Why Schools Need to Change Yes, We Can Define, Teach, and Assess Critical Thinking Skills

Jeff Heyck-Williams (He, His, Him) Director of the Two Rivers Learning Institute in Washington, DC

Today’s learners face an uncertain present and a rapidly changing future that demand far different skills and knowledge than were needed in the 20th century. We also know so much more about enabling deep, powerful learning than we ever did before. Our collective future depends on how well young people prepare for the challenges and opportunities of 21st-century life.

Critical thinking is a thing. We can define it; we can teach it; and we can assess it.

While the idea of teaching critical thinking has been bandied around in education circles since at least the time of John Dewey, it has taken greater prominence in the education debates with the advent of the term “21st century skills” and discussions of deeper learning. There is increasing agreement among education reformers that critical thinking is an essential ingredient for long-term success for all of our students.

However, there are still those in the education establishment and in the media who argue that critical thinking isn’t really a thing, or that these skills aren’t well defined and, even if they could be defined, they can’t be taught or assessed.

To those naysayers, I have to disagree. Critical thinking is a thing. We can define it; we can teach it; and we can assess it. In fact, as part of a multi-year Assessment for Learning Project , Two Rivers Public Charter School in Washington, D.C., has done just that.

Before I dive into what we have done, I want to acknowledge that some of the criticism has merit.

First, there are those that argue that critical thinking can only exist when students have a vast fund of knowledge. Meaning that a student cannot think critically if they don’t have something substantive about which to think. I agree. Students do need a robust foundation of core content knowledge to effectively think critically. Schools still have a responsibility for building students’ content knowledge.

However, I would argue that students don’t need to wait to think critically until after they have mastered some arbitrary amount of knowledge. They can start building critical thinking skills when they walk in the door. All students come to school with experience and knowledge which they can immediately think critically about. In fact, some of the thinking that they learn to do helps augment and solidify the discipline-specific academic knowledge that they are learning.

The second criticism is that critical thinking skills are always highly contextual. In this argument, the critics make the point that the types of thinking that students do in history is categorically different from the types of thinking students do in science or math. Thus, the idea of teaching broadly defined, content-neutral critical thinking skills is impossible. I agree that there are domain-specific thinking skills that students should learn in each discipline. However, I also believe that there are several generalizable skills that elementary school students can learn that have broad applicability to their academic and social lives. That is what we have done at Two Rivers.

