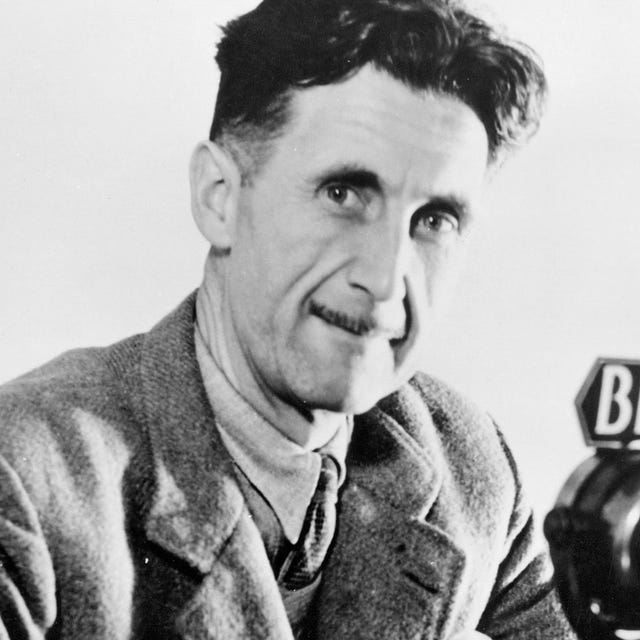

George Orwell

George Orwell was an English novelist, essayist and critic most famous for his novels 'Animal Farm' (1945) and 'Nineteen Eighty-Four' (1949).

(1903-1950)

Who Was George Orwell?

George Orwell was a novelist, essayist and critic best known for his novels Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four . He was a man of strong opinions who addressed some of the major political movements of his times, including imperialism, fascism and communism.

Orwell was born Eric Arthur Blair in Motihari, India, on June 25, 1903. The son of a British civil servant, Orwell spent his first days in India, where his father was stationed. His mother brought him and his older sister, Marjorie, to England about a year after his birth and settled in Henley-on-Thames. His father stayed behind in India and rarely visited. (His younger sister, Avril, was born in 1908. Orwell didn't really know his father until he retired from the service in 1912. And even after that, the pair never formed a strong bond. He found his father to be dull and conservative.

According to one biography, Orwell's first word was "beastly." He was a sick child, often battling bronchitis and the flu.

Orwell took up writing at an early age, reportedly composing his first poem around age four. He later wrote, "I had the lonely child's habit of making up stories and holding conversations with imaginary persons, and I think from the very start my literary ambitions were mixed up with the feeling of being isolated and undervalued." One of his first literary successes came at the age of 11 when he had a poem published in the local newspaper.

Like many other boys in England, Orwell was sent to boarding school. In 1911, he went to St. Cyprian's in the coastal town of Eastbourne, where he got his first taste of England's class system.

What he lacked in personality, he made up for in smarts. Orwell won scholarships to Wellington College and Eton College to continue his studies.

After completing his schooling at Eton, Orwell found himself at a dead end. His family did not have the money to pay for a university education. Instead, he joined the India Imperial Police Force in 1922. After five years in Burma, Orwell resigned his post and returned to England. He was intent on making it as a writer.

Early Writing Career

After leaving the India Imperial Force, Orwell struggled to get his writing career off the ground and took all sorts of jobs to make ends meet, including being a dishwasher.

'Down and Out in Paris and London' (1933)

Orwell’s first major work explored his time eking out a living in these two cities. The book provided a brutal look at the lives of the working poor and of those living a transient existence. Not wishing to embarrass his family, the author published the book under the pseudonym George Orwell.

'Burmese Days' (1934)

Orwell next explored his overseas experiences in Burmese Days , which offered a dark look at British colonialism in Burma, then part of the country's Indian empire. Orwell's interest in political matters grew rapidly after this novel was published.

War Injury and Tuberculosis

In December 1936, Orwell traveled to Spain, where he joined one of the groups fighting against General Francisco Franco in the Spanish Civil War. Orwell was badly injured during his time with a militia, getting shot in the throat and arm. For several weeks, he was unable to speak. Orwell and his wife, Eileen, were indicted on treason charges in Spain. Fortunately, the charges were brought after the couple had left the country.

Other health problems plagued the talented writer not long after his return to England. For years, Orwell had periods of sickness, and he was officially diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1938. He spent several months at the Preston Hall Sanatorium trying to recover, but he would continue to battle with tuberculosis for the rest of his life. At the time he was initially diagnosed, there was no effective treatment for the disease.

Literary Critic and BBC Producer

To support himself, Orwell took on various writing assignments. He wrote numerous essays and reviews over the years, developing a reputation for producing well-crafted literary criticism.

In 1941, Orwell landed a job with the BBC as a producer. He developed news commentary and shows for audiences in the eastern part of the British Empire. Orwell drew such literary greats as T.S. Eliot and E.M. Forster to appear on his programs.

With World War II raging on, Orwell found himself acting as a propagandist to advance the country's national interest. He loathed this part of his job, describing the company's atmosphere in his diary as "something halfway between a girls’ school and a lunatic asylum, and all we are doing at present is useless, or slightly worse than useless.”

Orwell resigned in 1943, saying “I was wasting my own time and the public money on doing work that produces no result. I believe that in the present political situation the broadcasting of British propaganda to India is an almost hopeless task.” Around this time, Orwell became the literary editor for a socialist newspaper.

Famous Books

Sometimes called the conscience of a generation, Orwell is best known for two novels: Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four . Both books, published toward the end of Orwell’s life, have been turned into films and enjoyed tremendous popularity over the years.

‘Animal Farm’ (1945)

Animal Farm was an anti-Soviet satire in a pastoral setting featuring two pigs as its main protagonists. These pigs were said to represent Joseph Stalin and Leon Trotsky . The novel brought Orwell great acclaim and financial rewards.

‘Nineteen Eighty-Four’ (1949)

Orwell’s masterwork, Nineteen Eighty-Four (or 1984 in later editions), was published in the late stages of his battle with tuberculosis and soon before his death. This bleak vision of the world divided into three oppressive nations stirred up controversy among reviewers, who found this fictional future too despairing. In the novel, Orwell gave readers a glimpse into what would happen if the government controlled every detail of a person's life, down to their own private thoughts.

‘Politics and the English Language’

Published in April 1946 in the British literary magazine Horizon , this essay is considered one of Orwell’s most important works on style. Orwell believed that "ugly and inaccurate" English enabled oppressive ideology and that vague or meaningless language was meant to hide the truth. He argued that language should not naturally evolve over time but should be “an instrument which we shape for our own purposes.” To write well is to be able to think clearly and engage in political discourse, he wrote, as he rallied against cliches, dying metaphors and pretentious or meaningless language.

‘Shooting an Elephant’

This essay, published in the literary magazine New Writing in 1936, discusses Orwell’s time as a police officer in Burma (now known as Myanmar), which was still a British colony at the time. Orwell hated his job and thought imperialism was “an evil thing;” as a representative of imperialism, he was disliked by locals. One day, although he didn’t think it necessary, he killed a working elephant in front of a crowd of locals just “to avoid looking a fool.” The essay was later the title piece in a collection of Orwell’s essays, published in 1950, which included ‘My Country Right or Left,’ ‘How the Poor Die’ and ‘Such, Such were the Joys.’

Wives and Children

Orwell married Eileen O'Shaughnessy in June 1936, and Eileen supported and assisted Orwell in his career. The couple remained together until her death in 1945. According to several reports, they had an open marriage, and Orwell had a number of dalliances. In 1944 the couple adopted a son, whom they named Richard Horatio Blair, after one of Orwell's ancestors. Their son was largely raised by Orwell's sister Avril after Eileen's death.

Near the end of his life, Orwell proposed to editor Sonia Brownell. He married her in October 1949, only a short time before his death. Brownell inherited Orwell's estate and made a career out of managing his legacy.

Orwell died of tuberculosis in a London hospital on January 21, 1950. Although he was just 46 years old at the time of his death, his ideas and opinions have lived on through his work.

