Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 08 March 2018

Meta-analysis and the science of research synthesis

- Jessica Gurevitch 1 ,

- Julia Koricheva 2 ,

- Shinichi Nakagawa 3 , 4 &

- Gavin Stewart 5

Nature volume 555 , pages 175–182 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

891 Citations

738 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Biodiversity

- Outcomes research

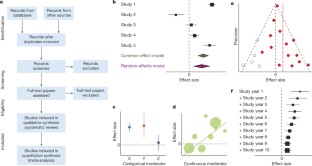

Meta-analysis is the quantitative, scientific synthesis of research results. Since the term and modern approaches to research synthesis were first introduced in the 1970s, meta-analysis has had a revolutionary effect in many scientific fields, helping to establish evidence-based practice and to resolve seemingly contradictory research outcomes. At the same time, its implementation has engendered criticism and controversy, in some cases general and others specific to particular disciplines. Here we take the opportunity provided by the recent fortieth anniversary of meta-analysis to reflect on the accomplishments, limitations, recent advances and directions for future developments in the field of research synthesis.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Testing theory of mind in large language models and humans

Determinants of behaviour and their efficacy as targets of behavioural change interventions

Toolbox of individual-level interventions against online misinformation

Jennions, M. D ., Lortie, C. J. & Koricheva, J. in The Handbook of Meta-analysis in Ecology and Evolution (eds Koricheva, J . et al.) Ch. 23 , 364–380 (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013)

Article Google Scholar

Roberts, P. D ., Stewart, G. B. & Pullin, A. S. Are review articles a reliable source of evidence to support conservation and environmental management? A comparison with medicine. Biol. Conserv. 132 , 409–423 (2006)

Bastian, H ., Glasziou, P . & Chalmers, I. Seventy-five trials and eleven systematic reviews a day: how will we ever keep up? PLoS Med. 7 , e1000326 (2010)

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Borman, G. D. & Grigg, J. A. in The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-analysis 2nd edn (eds Cooper, H. M . et al.) 497–519 (Russell Sage Foundation, 2009)

Ioannidis, J. P. A. The mass production of redundant, misleading, and conflicted systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Milbank Q. 94 , 485–514 (2016)

Koricheva, J . & Gurevitch, J. Uses and misuses of meta-analysis in plant ecology. J. Ecol. 102 , 828–844 (2014)

Littell, J. H . & Shlonsky, A. Making sense of meta-analysis: a critique of “effectiveness of long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy”. Clin. Soc. Work J. 39 , 340–346 (2011)

Morrissey, M. B. Meta-analysis of magnitudes, differences and variation in evolutionary parameters. J. Evol. Biol. 29 , 1882–1904 (2016)

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Whittaker, R. J. Meta-analyses and mega-mistakes: calling time on meta-analysis of the species richness-productivity relationship. Ecology 91 , 2522–2533 (2010)

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Begley, C. G . & Ellis, L. M. Drug development: Raise standards for preclinical cancer research. Nature 483 , 531–533 (2012); clarification 485 , 41 (2012)

Article CAS ADS PubMed Google Scholar

Hillebrand, H . & Cardinale, B. J. A critique for meta-analyses and the productivity-diversity relationship. Ecology 91 , 2545–2549 (2010)

Moher, D . et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6 , e1000097 (2009). This paper provides a consensus regarding the reporting requirements for medical meta-analysis and has been highly influential in ensuring good reporting practice and standardizing language in evidence-based medicine, with further guidance for protocols, individual patient data meta-analyses and animal studies.

Moher, D . et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst. Rev. 4 , 1 (2015)

Nakagawa, S . & Santos, E. S. A. Methodological issues and advances in biological meta-analysis. Evol. Ecol. 26 , 1253–1274 (2012)

Nakagawa, S ., Noble, D. W. A ., Senior, A. M. & Lagisz, M. Meta-evaluation of meta-analysis: ten appraisal questions for biologists. BMC Biol. 15 , 18 (2017)

Hedges, L. & Olkin, I. Statistical Methods for Meta-analysis (Academic Press, 1985)

Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 36 , 1–48 (2010)

Anzures-Cabrera, J . & Higgins, J. P. T. Graphical displays for meta-analysis: an overview with suggestions for practice. Res. Synth. Methods 1 , 66–80 (2010)

Egger, M ., Davey Smith, G ., Schneider, M. & Minder, C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Br. Med. J. 315 , 629–634 (1997)

Article CAS Google Scholar

Duval, S . & Tweedie, R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 56 , 455–463 (2000)

Article CAS MATH PubMed Google Scholar

Leimu, R . & Koricheva, J. Cumulative meta-analysis: a new tool for detection of temporal trends and publication bias in ecology. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 271 , 1961–1966 (2004)

Higgins, J. P. T . & Green, S. (eds) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions : Version 5.1.0 (Wiley, 2011). This large collaborative work provides definitive guidance for the production of systematic reviews in medicine and is of broad interest for methods development outside the medical field.

