Essay on Personality Development

Students are often asked to write an essay on Personality Development in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Personality Development

Introduction.

Personality Development refers to enhancing one’s traits for a holistic growth. It’s about improving communication, leadership skills, and maintaining a positive attitude.

Importance of Personality Development

A strong personality helps in better interaction and boosts confidence. It helps us to face challenges and achieve success.

Factors Influencing Personality Development

Various factors like environment, education, and relationships shape our personality. These elements help us grow and evolve as individuals.

Personality Development is a continuous process. It helps us to be better versions of ourselves, making us more adaptable and successful in life.

Also check:

- Speech on Personality Development

250 Words Essay on Personality Development

Personality development is a comprehensive term that encapsulates the improvement of an individual’s traits and attributes, which contribute to their overall character and image. It is an ongoing process that involves the growth and maturation of one’s personality, leading to self-awareness and personal enhancement.

Significance of Personality Development

Personality development is crucial as it enables individuals to enhance their interpersonal skills, which are vital in today’s highly competitive world. It aids in the development of traits such as confidence, optimism, and resilience, which are key to overcoming life’s challenges. Furthermore, it promotes effective communication skills, leadership qualities, and emotional intelligence, which are integral to personal and professional success.

Several factors influence personality development. The environment, including family, school, and community, plays a significant role in shaping one’s personality. The experiences, both positive and negative, that an individual encounters throughout their life also contribute to their personality development. Genetic factors, although not entirely controllable, also play a part in defining an individual’s temperament and behavior.

In conclusion, personality development is a lifelong process that involves the continuous growth and enhancement of an individual’s character and attributes. It is a critical aspect of human development that can significantly influence one’s personal, academic, and professional success. Therefore, it is essential for individuals to focus on their personality development and strive for continuous self-improvement.

500 Words Essay on Personality Development

Personality development is an enduring process of cultivating behaviors, attitudes, and communication patterns that make an individual distinctive. It involves both the improvement of personal traits and the development of a holistic persona that plays a crucial role in achieving success in life.

The Essence of Personality Development

Personality development is not confined to the improvement of a single aspect of an individual; instead, it is about improving an amalgamation of factors that would include the ability to communicate effectively, confidence building, and the overall personality. It can be considered as a tool that helps in enhancing one’s self-esteem and confidence, thereby making an individual more presentable and acceptable in the social context.

Several factors contribute to personality development, including genetic predisposition, upbringing, education, environment, and experiences. Genetic factors contribute to the fundamental aspects of personality, such as temperament. Upbringing and education, on the other hand, shape our values, beliefs, and attitudes.

Environment and experiences play a significant role in shaping our personality. The environment we are exposed to, the people we interact with, and the experiences we have all contribute to the development of our personality. Positive experiences contribute to a confident, well-adjusted personality, while negative experiences may lead to a lack of confidence and low self-esteem.

Role of Personality Development in Success

Personality development plays a vital role in our success, both personally and professionally. A well-developed personality is a key to success as it enhances our ability to communicate effectively, improves our confidence, and helps us in building relationships. It allows us to present ourselves effectively in various situations, thereby opening up opportunities for growth and success.

The Process of Personality Development

Personality development is a continuous process that starts from the time we are born and continues throughout our life. It involves a constant interaction between our innate characteristics and the environment. This process can be influenced by consciously deciding to improve ourselves by learning new skills, adopting healthy habits, and developing positive attitudes.

In conclusion, personality development is an essential aspect of our lives that influences our success and happiness. It is a continuous process that requires conscious effort and commitment. By understanding the factors that influence our personality and taking steps to develop our personality, we can enhance our potential, improve our relationships, and achieve success in life.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on My Favourite Personality

- Essay on Himachal Pradesh

- Essay on Success and Hard Work

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

One Comment

Personal development

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

ADMISSIONS OPEN

+91-9873167900

Blog Single

Importance of personality development for students.

Have you ever wondered what truly sets your child up for success in life? Sure, good grades and academic achievements are crucial, but there’s something equally—if not more—important: personality development.

When we talk about “personality,” we’re not just referring to a set of traits or behaviours; we’re talking about the very essence of who we are—the way we think, feel, and act. In recent years, there’s been a growing recognition worldwide of the pivotal role personality development plays in a student’s journey. Why? Because a well-rounded personality doesn’t just shape how we approach life; it also paves the way for brighter futures, enhancing our chances of success in the professional arena.

Today’s educational landscape is evolving, with a renewed emphasis on nurturing students’ personalities alongside academic achievements. But here’s the catch: while we all agree on the significance of personality development, the real challenge lies in knowing how to foster these skills effectively.

So, let’s roll up our sleeves and demystify the importance of personality development in children that our educators follow at The Blue Bells School.

Confidence Boost: We all know confidence is key! When your child feels good about themselves, they’re more likely to take on challenges, speak up in class, and pursue their dreams without hesitation.

We observed that personality development workshops and activities can work wonders in boosting your child’s self-esteem and belief in themselves

Effective Communication:

In a world that’s increasingly interconnected, strong communication skills are non-negotiable. Whether it’s expressing ideas, negotiating with peers, or presenting in front of an audience, the ability to communicate effectively can open doors to endless opportunities. Personality development helps your child become a stellar communicator, both verbally and non-verbally.

Emotional Intelligence:

Life isn’t just about acing exams; it’s also about handling emotions, relationships, and setbacks. By understanding and managing their own emotions and empathising with others, your child can build healthier relationships, resolve conflicts constructively, and thrive in various social settings. Personality development nurtures this vital aspect of your child’s growth.

Adaptability and Resilience:

Let’s face it: life throws curveballs. From unexpected challenges to major transitions, your child needs to be resilient and adaptable. Personality development equips them with the tools to bounce back from setbacks, embrace change, and thrive in diverse environments. It’s all about building that mental toughness and flexibility!

Leadership Potential:

Whether your child aspires to lead a team, start their own business, or simply be a positive influence among their peers, leadership skills are invaluable. Through personality development activities like teamwork, problem-solving, and decision-making, your child can unleash their leadership potential and inspire others along the way.

Now, you might be thinking, “Okay, this all sounds great, but how do we actually foster personality development?” We’ve got you covered:

- Lead by Example: Children learn by example, so be a role model for positive traits like empathy, resilience, and effective communication. Show them what it means to embrace challenges with a growth mindset and treat others with kindness and respect.

- Provide Constructive Feedback: Offer praise and constructive feedback to help your child understand their strengths and areas for growth. Encourage them to set goals and celebrate their progress along the way.

- Expose Them to Diverse Experiences: Exposure to different cultures, perspectives, and environments can broaden your child’s horizons and foster adaptability and open-mindedness.

In a nutshell, personality development isn’t just another buzzword—it’s the secret sauce that empowers your child to thrive in school, relationships, and beyond.

Picture your child walking into a room full of strangers. How they carry themselves, communicate, and handle situations speaks volumes about their personality. That’s where personality development kicks in.

At The Blue Bells School we believe it’s not just about being outgoing or confident; it’s about honing a set of skills and traits that help your child navigate life’s ups and downs with grace and resilience.

Related News

Teaching Your Child the Art of Time Management

How to Raise a Kind and Compassionate Child

5 Ways to Improve Your Child’s Memory

7 Lessons That Parents Can Learn From Their Kids

Remember Me

EnglishGrammarSoft

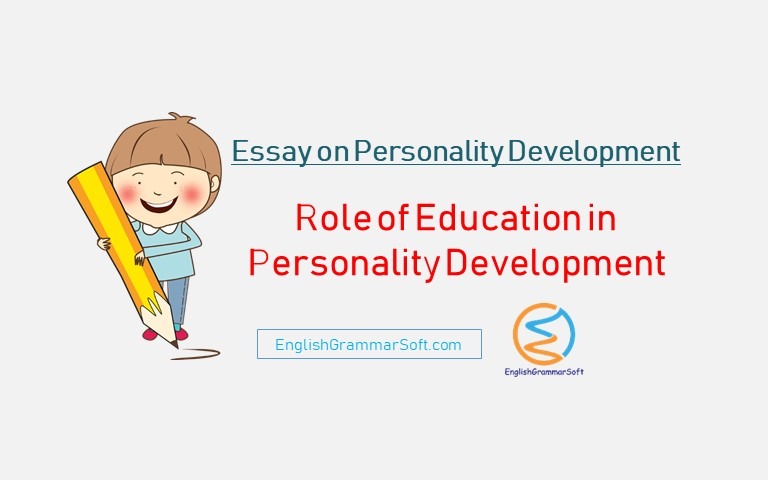

Essay on Personality Development | Role of Education in Personality Development

- Essay on Personality Development

Education is an important factor in the personality development of individuals. The school, after the home, is one of the social structures every child will pass through and one of its purposes is to build the character of that child. We shall be looking at some of the roles it plays in this process.

