Types of migration

Forced migration or displacement

Definitions, data sources, further reading.

In studying forced or involuntary migration — sometimes referred to as forced or involuntary displacement — a distinction is often made between conflict-induced and disaster-induced displacement. Displacement induced by conflict is typically referred to as caused by humans, whereas natural causes typically underlay displacement caused by disasters. The definitions of these concepts are useful, but the lines between them may be blurred in practice because conflicts may arise due to disputes over natural resources and human activity may trigger natural disasters such as landslides.

Countries faced with forced displacement — induced by humans or nature — collect data on displaced populations. Such data are typically collected through a combination of population censuses, household surveys, border counts, administrative records, and beneficiary registers.

At the international level, data on forced migration are collected and/or compiled by various intergovernmental organizations (IGOs), such as the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM), as well as non-governmental organizations (NGOs), such as the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC).

Key terms that are used in the context of forced migration or forced/involuntary displacement include:

According to IOM, forced migration is “a migratory movement which, although the drivers can be diverse, involves force, compulsion, or coercion.” 1 The definition includes a note which clarifies that, “While not an international legal concept, this term has been used to describe the movements of refugees, displaced persons (including those displaced by disasters or development projects), and, in some instances, victims of trafficking. At the international level the use of this term is debated because of the widespread recognition that a continuum of agency exists rather than a voluntary/forced dichotomy and that it might undermine the existing legal international protection regime.” ( IOM Glossary on Migration, 2019 ).

According to the 1951 United Nations Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol refugees are persons who flee their country due to "well-founded fear" of persecution due to reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, and who are outside of their country of nationality or permanent residence and due to this fear are unable or unwilling to return to it. UNHCR includes “individuals recognized under the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, its 1967 Protocol, the 1969 Organization of African Unity (OAU) Convention Governing the Specific Aspects of Refugee Problems in Africa, those recognized in accordance with the UNHCR Statute, individuals granted complementary forms of protection, and those enjoying temporary protection. The refugee population also includes people in refugee-like situations." ( UNHCR, 2017 ).

Persons in a refugee-like situation includes “groups of persons who are outside their country or territory of origin and who face protection risks similar to those of refugees, but for whom refugee status has, for practical or other reasons, not been ascertained.” ( UNHCR, 2013 ).

According to UNHCR, asylum-seekers are “individuals who have sought international protection and whose claims for refugee status have not yet been determined” ( 2017 , 56).

Internally displaced persons (IDPs) are defined as “persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized State border.” ( Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement, E/CN.4/1998/53/Add.2. ).

UNHCR introduced the category “ other people in need of international protection ” to reporting in mid-2022, to encompass “people who are outside their country or territory of origin, typically because they have been forcibly displaced across international borders, who have not been reported under other categories (asylum-seekers, refugees, people in refugee-like situations) but who likely need international protection, including protection against forced return, as well as access to basic services on a temporary or longer-term basis”. This category now includes the previously designated category of “Venezuelans displaced abroad” and those not reported in other categories. Retroactive changes have been made in UNHCR’s statistics since 2018 ( 2023, p4 ).

Mixed movement (also called mixed migration or mixed flow) is “a movement in which a number of people are travelling together, generally in an irregular manner, using the same routes and means of transport, but for different reasons. People travelling as part of mixed movements have varying needs and profiles and may include asylum seekers, refugees, trafficked persons, unaccompanied/separated children, and migrants in an irregular situation.” ( IOM Glossary on Migration, 2019 ).

Disaster-induced migration is the displacement of people as a result of “a serious disruption of the functioning of a community or a society involving widespread human, material, economic or environmental losses or impacts, which exceeds the ability of the affected community or society to cope using its own resources.” ( UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, 2009 ).

Resettlement , according to IOM, is the “transfer of refugees from the country in which they have sought protection to another State that has agreed to admit them — as refugees — with permanent residence status.” ( IOM Glossary on Migration, 2019 ). Resettlement programmes are carried out by both IOM and UNHCR.

Key trends

Forced displacement due to persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations or events seriously disturbing public order

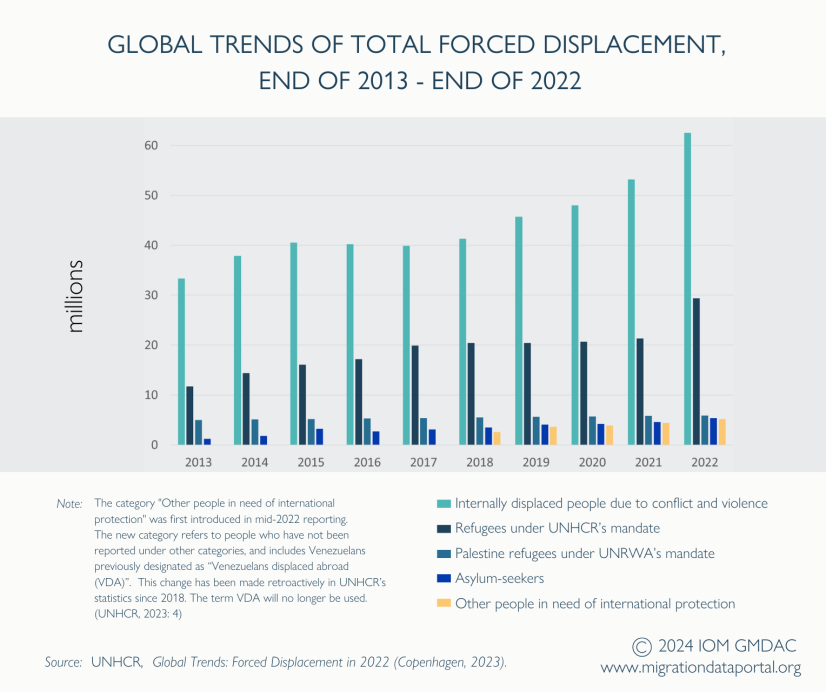

According to UNHCR, the number of forcibly displaced people both within countries and across borders as a result of persecution, conflict, generalized violence, human rights violations or events seriously disturbing public order was more than double the number a decade ago; there were 51.2 million forcibly displaced people as of the end of 2013 ( UNHCR, 2014 ), and the figure was 108.4 million by the end of 2022 ( UNHCR, 2023 ). This represents the highest number available on record and a 21 per cent increase from 2021, the biggest increase ever recorded between years according to UNHCR’s forced displacement statistics ( ibid. ). Almost 90 per cent of forcibly displaced persons in the world are in low- and middle-income countries ( ibid. ).

Refugees (35.3 million) and asylum-seekers (5.4 million) made up nearly 38 per cent of the 108.4 million people forcibly displaced due to persecution, war, conflict, generalized violence, human rights violations or events seriously disturbing public order ( UNHCR, 2023 ). 62.5 million internally displaced people and 5.2 million other people in need of international protection accounted for the remaining 58 per cent and nearly 5 per cent respectively ( ibid. ). These figures show it is important to keep in mind that forcibly displaced persons are not only comprised of refugees and asylum seekers who seek protection in other countries, but also - and indeed mainly - of individuals who have been displaced within the borders of their own countries.

The drastic increase of total forced displacement — both within countries and across borders — as of the end of 2022 compared to the end of 2013 was mainly due to several crises — some already existed, some are new, and some resurfaced after years ( UNHCR, 2023 ). The Russian Federation’s invasion of Ukraine caused 5.7 million people to leave Ukraine, triggering the fastest (and one of the largest) displacement crises since the Second World War, while other nationalities (predominantly Afghans and Venezuelans) were also forced to leave their countries ( ibid. ).

Refugee resettlement

In 2022, UNHCR submitted 116,500 refugee applications for resettlement to states and according to government statistics, 114,300 people were resettled ( UNHCR, 2023 ). This is double the 57,500 resettled in 2021 and a return to pre-COVID-19 pandemic levels ( ibid. ). However, this number is only 7 per cent of the estimated 1.5 million people globally who needed resettlement in 2022 ( ibid. ). 90 per cent of the cases submitted by UNHCR in 2022 were for survivors of torture and/ or violence, people with legal and physical protection needs, and particularly vulnerable women and girls. 52 per cent of the total resettlement submissions were for children ( ibid. ).

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic posed considerable challenges to return migration because of lockdowns, travel restrictions, limited consular services, and other containment measures, and had a decelerating effect on return activities. In 2021, many countries lifted travel restrictions and different types of migration, including return migration, resumed but not to pre-pandemic levels. The number of beneficiaries of IOM’s Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration (AVRR) in 2021 increased by 17 per cent (from 37,043 in 2020 to 43,428 in 2021) ( IOM, 2022 ). The number of beneficiaries of voluntary humanitarian return increased by 57 per cent, from 4,038 in 2020 to 6,367 in 2021. The top 5 host/transit countries for AVRR in 2021 were Niger (10,573), Germany (6,785), Libya (4,332), Greece (2,736), and Morocco (2,372) ( ibid. ).