Despite Orwell’s disdain for the BBC during his life, a statue of the writer was commissioned by artist Martin Jennings and installed outside the BBC in London. An inscription reads, "If liberty means anything at all, it means the right to tell people what they do not want to hear." The eight-foot bronze statue, paid for by the George Orwell Memorial Fund, was unveiled in November 2017.

"Would he have approved of it? It's an interesting question. I think he would have been reserved, given that he was very self-effacing,” Orwell’s son Richard Blair told The Daily Telegraph . "In the end I think he would have been forced to accept it by his friends. He would have to recognise that he was a man of the moment.”

QUICK FACTS

- Name: George Orwell

- Birth Year: 1903

- Birth date: June 25, 1903

- Birth City: Motihari

- Birth Country: India

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: George Orwell was an English novelist, essayist and critic most famous for his novels 'Animal Farm' (1945) and 'Nineteen Eighty-Four' (1949).

- Fiction and Poetry

- Journalism and Nonfiction

- Astrological Sign: Cancer

- Interesting Facts

- According to one biography, Orwell's first word as a child was "beastly."

- Orwell fought in the Spanish Civil War and was badly injured. He and his wife were later indicted of treason in Spain.

- Orwell was once a BBC producer and ended up loathing his job as he felt he was being used as a propaganda machine.

- Death Year: 1950

- Death date: January 21, 1950

- Death City: London

- Death Country: United Kingdom

We strive for accuracy and fairness.If you see something that doesn't look right, contact us !

CITATION INFORMATION

- Article Title: George Orwell Biography

- Author: Biography.com Editors

- Website Name: The Biography.com website

- Url: https://www.biography.com/authors-writers/george-orwell

- Access Date:

- Publisher: A&E; Television Networks

- Last Updated: May 3, 2021

- Original Published Date: April 2, 2014

- In our age there is no such thing as 'keeping out of politics.' All issues are political issues, and politics itself is a mass of lies, evasions, folly, hatred and schizophrenia.

- Happiness can exist only in acceptance.

- Power is not a means, it is an end. One does not establish a dictatorship in order to safeguard a revolution; one makes the revolution in order to establish the dictatorship.

- Each generation imagines itself to be more intelligent than the one that went before it, and wiser than the one that comes after it.

Watch Next .css-smpm16:after{background-color:#323232;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Famous British People

Mick Jagger

Agatha Christie

Alexander McQueen

The Real Royal Scheme Depicted in ‘Mary & George’

William Shakespeare

Anya Taylor-Joy

Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales

Kensington Palace Shares an Update on Kate

Prince William

Where in the World Is Kate Middleton?

George Orwell (1903-1950)

Biography: george orwell.

Commonly ranked as one of the most influential English writers of the 20th century, and as one of the most important chroniclers of English culture of his generation, Orwell wrote literary criticism, poetry, fiction, and polemical journalism. He is best known for the dystopian novel Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) and the allegorical novella Animal Farm (1945). His book Homage to Catalonia (1938), an account of his experiences in the Spanish Civil War, is widely acclaimed, as are his numerous essays on politics, literature, language, and culture. In 2008, The Times ranked him second on a list of the 50 greatest British writers since 1945.

Orwell’s work continues to influence popular and political culture, and the term Orwellian — descriptive of totalitarian or authoritarian social practices — has entered the language together with several of his neologisms, including “cold war,” “Big Brother,” “thought police,” “Room 101,” “doublethink,” and “thought crime.”

George Orwell died on January 21, 1950, in London, England.

From Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_Orwell

- British Literature: Victorians and Moderns. Authored by : James Sexton. Located at : https://opentextbc.ca/englishliterature . Project : BCcampus Open Textbook Project. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of George Orwell. Authored by : Branch of the National Union of Journalists (BNUJ). Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:George_Orwell_press_photo.jpg . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

George Orwell: The Renowned British Novelist and Essayist

- by history tools

- November 19, 2023

Early Life and Upbringing

George Orwell was born Eric Arthur Blair on June 25, 1903 in Motihari, Bengal, British India to a middle-class English family. His father, Richard W. Blair, worked for the Opium Department of the Indian Civil Service. His mother, Ida Mabel Blair, moved the family back to England when Orwell was still a toddler.

Orwell had an unhappy childhood as he did not get along with his authoritarian father. At the age of 8, he was sent to a boarding school called St Cyprian‘s where students were treated harshly. Orwell described his time there as "days of horror" which fueled his lifelong distrust of authoritative institutions. However, he shone academically and earned scholarships to continue his education.

Eton and Burma: Developing a Social Conscience

At the elite Eton College, Orwell trained to join the Indian Imperial Police against his family‘s wishes. Aldous Huxley was one of his teachers at Eton and influenced Orwell‘s later literary style. After graduating Eton, Orwell served in the Indian Imperial Police force in Burma from 1922 to 1927.

Witnessing the effects of British imperialism shaped Orwell‘s political conscience and made him skeptical of authority. "I had already made up my mind that imperialism was an evil thing," Orwell later wrote. His experiences from this period inspired his novel Burmese Days.

Embracing Poverty to Become a Writer

After resigning from his post in Burma in 1927, Orwell returned to England. He chose to immerse himself in the life of the working class by becoming a vagrant. He roamed the slums of East London and went hop picking in Kent to experience poverty first-hand. This period inspired his famous memoir Down and Out in Paris and London.

In 1933, Orwell took the bold step of quitting stable work to pursue his passion for writing full-time. He published his novel Burmese Days in 1934, followed by A Clergyman‘s Daughter in 1935. Of his early novels, he said “I was consciously writing propaganda, but I knew it was a sort of revenge." Orwell started using his pen name at this time to prevent embarrassing his family.

Fighting Fascism in the Spanish Civil War

In 1936, Orwell travelled to Spain to join the Republican militia in the Spanish Civil War aiming "to write truthful propaganda for the Reds and counter Fascist lies." But he became disillusioned by the revolution‘s suppression by Soviet forces. He was forced to flee for his life after being shot in the neck.

Orwell described his experiences in his memoir Homage to Catalonia. "There was much in it I did not understand, in some ways I did not even like it, but I recognized it immediately as a state of affairs worth fighting for,” he wrote about revolutionary Barcelona.

The Success of Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four

During World War II, Orwell worked as a propagandist for the BBC. He started working on Animal Farm in 1943, which satirized the Soviet Union under Stalin‘s rule using talking animals on a farm. It was published in 1945 and brought Orwell widespread acclaim.

Orwell wrote his most famous novel Nineteen Eighty-Four between 1946-1948 as his health declined from tuberculosis. It centered around a dystopian future where the totalitarian government controlled citizens‘ thoughts and heavily censored information. Orwell popularized terms like Big Brother, Thought Police, Newspeak, doublethink, and Room 101 in this novel.

His Enduring Legacy as a Writer and Public Intellectual

Orwell is regarded as one of the most important English writers and thinkers of the 20th century. His unique prose style influenced generations of writers. Orwell broke rules and eliminated extravagance in language, favoring simple declarative sentences. As he wrote in his essay Politics and the English Language, “Never use a long word where a short one will do."

Orwell was one of the first writers to criticize both fascism and totalitarian communism. His books discussed evergreen themes about abuse of power, objective truth, dangers of totalitarianism, and the importance of plain language. He left behind an enduring legacy of speaking truth to power and defending democratic socialism and freedom of thought. The ideas and warnings in Orwell‘s novels remain hugely relevant today, over 70 years after his death at just 46.

Related posts:

- Franz Kafka – The Enigmatic Writer Who Transformed 20th Century Literature

- David Icke: The Controversial Visionary Challenging Our Reality

- Neil Gaiman: Master of Imaginative Fantasy and Horror

- Simon Sinek: The Visionary Thinker Helping Leaders Inspire Action

- John Steinbeck

- Henry David Thoreau: The Original Eco-Philosopher

- Jules Verne: An Imaginative Genius Who Changed Literature

- Virginia Woolf: Groundbreaking Modernist Writer

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Agriculture

- Armed forces and intelligence services

- Art and architecture

- Business and finance

- Education and scholarship

- Individuals

- Law and crime

- Manufacture and trade

- Media and performing arts

- Medicine and health

- Religion and belief

- Royalty, rulers, and aristocracy

- Science and technology

- Social welfare and reform

- Sports, games, and pastimes

- Travel and exploration

- Writing and publishing

- Christianity

- Download chapter (pdf)

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Blair, eric arthur [ pseud. george orwell].

