Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Startups: a systematic review of literature and future research directions

Revista de Ciências da Administração

The objective of the research is to map the literature based on a Systematic Literature Review on the theme of startups and to highlight some theoretical gaps based on publications of high-reputation scientific journals. The period from 1990 to 2019 was defined for the elaboration of this study. We use the excel spreadsheet, in addition to the HistCite ™, VOSviewer, IRATUMEQ, and R Studio packages. The results show that the typology of the startups evaluated, after reading 68% of the articles, organizations are characterized as a group of new companies, that is, relatively young and inexperienced when compared to the most stable and mature in organizational development. They refer to those that are in the initial stage and are susceptible to the influence of various factors, such as investors, supplier customers, partners, etc., and should think strategically about how to act and, this concerns a group of dynamic startups that work with innovations.

Related Papers

Aidin Salamzadeh

Startup companies are newly born companies which struggle for existence. These entities are mostly formed based on brilliant ideas and grow to succeed. These phenomena are mentioned in the literature of management, organization, and entrepreneurship theories. However, a clear picture of these entities is not available. This paper tries to conceptualize the phenomenon, i.e. “startup”, and recognize the challenges they might face. After reviewing the life cycle and the challenges, the paper concludes with some concluding remarks.

Economics of Grids, Clouds, Systems, and Services

Somayeh Koohborfardhaghighi

World of export

Amirhossein Roshanzamir

The global wave of startups fueled by digital technologies and the internet has caused the emergence of new ventures and business models. These startups are the engines of growth everywhere, including developing economies by addressing local problems, including economic development, employment, human well being, and sustainability through creative solutions and innovative technologies. Yet, launching a startup from scratch is very challenging, while the chance of success is very small. This paper briefly introduces some of the startup characteristics and reviews the Harvard survey on important skills entrepreneurs need to have to succeed.

Sinergie Italian Journal of Management

Alessia Pisoni

Frank de Langen

Frank De Langen

The purpose of the article is to determine which factors are most important for the success of a startup with a radical innovation in the first three years. First a conceptual model is designed in which three main factors determine the success of growth: the uniqueness of the advantages of the innovation, the startup organization characteristics and the person of the entrepreneur. A survey was setup with startup companies which are not older than fifteen years and which are active in a diversity of segments. A correlation analyses was done based on 75 respondents.Growth was operationalised in two ways: the growth in turnover and the growth in employment. We found different factors correlating in a different way with the different growth concepts. Both growth in employment and in turnover are positively related to a thorough business plan and more than 75k Euro seed capital. The uniqueness of the advantages of the innovation, customer pro-activeness, multiple founders and a relevant social network have a positive influence on turnover growth but not on employment growth. For turnover growth t he uniqueness of the advantages of the innovation and more than 75k Euro initial capital had a high significance. There is a positive relation between employment growth and external advice and investor capital but not with the turnover growth. Only a thorough business plan, external advice, 75k Euro initial capital and using investors capital had a positive significant influence on employment growth. Other conclusions are that depending on the used criterion for growth the significant factors differ and that in general the employment growth is a factor 4 smaller than the turnover growth.

IJAERS Journal

Never before in the history of India, a successful initiative was taken by Government of India by announcing a campaign by Indian Prime Minister, Shri Narendra Modi at Vigyan Bhavan Auditorium in New Delhi during his speech on 15 August 2015. Even No-one would have been thought about its huge success at that moment. But now, just look at the magical moves taken by this unbelievable movement in the business world of India. Success is not the result of a single stroke. No doubt various parameters were fixed at different levels to encourage Startup journey. So many convincing factors worked diligently to ensure its success. However, it has covered a long journey of success despite of various hurdles. Not only it has been promoted in India but also it has been cherished globally. Huge population, Hidden talent in educated youth, Readiness of Investors, Technical advancement and different Government schemes like DIGITAL INDIA, STAND-UP INDIA, MAKE IN INDIA AND SWARAJ and many more pushed it enough to flourish around the world. A startup defines us to be our own boss and of course meeting the demand for employment by others that requires a lot of patience and tactics. It is a well-organized and disciplined way of using several factors like basic idea, market strategies, level of competition, and Techno-Pro attitude especially in the present scenario of entrepreneurship before putting huge steps to accomplish the journey. Different and severally important elements play an effective role in entrepreneurial success like availability of Infrastructural facilities, government rules and regulations and funds availability during various phases of growth. History shows the ups and downs of this journey by revealing various examples of its success or failure within a short span of time after mentioning the actual causes responsible for .The paper titled 'STARTUPS-A NEW PARADIGM FOR YOUNG ENTREPRENEURS' depicts the entire story of its coming into existence with the current status.

Open Journal of Business and Management

Marcelo Fukui

This study maps and analyzes the academic literature regarding the main startups’ valuation methods by means of a bibliometric analysis and systematic review. The adoption of both methods requires the use of software such as RStudio, VOSViewer or Rank Words. In bibliometric analysis, the verification of its main laws—Zipf, Bradford and Lotka is also adopted. As a bibliometric analysis result, the most frequent keywords appear to be performance, innovation, entrepreneurship and venture capital. Most of the authors are associated with institutions located in Germany and in the United States. Concerning the systematic review results, the topic of identifying funding sources is urgent, considering the fact that startups are companies with high levels of uncertainty and risk. Another concern refers to the way of obtaining the types of data for inputs in the valuation models. Regarding the valuation methods, the ones of multiples are highlighted. As for future paths for further research, ...

woa.sistemacongressi.com

Gilda Antonelli

Przedsiębiorczość Międzynarodowa

Joanna Szarek

RELATED PAPERS

Diler Diler

Inflação Goiânia

Miguel Angelo Pricinote

Jurnal Kartika Kimia

Jasmansyah Jasmansyah

Anderson Nedel

Chaos in Communications

Ana Pilar González Marcos

International Law Revista Colombiana De Derecho Internacional

Jorge Andres Murgas Jacome

2015 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE)

Kijana Crawford

European Heart Journal

Jaap Deckers

Hooshang Lahooti

New Criminal Law Review

Carlos Speijer Diez

Zilanda Almeida

Psicoperspectivas. Individuo y Sociedad

Marcela Cornejo

Set Outer Inner by Rumah Jahit Azka

Revista Pesquisas e Práticas Psicossociais

Michelle Tusi

Journal of Applied Geophysics

IOSR Journal of Dental and Medical Sciences

Tarig Hakim

Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics

Eric Lebraud

Academic Leadership: The Online Journal

Janet Fleetwood

HAL (Le Centre pour la Communication Scientifique Directe)

Seraphin S A Alava

Journal of the human-environment system

Peter Tikuisis

The EMBO Journal

william terzaghi

Scientific Reports

Andrea Ticinesi

ELECTROPHORESIS

Soundaryan Rajendran

Ethiopian Journal of Biological Sciences

Afework Bekele

Sociedad e Infancias

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, pivot decisions in startups: a systematic literature review.

International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research

ISSN : 1355-2554

Article publication date: 26 February 2021

Issue publication date: 27 May 2021

Entrepreneurs' pivot decisions are poorly understood. The purpose of this paper is to review the existing literature on pivot decisions to identify the different conceptualizations, research streams and main theoretical building blocks and to offer a baseline framework for future studies on this phenomenon.

Design/methodology/approach

A systematic literature review of 86 peer-reviewed papers published between January 2008 and October 2020, focusing on the pivot decision in startups, was performed through bibliometric, descriptive and content analyses.

The literature review identifies four research streams concerning the pivot concept – pivot design, cognitive, negotiation and environmental perspectives. Building on previous studies, this paper provides a refined definition of a pivot that bridges elements from the four research streams identified: a pivot comprises strategic decisions made after a failure (or in the face of potential failure) of the current business model and leads to changes in the firm's course of action, resource reconfiguration and possible modifications of one or more business model elements. This study proposes a framework that elaborates the pivot literature by identifying four stages of the pivot process addressed in the existing literature: recognition, generating options, seizing and testing and reconfiguration.

Originality/value

This study provides a comprehensive review, enabling researchers to establish a baseline for developing future pivot research. Furthermore, it improves the conceptualization of pivots by summarizing prior definitions and proposing a refined definition that places decision-making and judgment at its center. That introduces new contextual and behavioral elements, contributing to a better understanding of how entrepreneurs assess alternative courses of action and envision possible outcomes to redirect a venture after failure.

- Decision-making

- Entrepreneurial judgment

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editor and the anonymous reviewers for their guidance and insightful comments. Funding : The research was funded by grant from 436877/2018-0, National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq-Brazil), 2015/26662-5, São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), and PD- 00068-0045/2019, Isa Cteep-Aneel.

Flechas Chaparro, X.A. and de Vasconcelos Gomes, L.A. (2021), "Pivot decisions in startups: a systematic literature review", International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research , Vol. 27 No. 4, pp. 884-910. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-12-2019-0699

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

We’re listening — tell us what you think, something didn’t work….

Report bugs here

All feedback is valuable

Please share your general feedback

Join us on our journey

Platform update page.