Defining Critical Thinking Skills

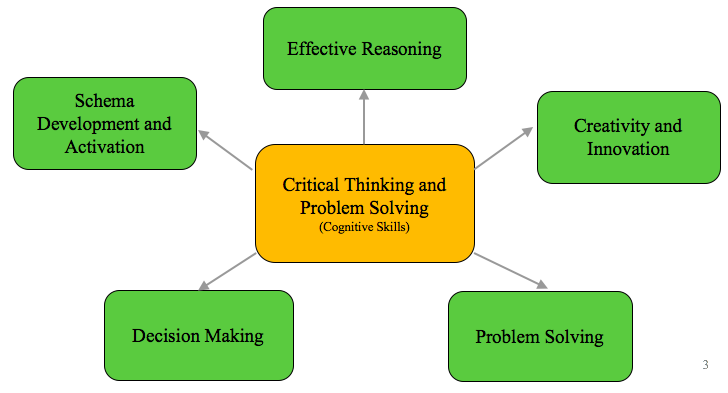

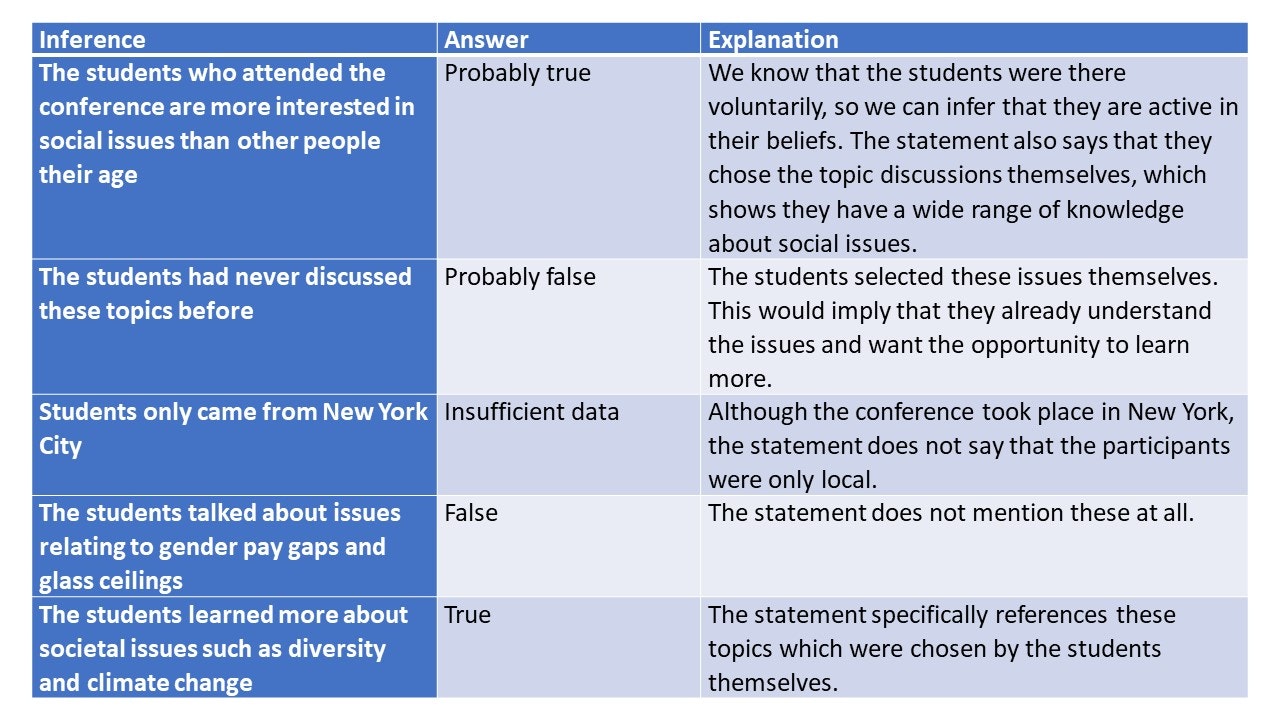

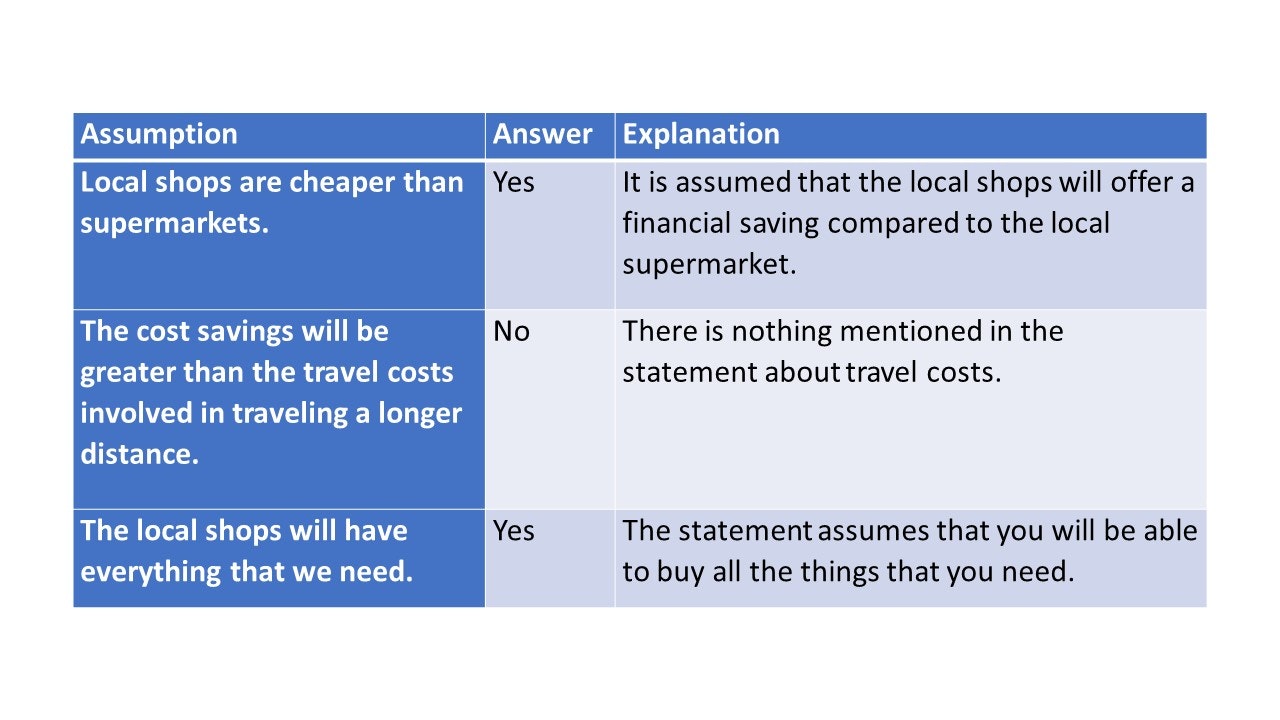

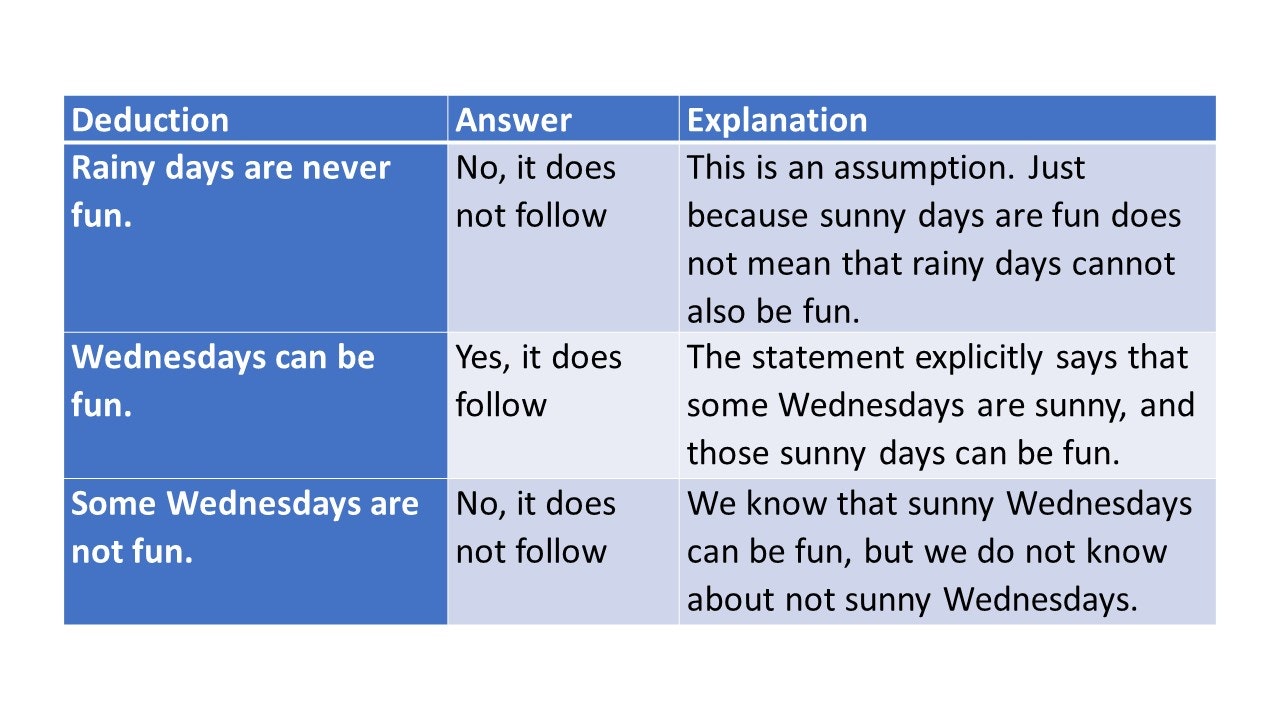

We began this work by first defining what we mean by critical thinking. After a review of the literature and looking at the practice at other schools, we identified five constructs that encompass a set of broadly applicable skills: schema development and activation; effective reasoning; creativity and innovation; problem solving; and decision making.

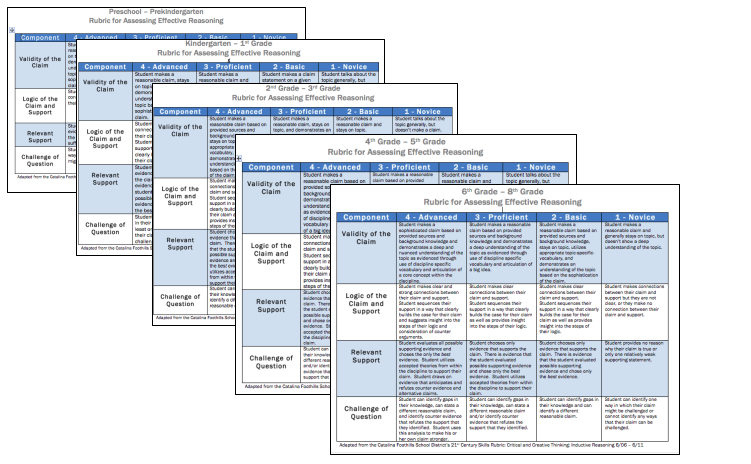

We then created rubrics to provide a concrete vision of what each of these constructs look like in practice. Working with the Stanford Center for Assessment, Learning and Equity (SCALE) , we refined these rubrics to capture clear and discrete skills.

For example, we defined effective reasoning as the skill of creating an evidence-based claim: students need to construct a claim, identify relevant support, link their support to their claim, and identify possible questions or counter claims. Rubrics provide an explicit vision of the skill of effective reasoning for students and teachers. By breaking the rubrics down for different grade bands, we have been able not only to describe what reasoning is but also to delineate how the skills develop in students from preschool through 8th grade.

Before moving on, I want to freely acknowledge that in narrowly defining reasoning as the construction of evidence-based claims we have disregarded some elements of reasoning that students can and should learn. For example, the difference between constructing claims through deductive versus inductive means is not highlighted in our definition. However, by privileging a definition that has broad applicability across disciplines, we are able to gain traction in developing the roots of critical thinking. In this case, to formulate well-supported claims or arguments.

Teaching Critical Thinking Skills

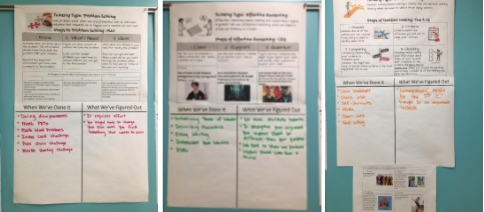

The definitions of critical thinking constructs were only useful to us in as much as they translated into practical skills that teachers could teach and students could learn and use. Consequently, we have found that to teach a set of cognitive skills, we needed thinking routines that defined the regular application of these critical thinking and problem-solving skills across domains. Building on Harvard’s Project Zero Visible Thinking work, we have named routines aligned with each of our constructs.

For example, with the construct of effective reasoning, we aligned the Claim-Support-Question thinking routine to our rubric. Teachers then were able to teach students that whenever they were making an argument, the norm in the class was to use the routine in constructing their claim and support. The flexibility of the routine has allowed us to apply it from preschool through 8th grade and across disciplines from science to economics and from math to literacy.

Kathryn Mancino, a 5th grade teacher at Two Rivers, has deliberately taught three of our thinking routines to students using the anchor charts above. Her charts name the components of each routine and has a place for students to record when they’ve used it and what they have figured out about the routine. By using this structure with a chart that can be added to throughout the year, students see the routines as broadly applicable across disciplines and are able to refine their application over time.

Assessing Critical Thinking Skills

By defining specific constructs of critical thinking and building thinking routines that support their implementation in classrooms, we have operated under the assumption that students are developing skills that they will be able to transfer to other settings. However, we recognized both the importance and the challenge of gathering reliable data to confirm this.

With this in mind, we have developed a series of short performance tasks around novel discipline-neutral contexts in which students can apply the constructs of thinking. Through these tasks, we have been able to provide an opportunity for students to demonstrate their ability to transfer the types of thinking beyond the original classroom setting. Once again, we have worked with SCALE to define tasks where students easily access the content but where the cognitive lift requires them to demonstrate their thinking abilities.

These assessments demonstrate that it is possible to capture meaningful data on students’ critical thinking abilities. They are not intended to be high stakes accountability measures. Instead, they are designed to give students, teachers, and school leaders discrete formative data on hard to measure skills.

While it is clearly difficult, and we have not solved all of the challenges to scaling assessments of critical thinking, we can define, teach, and assess these skills . In fact, knowing how important they are for the economy of the future and our democracy, it is essential that we do.

Jeff Heyck-Williams (He, His, Him)

Director of the two rivers learning institute.

Jeff Heyck-Williams is the director of the Two Rivers Learning Institute and a founder of Two Rivers Public Charter School. He has led work around creating school-wide cultures of mathematics, developing assessments of critical thinking and problem-solving, and supporting project-based learning.

Read More About Why Schools Need to Change

Nurturing STEM Identity and Belonging: The Role of Equitable Program Implementation in Project Invent

Alexis Lopez (she/her)

May 9, 2024

Bring Your Vision for Student Success to Life with NGLC and Bravely

March 13, 2024

For Ethical AI, Listen to Teachers

Jason Wilmot

October 23, 2023

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 8 min read

Critical Thinking

Developing the right mindset and skills.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

We make hundreds of decisions every day and, whether we realize it or not, we're all critical thinkers.