Lau, J ., Rothstein, H. R . & Stewart, G. B. in The Handbook of Meta-analysis in Ecology and Evolution (eds Koricheva, J . et al.) Ch. 25 , 407–419 (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013)

Lortie, C. J ., Stewart, G ., Rothstein, H. & Lau, J. How to critically read ecological meta-analyses. Res. Synth. Methods 6 , 124–133 (2015)

Murad, M. H . & Montori, V. M. Synthesizing evidence: shifting the focus from individual studies to the body of evidence. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 309 , 2217–2218 (2013)

Rasmussen, S. A ., Chu, S. Y ., Kim, S. Y ., Schmid, C. H . & Lau, J. Maternal obesity and risk of neural tube defects: a meta-analysis. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 198 , 611–619 (2008)

Littell, J. H ., Campbell, M ., Green, S . & Toews, B. Multisystemic therapy for social, emotional, and behavioral problems in youth aged 10–17. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004797.pub4 (2005)

Schmidt, F. L. What do data really mean? Research findings, meta-analysis, and cumulative knowledge in psychology. Am. Psychol. 47 , 1173–1181 (1992)

Button, K. S . et al. Power failure: why small sample size undermines the reliability of neuroscience. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 14 , 365–376 (2013); erratum 14 , 451 (2013)

Parker, T. H . et al. Transparency in ecology and evolution: real problems, real solutions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 31 , 711–719 (2016)

Stewart, G. Meta-analysis in applied ecology. Biol. Lett. 6 , 78–81 (2010)

Sutherland, W. J ., Pullin, A. S ., Dolman, P. M . & Knight, T. M. The need for evidence-based conservation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 19 , 305–308 (2004)

Lowry, E . et al. Biological invasions: a field synopsis, systematic review, and database of the literature. Ecol. Evol. 3 , 182–196 (2013)

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Parmesan, C . & Yohe, G. A globally coherent fingerprint of climate change impacts across natural systems. Nature 421 , 37–42 (2003)

Jennions, M. D ., Lortie, C. J . & Koricheva, J. in The Handbook of Meta-analysis in Ecology and Evolution (eds Koricheva, J . et al.) Ch. 24 , 381–403 (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013)

Balvanera, P . et al. Quantifying the evidence for biodiversity effects on ecosystem functioning and services. Ecol. Lett. 9 , 1146–1156 (2006)

Cardinale, B. J . et al. Effects of biodiversity on the functioning of trophic groups and ecosystems. Nature 443 , 989–992 (2006)

Rey Benayas, J. M ., Newton, A. C ., Diaz, A. & Bullock, J. M. Enhancement of biodiversity and ecosystem services by ecological restoration: a meta-analysis. Science 325 , 1121–1124 (2009)

Article ADS PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Leimu, R ., Mutikainen, P. I. A ., Koricheva, J. & Fischer, M. How general are positive relationships between plant population size, fitness and genetic variation? J. Ecol. 94 , 942–952 (2006)

Hillebrand, H. On the generality of the latitudinal diversity gradient. Am. Nat. 163 , 192–211 (2004)

Gurevitch, J. in The Handbook of Meta-analysis in Ecology and Evolution (eds Koricheva, J . et al.) Ch. 19 , 313–320 (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013)

Rustad, L . et al. A meta-analysis of the response of soil respiration, net nitrogen mineralization, and aboveground plant growth to experimental ecosystem warming. Oecologia 126 , 543–562 (2001)

Adams, D. C. Phylogenetic meta-analysis. Evolution 62 , 567–572 (2008)

Hadfield, J. D . & Nakagawa, S. General quantitative genetic methods for comparative biology: phylogenies, taxonomies and multi-trait models for continuous and categorical characters. J. Evol. Biol. 23 , 494–508 (2010)

Lajeunesse, M. J. Meta-analysis and the comparative phylogenetic method. Am. Nat. 174 , 369–381 (2009)

Rosenberg, M. S ., Adams, D. C . & Gurevitch, J. MetaWin: Statistical Software for Meta-Analysis with Resampling Tests Version 1 (Sinauer Associates, 1997)

Wallace, B. C . et al. OpenMEE: intuitive, open-source software for meta-analysis in ecology and evolutionary biology. Methods Ecol. Evol. 8 , 941–947 (2016)

Gurevitch, J ., Morrison, J. A . & Hedges, L. V. The interaction between competition and predation: a meta-analysis of field experiments. Am. Nat. 155 , 435–453 (2000)

Adams, D. C ., Gurevitch, J . & Rosenberg, M. S. Resampling tests for meta-analysis of ecological data. Ecology 78 , 1277–1283 (1997)

Gurevitch, J . & Hedges, L. V. Statistical issues in ecological meta-analyses. Ecology 80 , 1142–1149 (1999)

Schmid, C. H . & Mengersen, K. in The Handbook of Meta-analysis in Ecology and Evolution (eds Koricheva, J . et al.) Ch. 11 , 145–173 (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013)

Eysenck, H. J. Exercise in mega-silliness. Am. Psychol. 33 , 517 (1978)

Simberloff, D. Rejoinder to: Don’t calculate effect sizes; study ecological effects. Ecol. Lett. 9 , 921–922 (2006)

Cadotte, M. W ., Mehrkens, L. R . & Menge, D. N. L. Gauging the impact of meta-analysis on ecology. Evol. Ecol. 26 , 1153–1167 (2012)

Koricheva, J ., Jennions, M. D. & Lau, J. in The Handbook of Meta-analysis in Ecology and Evolution (eds Koricheva, J . et al.) Ch. 15 , 237–254 (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013)

Lau, J ., Ioannidis, J. P. A ., Terrin, N ., Schmid, C. H . & Olkin, I. The case of the misleading funnel plot. Br. Med. J. 333 , 597–600 (2006)

Vetter, D ., Rucker, G. & Storch, I. Meta-analysis: a need for well-defined usage in ecology and conservation biology. Ecosphere 4 , 1–24 (2013)

Mengersen, K ., Jennions, M. D. & Schmid, C. H. in The Handbook of Meta-analysis in Ecology and Evolution (eds Koricheva, J. et al.) Ch. 16 , 255–283 (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013)

