resnick Tiffany A. Bryant

January 31, 2022

Related Resources

Collection visual arts.

Fasten your smock, get out your art supplies, and prepare to get your hands dirty. Examine the physics behind Alexander Calder’s mobiles, the symbolism in the botany rendered in renaissance paintings, and the careful patience used in weaving a wampum belt in this exploration of a wide range of arts.

Media What Makes a Portrait “Great”?

What makes a great portrait in the digital—or any—age? By looking at the works of Richard Avedon and Andy Warhol we learn that it's not enough to create just another pretty face.

- Drawing & Painting

- Photography

Kennedy Center Education Digital Learning

Eric Friedman Director, Digital Learning

Kenny Neal Manager, Digital Education Resources

Tiffany A. Bryant Manager, Operations and Audience Engagement

Joanna McKee Program Coordinator, Digital Learning

JoDee Scissors Content Specialist, Digital Learning

Connect with us!

Generous support for educational programs at the Kennedy Center is provided by the U.S. Department of Education. The content of these programs may have been developed under a grant from the U.S. Department of Education but does not necessarily represent the policy of the U.S. Department of Education. You should not assume endorsement by the federal government.

Gifts and grants to educational programs at the Kennedy Center are provided by A. James & Alice B. Clark Foundation; Annenberg Foundation; the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; Bank of America; Bender Foundation, Inc.; Capital One; Carter and Melissa Cafritz Trust; Carnegie Corporation of New York; DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities; Estée Lauder; Exelon; Flocabulary; Harman Family Foundation; The Hearst Foundations; the Herb Alpert Foundation; the Howard and Geraldine Polinger Family Foundation; William R. Kenan, Jr. Charitable Trust; the Kimsey Endowment; The King-White Family Foundation and Dr. J. Douglas White; Laird Norton Family Foundation; Little Kids Rock; Lois and Richard England Family Foundation; Dr. Gary Mather and Ms. Christina Co Mather; Dr. Gerald and Paula McNichols Foundation; The Morningstar Foundation;

The Morris and Gwendolyn Cafritz Foundation; Music Theatre International; Myra and Leura Younker Endowment Fund; the National Endowment for the Arts; Newman’s Own Foundation; Nordstrom; Park Foundation, Inc.; Paul M. Angell Family Foundation; The Irene Pollin Audience Development and Community Engagement Initiatives; Prince Charitable Trusts; Soundtrap; The Harold and Mimi Steinberg Charitable Trust; Rosemary Kennedy Education Fund; The Embassy of the United Arab Emirates; UnitedHealth Group; The Victory Foundation; The Volgenau Foundation; Volkswagen Group of America; Dennis & Phyllis Washington; and Wells Fargo. Additional support is provided by the National Committee for the Performing Arts.

Social perspectives and language used to describe diverse cultures, identities, experiences, and historical context or significance may have changed since this resource was produced. Kennedy Center Education is committed to reviewing and updating our content to address these changes. If you have specific feedback, recommendations, or concerns, please contact us at [email protected] .

By using this site, you agree to our Privacy Policy and Terms & Conditions which describe our use of cookies.

Reserve Tickets

Review cart.

You have 0 items in your cart.

Your cart is empty.

Keep Exploring Proceed to Cart & Checkout

Donate Today

Support the performing arts with your donation.

To join or renew as a Member, please visit our Membership page .

To make a donation in memory of someone, please visit our Memorial Donation page .

- Custom Other

Forgot password? Click here

The Problem We All Live With

Students will consider what freedoms they have as individuals. They will look at Norman Rockwell’s painting, The Problem We All Live With and analyze the illustration in relation to the civil rights movement. A class discussion will allow students discuss the painting’s concept and composition, and look closely at the objects and clues depicted in order to understand the significance of Ruby Bridges’ story in American history. Students will then design a piece of artwork commemorating a civil rights hero or addressing a problem they feel they are faced with today in America.

Four 30 minute class periods: Class 1- Presentation, and Think Sheet; 2 – Drafting, revision; 3-4 Work to complete illustration and class critique

- Enduring Understandings/ Essential Questions:

- Artwork plays a role in documenting the cultures of different times and places.

- Responses to art vary, and are sometimes dependent on knowledge and understanding of the time and place in which it was made.

- Viewers of artworks can infer information about the time, place, and culture in which a work of art was created.

- The elements of art are building blocks used to create a work of art, while the principles of design describe the way artists use these elements within their work. By analyzing the elements and principles, students may interpret the visual meaning and intention of the artist.

- How does The Problem We All Live With by Norman Rockwell relate to history?

- How were the elements and principles of design used to make this illustration successful?

- Describe the function and explore the meaning of specific art objects within our culture during this time.

- Who was Ruby Bridges? Who are other civil rights activists or heroes from our past?

- What problems are you faced with and how might you create a visual image describing these issues?

- How might you create art that makes a statement about something that is important to you?

- Objectives:

- Students will view The Problem We All Live With by Norman Rockwell.

- Students will consider the historical and cultural events of the time in order to understand the relevant details within the illustration that relay the message.

- Students will brainstorm problems they are currently faced with, complete a Think Sheet, and create a work of visual art that demonstrates an understanding of how the communication of their ideas relates to the media, techniques, and processes they use.

- Background:

After resigning his forty-seven year tenure with The Saturday Evening Post in 1963, Rockwell embraced the challenge of addressing the nation’s pressing concerns in a pared down, reportorial style. The Problem We All Live With for Look magazine is based upon an actual event, in 1960, when six-year-old Ruby Bridges was escorted by US marshals to her first day at an all-white New Orleans school. Rockwell’s depiction of the vulnerable but dignified girl clearly condemns the actions of those who protest her presence and object to desegregation.

Multimedia Resources

- A Conversation with Ruby Bridges Hall

Norman Rockwell Museum

- Ruby Bridges Visits the President and her Portrait

Classroom Supplies:

- Ruby Bridges Goes to School: My True Story by Ruby Bridges

- Large easel with paper pad and pen, or board to record brainstorming ideas on

- Worksheet: The Problem I Live With - Think Sheet (2-4)

- 1. Display The Problem We All Live With . Ask the students if they have seen the image before. Ask the students to look closely at the foreground, the middle ground, and the background and to point out what they see, not what they think. The class will collectively take a visual inventory. You may offer the first example if the students are unclear such as, “I see a girl in a white dress walking with books in her hand.” As each student contributes, restate their observation. You might be able to elaborate on what they have said to add more visual detail or you might ask them for clarification. You might encourage them to look closely and carefully. By doing this, the students will analyze the work and identify clues and symbols to help read the visual image, revealing American culture.

- Ask if anyone can associate the image with issues or events relating to American culture and history. A discussion about civil rights and Ruby Bridges will allow for personal interpretations as well as historically accurate facts about the 1960’s. Conversation about other civil rights activists or heroes is welcomed.

- Read the students the story, Ruby Bridges Goes to School: My True Story , by Ruby Bridges. Offer clarification and allow for questions when something is unclear. Then share with the students the description that is written on the Norman Rockwell Digital collection page about this illustration: ( http://collections.nrm.org/search.do?id=520936&db=object&view=full ).

- Ask the students what they think it would have been like to live during the 1960s with the tensions of the civil rights movement. Allow for the discussion to highlight other appropriate civil rights occurrences and activists. As a group, brainstorm a list of problems the students feel they have encountered, either personally, in their community, or on a national or global scale.. The instructor will record the students’ ideas on easel paper, or a board; this list will be the starting point for students to plan a project of their own.