We use critical thinking each time we weigh up our options, prioritize our responsibilities, or think about the likely effects of our actions. It's a crucial skill that helps us to cut out misinformation and make wise decisions. The trouble is, we're not always very good at it!

In this article, we'll explore the key skills that you need to develop your critical thinking skills, and how to adopt a critical thinking mindset, so that you can make well-informed decisions.

What Is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is the discipline of rigorously and skillfully using information, experience, observation, and reasoning to guide your decisions, actions, and beliefs. You'll need to actively question every step of your thinking process to do it well.

Collecting, analyzing and evaluating information is an important skill in life, and a highly valued asset in the workplace. People who score highly in critical thinking assessments are also rated by their managers as having good problem-solving skills, creativity, strong decision-making skills, and good overall performance. [1]

Key Critical Thinking Skills

Critical thinkers possess a set of key characteristics which help them to question information and their own thinking. Focus on the following areas to develop your critical thinking skills:

Being willing and able to explore alternative approaches and experimental ideas is crucial. Can you think through "what if" scenarios, create plausible options, and test out your theories? If not, you'll tend to write off ideas and options too soon, so you may miss the best answer to your situation.

To nurture your curiosity, stay up to date with facts and trends. You'll overlook important information if you allow yourself to become "blinkered," so always be open to new information.

But don't stop there! Look for opposing views or evidence to challenge your information, and seek clarification when things are unclear. This will help you to reassess your beliefs and make a well-informed decision later. Read our article, Opening Closed Minds , for more ways to stay receptive.

Logical Thinking

You must be skilled at reasoning and extending logic to come up with plausible options or outcomes.

It's also important to emphasize logic over emotion. Emotion can be motivating but it can also lead you to take hasty and unwise action, so control your emotions and be cautious in your judgments. Know when a conclusion is "fact" and when it is not. "Could-be-true" conclusions are based on assumptions and must be tested further. Read our article, Logical Fallacies , for help with this.

Use creative problem solving to balance cold logic. By thinking outside of the box you can identify new possible outcomes by using pieces of information that you already have.

Self-Awareness

Many of the decisions we make in life are subtly informed by our values and beliefs. These influences are called cognitive biases and it can be difficult to identify them in ourselves because they're often subconscious.

Practicing self-awareness will allow you to reflect on the beliefs you have and the choices you make. You'll then be better equipped to challenge your own thinking and make improved, unbiased decisions.

One particularly useful tool for critical thinking is the Ladder of Inference . It allows you to test and validate your thinking process, rather than jumping to poorly supported conclusions.

Developing a Critical Thinking Mindset

Combine the above skills with the right mindset so that you can make better decisions and adopt more effective courses of action. You can develop your critical thinking mindset by following this process:

Gather Information

First, collect data, opinions and facts on the issue that you need to solve. Draw on what you already know, and turn to new sources of information to help inform your understanding. Consider what gaps there are in your knowledge and seek to fill them. And look for information that challenges your assumptions and beliefs.

Be sure to verify the authority and authenticity of your sources. Not everything you read is true! Use this checklist to ensure that your information is valid:

- Are your information sources trustworthy ? (For example, well-respected authors, trusted colleagues or peers, recognized industry publications, websites, blogs, etc.)

- Is the information you have gathered up to date ?

- Has the information received any direct criticism ?

- Does the information have any errors or inaccuracies ?

- Is there any evidence to support or corroborate the information you have gathered?

- Is the information you have gathered subjective or biased in any way? (For example, is it based on opinion, rather than fact? Is any of the information you have gathered designed to promote a particular service or organization?)

If any information appears to be irrelevant or invalid, don't include it in your decision making. But don't omit information just because you disagree with it, or your final decision will be flawed and bias.

Now observe the information you have gathered, and interpret it. What are the key findings and main takeaways? What does the evidence point to? Start to build one or two possible arguments based on what you have found.

You'll need to look for the details within the mass of information, so use your powers of observation to identify any patterns or similarities. You can then analyze and extend these trends to make sensible predictions about the future.

To help you to sift through the multiple ideas and theories, it can be useful to group and order items according to their characteristics. From here, you can compare and contrast the different items. And once you've determined how similar or different things are from one another, Paired Comparison Analysis can help you to analyze them.

The final step involves challenging the information and rationalizing its arguments.

Apply the laws of reason (induction, deduction, analogy) to judge an argument and determine its merits. To do this, it's essential that you can determine the significance and validity of an argument to put it in the correct perspective. Take a look at our article, Rational Thinking , for more information about how to do this.

Once you have considered all of the arguments and options rationally, you can finally make an informed decision.

Afterward, take time to reflect on what you have learned and what you found challenging. Step back from the detail of your decision or problem, and look at the bigger picture. Record what you've learned from your observations and experience.

Critical thinking involves rigorously and skilfully using information, experience, observation, and reasoning to guide your decisions, actions and beliefs. It's a useful skill in the workplace and in life.

You'll need to be curious and creative to explore alternative possibilities, but rational to apply logic, and self-aware to identify when your beliefs could affect your decisions or actions.

You can demonstrate a high level of critical thinking by validating your information, analyzing its meaning, and finally evaluating the argument.

Critical Thinking Infographic

See Critical Thinking represented in our infographic: An Elementary Guide to Critical Thinking .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

Snyder's hope theory.

Cultivating Aspiration in Your Life

Mindfulness in the Workplace

Focusing the Mind by Staying Present

Add comment

Comments (1)

priyanka ghogare

Gain essential management and leadership skills

Busy schedule? No problem. Learn anytime, anywhere.

Subscribe to unlimited access to meticulously researched, evidence-based resources.

Join today and save on an annual membership!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Latest Updates

Better Public Speaking

How to Build Confidence in Others

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

How to create psychological safety at work.

Speaking up without fear

How to Guides

Pain Points Podcast - Presentations Pt 1

How do you get better at presenting?

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

The science of a good night's sleep infographic.

Infographic Transcript

Infographic

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

- Top Courses

- Online Degrees

- Find your New Career

- Join for Free

What Are Critical Thinking Skills and Why Are They Important?

Learn what critical thinking skills are, why they’re important, and how to develop and apply them in your workplace and everyday life.

![critical thinking skills inventory [Featured Image]: Project Manager, approaching and analyzing the latest project with a team member,](https://d3njjcbhbojbot.cloudfront.net/api/utilities/v1/imageproxy/https://images.ctfassets.net/wp1lcwdav1p1/1SOj8kON2XLXVb6u3bmDwN/62a5b68b69ec07b192de34b7ce8fa28a/GettyImages-598260236.jpg?w=1500&h=680&q=60&fit=fill&f=faces&fm=jpg&fl=progressive&auto=format%2Ccompress&dpr=1&w=1000)

We often use critical thinking skills without even realizing it. When you make a decision, such as which cereal to eat for breakfast, you're using critical thinking to determine the best option for you that day.

Critical thinking is like a muscle that can be exercised and built over time. It is a skill that can help propel your career to new heights. You'll be able to solve workplace issues, use trial and error to troubleshoot ideas, and more.

We'll take you through what it is and some examples so you can begin your journey in mastering this skill.

What is critical thinking?

Critical thinking is the ability to interpret, evaluate, and analyze facts and information that are available, to form a judgment or decide if something is right or wrong.

More than just being curious about the world around you, critical thinkers make connections between logical ideas to see the bigger picture. Building your critical thinking skills means being able to advocate your ideas and opinions, present them in a logical fashion, and make decisions for improvement.

Build job-ready skills with a Coursera Plus subscription

- Get access to 7,000+ learning programs from world-class universities and companies, including Google, Yale, Salesforce, and more

- Try different courses and find your best fit at no additional cost

- Earn certificates for learning programs you complete

- A subscription price of $59/month, cancel anytime

Why is critical thinking important?

Critical thinking is useful in many areas of your life, including your career. It makes you a well-rounded individual, one who has looked at all of their options and possible solutions before making a choice.

According to the University of the People in California, having critical thinking skills is important because they are [ 1 ]:

Crucial for the economy

Essential for improving language and presentation skills

Very helpful in promoting creativity

Important for self-reflection

The basis of science and democracy

Critical thinking skills are used every day in a myriad of ways and can be applied to situations such as a CEO approaching a group project or a nurse deciding in which order to treat their patients.

Examples of common critical thinking skills

Critical thinking skills differ from individual to individual and are utilized in various ways. Examples of common critical thinking skills include:

Identification of biases: Identifying biases means knowing there are certain people or things that may have an unfair prejudice or influence on the situation at hand. Pointing out these biases helps to remove them from contention when it comes to solving the problem and allows you to see things from a different perspective.

Research: Researching details and facts allows you to be prepared when presenting your information to people. You’ll know exactly what you’re talking about due to the time you’ve spent with the subject material, and you’ll be well-spoken and know what questions to ask to gain more knowledge. When researching, always use credible sources and factual information.

Open-mindedness: Being open-minded when having a conversation or participating in a group activity is crucial to success. Dismissing someone else’s ideas before you’ve heard them will inhibit you from progressing to a solution, and will often create animosity. If you truly want to solve a problem, you need to be willing to hear everyone’s opinions and ideas if you want them to hear yours.