Visit emeraldpublishing.com/platformupdate to discover the latest news and updates

Questions & More Information

Answers to the most commonly asked questions here

A Systems View Across Time and Space

- Open access

- Published: 01 October 2020

Literature review on business prototypes for digital platform

- Shrutika Mishra 1 &

- A. R. Tripathi 1

Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship volume 9 , Article number: 23 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

48k Accesses

26 Citations

Metrics details

In today’s world, many digitally enabled start-ups are budding all over the globe because of the fast enhancement in digital technologies. For the establishment of new business, it is necessary to adopt a proper business model which needs to define the way in which the company will provide values and the ways in which the customers can pay for their services. This paper aims to study the various business models being used in today’s marketplace and to provide a better understanding for these business models by having an insight on the attributes.

Introduction

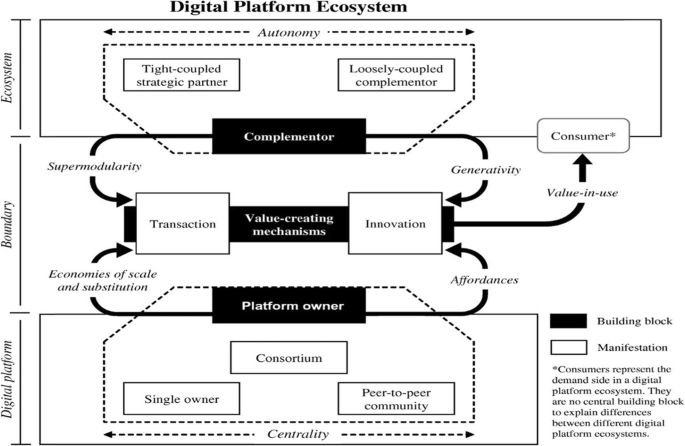

Digital platforms are connected businesses that enable commercial interfaces between at least two different assemblies—with one normally being suppliers and the other consumers (Lestan et al., 2017 , Shrutika, 2018 , Mishra & Tripathi, 2019 , 2020b ). It is useful for digital expertise, technologies and devices in current openings for enterprise leaders and frontrunners to change of mind their business to generate enhanced understandings for clients, workers, and ecosystem associates to lower costs (Porat, 2008 , Hein et al., 2019 ). When businesses act to take benefits of these breaks through digital revolution, they take on two prime events: building a digital platform and building a new operating model (Nambisan et al., 2019 ). The sketchy digital platform ecosystem can be elaborated as below (Hein et al., 2019 , Nambisan et al., 2019 ) (Fig. 1 ).

Digital Platform Ecosystem

In other words, a digital platform is a web cantered platform for offering content (things like Facebook, Twitter, Blogs, Websites, and sometimes SMS). This is in contrast to an analogue platform (like billboards, direct mail, telemarketing, events and word of mouth). A promotion is the messaging that you would use platforms to communicate. This could sponsor a manufactured goods or facility and could interconnect it over both digital and analogue platforms. Digital platforms are a new generation of customer/employee/partner-focused, internal and external platforms that need to measure elastically and compromise a range of entry touchpoint. It consists of (Nambisan et al., 2019 , Mishra, 2019 , Mishra & Tripathi, 2019 , 2020b ):

Upkeep one to billions of customers

Empower worldwide, distributed enormous and lesser establishments

Associate billions of devices and sensors and connected internet of things (IoT) devices

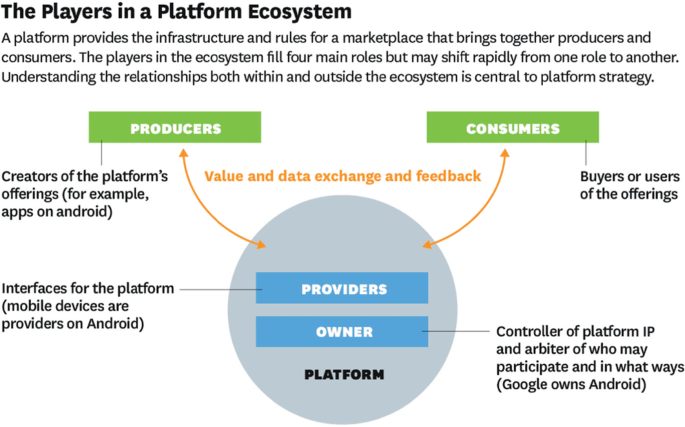

Participate and integrate with the business models and processes of growing number of associates, suppliers and even competitors and participants. The following diagram shows the players in a platform ecosystem and its internal and external functions (Parker et al., 2016 , 2018 ) (Fig. 2 ).

The Players in a Platform Ecosystem

The players connect, integrate, inspire, stimulate with catalytic approach put to work and upkeep society, businesses, governments and engagements in cogent and progressive manner.

They have a boundless number of software products inside, which in turn have millions of features that can be merchandises of sorts, and they hinge on progressively on data that is liquid, directly available and is used to get-up-and-go insights, whereabouts and consequences (Parker et al., 2016 ).

Mutually, these happenings must occur simultaneously and that present a pitfall: a business is incomplete in how far it can go in fluctuating its operational model unless the digital platform flourishes. Impending this consequence erroneously causes many digital platform revolution enterprises to fail. Success with a digital platform does not need to be contingent on the technologies encompassing the platform execution. Success depends on users accepting the platform. To cognize how the escalation of platforms is renovating competition. We need to survey how platforms differ from the conventional “pipeline” businesses that have conquered business for years in the state-of-the-art business technology (Parker et al., 2016 , 2018 ). Pipeline businesses produce value by monitoring a linear series of events—the classic value-chain model. Inputs at one end of the chain (say, resources from brokers) go through a sequence of steps that transmute them into an output that is substance more: the finished product. We can illustrate it through Apple’s handset business. Apple’s handset business is essentially a pipeline but combine it with the App store. The flea market associates with App developers and iPhone owners, and we have got a platform (Parker et al., 2018 ).

There has been a sharp rise in start-ups building software-based platforms (SBP) for industries that once seemed unaffected by digitization (Nieborg, et al. 2018 ). An important feature of this digital platform (DP) is that their reach is much further than the fields of communication and information, and they do so by making the transportation and hospitality industries better (Abdelkafi, 2013 , Ardolino et al., 2018 ).

For example, OYO Rooms is a start-up found in 2013 by Ritesh Agarwal. It provides a service like online booking of budget hotels to customers based on their needs (Alt et al. 2018 ). Since then, it has grown all over India by raising funds from big investors such as Softbank Group, Light Speed Venture Partners (LSVP) and many more (Spieth et al. 2014 , Autio et al., 2018 ).

It raised series round of funding of $24 million from Light speed Venture Partners , Sequoia Capital , Green oaks Capital and DSG Consumer Partners (DSGCP) (Smith et al. 2001 , Barwise et al., 2018 ).

In late 2017, OYO launched OYO Home, an Airbnb -like marketplace for short-term managed rentals ( https://www.techcircle.in , 2019 , Sinha et al., 2015 ). OYO Home has presence in more than 10 leisure destinations of India including Goa, Shimla, Pondicherry, Udaipur, Kerala, (all in India) etc. In April 2018, OYO launched its first international OYO Home in Dubai (de Oliveira et al., 2019 ).

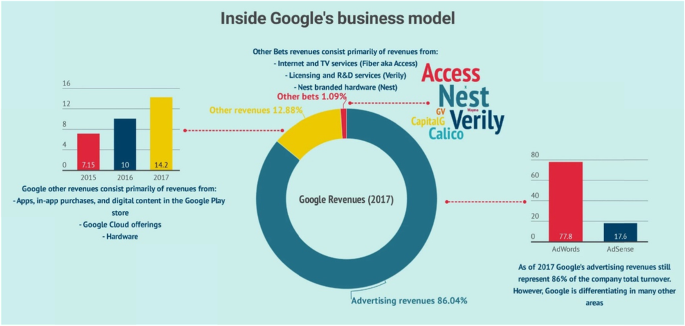

In year 2019, Google generated about $25 billion in revenue. The vast majority of that revenue, well over 95%, originate from advertising via its search engine and its AdSense program, which places ads on billions of websites.

A firm can differentiate from its competitions even if it provides same or similar services in the marketplace if it has a good and unique business model (Chesbrough et al., 2002 , Cawley et al., 2007 , Bucherer et al., 2011 , Speranza et al., 2018 ). For example, Paytm is a company that provides online payment system and digital wallet to its customers but before Paytm came into the market, there were companies which already existed such as Mobikwik and Freecharge, and they were providing customers with digital wallets and even then, Paytm outperformed its competition and took over the marketplace (de Reuver et al., 2018 ). Also, success of a start-up does not completely depend on the efficiency of a business model; for a start-up to succeed, it must have a proper and practical solution to the existing problem (Circenis et al., 2009 , Büyüközkan et al., 2018 ).

