Search the site

Links to social media channels

Carbon Offset Deals and the Risks of “Green Grabbing”

Governments must ensure land-based investments for carbon removal respect the access and tenure rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities.

The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) is an award-winning independent think tank working to create a world where people and the planet thrive.

Our research and policy work focuses on areas we deem ripe for transformation, where shifts in policy have the potential to change the game and where we have a proven record of making significant gains.

Address the causes of climate change and adapt to its impact.

Support the sustainable management of our natural resources.

Foster fair and sustainable economies.

Flagship Initiatives

IISD Experimental Lakes Area

IISD Experimental Lakes Area (IISD-ELA) is an exceptional natural laboratory comprised of 58 small lakes and their watersheds set aside for scientific research.

NAP Global Network

The NAP Global Network works with partners in the world’s most vulnerable countries to develop and implement climate adaptation plans for a more secure future.

Global Subsidies Initiative

The IISD Global Subsidies Initiative (GSI) supports international processes, national governments, and civil society organizations to align subsidies with sustainable development.

The Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development

The IGF supports nations committed to leveraging mining for sustainable development to ensure negative impacts are limited and financial benefits are shared.

SDG Knowledge Hub

The SDG Knowledge Hub provides daily information on the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Earth Negotiations Bulletin

Earth Negotiations Bulletin provides balanced, timely, and independent reporting on United Nations environment and development negotiations.

Nature-Based Infrastructure Global Resource Centre

The NBI Global Resource Centre aims to establish the business case for nature-based infrastructure, providing data, training, and customized project valuations.

State of Sustainability Initiatives

The State of Sustainability Initiatives examines how voluntary sustainability standards can support environmental and social goals.

New Research

IISD publishes objective, independent, high-quality research on sustainable development issues, including reports, policy briefs, and toolkits.

The Investment Facilitation for Development Agreement: A reader's guide

A subset of World Trade Organization members has finalized the legal text of an Agreement on Investment Facilitation. This Reader's Guide provides an overview of what's in the agreement.

February 6, 2024

Public Engagement on Climate Change Adaptation

This report provides an introduction to public engagement on climate change adaptation for decision-makers involved in leading national adaptation plan (NAP) processes.

October 3, 2023

New Perspectives

Moving Beyond GDP in the Caribbean

Growth in GDP in the Caribbean isn't capturing the full story of natural disasters, climate change, and social disruption—but action is already underway to move beyond GDP.

February 1, 2024

What Is the UAE Framework for Global Climate Resilience, and How Can Countries Move It Forward?

With the introduction of the new framework for the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), COP 28 marked a milestone for adaptation. We unpack key outputs and set out how countries can move forward by strengthening their national monitoring, evaluation, and learning (MEL) systems.

February 15, 2024

What's Next After COP 28: Food systems

Slated to be a game changer for food systems transformation, COP 28 ended with mixed results. Our expert unpacks the wins and disappointments for food systems and what’s needed next.

December 19, 2023

Stay connected

Be the first to hear what's new in sustainable development. Sign up for our bi-weekly updates to receive a curated selection of our latest reports, articles, projects, and upcoming events.

Fueling Change: The journey to end fossil fuel subsidies in Canada

How Canada became the first country in the world to introduce a framework for ending government subsidies to domestic oil and gas companies.

Success story

October 13, 2023

A Global Deal to Tackle Harmful Fisheries Subsidies: A look behind the scenes

In June 2022, World Trade Organization members reached a historic deal tackling harmful fisheries subsidies. We unpack how a global campaign by environmental non-governmental organizations and technical policy and legal advice from trade experts in Geneva helped make a difference.

December 6, 2022

Envisioning Resilience: Bringing underrepresented women's voices into planning for climate change adaptation

Meaningful participation by women who are on the front lines of climate change is essential for gender-responsive, locally led adaptation. However, in many contexts, women remain underrepresented in decision making, from local to national levels.

October 28, 2022

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Impact of the Sustainable Development Goals on the academic research agenda. A scientometric analysis

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Research Institute on Policies for Social Transformation, Universidad Loyola Andalucía, Córdoba, Spain

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Public Policy Observatory, Universidad Autónoma de Chile, Santiago, Chile

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Department of Finance and Accounting, Universidad Loyola Andalucía, Córdoba, Spain

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Social Matters Research Group, Universidad Loyola Andalucía, Córdoba, Spain

- Antonio Sianes,

- Alejandro Vega-Muñoz,

- Pilar Tirado-Valencia,

- Antonio Ariza-Montes

- Published: March 17, 2022

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265409

- Peer Review

- Reader Comments

Today, global challenges such as poverty, inequality, and sustainability are at the core of the academic debate. This centrality has only increased since the transition from the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), whose scope is to shift the world on to a path of resilience focused on promoting sustainable development. The main purpose of this paper is to develop a critical yet comprehensive scientometric analysis of the global academic production on the SDGs, from its approval in 2015 to 2020, conducted using Web of Science (WoS) database. Despite it being a relatively short period of time, scholars have published more than five thousand research papers in the matter, mainly in the fields of green and sustainable sciences. The attained results show how prolific authors and schools of knowledge are emerging, as key topics such as climate change, health and the burden diseases, or the global governance of these issues. However, deeper analyses also show how research gaps exist, persist and, in some cases, are widening. Greater understanding of this body of research is needed, to further strengthen evidence-based policies able to support the implementation of the 2030 Agenda and the achievement of the SDGs.

Citation: Sianes A, Vega-Muñoz A, Tirado-Valencia P, Ariza-Montes A (2022) Impact of the Sustainable Development Goals on the academic research agenda. A scientometric analysis. PLoS ONE 17(3): e0265409. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265409

Editor: Stefano Ghinoi, University of Greenwich, UNITED KINGDOM

Received: September 10, 2021; Accepted: March 1, 2022; Published: March 17, 2022

Copyright: © 2022 Sianes et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: All relevant data are within the manuscript and its Supporting Information files.

Funding: The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

1. Introduction

1.1. from the millennium agenda to the 2030 agenda and the sustainable development goals (sdgs).

To track the origins of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, we must recall the Millennium Agenda, which was the first global plan focused on fighting poverty and its more extreme consequences [ 1 ]. Approved in 2000, its guiding principle was that northern countries should contribute to the development of southern states via Official Development Assistance (ODA) flows. The commitment was to reach 0.7% of donors’ gross domestic product [ 2 ] to reduce poverty by half by 2015. The relative failure to reach this goal and the consolidation of a discourse of segregation between northern and southern countries [ 3 ] opened the door to strong criticism of the Millennium Agenda. Therefore, as 2015 approached, there were widespread calls for a profound reformulation of the system [ 4 ].

The world in 2015 was very different from that in the early 2000s. Globalization had reached every corner of the world, generating development convergence between countries but increasing inequalities within countries [ 5 , 6 ]. Increasing interest in the environmental crisis and other global challenges, such as the relocation of work and migration flows, consolidated a new approach to development and the need of a more encompassed agenda [ 7 ]. This new agenda was conceived after an integrating process that involved representatives from governments, cooperation agencies, nongovernmental organisations, global business, and academia. The willingness of the 2030 Agenda to ‘leave no one behind’ relies on this unprecedented global commitment by the international community [ 8 ].

As a result of this process, in 2015, the United Nations General Assembly formally adopted the document “Transforming our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” [ 9 ], later known as the 2030 Agenda. This new global agenda is an all-comprising strategy that seeks to inform and orient public policies and private interventions in an extensive range of fields, from climate change to smart cities and from labour markets to birth mortality, among many others.

The declared scope of the Agenda is to shift the world on to a path of resilience focused on promoting sustainable development. To do so, the 2030 Agenda operates under the guidance of five principles, formally known as the ‘5 Ps’: people, planet, prosperity, peace, and partnerships [ 10 ]. With these pivotal concepts in mind, the Agenda has established a total of 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 169 specific targets to be pursued in a 15-year period, which reflects the scale and profound ambition of this new Agenda.

The SDGs do not only address what rich countries should do for the poor but rather what all countries should do together for the global well-being of this and future generations [ 4 ]. Thus, the SDGs cover a much broader range of issues than their predecessors, the Millennium Development Goals [ 11 ], and are intended to be universal on the guidance towards a new paradigm of sustainable development that the international community has been demanding since the 1992 Earth Summit [ 7 , 12 , 13 ].

Despite this potential, some criticise their vagueness, weakness, and unambitious character. Fukuda-Parr [ 14 ], see weaknesses on the simplicity of the SDGs, which can lead to a very narrow conception that reduces the integral concept of development. The issue of measurement is also problematic; for some researchers, the quantification of objectives not only reduces their complexity, but leads to them being carried out without considering the interdependencies between the objectives [ 12 , 13 ]. Other authors have identified difficulties associated with specifying some of the less visible, intangible aspects of their qualitative nature such as inclusive development and green growth [ 14 , 15 ]. Finally, Stafford-Smith et al. [ 16 ] state that their successful implementation also requires paying greater attention to the links across sectors, across societal actors and between and among low-, medium-, and high-income countries.

Despite these criticisms, the SDGs have undoubtedly become the framework for what the Brundtland report defined as our common future. Unlike conventional development agendas that focus on a restricted set of dimensions, the SDGs provide a holistic and multidimensional view of development [ 17 ]. In this line, Le Blanc [ 12 ] concludes that the SDGs constitute a system with a global perspective; because they consider the synergies and trade-offs between the different issues involved in sustainable development, and favour comprehensive thinking and policies.

1.2. Towards a categorization of the SDGs

There is an underlying lack of unanimity in the interpretation of the SDGs, which has given rise to alternative approaches that allow categorizing the issues involved in their achievement without losing sight of the integral vision of sustainable development [ 15 , 18 – 23 ]. However, such categorization of the SDGs makes it possible to approach them in a more holistic and integrated way, focusing on the issues that underlie sustainable development and on trying to elucidate their connections.

