A Step-by-Step Guide To Case Discussion

By ashi jain.

Join InsideIIM GOLD

Webinars & Workshops

- Compare B-Schools

- Free CAT Course

Take Free Mock Tests

Upskill With AltUni

CAT Study Planner

Are you comfortable in Decision Making in a given situation How aptly you analyze the situation with a logical approach How much time do you take in arriving at a decision How good are you in taking the rightful course of action

Solved Example:

Hari, the only working member of the family has been working an organization for 25 years. His job required long standing hours. One day, while working, he lost his leg in an accident. The company paid for his medical reimbursement.

Since he was a hardworking employee; the company offered him another compensatory job. He refused by saying, ‘Once a Lion, always a Lion’. As an HR, what solution would you suggest?

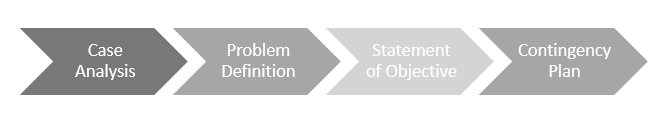

Identification of the Problem:

Obvious: accident, refusal of job, only earning member, his attitude, and inability to do his current job Hidden: the reputation of the company at stake, the course of action might influence other employees

Action Plan:

As an HR, you are first expected to check the company records and find out how a similar case has been dealt with in the past. Second, you need to take cognizance of the track record of the employee highlighted by the keyword ‘hardworking’.

Given the situation at hand, he is deemed unfit for his current role. However, the problem arises because of his attitude towards the compensatory job. Hence, in such a case, counselling is required.

Here, three levels of Counselling is required: 1. Ist level is with Hari 2. IInd level of counselling is required with the Union Leader (if any) to keep the collective interest and the reputation of the company in mind 3. IIIrd level of counselling is required with his family members as they constitute of the afflicted party

If the counselling does not work, one should also identify a contingency plan or Plan B. In this case, the Contingency Plan would be – hire someone from his family for a compensatory role.

Note that the following options are out of scope and should be avoided: 1. Increase Hari’s salary so that he gives in and agrees to do the compensatory job 2. Status Quo – do not bother as long as the Company is making a profit 3. Replace Hari with someone else

1. Pinpoint the key issues to be solved and identify their cause and effects

2. Start broad and try to work through a range of issues methodically

3. Connect the facts and evidence and focus on the big picture

4. Discuss any trade-offs or implications of your proposed solution

5. Relate your conclusion back to the problem statement and make sure you have answered all the questions

1. Do not be anxious if you are not able to understand the situation well or unable to justify the problem. Read again, a little slowly, it will help you understand better.

2. Do not jump to conclusions; try to move systematically and gradually.

3. Do not panic if you are unable to analyze the situation. Listen carefully to others as the discussion starts, it will help you gauge the problem at hand.

All the best! Ace the GDPI season.

Related Tags

Strategies for CAT 2024 Prep: Insights from CAT 99.95 Percentiler | Arjjan W., IIM A' 26

Mini Mock Test

CUET-PG Mini Mock 2 (By TISS Mumbai HRM&LR)

CUET-PG Mini Mock 3 (By TISS Mumbai HRM&LR)

CUET-PG Mini Mock 1 (By TISS Mumbai HRM&LR)

MBA Admissions 2024 - WAT 1

SNAP Quantitative Skills

SNAP Quant - 1

SNAP VARC Mini Mock - 1

SNAP Quant Mini Mock - 2

SNAP DILR Mini Mock - 4

SNAP VARC Mini Mock - 2

SNAP Quant Mini Mock - 4

SNAP LR Mini Mock - 3

SNAP Quant Mini Mock - 3

SNAP VARC Mini Mock - 3

SNAP - Quant Mini Mock 5

XAT Decision Making 2020

XAT Decision Making 2019

XAT Decision Making 2018

XAT Decision Making -10

XAT Decision Making -11

XAT Decision Making - 12

XAT Decision Making - 13

XAT Decision Making - 14

XAT Decision Making - 15

XAT Decision Making - 16

XAT Decision Making - 17

XAT Decision Making 2021

LR Topic Test

DI Topic Test

ParaSummary Topic Test

Take Free Test Here

Life of indian mba students in milan, italy - what’s next.

By InsideIIM Career Services

IMI Delhi: Worth It? | MBA ROI, Fees, Selection Process, Campus Life & More | KYC

How to calculate the real cost of an mba in 2024 ft. imt nagpur professors, mahindra university mba: worth it | campus life, academics, courses, placement | know your campus, how to uncover the reality of b-schools before joining, ft. masters' union, gmat focus edition: syllabus, exam pattern, scoring system, selection & more | new gmat exam, how to crack the jsw challenge 2023: insider tips and live q&a with industry leaders, why an xlri jamshedpur & fms delhi graduate decided to join the pharma industry, subscribe to our newsletter.

For a daily dose of the hottest, most insightful content created just for you! And don't worry - we won't spam you.

Who Are You?

Top B-Schools

Write a Story

InsideIIM Gold

InsideIIM.com is India's largest community of India's top talent that pursues or aspires to pursue a career in Management.

Follow Us Here

Konversations By InsideIIM

TestPrep By InsideIIM

- NMAT by GMAC

- Score Vs Percentile

- Exam Preparation

- Explainer Concepts

- Free Mock Tests

- RTI Data Analysis

- Selection Criteria

- CAT Toppers Interview

- Study Planner

- Admission Statistics

- Interview Experiences

- Explore B-Schools

- B-School Rankings

- Life In A B-School

- B-School Placements

- Certificate Programs

- Katalyst Programs

Placement Preparation

- Summer Placements Guide

- Final Placements Guide

Career Guide

- Career Explorer

- The Top 0.5% League

- Konversations Cafe

- The AltUni Career Show

- Employer Rankings

- Alumni Reports

- Salary Reports

Copyright 2024 - Kira9 Edumedia Pvt Ltd. All rights reserved.

Facilitating a Case Discussion

Have a plan, but be ready to adjust it

Enter each case discussion with a plan that includes the major topics you hope to cover (with rough time estimates) and the questions you hope to ask for each topic. Be as flexible as you can about how and when the topics are covered, and allow the participants to drive the discussion.

Ask Good Questions

Strive to make your questions interesting (a good measure is your own interest in the answer), clear, and as concise as possible. Emphasize questions that require judgment and analysis rather than purely factual responses. You want as many students as possible to be engaged and interested in joining the discussion. Vary your question types and style to avoid being predictable and keep students engaged.

When calling on students, consider three strategies: an open call , where you call on volunteers; a warm call , where you provide advance notice to a student before or during class before calling on them; and a cold call , where you call on them without any prior warning and when they did not volunteer. If you choose to allow students to speak without raising their hands, be careful to monitor the impact on the distribution of who speaks when—those comfortable speaking out may not be representative of all of your students.

Listen Attentively and Monitor Airtime

If you want students to be engaged and listen to each other, you must also be sure to listen well yourself. Use what you hear to drive your follow-up questions and the next student you call on. As the facilitator, you need to balance the opportunities to speak in class as well as the amount of “airtime” each student gets. The airtime need not be equal in each class session, but track this over time to keep it in balance.