A business model is a company’s strategy for making earnings and profits (Agostinho et al., 2016 , Allee, 2000 , Vikas, 2012b ). It classifies the products or facilities the business will sell, the bull’s eye market (Antikainen & Valkokari, 2016 , Ordanini et al., 2004 , Li, 2018 , Weinhardt et al., 2009b , Shrutika, 2018 ). It should be identified and the expenses it anticipates. A new business in enlargement has to have a business model, if only in order to fascinate investment, help it recruit faculty and encourage organization and workforce. Conventional businesses have to re-examine and bring up-to-date their business strategies regularly, or they will be unsuccessful to get ahead developments and challenges in advance. Stakeholders need to analyse and evaluate the business plans of corporations that concentrate on them (Azodolmolky et al., 2013 , Santhanam, 2014 , Täuscher & Chafac, 2016 , Täuscher & Laudien, 2017 , Mishra & Tripathi, 2020b ). Although there is no acquired definition of business model, it can be defined in various ways depending upon the attributes that are being considered while defining it; however, it should be kept in mind that its definition should consider company’s internal and external attributes and should layover the ways in which the company will be providing services and values while converting those values into profit (Burgess et al., 2018 ). “The business model has been referred to as a statement, a description, are presentation, an architecture, a conceptual tool or model, a structural template, a method, a framework, a pattern, and a set” (Büyüközkan et al., 2018 ).

Literature review

With the advent of the new economy, business models (BM) have become an increasingly popular unit of analysis to explain differences in firms’ success (Cearley et al., 2012 , Büyüközkan et al., 2018 ). However, digital business model (DBM) differs from business model on the basis that it can provide a two-way revenue model for both the customers and the sellers, so we need to lay emphasis on both sides (Bocken et al., 2014 ). A good digital business model should make sure that the seller as well as the buyer gets benefited (Evans et al., 2009 , Yin et al., 2018 ).

With the evolution of technology and data, business model, it is not only the area that experienced transformation while other areas which experienced transformation are business strategy, workforce, customer interaction and business operations, and these areas are dependent on each other for their growth and success (Gawer et al., 2007 , 2014 , Werth et al., 2018 ).

According to authors A. Osterwalder and Y. Pigneur (Osterwalder, et al., 2002 , 2004 , 2005 , 2010 , 2011 , Wu et al., 2015 ), in their book “Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers, Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc”, a business model can be described by nine building blocks which further wraps the four main segments of business: customers, offer, infrastructure and financial viability (Timmers et al., 1998 , Clark et al., 2012 , Xu et al., 2018 , Wirtz et al., 2010 ). To understand how the rise of platforms is transforming competition, we need to examine how platforms differ from the conventional “pipeline” businesses that have dominated industry for decades. Pipeline businesses create value by controlling a linear series of activities—the classic value-chain model (Luby et al., 2006 ). Inputs at one end of the chain (say, materials from suppliers) undergo a series of steps that transform them into an output that is worth more: the finished product. Apple’s handset business is essentially a pipeline but combine it with the App Store, the marketplace that connects app developers and iPhone owners, it becomes a digital platform (Table 1 ).

As Apple exhibits, partnerships need not be only a pipeline or a platform; they can be both. While sufficiently pure pipeline productions are still highly modest, when platforms enter the same marketplace, the platforms effectively continuously landslide. That is why pipeline titans such as Walmart, Nike, John Deere, and GE are all cross-country to incorporate platforms into their business models (Watanabe et al., 2018 ).

Furthermore, in a study on role of the business model, Chesbrough and Rosenbloom elated a more detailed definition of business model as (Chesbrough et al., 2002 , Yoo et al., 2010 , 2012 , Sabatier et al., 2012 ):

The functions of a business model are to:

articulate the value proposition, that is, the value created for users by the offering based on the technology;

identify a market segment, that is, the users to whom the technology is useful and for what purpose;

define the structure of the value chain within the firm required to create and distribute the offering;

estimate the cost structure and profit potential of producing the offering, given the value proposition and value chain structure chosen;

describe the position of the firm within the value network linking suppliers and customers, including identification of potential complements’ and competitors;

formulate the competitive strategy by which the innovating firm will gain and hold advantage over rivals.

This definition points out the important blocks of a business model on which it should focus and suggests a proper way of interacting with them so that the business model can function efficiently which leads to a sustainable way of doing business (Azodolmolky et al., 2013 , Balodi et al., 2014 , Coase, 1937 , de Vasconcelos Gomes et al., 2018 ). The priority of these attributes may vary in different businesses according to their needs and the condition of the marketplace, so there is no compulsion on treating them in a same manner in every other business as some attributes may require much more focus than other attributes in a particular business (Grewal et al., 2018 , Hamari et al., 2016 , Baldegger et al., 2016 , Bason, 2018 , Mishra & Tripathi, 2019 , 2020b ).

Various frameworks have been laid down by different authors which further help in development of business models as required by the business, these frameworks describe relationship of important components and also give an insight on how they can be beneficial to our business, and there is no single perfect framework defined for all business types so its choice can vary from business to business (Kurt et al., 2017 , Baporikar, 2015 , Benlian, 2018 ). These frameworks can help to utilise the business model to its maximum potential. Some of these existing frameworks are Business cycle framework, Innovation radar etc. (Li et al., ( 2018 ), Lockamy III et al., ( 2011 , 2012 ), Berman et al., ( 2012 ), Antikainen, et al., ( 2016 )).

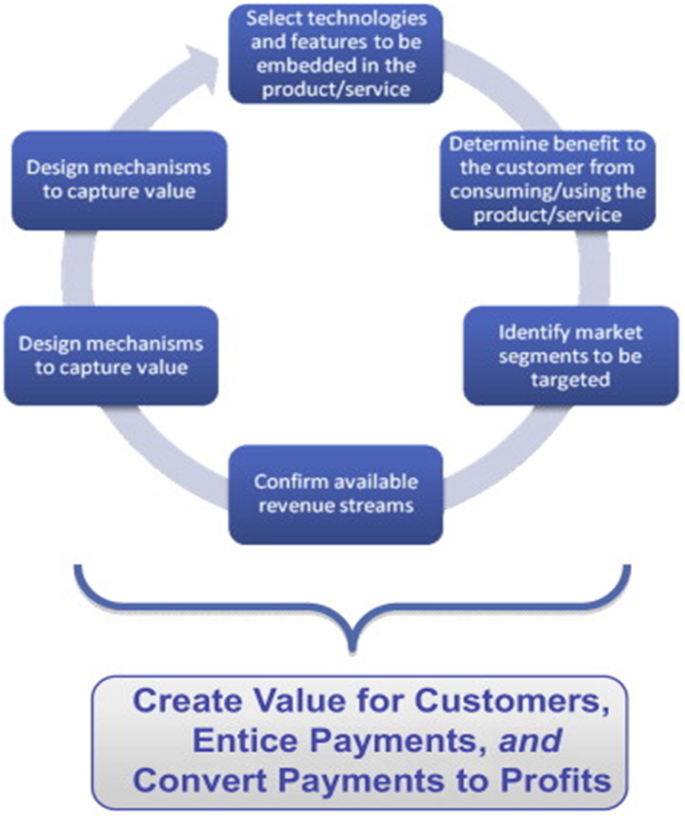

Business cycle framework (BCF)

Author Teece gave this framework in his journal article “Business models, business strategy and innovation” (Teece et al., 2010 ). This framework focuses of important components of a business model in a cyclic manner (Tian et al., 2011 ). It is rather a step-by-step guide to develop a business model, starting from selection and identification of value preposition then to determine the customers who will get benefit from and segmenting the market accordingly which has to be targeted (Tidd et al., 2018 ). Further analysing the revenue streams which are available and develop the procedures to use these available resources in a cost-conscious way, hence developing a mechanism to capture the value from the entire process (Weinhardt et al., 2009a , Watanabe et al., 2016 , 2018 ). However, this framework does not include channeling of products to the markets efficiently, and neither it included focusing on making partners for the expansion of business in the marketplace (Ordanini et al, 2004 , Spiess-Knafl et al., 2015 , Zott et al., 2011 , Skog et al., 2018 , Shrutika, 2018 ) (Fig. 3 ).

Business cycle framework. Source (Tian et al., 2011 )

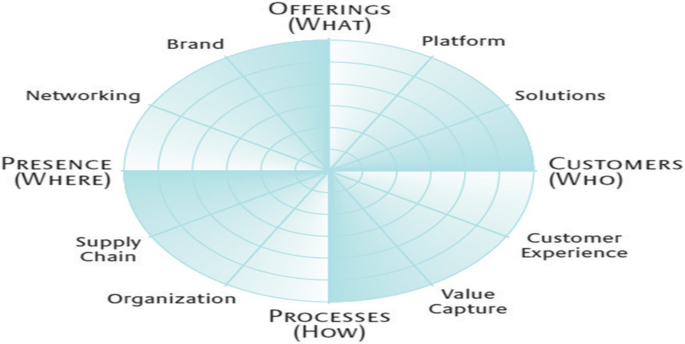

The innovation radar (IR)

This innovation radar framework was given by Sawhney, Walcott and Arroniz in “The 12 Different Ways for Companies to Innovate”. This framework lists various components which are important in innovation of sustainable business model, and this framework provides a efficient solution to four basic questions like “WHAT services/products are being offered to the customers?”, “WHO will get the benefit of these sevices/products?”, “HOW the company will be making profits by providing these services?” and “WHERE these services/products needs to be delivered?” whose answers will give some insights in developing the business models. This framework consists of 12 dimensions (O’Reilly, 2011 , Ghazawneh et al., 2013 , Standing and Mattsson, 2018 ) which are described briefly in the table below (Fig. 4 ).

