- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- How to prepare and...

How to prepare and deliver an effective oral presentation

- Related content

- Peer review

- Lucia Hartigan , registrar 1 ,

- Fionnuala Mone , fellow in maternal fetal medicine 1 ,

- Mary Higgins , consultant obstetrician 2

- 1 National Maternity Hospital, Dublin, Ireland

- 2 National Maternity Hospital, Dublin; Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Medicine and Medical Sciences, University College Dublin

- luciahartigan{at}hotmail.com

The success of an oral presentation lies in the speaker’s ability to transmit information to the audience. Lucia Hartigan and colleagues describe what they have learnt about delivering an effective scientific oral presentation from their own experiences, and their mistakes

The objective of an oral presentation is to portray large amounts of often complex information in a clear, bite sized fashion. Although some of the success lies in the content, the rest lies in the speaker’s skills in transmitting the information to the audience. 1

Preparation

It is important to be as well prepared as possible. Look at the venue in person, and find out the time allowed for your presentation and for questions, and the size of the audience and their backgrounds, which will allow the presentation to be pitched at the appropriate level.

See what the ambience and temperature are like and check that the format of your presentation is compatible with the available computer. This is particularly important when embedding videos. Before you begin, look at the video on stand-by and make sure the lights are dimmed and the speakers are functioning.

For visual aids, Microsoft PowerPoint or Apple Mac Keynote programmes are usual, although Prezi is increasing in popularity. Save the presentation on a USB stick, with email or cloud storage backup to avoid last minute disasters.

When preparing the presentation, start with an opening slide containing the title of the study, your name, and the date. Begin by addressing and thanking the audience and the organisation that has invited you to speak. Typically, the format includes background, study aims, methodology, results, strengths and weaknesses of the study, and conclusions.

If the study takes a lecturing format, consider including “any questions?” on a slide before you conclude, which will allow the audience to remember the take home messages. Ideally, the audience should remember three of the main points from the presentation. 2

Have a maximum of four short points per slide. If you can display something as a diagram, video, or a graph, use this instead of text and talk around it.

Animation is available in both Microsoft PowerPoint and the Apple Mac Keynote programme, and its use in presentations has been demonstrated to assist in the retention and recall of facts. 3 Do not overuse it, though, as it could make you appear unprofessional. If you show a video or diagram don’t just sit back—use a laser pointer to explain what is happening.

Rehearse your presentation in front of at least one person. Request feedback and amend accordingly. If possible, practise in the venue itself so things will not be unfamiliar on the day. If you appear comfortable, the audience will feel comfortable. Ask colleagues and seniors what questions they would ask and prepare responses to these questions.

It is important to dress appropriately, stand up straight, and project your voice towards the back of the room. Practise using a microphone, or any other presentation aids, in advance. If you don’t have your own presenting style, think of the style of inspirational scientific speakers you have seen and imitate it.

Try to present slides at the rate of around one slide a minute. If you talk too much, you will lose your audience’s attention. The slides or videos should be an adjunct to your presentation, so do not hide behind them, and be proud of the work you are presenting. You should avoid reading the wording on the slides, but instead talk around the content on them.

Maintain eye contact with the audience and remember to smile and pause after each comment, giving your nerves time to settle. Speak slowly and concisely, highlighting key points.

Do not assume that the audience is completely familiar with the topic you are passionate about, but don’t patronise them either. Use every presentation as an opportunity to teach, even your seniors. The information you are presenting may be new to them, but it is always important to know your audience’s background. You can then ensure you do not patronise world experts.

To maintain the audience’s attention, vary the tone and inflection of your voice. If appropriate, use humour, though you should run any comments or jokes past others beforehand and make sure they are culturally appropriate. Check every now and again that the audience is following and offer them the opportunity to ask questions.

Finishing up is the most important part, as this is when you send your take home message with the audience. Slow down, even though time is important at this stage. Conclude with the three key points from the study and leave the slide up for a further few seconds. Do not ramble on. Give the audience a chance to digest the presentation. Conclude by acknowledging those who assisted you in the study, and thank the audience and organisation. If you are presenting in North America, it is usual practice to conclude with an image of the team. If you wish to show references, insert a text box on the appropriate slide with the primary author, year, and paper, although this is not always required.

Answering questions can often feel like the most daunting part, but don’t look upon this as negative. Assume that the audience has listened and is interested in your research. Listen carefully, and if you are unsure about what someone is saying, ask for the question to be rephrased. Thank the audience member for asking the question and keep responses brief and concise. If you are unsure of the answer you can say that the questioner has raised an interesting point that you will have to investigate further. Have someone in the audience who will write down the questions for you, and remember that this is effectively free peer review.

Be proud of your achievements and try to do justice to the work that you and the rest of your group have done. You deserve to be up on that stage, so show off what you have achieved.

Competing interests: We have read and understood the BMJ Group policy on declaration of interests and declare the following interests: None.

- ↵ Rovira A, Auger C, Naidich TP. How to prepare an oral presentation and a conference. Radiologica 2013 ; 55 (suppl 1): 2 -7S. OpenUrl

- ↵ Bourne PE. Ten simple rules for making good oral presentations. PLos Comput Biol 2007 ; 3 : e77 . OpenUrl PubMed

- ↵ Naqvi SH, Mobasher F, Afzal MA, Umair M, Kohli AN, Bukhari MH. Effectiveness of teaching methods in a medical institute: perceptions of medical students to teaching aids. J Pak Med Assoc 2013 ; 63 : 859 -64. OpenUrl

Example sentences clinical presentation

Definition of 'clinical' clinical.

Definition of 'present' present

Cobuild collocations clinical presentation.

Browse alphabetically clinical presentation

- clinical pharmacology

- clinical phenotype

- clinical practice

- clinical presentation

- clinical professional

- clinical psychologist

- clinical psychology

- All ENGLISH words that begin with 'C'

Quick word challenge

Quiz Review

Score: 0 / 5

Wordle Helper

Scrabble Tools

Appointments at Mayo Clinic

- Pregnancy week by week

- Fetal presentation before birth

The way a baby is positioned in the uterus just before birth can have a big effect on labor and delivery. This positioning is called fetal presentation.

Babies twist, stretch and tumble quite a bit during pregnancy. Before labor starts, however, they usually come to rest in a way that allows them to be delivered through the birth canal headfirst. This position is called cephalic presentation. But there are other ways a baby may settle just before labor begins.

Following are some of the possible ways a baby may be positioned at the end of pregnancy.

