- Welcome to Eastman

- Mission and Vision

- Eastman Strategic Plan

- Community Engagement

- Awards and Recognition

- Equity and Inclusion

- Offices & Services

- Undergraduate

- Contact Admissions

- Faculty Listing

- Faculty Resources

- Chamber Music

- Composition

- Conducting & Ensembles

- Jazz Studies & Contemporary Media

- Music Teaching and Learning

- Music Theory

- Organ, Sacred Music & Historical Keyboards

- Strings, Harp, & Guitar

- Voice, Opera & Vocal Coaching

- Woodwinds, Brass & Percussion

- Beal Institute

- Early Music

- Piano Accompanying

- Degrees and Certificates

- Graduate Studies

- Undergraduate Studies

- Academic Affairs

- Eastman Community Music School

- Eastman Performing Arts Medicine

- George Walker Center for Equity and Inclusion in Music

- Institute for Music Leadership

- Sibley Music Library

- Summer@Eastman

- Residential Life

- Student Activities

- Concert Office

- Events Calendar

- Eastman Theatre Box Office

- Performance Halls

- Research and Recent Dissertations

About Eastman Research

The Eastman theory faculty pursues a broad range of research interests, including Schenkerian theory, studies in the theory and analysis of 20th-century music, history of music theory, musical perception and cognition, computing and music, and jazz and other popular music. An annual lecture series serves to expand research horizons still further. Guest lecturers have included David Huron, Philip Ewell, Joseph Straus, Mark Spicer, Ellie Hisama, Robert Hatten, Jocelyn Neal, Daniel Harrison, Yayoi Uno Everett, Michael Klein, Danny Jenkins, and John Roeder. Student-organized theory symposia provide opportunities for students to present papers and share research in progress. Graduate students present their work at regional and national conferences, as active contributors to the discipline. They also edit and publish, with the assistance of an editorial board of prominent music theorists, a juried music theory journal entitled Intégral .

Technological support for theoretical research is provided by the Music Research and Music Cognition Lab, which gives students the chance to learn and develop software for in-house and Internet use. The lab includes computers, seminar space, and a sound-proof booth for running music-cognitive experiments. Vital support for theory scholarship also is provided by the Sibley Music Library , which houses an extraordinary collection of historical treatises on music theory, manuscript letters, and first editions, and maintains active subscriptions to more than 650 periodicals.

Music Theory graduates join distinguished alumni from Eastman’s other PhD-granting disciplines—Musicology, Composition, and Music Education—many of whom are teaching and leading at musical institutions and schools around the world. This list offers a sample, rotating list of 50 PhD alumni from the past 30 years who are helping to shape the field of music through their work in a wide variety of colleges, universities, music schools, and other institutions.

Student Research Assistance Fund (SRAF)

Due to generous faculty and alumni donations to a new fund in support of student research, applications are invited from music theory students for grants to support specific research projects. Grants will typically be made in amounts of $300 or less.

Awards will be made by a committee consisting of the chair of music theory, plus one tenured and one untenured member of the theory department, each of whom serves for not less than one academic year.

Applications must be for an individual expenditure that is essential to the development or completion of a music theory research project. Examples include cost of specialized software for research, travel to present research at a conference, preparing music examples for a publication, or visiting an archive overseas, etc.

Students are expected to utilize funding sources already available to them (e.g., Professional Development Funds) prior to applying for SRAF funding.

E-mail Department Chair for more information on how to apply.

Recent Dissertations

Quick links.

- Theory Main

- Audition Repertoire

- Bachelor of Music in Theory

- Graduate Pedagogy

- Current Students

- Music Cognition

- Theory Colloquium

- Photo Highlights

- Departments Main

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 12 February 2019

Cultural evolution of music

- Patrick E. Savage ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6996-7496 1

Palgrave Communications volume 5 , Article number: 16 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

65k Accesses

34 Citations

49 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Cultural and media studies

- Social anthropology

The concept of cultural evolution was fundamental to the foundation of academic musicology and the subfield of comparative musicology, but largely disappeared from discussion after World War II despite a recent resurgence of interest in cultural evolution in other fields. I draw on recent advances in the scientific understanding of cultural evolution to clarify persistent misconceptions about the roles of genes and progress in musical evolution, and review literature relevant to musical evolution ranging from macroevolution of global song-style to microevolution of tune families. I also address criticisms regarding issues of musical agency, meaning, and reductionism, and highlight potential applications including music education and copyright. While cultural evolution will never explain all aspects of music, it offers a useful theoretical framework for understanding diversity and change in the world’s music.

Similar content being viewed by others

Global musical diversity is largely independent of linguistic and genetic histories

Cultural macroevolution of musical instruments in South America

The pace of modern culture

Introduction.

The concept of evolution played a central role during the formation of academic musicology in the late nineteenth century (Adler, 1885 / 1981 ; Rehding, 2000 ). During the twentieth century, theoretical and political implications of evolution were heavily debated, leading evolution to go out of favor in musicology and cultural anthropology (Carneiro, 2003 ). In the twenty first century, refined concepts of biological evolution were reintroduced to musicology through the work of psychologists of music to the extent that the biological evolution of the capacity to make and experience music ("evolution of musicality") has returned as an important topic of contemporary musicological research (Wallin et al., 2000 ; Huron, 2006 ; Patel, 2008 ; Lawson, 2012 ; Tomlinson, 2013 , 2015 ; Honing, 2018 ). Yet the concept of cultural evolution of music itself ("musical evolution") remains largely undeveloped by musicologists, despite an explosion of recent research on cultural evolution in related fields such as linguistics. This absence has been especially prominent in ethnomusicology, but is also observable in historical musicology and other subfields of musicology Footnote 1 .

One major exception was the two-volume special edition of The World of Music devoted to critical analysis of Victor Grauer's ( 2006 ) essay entitled "Echoes of Our Forgotten Ancestors" (later expanded into book form in Grauer, 2011 ). Grauer proposed that the evolution and global dispersal of human song-style parallels the evolution and dispersal of anatomically modern humans out of Africa, and that certain groups of contemporary African hunter-gatherers retain the ancestral singing style shared by all humans tens of thousands of years ago. The two evolutionary biologists contributing to this publication found the concept of musical evolution self-evident enough that they simply opened their contribution by stating: "Songs, like genes and languages, evolve" (Leroi and Swire, 2006 , p. 43). However, the musicologists displayed concern and some confusion over the concept of cultural evolution.

My goal in this article is to clarify some of these issues in terms of the definitions, assumptions, and implications involved in studying the cultural evolution of music to show how cultural evolutionary theory can benefit musicology in a variety of ways. I will begin with a brief overview of cultural evolution in general, move to cultural evolution of music in particular, and then end by addressing some potential applications and criticisms. Because this article is aimed both at musicologists with limited knowledge of cultural evolution and at cultural evolutionists with limited knowledge of music, I have included some discussion that may seem obvious to some readers but not others.

What is “evolution”?

Although the term “evolution” is often assumed to refer to directional progress and/or to require a genetic basis, neither genes nor progress are included in some contemporary general definitions of evolution. Furthermore, while it is true that the discovery of genes and the precise molecular mechanisms by which they change revolutionized evolutionary biology, Darwin formulated his theory of evolution without the concept of genes.

Instead of genes, Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection contained three key requirements: (1) there must be variation among individuals; (2) variation must be inherited via intergenerational transmission; (3) certain variants must be more likely to be inherited than others due to competitive selection (Darwin, 1859 ). These principles apply equally to biological and cultural evolution (Mesoudi, 2011 ).

Evolution did often come to be defined in purely genetic terms during the twentieth century. However, recent advances in our understanding of areas such as cultural evolution, epigenetics, and ecology (Bonduriansky and Day, 2018 ) have led to new inclusive definitions of evolution such as:

'the process by which the frequencies of variants in a population change over time', where the word ‘variants’ replaces the word ‘genes’ in order to include any inherited information….In particular, this…should include cultural inheritance. (Danchin et al., 2011 , p. 483–484)

While there remains some debate about how central a role genes should play in evolutionary theory (Laland et al., 2014 ), few scientists today would insist that the term evolution applies only to genes. Note also that there is nothing about progress or direction contained in the above definition: evolution simply refers to changes in the frequencies of heritable variants. These changes can be in the direction of simple to complex—and it is possible that there may be a general trend towards complexity (McShea and Brandon, 2010 ; Currie and Mace, 2011 )—but the reverse is also possible (Allen et al., 2018 ), as are non-directional changes with little or no functional consequences (Nei et al., 2010 ).

Does culture “evolve”?

