What Is Judicial Review?

- U.S. Legal System

- History & Major Milestones

- U.S. Constitution & Bill of Rights

- U.S. Political System

- Defense & Security

- Campaigns & Elections

- Business & Finance

- U.S. Foreign Policy

- U.S. Liberal Politics

- U.S. Conservative Politics

- Women's Issues

- Civil Liberties

- The Middle East

- Race Relations

- Immigration

- Crime & Punishment

- Canadian Government

- Understanding Types of Government

- M.A., History, University of Florida

- B.A., History, University of Florida

Judicial Review is the power of the U.S. Supreme Court to review laws and actions from Congress and the President to determine whether they are constitutional. This is part of the checks and balances that the three branches of the federal government use in order to limit each other and ensure a balance of power.

Key Takeaways: Judicial Review

- Judicial review is the power of the U.S. Supreme Court to decide whether a law or decision by the legislative or executive branches of federal government, or any court or agency of the state governments is constitutional.

- Judicial review is a key to the doctrine of balance of power based on a system of “checks and balances” between the three branches of the federal government.

- The power of judicial review was established in the 1803 Supreme Court case of Marbury v. Madison .

Judicial review is the fundamental principle of the U.S. system of federal government , and it means that all actions of the executive and legislative branches of government are subject to review and possible invalidation by the judiciary branch . In applying the doctrine of judicial review, the U.S. Supreme Court plays a role in ensuring that the other branches of government abide by the U.S. Constitution. In this manner, judicial review is a vital element in the separation of powers between the three branches of government .

Judicial review was established in the landmark Supreme Court decision of Marbury v. Madison , which included the defining passage from Chief Justice John Marshall: “It is emphatically the duty of the Judicial Department to say what the law is. Those who apply the rule to particular cases must, of necessity, expound and interpret the rule. If two laws conflict with each other, the Court must decide on the operation of each.”

Marbury vs. Madison and Judicial Review

The power of the Supreme Court to declare an act of the legislative or executive branches to be in violation of the Constitution through judicial review is not found in the text of the Constitution itself. Instead, the Court itself established the doctrine in the 1803 case of Marbury v. Madison .

On February 13, 1801, outgoing Federalist President John Adams signed the Judiciary Act of 1801, restructuring the U.S. federal court system . As one of his last acts before leaving office, Adams appointed 16 (mostly Federalist-leaning) judges to preside over new federal district courts created by the Judiciary Act.

However, a thorny issue arose when new Anti-Federalist President Thomas Jefferson ’s Secretary of State, James Madison refused to deliver official commissions to the judges Adams had appointed. One of these blocked “ Midnight Judges ,” William Marbury, appealed Madison’s action to the Supreme Court in the landmark case of Marbury v. Madison ,

Marbury asked the Supreme Court to issue a writ of mandamus ordering the commission be delivered based on the Judiciary Act of 1789. However, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court John Marshall ruled that the portion of the Judiciary Act of 1789 allowing for writs of mandamus was unconstitutional.

This ruling established the precedent of judicial branch of the government to declare a law unconstitutional. This decision was a key in helping to place the judicial branch on a more even footing with the legislative and the executive branches. As Justice Marshall wrote:

“It is emphatically the province and duty of the Judicial Department [the judicial branch] to say what the law is. Those who apply the rule to particular cases must, of necessity, expound and interpret that rule. If two laws conflict with each other, the Courts must decide on the operation of each.”

Expansion of Judicial Review

Over the years, the US Supreme Court has made a number of rulings that have struck down laws and executive actions as unconstitutional. In fact, they have been able to expand their powers of judicial review.

For example, in the 1821 case of Cohens v. Virginia , the Supreme Court expanded its power of constitutional review to include the decisions of state criminal courts.

In Cooper v. Aaron in 1958, the Supreme Court expanded the power so that it could deem any action of any branch of a state's government to be unconstitutional.

Examples of Judicial Review in Practice

Over the decades, the Supreme Court has exercised its power of judicial review in overturning hundreds of lower court cases. The following are just a few examples of such landmark cases:

Roe v. Wade (1973): The Supreme Court ruled that state laws prohibiting abortion were unconstitutional. The Court held that a woman's right to an abortion fell within the right to privacy as protected by the Fourteenth Amendment . The Court’s ruling affected the laws of 46 states. In a larger sense, Roe v. Wade confirmed that the Supreme Court’s appellate jurisdiction extended to cases affecting women’s reproductive rights, such as contraception.

Loving v. Virginia (1967): State laws prohibiting interracial marriage were struck down. In its unanimous decision, the Court held that distinctions drawn in such laws were generally “odious to a free people” and were subject to “the most rigid scrutiny” under the Equal Protection Clause of the Constitution. The Court found that the Virginia law in question had no purpose other than “invidious racial discrimination.”

Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010): In a decision that remains controversial today, the Supreme Court ruled laws restricting spending by corporations on federal election advertising unconstitutional. In the decision, an ideologically divided 5-to-4 majority of justices held that under the First Amendment corporate funding of political advertisements in candidate elections cannot be limited.

Obergefell v. Hodges (2015): Again wading into controversy-swollen waters, the Supreme Court found state laws banning same-sex marriage to be unconstitutional. By a 5-to-4 vote, the Court held that the Due Process of Law Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment protects the right to marry as a fundamental liberty and that the protection applies to same-sex couples in the same way it applies to opposite-sex couples. In addition, the Court held that while the First Amendment protects the rights of religious organizations to adhere to their principles, it does not allow states to deny same-sex couples the right to marry on the same terms as those for opposite-sex couples.

Updated by Robert Longley

- Republic vs. Democracy: What Is the Difference?

- Marbury v. Madison

- The Judiciary Act of 1801 and the Midnight Judges

- 7 Important Supreme Court Cases

- Constitutional Law: Definition and Function

- Biography of John Marshall, Influential Supreme Court Justice

- Overview of United States Government and Politics

- Separation of Powers: A System of Checks and Balances

- The Original Jurisdiction of the US Supreme Court

- The U.S. Constitution

- National Supremacy and the Constitution as Law of the Land

- Current Justices of the U.S. Supreme Court

- 5 Ways to Change the US Constitution Without the Amendment Process

- Basic Structure of the US Government

- What Is Nullification? Definition and Examples

- What Is Judicial Activism?

A Summary of Why We Need More Judicial Activism

Seth Robertson

Mar 24, 2014, 8:31 AM

By Suzanna Sherry, Herman O. Loewenstein Professor of Law

In this piece, Suzanna Sherry summarizes her essay, “Why We Need More Judicial Activism.” The full version of the essay will appear in a collection Sherry has co-edited with Giorgi Areshidze and Paul Carrese to be released in 2014 by SUNY Press. Sherry wrote this summary for the quarterly legal journal Green Bag , which devoted part of its summer 2013 edition to articles commenting on her essay. She characterizes the essay as “a rhetorical call to arms and an embrace of judicial activism.”

Too much of a good thing can be bad, and democracy is no exception. In the United States, the antidote to what the drafters of the Constitution called “the excess of democracy” is judicial review: unelected, life-tenured federal judges with power to invalidate the actions of the more democratic branches of government. Lately, judicial review has come under fire. Many on both sides of the political aisle accuse the Supreme Court of being overly activist and insufficiently deferential to the elected representatives of the people. Taking the Constitution away from the courts—and giving it back to the people—has become a rallying cry. But those who criticize the courts on this ground misunderstand the proper role of the judiciary. The courts should stand in the way of democratic majorities, in order to keep majority rule from degenerating into majority tyranny. In doing so, the courts are bound to err on one side or the other from time to time. It is much better for the health of our constitutional democracy if they err on the side of activism, striking down too many laws rather than too few.

In this forthcoming essay defending judicial activism, I begin by defining two slippery and often misused concepts, judicial review and judicial activism, and briefly survey the recent attacks on judicial activism. I then turn to supporting my claim that we need more judicial activism, resting my argument on three grounds. First, constitutional theory suggests a need for judicial oversight of the popular branches. Second, our own constitutional history confirms that the founding generation—the drafters of our Constitution—saw a need for a strong bulwark against majority tyranny. Finally, an examination of constitutional practice shows that too little activism produces worse consequences than does too much. If we cannot assure that the judges tread the perfect middle ground (and we cannot), it is better to have an overly aggressive judiciary than an overly restrained one.

