The Politics Shed- A Free Text Book for all students of Politics.

Dual Presidency Theory

The Dual Presidency Theory (also sometimes referred to as the ' Two Presidencies Thesis ') is a theory proposed by the political scientist Aaron Wildavsky during the Cold War. Influenced by the time period of 1946-1964, the Dual Presidency Theory is based on the principle that there are two versions of the American President: one who is concerned with domestic policy and one concerned with foreign policy. Wildavsky makes the claim that Presidents would prefer to focus foremost on foreign policy because he is granted more traditional, constitutional, and statutory authority when compared to his domestic policy powers. Wildavsky argues that presidents have assumed a more active role with regards to foreign policy because they are able to act more quickly than the United States Congress when pursuing foreign policy. Also, a lack of interest groups active in foreign policy allow the president more discretion when making a decision.

However, since Wildavsky's time, the domestic impact of foreign policy has become more pronounced and important, blurring the lines between foreign and domestic affairs. Politics no longer stop at the waters edge because Congress receives more reliable information on foreign affairs. Foreign policy is very much controlled by partisan politics in the United States today. Presidents no longer may take the liberty to assume public support for his foreign policy initiatives and must strive to build and maintain domestic support for them instead.

Aaron Wildavsky

The two presidencies.

Wildavsky, Aaron. "The Two Presidencies," Trans-Action/Society, 4 (1966): 7-14.

“The United States has one president, but it has two presidencies; one presidency is for domestic affairs, and the other is concerned with defense and foreign policy. Since World War II, presidents have had greater success in controlling the nation’s defense and foreign policies than in dominating its domestic policies. Even Lyndon Johnson has seen his early record of victories in domestic legislation diminish as his concern with foreign affairs grows.

What powers does the president have to control defense and foreign policies and so completely overwhelm those who might wish to thwart him?

The president’s normal problem with domestic policy is to get congressional support for programs he prefers. In foreign affairs, in contrast, he can almost always get support for policies that he believes will protect the nation – but his problem is to find a viable policy.”

Online: U Chicago Archives [pdf]

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

A Historical Reassessment of Wildavsky's 'Two Presidencies' Thesis

Social Science Quarterly, 1982: 549-555

Related Papers

Presidential Studies Quarterly

Scot Schraufnagel

Aaron Wildavsky first proposed that presidents in the United States receive more support from Congress in foreign policy and thus can expect to wield more influence and discretion in this policy arena. Since that time, scholars have scrutinized Wildavsky's contention. A recent work by Fleisher et al., using a new measure of presidential support, argues convincingly that broad generalizations about the phenomenon of increased presidential support in foreign policy must be drawn tentatively. This article addresses the two-presidencies thesis in three ways. First, the authors replicate a portion of Edwards's research to illustrate the reliability of our results. Second, the authors extend the data collection on more traditional measures used to test this thesis. Third, to address the issue of intermestic policy, the authors employ a new measure of presidential support that more carefully defines foreign and domestic policy actions. The analyses confirm the findings of Fleishe...

Matthew Caverly

This paper examines presidential-congressional relations in foreign affairs by utilizing issue area and political time analyses. The theory proposed is the multiple presidencies thesis, a more nuanced updating of the founding work on the " two presidencies " by Aaron Wildavsky (1966). I suggest that between the presidency and the Congress a high politics arena characterized by presidency-centered conditions favors securitization and greater presidential dominance vis-à-vis the Congress. The low politics arena is characterized by Congress-centered conditions which favor domesticization and greater congressional penetration relative to the presidency. Both are subject to the vagaries of history which amount to a structuring element on the conduct of the inter-institutional relationship. I test this theory by conducting presidential roll call analyses on foreign policy issue areas. The findings support the issue area schema and show that political time is a factor in the executive-legislative construction of foreign policies.

American Politics Research

Richard Fleisher

The Multiple Presidencies Thesis

An examination into the presidential-congressional policy construction process throughout the issue areas of foreign policy and across the periods of political time.

In this paper, I present evidence from a meta-analysis of one of the most dominant theoretical perspectives in executive-legislative policy making relations—Aaron Wildavsky's (1966) two presidencies thesis. Wildavsky's work suggested that no less than two policy making presidencies existed within a single president's relationship with the Congress (1966). Furthermore, that while the president " dominated " the construction of policies in foreign affairs vis-à-vis the Congress; he was impeded in that effort in the realm of domestic politics (1966). After Wildavsky's work was published no less than an entire school of academic thought grew up around the idea and inherent possibilities of a " two presidencies thesis " (Shull 1991). It is my intention in this analysis to examine that body of literature and report on its general conclusions relative to the existence of and subsequent evolution of the two presidencies as an intellectual endeavor. My findings indicate that the two presidencies is subject to examination within institutional, methodological and partisan terms and from that an adequate theoretical, empirical and normative critique can be developed which is the finished project of this paper. As an empirical theory, the two presidencies is rather strongly support with a support rate among two presidency researchers of 62.5%. The strongest level for the explanatory existence of the two presidencies comes from Wildavsky's classic institutional (Wildavsky 1966) version and the strongest reason for rejection of the two presidencies comes from its notion as a " cultural phenomenon " (Peppers 1975). Despite wide spread discussion within the literature there is little evidence to support a strictly partisan version of the thesis probably due to its lack of clear association between itself and either support or refutation of the thesis. (see Edwards 1986). Methodologically, the two presidencies has some association between the employment of an aggregate level of analysis and the institutional explanation, however, while some qualitative evidence exists for such a relationship between the employment of an individual level of analysis and the partisan version of the two presidencies no such relationship is corroborated quantitatively. Also, the cultural version of the theory is associated at least through the qualitative meta-analysis with the employment of qualitative methods; this relationship does not appear in the quantitative portion of the meta-analysis. Finally, the lack of normative study either as a critique of executive-legislative relations or as a reflexive commentary on the body of research itself holds the two presidencies back from fulfilling a broader promise regarding American political analysis. Lastly, the need for re-theorization is necessitated by the conclusions of this meta-analysis because the two presidencies as it currently exists is not developed enough to truly get at the " heart of the executive-legislative policy making divide. " A more nuanced approach is needed to provide greater empirical " fit, " provide stronger explanative/ predictive " power, " and establish a normative " critique " as to the appropriateness of presidential prerogatives and congressional involvement in foreign and domestic policy making.