Head down, face down

When a baby is head down, face down, the medical term for it is the cephalic occiput anterior position. This the most common position for a baby to be born in. With the face down and turned slightly to the side, the smallest part of the baby's head leads the way through the birth canal. It is the easiest way for a baby to be born.

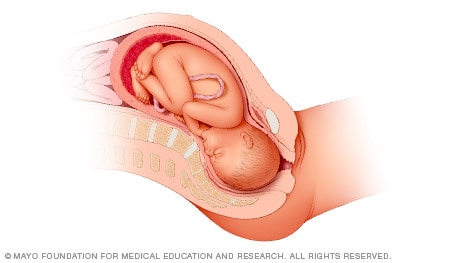

Head down, face up

When a baby is head down, face up, the medical term for it is the cephalic occiput posterior position. In this position, it might be harder for a baby's head to go under the pubic bone during delivery. That can make labor take longer.

Most babies who begin labor in this position eventually turn to be face down. If that doesn't happen, and the second stage of labor is taking a long time, a member of the health care team may reach through the vagina to help the baby turn. This is called manual rotation.

In some cases, a baby can be born in the head-down, face-up position. Use of forceps or a vacuum device to help with delivery is more common when a baby is in this position than in the head-down, face-down position. In some cases, a C-section delivery may be needed.

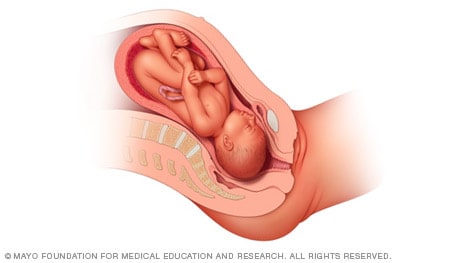

Frank breech

When a baby's feet or buttocks are in place to come out first during birth, it's called a breech presentation. This happens in about 3% to 4% of babies close to the time of birth. The baby shown below is in a frank breech presentation. That's when the knees aren't bent, and the feet are close to the baby's head. This is the most common type of breech presentation.

If you are more than 36 weeks into your pregnancy and your baby is in a frank breech presentation, your health care professional may try to move the baby into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. It involves one or two members of the health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

If the procedure isn't successful, or if the baby moves back into a breech position, talk with a member of your health care team about the choices you have for delivery. Most babies in a frank breech position are born by planned C-section.

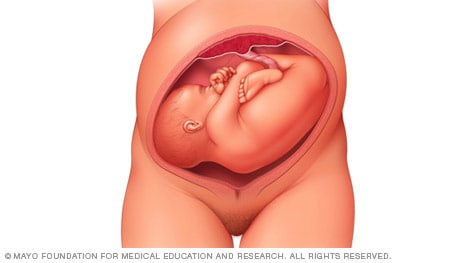

Complete and incomplete breech

A complete breech presentation, as shown below, is when the baby has both knees bent and both legs pulled close to the body. In an incomplete breech, one or both of the legs are not pulled close to the body, and one or both of the feet or knees are below the baby's buttocks. If a baby is in either of these positions, you might feel kicking in the lower part of your belly.

If you are more than 36 weeks into your pregnancy and your baby is in a complete or incomplete breech presentation, your health care professional may try to move the baby into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. It involves one or two members of the health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

If the procedure isn't successful, or if the baby moves back into a breech position, talk with a member of your health care team about the choices you have for delivery. Many babies in a complete or incomplete breech position are born by planned C-section.

When a baby is sideways — lying horizontal across the uterus, rather than vertical — it's called a transverse lie. In this position, the baby's back might be:

- Down, with the back facing the birth canal.

- Sideways, with one shoulder pointing toward the birth canal.

- Up, with the hands and feet facing the birth canal.

Although many babies are sideways early in pregnancy, few stay this way when labor begins.

If your baby is in a transverse lie during week 37 of your pregnancy, your health care professional may try to move the baby into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. External cephalic version involves one or two members of your health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

If the procedure isn't successful, or if the baby moves back into a transverse lie, talk with a member of your health care team about the choices you have for delivery. Many babies who are in a transverse lie are born by C-section.

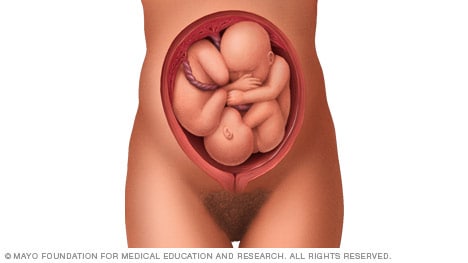

If you're pregnant with twins and only the twin that's lower in the uterus is head down, as shown below, your health care provider may first deliver that baby vaginally.

Then, in some cases, your health care team may suggest delivering the second twin in the breech position. Or they may try to move the second twin into a head-down position. This is done using a procedure called external cephalic version. External cephalic version involves one or two members of the health care team putting pressure on your belly with their hands to get the baby to roll into a head-down position.

Your health care team may suggest delivery by C-section for the second twin if:

- An attempt to deliver the baby in the breech position is not successful.

- You do not want to try to have the baby delivered vaginally in the breech position.

- An attempt to move the baby into a head-down position is not successful.

- You do not want to try to move the baby to a head-down position.

In some cases, your health care team may advise that you have both twins delivered by C-section. That might happen if the lower twin is not head down, the second twin has low or high birth weight as compared to the first twin, or if preterm labor starts.

- Landon MB, et al., eds. Normal labor and delivery. In: Gabbe's Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. 8th ed. Elsevier; 2021. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed May 19, 2023.

- Holcroft Argani C, et al. Occiput posterior position. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 19, 2023.

- Frequently asked questions: If your baby is breech. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/if-your-baby-is-breech. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Hofmeyr GJ. Overview of breech presentation. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Strauss RA, et al. Transverse fetal lie. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Chasen ST, et al. Twin pregnancy: Labor and delivery. https://www.updtodate.com/contents/search. Accessed May 22, 2023.

- Cohen R, et al. Is vaginal delivery of a breech second twin safe? A comparison between delivery of vertex and non-vertex second twins. The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine. 2021; doi:10.1080/14767058.2021.2005569.

- Marnach ML (expert opinion). Mayo Clinic. May 31, 2023.

Products and Services

- A Book: Obstetricks

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Guide to a Healthy Pregnancy

- 3rd trimester pregnancy

- Fetal development: The 3rd trimester

- Overdue pregnancy

- Pregnancy due date calculator

- Prenatal care: 3rd trimester

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Medical Definition of presenting

Dictionary entries near presenting.

presentation

preservative

Cite this Entry

“Presenting.” Merriam-Webster.com Medical Dictionary , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/medical/presenting. Accessed 16 May. 2024.