Forced displacement within countries due to conflict and disasters

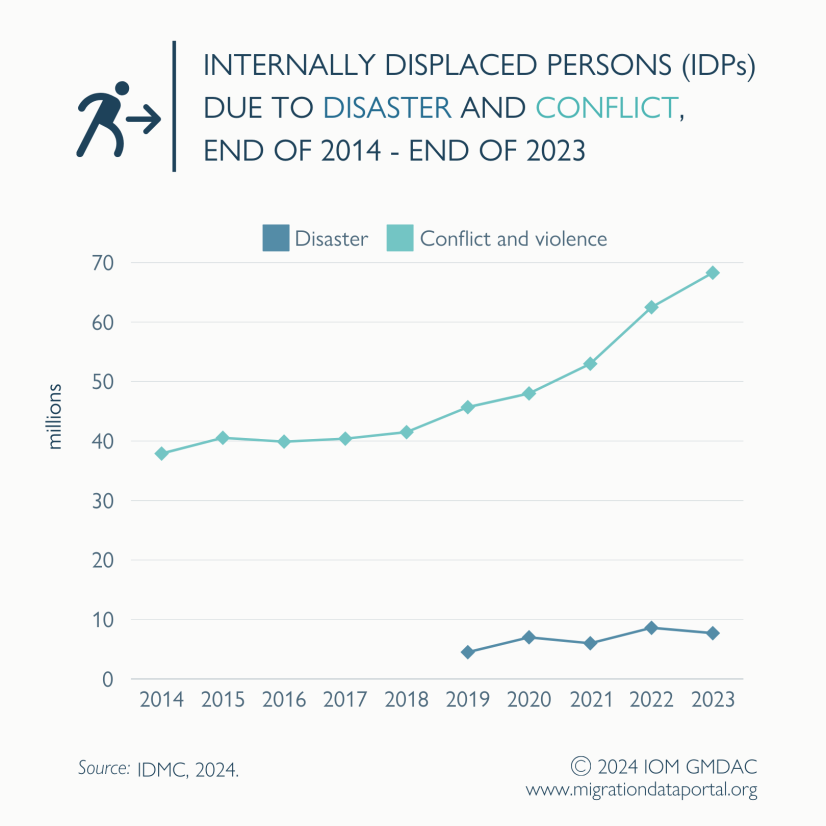

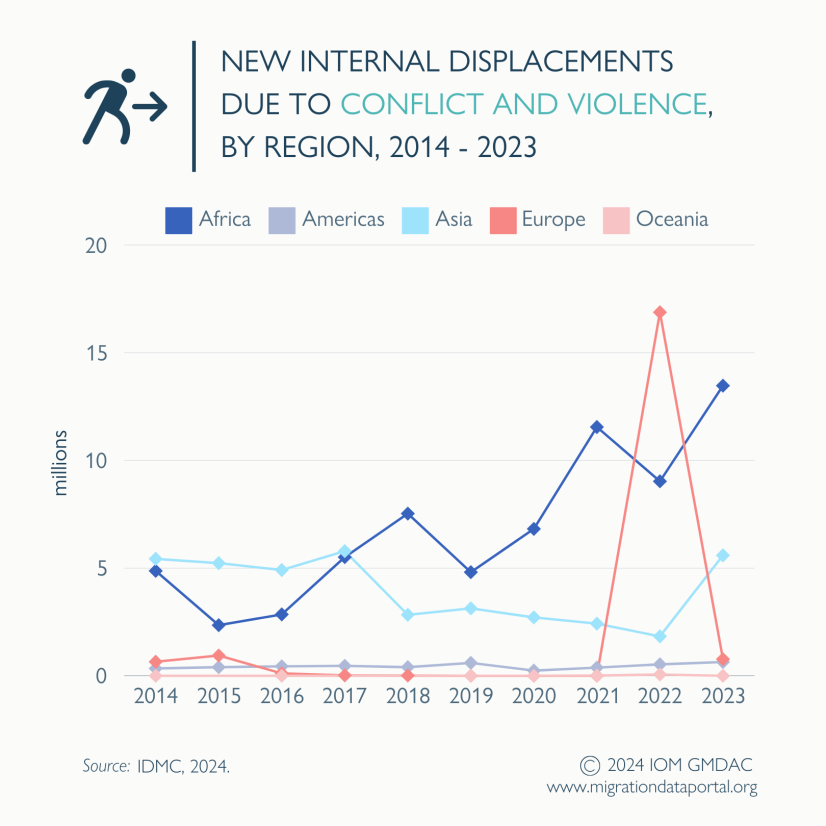

By the end of 2023, 75.9 million people were living in internal displacement as a result of conflict and violence as well as disasters (the stock of internal displacements) ( IDMC, 2024 ). Of this total, 68.3 million people in 66 countries and territories were internally displaced by conflict and violence (a 9% increase from 2022, and a 49% increase in five years), and at least 7.7 million people in 82 countries and territories were internally displaced by disasters (an 11% decrease from 2022, but still the third highest figure within the last decade) ( ibid . ). It is important to note that displacement by conflict and displacement by disaster cannot always be reliably distinguished because many people can be displaced for one reason, and then get displaced for a second or even third time by a different reason.

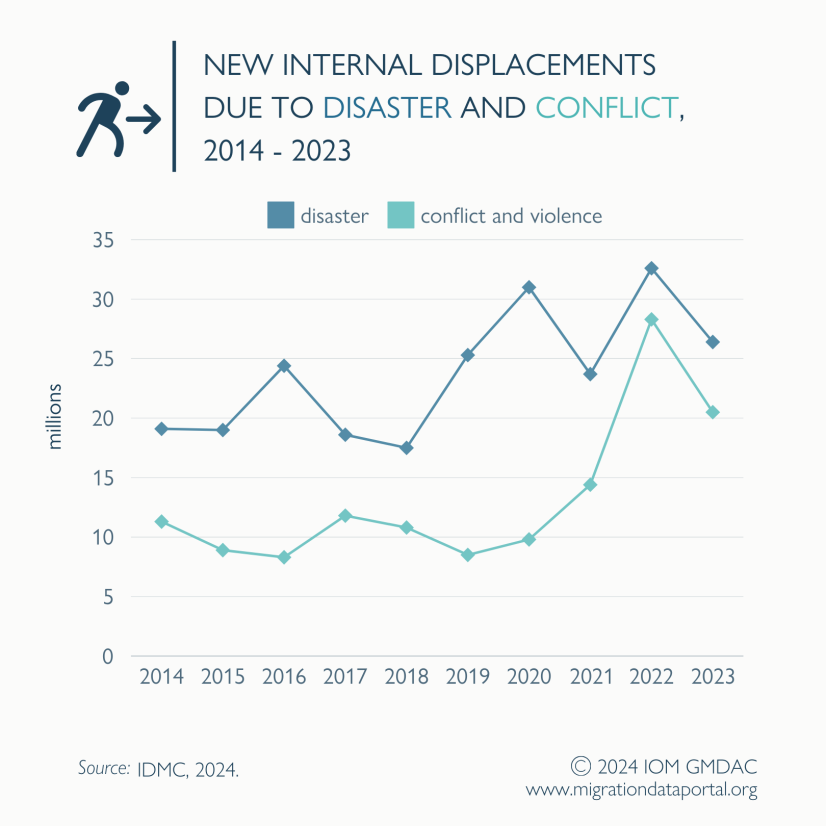

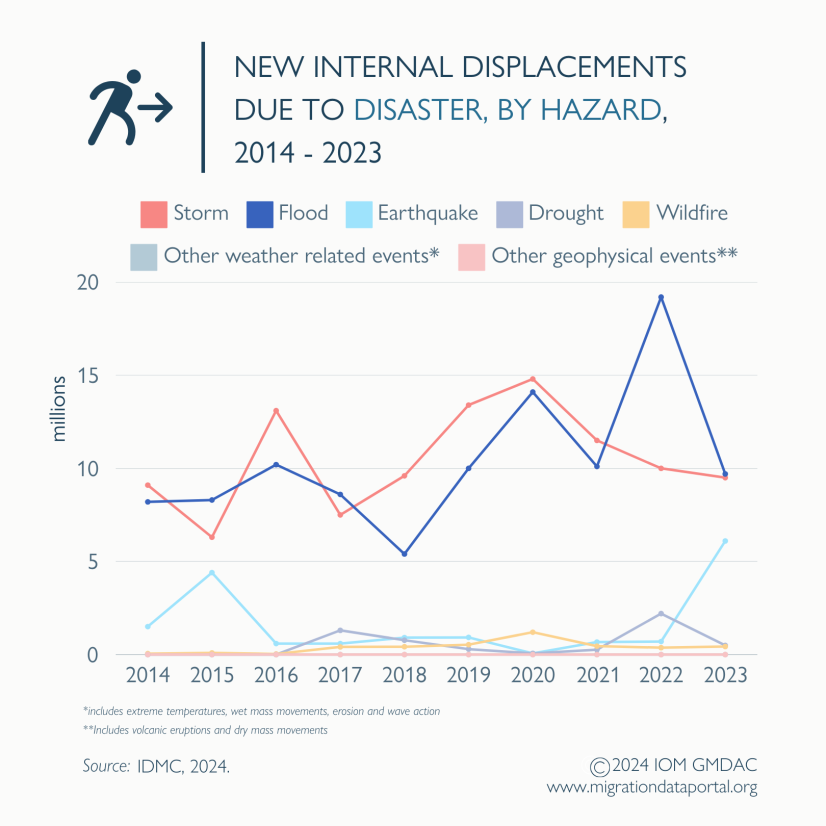

In 2023, there were 46.9 million new internal displacements, across 151 countries and territories ( ibid. ). Disasters triggered 56 per cent (26.4 million) of the new internal displacements recorded; the rest, about 20.5 million, were prompted by conflict and violence ( ibid. ).