Among the many systematization proposals, and following the contributions of Hajer et al. [ 19 ], four connected perspectives can strengthen the universal relevance of the SDGs: a) ‘planetary boundaries’ that emphasize the urgency of addressing environmental concerns and calling on governments to take responsibility for global public goods; b) ‘The safe and just operating space’ to highlight the interconnectedness of social and environmental issues and their consequences for the redistribution of wealth and human well-being; c) ‘The energetic society’ that avoids the plundering of energy resources; and d) ‘green competition’ to stimulate innovation and new business practices that limit the consumption of resources.

Planetary boundaries demand international policies that coordinate efforts to avoid overexploitation of the planet [ 24 ]. Issues such as land degradation, deforestation, biodiversity loss and natural resource overexploitation exacerbate poverty and deepen inequalities [ 21 , 25 – 27 ]. These problems are further compounded by the increasing impacts of climate change with clear ramifications for natural systems and societies around the globe [ 21 , 28 ].

A safe and just operating space implies social inclusivity that ensures equity principles for sharing opportunities for development [ 15 , 29 ]. Furthermore, it requires providing equitable access to effective and high-quality preventive and curative care that reduces global health inequalities [ 30 , 31 ] and promotes human well-being. Studies such as that of Kruk et al. [ 32 ] analyse the reforms needed in health systems to reduce mortality and the systemic changes necessary for high-quality care.

An energetic society demands global, regional and local production and consumption patterns as demands for energy and natural resources continue to increase, providing challenges and opportunities for poverty reduction, economic development, sustainability and social cohesion [ 21 ].

Finally, green competition establishes limits to the consumption of resources, engaging both consumers and companies [ 22 ] and redefining the relationship between firms and their suppliers in the supply chain [ 33 ]. These limits must also be introduced into life in cities, fostering a new urban agenda [ 34 , 35 ]. Poor access to opportunities and services offered by urban centres (a function of distance, transport infrastructure and spatial distribution) is a major barrier to improved livelihoods and overall development [ 36 ].

The diversification of development issues has opened the door to a wide range of new realities that must be studied under the guiding principles of the SDGs, which involve scholars from all disciplines. As Saric et al. [ 37 ] claimed, a shift in academic research is needed to contribute to the achievement of the 2030 Agenda. The identification of critical pathways to success based on sound research is needed to inform a whole new set of policies and interventions aimed at rendering the SDGs both possible and feasible [ 38 ].

1.3. The relevance and impact of the SDGs on academic research

In the barely five years since their approval, the SDGs have proven the ability to mobilize the scientific community and offer an opportunity for researchers to bring interdisciplinary knowledge to facilitate the successful implementation of the 2030 Agenda [ 21 ]. The holistic vision of development considered in the SDGs has impacted very diverse fields of knowledge, such as land degradation processes [ 25 , 26 ], health [ 39 ], energy [ 40 ] and tourism [ 41 ], as well as a priori further disciplines such as earth observation [ 42 ] and neurosurgery [ 43 ]. However, more importantly, the inevitable interdependencies, conflicts and linkages between the different SDGs have also emerged in the analyses, highlighting ideas such as the need for systemic thinking that considers the spatial and temporal connectivity of the SDGs, which calls for multidisciplinary knowledge. According to Le Blanc [ 12 ], the identification of the systemic links between the objectives can be a valuable undertaking for the scientific community in the coming years and sustainable development.

Following this line, several scientific studies have tried to model the relationships between the SDGs in an attempt to clarify the synergies between the objectives, demonstrating their holistic nature [ 12 , 17 , 20 , 44 , 45 ]. This knowledge of interdependencies can bring out difficulties and risks, or conversely the drivers, in the implementation of the SDGs, which will facilitate their achievement [ 22 ]. In addition, it will allow proposing more transformative strategies to implement the SDG agenda, since it favours an overall vision that is opposed to the false illusion that global problems can be approached in isolation [ 19 ].

The lack of prioritisation of the SDGs has been one of the issues raised regarding their weakness, which should also be addressed by academics. For example, Gupta and Vegelin [ 15 ] analyse the dangers of inclusive development prioritising economic issues, relegating social or ecological inclusivity to the background, or the relational aspects of inclusivity that guarantee the existence of laws, policies and global rules that favour equal opportunities. Holden et al. [ 46 ] suggest that this prioritisation should be established according to three moral criteria: the satisfaction of human needs, social equity and respect for environmental limits. These principles must be based on ethical values that, according to Burford et al. [ 47 ], constitute the missing pillar of sustainability. In this way, the ethical imperatives of the SDGs and the values implicit in the discourses on sustainable development open up new possibilities for transdisciplinary research in the social sciences [ 46 , 47 ].

Research on SDG indicators has also been relevant in the academic world, as they offer an opportunity to replace conventional progress metrics such as gross domestic product (GDP) with other metrics more consistent with the current paradigm of development and social welfare that takes into account such aspects as gender equality, urban resilience and governance [ 20 , 48 ].

The study of the role of certain development agents, including companies, universities or supranational organisations, also opens up new areas of investigation for researchers. Some studies have shown the enthusiastic acceptance of the SDGs by companies [ 22 , 49 ]. For Bebbington and Unerman [ 50 ], the study of the role of organisations in achieving the SDGs should be centred around three issues: challenging definitions of entity boundaries to understand their full impacts, introducing new conceptual frameworks for analysis of the context within which organisations operate and re-examining the conceptual basis of justice, responsibility and accountability. On the other hand, the academic community has recognized that knowledge and education are two basic pillars for the transition towards sustainable development, so it may also be relevant to study the responsibility of higher education in achieving the SDGs [ 47 , 50 ]. Institutional sustainability and governance processes are issues that should be addressed in greater depth through research [ 47 ].

Finally, some authors have highlighted the role of information technologies (ICT) in achieving the SDGs [ 23 ] and their role in addressing inequality or vulnerability to processes such as financial exclusion [ 51 ], which opens up new avenues for research.

Despite this huge impact of the SDGs on academic research, to the best of our knowledge, an overall analysis of such an impact to understand its profoundness and capillarity is missing in the literature. To date, reviews have focused on the implementation of specific SDGs [ 52 – 61 ], on specific topics and collectives [ 62 – 70 ], on traditional fields of knowledge, now reconsidered in light of the SDGs [ 71 – 73 ] and on contributions from specific regions or countries [ 74 , 75 ]. By relying on scientometric techniques and data mining analyses, this paper collects and analyses the more than 5,000 papers published on the SDGs to pursue this challenging goal and fill this knowledge gap.

This article aims to provide a critical review of the scientific research on SDGs, a concept that has emerged based on multiple streams of thinking and has begun to be consolidated as of 2015. As such, global references on this topic are identified and highlighted to manage pre-existing knowledge to understand relationships among researchers and with SDG dimensions to enhance the presently dispersed understanding of this subject and its areas of further development. A scientometric meta-analysis of publications on SDGs is conducted to achieve this objective. Mainstream journals from the Web of Science (WoS) are used to identify current topics, the most involved journals, the most prolific authors, and the thematic areas around which the current academic SDG debate revolves.

Once Section 1 has revised on the related literature to accomplish the main objective, Section 2 presents the research methodology. Section 3 presents the main results obtained, and Section 4 critically discusses these results. The conclusion and the main limitations of the study are presented in Section 5.

2. Materials and methods

In methodological terms, this research applies scientometrics as a meta-analytical means to study the evolution of documented scientific knowledge on the Sustainable Development Goals [ 76 – 81 ], taking as a secondary source of information academic contributions (i.e. articles, reviews, editorials, etc.) indexed in the Web of Science (WoS). To ensure that only peer-reviewed contributions authored by individual researchers are retrieved and that such publications have a worldwide prestige assessment, all of them should be published on journals indexed in the Journal Citation Report (JCR), either as part of the Sciences Citation Index Expanded or the Social Sciences Citation Index [ 82 – 84 ].

Following the recommendations of previous studies [ 85 ], it was decided to apply the next search vector from 2015 to 2020 to achieve the research objectives TS = (Sustainable NEAR/0 Development NEAR/0 Goals), which allows the extraction of data with 67 fields for each article registered in WoS.

As the first step, to give meaning to subsequent analyses, we tested the presence of exponential growth in the production of documented knowledge that allows a continuous renewal of knowledge [ 76 , 86 ].

As a second action, given the recent nature of the subject studied, it is of interest to map the playing field [ 87 ] using VOSviewer software version 1.6.16 [ 88 ], to know which topics are most addressed in the matter of SDGs. This analysis seeks an approach, both through the concentration of Keyword Plus® [ 89 ] and by analysing the references used as input in the production of knowledge, which can be treated as cocitations, coupling-citations and cross-citations [ 90 ], using the h-index, in citation terms, as discriminant criteria in the selection of articles [ 91 – 93 ]. This methodology will allow us to establish production, impact and relationship metrics [ 80 , 85 , 87 , 94 , 95 ].

Finally, it is of interest to explore the possible concentrations that may arise. Using Lotka’s Law, we estimated the possible prolific authors and their areas of work in SDGs, and using Bradford’s Law, we conducted a search of a possible adjustment to a geometric series of the concentration zones of journals and therefore a potential nucleus where a profuse discussion on SDGs is taking place [ 96 – 100 ].