Analysis: Analyzing your research will lead to you having a better understanding of the things you’ve heard and read. As a true critical thinker, you’ll want to seek out the truth and get to the source of issues. It’s important to avoid taking things at face value and always dig deeper.

Problem-solving: Problem-solving is perhaps the most important skill that critical thinkers can possess. The ability to solve issues and bounce back from conflict is what helps you succeed, be a leader, and effect change. One way to properly solve problems is to first recognize there’s a problem that needs solving. By determining the issue at hand, you can then analyze it and come up with several potential solutions.

How to develop critical thinking skills

You can develop critical thinking skills every day if you approach problems in a logical manner. Here are a few ways you can start your path to improvement:

1. Ask questions.

Be inquisitive about everything. Maintain a neutral perspective and develop a natural curiosity, so you can ask questions that develop your understanding of the situation or task at hand. The more details, facts, and information you have, the better informed you are to make decisions.

2. Practice active listening.

Utilize active listening techniques, which are founded in empathy, to really listen to what the other person is saying. Critical thinking, in part, is the cognitive process of reading the situation: the words coming out of their mouth, their body language, their reactions to your own words. Then, you might paraphrase to clarify what they're saying, so both of you agree you're on the same page.

3. Develop your logic and reasoning.

This is perhaps a more abstract task that requires practice and long-term development. However, think of a schoolteacher assessing the classroom to determine how to energize the lesson. There's options such as playing a game, watching a video, or challenging the students with a reward system. Using logic, you might decide that the reward system will take up too much time and is not an immediate fix. A video is not exactly relevant at this time. So, the teacher decides to play a simple word association game.

Scenarios like this happen every day, so next time, you can be more aware of what will work and what won't. Over time, developing your logic and reasoning will strengthen your critical thinking skills.

Learn tips and tricks on how to become a better critical thinker and problem solver through online courses from notable educational institutions on Coursera. Start with Introduction to Logic and Critical Thinking from Duke University or Mindware: Critical Thinking for the Information Age from the University of Michigan.

Article sources

University of the People, “ Why is Critical Thinking Important?: A Survival Guide , https://www.uopeople.edu/blog/why-is-critical-thinking-important/.” Accessed May 18, 2023.

Keep reading

Coursera staff.

Editorial Team

Coursera’s editorial team is comprised of highly experienced professional editors, writers, and fact...

This content has been made available for informational purposes only. Learners are advised to conduct additional research to ensure that courses and other credentials pursued meet their personal, professional, and financial goals.

- A Model for the National Assessment of Higher Order Thinking

- International Critical Thinking Essay Test

- Online Critical Thinking Basic Concepts Test

- Online Critical Thinking Basic Concepts Sample Test

Consequential Validity: Using Assessment to Drive Instruction

Translate this page from English...

*Machine translated pages not guaranteed for accuracy. Click Here for our professional translations.

Critical Thinking Testing and Assessment

The purpose of assessment in instruction is improvement. The purpose of assessing instruction for critical thinking is improving the teaching of discipline-based thinking (historical, biological, sociological, mathematical, etc.) It is to improve students’ abilities to think their way through content using disciplined skill in reasoning. The more particular we can be about what we want students to learn about critical thinking, the better we can devise instruction with that particular end in view.

The Foundation for Critical Thinking offers assessment instruments which share in the same general goal: to enable educators to gather evidence relevant to determining the extent to which instruction is teaching students to think critically (in the process of learning content). To this end, the Fellows of the Foundation recommend:

that academic institutions and units establish an oversight committee for critical thinking, and

that this oversight committee utilizes a combination of assessment instruments (the more the better) to generate incentives for faculty, by providing them with as much evidence as feasible of the actual state of instruction for critical thinking.

The following instruments are available to generate evidence relevant to critical thinking teaching and learning:

Course Evaluation Form : Provides evidence of whether, and to what extent, students perceive faculty as fostering critical thinking in instruction (course by course). Machine-scoreable.

Online Critical Thinking Basic Concepts Test : Provides evidence of whether, and to what extent, students understand the fundamental concepts embedded in critical thinking (and hence tests student readiness to think critically). Machine-scoreable.

Critical Thinking Reading and Writing Test : Provides evidence of whether, and to what extent, students can read closely and write substantively (and hence tests students' abilities to read and write critically). Short-answer.

International Critical Thinking Essay Test : Provides evidence of whether, and to what extent, students are able to analyze and assess excerpts from textbooks or professional writing. Short-answer.

Commission Study Protocol for Interviewing Faculty Regarding Critical Thinking : Provides evidence of whether, and to what extent, critical thinking is being taught at a college or university. Can be adapted for high school. Based on the California Commission Study . Short-answer.

Protocol for Interviewing Faculty Regarding Critical Thinking : Provides evidence of whether, and to what extent, critical thinking is being taught at a college or university. Can be adapted for high school. Short-answer.

Protocol for Interviewing Students Regarding Critical Thinking : Provides evidence of whether, and to what extent, students are learning to think critically at a college or university. Can be adapted for high school). Short-answer.

Criteria for Critical Thinking Assignments : Can be used by faculty in designing classroom assignments, or by administrators in assessing the extent to which faculty are fostering critical thinking.

Rubrics for Assessing Student Reasoning Abilities : A useful tool in assessing the extent to which students are reasoning well through course content.

All of the above assessment instruments can be used as part of pre- and post-assessment strategies to gauge development over various time periods.

Consequential Validity

All of the above assessment instruments, when used appropriately and graded accurately, should lead to a high degree of consequential validity. In other words, the use of the instruments should cause teachers to teach in such a way as to foster critical thinking in their various subjects. In this light, for students to perform well on the various instruments, teachers will need to design instruction so that students can perform well on them. Students cannot become skilled in critical thinking without learning (first) the concepts and principles that underlie critical thinking and (second) applying them in a variety of forms of thinking: historical thinking, sociological thinking, biological thinking, etc. Students cannot become skilled in analyzing and assessing reasoning without practicing it. However, when they have routine practice in paraphrasing, summarizing, analyzing, and assessing, they will develop skills of mind requisite to the art of thinking well within any subject or discipline, not to mention thinking well within the various domains of human life.

For full copies of this and many other critical thinking articles, books, videos, and more, join us at the Center for Critical Thinking Community Online - the world's leading online community dedicated to critical thinking! Also featuring interactive learning activities, study groups, and even a social media component, this learning platform will change your conception of intellectual development.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

A Short Guide to Building Your Team’s Critical Thinking Skills

- Matt Plummer

Critical thinking isn’t an innate skill. It can be learned.

Most employers lack an effective way to objectively assess critical thinking skills and most managers don’t know how to provide specific instruction to team members in need of becoming better thinkers. Instead, most managers employ a sink-or-swim approach, ultimately creating work-arounds to keep those who can’t figure out how to “swim” from making important decisions. But it doesn’t have to be this way. To demystify what critical thinking is and how it is developed, the author’s team turned to three research-backed models: The Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment, Pearson’s RED Critical Thinking Model, and Bloom’s Taxonomy. Using these models, they developed the Critical Thinking Roadmap, a framework that breaks critical thinking down into four measurable phases: the ability to execute, synthesize, recommend, and generate.

With critical thinking ranking among the most in-demand skills for job candidates , you would think that educational institutions would prepare candidates well to be exceptional thinkers, and employers would be adept at developing such skills in existing employees. Unfortunately, both are largely untrue.

- Matt Plummer (@mtplummer) is the founder of Zarvana, which offers online programs and coaching services to help working professionals become more productive by developing time-saving habits. Before starting Zarvana, Matt spent six years at Bain & Company spin-out, The Bridgespan Group, a strategy and management consulting firm for nonprofits, foundations, and philanthropists.