- Bernard Crick

- https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/31915

- Published in print: 23 September 2004

- Published online: 23 September 2004

- This version: 01 September 2017

- Previous version

Eric Arthur Blair [ George Orwell ] ( 1903–1950 )

by Felix H. Man , c. 1947

Blair, Eric Arthur [ pseud. George Orwell] ( 1903–1950 ), political writer and essayist , was born in Motihari , Bengal, India, on 25 June 1903, the only son of Richard Walmesley Blair (1857–1938) , a sub-deputy opium agent in the government of Bengal, and his wife, Ida Mabel Limouzin (1875–1943) . Richard Blair's great-grandfather Charles Blair (1743–1820) , a Scot, had been a rich man, a plantation and slave owner in Jamaica who had married into the English aristocracy; the money had run out by Richard Blair's time, who all his career held poor posts, and was on the move constantly. He married Ida Limouzin , who was eighteen years his junior, late in his career. Her mother was English and her father French; she was born in Penge but had spent most of her life in Moulmein , Burma, where her father was a teak dealer and boat builder. Ida Blair took three-year-old Eric and his older sister, Marjorie , back to England just before the birth of her third and last child, Avril . Eric attended a small Anglican convent school in Henley-on-Thames until he gained a part scholarship to St Cyprian's, a fashionable preparatory school in Eastbourne where Cyril Connolly was among his contemporaries. His fees were topped up by his mother's unmarried brother, who like his sister, and totally unlike Richard Blair , seems to have had intellectual interests and ambitions for his nephew.

In The Road to Wigan Pier Orwell described his family with sardonic precision as 'lower-upper middle class', that is the 'upper-middle class without money' ( Complete Works , 5.113–14 ). Late in his life he wrote a long account of his prep school days, 'Such, such were the joys' , that could not be published in his lifetime for fear of libel. Some have taken this to be a literal account of the horrors of an oppressive and socially discriminatory regime, but it is more likely a polemic against private education based on fact and with a reimagined Eric Blair as the observer, hero, or rather anti-hero. However, whether or not he was caned in front of the school for bed-wetting, the school was bad enough.

Education and early life

Young Eric crammed for and eventually won a scholarship to Eton College, but once there he rested on his oars, neglecting the set tasks; however, he read widely for himself in the canon of English literature and books by rationalists, freethinkers, and reformers like Samuel Butler , George Bernard Shaw , and H. G. Wells . As a scholarship boy at Eton he was in the College—an intellectual élite thrust into the heart of a social élite. He found a few kindred spirits, including Steven Runciman (later the historian of Byzantium) and his prep school friend Cyril Connolly (the critic and writer). In Connolly's Enemies of Promise there are good descriptions of Orwell both at prep school and at Eton. Orwell's contemporaries agree that, without being openly rebellious, he cultivated a mocking, sardonic attitude towards authority. The classical scholar Andrew Gow , who as a young man had taught Orwell , in the mid-1970s remembered him only with irritation and annoyance for having wasted his chance to get to university. It was that kind of attitude that Orwell reacted against.

Following in his father's footsteps, probably more cynically than purposively, Eric was sent to a crammer's to prepare for the Indian Civil Service exams. He scraped just enough marks to be able to join the Burma police in 1921. Burma was then governed as a province of India and did not rate high in the pecking order of ‘the Service’. Eric Blair may well have been the only Etonian ever to pass through the police training school at Mandalay to become an assistant superintendent. His fellow recruits were all older than he (though none taller or wearing size eleven boots) and almost all had gone through the First World War. Blair showed a loathing both for the war and for military values, but also some signs of guilt or regret at having missed it. He grew to like the Burmese and to dislike the effect of colonial rule on his fellow British. Like Flory in his first novel, Burmese Days , he 'learned to live inwardly, in books and secret thoughts that could not be uttered'. He was not popular in the police and had poor postings: 'In Moulmein in Lower Burma, I was hated by large numbers of people—the only time in my life that I have been important enough for this to happen to me' ( Complete Works , 10.501 ). When he wrote about Burma, both in Burmese Days and in two of his finest essays, 'Shooting an elephant' and 'A hanging' , his contempt for imperial rule and the arrogant pretentiousness of too many of his fellows came bursting out.

Setting out

To the dismay of his parents Blair resigned his safe, respectable, and pensionable job while on leave in England from July 1927 and not only resolved to be a writer but took to making journeys among tramps. He lived as a tramp sometimes for a day or two, sometimes for weeks at a time. He said that he wanted to see if the English poor were treated in their own country as the Burmese were treated in theirs. On the whole he thought they were. In spring 1928 he went to Paris to write. As he wrote for an American reference book in 1942, he

lived for about a year and a half in Paris, writing novels and short stories which no one would publish. After my money came to an end I had several years of fairly severe poverty during which I was, among other things, a dishwasher, a private tutor and a teacher in cheap private schools. Complete Works , 12.147

But in an introduction to the Ukrainian edition of Animal Farm he revealed more:

I sometimes lived for months on end among the poor and half-criminal elements … who take to the streets, begging and stealing. At that time I associated with them through lack of money, but later their way of life interested me very much for its own sake. ibid., 19.86–7

Years later Sir Victor Pritchett described him as a man 'who went native in his own country' ( Crick , 276 ). In this period he called himself 'a Tory anarchist'. At first he did not know what he wanted to write about, and he destroyed two early novels. The poet Ruth Pitter remembers reading early manuscripts: 'How we cruel girls laughed. … He wrote like a cow with a musket' ( ibid., 179 ).

Orwell stuck to it, however, and taught himself to write in his famous plain style. His first book published, Down and out in Paris and London (1933), was an account of his tramping days in England, particularly in the hop fields of Kent, and of the poverty he endured while living in Paris trying to write novels. The sales of the book were modest, but it received good notices. He used a pseudonym, George Orwell , partly to avoid embarrassing his parents, partly as a hedge against failure, and partly because he disliked the name Eric , which reminded him of a prig in a Victorian boys' story. His first novel, Burmese Days , was published in New York in 1934. Victor Gollancz in London had refused it for fear of libel actions: the novel was obviously written directly from experience. Based partly on teaching in cheap private schools such as The Hawthorns in Hayes where he had a position from 1932 to 1933, and partly on his parents' neighbours in Southwold, he wrote a contrived literary pastiche, The Clergyman's Daughter (1935). His schoolteaching had ended when in December 1933 he had a bad attack of pneumonia. In October 1934 he left Southwold and moved to Hampstead, London, where he became a half-time assistant in a secondhand bookshop.

Since 1930 Orwell had been reviewing books and writing sketches and poems for The Adelphi , owned and edited by Sir Richard Rees , a disciple of John Middleton Murry . Orwell moved to Hampstead to see more of Rees and also the young writers who called at the Adelphi office for a cup of tea, to talk, and to solicit books to review. He became friendly with Jack Common and Rayner Heppenstall , and met Cyril Connolly again after Connolly had reviewed Burmese Days . But his world, unlike Connolly's , was not that of fashionable Hampstead drawing-rooms but of Hampstead bohemia: those bitter and often jealous intellectuals, living in bed-sits, making a pint in a pub last a whole evening, fearing rent day, and knowing that the post brought only rejection slips. All this he portrayed in Keep the Aspidistra Flying (1936). At this time he himself, like his novel's hero Gordon Comstock, came near to making a cult of failure and to believing that all literary success is ‘selling out’.

In January 1936 the left-wing publisher Victor Gollancz , showing great faith in Orwell as a writer, gave him an advance of £500 (then nearly two years' income for Orwell ) to write a book about poverty and unemployment. He spent two months in the north of England, living with working people in Wigan, Barnsley, and Sheffield from 31 January to 30 March. On his return he moved to a cheap cottage in Wallington, Hertfordshire. On 9 June, after a short courtship, he married Eileen Maud O'Shaughnessy (1905–1945) , who had read English at Oxford, and after running a secretarial agency, was taking a postgraduate diploma in psychology at University College, London. They had met in Hampstead, and hoped to live on his writing, her typing, and running a small village shop.

