Research vs. Study

What's the difference.

Research and study are two essential components of the learning process, but they differ in their approach and purpose. Research involves a systematic investigation of a particular topic or issue, aiming to discover new knowledge or validate existing theories. It often involves collecting and analyzing data, conducting experiments, and drawing conclusions. On the other hand, study refers to the process of acquiring knowledge or understanding through reading, memorizing, and reviewing information. It is typically focused on a specific subject or discipline and aims to deepen one's understanding or mastery of that subject. While research is more exploratory and investigative, study is more focused on acquiring and retaining information. Both research and study are crucial for intellectual growth and expanding our knowledge base.

Further Detail

Introduction.

Research and study are two fundamental activities that play a crucial role in acquiring knowledge and understanding. While they share similarities, they also have distinct attributes that set them apart. In this article, we will explore the characteristics of research and study, highlighting their differences and similarities.

Definition and Purpose

Research is a systematic investigation aimed at discovering new knowledge, expanding existing knowledge, or solving specific problems. It involves gathering and analyzing data, formulating hypotheses, and drawing conclusions based on evidence. Research is often conducted in a structured and scientific manner, employing various methodologies and techniques.

On the other hand, study refers to the process of acquiring knowledge through reading, memorizing, and understanding information. It involves examining and learning from existing materials, such as textbooks, articles, or lectures. The purpose of study is to gain a comprehensive understanding of a particular subject or topic.

Approach and Methodology

Research typically follows a systematic approach, involving the formulation of research questions or hypotheses, designing experiments or surveys, collecting and analyzing data, and drawing conclusions. It often requires a rigorous methodology, including literature review, data collection, statistical analysis, and peer review. Research can be qualitative or quantitative, depending on the nature of the investigation.

Study, on the other hand, does not necessarily follow a specific methodology. It can be more flexible and personalized, allowing individuals to choose their own approach to learning. Study often involves reading and analyzing existing materials, taking notes, summarizing information, and engaging in discussions or self-reflection. While study can be structured, it is generally less formalized compared to research.

Scope and Depth

Research tends to have a broader scope and aims to contribute to the overall body of knowledge in a particular field. It often involves exploring new areas, pushing boundaries, and generating original insights. Research can be interdisciplinary, involving multiple disciplines and perspectives. The depth of research is often extensive, requiring in-depth analysis, critical thinking, and the ability to synthesize complex information.

Study, on the other hand, is usually more focused and specific. It aims to gain a comprehensive understanding of a particular subject or topic within an existing body of knowledge. Study can be deep and detailed, but it is often limited to the available resources and materials. While study may not contribute directly to the advancement of knowledge, it plays a crucial role in building a solid foundation of understanding.

Application and Output

Research is often driven by the desire to solve real-world problems or contribute to practical applications. The output of research can take various forms, including scientific papers, patents, policy recommendations, or technological advancements. Research findings are typically shared with the academic community and the public, aiming to advance knowledge and improve society.

Study, on the other hand, focuses more on personal development and learning. The application of study is often seen in academic settings, where individuals acquire knowledge to excel in their studies or careers. The output of study is usually reflected in improved understanding, enhanced critical thinking skills, and the ability to apply knowledge in practical situations.

Limitations and Challenges

Research faces several challenges, including limited resources, time constraints, ethical considerations, and the potential for bias. Conducting research requires careful planning, data collection, and analysis, which can be time-consuming and costly. Researchers must also navigate ethical guidelines and ensure the validity and reliability of their findings.

Study, on the other hand, may face challenges such as information overload, lack of motivation, or difficulty in finding reliable sources. It requires self-discipline, time management, and the ability to filter and prioritize information. Without proper guidance or structure, study can sometimes lead to superficial understanding or misconceptions.

In conclusion, research and study are both essential activities in the pursuit of knowledge and understanding. While research focuses on generating new knowledge and solving problems through a systematic approach, study aims to acquire and comprehend existing information. Research tends to be more formalized, rigorous, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge, while study is often more flexible, personalized, and focused on individual learning. Both research and study have their unique attributes and challenges, but together they form the foundation for intellectual growth and development.

Comparisons may contain inaccurate information about people, places, or facts. Please report any issues.

Home » Education » What is the Difference Between Research and Project

What is the Difference Between Research and Project

The main difference between research and project is that research is the systematic investigation and study of materials and sources to establish facts and reach new conclusions, while a project is a specific and finite activity that gives a measurable and observable result under preset requirements.

Both research and projects use a systematic approach. We also sometimes use the term research project to refer to research studies.

Key Areas Covered

1. What is Research – Definition, Features 2. What is a Project – Definition, Features 3. Difference Between Research and Project – Comparison of Key Differences

Research, Project

What is Research

Research is a careful study a researcher conducts using a systematic approach and scientific methods. A research study typically involves several components: abstract, introduction , literature review , research design, and method , results and analysis, conclusion, bibliography. Researchers usually begin a formal research study with a hypothesis; then, they test this hypothesis rigorously. They also explore and analyze the literature already available on their research subject. This allows them to study the research subject from multiple perspectives, acknowledging different problems that need to be solved.

There are different types of research, the main two categories being quantitative research and qualitative research. Depending on their research method and design, we can also categorize research as descriptive research, exploratory research, longitudinal research, cross-sectional research, etc.

Furthermore, research should always be objective or unbiased. Moreover, if the research involves participants, for example, in surveys or interviews, the researcher should always make sure to obtain their written consent first.

What is a Project

A project is a collaborative or individual enterprise that is carefully planned to achieve a particular aim. We can also describe it as a specific and finite activity that gives a measurable and observable result under preset requirements. This result can be tangible or intangible; for example, product, service, competitive advantage, etc. A project generally involves a series of connected tasks planned for execution over a fixed period of time and within certain limitations like quality and cost. The Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK) defines a project as a “temporary endeavor with a beginning and an end, and it must be used to create a unique product, service or result.”

