- Chronicle Conversations

- Article archives

- Issue archives

- Join our mailing list

Recognizing and Overcoming Inequity in Education

About the author, sylvia schmelkes.

Sylvia Schmelkes is Provost of the Universidad Iberoamericana in Mexico City.

22 January 2020 Introduction

I nequity is perhaps the most serious problem in education worldwide. It has multiple causes, and its consequences include differences in access to schooling, retention and, more importantly, learning. Globally, these differences correlate with the level of development of various countries and regions. In individual States, access to school is tied to, among other things, students' overall well-being, their social origins and cultural backgrounds, the language their families speak, whether or not they work outside of the home and, in some countries, their sex. Although the world has made progress in both absolute and relative numbers of enrolled students, the differences between the richest and the poorest, as well as those living in rural and urban areas, have not diminished. 1

These correlations do not occur naturally. They are the result of the lack of policies that consider equity in education as a principal vehicle for achieving more just societies. The pandemic has exacerbated these differences mainly due to the fact that technology, which is the means of access to distance schooling, presents one more layer of inequality, among many others.

The dimension of educational inequity

Around the world, 258 million, or 17 per cent of the world’s children, adolescents and youth, are out of school. The proportion is much larger in developing countries: 31 per cent in sub-Saharan Africa and 21 per cent in Central Asia, vs. 3 per cent in Europe and North America. 2 Learning, which is the purpose of schooling, fares even worse. For example, it would take 15-year-old Brazilian students 75 years, at their current rate of improvement, to reach wealthier countries’ average scores in math, and more than 260 years in reading. 3 Within countries, learning results, as measured through standardized tests, are almost always much lower for those living in poverty. In Mexico, for example, 80 per cent of indigenous children at the end of primary school don’t achieve basic levels in reading and math, scoring far below the average for primary school students. 4

The causes of educational inequity

There are many explanations for educational inequity. In my view, the most important ones are the following:

- Equity and equality are not the same thing. Equality means providing the same resources to everyone. Equity signifies giving more to those most in need. Countries with greater inequity in education results are also those in which governments distribute resources according to the political pressure they experience in providing education. Such pressures come from families in which the parents attended school, that reside in urban areas, belong to cultural majorities and who have a clear appreciation of the benefits of education. Much less pressure comes from rural areas and indigenous populations, or from impoverished urban areas. In these countries, fewer resources, including infrastructure, equipment, teachers, supervision and funding, are allocated to the disadvantaged, the poor and cultural minorities.

- Teachers are key agents for learning. Their training is crucial. When insufficient priority is given to either initial or in-service teacher training, or to both, one can expect learning deficits. Teachers in poorer areas tend to have less training and to receive less in-service support.

- Most countries are very diverse. When a curriculum is overloaded and is the same for everyone, some students, generally those from rural areas, cultural minorities or living in poverty find little meaning in what is taught. When the language of instruction is different from their native tongue, students learn much less and drop out of school earlier.

- Disadvantaged students frequently encounter unfriendly or overtly offensive attitudes from both teachers and classmates. Such attitudes are derived from prejudices, stereotypes, outright racism and sexism. Students in hostile environments are affected in their disposition to learn, and many drop out early.

It doesn’t have to be like this

When left to inertial decision-making, education systems seem to be doomed to reproduce social and economic inequity. The commitment of both governments and societies to equity in education is both necessary and possible. There are several examples of more equitable educational systems in the world, and there are many subnational examples of successful policies fostering equity in education.

Why is equity in education important?

Education is a basic human right. More than that, it is an enabling right in the sense that, when respected, allows for the fulfillment of other human rights. Education has proven to affect general well-being, productivity, social capital, responsible citizenship and sustainable behaviour. Its equitable distribution allows for the creation of permeable societies and equity. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development includes Sustainable Development Goal 4, which aims to ensure “inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”. One hundred eighty-four countries are committed to achieving this goal over the next decade. 5 The process of walking this road together has begun and requires impetus to continue, especially now that we must face the devastating consequences of a long-lasting pandemic. Further progress is crucial for humanity.

Notes 1 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization , Inclusive Education. All Means All , Global Education Monitoring Report 2020 (Paris, 2020), p.8. Available at https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/report/2020/inclusion . 2 Ibid., p. 4, 7. 3 World Bank Group, World Development Report 2018: Learning to Realize Education's Promise (Washington, DC, 2018), p. 3. Available at https://www.worldbank.org/en/publication/wdr2018 . 4 Instituto Nacional para la Evaluación de la Educación, "La educación obligatoria en México", Informe 2018 (Ciudad de México, 2018), p. 72. Available online at https://www.inee.edu.mx/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/P1I243.pdf . 5 United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization , “Incheon Declaration and Framework for Action for the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 4” (2015), p. 23. Available at https://iite.unesco.org/publications/education-2030-incheon-declaration-framework-action-towards-inclusive-equitable-quality-education-lifelong-learning/ The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

Thirty Years On, Leaders Need to Recommit to the International Conference on Population and Development Agenda

With the gains from the Cairo conference now in peril, the population and development framework is more relevant than ever. At the end of April 2024, countries will convene to review the progress made on the ICPD agenda during the annual session of the Commission on Population and Development.

The LDC Future Forum: Accelerating the Attainment of the Sustainable Development Goals in the Least Developed Countries

The desired outcome of the LDC Future Forums is the dissemination of practical and evidence-based case studies, solutions and policy recommendations for achieving sustainable development.

From Local Moments to Global Movement: Reparation Mechanisms and a Development Framework

For two centuries, emancipated Black people have been calling for reparations for the crimes committed against them.

Documents and publications

- Yearbook of the United Nations

- Basic Facts About the United Nations

- Journal of the United Nations

- Meetings Coverage and Press Releases

- United Nations Official Document System (ODS)

- Africa Renewal

Libraries and Archives

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library

- UN Audiovisual Library

- UN Archives and Records Management

- Audiovisual Library of International Law

- UN iLibrary

News and media

- UN News Centre

- UN Chronicle on Twitter

- UN Chronicle on Facebook

The UN at Work

- 17 Goals to Transform Our World

- Official observances

- United Nations Academic Impact (UNAI)

- Protecting Human Rights

- Maintaining International Peace and Security

- The Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth

- United Nations Careers

- Ideas for Action

- Join the MAHB

- Why Join the MAHB?

- Current Associates

- Current Nodes

- What is the MAHB?

- Who is the MAHB?

- Acknowledgments

Why Is Education So Important in The Quest for Equality?

Gerald Nelson | April 14, 2022 | Leave a Comment

Image: Pikist

Education is vital. We can all agree on this but where we fall out of the agreement is why exactly education is so necessary for equality. Without education, there can be no progress, no development, and no improvement.

In today’s world, we are ever more aware of the issues surrounding sexism, racism, and inequality, allowing for a greater understanding of the importance of educating people to avoid these biases occurring in the first place.

What is Educational Equality and why is it necessary?

Equality isn’t always so simple. Some may assume, for example, that educational equality is as simple as providing children with the same resources. In reality, however, there’s a lot more to it than this. We will check what governments are doing to achieve this goal. What actions they are taking to advance the cause of equality? Education is crucial because it’s a toolkit for success:

- With literacy and numeracy comes confidence, with which comes self-respect. And by having self-respect, you can respect others, their accomplishments, and their cultures.

- Education is the fundamental tool for achieving social, economic, and civil rights – something which all societies strive to achieve.