What is personality development?

Personality development is the process of expanding your personality. This may include doing activities that you don’t normally do, but find enjoyable and fulfilling like playing a new sport or trying new hobbies. It also includes developing skills that you already have but are not using to their full potential such as playing an instrument or speaking another language. Developing your personality can also mean discovering who you are in order to better understand yourself and grow into the person that’s right for you.

Character Development

As I stated earlier, the school plays a great role in the overall personality development of an individual.

From childhood, the child is exposed to this social setting and spends most of his day there. The influence that education, which is the major service the schools offer, has on the child cannot be overlooked.

After the home front, the school is responsible for the upbringing of children and their overall character development. Therefore, there should be a deliberate effort to ensure that the character of the child is molded properly during this time. Education is not just about teaching theory to children, but a school environment is a place where a good foundation is laid for children to help in the future.

In school, virtues such as honesty, fairness, kindness, and respect are taught. The teachers and educationists have a tremendous influence on students and they are seen as role models so it is necessary that set good examples always.

You must understand that children learn very well by observation so care must be taken to how teachers behave before their students. In school, there are a lot of planned actions and activities that are carried out in the classroom to help students develop a good character which will help them in life.

I shall go through some of these as I go on. There are some important things that should be put in place to help students build their character.

There are several methods of building character in students and when the character is inbuilt in the student, positive behavior is almost automatic. There are several schools of thought that have provided different pillars that help build character.

Here, I have listed a combination of these pillars to help in the personality development of our young ones. They are:

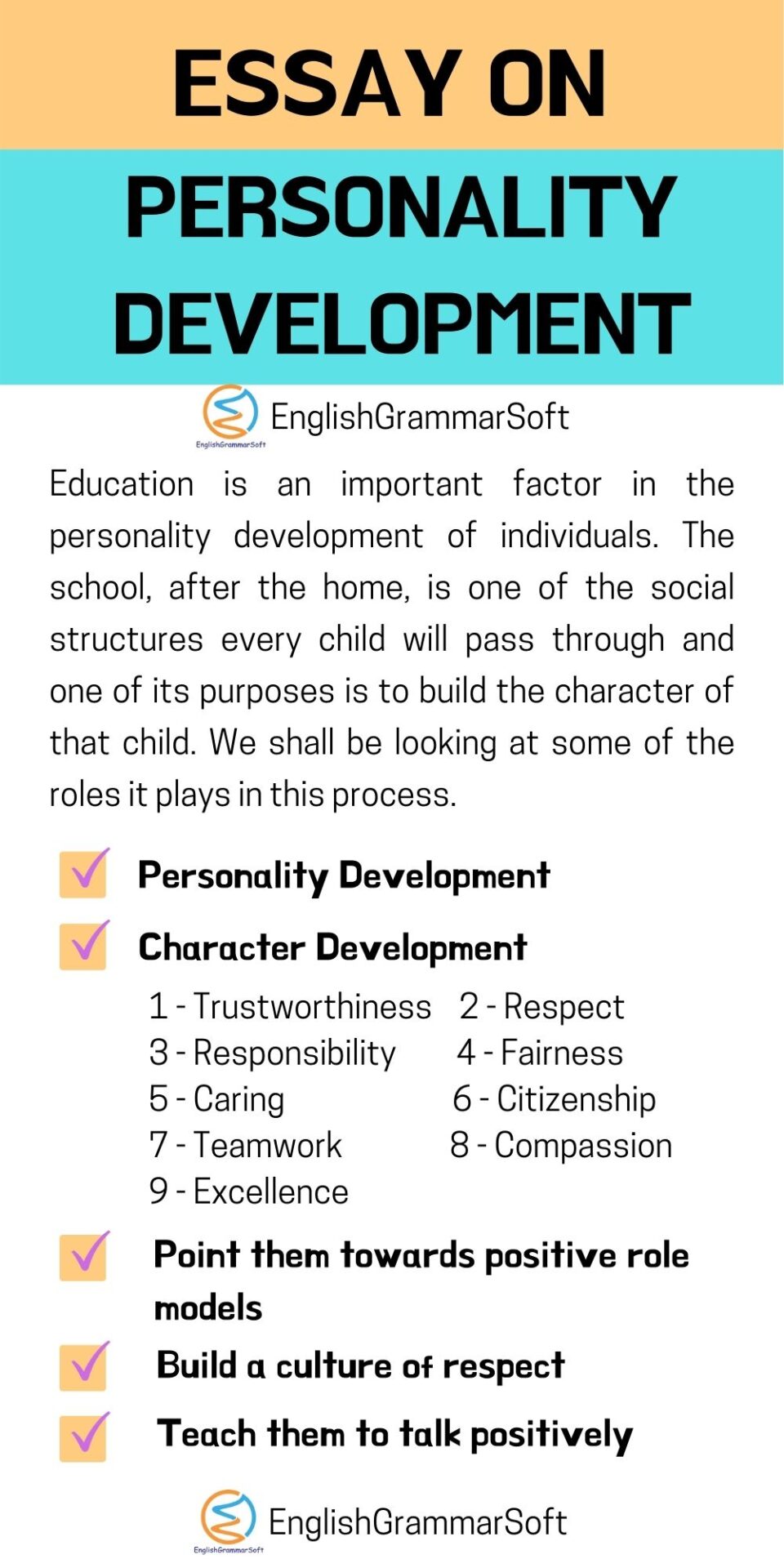

1.1 – TRUSTWORTHINESS

They should be taught the importance of being trustworthy which basically is to learn how to keep their words. Students would learn the need to be honest and sincere; the need to be a person of integrity and why they should be reliable.

1.2 – RESPECT

They should be taught the need to show respect to others by being courteous, acting with dignity, giving autonomy, tolerating opposing views, and accepting criticism.

1.3 – RESPONSIBILITY

They should be taught the need to be responsible for all their actions and daily living.

1.4 – FAIRNESS

This is a character trait of being fair to all and in all situations. They should be taught the importance of this.

1.5 – CARING

The students should be shown why this character trait is essential and how it tells well of them.

1.6 – CITIZENSHIP

This enables students to learn the importance of contributing to the good of society.

1.7 – TEAMWORK

This character trait would help students learn how to work with others in a team. It helps teach them how to tolerate others and their viewpoints.

1.8 – EXCELLENCE

The student should learn how important it is to excel in whatever they do and that excellence has its rewards.

1.9 – COMPASSION

Student should learn to have compassion for and be empathetic to the needs and challenges of others. To teach the students these character traits, you can spread them out and emphasize one of them each month. The students can be encouraged to research on each trait and can be assigned creative writing projects on them.

Set the rules

In the classroom, the teacher should set the necessary rules that will guide the behavior of the student.

Be clear of what is acceptable and unacceptable. It is also advisable to discuss them with the students. To make this work, make sure that you set an example for them so that it would be easier for them to follow.

You should be kind, neat, and punctual in class. You should also show respect to others and finish your work within schedule. By doing so, they will realize that they themselves do not have an excuse to fail or disregard rules.

To achieve maximum results, the teacher will need to explain to the student the character traits which each rule is meant to build. The teacher can also allow the students to make suggestions on possible rules that would be of benefit to the class.

They should always exhibit positive behavior so as to become role models for the students. It would also be good if a reward system can be put in place to reward good behavior.

Point them towards positive role models

Another way by which individuals can build their personality properly is to have good examples of heroes and role models in various fields of study.

Students would easily want to measure up to the character of someone they admire. The teacher should talk about such people that the students can learn from.