3.1. Configuration of the academic production on SDGs

The results present a total of 5,281 articles for a period of six years (2015–2020) in 1,135 journals, with over 60% of these documents published in the last two years. The total of articles is distributed among authors affiliated with 7,418 organisations from 181 countries/regions, giving thematic coverage to 183 categories of the Journal Citation Report-Web of Science (JCR-WoS). Table 1 shows the distribution among the top ten JCR-WoS categories, highlighting the prevalence of journals indexed in green and environmental sciences and, thus, in the Science Index-Expanded.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265409.t001

3.2. Existence of research critical mass

Fig 1 shows the regression model for the period 2015–2020, the last year with complete records consolidated in the Web of Science. The results obtained show significant growth in the number of studies on SDGs, with an R 2 adjustment greater than 96%. The exponential nature of the model shows that a ‘critical mass’ is consolidating around the research on this topic, as proposed by the Law of Exponential Growth of Science over Time [ 76 ], which in some way gives meaning to this research and to obtaining derived results.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265409.g001

3.3. Establishment of concentrations

In accordance with Lotka’s Law, 22,336 authors were identified of the 5,281 articles under study. From this author set, 136 (≈sqrt (22,336)) are considered prolific authors with a contribution to nine or more works. However, a second restriction, even more demanding, is to identify those prolific authors who are also prolific in contemporary terms. Although SDG studies are recent, the growth production rates are extremely high. As previously shown, for the period 2015–2020, 64% of the publications are concentrated between 2019–2020. Based on this second restriction, for 3,400 articles of the 5,281 articles published in 2019 and 2020, and a total of 15,120 authors, only eight prolific authors manage to sustain a publication number that equals or exceeds nine articles. These authors are listed and characterized in Table 2 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265409.t002

The analysis shown in Table 2 highlights the University of Washington’s participation in health issues with Murray and Hay (coauthors of eight articles in the period 2019–2020), who are also important in the area of health for the prolific authors Yaya and Bhutta. The environmental SDGs mark a strong presence with Abhilash, Leal-Filho and Kalin. The affiliation of Abhilsash (Banaras Hindu University) is novel, as it is not part of the classic world core in knowledge production that is largely concentrated in the United States and Europe. It is worth noting that other prolific authors belong to nonmainstream knowledge production world areas, such as Russia or Pakistan. Professor Alola also deserves mention; not only is he the only contemporary prolific author producing in the area of economics, but he is also producing knowledge in Turkey.

In the same way, at the journal level, the potential establishment of concentration areas and determination of a deep discussion nucleus are analysed using Bradford’s law.

With a percentage error of 0.6%, between the total journal number and the total journal number estimated by the Bradford series, the database shows a core of 18 journals (2%) where one in three articles published are concentrated (see Table 3 ).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265409.t003

Regarding the number of contributions by journal, Sustainability has the largest number of studies on SDGs, in which 689 (13%) of the 5,281 articles studied are concentrated. The Journal of Cleaner Production, indexed to WoS categories related to Environmental SDGs, is the second most prominent journal, with 2.7% participation of the articles (147). Both journals are followed by the multidisciplinary journal Plos One, with 2.2% of the total dataset. In terms of impact factor, the 60 points of the health journal The Lancet are superlative in the whole, which in the other cases ranges between 2.000 and 7.246. As shown in Table 4 , we have developed a “Prominence ranking” by weighting article production by impact factor. This metric shows The Lancet, with only 40 articles on SDGs, as the most relevant journal, followed by Sustainability, which becomes relevant due to the high number of publications (689) despite an impact factor of 2.576. These journals are followed by the Journal of Cleaner Production with 147 articles and an impact factor of 7.246.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265409.t004

3.4. Thematic coverage

Concerning the thematic coverage, Fig 2A and 2B show a diversity of 7,003 Keyword Plus® (KWP), consistently connected to a total of 7,141 KWP assigned by Clarivate as metadata to the set of 5,281 articles studied, which presents a strong concentration in a small number of terms (red colour in the heat map generated with VOSviewer version 1.6.16).

a) Keywords Plus® heatmap and b) heat map zoom to highlight the highest concentration words, data source WoS, 2020.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265409.g002

Based on this result, a concentration sphere with 85 KWP (= sqrt (7,141)) is established according to Zipf’s Law, which is presented in 50 or more articles out of the total of 5,281. Moreover, a central concentration sphere of 9 KWPs (= sqrt (85)) can be found, with keywords present in a range of 178 to 346 articles out of a total of 5,281. These nine pivotal keywords are all connected in terms of co-occurrence (associated by Clarivate two or more to the same article) and within papers with an average number of citations in WoS that vary from 9.27 to 16.69, as shown in Table 5 . The nine most prominent key words in relation to the study of the SDGs are health, climate change, management, impact, challenges, governance, systems, policy and framework. These terms already suggest some of the themes around which the debate and research in this area revolves.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265409.t005

The prominence of these keywords is obtained by combining the level of occurrence and average citations (see Table 5 ): on the one hand, the occurrence or number of articles with which the KWP is associated (e.g., Management, 346) and, on the other hand, the average citations presented by the articles associated with these words (e.g., Framework. 9.27). The final score (prominence) mixes both concepts, given the product of the occurrences and the average citations of each KWP in proportion to the mean values (e.g., (330 * 16.69)/(246 * 11.96) = 1.9).

3.5. Relations within the academic contributions

The coupling-citation analysis using VOSviewer identifies the 5,281 articles under study, of which only those found in the h-index as a whole have been considered (the h-index in the database is 81, as there are 81 articles cited 81 or more times). The bibliographic coupling analysis found consistent connections in only 73 of these articles, gathered in seven clusters. Such clusters and unconnected articles are represented in Fig 3 .

Data source WoS. 2020.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265409.g003

In simple terms, discrimination belonging to one cluster or another depends on the total link number that an article has with the other 80 articles based on the use of the common references. Table 6 specifies the articles belonging to the same publication cluster in relation to Fig 3 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265409.t006

Bibliographic coupling analysis can also be used to link the seven clusters that use common references with the field document title (TI), publication name (SO), Keyword Plus-KWP (ID), and research areas (SC). This allows the identification of the main topics of each cluster. As shown in Table 7 , cluster 1 (red) concerns environmental and public affairs; cluster 2 (green), health; cluster 3 (blue), economics; cluster 4 (yellow), health–the burden of disease; cluster 5 (violet), economics–Kuznets curve; cluster 6 (light blue), energy; and cluster 7 (orange), soil—land.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265409.t007

3.6. Outstanding contributions in the field

The cocitation analysis identified a total of 232,081 references cited by the 5,281 articles under study. It suggests taking as references to review those that present 44 or more occurrences in the database (232,081/5,281). This method results in 34 articles that have been used as main inputs for the scientific production under analysis, cited between 44 and 504 times. A result worth highlighting is that one in three of these documents corresponds to reports from international organisations, such as the United Nations (UN), United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Fund for Population Activities (UNFPA), World Bank Group (WB) or World Health Organization (WHO). However, it is also possible to identify 21 peer-reviewed scientific contributions. These papers are identified in detail in Table 8 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265409.t008

The cocitation analysis yields the degree of relationship of these 21 most cited research articles. It is how such references have been used simultaneously in the same article. Fig 4 displays this information (to help readers, it has also been included in Table 8 , centrality in 21 column).

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265409.g004

According to the relationship level in the most cited article’s selection, the graph ( Fig 3 ) has been clustered in three colours: cluster 1 in red colour groups the highest articles proportion (9) published between 2013 and 2017 in 7 journals. These journals present an impact factor (IF) quite heterogeneous, with values ranging from 2.576 (Sustainability) to 60.39 (Lancet) and indexed in one or more of the following WoS categories: Environmental Sciences (4 journals), Green & Sustainable Science & Technology (4), Environmental Studies (2), Development Studies (1), Medicine, General & Internal (1), Multidisciplinary Sciences (1) and Regional & Urban Planning (1). Three of these articles are cited 130–150 times in the 5,281-article dataset and, at the same time, show a connection centrality of 95–100% with the other 20 articles in the graph, implying a high level of cocitation. The other two clusters group six articles each. The articles of cluster 2 (green colour) are included in a widespread WoS category set: Environmental Sciences (3 journals), Geosciences, Multidisciplinary (2), Ecology (1), Economics (1), Energy & Fuels (1), Environmental Studies (1), Green & Sustainable Science & Technology (1), Materials Science, Multidisciplinary (1), Meteorology & Atmospheric Sciences (1) and Multidisciplinary Sciences (1). The research of Nilsson [ 101 ] was used as a reference in 176 of the 5,281 articles under study, showing a centrality of 100%. This great connection level is also featured in another less cited article [ 17 ] published in Earth’s Future. Finally, cluster 3 (blue) highlights six articles concentrated in three highly cited journals in the WoS categories: Medicine, General & Internal (Lancet) and Multidisciplinary Sciences (Nature and Science), whose IFs range from 41.9 to 60.4. In general, they are articles less connected (cocited) to the set of 21, with centralities of 30–90%. Two of these articles were referenced 140 times or more, although one was published in 2009. Thus, cluster 3 concentrates the references mainly in journals on environmental issues with scientific-technological orientation, as well as classic and high-impact WoS journals (The Lancet, Nature and Science). It is worth noting that some of these top journals may not be listed in Table 4 as they are not included in the Bradford’s nucleus, due to their comparatively low number of contributions published.

Finally, continuing with the thematic study, a cross-citation analysis was developed. Considering only the 81 articles that are part of the h-index of the total set of 5,821 articles under study, the citations that are presented among this elite article set are explored using VosViewer. The cross-citation analysis detects existing relationships between 37 of these 81 articles. Once the directionality of the citations has been analysed, a directed temporal graph is generated using Pajek 64 version 5.09, which is presented in Fig 5 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265409.g005

Fig 5 shows how these 37 highly cited articles are related to each other (the number after the name is the publication year), considering that some of these articles are cited as references in other articles in this set. The relationships between the articles in Fig 5 are complex and should be understood under a temporal sequence logic in the citation between two articles. However, some trends can be highlighted.