Patsopoulos, N. A ., Analatos, A. A. & Ioannidis, J. P. A. Relative citation impact of various study designs in the health sciences. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 293 , 2362–2366 (2005)

Kueffer, C . et al. Fame, glory and neglect in meta-analyses. Trends Ecol. Evol. 26 , 493–494 (2011)

Cohnstaedt, L. W. & Poland, J. Review Articles: The black-market of scientific currency. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 110 , 90 (2017)

Longo, D. L. & Drazen, J. M. Data sharing. N. Engl. J. Med. 374 , 276–277 (2016)

Gauch, H. G. Scientific Method in Practice (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2003)

Science Staff. Dealing with data: introduction. Challenges and opportunities. Science 331 , 692–693 (2011)

Nosek, B. A . et al. Promoting an open research culture. Science 348 , 1422–1425 (2015)

Article CAS ADS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Stewart, L. A . et al. Preferred reporting items for a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data: the PRISMA-IPD statement. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 313 , 1657–1665 (2015)

Saldanha, I. J . et al. Evaluating Data Abstraction Assistant, a novel software application for data abstraction during systematic reviews: protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Syst. Rev. 5 , 196 (2016)

Tipton, E. & Pustejovsky, J. E. Small-sample adjustments for tests of moderators and model fit using robust variance estimation in meta-regression. J. Educ. Behav. Stat. 40 , 604–634 (2015)

Mengersen, K ., MacNeil, M. A . & Caley, M. J. The potential for meta-analysis to support decision analysis in ecology. Res. Synth. Methods 6 , 111–121 (2015)

Ashby, D. Bayesian statistics in medicine: a 25 year review. Stat. Med. 25 , 3589–3631 (2006)

Article MathSciNet PubMed Google Scholar

Senior, A. M . et al. Heterogeneity in ecological and evolutionary meta-analyses: its magnitude and implications. Ecology 97 , 3293–3299 (2016)

McAuley, L ., Pham, B ., Tugwell, P . & Moher, D. Does the inclusion of grey literature influence estimates of intervention effectiveness reported in meta-analyses? Lancet 356 , 1228–1231 (2000)

Koricheva, J ., Gurevitch, J . & Mengersen, K. (eds) The Handbook of Meta-Analysis in Ecology and Evolution (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013) This book provides the first comprehensive guide to undertaking meta-analyses in ecology and evolution and is also relevant to other fields where heterogeneity is expected, incorporating explicit consideration of the different approaches used in different domains.

Lumley, T. Network meta-analysis for indirect treatment comparisons. Stat. Med. 21 , 2313–2324 (2002)

Zarin, W . et al. Characteristics and knowledge synthesis approach for 456 network meta-analyses: a scoping review. BMC Med. 15 , 3 (2017)

Elliott, J. H . et al. Living systematic reviews: an emerging opportunity to narrow the evidence-practice gap. PLoS Med. 11 , e1001603 (2014)

Vandvik, P. O ., Brignardello-Petersen, R . & Guyatt, G. H. Living cumulative network meta-analysis to reduce waste in research: a paradigmatic shift for systematic reviews? BMC Med. 14 , 59 (2016)

Jarvinen, A. A meta-analytic study of the effects of female age on laying date and clutch size in the Great Tit Parus major and the Pied Flycatcher Ficedula hypoleuca . Ibis 133 , 62–67 (1991)

Arnqvist, G. & Wooster, D. Meta-analysis: synthesizing research findings in ecology and evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 10 , 236–240 (1995)

Hedges, L. V ., Gurevitch, J . & Curtis, P. S. The meta-analysis of response ratios in experimental ecology. Ecology 80 , 1150–1156 (1999)

Gurevitch, J ., Curtis, P. S. & Jones, M. H. Meta-analysis in ecology. Adv. Ecol. Res 32 , 199–247 (2001)

Lajeunesse, M. J. phyloMeta: a program for phylogenetic comparative analyses with meta-analysis. Bioinformatics 27 , 2603–2604 (2011)

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Pearson, K. Report on certain enteric fever inoculation statistics. Br. Med. J. 2 , 1243–1246 (1904)

Fisher, R. A. Statistical Methods for Research Workers (Oliver and Boyd, 1925)

Yates, F. & Cochran, W. G. The analysis of groups of experiments. J. Agric. Sci. 28 , 556–580 (1938)

Cochran, W. G. The combination of estimates from different experiments. Biometrics 10 , 101–129 (1954)

Smith, M. L . & Glass, G. V. Meta-analysis of psychotherapy outcome studies. Am. Psychol. 32 , 752–760 (1977)

Glass, G. V. Meta-analysis at middle age: a personal history. Res. Synth. Methods 6 , 221–231 (2015)

Cooper, H. M ., Hedges, L. V . & Valentine, J. C. (eds) The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-analysis 2nd edn (Russell Sage Foundation, 2009). This book is an important compilation that builds on the ground-breaking first edition to set the standard for best practice in meta-analysis, primarily in the social sciences but with applications to medicine and other fields.

Rosenthal, R. Meta-analytic Procedures for Social Research (Sage, 1991)

Hunter, J. E ., Schmidt, F. L. & Jackson, G. B. Meta-analysis: Cumulating Research Findings Across Studies (Sage, 1982)

Gurevitch, J ., Morrow, L. L ., Wallace, A . & Walsh, J. S. A meta-analysis of competition in field experiments. Am. Nat. 140 , 539–572 (1992). This influential early ecological meta-analysis reports multiple experimental outcomes on a longstanding and controversial topic that introduced a wide range of ecologists to research synthesis methods.