Difference Between Research and Project

Research is a careful study conducted using a systematic approach and scientific methods, whereas a project is a collaborative or individual enterprise that is carefully planned to achieve a particular aim.

Research studies are mainly carried out in academia, while projects can be seen in a variety of contexts, including businesses.

The main aim of the research is to seek or revise facts, theories, or principles, while the main aim of a project is to achieve a tangible or intangible result; for example, product, service, competitive advantage, etc.

The main difference between research and project is that research is the systematic investigation and study of materials and sources to establish facts and reach new conclusions, while the project is a specific and finite activity that gives a measurable and observable result under preset requirements.

1. “ What Is a Project? – Definition, Lifecycle and Key Characteristics .” Your Guide to Project Management Best Practices .

Image Courtesy:

1. “ Research ” by Nick Youngson (CC BY-SA 3.0) via The Blue Diamond Gallery 2. “ Project-group-team-feedback ” (CC0) via Pixabay

About the Author: Hasa

Hasanthi is a seasoned content writer and editor with over 8 years of experience. Armed with a BA degree in English and a knack for digital marketing, she explores her passions for literature, history, culture, and food through her engaging and informative writing.

You May Also Like These

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 20). Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 7 June 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Dissertation vs Thesis vs Capstone Project What’s the difference?

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewed By: Dr. Eunice Rautenbach | October 2020

At Grad Coach, we receive questions about dissertation and thesis writing on a daily basis – everything from how to find a good research topic to which research methods to use and how to analyse the data.

One of the most common questions we receive is “what’s the difference between a dissertation and thesis?” . If you look around online, you’ll find a lot of confusing and often contrasting answers. In this post we’ll clear it up, once and for all…

Need a helping hand?

Dissertation vs Thesis: Showdown Time

Before comparing dissertations to theses, it’s useful to first understand what both of these are and what they have in common .

Dissertations and theses are both formal academic research projects . In other words, they’re academic projects that involve you undertaking research in a structured, systematic way. The research process typically involves the following steps :

- Asking a well-articulated and meaningful research question (or questions).

- Assessing what other researchers have said in relation to that question (this is usually called a literature review – you can learn more about that up here).

- Undertaking your own research using a clearly justified methodology – this often involves some sort of fieldwork such as interviews or surveys – and lastly,

- Deriving an answer to your research question based on your analysis.

In other words, theses and dissertations are both formal, structured research projects that involve using a clearly articulated methodology to draw out insights and answers to your research questions . So, in this respect, they are, for the most part, the same thing.

But, how are they different then?

Well, the key difference between a dissertation and a thesis is, for the most part, the level of study – in other words, undergrad, master or PhD. By extension, this also means that the complexity and rigorousness of the research differs between dissertations and theses.

So, which is which?

This is where it gets a bit confusing. The meaning of dissertation or thesis varies depending on the country or region of study. For example, in the UK, a dissertation is generally a research project that’s completed at the end of a Masters-level degree, whereas a thesis is completed for a Doctoral-level degree.

Conversely, the terminology is flipped around in the US (and some other countries). In other words, a thesis is completed for a Masters-level degree, while a dissertation is completed for PhD (or any other doctoral-level degree).

Simply put, a dissertation and a thesis are essentially the same thing, but at different levels of study . The exact terminology varies from country to country, and sometimes it even varies between universities in the same country. Some universities will also refer to this type of project as a capstone project . In addition, some universities will also require an oral exam or viva voce , especially for doctoral-level projects.

Given that there are more than 25,000 universities scattered across the globe, all of this terminological complexity can cause some confusion. To be safe, make sure that you thoroughly read the brief provided by your university for your dissertation or thesis, and if possible, visit the university library to have a look at past students’ projects . This will help you get a feel for your institution’s norms and spot any nuances in terms of their specific requirements so that you can give them exactly what they want.

Let’s recap

Dissertations and theses are both formal academic research projects . The main difference is the level of study – undergrad, Masters or PhD. Terminology tends to vary from country to country, and even within countries.

Need help with your research project?

Get in touch with a friendly Grad Coach to discuss how we can help you fast-track your dissertation or thesis today. Book a free, no-obligation consultation here.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

GRADCOACH youtube and materials are awesome for new researchers. Keep posting such materials so that many new researchers can benefit form them.

Am happy to be part of the family hope you will help me with more information through my email

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is Research Methodology? Simple Definition (With Examples) - Grad Coach - […] you’ve started working on your first piece of formal research – be it a dissertation, thesis or research project…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Please log in to save materials. Log in

What'S The Difference Between A Project And A Research Project?

Be sure to read previous customer reviews and compare prices before making your decision. You can check the services offered, pricing policy, terms, reviews and guarantees. In addition, you can use the provided lists of the best services to get detailed information on guarantees, pricing policy, quality of documents, as well as see real reviews and reviews. It is always important to work with legal services that can guarantee maximum confidentiality and no plagiarism in documents. To get a perfectly written online document, you need to hire the best online writing assistance company. There are many great online services to help you write your essay quickly and efficiently. Start by reading reviews and find several article writing websites to check them out.

best essay writing service reviews 2022

However, the main difference is that while an academic research proposal is for a specific line of research, a project proposal is for approval of a relatively smaller enterprise or scientific scheme; most often, project proposals are written with the intent of obtaining support in the form of budget penalties and permission to devote time and effort to the chosen project. Here it must be remembered that the forms, procedures and principles of academic research proposals are much more rigorous than for project proposals; it goes without saying that even the standard is much more demanding than in the project proposals.

While format, length, and content may vary, the overall goal of academic research proposals and project proposals remains the same: approval by supervisors, academic committees, or reviews . This article will discuss the complexities of academic research proposals and project proposals, thereby helping readers understand the differences between the two. The following steps describe a simple and effective research paper writing strategy. You will most likely start your research with a working, preliminary, or preliminary thesis, which you will refine until you are sure where the evidence leads. The thesis says what you believe and what you are going to prove. Good thesis statement distinguishes a thoughtful research project from a mere review of the facts. A good experimental thesis will help you focus your search for information.