From the time Darwin ( 1859 ) first proposed that his theory of evolution explained “The Origin of Species”, scholars immediately tried to apply it to explain the origin of culture. Indeed, Darwin himself explicitly argued that language and species evolution were "curiously parallel…the survival or preservation of certain favored words in the struggle for existence is natural selection" (Darwin, 1871 , p. 89–90). Scholars of cultural evolution have tabulated a number of such “curious parallels”, to which I have added musical examples (Table 1 ).

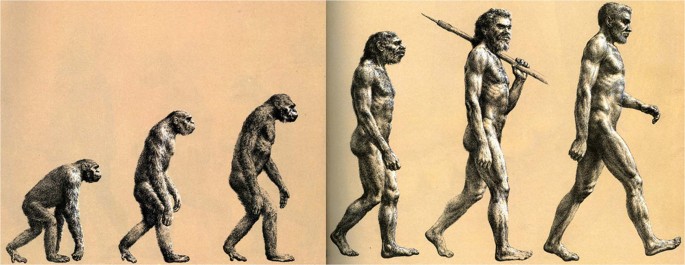

Theories about cultural evolution quickly adopted assumptions about progress (e.g., Spencer, 1875 ) linked with attempts to legitimize ideologies of Western superiority and justify the oppression of the weak by the powerful as survival of the fittest (Hofstadter, 1955 ; Laland and Brown, 2011 ; Stocking, 1982 ) Footnote 2 . It is no accident that Zallinger's iconic “March of Progress” illustration (Fig. 1 ) showed a gradual lightening of the skin from dark-skinned, ape-like ancestors to light-skinned humans: evolution was used to justify scientific racism by eugenicists (Gould, 1989 ). Although both the lightening of skin and the linear progression from ape to man are inaccurate (Gould, 1989 ), this image unfortunately remains extremely enduring and is commonly adapted to represent all kinds of evolution, including musical evolution (e.g., http://www.mandolincafe.com/archives/spoof.html ).

The classic example of an inaccurate but widespread representation of evolution as a linear “march of progress” (from Howell, 1965 )

Ideas of linear progress through a series of fixed stages continued to dominate cultural evolution for over a century (see Carneiro, 2003 for an in-depth review). It was not until late in the 20th century that several teams of scholars including Charles Lumsden and Edward O. Wilson ( 1981 ), L. Luca Cavalli-Sforza and Marcus Feldman ( 1981 ), and Robert Boyd and Peter Richerson ( 1985 ) began making attempts to model and measure changing frequencies of cultural variants (aka “memes”; Dawkins, 1976 ), as scientists such as Sewall Wright and Ronald Fisher had done for gene frequencies since the 1930s.

The theoretical and empirical work of cultural evolutionary scholars that emerged from this tradition has been crucial in demonstrating that evolution occurs "Not by Genes Alone" (Richerson and Boyd, 2005 ). Scholars have applied theory and methods from evolutionary biology to help understand complex cultural evolutionary processes in a variety of domains including languages, folklore, archeology, religion, social structure, and politics (Mesoudi, 2011 ; Levinson and Gray, 2012 ; Whiten et al., 2012 ; Fuentes and Wiessner, 2016 ; Henrich, 2016 ; Bortolini et al., 2017 ; Turchin et al., 2018 ; Whitehouse et al., In press ). The field has now blossomed to the extent that researchers founded a dedicated academic society: the Cultural Evolution Society (Brewer et al., 2017 ; Youngblood and Lahti, 2018 ). Its inaugural conference in September 2017 at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History was attended by 300 researchers from 40 countries (Savage, 2017 ) Footnote 3 .

Language has proven to be particularly amenable to evolutionary analysis. For example, applying phylogenetic methods from evolutionary biology to standardized lists of 200 of the most universal and slowest-changing words (e.g., numbers, body parts, kinship terminology) from hundreds of existing and ancient languages has allowed researchers to reconstruct the timing, geography, and specific mechanisms of change by which the descendants of proto-languages such as Proto-Indo-European or Proto-Austronesian evolved to become languages such as English, Hindi, Javanese, and Maori that are spoken today (Levinson and Gray, 2012 ). These evolutionary relationships can be represented as phylogenetic trees or networks (with some caveats, c.f. Doolittle, 1999 ; Gray et al., 2010 ; Le Bomin et al., 2016 ; Tëmkin and Eldredge, 2007 ). Such phylogenies can in turn be useful for exploring more complicated evolutionary questions, such as regarding the existence of cross-cultural universals (including universal aspects of music, cf. Savage et al., 2015 ]) or gene-culture coevolution (e.g., the coevolution of lactose tolerance and dairy farming, Mace and Holden, 2005 ).

Although modern cultural evolutionary theories have made many of the earlier criticisms about cultural evolution obsolete (e.g., assumptions of progress or of memetic replicators directly analogous to genes; cf. Henrich et al., 2008 ), there is still an active debate about the value of cultural evolution, with critics coming from both the sciences and the humanities. For example, evolutionary psychologist Steven Pinker ( 2012 ) still maintains that cultural evolution is simply a “loose metaphor” that “adds little to what we have always called ‘history’", echoing similar criticisms made by historian Joseph Fracchia and geneticist Richard Lewontin ( 1999 , 2005 ). Biological anthropologist Jonathan Marks has also strongly criticized cultural evolution as being based on “false premises” (Marks, 2012 , p. 40) and adding little value beyond traditional explanations from cultural anthropology. It seems fair to say that, while cultural evolution is making a comeback and the basic idea that culture changes over time is beyond dispute, the idea that evolutionary theory and its methods can enhance our understanding of cultural change and diversity has yet to unambiguously prove its value. Perhaps music might be one area that could help?

Musical evolution and early comparative musicology

I have previously outlined some modern cultural evolutionary theory as part of one of five major themes in a "new comparative musicology" (Savage and Brown, 2013 ), including the relationships between cultural evolution and the other four themes (classification, human history, universals, and biological evolution) Footnote 4 . Early comparative musicologists, however, relied on Spencer's notion of progressive evolution rather than Darwin's of phylogenetic diversification (Rehding, 2000 ) Footnote 5 . Two assumptions were fundamental to much of the work of the founding figures of comparative musicology:

1. Cultures evolved from simple to complex, and as they do so they move from primitive to civilized.

2. Music evolves from simple to complex within societies as they progress. (Stone, 2008 , p. 25)

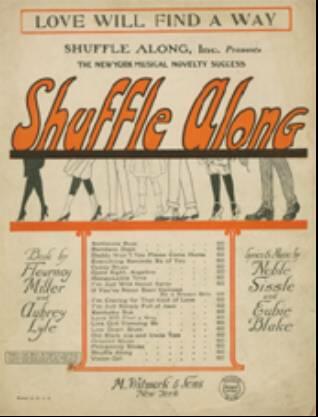

For example, in The Origins of Music , Carl Stumpf wrote of "the most primitive songs, e.g., those of the Vedda of Ceylon…. One may label them as mere preliminary stages or even as the origins of music." (Stumpf, 1911/ 2012 , p. 49). As late as 1943, Curt Sachs wrote of "the plain truth that the singsong of Pygmies and Pygmoids stands infinitely closer to the beginnings of music than Beethoven’s symphonies and Schubert’s lieder…the only working hypothesis admissible is that the earliest music must be found among the most primitive peoples" (Sachs, 1943 , p. 20–21). Scholars from the “Berlin school” of comparative musicology such as Stumpf, Sachs, and Erich von Hornbostel created the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv, the first archive of traditional music recordings from around the world, motivated in part by the belief that they could use these recordings to reconstruct the cultural evolution of complex Western art music from the simpler music of hunter-gatherers (Nettl and Bohlman, 1991 ; Nettl, 2006 ).

As the previous section made clear, old assumptions about the roles of progress and genes in evolution have been discarded by modern cultural evolutionary scholars. Nevertheless, ethnomusicologists still often equate ideas about the cultural evolution of music with those of the early comparative musicologists. Rahaim opens his response to Grauer by noting that his use of “the unfashionable language of human genetics and evolutionary biology” would lead many ethnomusicologists to be suspicious:

Would the "echoes of forgotten ancestors" turn out to be echoes of Social Darwinism? Was this to be a retelling of the story of modern Europe's heroic musical ascent above the rest of the world? (Rahaim, 2006 , p. 29)

Similarly, Mundy’s response to Grauer states that "the conception of progress inherent in evolution creates its own hierarchies" (Mundy, 2006 , p. 22). Elsewhere, Kartomi ( 2001 , p. 306) rejected the application of evolutionary theory in classifying musical instruments because "the concepts of evolution and lineage are not applicable to anything but animate beings, which are able to inherit genes from their forebears" Footnote 6 . Overall, since changing its name from comparative musicology to ethnomusicology during the middle of the 20th century, the field has largely avoided discussion of musical evolution, and recent advances in our understanding of cultural evolution have yet to make a substantial impact on musicology.

