- Increase Font Size

7 Classification and Description of Speech Sounds: English Consonants

Dr. Chhaya Jain

The concept that speech is primary and writing is secondary has changed the way of English Language Teaching. This chapter deals with speech sounds and classification of speech sounds in relation with consonants.

Being able to describe a consonant sound has many benefits.

- If you’re teaching English as a second language, knowing how consonants are pronounced will help you to show your students where and how to make the sounds themselves.

- If you’re a student learning English as a second language, you’ll be able to sound more like a native English speaker if you know how and where English consonants are made.

- If you’re a therapist, you’ll be able to help your patients to produce the sounds.

Speech Sounds: Meaning and Definition

Because sounds are present in all languages regardless of orthography, linguists needed a way to represent the same sounds in different languages, no matter in which language they occur. Sounds are described not by how they sound to the ear, but rather how they are produced in the vocal tract. Sounds are produced my moving the articulators (things that can be moved) within the vocal tract (lips, tongue, etc). Speech involves producing sounds from the voice box. In English, there are no one- to -one relations between the system of writing and the system of pronunciation. The alphabet, which we use to write English, has 26 letters but in English speech sounds are approximately 44.The number of speech sounds in English varies from dialect to dialect.

To represent the full spectrum of sounds without using different orthographic systems, a universal alphabet of sounds has been developed. Let’s not forget that Phonemes in oral languages are not physical sounds, but mental abstractions of speech sounds. A phoneme is a family of speech sounds (phones) that the speakers of a language think of as being, and usually hear as, the same sound. A perfect alphabet is the one that has one symbol for each phoneme. The IPA, or International Phonetic Alphabet uses a single symbol for each specific sound. Sometimes these symbols match the letters in English, which represent these sounds. Sometimes they do not.

English Phonemes

Infants begin making sounds at birth; those early sounds in the form of cries can be easily recognized. As the infant continues to mature, cooing and babbling noises develop into consonants and vowel sounds. These early pre-consonantsand pre vowel sounds gradually become shaped into words. But phoneme development in neonates for purpose of speech generally begins between the first and second birthdays.

Phoneme is the basic linguistic unit, denoted by a character enclosed with forward slashes or square braces (e.g. the symbol /i/ represents the vowel sound heard in the word team ). Phonemes may be classified and described according to a number of criteria. They may be divided, for example, into vowels and consonants. In a language the number of phonemes is fixed. Meaning depends heavily on the inter- relationship of phonemes and morphemes. That’s why modern linguistics studies language as a system. It studies phonemes at the lowest level and sentences at the highest level through syllables, morphemes, words and phrases.

In PHONETICS, consonants are discussed in terms of three anatomical and physiological factors:

- The state of the glottis (whether or not there is VOICE or vibration in the larynx),

- The place of articulation (that part of the vocal apparatus with which the sound is most closely associated),

- And the manner of articulation (how the sound is produced).

Articulators above the larynx

All the sounds we make when we speak are the result of muscles contracting. The muscles in the chest that we use for breathing produce the flow of air that is needed for almost all speech sounds; muscles in the larynx produce many different modifications in the flow of air from the chest to the mouth. After passing through the larynx, the air goes through what we call the vocal tract , which ends at the mouth and nostrils; we call the part comprising the mouth the oral cavity and the part that leads to the nostrils the nasal cavity . Here the air from the lungs escapes into the atmosphere. We have a large and complex set of muscles that can produce changes in the shape of the vocal tract, and in order to learn how the sounds of speech are produced it is necessary to become familiar with the different parts of the vocal tract. These different parts are called articulators , and the study of them is called articulatory phonetics .

The pharynx is a tube, which begins just above the larynx. It is about 7 cm long in women and about 8 cm in men, and at its top end it is divided into two, one part being the back of the oral cavity and the other being the beginning of the way through the nasal cavity. If you look in your mirror with your mouth open, you can see the back of the pharynx.

ii) The soft palate or velum is in a position that allows air to pass through the nose and through the mouth. Often in speech it is raised so that air cannot escape through the nose. The other important thing about the soft palate is that it is one of the articulators that can be touched by the tongue. While making the sounds k, À the tongue is in contact with the lower side of the soft palate, and we call these velar consonants.

iii) The hard palate is often called the “roof of the mouth”. Its smooth curved surface can be felt with the tongue. A consonant made with the tongue close to the hard palate is called palatal . The sound j in ‘yes’ is palatal.

iv) The alveolar ridge is between the top front teeth and the hard palate. Its shape can be felt with the tongue. These can be only seen by dentists with the help of a very small mirror used by them. Sounds made with the tongue touching here (such as t, d, n) are called alveolar .

v) The tongue is a very important articulator and it can be moved into many different places and different shapes. It is usual to divide the tongue into different parts, though there are no clear dividing lines within its structure: tip , blade , front , back and root . (This use of the word “front” often seems rather strange at first.)

vi) The teeth (upper and lower) are shown at the front of the mouth, immediately behind the lips. The tongue is in contact with the upper side teeth for most speech sounds. Sounds made with the tongue touching the front teeth, such as English are called dental .

vii .The lips are important in speech. They can be pressed together (when we produce the sounds p, b), brought into contact with the teeth (as in f, v), or rounded to produce the lip-shape for vowels like uà. Sounds in which the lips are in contact with each other are called bilabial , while those with lip-to-teethcontact are called labiodental .

English Consonants and their importance

- Consonant is a speech sound produced by completely or partly stopping the air being breathed out through the mouth.(Hornby: Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary).

- Consonant is a speech sound which is pronounced by stopping the air from flowing easily through the mouth, especially by closing the lips or touching the teeth with the tongue. (Cambridge University Press. : Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary).

- IPA (International Phonetics Alphabets) describes English consonants based on: A. Voicing; B. Place of articulation; and C. Manner of articulation.

A consonant is a speech sound that is articulated with complete or partial closure of the vocal tract. Examples are :

- [p], pronounced with the lips;

- [t], pronounced with the front of the tongue;

- [k], pronounced with the back of the tongue;

- [h], pronounced in the throat;

- [f] and [s], pronounced by forcing air through a narrow channel (fricatives); and

- [m] and [n], which have air flowing through the nose (nasals).

Since the number of possible sounds in all of the world’s languages is much greater than the number of letters in any one alphabet, linguists believe (IPA) to be a unique and unambiguous symbol to each attested consonant. In fact, the English alphabet has fewer consonant letters than English has consonant sounds, so digraphs like “ch”, “sh”, “th”, and “zh” are used to extend the alphabet, and some letters and digraphs represent more than one consonant. For example, the sound spelled “th” in “this” is a different consonant than the “th” sound in “thin”. (In the IPA, they are transcribed [ð] and [θ], respectively.)

Contrasting with consonants are vowels that we will study in the next chapter.

Questions Regarding Consonants: In the case of consonantal articulations, a description must provide answers to the following questions:

- Is the airstream set in motion by the lungs or by some other means? ( pulmonic or non-pulmonic )

- Is the airstream forced outwards or sucked inwards? ( egressive or ingressive )

- Do the vocal folds vibrate or not? ( voiced or voiceless )

- Is the soft palate raised, directing the airstream wholly through the mouth, or lowered, allowing the passage of air through the nose? ( oral, or nasal or nasalized )

- At what point or points and between what organs does closure or narrowing take place? ( place of articulation )

- What is the type of closure or narrowing at the point of articulation? (manner of articulation)

Classification and Description of Speech Sounds

- While primarily the vibration of the vocal folds produces vowels, consonants are the speech sounds produced by the turbulent or explosive flow of air through constricted or obstructed parts of the vocal tract, known as articulators.

- A complete description should include: the production , transmission , and reception stages .The most convenient and brief descriptive technique continues to rely on articulatory criteria (consonants ) or on auditory judgements ( vowels ), or on a combination of both.