More from Merriam-Webster on presenting

Thesaurus: All synonyms and antonyms for presenting

Nglish: Translation of presenting for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of presenting for Arabic Speakers

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

More commonly misspelled words, your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, more commonly mispronounced words, how to use em dashes (—), en dashes (–) , and hyphens (-), popular in wordplay, birds say the darndest things, a great big list of bread words, 10 scrabble words without any vowels, 12 more bird names that sound like insults (and sometimes are), 8 uncommon words related to love, games & quizzes.

- presentation

: an activity in which someone shows, describes, or explains something to a group of people

: the way in which something is arranged, designed, etc. : the way in which something is presented

: the act of giving something to someone in a formal way or in a ceremony

Full Definition of PRESENTATION

First known use of presentation, related to presentation, other business terms, rhymes with presentation, definition of presentation for kids, medical definition of presentation, learn more about presentation.

- presentation copy

- presentation piece

- presentation time

- breech presentation

- face presentation

Seen & Heard

What made you want to look up presentation ? Please tell us where you read or heard it (including the quote, if possible).

- Spanish Central

- Learner's ESL Dictionary

- WordCentral for Kids

- Visual Dictionary

- SCRABBLE ® Word Finder

- Merriam-Webster's Unabridged Dictionary

- Britannica English - Arabic Translation

- Nglish - Spanish-English Translation

- Advertising Info

- Dictionary API

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- About Our Ads

- Browser Tools

- The Open Dictionary

- Browse the Dictionary

- Browse the Thesaurus

- Browse the Spanish-English Dictionary

- Browse the Medical Dictionary

We have a new app!

Take the Access library with you wherever you go—easy access to books, videos, images, podcasts, personalized features, and more.

Download the Access App here: iOS and Android . Learn more here!

- Remote Access

- Save figures into PowerPoint

- Download tables as PDFs

7: Atypical Presentations of Illness in Older Adults

Carla M. Perissinotto, MD, MHS; Christine Ritchie, MD, MSPH

- Download Chapter PDF

Disclaimer: These citations have been automatically generated based on the information we have and it may not be 100% accurate. Please consult the latest official manual style if you have any questions regarding the format accuracy.

Download citation file:

- Search Book

Jump to a Section

Introduction, defining atypical presentations, identifying patients at risk.

- Full Chapter

- Supplementary Content

Traditional education of health care clinicians hinges on typical presentations of common illnesses. Yet, what is often left out from medical training is the frequent occurrence of atypical presentations of illness in older adults. These presentations are termed “ atypical ” because they lack the usual signs and symptoms characterizing a particular condition or diagnosis. In older adults, “atypical” presentations are actually quite common. For example, a change in behavior or functional ability is often the only sign of a new, potentially serious illness. Failure to recognize atypical presentations may lead to worse outcomes, missed diagnoses, and missed opportunities for treatment of common conditions in older patients.

In medical education, teaching about atypical presentations of medical illness in the older patient offers a unique opportunity to introduce key geriatric principles to trainees at all levels of training. Furthermore, atypical medical presentations in the older adult are now an Accreditation for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Geriatrics competency, underscoring the importance of integrating this concept into medical education for all learners.

The definition of an atypical presentation of illness is: when an older adult presents with a disease state that is missing some of the traditional core features of the illness usually seen in younger patients . Atypical presentations usually include one of 3 features: (a) vague presentation of illness, (b) altered presentation of illness, or (c) nonpresentation of illness (ie, underreporting).

The prevalence of atypical presentation of illness in older adults increases with age. With the aging of the world’s population, atypical presentations of illness will represent an increasingly large proportion of illness presentations. The most common risk factors include:

Increasing age (especially age 85 years or older)

Multiple medical conditions (“multimorbidity”)

Multiple medications (or “polypharmacy”)

Cognitive or functional impairment

Understanding which patients may be more at risk of atypical disease presentation will guide clinicians to more astutely pick up subtle signs of illness. Rather than approaching a patient visit in the “traditional” way, the clinician may also need to expand beyond the “typical” evaluation of illness and incorporate questions or exam findings that correlate with an atypical presentation ( Table 7–1 ). For example, recognition of an atypical presentation of illness requires a clinician to pay more attention to small changes in cognition compared to baseline. In the case of a patient with dementia, this can be difficult to determine as some older adults with dementia still experience minor daily variations in cognition. Gathering this baseline level of information requires patience, time, and having reliable caregivers and family member informants. Many times, in order to arrive at an accurate history of present illness, the clinician will have to undertake a systematic investigative approach.

Sign in or create a free Access profile below to access even more exclusive content.

With an Access profile, you can save and manage favorites from your personal dashboard, complete case quizzes, review Q&A, and take these feature on the go with our Access app.

Pop-up div Successfully Displayed

This div only appears when the trigger link is hovered over. Otherwise it is hidden from view.

Please Wait

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Health Topics

- Drugs & Supplements

- Medical Tests

- Medical Encyclopedia

- About MedlinePlus

- Customer Support

Partial Thromboplastin Time (PTT) Test

What is a ptt (partial thromboplastin time) test.

A partial thromboplastin time (PTT) test uses a blood sample to measure how long it takes for your blood to make a clot . Normally, when you get a cut or injury that causes bleeding, many different types of proteins in your blood work together to make a clot to stop the bleeding. These proteins are called coagulation factors or clotting factors.

If any of your clotting factors are missing, at a low level, or not working properly, your blood may:

- Clot too slowly after an injury or surgery. If this happens, you have a bleeding disorder . Bleeding disorders can cause serious blood loss. Hemophilia is one type of bleeding disorder.

- Clot too much and/or too quickly, even without an injury. This condition may lead to clots that block your blood flow and cause serious conditions, such as heart attack , stroke , or clots in the lungs .

A PTT test helps check a specific group of clotting factors. It helps show how much of these clotting factors you have and how well they're working. A PTT test is often done with other tests that check clotting factors and how well they all work together.

Other names: activated partial thromboplastin time, aPTT, intrinsic pathway coagulation factor profile

What is it used for?

A PTT test is used to check for problems with a specific group of blood clotting factors. The test is done to:

- Find the cause of too much bruising or bleeding.

- Find the cause of clotting problems. Causes can include certain autoimmune diseases such as lupus and antiphospholipid syndrome (APS).

- Monitor people taking heparin , a type of medicine that's used to prevent and treat blood clots. PTT testing can help make sure the dose is safe and effective.

- Check the risk for possible bleeding problems before surgery or medical procedures. (A PTT test is not always used as a routine test before surgery. It may be used for certain people who may have a risk for bleeding problems).