Judicial review is not judicial supremacy. Judicial review allows courts an equal say with the other branches, not the supreme word. Courts are the final arbiter of the Constitution only to the extent that they hold a law unconstitutional, and even then only because they act last in time, not because their will is supreme. If judicial review is simply the implementation of courts’ equal participation in government, what, then, is judicial activism? To avoid becoming mired in political squabbles, we need a definition of judicial activism with no political valence. Judicial activism occurs any time the judiciary strikes down an action of the popular branches, whether state or federal, legislative or executive. Judicial review, in other words, produces one of two possible results: If the court invalidates the government action it is reviewing, then it is being activist; if it upholds the action, it is not.

Under that definition, and because the Court is not perfect, the question becomes whether we prefer a Supreme Court that strikes down too many laws or one that strikes down too few. Many contemporary constitutional scholars favor a deferential Court that invalidates too few. I suggest that we are better off with an activist Court that strikes down too many.

As many scholars have previously argued, judicial review is a safeguard against the tyranny of the majority, ensuring that our Constitution protects liberty as well as democracy. And, indeed, the founding generation expected judicial review to operate as just such a protection against democratic majorities. A Court that is too deferential cannot fulfill that role.

More significant, however, is the historical record of judicial review. Although it is difficult to find consensus about much of what the Supreme Court does, there are some cases that are universally condemned. Those cases offer a unique lens through which we can evaluate the relative merits of deference and activism: Are most of those cases—the Court’s greatest mistakes, as it were—overly activist or overly deferential? It turns out that virtually all of them are cases in which an overly deferential Court failed to invalidate a governmental action.1

When the Court fails to act—instead deferring to the elected branches—it abdicates its role as guardian of enduring principles against the temporary passions and prejudices of popular majorities. It is thus no surprise that with historical hindsight we sometimes come to regret those passions and prejudices and fault the Court for its passivity.

Ideally, of course, the Court should be like Baby Bear: It should get everything just right, engaging in activism when, and only when, We the People act in ways that we will later consider shameful or regrettable. But that perfection is impossible, and so we must choose between a Court that views its role narrowly and a Court that views its role broadly, between a more deferential Court and a more activist Court. Both kinds of Court will sometimes be controversial, and both will make mistakes. But history teaches us that the cases in which a deferential Court fails to invalidate governmental acts are worse. Only a Court inclined toward activism will vigilantly avoid such cases, and hence we need more judicial activism.

1 The essay lists the following as universally condemned cases (in chronological order): Bradwell v. State , 16 Wall. (83 U.S.) 130 (1873); Minor v. Happersett , 21 Wall. (88 U.S.) 162 (1874); Plessy v. Ferguson , 163 U.S. 537 (1896); Abrams v. U.S. , 250 U.S. 616 (1919); Schenck v. U.S. , 249 U.S. 47 (1919); Frohwerk v. U.S. , 249 U.S. 204 (1919); Debs v. U.S ., 249 U.S. 211 (1919); Buck v. Bell , 274 U.S. 200 (1927); Minersville School Dist. v. Gobitis , 310 U.S. 586 (1940); Hirabayashi v. U.S. , 320 U.S. 81 (1943); and Korematsu v. U.S. , 323 U.S. 214 (1944). Cases over which there is significant division, such as Roe v. Wade , 410 U.S. 113 (1973), and Lochner v. New York , 198 U.S. 45 (1905), are excluded. Dred Scott v. Sandford , 60 U.S. 393 (1856), and Bush v. Gore , 531 U.S. 98 (2000), are also excluded, on two grounds: They ultimately had little or no real-world effect; and they were products of a Court attempting to save the nation from constitutional crises, which is bound to increase the likelihood of an erroneous decision. Even if Dred Scott and Bush v. Gore are included, only two of 13 reviled cases are activist while 11 are deferential.

Reprinted from 16 Green Bag 2d 449 (2013), “Micro-Symposium: Sherry’s ‘Judicial Activism.’”

Explore Story Topics

- Uncategorized

Contact: ✉️ [email protected] ☎️ (803) 302-3545

The power of judicial review, what is judicial review.

In America, judicial review refers to the power of the courts to examine laws and other government actions to determine if they violate or contradict previous laws, the state’s constitution, or the federal constitution. If a law is declared to be unconstitutional, it is overturned (or “struck down”) in whole or in part.

Judicial review is a vital and influential power that allows the judicial branch of the government to prevent local, state, and federal governments from taking unconstitutional actions.

While the Supreme Court has historically attempted to use its power to overturn laws as a last resort in cases where the law’s unconstitutionality is clear, the looming threat of judicial review influences legislators as they craft bills and regulations.

What Gives Courts the Power of Judicial Review?

Judicial review is not explicitly defined in the United States Constitution. Instead, it’s strongly implied when certain passages are considered together. The judicial system is given the final authority to determine which law to uphold, and in Article IV , the Constitution is named the “ supreme Law of the Land .” When combined, these elements seem to give courts the duty to uphold the Constitution over any contradictory laws whenever a discrepancy appears.

Get Smarter on US News, History, and the Constitution

Join the thousands of fellow patriots who rely on our 5-minute newsletter to stay informed on the key events and trends that shaped our nation's past and continue to shape its present.

Check your inbox or spam folder to confirm your subscription.

Did the Framers Intend Judicial Review?

Despite the lack of an explicit passage outlining the power of judicial review, modern scholars think that the framers of the Constitution very much intended this power to exist. The framers spoke a great deal about judicial review during the Constitutional Convention and during state ratification debates. The Federalist Papers referred to the concept several times, most extensively in Federalist no. 78 and Federalist no. 80.

Additionally, six states explicitly stated that they thought that federal courts had the power to review the constitutionality of laws in their responses to the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions in 1798. In other words, nearly half of the original thirteen states interpreted the Constitution as granting the judiciary the power of judicial review a scant handful of years after it was written and well before Marbury v Madison .

Prior to Marbury v Madison

Federal courts examined the constitutionality of federal statutes several times before 1803, but no active law was overturned before Marbury v Madison . In Hayburn’s Case , decided in 1792, three federal circuit courts ruled that the same law was unconstitutional. The law delegated the review of pension applications to circuit court judges. These court decisions were appealed to the Supreme Court, but the law was repealed by legislators before the appeal could take place.

Judicial review of federal legislation occurred in 1796 in Hylton v United States , but the Supreme Court held that the law in question was constitutional. The 1796 Supreme Court did strike down a Virginia statute concerning pre-Revolutionary War debts, finding the law in question contrary to a peace treaty between the US and Great Britain. Under the Constitution’s Supremacy Clause , the court struck the law down.

Between 1798 and 1800, the ruling in Marbury v Madison was foreshadowed clearly. The findings in the 1798 case Hollingsworth v Virginia relied on an interpretation of the Eleventh Amendment’s limitations on the jurisdiction that strongly implied that the Supreme Court would find the Judiciary Act of 1789 unconstitutional.

Justice Chase penned the opinion in Cooper v Telfair in 1800 and included a statement that indicated that most judges felt that the Supreme Court had the power to find a federal law unconstitutional. However, it had not done so yet. The power was not exercised until Marbury v Madison in 1803.

Marbury v Madison

In 1803, the Marshall court struck down the Judiciary Act of 1789. The law gave the Supreme Court the power to issue writs of mandamus that would force courts or officials to exercise their duties. Article III of the Constitution directly stated that the Supreme Court would have appellate jurisdiction over all but a very narrow subset of cases. Marbury v Madison held that the Judiciary Act of 1789 was unconstitutional. The Marshall court interpreted the Judiciary Act of 1789 as giving the court original jurisdiction over cases where a petitioner sought the court to issue a writ of mandamus.

Legal scholars have lauded the politics behind the exact ruling reached in Marbury v Madison for centuries. While the Supreme Court struck down the Judiciary Act, it did so in a way that benefited the incumbent administration. This gave little incentive for the administrative branch of the government to challenge the ruling in a way that would weaken the nascent Supreme Court’s power.