Before embarking on serious research, do some preliminary research to determine if there is enough information for your needs and to set the context for your research. Now that the direction of your research is clear to you, you can start searching for material on your topic. Choose a topic on which you can find an acceptable amount of information. People wishing to publish the results of a quality assurance project should read this guide. Worksheets for assessing whether a quality assurance activity is also exploratory The following are two worksheets to help researchers determine whether to consult with the IRB before starting a quality assurance project.

The main similarity between a thesis and a research project is that both can be inserted as academic papers. To understand the difference between a thesis and a research project, it is necessary to understand the similarities between the two terms. A dissertation is much more thorough than a research project; is a collection of various studies carried out in the field of study, which includes a critical analysis of their results. It aims to present and justify the necessity and importance of conducting research, as well as to present practical ways of conducting research. In addition, he should discuss the main issues and questions that the researcher will raise during the course of the study. Take on a topic that can be adequately covered in the given project format. A strong thesis is provocative; takes a stand and justifies the discussion you present.

It contains the introduction, problematic hypothesis, objectives, hypothesis, methodology, rationale, and implications of the research project. The information collected during the study culminates in an application document such as policy recommendations, curriculum development, or program evaluation. The purpose of a design study is to collect information that will help solve an identifiable problem in a specific context. The purpose of design research is not to add to our understanding of research on a topic. The key difference between design research and a dissertation is that design research does not start from a research problem. The main difference between a terminating project and a thesis is that a terminating project addresses a specific problem, problem, or problem in your field of study, while a dissertation attempts to create new knowledge. The final project focuses on a narrow and specific topic, while the dissertation addresses a broader and more general issue.

The main difference between projects and programs is usually that projects are designed to produce results while programs are designed to achieve business results. Obviously, there are some similarities between projects and programs, namely that they are both interested in change, i.e., in creating something new, and both require the use of a team to achieve a goal. To make the difference between project and programme more concrete, let's look at a practical example of the difference between project and programme. But to understand the difference, you need to start by understanding the definitions of projects and programmes. In a project portfolio, each project is responsible for managing multiple projects. The figure also highlights the differences between the project management level and the program and portfolio.

Program Managers Project Managers Program Managers create the overall plans that are used to manage projects. Project management has a defined timeline with a defined deliverable that determines the end date. The program manager defines the vision, which is especially important when he oversees several projects at the same time. Program managers need to think strategically, especially as they often have to negotiate between different organizations and sometimes between multiple projects interacting over a program. Indeed, some of these projects can be so large and complex that they are programs in their own right. Thus, our software projects will only be one of the projects controlled by the program. Project Report Research Report Mainly focuses on achieving the desired outcome of the project. The focus is on providing information derived from data and problem analysis. A project report, as the name suggests, is simply a report that provides useful and important information to make better business decisions and also helps in project management.

Conversely, a research report defines what is being sought, sources of data collection, how data is collected (for example, a research report focuses on the results of a completed research work. The research proposal has been submitted, evaluated, taking into account a number of factors, such as the associated costs , potential impact, soundness of the project implementation plan This is usually a request for research funding on the subject of study. Instead, the research report is prepared after the project is completed. The research proposal is written in the future, the time used in the research report is past because it is written in the third person. Research proposals are approximately 4-10 pages in length. On the other hand, research consists of proving the main thesis backed up by evidence and data. Originality and personal research are important components of a dissertation. This dissertation engages the student in stimulating or provocative research and shows a level of thinking that opens up new horizons. Researching and writing an article will be more enjoyable if you are writing about something interesting.

Source: https://www.thenewsminute.com/article/top-5-best-essay-writing-service-reviews-comparative-study-167031

https://www.we-heart.com/2022/08/30/5-best-personal-statement-writing-services/

- Language Editing For Manuscripts For Response Letter new For LaTeX For Annual Review and Tenure For Books new

- Scientific Editing For Manuscripts For Response Letter new

- Grant Editing

- Translation

- Publication Support Journal Recommendation Manuscript Formatting Figure Formatting Data Analysis new Plagiarism Check Conference Poster Plain Language Summary

- Scientific Illustration Journal Cover Design Graphical Abstract Infographic Custom Illustration

- Scientific Videos Video Abstract Explainer Video Scientific Animation

- Ethics and Confidentiality

- Editorial Certificate

- Testimonials

- Design Gallery

- Institutional Provider

- Publisher Portal

- Brand Localization

- Journal Selector Tool

- Learning Nexus

Research vs. study

The confusion about these words is that they can both be either nouns or verbs. If you ask someone, "Does 'studies' mean the same as 'researches'?" you may hear "Yes," but it is only true if they are used as verbs. As nouns, they have subtly different meanings.

"This team has done a lot of good research. I just read their latest study, which they wrote about calcium in germinating soybeans. It described several interesting experiments."

research 1. to perform a systematic investigation

1. "What kind of scientist is he? He's a botanist. He researches plants."

study 1. to perform a systematic investigation; 2. to actively learn or memorize academic material

1. "What kind of scientist is he? He's a botanist. He studies plants."

2. "Mindy studies every day. That is why she gets such excellent grades. She wants to go to college to study math."

Some authors say "research" when they mean "study." "Research," as a verb, means "to perform a study or studies," but "research" as a noun refers to the sum of many studies. "Chemical research" means the sum of all chemical studies. If you find yourself writing "a research" or "in this research," change it to "a study" or "in this study."

research The act of performing research. Also, the results of research. Note that "research" is a mass noun. It is already plural in meaning but grammatically singular. If you want to indicate more than one type, say "bodies of research" or "pieces of research," not "researches."