Describing Consonant Sounds

Consonant sounds are described by 3 things:

- Is the sound voiced or voiceless? VOICING

- Where is the sound constricted? PLACE OF ARTICULATION

- How is the airstream constricted? MANNER OF ARTICULATION

Let us deal these facts in details.

Step 1: The first thing to state in describing a consonant is to indicate whether the sound is VOICED or VOICELESS

- voice sounds = vocal folds vibrate

- voiceless sounds = vocal folds do not vibrate (try this: put your hand on your throat when you pronounce the sound. If you feel a vibration, the sound is voiced.)

Step 2: The second thing is to tell where in the vocal tract the sound is articulated (the place of articulation)

Step 3: The third thing is to say how the air stream is modified by the vocal tract to produce the sound (manner of articulation)

Voiced and Unvoiced Consonants: Consonants may also involve vibration of the vocal folds, as in the phoneme /v/, heard in the word voice . Such consonants are called voiced consonants, while consonants such as the /f/ of the word fish are referred to as unvoiced, since the vocal folds are simply held open during the production of these sounds.

The consonants may also be divided along a number of lines. Fricative consonants, or spirants, such as the aforementioned /f/ of fish and /s/ of sit , are marked by a steady, turbulent flow of air at a constriction created somewhere in the vocal tract other than at the vocal chords. Stop consonants, or plosives, on the other hand, such as the /p/ of push or the /g/ of goat , are produced by the build-up and sudden, explosive release of air pressure at some point in the vocal tract. Fricatives and stop consonants may be either voiced or unvoiced. Certain terms used in the description of speech sounds may be applied to both vowels and consonants.

Nasal sounds are those in which the nasal cavity plays a role in the transmission and broadcast of the vocal sound, whereas non-nasal sounds occur when the nasal cavity is cut off from the vocal tract by the velum during sound production. Continuants are those speech sounds that involve the continuous, steady flow of air from lungs to the environment, while stops involve the complete closure or obstruction of the vocal cavities at some point in the production of the sound.

Finally, there are some classes of phonemes that do not fit neatly into the vowel- consonant classification scheme described above. The sounds /l/, /r/, /m/, /n/, and /ng/, for example, though often thought of as consonants, are referred to as liquids or semi- vowels. The sounds /w/, /y/, and /h/ are referred to as transitionals in [ Fletcher 1953 ]. Speech sounds referred to as affricates consist of a plosive or stop consonant immediately followed by a fricative or spirant, such as the German .

Place of Articulation

Bilabial – uses both lips to create the sound such as the beginning sounds in pin, bust, well and the ending sound in seem .

Labiodental – uses the lower lip and upper teeth; examples include fin and van.

Dental/interdental – creates sound between the teeth such as the and thin.

Alveolar – is a sound created with the tongue and the ridge behind the upper teeth; examples include the beginning sounds of tin, dust, sin, zoo, and late and the /n/ in scene.

Palatal – uses the tongue and the hard palate to create the following sounds: shin, treasure, cheep, jeep, rate and yell.

Velar – makes the sound using the soft palate in the back of the mouth; sounds include kin, gust, and the -ng in sing .

Glottal – is a sound made in the throat between the vocal cords such as in the word hit Manner of Articulation

The manner of articulation means how the sound is made using the different places of articulation, tongue placement, whether the sound is voiced or unvoiced and the amount of air needed.

Stops – air coming from the lungs is stopped at some point during the formation of the sound. Some of these sounds are unvoiced, such as pin, tin, and kin; some of these are voiced, such as bust, dust and gust.

Fricatives – restricted air flow causes friction but the air flow isn’t completely stopped. Unvoiced examples include fin, thin, sin, shin, and hit; voiced examples include van, zoo, the, and treasure .

Affricates – are combinations of stops and fricatives. Cheap is an example of an unvoiced affricate and jeep is an example of a voiced. An affricate is a consonant which begins as a stop (plosive), characterized by a complete obstruction of the outgoing airstream by the articulators, a buildup of air pressure in the mouth, and finally releases as a fricative, a sound produced by forcing air through a constricted space, which produces turbulence when the air is forced through a smaller opening. Depending on which parts of the vocal tract are used to constrict the airflow, that turbulence causes the sound produced to have a specific character (compare pita with pizza, the only difference is the release in /t/ and /ts/). There are two types of affricate in English. For an interactive example of each sound (including descriptive animation and video), click this link, then in the window that opens, click affricate, and select the appropriate sound.

Nasals – as expected, the air is stopped from going through the mouth and is redirected into the nose. Voiced examples include seem, seen, scene, and sing.

Liquids – almost no air is stopped; voiced exampled included late and rate.

Glides – sometimes referred to as “semi-vowels,” the air passes through the articulators to create vowel like sounds but the letters are known as consonants. Examples include well and yell.

Consonant Classification Chart

A consonant classification chart shows where the different consonant sounds are created in the mouth and throat area. This is important especially when trying to help children or adults learn to speak properly if they have speech problems.

A consonant classification chart shows where in the mouth different consonant sounds derive and how much air is needed to create the sounds. For this reason, the chart often has the location of the sound (place) across the top and the way the sound is produced (manner) down the side.But before that I will like to quote

‘’To summarize, the consonants we have been discussing so far may be described in terms of five factors: 1. state of the vocal folds (voiced or voiceless); 2. place of articulation; 3. central or lateral articulation; 4. soft palate raised to form a velic closure (oral sounds) or lowered (nasal sounds); and 5. manner of articulatory action. Thus, the consonant at the beginning of the word sing is a (1) voiceless, (2) alveolar, (3) central, (4) oral, (5) fricative; and the consonant at the end of sing is a (1) voiced, (2) velar, (3) central, (4) nasal, (5) stop. On most occasions, it is not necessary to state all five points. Unless a specific statement to the contrary is made, consonants are usually presumed to be central, not lateral, and oral rather than nasal. Consequently, points (3) and (4) may often be left out, so the consonant at the beginning of sing is simply called a voiceless alveolar fricative. When describing nasals, point (4) has to be specifically mentioned and point (5) can be left out, so the consonant at the end of sing is simply called a voiced velar nasal.’’

The Consonant Chart

Consonant Cluster: “A cluster is when two or more consonants of different places of articulation are produced together in the same syllable.”(Source: Linda I. House – Introductory Phonetics and Phonology) Note that clusters are determined based on the sounds, not the letters of the words. Initial clusters are usually formed by combining various consonants with the /s/, /r/, or /l/ phonemes. Examples: sleep [sli:p], green [gri:n], blue [blu:]

Medial clusters usually appear at the beginning of a second or third syllable in a multisyllabic word. Examples: regret [rɪgret], apply [əplaɪ], approve [əpru:v]• Final clusters are usually composed of a variety of phonemes including/sk/, /mp/, /ns/, /st/, and /ŋk/.Examples:desk [desk], camp [kæmp], mince [mɪns], fast [fɑ:st],bank [bæŋk].Clusters can appear in the initial, medial, or final positions of words.

Syllabically Uncertain Relationship With Speech Sounds:

We can notice l in apple, m in spasm, n in isn’t, r in centre. In such positions, they are often pronounced with a schwa preceding their consonant value. Most consonant letters are sometimes ‘silent’: that is, used with no sound value (some having lost it, others inserted but never pronounced); b in numb, c in scythe; comparably with handsome, foreign, honest, knee, talk, mnemonic, damn, psychology,

island, hutch, wrong, prix, key, laissez-faire. In general, consonant letters in English have an uncertain relationship with speech sounds.

Summary Let’s revise.

- Consonant is a speech sound produced by completely or partly stopping the air being breathed out through the mouth. (Hornby: Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary).

- Consonant is a speech sound which is pronounced by stopping the air from flowing easily through the mouth, especially by closing the lips or touching the teeth with the tongue. (Cambridge University Press.: Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary).

- English consonants are described by the IPA (International Phonetics Alphabets) based on: A. Voicing; B. Place of articulation; and C. Manner of articulation.