On the one hand, some contributions stand out for their centrality. Lim et al. [ 102 ] is connected with eight of the 37 articles (21.6%) on citing relationships, as is Fullman et al. [ 27 ], which relates to seven of the 37 articles (18.9%). Both authors researched health issues and are also coauthors of nine articles of the dataset under study. On the other hand, according to the SDG segmentation proposed, Hajer et al. [ 19 ] and Le Blanc [ 12 ] are recognized as seminal articles in social SDGs, since they contribute to the production of other subsequent articles in the set of 37. On the other hand, in health matters, seminal articles are Norheim et al. [ 103 ] and You et al. [ 104 ], two articles published in The Lancet whose citations also contribute to the production of the set introduced as Fig 5 .

4. Discussion

The main purpose of this paper was to develop a critical and comprehensive scientometric analysis of the global academic literature on the SDGs from 2015 to 2020, conducted using the WoS database. The attained results have made it possible to comprehend and communicate to the scientific community the current state of the debate on the SDGs, thus offering insights for future lines of research.

To achieve the objectives, the present study analysed a broad spectrum of 5,281 articles published in 1,135 WoS journals. A first aspect that is striking is the great diversity of topics addressed in these studies, which reflects the multidimensionality of the SDGs. Despite this, more than half of the articles are concentrated in two JCR-WoS categories (Environmental Sciences and Green Sustainable Science Technology), a percentage that exceeds 80% if the categories Environmental Studies and Public Environmental Occupational Health are added. Thus, on the one hand, the size of the body of literature and the broad spectrum of topics more than covers the four perspectives of analysis that are relevant in research on the SDGs, according to Hajer et al. [ 19 ]: planetary boundaries, the safe and just operating space, the energetic society and, last, green competition. However, on the other hand, results also highlight a strong focus on the environmental aspects of the SDGs, which undoubtedly concentrate the most contributions.

The Sustainable Development Goals constitute an area of research that has experienced exponential scientific growth, a tendency already suggested by previous studies [ 81 , 105 ], thus complying with the fundamental principles of Price’s law [ 76 ], which suggests the need for this exponential growth to manifest a continuous renewal of knowledge on the subject under study. The results of this study highlight a significant increase in the number of articles published in the last two years, given that six out of ten articles were published in 2019 or 2020. This tendency confirms how the SDGs continue to arouse great interest in the scientific community and that the debate on the interpretation of sustainable development is still open and very present in academia.

The variety of knowledge areas from which science can approach the SDGs demonstrates the different avenues that exist to address different research questions and their multidimensional nature, as anticipated by Pradhan et al. [ 17 ], a dispersion not far from the traditional fields of knowledge or the conventional dimensions of sustainability. Investigating the reasons for this dispersion in academic research on the SDGs may be a topic of great interest, as anticipated by Burford et al. [ 47 ] and Le Blanc [ 12 ], since understanding the phenomenon of development can only be achieved if the main challenges, both current and future, can be viewed holistically and comprehensively. Along these lines, Imaz and Eizagirre [ 106 ] state that the complexity of the study of the SDGs is undoubtedly marked by their aspiration for universality, by their broad scope encompassing the three basic pillars of sustainable development (economic development, environmental sustainability and social inclusion) and by their desire for integration, motivated by the complexity of the challenges and by the countless interlinkages and interdependencies.

This natural multidimensionality of the SDGs calls for strong cooperation and collaboration between researchers, universities, and countries. In this sense, the scientometric analysis provides good news, as more than a hundred prolific authors (defined as those authors who have published nine or more articles on this topic) have been identified, although these are reduced to eight in contemporary terms (2019 or 2020). This select group of eight authors who lead research and publishing on the SDGs (sometimes with dual or triple affiliations) produce knowledge for universities and research centres both in the global north and the global south: Canada, the U.S., the UK, Germany, Pakistan, Turkey, India, Benin, Russia and Cyprus. The protagonist role played by research institutes in countries in the north has already been acknowledged by previous studies [ 81 , 105 ]. However, the emergence of top scholars producing academic knowledge from developing countries is a more recent tendency, which underscores the pertinence of this analysis.

A closer look at the academic and research curricula of these authors leads to the conclusion that the study of the SDGs does not constitute a final field of research at present. These researchers come from very heterogeneous disciplines, so their approach to the SDGs is also multidisciplinary. To illustrate it with an example, the most cited article by Professor Abhilash of Banaras Hindu University (the most published contemporary prolific author along with Christopher Murray of the University of Washington), with 363 WoS citations in February 2021 alone, is on the use and application of pesticides in India.

In more concrete terms, following Wu et al.’s [ 23 ] classification as a frame of reference, the eight most prolific contemporary authors approach the SDG research problem from two main domains, one of an environmental nature (Abhilash, Leal-Filho, Alola and Kalin) and the other related to health (Murray, Yaya, Bhutta, and Hay). The most common journals where these authors publish on environmental issues are the Journal of Cleaner Production, Higher Education, Water and Science of the Total Environment. Health researchers, on the other hand, tend to publish mainly in the journals of the BMC group, The Lancet and Nature.

This wide diversity of academic fora can be clarified with the application of Bradford’s laws, which identified a core of 18 journals that bring together the debates and academic discussions about the SDGs. It is worth noting that the 18 journals that form the core are distributed in 16 different thematic areas or WoS categories: Development Studies; Ecology; Economics; Education & Educational Research; Engineering, Environmental; Environmental Sciences; Environmental Studies; Green & Sustainable Science & Technology; Hospitality, Leisure, Sport & Tourism; International Relations; Medicine, General & Internal; Multidisciplinary Sciences; Public, Environmental & Occupational Health; Regional & Urban Planning; and Water Resources. On the one hand, this wide dispersion in terms of areas of knowledge suggests that research on the SDGs can be studied from different approaches and disciplines, which opens up a wide range of possibilities for researchers from different branches of scientific knowledge, as well as an opportunity for multidisciplinary collaborations. On the other hand, this heterogeneity might also hinder the communication and dissemination of learning from one field to another. The cross-citation analysis provided in Fig 5 suggests this possibility, as seminal works are related to thematic disciplines more than to the seminal contributions identified in Table 8 .

In this sense, it is interesting to analyse the top-cited articles in the database, as they provide a clear picture of the field of knowledge. One-third of these contributions are provided by international institutions, such as the United Nations Development Program or the World Bank, which provide analyses of a normative nature. This prevalence reflects some weaknesses in the academic basis of the analysis of the SDGs as a whole from a scientific approach, an idea reinforced when the most cited papers are analysed. In fact, only six papers have reached more than 100 citations by contributions included in the database [ 4 , 12 , 24 , 29 , 101 , 107 ]. Not only were these papers largely published before the approval of the SDGs themselves, but half of them are editorial material, inviting contributions but are not evidence-based research papers. Highlighting the nature of the most cited contributions does not diminish their value but does speak to the normative approach that underlies the analysis of the SDGs when addressed not individually but as an overall field of research.

Regarding topics and themes of interest, the scientometric analysis carried out in this research identified a strong concentration around a small number of terms, as represented in a heat map ( Fig 2A and 2B ). All these topics constitute a potential source of inspiration for future research on the subject.

Through an analysis of the main keywords, it can be seen that the studies focused on the traditional areas of health and climate change. However, these keywords also provide new elements for discussion, as they uncover some other areas of study that have been highlighted by the literature. First, the appearance of the term Management as one of the main keywords reveals the importance that researchers give to the role of business in achieving the SDGs, as already suggested by Scheyvens et al. [ 49 ] and Spangenber [ 22 ]. Second, the need to address new governance processes and to seek global solutions, as suggested by authors such as Sachs [ 4 ], underscore the keywords Governance, Policy and Framework, all aspects deemed crucial for the achievement of the SDGs and the 2030 Agenda [ 108 ]. Finally, other keywords such as Impact, Challenges or Systems are a clear example of the complexity and interdependencies that exist in research on the SDGs, considered an essential aspect by Griggs et al. [ 13 ] or Le Blanc [ 12 ]. The attained results highlight some of the connections between different domains of sustainable development by identifying categories and themes that are highly related in the groupings that emerge from the bibliographic coupling analysis.

In general terms, the holistic vision of development embodied by the SDGs has drawn the attention of very different disciplines, fields and areas of scientific knowledge. However, seven major areas of research have emerged: environmental and public affairs, health, economics, health-burden of disease, economics-Kuznets curve, energy and soil-land. These areas are not far removed from the current paradigm of sustainable development, where poverty or inequality are problems that are not exclusive to developing countries [ 5 , 6 ]. Thus, emerging issues that mainly affect first world countries, including urban planning, the impact of activities such as hospitality, sport or tourism, or education for development, are starting to stand out with increasing intensity, which continues to open new avenues for future research.

In short, the results of the scientometric analysis have provided a systematized overview of the research conducted in relation to the SDGs since the approval of the 2030 Agenda. Among other things, the critical analysis has identified the main trends with respect to the number of publications, the most relevant journals, the most prolific authors, institutions and countries, and the collaborative networks between authors and the research areas at the epicentre of the debate on the SDGs. As Olawumi and Chan [ 105 ] already acknowledged, the power research networks applied to the study of the SDGs offer valuable insights and in-depth understandings not only of key scholars and institutions but also about the state of research fields, emerging trends and salient topics.

Consequently, the results of this work contribute to the systematic analysis of scientific research on the SDGs, which can be of great interest for decision-making at the governmental level (e.g., which research to fund and which not to fund), at the corporate level and at the level of research centres, both public and private. Furthermore, the scientometric analysis carried out may provide clues for academics regarding future lines of research and topics of interest where the debate on the SDGs is currently situated.

5. Conclusions, limitations and future research lines

As could not be otherwise, all research in the field of social sciences has a series of limitations that must be clearly and transparently explained. The two most relevant in this study are the following.

First, although the study of the SDGs is a recent object of research, the rate of publication is growing exponentially, such that scientific knowledge is renewed practically in its entirety every two years. The only articles that escape this scientometric obsolescence are those with a high number of citations (h-index). This circumstance generates a temporal limitation in terms of the conclusions obtained in the present investigation, conclusions that should be revised periodically until the growth of publications stabilizes by adopting a logistic form, as recommended by Sun and Lin [ 109 ].