Educational Inequality is usually defined as the unequal distribution of educational resources among different groups in society. The situation becomes serious when it starts influencing how people live their lives. For example, children will be less likely to go to school if they are not healthy, or educated because other things are more urgent in their life.

Categorical Educational Inequality

Categorical Education Inequality is especially apparent when comparing minority/low-income schools with majority/high-income schools. Are better-off students systematically favored in getting ahead? There are three plausible conditions:

- Higher-income parents can spend more time and money on private tutoring, school trips, and home study materials to give their children better opportunities. Therefore, better-off students have an advantage due to access to better schools, computers, technology, etc. (the so-called opportunity gap).

- Low-income schools lack the resources to educate their students. Therefore their students tend to have worse educational outcomes.

- Although the public school system is a government-funded program to allow all students an equal chance at a good education, this is not the case for most schools across third world countries – see UNESCO statistics below:

How Educational Inequality is fueling global issues

Educational inequality is a major global crisis. It has played a role in economic problems, amplified the political deadlock, exacerbated the environmental predicament, and threatens to worsen the human rights crisis. If equality in education is not addressed directly, these crises will only deepen because:

- Educational Inequality is also about race and gender . Those who are less privileged are condemned to poverty and unemployment because of a lack of quality educational resources.

- Without a sound education, people have less knowledge of the world around them or the issues facing their communities. They are less likely to vote or to pay attention to politics. This leaves them vulnerable to manipulation by those who represent narrow interests and promote fear, hatred, and violence. The result is an erosion of democratic values and an increase in authoritarianism.

- Without correction, human rights abuses will continue due to a lack of legal representation among those with no or low education levels.

- Poverty, unemployment, crimes, and health issues: A lack of education and skills forces children into poverty because they can’t get jobs or start a business. It also leaves them without hope and is one of the reasons for unemployment, lower life expectancy, malnutrition, a higher chance of chronic diseases, and crime rates.

- Limited opportunities: The most significant issue is that lack of education reduces the opportunities for people to have a decent life. Limited options increase the division of social classes, lower social mobility, and reduce the ability to build networks and social contacts. Students in poor countries also spend a lot of time working to support their families rather than focusing on their school work. These factors also worsen the upbringing of coming generations.

- Extremism: Inequality can also lead to increased violence, racism, gender bias, and extremism, which causes further economic and democratic challenges.

- Inability to survive pandemics: Unlike developed nations after COVID, underdeveloped countries are stuck in their unstable economic cycles. Inequality causes a lack of awareness and online educational resources, lower acceptance of preventive measures, and unaffordable vaccines, for example. According to the United Nations , “Before the coronavirus crisis, projections showed that more than 200 million children would be out of school , and only 60 percent of young people would be completing upper secondary education in 2030”.

- Unawareness of technological advancements: The world is becoming more tech-savvy, while students in underdeveloped countries remain unaware of the latest technological achievements as well as unable to implement them. This also widens the education gap between countries.

- Gender inequality in education: In general, developing countries compromise over funds allocation for women’s education to manage their depletion of national income. As such, they consider women less efficient and productive than men. Meanwhile, many parents do not prefer sending their daughters to school because they do not think that women can contribute equally to men in the country’s development. However, if we have to overcome this, there should be an increase in funding and scholarships for women’s education.

- Environmental crises: People are usually less aware of the harmful emissions produced in their surroundings and are therefore less prepared to deal with increased pollution levels. This also affects climate change. The less educated the children, the more likely they are to contribute to climate change as adults. This is because education is not just about learning facts and skills but also about recognizing problems and applying knowledge in innovative ways.

- A child who has dropped out of school will generally contribute less to society than a child who has completed secondary school. A child who has completed secondary school will contribute less than a child who went to university. This difference increases over time because those with higher levels of education tend to be more open-minded, flexible thinkers and are therefore better able to adapt to changing environmental conditions.

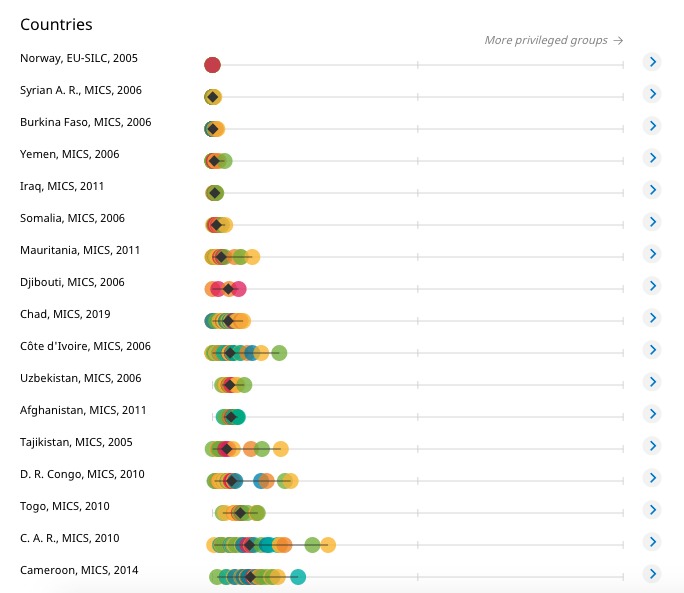

Equality in education is therefore essential for addressing international issues including economic inequality, climate change, social deprivation, and access to healthcare. Many children in poor regions are deprived of education (see chart below) which is the only way out of poverty .

Proposed Solutions

The United Nations Development Program says that access to education is a human right, and should be individually accessible and available to all by 2030. It demands:

- International collaborations to ensure that every child has the same quality education and to develop joint curricula and academic programs. The quality of teaching methodologies should not be compromised and includes providing financial assistance and tools for equal access.

- Running campaigns to discourage race, gender, and ethnicity differences, arranging more seminars to reach low-income groups, and providing adequate financial assistance, training, and part-time jobs for sole earners.

- Modifying scholarship criteria to better support deserving students who cannot afford university due to language tests and low grades.

- Increasing the minimum wage so that sole breadwinners can afford quality education for their children.

- Schools should bear transportation costs and offer free grants to deserving kids from low-income families.

- Giving more attention to slum-side schools by updating and implementing new techniques and resources.

- Allowing students to learn in their own language with no enforcement of international languages and offering part-time courses in academies and community colleges in other languages.

Resolving educational inequality has many benefits for the wider society. Allowing children from disadvantaged backgrounds to get an education will help them find better jobs with higher salaries, improving their quality of life, and making them more productive members of society. It decreases the likelihood of conflict and increases access to health care, stable economic growth, and unlimited opportunities.

Conclusion:

It’s been said that great minds start out as small ones. To level the playing field, we need to focus on best educating our next generation of innovators and leaders, both from an individual and a societal standpoint. If we want equality to become a reality, it will be up to us to ensure that equality is at the forefront of our education system.

References:

Environmental Conscience: 42 Causes, Effects & Solutions for a Lack of Education – E&C (environmental-conscience.com)

School of Education Online Programs: What the U.S. Education System Needs to Reduce Inequality | American University

Educational Inequality: Solutions | Educational Inequality (wordpress.com)

Giving Compass: Seven Solutions for Education Inequality · Giving Compass

Science.org: Polarization under rising inequality and economic decline

Research Gate: Inequality and Economic Growth

University of Munich: pdf (uni-muenchen.de)

Research Gate: Effects-of-inequality-and-poverty-vs-teachers-and-schooling-on-Americas-youth.pdf (researchgate.net)

Borgen Magzine

United Nations: Education as the Pathway towards Gender Equality

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals – Education

This article has been edited in line with our guidelines

Gerald Nelson is a freelance academic essay writer at perfectessaywriting.com who also works with several e ducational and human rights organizations.