Why do I need a PTT test?

You may need a PTT test if you:

- Have problems with bleeding or bruising and the cause is not known

- Have a blood clot in a vein or artery

- Have liver disease (your liver makes most of your clotting factors).

- Have had several miscarriages

- Have been diagnosed with a bleeding or clotting disorder and don't know which clotting factors are involved

- Are taking heparin (to check how this medicine is affecting you, your health care provider may use a PTT test or another test instead).

What happens during a PTT test?

A health care professional will take a blood sample from a vein in your arm, using a small needle. After the needle is inserted, a small amount of blood will be collected into a test tube or vial. You may feel a little sting when the needle goes in or out. This usually takes less than five minutes.

Will I need to do anything to prepare for the test?

You don't need any special preparations for a PTT test.

Are there any risks to the test?

There is very little risk to having a blood test. You may have slight pain or bruising at the spot where the needle was put in, but most symptoms go away quickly.

What do the results mean?

Your PTT test results will show how much time it took for your blood to clot. Results are usually given as a number of seconds. A PTT test is often ordered along with another blood test called a prothrombin time (PT) test . A PT test measures other clotting factors that a PTT test doesn't check. Your provider will usually compare the results of both tests to understand how your blood is clotting. Ask your provider to explain what your test results mean for your health.

In general, if your blood took longer than normal to clot on a PTT test , it may be a sign of:

- Liver disease.

- A lack of vitamin K .

- Von Willebrand disease .

- Hemophilia.

- Too much heparin.

- Certain types of leukemia .

- Autoimmune diseases, such as antiphospholipid antibody syndrome or lupus anticoagulant syndrome. These diseases cause your body to make proteins called antibodies. The antibodies related to these diseases cause too much clotting . But the results of a PTT test may show a slow clotting time. That's because the chemicals in the PTT test react with the antibodies in your blood sample. This chemical reaction makes the blood sample clot more slowly than the blood in your body. If your provider thinks that an autoimmune disease is causing a clotting problem, you will usually have other tests to make a diagnosis.

If your blood clotted faster than normal on a PTT test , it may be a sign of:

- The early stage of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). This rare but serious condition may develop if you have an infection or damage to organs or tissues that affects blood clotting. In the early stage, you have too much blood clotting. Later on, DIC starts to use up clotting factors in your blood, which leads to bleeding problems.

- Cancer of the ovaries , colon , or pancreas that is advanced, which means the cancer has spread to other parts of the body and is unlikely to be controlled with treatment.

Talk with your provider to learn what your test results mean.

Learn more about laboratory tests, reference ranges, and understanding results .

Is there anything else I need to know about a PTT test?

If your provider thinks you may have a clotting disorder linked to lupus, you may have a test called an LA-PTT. This is a type of PTT test that is designed to look for a protein that's linked to increased clotting and having many miscarriages.

- American Society of Hematology [Internet]. Washington D.C.: American Society of Hematology; c2022. Bleeding Disorders; [cited 2022 Oct 4]; [about 2 screens]. Available from: https://www.hematology.org/education/patients/bleeding-disorders

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Internet]. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Diagnosis of Hemophilia; [updated 2020 Jul 17; cited 2022 Oct 4]; [about 3 screens]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/hemophilia/diagnosis.html

- Hinkle J, Cheever K. Brunner & Suddarth's Handbook of Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests. 2nd Ed, Kindle. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; c2014. Partial Thromboplastin Time (PTT); p. 400.

- Indiana Hemophilia & Thrombosis Center [Internet]. Indianapolis: Indiana Hemophilia & Thrombosis Center Inc.; c2022. Conditions tread at the IHTC; [cited 2022 Oct 4]; [about 1 screen]. Available from: https://www.ihtc.org/conditions

- Kids Health from Nemours [Internet]. Jacksonville (FL): The Nemours Foundation; c1995–2022. Blood Test: Partial Thromboplastin Time (PTT); [cited 2022 Oct 4]; [about 2 screens]. Available from: https://kidshealth.org/en/parents/test-ptt.html

- Mayo Clinic: Mayo Medical Laboratories [Internet]. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research; c1995–2022. Test ID: ATPTT: Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time (APTT), Plasma: Clinical and Interpretive; [cited 2022 Oct 4]; [about 2 screens]. Available from: https://www.mayocliniclabs.com/test-catalog/overview/40935#Clinical-and-Interpretive

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; Blood Tests; [updated 2022 Mar 24; cited 2022 Oct 4]; [about 7 screens]. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/blood-tests

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; What are Bleeding Disorders; [updated 2022 Mar 24; cited 2022 Oct 12]; [about 4 screens]. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/bleeding-disorders

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; What are Blood Clotting Disorders; [updated 2022 Mar 24; cited 2022 Oct 12]; [about 4 screens]. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/clotting-disorders

- Pathology Tests Explained [Internet]. Alexandria (Australia): Australasian Association for Clinical Biochemistry and Laboratory Medicine; c2022. Activated partial thromboplastin time; [Reviewed 2022 May 16; cited 2022 Oct 12]; [about 6 screens]. Available from: https://pathologytestsexplained.org.au/learning/test-index/aptt

- Riley Children's Health [Internet]. Indianapolis: Riley Hospital for Children at Indiana University Health; c2022. Coagulation Disorders; [cited 2022 Oct 4]; [about 7 screens]. Available from: https://www.rileychildrens.org/health-info/coagulation-disorders

- Rountree KM, Yaker Z, Lopez PP. Partial Thromboplastin Time. [Updated 2021 Aug 11; cited 2022 Oct 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507772/

- Testing.com [Internet]. Seattle (WA): OneCare Media; c2022. Patrial Thromboplastin Time (PTT, aPTT); [modified 2021 Nov 9; cited 2022 Oct 4]; [about 15 screens]. Available from: https://www.testing.com/tests/partial-thromboplastin-time-ptt-aptt/

- UF Health: University of Florida Health [Internet]. Gainesville (FL): University of Florida; c2022. Partial thromboplastin time (PTT): Overview; [reviewed 2021 Jan 19; cited 2022 Oct 4]; [about 3 screens]. Available from: https://ufhealth.org/partial-thromboplastin-time-ptt

- University of Rochester Medical Center [Internet]. Rochester (NY): University of Rochester Medical Center; c2022. Health Encyclopedia: Activated Partial Thromboplastin Clotting Time; [cited 2022 Oct 4]; [about 3 screens]. Available from: https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/encyclopedia/content.aspx?contenttypeid=167&contentid=aptt

- UW Health [Internet]. Madison (WI): University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics Authority; c2022. Partial Thromboplastin Time (PTT) Test; [updated 2022 Jan 10; cited 2022 Oct 4]; [about 8 screens]. Available from: https://patient.uwhealth.org/healthwise/article/en-us/hw203152

- WFH: World Federation of Hemophilia [Internet]. Montreal Quebec, Canada: World Federation of Hemophilia; c2022. von Willebrand Disease (VWD); [cited 2022 Oct 4]; [about 2 screens]. Available from: https://elearning.wfh.org/elearning-centres/von-willebrand-disease/

The information on this site should not be used as a substitute for professional medical care or advice. Contact a health care provider if you have questions about your health.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Effectiveness of Clinical Presentation (CP) Curriculum in teaching clinical medicine to undergraduate medical students: A cross-sectional study.