In Wallington Orwell settled down to write essays including 'Shooting an elephant' , sent to John Lehmann for New Writing , which established him as minor literary talent. He also wrote The Road to Wigan Pier (1937). Gollancz liked the clear and unromantic description of working-class life and coalmining in the first part of the book, but was dismayed by the second part where Orwell announced both his adherence to socialism and his dislike of socialist intellectuals and their admiration for Soviet power. Only with difficulty did Gollancz persuade the selectors of the Left Book Club to publish the book under that banner, and only then with an introduction by himself repudiating his author. 'A writer cannot be a loyal member of a political party,' said Orwell ( Complete Works , 11.167 ). Yet he was soon to join a political party.

Spain and after

When he finished his book in December, Orwell went to Spain to fight for the republic. 'Someone has to kill fascists,' he is alleged to have said. Impatient to be there, he made his own way to Barcelona and joined the POUM militia ('Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista') on the Aragon front. The POUM was an independent Marxist movement, hated by the Stalinists and in dispute with the Trotskyites. Because he was on a quiet section of the front he tried to transfer to the communist-dominated International Brigades around Madrid, but he became involved in the May troubles in Barcelona. This attempt by the communists to purge the POUM and the Catalan anarchists made him bitterly anti-communist. Upon returning to the front, he was badly wounded in the neck, and was then hunted by the communists while still convalescent. With the help of his wife, Eileen , who had come to Barcelona to work for the Independent Labour Party (ILP) , he escaped from Spain at the end of June 1937.

Orwell went back to Wallington and wrote Homage to Catalonia , a supreme description of trench life (lice and boredom), but also a trenchant and detailed exposure of how the communists risked the whole republican cause in their lust for power and in their zeal to suppress all other socialists. Gollancz refused to publish it, so Frederick Warburg , who was known as the Trotskyite publisher simply because he took left-wing books that were critical of Stalin , brought out the book in April 1938. Orwell now saw himself as an anti-communist revolutionary socialist; he joined the ILP , and he attended and spoke at their summer schools. Homage to Catalonia was much abused and much defended. Its literary merits were hardly noticed, and it sold few copies. Some now think of it as Orwell's finest achievement, and nearly all critics see it as his great stylistic breakthrough: he became the serious writer with the terse, easy, vivid colloquial style.

In March 1938 Orwell had collapsed with a tubercular lesion in one lung and was removed to a sanatorium. Thanks to help from an unknown admirer, the Blairs spent winter 1938–9 in the warmth of Morocco, where he finished Coming up for Air (1939), a novel reflecting a foreboding of war and an ironic nostalgia for a lost past. Like all his novels prior to the Second World War, except A Clergyman's Daughter , it was not written for the modernist intellectuals: he wanted to reach the audience whom he called the common man, the audience for whom H. G. Wells still wrote and who still read Dickens —those whose only university was the free public library. In fact Orwell's novels did not reach such a wide audience, each selling only between 3000 and 4000 copies.

In his ILP days Orwell claimed that 'the coming war' would be merely a capitalist struggle for the control of colonial markets. As late as July 1939 he wrote 'Not counting Niggers' (a title of savage, Swiftian irony), claiming that British and French leaders did not ask the vast majority of their colonies about whether they wanted to fight. But, when the Second World War broke out, he immediately declared that even Chamberlain's England was preferable to Hitler's Germany. In his essay 'My country, right or left' he stated a left-wing case for patriotism that he developed in The Lion and the Unicorn .

Orwell was rejected for the army several times because of his tuberculosis (a friend said that he tried harder to get into the army than many did to get out), so he moved back to London and joined the part-time Home Guard ; for a while he thought that it could become a Catalan-style revolutionary militia. In February 1941 he published The Lion and the Unicorn , partly a profound meditation on the English national character and partly a left-wing assertion of patriotism, but also continuing the argument from his Catalan days that the war could be won only if a revolution replaced the old ruling class. But those hopes faded. In August 1941 he became, after a period of painful underemployment, a producer with the Far Eastern section of the BBC , tolerating the job's unaccustomed and uncongenial restraints until November 1943.

In 1939 Orwell had published a volume of essays, Inside the Whale . His powers as an essayist were recognized and went from strength to strength. A remarkable series of essays followed when he at last could begin to choose for whom he wrote: notably 'The prevention of literature' , 'Politics and the English language' , 'Politics versus literature' , and 'Writers and Leviathan' . During the war he wrote regularly for Cyril Connolly's Horizon and for Partisan Review in New York. But some of his best writing came after November 1943, when he was made literary editor of The Tribune , a left-wing weekly directed by Aneurin Bevan . His weekly column, 'As I please' , ranged through a vast number of topics, some serious and some comic, some political and some literary. He set a model for the lively mixed column soon to be emulated by many other writers not only in Britain. As George Orwell he became a known character, hard-hitting and good-humoured, a quirky socialist but with a love of traditional liberties and pastimes. The private man was, however, very reserved and a compulsive overworker. Both his and Eileen's health became very run down, partly through wartime conditions and partly through physical neglect; yet he persuaded her to adopt a child, Richard .

Brief days of fame

Early in 1944 Orwell finished writing Animal Farm but at least four leading publishers ( Gollancz , T. S. Eliot for Faber , Jonathan Cape , and Collins ) turned it down as inopportune while Russia was an ally. It was not published until shortly after the end of the war in Europe. Several critics called it the greatest satire in the English language since Swift's Gulliver's Travels , and it brought Orwell instant fame and a huge new and international readership. Harcourt Brace took it after many New York firms had rejected it, and it was a Book of the Month Club selection: it sold 250,000 copies in one year. It was translated into every major language, including some in which it could only be read in smuggled or in samizdat versions. It has survived the late twentieth-century collapse of Soviet power not only because of its plain style— Orwell believed passionately and politically that no meaningful idea was too difficult to be explained in simple terms to ordinary people—but because the satire can touch all power-hungry regimes, left or right, and even some rulers who can be hard to pin down in either category.

Before it appeared Orwell went to France for The Observer to report on the liberation, and to Germany to try to witness the opening of the concentration camps, but Eileen died and he came hurrying home. He told people that she died during anaesthetic for a minor operation. In fact she had cancer. She may well not have told him, but it seems somewhat obtuse of him not to have seen that something was badly wrong. Outwardly he bore her death with the stoicism of Orwell , but Eric Blair was deeply hurt and shaken—though by now the public mask had taken over almost entirely. Only a few very old friends called him Eric ; new friends, as diverse as Julian Symons , Arthur Koestler , Anthony Powell , and Malcolm Muggeridge , called him George . He stuck to his adopted son, Richard , first on his own, then with the help of a housekeeper. He began writing regularly again for The Tribune and The Observer and also for the Manchester Evening News . He moved to a farmhouse on the northern tip of the remote island of Jura, where, even in Eileen's lifetime, he had resolved to escape, to avoid the distractions of London and to begin work on a new and ambitious book.

Barnhill was indeed remote, 8 miles up a track from the nearest phone, which in turn was 25 miles from a shop in a small village where steamers came twice a week. The journey from London took two days. At first Orwell revelled in the difficulties and seclusion, but soon his younger sister, Avril , followed him, froze out the young housekeeper, and became herself both housekeeper and ‘gatekeeper’ against unwanted visitors. Brother and sister did not always see eye to eye on who was unwanted or welcome. He worked hard, perhaps too hard, in a small room with a smoky stove, and chain-smoked as usual. In a notebook he wrote that in all his writing life

there has literally been not one day in which I did not feel that I was idling, that I was behind with the current job, and that my total output was miserably small. Even at the period when I was working ten hours a day on a book, or turning out four or five articles a week, I have never been able to get away from this neurotic feeling, that I was wasting time. Complete Works , 20.204

Orwell collapsed with tuberculosis with only a first draft of his long-planned new novel finished, which as always 'to me is only ever halfway through'. In a Scottish hospital the new drug streptomycin, obtained from America with the help of David Astor and Aneurin Bevan , was tested on him. Gruesome side-effects resulted, not then controllable, and the treatment was unhappily abandoned. Rested, at least, he returned to Jura, but drove himself hard again and, when his agent and his publisher failed to find a typist who would go to Jura, he sat up in bed and typed the second version of his novel himself. He collapsed again when he had finished.