They can also be asked to describe, assess, and match the personality traits and behaviors of those people. The teacher can also talk about the behavior and lifestyle of current world leaders and celebrities and as the student to assess if their words match their actions.

Build a culture of respect

Teachers should teach students the need for them to develop self-respect and understand the importance of showing others respect. They can be shown with examples of the benefits of treating others with respect.

Teach them to talk positively

The students can be encouraged to learn how to talk right. Positive talk produces good results both now and in the future. Show them how their words affect their future.

Further Reading

- How to Write an Essay | Structure of Essay (Comprehensive Guide)

- Essay on Happiness is State of Mind

- Essay on Education

- Essay on Time Management

- Essay on Why Trees are Important in our Life

- 500 Words Essay on Nature in English

- Essay on Smoking is bad for health

- A Short Essay on Mothers Day

- Essay on Health is Wealth

- 71 Idioms with Meaning and Sentences for Daily Use

Similar Posts

Types of Paradox in Literature

Paradox Definition A self-conflicting statement which at first appears to be confusing but later-on it became latent truth. It is often used to make the…

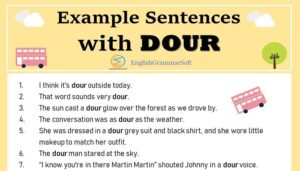

Sentences with Dour (73 Examples)

73 Example Sentences with Dour I think it’s dour outside today. That word sounds very dour. The sun cast a dour glow over the forest…

Examples of Assonance in Literature

Assonance The repetition of vowel sounds in words that are close together is called assonance. The sound doesn’t have to be at the beginning of…

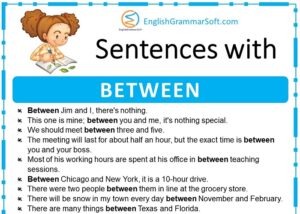

47 Example Sentences with BETWEEN

Sentences with Between Between Jim and I, there’s nothing. This one is mine; between you and me, it’s nothing special. The meeting will last for…

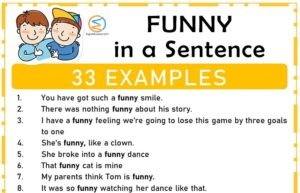

Funny in a Sentence (33 Examples)

Funny in a Sentence You have got such a funny smile. There was nothing funny about his story. I have a funny feeling we’re going to lose this game by three…

Proper Noun Definition and Examples

What you will learn today! Proper Noun Definition How to identify proper nouns? Examples List Exercises Proper Noun Definition Proper noun is a word used…

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Psychology of Personality Development

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Steven Gans, MD is board-certified in psychiatry and is an active supervisor, teacher, and mentor at Massachusetts General Hospital.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/steven-gans-1000-51582b7f23b6462f8713961deb74959f.jpg)

- Key Theories

- Development Tips

Personality development refers to the process of developing, enhancing, and changing one's personality over time. Such development occurs naturally over the course of life, but it can also be modified through intentional efforts.

When we meet new people, it is often their personality that grabs our attention. According to the American Psychological Association, personality refers to the enduring behaviors, traits, emotional patterns, and abilities that make up a person's response to the events of their life.

“Personality is a blend of behavioral and thought patterns that are relatively stable over time, characterizing an individual's traits and attitudes," says Ludovica Colella , a CBT therapist and author of "The Feel Good Journal."

Understanding how personality develops can provide insight into who someone is and their background while also increasing our understanding of what's behind our personality traits and characteristics.

At a Glance

Personality development involves all of the factors that influence how our personalities form and change over time. This can include our genetic background and the environment where we are raised. While personality tends to be pretty stable, it can change over time, especially as people get older.

This article discusses how personality is defined, different theories on how personality forms, and what you can do if you are interested in changing certain aspects of your own personality.

What Is Personality Development?

Personality development refers to the process by which the organized thought and behavior patterns that make up a person's unique personality emerge over time. Many factors influence personality, including genetics and environment , how we were parented , and societal variables.

While personality is relatively stable, Colella notes that it isn't entirely fixed. "People can undergo changes in their attitudes, behaviors, and thought patterns in response to new experiences or personal growth,” she explains.

Perhaps most importantly, the ongoing interaction of all these influences continues to shape personality. Personality involves both inborn traits and the development of cognitive and behavioral patterns that influence how we think and act.

Temperament is a key part of personality that is determined by inherited traits. Character is an aspect of personality influenced by experience and social learning that continues to grow and change throughout life.

Personality development has been a major topic of interest for some of the most prominent thinkers in psychology. Since the inception of psychology as a separate science, researchers have proposed a variety of ideas to explain how and why personality develops.

Theories of Personality Development

Our personalities make us unique, but how does personality develop? What factors play the most important role in the formation of personality? Can personality change?

To answer these questions, many prominent thinkers have developed theories to describe the various steps and stages that occur during the development of personality. The following theories focus on several aspects of personality formation—including those that involve cognitive, social, and moral development.

Freud’s Stages of Psychosexual Development

In his well-known stage theory of psychosexual development , Sigmund Freud suggested that personality develops in stages that are related to specific erogenous zones. These stages are:

- Stage 1 : Oral stage (birth to 1 year)

- Stage 2 : Anal stage (1 to 3 years)

- Stage 3 : Phallic stage (3 to 6 years)

- Stage 4 : Latent period (age 6 to puberty)

- Stage 5 : Genital stage (puberty to death)

Freud also believed that failure to complete these stages would lead to personality problems in adulthood.

In addition to being one of the best-known thinkers in personality development, Sigmund Freud remains one of the most controversial. While he made significant contributions to the field of psychology, some of his more disputed and unproven theories, such as his theory of psychosexual development, have been rejected by modern scientists.

Freud's Structural Model of Personality

Freud not only theorized about how personality developed over the course of childhood, but he also developed a framework for how overall personality is structured.

According to Freud, the basic driving force of personality and behavior is known as the libido . This libidinal energy fuels the three components that make up personality: the id, the ego, and the superego.

- The id is the aspect of personality present at birth. It is the most primal part of the personality and drives people to fulfill their most basic needs and urges.

- The ego is the aspect of personality charged with controlling the urges of the id and forcing it to behave in realistic ways.

- The superego is the final aspect of personality to develop and contains all of the ideals, morals, and values imbued by our parents and culture.

According to Freud, these three elements of personality work together to create complex human behaviors. The superego attempts to make the ego behave according to these ideals. The ego must then moderate between the primal needs of the id, the idealistic standards of the superego, and reality.

Freud's concept of the id, ego, and superego has gained prominence in popular culture, despite a lack of support and considerable skepticism from many researchers.

While Freudian theory is less relevant today than it once was, it can be helpful to learn more about these theories in order to better understand the history of research on personality development.

Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development

Erik Erikson’s eight-stage theory of human development is another well-known theory in psychology. While it builds on Freud’s stages of psychosexual development, Erikson chose to focus on how social relationships impact personality development.

The theory also extends beyond childhood to look at development across the entire lifespan.

Erikson's eight stages are:

- Stage 1 : Trust versus mistrust (birth to 1 year)

- Stage 2 : Autonomy versus shame and doubt (1 to 2 years)

- Stage 3 : Initiative versus guilt (3 to 5 years)

- Stage 4 : Industry versus inferiority (6 to 11 years)

- Stage 5 : Identity versus role confusion (12 to 18 years)

- Stage 6 : Intimacy versus isolation (19 to 40 years)

- Stage 7 : Generativity versus stagnation (41 to 64 years)

- Stage 8 : Integrity versus despair (65 years to death)

At each stage, people face a crisis in which a task must be mastered. Those who successfully complete that stage emerge with a sense of mastery and well-being.

However, Erikson believed that those who do not resolve the crisis at a particular stage may struggle with those skills for the remainder of their lives.

Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development

Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development remains one of the most frequently cited in psychology.

While many aspects of Piaget's theory have not stood the test of time, the central idea remains important today: Children think differently than adults .

According to Piaget, children progress through a series of four stages that are marked by distinctive changes in how they think. And how children think about themselves, others, and the world around them plays an essential role in personality development.