- Give students the worksheet, The Problem I Live With - Think Sheet, to complete. Walk around the classroom, offering help when a child is ‘stuck’ or needs re-direction or clarification.

- Students will develop a thumbnail sketch and begin to consider what media would best to emphasize the message they wish to convey, or the individual they will be honoring in their artwork.

- Circulate around the room, checking in with each student and providing assistance if they need to talk about their ideas and material needs. Offer suggestions for revisions regarding composition and design.

- The last ten minutes of class will be dedicated to a group share. Each student will be asked to explain their idea and the media they feel is best suited for their project. Throughout the project, students will be encouraged to talk with the instructor and their peers regarding their thoughts, ideas, and frustrations with their project, asking for help or feedback.

Classes 3-4

- Two more classes will be allotted to the completion of the project. Once students have completed the project, ask them to come together to present their project and explain their thoughts. Once each artist has spoken, comments from classmates will be allowed. The comments must be given in a respectful manner, demonstrate critical thinking, and be relevant to the project.

- Allow time for students to prepare and display their artwork before class is dismissed.

- Assessment:

- Students will be evaluated on their participation in the discussion (informal checks of understanding through questions) and completion of the worksheet.

- Students will complete a Think Sheet.

- Students will confer with their peers and the instructor upon completion of the thumbnail sketch and Think Sheet for feedback, suggestions and consider revision suggestions before moving on to begin the final illustration.

- Students will create personally satisfying artwork using a variety of artistic processes and materials.

- Students will select media, techniques, and processes; analyze what makes them effective in communicating their ideas; and reflect upon the effectiveness of their choices.

- Students will demonstrate safe procedures for using and cleaning art tools, equipment, and studio spaces.

- Students will analyze, describe, and demonstrate how factors of time and place (history and culture) influence visual characteristics that give meaning and value to a work of art.

- Students will participate in a group critique and then prepare and hang their illustration for display

This curriculum meets the standards listed below. Look for more details on these standards please visit: ELA and Math Standards , Social Studies Standards , Visual Arts Standards .

- Problem_web-3.jpg

'The Problem We All Live With' by Norman Rockwell

Frederick M. Brown/Stringer/Getty Images

- Art History

- Architecture

On November 14, 1960, six-year-old Ruby Bridges attended William J. Frantz Elementary School in the 9th Ward of New Orleans. It was her first day of school, as well as New Orleans' court-ordered first day of integrated schools.

If you weren't around in the late '50s and early '60s, it may be difficult to imagine just how contentious was the issue of desegregation. A great many people were violently opposed to it. Hateful, shameful things were said and done in protest. There was an angry mob gathered outside of Frantz Elementary on November 14. It wasn't a mob of malcontents or the dregs of society — it was a mob of well-dressed, upstanding housewives. They were shouting such awful obscenities that audio from the scene had to be masked in television coverage.

The 'Ruby Bridges Painting'

Ruby had to be escorted past this offensiveness by Federal marshals. Naturally, the event made the nightly news and anyone who watched it became aware of the story. Norman Rockwell was no exception, and something about the scene — visual, emotional, or perhaps both — lodged it into his artist's consciousness, where it waited until such time as it could be released.

In 1963, Norman Rockwell ended his long relationship with "The Saturday Evening Post" and began working with its competitor "LOOK." He approached Allen Hurlburt, the Art Director at "LOOK," with an idea for a painting of (as Hurlburt wrote) "the Negro child and the marshals." Hurlburt was all for it and told Rockwell it would merit "a complete spread with a bleed on all four sides. The trim size of this space is 21 inches wide by 13 1/4 inches high." Additionally, Hurlburt mentioned that he needed the painting by November 10th in order to run it in an early January 1964 issue.

Rockwell Used Local Models

The child portrays Ruby Bridges as she walked to Frantz Elementary School surrounded, for her protection, by Federal marshals. Of course, we didn't know her name was Ruby Bridges at the time, as the press had not released her name out of concern for her safety. As far as most of the United States knew, she was a nameless six-year-old African-American remarkable in her solitude and for the violence her small presence in a "Whites Only" school engendered.

Cognizant only of her gender and race, Rockwell enlisted the help of then-nine-year-old Lynda Gunn, the granddaughter of a family friend in Stockbridge. Gunn posed for five days, her feet propped at angles with blocks of wood to emulate walking. On the final day, Gunn was joined by the Stockbridge Chief of Police and three U.S. Marshals from Boston.

Rockwell also shot several photographs of his own legs taking steps to have more references of folds and creases in walking men's pant legs. All of these photographs, sketches, and quick painting studies were employed to create the finished canvas.

Technique and Medium

This painting was done in oils on canvas, as were all of Norman Rockwell's other works . You will note, too, that its dimensions are proportionate to the "21 inches wide by 13 1/4 inches high" that Allen Hurlburt requested. Unlike other types of visual artists, illustrators always have space parameters in which to work.

The first thing that stands out in "The Problem We All Live With" is its focal point: the girl. She is positioned slightly left of center but balanced by the large, red splotch on the wall right of center. Rockwell took artistic license with her pristine white dress, hair ribbon, shoes, and socks (Ruby Bridges was wearing a plaid dress and black shoes in the press photograph). This all-white outfit against her dark skin immediately leaps out of the painting to catch the viewer's eye.

The white-on-black area lies in stark contrast to the rest of the composition. The sidewalk is gray, the wall is mottled old concrete, and the Marshals' suits are boringly neutral. In fact, the only other areas of engaging color are the lobbed tomato, the red explosion it has left on the wall, and the Marshals' yellow armbands.

Rockwell also deliberately leaves out the Marshals' heads. They are more powerful symbols because of their anonymity. They are faceless forces of justice ensuring that a court order (partially visible in the left-most marshal's pocket) is enforced — despite the rage of the unseen, screaming mob. The four figures form a sheltering bulwark around the little girl, and the only sign of their tension lies in their clenched right hands.

As the eye travels in a counter-clockwise ellipse around the scene, it is easy to overlook two barely-noticeable elements that are the crux of "The Problem We All Live With." Scrawled on the wall are the racial slur, "N----R," and the menacing acronym, " KKK ."

Where to See 'The Problem We All Live With'

The initial public reaction to "The Problem We All Live With" was stunned disbelief. This was not the Norman Rockwell everyone had grown to expect: the wry humor, the idealized American life, the heartwarming touches, the areas of vibrant color — all of these were conspicuous in their absence. "The Problem We All Live With" was a stark, muted, uncomplicated composition, and the topic! The topic was as humorless and uncomfortable as it gets.

Some previous Rockwell fans were disgusted and thought the painter had taken leave of his senses. Others denounced his "liberal" ways using derogatory language. Many readers squirmed, as this was not the Norman Rockwell they had come to expect. However, the majority of "LOOK" subscribers (after they got over their initial shock) began to give integration more serious thought than they had before. If the issue bothered Norman Rockwell so much that he was willing to take a risk, surely it deserved their closer scrutiny.

Now, nearly 50 years later, it is easier to gauge the importance of "The Problem We All Live With" when it first appeared in 1964. Every school in the United States is integrated, at least by law if not in fact. Although headway has been made, we have yet to become a colorblind society. There are still racists among us, much as we may wish they weren't. Fifty years, half a century, and still the fight for equality continues. In light of this, Norman Rockwell's "The Problem We All Live With" stands out as a more courageous and prescient statement than we originally supposed.

When not out on loan or touring, the painting can be viewed at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

- "Home." Norman Rockwell Museum, 2019.