"Dr. Lee was a prolific scientist. She performed a great deal of research over her long career."

study A single research project or paper.

"Dr. Lee was a prolific scientist. She performed a great many studies over her long career."

The noun "study" refers to a single paper or project. You can replace "paper" with "study" in almost all cases (but not always the other way around), to the point where you can say "I wrote a study." The noun "research" means more like a whole body of research including many individual studies: The research of a field. The lifetime achievements of a scientist or research team.

Quick Links

- Language Editing Service

- Expert Scientific Editing Service

- Professional Translation Service

- Formatting Service

- Figure Preparation Service

Intentional Space Tag

Contact us

Your name *

Your email *

Your message *

Please fill in all fields and provide a valid email.

© 2010-2024 ACCDON LLC 400 5 th Ave, Suite 530, Waltham, MA 02451, USA Privacy • Terms of Service

© 2010-2024 United States: ACCDON LLC Tel: 1-781-202-9968 Email: [email protected]

Address: 400 5 th Ave, Suite 530, Waltham, Massachusetts 02451, United States

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Korean Med Sci

- v.37(16); 2022 Apr 25

A Practical Guide to Writing Quantitative and Qualitative Research Questions and Hypotheses in Scholarly Articles

Edward barroga.

1 Department of General Education, Graduate School of Nursing Science, St. Luke’s International University, Tokyo, Japan.

Glafera Janet Matanguihan

2 Department of Biological Sciences, Messiah University, Mechanicsburg, PA, USA.

The development of research questions and the subsequent hypotheses are prerequisites to defining the main research purpose and specific objectives of a study. Consequently, these objectives determine the study design and research outcome. The development of research questions is a process based on knowledge of current trends, cutting-edge studies, and technological advances in the research field. Excellent research questions are focused and require a comprehensive literature search and in-depth understanding of the problem being investigated. Initially, research questions may be written as descriptive questions which could be developed into inferential questions. These questions must be specific and concise to provide a clear foundation for developing hypotheses. Hypotheses are more formal predictions about the research outcomes. These specify the possible results that may or may not be expected regarding the relationship between groups. Thus, research questions and hypotheses clarify the main purpose and specific objectives of the study, which in turn dictate the design of the study, its direction, and outcome. Studies developed from good research questions and hypotheses will have trustworthy outcomes with wide-ranging social and health implications.

INTRODUCTION

Scientific research is usually initiated by posing evidenced-based research questions which are then explicitly restated as hypotheses. 1 , 2 The hypotheses provide directions to guide the study, solutions, explanations, and expected results. 3 , 4 Both research questions and hypotheses are essentially formulated based on conventional theories and real-world processes, which allow the inception of novel studies and the ethical testing of ideas. 5 , 6

It is crucial to have knowledge of both quantitative and qualitative research 2 as both types of research involve writing research questions and hypotheses. 7 However, these crucial elements of research are sometimes overlooked; if not overlooked, then framed without the forethought and meticulous attention it needs. Planning and careful consideration are needed when developing quantitative or qualitative research, particularly when conceptualizing research questions and hypotheses. 4

There is a continuing need to support researchers in the creation of innovative research questions and hypotheses, as well as for journal articles that carefully review these elements. 1 When research questions and hypotheses are not carefully thought of, unethical studies and poor outcomes usually ensue. Carefully formulated research questions and hypotheses define well-founded objectives, which in turn determine the appropriate design, course, and outcome of the study. This article then aims to discuss in detail the various aspects of crafting research questions and hypotheses, with the goal of guiding researchers as they develop their own. Examples from the authors and peer-reviewed scientific articles in the healthcare field are provided to illustrate key points.

DEFINITIONS AND RELATIONSHIP OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

A research question is what a study aims to answer after data analysis and interpretation. The answer is written in length in the discussion section of the paper. Thus, the research question gives a preview of the different parts and variables of the study meant to address the problem posed in the research question. 1 An excellent research question clarifies the research writing while facilitating understanding of the research topic, objective, scope, and limitations of the study. 5

On the other hand, a research hypothesis is an educated statement of an expected outcome. This statement is based on background research and current knowledge. 8 , 9 The research hypothesis makes a specific prediction about a new phenomenon 10 or a formal statement on the expected relationship between an independent variable and a dependent variable. 3 , 11 It provides a tentative answer to the research question to be tested or explored. 4

Hypotheses employ reasoning to predict a theory-based outcome. 10 These can also be developed from theories by focusing on components of theories that have not yet been observed. 10 The validity of hypotheses is often based on the testability of the prediction made in a reproducible experiment. 8

Conversely, hypotheses can also be rephrased as research questions. Several hypotheses based on existing theories and knowledge may be needed to answer a research question. Developing ethical research questions and hypotheses creates a research design that has logical relationships among variables. These relationships serve as a solid foundation for the conduct of the study. 4 , 11 Haphazardly constructed research questions can result in poorly formulated hypotheses and improper study designs, leading to unreliable results. Thus, the formulations of relevant research questions and verifiable hypotheses are crucial when beginning research. 12

CHARACTERISTICS OF GOOD RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Excellent research questions are specific and focused. These integrate collective data and observations to confirm or refute the subsequent hypotheses. Well-constructed hypotheses are based on previous reports and verify the research context. These are realistic, in-depth, sufficiently complex, and reproducible. More importantly, these hypotheses can be addressed and tested. 13

There are several characteristics of well-developed hypotheses. Good hypotheses are 1) empirically testable 7 , 10 , 11 , 13 ; 2) backed by preliminary evidence 9 ; 3) testable by ethical research 7 , 9 ; 4) based on original ideas 9 ; 5) have evidenced-based logical reasoning 10 ; and 6) can be predicted. 11 Good hypotheses can infer ethical and positive implications, indicating the presence of a relationship or effect relevant to the research theme. 7 , 11 These are initially developed from a general theory and branch into specific hypotheses by deductive reasoning. In the absence of a theory to base the hypotheses, inductive reasoning based on specific observations or findings form more general hypotheses. 10

TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions and hypotheses are developed according to the type of research, which can be broadly classified into quantitative and qualitative research. We provide a summary of the types of research questions and hypotheses under quantitative and qualitative research categories in Table 1 .