In 2023, there were 28 per cent fewer internal conflict displacements in 2023 than in 2022, mostly due to a reduction in movements within Ukraine ( ibid. ). Nevertheless, global internal displacement due to conflict was 70 per cent higher in 2023 than the past decade's annual average ( ibid. ). Approximately half of all internal conflict displacements in 2023 were reported in Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, with 6 million and 3.7 million respectively ( ibid. ). Other countries which experienced large numbers of internal displacement due to conflict were the Occupied Palestinian Territory (3.4 million), Ethiopia (794,000), Ukraine (714,000) and Burkina Faso (707,000) ( ibid. ).

Disaster displacement in 2023 was the third highest figure in the last decade, even though there were one third fewer displacements due to weather-related hazards, partly resulting from La Niña’s end and El Niño’s onset. 77 per cent of the 26.4 million new disaster displacements in 2023 were the result of weather-related hazards such as storms, floods and droughts ( ibid .). Almost a quarter of all internal displacements were due to earthquakes, especially those in Türkiye, Syria, the Philippines, Afghanistan and Morocco ( ibid. ).

In 2023, earthquakes and volcanic activity caused the same number of displacements as the total of the previous seven years ( ibid. ). Some of these earthquakes struck areas where displaced persons from conflict were already living e.g. in Syria and Afghanistan ( ibid. ).

The five countries with the highest number of new internal displacements in 2023 due to disasters were China (4.7 million), , Türkiye (4.1 million), Philippines (2.6 million), Somalia (2 million) and Bangladesh (1.8 million) ( ibid. ).

IOM DTM PROGRESS report found that IDPs tend to be more vulnerable than their host communities ( IOM, 2023 ). Their children are less likely to be in school, and they are more likely to face obstacles in accessing health services, IDP households are less likely than their host communities to have adequate shelter or a stable income. Furthermore, the longer that IDPs are displaced, the less likely they are to return to their community of origin ( ibid. ).

UNHCR collects and provides data on the following types of forcibly displaced persons: refugees (including those in a refugee-like situations), IDPs, asylum seekers, returned refugees, returned IDPs, individuals under UNHCR’s statelessness mandate, and other groups or persons of concern to UNHCR. UNHCR’s Statistics Database provides data disaggregated by persons of concern, year, country of asylum, origin, gender, age, legal status and resettlement. In addition, UNHCR annually produces six main publications with relevant statistics : Global Trends: Forced Displacement , Statistical Yearbooks , Mid-Year Trends , Global Appeal , and Global Report . UNHCR also began a statistics technical series of papers that “make available in a timely fashion research, developments and studies on a variety of topics relevant to the statistical work of UNHCR”.

As the global reference point for data on IDPs, the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) compiles and disseminates data relating to IDPs through its online Global Internal Displacement Database (GIDD). In addition, IDMC produces an annual Global Report on Internal Displacement (GRID), covering internal displacement worldwide due to conflict, violence and disasters.

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) presents data from UN DESA and UNHCR relating to migration, including forced migration specific to children. Data are disaggregated by country of asylum.

IOM collects forced migration data through the Displacement Tracking Matrix (DTM). DTM is a system used to track and monitor displacement and population mobility due to natural disasters and conflict, and is active in over 100 countries. Data are regularly captured, processed and disseminated to provide a better understanding of the movements and evolving needs of displaced populations and migrants, whether on site or en route. Data on conflict- and disaster-induced displacement are presented in the DTM Data Portal . In addition to this, IOM collects data on the number of migrants it assisted and resettled to States offering temporary protection or permanent resettlement. An overview of these data can be found in the annual report on IOM Resettlement or in the IOM Snapshot .

The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) manages the Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX), an open platform for sharing data from a range of partners, which provides nearly 21,000 datasets over 250 locations.

Europe Eurostat provides statistics on various international migration topics , including outcomes of forced migration to Europe. Through its database , Eurostat provides data on the number of refugees, asylum applications, decisions on asylum applications and resettlement, and Dublin statistics within Europe.

Middle East The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) provides assistance and protection for Palestinian refugees in Gaza, Jordan, Lebanon, Syria, the West Bank and the Gaza Strip. The UNRWA in Figures publication releases statistics on the number of Palestinian refugees and refugee camps. Today, over 5 million Palestine refugees have registered with UNRWA.

Americas The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Organization of American States (OAS) together operate the Continuous Reporting System on International Migration in the Americas (SICREMI), which produces biannual reports of collected data from various sources in the Americas Region. The publication provides a short chapter on asylum seeking in the Americas, including data by country of asylum from 2001 to 2015.

The Coordination Platform for Refugees and Migrants from Venezuela (R4V) , established on 12 April 2018, is led and coordinated by UNHCR and IOM. It is aimed at addressing the protection, assistance and integration needs of Venezuelan refugees and migrants in Latin American and Caribbean countries. The website provides cumulative data on pending asylum claims lodged by Venezuelans, recognized refugees from Venezuela and residence permits granted to Venezuelans.

The Worldwide Refugee Admissions Processing System (WRAPS), a system operated by the U.S. Department of State’s Bureau of Population, Refugees and Migration, provides statistics on refugee arrivals and admissions in the United States, by region, state and nationality. In addition, the Office of Immigration Statistics (OIS) produces Annual Flow Reports and Data Tables on refugee and asylum statistics, disaggregated by country of origin, age, sex and marital status.

The Government of Canada’s Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) Department has an Open Government Portal through which information on immigration and citizenship programmes can be found. Specifically, the portal provides monthly statistics on asylum claims, Syrian refugees and resettled refugees.

Australia The Australian Government provides statistics on their humanitarian programme , which include quarterly asylum statistics and yearly asylum trends as well as yearly outcomes for their Offshore Humanitarian programme (refugee visas) and monthly irregular maritime arrivals reports.

Data strengths & limitations

Given the high public interest on forced displacement, complete and reliable data are essential. Existing data provide an indication of refugee and IDP figures globally, but they are based on estimates and varying data collection methods. Data discrepancies can occur due to disaggregation by country of origin or country of asylum only. Often data are lacking information on sex and age.

As one of the largest sources for data on forced displacement, UNHCR provides a unified approach to registering refugees, asylum seekers and IDPs through its Handbook for Registration . The Handbook, which provides guidance and operational standards for registration, among other topics, is useful for UNHCR staff and governmental and non-governmental partners who independently operate camps.

Many forced (and/or mixed) migration movements are monitored through population movement tracking systems, which provide rough estimates of such population flows. Organizations such as UNHCR, IOM, and the Danish Refugee Council (DRC) have such tracking systems in place to monitor the movements of mixed migration flows and IDPs. However, such movement tracking systems are subject to caveats including but not limited to: massive population flows that overwhelm capacity; limited access to certain routes and locations due to instability; unwillingness of individuals to provide information when there is no assistance being offered; and political pressures to suppress accurate reporting on IDP movements ( Sarzin, 2017 ).

Data collection of forced or mixed migration movements, where refugees move alongside irregular migrants or via irregular migration routes, can be difficult and scarce because of the clandestine nature of such migration and the various motives for migrating ( GMG, 2017 ). The identification of individuals in need of protection also becomes challenging as many refugees travel together alongside migrants underway for work or other reasons ( ibid .). As more resources are needed in order to collect such data, governments tend to only collect data on forced migration in developed countries ( Sarzin, 2017 ).

In regard to collecting data relating to IDPs and other forcibly displaced persons, the problem of inconsistent definitions and methodologies arises. Inconsistent definitions and methodologies across countries, organizations and movement tracking systems can produce different totals, resulting in data that are not comparable ( World Bank, 2017 ). In order to curb such inconsistencies, the Humanitarian Data Exchange (HDX), founded in 2014 by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), and IDMC have been advocating for data interoperability, which describes the extent to which computer systems and devices can exchange data and interpret that shared data. The former has been advocating for this for the last 20 years. Both agencies are actively committed to advocating for data interoperability through the Grand Bargain .

- 1 Other organizations may refer to other terms, such as forced displacement.

Explore our new directory of initiatives at the forefront of using data innovation to improve data on migration.

Immigration & emigration statistics

Since 2014, more than 4,000 fatalities have been recorded annually on migratory routes worldwide. 2023 marked the deadliest year with more than 8,000 deaths recorded, marking a decade of documenting...

Under international law, migrants have human rights by virtue of their humanity. International customary law and international human rights instruments are of universal application and therefore set...

Quantifying environmental migration is challenging given the multiple drivers of such movement, related methodological challenges and the lack of data collection standards. Some quantitative data...

The crime of human trafficking is complex and dynamic, taking place in a wide variety of contexts and difficult to detect. One of the greatest challenges in developing targeted counter-trafficking...