- Meyer, Susan E. "Norman Rockwells People." Hardcover, Nuova edizione (New Edition) edition, Crescent, March 27, 1987.

- Biography of Ruby Bridges: Civil Rights Movement Hero Since 6 Years Old

- Biography of Norman Rockwell

- Art of the Civil Rights Movement

- Exterior Paint Colors Can Be Hard Choices

- How to Set up Your Classroom for the First Day of School

- What Is Meant by "Emphasis" in Art?

- Black History and Women Timeline 1960-1969

- "These Shining Lives"

- The Life and Work of Maud Lewis, Canadian Folk Artist

- Why Is the Mona Lisa So Famous?

- 54 Famous Paintings Made by Famous Artists

- Vietnam Veterans Memorial

- Civil Rights Movement Timeline From 1951 to 1959

- The Story Behind 'Christina’s World' by Andrew Wyeth

- Biography of Jackson Pollock

- Kerry James Marshall, Artist of the Black Experience

- Exhibitions and fairs

- The Art Market

- Artworks under the lens

- Famous faces

- Movements and techniques

- Partnerships

- … Collectors

- Collections

- Buy art online

Singulart Magazine > Art History > Artworks under the lens > Exploring Norman Rockwell’s The Problem We All Live With (1964)

Exploring Norman Rockwell’s The Problem We All Live With (1964)

Alright folks, gather around because we’re about to dive into the world of Norman Rockwell , the granddaddy of American art. Picture this: charming illustrations, whimsical scenes, and a sprinkle of nostalgia—all brought to life by the master himself. But hold onto your hats because amidst the laughter and smiles, Rockwell had a knack for hitting us right in the feels with some real talk. Enter “ The Problem We All Live With ” (1964), a masterpiece that’s more than just colors on canvas—it’s a punch in the gut, wrapped in a warm hug, and delivered straight to your soul. So buckle up, folks, ’cause we’re about to take a wild ride through art history.

Who was Norman Rockwell?

Norman Rockwell, born in 1894, was an American painter and illustrator whose works have become synonymous with the country’s cultural heritage. Known for his keen observation and portrayal of everyday life, Rockwell’s art captured the spirit of American society with warmth, humor, and pathos.

FUN FACT: Norman Rockwell was an avid collector of toy soldiers! Rockwell had a passion for these miniature warriors and amassed a sizable collection throughout his life.

The Career of Norman Rockwell

Rockwell’s career spanned six decades, during which he created more than 4,000 individual works. His most famous works were his cover illustrations for “The Saturday Evening Post,” which were beloved by the American public for their charm and simplicity, yet profound insight into the human condition.

What is Happening in The Problem We All Live With (1964)?

Here we go, people, hold on tight for a rocking trip through the Art History with Norman Rockwell as our guide and leader! Picture this: It is 1964, and Rockwell, who is known as the artist who mastered the art of depicting everyday life with a twist, chooses to paint something which will make your heart skip a beat. Walk up to “The Problem We All Live With.” This is not a just a couple of colors on a canvas—this one paints a whole mood, creates a vibe and wakes you up all at once.

So, what is the story of this masterpiece? What if you picture a courageous little girl named Ruby Bridges being escorted into school by U.S. Marshals on the other hand, a bunch of people from a neighboring block throwing all sorts of insults like they were throwing confetti? Ruby, her dear soul, is on a crusade—to integrate a school in New Orleans during the time of civil rights movement.

Rockwell in his greatness captures this moment with all the emotions possible. There you have Ruby right there, looking bold and witty, but the audience is throwing the plate of hostility to her face. The contrast is so stark you could cut it with butter knife. However, in the midst of all this confusion, there is a ray of light—a bright spark that shines as bright as the tallest beacon in the dark.

Interesting Facts

Inspiration Behind the Painting: Rockwell was inspired to create “The Problem We All Live With” after reading about Ruby Bridges’ courageous journey in the newspaper. He was deeply moved by her story and felt compelled to capture the moment in his art.

Symbolism of the Composition: The composition of the painting is carefully crafted to convey its powerful message. Ruby Bridges is depicted in the center of the canvas, symbolizing her significance in the struggle for civil rights. The U.S. Marshals flanking her represent the protection of the law and the federal government’s role in enforcing desegregation.

Subtle Details: Despite the simplicity of the scene, Rockwell included several subtle details that add layers of meaning to the painting. For example, the splattered tomato on the wall serves as a stark reminder of the violence and hostility faced by Ruby Bridges and other African American students during desegregation.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is norman rockwell’s art style called.

Norman Rockwell’s painting technique is known as photorealism because, despite the fact that his works resemble photographs, they were created using genuine images that he took. Although Rockwell started out painting from life, he eventually turned to painting from pictures.

What influenced Rockwell’s style of art?

Norman Rockwell owes a great deal to the prominent and stylish illustrators of his day, including JC Leyendecker, Maxfield Parrish, Howard Pyle, and NC Wyeth. His workshop was filled with other artists’ paintings, including a Parrish, a Leyendecker, and multiple Pyles.

Norman Rockwell’s “The Problem We All Live With” is not just a painting; it shows the guts and courage of the people who fought for equality and justice. In his art, Rockwell elucidates the grotesque reality of racism as well as the indomitability of the human spirit. It has become almost a symbol of this never-ending battle for equal rights and the importance of resisting oppression.

You May Also Like

Exploring the Artistry of Hiroshi Nagai’s Palm Springs

Exploring Meditación Trascendental by Tomás Sánchez

Interview with Albrecht Behmel: "My background as a writer gives me a special perspective on how to tell a story."

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

The Problem We All Live With - Part Two

Last week we looked at a school district integrating by accident. This week: a city going all out to integrate its schools. Plus, a girl who comes up with her own one-woman integration plan.

- Download Control-click (or right-click) Tap and hold to download

- Subscribe on Spotify Subscribe in Apple Podcasts Subscribe

Norman Rockwell's "The Problem We All Live With," depicting Ruby Bridges, the first Black child to attend an all white elementary school in the South.

Artwork approved by The Norman Rockwell Family Agency.

More in this Series

The Problem We All Live With - Part One

My secret public plan, what’s it all about, arne, act two: the morning, act six: massachusetts, act one: climb spree, staff recommendations.

Americans in Paris

David Sedaris takes Ira on a tour of his favorite spots in Paris.

Petty Tyrant

The rise and fall of a school maintenance man in Schenectady, New York who terrorized his staff and got away with it for decades.

- in Apple Podcasts

- My presentations

Auth with social network:

Download presentation

We think you have liked this presentation. If you wish to download it, please recommend it to your friends in any social system. Share buttons are a little bit lower. Thank you!

Presentation is loading. Please wait.

“The Problem We All Live With” –Norman Rockwell. AP Language and Composition “It’s a Troubling Tuesday!” February 26, 2013 Mr. Houghteling.

Published by Merry Washington Modified over 8 years ago

Similar presentations

Presentation on theme: "“The Problem We All Live With” –Norman Rockwell. AP Language and Composition “It’s a Troubling Tuesday!” February 26, 2013 Mr. Houghteling."— Presentation transcript:

Ethos, Pathos, and Logos.

How to write a rhetorical analysis

Argumentation EVERYTHING IS AN ARGUMENT. EVERYTHING!!!!!

English 10 Honors Day 7 - Objectives: - To apply understanding of rhetorical devices such as persuasive appeals.

9/14/09 Bellringer—Making Inferences

Rhetorical Appeals ARISTOTLE & BEYOND.

September 6, 2013 Mr. Houghteling English III “It’s a Feel-good Friday, and because it’s Friday, you know what that means…!”