Innovation radar. Source (Solis et al., 2014 , Speranza, 2018 )

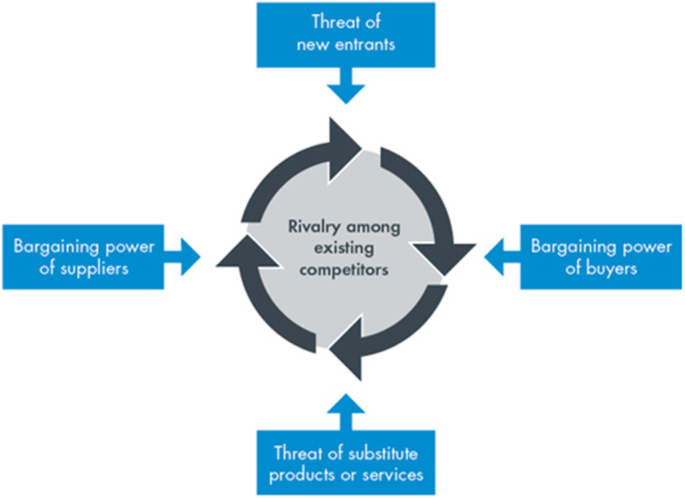

In spite of studying various components and frameworks of a business model and also after reading and observing the marketplace carefully, there are some risks for which a business should always be prepared to face it anytime as they are not in one’s control, and these market risks as stated by Porter in journal “The Five Competitive Forces that Shape Strategy” are caused by five competitive forces (Porter, 2008 , Reynolds, 2011 , Sutherland et al., 2018 , Pisano et al., 2015 , Goerzig et al., 2018 ). These competitive forces can be a threat to the existing business but also, it can raise the quality of value preposition offered to customers at better prices. Also, customers will have more options to choose from; hence, we can say that it can be beneficial for the customers too. The five competitive forces stated by Porter (Porter, 2008 , Richter et al., 2017 , Silva et al., 2018 , Kingsnorth, 2019 ) can be described as:

Threats of new entrants: Whenever a new competitor enters in a market, it brings worthy potential to gain market shares which eventually affects the prices, which also has the potential to disturb a well-established customer base which will affect the revenue flow.

Power of suppliers: A powerful supplier can be a threat to a company or a customer if it is hugely dependent on the supplies which can be anything like labours, raw materials and car components. In this case, the supplier can easily manipulate the prices of supplies according to its needs.

Power of buyers: This threat is just opposite of the powerful supplier’s threat as in this if leverage lies with the buyer, then he can negotiate for more service for relatively lesser price, which puts a company back on foot and may have to make the deal for lesser profit.

Threats of substitutes: A new and better solution for an existing problem can be a threat to the old solution as the company is providing, it may soon go out of service if it does not improvise or innovate its solution.

Existing competitors: There is a constant sense of rivalry among existing competitors as they compete for market share by advertising, by offering discounts, by doing promotions and organising events which in turn are activities which require a lot of funds, hence should be planned accordingly.

The effects of these five forces can be minimized on a business if that business has a well-established business model (Frison and Kirchberger, 2000 , Jain et al., 2012 Enkel et al., 2013 , Santhanam et al., 2014 , Kleis Nielsen et al., 2018 , Joshi et al., 2018 , Del Vecchio et al., 2018 , Faraj et al., 2018 ,) (Fig. 5 ). Lüttgens and Diener ( 2016 ) studied the Porter’s five forces and were able to identify the trends, and they gave five steps to counteract the business pressure from these five forces in their journal “Business Model Patterns Used as a tool for creating (New) innovative business models, Journal of Business Models” (Del Vecchio et al., 2018 , Gimpel et al., 2018 ). These five steps given by Lüttgens and Diener ( 2016 ) can be described as below:

First, identification of those forces should be done which pose the high risk to the business model, then start looking for various solutions available and pick the best one.

Such business patterns should be chosen from the list of business model innovation which can best handle and counteract the pressure from the identified porter’s force.

Select different business patterns and make different combinations of business models from available patterns and do brainstorming session to identify the best combination.

Do more research on business model patterns if necessary, in order to find new possibilities.

Analyse the model by using various business tools such as CANVAS (Oskam et al., 2016 , Romero et al., 2016 , Schallmo et al., 2018 ) to see the pros and cons of the new business model and implement accordingly.

Five forces of competition. Source (Baldegger et al., 2016 )

Business models of digital platforms

Free as a business model (fbm).

This business model is also known as a freemium/subscription model. This model was proposed by Osterwalder and Pigneur ( 2010 ), and they described this model as a business model in which one customer segment can continuously enjoy the benefit from cost-free services. The most important concept of this model is to provide free of cost value preposition to the customers, and this concept of providing something for free leads to the generation huge demands as compared to something even offered at nominal cost (Tsai et al., 2006 , Feng et al., 2009 , Dierksmeier et al., 2018 ).

As described by them, one of the ways of revenue generation in this business model is possible because of companies which adopt this model earn profit by showing advertisements to the customers using their free services; also, they provide an option to their customers to purchase the premium version of that service which they stop getting ads as well as they get additional services which are not available in the free version, by paying a required amount which again generates revenue. For example, Spotify is a free music streaming service which allows their users to stream from vast number of songs anytime, and they can even create a playlist of their favourite songs and share them with their friends too, and it made Spotify very popular specially among millennials, but this free streaming of songs gets interrupted when advertisements automatically start playing while changing the songs, but users can buy subscription for premium on daily/monthly/half-yearly/yearly basis; by paying the required amount, they become the premium member and enjoy the add-ons like they can download any song and listen them offline, they do not get to see advertisements anymore and they get three times better sound quality, so these add-ons lure more customers to buy premium and hence, they generate revenue (Cennamo et al., 2013 , Hall et al., 2001 , Lindgardt et al., 2009 , Lee et al., 2018 ).

Many start-ups are emerging these days with free as their business model so that they can attract large number of customers to create great demand of their value preposition. Also, this model helps them to take over the existing competitors present in the marketplace. Furthermore, this model can be categorised in three patterns as stated in Tables 2 and 3 .

Pay-per-use business model (PBM)

As the name suggests, in this business model, the customer must pay each for each time they use the services. In this article “Apply pay-per-use business models to your industry”, author Uenlue (Robitzsch et al., 2014 , Lüttgens et al., 2016 , Plantil et al., 2018 ) wrote that pay-per-use model was only limited to few industries like phones and electricity; however, it has been observed that this business model is being adopted widely by many industries such as transport and software (Radanliev et al., 2018 , Holm et al., 2018 ). One of the reason that this model is being widely used and is an efficient model is that it can be combined with subscription model to create more revenue, for example, there are many mobile talk-time package offers for customers to choose from like 1000 min plus 3 GB data per month (Doz et al., 2010 , Kumar et al., 2013 , 2018 ).

Customers get benefits from this model as they only had to pay for what they use, and there is no additional expenses where as companies get benefits from this models if they have well estimated the expenditure-per-use and have fixed price-per-use while keeping the track of the profit-per-use (Hwang et al., 2008 , Øiestad et al., 2014 , Kane et al., 2015 , Boltan et al., 2018 , Meeker et al., 2018 ).

Challenges faced in this model are (Boudreau et al., 2010 , 2015 ):

Unpredictable use and revenue: It is difficult to predict the need of the customers as they use the service only when they feel like, which in turn makes it difficult to calculate the revenue.

Frequent users may give negative response: This model will not be suitable for frequent user of the service/product offered if their repetitive billing amount is more than the one-time cost of the whole service/product.

Ability to meet the demands: It is important that a company should provide its products/services to its customers whenever the demand is made without failing.

This business model can be a very good opportunity for new start-ups and small companies to attract new customer segments and capture the marketplace from lower end (Bossert et al., 2016 ).

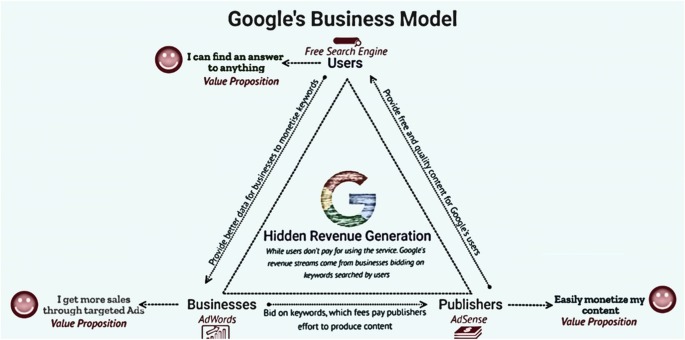

Google Business Model (GBM)

Google uses a promotion business model, where enterprises take part of an ad network called AdWords. In short, they can bid and attempt on keywords (such as “insurance” and “pen drive”) to sell their products and services (Jarvis, 2011 ).