The MAHB Blog is a venture of the Millennium Alliance for Humanity and the Biosphere. Questions should be directed to [email protected]

Education and inequality in 2021: how to change the system

Research Associate at the University of Geneva's department of Education and Psychology; Campus and Secondary Principal at the International School of Geneva's La Grande Boissière, Université de Genève

Disclosure statement

Conrad Hughes does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

AUF (Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie) provides funding as a member of The Conversation FR.

View all partners

Since its earliest traces, at least 5,000 years ago , formal education – meaning an education centred on literacy and numeracy – has always been highly selective. Ancient Egyptian priest schools and schools for scribes in Sumeria were only open to the children of the clergy or future monarchs.

Later on, the wealthy would use private tutors, such as the Sophists of Athens (500 - 400 BCE). Ancient Greek schools, such as Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum , were restricted to a small elite group. Formal education was reserved for male children who were wealthy, able, and privileged.

Through time, even after learning societies began to flourish, it was still an education for some and not for everybody.

In the 1800s Black people were denied access to quality education in the United States. In European colonies, education was used to strip people of their cultural heritage and relegate them to a future of menial labour.

Education has always been less accessible to women than men. Even today, over 130 million girls are still out of school. Although the difference between girls and boys is lessening, the disparity disadvantaging girls persists . From a socioeconomic perspective, in many countries, private schools continue to grow alongside compulsory state schools, offering a different style of education, sometimes at a very high price.

Today, progress to attain the dream of universal access to education is slow. UNESCO’s Education for All and the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal 4 , which aims to “ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”, are still far from materialising: roughly 260 million children are still not in school . The COVID-19 pandemic has made the situation worse: remote learning is inaccessible to roughly 500 million students . Estimates are that over 200 million children will still be out of school by 2030 .

In my study “Education and Elitism” , the overarching question that runs through the book is about the future of education worldwide: What are the prospects for the future? Are we facing an even more enclaved, pauperised majority while a tiny minority become more powerful and wealthy?

Certain paths could open up. On the one hand, places in selective institutions could become even more difficult to access while private education strips ahead of national standards. On the other hand, changes might make education more inclusive: this would include scholarships, cheaper private education, more robust state systems and deep assessment reform.

Prospects for the future

Scholarship programmes: These allow the brightest and poorest access to transformative learning ecosystems . However, this contributes to a brain drain and does not develop the local educational sector , particularly in Africa.

Cheaper private education: A movement of accessible private schools is growing . This allows more children to access some of the value-added features of such systems – more curriculum flexibility, smaller class sizes, more individual student tracking. However, there are reports that this is widening social divides , as the public system isn’t improving fast enough to keep up.

More robust state systems: UNESCO estimates that it would cost a total of US$340 billion each year to achieve universal pre-primary, primary, and secondary education in low- and lower-middle-income countries by 2030. The average annual per-student spending for quality primary education in a low-income country is predicted to be US$197 in 2030. This creates an estimated annual gap of US$39 billion between 2015 and 2030. Financing this gap calls for action from private sector donors, philanthropists, and international financial institutions.

Online learning: The COVID-19 lockdown has brought inequalities to the surface. However, the rise of online learning worldwide has been phenomenal. This opens up the potential to widen access to learning socioeconomically and, if delivered by skilled facilitators, academically . There is a problem, though: online instruction lacks the emotional quantum that face-to-face learning creates. Because of this, motivation levels and persistence tend to be low in online learning environments . And importantly, in many countries, many students still don’t have access to the internet.

A way forward: reforming the system

Perhaps the most substantive movement to reduce inequalities would not be to accelerate access to a broken system but to reform the system itself .

It is time to look further than narrow academic metrics as the only way of describing young people’s competences. The whole educational system across high schools, in every country, needs to change dramatically. Assessment models should recognise and nurture more varied and multiple competences, in particular, attitudes, skills and types of knowledge beyond those concentrated in constructs that are favoured by socioeconomic background, such as literacy and numeracy .

Read more: Education needs a refocus so that all learners reach their full potential

Until universities and employers look beyond traditional metrics, it will be difficult to break a circuit that favours, for the large part, middle class, socially and ethnically privileged candidates.

To truly break away from a millennia of elitist, selective systems , the approach needs to move from pure academics to a credit system that captures many more stories of learning. This new credit system should be known as a passport, meaning students have stamped it with the various competences such as lifelong learning and self-agency that they have developed throughout their learning (in an out of school), allowing them to be recognised on numerous different fronts.

A coalition of schools from every continent is working on this project, now seeking universities to sit around the table in order to bring this work to its conclusion. This would mean co-designing an elegant, life worthy transcript to allow more access to more children based on more expansive criteria.

- Peacebuilding

- Education inequality

- Women and girls

- Out of school children

Lecturer / Senior Lecturer - Marketing

Communications and Engagement Officer, Corporate Finance Property and Sustainability

Assistant Editor - 1 year cadetship

Executive Dean, Faculty of Health

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer, Earth System Science (School of Science)

The Hechinger Report

Covering Innovation & Inequality in Education

A decade of research on the rich-poor divide in education

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

The Hechinger Report is a national nonprofit newsroom that reports on one topic: education. Sign up for our weekly newsletters to get stories like this delivered directly to your inbox. Consider supporting our stories and becoming a member today.

Get important education news and analysis delivered straight to your inbox

- Weekly Update

- Future of Learning

- Higher Education

- Early Childhood

- Proof Points

Americans like to believe that education can be a great equalizer, allowing even the poorest child who studies hard to enter the middle class. But when I looked at what academic researchers and federal data reports have said about the great educational divide between the rich and poor in our country, that belief turns out to be a myth. Basic education, from kindergarten through high school, only expands the disparities.

In 2015, during the Obama administration, the federal education department issued a report that showed how the funding gap between rich and poor schools grew 44 percent over a decade between 2001-2 and 2011-12. That meant that the richest 25 percent of school districts spent $1,500 more per student, on average, than the poorest 25 percent of school districts.

I wish I could have continued to track this data between rich and poor schools to see if school spending had grown more fair. But the Trump administration crunched the numbers differently. When it issued a report in 2018 , covering the 2014-15 school year, it found that the wealthiest 25 percent of districts spent $450 more per student than the poorest 25 percent.

That didn’t mean there was a giant 70 percent improvement from $1,500. The Trump administration added together all sources of funds, including federal funding, which amounts to 8 percent of total school spending, while the Obama administration excluded federal funds, counting only state and local dollars, which make up more than 90 percent of education funds. The Obama administration argued at the time that federal funds for poor students were intended to supplement local funds because it takes more resources to overcome childhood poverty, not to create a level playing field.

Rather than marking an improvement, there were signs in the Trump administration data that the funding gap between rich and poor had worsened during the Great Recession if you had compared the figures apples to apples, either including or excluding federal funds. In a follow-up report issued in 2019, the Trump administration documented that the funding gap between rich and poor schools had increased slightly to $473 per student between the 2014-15 and 2015-16 school years.

