Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin (The)

By Rachel Lewis

Over eighteen years, from 1771 until his death, Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) composed an unfinished record of his life’s tribulations and successes. Written in simple, often humorous language, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin offered readers in the new United States an accessible, exemplary narrative of American upward mobility. An integral thread in the fabric of Franklin’s history, Philadelphia is the setting for much of the autobiography and the site where Franklin composed portions of the work.

The Autobiography is arranged in four parts, each with a distinct purpose and tone, though Franklin intended for the work to be read fluidly as a whole. He began writing The Autobiography in 1771, during a stay in London of more than ten years as a mediator between England and the American colonies. Although Philadelphia was Franklin’s home, this trip marked his third sojourn to England. As a young man, Franklin traveled to England in 1724-26 to expand his knowledge of the printing trade and then returned to Philadelphia where he would seize production of The Pennsylvania Gazette from Samuel Keimer (c. 1688-1742) and begin Poor Richard’s Almanack . After thirty years of building his reputation as a printer and civic leader, Franklin also spent five years in England as a diplomat for the Pennsylvania Assembly beginning in 1757.

Written during the era of tension between the British and the colonies caused by seemingly arbitrary taxation, Part One of The Autobiography takes the form of a letter addressed to Franklin’s son William (1731-1814), then serving as royal governor of New Jersey. Franklin documents his childhood and adolescence, including his arrival in Philadelphia and his achievements in the printing business. He recounts his lineage, depicts his early life in Boston, and documents his apprenticeship with his brother James (1697-1735), a printer. After a dispute with his brother, at the young age of seventeen Franklin leaves his apprenticeship and resolves to move secretly to New York. There, he has trouble finding work and thus moves to Philadelphia.

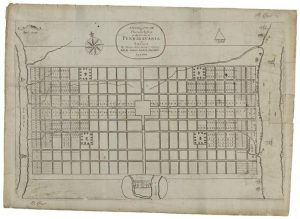

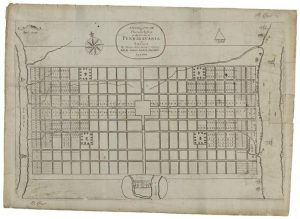

Part One chronicles Franklin’s eventful journey to Philadelphia, including his arrival by boat on October 6, 1723, after first docking in Burlington, New Jersey. Franklin calls attention to the contrast between his humble beginnings and entrance into Philadelphia and his eventual status as a businessman, civic leader, and public servant, addressing the reader directly: “You may in your Mind compare such unlikely Beginning with the Figure I have since made there.” Recalling the experience of arriving in his new city, he writes, “I knew no Soul, nor where to look for Lodging,” and then describes his first day in Philadelphia: “I walk’d up [Market] Street , gazing about, till near the Market House I met a Boy with Bread. I had many a Meal on Bread and inquiring where he got it, I went immediately to the Baker’s he directed me to in Second Street; and ask’d for Biscuit, intending such as we had in Boston, but they it seems were not made in Philadelphia.” Franklin’s first walk through the city took him west on Market Street to Fourth Street, then to Chestnut Street and Walnut Street, and “coming round found [himself] again at Market Street Wharf,” near where his boat was docked. At the end of his walk, Franklin entered “the Great meeting house of the Quakers near the market.” Although Franklin himself was not a Quaker, in The Autobiography he recounts the courtesy shown him by the Society of Friends: “I sat down among them, and, after looking round awhile and hearing nothing said, being very drowsy thro’ labour and want of rest the preceding night, I fell fast asleep, and continu’d so till the meeting broke up, when one was kind enough to rouse me. This was, therefore, the first house I was in, or slept in, in Philadelphia.”

Early Years in Philadelphia

In Philadelphia, Franklin creates a life for himself. He attempts to find work as a printer and struggles with financial burdens. Eventually he finds lodging with John Read (1677-1724), a carpenter and building contractor, and begins to court Read’s daughter, Deborah (1707-74). Throughout his young adulthood, Franklin spends time in London studying the printing trade (1724-26). In Philadelphia Franklin establishes “ The Junto ,” an intellectual and philosophical conversation group, where he first introduces the concept of the lending library. Franklin finds work as a printer with Samuel Keimer and in 1729 buys his newspaper, The Pennsylvania Gazette, and eventually becomes the official printer for the Pennsylvania Assembly.

Franklin’s writings became associated with American mythologies of success early on. A contemporary of Franklin, his friend and fellow diplomat Benjamin Vaughan (1751-1835), read Part One of the memoir-in-progress in 1783 and noted that it exemplified the American ideal of upward social mobility: “All that has happened to you, is connected with the detail of the manners and situation of a rising people.” Vaughan’s statement, written in the aftermath of the American Revolution, speaks not only to Franklin’s achievement as an individual but also to the milieu in which he was writing and his audience of Americans in search of national and individual identities.

Franklin began writing Part Two of his autobiography in 1784 while serving as the United States minister plenipotentiary to France. This section is perhaps the best known of The Autobiography because it includes Franklin’s list of thirteen virtues for self-improvement: Temperance, Silence, Order, Resolution, Frugality, Industry, Sincerity, Justice, Moderation, Cleanliness, Tranquility, Chastity, and Humility. Franklin puts forth a plan to develop one virtue per week, intending to eventually perfect all thirteen virtues. Franklin’s virtues are meant to appeal to people of all religions, making his tenets for moral perfection a viable option for all people. Franklin’s emphasis on these thirteen virtues in The Autobiography has been cited as the impetus for self-help literature. Although inspirational for many, the message of self-improvement also drew negative criticism from such notable and varied figures as John Adams (1735-1826) and Abigail Adams (1744-1818), Mark Twain (1835-1910), and D.H. Lawrence (1885-1930), who found Franklin’s Puritan-like self-criticism to be inaccessible and improbable. Nevertheless, Franklin developed Puritan and Quaker influences into a message that mass audiences found instructive.

Franklin returned to writing his autobiography from 1788 to 1789, following his return from France in 1785 and his participation in the Constitutional Convention (May 25-September 17, 1787). Now in his eighties, Franklin in Part Three reflects on his life from 1730 through the late 1750s and highlights his involvement in politics, science, and publishing. At this time, Franklin also began to revise the already completed parts of The Autobiography manuscript.