Google generated about $25 billion in revenue in year 2019 using his business model. The vast majority of that revenue, well over 95%, originate from advertising via its search engine and its AdSense program, which places ads on billions of websites (Vise, 2007 , Google Business, 2020 , Mishra and Tripathi, 2020a ).

The contemporary pre-dominant business model for commercial search engines is advertising (Alpdemir, 2003 ). This can also be eminent that Google has become tantamount with web search (Watanabe et al., 2018 ).

The other side of Google’s tremendously efficacious business plan is innovation (Ferreira et al., 2013 ). This is established in the products, consumers and services that Google integrates into its brand. Let us survey the technology behind the product and trade (Orton et al., 1990 , Parker et al., 2018 ).

Google technology (GT)

Google’s search technology is dependent upon computer algorithms to regulate search sitting.

The technology that Google uses to underpin its data centres are of extreme significance in certifying Google has the scale, speed and efficiency to serve its promptly budding number of users (Weber, 2008 ). Google also uses two advertising amenities to gain substantial income: AdWords (places applicable ads together with Google’s search results) and AdSense. Google’s context-driven flyers are on third-party websites (Weber, 2008 , Metallo et al., 2018 ).

Google AdSense

Google believes relevant advertising can be as useful as search results or other forms of content (Google Business, 2020 , Mishra and Tripathi, 2020a , Metallo et al., 2018 ). To this end, Google has developed the AdSense program to enhance the user’s experience to a website. While utilising the technologies behind Google Search, AdSense uses keywords to precisely target results so advertising content is delivered based on page content. Google believes advertisers, publishers and information seekers all profit as a result (Google Business, 2020 , Metallo et al., 2018 ).

Google AdWords

In amalgamation with AdSense, Google developed the “AdWords [program] for advertisers who need to influence a competent viewers as professionally as prospective” (Google Business, 2020 , Mishra and Tripathi, 2020a ).

The PageRank and Hypertext-Matching Analysis seems to function to yield the best potential competitions for a user’s search request. AdWords and AdSense supply content-appropriate advertising centred on the publisher’s content. This effectively produces an association between content producers and advertising producers, spawning sense of grid economy, value and outcome (Watanabe et al., 2018 ).

Customers have needs and nice-to-haves and traditional business models fulfil these for their customers. Google offers its customer’s needs, wants and nice-to-haves for free. In return, whether knowingly or not, users create data whilst using Google amenities and yields which produces statistics and information that is recorded in the Google Search Engine; advertisement is then made-to-order based on the content delivered (Afuah, 2014 ).

The most important for its business model is the billions and billions of websites that make available Google with information and statistics for free. They permit or offer Google to go through the information and statistics on their website and index it. Deprived of this uncooked data, Google does not have a business (Baden-Fuller et al., 2010 , Bucherer et al., 2012 ).

Google’s complete business model rotates about one unpretentious concept—relevancy. The more relevant and appropriate its products are, the more persons use them. More users and consumers invite more advertisers (over 82% of Google’s 2019 revenue was resultant through advertising). And the more money it makes, the more relevant it gets, and the circle goes round and overweight again. The Google’s preoccupation with relevancy fuels a so-called “flywheel effect” (Google Business, 2020 , Mishra and Tripathi, 2020a ).

The flywheel effect states to an honest cycle of improved relevancy. The value-added functionality and usability of all Google merchandises service the tech colossal cultivate robust and smoother over time fascination with relevancy fuels what we call “the flywheel effect”.

Let us discuss a quicker look at about key examples of relevancy in the interior Google’s business model.

Google AdWords and quest advertising

Google is really a meritocracy and practices “Quality Score” to exuberant the direction of connected and network connected advertisements based on relevancy. Ads that have an advanced CTR (i.e., they are more clickable) are supposed to be more relevant to a consumer’s search request and consequently remunerated with a higher ad rank at no extra price tag.

YouTube, as the global ecosphere’s largest video distribution platform, practices relevancy algorithms and quest to create tailor-made consumer involvements. While YouTube is free for community use, YouTube premium is a subscription-based facility with over 30 million participants. In 2019, premium memberships accounted for over $20 billion of Google’s revenue.

Google Map (combined with Google’s attainment of Waze) resources the tech colossal can accumulate data from billions of strategies to design the most efficient directions, paths and routs. Google acquires from past excursions and outings to recommend the most significant and appropriate end point for specific customers and users (Figs. 6 and 7 ).

Google business model (Google Business, 2020 )

Inside Google’s business model

A hidden revenue business model is a conformation for income and revenue group that preserves consumers out of the balance so they do not pay for the amenity or manufactured goods presented. For example, Google‘s consumers do not reward for the search engine. As an alternative, the revenue streams come from advertising currency disbursed by commerce request on keywords (Gatautis, 2017 ).

In past two decades, various business frameworks have been developed, and many business models have been innovated. This state-of-the-art analysis has explained many important attributes in Tables 1 , 2 and 3 that are needed to define business model effectively. Innovation of new technologies has changed the way of doing business over the years, which has made the study on business models in digital marketplaces an important area of research as to do sustainable business in today’s digital marketplace. New business model innovations are required with proper risk management; hence, new frameworks are also needed for development of analysis of these models. We suggest that the challenge of management two different and contradictory business models concurrently can be outlined as an ambidexterity challenge. This implies that ideas and conjectural thoughts from the ambidexterity writings can be used to discover issues applicable to the business model writings. We put on this idea to reconnoitre explicit areas where the ambidexterity works could guide research on the contest of managing business models simultaneously and classify more than a few insights that can guide upcoming research on business model innovation.

A business may do well without any structure or model in the marketplace for a while if the conditions are in its favour but as soon as it starts facing any competition or any of those Porter’s five forces, then it may soon collapse if it does not have a proper plan to counteract these competitive forces or it does not have a business model which if the business has, then it can not only counteract against these forces but also can run sustainably and efficiently for longer period of time.

In this way, digital marketplace keeps innovating, and the experimentation of new business models can be observed; earlier, only industries like electricity and phone used this model but now many companies like Amazon web services and pay-per-view television industries are also using these models. Further, a very unique model which has been reviewed is FREE as a business model which is a very popular business model in the digital marketplace as many start-ups as well as many tech giants try to attract customers with initial service which then may make these customers want for more for which they have to pay. This remarkable change in way doing business led to innovation of new business ideas and better models which can attain more efficiency and sustainability. Google’s hyper-focus on relevancy will carry on to fuel the flywheel outcome and reinforce the company’s label as one of the utmost cherished and efficacious companies on the globe due to his innovative business model.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable

Abbreviations

Software-Based Platforms

Digital Platform

Business Intelligence

Light Speed Venture Partner

DSG Consumer Partner

Business Model

Digital Business Model

Business Cycle Framework

Innovation Radar

Free Business Model

Google Business Model

Google Technology

Pay-per-use Business Model

Abdelkafi, N., Makhotin, S., & Posselt, T. (2013). Business model innovations for electric mobility—what can be learned from existing business model patterns? International Journal of Innovation Management , 17 (01), 1340003.

Article Google Scholar

Afuah, A. (2014). Business model innovation: concepts, analysis, and cases. routledge.

Agostinho, C., Ducq, Y., Zacharewicz, G., Sarraipa, J., Lampathaki, F., Poler, R., & Jardim-Goncalves, R. (2016). Towards a sustainable interoperability in networked enterprise information systems: trends of knowledge and model-driven technology. Computers in Industry , 79 , 64–76.

Allee, V. (2000). Reconfiguring the value network. Journal of Business strategy , 21 (4), 36–39.

Alpdemir, A. (2003). U.S. Patent No. 6,658,389 . Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Google Scholar

Alt, R., Beck, R., & Smits, M. T. (2018). FinTech and the transformation of the financial industry. Electronic Markets, 28 . 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-018-0310-9 .

Antikainen, M., & Valkokari, K. (2016). A framework for sustainable circular business model innovation. Technology Innovation Management Review , 6 (7).

Ardolino, M., Rapaccini, M., Saccani, N., Gaiardelli, P., Crespi, G., & Ruggeri, C. (2018). The role of digital technologies for the service transformation of industrial companies. International Journal of Production Research , 56 (6), 2116–2132.

Autio, E., Nambisan, S., Thomas, L. D., & Wright, M. (2018). Digital affordances, spatial affordances, and the genesis of entrepreneurial ecosystems. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal , 12 (1), 72–95.

Azodolmolky, S., Wieder, P., & Yahyapour, R. (2013). Cloud computing networking: challenges and opportunities for innovations. IEEE Communications Magazine , 51 (7), 54–62.