Reliable statistics on stocks or flows of irregular migrants, the well-being of migrants in irregular situations, or the extent to which they have access to services such as health and education, are...

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Browse content in A - General Economics and Teaching

- Browse content in A1 - General Economics

- A10 - General

- A11 - Role of Economics; Role of Economists; Market for Economists

- A12 - Relation of Economics to Other Disciplines

- A13 - Relation of Economics to Social Values

- A14 - Sociology of Economics

- Browse content in A2 - Economic Education and Teaching of Economics

- A20 - General

- A23 - Graduate

- Browse content in A3 - Collective Works

- A31 - Collected Writings of Individuals

- Browse content in B - History of Economic Thought, Methodology, and Heterodox Approaches

- Browse content in B0 - General

- B00 - General

- Browse content in B1 - History of Economic Thought through 1925

- B10 - General

- B12 - Classical (includes Adam Smith)

- B16 - History of Economic Thought: Quantitative and Mathematical

- Browse content in B2 - History of Economic Thought since 1925

- B22 - Macroeconomics

- B26 - Financial Economics

- B27 - International Trade and Finance

- B29 - Other

- Browse content in B3 - History of Economic Thought: Individuals

- B31 - Individuals

- Browse content in B4 - Economic Methodology

- B40 - General

- B41 - Economic Methodology

- Browse content in B5 - Current Heterodox Approaches

- B50 - General

- B52 - Institutional; Evolutionary

- B54 - Feminist Economics

- B55 - Social Economics

- Browse content in C - Mathematical and Quantitative Methods

- Browse content in C0 - General

- C02 - Mathematical Methods

- Browse content in C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods and Methodology: General

- C10 - General

- C11 - Bayesian Analysis: General

- C13 - Estimation: General

- C14 - Semiparametric and Nonparametric Methods: General

- C15 - Statistical Simulation Methods: General

- Browse content in C2 - Single Equation Models; Single Variables

- C20 - General

- C21 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions

- C22 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes

- C23 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- C3 - Multiple or Simultaneous Equation Models; Multiple Variables

- Browse content in C4 - Econometric and Statistical Methods: Special Topics

- C45 - Neural Networks and Related Topics

- Browse content in C5 - Econometric Modeling

- C50 - General

- C51 - Model Construction and Estimation

- C53 - Forecasting and Prediction Methods; Simulation Methods

- C54 - Quantitative Policy Modeling

- C55 - Large Data Sets: Modeling and Analysis

- Browse content in C6 - Mathematical Methods; Programming Models; Mathematical and Simulation Modeling

- C61 - Optimization Techniques; Programming Models; Dynamic Analysis

- C63 - Computational Techniques; Simulation Modeling

- C68 - Computable General Equilibrium Models

- Browse content in C7 - Game Theory and Bargaining Theory

- C72 - Noncooperative Games

- C78 - Bargaining Theory; Matching Theory

- Browse content in C8 - Data Collection and Data Estimation Methodology; Computer Programs

- C80 - General

- C81 - Methodology for Collecting, Estimating, and Organizing Microeconomic Data; Data Access

- C88 - Other Computer Software

- Browse content in C9 - Design of Experiments

- C90 - General

- C93 - Field Experiments

- Browse content in D - Microeconomics

- Browse content in D0 - General

- D00 - General

- D01 - Microeconomic Behavior: Underlying Principles

- D02 - Institutions: Design, Formation, Operations, and Impact

- D03 - Behavioral Microeconomics: Underlying Principles

- D04 - Microeconomic Policy: Formulation; Implementation, and Evaluation

- Browse content in D1 - Household Behavior and Family Economics

- D10 - General

- D12 - Consumer Economics: Empirical Analysis

- D14 - Household Saving; Personal Finance

- D15 - Intertemporal Household Choice: Life Cycle Models and Saving

- D18 - Consumer Protection

- Browse content in D2 - Production and Organizations

- D21 - Firm Behavior: Theory

- D22 - Firm Behavior: Empirical Analysis

- D23 - Organizational Behavior; Transaction Costs; Property Rights

- D24 - Production; Cost; Capital; Capital, Total Factor, and Multifactor Productivity; Capacity

- Browse content in D3 - Distribution

- D30 - General

- D31 - Personal Income, Wealth, and Their Distributions

- D33 - Factor Income Distribution

- Browse content in D4 - Market Structure, Pricing, and Design

- D40 - General

- D42 - Monopoly

- D43 - Oligopoly and Other Forms of Market Imperfection

- D44 - Auctions

- D45 - Rationing; Licensing

- D47 - Market Design

- Browse content in D5 - General Equilibrium and Disequilibrium

- D50 - General

- D51 - Exchange and Production Economies

- D53 - Financial Markets

- D57 - Input-Output Tables and Analysis

- D58 - Computable and Other Applied General Equilibrium Models

- Browse content in D6 - Welfare Economics

- D60 - General

- D61 - Allocative Efficiency; Cost-Benefit Analysis

- D62 - Externalities

- D63 - Equity, Justice, Inequality, and Other Normative Criteria and Measurement

- D64 - Altruism; Philanthropy

- D69 - Other

- Browse content in D7 - Analysis of Collective Decision-Making

- D70 - General

- D71 - Social Choice; Clubs; Committees; Associations

- D72 - Political Processes: Rent-seeking, Lobbying, Elections, Legislatures, and Voting Behavior

- D73 - Bureaucracy; Administrative Processes in Public Organizations; Corruption

- D74 - Conflict; Conflict Resolution; Alliances; Revolutions

- D78 - Positive Analysis of Policy Formulation and Implementation

- Browse content in D8 - Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty

- D81 - Criteria for Decision-Making under Risk and Uncertainty

- D82 - Asymmetric and Private Information; Mechanism Design

- D83 - Search; Learning; Information and Knowledge; Communication; Belief; Unawareness

- D84 - Expectations; Speculations

- D85 - Network Formation and Analysis: Theory

- D86 - Economics of Contract: Theory

- Browse content in D9 - Micro-Based Behavioral Economics

- D90 - General

- D91 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making

- D92 - Intertemporal Firm Choice, Investment, Capacity, and Financing

- Browse content in E - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Browse content in E0 - General

- E00 - General

- E01 - Measurement and Data on National Income and Product Accounts and Wealth; Environmental Accounts

- E02 - Institutions and the Macroeconomy

- E03 - Behavioral Macroeconomics

- Browse content in E1 - General Aggregative Models

- E10 - General

- E12 - Keynes; Keynesian; Post-Keynesian

- E13 - Neoclassical

- E17 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Investment, Labor Markets, and Informal Economy

- E21 - Consumption; Saving; Wealth

- E22 - Investment; Capital; Intangible Capital; Capacity

- E23 - Production

- E24 - Employment; Unemployment; Wages; Intergenerational Income Distribution; Aggregate Human Capital; Aggregate Labor Productivity

- E25 - Aggregate Factor Income Distribution

- E26 - Informal Economy; Underground Economy

- E27 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E3 - Prices, Business Fluctuations, and Cycles

- E30 - General

- E31 - Price Level; Inflation; Deflation

- E32 - Business Fluctuations; Cycles

- E37 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E4 - Money and Interest Rates

- E40 - General

- E42 - Monetary Systems; Standards; Regimes; Government and the Monetary System; Payment Systems

- E43 - Interest Rates: Determination, Term Structure, and Effects

- E44 - Financial Markets and the Macroeconomy

- E47 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and Credit

- E50 - General

- E51 - Money Supply; Credit; Money Multipliers

- E52 - Monetary Policy

- E58 - Central Banks and Their Policies

- Browse content in E6 - Macroeconomic Policy, Macroeconomic Aspects of Public Finance, and General Outlook

- E60 - General

- E61 - Policy Objectives; Policy Designs and Consistency; Policy Coordination

- E62 - Fiscal Policy

- E63 - Comparative or Joint Analysis of Fiscal and Monetary Policy; Stabilization; Treasury Policy

- E64 - Incomes Policy; Price Policy

- E65 - Studies of Particular Policy Episodes

- E66 - General Outlook and Conditions

- Browse content in F - International Economics

- Browse content in F0 - General

- F00 - General

- F02 - International Economic Order and Integration

- Browse content in F1 - Trade

- F10 - General

- F11 - Neoclassical Models of Trade

- F12 - Models of Trade with Imperfect Competition and Scale Economies; Fragmentation

- F13 - Trade Policy; International Trade Organizations

- F14 - Empirical Studies of Trade

- F15 - Economic Integration

- F16 - Trade and Labor Market Interactions

- F17 - Trade Forecasting and Simulation

- F18 - Trade and Environment

- Browse content in F2 - International Factor Movements and International Business

- F20 - General

- F21 - International Investment; Long-Term Capital Movements

- F22 - International Migration

- F23 - Multinational Firms; International Business

- F24 - Remittances

- F29 - Other

- Browse content in F3 - International Finance

- F30 - General

- F31 - Foreign Exchange

- F32 - Current Account Adjustment; Short-Term Capital Movements

- F33 - International Monetary Arrangements and Institutions

- F34 - International Lending and Debt Problems

- F35 - Foreign Aid

- F36 - Financial Aspects of Economic Integration

- F37 - International Finance Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- F38 - International Financial Policy: Financial Transactions Tax; Capital Controls