O’Rourke, K. An historical perspective on meta-analysis: dealing quantitatively with varying study results. J. R. Soc. Med. 100 , 579–582 (2007)

Shadish, W. R . & Lecy, J. D. The meta-analytic big bang. Res. Synth. Methods 6 , 246–264 (2015)

Glass, G. V. Primary, secondary, and meta-analysis of research. Educ. Res. 5 , 3–8 (1976)

DerSimonian, R . & Laird, N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control. Clin. Trials 7 , 177–188 (1986)

Lipsey, M. W . & Wilson, D. B. The efficacy of psychological, educational, and behavioral treatment. Confirmation from meta-analysis. Am. Psychol. 48 , 1181–1209 (1993)

Chalmers, I. & Altman, D. G. Systematic Reviews (BMJ Publishing Group, 1995)

Moher, D . et al. Improving the quality of reports of meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials: the QUOROM statement. Quality of reporting of meta-analyses. Lancet 354 , 1896–1900 (1999)

Higgins, J. P. & Thompson, S. G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 21 , 1539–1558 (2002)

Download references

Acknowledgements

We dedicate this Review to the memory of Ingram Olkin and William Shadish, founding members of the Society for Research Synthesis Methodology who made tremendous contributions to the development of meta-analysis and research synthesis and to the supervision of generations of students. We thank L. Lagisz for help in preparing the figures. We are grateful to the Center for Open Science and the Laura and John Arnold Foundation for hosting and funding a workshop, which was the origination of this article. S.N. is supported by Australian Research Council Future Fellowship (FT130100268). J.G. acknowledges funding from the US National Science Foundation (ABI 1262402).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Ecology and Evolution, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, 11794-5245, New York, USA

Jessica Gurevitch

School of Biological Sciences, Royal Holloway University of London, Egham, TW20 0EX, Surrey, UK

Julia Koricheva

Evolution and Ecology Research Centre and School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences, University of New South Wales, Sydney, 2052, New South Wales, Australia

Shinichi Nakagawa

Diabetes and Metabolism Division, Garvan Institute of Medical Research, 384 Victoria Street, Darlinghurst, Sydney, 2010, New South Wales, Australia

School of Natural and Environmental Sciences, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE1 7RU, UK

Gavin Stewart

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed equally in designing the study and writing the manuscript, and so are listed alphabetically.

Corresponding authors

Correspondence to Jessica Gurevitch , Julia Koricheva , Shinichi Nakagawa or Gavin Stewart .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Additional information

Reviewer Information Nature thanks D. Altman, M. Lajeunesse, D. Moher and G. Romero for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

PowerPoint slides

Powerpoint slide for fig. 1, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Gurevitch, J., Koricheva, J., Nakagawa, S. et al. Meta-analysis and the science of research synthesis. Nature 555 , 175–182 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25753

Download citation

Received : 04 March 2017

Accepted : 12 January 2018

Published : 08 March 2018

Issue Date : 08 March 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25753

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Investigate the relationship between the retraction reasons and the quality of methodology in non-cochrane retracted systematic reviews: a systematic review.

- Azita Shahraki-Mohammadi

- Leila Keikha

- Razieh Zahedi

Systematic Reviews (2024)

A meta-analysis on global change drivers and the risk of infectious disease

- Michael B. Mahon

- Alexandra Sack

- Jason R. Rohr

Nature (2024)

Systematic review of the uncertainty of coral reef futures under climate change

- Shannon G. Klein

- Cassandra Roch

- Carlos M. Duarte

Nature Communications (2024)

Meta-analysis reveals weak associations between reef fishes and corals

- Pooventhran Muruga

- Alexandre C. Siqueira

- David R. Bellwood

Nature Ecology & Evolution (2024)

Farming practices to enhance biodiversity across biomes: a systematic review

- Felipe Cozim-Melges

- Raimon Ripoll-Bosch

- Hannah H. E. van Zanten

npj Biodiversity (2024)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

How to Synthesize Written Information from Multiple Sources

Shona McCombes

Content Manager

B.A., English Literature, University of Glasgow

Shona McCombes is the content manager at Scribbr, Netherlands.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

When you write a literature review or essay, you have to go beyond just summarizing the articles you’ve read – you need to synthesize the literature to show how it all fits together (and how your own research fits in).

Synthesizing simply means combining. Instead of summarizing the main points of each source in turn, you put together the ideas and findings of multiple sources in order to make an overall point.

At the most basic level, this involves looking for similarities and differences between your sources. Your synthesis should show the reader where the sources overlap and where they diverge.

Unsynthesized Example

Franz (2008) studied undergraduate online students. He looked at 17 females and 18 males and found that none of them liked APA. According to Franz, the evidence suggested that all students are reluctant to learn citations style. Perez (2010) also studies undergraduate students. She looked at 42 females and 50 males and found that males were significantly more inclined to use citation software ( p < .05). Findings suggest that females might graduate sooner. Goldstein (2012) looked at British undergraduates. Among a sample of 50, all females, all confident in their abilities to cite and were eager to write their dissertations.

Synthesized Example

Studies of undergraduate students reveal conflicting conclusions regarding relationships between advanced scholarly study and citation efficacy. Although Franz (2008) found that no participants enjoyed learning citation style, Goldstein (2012) determined in a larger study that all participants watched felt comfortable citing sources, suggesting that variables among participant and control group populations must be examined more closely. Although Perez (2010) expanded on Franz’s original study with a larger, more diverse sample…

Step 1: Organize your sources

After collecting the relevant literature, you’ve got a lot of information to work through, and no clear idea of how it all fits together.