Partner Center

- ADEA Connect

- Communities

- Career Opportunities

- New Thinking

- ADEA Governance

- House of Delegates

- Board of Directors

- Advisory Committees

- Sections and Special Interest Groups

- Governance Documents and Publications

- Dental Faculty Code of Conduct

- ADEAGies Foundation

- About ADEAGies Foundation

- ADEAGies Newsroom

- Gies Awards

- Press Center

- Strategic Directions

- 2023 Annual Report

- ADEA Membership

- Institutions

- Faculty and Staff

- Individuals

- Corporations

- ADEA Members

- Predoctoral Dental

- Allied Dental

- Nonfederal Advanced Dental

- U.S. Federal Dental

- Students, Residents and Fellows

- Corporate Members

- Member Directory

- Directory of Institutional Members (DIM)

- 5 Questions With

- ADEA Member to Member Recruitment

- Students, Residents, and Fellows

- Information For

- Deans & Program Directors

- Current Students & Residents

- Prospective Students

- Educational Meetings

- Upcoming Events

- 2025 Annual Session & Exhibition

- eLearn Webinars

- Past Events

- Professional Development

- eLearn Micro-credentials

- Leadership Institute

- Leadership Institute Alumni Association (LIAA)

- Faculty Development Programs

- ADEA Scholarships, Awards and Fellowships

- Academic Fellowship

- For Students

- For Dental Educators

- For Leadership Institute Fellows

- Teaching Resources

- ADEA weTeach®

- MedEdPORTAL

Critical Thinking Skills Toolbox

- Resources for Teaching

- Policy Topics

- Task Force Report

- Opioid Epidemic

- Financing Dental Education

- Holistic Review

- Sex-based Health Differences

- Access, Diversity and Inclusion

- ADEA Commission on Change and Innovation in Dental Education

- Tool Resources

- Campus Liaisons

- Policy Resources

- Policy Publications

- Holistic Review Workshops

- Leading Conversations Webinar Series

- Collaborations

- Summer Health Professions Education Program

- Minority Dental Faculty Development Program

- Federal Advocacy

- Dental School Legislators

- Policy Letters and Memos

- Legislative Process

- Federal Advocacy Toolkit

- State Information

- Opioid Abuse

- Tracking Map

- Loan Forgiveness Programs

- State Advocacy Toolkit

- Canadian Information

- Dental Schools

- Provincial Information

- ADEA Advocate

- Books and Guides

- About ADEA Publications

- 2023-24 Official Guide

- Dental School Explorer

- Dental Education Trends

- Ordering Publications

- ADEA Bookstore

- Newsletters

- About ADEA Newsletters

- Bulletin of Dental Education

- Charting Progress

- Subscribe to Newsletter

- Journal of Dental Education

- Subscriptions

- Submissions FAQs

- Data, Analysis and Research

- Educational Institutions

- Applicants, Enrollees and Graduates

- Dental School Seniors

- ADEA AADSAS® (Dental School)

- AADSAS Applicants

- Health Professions Advisors

- Admissions Officers

- ADEA CAAPID® (International Dentists)

- CAAPID Applicants

- Program Finder

- ADEA DHCAS® (Dental Hygiene Programs)

- DHCAS Applicants

- Program Directors

- ADEA PASS® (Advanced Dental Education Programs)

- PASS Applicants

- PASS Evaluators

- DentEd Jobs

- Information For:

- Introduction

- Overview of Critical Thinking Skills

- Teaching Observations

- Avenues for Research

CTS Tools for Faculty and Student Assessment

- Critical Thinking and Assessment

- Conclusions

- Bibliography

- Helpful Links

- Appendix A. Author's Impressions of Vignettes

A number of critical thinking skills inventories and measures have been developed:

Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal (WGCTA) Cornell Critical Thinking Test California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory (CCTDI) California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST) Health Science Reasoning Test (HSRT) Professional Judgment Rating Form (PJRF) Teaching for Thinking Student Course Evaluation Form Holistic Critical Thinking Scoring Rubric Peer Evaluation of Group Presentation Form

Excluding the Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal and the Cornell Critical Thinking Test, Facione and Facione developed the critical thinking skills instruments listed above. However, it is important to point out that all of these measures are of questionable utility for dental educators because their content is general rather than dental education specific. (See Critical Thinking and Assessment .)

Table 7. Purposes of Critical Thinking Skills Instruments

Reliability and Validity

Reliability means that individual scores from an instrument should be the same or nearly the same from one administration of the instrument to another. The instrument can be assumed to be free of bias and measurement error (68). Alpha coefficients are often used to report an estimate of internal consistency. Scores of .70 or higher indicate that the instrument has high reliability when the stakes are moderate. Scores of .80 and higher are appropriate when the stakes are high.

Validity means that individual scores from a particular instrument are meaningful, make sense, and allow researchers to draw conclusions from the sample to the population that is being studied (69) Researchers often refer to "content" or "face" validity. Content validity or face validity is the extent to which questions on an instrument are representative of the possible questions that a researcher could ask about that particular content or skills.

Watson-Glaser Critical Thinking Appraisal-FS (WGCTA-FS)

The WGCTA-FS is a 40-item inventory created to replace Forms A and B of the original test, which participants reported was too long.70 This inventory assesses test takers' skills in:

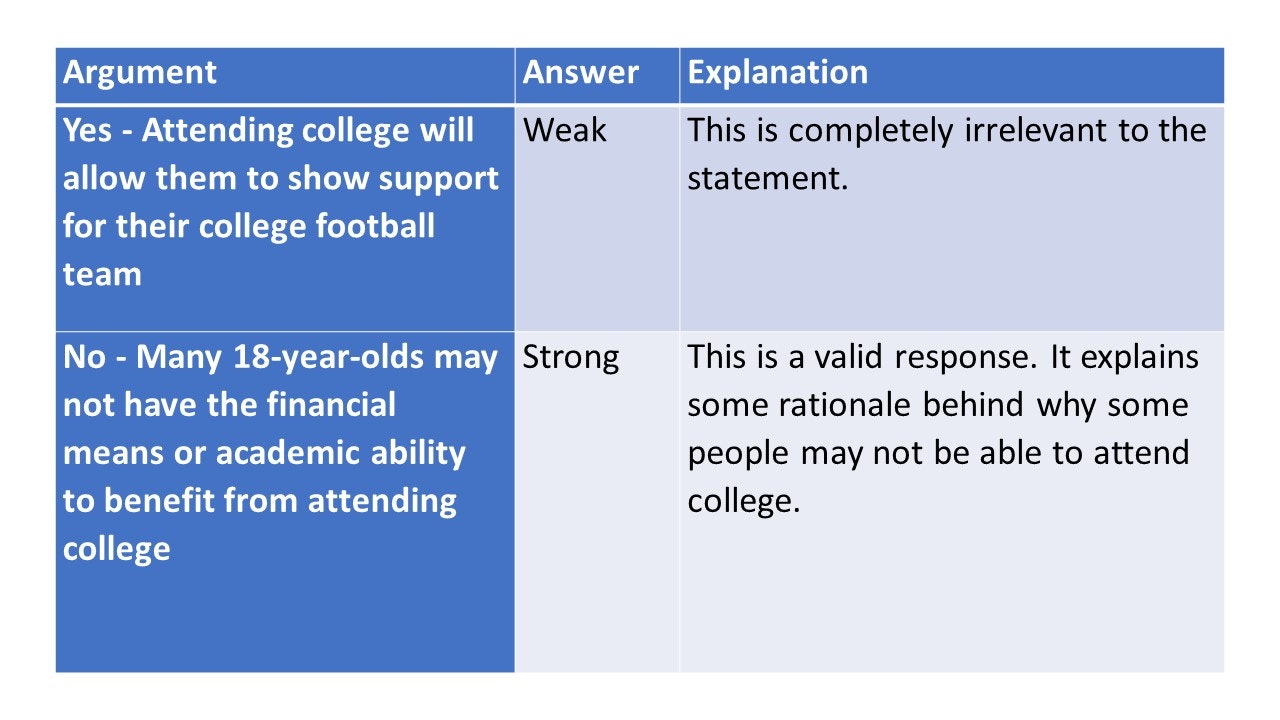

(a) Inference: the extent to which the individual recognizes whether assumptions are clearly stated (b) Recognition of assumptions: whether an individual recognizes whether assumptions are clearly stated (c) Deduction: whether an individual decides if certain conclusions follow the information provided (d) Interpretation: whether an individual considers evidence provided and determines whether generalizations from data are warranted (e) Evaluation of arguments: whether an individual distinguishes strong and relevant arguments from weak and irrelevant arguments

Researchers investigated the reliability and validity of the WGCTA-FS for subjects in academic fields. Participants included 586 university students. Internal consistencies for the total WGCTA-FS among students majoring in psychology, educational psychology, and special education, including undergraduates and graduates, ranged from .74 to .92. The correlations between course grades and total WGCTA-FS scores for all groups ranged from .24 to .62 and were significant at the p < .05 of p < .01. In addition, internal consistency and test-retest reliability for the WGCTA-FS have been measured as .81. The WGCTA-FS was found to be a reliable and valid instrument for measuring critical thinking (71).

Cornell Critical Thinking Test (CCTT)

There are two forms of the CCTT, X and Z. Form X is for students in grades 4-14. Form Z is for advanced and gifted high school students, undergraduate and graduate students, and adults. Reliability estimates for Form Z range from .49 to .87 across the 42 groups who have been tested. Measures of validity were computed in standard conditions, roughly defined as conditions that do not adversely affect test performance. Correlations between Level Z and other measures of critical thinking are about .50.72 The CCTT is reportedly as predictive of graduate school grades as the Graduate Record Exam (GRE), a measure of aptitude, and the Miller Analogies Test, and tends to correlate between .2 and .4.73

California Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory (CCTDI)

Facione and Facione have reported significant relationships between the CCTDI and the CCTST. When faculty focus on critical thinking in planning curriculum development, modest cross-sectional and longitudinal gains have been demonstrated in students' CTS.74 The CCTDI consists of seven subscales and an overall score. The recommended cut-off score for each scale is 40, the suggested target score is 50, and the maximum score is 60. Scores below 40 on a specific scale are weak in that CT disposition, and scores above 50 on a scale are strong in that dispositional aspect. An overall score of 280 shows serious deficiency in disposition toward CT, while an overall score of 350 (while rare) shows across the board strength. The seven subscales are analyticity, self-confidence, inquisitiveness, maturity, open-mindedness, systematicity, and truth seeking (75).