One of the central debates within American foreign policy scholarship revolves around the theoretical concept used in determining the “dominant force” regarding the actual construction of such policies. Two theoretical lenses have been presented to account for the above; the first emanates out of the realist paradigm and suggests a “state-centrist” orientation for policy formulation (see Morgenthau, 1993 and Alison and Zelikow, 1999). The second such lens employed by IR scholars in American foreign policy research is associated with the idealist paradigm and embodies a “domestic variables” approach to the study of policy making in foreign affairs (see Gourevitch, 1996 and again Alison and Zelikow, 1999). The statist or state-centrist formulation posits that the state is best viewed as a unitary actor projecting itself as a unified political entity onto the international system or as an agent reacting to that system (Morgenthau 1993 and Waltz 1979). Regarding foreign policy creation, this framework stresses the role of the “core foreign policy executive” in determining and enacting the “national interest” (Krasner 1987 for an economic application and Kissinger 1994 for a number of diplomatic/military applications). The domestic variables conception, on the other hand, posits that states are “conglomerations of interests” interacting with themselves and the international system of which they are a part (Gourevitch, 1978 and 1996). Under this articulation, foreign policy is the by-product of a complex system of interrelationships between a varying mix of actors under conditions approximating pluralism and emphasizing the inherent connections of the principals involved (Keohane and Nye, 1977; Fearon, 1994; Rogowski, 1989; Snyder, 1991; and Putnam, 1988 for types of applications). Accordingly, in this study, I present a theoretical-methodological alternative to the above accounts which I believe captures the inherent “nuances” of the real world conditions which foreign policy construction occurs in (at least as far as the American case is concerned). Therefore, I propose that foreign policy construction is best analyzed through an “issue areas” perspective that examines each of the “sets” of issue areas contained within foreign affairs including trade, aid, immigration and security. Furthermore, I suggest that within these “sets” of foreign policy issue areas internal categorical differences pervade like for instance various “types” of foreign aid including economic, military and humanitarian. A study of these issue areas as separate and only loosely interrelated “categories of foreign policy” will offer a truer “picture” as to how foreign policy is “actually” constructed rather than the “cookie-cutter one size fits all” statist and domestic variables applications to a single category presentation of “foreign policy.” To test my thesis I employed a roll call analysis of political determinants including partisan/ideological, popular and electoral factors on annual presidential position success rates vis-à-vis the Congress in the appropriate foreign issue area categories for the Eisenhower-W. Bush presidencies. The results reveal that the answer to the state-centrism vs. domestic variables approach “question” is found in the Aristotelian “Golden Mean.” In that, those issue areas that are of a security nature and/or successfully “securitized” as such state-centrist approaches are best for understanding the foreign policy construction process. However, in those issue areas that are of a more “domesticated” nature (meaning that they have a high level of interaction with domestic policy groups like non-security/ non-securitized aid, trade and immigration) a domestic variables perspective is most appropriately employed. Regarding the specifics inherent within the multiple presidencies of presidential-congressional relations, partisan and to a lesser extent ideological factors are more predictive of foreign affairs outcomes at least as measured by the annual presidential success rates across the main issue areas of concern. The implications of such findings are that they can tell us a lot about the “real world” of foreign policy rather than the “constructed” realm established by over simplified methods and theories. Another implication is in the employment of “synthesizing approaches” which attempt to take what is best from the existing scholarship and reject what is worst in it. Also, the marriage of two competing theoretical frameworks from competing paradigms suggests that future research in world politics could benefit from more “mixed theoretical and perhaps even paradigmatic perspectives” which conceivably could lead to a greater mutual respect for ideas that on the surface may seem irreconcilable.

The Multiple Presidencies Thesis: Presidential-Congressional Foreign Policy Relations across Issues Areas and Political Time

Chapter 4 of the book published by VDM, this sample chapter lays out the empirical theory I developed in order to explain the foreign policy construction process. An inter-institutional policy making procedure shared between the president and the Congress via the component issue areas of foreign affairs across the vagaries of a politicized conception of historical time.

Southeastern Political Review

Glenn Hastedt , Anthony Eksterowicz

Maxwell Fuerderer

RELATED PAPERS

karen muñoz

Samrat Mehra

IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science

Agustan Agustan

Apuntes de …

Rafael Gómez del Toro

Chemical Physics Letters

William Green

A Georges L Romme

Journal of Cardiology Cases

Naofumi F Sumitomo

Applied Composite Materials

MARCIO EDUARDO SILVEIRA

mitch toñon

买新英格兰大学毕业证书成绩单 澳洲UNE文凭学位证书

Environmental Pollution

Andrew Ghio

Farkhod Fazilov

Rabbi Menachem Levine

Daniela E . Chazarreta

Zohra Lakhdar

Jual Sarung Kursi

LSE毕业证成绩单 bvgde

Scientific Reports

Nigar Ahmadova

Implementation Science

Simone Rosenblum

Physica E: Low-dimensional Systems and Nanostructures

Guillermo Cabrera

Carlos Reina

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 17: Foreign Policy

17.3 Institutional Relations in Foreign Policy

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the use of shared power in U.S. foreign policymaking

- Explain why presidents lead more in foreign policy than in domestic policy

- Discuss why individual House and Senate members rarely venture into foreign policy

- List the actors who engage in foreign policy

Introduction

Institutional relationships in foreign policy constitute a paradox. On the one hand, there are aspects of foreign policymaking that necessarily engage multiple branches of government and a multiplicity of actors. Indeed, there is a complexity to foreign policy that is bewildering, in terms of both substance and process. On the other hand, foreign policymaking can sometimes call for nothing more than for the president to make a formal decision, quickly endorsed by the legislative branch. This section will explore the institutional relationships present in U.S. foreign policymaking.

FOREIGN POLICY AND SHARED POWER

While presidents are more empowered by the Constitution in foreign than in domestic policy, they nonetheless must seek approval from Congress on a variety of matters; chief among these is the basic budgetary authority needed to run foreign policy programs. Indeed, most if not all of the foreign policy instruments described earlier in this chapter require interbranch approval to go into effect. Such approval may sometimes be a formality, but it is still important. Even a sole executive agreement often requires subsequent funding from Congress in order to be carried out, and funding calls for majority support from the House and Senate. Presidents lead, to be sure, but they must consult with and engage the Congress on many matters of foreign policy. Presidents must also delegate a great deal in foreign policy to the bureaucratic experts in the foreign policy agencies. Not every operation can be run from the West Wing of the White House.

At bottom, the United States is a separation-of-powers political system with authority divided among executive and legislative branches, including in the foreign policy realm. Table shows the formal roles of the president and Congress in conducting foreign policy.

The main lesson of Table is that nearly all major outputs of foreign policy require a formal congressional role in order to be carried out. Foreign policy might be done by executive say-so in times of crisis and in the handful of sole executive agreements that actually pertain to major issues (like the Iran Nuclear Agreement). In general, however, a consultative relationship between the branches in foreign policy is the usual result of their constitutional sharing of power. A president who ignores Congress on matters of foreign policy and does not keep them briefed may find later interactions on other matters more difficult. Probably the most extreme version of this potential dynamic occurred during the Eisenhower presidency. When President Dwight D. Eisenhower used too many executive agreements instead of sending key ones to the Senate as treaties, Congress reacted by considering a constitutional amendment (the Bricker Amendment ) that would have altered the treaty process as we know it. Eisenhower understood the message and began to send more agreements through the process as treaties. [1]

Shared power creates an incentive for the branches to cooperate. Even in the midst of a crisis, such as the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, it is common for the president or senior staff to brief congressional leaders in order to keep them up to speed and ensure the country can stand unified on international matters. That said, there are areas of foreign policy where the president has more discretion, such as the operation of intelligence programs, the holding of foreign policy summits, and the mobilization of troops or agents in times of crisis. Moreover, presidents have more power and influence in foreign policymaking than they do in domestic policymaking. It is to that power that we now turn.

THE TWO PRESIDENCIES THESIS

When the media cover a domestic controversy, such as social unrest or police brutality, reporters consult officials at different levels and in branches of government, as well as think tanks and advocacy groups. In contrast, when an international event occurs, such as a terrorist bombing in Paris or Brussels, the media flock predominately to one actor—the president of the United States—to get the official U.S. position.