Piaget's four stages are:

- Stage 1 : Sensorimotor stage (birth to 2 years)

- Stage 2 : Preoperational stage (2 to 7 years)

- Stage 3 : Concrete operational stage (7 to 11 years)

- Stage 4 : Formal operational stage (12 years and up)

Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development

Lawrence Kohlberg developed a theory of personality development that focused on the growth of moral thought. Building on a two-stage process proposed by Piaget, Kohlberg expanded the theory to include six different stages:

- Stage 1 : Obedience and punishment

- Stage 2 : Individualism and exchange

- Stage 3 : Developing good interpersonal relationships

- Stage 4 : Maintaining social order

- Stage 5 : Social contract and individual rights

- Stage 6 : Universal principles

These stages are separated by levels. Level one is the pre-conventional level, it includes stages one and two, and takes place from birth to 9 years. Level two is the conventional level, it includes stages three and four, and takes place from age 10 to adolescence. Level three is the post-conventional level, it includes stages five and six, and takes place in adulthood.

Although this theory includes six stages, Kohlberg felt that it was rare for people to progress beyond stage four, stressing that these moral development stages are not correlated with the maturation process.

Kohlberg's theory of moral development has been criticized for several different reasons. One primary criticism is that it does not accommodate different genders and cultures equally. Yet, the theory remains important in our understanding of how personality develops.

Why Personality Theories Matter

While these theories suggest different numbers and types of stages, and different ages for progressing from one stage to the next, they have all influenced what we know today about personality development.

5 Basic Personality Traits

The goal of personality development theories is to explain how we each develop our own unique characteristics and traits. While the list of options could be almost endless, most of these personality traits fall into five basic categories :

- Openness : Level of creativeness and responsiveness to change

- Conscientiousness : Level of organization and attention to detail

- Extraversion : Level of socialness and emotional expressiveness

- Agreeableness : Level of interest in others and cooperativeness

- Neuroticism : Level of emotional stability and moodiness

The "Big 5" is one of the most recognized models of personality and also the most widely used, though some suggest that it isn't comprehensive enough to cover the huge variety of personality traits that one can grow and develop.

Personality Development Tips

Theorists such as Freud believed that personality was largely set in stone fairly early in life. However, we now recognize that personality can change over time.

Research suggests that a person's broad traits are quite stable, but changes do happen, particularly as people age.

On a global level, people spend a lot of money on personal development, with this market bringing in more than $38 billion annually (and expected to grow). If you're interested in making positive changes to your personality, these tips can help:

Identify Your Current Traits

Colella notes that self-awareness and reflection are an essential part of personal growth. She suggests that you can start by learning more about your traits, strengths, and weaknesses.

Reflect on your behaviors and how they impact your life and relationships. This self-awareness lays the foundation for personal growth.

You won't know where to place your efforts if you don't identify the personality traits you need to work on. A personality test can provide an assessment of your current traits. Pick one or two traits to work on that you feel would help you grow as a person and focus on them. You can try our fast and free personality test as a good starting point:

Identify Your Values

Colella also suggests that it is important to identify your core values. You can do this by thinking about the values that are the most important to you. After you do this, you can prioritize your goals and better reflect on how your behaviors and actions align with your goals and values.

Set a Daily Personal Development Goal

Commit to doing at least one thing every day to help develop your personality. This doesn't have to be a big action either. Even baby steps will move you in the right direction.

Keep a Positive Mindset

It is also important to work on forging a growth mindset , Colella explains. This allows you to recognize that personality is not set it stone and can instead evolve over time. "Embrace challenges, learn from failures, and see setbacks as opportunities for growth," Colella says.

Changing yourself can be difficult, especially if you're working on a part of your personality you've had for a long time. Staying positive along the way helps you pay more attention to the pros versus the cons. It also makes the journey more enjoyable for you and everyone around you.

Be Confident

When you have something about yourself that you'd like to change, it can be easy to let your perceived imperfection reduce your confidence. Yet, you can be confident and continue to develop your personality in meaningful ways at the same time, giving you the best of both worlds while pursuing personality development.

Stepping outside your comfort zone can be challenging, Colella notes, but slowly expanding your horizons can lead to gradual growth. "Expanding your comfort zone involves taking small, manageable steps, gradually pushing your limits at a pace that feels comfortable for you," she explains.

American Psychological Association. Personality .

Bhoite S, Shinde L. An overview of personality development . Int J Sci Res Develop . 2019:138-141. doi:10.31142/ijtsrd23085

Rettew DC, McKee L. Temperament and its role in developmental psychopathology . Harv Rev Psychiatry . 2005;13(1):14-27. doi:10.1080/10673220590923146

Person ES. As the wheel turns: a centennial reflection on Freud's Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality . J Am Psychoanal Assoc . 2005;53(4):1257-1282. doi:10.1177/00030651050530041201

Giacolini T, Sabatello U. Psychoanalysis and affective neuroscience. The motivational/emotional system of aggression in human relations . Front Psychol . 2019;9:2475. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02475

Kupfersmid J. Freud's clinical theories then and now . Psychodynam Psychiat . 2019;47(1). doi:10.1521/pdps.2019.47.1.81

Orenstein GA, Lewis L. Erikson's Stages of Psychosocial Development . In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

Gross Y. Erikson's stages of psychosocial development . Wiley Encyclop Personal Individ Diff: Models Theor . 2020. doi:10.1002/9781118970843.ch31

Babakr Z, Mohamedamin P, Kakamad K. Piaget's cognitive developmental theory: Critical review . Educ Quart Rev . 2019;2(3):517-24. doi:10.31014/aior.1993.02.03.84

Baldwin J. Kohlberg's stages of moral development and criticisms . J Eur Acad Res. 2016;6(1):26-35.

DeTienne KB, Ellertson CF, Ingerson MC, Dudley WR. Moral development in business ethics: An examination and critique . J Bus Ethics . 2021;170:429-448. doi:10.1007/s10551-019-04351-0

Power RA, Pluess M. Heritability estimates of the Big Five personality traits based on common genetic variants . Translation Psychiatry . 2015;5:e604. doi:10.1038/tp.2015.96

Feher A, Vernon P. Looking beyond the Big Five: A selective review of alternatives to the Big Five model of personality . Personal Indiv Diff . 2021;169:110002. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2020.11.0002

Damian RI, Spengler M, Sutu A, Roberts BW. Sixteen going on sixty-six: A longitudinal study of personality stability and change across 50 years . Journal of Personality and Social Psychology . 2019;117(3):674-695. doi:10.1037/pspp0000210

Grand View Research. Personal development market size, share & trade analysis report by instrument (books, e-platforms, personal coaching/training, workshops), by focus area, by region, and segment forecasts, 2020 - 2027 .

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

Personality and Developmental Characteristics of Primary School Students ’ Personality Types

Associated data.

The datasets for this manuscript are not publicly available because the topic is not finished. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to corresponding author.

The aim of the current study was to investigate the personality characteristics and developmental characteristics of primary school students’ personality types in a cross-sectional sample of 10,366 Chinese children. The Personality Inventory for Primary School Student was used to evaluate primary school students’ personality. Latent profile analysis (LPA) was used to classify primary school students’ personality types. One-way ANOVA was used to explore the personality characteristics of personality types, and Chi-square tests were used to investigate grade and gender differences of primary school students’ personality types. Results showed that the primary school students could be divided into three personality types: the resilient, the overcontrolled, and the undercontrolled. Resilients had the highest scores, and undercontrollers had the lowest scores on all of five personality dimensions (intelligence, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and emotional stability). The overcontrollers’ scores on personality were between the other two types, with lower emotional stability. As the grade level increased, the proportion of undercontrolled students in primary schools generally showed an upward trend and reached the maximum in grade 5. The proportion of resilient students in primary schools generally showed a downward trend. The proportion of resilient students was highest in grade 2 and lowest in grade 5. Girls were significantly more likely than boys to be resilient personality types, while boys were significantly more likely than girls to be undercontrolled personality types. The overcontrolled personality type did not show significant gender differences. Because of the undesirable internalizing problems related to overcontrollers and the externalizing problems related to undercontrollers, our results have implications for Chinese schools, families, and society in general.