Before you can start writing, you need to organize your notes in a way that allows you to see the relationships between sources.

One way to begin synthesizing the literature is to put your notes into a table. Depending on your topic and the type of literature you’re dealing with, there are a couple of different ways you can organize this.

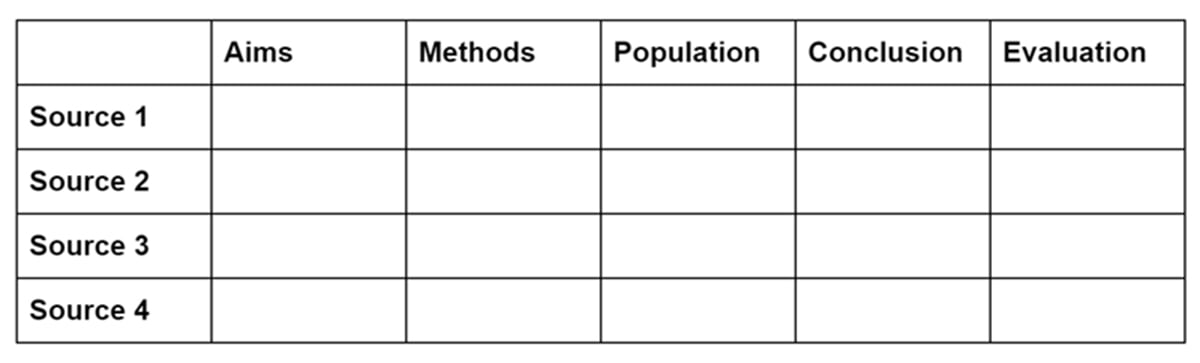

Summary table

A summary table collates the key points of each source under consistent headings. This is a good approach if your sources tend to have a similar structure – for instance, if they’re all empirical papers.

Each row in the table lists one source, and each column identifies a specific part of the source. You can decide which headings to include based on what’s most relevant to the literature you’re dealing with.

For example, you might include columns for things like aims, methods, variables, population, sample size, and conclusion.

For each study, you briefly summarize each of these aspects. You can also include columns for your own evaluation and analysis.

The summary table gives you a quick overview of the key points of each source. This allows you to group sources by relevant similarities, as well as noticing important differences or contradictions in their findings.

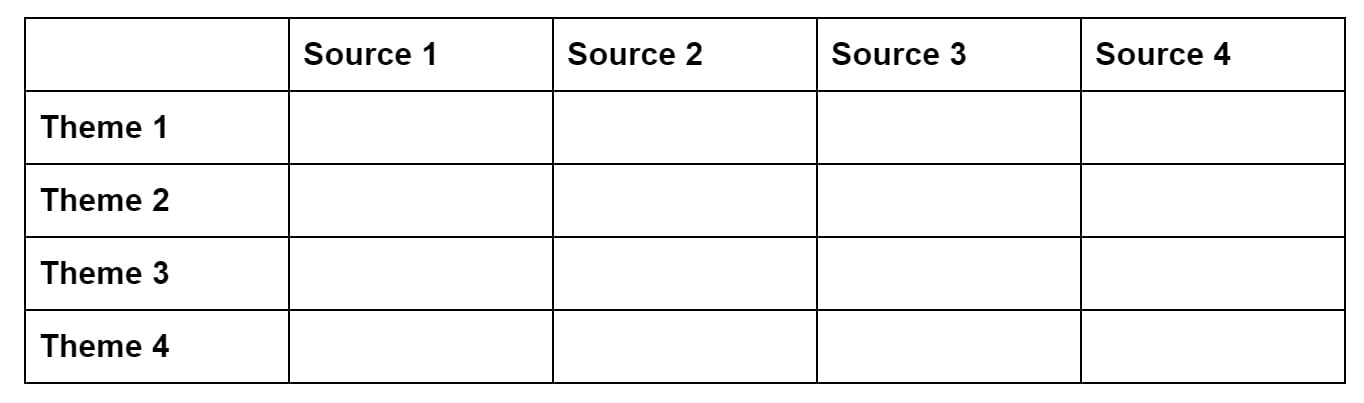

Synthesis matrix

A synthesis matrix is useful when your sources are more varied in their purpose and structure – for example, when you’re dealing with books and essays making various different arguments about a topic.

Each column in the table lists one source. Each row is labeled with a specific concept, topic or theme that recurs across all or most of the sources.

Then, for each source, you summarize the main points or arguments related to the theme.

The purposes of the table is to identify the common points that connect the sources, as well as identifying points where they diverge or disagree.