In the realm of foreign policy and international relations, the president occupies a leadership spot that is much clearer than in the realm of domestic policy. This dual domestic and international role has been described by the two presidencies thesis . This theory originated with University of California–Berkeley professor Aaron Wildavsky and suggests that there are two distinct presidencies, one for foreign policy and one for domestic policy, and that presidents are more successful in foreign than domestic policy. Let’s look at the reasoning behind this thesis.

The Constitution names the president as the commander-in-chief of the military, the nominating authority for executive officials and ambassadors, and the initial negotiator of foreign agreements and treaties. The president is the agenda-setter for foreign policy and may move unilaterally in some instances. Beyond the Constitution, presidents were also gradually given more authority to enter into international agreements without Senate consent by using the executive agreement. We saw above that the passage of the War Powers Resolution in 1973, though intended as a statute to rein in executive power and reassert Congress as a check on the president, effectively gave presidents two months to wage war however they wish. Given all these powers, we have good reason to expect presidents to have more influence and be more successful in foreign than in domestic policy.

A second reason for the stronger foreign policy presidency has to do with the informal aspects of power. In some eras, Congress will be more willing to allow the president to be a clear leader and speak for the country. For instance, the Cold War between the Eastern bloc countries (led by the Soviet Union) and the West (led by the United States and Western European allies) prompted many to want a single actor to speak for the United States. A willing Congress allowed the president to take the lead because of urgent circumstances. Much of the Cold War also took place when the parties in Congress included more moderates on both sides of the aisle and the environment was less partisan than today. A phrase often heard at that time was, “Partisanship stops at the water’s edge.” This means that foreign policy matters should not be subject to the bitter disagreements seen in party politics.

Does the thesis’s expectation of a more successful foreign policy presidency apply today? While the president still has stronger foreign policy powers than domestic powers, the governing context has changed in two key ways. First, the Cold War ended in 1989 with the demolition of the Berlin Wall, the subsequent disintegration of the Soviet Union, and the eventual opening up of Eastern European territories to independence and democracy. These dramatic changes removed the competitive superpower aspect of the Cold War, in which the United States and the USSR were dueling rivals on the world stage. The absence of the Cold War has led to less of a rally-behind-the-president effect in the area of foreign policy.

Second, beginning in the 1980s and escalating in the 1990s, the Democratic and Republican parties began to become polarized in Congress. The moderate members in each party all but disappeared, while more ideologically motivated candidates began to win election to the House and later the Senate. Hence, the Democrats in Congress became more liberal on average, the Republicans became more conservative, and the moderates from each party, who had been able to work together, were edged out. It became increasingly likely that the party opposite the president in Congress might be more willing to challenge his initiatives, whereas in the past it was rare for the opposition party to publicly stand against the president in foreign policy.

Finally, several analysts have tried applying the two presidencies thesis to contemporary presidential-congressional relationships in foreign policy. Is the two presidencies framework still valid in the more partisan post–Cold War era? The answer is mixed. On the one hand, presidents are more successful on foreign policy votes in the House and Senate, on average, than on domestic policy votes. However, the gap has narrowed. Moreover, analysis has also shown that presidents are opposed more often in Congress, even on the foreign policy votes they win. [2] Democratic leaders regularly challenged Republican George W. Bush on the Iraq War and it became common to see the most senior foreign relations committee members of the Republican Party opposing the foreign policy positions of Democratic president Barack Obama. Such challenging of the president by the opposition party simply didn’t happen during the Cold War.

Therefore, it seems presidents no longer enjoy unanimous foreign policy support as they did in the early 1960s. They have to work harder to get a consensus and are more likely to face opposition. Still, because of their formal powers in foreign policy, presidents are overall more successful on foreign policy than on domestic policy.

THE PERSPECTIVE OF HOUSE AND SENATE MEMBERS

Congress is a bicameral legislative institution with 100 senators serving in the Senate and 435 representatives serving in the House. How interested in foreign policy are typical House and Senate members?

While key White House, executive, and legislative leaders monitor and regularly weigh in on foreign policy matters, the fact is that individual representatives and senators do so much less often. Unless there is a foreign policy crisis, legislators in Congress tend to focus on domestic matters, mainly because there is not much to be gained with their constituents by pursuing foreign policy matters. [3] Domestic policy matters resonate more strongly with the voters at home. A sluggish economy, increasing health care costs, and crime matter more to them than U.S. policy toward North Korea, for example. In an open-ended Gallup poll question from early 2016 about the “most important problem” in the United States, fewer than 15 percent of respondents named a foreign policy topic (half of those respondents mentioned immigration). These results suggest that foreign policy is not at the top of many voters’ minds. In the end, legislators must be responsive to constituents in order to be good representatives and to achieve reelection [4]

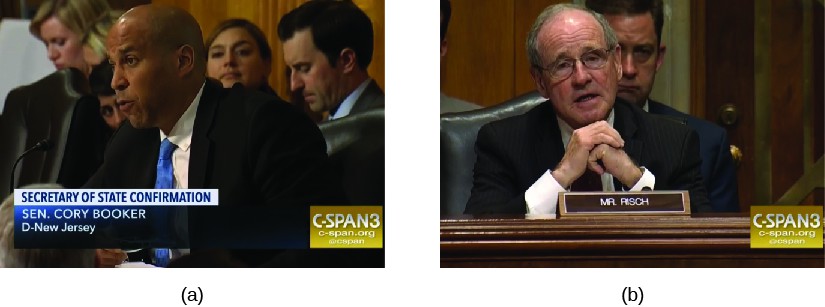

However, some House and Senate members do wade into foreign policy matters. First, congressional party leaders in the majority and minority parties speak on behalf of their institution and their party on all types of issues, including foreign policy. Some House and Senate members ask to serve on the foreign policy committees, such as the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations , the House Foreign Affairs Committee , and the two defense committees. These members might have military bases within their districts or states and hence have a constituency reason for being interested in foreign policy. Legislators might also simply have a personal interest in foreign policy matters that drives their engagement in the issue. Finally, they may have ambitions to move into an executive branch position that deals with foreign policy matters, such as secretary of state or defense, CIA director, or even president.

LET PEOPLE KNOW WHAT YOU THINK!

Most House and Senate members do not engage in foreign policy because there is no electoral benefit to doing so. Thus, when citizens become involved, House members and senators will take notice. Research by John Kingdon on roll-call voting and by Richard Hall on committee participation found that when constituents are activated, their interest becomes salient to a legislator and he or she will respond. [5]

One way you can become active in the foreign policy realm is by writing a letter or e-mail to your House member and/or your two U.S. senators about what you believe the U.S. foreign policy approach in a particular area ought to be. Perhaps you want the United States to work with other countries to protect dolphins from being accidentally trapped in tuna nets. You can also state your position in a letter to the editor of your local newspaper, or post an opinion on the newspaper’s website where a related article or op-ed piece appears. You can share links to news coverage on Facebook or Twitter and consider joining a foreign policy interest group such as Greenpeace.

When you engaged in foreign policy discussion as suggested above, what type of response did you receive?

THE MANY ACTORS IN FOREIGN POLICY

A variety of actors carry out the various and complex activities of U.S. foreign policy: White House staff, executive branch staff, and congressional leaders.