- Voicing: The aspects of voicing are: voiced consonants (those created by the vibration of the vocal cords during production); and voiceless consonants (those created by the absence of vibration of the vocal cords during production).

- In phonetic chart of the English consonants, where symbols appear in pairs, the one to the right represents a voiced consonant.

- Place of Articulation: Place of articulation refers to the places where the air stream from the lungs or the sound stream from the larynx is constricted (limited) by the articulators.

- Manner of Articulation: Manner of articulation refers to how the air stream from the lungs is directed to the mouth and modified by the various structures to produce a consonant phoneme.

- The Description of Manner of Articulation: Plosive Produced by the obstruction of air stream from the lungs followed by a release of the air stream. Such as: [p, b, t, d, k, g]

- Nasal Produced by the release of the air through the nasal cavity. Such as: [m, n, ŋ]

- Fricative Produced by the release of a „friction like noise‟ created by the airstream escaping through a variant of narrow gaps in the mouth. Such as: [f, v, θ, ð, s, z, ʃ, ʒ, h]

- Lateral Approximant Produced by the obstruction of the air stream at a point along the center of the oral track, with incomplete closure between one or both sides of the tongue and the roof of the tongue. Such as: [l]

- Approximant Produced by proximity (closeness) of two articulators without turbulence (hard movement and friction like noise).Such as: [w, ɹ (r), j]

Affricate Produced by involving more than one of those manners of articulation. Firstly, produce the sounds in the alveolar ridge, then followed by or combined with fricative sounds. Such as: [tʃ, dʒ] Thus the description of a consonant will include five kinds of information : (1) the nature of the air-stream mechanism; (2) the state of the glottis; (3) the position of soft palate (velum); (4) the articulators involved; and (5) the nature of the ‘stricture’.

- Chomsky, Noam (1998). On Language. The New Press, New York. ISBN 978- 1565844759 .

- Derrida, Jacques (1967). Of Grammatology. The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801858305 .

- Crystal, David (1990). Linguistics. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140135312 .

- Ladefoged, P. and Johnson, K. (2011) A Course in Phonetics (6th edn) Boston, MA: Wadsworth/Cengage Learning. P17

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 4: Phonology

Speech sounds, chapter preview, 4.1 introduction.

Any sound, whether used in speech or otherwise, can be characterised in terms of its quality. Sound quality refers to a specific set of acoustic properties that distinguishes one sound from another.

Being about language, this book is concerned with speech sounds , sounds produced by human beings for the purposes of linguistic communication. This definition encompasses the two branches into which the study of speech sounds divides:

- Phonetics deals with the articulatory capabilities of the vocal tract, and therefore with an ability shared by all human beings. These capabilities are the object of articulatory phonetics , the branch of phonetics that we deal with in this chapter. Articulatory phonetics studies how speech sounds are produced (articulated) in the human vocal tract. Auditory phonetics and acoustic phonetics constitute further sub-branches of phonetics, not dealt with this in this book. Auditory phonetics studies the mechanisms involved in speech audition, i.e. how listeners perceive speech sounds, while acoustic phonetics studies the physical characteristics of speech sounds.

- Phonology deals with sounds that serve linguistic purposes. These are sounds whose patterning conveys meaning. These sounds are recognised by speakers and listeners as linguistic signals in the language(s) that are available to them, and are therefore shared by speakers who share a language. We will look more closely at phonology in the next chapter.

In talking about sounds, we need to keep in mind that there is often no one- to-one correspondence between speech sounds and their spellings. So, we need to (re)train ourselves to listen to speech instead of reading printed forms of it. Here are a few examples of sound-spelling discrepancies in English. The words threw and through are pronounced in exactly the same way, as are knows and nose : when spoken out of context, we can’t tell which is “witch”. Conversely, the English letter sequence – ough has several different pronunciations, as in words like cough , dough or through , and the sound [k] can be spelt in at least eight different ways, as shown by the bolded letters of the following words:

(5.1) ta ck , c at, me ch anic, s q uid, bea k , a cq uire, a cc ordion, grotes que

A few more examples from English appear in the Food for thought section at the end of this chapter.

Activity 4.1

4.2 The production of speech sounds

In order to communicate through speech, human beings move the lower part of their faces, in a frenzy of rapidly shifting and very precise configurations. If you think of yourself as a lazy or slurred speaker, and would dismiss the word precise as inapplicable to you, just take some time to observe the tremendous effort that small children put into the task of training the muscles that command the production of speech: you also had to go through this painstaking workout of speech musculature, in order to be able to “slur” fluently.

The lower jaw, being mobile, stands for the visible part of speech configurations. The role of the lips in speech is clearly visible too, as is, at times, the configuration of the tip of the tongue and the teeth in the articulation of certain speech sounds. However, most speech configurations take place inside the oral cavity, anywhere along the vocal tract. They are therefore difficult to see, but fairly easy to feel. The bulk of this chapter is dedicated to showing you what it takes, and how it feels, to pronounce a range of common speech sounds.

4.2.1 The vocal tract

The vocal tract forms an inverted L-shaped tube that stretches from the larynx upwards to the lips. The angle of the L is at the back of your throat. The larynx , or the voice box , is located mid-way down the front of your neck. If you’re male, you may find that the so-called “Adam’s apple” of your larynx can be quite protruding. The vocal tract includes the nasal cavities, which are located inside and behind your nose, as optional resonator.

We normally speak while breathing out (you can try uttering a few words, or maintaining a conversation while breathing in, to get a feeling of how unnatural this is). This explains why speaking for long periods of time can be quite tiring. The repeated interruptions of the airflow that make speech possible disrupt the normal rhythm of breathing. Speech sounds are produced by means of modifications imposed on exhaled air, as it flows through the vocal tract. These modifications are brought about by movement of the articulators , each of the component organs and locations in the vocal tract that play a role in the production of speech sounds. Generally, the active articulators along the lower jaw move towards the passive articulators in the upper jaw. Both lips, lower and upper, can be active articulators.

Instead of providing you with the usual labelled diagram of the vocal tract found in most introductory material on phonetics, we offer in this chapter “hands-on” acquaintance with the basic anatomy and physiology of your oral cavity. We will show you around your own vocal tract, making it clear to you what goes on inside it when you speak. In the process, the reason why so many apparently obscure labels are needed for the description of speech sounds will, we hope, become clear to you. As a preliminary observation, keep in mind that just as we need different labels for words that behave differently, so we also need different labels for each of the vocal movements that produce a different speech sound.

In what follows, we provide you with a guided tour of your vocal tract, together with core speech configurations used in many languages, including English. In order to fully understand this chapter, you will need a mirror, a pencil or pen, and some privacy. Warn anyone near you not to panic at the noises you’ll be producing: phonetics must be practised, it cannot be learned otherwise. Better still, work through this chapter with a friend or two, willing to observe and be observed, and practise together! Just follow the Try the following trail.

4.2.2 Core speech configurations

Modifications along the length of the vocal tract affect its shape, and therefore its volume and resonance. Each modification thus produces a different sound. In this book, we deal with only a few of these modifications, most of which apply to most languages, including English. According to these modifications, speech sounds may be classified as voiced or voiceless , oral or nasal , and as vowels or consonants . We deal with each of these alternative articulations in turn.

Voiced vs. voiceless sounds

Try the following, gently touch the section of your larynx that slightly protrudes at the front of your neck. now say something like good morning , loud and clear. can you feel the vibration under your fingers this is the effect of your vocal cords at work, two folds of mucous tissue inside your larynx, that vibrate in order to produce voice . now, still keeping your fingers in place, whisper good morning you’ll notice that the vibration is gone, because whisper has no voice. your vocal cords do not vibrate when you whisper. when we produce speech sounds, the vocal cords can be in one of these two states:.

- Closed , i.e. loosely brought together so that they vibrate when air flows through them. It is this vibration that creates what we call voice, resulting in voiced sounds.