Macroevolution and Cantometrics

One striking exception to the general tendency to avoid theories of musical evolution in the second half of the twentieth century was Alan Lomax's Cantometrics Project (Lomax, 1968 , 1989 ; Lomax and Berkowitz, 1972 ). Although mostly (in)famous for its claims for a functional relationship between song style and social structure, another controversial aspect was Lomax's evolutionary interpretation of the global distribution of song style itself (for detailed critical review of the Cantometrics Project, see Savage, 2018 and Wood, 2018 a, 2018 b).

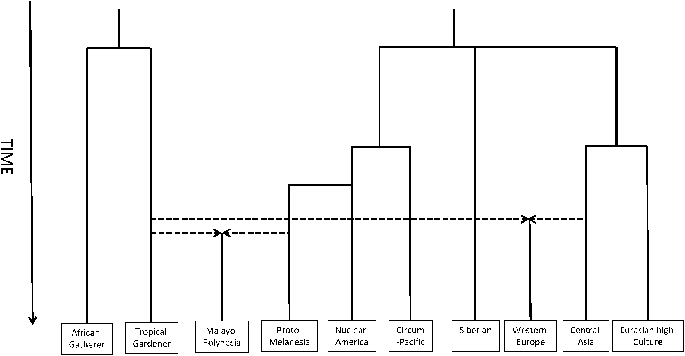

Through standardized classification and statistical analysis of 36 stylistic features from approximately 1800 traditional songs from 148 societies Footnote 7 , Lomax classified the world's musical diversity into 10 regional styles. Although this classification was not itself based on any evolutionary assumptions, Lomax proceeded to organize and interpret these 10 styles in the form of a crude phylogenetic tree:

This tree of performance style appears to have two roots: (1) in Siberia and (2) among African Gatherers. The Siberian root has two branches: one into the Circum-Pacific and Nuclear America, thence into Oceania through Melanesia and into East Africa, the second branch to Central Asia and thence into Europe and Asian High Culture... the main facts of style evolution may be accounted for by the elaboration of two contrastive traditions…. As their cultural base became more complex, these two root traditions became more specialized: the Siberian producing the virtuosic solo, highly articulated, elaborated, and alienated style of Eurasian high culture, the Early Agriculture tradition developing more and more cohesive and complexly integrated choruses and orchestras. West Europe and Oceania, flowering late on the borders of these two ancient specializations, show kinship to both. (Lomax, 1980 , p. 39–40)

Although this tree retains some aspects of progressivism (e.g., contemporary African gatherers occupying the "roots" while other traditions "became more complex", West Europe "flowering late"), it also shows more sophisticated concepts such as the possibility of multiple ancestors (polygenesis) and of borrowing/merging between lineages (horizontal transmission). With some modifications, it can be converted into a phylogenetic model as a working hypothesis for future testing/refinement (see Fig. 2 ) Footnote 8 .

A simplified phylogenetic model of global macroevolution of 10 song-style regions. Adapted from Fig. 2 of Lomax ( 1980 , p. 39), which is based on an analysis of ~1800 songs from 148 cultural groups using 36 Cantometric features. Lomax originally placed cultures at different stages along the vertical axis, but here all cultures are represented at the present time and the distance along the phylogenetic branches instead represents approximate time since diverging from a shared ancestral musical style. Dashed arrows represent horizontal transmission (borrowing/fusion) between lineages. Lomax's song-style region names varied—here I chose the most geographically descriptive names from Lomax's 1980 and 1989 publications (e.g., "Eurasian High Culture" instead of "Old High Culture")

Cantometrics provided the major point of departure both for Grauer's essay Footnote 9 and for a series of recent scientific studies exploring parallels in musical and genetic evolution. Some of these studies have directly compared patterns of musical and genetic diversity among populations of certain regions (e.g., Sub-Saharan Africa [Callaway, 2007 ], Eurasia [Pamjav et al., 2012 ], Taiwan [Brown et al., 2014 ], Northeast Asia [Savage et al., 2015 ]). All of these studies found that musical similarities between populations tend to be moderately correlated with genetic similarities, suggesting that both music and genes preserve histories of human migration and cultural contact.

Others have analyzed musical change using theories and methods from evolutionary biology. For example, Zivic et al. ( 2013 ) linked traditional periodization boundaries in Western classical music (Baroque, Classical, Romantic, 20 th century) to changes in pitch distribution patterns, while Serrà et al. ( 2012 ) and Mauch et al. ( 2015 ) both quantified the evolution of diversity in Western popular music, with the former concluding that musical diversity was decreasing while the latter rejected this conclusion in favor of a more complex “punctuated evolution” model (see further discussion below in the section on “Reductionism”). Although the details differ greatly, these studies share a common thread in arguing that musical evolution follows patterns and processes that can be usefully understood using theories and methods adapted from the study of biological evolution (see also Bentley et al., 2007 ; Interiano et al., 2018 ; Brand et al., 2019 ).

Like Cantometrics, most of these studies are more interested in the macroevolutionary relationships between cultures/genres than in microevolutionary relationships among songs within cultures/genres Footnote 10 . This makes them more amenable to broad cross-cultural comparison with domains such as population genetics and linguistics, as focusing on ethnolinguistically defined populations has proved useful in other fields of cultural and biological evolution. However, one drawback to such studies is that it is difficult to reconstruct the precise sequence of small microevolutionary changes that may have given rise to these large cross-cultural musical differences (Stock, 2006 ).

Microevolution and tune family research

One area of research strikingly absent from the discussion of musical evolution surrounding Grauer's essay was the extensive research on microevolution of tune families (groups of melodies sharing descent from a common ancestor or ancestors). Tune family research was particularly influenced by the realization in the early twentieth century that many traditional ballads that had become moribund or extinct in England were flourishing in modified forms far away in the US Appalachian mountains (Sharp, 1932 ). Cecil Sharp's folk song collecting led him to formulate a theory of musical evolution incorporating essentially the same three key mechanisms recognized by modern evolutionary theory: (1) continuity, (2) variation, and (3) selection (Sharp, 1907 ; note that Sharp used the term “continuity” rather than the modern term “inheritance” discussed above). These three principles were later developed by Sharp’s disciple, Maud Karpeles, who helped draft an official definition of folk music adopted in 1955 by the International Folk Music Council (the ancestor of today's International Council for Traditional Music Footnote 11 ) that explicitly invoked evolutionary theory:

Folk music is the product of a musical tradition that has been evolved through the process of oral transmission. The factors that shape the tradition are: (i) continuity which links the present with the past; (ii) variation which springs from the creative impulse of the individual or the group; and (iii) selection by the community, which determines the form or forms in which the music survives. (International Folk Music Council, 1955 , p. 23, emphasis added)

The general mechanisms proposed by Sharp and Karpeles for British-American tune family evolution were explored more thoroughly by scholars such as Bertrand Bronson ( 1959 –72, 1969 , 1976 ), Samuel Bayard ( 1950 , 1954 ), Charles Seeger ( 1966 ), Anne Shapiro ( 1975 ) Footnote 12 , Jeff Titon ( 1977 ), and James Cowdery ( 1984 ; 2009 ). In some cases, the melodic parallels were made explicit by aligning notes thought to share descent from a common ancestor and by verbally reconstructing the historical process of evolutionary changes. For example, Bayard used a series of melodic alignments to illustrate the "process, often conceived but seldom actually observed... of a tune's having material added onto its end and also losing material from its beginning", giving "evolution of one air out of another by variation, deletion, and addition" (Bayard, 1954 , p. 25). Charles Boilès ( 1973 ) even proposed a formal method for reconstructing ancestral proto-melodies, based on the linguistic comparative method for reconstructing proto-languages. Bronson attempted to automate such attempts on a vast scale. His attempts to use punch-cards to mechanically sort thousands of melodic variants of Child ballads and other traditional British-American folk melodies into tune families (Bronson, 1959– 72 , 1969 ) represented one of the first uses of computers in musicology, even preceding Lomax’s Cantometrics Project Footnote 13 .

During my own studies in Japan, I learned that scholars of Japanese music had developed similar approaches based on alignment of related melodies to understand musical evolution, although without explicit reference to tune family research. For example, Kashō Machida and Tsutomu Takeuchi ( 1965 ) traced the evolution of the famous folk songs Esashi Oiwake and Sado Okesa from their simpler, unaccompanied beginnings in the work songs of distant prefectures, and Atsumi Kaneshiro ( 1990 ) developed a quantitative method that he used to test proposed relationships within Esashi Oiwake 's tune family. Meanwhile, Laurence Picken and colleagues traced the evolution of modern Japanese gagaku melodies for flute and reed-pipe back over a thousand years to the simpler and faster ancient melodies of China's Tang court (Picken et al., 1981 –2000; Marett, 1985 ).