In a study of instructional strategies and their influence on the development of critical thinking among undergraduate nursing students, Tiwari, Lai, and Yuen found that, compared with lecture students, PBL students showed significantly greater improvement in overall CCTDI (p = .0048), Truth seeking (p = .0008), Analyticity (p =.0368) and Critical Thinking Self-confidence (p =.0342) subscales from the first to the second time points; in overall CCTDI (p = .0083), Truth seeking (p= .0090), and Analyticity (p =.0354) subscales from the second to the third time points; and in Truth seeking (p = .0173) and Systematicity (p = .0440) subscales scores from the first to the fourth time points (76). California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCTST)

Studies have shown the California Critical Thinking Skills Test captured gain scores in students' critical thinking over one quarter or one semester. Multiple health science programs have demonstrated significant gains in students' critical thinking using site-specific curriculum. Studies conducted to control for re-test bias showed no testing effect from pre- to post-test means using two independent groups of CT students. Since behavioral science measures can be impacted by social-desirability bias-the participant's desire to answer in ways that would please the researcher-researchers are urged to have participants take the Marlowe Crowne Social Desirability Scale simultaneously when measuring pre- and post-test changes in critical thinking skills. The CCTST is a 34-item instrument. This test has been correlated with the CCTDI with a sample of 1,557 nursing education students. Results show that, r = .201, and the relationship between the CCTST and the CCTDI is significant at p< .001. Significant relationships between CCTST and other measures including the GRE total, GRE-analytic, GRE-Verbal, GRE-Quantitative, the WGCTA, and the SAT Math and Verbal have also been reported. The two forms of the CCTST, A and B, are considered statistically significant. Depending on the testing, context KR-20 alphas range from .70 to .75. The newest version is CCTST Form 2000, and depending on the testing context, KR-20 alphas range from .78-.84.77

The Health Science Reasoning Test (HSRT)

Items within this inventory cover the domain of CT cognitive skills identified by a Delphi group of experts whose work resulted in the development of the CCTDI and CCTST. This test measures health science undergraduate and graduate students' CTS. Although test items are set in health sciences and clinical practice contexts, test takers are not required to have discipline-specific health sciences knowledge. For this reason, the test may have limited utility in dental education (78).

Preliminary estimates of internal consistency show that overall KR-20 coefficients range from .77 to .83.79 The instrument has moderate reliability on analysis and inference subscales, although the factor loadings appear adequate. The low K-20 coefficients may be result of small sample size, variance in item response, or both (see following table).

Table 8. Estimates of Internal Consistency and Factor Loading by Subscale for HSRT

Professional Judgment Rating Form (PJRF)

The scale consists of two sets of descriptors. The first set relates primarily to the attitudinal (habits of mind) dimension of CT. The second set relates primarily to CTS.

A single rater should know the student well enough to respond to at least 17 or the 20 descriptors with confidence. If not, the validity of the ratings may be questionable. If a single rater is used and ratings over time show some consistency, comparisons between ratings may be used to assess changes. If more than one rater is used, then inter-rater reliability must be established among the raters to yield meaningful results. While the PJRF can be used to assess the effectiveness of training programs for individuals or groups, the evaluation of participants' actual skills are best measured by an objective tool such as the California Critical Thinking Skills Test.

Teaching for Thinking Student Course Evaluation Form

Course evaluations typically ask for responses of "agree" or "disagree" to items focusing on teacher behavior. Typically the questions do not solicit information about student learning. Because contemporary thinking about curriculum is interested in student learning, this form was developed to address differences in pedagogy and subject matter, learning outcomes, student demographics, and course level characteristic of education today. This form also grew out of a "one size fits all" approach to teaching evaluations and a recognition of the limitations of this practice. It offers information about how a particular course enhances student knowledge, sensitivities, and dispositions. The form gives students an opportunity to provide feedback that can be used to improve instruction.

Holistic Critical Thinking Scoring Rubric

This assessment tool uses a four-point classification schema that lists particular opposing reasoning skills for select criteria. One advantage of a rubric is that it offers clearly delineated components and scales for evaluating outcomes. This rubric explains how students' CTS will be evaluated, and it provides a consistent framework for the professor as evaluator. Users can add or delete any of the statements to reflect their institution's effort to measure CT. Like most rubrics, this form is likely to have high face validity since the items tend to be relevant or descriptive of the target concept. This rubric can be used to rate student work or to assess learning outcomes. Experienced evaluators should engage in a process leading to consensus regarding what kinds of things should be classified and in what ways.80 If used improperly or by inexperienced evaluators, unreliable results may occur.

Peer Evaluation of Group Presentation Form

This form offers a common set of criteria to be used by peers and the instructor to evaluate student-led group presentations regarding concepts, analysis of arguments or positions, and conclusions.81 Users have an opportunity to rate the degree to which each component was demonstrated. Open-ended questions give users an opportunity to cite examples of how concepts, the analysis of arguments or positions, and conclusions were demonstrated.

Table 8. Proposed Universal Criteria for Evaluating Students' Critical Thinking Skills

Aside from the use of the above-mentioned assessment tools, Dexter et al. recommended that all schools develop universal criteria for evaluating students' development of critical thinking skills (82).

Their rationale for the proposed criteria is that if faculty give feedback using these criteria, graduates will internalize these skills and use them to monitor their own thinking and practice (see Table 4).

- Application Information

- ADEA GoDental

- ADEA AADSAS

- ADEA CAAPID

- Events & Professional Development

- Scholarships, Awards & Fellowships

- Publications & Data

- Official Guide to Dental Schools

- Data, Analysis & Research

- Follow Us On:

- ADEA Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Website Feedback

- Website Help

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, performance assessment of critical thinking: conceptualization, design, and implementation.

- 1 Lynch School of Education and Human Development, Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA, United States

- 2 Graduate School of Education, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

- 3 Department of Business and Economics Education, Johannes Gutenberg University, Mainz, Germany

Enhancing students’ critical thinking (CT) skills is an essential goal of higher education. This article presents a systematic approach to conceptualizing and measuring CT. CT generally comprises the following mental processes: identifying, evaluating, and analyzing a problem; interpreting information; synthesizing evidence; and reporting a conclusion. We further posit that CT also involves dealing with dilemmas involving ambiguity or conflicts among principles and contradictory information. We argue that performance assessment provides the most realistic—and most credible—approach to measuring CT. From this conceptualization and construct definition, we describe one possible framework for building performance assessments of CT with attention to extended performance tasks within the assessment system. The framework is a product of an ongoing, collaborative effort, the International Performance Assessment of Learning (iPAL). The framework comprises four main aspects: (1) The storyline describes a carefully curated version of a complex, real-world situation. (2) The challenge frames the task to be accomplished (3). A portfolio of documents in a range of formats is drawn from multiple sources chosen to have specific characteristics. (4) The scoring rubric comprises a set of scales each linked to a facet of the construct. We discuss a number of use cases, as well as the challenges that arise with the use and valid interpretation of performance assessments. The final section presents elements of the iPAL research program that involve various refinements and extensions of the assessment framework, a number of empirical studies, along with linkages to current work in online reading and information processing.

Introduction

In their mission statements, most colleges declare that a principal goal is to develop students’ higher-order cognitive skills such as critical thinking (CT) and reasoning (e.g., Shavelson, 2010 ; Hyytinen et al., 2019 ). The importance of CT is echoed by business leaders ( Association of American Colleges and Universities [AACU], 2018 ), as well as by college faculty (for curricular analyses in Germany, see e.g., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2018 ). Indeed, in the 2019 administration of the Faculty Survey of Student Engagement (FSSE), 93% of faculty reported that they “very much” or “quite a bit” structure their courses to support student development with respect to thinking critically and analytically. In a listing of 21st century skills, CT was the most highly ranked among FSSE respondents ( Indiana University, 2019 ). Nevertheless, there is considerable evidence that many college students do not develop these skills to a satisfactory standard ( Arum and Roksa, 2011 ; Shavelson et al., 2019 ; Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2019 ). This state of affairs represents a serious challenge to higher education – and to society at large.

In view of the importance of CT, as well as evidence of substantial variation in its development during college, its proper measurement is essential to tracking progress in skill development and to providing useful feedback to both teachers and learners. Feedback can help focus students’ attention on key skill areas in need of improvement, and provide insight to teachers on choices of pedagogical strategies and time allocation. Moreover, comparative studies at the program and institutional level can inform higher education leaders and policy makers.