Franklin as Publisher

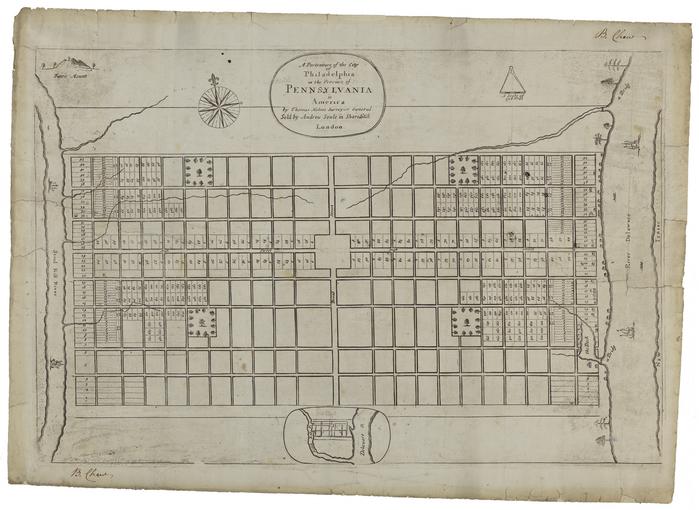

In Part Three, Franklin describes his continuing involvement in the publishing industry with Poor Richard’s Almanack , first published in 1732 and subsequently for the next twenty-five years. Franklin uses the almanac and his newspaper, The Pennsylvania Gazette, to achieve his goal of educating common people. Franklin becomes clerk of the General Assembly of Pennsylvania and then deputy postmaster of Philadelphia, which allows him to distribute his Gazette by mail. In 1753, Franklin is appointed postmaster general of America. Franklin also publishes influential pamphlets, such as Plain Truth (1747), which outlines the need for colonial unity, and Proposals Relating to the Education of Youth in Philadelphia (1749), which leads to the creation of the Academy of Philadelphia in 1751 (in 1791, renamed the University of Pennsylvania). Franklin’s political agenda also includes advocating for the education of women. In Part Three, Franklin speculates on creating a political “Party of Virtue,” whose members would subscribe to his thirteen virtues as well as a compilation of virtues distilled from various religions. He also recounts his activities in science and invention, including the invention of the stove in 1742 and the notable 1752 kite experiment, which concluded that lightning and electricity are, in fact, one and the same. Culminating two decades of publishing, political, and scientific, advancements, the Pennsylvania Assembly appoints Franklin to the role of commissioner to England in 1756.

Part Four, written between November 1789 and his death on April 17, 1790, briefly documents Franklin’s journey to London from 1757 to 1762, where he petitions the Penn family for financial assistance on behalf of the Pennsylvania Assembly. In 1762, after the Penn family agreed to provide financial assistance to Pennsylvania for events transpiring in the colony, such as the French and Indian War (1754-63), Franklin returns to Philadelphia. The brevity of Part Four reflects Franklin’s declining health.

Franklin’s autobiography has a complex publication history. After Franklin’s death in 1790, his grandson William Temple Franklin (1762-1823) served as his literary executor. However, without his approval, unauthorized excerpts of The Autobiography appeared in Philadelphia magazines, Universal Asylum and Columbian Magazine (May 1790-June 1791), and American Museum (July and November 1790). The text made its debut as a book in Paris in 1791 as a French translation of Franklin’s manuscript of Part One, subsequently translated into German and Swedish. An English translation of the French edition, titled The Private Life of the Late Benjamin Franklin , was published in London in 1793. By the next year, American editions based on the retranslated edition circulated in New York and Philadelphia. More than two decades passed before William Temple Franklin released his own edition, Memoirs of the Life and Writings of Benjamin Franklin , in 1818. Although this edition became viewed as the standard version, it remained flawed; based on an unrevised manuscript, it did not include Franklin’s revisions of the text or Franklin’s Part Four. In 1828 Part Four made its debut in Mémoires Sur La Vie De Benjamin Franklin , a Paris edition written in French.

A Resurgence in Popularity

Finally, in 1868, seventy-eight years after Franklin’s death, all four parts of Franklin’s Autobiography appeared in an edition produced by John Bigelow (1817-1911), an American author, journalist, and diplomat. This edition, titled Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin used Franklin’s final manuscript. The autobiography’s resurgence in the late nineteenth century mirrored the publication of “rags-to-riches” young adult novels by Horatio Alger Jr. (1832-99), in which impoverished boys rise through hard work and determination to lives of middle-class security and comfort. The life of Benjamin Franklin fits into this schema that became known as the “Horatio Alger Myth.”

The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin has served as source material for Franklin’s many biographers and continues to be republished in various forms, including digital e-books and audiobooks. The manuscript of Franklin’s autobiography was made available digitally through the Huntington Digital Library. An accessible text, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin continues to be read widely by students and scholars in the twenty-first century.

Rachel Lewis is enrolled in the Rutgers University-Camden Graduate School, where she is pursuing her master’s degree in English and New Jersey Teacher Certification in secondary education of English. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2018, Rutgers University

Thomas Holme’s A Portraiture of the City of Philadelphia, 1683

Historical Society of Pennsylvania

On the 1683 map pictured here, High Street, or Market Street, runs horizontally through the center square of the Philadelphia grid and is denoted in fine script handwriting. In his Autobiography, Franklin recounted his first day in Philadelphia: “I walk’d up [Market] Street, gazing about, till near the Market House I met a Boy with Bread. I had many a Meal on Bread and inquiring where he got it, I went immediately to the Baker’s he directed me to in Second Street; and ask’d for Biscuit, intending such as we had in Boston, but they it seems were not made in Philadelphia.” Franklin’s first walk through the city took him west on Market Street to Fourth Street, then to Chestnut Street and Walnut Street, and “coming round found [himself] again at Market Street Wharf,” where his boat was docked.

Poor Richard's Almanack, 1733

In December 1732, under the pseudonym Richard Saunders or “Poor Richard,” Benjamin Franklin published the first installment of Poor Richard’s Almanack. Each edition of Poor Richard typically included information regarding the calendar, the weather, local court dates, and astrological movements, in addition to Poor Richard’s “witticisms.” This photograph depicts the “Third Impression” of Poor Richard’s, the January 1733 edition in which Franklin first published the saying, “He that lies down with Dogs, shall rise up with fleas.” Poor Richard’s became a very profitable enterprise for Franklin and continued to be published continuously for twenty-five years, selling an average of 10,000 copies annually. Franklin used the almanac and his newspaper, The Pennsylvania Gazette, to achieve his goal of educating common people.

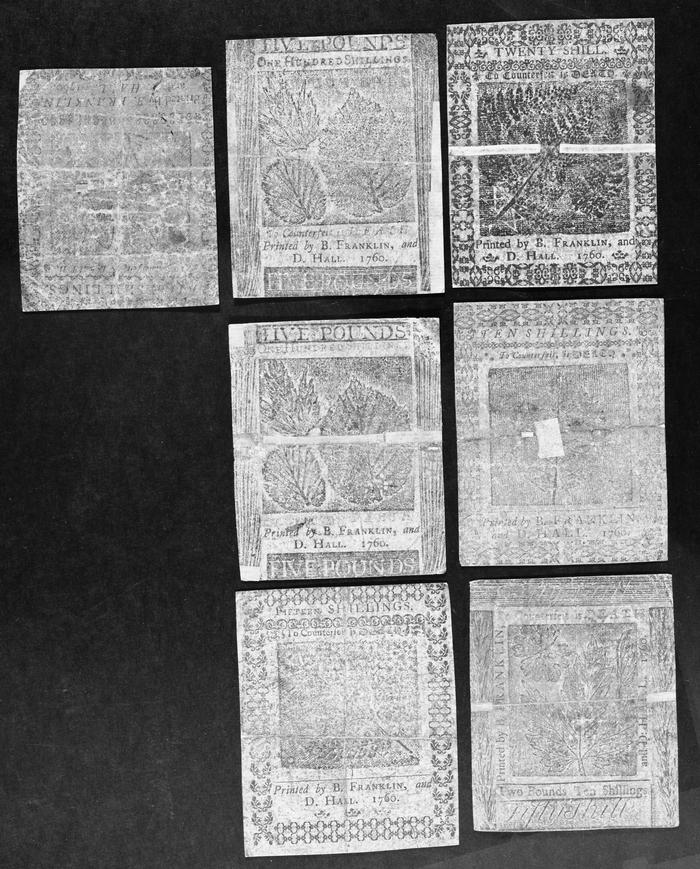

Various Notes Printed by Benjamin Franklin, 1760

Pennsylvania first began using paper currency in 1723, after two acts approved in 1723 and 1726 by the Pennsylvania governor, Sir William Keith (1669-1749). As a contentious issue, concern about paper currency circulated among members of Benjamin Franklin’s conversation group, the Junto. On April 3, 1729, Franklin anonymously published a pamphlet titled “A Modest Inquiry into the Nature and Necessity of a Paper Currency,” arguing in favor of paper currency as a mode to successfully conduct business and trade. Franklin’s support of paper currency also permeated his work as a printer: in 1731 he printed money for the Pennsylvania Assembly, and he did the same for other colonies, including Delaware and New Jersey. Franklin also pioneered anti-counterfeiting techniques by printing images of leaves onto paper money, making it difficult to replicate. Pictured here is an example of Franklin’s technique on notes printed in 1760.