- Open , i.e. pulled apart during the production of certain sounds, as they are during normal breathing or in whisper, resulting in voiceless sounds.

With your fingers again in place on your larynx, say a long zzzz as in the beginning of the word zap and a long vvvv as in the beginning of the word vat , loud and clear. Next, say a long ssss ( sap ) and ffff ( fat ) sound. Did you notice that the first two sounds are voiced and the last two are voiceless? For a more dramatic contrast, say the same sounds with your hands over your ears, blocking them off. The two voiced sounds zzzz and vvvv produce a buzzing vibration, caused by voicing, inside your head, whereas the two voiceless sounds ssss and ffff produce a turbulent hiss of air.

Oral vs. nasal sounds, with the tip of your tongue, touch the roof of your mouth. you’ll feel a bony surface, called the hard palate . now drag the tip of your tongue back along the hard palate, as far back as it will go. you will notice that at the very back there is no bone: this is the soft palate, or velum ., now close your lips tightly, and hum. notice that you don’t need to use your jaw at all to make your voice heard. sounds that are produced as you hum involve using your nasal cavity: you produce them as air flows out through your nose. when we produce speech sounds, the soft palate can be in one of these two states:.

- Raised against the top part of your pharynx, which is the back wall of your throat. When raised, the soft palate blocks the airflow to the nasal cavities, resulting in oral sounds.

- Lowered , causing the air to flow through the nasal cavities, as when you hum, resulting in nasal sounds.

Say a long ah sound, as if calling for help by using the word Guard! Now, say the sound given in English spelling by – ng , as in the word bang . Repeat the sequence ah-ng-ah-ng-ah-ng-ah several times with no pauses in between, paying attention to what’s going on at the back of your mouth. You will feel the soft palate moving up and down, up for ah , which is an oral sound, and down for the nasal sound – ng . While doing this, pinch your nostrils together. You’ll have no problem producing the oral sound ah . But you’re no longer able to produce the nasal sound – ng , right? This is because when you pinch your nostrils together, air cannot flow out through your nose. To double-check that it is your soft palate moving, try saying ah-gah-gah-gah , where both sounds are oral. Pinch your nostrils together again, to confirm the difference between oral sounds like gah and nasal ones like ng . Assuming that you’ve had a bad cold at least once in your life, you’ll remember the strange resonance of your speech at the peak of it, when you have a blocked nose. Your listeners notice it, too. What happens is that air cannot flow out through your nasal cavities to produce the nasal sounds of speech. You may now realise that the popular expression “speaking through your nose” couldn’t be further from the facts: with a bad cold, you speak exclusively through your mouth.

Activity 4.2

Vowels vs. consonants

Generally, we can say that:.

- Consonants like t are produced by means of an obstruction to the airflow in the oral cavity. The lips, teeth and tongue form major consonantal obstructions.

- Vowels like ah are produced with no obstruction in the mouth: the shape of the vocal tract is modulated by different configurations of the tongue and lips.

Note that vowels and consonants refer to sounds, not letters/spellings. If you think there are five vowels in English, a, e, i, o, u , you will have reason to change your mind after you read the next chapter.

Activity 4.3

4.2.3 Consonants

We can produce different types of consonants, depending on two major factors. One is the degree of obstruction to the airflow, which gives us the manner of articulation of the consonant. The other is the location of the obstruction along the vocal tract, which tells us about the place of articulation of the consonant. These two factors operate independently of each other: in the same way that you can place obstacles of the same or different kinds just about anywhere along a cross-country obstacle course, you can have the same or different types of obstructions to the airflow in different places along your vocal tract.

Manner of articulation

- Plosives are pronounced with the velum raised, and involve contact of articulators. This means that the articulators first touch each other, and then separate.

- Non-plosive consonants, in contrast, involve close approximation of the articulators. This means that the articulators come very close to each other, without ever touching. One example is the class of fricative sounds, where the air is hissed (i.e. expelled with friction , hence their name) through a very narrow gap between the articulators.

Check that the t -like sound that you produced before is a plosive: the tongue tip touches the alveolar ridge, thereby closing off oral airflow. The sudden release of this closure produces an ex plosive effect.

Try now the long sounds ssss and vvvv again. The friction that you hear means that there can be no contact between articulators: there must be a narrow channel somewhere that allows the air to hiss through it. Note that you can prolong fricative sounds for as long as you have air in your lungs. This is not possible with plosives, whose articulation is instantaneous. To check, try prolonging a t sound – chances are that you will go red in the face for lack of air, because of the plosive closure that is needed to produce this sound.

Place of articulation

- (Bi)labials involve one or both lips in their articulation.

- Alveolars involve the alveolar ridge as articulator.

- Velars involve the soft palate/velum as articulator.

Now you know that t is not only plosive, it is also alveolar. You may also have guessed by now that the sounds spelt p and b are bilabials, involving both lips. Use your mirror (or your friends) to check these clearly visible articulations.

Say the sequence ah-ng-ah-ng-ah-ng-ah again, this time to check that the -ng sound involves contact between the back part of your tongue and the velum. So do the initial sounds in the words gap and cat. You can check this by saying ah-gah-gah-gah and ah-kah-kah-kah . All three sounds are therefore velar.

Now say vvvv and ffff , and concentrate on which articulators are involved in saying them. Use your mirror-friend to check. The upper lip plays no role in their articulation, but the lower lip does. These sounds are pronounced with the upper teeth very close to the lower lip. These sounds are therefore labial (and dental too: they involve the teeth, that your dentist checks out for you).

The place of articulation of sounds like ssss and zzzz is more difficult to check, because the whole of their articulation goes on inside the mouth. In terms of manner of articulation, both sounds are fricative. There is therefore no contact of articulators that may help us feel the place of articulation, in the absence of visual clues. But try this: say ssss and zzzz , then stop saying them but keep the articulators in exactly the same position, and breathe in quickly. You will feel a rush of cold air between the tip of your tongue and the alveolar ridge. This is the space inside your mouth that allows the articulation of the sounds ssss and zzzz , which shows that the constriction to the flow of air is located there. Both sounds are therefore alveolar.

4.2.4 Vowels

The articulation of different types of vowels depends on the movements of the tongue and lips. The body of the tongue can move vertically (up or down) and horizontally (front or back). The lips may be involved in the articulation of vowels, too.

The movements of the tongue body (the bulk of the tongue inside your mouth) are independent of one another. You can, for example, move your tongue up and down whilst bunching it up at the back of your mouth or, conversely, you can push it to the front or the back of your mouth while holding it high towards the hard palate. Try it.

Tongue-body movements are also independent of any movements of the tongue tip : the tongue tip is used in the production of consonants, not vowels. It may in fact come as surprise to you, especially if you are a body- builder, that the tongue is the best trained and most versatile muscle in your body. Its core role in speech is clear from the use of its name, “tongues”, to mean ‘languages’, in many languages around the world. We don’t notice the spectacular gymnastics show that goes on inside our mouths every time we speak because we have been practising this sophisticated skill since infancy. To get an idea of the range and power of tongue actions, remember it is used in chewing and swallowing, too. If you don’t believe us, try chewing on something while keeping your tongue motionless!

Vowel height

- High (or close ) vowels are produced with the body of the tongue raised.

- Low (or open ) vowels are produced with the body of the tongue lowered.

Open your mouth wide and say a long aaaah again. While still saying ah, slowly raise your jaw. Use your mirror to check that you are indeed raising your jaw. You’ll find that, whatever you’re saying now, it’s not ah anymore. The vowel ah, in a word like cart, must be pronounced with a lowered jaw, and therefore a lowered tongue: it is an open vowel.

Now say a long iiiih vowel, as in the word see, and drop your jaw while saying it. You won’t be able to say ih anymore The vowel ih needs a raised tongue to be produced: it is a close vowel. The difference between open and close vowels explains why your doctor asks you to say aaaah, and not iiiih, in order to be able to examine your throat.