Tune family scholarship has not been limited to British-American and Japanese music—those just happen to be the two traditions I am most familiar with. Elsewhere, scholars such as Béla Bartók ( 1931 ) and Walter Wiora ( 1953 ) studied tune family evolution in European folk songs, Steven Jan ( 2007 ) studied the evolution of melodic motives in Western classical music, and Joep Bor ( 1975 ) and Wim van der Meer ( 1975 ) made detailed arguments for treating North Indian ragas as evolving "melodic species" (Bor, 1975 , p. 17).

Recently, scientists have attempted to apply microevolutionary methods to a variety of Western and non-Western genres in the form of sequence alignment techniques adapted from molecular biology (Mongeau and Sankoff, 1990 ; van Kranenburg et al. 2009 ; Toussaint, 2013 ; Windram et al., 2014 ; Savage and Atkinson, 2015 ). Such techniques make it possible to automate things like quantifying melodic similarities and identifying boundaries between tune families (Savage and Atkinson 2015 ; Jan, 2018 ), making analysis possible on vast scales that would be impossible to perform manually.

In addition, some scientists have explored musical microevolution in the laboratory, using techniques originally designed to explore controlled evolution of organisms and languages. Thus, one group mimicked sexual reproduction by having short audio loops recombine and mutate, then used an online survey to allow listeners to mimic the process of natural selection on the resulting music, finding that esthetically pleasing music evolved from nearly random noise over the course of several thousand generations solely under the influence of listener selection (MacCallum et al., 2012 ) Footnote 14 . Using a different experimental paradigm similar to the children's game Telephone, other groups found that melodies and rhythms became simpler and more structured in the course of transmission, paralleling findings from experimental language evolution (Ravignani et al., 2016 ; Jacoby and McDermott, 2017 ; Lumaca and Baggio, 2017 ). Like biological evolution and language evolution, our knowledge of musical evolution can be enhanced by combining ecologically valid studies of musical evolution in the wild (i.e., in its cultural context) with controlled laboratory experiments.

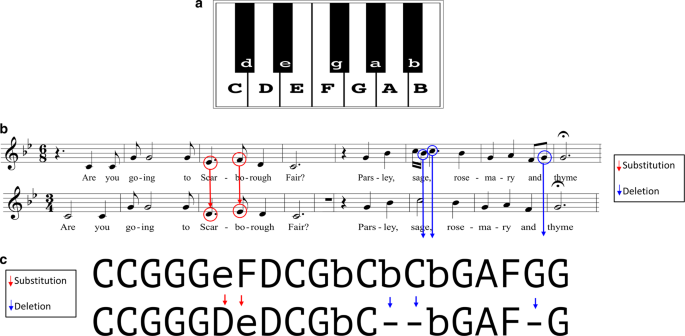

So far, the microevolution of tune families has been investigated largely independently in a variety of cultures and genres, without much attempt at comparing them to explore general patterns of musical evolution. One reason for this is that a broader cross-cultural comparison would require standardized methods for analyzing and measuring musical evolution in different contexts. I proposed such a method and applied it to several of the cases studies discussed above (Savage and Atkinson, 2015 ; Savage, 2017 ). Figure 3 shows an example of this method using an example of melodic microevolution in a well-known folk song: Scarborough Fair .

An example of analyzing tune family microevolution through melodic sequence alignment. The opening two phrases of Simon and Garfunkel's phenomenally successful 1966 version of Scarborough Fair (bottom melody) and its immediate ancestor, Martin Carthy's 1965 version (top melody) are shown, transposed to the common tonic of C (cf. Kloss, 2012 for a detailed discussion of the historical evolution of this ballad). In b , the melodies are shown using standard staff notation, while in c they are shown as aligned note sequences, with letters corresponding to notes as shown in a (following Savage and Atkinson, 2015 ). See Savage ( 2017 ) for a detailed explanation of how this evolution can be quantified (percent melodic identity = 81%; mutation rate = 0.25 per note per year) and discussion of the mechanisms of note substitutions (red arrows) and deletions (blue arrows) shown here

By demonstrating consistent cross-cultural and cross-genre trends in the rates and mechanisms of melodic evolution, I showed that musical evolution, like biological evolution, follows some general rules (Savage, 2017 ). For example, notes with stronger structural function are more resistant to change (e.g., rhythmically accented notes more stable than ornamental notes), and notes are more likely to change to melodically neighboring notes (e.g., 2nds) than to distant ones (e.g., 7ths; cf. Fig. 3 ). This suggests that a general theory of evolution may prove a helpful unifying theory in musicology, as it has in biology.

Musical evolution applications: education and copyright

All musicology is in some sense applied through our research, teaching, and outreach, but some is more explicitly applied for the benefit of those outside of academia (Titon, 1992 ). In this article, I argue that cultural evolutionary theory can provide a useful unifying theoretical framework to apply to research on understanding and reconstructing musical change at multiple levels (both macro and micro) across cultures, genres, and time periods. I now briefly discuss two other ways it can be more directly applied: education and copyright.

The world's musical diversity is woefully underrepresented at all levels of education. Often the job of correcting this falls to ethnomusicologists teaching survey courses on "World Music". As Rahaim ( 2006 , p. 32) notes, "as teachers, we often find ourselves in situations that require us to say something in short-hand about [musical] origins, and have few models at hand apart from evolution". Evolutionary models like Lomax's world phylogenetic tree of regional song style (Fig. 2 ) provide a simple and convenient starting point for teaching about similarities and differences in the world's music, and are flexible enough to adapt to diverse contexts such as conservatory classrooms, instrument museums, or pop music recommendation websites. Such coarse models can be further improved and/or nuanced by following them with microevolutionary case studies of musical change in specific cultures. An evolutionary approach further provides the chance to teach about connections beyond music to other domains in order to understand the ways in which the global distribution of music may be related to the distributions of the people who make it and to other aspects of their culture such as language or social structure (Lomax, 1968 ; Savage and Brown, 2013 ; Grauer, 2006 ).

Since almost all music is influenced by the past in at least some way, whether such influence is within norms of creativity and tradition or amounts to plagiarism is connected to an understanding of processes of musical evolution. US copyright law resembles concepts of tune family evolution in that the core copyrightable essence of a song consists of its representation in musical notation, and that the degree of overall melodic correspondence at structurally significant places between two tunes is a primary criterion for deciding whether the level of similarity constitutes plagiarism (Cronin, 2015 ; Fruehwald, 1992 ; Müllensiefen and Pendzich, 2009 ; Fishman, 2018 ) Footnote 15 . Thus, one famous case concluded that the melody of George Harrison's My Sweet Lord (1970) was similar enough to the Chiffons' He's So Fine (1962) as to constitute subconscious plagiarism (Judge Owen, 1976 ). I used new evolutionary methods involving sequence alignment of melodies to confirm that not only do the two tunes share over 50% identical notes, but the differences that do exist are consistent with the most common types of melodic change (e.g., insertion/deletion of ornamental notes, substitution to melodically neighboring notes; Savage, 2017 , cf. Fig. 3 ). Using a sample of 20 court cases, including He’s So Fine , I showed that this melodic sequence alignment method is a strong predictor of copyright infringement decisions, accurately predicting 16 out of the 20 cases (Savage et al., 2018 ).

However, the concept of individual ownership by composers in copyright law differs from concepts of folk song tune families, where traditional tunes are usually considered to be general property of the community. They are also different from conceptions in many non-Western cultures in which the essence of song ownership may be considered to lie not in its notated melody but in the performance style, performance context, or other extra-melodic features (A. Seeger, 1992 ). Even within US copyright law the question of what types and degrees of copying should be regarded as legitimate borrowing versus copyright infringement is hotly debated and dynamically interpreted, with musicians and lawyers commonly invoking evolutionary principles of continuity and variation to argue for the legitimacy of certain degrees of borrowing, as well as the principle of selection to argue against the deleterious effects on musical creativity if certain types of inspiration are overly restricted (Fishman, 2018 ).

The interpretation of copyright law can dramatically affect the livelihoods of musicians and communities around the world. Thus, a holistic understanding of general dynamics of musical evolution (including the many aspects beyond melodic evolution) and their specific manifestations in various musical cultures and genres may prove crucial to a more cross-culturally principled interpretation of concepts of creativity and ownership.