Franklin continued to have a presence on American currency in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. His portrait has been on $100 Federal Reserve notes since they were first issued in 1914. Most United States currency features portraits of former United States presidents, but Franklin’s $100 note and the $10 bill featuring Alexander Hamilton (1757-1804) are exceptions. The back of Franklin’s $100 bill portrays Philadelphia’s Independence Hall.

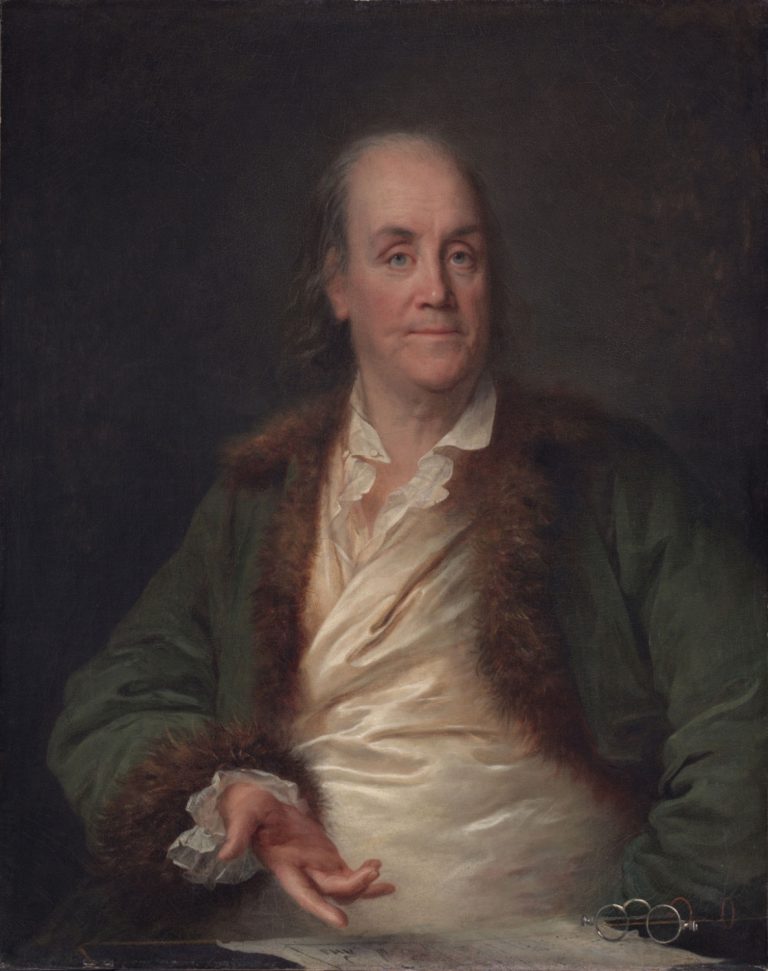

Portrait of Benjamin Franklin, 1778-79

Philadelphia Museum of Art

While Franklin lived in France, the artist Anne-Rosalie Bocquet Filleul (1752-94) painted this portrait depicting Franklin in his early seventies, gesturing toward a piece of paper accompanied by a pair of bifocals. In 1779 Louis Jacques Cathelin (1738-1804) made an engraving of Filleul’s painting and labeled the map on the table “Philadelphia.”

Franklin's Return to Philadelphia, 1785

Library of Congress

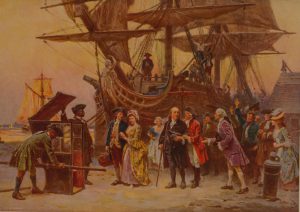

Benjamin Franklin began writing Part Two of his Autobiography in 1784 while living abroad in France. After the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the Continental Congress sent Franklin to join Silas Deane (1738-89) to seek political and financial support from France for the American struggle for independence. Later Franklin and Deane, joined by Arthur Lee (1740-92), a lawyer in London and American diplomat, negotiated the Treaty of Alliance and Treaty of Amity and Commerce with France, which were signed on February 6, 1778. Franklin was then elected minister plenipotentiary to France and the sole representative of America in France. Franklin lived in Passy, France, for nine years and returned to America in 1785, as depicted in this 1932 painting by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (1863-1930).

Following his return to Philadelphia from France, Franklin composed Part Three of the Autobiography during 1788-89, after he participated in the drafting and signing of the new U.S. Constitution. Franklin died April 17, 1790, five years after his return to Philadelphia.

Horatio Alger Jr.

The resurgence of Franklin’s Autobiography in the late nineteenth century with the publication of the 1868 edition of Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin by John Bigelow (1817-1911) mirrored the popularity of the “rags to riches” young adult novels by Horatio Alger Jr. (1832-99). Alger told stories of the rise of impoverished boys to lives of middle-class security and comfort through hard work and determination. Ben the Luggage Boy, shown here, was published in 1867 as the fifth installment in the Ragged Dick Series. The book follows the story of Ben as he runs away from home and lives on the streets of New York City, where he finds work as a newsboy and as a “luggage boy.” Alger's young adult novels fed the "Horatio Alger Myth": a teenage boy works hard to escape poverty. The life of Benjamin Franklin fits into the schema of the Horatio Alger Myth.

The American ideal of upward mobility in Franklin’s autobiography was noted as early as 1783, when Benjamin Vaughan (1751-1835), a diplomat instrumental in the creation of the Treaty of Paris and a friend to Franklin, wrote to the author: “All that has happened to you, is connected with the detail of the manners and situation of a rising people.” Vaughan’s statement spoke not only to Franklin’s achievement as an individual but also to the milieu in which he wrote and his audience: people of a new nation searching for American identity and individual identities. Franklin has been dubbed the “first American” for his social mobility, and his ability to depict this ascension in his Autobiography made the rags-to-riches narrative widely accessible. Written in simple, often humorous language, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin became an exemplar of the “American Dream.”

The Benjamin Franklin National Memorial

Visit Philadelphia

Between 1906 and 1911 American sculptor James Earle Fraser (1876-1953) created the monumental sculpture of Benjamin Franklin that later became featured in the Benjamin Franklin National Memorial. The sculpture and the Franklin Institute’s Memorial Hall, designed by John Windrim (1866-1934), were designated as a national memorial by Congress on October 25, 1972. The 20-feet-tall sculpture weighs 30 tons and sits upon a pedestal of white Seravezza marble weighing 92 tons. Unlike other national memorials, the Benjamin Franklin National Memorial is not included in the National Register of Historic Places. Instead, it is administered by the National Park Service.