S Nichols Ms.Stein APLC; P3 13.Feb America’s Grey Lady Photograph. americanmoralsociety.org Web. 12 Jan 2012.

Rhetoric and Analysis. What is rhetoric? Aristotle defines rhetoric as “The faculty of observing in any given case the available means of persuasion”

Muhammad Asim Azeem Mrs. Stite’s 3 rd period AP English Language and Composition HUEY P. LONG’S “EVERY MAN A KING” SPEECH.

Rhetoric DEFINITION: a thoughtful, reflective activity leading to effective communication, including rational exchange of opposing viewpoints THE POWER.

Ethos and Michael Vick In 2007, after the arraignment of NFL quarterback Michael Vick on dog-fighting charges, Nike (who along with Coca-Cola, Kraft,

If you were a student in a troubled school, what advice would you give to a new principal in order to change the culture of the school? Please explain.

By the end of today’s class you should: ◦ Understand: The purpose of rhetorical analysis Elements to consider when analyzing a text Rhetorical.

Thomas Freeman WRIT 122. There are three ways in which a person can argue their position. These ways consist of ethos, logos and pathos. These different.

By: Josh Gooch National Spelling Bee. BACKGROUND Cartoonist: Mike Luckovich Published by the Atlanta journal-Constitution in 2009.

“It’s a Through and Through Thursday!” AP Language and Composition November 29, 2012 Mr. Houghteling.

AP Language and Composition March 7, 2013 Mr. Houghteling “It’s a Therapeutic Thursday!”

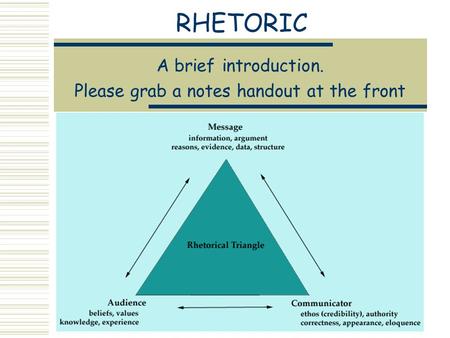

RHETORIC A brief introduction. Please grab a notes handout at the front.

A Lesson on Rhetorical Devices: Ethos, Pathos, Logos

About project

© 2024 SlidePlayer.com Inc. All rights reserved.

Where next?

Explore related content

"The Problem We All Live With"

Norman rockwell 1963, norman rockwell museum in stockbridge, ma stockbridge, ma, united states.

Illustration for “Look,” January 14, 1964.

Rockwell’s first assignment for "Look" magazine was an illustration of a six-year-old African-American schoolgirl being escorted by four U.S. marshals to her first day at an all-white school in New Orleans . Ordered to proceed with school desegregation after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling, Louisiana lagged behind until pressure from Federal Judge Skelly Wright forced the school board to begin desegregation on November 14, 1960.

Letters to the editor were a mix of praise and criticism. One Florida reader wrote, “Rockwell’s picture is worth a thousand words … I am saving this issue for my children with the hope that by the time they become old enough to comprehend its meaning, the subject matter will have become history.” Other readers objected to Rockwell’s image. A man from Texas wrote “Just where does Norman Rockwell live? Just where does your editor live? Probably both of these men live in all-white, highly expensive highly exclusive neighborhoods. Oh what hypocrites all of you are!” The most shocking letter came from a man in New Orleans who called Rockwell’s work, “just some more vicious lying propaganda being used for the crime of racial integration by such black journals as Look, Life, etc.” But irate opinions did not stop Rockwell from pursuing his course. In 1965, he illustrated the murder of civil rights workers in Philadelphia, Mississippi, and in 1967, he chose children, once again, to illustrate desegregation, this time in our suburbs.

In an interview later in his life, Rockwell recalled that he once had to paint out an African -American person in a group picture since "The Saturday Evening Post" policy dictated showing African-Americans in service industry jobs only. Freed from such restraints, Rockwell seemed to look for opportunities to correct the editorial prejudices reflected in his previous work. "The Problem We All Live With," "Murder in Mississippi," and "New Kids in the Neighborhood" ushered in that new era for Rockwell.

- Title: "The Problem We All Live With"

- Creator: Norman Rockwell (1894-1978)

- Date Created: 1963

- Credit Line: Norman Rockwell Museum Collection. All Rights Reserved.

- Rights: Norman Rockwell Museum Collection. All Rights Reserved.

- Medium: Oil on Canvas

Get the app

Explore museums and play with Art Transfer, Pocket Galleries, Art Selfie, and more

The Problem We All Live With

deborah.kielbassa

Created on January 23, 2022

classe de 3èmes

More creations to inspire you

Explloring space.

Presentation

UNCOVERING REALITY

Spring has sprung, the ocean's depths, 2021 trending colors, political polarization, vaccines & immunity.

Discover more incredible creations here

norman rockwell

Useful links

Information on the painting

Wordreference

Historical background

The document

aNSWER THE QUESTIONS IN ENGLISH

1. What sort of document is it?2. What is the technique used?3. Explain the word "hyperrealism.4. Who can you see on the document?5. What does the girl have in her hand?

I. The document

II. Watch the video and answer the questions

1. When and where was she born ?2. Where could you see people segregated ? Give 3 examples. 3. What was the law of 1954 about ?4. How long did they wait ? 5. Why is Ruby Bridges so important ? 6. What was the reactions of people ? 7. What was so particular at school ?8. What does Ruby Bridges do TODAY?

Ruby bridges biography

1. Explain the context in the USA in the 1950’s-60’s ?2. What can you see in the background on the wall?

III. Historical background

1. What does the painter want us to look at ? How does he do it ? 2. Why are the men’s heads not painted ?3. Why is the girl closer (plus proche) to the 2 marshalls in front of her ? 4. What does the colour « white » symbolize ? 5. What does the colour « red » symbolize ? 6. What does the colour « yellow » represent ? 7. Why does the author use « WE » in the title? 8. What « problem » does Rockwell denounce ?

IV. Analysis and interpretation

1. Where are President Obama and Ruby Bridges ? 2. Why ? 3. Can you make a link with the mural by Mr Brainwash ? 4. What was the name of the school Ruby attended ? 5. Did Ruby know what was about to happen that day ? 6. How does Ruby explain « racism » ? 7. What was the « lesson » that she learned ?

V. Watch the video and answer the questions

Ruby's visit to president obama

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE PAINTING

Have you finished?

Jump to navigation

The IVLP and “The Problem We All Live With”

This summer, the U.S. Department of State’s Office of International Visitors (OIV) initiated a virtual International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP) project which explored racial and social disparities, probing America’s complicated history, current social justice movements, and the disproportionate impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on communities of color.

The project was titled, “The Problem We All Live With: Dismantling Racial and Social Injustice,” alluding to the 1964 Norman Rockwell painting which depicts an iconic moment from the U.S. Civil Rights Movement.

Twenty-five participants, representing twenty-three countries, attended virtual sessions hosted by program partners in Washington, DC; Cleveland, Ohio; San Francisco, California; Jackson, Mississippi; and Little Rock, Arkansas. Accompanying these meetings was a special presentation delivered by the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations Linda Thomas-Greenfield. During her remarks, Ambassador Thomas-Greenfield highlighted her personal story and encouraged the participants to work together to dismantle systemic racism and advance civil rights in their own countries and around the world. The video of Ambassador Thomas-Greenfield’s presentation is available below.