Introduction

Personality has significant impacts on many aspects of people’s everyday lives, such as interpersonal relationships, health, academic performance, and subjective wellbeing ( Neyer et al., 2014 ; Briki, 2018 ; Gray and Pinchot, 2018 ; Stajkovic et al., 2018 ). The primary school stage is an important developmental period for accumulating knowledge and learning to understand society. It is also an important stage for children’s personality development ( Soto and Tackett, 2015 ). Previous research has shown that personality development in primary school can effectively predict crime in adulthood ( Kachaeva et al., 2017 ). In studies of personality development, two main strategies a variable-centered and a person-centered approach are being distinguished ( Donnellan and Robins, 2010 ).

Variable-centered approaches are primarily reflected in studies on personality dimensions or traits, such as the dimensions of the five-factor model (FFM) of personality, the most widely employed model ( Bergman and Magnusson, 1997 ; John et al., 2008 ). The FFM yields five personality dimensions: agreeableness, extraversion, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and openness. Personality is the psychological properties with culture attribute ( Li and Zhang, 2006 ; Zhang, 2011 ). Based on Chinese culture and the characteristics of children’s personalities, Yang (2014) used teachers’ free description and vocabulary to collect and code personality trait adjectives for primary school students in China. They decided that the personality construction of Chinese primary school students was composed of five dimensions: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and intelligence. Intelligence refers to the characteristics of individual self-awareness, intelligence, and talents, reflecting whether primary school students have their own independent ideas, high learning ability, and positive motivation in learning activities. Teachers’ assessment of intelligence was reflected in three aspects (intelligent, curiosity/creativity, and independent/enterprising). Western countries named the traits related to intelligence as openness. In addition to emphasizing the speed of brain reaction, it also emphasized appreciation of personal emotion, imagination, and the pursuit of a better life, beliefs, and values ( Carver and Scheier, 1996 ). In China, this dimension mainly reflects the speed of children’s brain reaction. This dimension also includes children’s independence and enterprising spirit ( Zhang, 2011 ). The dimension named as intelligence is more in line with Chinese educational philosophy. Cultural differences lead to differences in the connotations of personality traits involving intelligence.

Person-centered approaches study “types” identifying clusters of individuals with similar personality patterns ( Van Leeuwen et al., 2004 ). Person-centered approaches are concerned with how different dimensions are organized within the individual, which subsequently defines different types of person ( Herzberg and Roth, 2006 ). The typological approach emphasizes persons ( Hart et al., 2003 ). Personality types are intended specifically to represent the organization among traits that occurs within individuals ( Grumm and Collani, 2009 ). According to the results of several studies, the five personality traits in FFM can be combined with each other to form three personality types, resilient, undercontrolled, and overcontrolled ( Robins et al., 1996 ; Asendorpf and Van Aken, 1999 ; Asendorpf et al., 2001 ; Yang and Ma, 2014 ; Rosenström and Jokela, 2017 ). These three personality types have been repeatedly verified across different languages and cultures, different personality models, and different ages ( Donnellan and Robins, 2010 ; Chapman and Goldberg, 2011 ; Meeus et al., 2011 ; Alessandri et al., 2014 ; Leikas and Salmela-Aro, 2014 ; Specht et al., 2014 ; Yang and Ma, 2014 ). Previous research described the three personality types in terms of the FFM of personality description. Resilients were characterized by relatively high levels of openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, emotional stability, and agreeableness. Overcontrollers were characterized by low emotional stability, with moderate levels of the other four dimensions. Undercontrollers were characterized by relatively low levels of openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, emotional stability, and agreeableness ( Grumm and Collani, 2009 ; Zentner and Shiner, 2012 ; Yang and Ma, 2014 ; Chen, 2019 ; Zou et al., 2019 ). The resilient personality type is well adapted to society, verbally expressive, energetic, independent, self-confident, and able to adjust to situational demands using self-control. The overcontrolled personality type is socially maladaptive, emotionally brittle, interpersonally sensitive, tense, and inhibited prone to excessively restraining impulses. The undercontrolled personality type is socially maladaptive, impulsive, self-centered, manipulative, confrontational, disagreeable, and lacking in self-control ( Block and Block, 1980 ; Robins et al., 1996 ; Donnellan and Robins, 2010 ).

The identification of groups of persons is frequently done through cluster analysis (e.g., Magnusson and Bergman, 1990 ) or Q factor analysis (e.g., York and John, 1992 ). The goal of these analytic techniques is to maximize similarity among members of a group while minimizing resemblance of members of one group to members of all the others. These approaches have methodological limitations ( Klimstra et al., 2010 ). The number of types determined by these analytic techniques has the subjective judgment and theoretical orientation of the investigators. Moreover, the number of groups that is specified has implications for statistical analysis: If many groups are specified, then there may be few participants in each group, which makes parametric data analysis difficult. On the other hand, the formation of only a few groups may mean that participants have only limited resemblance to other participants in the same group, and consequently, viewing this group as representing a type of person can be misleading. There are no easy resolutions of this problem, which has led to calls for the development of new analytic techniques for person-centered research ( Singer and Ryff, 2001 ). LPA is an empirically driven method that defines taxonomies or classes of people based on common characteristics ( Lanza et al., 2003 ). LPA uses all observations of the continuous dependent variable to define these classes via maximum likelihood estimation ( Little and Rubin, 1987 ). Some studies point out that LPA is better than traditional Q factor analysis and cluster analysis ( Reinke et al., 2008 ). It not only eliminates the measurement errors in the construct, but also provides the researcher with more objective indices of fit to make up for the deficiencies of Q factor analysis and cluster analysis ( Bauer and Curran, 2004 ). Meeus et al. (2011) used LPA to divide adolescents into three personality types: the resilient, the overcontrolled, and the undercontrolled. This study found that as the age increased, the number of overcontrollers and undercontrollers decreased, whereas the number of resilients increased. Undercontrollers, in particular, were found to peak in early to middle adolescence. Asendorpf and van Aken (1999) classified the personality types of children from 4 to 10 years old, and found that more girls were rated as the resilient type than boys, and less girls were rated as the undercontrolled type than boys. However, in the context of Chinese culture, there are few studies on the personality characteristics and developmental characteristics of primary school students’ personality types.

Asendorpf and van Aken (1999) found that childhood personality types are good predictors of later development. Adjustment problems differ by personality type, which indicates the utility of conceptualizing students’ personalities in terms of types for both research and clinical practice ( Shiner and Caspi, 2003 ). Overcontrolled children may be especially at risk of developing internalizing problems (e.g., symptoms of depression and anxiety) due to their inhibited nature, whereas undercontrollers’ impulsivity may leave them vulnerable to the development of externalizing problems (e.g., aggression and attention problems; Yu et al., 2015 ; Achenbach et al., 2016 ; Bohane et al., 2017 ). Robins et al. (1996) found that undercontrollers had lower IQ scores, lower academic achievement at school, worse conduct, and more serious delinquency than overcontrollers and resilients. Focusing on personality types allows us to discern predictable patterns of risks to healthy development, helping teachers and parents educate children and intervene when necessary. Teachers and parents are more likely to prevent child maladaptive development based on developmental characteristics. Our research lays the foundation for psychologists to conduct future intervention research.

The current study aimed to investigate the personality characteristics of Chinese primary school students’ personality types and their developmental characteristics by grade and gender. Based on previous research, we hypothesized that (1) the primary school students would be divided into three personality types: the resilient, the overcontrolled, and the undercontrolled; (2) compared to the other two types, undercontrollers’ scores would be lower and resilients’ would be higher on all five personality dimensions (intelligence, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and emotional stability), with the overcontrollers’ scores in between, with lower emotional stability; and (3) there would be significant grade and gender differences in primary school students’ personality types.

Materials and Methods

Participants and procedures.

We selected 21 primary schools in North China to issue the questionnaire. The questionnaire was used to evaluate primary school students by teachers. There were several classes for each grade and two teachers in each class. We took a multi-informant approach to reduce reporter bias in measurement of personality. Each student was assessed by two teachers; 636 teachers rated 10,366 primary school students (5,441 male and 4,925 female). There were 2,209 first graders, with an average age of 6.92 years old, 2,066 second graders, average age 8.06 years old, 2,218 third graders, average age 9.41 years old, 1,886 fourth graders, average age 10.03 years old, and 2,087 fifth graders, average age 11.24 years old. Written informed consent had been obtained from the parents’ guardians of all participants. All participants volunteered to join the experiments, and informed consents signed by their legal guardians.