Second, the articles used as the basis for this research were restricted to those published in the JCR-WoS. This decision was made for two main reasons. On the one hand, the limitation was to eliminate potential distortions that could occur as a result of the constant growth of journals that are incorporated annually into other databases, such as ESCI-WoS (Emerging Sources Citation Index). On the other hand, it is impossible to compare impact indices if integrating other databases such as Scopus.

We are aware of these limitations, which for developing a more selective analysis imply assuming the cost of less coverage in exchange.

Regarding future lines of research, the analysis highlights how the study of the SDGs is failing to balance their economic, social and sustainability components, as it still maintains an overall focus on environmental studies.

This suggests the urgency of increasing studies on social SDGs, key topics on the 2030 Agenda including equity (SDGs 4, 5 and 10), social development (SDGs 11 and 16) and governance (SDG 17). These topics are part of the public discourse and currently a source of social pressure in many latitudes, but they are still research areas that are necessary to deepen.

Economic sustainability studies are more present, but highly concentrated, in health economics, as previously acknowledged by Meschede [ 81 ]. Academic research on the SDGs against poverty (SDG 1) and hunger (SDG 2) has not achieved such a prominent place as health. Even less so, the economics of technological development (SDGs 8 and 9), which are recognized as crucial for economic development.

Finally, the environmental SDGs do not achieve a balance among themselves either. Academic research has prioritized action for climate (SDG 13) and industrial and human consumption, mainly water (SDG 6) and energy (SDG 7). New research should be developed in the area of land (SDG 15), life under the sea (SDG 14) and sustainable production (SDG 12).

Supporting information

S1 dataset..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265409.s001

- View Article

- PubMed/NCBI

- Google Scholar

- 9. Nations United. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York, NY, USA: United Nations; 2015.

- Open supplemental data

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, unveiling the research landscape of sustainable development goals and their inclusion in higher education institutions and research centers: major trends in 2000–2017.

- 1 Department of Industrial Management, Industrial Design and Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering and Sustainable Development, University of Gävle, Gävle, Sweden

- 2 Department of Biology, Centre for Environmental and Marine Studies (CESAM), Centre for Environmental and Marine Studies, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal

- 3 Polytechnic Institute of Leiria, Leiria, Portugal

- 4 Life Quality Research Centre, Polytechnic Institute of Santarém, Santarém, Portugal

- 5 Centre for Science and Technology Studies (CWTS), Leiden University, Leiden, Netherlands

- 6 Department of Science and Innovation-National Research Foundation of South Africa Centre of Excellence in Scientometrics and STI Policy (SciSTP), Stellenbosch University, Stellenbosch, South Africa