Baden-Fuller, C., & Morgan, M. S. (2010). Business models as models. Long range planning , 43 (2-3), 156–171.

Baldegger, U., & Gast, J. (2016). On the emergence of leadership in new ventures. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research , 22 (6), 933–957.

Balodi, K. C., & Prabhu, J. (2014). Causal recipes for high performance. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research.

Baporikar, N. (2015). Framework for social change through startups in India. International Journal of Civic Engagement and Social Change (IJCESC) , 2 (1), 30–42.

Barwise, P., & Watkins, L. (2018). The evolution of digital dominance. Digital Dominance: The Power of Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple.

Bason, C. (2018). Leading public sector innovation: co-creating for a better society. Policy Press.

Benlian, A., Kettinger, W. J., Sunyaev, A., Winkler, T. J., & GUEST EDITORS (2018). The transformative value of cloud computing: a decoupling, platformization, and recombination theoretical framework. Journal of management information systems , 35 (3), 719–739.

Berman, S. J., Kesterson-Townes, L., Marshall, A., & Srivathsa, R. (2012). How cloud computing enables process and business model innovation. Strategy & Leadership , 40 (4), 27–35.

Bocken, N. M., Short, S. W., Rana, P., & Evans, S. (2014). A literature and practice review to develop sustainable business model archetypes. Journal of cleaner production , 65 , 42–56.

Bolton, R. N., McColl-Kennedy, J. R., Cheung, L., Gallan, A., Orsingher, C., Witell, L., & Zaki, M. (2018). Customer experience challenges: bringing together digital, physical and social realms. Journal of Service Management , 29 (5), 776–808.

Bossert, O. (2016). A two-speed architecture for the digital enterprise. In Emerging Trends in the Evolution of Service-Oriented and Enterprise Architectures , (pp. 139–150). Cham: Springer.

Chapter Google Scholar

Boudreau, K. (2010). Open platform strategies and innovation: granting access vs. devolving control. Management science , 56 (10), 1849–1872.

Boudreau, K. J., & Jeppesen, L. B. (2015). Unpaid crowd complementors: the platform network effect mirage. Strategic Management Journal , 36 (12), 1761–1777.

Branded marketplace for budget hotels OYO raises $24 M from Greenoaks, Lightspeed, Sequoia & DSG.” (2019. https://www.techcircle.in/2015/03/25/oyo-rooms-raises-20 m-in-funding-from-greenoaks-capital-lightspeed-and-sequoia. [Accessed: 24-Jun-2019].

Brynjolfsson, E., Hofmann, P., & Jordan, J. (2010). Cloud computing and electricity: Beyond the utility model. Commun. Acm , 53 (5), 32–34.

Bucherer, E., Eisert, U., & Gassmann, O. (2012). Towards systematic business model innovation: lessons from product innovation management. Creativity and innovation management , 21 (2), 183–198.

Bucherer, E., & Uckelmann, D. (2011). Business models for the internet of things. In Architecting the internet of things , (pp. 253–277). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Burgess, J., & Green, J. (2018). YouTube: Online video and participatory culture. John Wiley & Sons.

Büyüközkan, G., & Göçer, F. (2018). Digital supply chain: literature review and a proposed framework for future research. Computers in Industry , 97 , 157–177.

Cawley, A., & Preston, P. (2007). Broadband and digital ‘content’in the EU-25: Recent trends and challenges. Telematics and Informatics , 24 (4), 259–271.

Cearley, D. W., Burke, B., Searle, S., & Walker, M. J. (2012). The top 10 strategic technology trends for 2013. The Top, 10.

Cennamo, C., & Santalo, J. (2013). Platform competition: strategic trade-offs in platform markets. Strategic management journal , 34 (11), 1331–1350.

Chaffey, D., Hemphill, T., & Edmundson-Bird, D. (2015). Digital business and e-commerce management . UK: Pearson.

Chesbrough, H., & Rosenbloom, R. S. (2002). The role of the business model in capturing value from innovation: evidence from Xerox Corporation’s technology spin-off companies. Industrial and corporate change , 11 (3), 529–555.

Circenis, E., Miller, G., & Lehr, R. C. (2009). U.S. Patent No. 7,571,143 . Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Clark, T., Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2012). Business model you: a one-page method for reinventing your career. John Wiley & Sons.

Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. economica, 4(16), 386-405.

de Oliveira, A. R., & Proença, A. (2019). Design principles for research & development performance measurement systems: a systematic literature review. Brazilian Journal of Operations & Production Management , 16 (2), 227–240.

de Reuver, M., Sørensen, C., & Basole, R. C. (2018). The digital platform: a research agenda. Journal of Information Technology , 33 (2), 124–135.

de Vasconcelos Gomes, L. A., Facin, A. L. F., Salerno, M. S., & Ikenami, R. K. (2018). Unpacking the innovation ecosystem construct: Evolution, gaps and trends. Technological Forecasting and Social Change , 136 , 30–48.

Del Vecchio, P., Di Minin, A., Petruzzelli, A. M., Panniello, U., & Pirri, S. (2018). Big data for open innovation in SMEs and large corporations: trends, opportunities, and challenges. Creativity and Innovation Management , 27 (1), 6–22.

Dierksmeier, C., & Seele, P. (2018). Cryptocurrencies and business ethics. Journal of Business Ethics , 152 (1), 1–14.

Doz, Y. L., & Kosonen, M. (2010). Embedding strategic agility: a leadership agenda for accelerating business model renewal. Long range planning , 43 (2-3), 370–382.

Enkel, E., & Mezger, F. (2013). Imitation processes and their application for business model innovation: an explorative study. International Journal of Innovation Management , 17 (01), 1340005.

Evans, D. S. (2009). The online advertising industry: economics, evolution, and privacy. Journal of economic perspectives , 23 (3), 37–60.

Faraj, S., Pachidi, S., & Sayegh, K. (2018). Working and organizing in the age of the learning algorithm. Information and Organization , 28 (1), 62–70.

Feng, C. G., Lau, T. Y., Atkin, D. J., & Lin, C. A. (2009). Exploring the evolution of digital television in China: an interplay between economic and political interests. Telematics and Informatics , 26 (4), 333–342.

Ferreira, F. N. H., Proença, J. F., Spencer, R., & Cova, B. (2013). The transition from products to solutions: external business model fit and dynamics. Industrial Marketing Management , 42 (7), 1093–1101.

Frison, M. R., & Kirchberger, B. L. (2000). U.S. Patent No. 6,049,789 . Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Gatautis, R. (2017). The rise of the platforms: Business model innovation perspectives. Engineering Economics , 28 (5), 585–591.

Gawer, A., & Cusumano, M. A. (2014). Industry platforms and ecosystem innovation. Journal of product innovation management , 31 (3), 417–433.

Gawer, A., & Henderson, R. (2007). Platform owner entry and innovation in complementary markets: evidence from Intel. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy , 16 (1), 1–34.

Ghazawneh, A., & Henfridsson, O. (2013). Balancing platform control and external contribution in third-party development: the boundary resources model. Information systems journal , 23 (2), 173–192.

Ghezzi, A., & Cavallo, A. (2018). Agile business model innovation in digital entrepreneurship: lean Startup approaches. Journal of business research.

Gimpel, H., Hosseini, S., Huber, R., Probst, L., Röglinger, M., & Faisst, U. (2018). Structuring digital transformation: a framework of action fields and its application at ZEISS. Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application , 19 (1), 31–54.

Goerzig, D., & Bauernhansl, T. (2018). Enterprise architectures for the digital transformation in small and medium-sized enterprises. Procedia CIRP , 67 , 540–545.

Google Business. (2020). https://static.googleusercontent.com/media/www.google.com/en//adsense/start/pdf/AdSense_GettingStartedGuide.pdf . (Retrieved on May, 2020).

Grewal, D., Motyka, S., & Levy, M. (2018). The evolution and future of retailing and retailing education. Journal of Marketing Education , 40 (1), 85–93.

Hall, R. E. (2001). Digital dealing: how e-markets are transforming the economy. WW Norton.

Hamari, J., Sjöklint, M., & Ukkonen, A. (2016). The sharing economy: why people participate in collaborative consumption. Journal of the association for information science and technology , 67 (9), 2047–2059.

Hein, A., Schreieck, M., Riasanow, T. et al. (2019) Digital platform ecosystems. Electron Markets. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12525-019-00377-4 .

Hofmann, P., & Woods, D. (2010). Cloud computing: the limits of public clouds for business applications. IEEE Internet Computing , 14 (6), 90–93.

Holm, A. B., & Haahr, L. (2018). E-recruitment and selection. In e-HRM (pp. 172-195). Routledge.

Hwang, J., & Christensen, C. M. (2008). Disruptive innovation in health care delivery: a framework for business-model innovation. Health affairs , 27 (5), 1329–1335.