Vowel backness

- Front vowels are produced with the body of the tongue pushed forward in the oral cavity.

- Back vowels are produced with the body of the tongue pulled back/retracted.

Say the vowel in the word cat , and then the vowel in the word cart , several times in a row. You’ll feel your tongue moving back and forth while doing this, back for the vowel in cart , and forwards for the vowel in cat . Use a mirror, to get visual feedback on this: it is easy to see because both these vowels are open.

Now try the same thing with the vowels in the words bean and boon . This is more difficult to feel because the boon vowel involves a distracting factor, which is the pouting, or rounding, of the lips. The difference in tongue movement is also impossible to see, because both vowels are close. So try this, instead. Take a pen, or a chopstick, and place it lengthways across your mouth, so that both ends of the pen/chopstick stick out from the sides of your mouth. Then bite it firmly as far back in your mouth as possible. Biting the pen/chopstick prevents the lips from moving in the articulation of the vowel in boon . Now say the vowels in bean and boon again. You’ll feel your tongue touching the pen in the articulation of the vowel in bean , but not of the vowel in boon . We thus conclude that the vowels in cat and bean are front vowels, whereas those in cart and boon are back vowels.

Lip rounding

- Rounded vowels are produced with rounded (pouting) lips.

- Unrounded vowels are produced with unrounded (spread) lips.

Easiest comes last. Of the four vowels that we’ve discussed, the vowel in boon is the only one that involves the lips: the lips must be rounded in its articulation. This is also why your photographer asks you to say cheeeese and not choooose when prompting a smile from you: spread-lip vowels are “smiley” sounds.

4.3 The transcription of speech sounds

A phonetic transcription is a way of representing sounds in print. The IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet) is a standard among phonetic alphabets , with symbols that correspond bi-uniquely to the sounds of the world’s languages. This means that, unlike spelling symbols, the same phonetic symbol always represents the same sound, and vice versa. In other words, unlike the relationship between speech sounds and spelling, there is a one-to- one correspondence between phonetic symbols and the sounds they represent. This is why trained phoneticians can read a phonetic transcription of any language and sound fluent in it, even if they have no idea how to speak (or spell!) the language.

Figure 4.1 below gives the set of phonetic symbols used in this book. In the token words included in the table, the letters that correspond to the sounds on the left are in bold italic font. When consulting phonetics literature, or dictionaries that include IPA transcriptions, you may notice that certain vowels are transcribed using an additional symbol [ː] following the vowel symbol. This indicates vowel length, and a corresponding distinction between long and short vowels present in some languages and some varieties of English, e.g. bean vs. bin , respectively. Many dictionaries also mark the stressed syllable of words. Intonation in turn has its own set of transcription symbols. For the purposes of this book, you do not need to be familiar with these conventions.

Figure 4.1. Phonetic symbols used in this book

Phonetic transcriptions are usually given in square brackets. For example, the transcription of the word cat is represented [kæt].

Activity 4.4

Practise transcribing these words, using the phonetic symbols introduced above. Remember to focus on how the words are pronounced, not on how they are spelt.

4.4 The analysis of speech sounds

According to the phonetics literature, there are two major ways of describing and labelling speech sounds:

- The IPA (International Phonetic Association) approach. Note that the abbreviation IPA stands for two different things – an alphabet and an association.

- The DF (Distinctive Feature) approach.

Both approaches draw on articulatory features of speech such as the ones that we have discussed in this chapter, and both therefore propose a universal framework for the description of human speech sounds. However, each approach takes a different perspective to look at speech sounds. This naturally results in alternative classifications of speech sounds, that do not always overlap across the two frameworks. As we’ve noted before, alternative analyses of this kind are as common in linguistics as in other sciences. They are part and parcel of our quest to understand, and they should be viewed as the probing tools that they are. It’s up to us, as users of these tools, to choose the one that we deem most useful to approach the object of our inquiry, or to come up with a more illuminating alternative.

There are two major differences between the IPA and DF frameworks.

- The IPA approach views vowels and consonants as fundamentally distinct types of sounds. The DF approach views all speech sounds as fundamentally similar.

- The IPA assumes a set of articulatory configurations whose combined presence in the articulation of a sound defines that sound. The DF approach assumes a set of articulatory configurations, each of which can be present [+] or absent [-] in the articulation of a sound, on a binary basis.

We now comment on each of these differences in turn. Because IPA analyses of speech sounds view vowels and consonants as radically different in terms of their articulation, they make a principled distinction between the classification of vowels and consonants. DF analyses don’t.

The IPA uses two distinct sets of articulatory configurations, one to characterise vowels and another to characterise consonants, each with their own set of terms. Consonants are described in terms of three articulatory configurations, namely, vocal cord vibration, place of articulation, and manner of articulation. Any consonant can be uniquely described using these three criteria. For example, [d] is a voiced alveolar plosive; [s] is a voiceless alveolar fricative. Vowels are described in terms of three other articulatory configurations, namely, lip rounding, tongue height, and tongue backness. So the vowel in bean , for example, can be uniquely described as unrounded close front, while that in boon is rounded close back.

In contrast, the DF framework uses the same set of criteria for all speech sounds. Each configuration of the vocal tract corresponds to an articulatory feature that allows us to distinguish one speech sound from another. These features are therefore distinctive . For example, raising the body of the tongue characterises the articulation of sounds like [i] and [k], as opposed to [ɑ] and [z]. A feature that allows us to distinguish between the first and the second set of sounds is therefore relevant for our characterisation of speech, and is called [high] (distinctive feature labels are usually represented in square brackets). Or, vocal cord vibration, labelled [voice], allows us to distinguish [i, α, z] from [k]. Or, the smoothness of the airflow through the vocal tract distinguishes [i, ɑ] from [z, k], and is represented in a feature called [sonorant].

The second difference between IPA and DF analyses concerns the way each of them views the articulatory make-up of a speech sound. For the IPA, a sound consists of a pool of articulations that, together, produce that sound. For example, [d] is voiced, and alveolar, and plosive, and [i] is unrounded, and close, and front. To use an analogy, a girl would likewise be characterised by the pool of properties human, and female, and child. The presence of these features makes a sound (or a girl) unique. In DF approaches, a distinct sound depends on whether specific features of articulation are activated or not in its production. For example, [i] is [+sonorant] and [z] is [-sonorant], [d] is [+voice] and [t] is [-voice]. A girl could be described as [+human -male -adult]. The interplay of features, activated as well as inactivated, is unique to the sound.

Given the introductory nature of this book, we will not go into theoretical detail relating to the two frameworks. However, you will come across published material on phonetic analysis that often makes free use of terminology from either approach, and often in the same research piece. The set of tables that we propose below will, we hope, facilitate your learning about phonetics.

We start with the IPA, because this was the first analytical framework available to phoneticians. The IPA was founded in 1886, and the first DF proposals appeared in the early 1950s. Throughout the discussion in the remainder of this chapter, you should keep in mind that the use of the International Phonetic Alphabet in transcriptions does not imply subscription to the classificatory approach of the International Phonetic Association. DF analyses may use IPA phonetic symbols. A set of printable symbols and a theoretical stance about the classification of the sounds that these symbols represent are two different things.

IPA representations of speech sounds

Below are two samples of IPA charts, one for consonants and one for vowels.

Figure 4.2. Partial IPA consonant chart

By IPA convention, in paired voiced vs. voiceless sounds, the voiceless sound appears to the left of its voiced counterpart. Note that the blank box in the chart simply indicates that we do not deal with velar fricative articulations in this book. Many languages and language varieties have velar fricatives, like German, e.g. at the end of the word Bach , or Scottish English, e.g. at the end of the word loch (a word for ‘lake’, as in Loch Ness ).

Different IPA labels referring to place of articulation can be combined to provide more detailed articulatory descriptions. For example, the sounds [f, v] are usually described as l abio-dental fricatives, accounting for the fact that their pronunciation involves both the lips and the teeth.