It’s not just a divide between rich and poor but also between the ultra rich and everyone else. In 2020, a Pennsylvania State University researcher documented how the wealthiest school districts in America — the top 1 percent — fund their schools at much higher levels than everyone else and are increasing their school spending at a faster rate. The school funding gap between a top 1 percent district (mostly white suburbs) and an average-spending school district at the 50th percentile widened by 32 percent between 2000 and 2015, the study calculated. Nassau County, just outside New York City on Long Island, has the highest concentration of students who attend the best funded public schools among all counties in the country. Almost 17 percent of all the top 1 percent students in the nation live in this one county.

Funding inequities are happening in a context of increased poverty in our schools. In 2013, I documented how the number of high poverty schools had increased by about 60 percent to one out of every five schools in 2011 from one out of every eight schools in 2000. To win this unwelcome designation, 75 percent or more of an elementary, middle or high school’s students lived in families poor enough to qualify for free or reduced-price lunch. It’s since gotten worse. In the most recent federal report , covering the 2016-17 school year, one out of every four schools in America was classified as high poverty.

It’s not just that poverty is becoming more concentrated in certain schools; more students in the school system are poor. In 2014, I documented a 40 percent jump in the number of school-aged children living in poverty between 2000 and 2012 from one out of every seven children to one out of every five students. In the most recent report, for the 2016-17 school year, the poverty rate declined from 21 percent in 2010 to 18 percent in 2017. About 13 million children under the age of 18 were in families living in poverty.

When you break the data down by race, there are other striking patterns. One third of all Black children under 18 were living in poverty in 2016-17, compared with a quarter of Hispanic children. White and Asian children have a similar poverty rate of 11 percent and 10 percent, respectively.

Sociologists like Sean Reardon at Stanford University and Ann Owens at the University of Southern California have built a body of evidence that school segregation by income is what’s really getting worse in America, not school segregation by race. But it’s a complicated argument because Black and Latino students are more likely to be poor and less likely to be rich. So the two things — race and poverty — are intertwined.

In 2019, Reardon studied achievement gaps in every school in America and found that the difference in poverty rates between predominantly Black and predominantly white schools explains the achievement gaps we see and why white schools tend to show higher test scores than Black schools. When white and Black schools have the same poverty rates, Reardon didn’t see a difference in academic achievement. The problem is that Black students are more often poor and attending schools with more poor students. And other than a handful of high-performing charter schools in a few cities, he couldn’t find examples of academic excellence among schools with a high-poverty student body.

“It doesn’t seem that we have any knowledge about how to create high-quality schools at scale under conditions of concentrated poverty,” said Reardon. “And if we can’t do that, then we have to do something about segregation. Otherwise we’re consigning Black and Hispanic and low-income students to schools that we don’t know how to make as good as other schools. The implication is that you have got to address segregation.”

Previous Proof Points columns cited in this column:

The number of high-poverty schools increases by about 60 percent

Poverty among school-age children increases by 40 percent since 2000

The gap between rich and poor schools grew 44 percent over a decade

Data show segregation by income (not race) is what’s getting worse in schools

In 6 states, school districts with the neediest students get less money than the wealthiest

An analysis of achievement gaps in every school in America shows that poverty is the biggest hurdle

Rich schools get richer: School spending analysis finds widening gap between top 1% and the rest of us

This story about education inequality in America written by Jill Barshay and produced by The Hechinger Report , a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for the Hechinger newsletter .

Related articles

The Hechinger Report provides in-depth, fact-based, unbiased reporting on education that is free to all readers. But that doesn't mean it's free to produce. Our work keeps educators and the public informed about pressing issues at schools and on campuses throughout the country. We tell the whole story, even when the details are inconvenient. Help us keep doing that.

Join us today.

Jill Barshay SENIOR REPORTER

(212)... More by Jill Barshay

Letters to the Editor

At The Hechinger Report, we publish thoughtful letters from readers that contribute to the ongoing discussion about the education topics we cover. Please read our guidelines for more information. We will not consider letters that do not contain a full name and valid email address. You may submit news tips or ideas here without a full name, but not letters.

By submitting your name, you grant us permission to publish it with your letter. We will never publish your email address. You must fill out all fields to submit a letter.

Thanks to Jill Barshay for the excellent column reminding us that there is much more to the rich/poor divide in our public schools than just the availability of digital devices and wi-fi. The real problem with equity in education is the lack of equity in school funding, which is an issue both of inequity in society and the ways in which public schools are funded (i.e., primarily local tax revenues).

Other barriers that kept the “school door blocked” for many low income students during this season of remote learning — and, presumably, next school year, as well — include: 1. Some with access to devices and wi-fi have had service disconnected at times due to unpaid (unpayable) bills. 2. Many have no private space in their homes from where to participate in synchronous learning/Zoom calls 3. With loss of family income and no child care, some have work or baby-sitting responsibilities that interfere with participation 4. Deadening effects of online learning cause many low-income students to disconnect and/or “drop out”. 5. In ability to access teacher supports and specialized instruction, esp. for English language learners and children with special needs. 6. Parent inability to assist students with computer routines, glitches, log-ins, etc

As districts address equity in the coming school year, we must also address the modes of learning that we consider both effective and valuable. If the top priority is engaging all students we need high engagement models based in trauma-informed practices, social and racial justice curricula, service learning, interdisciplinary project- and place-based learning, outdoor learning and other innovative ways to make education relevant to all students, regardless of their zip codes. Relax the standards. Cancel high stakes testing. Trust teachers to use their creativity to connect with every student and family. Otherwise, “remote” or “hybrid” learning, regardless of the availability of technology, will only be widening the gaps that structural racism has already created.

Why are we NOT reaching out to the teaching programs started by Marva Collins in Chicago and Ron Clark in Atlanta? Why are we NOT looking at a book called Schools That Work and viewing the achievements and strategies followed by successful programs. Let’s follow successful schools, successful environments in urban, rural, and suburban locations. As an eductor who started teaching in the Ocean-Hill Brownsville area of Brooklyn, N,Y. in 1971, there was a wildcat strike happening and this area was the where decentralization took place in N.Y.C. Rev. Al Sharpton’s church was down the block from I.S. 271. It took 2 years before a no nonsense, BLACK principal, took control over the choas and the movement of 125 teachers going and then coming to this “high poverty” intermediate school. There was stability of staff and the message was, you’re here to learn. I taught there for 7 incredible years and grew to understand what it was like being a minority teacher and human being. I then moved to Columbia, MD. where I lived in a planned community where diversity of color, homes, religions and belief in humanity living together as ONE took place. I taught in a white disadvantaged area for 2 years and observed the same behaviors students exhibited except there was no leadership at the top of this school. Now I teach in a suburban area for the last 31 years with limited diversity and succeeds because of innovative leadership, extraordinary teachers, and pretty high achieving students. Yes, I know every students must have access to technology as a MUST. Yes, I know urban education, rural education, and suburban education do education diffferently. Yes, I know poverty sucks, and I know distant learning may be around for a while. Change must come from the top. Let’s follow the successful educators, the successful programs, the dynamic elected officials who can shake up things so our students, our kids, our educational systems can be the change that can bring poverty to it’s knees.

I live on Long Island and know that whatever is written here about us is true. The Freeport Public School waste millions of taxpayers dollars throwing out teaching equipment, devices books that could be just given to the less fortunate schools next door-Queens, Brooklyn and the Bronx; where we see children suffering because of lack of proper learning tools. I am from the Caribbean where l taught for years. Oh l wish we were as privileged as these children. Maybe one day the disparity will end. Hopefully.