Jain, R., & Ali, S. W. (2012). Personal characteristics of Indian entrepreneurs and intrapreneurs: an empirical study. Management and Labour Studies , 37 (4), 295–322.

Jarvis, J. (2011). What would Google do?: Reverse-engineering the fastest growing company in the history of the world. Harper business.

Joshi, D., & Achuthan, S. (2018). Leadership in Indian high-tech start-ups: lessons for future. In The Future of Leadership , (pp. 39–91). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

Kane, G. C., Palmer, D., Phillips, A. N., Kiron, D., & Buckley, N. (2015). Strategy, not technology, drives digital transformation. MIT Sloan Management Review and Deloitte University Press , 14 (1-25).

Kingsnorth, S. (2019). Digital marketing strategy: an integrated approach to online marketing . Kogan Page Publishers.

Kleis Nielsen, R., & Ganter, S. A. (2018). Dealing with digital intermediaries: a case study of the relations between publishers and platforms. New media & society , 20 (4), 1600–1617.

Kumar, K. G. S., Thampi, P. P., Jyotishi, A., & Bishu, R. (2013). Toward strategically aligned innovative capability: a QFD-based approach. Quality Management Journal , 20 (4), 37–50.

Kumar, V., Lahiri, A., & Dogan, O. B. (2018). A strategic framework for a profitable business model in the sharing economy. Industrial Marketing Management , 69 , 147–160.

Kurt, O. E., Ucler, C., & Vayvay, O. (2017). From ideation towards innovation: pillars of front-end in new product development. Press Academia Procedia , 5 (1), 71–79.

Lamberton, C., & Stephen, A. T. (2016). A thematic exploration of digital, social media, and mobile marketing: research evolution from 2000 to 2015 and an agenda for future inquiry. Journal of Marketing , 80 (6), 146–172.

Laudon, K. C., & Laudon, J. P. (2016). Management information system. Pearson Education India

Lee, I., & Shin, Y. J. (2018). Fintech: Ecosystem, business models, investment decisions, and challenges. Business Horizons , 61 (1), 35–46.

Lestan, M., Urgo, J., & Khoriaty, A. (2017). District0x Network - a cooperative of decentralized marketplaces and communities. https://district0x.io/docs/district0x-whitepaper.pdf . Accessed 10.04.2020.

Li, F. (2018). The digital transformation of business models in the creative industries: a holistic framework and emerging trends. Technovation.

Li, S., Da Xu, L., & Zhao, S. (2018). 5G Internet of Things: a survey. Journal of Industrial Information Integration , 10 , 1–9.

Lindgardt, Z., Reeves, M., Stalk, G., & Deimler, M. S. (2009). Business model innovation. When the Game Gets Tough, Change the Game, The Boston Consulting Group, Boston, MA.

Lockamy III, A. (2011). Benchmarking supplier risks using Bayesian networks. Benchmarking: An International Journal , 18 (3), 409–427.

Lockamy III, A., & McCormack, K. (2012). Modeling supplier risks using Bayesian networks. Industrial Management & Data Systems , 112 (2), 313–333.

Luby, M. J., Howie, P. J., Parker, B. C., Kozloff, J. A., Crook, J. T., Cohen, D. J., & Priest, A. R. (2006). U.S. Patent No. 7,080,027 . Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Lüttgens, D., & Diener, K. (2016). Business model patterns used as a tool for creating (new) innovative business models. Journal of Business Models , 4 (3).

Meeker, M., & Wu, L. (2018). Internet trends 2018 .

Metallo, C., Agrifoglio, R., Schiavone, F., & Mueller, J. (2018). Understanding business model in the Internet of Things industry. Technological Forecasting and Social Change , 136 , 298–306.

Mishra, S. (2019). Performance analysis of women in Central Bank Monetary System using business intelligence. Global Journal of Management and Business Research, (A), XIX (III), 23–28.

Mishra, S., & Triptahi, A.R. (2019). Platforms oriented business and data analytics in digital ecosystem. International Journal of Financial Engineering, 6 (04), 1950036.

Mishra, S., & Tripathi, A.R. (2020a). IoT Platform Business Model for Innovative Management Systems. International Journal of Financial Engineering , 2050030. https://doi.org/10.1142/S2424786320500309 .

Mishra, S., & Tripathi, A.R. (2020b). Platform business model on state-of-the-art business learning use case. International Journal of Financial Engineering , 2050015.

Nambisan, S., Wright, M., & Feldman, M. (2019). The digital transformation of innovation and entrepreneurship: Progress, challenges and key themes. Research Policy , 48 (8), 103773.

Nieborg, D. B., & Poell, T. (2018). The platformization of cultural production: theorizing the contingent cultural commodity. New Media & Society , 20 (11), 4275–4292.

Øiestad, S., & Bugge, M. M. (2014). Digitisation of publishing: exploration based on existing business models. Technological Forecasting and Social Change , 83 , 54–65.

Ordanini, A., Micelli, S., & Di Maria, E. (2004). Failure and success of B-to-B exchange business models: a contingent analysis of their performance. European Management Journal , 22 (3), 281–289.

O'Reilly, T. (2011). Government as a platform. Innovations: Technology, Governance, Globalization , 6 (1), 13–40.

Orton, J. D., & Weick, K. E. (1990). Loosely coupled systems: a reconceptualization. Academy of management review , 15 (2), 203–223.

Oskam, J., & Boswijk, A. (2016). Airbnb: the future of networked hospitality businesses. Journal of Tourism Futures , 2 (1), 22–42.

Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2002). An eBusiness model ontology for modeling eBusiness. BLED 2002 proceedings, 2.

Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2004). An ontology for e-business models. Value creation from e-business models, 1, 65-97.

Osterwalder, A., & Pigneur, Y. (2010). Business model generation: a handbook for visionaries, game changers, and challengers. John Wiley & Sons.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., Oliveira, M. A. Y., & Ferreira, J. J. P. (2011). Business Model Generation: A handbook for visionaries, game changers and challengers. African journal of business management , 5 (7), 22–30.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., & Tucci, C. L. (2005). Clarifying business models: origins, present, and future of the concept. Communications of the association for Information Systems, 16(1), 1.

Parker, G., & Van Alstyne, M. (2018). Innovation, openness, and platform control. Management Science , 64 (7), 3015–3032.

Parker, G., Van Alstyne, M. W., & Jiang, X. (2016). Platform ecosystems: how developers invert the firm. Boston University Questrom School of Business Research Paper , 2861574 .

Pisano, P., Pironti, M., & Rieple, A. (2015). Identify innovative business models: can innovative business models enable players to react to ongoing or unpredictable trends? Entrepreneurship Research Journal , 5 (3), 181–199.

Plantin, J. C., Lagoze, C., Edwards, P. N., & Sandvig, C. (2018). Infrastructure studies meet platform studies in the age of Google and Facebook. New Media & Society , 20 (1), 293–310.

Porat, M., Surace, K. J., & Milgrom, P. (2008). U.S. Patent No. 7,330,826 . Washington, DC: U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

Porter, M. E. (2008). The five competitive forces that shape strategy. Harvard business review , 86 (1), 25–40.

Radanliev, P., De Roure, D., Nurse, J. R., Nicolescu, R., Huth, M., Cannady, S., & Montalvo, R. M. (2018). Integration of cyber security frameworks, models and approaches for building design principles for the internet-of-things in industry 4.0.

Reynolds, R. (2011). Trends influencing the growth of digital textbooks in US higher education. Publishing Research Quarterly , 27 (2), 178–187.

Richter, C., Kraus, S., Brem, A., Durst, S., & Giselbrecht, C. (2017). Digital entrepreneurship: innovative business models for the sharing economy. Creativity and Innovation Management , 26 (3), 300–310.

Robitzsch, A., Kiefer, T., George, A. C., & Uenlue, A. (2014). CDM: cognitive diagnosis modeling. R package version 3.1-14.

Romero, D., & Vernadat, F. (2016). Enterprise information systems state of the art: past, present and future trends. Computers in Industry , 79 , 3–13.

Sabatier, V., Craig-Kennard, A., & Mangematin, V. (2012). When technological discontinuities and disruptive business models challenge dominant industry logics: insights from the drugs industry. Technological Forecasting and Social Change , 79 (5), 949–962.

Santhanam, M. (2014). Leaders don’t build leaders: know the 3 reasons. Leadership Excellence , 31 (6), 60.

Schallmo, D. R., & Williams, C. A. (2018). Digital Transformation Now!: Guiding the Successful Digitalization of Your Business Model. Springer.

Shrutika, M. (2018) Financial management and forecasting using business intelligence and big data analytic tools. International Journal of Financial Engineering, 05 (02), 1850011.

Silva, B. N., Khan, M., & Han, K. (2018). Towards sustainable smart cities: a review of trends, architectures, components, and open challenges in smart cities. Sustainable Cities and Society , 38 , 697–713.

Sinha, S. (2015). The exploration–exploitation dilemma: a review in the context of managing growth of new ventures. Vikalpa , 40 (3), 313–323.