Research questions in quantitative research

In quantitative research, research questions inquire about the relationships among variables being investigated and are usually framed at the start of the study. These are precise and typically linked to the subject population, dependent and independent variables, and research design. 1 Research questions may also attempt to describe the behavior of a population in relation to one or more variables, or describe the characteristics of variables to be measured ( descriptive research questions ). 1 , 5 , 14 These questions may also aim to discover differences between groups within the context of an outcome variable ( comparative research questions ), 1 , 5 , 14 or elucidate trends and interactions among variables ( relationship research questions ). 1 , 5 We provide examples of descriptive, comparative, and relationship research questions in quantitative research in Table 2 .

Hypotheses in quantitative research

In quantitative research, hypotheses predict the expected relationships among variables. 15 Relationships among variables that can be predicted include 1) between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable ( simple hypothesis ) or 2) between two or more independent and dependent variables ( complex hypothesis ). 4 , 11 Hypotheses may also specify the expected direction to be followed and imply an intellectual commitment to a particular outcome ( directional hypothesis ) 4 . On the other hand, hypotheses may not predict the exact direction and are used in the absence of a theory, or when findings contradict previous studies ( non-directional hypothesis ). 4 In addition, hypotheses can 1) define interdependency between variables ( associative hypothesis ), 4 2) propose an effect on the dependent variable from manipulation of the independent variable ( causal hypothesis ), 4 3) state a negative relationship between two variables ( null hypothesis ), 4 , 11 , 15 4) replace the working hypothesis if rejected ( alternative hypothesis ), 15 explain the relationship of phenomena to possibly generate a theory ( working hypothesis ), 11 5) involve quantifiable variables that can be tested statistically ( statistical hypothesis ), 11 6) or express a relationship whose interlinks can be verified logically ( logical hypothesis ). 11 We provide examples of simple, complex, directional, non-directional, associative, causal, null, alternative, working, statistical, and logical hypotheses in quantitative research, as well as the definition of quantitative hypothesis-testing research in Table 3 .

Research questions in qualitative research

Unlike research questions in quantitative research, research questions in qualitative research are usually continuously reviewed and reformulated. The central question and associated subquestions are stated more than the hypotheses. 15 The central question broadly explores a complex set of factors surrounding the central phenomenon, aiming to present the varied perspectives of participants. 15

There are varied goals for which qualitative research questions are developed. These questions can function in several ways, such as to 1) identify and describe existing conditions ( contextual research question s); 2) describe a phenomenon ( descriptive research questions ); 3) assess the effectiveness of existing methods, protocols, theories, or procedures ( evaluation research questions ); 4) examine a phenomenon or analyze the reasons or relationships between subjects or phenomena ( explanatory research questions ); or 5) focus on unknown aspects of a particular topic ( exploratory research questions ). 5 In addition, some qualitative research questions provide new ideas for the development of theories and actions ( generative research questions ) or advance specific ideologies of a position ( ideological research questions ). 1 Other qualitative research questions may build on a body of existing literature and become working guidelines ( ethnographic research questions ). Research questions may also be broadly stated without specific reference to the existing literature or a typology of questions ( phenomenological research questions ), may be directed towards generating a theory of some process ( grounded theory questions ), or may address a description of the case and the emerging themes ( qualitative case study questions ). 15 We provide examples of contextual, descriptive, evaluation, explanatory, exploratory, generative, ideological, ethnographic, phenomenological, grounded theory, and qualitative case study research questions in qualitative research in Table 4 , and the definition of qualitative hypothesis-generating research in Table 5 .

Qualitative studies usually pose at least one central research question and several subquestions starting with How or What . These research questions use exploratory verbs such as explore or describe . These also focus on one central phenomenon of interest, and may mention the participants and research site. 15

Hypotheses in qualitative research

Hypotheses in qualitative research are stated in the form of a clear statement concerning the problem to be investigated. Unlike in quantitative research where hypotheses are usually developed to be tested, qualitative research can lead to both hypothesis-testing and hypothesis-generating outcomes. 2 When studies require both quantitative and qualitative research questions, this suggests an integrative process between both research methods wherein a single mixed-methods research question can be developed. 1

FRAMEWORKS FOR DEVELOPING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

Research questions followed by hypotheses should be developed before the start of the study. 1 , 12 , 14 It is crucial to develop feasible research questions on a topic that is interesting to both the researcher and the scientific community. This can be achieved by a meticulous review of previous and current studies to establish a novel topic. Specific areas are subsequently focused on to generate ethical research questions. The relevance of the research questions is evaluated in terms of clarity of the resulting data, specificity of the methodology, objectivity of the outcome, depth of the research, and impact of the study. 1 , 5 These aspects constitute the FINER criteria (i.e., Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, and Relevant). 1 Clarity and effectiveness are achieved if research questions meet the FINER criteria. In addition to the FINER criteria, Ratan et al. described focus, complexity, novelty, feasibility, and measurability for evaluating the effectiveness of research questions. 14

The PICOT and PEO frameworks are also used when developing research questions. 1 The following elements are addressed in these frameworks, PICOT: P-population/patients/problem, I-intervention or indicator being studied, C-comparison group, O-outcome of interest, and T-timeframe of the study; PEO: P-population being studied, E-exposure to preexisting conditions, and O-outcome of interest. 1 Research questions are also considered good if these meet the “FINERMAPS” framework: Feasible, Interesting, Novel, Ethical, Relevant, Manageable, Appropriate, Potential value/publishable, and Systematic. 14

As we indicated earlier, research questions and hypotheses that are not carefully formulated result in unethical studies or poor outcomes. To illustrate this, we provide some examples of ambiguous research question and hypotheses that result in unclear and weak research objectives in quantitative research ( Table 6 ) 16 and qualitative research ( Table 7 ) 17 , and how to transform these ambiguous research question(s) and hypothesis(es) into clear and good statements.

a These statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

b These statements are direct quotes from Higashihara and Horiuchi. 16

a This statement is a direct quote from Shimoda et al. 17

The other statements were composed for comparison and illustrative purposes only.