By the end of the project, many participants expressed a greater sense of understanding of the Black American experience in the United States and noted that they were motivated and dedicated to continuing the fight toward dismantling racism in their own countries. Khalid Ghali Bada, a virtual participant from Spain, shared, “One of the most significant concepts I’ve come to understand, during this program, is the correlation between legislation, the administrative political system, and racial hierarchy. By understanding this, it has given me an understanding of institutional racism in the U.S. and how it produces inequality in multiple areas.”

Through short-term exchanges, the IVLP allows current and emerging foreign leaders to foster lasting relationships with American counterparts, address topics of strategic interest, and develop greater familiarity and understanding of American culture and communities.

View related content by tag

- International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP)

You might also be interested in

Meeting with International Visitors Is Just the Beginning for New York Couple

Kenya on My Mind: An Interview with Mayor Heidi Davison

Turkmenistan Participant Connects with Disabilities Organizations

Bureau of educational and cultural affairs, promoting mutual understanding, status message.

Turning Point

Dr. david jeremiah, the great disappearance interview with david jeremiah - encore presentation, part 2.

As the Rapture draws closer, what should believers be doing to prepare for it? Dr. David Jeremiah and guest Sheila Walsh tackle this question as they talk more about David’s new book, The Great Disappearance.

Featured Offer

- Special Programming

- Spiritual Warfare: The Armor of the Believer

- Ten Questions Christians Are Asking

- The Great Disappearance

- Until Christ Returns

- Heaven and Hell

- Sharing the Gospel

- The Rapture

About Turning Point

About dr. david jeremiah.

Dr. David Jeremiah is the founder of Turning Point for God, an international broadcast ministry committed to providing Christians with sound Bible teaching through radio and television, the Internet, live events, and resource materials and books. He is the author of more than fifty books including The Book of Signs, Forward, and Where Do We Go From Here? David serves as senior pastor of Shadow Mountain Community Church in San Diego, California, where he resides with his wife, Donna. They have four grown children and twelve grandchildren.

Contact Turning Point with Dr. David Jeremiah

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

Share Podcast

A Better Framework for Solving Tough Problems

Start with trust and end with speed.

- Apple Podcasts

When it comes to solving complicated problems, the default for many organizational leaders is to take their time to work through the issues at hand. Unfortunately, that often leads to patchwork solutions or problems not truly getting resolved.

But Anne Morriss offers a different framework. In this episode, she outlines a five-step process for solving any problem and explains why starting with trust and ending with speed is so important for effective change leadership. As she says, “Let’s get into dialogue with the people who are also impacted by the problem before we start running down the path of solving it.”

Morriss is an entrepreneur and leadership coach. She’s also the coauthor of the book, Move Fast and Fix Things: The Trusted Leader’s Guide to Solving Hard Problems .

Key episode topics include: strategy, decision making and problem solving, strategy execution, managing people, collaboration and teams, trustworthiness, organizational culture, change leadership, problem solving, leadership.

HBR On Strategy curates the best case studies and conversations with the world’s top business and management experts, to help you unlock new ways of doing business. New episodes every week.

- Listen to the full HBR IdeaCast episode: How to Solve Tough Problems Better and Faster (2023)

- Find more episodes of HBR IdeaCast

- Discover 100 years of Harvard Business Review articles, case studies, podcasts, and more at HBR.org .

HANNAH BATES: Welcome to HBR On Strategy , case studies and conversations with the world’s top business and management experts, hand-selected to help you unlock new ways of doing business.

When it comes to solving complicated problems, many leaders only focus on the most apparent issues. Unfortunately that often leads to patchwork or partial solutions. But Anne Morriss offers a different framework that aims to truly tackle big problems by first leaning into trust and then focusing on speed.

Morriss is an entrepreneur and leadership coach. She’s also the co-author of the book, Move Fast and Fix Things: The Trusted Leader’s Guide to Solving Hard Problems . In this episode, she outlines a five-step process for solving any problem. Some, she says, can be solved in a week, while others take much longer. She also explains why starting with trust and ending with speed is so important for effective change leadership.

This episode originally aired on HBR IdeaCast in October 2023. Here it is.

CURT NICKISCH: Welcome to the HBR IdeaCast from Harvard Business Review. I’m Curt Nickisch.

Problems can be intimidating. Sure, some problems are fun to dig into. You roll up your sleeves, you just take care of them; but others, well, they’re complicated. Sometimes it’s hard to wrap your brain around a problem, much less fix it.

And that’s especially true for leaders in organizations where problems are often layered and complex. They sometimes demand technical, financial, or interpersonal knowledge to fix. And whether it’s avoidance on the leaders’ part or just the perception that a problem is systemic or even intractable, problems find a way to endure, to keep going, to keep being a problem that everyone tries to work around or just puts up with.

But today’s guest says that just compounds it and makes the problem harder to fix. Instead, she says, speed and momentum are key to overcoming a problem.

Anne Morriss is an entrepreneur, leadership coach and founder of the Leadership Consortium and with Harvard Business School Professor Francis Frei, she wrote the new book, Move Fast and Fix Things: The Trusted Leaders Guide to Solving Hard Problems . Anne, welcome back to the show.

ANNE MORRISS: Curt, thank you so much for having me.

CURT NICKISCH: So, to generate momentum at an organization, you say that you really need speed and trust. We’ll get into those essential ingredients some more, but why are those two essential?

ANNE MORRISS: Yeah. Well, the essential pattern that we observed was that the most effective change leaders out there were building trust and speed, and it didn’t seem to be a well-known observation. We all know the phrase, “Move fast and break things,” but the people who were really getting it right were moving fast and fixing things, and that was really our jumping off point. So when we dug into the pattern, what we observed was they were building trust first and then speed. This foundation of trust was what allowed them to fix more things and break fewer.

CURT NICKISCH: Trust sounds like a slow thing, right? If you talk about building trust, that is something that takes interactions, it takes communication, it takes experiences. Does that run counter to the speed idea?

ANNE MORRISS: Yeah. Well, this issue of trust is something we’ve been looking at for over a decade. One of the headlines in our research is it’s actually something we’re building and rebuilding and breaking all the time. And so instead of being this precious, almost farbege egg, it’s this thing that is constantly in motion and this thing that we can really impact when we’re deliberate about our choices and have some self-awareness around where it’s breaking down and how it’s breaking down.

CURT NICKISCH: You said break trust in there, which is intriguing, right? That you may have to break trust to build trust. Can you explain that a little?

ANNE MORRISS: Yeah, well, I’ll clarify. It’s not that you have to break it in order to build it. It’s just that we all do it some of the time. Most of us are trusted most of the time. Most of your listeners I imagine are trusted most of the time, but all of us have a pattern where we break trust or where we don’t build as much as could be possible.

CURT NICKISCH: I want to talk about speed, this other essential ingredient that’s so intriguing, right? Because you think about solving hard problems as something that just takes a lot of time and thinking and coordination and planning and designing. Explain what you mean by it? And also, just how we maybe approach problems wrong by taking them on too slowly?

ANNE MORRISS: Well, Curt, no one has ever said to us, “I wish I had taken longer and done less.” We hear the opposite all the time, by the way. So what we really set out to do was to create a playbook that anyone can use to take less time to do more of the things that are going to make your teams and organizations stronger.

And the way we set up the book is okay, it’s really a five step process. Speed is the last step. It’s the payoff for the hard work you’re going to do to figure out your problem, build or rebuild trust, expand the team in thoughtful and strategic ways, and then tell a real and compelling story about the change you’re leading.