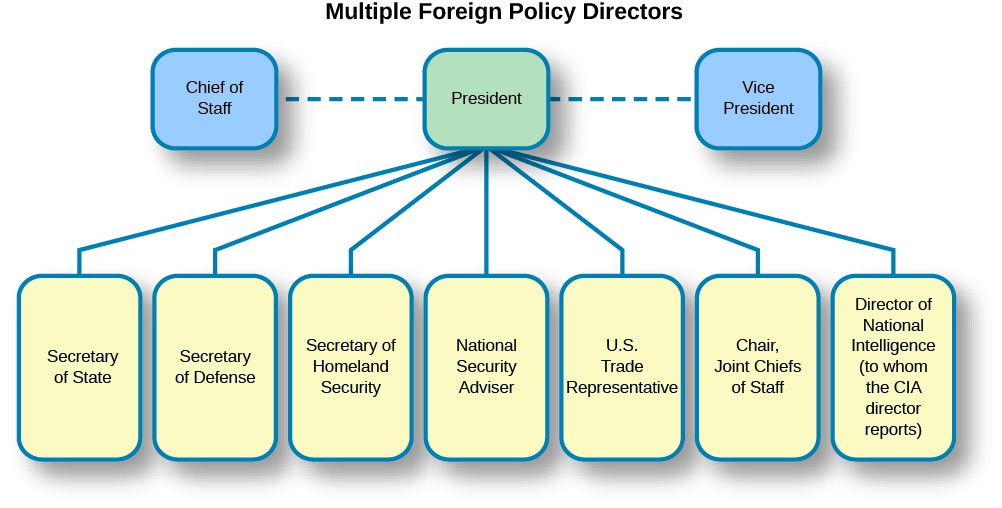

The White House staff members engaged in foreign policy are likely to have very regular contact with the president about their work. The national security advisor heads the president’s National Security Council , a group of senior-level staff from multiple foreign policy agencies, and is generally the president’s top foreign policy advisor. Also reporting to the president in the White House is the director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Even more important on intelligence than the CIA director is the director of national intelligence, a position created in the government reorganizations after 9/11, who oversees the entire intelligence community in the U.S. government. The Joint Chiefs of Staff consist of six members, one each from the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines, plus a chair and vice chair. The chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff is the president’s top uniformed military officer. In contrast, the secretary of defense is head of the entire Department of Defense but is a nonmilitary civilian. The U.S. trade representative develops and directs the country’s international trade agenda. Finally, within the Executive Office of the President , another important foreign policy official is the director of the president’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB). The OMB director develops the president’s yearly budget proposal, including funding for the foreign policy agencies and foreign aid.

In addition to those who work directly in the White House or Executive Office of the President, several important officials work in the broader executive branch and report to the president in the area of foreign policy. Chief among these is the secretary of state. The secretary of state is the nation’s chief diplomat, serves in the president’s cabinet, and oversees the Foreign Service. The secretary of defense, who is the civilian (nonmilitary) head of the armed services housed in the Department of Defense , is also a key cabinet member for foreign policy (as mentioned above). A third cabinet secretary, the secretary of homeland security, is critically important in foreign policy, overseeing the massive Department of Homeland Security .

FORMER SECRETARY OF DEFENSE ROBERT GATES

Former secretary of defense Robert Gates served under both Republican and Democratic presidents. First Gates rose through the ranks of the CIA to become the director during the George H. W. Bush administration. He then left government to serve as an academic administrator at Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas, where he rose to the position of university president. He was able to win over reluctant faculty and advance the university’s position, including increasing the faculty at a time when budgets were in decline in Texas. Then, when Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld resigned, President George W. Bush invited Gates to return to government service as Rumsfeld’s replacement. Gates agreed, serving in that capacity for the remainder of the Bush years and then for several years in the Obama administration before retiring from government service a second time. He has generally been seen as thorough, systematic, and fair.

In his memoir, Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary at War , [6] Secretary Gates takes issue with the actions of both the presidents for whom he worked, but ultimately he praises them for their service and for upholding the right principles in protecting the United States and U.S. military troops. In this and earlier books, Gates discusses the need to have an overarching plan but says plans cannot be too tight or they will fail when things change in the external environment. After leaving politics, Gates served as president of the Boy Scouts of America, where he presided over the change in policy that allowed openly gay scouts and leaders, an issue with which he had had experience as secretary of defense under President Obama. In that role Gates oversaw the end of the military’s “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. [7]

What do you think about a cabinet secretary serving presidents from two different political parties? Is this is a good idea? Why or why not?

The final group of official key actors in foreign policy are in the U.S. Congress. The Speaker of the House, the House minority leader, and the Senate majority and minority leaders are often given updates on foreign policy matters by the president or the president’s staff. They are also consulted when the president needs foreign policy support or funding. However, the experts in Congress who are most often called on for their views are the committee chairs and the highest-ranking minority members of the relevant House and Senate committees. In the House, that means the Foreign Affairs Committee and the Committee on Armed Services. In the Senate, the relevant committees are the Committee on Foreign Relations and the Armed Services Committee. These committees hold regular hearings on key foreign policy topics, consider budget authorizations, and debate the future of U.S. foreign policy.

Many aspects of foreign policymaking rely on the powers shared between Congress and the president, including foreign policy appointments and the foreign affairs budget. Within the executive branch, an array of foreign policy leaders report directly to the president. Foreign policy can at times seem fragmented and diffuse because of the complexity of actors and topics. However, the president is clearly the leader, having both formal authority and the ability to delegate to Congress, as explained in the two presidencies thesis. With this leadership, presidents at times can make foreign policymaking quick and decisive, especially when it calls for executive agreements and the military use of force.

- Krutz and Peake. Treaty Politics and the Rise of Executive Agreements . ↵

- Jon Bond, Richard Fleisher, Stephen Hanna, and Glen S. Krutz. 2000. “The Demise of the. Two Presidencies,” American Politics Quarterly 28, No. 1: 3–25. ↵

- James M. McCormick. 2010. American Foreign Policy and Process, 5th ed. Boston: Wadsworth. ↵

- The Gallup Organization, “Most Important Problem,” http://www.gallup.com/poll/1675/most-important-problem.aspx (May 12, 2016). ↵

- John W. Kingdon. 1973. Congressmen’s Voting Decisions . New York: Harper & Row; Richard Hall. 1996. Participation in Congress. New Haven, CT: University of Yale Press. ↵

- Robert M. Gates. 2015. Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary at War. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ↵

- David A. Graham, “Robert Gates, America’s Unlikely Gay-Rights Hero,” The Atlantic, 28 July 2015. http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2015/07/robert-gates-boy-scouts-gay-leaders/399716/. ↵

American Government, 1st ed. by OpenStax, Rice University. is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

17.3 Institutional Relations in Foreign Policy

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe the use of shared power in U.S. foreign policymaking

- Explain why presidents lead more in foreign policy than in domestic policy

- Discuss why individual House and Senate members rarely venture into foreign policy

- List the actors who engage in foreign policy

Institutional relationships in foreign policy constitute a paradox. On the one hand, there are aspects of foreign policymaking that necessarily engage multiple branches of government and a multiplicity of actors. Indeed, there is a complexity to foreign policy that is bewildering, in terms of both substance and process. On the other hand, foreign policymaking can sometimes call for nothing more than for the president to make a formal decision, quickly endorsed by the legislative branch. This section will explore the institutional relationships present in U.S. foreign policymaking.