Personality Inventory for Primary School Student

Teachers rated their students’ personality on the Personality Inventory for Primary School Student ( Zhang, 2011 ). The personality was measured using Zhang’s Chinese FFM, which was developed based on the original FFM. This personality inventory includes five dimensions, namely, extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, emotional stability, and intelligence. This inventory includes 62 items. All items were rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (very inaccurate) to 5 (very accurate). Emotional stability is an inverted dimension. Items rated as 1 point are converted into 5 points, and items rated as 2 points are converted into 4 points. For example, when criticized by the teacher, the student will immediately become angry or frustrated. This item is a reverse scoring. After reverse scoring, the total score of each personality dimension is calculated. The higher the score, the higher the development level of the personality dimension. This questionnaire has good reliability and validity in the Chinese cultural context ( Zhang, 2011 ). In order to investigate the degree of consistency of the teacher’s evaluations, we had two teachers in each class fill out the personality rating scale on all primary school students in the class at the same time. The rater reliability and the Cronbach’s alphas of scale are presented in Table 1 . The consistency of the two raters’ evaluations of primary school students indicated that the evaluation results were objective and credible.

The rater reliability and the Cronbach’s alphas of the scale.

Data Analysis

The SPSS 20.0 was used to conduct descriptive statistics and analysis of variance. Specifically, One-way ANOVA was used to explore the personality characteristics of personality types, and Chi-square tests were used to investigate the grade and gender differences of primary school students’ personality types. The Mplus 7.4 was used to conduct LPA. All data were treated with a statistical significance level of p < 0.05. LPA was executed to analyze primary school students’ personality types ( Muthén and Muthén, 2000 ). We chose the optimal model relying on the following criteria: Akaïke Information Criterion (AIC), Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), Sample-Size Adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (aBIC), Likelihood Ratio Tests (LMR), Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT), and Entropy ( Nylund et al., 2007 ). Smaller values of AIC, BIC, and aBIC indicate better models ( Schwarz, 1978 ). The range of entropy is between 0.00 and 1.00. Higher values of entropy indicate higher the classification accuracy ( Hix-Small et al., 2004 ). For the LMR and BLRT, a value of p smaller than 0.05 suggests that the k class model is better than the k-1 class model ( Asparouhov and Muthén, 2012 ). If some types in a k class model already appear in a k-1 class model, the k-1 class model will be selected according to the principle of model simplicity ( Muthén and Muthén, 2000 ). In order to make the model more universal, Fisher and Robie (2019) pointed out that the large sample size should be randomly divided into two small samples, and LPA should be done separately. The SPSS 20.0 was used to randomly split a large sample size into two small subsamples. One subsample was used for exploratory LPA. Another subsample was used for cross-validation.

Personality Characteristics of Primary School Students’ Personality Types

A total of 10,366 participants were randomly divided into two samples. Sample 1 ( n 1 = 5,183) and sample 2 ( n 2 = 5,183) were used for LPA, respectively. The results showed that the potential category classifications of the two samples were similar (see Table 2 ). AIC, BIC, and adjusted BIC of the three-class model and four-class model were smaller than other models, the entropy values were all above 0.8, and the value of p for LMR and BLRT was both significant, which indicates that these two models fit well and the correct rate of personality type classification is higher than other models. Wang and Bi (2018) pointed out that the final model should be determined in conjunction with the actual meaning of classification. In the four-class model, the characteristics of the two types in the middle overlap and should be regarded as one type. In other words, the personality characteristics of these two types were very similar (see Figure 1 ). According to the principle of model simplicity, the three-class model should be the optimal model. In addition, the four-class model did not meet the condition that each type accounts for at least 5% of the total sample ( Nagin, 2005 ). The three-class model has clearer and more concise outlines, and the indicators also meet the criteria for suitability of LPA. LPA diagrams of the two samples are presented in Figures 2 , ,3. 3 . The results showed that the three-class model was the best model. It is reasonable to divide the personality of primary school students into three classes. This result is consistent with the number of types classified by Ma (2016) .

Latent profile analysis fitting index of personality dimension of primary school students ( n = 10,366).

Potential profile of the four-class model ( n 1 = 5,183).

Potential profile of the three-class model ( n 1 = 5183).

Potential profile of the three-class model ( n 2 = 5,183).

One-way ANOVA and multiple comparisons were used to describe the characteristics of each personality type (see Table 3 ). The third personality type had the highest scores on all five dimensions (intelligence, conscientiousness, extraversion, emotional stability, and agreeableness). According to Robins et al. (1996) , we identified this type as the resilient personality type. The score of the second type on personality was between the other two types, with lower emotional stability. According to Zentner and Shiner (2012) , we identified this type as the overcontrolled personality type. The first personality type had the lowest scores on all five dimensions. According to Ma (2016) , we identified this type as the undercontrolled personality type.

Descriptive statistics, analysis of variance, and post-hoc tests on personality types in five dimensions.

<, significantly lower; =, no significant difference; and >, significantly higher .

** p < 0.01; * p < 0.05.

Developmental Characteristics of Primary School Students’ Personality Types

In order to investigate the grade and gender differences in primary school students’ personality types, we first confirmed that the personality types were related to gender and grade (see Table 4 ). Results showed that personality types were indeed related to both grade ( χ 2 (8) = 217.016 ** , Φ = 0.102) and gender ( χ 2 (2) = 141.368 ** , Φ = 0.117). Since the interaction effects between grade and gender had no significant influence on personality type, we only examined the relationship between gender and personality type, and the relationship between grade and personality type. The second step was to examine the developmental characteristics of primary school students’ personality types in different grades. The population proportions presented in Figure 4 show the grade-related developmental trajectory of primary school students’ personality types. Chi-square tests were used to examine grade differences. Finally, a Chi-square test was conducted to examine gender differences.

The number and ratio of each type of personality in each grade and gender.

Developmental trends of primary school students’ personality types.

Results showed that among the undercontrolled primary school students, there were significant differences between different grades ( χ 2 (4) = 99.413 ** , Φ = 0.098). The proportion of students in grade 1 was significantly lower than grade 2 ( χ 2 (1) = 22.091 ** , Φ = 0.072), grade 3 ( χ 2 (1) = 17.888 ** , Φ = 0.064), grade 4 ( χ 2 (1) = 34.738 ** , Φ = 0.092), and grade 5 ( χ 2 (1) = 96.101 ** , Φ = 0.150). There was no significant difference in the proportion between grade 2 and grade 3 ( χ 2 (1) = 0.241, Φ = 0.008). There was no significant difference in the proportion between grade 2 and grade 4 ( χ 2 (1) = 1.629, Φ = 0.020). The proportion of students in grade 2 was significantly lower than that in grade 5 ( χ 2 (1) = 25.400 ** , Φ = 0.078). The proportion of students in grade 3 was significantly lower than grade 4 ( χ 2 (1) = 3.113 △ , Φ = 0.028) and grade 5 ( χ 2 (1) = 30.953 ** , Φ = 0.086). The proportion of students in grade 4 was significantly lower than grade 5 ( χ 2 (1) = 13.290 ** , Φ = 0.058). This result showed that as the grade level increased, the proportion of undercontrolled students in primary schools generally showed an upward trend. Specifically, this type showed an upward trend from grade 1 to grade 2, a flat trend from grade 2 to grade 3, and an upward trend from grade 3 to grade 5. The proportion of boys in the undercontrolled primary school students was significantly higher than that of the girls ( χ 2 (1) = 108.128 ** , Φ = 0.102). Our results revealed a significant gender difference in the undercontrolled primary school students.