The conceptualization and definition of CT presented here is closely related to models of information processing and online reasoning, the skills that are the focus of this special issue. These two skills are especially germane to the learning environments that college students experience today when much of their academic work is done online. Ideally, students should be capable of more than naïve Internet search, followed by copy-and-paste (e.g., McGrew et al., 2017 ); rather, for example, they should be able to critically evaluate both sources of evidence and the quality of the evidence itself in light of a given purpose ( Leu et al., 2020 ).

In this paper, we present a systematic approach to conceptualizing CT. From that conceptualization and construct definition, we present one possible framework for building performance assessments of CT with particular attention to extended performance tasks within the test environment. The penultimate section discusses some of the challenges that arise with the use and valid interpretation of performance assessment scores. We conclude the paper with a section on future perspectives in an emerging field of research – the iPAL program.

Conceptual Foundations, Definition and Measurement of Critical Thinking

In this section, we briefly review the concept of CT and its definition. In accordance with the principles of evidence-centered design (ECD; Mislevy et al., 2003 ), the conceptualization drives the measurement of the construct; that is, implementation of ECD directly links aspects of the assessment framework to specific facets of the construct. We then argue that performance assessments designed in accordance with such an assessment framework provide the most realistic—and most credible—approach to measuring CT. The section concludes with a sketch of an approach to CT measurement grounded in performance assessment .

Concept and Definition of Critical Thinking

Taxonomies of 21st century skills ( Pellegrino and Hilton, 2012 ) abound, and it is neither surprising that CT appears in most taxonomies of learning, nor that there are many different approaches to defining and operationalizing the construct of CT. There is, however, general agreement that CT is a multifaceted construct ( Liu et al., 2014 ). Liu et al. (2014) identified five key facets of CT: (i) evaluating evidence and the use of evidence; (ii) analyzing arguments; (iii) understanding implications and consequences; (iv) developing sound arguments; and (v) understanding causation and explanation.

There is empirical support for these facets from college faculty. A 2016–2017 survey conducted by the Higher Education Research Institute (HERI) at the University of California, Los Angeles found that a substantial majority of faculty respondents “frequently” encouraged students to: (i) evaluate the quality or reliability of the information they receive; (ii) recognize biases that affect their thinking; (iii) analyze multiple sources of information before coming to a conclusion; and (iv) support their opinions with a logical argument ( Stolzenberg et al., 2019 ).

There is general agreement that CT involves the following mental processes: identifying, evaluating, and analyzing a problem; interpreting information; synthesizing evidence; and reporting a conclusion (e.g., Erwin and Sebrell, 2003 ; Kosslyn and Nelson, 2017 ; Shavelson et al., 2018 ). We further suggest that CT includes dealing with dilemmas of ambiguity or conflict among principles and contradictory information ( Oser and Biedermann, 2020 ).

Importantly, Oser and Biedermann (2020) posit that CT can be manifested at three levels. The first level, Critical Analysis , is the most complex of the three levels. Critical Analysis requires both knowledge in a specific discipline (conceptual) and procedural analytical (deduction, inclusion, etc.) knowledge. The second level is Critical Reflection , which involves more generic skills “… necessary for every responsible member of a society” (p. 90). It is “a basic attitude that must be taken into consideration if (new) information is questioned to be true or false, reliable or not reliable, moral or immoral etc.” (p. 90). To engage in Critical Reflection, one needs not only apply analytic reasoning, but also adopt a reflective stance toward the political, social, and other consequences of choosing a course of action. It also involves analyzing the potential motives of various actors involved in the dilemma of interest. The third level, Critical Alertness , involves questioning one’s own or others’ thinking from a skeptical point of view.

Wheeler and Haertel (1993) categorized higher-order skills, such as CT, into two types: (i) when solving problems and making decisions in professional and everyday life, for instance, related to civic affairs and the environment; and (ii) in situations where various mental processes (e.g., comparing, evaluating, and justifying) are developed through formal instruction, usually in a discipline. Hence, in both settings, individuals must confront situations that typically involve a problematic event, contradictory information, and possibly conflicting principles. Indeed, there is an ongoing debate concerning whether CT should be evaluated using generic or discipline-based assessments ( Nagel et al., 2020 ). Whether CT skills are conceptualized as generic or discipline-specific has implications for how they are assessed and how they are incorporated into the classroom.

In the iPAL project, CT is characterized as a multifaceted construct that comprises conceptualizing, analyzing, drawing inferences or synthesizing information, evaluating claims, and applying the results of these reasoning processes to various purposes (e.g., solve a problem, decide on a course of action, find an answer to a given question or reach a conclusion) ( Shavelson et al., 2019 ). In the course of carrying out a CT task, an individual typically engages in activities such as specifying or clarifying a problem; deciding what information is relevant to the problem; evaluating the trustworthiness of information; avoiding judgmental errors based on “fast thinking”; avoiding biases and stereotypes; recognizing different perspectives and how they can reframe a situation; considering the consequences of alternative courses of actions; and communicating clearly and concisely decisions and actions. The order in which activities are carried out can vary among individuals and the processes can be non-linear and reciprocal.

In this article, we focus on generic CT skills. The importance of these skills derives not only from their utility in academic and professional settings, but also the many situations involving challenging moral and ethical issues – often framed in terms of conflicting principles and/or interests – to which individuals have to apply these skills ( Kegan, 1994 ; Tessier-Lavigne, 2020 ). Conflicts and dilemmas are ubiquitous in the contexts in which adults find themselves: work, family, civil society. Moreover, to remain viable in the global economic environment – one characterized by increased competition and advances in second generation artificial intelligence (AI) – today’s college students will need to continually develop and leverage their CT skills. Ideally, colleges offer a supportive environment in which students can develop and practice effective approaches to reasoning about and acting in learning, professional and everyday situations.

Measurement of Critical Thinking

Critical thinking is a multifaceted construct that poses many challenges to those who would develop relevant and valid assessments. For those interested in current approaches to the measurement of CT that are not the focus of this paper, consult Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al. (2018) .

In this paper, we have singled out performance assessment as it offers important advantages to measuring CT. Extant tests of CT typically employ response formats such as forced-choice or short-answer, and scenario-based tasks (for an overview, see Liu et al., 2014 ). They all suffer from moderate to severe construct underrepresentation; that is, they fail to capture important facets of the CT construct such as perspective taking and communication. High fidelity performance tasks are viewed as more authentic in that they provide a problem context and require responses that are more similar to what individuals confront in the real world than what is offered by traditional multiple-choice items ( Messick, 1994 ; Braun, 2019 ). This greater verisimilitude promises higher levels of construct representation and lower levels of construct-irrelevant variance. Such performance tasks have the capacity to measure facets of CT that are imperfectly assessed, if at all, using traditional assessments ( Lane and Stone, 2006 ; Braun, 2019 ; Shavelson et al., 2019 ). However, these assertions must be empirically validated, and the measures should be subjected to psychometric analyses. Evidence of the reliability, validity, and interpretative challenges of performance assessment (PA) are extensively detailed in Davey et al. (2015) .

We adopt the following definition of performance assessment:

A performance assessment (sometimes called a work sample when assessing job performance) … is an activity or set of activities that requires test takers, either individually or in groups, to generate products or performances in response to a complex, most often real-world task. These products and performances provide observable evidence bearing on test takers’ knowledge, skills, and abilities—their competencies—in completing the assessment ( Davey et al., 2015 , p. 10).

A performance assessment typically includes an extended performance task and short constructed-response and selected-response (i.e., multiple-choice) tasks (for examples, see Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia and Shavelson, 2019 ). In this paper, we refer to both individual performance- and constructed-response tasks as performance tasks (PT) (For an example, see Table 1 in section “iPAL Assessment Framework”).

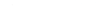

Table 1. The iPAL assessment framework.

An Approach to Performance Assessment of Critical Thinking: The iPAL Program

The approach to CT presented here is the result of ongoing work undertaken by the International Performance Assessment of Learning collaborative (iPAL 1 ). iPAL is an international consortium of volunteers, primarily from academia, who have come together to address the dearth in higher education of research and practice in measuring CT with performance tasks ( Shavelson et al., 2018 ). In this section, we present iPAL’s assessment framework as the basis of measuring CT, with examples along the way.

iPAL Background

The iPAL assessment framework builds on the Council of Aid to Education’s Collegiate Learning Assessment (CLA). The CLA was designed to measure cross-disciplinary, generic competencies, such as CT, analytic reasoning, problem solving, and written communication ( Klein et al., 2007 ; Shavelson, 2010 ). Ideally, each PA contained an extended PT (e.g., examining a range of evidential materials related to the crash of an aircraft) and two short PT’s: one in which students either critique an argument or provide a solution in response to a real-world societal issue.

Motivated by considerations of adequate reliability, in 2012, the CLA was later modified to create the CLA+. The CLA+ includes two subtests: a PT and a 25-item Selected Response Question (SRQ) section. The PT presents a document or problem statement and an assignment based on that document which elicits an open-ended response. The CLA+ added the SRQ section (which is not linked substantively to the PT scenario) to increase the number of student responses to obtain more reliable estimates of performance at the student-level than could be achieved with a single PT ( Zahner, 2013 ; Davey et al., 2015 ).

iPAL Assessment Framework

Methodological foundations.