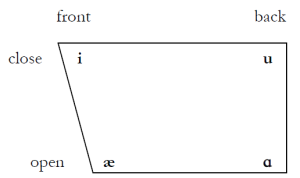

Vowel space is usually plotted inside a diagram like the one in Figure 4.3, called a vowel quadrilateral .

The diagram represents the left profile of the inside of the mouth, the side that is also represented in standard diagrams of the vocal tract. Each of the four sides in the diagram represents the top, bottom, front and back of the oral cavity. The four vowels discussed in this chapter can be plotted at the four angles of the quadrilateral. The vowel quadrilateral accounts for tongue movement only. It does not represent lip movement.

DF representations of speech sounds

Here is a summary of a sample of distinctive features.

Figure 4.4. Sample DF labels

DF approaches typically use a matrix-like table to classify speech sounds, where vowels and consonants are plotted together.

The matrix in Figure 4.5 gives a classification of the speech sounds that are represented by the phonetic symbols in its first column. For example, the four vowel symbols [i, æ, !, u] represent oral vowels, and the feature [nasal] is accordingly marked for these vowels with a minus symbol. Many languages have nasalised vowels (e.g. French, Portuguese, Hokkien), for which there are different phonetic symbols from the ones given here, and whose [nasal] feature is therefore marked with a plus sign in a DF matrix. We marked the consonants [t, d, n] as [-dental] in the matrix, although they can be [+dental] in several languages and in several varieties of English. When you articulate [t, d, n] as [+dental], the tip of your tongue touches your upper teeth instead of the alveolar ridge. In all cases, [t, d, n] are [+coronal].

In the matrix below, we use the following conventions:

son : sonorant lab : labial dent : dental cor : coronal

Figure 4.5. Sample DF matrix

It’s worth highlighting that in both frameworks, IPA and DF, the different configurations of the articulators are independent of one another. For example, within the IPA framework, a plosive can be voiced or voiceless, labial, alveolar or velar. Similarly, within the DF framework, a [+high] sound can be [+front] or [+back], [+labial] or [-labial]. The important thing to keep in mind is that each movement of each articulator produces one particular effect on the flow of air. It is the combination of concerted effects that produces a speech sound.

Activity 4.5

Redundancy in phonetic descriptions

Our realisation that a sound is the result of a complex interplay of factors does not mean that its description must reflect this complexity. If description consistently matched real-world complexity, nobody would be able to learn about Newton’s Laws of Motion in secondary school. Science of course strives to make sense of complex phenomena by means of simple descriptive statements. Let’s illustrate this point with an example. From the DF matrix in Figure 4.5, we may conclude that the English sound represented by the symbol [n] can be described as:

(4.2) [+son +stop +nasal -high -low -front -back -lab -dent +cor +voice]

This description is accurate because it accounts for the uniqueness of [n] among all other sounds. But it is also, to say the least, cumbersome. It is like describing a cat, as opposed to a human being, as having fur, two eyes, four limbs, mammal features, claws, a stomach, whiskers, feline features and small size. Some of these properties can be inferred from other properties. For example, “four limbs” can be predicted from “mammal features”. Other properties apply equally well to other members of a larger class. For example, both cats and humans have two eyes and a stomach. Likewise, in terms of distinctive features, [+nasal] implies [+sonorant], because nasal airflow is smooth (unless you’re blowing your nose!). Also, most sounds in Figure 5.5 share features like [-low -front]. An equally adequate description of the sound [n], in terms of distinctive features that apply to English is:

(4.3) [+nasal +cor]

This is so because, in English, there are only three nasal sounds, [m, n, η]. Specifying their place of articulation is thus enough to describe the uniqueness of each nasal in this language. The description in (4.3) is as informative as the one in (4.2), and it is clearly simpler. We should stress, however, that (4.3) provides a description of [n] that applies to a single language, in this case English. In other languages, the set of nasal sounds may include vowels, as we noted above, or other consonants besides [+stop], or [+stop] nasals that are [+coronal] and [+dental]. The analysis of sounds in different languages must of course take into account the specific articulatory patterns that are found in each language.

Our discussion of the description in (4.2) highlights two important points. The first is that a DF analysis provides us with more labels than are necessary for the description of single sounds in particular languages. This is also true of the IPA approach. We saw that the combination of velar and fricative articulations does not exist in English, although velar and fricative are useful labels to describe other articulatory combinations in this language. In other words, both IPA and DF frameworks contain some degree of redundancy, in that they specify more structure than is required for the actual description of any given speech sound. A complete IPA and DF chart of the full set of articulations involved in English, for example, would show greater redundancy still. We will see another example of redundant analysis in section 6.3.1, where a theoretical “slot” was posited for inflectional prefixes, a unit that is not needed for the analysis of English morphemes, but which occurs in other languages. Redundancy is a feature of any scientific analysis, and of taxonomies in particular. For example in zoology, mammal and eight legs are constructs that usefully describe different types of living organisms, although there are no eight-legged mammals. Redundancy is also a feature of language itself, in fact an invaluable one in everyday communication.

The second point that we wish to note is that redundancy operates at two different levels, the level of individual languages and the level of language in general. We saw above that (4.3) removes the redundancies found in (4.2) for the description of one sound in one language. We said that one of the reasons why we were able to simplify (4.2) is that some features are predictable from other features. In English, [+nasal] predicts [+stop], because all English nasals involve a complete closure in the mouth, blocking the airflow. But we also said that [+nasal] implies [+sonorant], because nasal airflow is smooth, and this is a universal entailment. It applies to nasal sounds in any language. An articulation like *[+nasal -sonorant] is therefore not generally found: we already know that not all theoretically possible articulations occur in practice. This is often due to simple physical reasons, that apply to any human being and therefore to any language. For example, try producing a speech sound which involves contact between your soft palate and your lower lip!

Activity 4.6

- Which of the following (sets of) features necessarily implies the other? Circle your answers. The symbol ⇒ stands for ‘implies’.

2. Which of the following combinations are impossible to articulate? Circle your answers.

Activity 4.7

The clear differences, that we have highlighted, between IPA and DF analyses should not obscure the fact that their object is the same: the articulation of human speech sounds. For example, the same sound [p] can be identified as a voiceless bilabial plosive or as [-son +stop -voice +lab]. These descriptions do not reflect a difference in the articulation of the sound [p]. They reflect a preference for a set of labels and representations that each framework, or theory, finds more useful for the purposes of their investigation.

Despite the different assumptions and insights into articulation that each of the two framework offers, the phonetics literature does not always show a clear-cut choice between one or the other. As we noted at the beginning of this section, phoneticians may draw on terminology from either account, when describing their research. This is often so for the sake of simplicity. For example, it is quicker (and neater) to say plosive than to say [-son +stop]. But it is also simpler to say [+sonorant] than to say vowels and nasals . This terminological hesitation reflects the fact that in phonetics, as in any science, the search continues, for the most economical way of making sense of our observations.

Activity 4.8

4.5 Intonation and tone

Vowels are voiced sounds, produced with a smooth airflow. These two features make vowels the sounds upon which intonation is chiefly modulated.

Intonational modulation, or speech melody, is one crucial carrier of linguistic meaning in any language.

Imagine yourself in two different situations where you might use the following utterance, one jokingly, one deeply annoyed:

Oh, shut up!

If you try to pronounce this utterance to match the suggested feelings, you’ll find that you pronounce the “same” utterance in two very different ways. In fact, you’ll be pronouncing two different utterances, with two distinct meanings.

Intonation can be said to result from rapid changes in the tension and rate of vibration of the vocal cords. The vocal cords are folds of elastic tissue that can stretch or contract, and vibrate at a higher or lower rate, much like violin strings. Associated with these changes, the length of the vocal tract may be modified during speech, due to the vertical mobility of the larynx.