I enjoy reading this post. I am currently doing my thesis and the research question is: Do California K-12 public schools in lower-income communities offer the same level of academic curriculum as those in middle-income and wealthy communities? Do you have the reference page for those studies or even any peer reviewers where you got the information? I would like to review those studies and use them for my thesis. Thank you

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Sign me up for the newsletter!

Submit a letter

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

It’s on Facebook, and it’s complicated

How far has COVID set back students?

What do anti-Jewish hate, anti-Muslim hate have in common?

The costs of inequality: education’s the one key that rules them all.

When there’s inequity in learning, it’s usually baked into life, Harvard analysts say

Corydon Ireland

Harvard Correspondent

Third in a series on what Harvard scholars are doing to identify and understand inequality, in seeking solutions to one of America’s most vexing problems.

Before Deval Patrick ’78, J.D. ’82, was the popular and successful two-term governor of Massachusetts, before he was managing director of high-flying Bain Capital, and long before he was Harvard’s most recent Commencement speaker , he was a poor black schoolchild in the battered housing projects of Chicago’s South Side.

The odds of his escaping a poverty-ridden lifestyle, despite innate intelligence and drive, were long. So how did he help mold his own narrative and triumph over baked-in societal inequality ? Through education.

“Education has been the path to better opportunity for generations of American strivers, no less for me,” Patrick said in an email when asked how getting a solid education, in his case at Milton Academy and at Harvard, changed his life.

“What great teachers gave me was not just the skills to take advantage of new opportunities, but the ability to imagine what those opportunities could be. For a kid from the South Side of Chicago, that’s huge.”

If inequality starts anywhere, many scholars agree, it’s with faulty education. Conversely, a strong education can act as the bejeweled key that opens gates through every other aspect of inequality , whether political, economic , racial, judicial, gender- or health-based.

Simply put, a top-flight education usually changes lives for the better. And yet, in the world’s most prosperous major nation, it remains an elusive goal for millions of children and teenagers.

Plateau on educational gains

The revolutionary concept of free, nonsectarian public schools spread across America in the 19th century. By 1970, America had the world’s leading educational system, and until 1990 the gap between minority and white students, while clear, was narrowing.

But educational gains in this country have plateaued since then, and the gap between white and minority students has proven stubbornly difficult to close, says Ronald Ferguson, adjunct lecturer in public policy at Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) and faculty director of Harvard’s Achievement Gap Initiative. That gap extends along class lines as well.

“What great teachers gave me was not just the skills to take advantage of new opportunities, but the ability to imagine what those opportunities could be. For a kid from the South Side of Chicago, that’s huge.” — Deval Patrick

In recent years, scholars such as Ferguson, who is an economist, have puzzled over the ongoing achievement gap and what to do about it, even as other nations’ school systems at first matched and then surpassed their U.S. peers. Among the 34 market-based, democracy-leaning countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the United States ranks around 20th annually, earning average or below-average grades in reading, science, and mathematics.

By eighth grade, Harvard economist Roland G. Fryer Jr. noted last year, only 44 percent of American students are proficient in reading and math. The proficiency of African-American students, many of them in underperforming schools, is even lower.

“The position of U.S. black students is truly alarming,” wrote Fryer, the Henry Lee Professor of Economics, who used the OECD rankings as a metaphor for minority standing educationally. “If they were to be considered a country, they would rank just below Mexico in last place.”

Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE) Dean James E. Ryan, a former public interest lawyer, says geography has immense power in determining educational opportunity in America. As a scholar, he has studied how policies and the law affect learning, and how conditions are often vastly unequal.

His book “Five Miles Away, A World Apart” (2010) is a case study of the disparity of opportunity in two Richmond, Va., schools, one grimly urban and the other richly suburban. Geography, he says, mirrors achievement levels.

A ZIP code as predictor of success

“Right now, there exists an almost ironclad link between a child’s ZIP code and her chances of success,” said Ryan. “Our education system, traditionally thought of as the chief mechanism to address the opportunity gap, instead too often reflects and entrenches existing societal inequities.”

Urban schools demonstrate the problem. In New York City, for example, only 8 percent of black males graduating from high school in 2014 were prepared for college-level work, according to the CUNY Institute for Education Policy, with Latinos close behind at 11 percent. The preparedness rates for Asians and whites — 48 and 40 percent, respectively — were unimpressive too, but nonetheless were firmly on the other side of the achievement gap.

In some impoverished urban pockets, the racial gap is even larger. In Washington, D.C., 8 percent of black eighth-graders are proficient in math, while 80 percent of their white counterparts are.

Fryer said that in kindergarten black children are already 8 months behind their white peers in learning. By third grade, the gap is bigger, and by eighth grade is larger still.

According to a recent report by the Education Commission of the States, black and Hispanic students in kindergarten through 12th grade perform on a par with the white students who languish in the lowest quartile of achievement.

There was once great faith and hope in America’s school systems. The rise of quality public education a century ago “was probably the best public policy decision Americans have ever made because it simultaneously raised the whole growth rate of the country for most of the 20th century, and it leveled the playing field,” said Robert Putnam, the Peter and Isabel Malkin Professor of Public Policy at HKS, who has written several best-selling books touching on inequality, including “Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of the American Community” and “Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis.”

Historically, upward mobility in America was characterized by each generation becoming better educated than the previous one, said Harvard economist Lawrence Katz. But that trend, a central tenet of the nation’s success mythology, has slackened, particularly for minorities.

“Thirty years ago, the typical American had two more years of schooling than their parents. Today, we have the most educated group of Americans, but they only have about .4 more years of schooling, so that’s one part of mobility not keeping up in the way we’ve invested in education in the past,” Katz said.

As globalization has transformed and sometimes undercut the American economy, “education is not keeping up,” he said. “There’s continuing growth of demand for more abstract, higher-end skills” that schools aren’t delivering, “and then that feeds into a weakening of institutions like unions and minimum-wage protections.”

“The position of U.S. black students is truly alarming.” — Roland G. Fryer Jr.

Fryer is among a diffuse cohort of Harvard faculty and researchers using academic tools to understand the achievement gap and the many reasons behind problematic schools. His venue is the Education Innovation Laboratory , where he is faculty director.

“We use big data and causal methods,” he said of his approach to the issue.

Fryer, who is African-American, grew up poor in a segregated Florida neighborhood. He argues that outright discrimination has lost its power as a primary driver behind inequality, and uses economics as “a rational forum” for discussing social issues.

Better schools to close the gap

Fryer set out in 2004 to use an economist’s data and statistical tools to answer why black students often do poorly in school compared with whites. His years of research have convinced him that good schools would close the education gap faster and better than addressing any other social factor, including curtailing poverty and violence, and he believes that the quality of kindergarten through grade 12 matters above all.

Supporting his belief is research that says the number of schools achieving excellent student outcomes is a large enough sample to prove that much better performance is possible. Despite the poor performance by many U.S. states, some have shown that strong results are possible on a broad scale. For instance, if Massachusetts were a nation, it would rate among the best-performing countries.

At HGSE, where Ferguson is faculty co-chair as well as director of the Achievement Gap Initiative, many factors are probed. In the past 10 years, Ferguson, who is African-American, has studied every identifiable element contributing to unequal educational outcomes. But lately he is looking hardest at improving children’s earliest years, from infancy to age 3.