The resulting novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four , published in 1949, immediately elicited diverse interpretations. Critics have seen it as a pessimistic and deterministic prophecy; an allegory on the impossibility of staying human without belief in God; an anti-Catholic diatribe, in which the inquisitor, O'Brien, and the inner party are really the church; a world-hating act of nihilistic misanthropy; a deathbed renunciation of any kind of socialism; or a humanistic and libertarian socialist (almost anarchist) satire against totalitarian tendencies in both his own and other contemporary societies. Isaac Rosenfeld saw it as 'mysticism of cruelty, utter pessimism' ( Rosenfeld , 514 ); and Anthony Burgess as 'a comic novel', or one that 'allows' ( Burgess , 20 ) humour.

Certainly it is the most complex piece of writing Orwell attempted. Jenni Calder in a lecture called it 'a well-crafted novel', perhaps over-crafted; and part of the craft was dramatizing dilemmas and fears of humanity, and not offering easy solutions. But biographically it is clear at least, contrary to much facile opinion, what it is not: it is not a work of unnatural, almost psychotic intensity dashed off by a dying man with a death wish for civilization and regressing to memories of childhood traumas. In fact it was long planned and coolly premeditated, and was neither a conscious nor an unconscious repudiation of Orwell's democratic socialism. Czesaw Miłosz in 1953 reported that in Poland some of his old Communist Party colleagues had read smuggled copies as a manual of power, but that the freer minds had seen it as 'a Swiftian satire': 'The fact that there are writers in the West who understand the functioning of the unusually constructed machine of which they are themselves a part, astounds them and argues against “the stupidity” of the West' ( Miłosz , 42 ). It is arguable whether Nineteen Eighty-Four was Orwell's greatest achievement; most critics, and Orwell himself, see Animal Farm as his unquestioned literary masterpiece. 'What I have most wanted to do is to make political writing into an art,' he said in his essay of 1946 'Why I write' . He was both a great polemical and a speculative writer: 'Liberty is telling people what they do not want to hear.' He challenges his readers' assumptions in direct terms of homely common sense, forces them to think, but mostly leaves them to reach their own conclusions. He may argue fiercely but never as if authoritatively, which perhaps accounts for his continued popularity.

If seen as Swiftian satire then a lot falls into place: grotesque exaggeration, humour but also deadly seriousness. Orwell raged against the division of the world into spheres of influence by the great powers at the wartime meetings at Yalta and Potsdam; power-hunger and totalitarian impulses wherever they occurred; intellectuals for turning into bureaucrats and betraying the common people; the debasement of language by governments and politicians; the rewriting of history for ideological purposes; James Burnham's thesis in his Managerial Revolution that the managers and technocrats are going to take over the world; the existence of a permanent cold war because of the impossibility of a deliberate atomic war; and, not least, the debasement of popular culture by the mass press. He pictured the ministry of truth in Nineteen Eighty-Four as producing for the proles not propaganda but 'rubbishy newspapers containing almost nothing but sport, crime and astrology, sensational five-cent novelettes, films oozing with sex, and sentimental songs composed entirely by mechanical means'. Plainly he was getting at the British press of his day. It is doubtful if he had even heard of the Frankfurt school of Marxism which held that social control was maintained in capitalist society by the degradation of literacy rather than by terrorism, but in homely terms Orwell makes the same point.

Last days and afterlife

From January to September 1949 Orwell lay in a sanatorium in Gloucestershire. Then he was transferred to University College Hospital in London to be under one of the best chest specialists in England, who had also once treated D. H. Lawrence . The doctors, as was then customary, gave him some hope. In fact they knew that there was none. But he was not told, nor was Sonia Mary Brownell (1918–1980) , a former editorial assistant on Connolly's Horizon to whom he had proposed marriage without success in 1945. When he asked her again, she accepted, genuinely hoping to help him and nurse him back to health and, at the worst, perhaps not unwilling to accept the status of widow of an already world-famous author.

Orwell married Brownell on 13 October 1949 and began work on a new novel, as if he thought he would survive; but he also made his will and left precise instructions (fortunately ignored by his widow) about which of his writings to reprint and which to suppress. He read the first reviews of Nineteen Eighty-Four and dictated notes for a press release to correct some American reviewers who saw in it an attack on all forms of socialism, not just on all forms of totalitarianism. He reminded them that he was a democratic socialist, that the book was 'a parody', and that he meant only that something like the iron regime could, not would, occur, if we did not all both guard and exercise our liberties. He died on 21 January 1950 of a tubercular haemorrhage and was buried on 26 January at All Saints, Sutton Courtenay. Unexpectedly (for he was an avowed non-believer) he had asked to be buried not cremated, and according to the rites of the Church of England . The language and liturgies of the church were part of the Englishness he felt so deeply.

It is much debated whether Orwell's real genius is as an essayist and descriptive writer rather than as a novelist. In 'Why I write' (1946) he said that

while my starting point is always a feeling of partisanship, a sense of injustice … [yet] so long as I remain alive and well so I shall continue to feel strongly about prose style, to love the surface of the earth and to take pleasure in solid objects and useless scraps of information.

He said he was not able and did not want 'completely to abandon the world-view that I acquired in childhood'. Above all else, he said, he wanted 'to make political writing into an art' ( Complete Works , 18.319 ).

Rarely has a more private and simple man become more famous. Orwell's very name has entered the English language. The word ‘Orwellian’ conveys the fear of a future for humanity governed by rival totalitarian regimes who rule through suffering, deprivation, deceit, and fear, and who debase language and people equally. But ‘ Orwell -like’ conveys something quite different: a lover of nature, proto-environmentalist, advocate of plain language and plain speaking, humorist, eccentric, polemicist, and someone who could meditate, almost mystically, almost pietistically, on the pleasure and wonder of ordinary things—as in the small, great essay 'Some thoughts on the common toad' .

Even before Orwell's death political battle broke out and has long continued to annex his reputation. Some American editors and writers had genuinely misunderstood Animal Farm as a satirical polemic against all forms of socialism, rather than a betrayal of revolutionary egalitarian ideals by Stalin and the Communist Party . By the time of the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four the then powerful Time and Life magazines chose to ignore the author's standpoint and to present him again as both anti-socialist and anti-communist. If they recognized a distinction in the presence of the post-war Labour government in Britain, they either thought that inevitably it ‘would go that way’ or that Orwell , had he lived, would have abandoned democratic socialism.

The espousal of Orwell by the American right and free-market liberals made some British socialists immediately brand him as a betrayer of socialism and ‘a cold war warrior’. He himself had first coined the phrase ‘cold war’ in postulating an atomic stalemate. Certainly he was much more alert and aroused than many fellow socialists to the real threat of the communist subversion in western Europe; but he cannot be considered a betrayer of socialism if his reviews and writings are followed right up to the time of his death. Many ex-communists were angry with him for being, as was said, ‘prematurely correct’ and for giving ‘ammunition to the enemy’. One example of such ammunition was that he gave permission without charge for translations of Animal Farm into Ukrainian to be made for smuggling into Ukraine by the early Central Intelligence Agency (which helped to fund a cartoon based on the novel released in 1955). He wrote an interesting introduction to explain his own background and his politics. Most of the copies were, by another irony, destroyed by the American military in Austria who were strictly observing the three power agreement. Back then, in the eyes of the left, all Ukrainians were of course fascists, and to complicate matters further some Ukrainians who did get to read his introduction could not (like the editors of Time ) see any difference between communism and socialism.

The ‘old’ new left (that is, those who left the Communist Party after Hungary in 1956 but were still Marxists) engaged in a deliberate campaign of both political and literary abuse of Orwell . They still smarted at the impatience he had shown at their earlier illusions and naïvety. To this the ‘new’ new left of the New Left Review (the student generation trying to reform Marxist theory) added two more charges: that he was not a serious theorist and that he was patriotic, comfortable in his Englishness. They seemed with their secular liberationist ideology to be in favour of anybody else's nationalism except their own. Edward Thompson's and Raymond Williams's intense dislike of Orwell was especially curious because all three had a vivid sense of an English radical tradition in perpetual conflict with the conservative account of tradition, the common people versus the establishment.