Samuel Vaughan Merrick (1801-70) and William H. Keating (1799-1844) founded the Franklin Institute of the State of Pennsylvania for the Promotion of the Mechanic Arts on February 5, 1824. At its inception, the Franklin Institute offered science and technology classes as well as significant K-12 child outreach to Philadelphians. The institute was so popular that a little over a year after its founding it needed a new home. Architect John Haviland (1792-1852) designed the building, and construction began in June 1825 on Seventh Street (later the site of the Phildelphia History Museum). In 1932, during the Great Depression, the Franklin Institute built a new building at Twentieth Street and the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. The reimagined Franklin Institute opened to the public on January 1, 1934, as one of the first museums in the country to offer a hands-on approach to the understanding of science and technology. The Franklin Institute charges an admission fee, but entrance to Memorial Hall is free for community members and tourists who wish to gaze upon the prodigious sculpture of Benjamin Franklin.

The Ghost House of Benjamin Franklin

Franklin lived in the home represented in this photograph throughout his time as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention until his death in 1790. Earlier, Franklin’s family, including his wife, Deborah (1708-74), and their daughter, Sarah Franklin Bache (l1743-1808) and her family, lived in the home beginning in 1763 while Franklin was in London. Sally and her family continued to live in the home after Deborah’s death in 1774.

Following Franklin’s death, Sarah and her family inherited the Franklin home, and beginning in 1794 they rented it to tenants. Then, the home became a boarding house, an academy, a coffee house, and a hotel. By 1812, the land had increased in value and the Bache heirs decided to tear down the house and rebuild the land with rental row houses. In 1948, Congress created Independence National Historical Park, which included the Franklin Court site. The complex including a “ghost structure,” designed by the firm Venturi, Rauch and Scott Brown, opened in 1976 as part of the United States Bicentennial celebration.

The ghost structure of steel beams traces the outline of Franklin’s home and print shop, as shown in this photograph. The structure is located adjacent to the Benjamin Franklin Museum, which opened on September 20, 2013, and has continued to teach visitors about the various roles Franklin played throughout his lifetime as a printer, scientist, and civic leader.

Related Topics

- Philadelphia and the World

- Philadelphia and the Nation

- Cradle of Liberty

Time Periods

- Colonial Era

- Nineteenth Century after 1854

- American Revolution Era

- Center City Philadelphia

- Book Publishing and Publishers

- Franklin Institute

- Library Company of Philadelphia

- Market Street

- Printing and Publishing

- Revolutionary Crisis (American Revolution)

Related Reading

Baker, Jennifer Jordan. “Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography and the Credibility of Personality.” Early American Literature, no. 3 (2000): 274-93.

Bobker, Danielle. “Intimate points: The Dash in The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin.” Papers On Language & Literature, no. 4 (2013): 415-43.

Effing, Mercé Mur. “The Origin and Development of Self-Help Literature in the United States: The Concept of Success and Happiness, an Overview.” Atlantis: Revista De La Asociación Española De Estudios Ingleses Y Norteamericanos 31, no. 2 (December 2009): 125-41.

Fichtelberg, Joseph. “The Complex Image: Text and Reader in the ‘Autobiography’ of Benjamin Franklin.” Early American Literature, no. 2 (1988): 202-16.

Forde, Steven. “Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography and the Education of America.” The American Political Science Review, no. 2 (1992): 357-68.

Franklin, Benjamin, and Joyce E. Chaplin. Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography: An Authoritative Text, Contexts, Criticism . New York: W.W. Norton, 2012.

Franklin, Benjamin, and Paul M. Zall. Franklin On Franklin . Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2000.

Seavey, Ormond. Becoming Benjamin Franklin: The Autobiography and the Life . University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1988.

Related Collections

- Miscellaneous Benjamin Franklin Collections American Philosophical Society 105 S. Fifth Street, Philadelphia.

- Benjamin Franklin Collection Princeton University Library Department of Rare Books and Special Collections Manuscripts Division 1 Washington Road, Princeton, N.J.

- The Papers of Benjamin Franklin https://www.yale.edu P.O. Box 208240, New Haven, Conn.

Related Places

- The American Philosophical Society

- Benjamin Franklin Museum

- The Library Company of Philadelphia

- University of Pennsylvania

- Benjamin Franklin (American Philosophical Society Library)

- The Benjamin Franklin Papers (The Library of Congress)

- Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. Edited by John Bigelow, 1868 (Hathi Trust Digital Library)

- The World of Benjamin Franklin (The Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. Handwritten by Author, 1771-1789 (Huntington Digital Library)

- Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. Edited by Frank Woodworth Pine, 2006 (Project Gutenberg)

- Histories of the University and Published Articles (University of Pennsylvania Archives and Records Center)

Connecting the Past with the Present, Building Community, Creating a Legacy

- Philadelphia

- In his own words

- Temple's Diary

- Fun & Games

The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin franklin, ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

- Project Gutenberg

- 73,567 free eBooks

- 18 by Benjamin Franklin

Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin by Benjamin Franklin

Read now or download (free!)

Similar books, about this ebook.

- Privacy policy

- About Project Gutenberg

- Terms of Use

- Contact Information

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

The autobiography of Benjamin Franklin : Benjamin Franklin

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

393 Previews

12 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

EPUB and PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by Tracey.Gutierres on July 26, 2010

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

History | June 2024

Benjamin Franklin Was the Nation’s First Newsman

Before he helped launch a revolution, Benjamin Franklin was colonial America’s leading editor and printer of novels, almanacs, soap wrappers, and everything in between

:focal(1600x1204:1601x1205)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/15/37/15372488-30c0-4d7b-8ae4-b902a92d1b1c/20240321_smithsonian_bfranklin_0208_copy.jpg)

Looming large on Philadelphia’s Broad Street, a ten-foot-high statue—a gift to the city from the Pennsylvania Freemasons—shows young Benjamin Franklin at his printing press.

By Adam Smyth

Author, The Book-Makers: A History of the Book in Eighteen Lives

Benjamin Franklin was, in his own words, “the youngest son of the youngest son for five Generations back.” Born to a Boston candlemaker who had emigrated from Ecton, England, Franklin became an American printer of national significance: the editor and publisher, at 23, of what became his nation’s most important newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette . An internationally lauded scientist of electricity, he broke through the frosty anteroom of London’s Royal Society—a colonial autodidact!—to become a celebrated fellow. A prolific humorist, he invented a tradition of wry, plain-speaking wit (among his pseudonyms: Margaret Aftercast and Ephraim Censorious).

He was the author of one of the only pre-19th-century American best sellers still read today (his Autobiography ). A Pennsylvanian politician and civic reformer of tireless energy. Founder of the Junto, a self-improvement society; of the Library Company of Philadelphia , the first subscription library in North America; of the American Philosophical Society; of the Union Fire Company; of the University of Pennsylvania. The author of essays on phonetic alphabets, demography, paper currency. A leader of resistance to the 1765 Stamp Act, which imposed taxes on colonial legal documents and printed materials, and, ultimately, to British colonial rule of America. Grand master of the Masons, Pennsylvania. The deputy postmaster general of North America and, eventually, postmaster general of the United States.