Saroj adhikari yadav.

1 Patan Academy of Health Sciences, Kathmandu, 44600, Nepal

Sangeeta Poudel

Swotantra gautam.

2 B P Koirala Institute of Health Sciences, Dharan, Nepal

Sanjay Kumar Jaiswal

Samikchya baskota, aaradhana adhikari, binod duwadi, nischit baral, sanjay yadav.

3 Institute of Medicine, Kathmandu, 44600, Nepal

Associated Data

Underlying data.

Figshare: CP Curriculum Raw data updated in Excel and PDF. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.18666410.v1 10

This project contains the following underlying data:

- - Analysis and Raw data.xlsx

Extended data

This project contains the following extended data:

- - CP Questionnaire for Faculties.pdf

- - CP Questionnaire for students.pdf

- - CP Surprise exam Questionnaire.pdf

Data are available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC-BY 4.0).

Peer Review Summary

Introduction: The Clinical Presentation (CP) curriculum was first formulated in 1990 at the University of Calgary, Canada. Since then, it has been adopted at various medical schools, including Patan Academy of Health Sciences (PAHS), a state-funded medical school in a low-income country (LIC), Nepal. This study aims to evaluate the perceived effectiveness of the CP curriculum by students and faculty at PAHS, and test knowledge retention through a surprise non-routine exam administered to students.

Method: This is a cross-sectional study to evaluate the efficacy of the CP curriculum in teaching clinical medicine to the first batch of MBBS students of PAHS School of Medicine. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Committee (IRC)-PAHS (Ref no std1505911069). Perceived effectiveness was evaluated using a set of questionnaires for faculty and students. A total of 33 students and 34 faculty filled the perception questionnaires. Subsequently, a questionnaire consisting of 50 Multiple Choice Questions (MCQs) from different clinical medicine disciplines was administered to test students’ knowledge retention. Out of 49 students, 38 participated in the surprise non-routine exam.

Result: A significantly higher number of faculty preferred the CP curriculum compared to the traditional system of teaching clinical medicine (16 vs 11, Kruskal Wallis: 0.023, ie. P-value < 0.05). A significantly higher number of the students liked and recommended CP curriculum in the clinical year of medical education (20 vs. 13 with p-value < 0.05). In the non-routine surprise exam, two thirds of the students scored 60% or above.

Conclusion: Both faculty and students perceive that the CP curriculum system is an effective teaching and learning method in medical education, irrespective of their different demographic and positional characteristics. The students’ overall performance was good in surprise, non-routine exams taken without scheduling or reminders.

Introduction

Sir William Osler, considered the father of modern medicine, emphasized the teacher's role in helping students to observe and reason. He recommended abolishing the traditional lecture method of instruction. 1 Medical education is evolving in response to scientific advances and societal needs. 2 A well-organized comprehensive knowledge domain has practical implications in clinical problem solving, and appropriate teaching and learning methods play an important role in achieving the educational goals. 3

Clinical presentation (CP) is a relatively new and innovative approach to teaching medicine. CP engages medical students in their understanding of the disease process from clinical feature to diagnosis. Students begin studying abnormalities of complaints, examination, and laboratory findings; i.e., signs, symptoms, and laboratory investigations which a patient presents to the doctor with. Students then progress towards diagnosis. The underlying philosophy of the CP Curriculum is that: “The reaction of the human body to an infinite number of insults is always finite and stable over time”. 4 For example, if there is any attack on the respiratory system, whether infectious, inflammatory, immunological, traumatic, or iatrogenic; the respiratory system responds through coughing, cyanosis, chest pain, difficulty breathing, noisy breathing, or hemoptysis. 4 Thus, the CP Curriculum aims to help students understand the process of moving from “symptoms to diagnosis.”

The CP curriculum was first formulated in 1990 at the University of Calgary Faculty of Medicine in Canada. 5 The curriculum was adopted and redesigned based on local needs at various medical schools worldwide. Patan Academy of Health Sciences (PAHS), a state-funded medical school in Nepal, has adopted several new and innovative approaches in teaching and learning medicine. The CP Curriculum is one of the several approaches adopted by PAHS. 6

PAHS medical education team assumes that the CP curriculum is better than traditional lecture-based teaching. In this study we are testing the perceived effectiveness of students and faculty, and the level of knowledge among the students trained by the CP curriculum. The level of knowledge was assessed by marks scored by the students in a surprise non-routine exam without prior information. Perceived effectiveness was based on the thinking/perception of the students and faculty on the effectiveness of the CP curriculum. We assume the CP curriculum is at least not inferior to traditional lecture-based teaching.

Study design

This is a cross-sectional study that aims to evaluate the efficacy of the CP curriculum in teaching different disciplines of clinical medicine to undergraduate medical students of PAHS, which is currently the only medical school implementing the CP-curriculum in undergraduate medical education. A new Multiple-Choice Question (MCQ) based questionnaire was designed to evaluate the level of knowledge and two separate questionnaires were developed for faculty to evaluate perception about CP-curriculum.

Study population

All consenting medical students from 2016 of PAHS School of Medicine currently in clinical clerkship years and all clinical sciences faculty who had delivered at least one teaching-session with the CP curriculum to these students were included in the study. Consenting students were asked to fill the questionnaire together in class, whereas faculty were approached personally and asked to complete the questionnaires. Students and faculty who were part of the study team, those who didn’t provide consent, and those who participated in the pilot survey section of the questionnaire developed for this study were excluded. All 34 faculty completed the perception questionnaires, with zero non-response rate. Out of 49 students, 33 completed the perception questionnaires and 38 turned up to the surprise non-routine exam for assessment of knowledge retention.