At least these attacks took Orwell seriously as a ‘political writer’ which, he said in his essay 'Why I write' , had been his main intent since 1936. Many literary figures found it hard to come to terms with his politics and most critical studies in the 1950s and 1960s concentrated on his character and on his books. A Uniform Edition of his books had been published by Secker and Warburg in 1960, but not until 1968 in the four volumes of The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of 1968, edited by Sonia Orwell (as Sonia Blair , his widow, called herself) and Ian Angus , could the full variety and power of his writing be appreciated. A less Orwellian version of Orwell could then emerge: the Orwell -like speculative, humorous, sardonic, discursive essayist. Even then the last of the four volumes left out several telling political essays and long reviews that Sonia Orwell regarded as 'repetitive' or 'not his best'. These could strengthen the complacent surmise of English writers that he was moving away from political writing back to more conventional novels and belles lettres , and the wishful belief of American neo-liberals that he was ‘giving all that up’, ‘that’ being democratic socialism. Sonia Blair's friend Mary McCarthy took it for granted that he was moving to the right before his death, as did two major studies of cultural politics in the cold war. But biographical evidence is to the contrary.

The year 1984 saw a carnival of misunderstanding in the media, as if Nineteen Eighty-Four had ever been a serious projection or prophecy rather than a Swiftian satire, still less a prediction of a date. But what was remarkable was that by then all Orwell's books and most of his essays had been in print since 1960 and that at conferences large non-academic audiences appeared. Orwell's stature as writer and thinker cannot rival that of George Bernard Shaw or H. G. Wells , but neither of their reputations as popular writers has survived as well, nor have even their major writings remained continuously in print. Perhaps it is this popularity of Orwell in a literal sense that so irritates or embarrasses some critics and writers, either jealous or convinced that he cannot therefore be a serious intellectual writer.

In 1996 a fresh storm broke out when some files in the Public Record Office were routinely opened and The Guardian and the Daily Telegraph ‘revealed’ that Orwell had ‘spied on’ fellow writers for the Foreign Office . (In fact this information had appeared in Bernard Crick's biography of 1980 drawn from Orwell's own papers in University College, London.) Far from spying, he provided a list that he sent to a friend, Celia Kirwan ( Arthur Koestler's sister-in-law), who was working in the IRD (information research department) , a special unit of the Foreign Office set up by Ernest Bevin . It was a list of writers who, he thought, would be unsuitable for anti-communist propaganda in 1946 when the Soviet Union was subsidizing and infiltrating every kind of cultural conference and event they could. There was a cultural cold war. The Sunday Telegraph mocked that an 'icon of the Left has been exposed', and The Guardian said that no liberal should ever do such a thing. But Orwell was not a liberal in their sense: his temperament was republican. When the republic was threatened, it had to be defended.

Struggles to appropriate or to denigrate Orwell will continue, as will popular interest in his essays and the documentary books. Four major biographies, with two more appearing in the centenary year 2003, have been produced, and fully reliable texts have been reissued by Secker , in the twenty-volume Complete Works of George Orwell (1986–98), and are now followed in the Penguin editions. These are freed from the bowdlerization of publishing in the 1930s, errors, and omissions, thanks to the monumental labours of one of England's leading Shakespearian bibliographers, Peter Davison . After Orwell's death many of the fashionable intellectuals of the time who knew him wrote tributes or assessments as if his character was more noteworthy and important than the quality or content of his writings. But the continued popularity of his writings has settled that argument. His greatest fame and readership have been posthumous.

- B. Crick, George Orwell : a life , pbk edn (1982)

- P. Stansky and W. Abrahams, eds., The unknown Orwell (1972)

- P. Stansky and W. Abrahams, eds., Orwell : the transformation (1979)

- A. Coppard and B. R. Crick, eds., Orwell remembered (1994)

- M. Shelden, Orwell : the authorised biography (1991)

- The complete works of George Orwell , ed. P. Davison, 20 vols. (1986–98)

- G. Woodcock, The crystal spirit (1967)

- P. Buitenhuis and I. B. Nadel, George Orwell : a reassessment (1988)

- C. Hitchens, Orwell's victory (2002)

- C. Miłosz, The captive mind (1953)

- J. Calder, Chronicles of conscience : a study of George Orwell and Arthur Koestler (1968)

- A. Burgess, 1985 (1978)

- I. Rosenfeld, ‘Decency and death’, Partisan Review (May 1950)

- G. Orwell, Nineteen eighty-four (1984) [with a critical introduction and annotations by B. Crick]

- NRA , corresp. and literary papers

- UCL , corresp. and diary

- UCL , corresp., literary MSS, and notebooks

- UCL , corresp. with Secker and Warburg, publishers

- photographs, 1945, Hult. Arch.

- F. H. Man, photograph, 1947, NPG [see illus.]

- photographs, UCL , Orwell archive

Wealth at Death

£9908 14 s . 11 d .—in England: probate, 2 Feb 1951, CGPLA Eng. & Wales

View the article for this person in the Dictionary of National Biography archive edition .

- Brownell [married names Blair, Pitt-Rivers], Sonia Mary [known as Sonia Orwell] (1918–1980), literary editor, writer, and friend of artists and intellectuals

- Orwell, George, (25 June 1903–21 Jan. 1950), (pseudonym of Eric Blair); author in Who Was Who

External resources

- Bibliography of British and Irish history

- British Library, Discovering Literature

- National Portrait Gallery

- National Archives

- English Heritage Blue Plaque

Printed from Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a single article for personal use (for details see Privacy Policy and Legal Notice).

date: 22 May 2024

- Cookie Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

- [66.249.64.20|185.66.14.133]

- 185.66.14.133

Character limit 500 /500

by George Orwell

1984 quiz 1.

- 1 Winston is afraid of worms dogs slugs rats

- 2 Julia is a member of the Junior Anti-Sex League Inner Party Spies Brotherhood

- 3 "Facecrime" is any act which appears on the surface to be illegal, but is not wearing an improper expression on your face defacing a poster of Big Brother spraying graffiti on the outside of a building

- 4 Winston's hostile and glaring colleague in the Records Department is named Ampleforth Syme Tillotson Ogilvy

- 5 The sash around Julia's waist is scarlet green gold white

- 6 Complete the slogan: "Who controls the past, controls the future; . . ." "...who controls the past also controls the present." "...who controls the present, controls the past." "...who controls the present also controls the future." "...who controls the future, controls the present."

- 7 Comrade Ogilvy is a fictitious person created by Winston for a rewritten Times article a fellow worker of Julia's in the Fiction Department a war hero-turned-traitor who evaded capture and disappeared Winston's neighbor in the Records Department

- 8 Both Syme and Parsons ask Winston if he has any spare chocolate Victory cigarettes shaving cream razor blades

- 9 Winston predicts that all of the following will be vaporized except: O'Brien Syme Parsons himself

- 10 All of the following are (presumably) vaporized except: Syme O'Brien Parsons Winston

- 11 At the climax of the Two Minutes Hate, Goldstein's face turns into the face of Big Brother a rat a Eurasian a sheep

- 12 Winston reflects that the only thing "cheap and plentiful" is sugar Victory coffee tea synthetic gin

- 13 Complete the slogan: War is Peace; Freedom is Slavery; Ignorance is Truth Bliss Knowledge Strength

- 14 According to Syme, what is "orthodoxy"? fanaticism strict adherence to the ideas in and language of old English literature unconsciousness a type of religion which was to be outlawed

- 15 According to Winston, where does hope lie? with Emmanuel Goldstein with the Brotherhood with the proles with O'Brien

- 16 The current name of Britain is Province U-571 Ingsoc Airstrip One Oceania

- 17 What is the nickname the proles have for rocket bombs? bangers steamers boomers whoppers

- 18 In his diary, Winston defines freedom as something he once dreamed about the promise of the future a state where telescreens and the Thought Police do not exist the freedom to say that two plus two make four

- 19 Winston identifies the voice that says "We shall meet in the place where there is no darkness" as belonging to whom? Julia O'Brien Winston's mother Big Brother

- 20 What did Winston steal from his younger sister? soup chocolate her favorite toy milk

- 21 Mr. Charrington offers to sell Winston a print of: St. Clement's Dane St. Martin's Shoreditch Old Bailey

- 22 Inside the glass paperweight is a rose seashell sea anemone piece of pink coral

- 23 Why do tears spring to Rutherford's eyes in the Chestnut Street Cafe? The Victory Gin is too strong for him Jones and Aaronson are reminiscing about the past He is overjoyed at the news that Oceania has won a major battle over Eastasia A song, "Under the spreading chestnut tree, I sold you and you sold me," is played over the telescreen

- 24 The caption on the Big Brother posters says: Big Brother knows where you live Big Brother loves you Big Brother is watching you Big Brother will save you

- 25 After a dream of seeing the girl in the Golden Country, Winston awakens with a word on his lips. What is the word? "Milton" "Julia" "Shakespeare" "Mother"

1984 Questions and Answers

The Question and Answer section for 1984 is a great resource to ask questions, find answers, and discuss the novel.