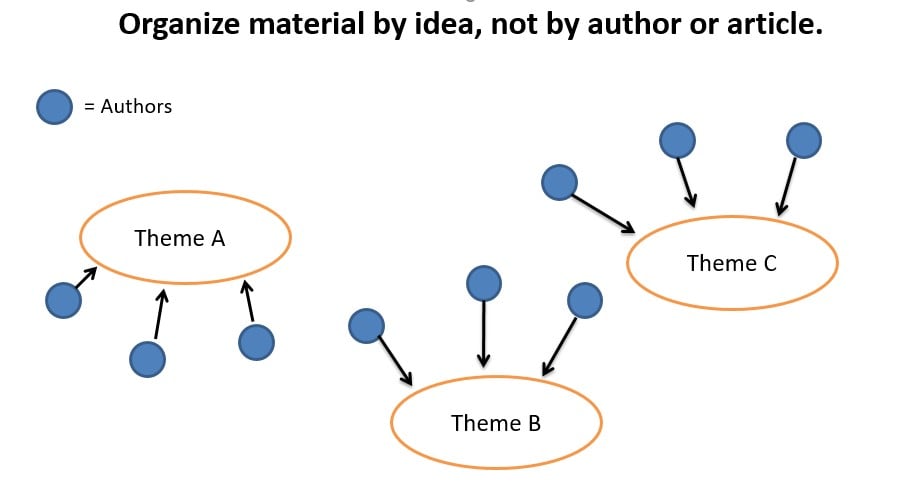

Step 2: Outline your structure

Now you should have a clear overview of the main connections and differences between the sources you’ve read. Next, you need to decide how you’ll group them together and the order in which you’ll discuss them.

For shorter papers, your outline can just identify the focus of each paragraph; for longer papers, you might want to divide it into sections with headings.

There are a few different approaches you can take to help you structure your synthesis.

If your sources cover a broad time period, and you found patterns in how researchers approached the topic over time, you can organize your discussion chronologically .

That doesn’t mean you just summarize each paper in chronological order; instead, you should group articles into time periods and identify what they have in common, as well as signalling important turning points or developments in the literature.

If the literature covers various different topics, you can organize it thematically .

That means that each paragraph or section focuses on a specific theme and explains how that theme is approached in the literature.

Source Used with Permission: The Chicago School

If you’re drawing on literature from various different fields or they use a wide variety of research methods, you can organize your sources methodologically .

That means grouping together studies based on the type of research they did and discussing the findings that emerged from each method.

If your topic involves a debate between different schools of thought, you can organize it theoretically .

That means comparing the different theories that have been developed and grouping together papers based on the position or perspective they take on the topic, as well as evaluating which arguments are most convincing.

Step 3: Write paragraphs with topic sentences

What sets a synthesis apart from a summary is that it combines various sources. The easiest way to think about this is that each paragraph should discuss a few different sources, and you should be able to condense the overall point of the paragraph into one sentence.

This is called a topic sentence , and it usually appears at the start of the paragraph. The topic sentence signals what the whole paragraph is about; every sentence in the paragraph should be clearly related to it.

A topic sentence can be a simple summary of the paragraph’s content:

“Early research on [x] focused heavily on [y].”

For an effective synthesis, you can use topic sentences to link back to the previous paragraph, highlighting a point of debate or critique:

“Several scholars have pointed out the flaws in this approach.” “While recent research has attempted to address the problem, many of these studies have methodological flaws that limit their validity.”

By using topic sentences, you can ensure that your paragraphs are coherent and clearly show the connections between the articles you are discussing.

As you write your paragraphs, avoid quoting directly from sources: use your own words to explain the commonalities and differences that you found in the literature.

Don’t try to cover every single point from every single source – the key to synthesizing is to extract the most important and relevant information and combine it to give your reader an overall picture of the state of knowledge on your topic.

Step 4: Revise, edit and proofread

Like any other piece of academic writing, synthesizing literature doesn’t happen all in one go – it involves redrafting, revising, editing and proofreading your work.

Checklist for Synthesis

- Do I introduce the paragraph with a clear, focused topic sentence?

- Do I discuss more than one source in the paragraph?

- Do I mention only the most relevant findings, rather than describing every part of the studies?

- Do I discuss the similarities or differences between the sources, rather than summarizing each source in turn?

- Do I put the findings or arguments of the sources in my own words?

- Is the paragraph organized around a single idea?

- Is the paragraph directly relevant to my research question or topic?

- Is there a logical transition from this paragraph to the next one?

Further Information

How to Synthesise: a Step-by-Step Approach

Help…I”ve Been Asked to Synthesize!

Learn how to Synthesise (combine information from sources)