Ethics and consent

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Committee (Ethical Committee) of Patan Academy of Health Sciences (PAHS), Kathmandu, Nepal (Ref No std1505911069). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before completing the questionnaire. Students who gave verbal consent were asked to complete the questionnaire together in class. Faculty were approached personally and requested to complete the questionnaires. At the start of each questionnaire, a tick box was used for participants to indicate written consent. Participants were informed verbally and in writing that their names and identifiying information would be kept anonymous, and their data would only be used for research purposes.

Data collection

Three sets of questionnaires were used. The first set of questionnaires were designed to test the perceived effectiveness of the CP curriculum from the faculty perspective. It contained seven questions on background information (age, sex, job position, highest academic degree, etc) and 13 questions on perceived effectiveness.

Similarly, the second set of questionnaires for the students included 11 questions on background information and 15 questions on perceived effectiveness. The perception questionnaire had questions about effectiveness or satisfaction in regard to different aspects of the CP curriculum. Participants had to respond with a tick mark in a Likert scale ranging from one (strongly agree) to five (strongly disagree) for each question.

The third set of questionnaires tested the students' clinical knowledge and contained 50 MCQs from different clinical medicine disciplines. Based on curriculum of the university, there were seven MCQs each from surgery, medicine, pediatrics, obstetrics and gynecology, and two questions each from orthopedics, emergency medicine, general practice, otolaryngology, anesthesiology, dermatology, dentistry, psychiatry, radiology, ophthalmology, and forensic medicine. The questions were randomly selected from the question pool of the Examination section of university. The selected questions were randomly arranged, and a surprise non-routine written exam was conducted with this questionnaire. A maximum time of one hour was provided to solve these 50 questions.

These questionnaires were compiled and discussed in the research group and reviewed by the research advisors to establish content validity. Copies of all three questionnaires can be found under Extended data. 10 They were administered to randomly selected 15 students and 15 faculty in a pilot study to establish the face validity and feasibility. The students and faculty randomly selected for the pilot study were administered the questionnaires to complete. Then they were asked in detail about the questionnaire and any suggestions for revisions or editing needed. The pilot survey was not powered for statistical comparisons. Only a few grammatical corrections were made after review and feedback from the pilot study. Subsequently, the final study was conducted.

The faculty participants were also involved in the development of the CP curriculum at PAHS, hence, responder bias in favor of CP curriculum may be present in this study.

The data collected were digitalized using Epi-Info version 7 software. These raw data were exported to MS-Excel. The excel sheet is made available in the public domain for readers. 10 SPSS version 13.0 was used for statistical test and analysis. Shapiro-Wilk test was used first to test the normality. Non-parametric tests (Mann-Whitney and Kruskal Wallis) was used for normal distribution. Classical ANOVA for equal variance and Welch ANOVA for unequal variance were used after testing the homogeneity of variance, and post-hoc/tukey test was used for significant classical ANOVA results.

In this study, we calculated the total score via forced Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) for each respondent determined as the dependent variable, and compared it with other variables i.e., background information. The total score of all the Likert scale questions was calculated, and the normality test was performed, keeping “total score” as the dependent variable. The full dataset can be found under Underlying data. 10

Response from faculty on perceived effectiveness of the CP curriculum

The data of the total score did not follow a normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk Test, p < 0.05), so a non-parametric test was used to compare the dependent variable. We used Mann-Whitney and Kruskal Wallis tests for the variables containing two groups and more than two groups, respectively.

Among the 34 respondents from the faculty group, 24 (70.59%) were male, and 10 (29.41%) were female. 20 (58.82%) of the faculty respondents were lecturers, and the remaining 14 (41.18%) were senior professors, associate professors, and assistant professors. Out of the 34 respondents, 31 (91.18%) were involved in developing the CP curriculum at PAHS. However, 3 (8.82%) were involved in teaching the curriculum but not in developing the CP curriculum.

As many as 15 (44.12%) respondents favored the CP curriculum system over the traditional system, 11 (32.35%) preferred the traditional teaching system, and 8 (23.53%) preferred both. Overall, the faculty liked the CP curriculum more than the traditional system of teaching clinical medicine (Kruskal Wallis = 0.023, p-value < 0.05). The majority of faculty, 27 (79.41%), would suggest future students to join a medical school that implemented the CP curriculum system rather than the traditional system. Only 12 (35.29%) of them thought that the CP curriculum system should be the sole leading teaching and learning system in clinical medicine, meaning more faculty preferred a hybrid system of both the CP curriculum and the traditional system. However, these differences were not statistically significant (p-value > 0.05).

As shown in Table 1 , a significant number of faculty (p values > 0.05) perceive the CP curriculum to be more effective than the traditional system for teaching clinical medicine to undergraduate medical students. There is no significant difference in the perception of the effectiveness of the CP curriculum among faculty based on academic rank, gender, highest academic degree, or the institution of their residency training (p-value > 0.05). The median number of faculty who perceive the CP curriculum system to be more effective and suggest future students to study medicine in this system rather than the traditional system is higher. But, the difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05). There was no significant difference in faculty foreseeing the CP curriculum as the leading method of teaching and learning medical education in the future (p > 0.05).

Response from students on perceived effectiveness of the CP curriculum

The normality test shows that the total score data follows a normal distribution (Shapiro-Wilk, p > 0.05) with a mean value of 50.57 with a standard deviation of 8.17. Therefore, we used a parametric test to compare the test variable with others. We subsequently tested for homogeneity of variance: we used classical ANOVA for equal variance, and Welch ANOVA for unequal variance. Finally, if significant classical ANOVA results were obtained, we used the post-hoc/tukey test.

There were 33 respondents, among which 23 (69.70%) were males, and 10 (30.30%) were females. The age group of respondents was between 20 to 30 years. A significantly higher number (20 i.e., 60.61%) of the respondents recommended studying in a medical school implementing CP curriculum (p < 0.05). No significant differences were seen between educational or geographical backgrounds and scholarship categories (p > 0.05) as shown in Table 2 .

Assessment for knowledge retention of the students

An hourly surprise non-routine written exam was conducted to test the knowledge of the students. A copy of this exam can be found under Extended data. 10 The exam included 50 MCQs from different disciplines of clinical medicine. The surprise test was conducted without prior reminders, and 38 out of 49 students participated. The findings, as outlined in Table 3 , show that 24 out of 38 (65.79%) of the students scored 60% or higher. The results demonstrate that approximately two-thirds of the students passed the surprise test, indicating good test performance.

The current study shows a higher preference for the CP curriculum by undergraduate medical students and faculty at PAHS for teaching and learning clinical medicine in medical school. These findings further substantiate previous reviews on the principles of teaching methods and the acceptability of the curriculum.