Objections to musical evolution: agency, meaning, and reductionism

Musical evolution has been and continues to be of interest to musicologists and non-musicologists alike. In fact, many of the processes I discuss are immediately recognizable to many under the terminology of musical change, for which musicologists have long sought a rigorous theory. Merriam ( 1964 , p. 307) argued that ethnomusicology "needs a theory of change". Over a half century later, Nettl ( 2015 , p. 292) summarizes that "there have been many attempts to generalize about change but no generally accepted theory". Why have musicologists interested in general theories of change not adopted the framework of evolution (which is, simply put, a formal theory of change)?

I have presented versions of this argument at international musicology conferences in the USA and Japan, receiving a variety of responses. Most objections to the use of evolutionary theory focused on three issues: implications of progress, individual agency, and reductionism. Since I have already clarified misconceptions about progress at length above Footnote 16 , I will focus here on agency and reductionism.

Building on arguments against cultural evolution by the evolutionary biologists Stephen Jay Gould and Richard Lewontin, Rahaim ( 2006 , p. 36) argues: "Perhaps most importantly for ethnomusicologists, metaphors of both situated and progressive evolution turn attention away from the agency of individuals". But does the concept of musical evolution negate the agency of individuals to create their own music any more than the concept of biological evolution negates individual free will? In each case, our cultural/genetic inheritances are the product of long evolutionary processes shaped by historical factors, but cannot be simply reduced to or wholly explained by such factors.

Musicians are often free to compose their own music or modify the existing repertoire in whatever ways they see fit (within the physical limits imposed by acoustics, neurobiology, etc.). But whether their creations will appeal to others and be passed on through the generations depends on a variety of factors beyond their control, including the sociopolitical context and the perceptual capacities of the audience. Thus, the role of the individual musicians in this process and their relationships with other actors (audiences, composers, accompanists, producers, judges, etc.) are in fact central to understanding the cultural evolution of music. As Seeger put it:

musical traditions depend on transmission, continuity, change, and interested audiences, but…these take place in a context of emerging mass media, the involvement of outsiders, and the often unpredictable actions of local and national governments. (Anthony Seeger, foreword to Grant, 2014 , p. 9)

Seeger's summary succinctly captures the three key evolutionary mechanisms of "continuity [inheritance], change [variation], and interested audiences [selection]", as well as their dynamic relationships with individual agency and cultural context.

My research has focused on identifying general constraints that apply across many individuals, but this does not mean that other studies must do so. For example, one potentially productive area for exploring the role of individual agency in musical evolution might involve comparing different performers attempting to create their own signature versions of music originally composed and/or performed by others. This could easily apply to a variety of cultures and genres, including art (e.g., the same symphony performed by different orchestras), popular (e.g., cover songs, hip-hop sampling; Youngblood, 2018 ), and folk (e.g., folk song variants; cf. the Scarborough Fair example in Fig. 3 ).

In fact, the presence of human agency and the intentional innovation that comes with it is one of the most interesting aspects about studying cultural evolution. In genetic evolution, natural selection provides the major explanatory mechanism due to the fact that genetic variation is arbitrary (i.e., genetic mutations are not directed towards particular evolutionary goals). However, in cultural evolution, both selection and variation can be directed consciously and unconsciously through a much broader range of mechanisms than typically found in genetic evolution. To accommodate this complexity, cultural evolutionary theorists have proposed a dizzying array of mechanisms to expand the terminological framework of evolutionary biology to cultural evolution (e.g., transmission biases based on prestige, aesthetics, or conformity/anti-conformity; guided variation driven by cognition and/or emotion; cultural attraction through processes of reconstructive rather than replicative transmission; Richerson and Boyd, 2005 ; Mesoudi, 2011 ; Claidière et al., 2014 ; Fogarty et al., 2015 ). The relative strengths of these different types of evolutionary mechanisms and their implications for musical evolution in particular and cultural evolution in general are hotly debated (Claidière et al., 2012 ; Leroi et al., 2012 ). Thus, this is an area where musicologists and cultural evolutionary theorists could both learn much from one another.

An anonymous reviewer of an earlier iteration of this article flatly stated that my cultural evolutionary approach “is not compatible with an anthropological understanding of culture, and seems instead to describe changes in the surface structures of music (tune families and the like)…”. This criticism seems to echo Rahaim’s concerns about agency discussed above, but also goes even further into the longstanding debate regarding the roles of sound vs. behavior, process vs. product, etc. in musicology (Merriam, 1964 ; Rice, 1987 ; Solis, 2012 ). In particular, it follows criticisms by Blacking ( 1977 ) and Feld ( 1984 ) of Lomax’s attempts to use Cantometrics to understand cultural evolution. As Blacking ( 1977 , p. 10) puts it: “Lomax compares the surface structures of music without questioning whether the same musical sounds always have the same "deep structure" and the same meaning”.

Unlike language, music generally lacks clear referential semantic meaning (Meyer, 1956 ; Patel, 2008 ), and this crucial difference is one reason we must be cautious about uncritically borrowing linguistic concepts wholesale to apply to music (Feld, 1974 ). While I agree that a full understanding of the cultural evolution of music will require integrating understanding of both sound structures and their meanings, I can not accept the implication that the study of musical structures such as tune families are not an appropriate subject of musicological inquiry. Here I can only respond by quoting the final sentence published by Alan Merriam ( 1982 ): “ethnomusicology for me is the study of music as culture, and that does not preclude the study of form; indeed we cannot proceed without it.".

Reductionism

Another critique I would like to mention is a broader but related one regarding reductionism and science. This criticism was levelled at cultural evolution in general by Fracchia and Lewontin ( 1999 , p. 507): "the demand for a theory of cultural evolution is really a demand that cultural anthropology be included in the grand twentieth-century movement to scientize all aspects of the study of society, to become validated as a part of ‘social science'".

One version of this criticism appeared in response to one of the studies cited in this review entitled “Measuring the Evolution of Contemporary Western Popular Music” (Serrà et al., 2012 ). In response, Fink ( 2013 ) made a persuasive refutation of the paper’s central finding of decreasing musical diversity and the newspaper headlines touting it (“Modern Music too Loud, All Sounds the Same”), pointing out that the analyses failed to detect increasing rhythmic diversity because the methods ignored rhythm. Or, as Fink put it: "Music isn’t getting stupider, it’s getting funkier.”

Nevertheless, Fink argues that the same reductionistic science that made the study’s conclusion misleading was also a reason it made headlines:

as reporters rush to assure us, they are newsworthy because, for the first time, the conclusions are backed with hard data, not squishy aesthetic theorizing. The numbers do not lie. But research can only be as good as the encoded data it’s based on; look under the surface of recently reported computer-enabled analyses of pop music and you’ll find that the old programmer’s dictum—“garbage in, garbage out”—is still the last word. (Fink, 2013 )

Not long after Serrà et al. published their study, Mauch et al. ( 2015 ) also measured the evolution of Western popular music over a similar time period, but using less reductionistic methods that importantly included rhythmic features. Mauch et al. came to the opposite conclusion: musical diversity actually increased after a brief decline during the 1980s. This provides quantitative support for Fink’s criticism above. Overall, this case highlights both the value of quantifying the cultural evolution of music and the importance of critical thinking in interpreting the reductionism inherent in such studies. Although science does generally require some level of reductionism, the goal is to be “as simple as possible, but not simpler” Footnote 17 .

Charges of reductionism were also leveled directly at my own (Savage and Brown, 2013 ) proposal that included cultural evolution as one of five major themes in a new comparative musicology. In a thorough and nuanced review entitled "On Not Losing Heart", David Clarke approved of the call for more cross-cultural comparison, but worried about its "strongly empiricist paradigm":

Lomax's particular mode of integration "between the humanistic and the scientific" [was] fueled by a politics that had an emancipatory motive. In the metrics and technics of the new comparative musicology proposed by Savage and Brown, traces of any such informing polity melt into air….A political neutrality that is the correlate of an unalloyed empiricism is problematic….My own predilections here are perhaps more attuned to ethnomusicologists who are interested in the particularities of a culture and the actual experience of encounter in the field. By contrast, Savage, Brown, et al. advocate different epistemological values with a different ethos, based on the abstraction of music and people into data. To characterize that ethos as a recapitulation of Lomax, only without the heart, might be an unfair caricature. For the various statistical representations and correlations emerging from their research may well be sublimating a lot of passion, and Savage and Brown’s own day-to-day dealings with musicians and musicking may be no less affective than anyone else’s (it’s just that they exclude this from their research) Footnote 18 . (Clarke, 2014 , 6, pp. 11–12)

While Clarke argues that a "political neutrality that is the correlate of an unalloyed empiricism is problematic", I believe it may be valuable to maintain a relatively neutral political stance, in large part to avoid the problems of confirmation bias that were leveled at Lomax. With Cantometrics, Lomax sought to scientifically validate his strong political views regarding "cultural equity" (Lomax, 1977 ). One of the concerns that doomed Cantometrics was that Lomax's analyses were viewed as being too strongly biased by his political views (Savage, 2018 ; Szwed, 2010 ; Wood, 2018a , 2018b ). Personally, I strongly share Lomax's views about the value of cultural equity, and I, too, see quantitative data as a helpful tool in arguing for the value of all of the world's music. However, I believe it is legitimate to try to limit political aspects in one's published work, and it may well be a more effective long-term strategy for the types of applications described in the previous section Footnote 19 .