- Browse content in F4 - Macroeconomic Aspects of International Trade and Finance

- F40 - General

- F41 - Open Economy Macroeconomics

- F42 - International Policy Coordination and Transmission

- F43 - Economic Growth of Open Economies

- F45 - Macroeconomic Issues of Monetary Unions

- F47 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in F5 - International Relations, National Security, and International Political Economy

- F50 - General

- F51 - International Conflicts; Negotiations; Sanctions

- F52 - National Security; Economic Nationalism

- F53 - International Agreements and Observance; International Organizations

- F55 - International Institutional Arrangements

- F59 - Other

- Browse content in F6 - Economic Impacts of Globalization

- F60 - General

- F61 - Microeconomic Impacts

- F62 - Macroeconomic Impacts

- F63 - Economic Development

- F64 - Environment

- F65 - Finance

- F66 - Labor

- F68 - Policy

- F69 - Other

- Browse content in G - Financial Economics

- Browse content in G0 - General

- G01 - Financial Crises

- Browse content in G1 - General Financial Markets

- G10 - General

- G11 - Portfolio Choice; Investment Decisions

- G12 - Asset Pricing; Trading volume; Bond Interest Rates

- G13 - Contingent Pricing; Futures Pricing

- G14 - Information and Market Efficiency; Event Studies; Insider Trading

- G15 - International Financial Markets

- G17 - Financial Forecasting and Simulation

- G18 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G2 - Financial Institutions and Services

- G20 - General

- G21 - Banks; Depository Institutions; Micro Finance Institutions; Mortgages

- G22 - Insurance; Insurance Companies; Actuarial Studies

- G23 - Non-bank Financial Institutions; Financial Instruments; Institutional Investors

- G24 - Investment Banking; Venture Capital; Brokerage; Ratings and Ratings Agencies

- G28 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in G3 - Corporate Finance and Governance

- G31 - Capital Budgeting; Fixed Investment and Inventory Studies; Capacity

- G32 - Financing Policy; Financial Risk and Risk Management; Capital and Ownership Structure; Value of Firms; Goodwill

- G33 - Bankruptcy; Liquidation

- G34 - Mergers; Acquisitions; Restructuring; Corporate Governance

- G35 - Payout Policy

- G38 - Government Policy and Regulation

- G39 - Other

- Browse content in G4 - Behavioral Finance

- G41 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making in Financial Markets

- Browse content in G5 - Household Finance

- G50 - General

- G51 - Household Saving, Borrowing, Debt, and Wealth

- Browse content in H - Public Economics

- Browse content in H0 - General

- H00 - General

- Browse content in H1 - Structure and Scope of Government

- H10 - General

- H11 - Structure, Scope, and Performance of Government

- H12 - Crisis Management

- H13 - Economics of Eminent Domain; Expropriation; Nationalization

- Browse content in H2 - Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H20 - General

- H21 - Efficiency; Optimal Taxation

- H22 - Incidence

- H23 - Externalities; Redistributive Effects; Environmental Taxes and Subsidies

- H24 - Personal Income and Other Nonbusiness Taxes and Subsidies; includes inheritance and gift taxes

- H25 - Business Taxes and Subsidies

- H26 - Tax Evasion and Avoidance

- H29 - Other

- Browse content in H3 - Fiscal Policies and Behavior of Economic Agents

- H30 - General

- H31 - Household

- Browse content in H4 - Publicly Provided Goods

- H41 - Public Goods

- H43 - Project Evaluation; Social Discount Rate

- H44 - Publicly Provided Goods: Mixed Markets

- Browse content in H5 - National Government Expenditures and Related Policies

- H50 - General

- H51 - Government Expenditures and Health

- H52 - Government Expenditures and Education

- H53 - Government Expenditures and Welfare Programs

- H54 - Infrastructures; Other Public Investment and Capital Stock

- H55 - Social Security and Public Pensions

- H56 - National Security and War

- H57 - Procurement

- Browse content in H6 - National Budget, Deficit, and Debt

- H60 - General

- H62 - Deficit; Surplus

- H63 - Debt; Debt Management; Sovereign Debt

- H68 - Forecasts of Budgets, Deficits, and Debt

- H69 - Other

- Browse content in H7 - State and Local Government; Intergovernmental Relations

- H70 - General

- H71 - State and Local Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H73 - Interjurisdictional Differentials and Their Effects

- H75 - State and Local Government: Health; Education; Welfare; Public Pensions

- H77 - Intergovernmental Relations; Federalism; Secession

- Browse content in H8 - Miscellaneous Issues

- H81 - Governmental Loans; Loan Guarantees; Credits; Grants; Bailouts

- H83 - Public Administration; Public Sector Accounting and Audits

- H84 - Disaster Aid

- H87 - International Fiscal Issues; International Public Goods

- Browse content in I - Health, Education, and Welfare

- Browse content in I0 - General

- I00 - General

- Browse content in I1 - Health

- I10 - General

- I11 - Analysis of Health Care Markets

- I12 - Health Behavior

- I14 - Health and Inequality

- I15 - Health and Economic Development

- I18 - Government Policy; Regulation; Public Health

- I19 - Other

- Browse content in I2 - Education and Research Institutions

- I20 - General

- I21 - Analysis of Education

- I23 - Higher Education; Research Institutions

- I24 - Education and Inequality

- I26 - Returns to Education

- I28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in I3 - Welfare, Well-Being, and Poverty

- I30 - General

- I31 - General Welfare

- I32 - Measurement and Analysis of Poverty

- I38 - Government Policy; Provision and Effects of Welfare Programs

- Browse content in J - Labor and Demographic Economics

- Browse content in J0 - General

- J00 - General

- J01 - Labor Economics: General

- J08 - Labor Economics Policies

- Browse content in J1 - Demographic Economics

- J11 - Demographic Trends, Macroeconomic Effects, and Forecasts

- J12 - Marriage; Marital Dissolution; Family Structure; Domestic Abuse

- J13 - Fertility; Family Planning; Child Care; Children; Youth

- J14 - Economics of the Elderly; Economics of the Handicapped; Non-Labor Market Discrimination

- J15 - Economics of Minorities, Races, Indigenous Peoples, and Immigrants; Non-labor Discrimination

- J16 - Economics of Gender; Non-labor Discrimination

- J17 - Value of Life; Forgone Income

- J18 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J2 - Demand and Supply of Labor

- J20 - General

- J21 - Labor Force and Employment, Size, and Structure

- J22 - Time Allocation and Labor Supply

- J23 - Labor Demand

- J24 - Human Capital; Skills; Occupational Choice; Labor Productivity

- J26 - Retirement; Retirement Policies

- J28 - Safety; Job Satisfaction; Related Public Policy

- Browse content in J3 - Wages, Compensation, and Labor Costs

- J31 - Wage Level and Structure; Wage Differentials

- J33 - Compensation Packages; Payment Methods

- J38 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J4 - Particular Labor Markets

- J40 - General

- J41 - Labor Contracts

- J44 - Professional Labor Markets; Occupational Licensing

- J46 - Informal Labor Markets

- J48 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J5 - Labor-Management Relations, Trade Unions, and Collective Bargaining

- J58 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J6 - Mobility, Unemployment, Vacancies, and Immigrant Workers

- J60 - General

- J61 - Geographic Labor Mobility; Immigrant Workers

- J62 - Job, Occupational, and Intergenerational Mobility

- J63 - Turnover; Vacancies; Layoffs

- J64 - Unemployment: Models, Duration, Incidence, and Job Search

- J65 - Unemployment Insurance; Severance Pay; Plant Closings

- J68 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J7 - Labor Discrimination

- J70 - General

- J71 - Discrimination

- Browse content in J8 - Labor Standards: National and International

- J88 - Public Policy

- Browse content in K - Law and Economics

- Browse content in K0 - General

- K00 - General

- Browse content in K1 - Basic Areas of Law

- K10 - General

- K11 - Property Law

- K12 - Contract Law

- Browse content in K2 - Regulation and Business Law

- K20 - General

- K21 - Antitrust Law

- K22 - Business and Securities Law

- K29 - Other

- Browse content in K3 - Other Substantive Areas of Law

- K31 - Labor Law

- K32 - Environmental, Health, and Safety Law

- K33 - International Law

- K34 - Tax Law

- K37 - Immigration Law

- K38 - Human Rights Law: Gender Law

- Browse content in K4 - Legal Procedure, the Legal System, and Illegal Behavior

- K40 - General

- K41 - Litigation Process

- K42 - Illegal Behavior and the Enforcement of Law

- K49 - Other

- Browse content in L - Industrial Organization

- Browse content in L1 - Market Structure, Firm Strategy, and Market Performance

- L11 - Production, Pricing, and Market Structure; Size Distribution of Firms

- L12 - Monopoly; Monopolization Strategies

- L13 - Oligopoly and Other Imperfect Markets

- L14 - Transactional Relationships; Contracts and Reputation; Networks

- L16 - Industrial Organization and Macroeconomics: Industrial Structure and Structural Change; Industrial Price Indices