Describe O’Briens apartment and lifestyle. How do they differ from Winston’s?

From the text:

It was only on very rare occasions that one saw inside the dwelling-places of the Inner Party, or even penetrated into the quarter of the town where they lived. The whole atmosphere of the huge block of flats, the richness and...

What was the result of Washington exam

Sorry, I'm not sure what you are asking here.

how is one put into the inner or outer party in the book 1984

The Outer Party is a huge government bureaucracy. They hold positions of trust but are largely responsible for keeping the totalitarian structure of Big Brother functional. The Outer Party numbers around 18 to 19 percent of the population and the...

Study Guide for 1984

1984 study guide contains a biography of George Orwell, literature essays, quiz questions, major themes, characters, and a full summary and analysis.

- 1984 Summary

- Character List

Essays for 1984

1984 essays are academic essays for citation. These papers were written primarily by students and provide critical analysis of 1984 by George Orwell.

- The Reflection of George Orwell

- Totalitarian Collectivism in 1984, or, Big Brother Loves You

- Sex as Rebellion

- Class Ties: The Dealings of Human Nature Depicted through Social Classes in 1984

- 1984: The Ultimate Parody of the Utopian World

Lesson Plan for 1984

- About the Author

- Study Objectives

- Common Core Standards

- Introduction to 1984

- Relationship to Other Books

- Bringing in Technology

- Notes to the Teacher

- Related Links

- 1984 Bibliography

Wikipedia Entries for 1984

- Introduction

- Writing and publication

- About George Orwell

- Partners and Sponsors

- Accessibility

- The Orwell Festival

- Upcoming events

- The Orwell Memorial Lectures

- Books by Orwell

- Essays and other works

- Encountering Orwell

- Orwell Live

- About the prizes

- Reporting Homelessness

- Enter the Prizes

- Previous winners

- Orwell Fellows

- Introduction

- Enter the Prize

- Terms and Conditions

- Volunteering

- About Feedback

- Responding to Feedback

- Start your journey

- Inspiration

- Find Your Form

- Start Writing

- Reading Recommendations

- Previous themes

- Our offer for teachers

- Lesson Plans

- Events and Workshops

- Orwell in the Classroom

- GCSE Practice Papers

- The Orwell Youth Fellows

- Paisley Workshops

The Orwell Foundation

- The Orwell Prizes

- The Orwell Youth Prize

Why I Write

This material remains under copyright in some jurisdictions, including the US, and is reproduced here with the kind permission of the Orwell Estate . The Orwell Foundation is an independent charity – please consider making a donation or becoming a Friend of the Foundation to help us maintain these resources for readers everywhere.

From a very early age, perhaps the age of five or six, I knew that when I grew up I should be a writer. Between the ages of about seventeen and twenty-four I tried to abandon this idea, but I did so with the consciousness that I was outraging my true nature and that sooner or later I should have to settle down and write books.

I was the middle child of three, but there was a gap of five years on either side, and I barely saw my father before I was eight. For this and other reasons I was somewhat lonely, and I soon developed disagreeable mannerisms which made me unpopular throughout my schooldays. I had the lonely child’s habit of making up stories and holding conversations with imaginary persons, and I think from the very start my literary ambitions were mixed up with the feeling of being isolated and undervalued. I knew that I had a facility with words and a power of facing unpleasant facts, and I felt that this created a sort of private world in which I could get my own back for my failure in everyday life. Nevertheless the volume of serious – i.e. seriously intended – writing which I produced all through my childhood and boyhood would not amount to half a dozen pages. I wrote my first poem at the age of four or five, my mother taking it down to dictation. I cannot remember anything about it except that it was about a tiger and the tiger had ‘chair-like teeth’ – a good enough phrase, but I fancy the poem was a plagiarism of Blake’s ‘Tiger, Tiger’. At eleven, when the war or 1914-18 broke out, I wrote a patriotic poem which was printed in the local newspaper, as was another, two years later, on the death of Kitchener. From time to time, when I was a bit older, I wrote bad and usually unfinished ‘nature poems’ in the Georgian style. I also, about twice, attempted a short story which was a ghastly failure. That was the total of the would-be serious work that I actually set down on paper during all those years.

However, throughout this time I did in a sense engage in literary activities. To begin with there was the made-to-order stuff which I produced quickly, easily and without much pleasure to myself. Apart from school work, I wrote vers d’occasion , semi-comic poems which I could turn out at what now seems to me astonishing speed – at fourteen I wrote a whole rhyming play, in imitation of Aristophanes, in about a week – and helped to edit school magazines, both printed and in manuscript. These magazines were the most pitiful burlesque stuff that you could imagine, and I took far less trouble with them than I now would with the cheapest journalism. But side by side with all this, for fifteen years or more, I was carrying out a literary exercise of a quite different kind: this was the making up of a continuous “story” about myself, a sort of diary existing only in the mind. I believe this is a common habit of children and adolescents. As a very small child I used to imagine that I was, say, Robin Hood, and picture myself as the hero of thrilling adventures, but quite soon my “story” ceased to be narcissistic in a crude way and became more and more a mere description of what I was doing and the things I saw. For minutes at a time this kind of thing would be running through my head: ‘He pushed the door open and entered the room. A yellow beam of sunlight, filtering through the muslin curtains, slanted on to the table, where a matchbox, half-open, lay beside the inkpot. With his right hand in his pocket he moved across to the window. Down in the street a tortoiseshell cat was chasing a dead leaf,’ etc., etc. This habit continued until I was about twenty-five, right through my non-literary years. Although I had to search, and did search, for the right words, I seemed to be making this descriptive effort almost against my will, under a kind of compulsion from outside. The ‘story’ must, I suppose, have reflected the styles of the various writers I admired at different ages, but so far as I remember it always had the same meticulous descriptive quality.

When I was about sixteen I suddenly discovered the joy of mere words, i.e. the sounds and associations of words. The lines from Paradise Lost –

So hee with difficulty and labour hard Moved on: with difficulty and labour hee,

which do not now seem to me so very wonderful, sent shivers down my backbone; and the spelling ‘hee’ for ‘he’ was an added pleasure. As for the need to describe things, I knew all about it already. So it is clear what kind of books I wanted to write, in so far as I could be said to want to write books at that time. I wanted to write enormous naturalistic novels with unhappy endings, full of detailed descriptions and arresting similes, and also full of purple passages in which words were used partly for the sake of their sound. And in fact my first completed novel, Burmese Days , which I wrote when I was thirty but projected much earlier, is rather that kind of book.