Allow Space to Adjust

Your teaching plan will include several key themes to cover. As you consider transitions, ask yourself a few key questions: Have you covered the key issues in the discussion? What remains to be covered? Is it imperative to cover that material today rather than in a subsequent class?

Incorporate Group Work

Small groups in and outside class can elevate the discussions and increase student engagement. Having teams prepare cases together gives students an opportunity to test ideas and lower the preparation burden. Within class, small groups can accelerate analysis, fill in gaps in preparation, and set up debates. Be sure to give groups clear instructions, and make use of any deliverables they create.

Embrace the Open-Ended

Most students will crave clear answers at the end of each case discussion. Be wary of sharing prefabricated slides with conclusions, and rely more on students to provide the lessons. Call on students to share their thoughts (these can be warm calls at the start of class), have small groups generate their takeaways, or leave students with a question to ponder rather than answers to write down. Vary how you wrap up each class to stay unpredictable.

The Art of Cold Calling

The Perfect Opening Question

Questions for Class Discussion

What to Do When Students Bring Case Solutions to Class

More Key Topics

Getting Started with Case Teaching

Key considerations as you begin your case teaching journey

Teaching Cases in Hybrid Settings

How to balance the needs of both your in-person and remote students

Selecting Cases to Use in Your Classes

Find the right materials to achieve your learning goals

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

- Utility Menu

GA4 tagging code

- Demonstrating Moves Live

- Raw Clips Library

- Facilitation Guide

Structuring the Case Discussion

Well-designed cases are intentionally complex. Therefore, presenting an entire case to students all at once has the potential to overwhelm student groups and lead them to overlook key details or analytic steps. Accordingly, Barbara Cockrill asks students to review key case concepts the night before, and then presents the case in digestible “chunks” during a CBCL session. Structuring the case discussion around key in-depth questions, Cockrill creates a thoughtful interplay between small group work and whole group discussion that makes for more systematic forays into the case at hand.

Barbara Cockrill , Harold Amos Academy Associate Professor of Medicine

Student Group

Harvard Medical School

Homeostasis I

40 students

Additional Details

First-year requisite

- Classroom Considerations

- Relevant Research

- Related Resources

- CBCL provides students the opportunity to apply course material in new ways. For this reason, you might consider not sharing the case with students beforehand and having them experience it in class with fresh eyes.

- Chunk cases so students can focus on case specifics and gradually build-up to greater complexity and understanding.

- Introduce variety into case-based discussions. Integrate a mix of independent work, small group discussion, and whole group share outs to keep students engaged and provide multiple junctures for students to get feedback on their understanding.

- Instructor scaffolding is critical for effective case-based learning ( Ramaekers et al., 2011 )

- This resource from the Harvard Business School provides suggestions for questioning, listening, and responding during a case discussion .

- This comprehensive resource on “The ABCs of Case Teaching” provides helpful tips for planning and “running” your case .

Related Moves

Experiencing the Case as a Student Team

Regulating the Flow of Energy in the Classroom

Designing Focused Discussions for Relevance and Transfer of Knowledge

- Utility Menu

GA4 Tracking Code

bok_logo_2-02_-_harvard_left.png

Case Study At-A-Glance

A case study is a way to let students interact with material in an open-ended manner. the goal is not to find solutions, but to explore possibilities and options of a real-life scenario..

Want examples of a Case-Study? Check out the ABLConnect Activity Database Want to read research supporting the Case-Study method? Click here

Why should you facilitate a Case Study?

Want to facilitate a case-study in your class .

How-To Run a Case-Study

- Before class pick the case study topic/scenario. You can either generate a fictional situation or can use a real-world example.

- Clearly let students know how they should prepare. Will the information be given to them in class or do they need to do readings/research before coming to class?

- Have a list of questions prepared to help guide discussion (see below)

- Sessions work best when the group size is between 5-20 people so that everyone has an opportunity to participate. You may choose to have one large whole-class discussion or break into sub-groups and have smaller discussions. If you break into groups, make sure to leave extra time at the end to bring the whole class back together to discuss the key points from each group and to highlight any differences.

- What is the problem?

- What is the cause of the problem?

- Who are the key players in the situation? What is their position?

- What are the relevant data?

- What are possible solutions – both short-term and long-term?

- What are alternate solutions? – Play (or have the students play) Devil’s Advocate and consider alternate view points

- What are potential outcomes of each solution?

- What other information do you want to see?

- What can we learn from the scenario?

- Be flexible. While you may have a set of questions prepared, don’t be afraid to go where the discussion naturally takes you. However, be conscious of time and re-focus the group if key points are being missed

- Role-playing can be an effective strategy to showcase alternate viewpoints and resolve any conflicts

- Involve as many students as possible. Teamwork and communication are key aspects of this exercise. If needed, call on students who haven’t spoken yet or instigate another rule to encourage participation.

- Write out key facts on the board for reference. It is also helpful to write out possible solutions and list the pros/cons discussed.

- Having the information written out makes it easier for students to reference during the discussion and helps maintain everyone on the same page.

- Keep an eye on the clock and make sure students are moving through the scenario at a reasonable pace. If needed, prompt students with guided questions to help them move faster.

- Either give or have the students give a concluding statement that highlights the goals and key points from the discussion. Make sure to compare and contrast alternate viewpoints that came up during the discussion and emphasize the take-home messages that can be applied to future situations.

- Inform students (either individually or the group) how they did during the case study. What worked? What didn’t work? Did everyone participate equally?

- Taking time to reflect on the process is just as important to emphasize and help students learn the importance of teamwork and communication.

CLICK HERE FOR A PRINTER FRIENDLY VERSION

Other Sources:

Harvard Business School: Teaching By the Case-Study Method

Written by Catherine Weiner

Search form

- Table of Contents

- Troubleshooting Guide

- A Model for Getting Started

- Justice Action Toolkit

- Best Change Processes

- Databases of Best Practices

- Online Courses

- Ask an Advisor

- Subscribe to eNewsletter

- Community Stories

- YouTube Channel

- About the Tool Box

- How to Use the Tool Box

- Privacy Statement

- Workstation/Check Box Sign-In

- Online Training Courses

- Capacity Building Training

- Training Curriculum - Order Now

- Community Check Box Evaluation System

- Build Your Toolbox

- Facilitation of Community Processes

- Community Health Assessment and Planning

- Section 4. Techniques for Leading Group Discussions

Chapter 16 Sections

- Section 1. Conducting Effective Meetings

- Section 2. Developing Facilitation Skills

- Section 3. Capturing What People Say: Tips for Recording a Meeting

- Main Section

A local coalition forms a task force to address the rising HIV rate among teens in the community. A group of parents meets to wrestle with their feeling that their school district is shortchanging its students. A college class in human services approaches the topic of dealing with reluctant participants. Members of an environmental group attend a workshop on the effects of global warming. A politician convenes a “town hall meeting” of constituents to brainstorm ideas for the economic development of the region. A community health educator facilitates a smoking cessation support group.

All of these might be examples of group discussions, although they have different purposes, take place in different locations, and probably run in different ways. Group discussions are common in a democratic society, and, as a community builder, it’s more than likely that you have been and will continue to be involved in many of them. You also may be in a position to lead one, and that’s what this section is about. In this last section of a chapter on group facilitation, we’ll examine what it takes to lead a discussion group well, and how you can go about doing it.