Only then do you get to go fast, but that’s an essential part of the process, and we find that either people under emphasize it or speed has gotten a bad name in this world of moving fast and breaking things. And part of our mission for sure was to rehabilitate speed’s reputation because it is an essential part of the change leader’s equation. It can be the difference between good intentions and getting anything done at all.

CURT NICKISCH: You know, the fact that nobody ever tells you, “I wish we had done less and taken more time.” I think we all feel that, right? Sometimes we do something and then realize, “Oh, that wasn’t that hard and why did it take me so long to do it? And I wish I’d done this a long time ago.” Is it ever possible to solve a problem too quickly?

ANNE MORRISS: Absolutely. And we see that all the time too. What we push people to do in those scenarios is really take a look at the underlying issue because in most cases, the solution is not to take your foot off the accelerator per se and slow down. The solution is to get into the underlying problem. So if it’s burnout or a strategic disconnect between what you’re building and the marketplace you’re serving, what we find is the anxiety that people attach to speed or the frustration people attach to speed is often misplaced.

CURT NICKISCH: What is a good timeline to think about solving a problem then? Because if we by default take too long or else jump ahead and we don’t fix it right, what’s a good target time to have in your mind for how long solving a problem should take?

ANNE MORRISS: Yeah. Well, we’re playful in the book and talking about the idea that many problems can be solved in a week. We set the book up five chapters. They’re titled Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and we’re definitely having fun with that. And yet, if you count the hours in a week, there are a lot of them. Many of our problems, if you were to spend a focused 40 hours of effort on a problem, you’re going to get pretty far.

But our main message is, listen, of course it’s going to depend on the nature of the problem, and you’re going to take weeks and maybe even some cases months to get to the other side. What we don’t want you to do is take years, which tends to be our default timeline for solving hard problems.

CURT NICKISCH: So you say to start with identifying the problem that’s holding you back, seems kind of obvious. But where do companies go right and wrong with this first step of just identifying the problem that’s holding you back?

ANNE MORRISS: And our goal is that all of these are going to feel obvious in retrospect. The problem is we skip over a lot of these steps and this is why we wanted to underline them. So this one is really rooted in our observation and I think the pattern of our species that we tend to be overconfident in the quality of our thoughts, particularly when it comes to diagnosing problems.

And so we want to invite you to start in a very humble and curious place, which tends not to be our default mode when we’re showing up for work. We convince ourselves that we’re being paid for our judgment. That’s exactly what gets reinforced everywhere. And so we tend to counterintuitively, given what we just talked about, we tend to move too quickly through the diagnostic phase.

CURT NICKISCH: “I know what to do, that’s why you hired me.”

ANNE MORRISS: Exactly. “I know what to do. That’s why you hired me. I’ve seen this before. I have a plan. Follow me.” We get rewarded for the expression of confidence and clarity. And so what we’re inviting people to do here is actually pause and really lean into what are the root causes of the problem you’re seeing? What are some alternative explanations? Let’s get into dialogue with the people who are also impacted by the problem before we start running down the path of solving it.

CURT NICKISCH: So what do you recommend for this step, for getting to the root of the problem? What are questions you should ask? What’s the right thought process? What do you do on Monday of the week?

ANNE MORRISS: In our experience of doing this work, people tend to undervalue the power of conversation, particularly with other people in the organization. So we will often advocate putting together a team of problem solvers, make it a temporary team, really pull in people who have a particular perspective on the problem and create the space, make it as psychologically safe as you can for people to really, as Chris Argyris so beautifully articulated, discuss the undiscussable.

And so the conditions for that are going to look different in every organization depending on the problem, but if you can get a space where smart people who have direct experience of a problem are in a room and talking honestly with each other, you can make an extraordinary amount of progress, certainly in a day.

CURT NICKISCH: Yeah, that gets back to the trust piece.

ANNE MORRISS: Definitely.

CURT NICKISCH: How do you like to start that meeting, or how do you like to talk about it? I’m just curious what somebody on that team might hear in that meeting, just to get the sense that it’s psychologically safe, you can discuss the undiscussable and you’re also focusing on the identification part. What’s key to communicate there?

ANNE MORRISS: Yeah. Well, we sometimes encourage people to do a little bit of data gathering before those conversations. So the power of a quick anonymous survey around whatever problem you’re solving, but also be really thoughtful about the questions you’re going to ask in the moment. So a little bit of preparation can go a long way and a little bit of thoughtfulness about the power dynamic. So who’s going to walk in there with license to speak and who’s going to hold back? So being thoughtful about the agenda, about the questions you’re asking about the room, about the facilitation, and then courage is a very infectious emotion.

So if you can early on create the conditions for people to show up bravely in that conversation, then the chance that you’re going to get good information and that you’re going to walk out of that room with new insight in the problem that you didn’t have when you walked in is extraordinarily high.

CURT NICKISCH: Now, in those discussions, you may have people who have different perspectives on what the problem really is. They also bear different costs of addressing the problem or solving it. You talked about the power dynamic, but there’s also an unfairness dynamic of who’s going to actually have to do the work to take care of it, and I wonder how you create a culture in that meeting where it’s the most productive?

ANNE MORRISS: For sure, the burden of work is not going to be equitably distributed around the room. But I would say, Curt, the dynamic that we see most often is that people are deeply relieved that hard problems are being addressed. So it really can create, and more often than not in our experience, it does create this beautiful flywheel of action, creativity, optimism. Often when problems haven’t been addressed, there is a fair amount of anxiety in the organization, frustration, stagnation. And so credible movement towards action and progress is often the best antidote. So even if the plan isn’t super clear yet, if it’s credible, given who’s in the room and their decision rights and mandate, if there’s real momentum coming out of that to make progress, then that tends to be deeply energizing to people.

CURT NICKISCH: I wonder if there’s an organization that you’ve worked with that you could talk about how this rolled out and how this took shape?

ANNE MORRISS: When we started working with Uber, that was wrestling with some very public issues of culture and trust with a range of stakeholders internally, the organization, also external, that work really started with a campaign of listening and really trying to understand where trust was breaking down from the perspective of these stakeholders?

So whether it was female employees or regulators or riders who had safety concerns getting into the car with a stranger. This work, it starts with an honest internal dialogue, but often the problem has threads that go external. And so bringing that same commitment to curiosity and humility and dialogue to anyone who’s impacted by the problem is the fastest way to surface what’s really going on.

CURT NICKISCH: There’s a step in this process that you lay out and that’s communicating powerfully as a leader. So we’ve heard about listening and trust building, but now you’re talking about powerful communication. How do you do this and why is it maybe this step in the process rather than the first thing you do or the last thing you do?

ANNE MORRISS: So in our process, again, it’s the days of the week. On Monday you figured out the problem. Tuesday you really got into the sandbox in figuring out what a good enough plan is for building trust. Wednesday, step three, you made it better. You created an even better plan, bringing in new perspectives. Thursday, this fourth step is the day we’re saying you got to go get buy-in. You got to bring other people along. And again, this is a step where we see people often underinvest in the power and payoff of really executing it well.

CURT NICKISCH: How does that go wrong?

ANNE MORRISS: Yeah, people don’t know the why. Human behavior and the change in human behavior really depends on a strong why. It’s not just a selfish, “What’s in it for me?” Although that’s helpful, but where are we going? I may be invested in a status quo and I need to understand, okay, if you’re going to ask me to change, if you’re going to invite me into this uncomfortable place of doing things differently, why am I here? Help me understand it and articulate the way forward and language that not only I can understand, but also that’s going to be motivating to me.

CURT NICKISCH: And who on my team was part of this process and all that kind of stuff?