He was the ambassador to France . A famous Londoner; a famous Parisian; a famous Pennsylvanian. A celebrity in a time when that concept was only emerging. (Guests at his Fourth of July celebration in Paris, in 1778, stole cutlery as souvenirs.) One of the founding fathers who drafted and signed the Declaration of Independence. The inventor of the Franklin wood-burning stove, the lightning rod, bifocal glasses, a chair that converted into a stepladder, the glass armonica, a new kind of street lamp (with a funnel dispersing the smoke), a rocking chair with a fan, swimming fins, a flexible urinary catheter and a “long arm” for removing objects from high shelves.

The Book-Makers: A History of the Book in Eighteen Lives

From Wynkyn de Worde’s printing of 15th-century bestsellers to Nancy Cunard’s avant-garde pamphlets produced on her small press in Normandy, this is a celebration of the book with the people put back in.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cd/31/cd313424-e099-44a0-9029-319d98e98240/glasses.jpg)

Do you feel small? Don’t feel small. Franklin knew his faults as much as he cherished his fame: the absent husband away for his wife’s death; the man prone to jettisoning friends who ceased to be useful (former friend John Collins, too often drunk, was sent off to Barbados with a West India captain to work as a tutor: “I never heard of him after,” Franklin recalled); the public moralizer who refused to name the mother of his illegitimate son; the life punctuated by furious arguments and the obsession with public credit and reputation. And—in ways that are becoming increasingly apparent at the time of writing—a man who was actively complicit in the slave trade.

President John Adams hailed Franklin’s benefaction “to his country and mankind,” but described also his personal hypocrisy and vanity: “He has a passion for reputation and fame, as strong as you can imagine, and his time and thoughts are chiefly employed to obtain it.”

The medium Franklin moved in was ink: He waded in it, up to his neck. The printing trade was his start, the profession that made him. While Franklin grew up at a time when printing in colonial America was not yet established, the trade was coiled like a spring, and his timing was right; to a considerable extent, Franklin released it. The first printing press in the British colonies was not established until 1638, when locksmith Stephen Daye sailed from Cambridge, England, to Massachusetts, carrying a press in pieces. In 1722, when Franklin was 16, there were just four cities in Britain’s North American colonies with presses, and only eight printing shops in all: five in Boston and one each in Philadelphia, New York, and New London, Connecticut. The Boston News-Letter started its publication in 1704; it was the only newspaper in the colonies for the next 15 years.

For Franklin, it starts early. In 1717, having alarmed his Puritan father with talk of a life on the seas, 12-year-old Franklin is set up as an apprentice to his elder brother, James, a printer. His brother had served his own apprenticeship in London and returned to Boston to found and edit the New-England Courant , the fourth paper in the colonies (and the third in Boston). As apprentice, Benjamin Franklin does the grunt work—“I was employed to carry the papers through the streets to the customers”—but he is ambitious, and he’s resentful of being held in check by an elder brother. He writes pseudonymous letters under the name of Silence Dogood, a middle-aged widow who mocks aspects of colonial life. Franklin’s letters are a hit; when it’s known that Silence is widowed, men write in with proposals of marriage.

Franklin, who left school at 10, has a powerfully “bookish inclination,” as he would later put it. He feeds off scraps in his father’s “little library” and then whatever volumes he can find. “Often I sat up in my room reading the greatest part of the night, when the book was borrowed in the evening and to be returned early in the morning, lest it should be missed or wanted.” His youthful language and conception of the world are forged by Pilgrim’s Progress , Daniel Defoe, Cotton Mather and John Dryden’s translation of Plutarch’s Lives —that work of Greek and Roman biographies (such as Alexander the Great and Julius Caesar) conveying, to the young Franklin, the potential scope of a life.

In 1723, Franklin, squirming under his brother’s rule, flees the Boston print shop. He is illegally breaking the terms of his apprenticeship: He is on the run. Arriving disheveled and almost penniless in Philadelphia on October 6, he is bewildered and alone but seized also by the symbolism of a new start in this new place, Pennsylvania Colony having been founded just over 40 years before by William Penn. “I walked up the street, gazing about, till near the market house I met a boy with bread.” His future wife, Deborah, happens to see the down-at-heel 17-year-old and thinks he has “a most awkward ridiculous appearance.” Franklin—“forgetting Boston as much as I could”—finds printing work with English-born Samuel Keimer, a patchy printer who’d spent time in London’s Fleet Prison for debt before trying to start again in Philadelphia. Keimer is a bad poet, too, with a habit of composing verse directly in type, without recourse to pen and paper.

Franklin quickly decides that Keimer (“slovenly to extreme dirtiness” and an “odd fish”) knows “nothing of presswork”—that is, of working the press, in contrast to composing or ordering the metal type. Keimer’s hardware consists, in Franklin’s words, “of an old shattered press and one small, worn-out fount of English.” (“English” is a type size, the equivalent of 14 points on your computer, and, Franklin probably thought, unhelpfully large. “Font,” or occasionally “fount,” from the French fondre , to melt or cast, means a complete set of type, and the design it represents.)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/48/13/4813a69c-cc37-4e04-a104-2c68a5072d9a/microsoftteams-image.png)

Subscribe to Smithsonian magazine now for just $19.99

This article is a selection from the June 2024 issue of Smithsonian magazine

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/65/48/6548ef67-39ac-4b98-bef4-42cb848ddc71/1877_003_bd2010_copy.jpg)

Keimer asks Franklin to finish printing an elegy on a recently deceased young poet and printer’s assistant. This is the first work that Franklin prints in Philadelphia: not a book, but a fragile single leaf on the death of a young man with the impossibly poetic name of Aquila Rose. ( Aquila is Latin for “eagle.”) All known copies disappear by the early 19th century until 200 years later, when a book dealer finds a sheet in a scrapbook and sells it in 2017 to the University of Pennsylvania, where it now resides.

A pattern forms that will be repeated in Franklin’s early career. He vaults past the lesser talents he sees around him—he finds the two established Philadelphia printers “wretched,” Keimer “a mere compositor” and Andrew Bradford “very illiterate”—and catches the eyes of powerful men. Sir William Keith, governor of Pennsylvania, sees a young man of promising parts, and on his urging, Franklin sails to London to gain a printer’s education.

He arrives in London on December 24, 1724, to find Keith has failed to send the letters of support he promised. (“He wished to please everybody, and, having little to give, he gave expectations,” Franklin will later write of his would-be patron.)

Forced on by his ceaseless drive, and managing to hold at bay some if not all calls to the taverns, playhouses and brothels, Franklin secures work at two major London printers, where he learns quickly. At the print shop of Samuel Palmer, he sets the type for the third edition of William Wollaston’s The Religion of Nature Delineated , an early work of Deism that argues ethics can be implied from the natural world and need not depend on revealed religion.

But Franklin feels he could do better, and he writes “a little metaphysical piece” titled “A Dissertation on Liberty and Necessity, Pleasure and Pain,” arguing for the incompatibility of an omnipotent God and human free will. The pamphlet carries no note of author or place of publication. It’s bad: Palmer thinks it “abominable.” Franklin quickly regrets it, burning the copies he can find.