FOREIGN POLICY AND SHARED POWER

While presidents are more empowered by the Constitution in foreign than in domestic policy, they nonetheless must seek approval from Congress on a variety of matters; chief among these is the basic budgetary authority needed to run foreign policy programs. Indeed, most if not all of the foreign policy instruments described earlier in this chapter require interbranch approval to go into effect. Such approval may sometimes be a formality, but it is still important. Even a sole executive agreement often requires subsequent funding from Congress in order to be carried out, and funding calls for majority support from the House and Senate. Presidents lead, to be sure, but they must consult with and engage the Congress on many matters of foreign policy. Presidents must also delegate a great deal in foreign policy to the bureaucratic experts in the foreign policy agencies. Not every operation can be run from the West Wing of the White House.

At bottom, the United States is a separation-of-powers political system with authority divided among executive and legislative branches, including in the foreign policy realm. Table 17.1 shows the formal roles of the president and Congress in conducting foreign policy.

The main lesson of Table 17.1 is that nearly all major outputs of foreign policy require a formal congressional role in order to be carried out. Foreign policy might be done by executive say-so in times of crisis and in the handful of sole executive agreements that actually pertain to major issues (like the Iran Nuclear Agreement). In general, however, a consultative relationship between the branches in foreign policy is the usual result of their constitutional sharing of power. A president who ignores Congress on matters of foreign policy and does not keep them briefed may find later interactions on other matters more difficult. Probably the most extreme version of this potential dynamic occurred during the Eisenhower presidency. When President Dwight D. Eisenhower used too many executive agreements instead of sending key ones to the Senate as treaties, Congress reacted by considering a constitutional amendment (the Bricker Amendment ) that would have altered the treaty process as we know it. Eisenhower understood the message and began to send more agreements through the process as treaties. 10

Shared power creates an incentive for the branches to cooperate. Even in the midst of a crisis, such as the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, it is common for the president or senior staff to brief congressional leaders in order to keep them up to speed and ensure the country can stand unified on international matters. That said, there are areas of foreign policy where the president has more discretion, such as the operation of intelligence programs, the holding of foreign policy summits, and the mobilization of troops or agents in times of crisis. Moreover, presidents have more power and influence in foreign policymaking than they do in domestic policymaking. It is to that power that we now turn.

THE TWO PRESIDENCIES THESIS

When the media cover a domestic controversy, such as social unrest or police brutality, reporters consult officials at different levels and in branches of government, as well as think tanks and advocacy groups. In contrast, when an international event occurs, such as a terrorist bombing in Paris or Brussels, the media flock predominately to one actor—the president of the United States—to get the official U.S. position.

In the realm of foreign policy and international relations, the president occupies a leadership spot that is much clearer than in the realm of domestic policy. This dual domestic and international role has been described by the two presidencies thesis . This theory originated with University of California–Berkeley professor Aaron Wildavsky and suggests that there are two distinct presidencies, one for foreign policy and one for domestic policy, and that presidents are more successful in foreign than domestic policy. Let’s look at the reasoning behind this thesis.

The Constitution names the president as the commander-in-chief of the military, the nominating authority for executive officials and ambassadors, and the initial negotiator of foreign agreements and treaties. The president is the agenda-setter for foreign policy and may move unilaterally in some instances. Beyond the Constitution, presidents were also gradually given more authority to enter into international agreements without Senate consent by using the executive agreement. We saw above that the passage of the War Powers Resolution in 1973, though intended as a statute to rein in executive power and reassert Congress as a check on the president, effectively gave presidents two months to wage war however they wish. Given all these powers, we have good reason to expect presidents to have more influence and be more successful in foreign than in domestic policy.

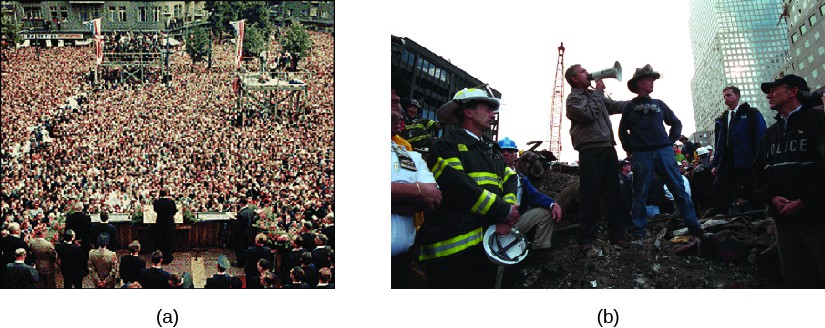

A second reason for the stronger foreign policy presidency has to do with the informal aspects of power. In some eras, Congress will be more willing to allow the president to be a clear leader and speak for the country. For instance, the Cold War between the Eastern bloc countries (led by the Soviet Union) and the West (led by the United States and Western European allies) prompted many to want a single actor to speak for the United States. A willing Congress allowed the president to take the lead because of urgent circumstances ( Figure 17.12 ). Much of the Cold War also took place when the parties in Congress included more moderates on both sides of the aisle and the environment was less partisan than today. A phrase often heard at that time was, “Partisanship stops at the water’s edge.” This means that foreign policy matters should not be subject to the bitter disagreements seen in party politics.

Does the thesis’s expectation of a more successful foreign policy presidency apply today? While the president still has stronger foreign policy powers than domestic powers, the governing context has changed in two key ways. First, the Cold War ended in 1989 with the demolition of the Berlin Wall, the subsequent disintegration of the Soviet Union, and the eventual opening up of Eastern European territories to independence and democracy. These dramatic changes removed the competitive superpower aspect of the Cold War, in which the United States and the USSR were dueling rivals on the world stage. The absence of the Cold War has led to less of a rally-behind-the-president effect in the area of foreign policy.

Second, beginning in the 1980s and escalating in the 1990s, the Democratic and Republican parties began to become polarized in Congress. The moderate members in each party all but disappeared, while more ideologically motivated candidates began to win election to the House and later the Senate. Hence, the Democrats in Congress became more liberal on average, the Republicans became more conservative, and the moderates from each party, who had been able to work together, were edged out. It became increasingly likely that the party opposite the president in Congress might be more willing to challenge his initiatives, whereas in the past it was rare for the opposition party to publicly stand against the president in foreign policy.

Finally, several analysts have tried applying the two presidencies thesis to contemporary presidential-congressional relationships in foreign policy. Is the two presidencies framework still valid in the more partisan post–Cold War era? The answer is mixed. On the one hand, presidents are more successful on foreign policy votes in the House and Senate, on average, than on domestic policy votes. However, the gap has narrowed. Moreover, analysis has also shown that presidents are opposed more often in Congress, even on the foreign policy votes they win. 11 Democratic leaders regularly challenged Republican George W. Bush on the Iraq War and it became common to see the most senior foreign relations committee members of the Republican Party opposing the foreign policy positions of Democratic president Barack Obama. Such challenging of the president by the opposition party simply didn’t happen during the Cold War.

In the Trump administration, there was a distinct shift in foreign policy style. While for some regions, like South America, Trump was content to let the foreign policy bureaucracies proceed as they always had, in certain areas, the president was pivotal in changing the direction of American foreign policy. For example, he stepped away from two key international agreements—the Iran-Nuclear Deal and the Paris climate change accords. Moreover, his actions in Syria were quite unilateral, employing bombing raids unilaterally on two occasions. This approach reflected more of a neoconservative foreign policy approach, similar to Obama's widespread use of drone strikes.

Therefore, it seems presidents no longer enjoy unanimous foreign policy support as they did in the early 1960s. They have to work harder to get a consensus and are more likely to face opposition. Still, because of their formal powers in foreign policy, presidents are overall more successful on foreign policy than on domestic policy.