ANNE MORRISS: Oh, yeah. I may have some really important questions that may be in the way of my buy-in and commitment to this plan. So certainly creating a space where those questions can be addressed is essential. But what we found is that there is an architecture of a great change story, and it starts with honoring the past, honoring the starting place. Sometimes we’re so excited about the change and animated about the change that what has happened before or what is even happening in the present tense is low on our list of priorities.

Or we want to label it bad, because that’s the way we’ve thought about the change, but really pausing and honoring what came before you and all the reasonable decisions that led up to it, I think can be really helpful to getting people emotionally where you want them to be willing to be guided by you. Going back to Uber, when Dara Khosrowshahi came in.

CURT NICKISCH: This is the new CEO.

ANNE MORRISS: The new CEO.

CURT NICKISCH: Replaced Travis Kalanick, the founder and first CEO, yeah.

ANNE MORRISS: Yeah, and had his first all-hands meeting. One of his key messages, and this is a quote, was that he was going to retain the edge that had made Uber, “A force of nature.” And in that meeting, the crowd went wild because this is also a company that had been beaten up publicly for months and months and months, and it was a really powerful choice. And his predecessor, Travis was in the room, and he also honored Travis’ incredible work and investment in bringing the company to the place where it was.

And I would use words like grace to also describe those choices, but there’s also an incredible strategic value to naming the starting place for everybody in the room because in most cases, most people in that room played a role in getting to that starting place, and you’re acknowledging that.

CURT NICKISCH: You can call it grace. Somebody else might call it diplomatic or strategic. But yeah, I guess like it or not, it’s helpful to call out and honor the complexity of the way things have been done and also the change that’s happening.

ANNE MORRISS: Yeah, and the value. Sometimes honoring the past is also owning what didn’t work or what wasn’t working for stakeholders or segments of the employee team, and we see that around culture change. Sometimes you’ve got to acknowledge that it was not an equitable environment, but whatever the worker, everyone in that room is bringing that pass with them. So again, making it discussable and using it as the jumping off place is where we advise people to start.

Then you’ve earned the right to talk about the change mandate, which we suggest using clear and compelling language about the why. “This is what happened, this is where we are, this is the good and the bad of it, and here’s the case for change.”

And then the last part, which is to describe a rigorous and optimistic way forward. It’s a simple past, present, future arc, which will be familiar to human beings. We love stories as human beings. It’s among the most powerful currency we have to make sense of the world.

CURT NICKISCH: Yeah. Chronological is a pretty powerful order.

ANNE MORRISS: Right. But again, the change leaders we see really get it right, are investing an incredible amount of time into the storytelling part of their job. Ursula Burns, the Head of Xerox is famous for the months and years she spent on the road just telling the story of Xerox’s change, its pivot into services to everyone who would listen, and that was a huge part of her success.

CURT NICKISCH: So Friday or your fifth step, you end with empowering teams and removing roadblocks. That seems obvious, but it’s critical. Can you dig into that a little bit?

ANNE MORRISS: Yeah. Friday is the fun day. Friday’s the release of energy into the system. Again, you’ve now earned the right to go fast. You have a plan, you’re pretty confident it’s going to work. You’ve told the story of change the organization, and now you get to sprint. So this is about really executing with urgency, and it’s about a lot of the tactics of speed is where we focus in the book. So the tactics of empowerment, making tough strategic trade-offs so that your priorities are clear and clearly communicated, creating mechanisms to fast-track progress. At Etsy, CEO Josh Silverman, he labeled these projects ambulances. It’s an unfortunate metaphor, but it’s super memorable. These are the products that get to speed out in front of the other ones because the stakes are high and the clock is sticking.

CURT NICKISCH: You pull over and let it go by.

ANNE MORRISS: Yeah, exactly. And so we have to agree as an organization on how to do something like that. And so we see lots of great examples both in young organizations and big complex biotech companies with lots of regulatory guardrails have still found ways to do this gracefully.

And I think we end with this idea of conflict debt, which is a term we really love. Leanne Davey, who’s a team scholar and researcher, and anyone in a tech company will recognize the idea of tech debt, which is this weight the organization drags around until they resolve it. Conflict debt is a beautiful metaphor because it is this weight that we drag around and slows us down until we decide to clean it up and fix it. The organizations that are really getting speed right have figured out either formally or informally, how to create an environment where conflict and disagreements can be gracefully resolved.

CURT NICKISCH: Well, let’s talk about this speed more, right? Because I think this is one of those places that maybe people go wrong or take too long, and then you lose the awareness of the problem, you lose that urgency. And then that also just makes it less effective, right? It’s not just about getting the problem solved as quickly as possible. It’s also just speed in some ways helps solve the problem.

ANNE MORRISS: Oh, yeah. It really is the difference between imagining the change you want to lead and really being able to bring it to life. Speed is the thing that unlocks your ability to lead change. It needs a foundation, and that’s what Monday through Thursday is all about, steps one through four, but the finish line is executing with urgency, and it’s that urgency that releases the system’s energy, that communicates your priorities, that creates the conditions for your team to make progress.

CURT NICKISCH: Moving fast is something that entrepreneurs and tech companies certainly understand, but there’s also this awareness that with big companies, the bigger the organization, the harder it is to turn the aircraft carrier around, right? Is speed relative when you get at those levels, or do you think this is something that any company should be able to apply equally?

ANNE MORRISS: We think this applies to any company. The culture really lives at the level of team. So we believe you can make a tremendous amount of progress even within your circle of control as a team leader. I want to bring some humility to this and careful of words like universal, but we do think there’s some universal truths here around the value of speed, and then some of the byproducts like keeping fantastic people. Your best people want to solve problems, they want to execute, they want to make progress and speed, and the ability to do that is going to be a variable in their own equation of whether they stay or they go somewhere else where they can have an impact.

CURT NICKISCH: Right. They want to accomplish something before they go or before they retire or finish something out. And if you’re able to just bring more things on the horizon and have it not feel like it’s going to be another two years to do something meaningful.

ANNE MORRISS: People – I mean, they want to make stuff happen and they want to be around the energy and the vitality of making things happen, which again, is also a super infectious phenomenon. One of the most important jobs of a leader, we believe, is to set the metabolic pace of their teams and organizations. And so what we really dig into on Friday is, well, what does that look like to speed something up? What are the tactics of that?

CURT NICKISCH: I wonder if that universal truth, that a body in motion stays in motion applies to organizations, right? If an organization in motion stays in motion, there is something to that.

ANNE MORRISS: Absolutely.

CURT NICKISCH: Do you have a favorite client story to share, just where you saw speed just become a bit of a flywheel or just a positive reinforcement loop for more positive change at the organization?

ANNE MORRISS: Yeah. We work with a fair number of organizations that are on fire. We do a fair amount of firefighting, but we also less dramatically do a lot of fire prevention. So we’re brought into organizations that are working well and want to get better, looking out on the horizon. That work is super gratifying, and there is always a component of, well, how do we speed this up?

What I love about that work is there’s often already a high foundation of trust, and so it’s, well, how do we maintain that foundation but move this flywheel, as you said, even faster? And it’s really energizing because often there’s a lot of pent-up energy that… There’s a lot of loyalty to the organization, but often it’s also frustration and pent-up energy. And so when that gets released, when good people get the opportunity to sprint for the first time in a little while, it’s incredibly energizing, not just for us, but for the whole organization.

CURT NICKISCH: Anne, this is great. I think finding a way to solve problems better but also faster is going to be really helpful. So thanks for coming on the show to talk about it.