Franklin is being shaped by everything bookish. He borrows secondhand volumes about medicine and religion from “one Wilcox, a bookseller, whose shop was at the next door,” at the sign of the Green Dragon. He moves from Palmer’s print shop to John Watts’: a more prestigious establishment that doesn’t share the printing of single works with other printers. This means, as book historian Hazel Wilkinson notes, that a voracious autodidact like Franklin can read whole works as he prints them, peering closely at the copy and setting type.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/69/98/69985fde-2e00-47d3-ad1e-c60687e319f6/nmah-et2016-08019-2.jpg)

In the beer-soaked world of the printing apprentice in 18th-century London, Franklin is the abstemious “Water-American”: “My companion at the press drank every day a pint before breakfast, a pint at breakfast with his bread and cheese, a pint between breakfast and dinner, a pint at dinner, a pint in the afternoon about six o’clock, and another when he had done his day’s work.” Franklin thinks this a “detestable custom” and proposes what he calls “some reasonable alterations in their chapel [printing house] laws.” It’s easy to imagine how these rational proposals sound to the ears of Franklin’s fellow apprentices: He urges his peers to leave off their breakfast of “beer and bread and cheese” and to instead eat “hot water-gruel, sprinkled with pepper.” No, thank you!

Franklin, now full of what London can offer, his head eternally generating new schemes (like the establishment, rather implausibly, of a swimming school), sails back to Philadelphia, and within two years, in 1728, he sets up his own print shop in partnership with Hugh Meredith, in a narrow brick house on Market Street. Type arrives from London. Orders trickle and then flow. Three-quarters of William Sewel’s History of the Quakers were printed by Keimer, but Franklin printed the remaining 178 pages plus the title page for each copy. Understanding he has to conspicuously surpass (to the point of humiliating) his rival, Franklin throws everything he has at the printing of his sheets of Sewel’s History . Keimer has been inching his way through printing this book for three years. Franklin composes a sheet a day—which means four large pages—as Meredith works the press.

Franklin, realizing that building “character and credit” is crucial, not only works with irresistible force; he also makes sure his neighbors see this industry. He wears plain clothes and pushes a wheelbarrow full of paper through the streets to convey the impression of honest labor. He wants to be a walking emblem of industry. “I see him still at work when I go home from club,” an eminent neighbor says, “and he is at work again before his neighbors are out of bed.” Virtue is crucial, for Franklin, but so is the chatter about virtue.

The personalities who dominate the early years of Franklin’s printing are soon pushed to the fringes and finally expelled. His partner Hugh Meredith—in Franklin’s judgment, “no compositor, a poor pressman, and seldom sober”—agrees to leave the business for life as a farmer in North Carolina. Franklin pays him £30 and a new saddle. Through drive, intelligence, determination and a variety of low cunning, Franklin is established as the major printer in Philadelphia.

It’s 1730. Franklin is 24. His ambitions can now unfold.

The history of the book is typically organized around big volumes. Books like Johannes Gutenberg’s 1450s Bible, the earliest full-scale work printed from movable metal type on Royal paper measuring 24 by 17 inches per leaf; or the Biblia Polyglotta , printed at Christopher Plantin’s shop in Antwerp, Belgium, between 1568 and 1572, in eight folio volumes, with parallel texts in Hebrew, Greek, Syriac and Aramaic, and translations and commentary in Latin, a wonder of mise-en-page; or the great 17-volume statement of Enlightenment thought, the Encyclopédie of Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert; or the 435 hand-colored, life-size prints in John James Audubon’s Birds of America .

These titles are deeply unrepresentative of the texts that typically emerged from binders’ offices and printing chapels and that filled the stalls of booksellers and the pockets of readers. The flip side is the world of jobbing printing: the production of cheap, everyday, usually ephemeral texts, the torrent of non-book print that circulated in the world starting in the 1450s. And it still does today. Look around you: the takeaway menu; the supermarket receipt. Packaging is very easily the largest consumer of print in 2024.

Benjamin Franklin was sustained by just this kind of printing work. Since it was cheaper to import large books from London, American printing before about 1740 tended to concentrate on small books, pamphlets, government printing, sermons and ephemera. Franklin had his moments with big volumes. Most notable was his 1744 publication of Cicero’s Cato Major , a 44 B.C. essay on aging and death, translated by James Logan. Seventy-three copies survive today of a print run of 1,000, and it’s often held up with admiration as the best example of colonial printing: printed in Caslon type in black and red on either American-milled or Genoese paper, depending on the copy. Logan’s translation had been circulating in manuscript some years before, and Franklin actively pursued it—rightly perceiving the volume not as a source of financial profit (it wasn’t) but a means to acquire cultural capital in powerful, learned circles.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/26/69/2669f0ef-c57a-4def-ae6c-a2c46f6dcffd/twodocs.jpg)

Two years earlier, in 1742, Franklin had begun printing Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded , Samuel Richardson’s epistolary novel about 15-year-old maidservant Pamela Andrews and her attempts to fend off the unwanted advances of her wealthy employer, the enigmatically titled “Mr. B.” Pamela was a huge hit in London, but it took Franklin more than two years to complete. He sold it unstitched—folded, in sheets—for 6 shillings. But by the time Franklin’s edition was ready, the market was awash with cheap imported copies. The lesson he learned—and Franklin was all about lessons learned—was to avoid heavy investment in a single title.

Jobbing work meant printing many copies quickly, moving rapidly from order to order with no thought to posterity. Most of these items lack an imprint and were only ascribed to Franklin, or Franklin and Hall (that is, David Hall, Franklin’s business partner starting around 1748), by the meticulous study of account books and ledgers by Franklin’s pre-eminent bibliographer, C. William Miller. Jobbing commissions were frequent and not labor-intensive. In 1742, Franklin repeatedly suspended work on Pamela to print lottery tickets, licenses for peddlers and public houses, sheriff’s warrants, naval certificates, soap wrappers, medical cures, bookplates for libraries, 1,000 hat bills, Irish Society tickets, and thousands of advertisements.

If we could walk down Second Street, in Philadelphia, in the spring of 1757, past the former offices of Franklin’s rival Andrew Bradford, we might see one of the playbills Franklin and Hall printed for the visiting London Theater Company. (Of 4,300 copies, only two are known to survive today.) Or if in 1761 we turned up Market Street, we might notice, pasted on a lamppost or passing between hands, a copy of instructions for operating a watch printed by Franklin and Hall. One of the features of print that is most often invoked is its capacity to endure, but this was a world of transient texts: of print read, then dropped, or lost, or used to light pipes, or to stop mustard pots, or to wrap pies. Or, with modern toilet paper still awaiting its great movement—it came in 1857—as what the 17th-century English poet Alexander Brome referred to as “bum fodder.”

Franklin concentrated his attention on three kinds of printed text whose import and profit far exceeded Cicero’s Cato Major or Richardson’s Pamela . The first was paper money. Franklin printed money for the governments of Pennsylvania (from 1729 to 1764), New Jersey (1728-46) and Delaware (1734-60), producing nearly 2,500,000 individual paper bills, just a handful of which survive today in public collections.