The iPAL framework evolved from the Collegiate Learning Assessment developed by Klein et al. (2007) . It was also informed by the results from the AHELO pilot study ( Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2012 , 2013 ), as well as the KoKoHs research program in Germany (for an overview see, Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2017 , 2020 ). The ongoing refinement of the iPAL framework has been guided in part by the principles of Evidence Centered Design (ECD) ( Mislevy et al., 2003 ; Mislevy and Haertel, 2006 ; Haertel and Fujii, 2017 ).

In educational measurement, an assessment framework plays a critical intermediary role between the theoretical formulation of the construct and the development of the assessment instrument containing tasks (or items) intended to elicit evidence with respect to that construct ( Mislevy et al., 2003 ). Builders of the assessment framework draw on the construct theory and operationalize it in a way that provides explicit guidance to PT’s developers. Thus, the framework should reflect the relevant facets of the construct, where relevance is determined by substantive theory or an appropriate alternative such as behavioral samples from real-world situations of interest (criterion-sampling; McClelland, 1973 ), as well as the intended use(s) (for an example, see Shavelson et al., 2019 ). By following the requirements and guidelines embodied in the framework, instrument developers strengthen the claim of construct validity for the instrument ( Messick, 1994 ).

An assessment framework can be specified at different levels of granularity: an assessment battery (“omnibus” assessment, for an example see below), a single performance task, or a specific component of an assessment ( Shavelson, 2010 ; Davey et al., 2015 ). In the iPAL program, a performance assessment comprises one or more extended performance tasks and additional selected-response and short constructed-response items. The focus of the framework specified below is on a single PT intended to elicit evidence with respect to some facets of CT, such as the evaluation of the trustworthiness of the documents provided and the capacity to address conflicts of principles.

From the ECD perspective, an assessment is an instrument for generating information to support an evidentiary argument and, therefore, the intended inferences (claims) must guide each stage of the design process. The construct of interest is operationalized through the Student Model , which represents the target knowledge, skills, and abilities, as well as the relationships among them. The student model should also make explicit the assumptions regarding student competencies in foundational skills or content knowledge. The Task Model specifies the features of the problems or items posed to the respondent, with the goal of eliciting the evidence desired. The assessment framework also describes the collection of task models comprising the instrument, with considerations of construct validity, various psychometric characteristics (e.g., reliability) and practical constraints (e.g., testing time and cost). The student model provides grounds for evidence of validity, especially cognitive validity; namely, that the students are thinking critically in responding to the task(s).

In the present context, the target construct (CT) is the competence of individuals to think critically, which entails solving complex, real-world problems, and clearly communicating their conclusions or recommendations for action based on trustworthy, relevant and unbiased information. The situations, drawn from actual events, are challenging and may arise in many possible settings. In contrast to more reductionist approaches to assessment development, the iPAL approach and framework rests on the assumption that properly addressing these situational demands requires the application of a constellation of CT skills appropriate to the particular task presented (e.g., Shavelson, 2010 , 2013 ). For a PT, the assessment framework must also specify the rubric by which the responses will be evaluated. The rubric must be properly linked to the target construct so that the resulting score profile constitutes evidence that is both relevant and interpretable in terms of the student model (for an example, see Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2019 ).

iPAL Task Framework

The iPAL ‘omnibus’ framework comprises four main aspects: A storyline , a challenge , a document library , and a scoring rubric . Table 1 displays these aspects, brief descriptions of each, and the corresponding examples drawn from an iPAL performance assessment (Version adapted from original in Hyytinen and Toom, 2019 ). Storylines are drawn from various domains; for example, the worlds of business, public policy, civics, medicine, and family. They often involve moral and/or ethical considerations. Deriving an appropriate storyline from a real-world situation requires careful consideration of which features are to be kept in toto , which adapted for purposes of the assessment, and which to be discarded. Framing the challenge demands care in wording so that there is minimal ambiguity in what is required of the respondent. The difficulty of the challenge depends, in large part, on the nature and extent of the information provided in the document library , the amount of scaffolding included, as well as the scope of the required response. The amount of information and the scope of the challenge should be commensurate with the amount of time available. As is evident from the table, the characteristics of the documents in the library are intended to elicit responses related to facets of CT. For example, with regard to bias, the information provided is intended to play to judgmental errors due to fast thinking and/or motivational reasoning. Ideally, the situation should accommodate multiple solutions of varying degrees of merit.

The dimensions of the scoring rubric are derived from the Task Model and Student Model ( Mislevy et al., 2003 ) and signal which features are to be extracted from the response and indicate how they are to be evaluated. There should be a direct link between the evaluation of the evidence and the claims that are made with respect to the key features of the task model and student model . More specifically, the task model specifies the various manipulations embodied in the PA and so informs scoring, while the student model specifies the capacities students employ in more or less effectively responding to the tasks. The score scales for each of the five facets of CT (see section “Concept and Definition of Critical Thinking”) can be specified using appropriate behavioral anchors (for examples, see Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia and Shavelson, 2019 ). Of particular importance is the evaluation of the response with respect to the last dimension of the scoring rubric; namely, the overall coherence and persuasiveness of the argument, building on the explicit or implicit characteristics related to the first five dimensions. The scoring process must be monitored carefully to ensure that (trained) raters are judging each response based on the same types of features and evaluation criteria ( Braun, 2019 ) as indicated by interrater agreement coefficients.

The scoring rubric of the iPAL omnibus framework can be modified for specific tasks ( Lane and Stone, 2006 ). This generic rubric helps ensure consistency across rubrics for different storylines. For example, Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al. (2019 , p. 473) used the following scoring scheme:

Based on our construct definition of CT and its four dimensions: (D1-Info) recognizing and evaluating information, (D2-Decision) recognizing and evaluating arguments and making decisions, (D3-Conseq) recognizing and evaluating the consequences of decisions, and (D4-Writing), we developed a corresponding analytic dimensional scoring … The students’ performance is evaluated along the four dimensions, which in turn are subdivided into a total of 23 indicators as (sub)categories of CT … For each dimension, we sought detailed evidence in students’ responses for the indicators and scored them on a six-point Likert-type scale. In order to reduce judgment distortions, an elaborate procedure of ‘behaviorally anchored rating scales’ (Smith and Kendall, 1963) was applied by assigning concrete behavioral expectations to certain scale points (Bernardin et al., 1976). To this end, we defined the scale levels by short descriptions of typical behavior and anchored them with concrete examples. … We trained four raters in 1 day using a specially developed training course to evaluate students’ performance along the 23 indicators clustered into four dimensions (for a description of the rater training, see Klotzer, 2018).

Shavelson et al. (2019) examined the interrater agreement of the scoring scheme developed by Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al. (2019) and “found that with 23 items and 2 raters the generalizability (“reliability”) coefficient for total scores to be 0.74 (with 4 raters, 0.84)” ( Shavelson et al., 2019 , p. 15). In the study by Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al. (2019 , p. 478) three score profiles were identified (low-, middle-, and high-performer) for students. Proper interpretation of such profiles requires care. For example, there may be multiple possible explanations for low scores such as poor CT skills, a lack of a disposition to engage with the challenge, or the two attributes jointly. These alternative explanations for student performance can potentially pose a threat to the evidentiary argument. In this case, auxiliary information may be available to aid in resolving the ambiguity. For example, student responses to selected- and short-constructed-response items in the PA can provide relevant information about the levels of the different skills possessed by the student. When sufficient data are available, the scores can be modeled statistically and/or qualitatively in such a way as to bring them to bear on the technical quality or interpretability of the claims of the assessment: reliability, validity, and utility evidence ( Davey et al., 2015 ; Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia et al., 2019 ). These kinds of concerns are less critical when PT’s are used in classroom settings. The instructor can draw on other sources of evidence, including direct discussion with the student.

Use of iPAL Performance Assessments in Educational Practice: Evidence From Preliminary Validation Studies

The assessment framework described here supports the development of a PT in a general setting. Many modifications are possible and, indeed, desirable. If the PT is to be more deeply embedded in a certain discipline (e.g., economics, law, or medicine), for example, then the framework must specify characteristics of the narrative and the complementary documents as to the breadth and depth of disciplinary knowledge that is represented.

At present, preliminary field trials employing the omnibus framework (i.e., a full set of documents) indicated that 60 min was generally an inadequate amount of time for students to engage with the full set of complementary documents and to craft a complete response to the challenge (for an example, see Shavelson et al., 2019 ). Accordingly, it would be helpful to develop modified frameworks for PT’s that require substantially less time. For an example, see a short performance assessment of civic online reasoning, requiring response times from 10 to 50 min ( Wineburg et al., 2016 ). Such assessment frameworks could be derived from the omnibus framework by focusing on a reduced number of facets of CT, and specifying the characteristics of the complementary documents to be included – or, perhaps, choices among sets of documents. In principle, one could build a ‘family’ of PT’s, each using the same (or nearly the same) storyline and a subset of the full collection of complementary documents.