Touch your larynx gently with your fingers, or look in a mirror with your chin lifted up, so you can see your larynx clearly. Now sing the highest note you can sing, and then the lowest, and then go from one to the other, a few times in a row. You’ll feel/see your larynx moving up for the high note, and down for the low one, assisting the higher and lower rate of vibration of the vocal folds, respectively. The effect that these combined actions have on the column of air inside your vocal tract gives a similar impression to the one achieved by a “bottle concert”, where you fill similar bottles with different amounts of liquid and then either blow into them or strike them with some hard instrument. You’ll get a higher note when there’s a higher rate of vibration inside the bottle and inside your vocal tract, and lower notes for lower rates.

Like any other linguistic system, intonation systems vary both across and within languages. However, two basic distinctions in the form of intonation patterns appear to be consistently associated with two sets of meanings, according to whether our tone of voice falls or rises.

Falling tones

Falling tones , or falls , result from a decrease in the rate of vibration of the vocal cords. Falls are typically associated with statements and commands. These types of utterances require minimal or no verbal response from the listener, and falling tones are therefore said to convey a closed set of meanings, in that they close off communication.

Rising tones

Rising tones , or rises , result from an increase in the rate of vibration of the vocal cords. Rises typically signal questions, which call for some response from the listener, and continuation, when the speaker goes on speaking. That is, the use of rising tones in an utterance indicates that the utterance is not complete, and rises are therefore associated with an open set of meanings.

Activity 4.9

If you have difficulty producing (and hearing) falling vs. rising tones, or level tones, try Collins and Mees’ (2003: 118) analogy: “The engine of a motor car when ‘revving up’ to start produces a series of rising pitches. When the car is cruising on the open road, the engine pitch is more or less level . On coming to a halt, the engine stops with a rapid fall in pitch.”

Intonational modulation operates across whole utterances, including those that may comprise a single word. In many languages, the difference between a statement and a question is signalled by intonation alone, a fall vs. a rise at the end of the utterance, respectively, without the associated change in word order that is common in standard uses of English.

All languages make intonational distinctions of this kind, but there are other uses of pitch in language. Pitch modulation may operate on single words, distinguishing between different lexical meanings of the same string of vowels and consonants. This is the domain of tone . Here is one example from Ngbaka, spoken in the Central African Republic. This language has level tones, meaning that the tone is kept even, neither rising nor falling, throughout the pronunciation of the words:

Figure 4.6. Examples of tones in Ngbaka

Asian languages like Mandarin, African languages like Hausa, and several American Indian languages are tone languages , distinct from intonation languages like English or Malay. Other languages, like Swedish and Japanese, combine features of intonation and tone languages.

As a concluding thought, it is interesting to note that despite the crucial role played by pitch modulation across all languages, the meanings conveyed by such modulation are hardly represented in spelling. Question marks vs. exclamation marks, for example, give an even rougher approximation to the various rises and falls of real-life language than the English spellings bu s , cre ss , sc ien ce , c ity, mou se , fla cc id, give to the sound [s]. The deficient representation of intonation in print highlights the very limited resources of written forms of language to convey the full range of linguistic meanings. It is often the case that the meaning that you intend for an utterance is in fact given by intonation, rather than by the words that you use. We’ve all heard the saying: it’s not what you say but how you say it that counts. Or, as the American linguist Kenneth Pike (1945: 22) strikingly put it, “[…] if a man’s tone of voice belies his words, we immediately assume that the intonation more faithfully reflects his true linguistic intentions.”

Activity 4.10

Activity 4.11

In this chapter, we have provided a very brief overview of the range and variety of speech sounds that can be produced by the human vocal tract. Obviously, no language makes use of all possible speech sounds. In the next chapter, we look at how speech sounds are organised and used in languages.

Food for thought

When it’s English that we SPEAK

Why is STEAK not rhymed with WEAK? And couldn’t you please tell me HOW COW and NOW can rhyme with BOUGH?

I simply can’t imagine WHY HIGH and EYE sound like BUY.

We have FOOD and BLOOD and WOOD, And yet we rhyme SHOULD and GOOD.

BEAD is different from HEAD,

But we say RED, BREAD, and SAID. GONE will never rhyme with ONE

Nor HOME and DOME with SOME and COME.

NOSE and LOSE look much alike,

So why not FIGHT, and HEIGHT, and BITE?

DOVE and DOVE look quite the same,

But not at all like RAIN, REIN, and REIGN.

SHOE just doesn’t sound like TOE, And all for reasons I don’t KNOW. For all these words just prove to ME That sounds and letters DISAGREE.

Further reading

Collins, Beverley and Mees, Inger M. (2003). How we produce speech. In practical phonetics and phonology: A resource book for students . London/New York: Routledge, pp. 25-39.

(This book includes a CD with sound files to listen to and practise with.) Deterding, David H. and Poedjosoedarmo, Gloria R. (1998). Chapter 2.

Speech production. In The sounds of English. Phonetics and phonology for

English teachers in Southeast Asia . Singapore: Prentice Hall, pp. 9-13.

Roach, Peter (1993). Chapter 2. The production of speech sounds. In English phonetics and phonology. A practical course . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 8-17.

Collins, Beverley and Mees, Inger M. (2003). How we produce speech. In practical phonetics and phonology: A resource book for students . London/New York: Routledge.

Pike, Kenneth L. (1945). The intonation of American English . Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Attribution

This chapter has been modified and adapted from The Language of Language. A Linguistics Course for Starters under a CC BY 4.0 license. All modifications are those of Régine Pellicer and are not reflective of the original authors.

ENG 3360 - Introduction to Language Studies Copyright © 2022 by Régine Pellicer is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

The 44 Sounds in the English Language

Tahreer Photography/Getty Images

- Reading & Writing

- Applied Behavior Analysis

- Behavior Management

- Lesson Plans

- Math Strategies

- Social Skills

- Inclusion Strategies

- Individual Education Plans

- Becoming A Teacher

- Assessments & Tests

- Elementary Education

- Secondary Education

- Homeschooling

When supporting children in learning the sounds of the English language, remember to choose words that demonstrate all 44 word-sounds or phonemes . English contains 19 vowel sounds —5 short vowels, 6 long vowels, 3 diphthongs, 2 'oo' sounds, and 3 r-controlled vowel sounds—and 25 consonant sounds.

The following lists provide sample words to use when teaching the sounds of the English language. You may choose to find more words to fill out word families or align with sight vocabulary lists such as a Dolch Word List . Your learners will benefit most from terms that are familiar to them or make sense in their life.

The 5 Short Vowel Sounds

The five short vowel sounds in English are a, e, i, o, and u.

- short a: and, as, and after

- short e: pen, hen, and lend

- short i: it and in

- short o: top and hop

- short u: under and cup

Remember that these sounds are not necessarily indicative of spelling. Note that the above words all contain the vowel whose sound they make but this is not always the case. A word might sound as if it contains a certain vowel that is not there. Examples of words whose short vowel sounds do not correspond with their spelling are b u sy and d o es.

The 6 Long Vowel Sounds

The six long vowel sounds in English are a, e, i, o, u, and oo .

- long a: make and take

- long e: beet and feet

- long i: tie and lie

- long o: coat and toe

- long u (pronounced "yoo"): music and cute

- long oo: goo and droop

Examples of words whose long vowel sounds do not correspond with their spelling are th e y, tr y, fr u it, and f e w .

The R-Controlled Vowel Sounds

An r-controlled vowel is a vowel whose sound is influenced by the r that comes before it. The three r-controlled vowel sounds are ar, er, and or.

- ar: bark and dark

- er: her, bird, and fur

- or: fork, pork, and stork

It is important that students pay close attention to the er sound in words because it can be created by an r-controlled e , i, or u . These vowels are all transformed into the same sound when an r is attached to the end of them. More examples of this include bett er , f ir st, and t ur n .