Skog, D. A., Wimelius, H., & Sandberg, J. (2018). Digital disruption. Business & Information Systems Engineering , 60 (5), 431–437.

Smith, M. D., & Brynjolfsson, E. (2001). Consumer decision-making at an Internet shopbot: Brand still matters. The Journal of Industrial Economics , 49 (4), 541–558.

Solis, B., Li, C., & Szymanski, J. (2014). The 2014 state of digital transformation. Altimeter Group.

Speranza, M. G. (2018). Trends in transportation and logistics. European Journal of Operational Research , 264 (3), 830–836.

Spiess-Knafl, W., Mast, C., & Jansen, S. A. (2015). On the nature of social business model innovation. Social Business , 5 (2), 113–130.

Spieth, P., Schneckenberg, D., & Ricart, J. E. (2014). Business model innovation–state of the art and future challenges for the field. R&d Management , 44 (3), 237–247.

Standing, C., & Mattsson, J. (2018). “Fake it until you make it”: business model conceptualization in digital entrepreneurship. Journal of Strategic Marketing , 26 (5), 385–399.

Sutherland, W., & Jarrahi, M. H. (2018). The sharing economy and digital platforms: a review and research agenda. International Journal of Information Management , 43 , 328–341.

Täuscher, K. (2016). Business models in the digital economy: an empirical study of digital marketplaces. Fraunhofer MOEZ, Fraunhofer Center for International Management and Knowledge Economy, Working Paper, (2).

Täuscher, K., & Abdelkafi, N. (2017). Visual tools for business model innovation: recommendations from a cognitive perspective. Creativity and Innovation Management , 26 (2), 160–174.

Täuscher, K., & Abdelkafi, N. 9 (2018) Modelling the lean startup: simulation tool for entrepreneurial growth decisions.

Täuscher, K., & Chafac, M. (2016). Supporting business model decisions: a scenario-based simulation approach. International Journal of Markets and Business Systems , 2 (1), 45–67.

Täuscher, K., & Laudien, S. M. (2017, January). Uncovering the nature of platform-based business models: an empirical taxonomy. In Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences.

Teece, D. J. (2010). Business models, business strategy and innovation. Long range planning , 43 (2-3), 172–194.

Tian, X., & Martin, B. (2011). Impacting forces on ebook business models development. Publishing research quarterly , 27 (3), 230.

Tidd, J., & Bessant, J. R. (2018). Managing innovation: integrating technological, market and organizational change. John Wiley & Sons.

Timmers, P. (1998). Business models for electronic markets. Electronic markets , 8 (2), 3–8.

Tsai, S. D., & Lan, T. T. (2006). Development of a startup business—a complexity theory perspective . Kaohsiung, Taiwan: National Sun Yat-Sen University.

Van Dijck, J., Poell, T., & De Waal, M. (2018). The platform society: Public values in a connective world . Oxford University Press.

Vikas, O. (2012a). Challenges in accreditation of engineering education for sustainable development. Editorial Board Members, 260.

Vikas, O. (2012b). Innovation-centric teaching and learning processes in technical education. Journal of Modern Education Review (ISSN 2155-7993) , 2 (2), 116–131.

Vise, D. (2007). The google story. Strategic Direction.

Book Google Scholar

Watanabe, C., Naveed, K., & Neittaanmäki, P. (2016). Co-evolution of three mega-trends nurtures un-captured GDP–Uber’s ride-sharing revolution. Technology in Society , 46 , 164–185.

Watanabe, C., Naveed, N., & Neittaanmäki, P. (2018). Digital solutions transform the forest-based bio economy into a digital platform industry-A suggestion for a disruptive business model in the digital economy. Technology in Society , 54 , 168–188.

Weber, M. (2008). The business case for corporate social responsibility: A company-level measurement approach for CSR. European Management Journa l, 26 (4), 247–261.

Weinhardt, C., Anandasivam, A., Blau, B., Borissov, N., Meinl, T., Michalk, W., & Stößer, J. (2009b). Cloud computing–a classification, business models, and research directions. Business & Information Systems Engineering , 1 (5), 391–399.

Weinhardt, C., Anandasivam, A., Blau, B., & Stößer, J. (2009a). Business models in the service world. IT professional, (2), 28-33.

Werth, D., & Greff, T. (2018). Scalability in consulting: insights into the scaling capabilities of business models by digital technologies in consulting industry. In Digital Transformation of the Consulting Industry , (pp. 117–135). Cham: Springer.

Wirtz, B. W., Schilke, O., & Ullrich, S. (2010). Strategic development of business models: implications of the Web 2.0 for creating value on the internet. Long range planning , 43 (2-3), 272–290.

Wu, D., Rosen, D. W., Wang, L., & Schaefer, D. (2015). Cloud-based design and manufacturing: a new paradigm in digital manufacturing and design innovation. Computer-Aided Design , 59 , 1–14.

Xu, L. D., Xu, E. L., & Li, L. (2018). Industry 4.0: state of the art and future trends. International Journal of Production Research , 56 (8), 2941–2962.

Yin, Y., Stecke, K. E., & Li, D. (2018). The evolution of production systems from Industry 2.0 through Industry 4.0. International Journal of Production Research, 56(1-2), 848-861.

Yoo, Y., Boland Jr., R. J., Lyytinen, K., & Majchrzak, A. (2012). Organizing for innovation in the digitized world. Organization science , 23 (5), 1398–1408.

Yoo, Y., Henfridsson, O., & Lyytinen, K. (2010). Research commentary—the new organizing logic of digital innovation: an agenda for information systems research. Information systems research , 21 (4), 724–735.

Zott, C., Amit, R., & Massa, L. (2011). The business model: recent developments and future research. Journal of management , 37 (4), 1019–1042.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors are highly thankful to the editor and reviewers for their kind suggestions and critical comments for the improvement of the paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Commerce, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, 221005, India

Shrutika Mishra & A. R. Tripathi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The first and corresponding author is responsible for literature review, analysis and critical comments. The second author is responsible for the writing skill and supervison. We have studied various literatures and Literature Review on Business Prototypes for Digital Platform. The literature review will be very useful for working in this area and connecting fields. This paper will be useful for learning researchers and middle level researchers also. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Shrutika Mishra .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Mishra, S., Tripathi, A.R. Literature review on business prototypes for digital platform. J Innov Entrep 9 , 23 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-020-00126-4

Download citation

Received : 27 September 2019

Accepted : 30 June 2020

Published : 01 October 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-020-00126-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Business models

- Digital marketplace

- Digital platform

Failure of Tech Startups: A Systematic Literature Review

- Conference paper

- First Online: 01 May 2023

- Cite this conference paper

- José Santisteban ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4526-642X 11 ,

- Vicente Morales ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5830-5024 12 ,

- Sussy Bayona ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7133-9106 13 &

- Johana Morales ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8572-8970 14

Part of the book series: Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems ((LNNS,volume 678))

Included in the following conference series:

- International Conference on Computer Science, Electronics and Industrial Engineering (CSEI)

408 Accesses

Tech Startups are exposed to multiple challenges and are known for being inserted into uncertain and risky scenarios. Initially, new businesses face great uncertainty and have high failure rates, but a minority of them go on to become successful and influential. The purpose of this study is to determine the main causes of failure of Tech Startups in their early stage, for which a systematic review of empirical studies regarding why Tech Startups fail was carried out. The search strategy in the databases: ScienceDirect, IEEE Xplore, SpringerLink, Emerald and EBSCO identified 1996 studies of which 36 were identified as empirical studies and after applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 23 primary studies were selected that classify to the factors in 3 categories: organizational, technological, and environmental. Among the main factors for failure are the characteristics of the owner, poor location of the business, products/services that do not meet the needs, high costs of ICT, lack of skills in the entrepreneurial team, external and competitive pressure, few benefits perceived ICT use, low resources, low government support.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Al Sahaf, M., Al Tahoo, L.: Examining the key success factors for startups in the kingdom of Bahrain. Int. J. Bus. Ethics Gov. 4 (2), 9–49 (2021)

Article Google Scholar

Bajwa, S.S., Wang, X., Nguyen Duc, A., Abrahamsson, P.: “failures” to be celebrated: an analysis of major pivots of software startups. Empir. Softw. Eng. 22 (5), 2373–2408 (2017)

Google Scholar

Cantamessa, M., Gatteschi, V., Perboli, G., Rosano, M.: Startups’ roads to failure. Sustainability 10 (7), 2346 (2018)

Cepeda Vaca, F., et al.: Controlled high pressure grinding roll by model predictive control. In: 2017 IEEE 3RD Colombian Conference on Automatic Control (CCAC) (2017)

Chong, Z., Luyue, Z.: The financing challenges of startups in China (2014)

Escolano, V.J.C.: Successes and failures of startups in the Philippines: an exploratory study. In: 2022 7th International Conference on Business and Industrial Research (ICBIR), pp. 610–615. IEEE (2022)

Finkelstein, S.: Internet startups: so why can’t they win? J. Bus. Strateg. 22 (4), 16–16 (2001)