How to write a Psychology Essay

Related Articles

Student Resources

How To Cite A YouTube Video In APA Style – With Examples

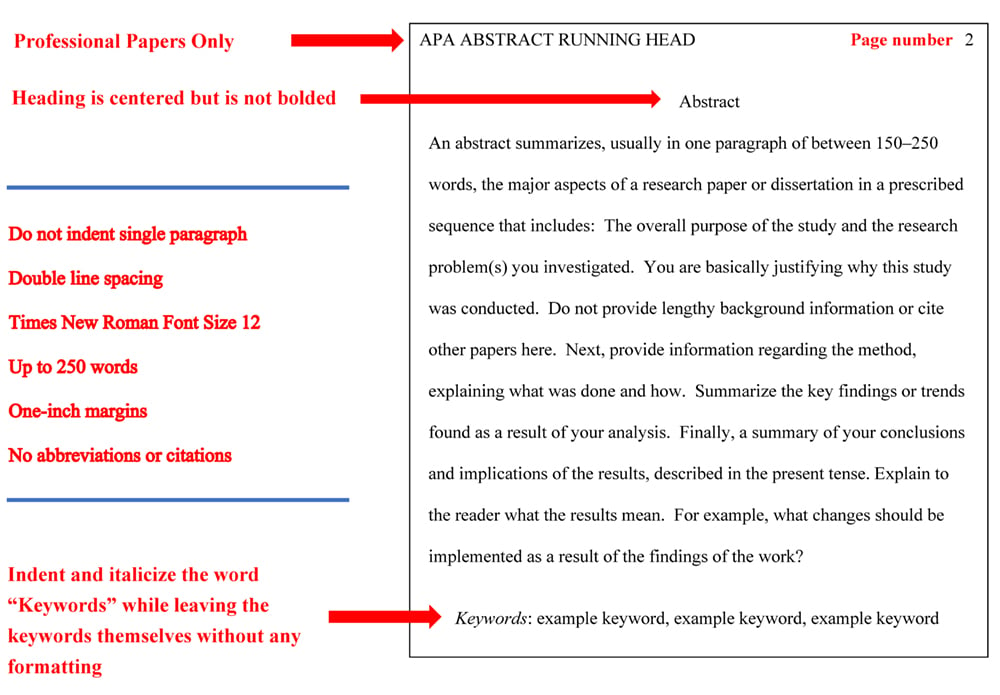

How to Write an Abstract APA Format

APA References Page Formatting and Example

APA Title Page (Cover Page) Format, Example, & Templates

How do I Cite a Source with Multiple Authors in APA Style?

How to Write a Psychology Essay

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Synthesizing Sources

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

When you look for areas where your sources agree or disagree and try to draw broader conclusions about your topic based on what your sources say, you are engaging in synthesis. Writing a research paper usually requires synthesizing the available sources in order to provide new insight or a different perspective into your particular topic (as opposed to simply restating what each individual source says about your research topic).

Note that synthesizing is not the same as summarizing.

- A summary restates the information in one or more sources without providing new insight or reaching new conclusions.

- A synthesis draws on multiple sources to reach a broader conclusion.

There are two types of syntheses: explanatory syntheses and argumentative syntheses . Explanatory syntheses seek to bring sources together to explain a perspective and the reasoning behind it. Argumentative syntheses seek to bring sources together to make an argument. Both types of synthesis involve looking for relationships between sources and drawing conclusions.

In order to successfully synthesize your sources, you might begin by grouping your sources by topic and looking for connections. For example, if you were researching the pros and cons of encouraging healthy eating in children, you would want to separate your sources to find which ones agree with each other and which ones disagree.

After you have a good idea of what your sources are saying, you want to construct your body paragraphs in a way that acknowledges different sources and highlights where you can draw new conclusions.

As you continue synthesizing, here are a few points to remember:

- Don’t force a relationship between sources if there isn’t one. Not all of your sources have to complement one another.

- Do your best to highlight the relationships between sources in very clear ways.

- Don’t ignore any outliers in your research. It’s important to take note of every perspective (even those that disagree with your broader conclusions).

Example Syntheses

Below are two examples of synthesis: one where synthesis is NOT utilized well, and one where it is.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for KidsHealth , encourages parents to be role models for their children by not dieting or vocalizing concerns about their body image. The first popular diet began in 1863. William Banting named it the “Banting” diet after himself, and it consisted of eating fruits, vegetables, meat, and dry wine. Despite the fact that dieting has been around for over a hundred and fifty years, parents should not diet because it hinders children’s understanding of healthy eating.

In this sample paragraph, the paragraph begins with one idea then drastically shifts to another. Rather than comparing the sources, the author simply describes their content. This leads the paragraph to veer in an different direction at the end, and it prevents the paragraph from expressing any strong arguments or conclusions.

An example of a stronger synthesis can be found below.

Parents are always trying to find ways to encourage healthy eating in their children. Different scientists and educators have different strategies for promoting a well-rounded diet while still encouraging body positivity in children. David R. Just and Joseph Price suggest in their article “Using Incentives to Encourage Healthy Eating in Children” that children are more likely to eat fruits and vegetables if they are given a reward (855-856). Similarly, Elena Pearl Ben-Joseph, a doctor and writer for Kids Health , encourages parents to be role models for their children. She states that “parents who are always dieting or complaining about their bodies may foster these same negative feelings in their kids. Try to keep a positive approach about food” (Ben-Joseph). Martha J. Nepper and Weiwen Chai support Ben-Joseph’s suggestions in their article “Parents’ Barriers and Strategies to Promote Healthy Eating among School-age Children.” Nepper and Chai note, “Parents felt that patience, consistency, educating themselves on proper nutrition, and having more healthy foods available in the home were important strategies when developing healthy eating habits for their children.” By following some of these ideas, parents can help their children develop healthy eating habits while still maintaining body positivity.

In this example, the author puts different sources in conversation with one another. Rather than simply describing the content of the sources in order, the author uses transitions (like "similarly") and makes the relationship between the sources evident.

Writing Resources

- Student Paper Template

- Grammar Guidelines

- Punctuation Guidelines

- Writing Guidelines

- Creating a Title

- Outlining and Annotating

- Using Generative AI (Chat GPT and others)

- Introduction, Thesis, and Conclusion

- Strategies for Citations

- Determining the Resource This link opens in a new window

- Citation Examples

- Paragraph Development

- Paraphrasing

- Inclusive Language

- International Center for Academic Integrity

- How to Synthesize and Analyze

- Synthesis and Analysis Practice

- Synthesis and Analysis Group Sessions

- Decoding the Assignment Prompt

- Annotated Bibliography

- Comparative Analysis

- Conducting an Interview

- Infographics

- Office Memo

- Policy Brief

- Poster Presentations

- PowerPoint Presentation

- White Paper

- Writing a Blog

- Research Writing: The 5 Step Approach

- Step 1: Seek Out Evidence

- Step 2: Explain

- Step 3: The Big Picture

- Step 4: Own It

- Step 5: Illustrate

- MLA Resources

- Time Management

ASC Chat Hours

ASC Chat is usually available at the following times ( Pacific Time):

If there is not a coach on duty, submit your question via one of the below methods:

928-440-1325

Ask a Coach

Search our FAQs on the Academic Success Center's Ask a Coach page.