This curriculum was chosen in part because of confidence in the comprehensiveness of the knowledge it encompasses. Equally important was the organization of medical knowledge that this curriculum engenders: each clinical presentation is organized according to a variable number of causal diagnostic categories. Each of these categories is identified by a prototype. Exhaustive lists of diagnoses belonging to a given category are avoided. As students' clinical experiences increase and they encounter more diagnoses, the students can add them to the appropriate causal categories stored in their memories. How the diagnostic prototypes are presented allows students to identify the discriminating features within and between each. The process by which students can compare and contrast the distinctive features of each disease is facilitated. It is so because the CP curriculum is well organized and comprehensive. 3 , 7 Since the CP curriculum is simple to follow and to organize the learning content, students in the CP curriculum also reported less stress due to the volume and complexity of study materials and examinations. 7

Prior studies at the University of Calgary demonstrated a substantial effect size on students’ retention of basic science knowledge while participating in the CP curriculum. 8 Our study conducted on clinical clerkship year participants showed that two-thirds of students achieved 60% (passing scores) or more in the surprise non-routine exam, signifying a high retention of clinical discipline knowledge. Findings from the current study expand on the effectiveness of the curriculum across medical school years with respect to knowledge retention.

A study done among medical students utilizing the CP curriculum showed a favorable response to the use of schema in the CP curriculum. 9 In our study, we could not evaluate the use the schemas of CP to perform clinical assessment in order to reach the appropriate diagnosis. We recommend further studies in this respect. Additionally, long-term knowledge retention was not tested in our study, which could be another important area of investigation.

This study has several other limitations as well. The study was conducted at a single institution, thereby potentially reducing the overall generalizability of the findings. The faculty members recruited as participants for assessing the perceived effectiveness of the curriculum were also involved in the adaptation and development of curriculum at PAHS, hence, potentially increasing responder’s bias in the study by some degree. The cross-sectional nature of the study provides only a limited understanding of the effects of the curriculum over the long term.

Based on this study, we can conclude that both faculty and students perceive the CP curriculum system as an effective teaching and learning method in medicine, irrespective of their demographic and positional characteristics. The findings suggest higher knowledge retention in knowledge by implementing the CP curriculum during clinical clerkship years. Since the 1990s, CP Curriculum has been established as a multidimensional teaching-learning method in many medical school systems. In the evolving medical education world with rapid digitization, massive turnover of medical and education data, and increased use of remote learning methods, a deeper understanding of influencing variables will help effectively utilize this highly valued curriculum.

Data availability

Authors' contributions.

SAY, SKJ, AA, and BD conceptualized and designed the study. All 9 authors; SAY, SJ, SP, SG, SB, AA, BD, NB, and SY contributed to data analysis and interpretation. SAY and SP wrote the first draft of the article. All 9 authors, SAY, SP, SG, SJ, SB, AA, BD, NB, and SY critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version of manuscript for publication.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof. Dr. Kedar Prasad Baral and Prof. (Associate) Shital Bhandary for their immense help during this research. We thank all respondent faculty and medical students of PAHS for participating in the study.

[version 1; peer review: 1 approved

Funding Statement

The author(s) declared that no grants were involved in supporting this work.

Reviewer response for version 1

1 Health Action and Research, Kathmandu, Kathmandu, Nepal

2 International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France

Dear author(s),

Thank you for your hard work on this research manuscript. Please find my comments/ queries below.

The research article deals with the effectiveness of Clinical Presentation (CP) curriculum in teaching clinical medicine to undergraduate medical students. CP curriculum is yet to be adopted in many low- and middle-income countries. The results show that the medical students and the faculty were satisfied with the CP curriculum and believed CP as a stand-alone method of teaching as well as in conjunction with traditional methods of teaching could benefit medical students.

Study design:

“This is a cross-sectional study that aims to evaluate the efficacy of the CP curriculum in teaching different disciplines of clinical medicine to undergraduate medical students of PAHS, which is currently the only medical school implementing the CP-curriculum in undergraduate medical education.”

- Is PAHS the only medical school implementing the CP-curriculum in Nepal or worldwide?

Ethics and consent:

“Students who gave verbal consent were asked to complete the questionnaire together in class.”

- Please elaborate on this sentence.

- Was any faculty member present in the class?

- Was the test compulsory or optional?

- Did the students have the right to refuse the test or leave the test in between?

Data collection:

- Was the questionnaire in English?

- How long did the questionnaire take to complete?

- How much time were the respondents given to complete the questionnaire?

- What were the minimum and maximum possible scores (total or based on questionnaire sets)?

I hope the comments are useful and would enable the author(s) to strengthen this study.

Is the work clearly and accurately presented and does it cite the current literature?

If applicable, is the statistical analysis and its interpretation appropriate?

Are all the source data underlying the results available to ensure full reproducibility?

Is the study design appropriate and is the work technically sound?

Are the conclusions drawn adequately supported by the results?

Are sufficient details of methods and analysis provided to allow replication by others?

Reviewer Expertise:

Global health, gerontology, cancer

I confirm that I have read this submission and believe that I have an appropriate level of expertise to confirm that it is of an acceptable scientific standard, however I have significant reservations, as outlined above.

Jayadevan Sreedharan

1 Department of Community Medicine, Gulf Medical University, Ajman, United Arab Emirates

Title: Effectiveness of Clinical Presentation (CP) Curriculum in teaching clinical medicine to undergraduate medical students: A cross-sectional study.

This study aimed to assess the perceived effectiveness of students and faculty and the level of knowledge among the students trained by the CP curriculum. The authors assume the CP curriculum is not inferior to traditional lecture-based teaching.

Are sufficient details of methods and analysis provided to allow replication by others?:

It is not clear why the authors have given MCQ to the faculty (their score is given and statistical test done).

If applicable, is the statistical analysis and its interpretation appropriate?:

The authors mentioned in the article that "Classical ANOVA for equal variance and Welch ANOVA for unequal variance were used after testing the homogeneity of variance, and post-hoc/Tukey test was used for significant classical ANOVA results", where they have used this test is not clear in the manuscript.

The p-value is given in exact value; the importance of p-value is to check whether to accept the null or alternate hypothesis. In the methodology, they mentioned that p-value >0.05 is not significant. Then what more information do the readers get if they include the actual p-value?

The sample size of this study is very small and the conclusion from this study can not be generalised to the entire population.

The authors mentioned in the conclusion that "The findings suggest higher knowledge retention in knowledge by implementing the CP curriculum during clinical clerkship years" . How the authors reach this conclusion is unclear.