Certainly, neither a purely qualitative, ethnographic approach nor a purely quantitative, scientific approach alone will succeed in advancing our knowledge of how and why music evolves. But by combining the two approaches through cross-cultural comparative study, we can achieve a better understanding of the forces governing the world's musical diversity and their real-world implications (Savage and Brown, 2013 ). For instance, the My Sweet Lord plagiarism case mentioned above gives a clear example where quantitative measurements of the degree of melodic similarity (56%) between two tunes and its qualitative interpretation in the context of copyright law has major practical implications in which millions of dollars are at stake. Although perhaps less easily quantified in terms of dollar values, an understanding of the mechanisms of evolution of traditional folk songs may be just as valuable to traditional musicians struggling to protect their intangible cultural heritage.

Music evolves, through mechanisms that are both similar to and distinct from biological evolution. Cultural evolutionary theory has been developed to the point that it shows promise for providing explanatory power from the broad levels of macroevolution of global musical styles to the minute microevolutionary details of individual performers and performances. Musical evolution shows potential for applications beyond research to such disparate domains as education and copyright.

However, I am aware that my review is inevitably incomplete and I have only been able to highlight a tiny fraction of the types of situations and methodologies through which the evolutionary framework can be fruitfully applied to music. To me, that incompleteness highlights the broad explanatory power of evolutionary theory, and broad explanatory theory is something that musicologists such as Timothy Rice ( 2010 ) have argued is sorely needed.

Scientific interest in musical evolution is already growing rapidly, and will continue with or without the involvement of musicologists. Here again, we can learn from language evolution. Several high-profile articles on language evolution were published by teams of scientists without close collaboration with linguists, resulting in bitter disputes and accusations of "naïve arrogance" (Campbell, 2013 , p. 472) that have limited what could have been mutually beneficial collaboration (Marris, 2008 ). A similar pattern seems to be playing out in the recent controversy regarding a team of Harvard scientists analyzing ethnographic recordings around the world to construct a “Natural History of Song” (Mehr et al. 2018 a, 2018 b; Marshall, 2018 ; Yong, 2018 ). I share concerns about scientists studying music and evolution without collaborating with musicologists, but I believe that ultimately both musicology and cultural evolution stand to benefit from productive interdisciplinary collaboration. I have chosen to try to avoid such pitfalls by being proactive in initiating collaborations on musical evolution with cultural evolutionary scientists to combine our knowledge and skills (e.g., Savage et al. 2015 ; Savage and Atkinson, 2015 ).

I do not intend by any means to imply that the predominantly quantitative approach I have presented here—strongly informed by my collaborations with scientists studying cultural and biological evolution, as well as my own earlier training in psychology and biochemistry - is the only way to study musical evolution. One reason I focused in my dissertation on a rigorously quantitative approach modeled on molecular genetics is that such quantitative approaches have shown success in rehabilitating cultural evolutionary theory after much criticism of earlier incarnations such as memetics as lacking in empirical rigor (Laland and Brown, 2011 ; Mesoudi, 2011 ). But I believe that one of the strengths of evolutionary theory is that it is flexible enough to be usefully adapted to a variety of scientific and humanistic methodologies, with plenty of room to coexist productively with non-evolutionary theories. As Ruth Stone ( 2008 , p. 225) has noted, "there is no such thing as a best theory. Some theories are simply more suited for answering certain kinds of questions than others" (emphasis in original). Even if the concept of cultural evolution cannot provide all the answers, I believe it helps to answer enough musical questions of abiding interest that it should be ignored no more.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

For reasons of space and expertise, I will focus here primarily on the ethnomusicological literature, but the concept of cultural evolution of music should also be applicable to other sub-fields, not least the evolution of contemporary Western classical music from medieval Gregorian chant over the course of the second millennium AD.

Although this movement came to be known as “Social Darwinism”, it was in fact not very reflective of Darwin′s ideas, but rather the ideas of Herbert Spencer ( 1875 ), who coined the term "survival of the fittest". While the historical relationship between evolutionary theory and Social Darwinism is debated, today′s scholars of cultural evolution unequivocally reject such political misappropriation of evolutionary theory (Laland and Brown, 2011 ; Mesoudi, 2011 ; Richerson and Boyd, 2005 ; Wilson and Johnson, 2015 ).

Two of these presentations were about music: my own about the evolution of British-American and Japanese folk song melodies and one by Aurélie Helmlinger

about the evolution of steelpan instrumental layouts in Trinidad and Tobago. The 2018 Cultural Evolution Society conference featured an entire panel with four presentations devoted to music.

Due to space limitations this article will not delve into the areas of biological evolution and gene-culture evolution of musicality (Honing, 2018 ; Tomlinson, 2013 , 2015 ; Patel, 2018 ; Savage et al., In prep.).

Of the musicologists responding to Grauer′s essay, only Rahaim ( 2006 , p. 29) carefully distinguished between these two, using the terms "progressive" and "situated" evolution, respectively.

Kartomi has since changed her views, writing "I now think that music has evolved in a measurable way, as long as ′evolved′ is not defined as ′improved′" (personal communication, June 10th 2016 email to the author).

Discrepancies in published numbers and further details are explained by Savage ( 2018 ).

Although not shown here, finer-scale relationships within and among groups can also be modeled using evolutionary methods (cf. Fig. 3 of Lomax, 1980 , p. 41; Rzeszutek et al., 2012 ; Savage and Brown, 2014 ).

Grauer was heavily involved in the Cantometrics Project as both the co-inventor of the Cantometric classification scheme and primary coder of the Cantometric data.

Macroevolution generally refers to changes among populations (e.g., species, cultural groups), while microevolution generally refers to changes within populations.

Lineages of organizations, composers, performers, etc. are a potentially productive area of studying musical evolution, but I will not discuss them in detail here due to limitations of space and expertise.

Unfortunately, Shapiro′s dissertation was never published and is not available for interlibrary loan.

The research leading to the articles republished in book form in Bronson ( 1969 ) was begun several decades earlier, with one article laying out the basic idea of “Mechanical Help in the Study of Folk Song” published as early as 1949.

Note that this finding is conceptually distinct from the “sound-to-music illusion” (Simchy-Gross and Margulis, 2018 ). The sound-to-music illusion involves the same sound being perceived as more musical after repeated listening by a single listener, whereas MacCallum et al.′s study experimentally evolved new and more pleasing music over time.

Note, however, that Fishman ( 2018 ) in particular has argued that the traditional emphasis on melody may be changing, as evidenced by recent high-profile cases such as the dispute over Blurred Lines .

Unfortunately, the association of evolution with progress is particularly entrenched where I live in Japan, where the characters used to translate evolution (進化 [ shinka ]) literally mean "progressive change" (the English word evolution itself evolved from the Latin evolutio , meaning "unfolding"). In my opinion, those avoiding the term "evolution" because of misconceptions about its meaning are contributing to this popular misconception. Instead I believe concerted effort to correct this misconception for future generations is in order.

Anonymous quote attributed to Einstein (cf. Anonymous, 2011 ).

Personally, I do feel a lot of passion for the world′s musicians and see one of my life′s goals as being advocating for their value. My interest in folk song evolution was motivated not only by theoretical concerns about mechanisms of cultural microevolution, but on my own experiences learning and performing British-American and Japanese folk songs and my hopes that my (Japanese-New Zealand-American) children will be able to sing these songs that have been handed down to them over the course of hundreds of years from their ancestors on opposite sides of the world. I have won trophies in a number of Japanese folk song competitions, so questions about agency in performance and what types of musical (and extra-musical) variation are selected for or against are not merely academic but affect me personally. Do I think that all of these factors can be perfectly quantified? Absolutely not. But I do believe that theories of musical evolution informed by quantitative data could have a positive influence on musicology and beyond. As Clarke ( 2014 , p. 12) later admits: “in fairness, the empirical and the metric have as much potential as any other paradigm to work to humanistic ends”.