Among the overcontrolled primary school students, there were significant differences between different grades ( χ 2 (4) = 82.138 ** , Φ = 0.089). The proportion of students in grade 1 was significantly higher than grade 2 ( χ 2 (1) = 38.600 ** , Φ = 0.095), grade 4 ( χ 2 (1) = 8.321 * , Φ = 0.045), and grade 5 ( χ 2 (1) = 4.860 * , Φ = 0.034). The proportion of students in grade 1 was significantly lower than grade 3 ( χ 2 (1) = 5.960 * , Φ = 0.037). The proportion of students in grade 2 was significantly lower than grade 3 ( χ 2 (1) = 72.867 ** , Φ = 0.132), grade 4 ( χ 2 (1) = 9.870 * , Φ = 0.050), and grade 5 ( χ 2 (1) = 15.746 ** , Φ = 0.062). The proportion of students in grade 3 was significantly higher than grade 4 ( χ 2 (1) = 27.003 ** , Φ = 0.082) and grade 5 ( χ 2 (1) = 21.032 ** , Φ = 0.071). There was no significant difference in the proportion between grade 4 and grade 5 ( χ 2 (1) = 0.533, Φ = 0.012). This result showed that the proportion of overcontrolled students was highest in grade 3 and lowest in grade 2. There was no significant difference in the proportion of boys and girls ( χ 2 (1) = 0.907, Φ = 0.010).

Among the resilient primary school students, there were significant differences between different grades ( χ 2 (4) = 138.021 ** , Φ = 0.115). The proportion of students in grade 1 was significantly lower than grade 2 ( χ 2 (1) = 4.975 * , Φ = 0.034). The proportion of students in grade 1 was significantly higher than grade 3 ( χ 2 (1) = 46.181 ** , Φ = 0.103), grade 4 ( χ 2 (1) = 5.947 * , Φ = 0.038), and grade 5 ( χ 2 (1) = 55.306 ** , Φ = 0.114). The proportion of students in grade 2 was significantly higher than grade 3 ( χ 2 (1) = 78.852 ** , Φ = 0.137), grade 4 ( χ 2 (1) = 20.578 ** , Φ = 0.072), and grade 5 ( χ 2 (1) = 90.245 ** , Φ = 0.147). The proportion of students in grade 3 was significantly lower than grade 4 ( χ 2 (1) = 17.140 ** , Φ = 0.065). There was no significant difference in the proportion between grade 3 and grade 5 ( χ 2 (1) = 0.452, Φ = 0.010). The proportion of students in grade 4 was significantly higher than grade 5 ( χ 2 (1) = 22.820 ** , Φ = 0.076). This result showed that as the grade level increased, the proportion of resilient students in primary schools generally showed a downward trend. The proportion of resilient students was highest in grade 2 and lowest in grade 5. The result showed that the proportion of resilient primary school boys was significantly lower than that of the girls ( χ 2 (1) = 87.235 ** , Φ = 0.092). There was a significant gender difference in resilient primary school students.

Classification and Personality Characteristics of Students’ Personality Types

We divided the primary school students into three personality types using LPA. The types, resilient, overcontrolled, and undercontrolled, were consistent with previous research results ( Donnellan and Robins, 2010 ; Meeus et al., 2011 ; Rosenström and Jokela, 2017 ). We used five personality dimensions as outcome variables and type as grouping variable to do a one-way analysis of variance; resilients had the highest scores, undercontrollers had the lowest scores on all of the five personality dimensions, and overcontrollers’ scores were between the other two types, with lower emotional stability, consistent with previous research results ( Zentner and Shiner, 2012 ; Chen, 2019 ; Zou et al., 2019 ). The overcontrolled type represented the majority of the total sample. This finding was similar to the results of research by Ma (2016) , who also found that the overcontrolled group accounted for the majority in China. This may reflect the limitations of Chinese social norms ( Xie et al., 2016 ). Chang et al. (2011) considered students in China to be rule-abiding in their behavior patterns and encouraged to be compliant by Chinese teachers, which reflects the high requirements and expectations of self-control for students in China’s primary education system on the whole. This would explain why most Chinese students would fall in the overcontrolled group. The overcontrolled children were described by teachers as prosocial, well-liked by children and adults, and obedient and not as aggressive, self-assertive, and competitive. Resilients scored high on all five dimensions. The resilient children were described by self-confidence, independence, verbal fluency, and an ability to concentrate on tasks ( Robins et al., 1996 ). Chinese teachers do not have a positive attitude toward all these characteristics. Compared with independent thinkers, teachers actually prefer overcontrolled students. Therefore, the teacher’s assessment of students may have observer bias. In our study, we took a multi-informant approach to reduce reporter bias in measurement of personality. Undercontrollers scored low on all five dimensions. The undercontrolled children were described by impulsivity, disobedience, stubbornness, and physical activity ( Robins et al., 1996 ). Some of these characteristics might be considered advantages in the United States (e.g., being stubborn, physically active, uninhibited, and disobedient).

Developmental Characteristics of Students’ Personality Types

We found that as the grade level increased, the proportion of undercontrolled students in primary schools generally showed an upward trend. Specifically, this type showed an upward trend from grade 1 to grade 2, a flat trend from grade 2 to grade 3, and an upward trend from grade 3 to grade 5. The proportion of resilient students in primary schools generally showed a downward trend. The proportion of resilient students was highest in grade 2 and lowest in grade 5. In the whole primary school stage, overcontrolled students always made up the majority. Individual physical and mental development and the learning atmosphere change as children progress through the grades, and those changes are reflected in the gradual decrease in the scores of certain personality dimensions ( Galambos and Costigan, 2003 ). This is especially true for the non-adaptive undercontrolled primary school students. At the beginning of formal nine-year compulsory education, primary school students are in a transition period; they have not yet adapted to the changes in the learning environment, so their extraversion, openness, and emotional stability are on a downward trend ( Soto et al., 2011 ; Van den Akker et al., 2014 ). The results of our study imply that middle-grade pupils have basically adapted to school, and most of their personality dimensions reflect a period of steady development ( Yang et al., 2016 ). Therefore, the proportion of undercontrolled primary school students is relatively stable in the third and fourth grades. The proportion of undercontrolled primary school students increases rapidly after fourth grade, however. Entering the upper grades, primary school students not only face increased learning pressure, restrained creativity, reduced activity time, and decreased activity levels, but also physical and psychological changes. These changes are reflected in the declining trend of agreeableness, intelligence, extraversion, and conscientiousness ( Van den Akker et al., 2010 , 2014 ; Soto et al., 2011 ). This leads to an increase in the proportion of undercontrolled students and a decrease in the proportion of resilient students. At this age, resilient students are more likely to become undercontrolled or overcontrolled ( Chen, 2019 ).

The proportion of girls with the resilient personality type was significantly higher than that of boys; conversely, the proportion of boys with the undercontrolled personality type was significantly higher than that of girls. The overcontrolled personality type did not show significant gender differences. The gender difference in primary school students’ personality types is consistent with the results of previous studies ( Asendorpf and Van Aken, 1999 ). Gender differences in personality are either due to physical differences or due to gender socialization in childhood ( Van den Akker et al., 2014 ). Chinese social culture gives different behaviors and attitudes suitable for boys and girls. In the process of Chinese gender role socialization, girls are expected to show the gentleness, dignity, and virtue of a “lady” who adapts to the environment and exhibits self-control. Boys are expected to be “brave” and “fearless” and are encouraged to show impulsiveness, seek stimulus, and otherwise exhibit poor inhibition. Physiologically, girls secrete fewer male hormones than boys and then adopt more mature self-regulation methods when coping with stressful events. They usually show less impulsive and aggressive behaviors. Therefore, boys who cannot effectively restrain impulses and adapt to the environment are more inclined to become undercontrolled primary school students.

Primary school students could be divided into three personality types: the resilient, the overcontrolled, and the undercontrolled. Resilients had the highest scores, and undercontrollers had the lowest scores on all of five personality dimensions. The overcontrollers’ scores on personality were between the other two types, with lower emotional stability. As the grade level increased, the proportion of undercontrolled students in primary schools generally showed an upward trend and reached the maximum in grade 5. The proportion of resilient students in primary schools generally showed a downward trend. The proportion of resilient students was highest in grade 2 and lowest in grade 5. The proportion of girls with the resilient personality type was significantly higher than that of boys; conversely, the proportion of boys with the undercontrolled personality type was significantly higher than that of girls. The overcontrolled personality type did not show significant gender differences.