Some scholars theorize that the ruling was the only one that would have been enforced, as had the Supreme Court upheld the Judiciary Act of 1789 and issued a writ of mandamus, the Jefferson administration would have simply ignored the writ and weakened the Supreme Court forever.

Stare Decisis

Once Marbury v Madison was decided, judicial review became enshrined in law by a practice called stare decisis. Under stare decisis, courts attempt to let decisions and legal actions made by previous courts stand unless there’s a very strong reason to overturn them. The more a decision or action is relied upon for precedent, the less likely a future court is to overturn it.

For centuries, judicial review has been a key part of United States lawmaking and court cases. Even if something changed dramatically in our interpretation of the constitution that caused legal scholars to stop thinking that the constitution implied the power of judicial review, it’s doubtful that any court would overturn judicial review without a constitutional amendment.

Judicial Review Throughout History

After Marbury v Madison , the Supreme Court did not strike down a federal law as unconstitutional for fifty years. While the fear of judicial review being challenged and potentially overturned likely had something to do with this, it’s also worth noting that many of the framers of the constitution were alive during many of these fifty years and that legislators were respectful of the supremacy of the newly enshrined constitution. The Supreme Court did, however, hold that some state law was unconstitutional and had no qualms about using its judicial supremacy to strike such legislation down.

Dred Scott v Sandford

The next law to be struck down as unconstitutional was the Missouri Compromise, which outlined which new territories added to the United States would allow slavery. The case, Dred Scott v Sandford, was heard in 1857 and held that the United States Constitution never intended anyone of African descent to be considered a citizen of the United States. The Civil War occurred four years later.

Historians often point to the Dred Scott decision as one of the turning points in the rising tension between slaveholding states and the free North. In 1865, the 13th amendment overturned Dred Scott by abolishing slavery and explicitly granting citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States .

Modern Judicial Review

Judicial review is a cornerstone of the modern United States. By 2017, 182 federal statutes had been held unconstitutional in whole or in part. Justices have traditionally erred on the side of caution and attempted to exercise the power of judicial review as a last resort.

That said, the court’s history of striking down laws suggests that either lawmakers are being more brazen in their efforts to skirt the edges of what the constitution allows, or the Supreme Court is more willing to step in and intercede on edge cases. Modern political discussions surrounding abortion , gun control , and religious freedom often center around the Supreme Court’s constitutional interpretation and the amendments that surround those issues.

Recent applications of judicial review include:

- Citizens United v Federal Election Commission (2010), in which the court struck down a law that interfered with the ability of corporations and associations to spend money on election advertising.

- National Federation of Independent Business v Sebelius (2012), in which the court upheld the constitutionality of much of the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act, sometimes called “Obamacare.”

The Court’s Reluctance To Strike Down Laws

In general, the Supreme Court has attempted to avoid ruling on the constitutionality of a law if it can decide the issue before it by any other means. When it must challenge the constitutionality of a law, it attempts to do so in the most limited way possible, striking down as little of the law as it can. Justice Brandeis famously outlined seven rules that the Supreme Court tends to follow when it reviews laws:

- The court requires a live, contentious case before it will rule.

- It will not issue opinions in advance of a case.

- It will interpret the constitution as narrowly as it can.

- A ruling on the constitutionality of a law is only used as a last resort if other factors cannot decide the case.

- One of the petitioners in the case must have actually been adversely affected by the unconstitutional law.

- Someone who benefits from a law cannot challenge its constitutionality.

- The law will be interpreted in the most favorable way regarding its constitutionality.

Preventing Judicial Review

Under Article III of the Constitution, Congress can curtail the Supreme Court’s appellate jurisdiction. This means that Congress can limit the authority of the Supreme Court to hear cases regarding certain laws. This power has occasionally been utilized, although not always successfully. Notably, the Detainee Treatment Act of 2005 and the Military Commissions Act of 2006 were ruled unconstitutional despite language in both laws that attempted to limit their ability to be reviewed by courts.

Alicia Reynolds

One response.

This is an unbalanced view of what is clearly a substantial flaw in the American system of governance. The notion that 5 justices can overrule the House and the Senate and the President is absurd and objectionable on the ground that there are much more cooperative ways to deal with mistakes in statutes … and in readings of a 18th century document that has produced innumerable embarrassing judgments.

Clean this up! Please!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Majority Rule, Minority Rights: The Constitution and Court Cases

Updated information about states, why was the constitution written, what is a market economy, and how does it compare to a planned economy, please enter your email address to be updated of new content:.

© 2023 US Constitution All rights reserved

Article III, Section 1:

The judicial Power of the United States, shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour, and shall, at stated Times, receive for their Services, a Compensation, which shall not be diminished during their Continuance in Office.

One key feature of the federal judicial power is the power of judicial review, the authority of federal courts to declare that federal or state government actions violate the Constitution. While judicial review is now one of the distinctive features of United States constitutional law, the Constitution does not expressly grant federal courts power to declare government actions unconstitutional. However, the historical record from the Founding and the early years of the Republic suggests that those who framed and ratified the Constitution were aware of judicial review, and that some favored granting courts that power.