Language evolution provides another good analogy. Much work in language evolution focuses on the evolution of basic vocabulary due to its resistance to change and amenability to evolutionary analysis (Pagel, 2017 ). However, broader theories of language evolution incorporate many complex cognitive and social factors, including race, gender and class (Labov, 1994 –2010).

Adler G (1885) The scope, method, and aim of musicology. (Trans: Mugglestone E). Yearb Tradit Music 13(1–21):1981

Google Scholar

Allen JA, Garland EC, Dunlop RA, Noad MJ (2018) Cultural revolutions reduce complexity in the songs of humpback whales. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 285(20182088):1–6. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2018.2088

Article Google Scholar

Anonymous [Einstein, A.] (2011) Everything should be made as simple as possible, but not simpler. https://Quoteinvestigator.Com/2011/05/13/Einstein-Simple/ , Accessed 20 Aug 2018

Atkinson QD, Gray RD (2005) Curious parallels and curious connections: phylogenetic thinking in biology and historical linguistics. Syst Biol 54(4):513–526

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bartók B (1931) Hungarian folk music. Oxford University Press, London

Bayard SP (1950) Prolegomena to a study of the principal melodic families of British-American folk song. J Am Folk 63(247):1–44

Bayard SP (1954) Two representative tune families of British tradition. Midwest Folk 4(1):13–33

Bentley RA, Lipo CP, Herzog HA, Hahn MW (2007) Regular rates of popular culture change reflect random copying. Evol Human Behav 28(3):151–158

Blacking J (1977) Some problems of theory and method in the study of musical change. Yearb Int Folk Music Counc 9:1–26

Boilès CL (1973) Reconstruction of proto-melody. Anu Interam De Invest Musica 9:45–63

Bonduriansky R, Day T (2018) Extended heredity: a new understanding of inheritance and evolution.. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

Book Google Scholar

Bor J (1975) Raga, species and evolution. Sangeet Natak 35:17–48

Bortolini E, Pagani L, Crema ER, Sarno S, Barbieri C, Boattini A et al. (2017) Inferring patterns of folktale diffusion using genomic data. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114(34):9140–9145

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Boyd R, Richerson PJ (1985) Culture and the evolutionary process.. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Brand CO, Acerbi A, Mesoudi A (2019) Cultural evolution of emotional expression in 50 years of song lyrics. SocArXiv preprint. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/3j6wx

Brewer J, Gelfand M, Jackson JC, MacDonald IF, Peregrine PN, Richerson PJ et al. (2017) Grand challenges for the study of cultural evolution. Nat Ecol Evol 1(0070):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-017-0070

Bronson BH (1969) The ballad as song.. University of California Press, Berkeley

Bronson BH (1959) The traditional tunes of the Child ballads: with their texts, according to the extant records of Great Britain and America [4 volumes]. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1972

Bronson BH (1976) The singing tradition of Child’s popular ballads. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Brown S, Savage PE, Ko AM-S, Stoneking M, Ko Y-C, Loo J-H, Trejaut JA (2014) Correlations in the population structure of music, genes and language. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 281(1774):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.2072

Callaway E (2007) Music is in our genes. Nat News https://doi.org/10.1038/news.2007.359

Campbell L (2013) Historical linguistics: an introduction, 3rd edn. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh

Carneiro RL (2003) Evolutionism in cultural anthropology: a critical history. Westview Press, Boulder, CO

Cavalli-Sforza LL, Feldman MW (1981) Cultural transmission and evolution: a quantitative approach.. Princeton University Press, Princeton

MATH Google Scholar

Claidière N, Kirby S, Sperber D (2012) Effect of psychological bias separates cultural from biological evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109(51):E3526. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1213320109

Article ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Claidière N, Scott-Phillips TC, Sperber D (2014) How Darwinian is cultural evolution? Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 369(20130368):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2013.0368

Clarke D (2014) On not losing heart: a response to Savage and Brown’s “Toward a new comparative musicology.” Anal Approaches World Music 3(2):1–14

Cowdery JR (1984) A fresh look at the concept of tune family. Ethnomusicology 28(3):495–504

Cowdery JR (2009) The melodic tradition of Ireland, 2nd edn. Kent State University Press, Kent

Cronin C (2015) I hear America suing: Music copyright infringement in the era of electronic sound. Hastings Law J 66(5):1187–1254

Currie TE, Mace R (2011) Mode and tempo in the evolution of socio-political organization: reconciling “Darwinian” and “Spencerian” evolutionary approaches in anthropology. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 366:1108–1117

Article PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Danchin E, Charmantier A, Champagne FA, Mesoudi A, Pujol B, Blanchet S (2011) Beyond DNA: integrating inclusive inheritance into an extended theory of evolution. Nat Rev Genet 12:475–486

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Darwin C (1859) The origin of species by means of natural selection.. John Murray, London

Darwin C (1871) The descent of man, and selection in relation to sex.. John Murray, London

Dawkins R (1976) The selfish gene.. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Doolittle WF (1999) Phylogenetic classification and the universal tree. Science 284(5423):2124–2128

Feld S (1974) Linguistic models in ethnomusicology. Ethnomusicology 18(2):197–217

Feld S (1984) Sound structure as social structure. Ethnomusicology 28(3):383–409

Fink R (2013, August 25) Big (bad) data. Musicology Now. http://musicologynow.ams-net.org/2013/08/big-baddata.html

Fishman JP (2018) Music as a matter of law. Harv Law Rev 131(7):1861–1923

Fogarty L, Creanza N, Feldman MW (2015) Cultural evolutionary perspectives on creativity and human innovation. Trends Ecol Evol 30(12):736–754

Fracchia J, Lewontin RC (1999) Does culture evolve? Hist Theory 8:52–78

Fracchia J, Lewontin RC (2005) The price of metaphor. Hist Theory 44:14–29. February

Fruehwald ES (1992) Copyright infringement of musical compositions: a systematic approach. Akron Law Rev 26(1):15–44

Fuentes A, Wiessner P (2016) Reintegrating anthropology: from inside out - an introduction to. Curr Anthropol 57(S13):S3–S12. https://doi.org/10.1086/685694

Gould SJ (1989) Wonderful life: The Burgess Shale and the nature of history.. Norton, New York

Grauer VA (2011) Sounding the depths: tradition and the voices of history. CreateSpace: http://soundingthedepths.blogspot.com/

Grauer VA (2006) Echoes of our forgotten ancestors. World Music 48(2):5–58

MathSciNet Google Scholar

Grant C (2014) Music endangerment: How language maintenance can help.. Oxford University Press, New York

Gray RD, Bryant D, Greenhill SJ (2010) On the shape and fabric of human history. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 365:3923–3933

Henrich J (2016) The secret of our success: how culture is driving human evolution, domesticating our species, and making us smarter.. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Henrich J, Boyd R, Richerson PJ (2008) Five misunderstandings about cultural evolution. Hum Nat 19(2):119–137

Hofstadter R (1955) Social Darwinism in American thought.. Beacon Press, Boston

Honing H (ed) (2018) The origins of musicality. MIT Press, Cambridge

Howell FC (1965) Early man. Time-Life International, Amsterdam

Huron D (2006) Sweet anticipation: music and the psychology of expectation.. MIT Press, Cambridge

Interiano M, Kazemi K, Wang L, Yang J, Yu Z, Komarova NL (2018) Musical trends and predictability of success in contemporary songs in and out of the top charts. R Soc Open Sci 5(171274):1–16. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.171274

International Folk Music Council (1955) Resolutions: definition of folk music. J Int Folk Music Counc 7:23

Jacoby N, McDermott JH (2017) Integer ratio priors on musical rhythm revealed cross-culturally by iterated reproduction. Curr Biol 27:359–370

Jan S (2007) The memetics of music: a neo-Darwinian view of musical structure and culture. Ashgate, Hants

Jan S (2018) The Two Brothers: reconciling perceptual-cognitive and statistical models of musical evolution. Front Psychol 9(344):1–15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00344

Judge Owen (1976) Bright Tunes Music v. Harrisongs Music 420 F. Supp. 177 (S.D.N.Y. 1976). http://mcir.usc.edu/cases/1970-1979/Pages/brightharrisongs.html

Kaneshiro A (1990) [Comparison of Oiwake melodies through lyric-note alignment]. Minzoku Ongaku 5(1):30–36

Kartomi M (2001) The classification of musical instruments: changing trends in research from the late nineteenth century, with special reference to the 1990s. Ethnomusicology 45(2):283–314