Paper money was a polarizing issue—farmers and tradesmen liked it; the rich did not—and Franklin contributed to the political controversy by advocating for it in A Modest Enquiry Into the Nature and Necessity of a Paper Currency . Franklin also had some clever ideas about the printing process, and from 1739, the verso of his bills carried the impression of leaves to prevent counterfeits: Franklin placed a leaf on a piece of wet fabric and pressed this into smooth plaster, and used this negative impression as the mold for melted metal type. He had a capacity to see what was not there, and then to find it, or invent it. He devised and built a copper-plate press—“the first that had been seen in the country,” he later boasted—to produce these engravings.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/de/46/de46188d-1d06-48bf-9c8a-8a59ac047b81/currency.jpg)

Franklin’s second crucial kind of non-book printing was his newspaper, the Pennsylvania Gazette . The Gazette became the most popular paper in the colonies. The sum of 10 shillings bought you a year’s subscription—that’s about 2 pence for every weekly four-page issue—and subscribers grew from a feeble 90 to more than 1,500 in 1748. What is a newspaper at this moment in history? And what qualities did Franklin’s possess that marked it out for success? Franklin’s paper, like most other colonial newspapers, was printed on both sides of one small folio sheet, but it was a better object. As Franklin himself wrote, “Our first papers made a quite different appearance from any before in the province; a better type”—a mix of English, pica and long primer—“and better printed.”

But it was the quality of Franklin’s writing, too, that set the Gazette apart—“one of the first good effects of my having learnt a little to scribble.” Like other papers, Franklin’s Gazette included reports from foreign newspapers, but Franklin increased the local and colonial content, cut tiresome encyclopedia recyclings, and added instead a series of essays, either reprinted from English journals (the London Journal, Spectator or Tatler ), or written by Franklin’s friends or Franklin himself. There were more advertisements. In a way that seems unimaginable amid the information overload of the 21st century, news was often thin on the ground—if the Delaware River froze over and ships didn’t come in, the news was stuck in the ice, too—and Franklin became adept at improvising content, often through the composition of original writing or (greatest of all literary genres) fake reader letters.

The effect was to produce a set of juxtapositions that at first might seem unstable: European and domestic news next to excerpts from Xenophon or The Morals of Confucius ; bawdy anecdotes written by Franklin and inspired by Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron , next to letters from readers, many written by Franklin under pseudonyms; an important interview with Andrew Hamilton, speaker of Pennsylvania’s House of Representatives, in 1733, alongside mock news that crashes through our modern sense of acceptable limits but that proved hugely popular in its time. (“And sometime last week, we are informed, that one Piles a Fidler, with his wife, were overset in a canoe near Newtown Creek. The good man, ’tis said, prudently secured his fiddle, and let his wife go to the bottom.”) His paper ran the first American political cartoon in 1754 as part of an editorial titled “The Disunited State,” as well as jokes, satirical sketches, mocking accounts of the clergy, obituaries (Franklin’s inclusions did much to establish and popularize the form) and essays motivated by a growing sense of outrage at English rule (the dire conditions of English prisons, and the suffering endured by the Irish as a result of “their griping avaricious landlords”).

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/3e/13/3e13a04b-1522-4744-958f-ec3bf240d001/stove.jpg)

In his Autobiography , Franklin wrote, “I considered my newspaper, also, as another means of communicating instruction,” and this commitment played out in essays that often originated in his autodidacts’ club, the Junto. The Gazette was a newspaper, and Franklin an editor, increasingly convinced of the importance of the press as a means for what he called “Zeal for the Publick Good.” This meant the cultivation of informed, civic-minded leaders and represented a commitment that ultimately found expression in Franklin’s successful advocacy of American independence.

But one topic among the Gazette ’s noisy miscellanies is disturbing, if not unexpected, for a modern reader. This is the presence of advertisements for slaves, and Franklin’s role in these as a kind of broker. Recent work by historian Jordan E. Taylor has done much to uncover the intimate links between 18th-century American newspapers and the trans-Atlantic slave trade, articulated through both notices about runaway slaves, and—Taylor’s particular focus—through thousands of advertisements for slaves for sale that “empowered enslavers and strengthened the slave system.” In the 37 years that Franklin published the Gazette , his newspaper printed at least 277 advertisements offering at least 308 slaves for sale. (And these are conservative counts.)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/76/e4/76e494ab-45da-4f1f-b4fa-27ac6b6b939e/newspaper.jpg)

In the 1740s in particular, Franklin’s Gazette was the crucial site for these advertisements. On March 10, 1743, the Gazette ran an advertisement for “A Negro man 22 years of age, of uncommon strength and activity.” (Advertisements typically denude slaves of anything as individuating as character and use instead stark identity—categories such as wench, woman, lad, boy, fellow, man, girl or child, with few details save age, health, sex and skills.) The advertisement instructed: “Any person that wants such a one may see him by enquiring of the printer hereof.” That was the clause that typically signed off these advertisements, and it implicates absolutely the newspaper printer in this slave-trade economy. Franklin is here the middleman, linking buyers and sellers and oiling the wheels of a slave economy, the advertisements serving as informal proxies for the auction or merchant firm. In an “enquire of the printer” advertisement in the Gazette for 1733, Franklin offered a “very likely Negro woman aged about 30 years” with a son “aged about 6 years, who … will be sold with his mother, or by himself, as the buyer pleases.”

Franklin’s brother James had also advertised slaves in his New-England Courant . Learning from his brother’s example, Franklin was the first printer outside Boston to broker slaves regularly through his newspaper, and his commercial success (but moral failure) catalyzed similar advertisements in newspapers in New York City, Baltimore and Providence, Rhode Island. Franklin later in life was known as a vocal and influential abolitionist, but as Taylor notes, “For most of the 18th century, to be a newspaper printer was to be a slave trader.”

Yet another publication at the heart of Franklin’s success was his Poor Richard series of almanacs. In publishing almanacs, Franklin was following the scent of the best seller. Almanacs compressed the world into miniature form. They were cheap, small, eminently portable books that provided readers with monthly calendars; astrological and meteorological prognostications; details of fairs and journeys between towns; chronologies of history; medical advice; a “zodiacal body” anatomizing the influence of the planets on parts of the body; and more. Thomas Nashe in 1596 said selling almanacs was “readier money than ale and cakes.”

The first edition of Franklin’s Poor Richard was printed in 1732; it sold for 5 pence a copy—or 3 shillings and 6 pence for a dozen—and contained, as the title page declares, “The Lunations, Eclipses, Judgment of the Weather, Spring Tides, Planets Motions & mutual Aspects, Sun and Moon’s Rising and Setting, Length of Days, Time of High Water, Fairs, Courts, and observable Days.” It was a huge commercial hit—“vending annually near ten thousand,” according to Franklin, in a colony with a 1730s population of around 50,000, with “scarce any neighborhood in the province being without it.” The almanac was a perfect form for Franklin, with an inclusive sweep of contents and a particularly Franklinian combination of big sales with plain-talking humility.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/cb/84/cb840a3a-253d-4e8e-a551-81aef7b907ac/20240321_smithsonian_bfranklin_0037_copy.jpg)

Franklin used the cheapest of books to educate a vast reading public toward his idea of virtue. In the 26th and final edition of Poor Richard , for 1758, Franklin gathered about 100 aphorisms and wove them into the speech of “Father Abraham” (“a plain clean old man, with white locks”). This piece of writing, variously known as “Father Abraham’s Speech,” “The Way to Wealth” or “La Science du Bonhomme Richard,” is Franklin’s most widely reprinted text. Franklin himself was proudly aware of its influence. In the Autobiography, he wrote: “The piece, being universally approved, was copied in all the newspapers of the Continent; reprinted in Britain on a broadside, to be stuck up in houses; two translations were made of it in French, and great numbers bought by the clergy and gentry, to distribute gratis among their poor parishioners and tenants.”