In addition to an organization he founded called the Tripod Project , which measures student feedback on learning, he launched the Boston Basics project in August, with support from the Black Philanthropy Fund, Boston’s mayor, and others. The first phase of the outreach campaign, a booklet, videos, and spot ads, starts with advice to parents of children age 3 or younger.

“Maximize love, manage stress” is its mantra and its foundational imperative, followed by concepts such as “talk, sing, and point.” (“Talking,” said Ferguson, “is teaching.”) In early childhood, “The difference in life experiences begins at home.”

At age 1, children score similarly

Fryer and Ferguson agree that the achievement gap starts early. At age 1, white, Asian, black, and Hispanic children score virtually the same in what Ferguson called “skill patterns” that measure cognitive ability among toddlers, including examining objects, exploring purposefully, and “expressive jabbering.” But by age 2, gaps are apparent, with black and Hispanic children scoring lower in expressive vocabulary, listening comprehension, and other indicators of acuity. That suggests educational achievement involves more than just schooling, which typically starts at age 5.

Key factors in the gap, researchers say, include poverty rates (which are three times higher for blacks than for whites), diminished teacher and school quality, unsettled neighborhoods, ineffective parenting, personal trauma, and peer group influence, which only strengthens as children grow older.

“Peer beliefs and values,” said Ferguson, get “trapped in culture” and are compounded by the outsized influence of peers and the “pluralistic ignorance” they spawn. Fryer’s research, for instance, says that the reported stigma of “acting white” among many black students is true. The better they do in school, the fewer friends they have — while for whites who are perceived as smarter, there’s an opposite social effect.

The researchers say that family upbringing matters, in all its crisscrossing influences and complexities, and that often undercuts minority children, who can come from poor or troubled homes. “Unequal outcomes,” he said, “are from, to a large degree, inequality in life experiences.”

Trauma also subverts achievement, whether through family turbulence, street violence, bullying, sexual abuse, or intermittent homelessness. Such factors can lead to behaviors in school that reflect a pervasive form of childhood post-traumatic stress disorder.

[gz_sidebar align=”left”]

Possible solutions to educational inequality:

- Access to early learning

- Improved K-12 schools

- More family mealtimes

- Reinforced learning at home

- Data-driven instruction

- Longer school days, years

- Respect for school rules

- Small-group tutoring

- High expectations of students

- Safer neighborhoods

[/gz_sidebar]

At Harvard Law School, both the Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative and the Education Law Clinic marshal legal aid resources for parents and children struggling with trauma-induced school expulsions and discipline issues.

At Harvard Business School, Karim R. Lakhani, an associate professor who is a crowdfunding expert and a champion of open-source software, has studied how unequal racial and economic access to technology has worked to widen the achievement gap.

At Harvard’s Project Zero, a nonprofit called the Family Dinner Project is scraping away at the achievement gap from the ground level by pushing for families to gather around the meal table, which traditionally was a lively and comforting artifact of nuclear families, stable wages, close-knit extended families, and culturally shared values.

Lynn Barendsen, the project’s executive director, believes that shared mealtimes improve reading skills, spur better grades and larger vocabularies, and fuel complex conversations. Interactive mealtimes provide a learning experience of their own, she said, along with structure, emotional support, a sense of safety, and family bonding. Even a modest jump in shared mealtimes could boost a child’s academic performance, she said.

“We’re not saying families have to be perfect,” she said, acknowledging dinnertime impediments like full schedules, rudimentary cooking skills, the lure of technology, and the demands of single parenting. “The perfect is the enemy of the good.”

Whether poring over Fryer’s big data or Barendsen’s family dinner project, there is one commonality for Harvard researchers dealing with inequality in education: the issue’s vast complexity. The achievement gap is a creature of interlocking factors that are hard to unpack constructively.

Going wide, starting early

With help from faculty co-chair and Jesse Climenko Professor of Law Charles J. Ogletree, the Achievement Gap Initiative is analyzing the factors that make educational inequality such a complex puzzle: home and family life, school environments, teacher quality, neighborhood conditions, peer interaction, and the fate of “all those wholesome things,” said Ferguson. The latter include working hard in school, showing respect, having nice friends, and following the rules, traits that can be “elements of a 21st-century movement for equality.”

In the end, best practices to create strong schools will matter most, said Fryer.

He called high-quality education “the new civil rights battleground” in a landmark 2010 working paper for the Handbook of Labor Economics called “Racial Inequality in the 21st Century: The Declining Significance of Discrimination.”

Fryer tapped 10 large data sets on children 8 months to 17 years old. He studied charter schools, scouring for standards that worked. He champions longer school days and school years, data-driven instruction, small-group tutoring, high expectations, and a school culture that prizes human capital — all just “a few simple investments,” he wrote in the working paper. “The challenge for the future is to take these examples to scale” across the country.

How long would closing the gap take with a national commitment to do so? A best-practices experiment that Fryer conducted at low-achieving high schools in Houston closed the gap in math skills within three years, and narrowed the reading achievement gap by a third.

“You don’t need Superman for this,” he said, referring to a film about Geoffrey Canada and his Harlem Children’s Zone, just high-quality schools for everyone, to restore 19th-century educator Horace Mann’s vision of public education as society’s “balance-wheel.”

Last spring, Fryer, still only 38, won the John Bates Clark medal, the most prestigious award in economics after the Nobel Prize. He was a MacArthur Fellow in 2011, became a tenured Harvard professor in 2007, was named to the prestigious Society of Fellows at age 25. He had a classically haphazard childhood, but used school to learn, grow, and prosper. Gradually, he developed a passion for social science that could help him answer what was going wrong in black lives because of educational inequality.

With his background and talent, Fryer has a dramatically unique perspective on inequality and achievement, and he has something else: a seemingly counterintuitive sense that these conditions will improve, once bad schools learn to get better. Discussing the likelihood of closing the achievement gap if Americans have the political and organizational will to do so, Fryer said, “I see nothing but optimism.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story inaccurately portrayed details of Dr. Fryer’s background.

Illustration by Kathleen M.G. Howlett. Harvard staff writer Christina Pazzanese contributed to this report.

Next Tuesday: Inequality in health care

Share this article

You might like.

‘Spermworld’ documentary examines motivations of prospective parents, volunteer donors who connect through private group page

An economist, a policy expert, and a teacher explain why learning losses are worse than many parents realize

Researchers scrutinize various facets of these types of bias, and note sometimes they both reside within the same person.

Epic science inside a cubic millimeter of brain

Researchers publish largest-ever dataset of neural connections

Excited about new diet drug? This procedure seems better choice.

Study finds minimally invasive treatment more cost-effective over time, brings greater weight loss

- Graduate School of Education

- GSE Theses and Dissertations

- Communities & Collections

- By Issue Date

- FAS Department

- Quick submit

- Waiver Generator

- DASH Stories

- Accessibility

- COVID-related Research

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- By Collections

- By Departments

Show simple item record

Essays on Educational Inequality

Files in this item.