What is an effective group discussion?

The literal definition of a group discussion is obvious: a critical conversation about a particular topic, or perhaps a range of topics, conducted in a group of a size that allows participation by all members. A group of two or three generally doesn’t need a leader to have a good discussion, but once the number reaches five or six, a leader or facilitator can often be helpful. When the group numbers eight or more, a leader or facilitator, whether formal or informal, is almost always helpful in ensuring an effective discussion.

A group discussion is a type of meeting, but it differs from the formal meetings in a number of ways: It may not have a specific goal – many group discussions are just that: a group kicking around ideas on a particular topic. That may lead to a goal ultimately...but it may not. It’s less formal, and may have no time constraints, or structured order, or agenda. Its leadership is usually less directive than that of a meeting. It emphasizes process (the consideration of ideas) over product (specific tasks to be accomplished within the confines of the meeting itself. Leading a discussion group is not the same as running a meeting. It’s much closer to acting as a facilitator, but not exactly the same as that either.

An effective group discussion generally has a number of elements:

- All members of the group have a chance to speak, expressing their own ideas and feelings freely, and to pursue and finish out their thoughts

- All members of the group can hear others’ ideas and feelings stated openly

- Group members can safely test out ideas that are not yet fully formed

- Group members can receive and respond to respectful but honest and constructive feedback. Feedback could be positive, negative, or merely clarifying or correcting factual questions or errors, but is in all cases delivered respectfully.

- A variety of points of view are put forward and discussed

- The discussion is not dominated by any one person

- Arguments, while they may be spirited, are based on the content of ideas and opinions, not on personalities

- Even in disagreement, there’s an understanding that the group is working together to resolve a dispute, solve a problem, create a plan, make a decision, find principles all can agree on, or come to a conclusion from which it can move on to further discussion

Many group discussions have no specific purpose except the exchange of ideas and opinions. Ultimately, an effective group discussion is one in which many different ideas and viewpoints are heard and considered. This allows the group to accomplish its purpose if it has one, or to establish a basis either for ongoing discussion or for further contact and collaboration among its members.

There are many possible purposes for a group discussion, such as:

- Create a new situation – form a coalition, start an initiative, etc.

- Explore cooperative or collaborative arrangements among groups or organizations

- Discuss and/or analyze an issue, with no specific goal in mind but understanding

- Create a strategic plan – for an initiative, an advocacy campaign, an intervention, etc.

- Discuss policy and policy change

- Air concerns and differences among individuals or groups

- Hold public hearings on proposed laws or regulations, development, etc.

- Decide on an action

- Provide mutual support

- Solve a problem

- Resolve a conflict

- Plan your work or an event

Possible leadership styles of a group discussion also vary. A group leader or facilitator might be directive or non-directive; that is, she might try to control what goes on to a large extent; or she might assume that the group should be in control, and that her job is to facilitate the process. In most group discussions, leaders who are relatively non-directive make for a more broad-ranging outlay of ideas, and a more satisfying experience for participants.

Directive leaders can be necessary in some situations. If a goal must be reached in a short time period, a directive leader might help to keep the group focused. If the situation is particularly difficult, a directive leader might be needed to keep control of the discussion and make

Why would you lead a group discussion?

There are two ways to look at this question: “What’s the point of group discussion?” and “Why would you, as opposed to someone else, lead a group discussion?” Let’s examine both.

What’s the point of group discussion?

As explained in the opening paragraphs of this section, group discussions are common in a democratic society. There are a number of reasons for this, some practical and some philosophical.

A group discussion:

- G ives everyone involved a voice . Whether the discussion is meant to form a basis for action, or just to play with ideas, it gives all members of the group a chance to speak their opinions, to agree or disagree with others, and to have their thoughts heard. In many community-building situations, the members of the group might be chosen specifically because they represent a cross-section of the community, or a diversity of points of view.

- Allows for a variety of ideas to be expressed and discussed . A group is much more likely to come to a good conclusion if a mix of ideas is on the table, and if all members have the opportunity to think about and respond to them.

- Is generally a democratic, egalitarian process . It reflects the ideals of most grassroots and community groups, and encourages a diversity of views.

- Leads to group ownership of whatever conclusions, plans, or action the group decides upon . Because everyone has a chance to contribute to the discussion and to be heard, the final result feels like it was arrived at by and belongs to everyone.

- Encourages those who might normally be reluctant to speak their minds . Often, quiet people have important things to contribute, but aren’t assertive enough to make themselves heard. A good group discussion will bring them out and support them.

- Can often open communication channels among people who might not communicate in any other way . People from very different backgrounds, from opposite ends of the political spectrum, from different cultures, who may, under most circumstances, either never make contact or never trust one another enough to try to communicate, might, in a group discussion, find more common ground than they expected.

- Is sometimes simply the obvious, or even the only, way to proceed. Several of the examples given at the beginning of the section – the group of parents concerned about their school system, for instance, or the college class – fall into this category, as do public hearings and similar gatherings.

Why would you specifically lead a group discussion?

You might choose to lead a group discussion, or you might find yourself drafted for the task. Some of the most common reasons that you might be in that situation:

- It’s part of your job . As a mental health counselor, a youth worker, a coalition coordinator, a teacher, the president of a board of directors, etc. you might be expected to lead group discussions regularly.

- You’ve been asked to . Because of your reputation for objectivity or integrity, because of your position in the community, or because of your skill at leading group discussions, you might be the obvious choice to lead a particular discussion.

- A discussion is necessary, and you’re the logical choice to lead it . If you’re the chair of a task force to address substance use in the community, for instance, it’s likely that you’ll be expected to conduct that task force’s meetings, and to lead discussion of the issue.

- It was your idea in the first place . The group discussion, or its purpose, was your idea, and the organization of the process falls to you.

You might find yourself in one of these situations if you fall into one of the categories of people who are often tapped to lead group discussions. These categories include (but aren’t limited to):

- Directors of organizations

- Public officials

- Coalition coordinators

- Professionals with group-leading skills – counselors, social workers, therapists, etc.

- Health professionals and health educators

- Respected community members. These folks may be respected for their leadership – president of the Rotary Club, spokesperson for an environmental movement – for their positions in the community – bank president, clergyman – or simply for their personal qualities – integrity, fairness, ability to communicate with all sectors of the community.

- Community activists. This category could include anyone from “professional” community organizers to average citizens who care about an issue or have an idea they want to pursue.

When might you lead a group discussion?

The need or desire for a group discussion might of course arise anytime, but there are some times when it’s particularly necessary.

- At the start of something new . Whether you’re designing an intervention, starting an initiative, creating a new program, building a coalition, or embarking on an advocacy or other campaign, inclusive discussion is likely to be crucial in generating the best possible plan, and creating community support for and ownership of it.

- When an issue can no longer be ignored . When youth violence reaches a critical point, when the community’s drinking water is declared unsafe, when the HIV infection rate climbs – these are times when groups need to convene to discuss the issue and develop action plans to swing the pendulum in the other direction.

- When groups need to be brought together . One way to deal with racial or ethnic hostility, for instance, is to convene groups made up of representatives of all the factions involved. The resulting discussions – and the opportunity for people from different backgrounds to make personal connections with one another – can go far to address everyone’s concerns, and to reduce tensions.