The concept of judicial review was already established at the time of the Founding. The Privy Council had employed a limited form of judicial review to review colonial legislation and its validity under the colonial charters. 1 Footnote Julius Goebel , Antecedents and Beginnings to 1801, History of the Supreme Court of the United States 60–95 (1971) . There were several instances known to the Framers of state court invalidation of state legislation as inconsistent with state constitutions. 2 Footnote Id. at 96–142 . Practically all of the Framers who expressed an opinion on the issue in the Convention appear to have assumed and welcomed the existence of court review of the constitutionality of legislation. 3 Footnote 1 Max Farrand , The Framing of the Constitution of the United States 97–98 (1913) (Gerry), 109 (King); 2 Max Farrand , The Framing of the Constitution of the United States 28 (1913) (Morris and perhaps Sherman), 73 (Wilson), 75 (Strong, but the remark is ambiguous), 76 (Martin), 78 (Mason), 79 (Gorham, but ambiguous), 80 (Rutledge), 92–93 (Madison), 248 (Pinckney), 299 (Morris), 376 (Williamson), 391 (Wilson), 428 (Rutledge), 430 (Madison), 440 (Madison), 589 (Madison); 3 Max Farrand , The Framing of the Constitution of the United States 220 (1913) (Martin). The only expressed opposition to judicial review came from Mercer with a weak seconding from Dickinson. “Mr. Mercer . . . disapproved of the Doctrine that the Judges as expositors of the Constitution should have authority to declare a law void. He thought laws ought to be well and cautiously made, and then to be uncontroulable.” 2 Max Farrand , The Framing of the Constitution of the United States 298 (1913) . “Mr. Dickinson was strongly impressed with the remark of Mr. Mercer as to the power of the Judges to set aside the law. He thought no such power ought to exist. He was at the same time at a loss what expedient to substitute.” Id. at 299 . Of course, the debates in the Convention were not available when the state ratifying conventions acted, so that the delegates could not have known these views about judicial review in order to have acted knowingly about them. Views, were, however, expressed in the ratifying conventions recognizing judicial review, some of them being uttered by Framers. 2 J. Elliot , Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution 131 (1836) (Samuel Adams, Massachusetts), 196–97 (Ellsworth, Connecticut), 348, 362 (Hamilton, New York): 445–46. 478 (Wilson, Pennsylvania); 3 J. Elliot , Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution 324–25, 539 , 541 (1836) (Henry, Virginia), 480 (Mason, Virginia), 532 (Madison, Virginia), 570 (Randolph, Virginia); 4 J. Elliot , Debates in the Several State Conventions on the Adoption of the Federal Constitution 71 (1836) (Steele, North Carolina), 156–57 (Davie, North Carolina). In the Virginia convention, Chief Justice John Marshall observed if Congress “were to make a law not warranted by any of the powers enumerated, it would be considered by the judge as an infringement of the Constitution which they are to guard . . . They would declare it void . . . . To what quarter will you look for protection from an infringement on the constitution, if you will not give the power to the judiciary? There is no other body that can afford such a protection.” 3 id. at 553–54 . Both Madison and Hamilton similarly asserted the power of judicial review in their campaign for ratification. The Federalist No. 39 (James Madison); id. Nos. 78, 81 (Alexander Hamilton). The persons supporting or at least indicating they thought judicial review existed did not constitute a majority of the Framers, but the absence of controverting statements, with the exception of the Mercer-Dickinson comments, indicates at least acquiescence if not agreements by the other Framers. Alexander Hamilton argued in favor of the doctrine in the Federalist Papers . 4 Footnote The Federalist No. 78 (Alexander Hamilton) ( “The interpretation of the laws is the proper and peculiar province of the courts. A constitution, is, in fact, and must be regarded by the judges, as a fundamental law. It therefore belongs to them to ascertain its meaning, as well as the meaning of any particular act proceeding from the legislative body. If there should happen to be an irreconcilable variance between two, that which has the superior obligation and validity ought, of course, to be preferred; or, in other words, the constitution ought to be preferred to the statute, the intention of the people to the intention of their agents.” ). In enacting the Judiciary Act of 1789, Congress explicitly provided for the exercise of the power, 5 Footnote In enacting the Judiciary Act of 1789, 1 Stat. 73 , Congress chose not to vest “federal question” jurisdiction in the federal courts but to leave to the state courts the enforcement of claims under the Constitution and federal laws. In Section 25 of the Judiciary Act ( 1 Stat. 85 ), Congress provided for review by the Supreme Court of final judgments in state courts (1) “where is drawn in question the validity of a treaty or statute of, or an authority exercised under the United States, and the decision is against their validity;” (2) “where is drawn in question the validity of a statute of, or an authority exercised under any State, on the ground of their being repugnant to the constitution, treaties or laws of the United States, and the decision is in favor of their validity;” or (3) “where is drawn in question the construction of any clause of the constitution, or of a treaty, or statute of, or commission held under the United States, and the decision is against the title, right, privilege or exemption specially set up or claimed” thereunder. § 25, 1 Stat. 73 , 85–86 . and in other legislative debates questions of constitutionality and of judicial review were prominent. 6 Footnote See in particular the debate on the President’s removal powers, discussed in ArtII.S2.C2.3.15.1 Overview of Removal of Executive Branch Officers with statements excerpted in R. Berger , Congress v. The Supreme Court 144–150 (1969) . Debates on the Alien and Sedition Acts and on the power of Congress to repeal the Judiciary Act of 1801 similarly saw recognition of judicial review of acts of Congress. C. Warren , in id. at 107–12 4. Early Supreme Court Justices seem to have assumed the existence of judicial review. 7 Footnote Thus, the Justices on circuit refused to administer a pension act on the grounds of its unconstitutionally, see Hayburn’s Case, 2 U.S. (2 Dall.) 409 (1792) , and ArtIII.S1.4.4 Inherent Power to Issue Judgments. Chief Justice Jay and other Justices wrote that the imposition of circuit duty on Justices was unconstitutional, although they never mailed the letter in Hylton v. United States, 3 U.S. (3 Dall.) 171 (1796) , a feigned suit, the constitutionality of a federal law was argued before the Justices and upheld on the merits, in Ware v. Hylton, 3 U.S. (3 Dall.) 199 (1796) , a state law was overturned, and dicta in several opinions asserted the principle. See Calder v. Bull, 3 U.S. (3 Dall.) 386, 399 (1798) (Justice Iredell), and several Justices on circuit, quoted in Julius Goebel, supra note 1, at 589–592.

The Supreme Court first formally embraced the doctrine of judicial review in the 1803 case Marbury v. Madison . 8 Footnote 5 U.S. (1 Cr.) 137 (1803) . Since Marbury , judicial review has become a core feature of American constitutional law. 9 Footnote See ArtIII.S1.3 Marbury v. Madison and Judicial Review. While the doctrine is well established, some legal commentators have criticized judicial review, and some who support it debate its doctrinal basis or how it should be applied. 10 Footnote See, e.g. , G. Gunther , Constitutional Law 1–38 (12th ed. 1991) ; For expositions on the legitimacy of judicial review, see L. Hand , The Bill of Rights (1958) ; H. Wechsler , Principles, Politics, and Fundamental Law: Selected Essays 1–15 (1961) ; A. Bickel , The Least Dangerous Branch: The Supreme Court at the Bar of Politics 1–33 (1962) ; R. Berger , Congress v. The Supreme Court (1969) . For an extensive historical attack on judicial review, see 2 W. Crosskey , Politics and the Constitution in the History of the United States chs. 27–29 (1953) , with which compare Hart, Book Review , 67 Harv. L. Rev. 1456 (1954) . A brief review of the ongoing debate on the subject, in a work that now is a classic attack on judicial review, is Westin, Introduction: Charles Beard and American Debate Over Judicial Review , 1790–1961 , in C. Beard , The Supreme Court and the Constitution 1–34 (1962 reissue of 1938 ed.) , and bibliography at 133–149. While much of the debate focuses on judicial review of acts of Congress, the similar review of state acts has occasioned much controversy as well.

Legal Dictionary

The Law Dictionary for Everyone

Judicial Review

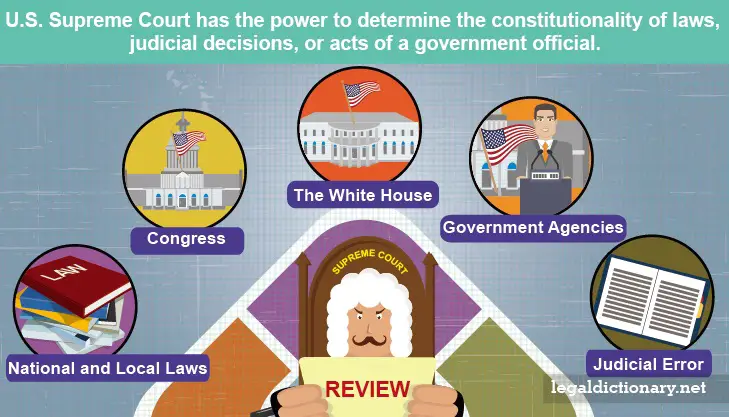

In the United States, the courts have the ability to scrutinize statutes, administrative regulations, and judicial decisions to determine whether they violate provisions of existing laws, or whether they violate the individual State or United States Constitution . A court having judicial review power, such as the United States Supreme Court, may choose to quash or invalidate statutes, laws, and decisions that conflict with a higher authority. Judicial review is a part of the checks and balances system in which the judiciary branch of the government supervises the legislative and executive branches of the government. To explore this concept, consider the following judicial review definition.

Definition of Judicial Review

- Noun. The power of the U.S. Supreme Court to determine the constitutionality of laws, judicial decisions, or acts of a government official.

Origin: Early 1800s U.S. Supreme Court

What is Judicial Review

While the authors of the U.S. Constitution were unsure whether the federal courts should have the power to review and overturn executive and congressional acts, the Supreme Court itself established its power of judicial review in the early 1800s with the case of Marbury v. Madison (5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137, 2L Ed. 60). The case arose out of the political wrangling that occurred in the weeks before President John Adams left office for Thomas Jefferson.

The new President and Congress overturned the many judiciary appointments Adams had made at the end of his term, and overturned the Congressional act that had increased the number of Presidential judicial appointments. For the first time in the history of the new republic , the Supreme Court ruled that an act of Congress was unconstitutional. By asserting that it is emphatically the judicial branch ’s province to state and clarify what the law actually is, the court assured its position and power over judicial review.

Topics Subject to Judicial Review

The judicial review process exists to help ensure no law enacted, or action taken, by the other branches of government , or by lower courts, contradicts the U.S. Constitution. In this, the U.S. Supreme Court is the “supreme law of the land.” Individual State Supreme Courts have the power of judicial review over state laws and actions, charged with making rulings consistent with their state constitutions. Topics that may be brought before the Supreme Court may include:

- Executive actions or orders made by the President

- Regulations issued by a government agency

- Legislative actions or laws made by Congress

- State and local laws

- Judicial error

Judicial Review Example Cases

Throughout the years, the Supreme Court has made many important decisions on issues of civil rights , rights of persons accused of crimes, censorship , freedom of religion, and other basic human rights. Below are some notable examples.