In it, Franklin reports how he overheard one Father Abraham (invented by Franklin) dispensing wisdom he had gathered from reading Poor Richard almanacs (written by Franklin):

Sloth, by bringing on diseases, absolutely shortens life. ‘Sloth, like rust, consumes faster than labor wears, while the used key is always bright,’ as Poor Richard says. ‘But dost thou love life, then do not squander time, for that’s the stuff life is made of,’ as Poor Richard says. How much more than is necessary do we spend in sleep! forgetting that ‘The sleeping fox catches no poultry, and that there will be sleeping enough in the grave,’ as Poor Richard says.

The collective wisdom was the unsurprising philosophy that hard work, thrift and moderation produced both material comforts and spiritual salvation.

Franklin’s immersion in book culture was so complete that he repeatedly imagined his life, and even his physical self, as a printed book. As a young man in 1728, Franklin composed his own epitaph, which—eternal self-promoter that he was, even in the image of death—he was fond of copying out for friends:

The Body of B. Franklin, Printer; Like the Cover of an old Book, Its Contents torn out, And stript of its Lettering and Gilding, Lies here, Food for Worms. But the Work shall not be wholly lost: For it will, as he believ’d, appear once more, In a new & more perfect Edition, Corrected and Amended By the Author. He was born January 6, 1706. Died 17—

His actual gravestone, which he shares with his wife, reads simply: BENJAMIN AND DEBORAH FRANKLIN 1790.

Adapted from The Book-Makers: A History of the Book in Eighteen Lives by Adam Smyth. Copyright © 2024. Reprinted by permission of Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books LLC., a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. New York, NY, U.S.A. All rights reserved.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Click to visit our Privacy Statement .

A Note to our Readers Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.

Adam Smyth | READ MORE

Adam Smyth, an English professor at Oxford, is the author of The Book-Makers .

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin is the traditional name for the unfinished record of his own life written by Benjamin Franklin from 1771 to 1790; however, Franklin appears to have called the work his Memoirs.Although it had a tortuous publication history after Franklin's death, this work has become one of the most famous and influential examples of an autobiography ever written.

Benjamin Franklin's Autobiography is both an important historical document and Franklin's major literary work. It was not only the first autobiography to achieve widespread popularity, but after two hundred years remains one of the most enduringly popular examples of the genre ever written. As such, it provides not only the story of Franklin ...

The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin begins with an explanation, addressed to Franklin 's son, William Franklin, concerning why Franklin has undertaken to write his life history.He says it may be useful to his posterity (offspring) but also he hopes to gratify his own vanity. He goes on to describe some of his relations, including his grandfather, Thomas Franklin Sr., and his father ...

Indeed, the Autobiography just begins to hint of ' the astonishing triumphs in store for Franklin before his death. Long before his years of public service were over he had been referred to in Parliament as one of the wisest men of Europe, and had been courted by kings. During his 1764-1775 term as colonial agent in England, Franklin was ...

Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin (The) By Rachel Lewis. Over eighteen years, from 1771 until his death, Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) composed an unfinished record of his life's tribulations and successes. Written in simple, often humorous language, The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin offered readers in the new United States an accessible ...

John was bred a dyer, I believe of woolens. Benjamin was bred a silk dyer, serving an apprenticeship at London. - 3 - He was an ingenious man. I remember him well, for when I was a boy he came over to my father in Boston, and lived in the house with us some years. He lived to a great age. His grandson, Samuel Franklin, now lives in Boston.

The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. Part One Pages 1-34. Part Two Pages 35-42. Part Three Pages 43-79. Part Four Pages 80-81. Tweet. This public domain content is presented by the Independence Hall Association, a nonprofit organization in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, founded in 1942. Publishing electronically as ushistory.org.

Page. Portrait of Franklin. vii. Pages 1 and 4 of The Pennsylvania Gazette, Number XL, the first number after Franklin took control. xxi. First page of The New England Courant of December 4-11, 1721. 33 "I was employed to carry the papers thro' the streets to the customers" 36 "She, standing at the door, saw me, and thought I made, as I certainly did, a most awkward, ridiculous appearance"

The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentlemen by Laurence Sterne can be seen as a related work as, though fiction, it parodies both the narrative of self-improvement and the writing style of the gentlemen memoirists (like Franklin) of the day. The Confessions of Jean Jacques Rousseau are also particularly linked with Franklin's Autobiography in that they provide the life history of a ...

Share Cite. Benjamin Franklin says that the purpose of The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin is to tell his son about his life, but also to give guidance to his future generations. Franklin ...

Benjamin Franklin was born in Milk Street, Boston, on January 6, 1706. His father, Josiah Franklin, was a tallow chandler who married twice, and of his seventeen children Benjamin was the youngest son. His schooling ended at ten, and at twelve he was bound apprentice to his brother James, a printer, who published the "New England Courant."

Franklin, Benjamin, 1706-1790: Editor: Eliot, Charles William, 1834-1926: Title: The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin Note: See also PG#20203 Ed: Frank Woodworth Pine and Illustrated by E. Boyd Smith Language: English: LoC Class: E300: History: America: Revolution to the Civil War (1783-1861) Subject: Franklin, Benjamin, 1706-1790 Subject

PENN/University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005 - Biography & Autobiography - 180 pages. Printer and publisher, author and educator, scientist and inventor, statesman and philanthropist, Benjamin Franklin was the very embodiment of the American type of self-made man. In 1771, at the age of 65, he sat down to write his autobiography, "having emerged ...

Analysis. Benjamin Franklin begins writing Part One of his Autobiography in 1771 at the age of 65 while on a country vacation in England in the town of Twyford. In the opening pages, he addresses his son, William, the Royal Governor of New Jersey, telling him that he, Benjamin, has always taken pleasure in hearing stories about his family ...

Several manuscripts related to the creation of Franklin's Autobiography are held by the Library of Congress's Manuscript Division.These include the Le Veillard Translation of the manuscript into French; copies of Franklin's outline for his memoir in the handwriting of Thomas Jefferson's secretary William Short, and of Franklin's grandson William Temple Franklin; and, printing-related notes and ...

72 A UTOBIOGRAPHY OF BENJAMIN FRANKLIN. 73 my mind with regard to my principles and morals, that you may see how far those influenced the future events of my life. My parents had early given me religious impressions and brought me through my childhood piously in the Dissenting way. But I was scarce fifteen when, after doubting by turns several ...

Benjamin Franklin / His Autobiography / 1706-1757 / TWYFORD, at the Bishop of St. Asaph's,[0] 1771. / The country-seat of Bishop Shipley, the good bishop, as Dr. Franklin used to

Analysis. The first letter Franklin includes to show why he is continuing his Autobiography is from a man named Abel James who wrote to Franklin while Franklin was in Paris. James says he has wanted to write Franklin for some time but feared the letter might fall into the hands of the British. There is an obvious shift, between Part One and Two ...

Title. Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin. Note. See also PG #148 ed. by Charles W. Eliot. Credits. Produced by Turgut Dincer, Brian Sogard and the Online.

The autobiography of Benjamin Franklin : Benjamin Franklin by Franklin, Benjamin, 1706-1790. Publication date 1940-Topics Franklin, Benjamin, 1706-1790 Publisher New York : Books, Inc Collection printdisabled; internetarchivebooks; inlibrary Contributor Internet Archive Language English.

Benjamin Franklin was, in his own words, "the youngest son of the youngest son for five Generations back." Born to a Boston candlemaker who had emigrated from Ecton, England, Franklin became ...