- When an existing group is considering its next step or seeking to address an issue of importance to it . The staff of a community service organization, for instance, may want to plan its work for the next few months, or to work out how to deal with people with particular quirks or problems.

How do you lead a group discussion?

In some cases, the opportunity to lead a group discussion can arise on the spur of the moment; in others, it’s a more formal arrangement, planned and expected. In the latter case, you may have the chance to choose a space and otherwise structure the situation. In less formal circumstances, you’ll have to make the best of existing conditions.

We’ll begin by looking at what you might consider if you have time to prepare. Then we’ll examine what it takes to make an effective discussion leader or facilitator, regardless of external circumstances.

Set the stage

If you have time to prepare beforehand, there are a number of things you may be able to do to make the participants more comfortable, and thus to make discussion easier.

Choose the space

If you have the luxury of choosing your space, you might look for someplace that’s comfortable and informal. Usually, that means comfortable furniture that can be moved around (so that, for instance, the group can form a circle, allowing everyone to see and hear everyone else easily). It may also mean a space away from the ordinary.

One organization often held discussions on the terrace of an old mill that had been turned into a bookstore and café. The sound of water from the mill stream rushing by put everyone at ease, and encouraged creative thought.

Provide food and drink

The ultimate comfort, and one that breaks down barriers among people, is that of eating and drinking.

Bring materials to help the discussion along

Most discussions are aided by the use of newsprint and markers to record ideas, for example.

Become familiar with the purpose and content of the discussion

If you have the opportunity, learn as much as possible about the topic under discussion. This is not meant to make you the expert, but rather to allow you to ask good questions that will help the group generate ideas.

Make sure everyone gets any necessary information, readings, or other material beforehand

If participants are asked to read something, consider questions, complete a task, or otherwise prepare for the discussion, make sure that the assignment is attended to and used. Don’t ask people to do something, and then ignore it.

Lead the discussion

Think about leadership style

The first thing you need to think about is leadership style, which we mentioned briefly earlier in the section. Are you a directive or non-directive leader? The chances are that, like most of us, you fall somewhere in between the extremes of the leader who sets the agenda and dominates the group completely, and the leader who essentially leads not at all. The point is made that many good group or meeting leaders are, in fact, facilitators, whose main concern is supporting and maintaining the process of the group’s work. This is particularly true when it comes to group discussion, where the process is, in fact, the purpose of the group’s coming together.

A good facilitator helps the group set rules for itself, makes sure that everyone participates and that no one dominates, encourages the development and expression of all ideas, including “odd” ones, and safeguards an open process, where there are no foregone conclusions and everyone’s ideas are respected. Facilitators are non-directive, and try to keep themselves out of the discussion, except to ask questions or make statements that advance it. For most group discussions, the facilitator role is probably a good ideal to strive for.

It’s important to think about what you’re most comfortable with philosophically, and how that fits what you’re comfortable with personally. If you’re committed to a non-directive style, but you tend to want to control everything in a situation, you may have to learn some new behaviors in order to act on your beliefs.

Put people at ease

Especially if most people in the group don’t know one another, it’s your job as leader to establish a comfortable atmosphere and set the tone for the discussion.

Help the group establish ground rules

The ground rules of a group discussion are the guidelines that help to keep the discussion on track, and prevent it from deteriorating into namecalling or simply argument. Some you might suggest, if the group has trouble coming up with the first one or two:

- Everyone should treat everyone else with respect : no name-calling, no emotional outbursts, no accusations.

- No arguments directed at people – only at ideas and opinions . Disagreement should be respectful – no ridicule.

- Don’t interrupt . Listen to the whole of others’ thoughts – actually listen, rather than just running over your own response in your head.

- Respect the group’s time . Try to keep your comments reasonably short and to the point, so that others have a chance to respond.

- Consider all comments seriously, and try to evaluate them fairly . Others’ ideas and comments may change your mind, or vice versa: it’s important to be open to that.

- Don’t be defensive if someone disagrees with you . Evaluate both positions, and only continue to argue for yours if you continue to believe it’s right.

- Everyone is responsible for following and upholding the ground rules .

Ground rules may also be a place to discuss recording the session. Who will take notes, record important points, questions for further discussion, areas of agreement or disagreement? If the recorder is a group member, the group and/or leader should come up with a strategy that allows her to participate fully in the discussion.

Generate an agenda or goals for the session

You might present an agenda for approval, and change it as the group requires, or you and the group can create one together. There may actually be no need for one, in that the goal may simply be to discuss an issue or idea. If that’s the case, it should be agreed upon at the outset.

How active you are might depend on your leadership style, but you definitely have some responsibilities here. They include setting, or helping the group to set the discussion topic; fostering the open process; involving all participants; asking questions or offering ideas to advance the discussion; summarizing or clarifying important points, arguments, and ideas; and wrapping up the session. Let’s look at these, as well as some do’s and don’t’s for discussion group leaders.

- Setting the topic . If the group is meeting to discuss a specific issue or to plan something, the discussion topic is already set. If the topic is unclear, then someone needs to help the group define it. The leader – through asking the right questions, defining the problem, and encouraging ideas from the group – can play that role.

- Fostering the open process . Nurturing the open process means paying attention to the process, content, and interpersonal dynamics of the discussion all at the same time – not a simple matter. As leader, your task is not to tell the group what to do, or to force particular conclusions, but rather to make sure that the group chooses an appropriate topic that meets its needs, that there are no “right” answers to start with (no foregone conclusions), that no one person or small group dominates the discussion, that everyone follows the ground rules, that discussion is civil and organized, and that all ideas are subjected to careful critical analysis. You might comment on the process of the discussion or on interpersonal issues when it seems helpful (“We all seem to be picking on John here – what’s going on?”), or make reference to the open process itself (“We seem to be assuming that we’re supposed to believe X – is that true?”). Most of your actions as leader should be in the service of modeling or furthering the open process.

Part of your job here is to protect “minority rights,” i.e., unpopular or unusual ideas. That doesn’t mean you have to agree with them, but that you have to make sure that they can be expressed, and that discussion of them is respectful, even in disagreement. (The exceptions are opinions or ideas that are discriminatory or downright false.) Odd ideas often turn out to be correct, and shouldn’t be stifled.

- Involving all participants . This is part of fostering the open process, but is important enough to deserve its own mention. To involve those who are less assertive or shy, or who simply can’t speak up quickly enough, you might ask directly for their opinion, encourage them with body language (smile when they say anything, lean and look toward them often), and be aware of when they want to speak and can’t break in. It’s important both for process and for the exchange of ideas that everyone have plenty of opportunity to communicate their thoughts.

- Asking questions or offering ideas to advance the discussion . The leader should be aware of the progress of the discussion, and should be able to ask questions or provide information or arguments that stimulate thinking or take the discussion to the next step when necessary. If participants are having trouble grappling with the topic, getting sidetracked by trivial issues, or simply running out of steam, it’s the leader’s job to carry the discussion forward.

This is especially true when the group is stuck, either because two opposing ideas or factions are at an impasse, or because no one is able or willing to say anything. In these circumstances, the leader’s ability to identify points of agreement, or to ask the question that will get discussion moving again is crucial to the group’s effectiveness.