Epidemiology, Biostatistics, Medical education, Public health

Priyanka Panday

1 California Institute of Behavioral Neurosciences & Psychology, Fairfield, CA, USA

This article focuses on the importance of the clinical presentation (CP) curriculum in a particular institute (Patan Academy of Health Sciences (PAHS)) among medical students and faculty in terms of their preference and performance on a surprise non-routine exam.

- Cross-sectional study is appropriate as a study design for this article.

- Relevant articles from 2020, 2019, and 2004 have been appropriately cited as references.

- The methods used for data collection, as well as the result of the study has been elaborated in detail to ensure accuracy.

- Results are presented in a tabular form and the conclusion derived coincides with the results indicating the effectiveness of the CP curriculum system as an effective teaching and learning method in medicine.

- As far as the statistical analysis is concerned, it is not my area of expertise. However, p< 0.05 for response of effective implementation of the CP curriculum and the response from faculty is statistically significant.

I cannot comment. A qualified statistician is required.

Endocrine disorders, Heart conditions, Medications, COVID-19, Obstetric conditions, Epilepsy, HIV, etc.

I confirm that I have read this submission and believe that I have an appropriate level of expertise to confirm that it is of an acceptable scientific standard.

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

This definition of medical jargon appears to be a dictionary definition. Please rewrite it to present the subject from an encyclopedic point of view. (May 2023) In medicine, a presentation is the appearance in a patient of illness or disease—or signs or symptoms thereof—before a medical professional.

presentation. (prĕz′ən-tā′shən, prē′zən-) n. Medicine. a. The position of the fetus in the uterus at birth with respect to the mouth of the uterus. b. A symptom or sign or a group of symptoms or signs that is evident during a medical examination: The patient's presentation was consistent with a viral illness. c.

The oral presentation is a critically important skill for medical providers in communicating patient care wither other providers. It differs from a patient write-up in that it is shorter and more focused, providing what the listeners need to know rather than providing a comprehensive history that the write-up provides.

The term presentation describes the leading part of the fetus or the anatomical structure closest to the maternal pelvic inlet during labor. The presentation can roughly be divided into the following classifications: cephalic, breech, shoulder, and compound. Cephalic presentation is the most common and can be further subclassified as vertex, sinciput, brow, face, and chin.

Delivery. It is important to dress appropriately, stand up straight, and project your voice towards the back of the room. Practise using a microphone, or any other presentation aids, in advance. If you don't have your own presenting style, think of the style of inspirational scientific speakers you have seen and imitate it.

presentation: [noun] the act of presenting. the act, power, or privilege especially of a patron of applying to the bishop or ordinary for instituting someone into a benefice.

Medical Dictionary. Search medical terms and abbreviations with the most up-to-date and comprehensive medical dictionary from the reference experts at Merriam-Webster. Master today's medical vocabulary. Become an informed health-care consumer!

clinical presentation: The constellation of physical signs or symptoms associated with a particular morbid process, the interpretation of which leads to a specific diagnosis

The art of presenting. The oral case presentation is a time-honoured tradition whereby a trainee presents a new admission to the attending physician. We describe the presentation styles of students, residents and staff physicians and offer pointers on how to present like stereotypical members of each group. Although the case presentation occurs ...

Breech presentation refers to the fetus in the longitudinal lie with the buttocks or lower extremity entering the pelvis first. The three types of breech presentation include frank breech, complete breech, and incomplete breech. In a frank breech, the fetus has flexion of both hips, and the legs are straight with the feet near the fetal face, in a pike position. The complete breech has the ...

Occiput or cephalic anterior: This is the best fetal position for childbirth. It means the fetus is head down, facing the birth parent's spine (facing backward). Its chin is tucked towards its chest. The fetus will also be slightly off-center, with the back of its head facing the right or left. This is called left occiput anterior or right ...

CLINICAL PRESENTATION definition | Meaning, pronunciation, translations and examples

When a baby is head down, face down, the medical term for it is the cephalic occiput anterior position. This the most common position for a baby to be born in. With the face down and turned slightly to the side, the smallest part of the baby's head leads the way through the birth canal. It is the easiest way for a baby to be born.

Medical Terminology I 10 the heart. The "o" is a combining vowel that has no meaning. And finally, "gram" refers to a recording. By combining the meanings of the word parts you can easily interpret an "echocardiogram" as a "recording of a heart test using ultrasonic waves." Slide 27 Many medical terms come from Greek or Latin words.

adjective. pre· sent· ing pri-ˈzent-iŋ. : of, relating to, or being a symptom, condition, or sign which is evident or disclosed by a patient on physical examination. may be the presenting sign of a severe systemic disease H. H. Roenigk, Jr.

more prefixes or suffixes. This handout will describe how word parts create meaning to provide a strategy for decoding medical terminology and unfamiliar words in the English language. Word Parts . If all three word parts are present in medical terminology, they will be in the order of prefix root word suffix.

Definition of PRESENTATION for Kids. 1. : an act of showing, describing, or explaining something to a group of people. 2. : an act of giving a gift or award. 3. : something given. Medical Dictionary.

The definition of an atypical presentation of illness is: when an older adult presents with a disease state that is missing some of the traditional core features of the illness usually seen in younger patients. Atypical presentations usually include one of 3 features: (a) vague presentation of illness, (b) altered presentation of illness, or (c ...

A partial thromboplastin time (PTT) test uses a blood sample to measure how long it takes for your blood to make a clot. Normally, when you get a cut or injury that causes bleeding, many different types of proteins in your blood work together to make a clot to stop the bleeding. These proteins are called coagulation factors or clotting factors.

Introduction: The Clinical Presentation (CP) curriculum was first formulated in 1990 at the University of Calgary, Canada.Since then, it has been adopted at various medical schools, including Patan Academy of Health Sciences (PAHS), a state-funded medical school in a low-income country (LIC), Nepal.

5. Definition • Medical terminology is language that is used to accurately describe the human body and associated components, conditions, processes and procedures in a science-based manner. • Some examples are: R.I.C.E., trapezius, and latissimus dorsi. It is to be used in the medical and nursing fields. 6.

The use of certain abbreviations can be dangerous and lead to patient injury or death. Examples of error-prone medical abbreviations include: IU (international unit): may be confused with "IV" (intravenous) µg (microgram): may be confused with mg (milligram) U (unit): may be mistaken for "0" (zero), increasing the dose tenfold.

Discover Medical Abbreviations: Dive deeper into a comprehensive list of top-voted Medical Acronyms and Abbreviations. Explore PPT Definitions: Discover the complete range of meanings for PPT, beyond just its connections to Medical. Expand Your Knowledge: Head to our Home Page to explore and understand the meanings behind a wide range of acronyms and abbreviations across diverse fields and ...