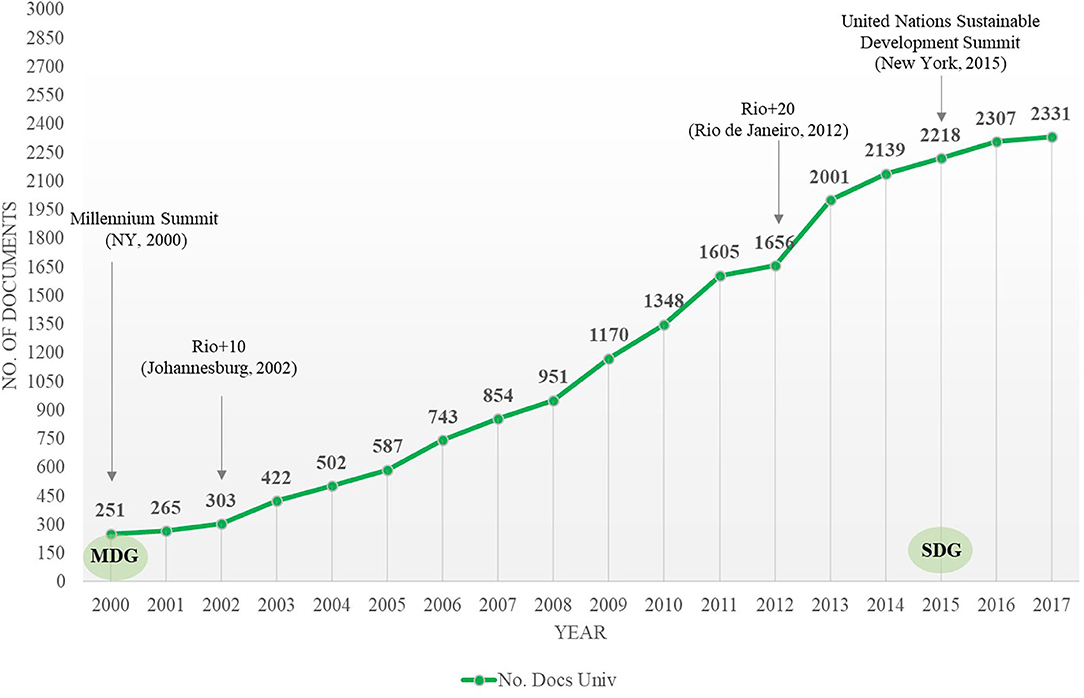

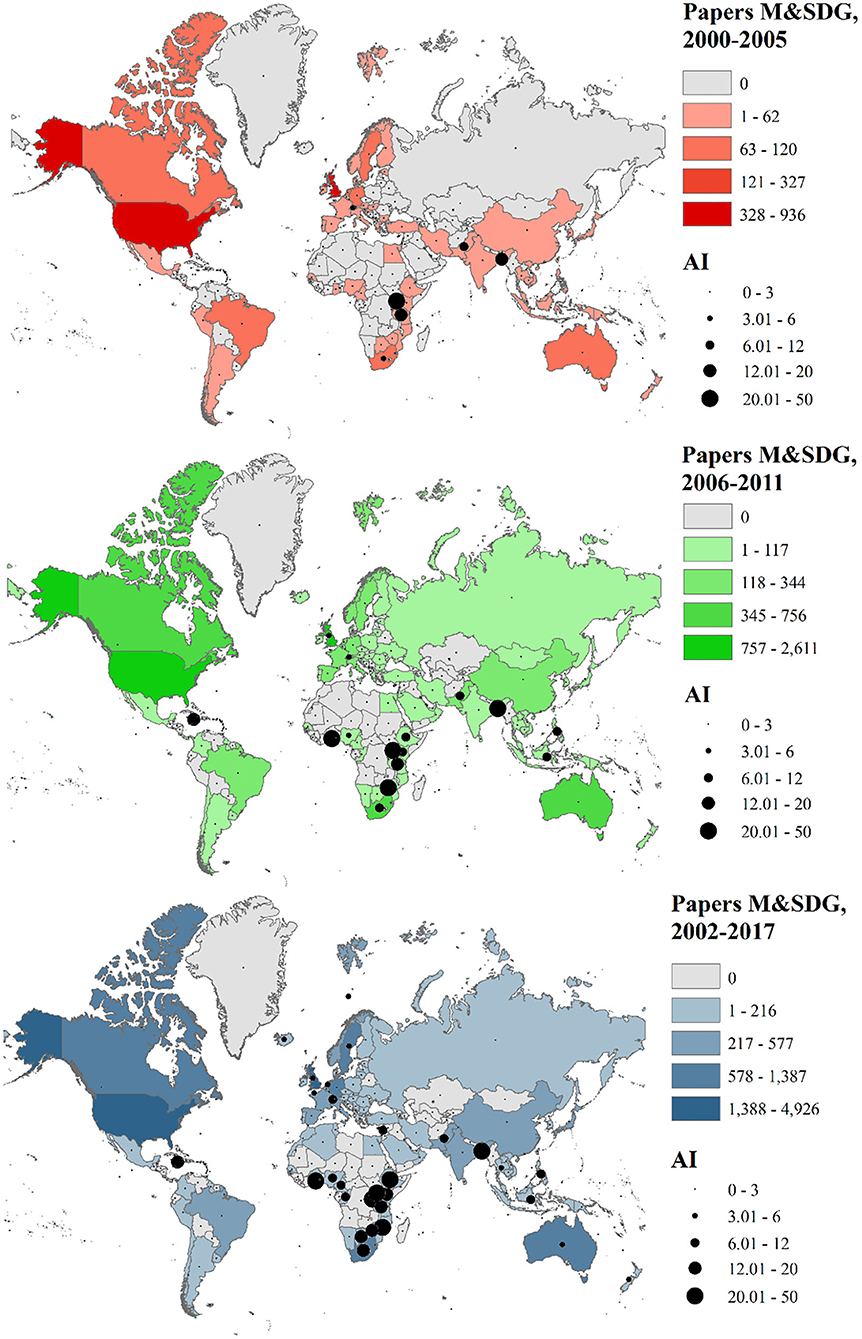

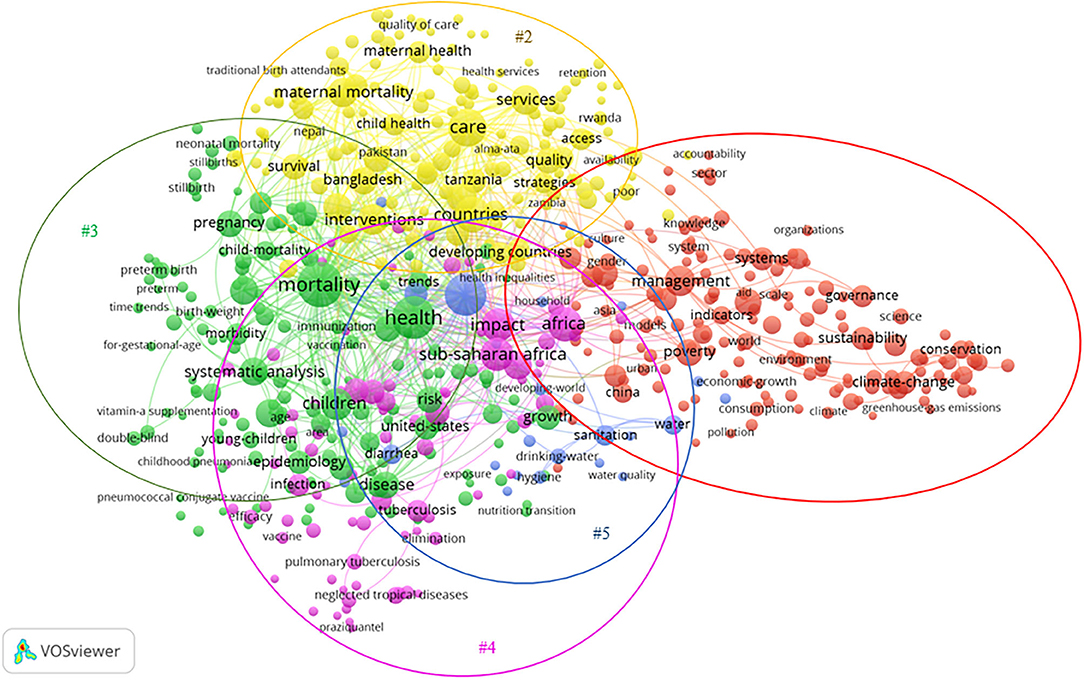

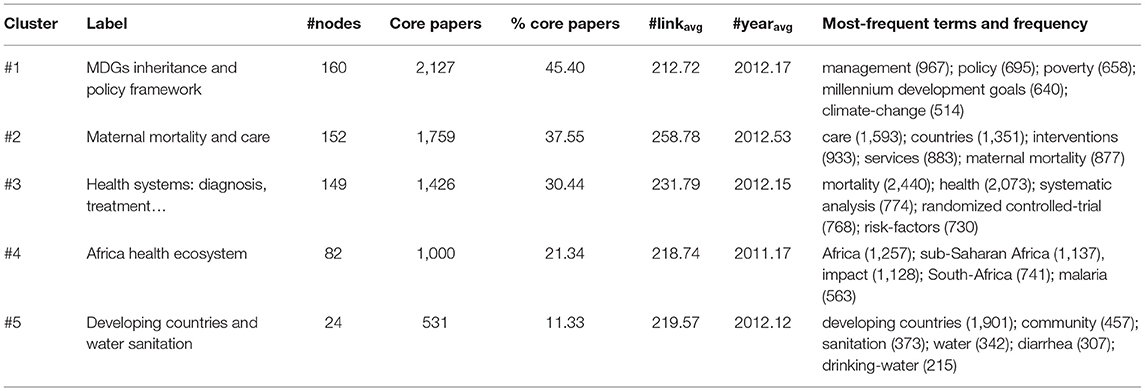

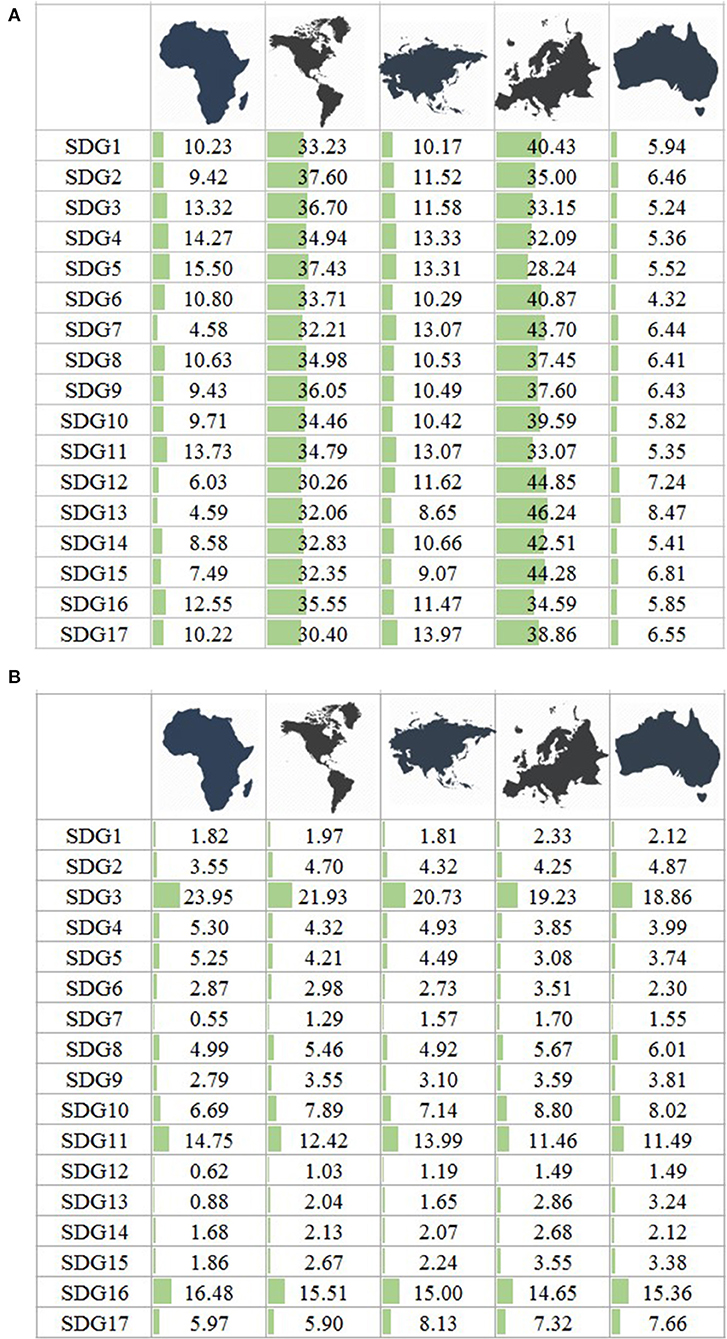

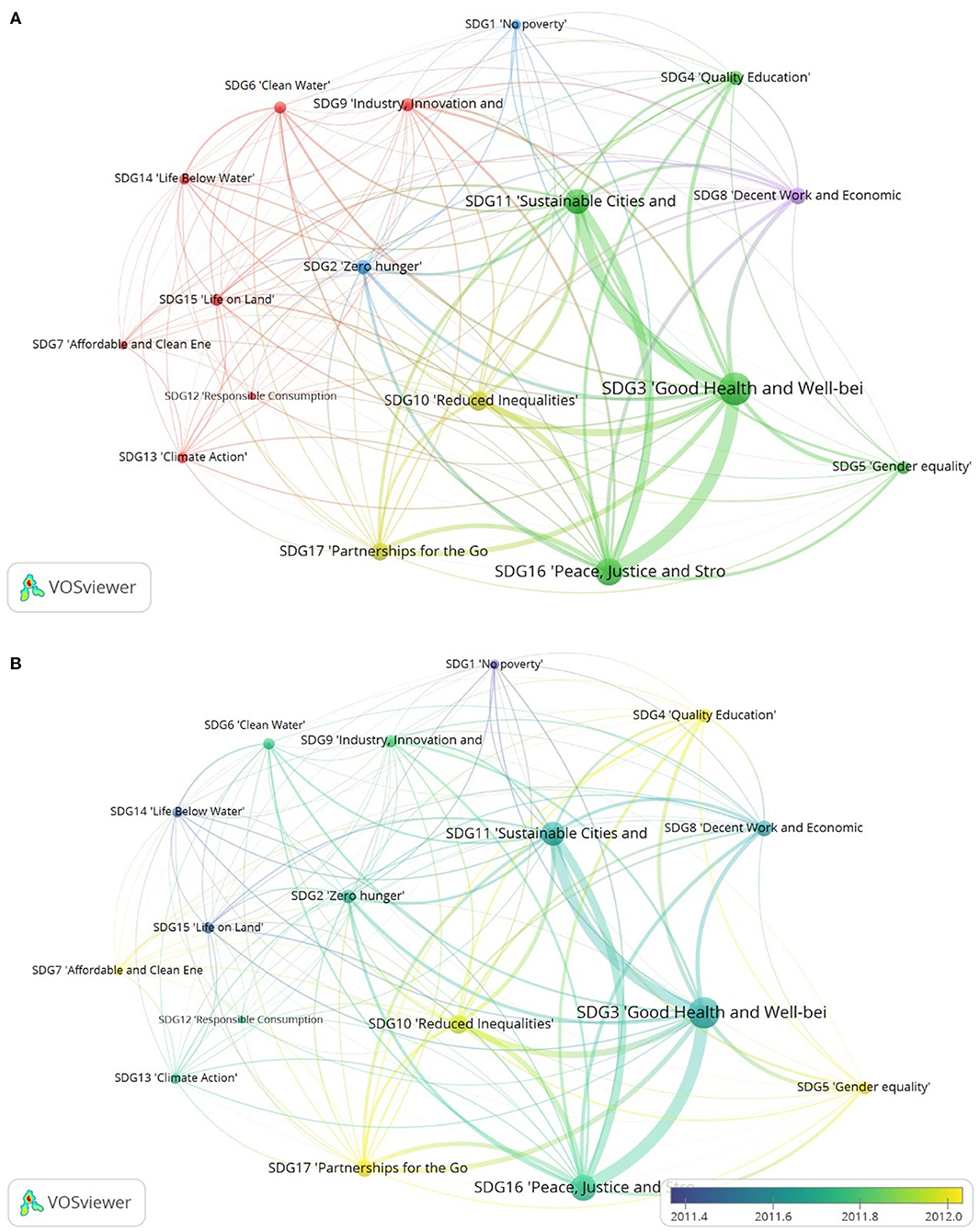

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) have become the international framework for sustainability policy. Its legacy is linked with the Millennium Development Goals (MDG), established in 2000. In this paper a scientometric analysis was conducted to: (1) Present a new methodological approach to identify the research output related to both SDGs and MDGs (M&SDGs) from 2000 to 2017, with the aim of mapping the global research related to M&SDGs; (2) Describe the thematic specialization based on keyword co-occurrence analysis and citation bursts; and (3) Classify the scientific output into individual SDGs (based on an ad-hoc glossary) and assess SDGs interconnections. Publications conceptually related to M&SDGs (defined by the set of M&SDG core publications and a scientometric expansion based on direct citations) were identified in the in-house CWTS Web of Science database. A total of 25,299 publications were analyzed, of which 21,653 (85.59%) were authored by Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) or academic research centers (RCs). The findings reveal the increasing participation of these organizations in this research (660 institutions in 2000–2005 to 1,744 institutions involved in 2012–2017). Some institutions present both a high production and specialization on M&SDG topics (e.g., London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and World Health Organization); and others with a very high specialization although lower production levels (e.g., Stockholm Environment Institute). Regarding the specific topics of research, health (especially in developing countries), women , and socio-economic issues are the most salient. Moreover, it has been observed an important interlinkage in the research outputs of some SDGs (e.g., SDG11 “Sustainable Cities and Communities” and SDG3 “Good Health and Well-Being”). This study provides first evidence of such interconnections, and the results of this study could be useful for policymakers in order to promote a more evidenced-based setting for their research agendas on SDGs.