- Browse content in L2 - Firm Objectives, Organization, and Behavior

- L21 - Business Objectives of the Firm

- L22 - Firm Organization and Market Structure

- L24 - Contracting Out; Joint Ventures; Technology Licensing

- L25 - Firm Performance: Size, Diversification, and Scope

- L26 - Entrepreneurship

- Browse content in L3 - Nonprofit Organizations and Public Enterprise

- L31 - Nonprofit Institutions; NGOs; Social Entrepreneurship

- L33 - Comparison of Public and Private Enterprises and Nonprofit Institutions; Privatization; Contracting Out

- L38 - Public Policy

- Browse content in L4 - Antitrust Issues and Policies

- L40 - General

- L41 - Monopolization; Horizontal Anticompetitive Practices

- L42 - Vertical Restraints; Resale Price Maintenance; Quantity Discounts

- Browse content in L5 - Regulation and Industrial Policy

- L50 - General

- L51 - Economics of Regulation

- L52 - Industrial Policy; Sectoral Planning Methods

- L53 - Enterprise Policy

- L59 - Other

- Browse content in L6 - Industry Studies: Manufacturing

- L60 - General

- L65 - Chemicals; Rubber; Drugs; Biotechnology

- Browse content in L7 - Industry Studies: Primary Products and Construction

- L71 - Mining, Extraction, and Refining: Hydrocarbon Fuels

- Browse content in L8 - Industry Studies: Services

- L80 - General

- L81 - Retail and Wholesale Trade; e-Commerce

- L86 - Information and Internet Services; Computer Software

- L88 - Government Policy

- Browse content in L9 - Industry Studies: Transportation and Utilities

- L90 - General

- L92 - Railroads and Other Surface Transportation

- L94 - Electric Utilities

- L98 - Government Policy

- Browse content in M - Business Administration and Business Economics; Marketing; Accounting; Personnel Economics

- Browse content in M1 - Business Administration

- M10 - General

- M11 - Production Management

- M12 - Personnel Management; Executives; Executive Compensation

- M13 - New Firms; Startups

- M14 - Corporate Culture; Social Responsibility

- M16 - International Business Administration

- M2 - Business Economics

- Browse content in M4 - Accounting and Auditing

- M41 - Accounting

- M42 - Auditing

- M48 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in M5 - Personnel Economics

- M50 - General

- M51 - Firm Employment Decisions; Promotions

- M53 - Training

- M54 - Labor Management

- Browse content in N - Economic History

- Browse content in N1 - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics; Industrial Structure; Growth; Fluctuations

- N10 - General, International, or Comparative

- N12 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N13 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N14 - Europe: 1913-

- Browse content in N2 - Financial Markets and Institutions

- N20 - General, International, or Comparative

- N23 - Europe: Pre-1913

- Browse content in N3 - Labor and Consumers, Demography, Education, Health, Welfare, Income, Wealth, Religion, and Philanthropy

- N33 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N34 - Europe: 1913-

- N36 - Latin America; Caribbean

- N37 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N4 - Government, War, Law, International Relations, and Regulation

- N44 - Europe: 1913-

- Browse content in N5 - Agriculture, Natural Resources, Environment, and Extractive Industries

- N55 - Asia including Middle East

- Browse content in N6 - Manufacturing and Construction

- N60 - General, International, or Comparative

- N64 - Europe: 1913-

- Browse content in N7 - Transport, Trade, Energy, Technology, and Other Services

- N70 - General, International, or Comparative

- Browse content in N9 - Regional and Urban History

- N94 - Europe: 1913-

- Browse content in O - Economic Development, Innovation, Technological Change, and Growth

- Browse content in O1 - Economic Development

- O10 - General

- O11 - Macroeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O12 - Microeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O13 - Agriculture; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Other Primary Products

- O14 - Industrialization; Manufacturing and Service Industries; Choice of Technology

- O15 - Human Resources; Human Development; Income Distribution; Migration

- O16 - Financial Markets; Saving and Capital Investment; Corporate Finance and Governance

- O17 - Formal and Informal Sectors; Shadow Economy; Institutional Arrangements

- O18 - Urban, Rural, Regional, and Transportation Analysis; Housing; Infrastructure

- O19 - International Linkages to Development; Role of International Organizations

- Browse content in O2 - Development Planning and Policy

- O20 - General

- O21 - Planning Models; Planning Policy

- O22 - Project Analysis

- O23 - Fiscal and Monetary Policy in Development

- O24 - Trade Policy; Factor Movement Policy; Foreign Exchange Policy

- O25 - Industrial Policy

- Browse content in O3 - Innovation; Research and Development; Technological Change; Intellectual Property Rights

- O30 - General

- O31 - Innovation and Invention: Processes and Incentives

- O32 - Management of Technological Innovation and R&D

- O33 - Technological Change: Choices and Consequences; Diffusion Processes

- O34 - Intellectual Property and Intellectual Capital

- O35 - Social Innovation

- O38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in O4 - Economic Growth and Aggregate Productivity

- O40 - General

- O41 - One, Two, and Multisector Growth Models

- O42 - Monetary Growth Models

- O43 - Institutions and Growth

- O44 - Environment and Growth

- O47 - Empirical Studies of Economic Growth; Aggregate Productivity; Cross-Country Output Convergence

- O49 - Other

- Browse content in O5 - Economywide Country Studies

- O51 - U.S.; Canada

- O52 - Europe

- O53 - Asia including Middle East

- O55 - Africa

- O57 - Comparative Studies of Countries

- Browse content in P - Economic Systems

- Browse content in P0 - General

- P00 - General

- Browse content in P1 - Capitalist Systems

- P10 - General

- P12 - Capitalist Enterprises

- P14 - Property Rights

- P16 - Political Economy

- P2 - Socialist Systems and Transitional Economies

- Browse content in P3 - Socialist Institutions and Their Transitions

- P30 - General

- P36 - Consumer Economics; Health; Education and Training; Welfare, Income, Wealth, and Poverty

- Browse content in P4 - Other Economic Systems

- P46 - Consumer Economics; Health; Education and Training; Welfare, Income, Wealth, and Poverty

- P48 - Political Economy; Legal Institutions; Property Rights; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Regional Studies

- Browse content in P5 - Comparative Economic Systems

- P50 - General

- P51 - Comparative Analysis of Economic Systems

- Browse content in Q - Agricultural and Natural Resource Economics; Environmental and Ecological Economics

- Browse content in Q0 - General

- Q00 - General

- Q01 - Sustainable Development

- Q02 - Commodity Markets

- Browse content in Q1 - Agriculture

- Q10 - General

- Q11 - Aggregate Supply and Demand Analysis; Prices

- Q12 - Micro Analysis of Farm Firms, Farm Households, and Farm Input Markets

- Q13 - Agricultural Markets and Marketing; Cooperatives; Agribusiness

- Q14 - Agricultural Finance

- Q15 - Land Ownership and Tenure; Land Reform; Land Use; Irrigation; Agriculture and Environment

- Q17 - Agriculture in International Trade

- Q18 - Agricultural Policy; Food Policy

- Browse content in Q2 - Renewable Resources and Conservation

- Q20 - General

- Q21 - Demand and Supply; Prices

- Q23 - Forestry

- Q25 - Water

- Q27 - Issues in International Trade

- Q28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in Q3 - Nonrenewable Resources and Conservation

- Q30 - General

- Q32 - Exhaustible Resources and Economic Development

- Q33 - Resource Booms

- Q34 - Natural Resources and Domestic and International Conflicts

- Q35 - Hydrocarbon Resources

- Q38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in Q4 - Energy

- Q40 - General

- Q41 - Demand and Supply; Prices

- Q42 - Alternative Energy Sources

- Q43 - Energy and the Macroeconomy

- Q48 - Government Policy

- Browse content in Q5 - Environmental Economics

- Q50 - General

- Q51 - Valuation of Environmental Effects

- Q52 - Pollution Control Adoption Costs; Distributional Effects; Employment Effects

- Q53 - Air Pollution; Water Pollution; Noise; Hazardous Waste; Solid Waste; Recycling

- Q54 - Climate; Natural Disasters; Global Warming

- Q55 - Technological Innovation

- Q56 - Environment and Development; Environment and Trade; Sustainability; Environmental Accounts and Accounting; Environmental Equity; Population Growth

- Q57 - Ecological Economics: Ecosystem Services; Biodiversity Conservation; Bioeconomics; Industrial Ecology

- Q58 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R - Urban, Rural, Regional, Real Estate, and Transportation Economics

- Browse content in R1 - General Regional Economics

- R10 - General

- R11 - Regional Economic Activity: Growth, Development, Environmental Issues, and Changes

- R12 - Size and Spatial Distributions of Regional Economic Activity

- R14 - Land Use Patterns

- Browse content in R2 - Household Analysis

- R21 - Housing Demand

- R23 - Regional Migration; Regional Labor Markets; Population; Neighborhood Characteristics

- R28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R3 - Real Estate Markets, Spatial Production Analysis, and Firm Location

- R30 - General

- R31 - Housing Supply and Markets

- R32 - Other Spatial Production and Pricing Analysis

- R38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R4 - Transportation Economics

- R40 - General

- R41 - Transportation: Demand, Supply, and Congestion; Travel Time; Safety and Accidents; Transportation Noise

- R42 - Government and Private Investment Analysis; Road Maintenance; Transportation Planning

- R48 - Government Pricing and Policy

- Browse content in R5 - Regional Government Analysis

- R50 - General

- R51 - Finance in Urban and Rural Economies

- R52 - Land Use and Other Regulations

- R53 - Public Facility Location Analysis; Public Investment and Capital Stock

- R58 - Regional Development Planning and Policy

- Browse content in Z - Other Special Topics

- Browse content in Z1 - Cultural Economics; Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology

- Z13 - Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology; Social and Economic Stratification

- Z18 - Public Policy

- Author Guidelines

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Oxford Review of Economic Policy

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, part i: refugees and international mechanisms, part ii: refugees and the macroeconomy, part iii: host labour markets and host communities, part iv: recovery, resilience, and return, postscript: the ukrainian crisis, the path ahead, forced migration: evidence and policy challenges.