CONSTRUCTING RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

To construct effective research questions and hypotheses, it is very important to 1) clarify the background and 2) identify the research problem at the outset of the research, within a specific timeframe. 9 Then, 3) review or conduct preliminary research to collect all available knowledge about the possible research questions by studying theories and previous studies. 18 Afterwards, 4) construct research questions to investigate the research problem. Identify variables to be accessed from the research questions 4 and make operational definitions of constructs from the research problem and questions. Thereafter, 5) construct specific deductive or inductive predictions in the form of hypotheses. 4 Finally, 6) state the study aims . This general flow for constructing effective research questions and hypotheses prior to conducting research is shown in Fig. 1 .

Research questions are used more frequently in qualitative research than objectives or hypotheses. 3 These questions seek to discover, understand, explore or describe experiences by asking “What” or “How.” The questions are open-ended to elicit a description rather than to relate variables or compare groups. The questions are continually reviewed, reformulated, and changed during the qualitative study. 3 Research questions are also used more frequently in survey projects than hypotheses in experiments in quantitative research to compare variables and their relationships.

Hypotheses are constructed based on the variables identified and as an if-then statement, following the template, ‘If a specific action is taken, then a certain outcome is expected.’ At this stage, some ideas regarding expectations from the research to be conducted must be drawn. 18 Then, the variables to be manipulated (independent) and influenced (dependent) are defined. 4 Thereafter, the hypothesis is stated and refined, and reproducible data tailored to the hypothesis are identified, collected, and analyzed. 4 The hypotheses must be testable and specific, 18 and should describe the variables and their relationships, the specific group being studied, and the predicted research outcome. 18 Hypotheses construction involves a testable proposition to be deduced from theory, and independent and dependent variables to be separated and measured separately. 3 Therefore, good hypotheses must be based on good research questions constructed at the start of a study or trial. 12

In summary, research questions are constructed after establishing the background of the study. Hypotheses are then developed based on the research questions. Thus, it is crucial to have excellent research questions to generate superior hypotheses. In turn, these would determine the research objectives and the design of the study, and ultimately, the outcome of the research. 12 Algorithms for building research questions and hypotheses are shown in Fig. 2 for quantitative research and in Fig. 3 for qualitative research.

EXAMPLES OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS FROM PUBLISHED ARTICLES

- EXAMPLE 1. Descriptive research question (quantitative research)

- - Presents research variables to be assessed (distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes)

- “BACKGROUND: Since COVID-19 was identified, its clinical and biological heterogeneity has been recognized. Identifying COVID-19 phenotypes might help guide basic, clinical, and translational research efforts.

- RESEARCH QUESTION: Does the clinical spectrum of patients with COVID-19 contain distinct phenotypes and subphenotypes? ” 19

- EXAMPLE 2. Relationship research question (quantitative research)

- - Shows interactions between dependent variable (static postural control) and independent variable (peripheral visual field loss)

- “Background: Integration of visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive sensations contributes to postural control. People with peripheral visual field loss have serious postural instability. However, the directional specificity of postural stability and sensory reweighting caused by gradual peripheral visual field loss remain unclear.

- Research question: What are the effects of peripheral visual field loss on static postural control ?” 20

- EXAMPLE 3. Comparative research question (quantitative research)

- - Clarifies the difference among groups with an outcome variable (patients enrolled in COMPERA with moderate PH or severe PH in COPD) and another group without the outcome variable (patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH))

- “BACKGROUND: Pulmonary hypertension (PH) in COPD is a poorly investigated clinical condition.

- RESEARCH QUESTION: Which factors determine the outcome of PH in COPD?

- STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS: We analyzed the characteristics and outcome of patients enrolled in the Comparative, Prospective Registry of Newly Initiated Therapies for Pulmonary Hypertension (COMPERA) with moderate or severe PH in COPD as defined during the 6th PH World Symposium who received medical therapy for PH and compared them with patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension (IPAH) .” 21

- EXAMPLE 4. Exploratory research question (qualitative research)

- - Explores areas that have not been fully investigated (perspectives of families and children who receive care in clinic-based child obesity treatment) to have a deeper understanding of the research problem

- “Problem: Interventions for children with obesity lead to only modest improvements in BMI and long-term outcomes, and data are limited on the perspectives of families of children with obesity in clinic-based treatment. This scoping review seeks to answer the question: What is known about the perspectives of families and children who receive care in clinic-based child obesity treatment? This review aims to explore the scope of perspectives reported by families of children with obesity who have received individualized outpatient clinic-based obesity treatment.” 22

- EXAMPLE 5. Relationship research question (quantitative research)

- - Defines interactions between dependent variable (use of ankle strategies) and independent variable (changes in muscle tone)

- “Background: To maintain an upright standing posture against external disturbances, the human body mainly employs two types of postural control strategies: “ankle strategy” and “hip strategy.” While it has been reported that the magnitude of the disturbance alters the use of postural control strategies, it has not been elucidated how the level of muscle tone, one of the crucial parameters of bodily function, determines the use of each strategy. We have previously confirmed using forward dynamics simulations of human musculoskeletal models that an increased muscle tone promotes the use of ankle strategies. The objective of the present study was to experimentally evaluate a hypothesis: an increased muscle tone promotes the use of ankle strategies. Research question: Do changes in the muscle tone affect the use of ankle strategies ?” 23