THE PERSPECTIVE OF HOUSE AND SENATE MEMBERS

Congress is a bicameral legislative institution with 100 senators serving in the Senate and 435 representatives serving in the House. How interested in foreign policy are typical House and Senate members?

While key White House, executive, and legislative leaders monitor and regularly weigh in on foreign policy matters, the fact is that individual representatives and senators do so much less often. Unless there is a foreign policy crisis, legislators in Congress tend to focus on domestic matters, mainly because there is not much to be gained with their constituents by pursuing foreign policy matters. 12 Domestic policy matters resonate more strongly with the voters at home. A sluggish economy, increasing health care costs, and crime matter more to them than U.S. policy toward North Korea, for example. In an open-ended Gallup poll question from early 2021 about the “most important problem” in the United States, fewer than 10 percent of respondents named a foreign policy topic (and most of those respondents mentioned immigration). These results suggest that foreign policy is not at the top of many voters’ minds. In the end, legislators must be responsive to constituents in order to be good representatives and to achieve reelection. 13

However, some House and Senate members do wade into foreign policy matters. First, congressional party leaders in the majority and minority parties speak on behalf of their institution and their party on all types of issues, including foreign policy. Some House and Senate members ask to serve on the foreign policy committees, such as the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations , the House Foreign Affairs Committee , and the two defense committees ( Figure 17.13 ). These members might have military bases within their districts or states and hence have a constituency reason for being interested in foreign policy. Legislators might also simply have a personal interest in foreign policy matters that drives their engagement in the issue. Finally, they may have ambitions to move into an executive branch position that deals with foreign policy matters, such as secretary of state or defense, CIA director, or even president.

Get Connected!

Let people know what you think.

Most House and Senate members do not engage in foreign policy because there is no electoral benefit to doing so. Thus, when citizens become involved, House members and senators will take notice. Research by John Kingdon on roll-call voting and by Richard Hall on committee participation found that when constituents are activated, their interest becomes salient to a legislator and the legislator will respond. 14

One way you can become active in the foreign policy realm is by writing a letter or e-mail to your House member and/or your two U.S. senators about what you believe the U.S. foreign policy approach in a particular area ought to be. Perhaps you want the United States to work with other countries to protect dolphins from being accidentally trapped in tuna nets. You can also state your position in a letter to the editor of your local newspaper, or post an opinion on the newspaper’s website where a related article or op-ed piece appears. You can share links to news coverage on Facebook or Twitter and consider joining a foreign policy interest group such as Greenpeace.

When you engaged in foreign policy discussion as suggested above, what type of response did you receive?

Link to Learning

For more information on the two key congressional committees on U.S. foreign policy, visit the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations and the House Foreign Affairs Committee websites.

THE MANY ACTORS IN FOREIGN POLICY

A variety of actors carry out the various and complex activities of U.S. foreign policy: White House staff, executive branch staff, and congressional leaders.

The White House staff members engaged in foreign policy are likely to have very regular contact with the president about their work. The national security advisor heads the president’s National Security Council , a group of senior-level staff from multiple foreign policy agencies, and is generally the president’s top foreign policy advisor. Also reporting to the president in the White House is the director of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Even more important on intelligence than the CIA director is the director of national intelligence, a position created in the government reorganizations after 9/11, who oversees the entire intelligence community in the U.S. government. The Joint Chiefs of Staff consist of six members, one each from the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines, plus a chair and vice chair. The chair of the Joint Chiefs of Staff is the president’s top uniformed military officer. In contrast, the secretary of defense is head of the entire Department of Defense but is a nonmilitary civilian. The U.S. trade representative develops and directs the country’s international trade agenda. Finally, within the Executive Office of the President , another important foreign policy official is the director of the president’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB). The OMB director develops the president’s yearly budget proposal, including funding for the foreign policy agencies and foreign aid.

In addition to those who work directly in the White House or Executive Office of the President, several important officials work in the broader executive branch and report to the president in the area of foreign policy. Chief among these is the secretary of state. The secretary of state is the nation’s chief diplomat, serves in the president’s cabinet, and oversees the Foreign Service. The secretary of defense, who is the civilian (nonmilitary) head of the armed services housed in the Department of Defense , is also a key cabinet member for foreign policy (as mentioned above). A third cabinet secretary, the secretary of homeland security, is critically important in foreign policy, overseeing the massive Department of Homeland Security ( Figure 17.14 ).

Insider Perspective

Former secretary of defense robert gates.

Former secretary of defense Robert Gates served under both Republican and Democratic presidents. First Gates rose through the ranks of the CIA to become the director during the George H. W. Bush administration. He then left government to serve as an academic administrator at Texas A&M University in College Station, Texas, where he rose to the position of university president. He was able to win over reluctant faculty and advance the university’s position, including increasing the faculty at a time when budgets were in decline in Texas. Then, when Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld resigned, President George W. Bush invited Gates to return to government service as Rumsfeld’s replacement. Gates agreed, serving in that capacity for the remainder of the Bush years and then for several years in the Obama administration before retiring from government service a second time ( Figure 17.15 ). He has generally been seen as thorough, systematic, and fair.

In his memoir, Duty: Memoirs of a Secretary at War , 15 Secretary Gates takes issue with the actions of both the presidents for whom he worked, but ultimately he praises them for their service and for upholding the right principles in protecting the United States and U.S. military troops. In this and earlier books, Gates discusses the need to have an overarching plan but says plans cannot be too tight or they will fail when things change in the external environment. After leaving politics, Gates served as president of the Boy Scouts of America, where he presided over the change in policy that allowed openly gay scouts and leaders, an issue with which he had had experience as secretary of defense under President Obama. In that role Gates oversaw the end of the military’s “Don’t ask, don’t tell” policy. 16

What do you think about a cabinet secretary serving presidents from two different political parties? Is this is a good idea? Why or why not?

The final group of official key actors in foreign policy are in the U.S. Congress. The Speaker of the House, the House minority leader, and the Senate majority and minority leaders are often given updates on foreign policy matters by the president or the president’s staff. They are also consulted when the president needs foreign policy support or funding. However, the experts in Congress who are most often called on for their views are the committee chairs and the highest-ranking minority members of the relevant House and Senate committees. In the House, that means the Foreign Affairs Committee and the Committee on Armed Services. In the Senate, the relevant committees are the Committee on Foreign Relations and the Armed Services Committee. These committees hold regular hearings on key foreign policy topics, consider budget authorizations, and debate the future of U.S. foreign policy.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/american-government-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Glen Krutz, Sylvie Waskiewicz, PhD

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: American Government 3e

- Publication date: Jul 28, 2021

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/american-government-3e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/american-government-3e/pages/17-3-institutional-relations-in-foreign-policy

© Jan 5, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

10.6: Institutional Relations in Foreign Policy

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 147683

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Institutional relationships in foreign policy constitute a paradox. On the one hand, there are aspects of foreign policymaking that necessarily engage multiple branches of government and a multiplicity of actors. Indeed, there is a complexity to foreign policy that is bewildering, in terms of both substance and process. On the other hand, foreign policymaking can sometimes call for nothing more than for the president to make a formal decision, quickly endorsed by the legislative branch.