This item appears in the following Collection(s)

- GSE Theses and Dissertations [329]

Educational Inequality*

This chapter provides new evidence on educational inequality and reviews the literature on the causes and consequences of unequal education. We document large achievement gaps between children from different socio-economic backgrounds, show how patterns of educational inequality vary across countries, time, and generations, and establish a link between educational inequality and social mobility. We interpret this evidence from the perspective of economic models of skill acquisition and investment in human capital. The models account for different channels underlying unequal education and highlight how endogenous responses in parents' and children's educational investments generate a close link between economic inequality and educational inequality. Given concerns over the extended school closures during the Covid-19 pandemic, we also summarize early evidence on the impact of the pandemic on children's education and on possible long-run repercussions for educational inequality.

This chapter has been prepared for the Handbook of the Economics of Education Volume 6. The asterisk has been added to the title of this paper to distinguish it from NBER working paper 8206 which has the same title. We thank Kwok Yan Chiu, Ricard Grebol, and Ashton Welch for excellent research assistance and the editors, John Jerrim, Sandra McNally, Anders Björklund, Jonas Radl, Martin Hällsten, and Christopher Rauh for helpful comments. Financial support from the National Science Foundation (grant SES-1949228), the Comunidad de Madrid and the MICIU (CAM-EPUC3M11, H2019/HUM-589, ECO2017-87908-R) is gratefully acknowledged. This paper uses data from the National Educational Panel Study (NEPS): Starting Cohort 4–9th Grade, doi:10.5157/NEPS:SC4:1.0.0, Next Steps: Sweeps 1-8, 2004-2016. 16th Edition. UK Data Service SN: 5545 http://doi.org/10.5255/UKDA-SN-5545-8, Longitinal Studies of Australian Youth (LSAY): 15 Year-Olds in 2003, doi:10.4225/87/5IOBPG, Education Longitudinal Study (ELS), 2002: Base Year. https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR04275.v1. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research.

MARC RIS BibTeΧ

Download Citation Data

More from NBER

In addition to working papers , the NBER disseminates affiliates’ latest findings through a range of free periodicals — the NBER Reporter , the NBER Digest , the Bulletin on Retirement and Disability , the Bulletin on Health , and the Bulletin on Entrepreneurship — as well as online conference reports , video lectures , and interviews .

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

Is Education No Longer the ‘Great Equalizer’?

By Thomas B. Edsall

Mr. Edsall contributes a weekly column from Washington, D.C., on politics, demographics and inequality.

There is an ongoing debate over what kinds of investment in human capital — roughly the knowledge, skills, habits, abilities, experience, intelligence, training, judgment, creativity and wisdom possessed by an individual — contribute most to productivity and life satisfaction.

Is education no longer “a great equalizer of the conditions of men,” as Horace Mann declared in 1848, but instead a great divider? Can the Biden administration’s efforts to distribute cash benefits to the working class and the poor produce sustained improvements in the lives of those on the bottom tiers of income and wealth — or would a substantial investment in children’s training and enrichment programs at a very early age produce more consistent and permanent results?

Take the case of education. On this score — if the assumption is “the more education, the better” — then the United States looks pretty good.

From 1976 to 2016 the white high school completion rate rose from 86.4 percent to 94.5 percent, the Black completion rate from 73.5 percent to 92.2 percent, and the Hispanic completion rate rose from 60.3 percent to 89.1 percent. The graduation rate of whites entering four-year colleges from 1996 to 2012 rose from 33.7 to 43.7 percent, for African Americans it rose from 19.5 to 23.8 percent and for Hispanics it rose from 22.8 to 34.1 percent.

But these very gains appear to have also contributed to the widening disparity in income between those with different levels of academic attainment, in part because of the very different rates of income growth for men and women with high school degrees, college degrees and graduate or professional degrees.

Education lifts all boats, but not by equal amounts.

David Autor , an economist at M.I.T., together with the Harvard economists Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz , tackled this issue in a paper last year, “ Extending the Race Between Education and Technology ,” asking: “How much of the overall rise in wage inequality since 1980 can be attributed to the large increase in educational wage differentials?”

Their answer:

Returns to a year of K-12 schooling show little change since 1980. But returns to a year of college rose by 6.5 log points, from 0.076 in 1980 to 0.126 in 2000 to 0.141 in 2017. The returns to a year of post-college (graduate and professional) rose by a whopping 10.9 log points, from 0.067 in 1980 to 0.131 in 2000 and to 0.176 in 2017.

I asked Autor to translate that data into language understandable to the layperson, and he wrote back:

There has been almost no increase in the increment to individual earnings for each year of schooling between K and 12 since 1980. It was roughly 6 percentage points per year in 1980, and it still is. The earnings increment for a B.A. has risen from 30.4 percent in 1980 to 50.4 percent in 2000 to 56.4 percent in 2017. The gain to a four-year graduate degree (a Ph.D., for example, but an M.D., J.D., or perhaps even an M.B.A.) relative to high school was approximately 57 percent in 1980, rising to 127 percent in 2017.

These differences result in large part because ever greater levels of skill — critical thinking, problem-solving, originality, strategizing — are needed in a knowledge-based society.

“The idea of a race between education and technology goes back to the Nobel Laureate Jan Tinbergen , who posited that technological change is continually raising skill requirements while education’s job is to supply those rising skill levels,” Autor wrote in explaining the gains for those with higher levels of income. “If technology ‘gets ahead’ of education, the skill premium will tend to rise.”

But something more homely may also be relevant. Several researchers argue that parenting style contributes to where a child ends up in life.

As the skill premium and the economic cost of failing to ascend the education ladder rise in tandem, scholars find that adults are adopting differing parental styles — a crucial form of investment in the human capital of their children — and these differing styles appear to be further entrenching inequality.

Such key factors as the level of inequality, the degree to which higher education is rewarded and the strength of the welfare state are shaping parental strategies in raising children.

In their paper “ The Economics of Parenting ,” three economists, Matthias Doepke at Northwestern, Giuseppe Sorrenti at University of Zurich and Fabrizio Zilibotti at Yale, describe three basic forms of child rearing:

The permissive parenting style is the scenario where the parent lets the child have her way and refrains from interfering in the choices. The authoritarian style is one where the parent imposes her will through coercion. In the model above, coercion is captured through the notion of restricting the choice set. An authoritarian parent chooses a small set that leaves little or no leeway to the child. The third parenting style, authoritative parenting , is also one where the parent aims to affect the child’s choice. However, rather than using coercion, an authoritative parent uses persuasion: she shapes the child’s preferences through investments in the first period of life. For example, such a parent may preach the virtues of patience or the dangers of risk during when the child is little, so that the child ends up with more adultlike preferences when the child’s own decisions matter during adolescence.

There is an “interaction between economic conditions and parenting styles,” Doepke and his colleagues write, resulting in the following patterns:

Consider, first, a low inequality society, where the gap between the top and the bottom is small. In such a society, there is limited incentive for children to put effort into education. Parents are also less concerned about children’s effort, and thus there is little scope for disagreement between parents and children. Therefore, most parents adopt a permissive parenting style, namely, they keep young children happy and foster their sense of independence so that they can discover what they are good at in their adult life.

The authors cite the Scandinavian countries as key examples of this approach.

Authoritarian parenting, in turn, is most common in less-developed, traditional societies where there is little social mobility and children have the same jobs as their parents:

Parents have little incentive to be permissive in order to let children discover what they are good at. Nor do they need to spend effort in socializing children into adultlike values (i.e., to be authoritative) since they can achieve the same result by simply monitoring them.

Finally, they continue, consider “a high-inequality society”:

There, the disagreement between parents and children is more salient, because parents would like to see their children work hard in school and choose professions with a high return to human capital. In this society, a larger share of parents will be authoritative, and fewer will be permissive.