EXAMPLES OF HYPOTHESES IN PUBLISHED ARTICLES

- EXAMPLE 1. Working hypothesis (quantitative research)

- - A hypothesis that is initially accepted for further research to produce a feasible theory

- “As fever may have benefit in shortening the duration of viral illness, it is plausible to hypothesize that the antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen may be hindering the benefits of a fever response when taken during the early stages of COVID-19 illness .” 24

- “In conclusion, it is plausible to hypothesize that the antipyretic efficacy of ibuprofen may be hindering the benefits of a fever response . The difference in perceived safety of these agents in COVID-19 illness could be related to the more potent efficacy to reduce fever with ibuprofen compared to acetaminophen. Compelling data on the benefit of fever warrant further research and review to determine when to treat or withhold ibuprofen for early stage fever for COVID-19 and other related viral illnesses .” 24

- EXAMPLE 2. Exploratory hypothesis (qualitative research)

- - Explores particular areas deeper to clarify subjective experience and develop a formal hypothesis potentially testable in a future quantitative approach

- “We hypothesized that when thinking about a past experience of help-seeking, a self distancing prompt would cause increased help-seeking intentions and more favorable help-seeking outcome expectations .” 25

- “Conclusion

- Although a priori hypotheses were not supported, further research is warranted as results indicate the potential for using self-distancing approaches to increasing help-seeking among some people with depressive symptomatology.” 25

- EXAMPLE 3. Hypothesis-generating research to establish a framework for hypothesis testing (qualitative research)

- “We hypothesize that compassionate care is beneficial for patients (better outcomes), healthcare systems and payers (lower costs), and healthcare providers (lower burnout). ” 26

- Compassionomics is the branch of knowledge and scientific study of the effects of compassionate healthcare. Our main hypotheses are that compassionate healthcare is beneficial for (1) patients, by improving clinical outcomes, (2) healthcare systems and payers, by supporting financial sustainability, and (3) HCPs, by lowering burnout and promoting resilience and well-being. The purpose of this paper is to establish a scientific framework for testing the hypotheses above . If these hypotheses are confirmed through rigorous research, compassionomics will belong in the science of evidence-based medicine, with major implications for all healthcare domains.” 26

- EXAMPLE 4. Statistical hypothesis (quantitative research)

- - An assumption is made about the relationship among several population characteristics ( gender differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adults with ADHD ). Validity is tested by statistical experiment or analysis ( chi-square test, Students t-test, and logistic regression analysis)

- “Our research investigated gender differences in sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of adults with ADHD in a Japanese clinical sample. Due to unique Japanese cultural ideals and expectations of women's behavior that are in opposition to ADHD symptoms, we hypothesized that women with ADHD experience more difficulties and present more dysfunctions than men . We tested the following hypotheses: first, women with ADHD have more comorbidities than men with ADHD; second, women with ADHD experience more social hardships than men, such as having less full-time employment and being more likely to be divorced.” 27

- “Statistical Analysis

- ( text omitted ) Between-gender comparisons were made using the chi-squared test for categorical variables and Students t-test for continuous variables…( text omitted ). A logistic regression analysis was performed for employment status, marital status, and comorbidity to evaluate the independent effects of gender on these dependent variables.” 27

EXAMPLES OF HYPOTHESIS AS WRITTEN IN PUBLISHED ARTICLES IN RELATION TO OTHER PARTS

- EXAMPLE 1. Background, hypotheses, and aims are provided

- “Pregnant women need skilled care during pregnancy and childbirth, but that skilled care is often delayed in some countries …( text omitted ). The focused antenatal care (FANC) model of WHO recommends that nurses provide information or counseling to all pregnant women …( text omitted ). Job aids are visual support materials that provide the right kind of information using graphics and words in a simple and yet effective manner. When nurses are not highly trained or have many work details to attend to, these job aids can serve as a content reminder for the nurses and can be used for educating their patients (Jennings, Yebadokpo, Affo, & Agbogbe, 2010) ( text omitted ). Importantly, additional evidence is needed to confirm how job aids can further improve the quality of ANC counseling by health workers in maternal care …( text omitted )” 28

- “ This has led us to hypothesize that the quality of ANC counseling would be better if supported by job aids. Consequently, a better quality of ANC counseling is expected to produce higher levels of awareness concerning the danger signs of pregnancy and a more favorable impression of the caring behavior of nurses .” 28

- “This study aimed to examine the differences in the responses of pregnant women to a job aid-supported intervention during ANC visit in terms of 1) their understanding of the danger signs of pregnancy and 2) their impression of the caring behaviors of nurses to pregnant women in rural Tanzania.” 28

- EXAMPLE 2. Background, hypotheses, and aims are provided

- “We conducted a two-arm randomized controlled trial (RCT) to evaluate and compare changes in salivary cortisol and oxytocin levels of first-time pregnant women between experimental and control groups. The women in the experimental group touched and held an infant for 30 min (experimental intervention protocol), whereas those in the control group watched a DVD movie of an infant (control intervention protocol). The primary outcome was salivary cortisol level and the secondary outcome was salivary oxytocin level.” 29

- “ We hypothesize that at 30 min after touching and holding an infant, the salivary cortisol level will significantly decrease and the salivary oxytocin level will increase in the experimental group compared with the control group .” 29

- EXAMPLE 3. Background, aim, and hypothesis are provided

- “In countries where the maternal mortality ratio remains high, antenatal education to increase Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness (BPCR) is considered one of the top priorities [1]. BPCR includes birth plans during the antenatal period, such as the birthplace, birth attendant, transportation, health facility for complications, expenses, and birth materials, as well as family coordination to achieve such birth plans. In Tanzania, although increasing, only about half of all pregnant women attend an antenatal clinic more than four times [4]. Moreover, the information provided during antenatal care (ANC) is insufficient. In the resource-poor settings, antenatal group education is a potential approach because of the limited time for individual counseling at antenatal clinics.” 30