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Simon Quinn, Isabel Ruiz, Forced migration: evidence and policy challenges, Oxford Review of Economic Policy , Volume 38, Issue 3, Autumn 2022, Pages 403–413, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxrep/grac025

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This paper presents a summary assessment of this issue of the Oxford Review of Economic Policy , on forced migration. The issue is concerned with four important questions: (i) What are the general mechanisms by which forced migrants should be managed, and what frameworks should be used for supporting them? (ii) How can policy help refugees integrate into host economies; and what are the likely consequences of this integration? (iii) How are host communities likely to respond to the influx of refugees, and how can policy help to smooth this transition? and (iv) What role can policy play to encourage resilience among refugees and internally displaced people—and, one day, potentially support their return? Drawing from a diverse set of experiences and country case studies, the invited authors—who range from academics to policy practitioners—present and discuss current evidence and draw from their expertise to offer insights on these general themes in the economic policy response to forced migration. Among others, some of the recurring ideas for the design of policy include the need of anticipatory, systematic, and long- term approaches to the ‘management’ of forced displacement; the importance of building evidence, quantifying impacts, and understanding the distributional consequences of forced migration; and finally, the importance of bridging a gap in how the evidence is communicated and understood in the broader community.

Forced migrants are those who leave their home, their region, or their country of birth, as a result of persecution, conflict, violence, human rights violations, and other events that seriously disturb public order ( UNHCR, 2021 ). Since the 1970s, there have been at least 15 conflicts that have forced at least one million people or more to leave their country of birth—and many other countless clashes that have displaced large numbers of people within their own national borders (so-called ‘internally displaced people’—IDPs).

The most recent of these tragic conflicts is, of course, rarely far from our screens or from our minds. On 24 February 2022 (this year), Russia invaded Ukraine. This invasion—which followed the 2014 annexation of Crimea, and the subsequent occupation of the Ukrainian oblasts of Donetsk and Luhansk—clearly poses new and profound challenges for global cooperation under the international system. It is already clear that one of the most consequential policy issues concerns the treatment of Ukrainian refugees. Over the opening weeks of the Russian invasion, approximately 130,000 Ukrainians fled their country every day: a total of about four million refugees over the course of the first month alone ( UNHCR, 2022 a ). This situation added to the difficulties already faced by large number of IDPs and other displaced people in Ukraine since 2014. Indeed, by 2016 there were already close to two million IDPs in addition to over thirty thousand people seeking asylum 1 ( UNHCR Statistics, 2022 ). The plight of these people demands compassionate and thoughtful responses from governments around the world—both at the national and local levels, and particularly in Europe.

As early as 1951, the parties to the Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees agreed a single definition in international law for the concept of a refugee, 2 and committed to a set of core obligations concerning the treatment of refugees—including, in particular, that refugees have a basic entitlement to protection and support. 3 By mid-2021, there were close to 25 million refugees globally, as recorded by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees ( UNHCR, 2022 b ). As Figure 1 shows, the seven decades since 1951 witnessed a substantial increase in the total number of refugees worldwide. Moreover, the nature of the refugee experience has changed substantially, too; this is reflective, in particular, of changes in the nature of conflict, changes in the methods for refugee protection, and important shifts in the global political structure. For instance, the 2015 Syrian and European refugee ‘crises’ were the driving force behind the 2018 Global Compact on Refugees ( Betts, 2018 ), but at the same time also had a profound and divisive impact on public opinion and voting behaviour in many high-income destination countries ( Dustmann et al. , 2019 ; Dinas et al. , 2020 ; Steinmayr, 2021 ). However, it is countries in the Global South—in particular, those bordering major conflicts—that host the majority of refugees. Displacement has become an urban issue and refugee camps are becoming less common ( Vos and Dempster, 2021 ; Crawford, 2021 ). There is an increasing number of protracted displacements; 4 in turn, this keeps millions of refugees in legal limbo for decades. Finally, as shown in Figure 1 , the number of people displaced within their own countries—50.9 million by mid-2021—is much larger than the number of those displaced internationally, and these numbers continue to increase. 5

Number of refugees under UNCHR Mandate (1950–2021). Note : End year stock population totals. The number of refugees include displaced Venezuelans but do not include Palestine refugees under the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) Mandate. As of mid-2021, the number of Palestinian refugees was estimated at 5.7 million. IDPs are those reported in UNHCR Statistics under the UNHCR population of concern ( UNHCR, 2022 b ).

Source: UNHCR Statistics (2022) .

In this context, policy-makers face a set of related questions. First, what are the general mechanisms by which these refugees should be managed, and what frameworks should be used for supporting them? Second, how can policy help these refugees to integrate into host economies— both at the macro and the micro level—and what are the likely consequences of this integration? Third, how are host communities likely to respond to the influx of refugees, and how can policy help to smooth this transition? Fourth, what role can policy play to encourage resilience among refugees and internally displaced people— and, one day, potentially support their return ?

These are the core questions that are tackled by this issue of the Oxford Review of Economic Policy . Specifically, the issue draws together a set of thinkers with particular expertise on forced migration. We invited the authors in May 2020 and most of the papers were received in final form just prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. In this sense, the journal issue speaks to general themes in the economic policy response to forced migration; indeed, together, the papers draw on experiences from a very diverse set of countries. These include Syria, which currently has the largest population of refugees abroad (6.7 million), and Colombia—a country with a long history of conflict that, with 8.3 million, has the largest number of internally displaced people ( UNHCR, 2022 b ). 6 The articles also draw on the experiences of important host destinations, including Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey—the three main destinations of Syrian refugees, which, as of mid-2021, were together hosting over five million Syrian refugees. Adding the perspective of high-income countries, the issue draws on experiences from Denmark, Sweden, and the United States. The experience in these countries is different in at least three distinctive ways: first, refugee populations in these countries are small relative to the host, both in population terms and in fiscal terms. Second, and as a result, the policy focus has been about integration, dispersion, and assimilation and less on ‘emergency’ management and hosting. The third is that in the case of high-income countries we typically have much richer cross-sectional and time-series data. Therefore, in this case not only are the host-country policy considerations different, but the capacity to inform these through research and evidence is greater. Finally, the issue also draws attention to challenges brought by the return of refugees and the impacts on different aspects of social cohesion, by looking at the Great Lakes refugee crisis and the return of Burundians refugees from Tanzania.

The journal issue is organized in four separate parts—each relating to one of the questions that we posed earlier. Part I discusses mechanisms for managing refugees—‘mechanisms’ both in the general sense of the international institutions and processes that manage the response to refugee crises, and in the specific sense of using insights of modern market design techniques to match refugees effectively with local services. Parts II and III consider integration of refugees into host communities. Part II focuses on refugees and the macroeconomy, with Part III taking the microeconomic impacts through local labour markets and host communities. Part IV then discusses the longer-term path for refugees and internally displaced people: it considers issues of recovery, resilience, and return. The issue concludes with a postscript: a summary discussion of the likely policy implications for supporting refugees from the ongoing crisis in Ukraine.

Part I of the issue considers the particular systems that are used to respond to refugee crises. Some important questions here are, for example, what mechanisms should be used to deliver aid and public services to those that most need it? What can be done by the international community to help and assist host countries receiving refugees? What sort of global financing mechanisms should be in place in order to support the different responses to refugee crises? The first paper in the issue—by Grant Gordon and Ravi Gurumurthy (2022) — provides a framework to think about these questions and it poses a vision of how the humanitarian sector should look for the next 10–20 years. The paper takes stock of the evolution in the responses to forced displacement, identifies notable innovations, and proposes a way forward with an innovation agenda focused on delivering cash transfers and digital aid. It also highlights the importance of ‘compacts’—at the country level and with the support of the international community—that expand entitlements to work, and access to education and public services. An important aspect of this vision and of the future of innovation in the humanitarian sector, as noted by the authors, is that it should be grounded in pre-positioned—anticipatory—financing and policy. In this, the authors draw parallels with the ideas of Daniel Clarke and Stefan Dercon on the importance of a long-term approach to the management of crises. The authors also highlight important ethical issues that need to be considered as innovations in the sector take place.