- Summarizing or clarifying important points, arguments, or ideas . This task entails making sure that everyone understands a point that was just made, or the two sides of an argument. It can include restating a conclusion the group has reached, or clarifying a particular idea or point made by an individual (“What I think I heard you say was…”). The point is to make sure that everyone understands what the individual or group actually meant.

- Wrapping up the session . As the session ends, the leader should help the group review the discussion and make plans for next steps (more discussion sessions, action, involving other people or groups, etc.). He should also go over any assignments or tasks that were agreed to, make sure that every member knows what her responsibilities are, and review the deadlines for those responsibilities. Other wrap-up steps include getting feedback on the session – including suggestions for making it better – pointing out the group’s accomplishments, and thanking it for its work.

Even after you’ve wrapped up the discussion, you’re not necessarily through. If you’ve been the recorder, you might want to put the notes from the session in order, type them up, and send them to participants. The notes might also include a summary of conclusions that were reached, as well as any assignments or follow-up activities that were agreed on.

If the session was one-time, or was the last of a series, your job may now be done. If it was the beginning, however, or part of an ongoing discussion, you may have a lot to do before the next session, including contacting people to make sure they’ve done what they promised, and preparing the newsprint notes to be posted at the next session so everyone can remember the discussion.

Leading an effective group discussion takes preparation (if you have the opportunity for it), an understanding of and commitment to an open process, and a willingness to let go of your ego and biases. If you can do these things, the chances are you can become a discussion leader that can help groups achieve the results they want.

Do’s and don’ts for discussion leaders

- Model the behavior and attitudes you want group members to employ . That includes respecting all group members equally; advancing the open process; demonstrating what it means to be a learner (admitting when you’re wrong, or don’t know a fact or an answer, and suggesting ways to find out); asking questions based on others’ statements; focusing on positions rather than on the speaker; listening carefully; restating others’ points; supporting your arguments with fact or logic; acceding when someone else has a good point; accepting criticism; thinking critically; giving up the floor when appropriate; being inclusive and culturally sensitive, etc.

- Use encouraging body language and tone of voice, as well as words . Lean forward when people are talking, for example, keep your body position open and approachable, smile when appropriate, and attend carefully to everyone, not just to those who are most articulate.

- Give positive feedback for joining the discussion . Smile, repeat group members’ points, and otherwise show that you value participation.

- Be aware of people’s reactions and feelings, and try to respond appropriately . If a group member is hurt by others’ comments, seems puzzled or confused, is becoming angry or defensive, it’s up to you as discussion leader to use the ground rules or your own sensitivity to deal with the situation. If someone’s hurt, for instance, it may be important to point that out and discuss how to make arguments without getting personal. If group members are confused, revisiting the comments or points that caused the confusion, or restating them more clearly, may be helpful. Being aware of the reactions of individuals and of the group as a whole can make it possible to expose and use conflict, or to head off unnecessary emotional situations and misunderstandings.

- Ask open-ended questions . In advancing the discussion, use questions that can’t be answered with a simple yes or no. Instead, questions should require some thought from group members, and should ask for answers that include reasons or analysis. The difference between “Do you think the President’s decision was right?” and “Why do you think the President’s decision was or wasn’t right?” is huge. Where the first question can be answered with a yes or no, the second requires an analysis supporting the speaker’s opinion, as well as discussion of the context and reasons for the decision.

- Control your own biases . While you should point out factual errors or ideas that are inaccurate and disrespectful of others, an open process demands that you not impose your views on the group, and that you keep others from doing the same. Group members should be asked to make rational decisions about the positions or views they want to agree with, and ultimately the ideas that the group agrees on should be those that make the most sense to them – whether they coincide with yours or not. Pointing out bias – including your own – and discussing it helps both you and group members try to be objective.

A constant question that leaders – and members – of any group have is what to do about racist, sexist, or homophobic remarks, especially in a homogeneous group where most or all of the members except the leader may agree with them. There is no clear-cut answer, although if they pass unchallenged, it may appear you condone the attitude expressed. How you challenge prejudice is the real question. The ideal here is that other members of the group do the challenging, and it may be worth waiting long enough before you jump in to see if that’s going to happen. If it doesn’t, you can essentially say, “That’s wrong, and I won’t allow that kind of talk here,” which may well put an end to the remarks, but isn’t likely to change anyone’s mind. You can express your strong disagreement or discomfort with such remarks and leave it at that, or follow up with “Let’s talk about it after the group,” which could generate some real discussion about prejudice and stereotypes, and actually change some thinking over time. Your ground rules – the issue of respecting everyone – should address this issue, and it probably won’t come up…but there are no guarantees. It won’t hurt to think beforehand about how you want to handle it.

- Encourage disagreement, and help the group use it creatively . Disagreement is not to be smoothed over, but rather to be analyzed and used. When there are conflicting opinions – especially when both can be backed up by reasonable arguments – the real discussion starts. If everyone agrees on every point, there’s really no discussion at all. Disagreement makes people think. It may not be resolved in one session, or at all, but it’s the key to discussion that means something.

All too often, conflict – whether conflicting opinions, conflicting world views, or conflicting personalities – is so frightening to people that they do their best to ignore it or gloss it over. That reaction not only leaves the conflict unresolved – and therefore growing, so that it will be much stronger when it surfaces later– but fails to examine the issues that it raises. If those are brought out in the open and discussed reasonably, the two sides often find that they have as much agreement as disagreement, and can resolve their differences by putting their ideas together. Even where that’s not the case, facing the conflict reasonably, and looking at the roots of the ideas on each side, can help to focus on the issue at hand and provide solutions far better than if one side or the other simply operated alone.

- Keep your mouth shut as much as possible . By and large, discussion groups are for the group members. You may be a member of the group and have been asked by the others to act as leader, in which case you certainly have a right to be part of the discussion (although not to dominate). If you’re an outside facilitator, or leader by position, it’s best to confine your contributions to observations on process, statements of fact, questions to help propel the discussion, and clarification and summarization. The simple fact that you’re identified as leader or facilitator gives your comments more force than those of other group members. If you’re in a position of authority or seen as an expert, that force becomes even greater. The more active you are in the discussion, the more the group will take your positions and ideas as “right,” and the less it will come to its own conclusions.

- Don’t let one or a small group of individuals dominate the discussion . People who are particularly articulate or assertive, who have strong feelings that they urgently want to express, or who simply feel the need – and have the ability – to dominate can take up far more than their fair share of a discussion. This often means that quieter people have little or no chance to speak, and that those who disagree with the dominant individual(s) are shouted down and cease trying to make points. It’s up to the leader to cut off individuals who take far more than their share of time, or who try to limit discussion. This can be done in a relatively non-threatening way (“This is an interesting point, and it’s certainly worth the time we’ve spent on it, but there are other points of view that need to be heard as well. I think Alice has been waiting to speak…”), but it’s crucial to the open process and to the comfort and effectiveness of the group.