ANNE MORRISS: Oh, Curt, it was such a pleasure. This is my favorite conversation. I’m delighted to have it anytime.

HANNAH BATES: That was entrepreneur, leadership coach, and author Anne Morriss – in conversation with Curt Nickisch on HBR IdeaCast.

We’ll be back next Wednesday with another hand-picked conversation about business strategy from Harvard Business Review. If you found this episode helpful, share it with your friends and colleagues, and follow our show on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts. While you’re there, be sure to leave us a review.

When you’re ready for more podcasts, articles, case studies, books, and videos with the world’s top business and management experts, you’ll find it all at HBR.org.

This episode was produced by Mary Dooe, Anne Saini, and me, Hannah Bates. Ian Fox is our editor. Special thanks to Rob Eckhardt, Maureen Hoch, Erica Truxler, Ramsey Khabbaz, Nicole Smith, Anne Bartholomew, and you – our listener. See you next week.

- Subscribe On:

Latest in this series

This article is about strategy.

- Decision making and problem solving

- Strategy execution

- Leadership and managing people

- Collaboration and teams

- Trustworthiness

- Organizational culture

Partner Center

1J1Q - THE PROBLEM WE ALL LIVE WITH

Pôle LVE DSDEN34

Created on March 22, 2023

Ressources Pôle LV - DSDEN34 - 2022/2023

More creations to inspire you

Intro innovate.

Presentation

FALL ZINE 2018

Branches of u.s. government, quote of the week activity - 10 weeks, master's thesis english, spanish: partes de la casa with review, private tour in são paulo.

Discover more incredible creations here

SOFT CLIL / EMILE

Video et questions.

The problem we all live with Norman ROCKWELL

I FEEL ....

Flashcards et audio

Séquence, annexes et audio

CYCLE 2 = LEXIQUE & STRUCTURE

FICHE DE L'ENSEIGNANT

Questionnaire cycle 2 imprimable

Script de la présentation

ACCÈS AUX QUESTIONS EN LIGNE

CYCLE 2 = VIDEO & QUESTIONS

Norman Rockwell

David hockney, edward hopper.

Pôle d'expertise « Langues vivantes »

Quiz Cycle 2 - Question 1

Noman Rockwell

Quiz Cycle 2 -Réponse 1

Quiz Cycle 2 - Question 2

Quiz Cycle 2 - Réponse 2

Listen and click on the right answer...

Quiz Cycle 2 - Question 3

Quiz Cycle 2 - Réponse 3

Quiz Cycle 2 - Question 4

Quiz Cycle 2 - Réponse 4

Quiz Cycle 2 - Question 5

Quiz Cycle 3 - Réponse 5

Quiz Cycle 2 - Question 6

Quiz Cycle 2 - Réponse 6

Quiz Cycle 2 - Question 7

Quiz Cycle 3 - Réponse 7

Quiz Cycle 2 - Question 8

Quiz Cycle 2 -Réponse 8

https://etab.ac-poitiers.fr/coll-champdeniers/IMG/pdf/hda_doc.pdf

http://www.moreeuw.com/histoire-art/norman-rockwell.htm

Quiz Cycle 2 - Question Bonus

Quiz Cycle 2 - Réponse Bonus

CYCLE 2 = SOFT CLIL

Thème : PHOTOS & FEELINGS

Présentation d'oeuvres

Séquence, visuels & fichiers audio

CYCLE 3 = LEXIQUE & STRUCTURE

WEARING CLOTHES

CYCLE 3 = VIDEO & QUESTIONS

Questionnaire cycle 3 imprimable

Quiz Cycle 3 - Question 1

Quiz Cycle 3 -Réponse 1

A girl and four men

A girl with her friends, a girl and her family.

Quiz Cycle 3 - Question 2

Quiz Cycle 3 - Réponse 2

Quiz Cycle 3 - Question 3

Quiz Cycle 3 - Réponse 3

grey dresses

Quiz Cycle 3 - Question 4

Quiz Cycle 3 - Réponse 4

Quiz Cycle 3 - Question 5

their heads

Quiz Cycle 3 - Question 6

They are walking.

Quiz Cycle 3 - Réponse 6

Quiz Cycle 3 - Question 7

Quiz Cycle 3 - Question 8

She is goint to the hospital.

She is going to school., she is going to the police station..

Quiz Cycle 3 -Réponse 8

What was the name of the real girl?

Quiz Cycle 3 - Question Bonus

She was called Ruby Bridges

Quiz Cycle 3 - Réponse Bonus

CYCLE 3 = SOFT CLIL

Thème : PHOTOS vs PAINTINGS

Séquence, flashcards,fichiers audio

COMMENTS

The Problem We All Live With, published in LOOK in 1964, took on the issue of school segregation. While some readers missed the Rockwell of happier times, others praised him for tackling serious issues. Together, his early idyllic and later realistic views of American life represent the artist's personal portrait of our nation.

The Problem We All Live With is a 1964 painting by Norman Rockwell that is considered an iconic image of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States. It depicts Ruby Bridges, a six-year-old African-American girl, on her way to William Frantz Elementary School, an all-white public school, on November 14, 1960, during the New Orleans school desegregation crisis.

Oral Brevet "The problem we all live with" de Norman Rockwell Maammeur Selma 3e1 problématique analyse présentation de l'artiste présentation de l'oeuvre contexte historique ... How to create and deliver a winning team presentation; May 24, 2024. What are AI writing tools and how can they help with making presentations? May 22, 2024 ...

The Problem We All Live With PART ONE. Nikole Hannah-Jones reports on a school district that accidentally stumbled on an integration program in recent years. It's the Normandy School District in Normandy, Missouri. Normandy is on the border of Ferguson, Missouri, and the district includes the high school that Michael Brown attended. (30 minutes)

You are now inside the museum. Click on the painting to start discovering the document. Now, take a seat to study the document. The problem we all live with, Norman Rockwell, 1964. The problem we all live with, Norman Rockwell, 1964. The problem we all live with, Norman Rockwell, 1964. The problem we all live with, Norman Rockwell, 1964. Finish.

by carmel. The Problem We All Live With. 11. 10. the conclusion /la conclusion. analyse its composite / analyse sa composition. describe this painting /décrire le tableau. identify its origin/indentifier ses origines. somaire/sommary.

The problem we all live with. Created in 1964 by norman rockwell; This work is an oil painting of 91.4 × 147.3 cm; it is not exposed because it is part of the private collection

The Problem We All Live With for Look magazine is based upon an actual event, in 1960, when six-year-old Ruby Bridges was escorted by US marshals to her first day at an all-white New Orleans school. Rockwell's depiction of the vulnerable but dignified girl clearly condemns the actions of those who protest her presence and object to desegregation.

The first thing that stands out in "The Problem We All Live With" is its focal point: the girl. She is positioned slightly left of center but balanced by the large, red splotch on the wall right of center. Rockwell took artistic license with her pristine white dress, hair ribbon, shoes, and socks (Ruby Bridges was wearing a plaid dress and ...

Conclusion. Norman Rockwell's "The Problem We All Live With" is not just a painting; it shows the guts and courage of the people who fought for equality and justice. In his art, Rockwell elucidates the grotesque reality of racism as well as the indomitability of the human spirit. It has become almost a symbol of this never-ending battle ...

We all remember the case of Ruby Bridges, the first black child to enter a white school. The painter already known for his paintings too much in favor of blacks still makes talk of him. Rockwell's new shock paint ? NEWS PAPER. Ruby Bridges with US Marshals in 1960. Norman Rockwell, The Problem We All Live With, 1964