Justin Hadad and Alexander Teytelboym (2022) then focus more specifically on mechanisms for improving the management of refugee settlement; they do so through the lens of market design. Hadad and Teytelboym start with a fundamental concern: the current refugee resettlement system is inefficient, in the sense that there are too few resettlement places and, when refugees are resettled, they often go to locations where they might not thrive. From this starting point, the paper then highlights several ways in which the market design paradigm can help: better matching between locations and refugees (therefore improving the prospects of success in outcomes for the refugee and the host), and creating incentives to increase the participation of countries in resettlement schemes. Importantly, market design can mitigate some of the worst inefficiencies and unfairness in the current system—improving on the status quo by incorporating refugees’ preferences, communities’ priorities, and economic outcomes. There is substantial scope for market design methods to improve practices at local resettlement agencies and at the international level. However, ultimately it is only political will that can increase resettlement.

Michael Clemens (2022) begins Part II of the issue, with a critical review of the literature on the consequences of refugee arrivals on the national economy. Clemens acknowledges immediately in his paper that economic gain is not the purpose of refugee and asylum policy. Nonetheless, it is crucially important—and, indeed, timely—to quantify the likely magnitude of such economic impacts, particularly given the tone of so much of the political discourse concerning the economic costs and benefits of accepting refugees and asylum-seekers. The paper does exactly that: it measures the consequences to the US economy of the decision to reduce refugee arrivals from 2017 to 2020. The estimates are substantial, and negative: the paper suggests that, on a conservative estimate, a net loss to government revenue of almost US$7,000 per year per ‘missing refugee’, and an overall cost to the economy of about US$31,000 per year per ‘missing refugee’. As Clemens explains, these figures ‘are large in one sense, small in another’; in particular, the costs are minimal relative to the overall size of the US economy.

Trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) together form one very important angle from which refugees might impact a host economy. This is the theme of the paper by Dany Bahar, Christopher Parsons and Pierre-Louis Vézina (2022) who document a ‘diversity dividend’ and a ‘dynamism dividend’ that may allow refugees to be particularly well placed to develop new opportunities for trade and cross-border investment. Among many others, an example is the increased trade between Vietnam and US states hosting Vietnamese refugees, and the development of products such as the Sriracha chilli sauce, a well-known and globally recognized staple condiment. 7 Importantly, another aspect of these cross-border interactions is the role played by refugee diasporas in helping processes of post-conflict reconstruction. As pointed out by the authors, diasporas maintain strong networks with their countries of origin and are well placed to lead and encourage the funding of needed resources to help the development of their country of origin. The authors illustrate with examples of developmental actors and projects that aim at finding ways to channel these efforts to foster peace and development (e.g. The DIASPEACE project). The authors then outline a set of potential policies to encourage refugees in their support for reconstruction and economic development in their origin countries. These include establishing regulations and policies to differentiate between refugees and migrants, providing labour market access to refugees, reducing the costs of remittances, finding mechanisms to leverage the role of diasporas, and—when appropriate—facilitating and incentivizing post-conflict return.

In the first paper in this section, Alexander Betts and Olivier Sterck (2022) note that in low- and middle-income countries there is significant variation in policy responses towards refugees; they ask, ‘why do some states give refugees the right to work, while others do not?’ Betts and Sterck pose competing theories based on interest-based, norms-based, and identity-based accounts; the authors outline potential mechanisms through multi-level bargaining at the global, national, and local levels to explain what might determine compliance with refugee norms. To test these potential explanations, the authors use a qualitative comparative case study together with a rich quantitative dataset, finding that norms-based and multi-level bargaining explanations do indeed explain compliance with refugee norms. In particular, the authors find that the de jure right to work is associated with payoffs at the ‘national’ level (i.e. being a signatory of the 1951 Convention) whereas de facto rights are associated with payoffs at the ‘local’ level (i.e. the degree of decentralization). An important implication of this paper—as highlighted by the authors—is the importance of creating incentives both at the national and local levels in order to promote compliance of refugee norms.

Nordic countries have a wealth of high quality data that allows researchers to look at important aspects of refugee integration and the impacts in hosting communities—and two papers in this issue draw on insights from these data. First, Jacob Nielsen Arendt, Christian Dustmann and Hyejin Ku (2022) review 40 years of evidence on the impacts of different immigration and integration policies on the short- and long-term outcomes of refugees in Denmark. They focus on the Danish evidence to date of five of the most common types of post-arrival policies in high-income countries: dispersal accommodation, employment support, integration and language programmes, welfare benefits, and conditions for permanent residency. A particularly important lesson drawn from the evidence is the need to assess and recognize the potential trade-offs and unintended consequences of changes in policies. For example, while the objective of dispersal policies is to distribute the burden of hosting refugees across all hosting communities, the initial place of settlement can have both immediate and long-term impacts on the labour market performance of refugees. Equally, while employment support policies are desirable, they could crowd out enrolment in language and integration programmes which are important for long-term integration outcomes. Most compelling were their findings regarding welfare. While reductions in benefits do seem to have an initial positive response in employment, there are other consequences of these reductions in disposable income: these include higher criminal activity of refugees and their children.

Sandra Rozo and Maria Jose Urbina (2022) take advantage of the dispersal policy in Sweden to look at the impact of hosting refugees on natives’ attitudes in hosting communities. The authors find that increased shares of refugee inflows translate into lower support for immigration in the hosting communities. These attitudes are further magnified by concurrent changes in economic conditions of the host. Further, a demographic characterization indicates that those holding more negative attitudes are more likely to be young males, with less wealth, and who work in blue-collar occupations. An important implication of this study is that policies aimed at promoting social cohesion towards refugees can usefully be informed by a better understanding of who is most likely to oppose refugees. This paper nicely adds to and complements the recent literature on the impacts of refugee inflows on public opinion and voting behaviour.

While the above two papers focus on high-income countries, many host destinations are low- and middle-income countries, where informality is an important feature of the labour market. Norman Loayza, Gabriel Ulyssea, and Tomoko Utsumi (2022) use a structural spatial model that the authors had previously developed to formally test and analyse the impacts of the mass inflow of Syrian refugees in Turkey. An important finding is that low-skill workers bear the burden of the costs, as the level of informality increases and wages decline for these workers. However, an interesting implication of this model is that since tax revenues and profits per worker also increase, the losses for low-skill workers can potentially be reversed through tax redistribution and could even lead to a net gain in income per capita in most affected regions.

The first paper in this section discusses and reviews over 20 years of research on the dynamics and consequences of forced internal displacement. The analysis is focused on Colombia—the country with the largest number of IDPs globally. As noted by Ana María Ibáñez, Andrés Moya, and Andrea Velázquez (2022), Colombian IDPs are lawfully recognized as victims of the conflict in what is perhaps one of the largest peace-building reparation programmes. The authors identify different mechanisms through which forced displacement can make IDPs vulnerable and trap them into (persistent and chronic) poverty. These include the loss of physical assets, the erosion of human capital, the loss and disruption of social networks, and psychological and behavioural impacts (loss of psychological assets and capacities ). The authors further discuss the evidence on the impact of different policies to assist and support IDPs (IDP registration, anti-poverty programmes, bespoke programmes for IDP, and Reparations and Land Restitution) and identify lessons for other contexts and countries affected by forced displacement.

The paper by Sarah Stillman, Sandra Rozo, Abdulrazzak Tamim, Bailey Palmer, Emma Smith, and Edward Miguel ( Stillman et al. , 2022 , in this issue) focuses on the socio-economic outcomes of Syrian refugees in Jordan. The paper discusses the first round of results of an important ongoing academic effort to track the outcomes of Syrian refugees. The Syrian Refugee Life Study (S-RLS), first launched in 2020, is a representative longitudinal study (2,500 households) of the socio-demographic and other characteristics of the Syrian population in Jordan. The results of the first wave of data are sobering. Syrians—perhaps not surprisingly—are more vulnerable in terms of poverty and other economic outcomes (especially those living outside camps) compared to the Jordanian population, and the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic has likely magnified the growing gap between refugees and non-refugees.

During the lockdown, Syrian refugees had an average reduction in per adult income of 80 per cent and, after the lockdown, the number of households with positive labour income declined by 12.4 per cent. The prospects of return for the Syrian population are not very optimistic: the large majority of refugees are not hopeful that the war will be resolved any time soon and over half of them are not planning to return in the near future. Similar to what the previous paper highlighted, a common theme for refugees is the state of their mental health and higher likelihood of depression.

Complementing the S-LRS above, the next paper by Caroline Krafft, Bilal Malaeb, and Saja Alzoubi (2022) addresses the question: ‘How do policy approaches affect refugee economic outcomes?’ Focusing on education, work permits, cash assistance, welfare, food aid, and the consequences of encampment in Jordan and Lebanon, the authors discuss and assess the relatively scarce evidence on the impacts of the different policies on the refugee population (and some of the externalities on the hosting populations). While the two countries are not necessarily directly comparable, the authors highlight important commonalities and differences in terms of policy effectiveness. They also raise two important points. First, the importance of recognizing the protracted nature of the Syrian conflict. This will likely require a policy effort geared towards refugee integration and a shift to long-term development goals. A second important point is the need for better data collection—including longitudinal data—and the need for good quality impact evaluations to best inform policy-makers and other stakeholders. The previous study (i.e. the S-LRS) has taken important steps in this regard.