Kloss J (2012) “... Tell Her To Make Me A Cambric Shirt”: from the “Elfin Knight” to “Scarborough Fair.” http://www.justanothertune.com/html/cambricshirt.html

Labov W (1994) Principles of linguistic change [3 vols].. Blackwell, Oxford, 2010

Laland KN, Brown GR (2011) Sense and nonsense, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, New York

Laland K, Uller T, Feldman M, Sterelny K, Müller GB, Moczek A et al (2014) Does evolutionary theory need a rethink? Researchers are divided over what processes should be considered fundamental Nature 514:161–164

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Lawson FRS (2012) Consilience revisited: musical and scientific approaches to Chinese performance. Ethnomusicology 56(1):86–111

Le Bomin S, Lecointre G, Heyer E (2016) The evolution of musical diversity: the key role of vertical transmission. PLoS ONE 11(3):1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0151570

Article CAS Google Scholar

Leroi AM, MacCallum RM, Mauch M, Burt A (2012) Reply to Claidière et al.: role of psychological bias in evolution depends on the kind of culture. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109(51):E3527. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1214445109

Article ADS PubMed Central Google Scholar

Leroi AM, Swire J (2006) The recovery of the past. World Music 48(3):43–54

Levinson SC, Gray RD (2012) Tools from evolutionary biology shed new light on the diversification of languages. Trends Cogn Sci 16(3):167–173

Lomax A (1977) Appeal for cultural equity. J Commun 27(2):125–138

Lomax A (1980) Factors of musical style. In: Diamond S (ed) Theory and practice: essays presented to Gene Weltfish. Mouton, The Hague, p 29–58

Chapter Google Scholar

Lomax A (1989) Cantometrics. In:Barnouw E (ed) International encyclopedia of communications, 1st edn Oxford University Press, New York, p 230–233

Lomax A, Berkowitz N (1972) The evolutionary taxonomy of culture. Science 177(4045):228–239

Lomax A (ed) (1968) Folk song style and culture. American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington, DC

Lumaca M, Baggio G (2017) Cultural transmission and evolution of melodic structures in multi-generational signaling games. Artif Life 23:406–423

Lumsden CJ, Wilson EO (1981) Genes, mind and culture: the coevolutionary process.. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

MacCallum RM, Mauch M, Burt A, Leroi AM (2012) Evolution of music by public choice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109(30):12081–12086

Article ADS CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Mace R, Holden CJ (2005) A phylogenetic approach to cultural evolution. Trends Ecol Evol 20(3):116–121

Machida K, Takeuchi T (eds) (1965) [Folk song genealogies: Esashi Oiwake and Sado Okesa]; 4 LPs. Kawasaki, Columbia. AL-5047/50

Marett A (1985) Togaku: where have the Tang melodies gone, and where have the new melodies come from? Ethnomusicology 29(3):409–431

Marks J (2012) Recent advances in culturomics. Evol Anthropol 21(1):38–42

Marris E (2008) The language barrier. Nature 453:446–448

Marshall A (2018, January 25) Can you tell a lullaby from a love song? Find out now. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/01/25/arts/music/history-of-song.html

Mauch M, MacCallum RM, Levy M, Leroi AM (2015) The evolution of popular music: USA 1960–2010. R Soc Open Sci 2(5):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsos.150081

McShea DW, Brandon RN (2010) Biology’s first law: the tendency for diversity and complexity to increase in evolutionary systems.. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Mehr SA, Singh M, Knox D, Lucas C, Ketter DM, Pickens-Jones D, Glowacki, L (2018) A natural history of song. PsyArXiv preprint https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/emq8r

Mehr SA, Singh M, York H, Glowacki L, Krasnow MM (2018) Form and function in human song. Curr Biol 28:356–368

Article CAS PubMed Central PubMed Google Scholar

Merriam AP (1964) The anthropology of music.. Northwestern University Press, Evanston

Merriam AP (1982) On objections to comparison in ethnomusicology. In: Falck R, Rice T (eds) Cross-cultural perspectives on music.. University of Toronto Press, Toronto, p 175–189

Mesoudi A (2011) Cultural evolution: how Darwinian theory can explain human culture and synthesize the social sciences.. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Meyer LB (1956) Emotion and meaning in music.. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Mongeau M, Sankoff D (1990) Comparison of musical sequences. Comput Hum 24:161–175

Müllensiefen D, Pendzich M (2009) Court decisions on music plagiarism and the predictive value of similarity algorithms. Musica Sci 13(1 Suppl):257–295

Mundy R (2006) Musical evolution and the making of hierarchy. World Music 48(3):13–27

Nei M, Suzuki Y, Nozawa M (2010) The neutral theory of molecular evolution in the genomic era. Annu Rev Genom. Hum Genet 11(1):265–289

CAS Google Scholar

Nettl B (2006) Response to Victor Grauer: on the concept of evolution in the history of ethnomusicology. World Music 48(2):59–72

Nettl B (2015) The study of ethnomusicology: thirty-three discussions, 3rd edn.. University of Illinois Press, Champaign

Nettl B, Bohlman PV (eds) (1991) Comparative musicology and anthropology of music: essays on the history of ethnomusicology.. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Pagel M (2017) Darwinian perspectives on the evolution of human languages. Psychon Bull Rev 24(1):151–157

Pamjav H, Juhász Z, Zalán A, Németh E, Damdin B (2012) A comparative phylogenetic study of genetics and folk music. Mol Genet Genom 287(4):337–349

Patel AD (2008) Music, language and the brain.. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Patel AD (2018) Music as a transformative technology of the mind: an update. In: Honing H (ed) The origins of musicality.. MIT Press, Cambridge, p 113–126

Picken LER, Wolpert RF, Nickson NJ (eds) (1981) Music from the Tang court [7 volumes]. Oxford/Cambridge University Press, London, p 2000

Pinker S (2012, June 18) The false allure of group selection. Edge. https://www.edge.org/conversation/steven_pinker-the-false-allure-of-group-selection

Ravignani A, Delgado T, Kirby S (2016) Musical evolution in the lab exhibits rhythmic universals. Nat Human Behav 1(0007):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-016-0007

Rahaim M (2006) What else do we say when we say “music evolves?”. World Music 48(3):29–41

Rehding A (2000) The quest for the origins of music in Germany circa 1900. J Am Musicol Soc 53(2):345–385

Rice T (1987) Toward the remodeling of ethnomusicology. Ethnomusicology 31(3):469–488

Rice T (2010) Disciplining ethnomusicology: a call for a new approach. Ethnomusicology 54(2):318–325

Richerson PJ, Boyd R (2005) Not by genes alone: How culture transformed human evolution.. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Rzeszutek T, Savage PE, Brown S (2012) The structure of cross-cultural musical diversity. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 279(1733):1606–1612

Sachs C (1943) The rise of music in the ancient world: east and West. Norton, New York

Savage PE (2017) [Measuring the cultural evolution of music: with case studies of British-American and Japanese folk, art, and popular music]. Ph.D. dissertation, Tokyo University of the Arts. https://tinyurl.com/SavagePhD

Savage PE (2017, September 25) ”Deep diversity” and other reflections on the inaugural Cultural Evolution Society conference. Seshat blog. http://seshatdatabank.info/cultural_evolution_society/

Savage PE (2018) Alan Lomax’s Cantometrics Project: a comprehensive review. Music & Sci 1:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/2059204318786084

Article ADS Google Scholar

Savage PE, Atkinson QD (2015) Automatic tune family identification by musical sequence alignment. In: Müller M, Wiering F (eds) Proceedings of the 16th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference (ISMIR 2015). Málaga, Spain, p 162–168

Savage PE, Brown S (2013) Toward a new comparative musicology. Anal Approaches World Music 2(2):148–197

Savage PE, Brown S (2014) Mapping music: cluster analysis of song-type frequencies within and between cultures. Ethnomusicology 58(1):133–155

Savage PE, Brown S, Sakai E, Currie TE (2015) Statistical universals reveal the structures and functions of human music. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112(29):8987–8992

Savage PE, Cronin C, Müllensiefen D, Atkinson QD (2018) Quantitative evaluation of music copyright infringement. In: Holzapfel A, Pikrakis A (eds) Proceedings of the 8th International Workshop on Folk Music Analysis (FMA2018). Thessaloniki, Greece, p 61–66

Savage PE, Loui P, Glowacki L, Schachner A, Tarr B, Mithen S, Fitch, WT (In preparation). Music as a coevolved system for social bonding.

Savage PE, Matsumae H, Oota H, Stoneking M, Currie TE, Tajima A, Brown S (2015) How “circumpolar” is Ainu music? Musical and genetic perspectives on the history of the Japanese archipelago. Ethnomusicol Forum 24(3):443–467