- Don’t let one point of view override others , unless it’s based on facts and logic, and is actually convincing group members to change their minds. If a point of view dominates because of its merits, its appeal to participants’ intellectual and ethical sensibilities, that’s fine. It’s in fact what you hope will happen in a good group discussion. If a point of view dominates because of the aggressiveness of its supporters, or because it’s presented as something it’s wrong to oppose (“People who disagree with the President are unpatriotic and hate their country”), that’s intellectual bullying or blackmail, and is the opposite of an open discussion. As leader, you should point it out when that’s happening, and make sure other points of view are aired and examined.

Sometimes individuals or factions that are trying to dominate can disrupt the process of the group. Both Sections 1 and 2 of this chapter contain some guidelines for dealing with this type of situation.

- Don’t assume that anyone holds particular opinions or positions because of his culture, background, race, personal style, etc . People are individuals, and can’t be judged by their exteriors. You can find out what someone thinks by asking, or by listening when he speaks.

- Don’t assume that someone from a particular culture, race, or background speaks for everyone else from that situation . She may or may not represent the general opinion of people from situations similar to hers…or there may not be a general opinion among them. In a group discussion, no one should be asked or assumed to represent anything more than herself.

The exception here is when someone has been chosen by her community or group to represent its point of view in a multi-sector discussion. Even in that situation, the individual may find herself swayed by others’ arguments, or may have ideas of her own. She may have agreed to sponsor particular ideas that are important to her group, but she may still have her own opinions as well, especially in other areas.

- Don’t be the font of all wisdom . Even if you know more about the discussion topic than most others in the group (if you’re the teacher of a class, for instance), presenting yourself as the intellectual authority denies group members the chance to discuss the topic freely and without pressure. Furthermore, some of them may have ideas you haven’t considered, or experiences that give them insights into the topic that you’re never likely to have. Model learning behavior, not teaching behavior.

If you’re asked your opinion directly, you should answer honestly. You have some choices about how you do that, however. One is to state your opinion, but make very clear that it’s an opinion, not a fact, and that other people believe differently. Another is to ask to hold your opinion until the end of the discussion, so as not to influence anyone’s thinking while it’s going on. Yet another is to give your opinion after all other members of the group have stated theirs, and then discuss the similarities and differences among all the opinions and people’s reasons for holding them. If you’re asked a direct question, you might want to answer it if it’s a question of fact and you know the answer, and if it’s relevant to the discussion. If the question is less clear-cut, you might want to throw it back to the group, and use it as a spur to discussion.

Group discussions are common in our society, and have a variety of purposes, from planning an intervention or initiative to mutual support to problem-solving to addressing an issue of local concern. An effective discussion group depends on a leader or facilitator who can guide it through an open process – the group chooses what it’s discussing, if not already determined, discusses it with no expectation of particular conclusions, encourages civil disagreement and argument, and makes sure that every member is included and no one dominates. It helps greatly if the leader comes to the task with a democratic or, especially, a collaborative style, and with an understanding of how a group functions.

A good group discussion leader has to pay attention to the process and content of the discussion as well as to the people who make up the group. She has to prepare the space and the setting to the extent possible; help the group establish ground rules that will keep it moving civilly and comfortably; provide whatever materials are necessary; familiarize herself with the topic; and make sure that any pre-discussion readings or assignments get to participants in plenty of time. Then she has to guide the discussion, being careful to promote an open process; involve everyone and let no one dominate; attend to the personal issues and needs of individual group members when they affect the group; summarize or clarify when appropriate; ask questions to keep the discussion moving, and put aside her own agenda, ego, and biases.

It’s not an easy task, but it can be extremely rewarding. An effective group discussion can lay the groundwork for action and real community change.

Online resources

Everyday-Democracy . Study Circles Resource Center. Information and publications related to study circles, participatory discussion groups meant to address community issues.

Facilitating Political Discussions from the Institute for Democracy and Higher Education at Tufts University is designed to assist experienced facilitators in training others to facilitate politically charged conversations. The materials are broken down into "modules" and facilitation trainers can use some or all of them to suit their needs.

Project on Civic Reflection provides information about leading study circles on civic reflection.

“ Suggestions for Leading Small-Group Discussions ,” prepared by Lee Haugen, Center for Teaching Excellence, Iowa State University, 1998. Tips on university teaching, but much of the information is useful in other circumstances as well.

“ Tips for Leading Discussions ,” by Felisa Tibbits, Human Rights Education Associates.

Print resources

Forsyth, D . Group Dynamics . (2006). (4th edition). Belmont, CA: Thomson Wadsworth.

Johnson, D., & Frank P. (2002). Joining Together: Group theory and group skills . (8th edition). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

What Is a Case Study?

Weighing the pros and cons of this method of research

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Cara Lustik is a fact-checker and copywriter.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Cara-Lustik-1000-77abe13cf6c14a34a58c2a0ffb7297da.jpg)

Verywell / Colleen Tighe

- Pros and Cons

What Types of Case Studies Are Out There?

Where do you find data for a case study, how do i write a psychology case study.

A case study is an in-depth study of one person, group, or event. In a case study, nearly every aspect of the subject's life and history is analyzed to seek patterns and causes of behavior. Case studies can be used in many different fields, including psychology, medicine, education, anthropology, political science, and social work.

The point of a case study is to learn as much as possible about an individual or group so that the information can be generalized to many others. Unfortunately, case studies tend to be highly subjective, and it is sometimes difficult to generalize results to a larger population.

While case studies focus on a single individual or group, they follow a format similar to other types of psychology writing. If you are writing a case study, we got you—here are some rules of APA format to reference.

At a Glance

A case study, or an in-depth study of a person, group, or event, can be a useful research tool when used wisely. In many cases, case studies are best used in situations where it would be difficult or impossible for you to conduct an experiment. They are helpful for looking at unique situations and allow researchers to gather a lot of˜ information about a specific individual or group of people. However, it's important to be cautious of any bias we draw from them as they are highly subjective.

What Are the Benefits and Limitations of Case Studies?

A case study can have its strengths and weaknesses. Researchers must consider these pros and cons before deciding if this type of study is appropriate for their needs.

One of the greatest advantages of a case study is that it allows researchers to investigate things that are often difficult or impossible to replicate in a lab. Some other benefits of a case study:

- Allows researchers to capture information on the 'how,' 'what,' and 'why,' of something that's implemented

- Gives researchers the chance to collect information on why one strategy might be chosen over another

- Permits researchers to develop hypotheses that can be explored in experimental research

On the other hand, a case study can have some drawbacks:

- It cannot necessarily be generalized to the larger population

- Cannot demonstrate cause and effect

- It may not be scientifically rigorous

- It can lead to bias

Researchers may choose to perform a case study if they want to explore a unique or recently discovered phenomenon. Through their insights, researchers develop additional ideas and study questions that might be explored in future studies.

It's important to remember that the insights from case studies cannot be used to determine cause-and-effect relationships between variables. However, case studies may be used to develop hypotheses that can then be addressed in experimental research.

Case Study Examples

There have been a number of notable case studies in the history of psychology. Much of Freud's work and theories were developed through individual case studies. Some great examples of case studies in psychology include:

- Anna O : Anna O. was a pseudonym of a woman named Bertha Pappenheim, a patient of a physician named Josef Breuer. While she was never a patient of Freud's, Freud and Breuer discussed her case extensively. The woman was experiencing symptoms of a condition that was then known as hysteria and found that talking about her problems helped relieve her symptoms. Her case played an important part in the development of talk therapy as an approach to mental health treatment.