Miranda v. Arizona (1966)

The history of modern day Miranda rights begins in 1963, when Ernesto Miranda was arrested for, and interrogated about, the rape of an 18-year-old woman in Phoenix, Arizona. During the lengthy interrogation, Miranda, who had never requested a lawyer , confessed and was later convicted of rape and sent to prison . Later, an attorney appealed the case, requesting judicial review by the Supreme Court, claiming that Ernesto Miranda’s rights had been violated, as he never knew he didn’t have to speak at all with the police.

The Supreme Court, in 1966, overturned Miranda’s conviction, and the court ruled that all suspects must be informed of their right to an attorney, as well as their right to say nothing, before questioning by law enforcement. The ruling declared that any statement, confession, or evidence obtained prior to informing the person of their rights would not be admissible in court. While Miranda was retried and ultimately convicted again, this landmark Supreme Court ruling resulted in the commonly heard “Miranda Rights” read to suspects by police everywhere in the country.

Weeks v. United States (1914)

Federal agents, suspecting Fremont Weeks was distributing illegal lottery chances through the U.S. mail system, entered and searched his home, taking some of his personal papers with them. The agents later returned to Weeks’ house to collect more evidence, taking with them letters and envelopes from his drawers. Although the agents had no search warrant , seized items were used to convict Weeks of operating an illegal gambling ring.

The matter was brought to judicial review before the U.S. Supreme Court to decide whether Weeks’ Fourth Amendment right to be secure from unreasonable search and seizure , as well as his Fifth Amendment right to not testify against himself, had been violated. The Court, in a unanimous decision, ruled that the agents had unlawfully searched for, seized, and kept Weeks’ letters. This landmark ruling led to the “ Exclusionary Rule ,” which prohibits the use of evidence obtained in an illegal search in trial .

Plessey v. Ferguson (1869)

Having been arrested and convicted for violating the law requiring “Blacks” to ride in separate train cars, Homer Plessey appealed to the Supreme Court, stating the so called “Jim Crow” laws violated his 14th Amendment right to receive “equal protection under the law.” During the judicial review, the state argued that Plessey and other Blacks were receiving equal treatment, but separately. The Court upheld Plessey’s conviction, and ruled that the 14th Amendment guarantees the right to “equal facilities,” not the “same facilities.” In this ruling, the Supreme Court created the principle of “ separate but equal .”

United States v. Nixon (“Watergate”) (1974)

During the 1972 election campaign between Republican President Richard Nixon and Democratic Senator George McGovern, the Democratic headquarters in the Watergate building was burglarized. Special federal prosecutor Archibald Cox was assigned to investigate the matter, but Nixon had him fired before he could complete the investigation. The new prosecutor obtained a subpoena ordering Nixon to release certain documents and tape recordings that almost certainly contained evidence against the President.

Nixon, asserting an “absolute executive privilege” regarding any communications between high government officials and those who assist and advise them, produced heavily edited transcripts of 43 taped conversations, asking in the same instant that the subpoena be quashed and the transcripts disregarded. The Supreme Court first ruled that the prosecutor had submitted sufficient evidence to obtain the subpoena, then specifically addressed the issue of executive privilege. Nixon’s declaration of an “absolute, unqualified Presidential privilege of immunity from judicial process under all circumstances,” was flatly rejected. In the midst of this “Watergate scandal,” Nixon resigned from office just 15 days later, on August 9, 1974.

The Authority Behind Judicial Review

Interestingly, Article III of the U.S. Constitution does not specifically give the judicial branch the authority of judicial review. It states specifically:

“The judicial Power shall extend to all Cases, in Law and Equity, arising under this Constitution, the Laws of the United States, and Treaties made, or which shall be made, under their Authority.”

This language clearly does not state whether the Supreme Court has the power to reverse acts of Congress. The power of judicial review has been garnered by assumption of that power:

- Power From the People . Alexander Hamilton, rather than attempting to prove that the Supreme Court had the power of judicial review, simply assumed it did. He then focused his efforts on persuading the people that the power of judicial review was a positive thing for the people of the land.

- Constitution Binding on Congress . Hamilton referred to the section that states “No legislative act, therefore, contrary to the Constitution, can be valid,” and pointed out that judicial review would be needed to oversee acts of Congress that may violate the Constitution.

- The Supreme Court’s Charge to Interpret the Law . Hamilton observed that the Constitution must be seen as a fundamental law, specifically stated to be the supreme law of the land. As the courts have the distinct responsibility of interpreting the law, the power of judicial review belongs with the Supreme Court.

What Cases are Eligible for Judicial Review

Although one party or another is going to be unhappy with a judgment or verdict in most court cases, not every case is eligible for appeal . In fact, there must be some legal grounds for an appeal, primarily a reversible error in the trial procedures, or the violation of Constitutional rights . Examples of reversible error include:

- Jurisdiction . The court wrongly assumes jurisdiction in a case over which another court has exclusive jurisdiction.

- Admission or Exclusion of Evidence . The court incorrectly applies rules or laws to either admit or deny the admission of certain vital evidence in the case. If such evidence proves to be a key element in the outcome of the trial, the judgment may be reversed on appeal.

- Jury Instructions . If, in giving the jury instructions on how to apply the law to a specific case, the judge has applied the wrong law, or an inaccurate interpretation of the correct law, and that error is found to have been prejudicial to the outcome of the case, the verdict may be overturned on judicial review.

Related Legal Terms and Issues

- Executive Privilege – The principle that the President of the United States has the right to withhold information from Congress, the courts, and the public, if it jeopardizes national security, or because disclosure of such information would be detrimental to the best interests of the Executive Branch .

- Jim Crow Laws – The legal practice of racial segregation in many states from the 1880s through the 1960s. Named after a popular black character in minstrel shows, the Jim Crow laws imposed punishments for such things as keeping company with members of another race, interracial marriage, and failure of business owners to keep white and black patrons separated.

- Judicial Decision – A decision made by a judge regarding the matter or case at hand.

- Overturn – To change a decision or judgment so that it becomes the opposite of what it was originally.

- Search Warrant – A court order that authorizes law enforcement officers or agents to search a person or a place for the purpose of obtaining evidence or contraband for use in criminal prosecution.

- Administrative and public law

Judicial review reform

The UK has a long and proud history of honouring the rule of law. This means that everyone, including the government, must comply with the law.

Judicial review is a vital part of the justice system in England and Wales. It’s a way for people to:

- assert their fundamental rights

- test the lawfulness of decisions made by public bodies

- seek a remedy when things go wrong

Judicial review is an important part of our constitutional balance of powers between the executive, parliament, and judiciary.

It's a way of upholding the sovereignty of parliament and maintaining trust in government decision-making.

Hear from Joe and Lucy about their experiences of using judicial review

Judicial Review and Courts Act

The government introduced the Judicial Review and Courts Bill in July 2021. It received royal assent and became law on 28 April 2022.

The Judicial Review and Courts Act makes changes to judicial review by:

- giving the courts powers to award suspended and prospective-only quashing orders

- reversing the judgment in R (Cart) v The Upper Tribunal so that decisions of the Upper Tribunal are no longer eligible for judicial review

It also makes a number of procedural changes across the court system.

Throughout the legislative passage of the Judicial Review and Courts Act, we engaged with parliamentarians to ensure the voices of solicitors were heard.

This resulted in a proposed statutory presumption being removed from the final law. The presumption would have required judges to award the new suspended and prospective quashing orders widely.

The removal of the presumption was a major win and the result of almost two years of campaigning and engagement. We believe it improves the act by maintaining judicial discretion as to which remedies are awarded. It also reduces the potential for negative impacts arising from the new remedies.

The act does, however, still makes significant changes to:

- the remedies that are available following a successful case, and

- what can be challenged in a judicial review case

Suspended quashing orders

The new power for courts to suspend a quashing order allows the order to take effect at a later date.