Foreign Policy and Shared Power

While presidents are more empowered by the Constitution in foreign than in domestic policy, they must seek approval from Congress on a variety of matters; chief among these is the basic budgetary authority needed to run foreign policy programs. Even a sole executive agreement often requires subsequent funding from Congress in order to be carried out, and funding calls for majority support from the House and Senate. Presidents must consult with and engage Congress on many matters of foreign policy, and delegate a great deal to the bureaucratic experts in the foreign policy agencies. Not every operation can be run from the West Wing of the White House.

This chart shows the separation of powers and authority divided among executive and legislative branches, including in the foreign policy realm.

Nearly all major outputs of foreign policy require a formal congressional role in order to be carried out. Foreign policy might be done by executive say-so in times of crisis and in the handful of sole executive agreements that actually pertain to major issues (like the Iran Nuclear Agreement). In general, however, a consultative relationship between the branches in foreign policy is the usual result of their constitutional sharing of power.

Shared power creates an incentive for the branches to cooperate. Even in the midst of a crisis, such as the Cuban Missile Crisis in 1962, it is common for the president or senior staff to brief congressional leaders in order to keep them up to speed and ensure the country can stand unified on international matters. That said, there are areas of foreign policy where the president has more discretion, such as the operation of intelligence programs, the holding of foreign policy summits, and the mobilization of troops or agents in times of crisis. Moreover, presidents have more power and influence in foreign policymaking than they do in domestic policymaking.

The Two Presidencies Thesis

When the media cover a domestic controversy, such as social unrest or police brutality, reporters consult officials at different levels and in branches of government, as well as think tanks and advocacy groups. In contrast, when an international event occurs, such as a terrorist bombing in Paris or Brussels, the media flock predominately to one actor—the president of the United States—to get the official U.S. position.

The two presidencies thesis suggests that there are two distinct presidencies, one for foreign policy and one for domestic policy, and that presidents are more successful in foreign than domestic policy. Let’s look at the reasoning behind this thesis.

- The Constitution names the president as the commander-in-chief of the military, the nominating authority for executive officials and ambassadors, and the initial negotiator of foreign agreements and treaties. The president is the agenda-setter for foreign policy and may move unilaterally in some instances. Beyond the Constitution, presidents were also gradually given more authority to enter into international agreements without Senate consent by using the executive agreement. Laws, such as the War Powers Resolution of 1973, further promote this idea. Given all these powers, we have good reason to expect presidents to have more influence and be more successful in foreign than in domestic policy.

- The second reason has to do with the informal aspects of power. In some eras, Congress will be more willing to allow the president to be a clear leader and speak for the country. For instance, the Cold War between the Eastern bloc countries (led by the Soviet Union) and the West (led by the United States and Western European allies) prompted many to want a single actor to speak for the United States. A willing Congress allowed the president to take the lead because of urgent circumstances. In addition, the Cold War took place when the parties in Congress included more moderates on both sides of the aisle and the environment was less partisan than today. A phrase often heard at that time was, “Partisanship stops at the water’s edge.” This means that foreign policy matters should not be subject to the bitter disagreements seen in party politics.

Does the thesis’s expectation of a more successful foreign policy presidency apply today? While the president still has stronger foreign policy powers than domestic powers, the governing context has changed in two key ways. First, the Cold War ended in 1989 with the demolition of the Berlin Wall, the subsequent disintegration of the Soviet Union, and the eventual opening up of Eastern European territories to independence and democracy. These dramatic changes removed the competitive superpower aspect of the Cold War, in which the United States and the USSR were dueling rivals on the world stage. The absence of the Cold War has led to less of a rally-behind-the-president effect in the area of foreign policy.

Second, beginning in the 1980s and escalating in the 1990s, the Democratic and Republican parties began to become polarized in Congress. The moderate members in each party all but disappeared, while more ideologically motivated candidates began to win elections to the House and later the Senate. Hence, the Democrats in Congress became more liberal on average, the Republicans became more conservative, and the moderates from each party, who had been able to work together, were edged out. It became increasingly likely that the party opposite the president in Congress might be more willing to challenge his initiatives, whereas in the past it was rare for the opposition party to publicly stand against the president in foreign policy.

Finally, several analysts have tried applying the two presidencies thesis to contemporary presidential-congressional relationships in foreign policy. Is the two presidencies framework still valid in the more partisan post–Cold War era? The answer is mixed. On the one hand, presidents are more successful on foreign policy votes in the House and Senate, on average, than on domestic policy votes. However, the gap has narrowed. Moreover, analysis has also shown that presidents are opposed more often in Congress, even on the foreign policy votes they win. [2] Democratic leaders regularly challenged Republican George W. Bush on the Iraq War and it became common to see the most senior foreign relations committee members of the Republican Party opposing the foreign policy positions of Democratic president Barack Obama. Such challenging of the president by the opposition party simply didn’t happen during the Cold War.

During the Trump administration, there was been a distinct shift in foreign policy style. While for some regions, like South America, Trump was content to let the foreign policy bureaucracies proceed as they always have, in certain areas, the president has become quite pivotal in changing the direction of U.S. foreign policy. For example, he stepped away from two key international agreements—the Iran-Nuclear Deal and the Paris climate change accords. Moreover, in Syria, he employed bombing raids unilaterally on two occasions. This approach reflects more of a neoconservative foreign policy approach.

Therefore, it seems presidents no longer enjoy unanimous foreign policy support as they did in the early 1960s. They have to work harder to get a consensus and are more likely to face opposition. Still, because of their formal powers in foreign policy, presidents are overall more successful in foreign policy than in domestic policy.

The Perspective of House and Senate Members

Congress is a bicameral legislative institution with 100 senators serving in the Senate and 435 representatives serving in the House. How interested in foreign policy are typical House and Senate members?

Unless there is a foreign policy crisis, legislators in Congress tend to focus on domestic matters, mainly because there is not much to be gained with their constituents by pursuing foreign policy matters. [3] Domestic policy matters resonate more strongly with the voters at home. In other words, a sluggish economy, increasing health care costs, and crime matter more to them than U.S. policy toward North Korea. In an open-ended Gallup poll question from early 2016 about the “most important problem” in the United States, fewer than 15 percent of respondents named a foreign policy topic (half of those respondents mentioned immigration). [4]

Some House and Senate members ask to serve on the foreign policy committees, such as the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, the House Foreign Affairs Committee, and the two defense committees. These members might have military bases within their districts or states and hence have a constituency reason for being interested in foreign policy. Legislators might also simply have a personal interest in foreign policy matters that drives their engagement in the issue. Finally, they may have ambitions to move into an executive branch position that deals with foreign policy matters, such as secretary of state or defense, CIA director, or even president.

For more information on the two key congressional committees on U.S. foreign policy, visit the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations and the House Foreign Affairs Committee websites.

The Many Actors in Foreign Policy

The White House staff members engaged in foreign policy are likely to have very regular contact with the president about their work.

Foreign policy can at times seem fragmented and diffuse because of the complexity of actors and topics. However, the president is clearly the leader, having both formal authority and the ability to delegate to Congress, as explained in the two presidencies thesis. With this leadership, presidents at times can make foreign policymaking quick and decisive, especially when it calls for executive agreements and the military use of force.