Introduction

Increasing awareness-building in sustainable development goals.

Sustainability goals have emerged as a global strategy to solve critical world problems, as a result of the global environmental concerns that started in the 1970s. The origin of the notion of sustainable development can be traced back to its most-recognized milestone in 1987; the definition of Sustainable Development in the Brundtland Report 1 . Afterwards, different summits and conferences were held in which sustainability and sustainable development were the core discussions (e.g., Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro in 1992). During these early years, sustainable development was a guiding principle to bridge the North-South division ( Siegel and Bastos Lima, 2020 ). However, what was meant by development was replete with competing ideas about its essential aims, together with various theories about its achievement ( Fukuda-Parr and McNeill, 2019 ). In this context, development goals became an unprecedented effort to bridge those divides and find common ground “with a set of ideas as the consensus global norm concerning both the ends and the means of development” ( Fukuda-Parr, 2019 ). These development goals (MDGs and SDGs) are designed with the same principles: (1) Statement of a social political priority ( goal ); (2) Time-bound quantitative aspect to be achieved ( target ); and (3) Measurement tools to monitor progress ( indicator ) ( Fukuda-Parr and McNeill, 2019 ). The goals represent international agreements that create narratives and frame debates about the conceptualization of development challenges ( Fukuda-Parr, 2019 ). It can be argued that the influence of these goals on policy, governments, and other societal stakeholders is mainly driven by their compelling discourse.

The First Development Goals: Millennium Development Goals

In 2000 eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were created at the Millennium Summit, with the ambition of their being achieved by 2015. These MDGs tackled topics such as extreme poverty and hunger, child mortality, and maternal health 2 . They represented an unprecedented effort to tackle the needs of the world's poorest countries. However, MDGs were criticized for: (1) Not being adequately aligned “with human rights standards and principles;” (2) Being formulated in a top-down process, only driven by international organizations and developing country governments; (3) Lacking accountability mechanisms; and (4) Omission of important priorities, i.e., inequality ( International Human Rights Instruments, 2008 ; Fukuda-Parr, 2016 , 2019 ). Another criticism of the MDGs was that they had unsuccessful effects in some important regions, such as Africa ( Easterly, 2009 ). Despite these criticisms, although indeed not all goals were achieved by 2015, some progress was acknowledged ( United Nations, 2015a ). For instance, “the number of people living in extreme poverty has declined by more than half since 1990 and the literacy rate among youth aged 15–24 has increased globally, from 83% in 1990 to 91% in 2015” ( Ki-Moon, 2015 ).

The Present: The Sustainable Development Goals

In 2012, the Conference Rio+20 adopted a 15-year plan called Agenda 2030 (2015–2030), targeting sustainable economic growth, social development, and environmental protection ( United Nations, 2015b ). As a result, Agenda 2030 established 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), with a deadline in 2030. This agenda was settled as a normative shift ( Fukuda-Parr and McNeill, 2019 ) and has even been institutionalized as a policy paradigm ( Siegel and Bastos Lima, 2020 ). The agenda has 169 targets and various indicators for monitoring their achievement. The topics of these goals cover five critical areas (the so-called 5 P's); People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace, and Partnership ( United Nations, 2015b ). While MDGs encompassed the notion of development as the North-South project to meet basic needs to end poverty, SDGs reconceptualised development as the “universal aspiration for human progress that is inclusive and sustainable” ( Fukuda-Parr and McNeill, 2019 ). Different from the MDGs, the SDGs pay an increased attention to the interlinkages among different sustainability dimensions and give great attention to inclusiveness ; clearly captured in their motto “No one left behind” ( Siegel and Bastos Lima, 2020 ). In practical terms, SDGs expand with respect to MDGs in: (1) Scope (e.g., there are new goals); (2) Reach (involving developed and developing countries); and (3) Engagement of a larger set of societal actors (e.g., citizen councils) in both their creation and implementation ( Fisher and Fukuda-Parr, 2019 ). However, no specific mechanisms to ensure their applicability across different countries have been settled. One of the main concerns is that SDGs rely on individual countries and the goodwill of their governments on how to pursue and implement each of the goals. In this regard, Siegel and Bastos Lima (2020) pointed out that actual SDG-driven transformations depend on the political context of each country, particularly on how these goals are interpreted and prioritized at the national level. These authors even remarked that despite the very concrete formulation of SDGs, their conceptualization (and we could add, their operationalization ) still leaves room for interpretation. Thus, the pursuing of some specific goals over others by some countries is known as “cherry-picking,” although quite often interpreted as conformity with the whole agenda ( Forestier and Kim, 2020 ). However, the aim of Agenda 2030 and its accomplishment is fundamentally based on the integrative and indivisible nature of the goals ( United Nations, 2015b ), therefore “cherry-picking” should not be an acceptable approach, bringing attention to the relevance of monitoring the engagement and consecution of all SDGs by all countries.

The Role of Monitoring the Achievement of SDGs

In contrast to MDGs, monitoring became a key issue for SDGs. Since the launch of SDGs, an SDG Index 3 has been developed, aiming to evaluate the achievement of each goal across all countries. The SDG index allows identifying priorities for action, support discussions, and debates to identify gaps in the development of the goals. A preliminary set of 330 indicators was introduced in March 2015 ( Hák et al., 2016 ), but only 232 indicators were adopted. This is different from MDGs, in which indicators were only decided on an internal basis 4 . The development of indicators to monitor the achievement of SDGs was based on two parallel processes: (1) Multi-stakeholder public consultation led by the UN General Assembly Open Working Group on SDGs (established in 2013); and (2) Intergovernmental negotiations. Moreover, the indicators developed “come from a mix of official and non-official data sources” (e.g., the World Bank, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, among others), all subjected to an extensive and rigorous data validation process [ Sachs et al., 2018 , 2019 ]. However, it has been argued that the translation of goals into quantitative indicators can “distort” their meaning, since indicators can be reinterpreted or used to create perverse discourses or incentives ( Fukuda-Parr and McNeill, 2019 ).

Interlinkages Among SDGs

Another distinctive aspect of SDGs in contrast to MDGs is the role of the relationships and interlinkages among the different goals. Several studies already analyzed the interlinkages and interdependencies between pairs of SDGs, both across or within SDGs, particularly regarding the effects that achieving one goal may have on the ability to achieve others. Pradhan et al. (2017) analyzed the synergies (i.e., progress in one goal favors progress in another) and trade-offs (progress in one goal hinders progress in another) within and across SDGs. They found that SDG1 “No poverty,” or SDG3 “Good health and Well-being” have synergetic relationships with many goals, while SDG12 “Responsible consumption and production” is associated with trade-offs as it has negative correlations with 10 other goals based on the data pair analysis. Later, Lusseau and Mancini (2019) analyzed how key synergies and trade-offs between SDG goals and targets, based on the World Bank categories data, vary with respect to a country's gross national income (GNI) per capita. They highlighted that SDG10 “Reduce Inequalities,” SDG12 “Responsible Consumption and Production,” and SDG13 “Climate Action” are the most central ones, interacting negatively (according to the negative strength value calculated in their study) with many other SDGs (for example in high-income countries SDG12 and SDG13 are antagonistic, based on the Laplacian graph and the eigenvalue centrality value). These kinds of conflicting relationships between SDGs suggest a need for differentiated policy priorities between countries as they progress toward the 2030 Agenda. Kroll et al. (2019) also analyzed trade-offs and synergies between goals and future trends until 2030 based on the SDG index data. They found positive developments with notable synergies in some goals (i.e., SDGs 1, 3, 7, 8, 9), despite others presenting trade-offs (i.e., SDGs 11, 13). There are also other studies that analyzed these interlinkages from a qualitative perspective ( Singh et al., 2018 ; Fuso Nerini et al., 2019 ; Vinuesa et al., 2020 ). Particularly relevant for this study is that to date, there are no global studies on the interrelations among SDGs related to the research output of Higher Education Institutions to the best of our knowledge, a gap that this study intends to fill.

Development Goals and Their Relationship With Higher Education Institutions and Research Centers

As discussed above, MDGs and SDGs appeared as a result of the interest and commitment of governments of countries from all over the world toward sustainable development. As Caiado et al. (2018) stated, “The SDG agenda calls for a global partnership—at all levels—between all countries and stakeholders who need to work together to achieve the goals and targets, including a broad spectrum of actions such as multinational businesses, local governments, regional and international bodies, and civil societal organizations.” In this regard, Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) and Research Centers (RCs) should play an active and central role in promoting and participating in these new goals.