I give all this background information because I do not think one can assess a writer’s motives without knowing something of his early development. His subject-matter will be determined by the age he lives in – at least this is true in tumultuous, revolutionary ages like our own – but before he ever begins to write he will have acquired an emotional attitude from which he will never completely escape. It is his job, no doubt, to discipline his temperament and avoid getting stuck at some immature stage, or in some perverse mood: but if he escapes from his early influences altogether, he will have killed his impulse to write. Putting aside the need to earn a living, I think there are four great motives for writing, at any rate for writing prose. They exist in different degrees in every writer, and in any one writer the proportions will vary from time to time, according to the atmosphere in which he is living. They are:

(i) Sheer egoism. Desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood, etc., etc. It is humbug to pretend this is not a motive, and a strong one. Writers share this characteristic with scientists, artists, politicians, lawyers, soldiers, successful business men – in short, with the whole top crust of humanity. The great mass of human beings are not acutely selfish. After the age of about thirty they abandon individual ambition – in many cases, indeed, they almost abandon the sense of being individuals at all – and live chiefly for others, or are simply smothered under drudgery. But there is also the minority of gifted, willful people who are determined to live their own lives to the end, and writers belong in this class. Serious writers, I should say, are on the whole more vain and self-centered than journalists, though less interested in money.

(ii) Aesthetic enthusiasm. Perception of beauty in the external world, or, on the other hand, in words and their right arrangement. Pleasure in the impact of one sound on another, in the firmness of good prose or the rhythm of a good story. Desire to share an experience which one feels is valuable and ought not to be missed. The aesthetic motive is very feeble in a lot of writers, but even a pamphleteer or writer of textbooks will have pet words and phrases which appeal to him for non-utilitarian reasons; or he may feel strongly about typography, width of margins, etc. Above the level of a railway guide, no book is quite free from aesthetic considerations.

(iii) Historical impulse. Desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity.

(iv) Political purpose – using the word ‘political’ in the widest possible sense. Desire to push the world in a certain direction, to alter other people’s idea of the kind of society that they should strive after. Once again, no book is genuinely free from political bias. The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.

It can be seen how these various impulses must war against one another, and how they must fluctuate from person to person and from time to time. By nature – taking your ‘nature’ to be the state you have attained when you are first adult – I am a person in whom the first three motives would outweigh the fourth. In a peaceful age I might have written ornate or merely descriptive books, and might have remained almost unaware of my political loyalties. As it is I have been forced into becoming a sort of pamphleteer. First I spent five years in an unsuitable profession (the Indian Imperial Police, in Burma), and then I underwent poverty and the sense of failure. This increased my natural hatred of authority and made me for the first time fully aware of the existence of the working classes, and the job in Burma had given me some understanding of the nature of imperialism: but these experiences were not enough to give me an accurate political orientation. Then came Hitler, the Spanish Civil War, etc. By the end of 1935 I had still failed to reach a firm decision. I remember a little poem that I wrote at that date, expressing my dilemma:

A happy vicar I might have been Two hundred years ago, To preach upon eternal doom And watch my walnuts grow But born, alas, in an evil time, I missed that pleasant haven, For the hair has grown on my upper lip And the clergy are all clean-shaven. And later still the times were good, We were so easy to please, We rocked our troubled thoughts to sleep On the bosoms of the trees. All ignorant we dared to own The joys we now dissemble; The greenfinch on the apple bough Could make my enemies tremble. But girls’ bellies and apricots, Roach in a shaded stream, Horses, ducks in flight at dawn, All these are a dream. It is forbidden to dream again; We maim our joys or hide them; Horses are made of chromium steel And little fat men shall ride them. I am the worm who never turned, The eunuch without a harem; Between the priest and the commissar I walk like Eugene Aram; And the commissar is telling my fortune While the radio plays, But the priest has promised an Austin Seven, For Duggie always pays. I dreamt I dwelt in marble halls, And woke to find it true; I wasn’t born for an age like this; Was Smith? Was Jones? Were you?

The Spanish war and other events in 1936-37 turned the scale and thereafter I knew where I stood. Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it. It seems to me nonsense, in a period like our own, to think that one can avoid writing of such subjects. Everyone writes of them in one guise or another. It is simply a question of which side one takes and what approach one follows. And the more one is conscious of one’s political bias, the more chance one has of acting politically without sacrificing one’s aesthetic and intellectual integrity.

What I have most wanted to do throughout the past ten years is to make political writing into an art. My starting point is always a feeling of partisanship, a sense of injustice. When I sit down to write a book, I do not say to myself, ‘I am going to produce a work of art’. I write it because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention, and my initial concern is to get a hearing. But I could not do the work of writing a book, or even a long magazine article, if it were not also an aesthetic experience. Anyone who cares to examine my work will see that even when it is downright propaganda it contains much that a full-time politician would consider irrelevant. I am not able, and do not want, completely to abandon the world view that I acquired in childhood. So long as I remain alive and well I shall continue to feel strongly about prose style, to love the surface of the earth, and to take a pleasure in solid objects and scraps of useless information. It is no use trying to suppress that side of myself. The job is to reconcile my ingrained likes and dislikes with the essentially public, non-individual activities that this age forces on all of us.

It is not easy. It raises problems of construction and of language, and it raises in a new way the problem of truthfulness. Let me give just one example of the cruder kind of difficulty that arises. My book about the Spanish civil war, Homage to Catalonia , is of course a frankly political book, but in the main it is written with a certain detachment and regard for form. I did try very hard in it to tell the whole truth without violating my literary instincts. But among other things it contains a long chapter, full of newspaper quotations and the like, defending the Trotskyists who were accused of plotting with Franco. Clearly such a chapter, which after a year or two would lose its interest for any ordinary reader, must ruin the book. A critic whom I respect read me a lecture about it. ‘Why did you put in all that stuff?’ he said. ‘You’ve turned what might have been a good book into journalism.’ What he said was true, but I could not have done otherwise. I happened to know, what very few people in England had been allowed to know, that innocent men were being falsely accused. If I had not been angry about that I should never have written the book.

In one form or another this problem comes up again. The problem of language is subtler and would take too long to discuss. I will only say that of late years I have tried to write less picturesquely and more exactly. In any case I find that by the time you have perfected any style of writing, you have always outgrown it. Animal Farm was the first book in which I tried, with full consciousness of what I was doing, to fuse political purpose and artistic purpose into one whole. I have not written a novel for seven years, but I hope to write another fairly soon. It is bound to be a failure, every book is a failure, but I do know with some clarity what kind of book I want to write.

Looking back through the last page or two, I see that I have made it appear as though my motives in writing were wholly public-spirited. I don’t want to leave that as the final impression. All writers are vain, selfish, and lazy, and at the very bottom of their motives there lies a mystery. Writing a book is a horrible, exhausting struggle, like a long bout of some painful illness. One would never undertake such a thing if one were not driven on by some demon whom one can neither resist or understand. For all one knows that demon is simply the same instinct that makes a baby squall for attention. And yet it is also true that one can write nothing readable unless one constantly struggles to efface one’s own personality. Good prose is like a windowpane. I cannot say with certainty which of my motives are the strongest, but I know which of them deserve to be followed. And looking back through my work, I see that it is invariably where I lacked a political purpose that I wrote lifeless books and was betrayed into purple passages, sentences without meaning, decorative adjectives and humbug generally.

Gangrel , No. 4, Summer 1946

- Become a Friend

- Become an International Friend

- Becoming a Patron

We use cookies. By browsing our site you agree to our use of cookies. Accept

Index Index

- Other Authors :

George Orwell

Ask litcharts ai: the answer to your questions.

COMMENTS

How old was he when he died? January 23, 1950, London (46 years old) What is George Orwell's full name? Eric Arthur Blair. When did Orwell write his first book? 1933. Who was Orwell's father and what was his occupation? Richard Walmesley Blair, a minor official in the Indian civil service.

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like did george orwell fit in at school?, is orwell one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century?, what are his best known novels? and more.

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like Sympathized, underdog, Social and more.

George Orwell (born June 25, 1903, Motihari, Bengal, India—died January 21, 1950, London, England) was an English novelist, essayist, and critic famous for his novels Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-four (1949), the latter a profound anti-utopian novel that examines the dangers of totalitarian rule.. Born Eric Arthur Blair, Orwell never entirely abandoned his original name, but his ...

George Orwell was an English novelist, essayist, and critic most famous for his novels Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949). The following biography was written by D.J. Taylor. Taylor is an author, journalist and critic. His biography, Orwell: The Life won the 2003 Whitbread Biography Award. His new biography, Orwell: The New Life was...