- Phineas Gage : Phineas Gage was a railroad employee who experienced a terrible accident in which an explosion sent a metal rod through his skull, damaging important portions of his brain. Gage recovered from his accident but was left with serious changes in both personality and behavior.

- Genie : Genie was a young girl subjected to horrific abuse and isolation. The case study of Genie allowed researchers to study whether language learning was possible, even after missing critical periods for language development. Her case also served as an example of how scientific research may interfere with treatment and lead to further abuse of vulnerable individuals.

Such cases demonstrate how case research can be used to study things that researchers could not replicate in experimental settings. In Genie's case, her horrific abuse denied her the opportunity to learn a language at critical points in her development.

This is clearly not something researchers could ethically replicate, but conducting a case study on Genie allowed researchers to study phenomena that are otherwise impossible to reproduce.

There are a few different types of case studies that psychologists and other researchers might use:

- Collective case studies : These involve studying a group of individuals. Researchers might study a group of people in a certain setting or look at an entire community. For example, psychologists might explore how access to resources in a community has affected the collective mental well-being of those who live there.

- Descriptive case studies : These involve starting with a descriptive theory. The subjects are then observed, and the information gathered is compared to the pre-existing theory.

- Explanatory case studies : These are often used to do causal investigations. In other words, researchers are interested in looking at factors that may have caused certain things to occur.

- Exploratory case studies : These are sometimes used as a prelude to further, more in-depth research. This allows researchers to gather more information before developing their research questions and hypotheses .

- Instrumental case studies : These occur when the individual or group allows researchers to understand more than what is initially obvious to observers.

- Intrinsic case studies : This type of case study is when the researcher has a personal interest in the case. Jean Piaget's observations of his own children are good examples of how an intrinsic case study can contribute to the development of a psychological theory.

The three main case study types often used are intrinsic, instrumental, and collective. Intrinsic case studies are useful for learning about unique cases. Instrumental case studies help look at an individual to learn more about a broader issue. A collective case study can be useful for looking at several cases simultaneously.

The type of case study that psychology researchers use depends on the unique characteristics of the situation and the case itself.

There are a number of different sources and methods that researchers can use to gather information about an individual or group. Six major sources that have been identified by researchers are:

- Archival records : Census records, survey records, and name lists are examples of archival records.

- Direct observation : This strategy involves observing the subject, often in a natural setting . While an individual observer is sometimes used, it is more common to utilize a group of observers.

- Documents : Letters, newspaper articles, administrative records, etc., are the types of documents often used as sources.

- Interviews : Interviews are one of the most important methods for gathering information in case studies. An interview can involve structured survey questions or more open-ended questions.

- Participant observation : When the researcher serves as a participant in events and observes the actions and outcomes, it is called participant observation.

- Physical artifacts : Tools, objects, instruments, and other artifacts are often observed during a direct observation of the subject.

If you have been directed to write a case study for a psychology course, be sure to check with your instructor for any specific guidelines you need to follow. If you are writing your case study for a professional publication, check with the publisher for their specific guidelines for submitting a case study.

Here is a general outline of what should be included in a case study.

Section 1: A Case History

This section will have the following structure and content:

Background information : The first section of your paper will present your client's background. Include factors such as age, gender, work, health status, family mental health history, family and social relationships, drug and alcohol history, life difficulties, goals, and coping skills and weaknesses.

Description of the presenting problem : In the next section of your case study, you will describe the problem or symptoms that the client presented with.

Describe any physical, emotional, or sensory symptoms reported by the client. Thoughts, feelings, and perceptions related to the symptoms should also be noted. Any screening or diagnostic assessments that are used should also be described in detail and all scores reported.

Your diagnosis : Provide your diagnosis and give the appropriate Diagnostic and Statistical Manual code. Explain how you reached your diagnosis, how the client's symptoms fit the diagnostic criteria for the disorder(s), or any possible difficulties in reaching a diagnosis.

Section 2: Treatment Plan

This portion of the paper will address the chosen treatment for the condition. This might also include the theoretical basis for the chosen treatment or any other evidence that might exist to support why this approach was chosen.

- Cognitive behavioral approach : Explain how a cognitive behavioral therapist would approach treatment. Offer background information on cognitive behavioral therapy and describe the treatment sessions, client response, and outcome of this type of treatment. Make note of any difficulties or successes encountered by your client during treatment.

- Humanistic approach : Describe a humanistic approach that could be used to treat your client, such as client-centered therapy . Provide information on the type of treatment you chose, the client's reaction to the treatment, and the end result of this approach. Explain why the treatment was successful or unsuccessful.

- Psychoanalytic approach : Describe how a psychoanalytic therapist would view the client's problem. Provide some background on the psychoanalytic approach and cite relevant references. Explain how psychoanalytic therapy would be used to treat the client, how the client would respond to therapy, and the effectiveness of this treatment approach.

- Pharmacological approach : If treatment primarily involves the use of medications, explain which medications were used and why. Provide background on the effectiveness of these medications and how monotherapy may compare with an approach that combines medications with therapy or other treatments.

This section of a case study should also include information about the treatment goals, process, and outcomes.

When you are writing a case study, you should also include a section where you discuss the case study itself, including the strengths and limitiations of the study. You should note how the findings of your case study might support previous research.

In your discussion section, you should also describe some of the implications of your case study. What ideas or findings might require further exploration? How might researchers go about exploring some of these questions in additional studies?

Need More Tips?

Here are a few additional pointers to keep in mind when formatting your case study:

- Never refer to the subject of your case study as "the client." Instead, use their name or a pseudonym.

- Read examples of case studies to gain an idea about the style and format.

- Remember to use APA format when citing references .

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011;11:100.

Crowe S, Cresswell K, Robertson A, Huby G, Avery A, Sheikh A. The case study approach . BMC Med Res Methodol . 2011 Jun 27;11:100. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-11-100

Gagnon, Yves-Chantal. The Case Study as Research Method: A Practical Handbook . Canada, Chicago Review Press Incorporated DBA Independent Pub Group, 2010.

Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods . United States, SAGE Publications, 2017.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Growth Tactics

Types of Group Discussion: Strategies for Effective Discussions

- 1 Understanding Group Discussion

- 2 Types of Group Discussion

- 3 Choosing a Suitable Topic

- 4 Strategies for Effective Group Discussions

- 5 Common Challenges in Group Discussions and How to Overcome Them

- 6 Technology and Group Discussions

- 7 Conclusion

Group discussion is a valuable tool for learning, collaboration, and fostering critical thinking skills. Whether you are a student preparing for an exam, an educator looking for ways to engage your students, or a leader trying to solve a problem, understanding the different types of group discussions, topics, and strategies is essential. In this blog post, we will explore the various types of group discussions, how to choose a suitable topic, and strategies for facilitating meaningful and productive discussions.

Understanding Group Discussion

Group discussions are a form of interactive communication that involves a small group of individuals sharing their thoughts, ideas, and opinions on a specific topic. These discussions can take place in various settings, such as classrooms, organizations, or professional settings, and can serve different purposes, such as problem-solving, decision-making, or brainstorming.