In the past, HEIs played a role in “transforming societies and serving the greater public good, so there is a societal need for universities to assume responsibility for contributing to sustainable development” ( Waas et al., 2010 ), and HEIs “should be leaders in the search for solutions and alternatives to current environmental problems and agents of change” ( Hesselbarth and Schaltegger, 2014 ). For Bizerril et al. (2018) , the knowledge of sustainability in HEIs should be encouraged worldwide and especially those located in regions with serious social and environmental challenges. In this sense, researchers must discuss how to cooperate and to share knowledge for a sustainable society, and HEIs could respond to sustainability through cooperation. According to Lozano et al. (2015) , HEIs (and in extension, RCs) could tackle sustainable development from the following initiatives: (1) Institutional frameworks (i.e., HEIs commitment with vision, missions, SD office…); (2) Campus operations related to the physical built environment (e.g., energy use and energy efficiency, waste, water and water management); (3) Education (e.g., courses on sustainable development); (4) Research (e.g., research centers, publications, research funding); (5) Outreach and collaboration (e.g., exchange programmes for students in the field of sustainable development); (6) Sustainable development through on-campus experiences; and (7) Assessment and reporting. Despite all these aspects, as Caeiro et al. (2013) study stated, only a few institutions follow a holistic implementation, in which sustainable development is applied in all traditional sustainability dimensions via its inclusion in social, economic, and environmental pillars.

The Role of Scientific Research in the Achievement of SDGs

Scientific research is one of the most relevant dimensions in the effective achievement of SDGs and Agenda 2030. According to Tatalović and Antony (2010) science did not factor strongly in the discussions on how to achieve MDGs goals. However, Leal Filho et al. (2017) see SDGs as an opportunity for scientific research to contribute to the achievement of the goals. For Leal Filho et al. (2018) , development goals are an opportunity to encourage sustainability research through interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary research. Several authors also support the important role of scientific research to achieve SDGs ( Wuelser and Pohl, 2016 ), namely as a way to solve concrete social problems, while sustainability science 5 could support the transition for sustainability. Yet, to our knowledge, no large-scale study has sought to investigate which SDGs are prioritized in the research by HEIs at a global level. The ambition of this study is precisely to fill this gap by providing a global mapping of research topics related to SDGs, identifying who the main contributing HEIs to this research are.

Scientometric Analyses of SDGs-Related Research Outputs From HEIs

Scientometrics is a research area focused on studying research activities (e.g., production, evolution, collaboration, impact, etc.) in order to understand the scientific dynamics across subject areas, institutions, or countries. Scientometric studies offer a powerful tool to generate global pictures of the research activities in a given area. There are different scientometric studies that previously analyzed sustainability, sustainable development or sustainability science based on a keyword search ( Nučič, 2012 ; Schoolman et al., 2012 ; Hassan et al., 2014 ; Kajikawa et al., 2014 ; Pulgarin et al., 2015 ; Ramírez Ríos et al., 2016 ; Olawumi and Chan, 2018 ). Some studies focused on analyzing the output of sustainability in higher education ( Bizerril et al., 2018 ; Veiga Ávila et al., 2018 ; Alejandro-Cruz et al., 2019 ; Hallinger and Chatpinyakoop, 2019 ). However, few studies have specifically analyzed scientific output on SDGs, probably due to the intrinsic difficulty in determining the contributions of science to SDGs ( Armitage et al., 2020 ).

Despite these difficulties, some studies have already tried to analyze the interrelations among SDGs ( Le Blanc, 2015 ; Griggs et al., 2017 ). Körfgen et al. (2018) analyzed the contribution of Austrian universities toward SDGs. Sweileh (2020) analyzed 18,696 publications from Scopus by searching the term “sustainable development goal.” Another study ( Nakamura et al., 2019 ), analyzed 2,800 publications (with an expansion to 10,300), developed topic maps from the publications identified. One of the authors of this paper had already carried out a preliminary scientometric study ( Bautista-Puig and Mauleón, 2019 ) by analyzing the core of scientific publications on MDGs and SDGs ( n = 4,532) in addition to the interrelations between different SDGs from a scientometric point of view. However, to the best of our knowledge, no previous study has approached a large-scale study of MDGs and SDGs relations from a scientometric point of view, considering the role of Higher Education Institutions and Research Centers in the production of research around MDGs and SDGs.

The development of these types of studies is paramount in order to assess and understand their potential limitations and robustness ( Rafols, 2020 ), particularly given the increasing number that are starting to use keyword-based scientometric queries, and machine learning approaches ( Pukelis et al., 2020 ) in order to map the contribution of research to the understanding of SDGs (e.g., Elsevier, OSDG tool, STRINGS Project, Dimensions, Aurora Project), and even their impact (e.g., Times Higher Education SDG Impact indicators). Thus, it is important that different methods and approaches are considered and discussed, particularly highlighting their advantages and limitations. This study aims at contributing also to this debate, as well as to provide scientometric evidence on the main research patterns around SDGs, that can help foster the debate on the role of universities to the SDGs goal.

The main purpose of this article is to produce a quantitative study of the scientific research on development goals during the period 2000–2017. Our ambition is 2-fold, on the one hand to propose a scientometric method based on citation relations that can be used to identify research conceptually related to MDGs and SDGs (henceforth M&SDGs), and on the other hand to identify and analyze the main institutions involved in the development of M&SDGs-related scientific outputs, as well as to characterize the main underlying topics related to M&SDGs research. The scientometric analysis was guided by three main research questions:

- RQ1: How can M&SDGs research can be scientometrically delineated and collected? This question focuses on applying an advanced citation-based approach to determine what M&SDG-related research is.

- RQ2. How has M&SDGs research carried out by HEIs has developed over time? This question seeks to characterize how the production of research outputs on M&SDGs has evolved over time, with a special focus on its main producers (institutions and countries). The unit of analysis of this study is on HEIs and RCs (hereafter HEIs). For the more specific definition of these terms used in this study, the reader is referred to Supplementary Material .

- RQ3: What are the specific M&SDGs research topics that have been studied by HEIs? This question identifies and characterizes the main research topics studied in the scientific literature produced by HEIs, with a special focus on the interrelations among the 17 SDGs based on the ad-hoc glossary developed by Bautista (2019) .

The rest of the article is organized as follows. The next section includes the methods section. This is followed by the results and discussions, providing answers to the research questions. Finally, the last section presents the main conclusions and suggestions for future research.

An important methodological difficulty with the definition of M&SDGs research is the discrepancy between what is research related to M&SDGs and what is research on M&SDGs . “ Research related to M&SDGs” comprises research that is related to concepts, issues or ideas related to the M&SDGs but without necessarily a direct linkage to the M&SDGs core (e.g., an institution doing research related to malaria prior to the official launch of the SDGs). “ Research on M&SDGs” comprises research directly focusing on the concepts, notions and principles of the M&SDGs (e.g., research directly mentioning “Sustainable Development Goal” or citing a paper that does it). In this work we partly incorporate both perspectives. Thus, we consider that a scientific publication is on the M&SDGs if it mentions either the concepts of MDG or SDGS (i.e., core research), or at a minimum cites, or is cited by, the core research. From a conceptual point of view it can be argued that our approach focuses on identifying research conceptually related to the “discourse of development goals,” and more specifically about how this topic has been constructed in the research by HEIs. With this citation-based approach we are providing a focused analysis on the scientific research that has a stronger cognitive 6 alignment with the M&SDGs philosophy and aims, thus avoiding the limitations of semantic approaches (e.g., based on keywords), in which different selections of keywords and terms are possible (and potentially questionable—see Rafols, 2020 ).

The following methodological steps were followed: (1) Formulation of a search strategy to identify the core M&SDGs literature; (2) Expansion of the dataset based on direct citations (cited and citing publications); (3) Data collection refining and information processing; and (4) Development of scientometric indicators.

(1) Formulation of a search strategy to identify the core M&SDGs literature

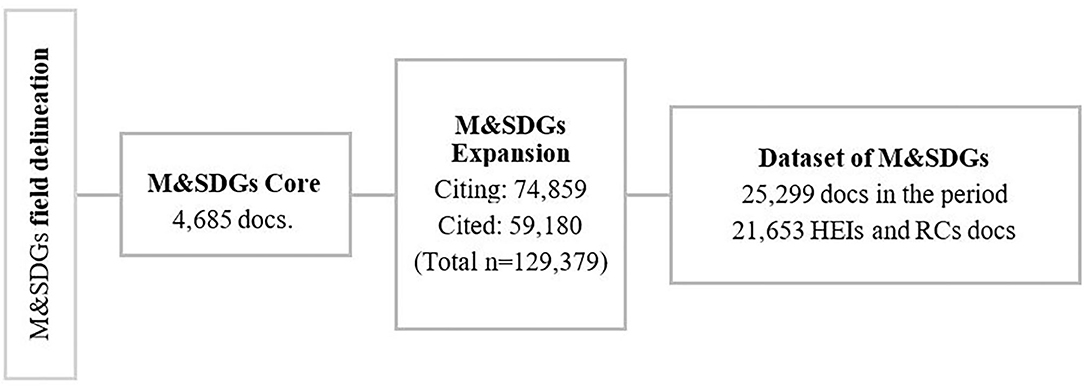

In the first step, we designed a search strategy composed by keywords that unambiguously relate to M&SDGs 7 . These keywords were searched in titles, abstracts, and keywords (author and paper keywords 8 ). The search strategy was run using the in-house CWTS WoS database (limited to publications from the years 2000–2017). A total of 4,685 publications were collected, and all publication types indexed in the Web of Science were considered. These are considered as the M&SDGs core set of publications.

(2) Expansion of the dataset based on direct citations (cited and citing publications)

Starting from the M&SDG core set of publications ( n = 4,685), the set of their direct citations (DC), considering both cited ( n = 59,180) and citing ( n = 74,859) publications were collected, 9 resulting in a final set of distinct publications referred to as M&SDGs Expansion ( n = 129,379).

(3) Data collection refining and affiliation information processing