Data Availability Statement

Ethics statement.

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Jilin University Ethics Committee. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants’ legal guardian.

Author Contributions

YY designed the experiment, prepared the materials, and performed the experiment. YY and YZ analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Funding. This study was sponsored and funded by the Humanities and Social Science Foundation of China, State Education Ministry (Grant No. 20YJC190029).

- Achenbach T. M., Ivanova M. Y., Rescorla L. A., Turner L. V., Althoff R. R. (2016). Internalizing/externalizing problems: review and recommendations for clinical and research applications . J. Am. Acad. Child Psy. 55 , 647–656. 10.1016/j.jaac.2016.05.012, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alessandri G., Vecchione M., Donnellan B. M., Eisenberg N., Caprara G. V., Cieciuch J. (2014). On the cross-cultural replicability of the resilient, undercontrolled, and overcontrolled personality types . J. Pers. 82 , 340–353. 10.1111/jopy.12065, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Asendorpf J. B., Borkenau P., Ostendorf F., Aken M. A. G. V. (2001). Carving personality description at its joints: confirmation of three replicable personality prototypes for both children and adults . Eur. J. Pers. 15 , 169–198. 10.1002/per.408 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Asendorpf J. B., Van Aken M. A. (1999). Resilient, overcontrolled, and undercontroleed personality prototypes in childhood: replicability, predictive power, and the trait-type issue . J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 77 , 815–832. 10.1037/0022-3514.77.4.815, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Asparouhov T., Muthén B. (2012). Using Mplus TECH11 and TECH14 to test the number of latent classes . Mplus Web Notes 14 , 17–22. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bauer D. J., Curran P. J. (2004). The integration of continuous and discrete latent variable models: potential problems and promising opportunities . Psychol. Methods 9 , 3–29. 10.1037/1082-989X.9.1.3, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bergman L. R., Magnusson D. (1997). A person-oriented approach in research on developmental psychopathology . Dev. Psychopathol. 9 , 291–319. 10.1017/S095457949700206X, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Block J. H., Block J. (1980). “ The role of ego-control and ego-resiliency in the organization of behavior ,” in Minnesota Symposium on Child Psychology. ed. Collins W. A., Vol . 13 (Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; ), 39–101. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bohane L., Maguire N., Richardson T. (2017). Resilients, overcontrollers and undercontrollers: a systematic review of the utility of a personality typology method in understanding adult mental health problems . Clin. Psychol. Rev. 57 , 75–92. 10.1016/j.cpr.2017.07.005, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Briki W. (2018). Trait self-control: why people with a higher approach (avoidance) temperament can experience higher (lower) subjective wellbeing . Pers. Indiv. Differ. 120 , 112–117. 10.1016/j.paid.2017.08.039 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Carver C. S., Scheier M. F. (1996). Perspective on Personality. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. [ Google Scholar ]

- Chang L., Mak M. C. K., Li T., Wu B. P., Chen B. B., Lu H. J. (2011). Cultural adaptations to environmental variability an evolutionary account of east-west differences . Educ. Psychol. Rev. 23 , 99–129. 10.1007/s10648-010-9149-0 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chapman B. P., Goldberg L. R. (2011). Replicability and 40-year predictive power of childhood ARC types . J. Clin. Child Adolesc. 101 , 593–606. 10.1037/a0024289, PMID: [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chen J. H. (2019). Personlaity Types in Junior High School Students:Development and Interpersonal Relationships’ Influence and Intervention-Based on Longitudinal Research Design. China: Liaoning Normal University. [ Google Scholar ]

- Donnellan M. B., Robins R. W. (2010). Resilient, overcontrolled, and undercontrolled personality types: issues and controversies . Soc. Personal. Psychol. Compass 4 , 1070–1083. 10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00313.x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fisher P. A., Robie C. (2019). A latent profile analysis of the five factor model of personality: a constructive replication and extension . Pers. Indiv. Differ. 139 , 343–348. 10.1016/j.paid.2018.12.002 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Galambos N. L., Costigan C. L. (2003). Emotional and Personality Development in Adolescence. United States: JE. A, Inc. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gray J. S., Pinchot J. J. (2018). Predicting health from self and partner personality . Pers. Indiv. Differ. 121 , 48–51. 10.1016/j.paid.2017.09.019 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Grumm M., Collani G. V. (2009). Personality types and self-reported aggressiveness . Pers. Indiv. Differ. 47 , 845–850. 10.1016/j.paid.2009.07.001 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hart D., Atkins R., Fegley S. (2003). Personality and development in childhood: a person-centered approach . Monogr. Soc. Res. Child 68 , 1–109. 10.1111/1540-5834.00231 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Herzberg P. Y., Roth M. (2006). Beyond resilients, undercontrollers, and overcontrollers? An extension of personality prototype research . Eur. J. Pers. 20 , 5–28. 10.1002/per.557 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hix-Small H., Duncan T. E., Duncan S. C., Okut H. (2004). A multivariate associative finite growth mixture modeling approach examining adolescent alcohol and marijuana use . J. Psychopathol. Behav. Assess. 26 , 255–270. 10.1023/B:JOBA.0000045341.56296.fa [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- John O. P., Naumann L. P., Soto C. J. (2008). “ Paradigm shift to the integrative big-five trait taxonomy: history, measurement, and conceptual issues ,” in Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, Vol . 3 . eds. John O. P., Robins R. W., Pervin L. A. (New York: Guilford Press; ), 114–153. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kachaeva M., Shport S., Nuckova E., Afzaletdinova D., Satianova L. (2017). A study of the impact of child and adolescent abuse on personality disorders in adult women . Eur. Psychiatry 41 :S587. 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.891 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Klimstra T. A., Hale W. W., III, Raaijmakers Q. A., Branje S. J., Meeus W. H. (2010). A developmental typology of adolescent personality . Eur. J. Pers. 24 , 309–323. 10.1002/per.744 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lanza S. T., Flaherty B. P., Collins L. M. (2003). “ Latent class and latent transition analysis ,” in Handbook of Psychology: Research Methods in Psychology. eds. Schinka J. A., Velicer W. A. (New York: Wiley; ), 663–685. [ Google Scholar ]

- Leikas S., Salmela-Aro K. (2014). Personality types during transition to young adulthood: how are they related to life situation and well-being? J. Adolesc. 37 , 753–762. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.01.003, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Li Y. H., Zhang J. X. (2006). A cross-cultural study on the personality of 7–10 years-old children between Greece and China . Chin. J. Clin. Psychol. 14 , 331–333. 10.1016/S0379-4172(06)60092-9 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Little R. J., Rubin D. B. (1987). Statistical Analysis With Missing Data. New York: Wiley. [ Google Scholar ]

- Ma S. C. (2016). Personality Characteristics of Children and Adolescents in China–National Norm Formulation, Equivalent Inter-Phase Development Characteristics and Personality Types. China: Liaoning Normal University. [ Google Scholar ]

- Magnusson D., Bergman L. R. (1990). “ A pattern approach to the study of pathways from childhood to adulthood ,” in Straight and Devious Pathways From Childhood to Adulthood. eds. Robins L. N., Rutter M. (New York: Cambridge University Press; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Meeus W., Van de Schoot R., Klimstra T., Branje S. (2011). Personality types in adolescence: change and stability and links with adjustment and relationships: a five-wave longitudinal study . Dev. Psychol. 47 , 1181–1195. 10.1037/a0023816, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Muthén B., Muthén L. K. (2000). Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes . Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 24 , 882–891. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb02070.x, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nagin D. S. (2005). Group-Based Modeling of Development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Neyer F. J., Mund M., Zimmermann J., Wrzus C. (2014). Personality-relationship transactions revisited . J. Pers. 82 , 539–550. 10.1111/jopy.12063, PMID: [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nylund K. L., Asparouhov T., Muth N. B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: a Monte Carlo simulation study . Struct. Equ. Model. 14 , 535–569. 10.1080/10705510701575396 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Reinke W. M., Herman K. C., Petras H., Ialongo N. S. (2008). Empirically derived subtypes of child academic and behavior problems: co-occurrence and distal outcomes . J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 36 , 759–770. 10.1007/s10802-007-9208-2, PMID: [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]