Types of Group Discussion

Group discussions offer a dynamic environment for sharing thoughts, ideas, and opinions. They can be beneficial for learning, collaboration, and developing critical thinking skills . Let’s explore three types of group discussions: case-based discussions, topic-based discussions, and structured group discussions.

1. Case-Based Discussions

In case-based discussions, participants analyze and discuss specific cases or scenarios. They evaluate possible solutions or approaches, which helps develop problem-solving and analytical skills. By actively engaging with real or hypothetical case studies, participants enhance their ability to think critically about complex situations.

2. Topic-Based Discussions

Topic-based discussions center around a specific subject or theme. Participants express their opinions, present arguments, and explore different viewpoints. These discussions improve communication skills and foster critical thinking as participants analyze and evaluate various perspectives on a given topic.

3. Structured Group Discussions

Structured group discussions follow predefined formats or rules. A moderator guides the discussion by posing questions and facilitating conversation. This format ensures active participation and constructive exchanges, providing a framework for focused and productive discussions.

By understanding the different types of group discussions, participants can choose the most suitable format for their goals and create an engaging and interactive environment for meaningful conversations.

Choosing a Suitable Topic

Selecting an appropriate topic is crucial for a successful group discussion. Consider the following factors when choosing a topic:

1. Relevance to the Participants

The topic should be relevant to the participants’ interests, experiences, or areas of study. This helps create a sense of engagement and encourages active participation.

2. Controversial and Thought-Provoking

Controversial topics or those that require critical thinking and analysis can spark lively and meaningful discussions. Avoid vague or overly simplistic topics that do not stimulate thoughtful discussion.

3. Current Affairs and Real-World Issues

Discussing current affairs and real-world issues helps participants develop an understanding of the socio-economic and political landscape. These topics encourage participants to think critically and evaluate different perspectives.

Strategies for Effective Group Discussions

To make group discussions productive and engaging, consider implementing the following strategies:

1. Establish Clear Ground Rules

Start by establishing clear guidelines and expectations for the discussion. These ground rules should emphasize the importance of active listening, respectful communication, and equal participation. By setting a foundation of mutual respect and inclusivity, you create a safe and open environment for all participants to contribute their ideas.

2. Encourage the Expression of Diverse Perspectives

Promote a culture that values and encourages diverse perspectives. Encourage participants to share their unique viewpoints, experiences, and ideas. By actively seeking and embracing different perspectives, you enrich the conversation and foster a deeper understanding of the topic at hand. Remember that diversity of thought leads to more innovative and creative solutions.

3. Foster Lateral Thinking and Problem-Solving

Encourage participants to think critically and approach problems from various angles. Foster an environment that values and promotes lateral thinking, which involves exploring unconventional or alternative solutions. Encourage participants to challenge assumptions and consider different perspectives to generate innovative ideas and solutions.

4. Provide Structured Discussion Prompts

Prepare a list of discussion prompts or questions in advance to guide the conversation. These prompts should cover various aspects of the topic and encourage participants to think critically and express their thoughts. Structured discussion prompts provide a framework and keep the conversation focused and productive. This helps ensure that all important aspects of the topic are explored.

5. Facilitate Active Participation

Actively engage all participants to facilitate their active participation in the discussion. Encourage quieter participants to contribute by directly asking for their input or by creating a supportive environment that encourages them to share their thoughts. By ensuring that everyone feels heard and valued, you create a space for meaningful and collaborative discussions.

By implementing these strategies, you can make your group discussions more effective, inclusive, and thought-provoking. These approaches promote critical thinking, enhance problem-solving skills, and allow for the exploration of multiple perspectives. Remember that an open and respectful environment is key to fostering successful group discussions.

Common Challenges in Group Discussions and How to Overcome Them

Group discussions can be an effective way to generate ideas, facilitate collaboration, and arrive at well-informed decisions. However, there are common challenges that can arise during group discussions. Here are some of these challenges and strategies to overcome them:

1. Dominant Personalities

Some participants may have dominant personalities that can overpower the conversation, making others feel unheard or overshadowed. To prevent dominance, set equal speaking opportunities for everyone. Encourage active listening to make sure everyone’s voice is heard. If someone is dominating the conversation, try direct questions to other participants and redirecting the conversation towards the quieter members.

2. Groupthink

Groupthink occurs when the desire for group harmony leads to conformity and a lack of critical thinking. To avoid it, make sure to encourage diverse opinions, ideas, and perspectives. Assign a designated devil’s advocate whose role is to challenge proposed ideas. Anonymous ideation sessions and setting the tone of every idea is welcome helps in the same.

3. Lack of Focus

Conversations may easily veer off-topic or lack a clear focus, making it difficult to achieve the intended goals. Keep the conversation focused by setting and reviewing an agenda periodically. Encourage participants to take constructive breaks that revitalize their focus. Use summarizing techniques throughout the discussion to align the focus.

4. Unequal Participation

In some situations, certain individuals may dominate conversations while others stay silent. Encourage participation by assigning specific roles, and asking directly for input from quieter participants. Brainstorming techniques can be used like round-robin, think-pair-share, or small groups to ensure equal participation.

5. Conflict Resolution

Conflicts or disagreements may arise during group discussions, leading to stress and uncertainty. To handle conflicts constructively, encourage active listening, acknowledging different perspectives and viewpoints, facilitating open dialogue, and seeking win-win solutions. By creating an open and inclusive space to resolve conflicts, the group’s dynamics and outcomes will enhance positively.

By proactively addressing these common challenges, groups can have meaningful conversations that lead to actionable insights and productive solutions.

Technology and Group Discussions

Technology has revolutionized the way we communicate and collaborate in group settings. With the rise of virtual meetings, video conferencing, and online collaboration tools, it’s now easier than ever to conduct group discussions from anywhere in the world. However, with these benefits come new challenges as well. Here are some ways technology can impact group discussions and how to overcome them.

Pros of Using Technology in Group Discussions

Increased Flexibility and Accessibility : With online tools, group members can join meetings from anywhere, at any time. This allows for greater flexibility and accessibility, making it easier for people to participate in group discussions even if they are not physically present.

Improved Collaboration : Virtual tools allow group members to collaborate in real-time, regardless of their physical location. This makes it easier for members to share ideas and information, and work together to achieve a common goal.

Reduced Costs : Virtual meetings can significantly reduce costs associated with travel and facility rental. This makes it easier for groups with limited resources to conduct discussions without sacrificing the benefits of in-person meetings.

Cons of Using Technology in Group Discussions

Technical Difficulties : Technical difficulties can arise during virtual meetings, which can delay progress and cause frustration. This can be overcome by having all participants test the technology before the meeting and ensuring all participants have a stable internet connection.

Lack of Non-Verbal Cues : During virtual meetings, non-verbal cues such as body language and facial expressions can be difficult to read. To overcome this, group members must be clear and concise with their verbal communication.

Distractions : Since virtual meetings can be conducted from anywhere, it’s easy for participants to become distracted by their surroundings. To overcome this, establish ground rules for participants such as turning off notifications or finding a quiet space to participate in the discussion.

In conclusion, technology has revolutionized the way we conduct group discussions and collaboration. By being aware of the pros and cons of using virtual meetings and online collaboration tools, groups can take advantage of the benefits while mitigating the challenges.