We believe this new remedy, if used in exceptional cases, will enhance flexibility and allow the interests of claimants and defendants to be balanced when awarding remedies in judicial review.

Prospective-only quashing orders

A prospective-only quashing order stops a decision or action of a public body from applying in the future, meaning they only apply to past events prior to the court judgment.

As a result, any previous uses of the decisions, despite being found to be unlawful, would be upheld.

We still have some concerns that this could prevent a successful claimant, and anyone else affected by the unlawful decision, from receiving a full remedy.

However, by leaving their use up to the discretion of judges, we hope the orders will only be used where strictly necessary and in a way that does not unfairly disadvantage the claimant.

Removing decisions of the Upper Tribunal from judicial review

A decision of the Upper Tribunal can no longer be judicially reviewed.

We still have some concerns that important points of law or procedural fairness, which would otherwise have been considered by the High Court, could be left unaddressed.

What we’re doing

April 2022 – we engaged with the government, securing an agreement to remove the statutory presumption from the bill , and the bill received royal assent

April 2022 – we raised our concerns with the UN in a submission to the universal periodic review of the UK (PDF 270 KB)

February 2022 – we put together a parliamentary briefing ahead of the second reading in the House of Lords

January 2022 – we heard from members of the public about the power of judicial review and their experiences with the process

October 2021 – we put together a parliamentary briefing ahead of the second reading in the House of Commons

April 2021 – we responded to the Ministry of Justice judicial review reforms consultation

October 2020 – we responded to the Independent Review of Administrative Law call for evidence on a range of aspects of judicial review

September 2020 – we held a roundtable of expert solicitors to discuss the Independent Review of Administrative Law’s terms of reference and develop our list of fundamental principles

Get involved

We’ll be monitoring the effects of the Judicial Review and Courts Act to ensure any negative consequences are brought to the attention of law makers.

If you've represented a client where any of the new measures have caused concern, email our policy advisor Hazel Blake .

Maximise your Law Society membership with My LS

- Human rights

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About International Journal of Constitutional Law

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. the problem of legitimacy and the institutional dialogue theory, 2. two conceptions of dialogue, 3. dialogue as deliberation and the doctrine of judicial responsibility, 4. dialogue as deliberation and the legitimacy of judicial review, 5. dialogue as conversation and the legitimacy of judicial review, 6. conclusion.

- < Previous

The legitimacy of judicial review: The limits of dialogue between courts and legislatures

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Luc B. Tremblay, The legitimacy of judicial review: The limits of dialogue between courts and legislatures, International Journal of Constitutional Law , Volume 3, Issue 4, October 2005, Pages 617–648, https://doi.org/10.1093/icon/moi042

- Permissions Icon Permissions

According to the theory of “institutional dialogue,” courts and legislatures participate in a dialogue aimed at achieving the proper balance between constitutional principles and public policies and the existence of this dialogue constitutes a good reason for not conceiving of judicial review as democratically illegitimate. This essay sets out to demonstrate that there are important limits to the capacity of insitutional dialogue to legitimize the institution of judicial review. To that end, it situates the theory of institutional dialogue within the debate over the legitimacy of judicial review of legislation within democracy and introduces a distinction between two conceptions of dialogue—dialogue as deliberation and dialogue as conversation—and examines the limits of each theory. The author does not contend that there can be no dialogue between courts and legislatures but, rather, that the kind of dialogue that would be needed to confer legitimacy on the institution and practice of judicial review does not—and cannot—exist. Consequently, the normative character of institutional dialogue theory, as conceived thus far, is ultimately rhetorical.

The theory of institutional dialogue, as I shall understand it, has been put forward by Peter Hogg and Allison Thornton in Peter W. Hogg & Allison A. Bushell, The Charter Dialogue Between Courts and Legislatures (Or Perhaps the Charter of Rights Isn't Such A Bad Thing After All) , 35 O sgoode H all L.J. 75 (1997). See infra , section I.

I briefly recall the nature of this objection below, in section I.

Part I of the Constitution Act, 1982, being Schedule B to the Canada Act, 1982, 1982, c. 11 (U.K.) [hereinafter “the Charter”].

Section one provides: “The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees the rights and freedoms set out in it subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.” The justificatory tests have been expounded by the Supreme Court in R. v. Oakes , [1986] 1 S.C.R. 103.

Section 33 provides: “(1) Parliament or the legislature of a province may expressly declare in an Act of Parliament or of the legislature, as the case may be, that the Act or a provision thereof shall operate notwithstanding a provision included in section 2 or sections 7 to 15 of this Charter.…(3) A declaration made under subsection (1) shall cease to have effect five years after it comes into force or on such earlier date as may be specified in the declaration. (4) Parliament or the legislature of a province may re-enact a declaration made under subsection (1). (5) Subsection (3) applies in respect of a re-enactment made under subsection (4).”

See, e.g. , Mark Tushnet, Judicial Activism or Restraint in a Section 33 World , 53 U. Toronto L.J. 89 (2003).

See, e.g. , Jü rgen H abermas , M oral C onsciousness and C ommunicative A ction (Christian Lenhart & Shierry Weber Nicholson trans., MIT Press 1991); Jü rgen H abermas , B etween F acts and N orms (William Rehg trans., MIT Press 1996); Bruce Ackerman, Why Dialogue? , 86 J. P hil . 5 (1989). See generally , D eliberative D emocracy : E ssays O n R eason and P olitics (James Bohman & William Rehg eds., MIT Press 1997).

See, e.g. , G rundgesetz (German Basic Law), adopted in 1949; C onst . S. A fr ., adopted in 1993; and the Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, Nov. 4, 1950, E.T.S. 5.

See, e.g. , the American doctrine of due process of law and the tests articulated by the American Supreme Court as required by various levels of scrutiny.

My colleague Jean Leclair also concludes, for other reasons, that the theory is merely rhetorical. See Jean Leclair, Reflexions critiques au sujet de la métaphore du dialogue en droit constitutionnel canadien [ Critical reflections on the metaphor of dialogue in Canadian constitutional law ], 2003 Revue du Barreau (Numéro special) 379, 402–412.

See, R obert B ork , T he T empting of A merica (MacMillan 1990) (source-based/originalism); J ohn H art E ly , D emocracy and D istrust (Harvard Univ. Press 1980) (process-based/pluralist-utilitarian democracy); R onald D workin , F reedom ' s L aw (Harvard Univ. Press 1996) (substance-based/egalitarian moral theory).

It ought not be forgotten that the historic decision to entrench the Charter in our Constitution was taken not by the courts but by the elected representatives of the people of Canada. It was those representatives who extended the scope of constitutional adjudication and entrusted the courts with this new and onerous responsibility. Adjudication under the Charter must be approached free of any lingering doubts as to its legitimacy. 12

Motor Vehicle Act , [1985] 2 S.C.R. 486, 497.

Marbury v. Madison , 5 U.S. (1 Cranch) 137 (1803); Chief Justice Marshall said that “the people have an original right to establish for their future government such principles as, in their opinion, shall most conduce to their own happiness” and that “all those who have framed written constitutions contemplate them as forming the fundamental and paramount law of the nation, and, consequently, the theory of every such government must be, that an act of the legislature, repugnant to the constitution, is void.” Id. at 176–177.

The phrase is borrowed from Bruce Ackerman, The Storrs Lectures: Discovering the Constitution , 93 Y ale L.J. 1013 (1984). Indeed, this argument might not hold when the legislation has been enacted prior to the enactment of the constitution.

Id .; see also B ruce A ckerman , W e T he P eople : F oundations (Belknap Press of Harvard Univ. Press 1991).

See, e.g. , A lexander B ickel , T he L east D angerous B ranch 24 (Yale Univ. Press 1962).

I have put forward certain criticisms in Luc B. Tremblay, General Legitimacy of Judicial Review and the Fundamental Basis of Constitutional Law , 23 O xford J. L eg . S tud . 525, 534–538 (2003).