The 18 Consonant Sounds

The letters c, q , and x are not denoted by unique phonemes because they are found in other sounds. The c sound is covered by k sounds in words like c rust, c runch, and c reate and by s sounds in words like c ereal, c ity, and c ent (the c is found in the spelling of these words only but does not have its own phoneme). The q sound is found in kw words like bac kw ard and Kw anza. The x sound is found in ks words like kic ks .

- b: bed and bad

- k: cat and kick

- d: dog and dip

- f: fat and fig

- g: got and girl

- h: has and him

- j: job and joke

- l: lid and love

- m: mop and math

- n: not and nice

- p: pan and play

- r: ran and rake

- s: sit and smile

- t: to and take

- v: van and vine

- w: water and went

- y: yellow and yawn

- z: zipper and zap

Blends are formed when two or three letters combine to create a distinct consonant-sound, often at the beginning of a word. In a blend, the sounds from each original letter are still heard, they are just blended quickly and smoothly together. The following are common examples of blends.

- bl: blue and blow

- cl: clap and close

- fl: fly and flip

- gl: glue and glove

- pl: play and please

- br: brown and break

- cr: cry and crust

- dr: dry and drag

- fr: fry and freeze

- gr: great and ground

- pr: prize and prank

- tr: tree and try

- sk: skate and sky

- sl: slip and slap

- sp: spot and speed

- st: street and stop

- sw: sweet and sweater

- spr: spray and spring

- str: stripe and strap

The 7 Digraph Sounds

A digraph is formed when two consonants come together to create an entirely new sound that is distinctly different from the sounds of the letters independently. These can be found anywhere in a word but most often the beginning or end. Some examples of common digraphs are listed below.

- ch: chin and ouch

- sh: ship and push

Point out to your students that there are two sounds that th can make and be sure to provide plenty of examples.

Diphthongs and Other Special Sounds

A diphthong is essentially a digraph with vowels—it is formed when two vowels come together to create a new sound in a single syllable as the sound of the first vowel glides into the second. These are usually found in the middle of a word. See the list below for examples.

- oi: oil and toy

- ow: owl and ouch

Other special sounds include:

- short oo : took and pull

- aw: raw and haul

- R-Controlled Vowel Words for Word Study

- Do You Know Everything About Consonant Sounds and Letters in English?

- Short and Long Vowel Lesson Plan

- How To Pronounce Vowels in Spanish

- Vowel Sounds and Letters in English

- Long and Short Vowel Sounds

- Voiced vs. Voiceless Consonants

- How to Teach Digraphs for Reading and Spelling Success

- How to Pronounce Vowels in Italian

- Basic Grammar: What Is a Diphthong?

- Spanish Pronunciation

- German for Beginners: Pronunciation and Alphabet

- Understanding English Pronunciation Concepts

- Definition and Examples of Digraphs in English

- Articles in Grammar: From "A" to "The" With "An" and "Some" Between

- When to Change ‘Y’ to ‘E’ and ‘O’ to ‘U’ in Spanish

The 44 sounds in English with examples

Do you want to learn more about American English sounds? You’ve come to the right place. In this guide, we discuss everything you need to know, starting with the basics.

Definition of Phonemes

- English Keywords

Phonics: The way sounds are spelled

English consonant letters and their sounds.

- Bringing it all together

The vowel chart shows the keyword, or quick reference word, for each English vowel sound. Keywords are used because vowel sounds are easier to hear within a word than when they are spoken in isolation. Memorizing keywords allows easier comparison between different vowel sounds.

Phonemic awareness is the best predictor of future reading ability Word origins. The English word dates back to the late 19th century and was borrowed from two many sources. The 44 English sounds fall into two categories: consonants and vowels.

Below is a list of english phonemes and their International Phonetic Alphabet symbols and some examples of their use. Note that there is no such thing as a definitive list of phonemes because of accents, dialects, and the evolution of language itself. Therefore you may discover lists with more or less than these 44 sounds.

A consonant letter usually represents one consonant sound. Some consonant letters, for example, c, g, s, can represent two different consonant sounds.

English vowel letters and their sounds

A vowel is a particular kind of speech sound made by changing the shape of the upper vocal tract, or the area in the mouth above the tongue. In English it is important to know that there is a difference between a vowel sound and a [letter] in the [alphabet]. In English there are five vowel letters in the alphabet.

Do you find it difficult to pronounce English words correctly or to comprehend the phonetic alphabet's symbols?

The collection of English pronunciation tools of the EnglishPhonetics below is for anyone learning the language who want to practice their pronunciation at any time or place.

(FREE) English Accent Speaking test with Voice and Video

Take a Pronunciation Test | Fluent American Accent Training

The best interactive tool to the IPA chart sounds

Listen to all International Phonetics Alphabet sounds, learn its subtle differences

American English IPA chart

Listen the American english sounds with the interactive phonics panel

Free English voice accent and pronunciation test

Get a score that informs your speaking skills

To Phonetics Transcription (IPA) and American Pronunciation voice

Online converter of English text to IPA phonetic transcription

Contrasting Sounds or Minimal Pairs Examples

Minimal pairs are an outstanding resource for english learning, linguist and for speech therapy

English pronunciation checker online

To check your pronunciation. Press the 'Record' button and say the phrase (a text box and 'Record' button). After you have spelled the word correctly, a 'speaking test' for the word will appear.

The [MOST] complete Glossary of Linguistic Terms

The meaning of " linguistics " is the science of studying the structure, transition, lineage, distribution, and interrelationships of human language.

Vowel sounds and syllable stress

Vowel sounds and syllables are closely related. Syllables are naturally occurring units of sound that create the rhythm of spoken English. Words with multiple syllables always have one syllable that is stressed (given extra emphasis).

Unstressed syllables may contain schwa /ə/, and can have almost any spelling. In addition, three consonant sounds, the n sound, l sound, and r sound (called 'schwa+r' /ɚ/ when it is syllabic) can create a syllable without an additional vowel sound. These are called syllabic consonants.

Ready to improve your english accent?

Get a FREE, actionable assessment of your english accent. Start improving your clarity when speaking

** You will receive an e-mail to unlock your access to the FREE assessment test

Eriberto Do Nascimento

Eriberto Do Nascimento has Ph.D. in Speech Intelligibility and Artificial Intelligence and is the founder of English Phonetics Academy

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

2.2 Articulators

Check Yourself

Video script.

We know that humans produce speech by bringing air from the lungs through the larynx, where the vocal folds might or might not vibrate. That airflow is then shaped by the articulators .

This image is called a sagittal section. It depicts the inside of your head as if we sliced right between your eyes and down the middle of your nose and mouth. This angle gives us a good view of the parts of the vocal tract that are involved in filtering airflow to produce speech sounds.

Let’s start at the front of your mouth, with your lips . If you make the sound “aaaaa” then round your lips, the sound of the vowel changes. We can also use our lips to block the flow of air completely, like in the consonants [b] and [p].

We also use our teeth to shape airflow. They don’t do much on their own, but we can place the tip of the tongue between the teeth, for sounds like [θ] and [ð]. Or we can bring the top teeth down against the bottom lip for [f] and [v].

If you put your finger in your mouth and tap the roof of your mouth, you’ll find that it’s bony. That is the hard palate . English doesn’t have very many palatal sounds, but we do raise the tongue towards the palate for the glide [j].

Now from where you have your finger on the roof of your mouth, slide it forward towards your top teeth. Before you get to the teeth, you’ll find a ridge, which is called the alveolar ridge . If you use the tip of the tongue to block airflow at the alveolar ridge, you get the sounds [t] and [d]. We also produce [l] and [n] at the alveolar ridge, and some people also produce the sounds [s] and [z] with the tongue at the alveolar ridge (though there are other ways of making the [s] sound.)

When we block airflow in the mouth but allow air to circulate through the nasal cavity , we get the nasal sounds [m] [n] and [ŋ].

Some languages also have nasal vowels. Make an “aaaaa” vowel again, then make it nasal. [aaaaa] [ããããã]