- “This study aimed to evaluate an antenatal group education program among pregnant women and their families with respect to birth-preparedness and maternal and infant outcomes in rural villages of Tanzania.” 30

- “ The study hypothesis was if Tanzanian pregnant women and their families received a family-oriented antenatal group education, they would (1) have a higher level of BPCR, (2) attend antenatal clinic four or more times, (3) give birth in a health facility, (4) have less complications of women at birth, and (5) have less complications and deaths of infants than those who did not receive the education .” 30

Research questions and hypotheses are crucial components to any type of research, whether quantitative or qualitative. These questions should be developed at the very beginning of the study. Excellent research questions lead to superior hypotheses, which, like a compass, set the direction of research, and can often determine the successful conduct of the study. Many research studies have floundered because the development of research questions and subsequent hypotheses was not given the thought and meticulous attention needed. The development of research questions and hypotheses is an iterative process based on extensive knowledge of the literature and insightful grasp of the knowledge gap. Focused, concise, and specific research questions provide a strong foundation for constructing hypotheses which serve as formal predictions about the research outcomes. Research questions and hypotheses are crucial elements of research that should not be overlooked. They should be carefully thought of and constructed when planning research. This avoids unethical studies and poor outcomes by defining well-founded objectives that determine the design, course, and outcome of the study.

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Author Contributions:

- Conceptualization: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Methodology: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Writing - original draft: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Writing - review & editing: Barroga E, Matanguihan GJ.

- Aims and Objectives – A Guide for Academic Writing

- Doing a PhD

One of the most important aspects of a thesis, dissertation or research paper is the correct formulation of the aims and objectives. This is because your aims and objectives will establish the scope, depth and direction that your research will ultimately take. An effective set of aims and objectives will give your research focus and your reader clarity, with your aims indicating what is to be achieved, and your objectives indicating how it will be achieved.

Introduction

There is no getting away from the importance of the aims and objectives in determining the success of your research project. Unfortunately, however, it is an aspect that many students struggle with, and ultimately end up doing poorly. Given their importance, if you suspect that there is even the smallest possibility that you belong to this group of students, we strongly recommend you read this page in full.

This page describes what research aims and objectives are, how they differ from each other, how to write them correctly, and the common mistakes students make and how to avoid them. An example of a good aim and objectives from a past thesis has also been deconstructed to help your understanding.

What Are Aims and Objectives?

Research aims.

A research aim describes the main goal or the overarching purpose of your research project.

In doing so, it acts as a focal point for your research and provides your readers with clarity as to what your study is all about. Because of this, research aims are almost always located within its own subsection under the introduction section of a research document, regardless of whether it’s a thesis , a dissertation, or a research paper .

A research aim is usually formulated as a broad statement of the main goal of the research and can range in length from a single sentence to a short paragraph. Although the exact format may vary according to preference, they should all describe why your research is needed (i.e. the context), what it sets out to accomplish (the actual aim) and, briefly, how it intends to accomplish it (overview of your objectives).

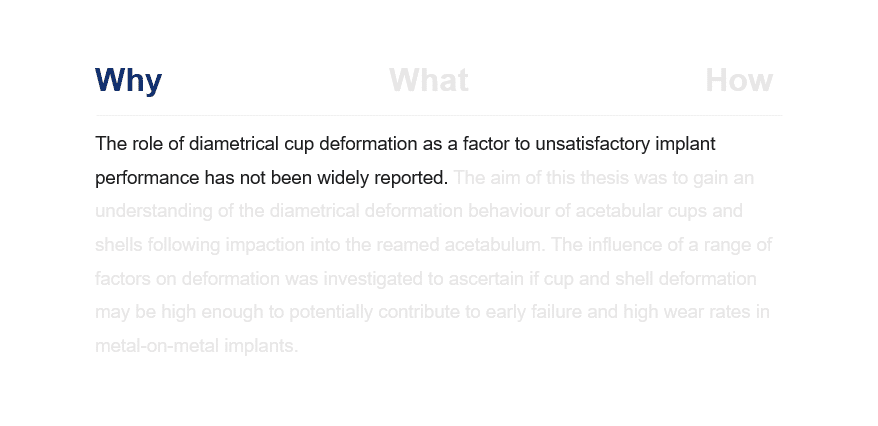

To give an example, we have extracted the following research aim from a real PhD thesis:

Example of a Research Aim

The role of diametrical cup deformation as a factor to unsatisfactory implant performance has not been widely reported. The aim of this thesis was to gain an understanding of the diametrical deformation behaviour of acetabular cups and shells following impaction into the reamed acetabulum. The influence of a range of factors on deformation was investigated to ascertain if cup and shell deformation may be high enough to potentially contribute to early failure and high wear rates in metal-on-metal implants.

Note: Extracted with permission from thesis titled “T he Impact And Deformation Of Press-Fit Metal Acetabular Components ” produced by Dr H Hothi of previously Queen Mary University of London.

Research Objectives

Where a research aim specifies what your study will answer, research objectives specify how your study will answer it.

They divide your research aim into several smaller parts, each of which represents a key section of your research project. As a result, almost all research objectives take the form of a numbered list, with each item usually receiving its own chapter in a dissertation or thesis.

Following the example of the research aim shared above, here are it’s real research objectives as an example:

Example of a Research Objective

- Develop finite element models using explicit dynamics to mimic mallet blows during cup/shell insertion, initially using simplified experimentally validated foam models to represent the acetabulum.

- Investigate the number, velocity and position of impacts needed to insert a cup.

- Determine the relationship between the size of interference between the cup and cavity and deformation for different cup types.

- Investigate the influence of non-uniform cup support and varying the orientation of the component in the cavity on deformation.

- Examine the influence of errors during reaming of the acetabulum which introduce ovality to the cavity.