I have explored this theme in various texts. See, e.g. , Luc B. Tremblay, L'interprétation téléologique des droits constitutionnels [ Teleological interpretation in constitutional law ], 29 R ev . J urid . T h é mis 459 (1995); Luc B. Tremblay, Marbury v. Madison and Canadian Constitutionalism: Rhetoric and Practice , 37 R ev . J urid . T h é mis 375 (2003). More generally, see Luc B. Tremblay, Le droit a-t-il un sens? Réflexions sur le scepticisme juridique [ Does the law have direction? Reflections on legal skepticism ], 42 R evue I nterdisciplinaire D'é tudes J uridiques 13 (1999).

Finally, even if the constitution were democratically superior to ordinary legislation, it would not necessarily follow that judges should have the power to review legislation. Insofar as political legitimacy is a matter of democratic pedigree, it seems to follow that the legislatures, not the courts, should be morally entitled to make the final decisions with respect to constitutional interpretation and application—for the very reason that they best represent the people. These strategies seem to require legislative supremacy even as they actually seek to legitimize judicial supremacy.

For a very good overview of different theories of institutional dialogue for the purposes of constitutional theory, see K. Roach, Constitutional and Common Law Dialogues Between the Supreme Court and Canadian Legislatures , 80 C an . B. R ev . 481, 490–501 (2001). See also K ent R oach , T he S upreme C ourt on T rial : J udicial A ctivism or D emocratic D ialogue (Irwin Law 2001).

See Hogg & Bushell, supra note 1. This version has been refined or endorsed by various scholars. See, e.g. , Roach, supra note 19; A.Wayne MacKay, The Legislature, The Executive and the Courts: The Delicate Balance of Power or Who is Running the Country Anyway? , 24 D alhousie L.J. 37 (2001).

Hogg and Bushell, supra note 1, at 79.

Section 33: “(1) Parliament or the legislature of a province may expressly declare in an Act of Parliament or of the legislature, as the case may be, that the Act or a provision thereof shall operate notwithstanding a provision included in section 2 or sections 7 to 15 of this Charter.… (3) A declaration made under subsection (1) shall cease to have effect five years after it comes into force or on such earlier date as may be specified in the declaration. (4) Parliament or the legislature of a province may re-enact a declaration made under subsection (1). (5) Subsection (3) applies in respect of a re-enactment made under subsection (4).”

Section one provides: “The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees the rights and freedoms set out in it subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.”

For example, section 7 provides: “Everyone has the right to life, liberty and security of the person and the right not to be deprived thereof except in accordance with the principles of fundamental justice.” Section 8 states: “Everyone has the right to be secure against unreasonable search or seizure.”

Section 15 provides: “(1) Every individual is equal before and under the law and has the right to the equal protection and equal benefit of the law without discrimination and, in particular, without discrimination based on race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability. (2) Subsection (1) does not preclude any law, program or activity that has as its object the amelioration of conditions of disadvantaged individuals or groups including those that are disadvantaged because of race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, sex, age or mental or physical disability.”

According to Hogg and Thornton, the empirical evidence supporting institutional dialogue refutes “the critique of the Charter based on democratic legitimacy.” 26 Indeed, where a judicial decision striking down a law on Charter grounds can be reversed, modified, or avoided by a new law, “any concern about the legitimacy of judicial review is greatly diminished.” 27 The objection founded on the continuous character of democracy is refuted. While the courts may nullify legislation on the basis of past citizens' views, their decisions almost always leave room for contemporary legislative responses. Similarly, the objection from indeterminacy loses its point. Even if the judges were “activist” and enforced values either not consistent with an “original” understanding of the text or not objectively commanded by the text, the legislatures would normally be able to devise a response “which accomplishes the social or economic objectives that the judicial decision has impeded.” 28 Finally, the objection from judicial supremacy is much weaker than generally thought. While the courts may nullify legislation on the basis of their own formal or substantive understanding of constitutional principles and purposes, the legislatures may almost always reverse, modify, or avoid their decisions. Thus, as already noted, the courts would not have the last word concerning the proper balance between individual interests and social policies, and the constitution would not necessarily be whatever the courts say it is.

To be sure, the Court may have forced a topic onto the legislative agenda that the legislative body would have preferred not to have to deal with. And, of course, the precise terms of any new law would have been powerfully influenced by the Court's decision. The legislative body would have been forced to give greater weight to the Charter values identified by the Court in devising the means of carrying out the objectives, or the legislative body might have been forced to modify its objectives to some extent to accommodate the Court's concerns. These are constraints on the democratic process, no doubt, but the final decision is the democratic one. 32

Hogg and Bushell, supra note 1, at 105.

Id . at 81.

Id . at 105.

See Roach, supra note 19, at 530–531.

Id . at 531.

Id. at 532.

As I view the matter, the Charter has given rise to a more dynamic interaction among the branches of governance. This interaction has been aptly described as a “dialogue” by some. 39 In reviewing legislative enactments and executive decisions to ensure constitutional validity, the courts speak to the legislative and executive branches. As has been pointed out, most of the legislation held not to pass constitutional muster has been followed by new legislation designed to accomplish similar objectives (see Hogg and Bushell, supra , at p. 82). By doing this, the legislature responds to the courts; hence the dialogue among the branches. 38 [1998] 1 S.C.R. 493, paras. 138–139. 39 See, e.g. , Hogg & Bushnell, supra note 1. To my mind, a great value of judicial review and this dialogue among the branches is that each of the branches is made somewhat accountable to the other. The work of the legislature is reviewed by the courts and the work of the court in its decisions can be reacted to by the legislature in the passing of new legislation (or even overarching laws under s. 33 of the Charter ). This dialogue between and accountability of each of the branches have the effect of enhancing the democratic process, not denying it. 40

[1998] 1 S.C.R. 493, paras. 138–139.

As a result of the consultation process, Parliament decided to supplement the “likely relevant” standard for production to the judge proposed in O'Connor with the further requirement that production be “necessary in the interests of justice.” The result was s. 278.5. This process is a notable example of the dialogue between the judicial and legislative branches discussed above. This Court acted in O'Connor , and the legislature responded with Bill C-46. As already mentioned, the mere fact that Bill C-46 does not mirror O'Connor does not render it unconstitutional. 46

[1999] 3 S.C.R. 668.

Id. at para. 57.

Bill C-46, S.C. 1997, c. 30. It came into force on May 12, 1997 and amended the Criminal Code, R.S.C., 1985, c. C-46.

[1995] 4 S.C.R. 411.

Mills , supra note 40, at para. 20.

Id. at para. 125.

See, e.g. , Justice Bastarache in M. v. H. , [1999] 2 S.C.R. 3, paras. 286, 328; Justice L'Heureux-Dubé in Corbiere v. Canada (Minister of Indian and Northern Affairs) , [1999] 2 S.C.R. 203, para. 116; Justice Gonthier in Sauvé v. Canada (Chief Electoral Officer) , [2002] 3 S.C.R. 519, paras. 104–108; Justice Major in Harper v. Canada (Attorney General) , [2004] 1 S.C.R. 827, para. 37.

Christopher P. Manfredi & J. B. Kelly, Six Degrees of Dialogue: A Response to Hogg and Bushell , 37 O sgoode H all L.J. 513 (1999). See also C hristopher P. M anfredi , J udicial P ower and The C harter 176–181 (Oxford Univ. Press 2d ed. 2001).

Manfredi, supra note 47, at 520–521. For similar criticisms, see F. L. M orton and R ainer K nopff , T he C harter R evolution & T he C ourt P arty 162–166 (Broadview Press 2000). In their view, the dialogue “is usually a monologue, with judges doing most of the talking and legislatures most of the listening.” Id. at 166. See also Tushnet, supra note 6.

Manfredi, supra note 47, at 515.

Id . at 522.

Id. at 524. See also M anfredi , supra note 47, at 178–181. This form of “genuine dialogue” corresponds to what other authors have called “coordinate construction.” See Roach, supra note 19, at 529. See also Dennis Baker & Rainer Knopff, Minority Retort: A Parliamentary Power to Resolve Judicial Disagreement in Close Cases , 21 W indsor Y.B. A ccess J ust . 347 (2002)(they clearly argue in favour of “coordinate interpretation”). See also David Schneiderman, Kent Roach, the Supreme Court on Trial: Judicial Activism or Democratic Dialogue , 21 W indsor Y.B. A ccess J ust . 633 (2002); J anet L. H iebert , C harter C onflicts : W hat is P arliament's R ole ? 202 (McGill-Queen's Univ. Press)(proposing to conceive the shared responsibility with respect to constitutional interpretation in “relational” terms, instead of in terms of dialogue); Tushnet, supra note 6.