This model, the authors write, fits the United States and China.

There are some clear downsides to this approach:

Because of the comparative advantage of rich and educated parents in authoritative parenting, there will be a stronger socioeconomic sorting into parenting styles. Since an authoritative parenting style is conducive to more economic success, this sorting will hamper social mobility.

Sorrenti elaborated in an email:

In neighborhoods with higher inequality and with less affluent families, parents tend to be, on average, more authoritarian. Our models and additional analyses show that parents tend to be more authoritarian in response to a social environment perceived as more risky or less inspiring for children. On the other hand, the authoritative parenting styles, aimed at molding child preferences, is a typical parenting style gaining more and more consensus in the U.S., also in more affluent families.

What do these analyses suggest for policies designed to raise those on the lowest tiers of income and educational attainment? Doepke, Sorrenti and Zilibotti agree that major investments in training, socialization and preparation for schooling of very young (4 and under) poor children along the lines of proposals by Nobel Laureate James Heckman , an economist at the University of Chicago, and Roland Fryer , a Harvard economist, can prove effective.

In an October 2020 paper , Fryer and three colleagues described

a novel early childhood intervention in which disadvantaged 3-4-year-old children were randomized to receive a new preschool and parent education program focused on cognitive and noncognitive skills or to a control group that did not receive preschool education. In addition to a typical academic year program, we also evaluated a shortened summer version of the program in which children were treated immediately prior to the start of kindergarten. Both programs, including the shortened version, significantly improved cognitive test scores by about one quarter of a standard deviation relative to the control group at the end of the year.

Heckman, in turn, recently wrote on his website:

A critical time to shape productivity is from birth to age five, when the brain develops rapidly to build the foundation of cognitive and character skills necessary for success in school, health, career and life. Early childhood education fosters cognitive skills along with attentiveness, motivation, self-control and sociability — the character skills that turn knowledge into know-how and people into productive citizens.

Doepke agreed:

In the U.S., the big achievement gaps across lines of race or social class open up very early, before kindergarten, rather than during college. So for reducing overall human capital inequality, building high quality early child care and preschool would be the first place to start.

Zilibotti, in turn, wrote in an email:

We view our work as complementary to Heckman’s work. First, one of the tenets of his analysis is that preferences and attitudes are “malleable,” especially so at an early age. This is against the view that people’s success or failure is largely determined by genes. A fundamental part of these early age investments is parental investment. Our work adds the dimension of “how?” to the traditional perspective of “how much?” That said, what we call “authoritative parenting style” is relative to Heckman’s emphasis on noncognitive skills.

The expansion of the Heckman $13,500-per-child test pilot program to a universal national program received strong support in an economic analysis of its costs and benefits by Diego Daruich , an economist at the University of Southern California. He argues in his 2019 paper “ The Macroeconomic Consequences of Early Childhood Development Policies ” that such an enormous government expenditure would produce substantial gains in social welfare, “an income inequality reduction of 7 percent and an increase in intergenerational mobility of 34 percent.”

As the debate over the effectiveness of education in reducing class and racial income differences continues, the Moving to Opportunity project stresses how children under the age of 13 benefit when they and their families move out of neighborhoods of high poverty concentration into more middle-class communities.

In a widely discussed 2015 paper, “The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children,” three Harvard economists, Raj Chetty , Nathaniel Hendren and Katz, wrote:

Moving to a lower-poverty neighborhood significantly improves college attendance rates and earnings for children who were young (below age 13) when their families moved. These children also live in better neighborhoods themselves as adults and are less likely to become single parents. The treatment effects are substantial: children whose families take up an experimental voucher to move to a lower-poverty area when they are less than 13 years old have an annual income that is $3,477 (31 percent) higher on average relative to a mean of $11,270 in the control group in their mid-twenties.

There is a long and daunting history of enduring gaps in scholastic achievement correlated with socioeconomic status in the United States that should temper optimism.

In a February 2020 paper — “ Long-Run Trends in the U.S. SES-Achievement Gap ” — Eric A. Hanushek of the Hoover Institution at Stanford, Paul E. Peterson of Harvard’s Kennedy School, Laura M. Talpey of Stanford’s Institute for Economic Policy Research and Ludger Woessmann of the University of Munich report that over nearly 50 years:

The SES-achievement gap between the top and bottom SES quartiles (75-25 SES gap) has remained essentially flat at roughly 0.9 standard deviations, a gap roughly equivalent to a difference of three years of learning between the average student in the top and bottom quartiles of the distribution.

The virtually unchanging SES-achievement gap, the authors continue, “is confirmed in analyses of the achievement gap by subsidized lunch eligibility and in separate estimations by ethnicity that consider changes in the ethnic composition.”

Their conclusion:

The bottom line of our analysis is simply that — despite all the policy efforts — the gap in achievement between children from high- and low-SES backgrounds has not changed. If the goal is to reduce the dependence of students’ achievement on the socio-economic status of their families, re-evaluating the design and focus of existing policy programs seems appropriate. As long as cognitive skills remain critical for the income and economic well-being of U.S. citizens, the unwavering achievement gaps across the SES spectrum do not bode well for future improvements in intergenerational mobility.

The pessimistic implications of this paper have not deterred those devoted to seeking ways to break embedded patterns of inequality and stagnant mobility.

In a November 2019 essay, “ We Have the Tools to Reverse the Rise in Inequality ,” Olivier Blanchard of the Peterson Institute for International Economics and Dani Rodrik , an economist at Harvard, cited the ready availability of a host of policies with strong support among many economists, political scientists and Democrats:

Many areas have low-hanging fruit: expansion of EITC-type programs, increased public funding of both pre-K and tertiary education; redirection of subsidies to employment-friendly innovation, greater overall progressivity in taxation, and policies to help workers reorganize in the face of new production modes.

Adoption of policies calling for aggressive government intervention raises a crucial question, Autor acknowledged in his email: “whether such interventions would kill the golden goose of U.S. innovation and entrepreneurship.” Autor’s answer:

At this point, I’d say the graver threat is from inaction rather than action. If the citizens of a democracy think that “progress” simply means more inequality and stratification, and rising economic insecurity stemming from technology and globalization, they’re eventually going to “cancel” that plan and demand something else — though those demands may not ultimately lead somewhere constructive (e.g., closing U.S. borders, slapping tariffs on numerous friendly trading partners, and starving the government of tax revenue needed to invest in citizens was never going to lead anywhere good).

A promising approach to the augmentation of human capital lies in the exploration of noncognitive skills — perseverance, punctuality, self-restraint, politeness, thoroughness, postponement of gratification, grit — all of which are increasingly valuable in a service-based economy. Noncognitive skills have proved to be teachable, especially among very young children.

Shelly Lundberg , an economics professor at the University of California-Santa Barbara, cites a range of projects and studies, including the Perry Preschool Project, an intensive program for 3-to-4-year-old low-income children “that had long-term impacts on test scores, adult crime and male income.” The potential gains from raising noncognitive skills are wide-ranging, she writes in a chapter of the December 2018 book “ Education, Skills, and Technical Change: Implications for Future US GDP Growth ”:

Noncognitive skills such as attention and self-control can increase the productivity of educational investments. Disruptive behavior and crime impose negative externalities in schools and communities that increased levels of some noncognitive skills could ameliorate.

But, she cautions,