- Krutz and Peake. Treaty Politics and the Rise of Executive Agreements. ↵

- Jon Bond, Richard Fleisher, Stephen Hanna, and Glen S. Krutz. 2000. "The Demise of the. Two Presidencies," American Politics Quarterly 28, No. 1: 3–25. ↵

- James M. McCormick. 2010. American Foreign Policy and Process, 5th ed. Boston: Wadsworth. ↵

- The Gallup Organization, "Most Important Problem," http://www.gallup.com/poll/1675/most-important-problem.aspx (May 12, 2016). ↵

- American Government 2e. Authored by : OpenStax. Located at : https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:xJJkKaSK@5/Preface . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]

The Two Presidencies

Presidential power is greatest when directing military and foreign policy

- Published: December 1966

- Volume 4 , pages 7–14, ( 1966 )

Cite this article

- Aaron Wildavsky

648 Accesses

27 Citations

131 Altmetric

17 Mentions

Explore all metrics

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Wildavsky, A. The Two Presidencies. Trans-action 4 , 7–14 (1966). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02810961

Download citation

Issue Date : December 1966

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02810961

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Foreign Policy

- Foreign Affair

- Domestic Policy

- Industrial Firm

- Defense Policy

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

1. ultimately declared the two presidencies ''time and culture bound,'' an artifact of a bipartisanship in foreign affairs resulting from ''shared values'' Amer-icans possessed on foreign policy during the 1950s (Oldfield and Wildavsky 1989, 55, 56). We revisit the two presidencies thesis and argue that it still appropriately ...

that both supports the two presidencies thesis and implies that Congress has incentives to delegate foreign policy powers to the president. Accordingly, the logic suggests that empirical analysis ...

The Dual Presidency Theory (also sometimes referred to as the ' Two Presidencies Thesis ') is a theory proposed by the political scientist Aaron Wildavsky during the Cold War. Influenced by the time period of 1946-1964, the Dual Presidency Theory is based on the principle that there are two versions of the American President: one who is concerned with domestic policy and one concerned with ...

davsky's thesis of the two presidencies and be more critical of it.6 In this article, I want to accomplish two main goals. First, I will present and dis cuss time-series or trend data from party activists on their levels of trust in the two presidencies. Second, I will employ the data and discussion themes in part as a basis for examining the ...

two presidencies thesis, as well as the newer variations discussed above. The data first are used to determine if Wildavsky's original findings were correct, and there was a strong two presidencies phenomenon throughout the post-war period or if Edwards' argument that the phenomenon did not exist prior to Eisenhower was closer to the truth.

The Two Presidencies. Wildavsky, Aaron. "The Two Presidencies," Trans-Action/Society, 4 (1966): 7-14. "The United States has one president, but it has two presidencies; one presidency is for domestic affairs, and the other is concerned with defense and foreign policy. Since World War II, presidents have had greater success in controlling the ...

The theory proposed is the multiple presidencies thesis, a more nuanced updating of the founding work on the " two presidencies " by Aaron Wildavsky (1966). I suggest that between the presidency and the Congress a high politics arena characterized by presidency-centered conditions favors securitization and greater presidential dominance vis-à ...

An enduring and controversial debate centers on whether there exist "two presidencies," that is, whether presidents exercise fundamentally greater influence over foreign than domestic affairs. This paper makes two contributions to understanding this issue and, by extension, presidential power more generally. First, we distill an institutional logic that both supports the two presidencies ...

The United States has one President, but it has two presidencies; one presidency is for domestic affairs, and the other is concerned with de-fense and foreign policy. Since World War II, Presidents have had much greater success in controlling the nation's defense and foreign policies than in dominating its domestic policies, (p. 448)

An enduring and controversial debate centers on whether there exist "two presidencies," that is, whether presidents exercise fundamentally greater influence over foreign than domestic affairs. This paper makes two contributions to understanding this issue and, by extension, presidential power more generally. First, we distill an institutional logic that both supports the two presidencies ...

THE TWO PRESIDENCIES . 163 AARON WILDAVSKY . 21. The Two Presidencies* AARON WILDAVSKY . The United . States has one president, though any president knows he supports . but it has two presidencies; one presi foreign aid and NATO, the world out dency is for domestic affairs, and the side changes much more rapidly than

Terms in this set (3) Main Point. There are two presidencies: domestic and foreign policy. Summary of Wildavskys Two Presidency Theory. Dual Presidency Theory is based on the principle that there are two versions of the American President: one who is concerned with domestic policy and one concerned with foreign policy.

T he United States has one president, but it has two presidencies; one presidency is for domestic affairs, and the other is concerned with defense and foreign policy. Since Wortd War II, Presidents have had much greater success in controlling the nation's defense and foreign policies than in dominating its domestic policies. Even Lyndon Johnson has seen his early record of victories in ...

This theory originated with University of California-Berkeley professor Aaron Wildavsky and suggests that there are two distinct presidencies, one for foreign policy and one for domestic policy, and that presidents are more successful in foreign than domestic policy. Let's look at the reasoning behind this thesis.

Semantic Scholar extracted view of "The Two Presidencies: A Quarter Century Assessment" by Steven A. Shull ... A Reevaluation of the Two Presidencies Thesis. Brandice Canes-Wrone William G. Howell D. Lewis. Political Science. ... The authors argue that an electoral connection drives partisanship in congressional foreign policy voting.

The major claim of the "Two Presidencies" thesis is that presidents fare better with Congress on foreign policy than on domestic policy. President Reagan (1981-88) received a "two presidencies" voting response from the House and Senate only when his party was a minority. The Republican Senate majority of 1981-86 produced no such effect.

Early years. A native of Brooklyn in New York, Wildavsky was the son of Ukrainian Jewish immigrants. After graduating from Brooklyn College, he served in the U.S. Navy and then won a Fulbright Fellowship to the University of Sydney for 1954-55. Wildavsky returned to the U.S. to attend graduate school at Yale University.His PhD dissertation, a study of the politics of the Dixon-Yates atomic ...

THE TWO PRESIDENCIES THESIS. When the media cover a domestic controversy, such as social unrest or police brutality, reporters consult officials at different levels and in branches of government, as well as think tanks and advocacy groups. In contrast, when an international event occurs, such as a terrorist bombing in Paris or Brussels, the ...

The Two Presidencies Thesis. When the media cover a domestic controversy, such as social unrest or police brutality, reporters consult officials at different levels and in branches of government, as well as think tanks and advocacy groups. In contrast, when an international event occurs, such as a terrorist bombing in Paris or Brussels, the ...

Ch. 11 Presidents & Foreign Policy. Explain Wildavsky's two presidencies thesis. Why is the president more successful in foreign policy making than in domestic policy making? The president needs congressional support to take domestic policy action, but congressional support is often unnecessary in foreign policy.

The Two Presidencies. Presidential power is greatest when directing military and foreign policy. Published: December 1966. Volume 4 , pages 7-14, ( 1966 ) Cite this article. Download PDF. Aaron Wildavsky. 648 Accesses. 27 Citations.

The "two presidencies" thesis asserts that _____. presidents have more control over legislation in the area of foreign and defense policy than over domestic matters. A writ of certiorari is _____. an order issued by a superior court to one of inferior jurisdiction demanding the record of a particular case.

Presidential-congressional relations scholars have long debated whether the president is more successful on foreign policy than on domestic policy (Wildavsky, 1966). The debate has focused on differential success rates between foreign and domestic policy and whether the gap has narrowed over time. This focus, however, neglects an important dimension of Wildavsky's argument. Wildavsky also ...

Path to profitability in 2024. P3 currently has a market capitalization of $183 million, which is in drastic disproportion to its latest quarterly revenue of $388.5 million and expected yearly ...