See, e.g., Roach, supra note 19; Baker & Knopff, supra note 51; Christopher P. Manfredi & James B. Kelly, Dialogue, Deference and Restraint: Judicial Independence and Trial Procedures , 64 S ask . L. R ev . 323 (2001).

The precedent established a common law procedure on the basis of Charter's values . See, supra notes 37–42.

Jamie Cameron, Dialogue and Hierarchy in Charter Interpretation: A Comment on R. v. Mills , (2000) 38 ALTA. L. REV. 1051 (2001).

Id. at 1067.

Id . at 1063.

Id . at 1060.

Id . at 1068. According to Cameron, “either the Constitution is supreme or it is not. If it is supreme, Parliament could only overrule O'Connor, legislatively, by invoking s. 33. On that view, the Court's choices in Mills were to overrule O'Connor or to strike down parts of the legislation. Alternatively, if constitutional interpretation is not supreme, then s. 33 serves little purpose because the Court's interpretations of the Charter are collapsed into the political process.” Id . at 1062–1063. For similar criticisms, see Roland Penner, Charter Conflicts: What is Parliament's Role? , 28 Q ueen 's L.J. 731 (2003); Leclair, supra note 10, at 402–412; David M. Paciocco, Competing Constitutional Rights in the Age of Deference: A Bad Time to be Accused , 14 S up . C t . L. R ev . (2d) 111 (2001); Don Stuart, Mills: Dialogue with Parliament and Equality by Assertion at What Cost? , 28 C rim . R ep . (5th) 275 (1999).

Leclair, supra note 10.

Id . at 395–402.

The phrase “judicial minimalism” can be associated with Cass Sunstein's works. See C ass S unstein , O ne C ase at a T ime : J udicial M inimalism on T he S upreme C ourt (Harvard Univ. Press 1999). Judicial Minimalism is similar in principle to Alexander Bickel's “passive virtues”. See Bickel, supra note 16.

Leclair, supra note 10, at 412–420. Leclair's criticisms and reflections use the application of the “reading in” doctrine of Vriend as his main target.

See, for example, Peter W. Hogg & Allison A. Thornton, Reply to “Six Degrees of Dialogue” , 37 O sgoode H all L.J. 529 (1999); Manfredi & Kelly, supra note 52. For further refinements, see, for example, Kent Roach, American Constitutional Theory for Canadians (And the Rest of the World) , 52 U. T oronto L.J. 503 (2002); Kent Roach, Remedial Consensus and Dialogue Under the Charter: General Declarations and Delayed Declarations of Invalidity , 35 U. B. C. L. R ev . 211 (2002).

That a dialogue between the legislature and the court could legitimize the institution of judicial review in a democracy is a powerful and appealing notion. Yet, the theory of institutional dialogue is problematical. In order to see why, it is necessary to clarify what is meant by “dialogue” as the idea pertains to the legitimization of judicial review. In a general sense, a dialogue assumes that two or more persons, recognized as equal partners, exchange words, ideas, opinions, feelings, emotions, intentions, desires, judgments, and experiences together within a shared space of intersubjective meanings. But there are various kinds of dialogue. In what follows, I will introduce two distinct conceptions of dialogue.

In the first instance, the word dialogue can be used to describe a conversation. In this sense, a dialogue involves at least two persons, recognized as equals, exchanging words, ideas, opinions, feelings, and so forth together in rather informal and spontaneous ways. In a conversation, the participants have no specific practical purpose other than the general goal of exploring or creating a common world and body of meanings, learning something new about others, or discovering new perspectives. Discussions with friends over a meal are generally of this kind. We exchange points of view on a plurality of subjects freely, with no specific goal, no timetable, no strong debate and argumentation, and, sometimes, with humorous comments. A dialogue as conversation can be more or less successful, depending on the degree of mutual understanding. In order to be successful, the participants must encounter each other in a shared world through a common language. This presupposes cooperation. Each participant must have an interest in, and a serious commitment to, what the others have to say. A conversation may fail, therefore, when the participants talk at cross-purposes or when they do not truly open themselves to the others or to what they have to say. I shall call this form of dialogue a “dialogue as conversation.”

Since a dialogue as “informal” conversation has no specific practical purpose, it does not aim at taking a collective decision; reaching agreement; solving problems or conflicts; persuading others that a given opinion or thesis is true, the most justified, or the best; or determining together which particular view should govern actions or decisions. For this reason, a dialogue as conversation has no practical outcome to legitimize. Of course, it may possess some normative value; however, it possesses no legitimating value. Nevertheless, however informally it proceeds, a successful conversation may have an impact, however minimal, on the life of the participants. If I talked to someone who told me that she loves the tango or is keen to rent a villa in the city of Florence, our conversation may have provoked in my mind new interests, such as taking tango lessons or going to Florence next summer. But the purpose of our conversation was not the organization of my spare time or my next holiday. It would not be a failure if no such consequences followed from our dialogue, and if I stuck to my original plan to take Spanish lessons or to go to Istanbul.

See the various essays in Deliberative Democracy, supra note 7.

No dialogue as deliberation could operate or sustain itself unless it satisfies certain conditions. First, each participant must recognize the other as an equal partner. Each participant must be equally entitled to put forward theses, to make proposals, to defend particular options, and to take part in the final decision. No one should be excluded from the dialogue, no one should impose by fiat where the dialogue should lead, and no hierarchy must confer in advance on one or more of the participants the authority to settle the disagreements. Second, a dialogue as deliberation must be a process of rational persuasion, not a form of coercion. Accordingly, the participants must have good reason to believe that the positions they defend are true, justified, or best, and they must try to convince the others of the force of their position. Yet, a dialogue as deliberation is not a debate one must absolutely win or in which one's views must absolutely prevail. Considering the specific common practical goals, each participant must be willing to expose their views to the critical analysis of the others and must be ready to change them if others put forth better arguments. Otherwise, the dialogue would not be a deliberation: the participants would stick to their original views and the dialogue would be a form of conversation. Third, a dialogue as deliberation must aim at producing some practical judgment, action, or decision that can be the object of reasoned agreements among the participants. Thus, the participants must justify their positions according to rules of evidence and argument that are, in principle, acceptable to all others. They must take into account each other's perspective and try to incorporate them into their own views. Of course, in particular cases, the pressure of time or the nature of the reasons may make it impossible for the participants to reach rational agreement. In these cases, they must agree to disagree. Nevertheless, the process of dialogue as deliberation must be constrained by this regulative ideal: any outcome must be the result of free and reasoned agreement (or disagreement) among the participants recognized as equal partners. Otherwise, the deliberation would not hold and the dialogue would be a form of conversation.

This conception of dialogue as deliberation has an obvious connection with much contemporary theories of deliberative democracy. My own contribution to this question is found in Luc B. Tremblay, Deliberative Democracy and Liberal Rights , 14 R atio J uris 424 (2001). See generally , Deliberative Democracy: Essays on Reason and Politics, supra note 7.

The theory of institutional dialogue claims that judicial review is democratically legitimate because it constitutes “part” of a dialogue between the courts and the legislatures. But what kind of dialogue is presupposed by this theory? That is, which dialogue confers democratic legitimacy on judicial review—dialogue as conversation or dialogue as deliberation? Considering what has just been said, the answer is likely to be the latter, for only this form of dialogue seems to possess legitimating force. Dialogue as deliberation seeks to make collective decisions, to settle practical conflicts, and to reach agreements. It seems to be specifically designed to confer legitimacy on some practical outcome. Consequently, one might reasonably argue that this form of dialogue, qua dialogue, could legitimize judicial review and courts nullifying legislation, provided that such dialogue satisfies the conditions that confer legitimacy on the results: equality, rationality, and reasoned agreement.