Learning about Synthesis Analysis

What D oes Synthesis and Analysis Mean?

Synthesis: the combination of ideas to

- show commonalities or patterns

Analysis: a detailed examination

- of elements, ideas, or the structure of something

- can be a basis for discussion or interpretation

Synthesis and Analysis: combine and examine ideas to

- show how commonalities, patterns, and elements fit together

- form a unified point for a theory, discussion, or interpretation

- develop an informed evaluation of the idea by presenting several different viewpoints and/or ideas

Key Resource: Synthesis Matrix

Synthesis Matrix

A synthesis matrix is an excellent tool to use to organize sources by theme and to be able to see the similarities and differences as well as any important patterns in the methodology and recommendations for future research. Using a synthesis matrix can assist you not only in synthesizing and analyzing, but it can also aid you in finding a researchable problem and gaps in methodology and/or research.

Use the Synthesis Matrix Template attached below to organize your research by theme and look for patterns in your sources .Use the companion handout, "Types of Articles" to aid you in identifying the different article types for the sources you are using in your matrix. If you have any questions about how to use the synthesis matrix, sign up for the synthesis analysis group session to practice using them with Dr. Sara Northern!

Was this resource helpful?

- << Previous: International Center for Academic Integrity

- Next: How to Synthesize and Analyze >>

- Last Updated: May 22, 2024 5:49 AM

- URL: https://resources.nu.edu/writingresources

Library Guides

Literature reviews: synthesis.

- Criticality

Synthesise Information

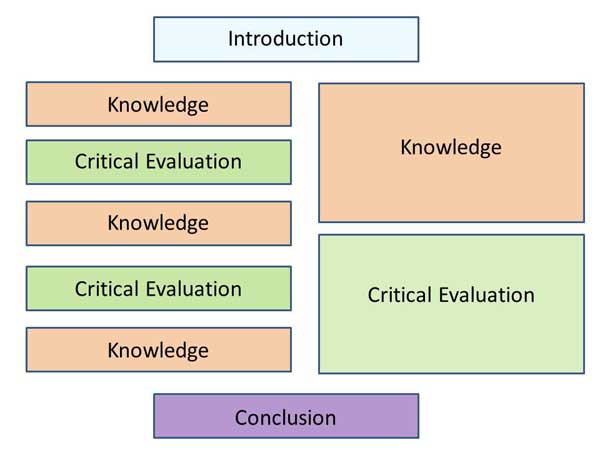

So, how can you create paragraphs within your literature review that demonstrates your knowledge of the scholarship that has been done in your field of study?

You will need to present a synthesis of the texts you read.

Doug Specht, Senior Lecturer at the Westminster School of Media and Communication, explains synthesis for us in the following video:

Synthesising Texts

What is synthesis?

Synthesis is an important element of academic writing, demonstrating comprehension, analysis, evaluation and original creation.

With synthesis you extract content from different sources to create an original text. While paraphrase and summary maintain the structure of the given source(s), with synthesis you create a new structure.

The sources will provide different perspectives and evidence on a topic. They will be put together when agreeing, contrasted when disagreeing. The sources must be referenced.

Perfect your synthesis by showing the flow of your reasoning, expressing critical evaluation of the sources and drawing conclusions.

When you synthesise think of "using strategic thinking to resolve a problem requiring the integration of diverse pieces of information around a structuring theme" (Mateos and Sole 2009, p448).

Synthesis is a complex activity, which requires a high degree of comprehension and active engagement with the subject. As you progress in higher education, so increase the expectations on your abilities to synthesise.

How to synthesise in a literature review:

Identify themes/issues you'd like to discuss in the literature review. Think of an outline.

Read the literature and identify these themes/issues.

Critically analyse the texts asking: how does the text I'm reading relate to the other texts I've read on the same topic? Is it in agreement? Does it differ in its perspective? Is it stronger or weaker? How does it differ (could be scope, methods, year of publication etc.). Draw your conclusions on the state of the literature on the topic.

Start writing your literature review, structuring it according to the outline you planned.

Put together sources stating the same point; contrast sources presenting counter-arguments or different points.

Present your critical analysis.

Always provide the references.

The best synthesis requires a "recursive process" whereby you read the source texts, identify relevant parts, take notes, produce drafts, re-read the source texts, revise your text, re-write... (Mateos and Sole, 2009).

What is good synthesis?

The quality of your synthesis can be assessed considering the following (Mateos and Sole, 2009, p439):

Integration and connection of the information from the source texts around a structuring theme.

Selection of ideas necessary for producing the synthesis.

Appropriateness of the interpretation.

Elaboration of the content.

Example of Synthesis

Original texts (fictitious):

Synthesis:

Animal experimentation is a subject of heated debate. Some argue that painful experiments should be banned. Indeed it has been demonstrated that such experiments make animals suffer physically and psychologically (Chowdhury 2012; Panatta and Hudson 2016). On the other hand, it has been argued that animal experimentation can save human lives and reduce harm on humans (Smith 2008). This argument is only valid for toxicological testing, not for tests that, for example, merely improve the efficacy of a cosmetic (Turner 2015). It can be suggested that animal experimentation should be regulated to only allow toxicological risk assessment, and the suffering to the animals should be minimised.

Bibliography

Mateos, M. and Sole, I. (2009). Synthesising Information from various texts: A Study of Procedures and Products at Different Educational Levels. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 24 (4), 435-451. Available from https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03178760 [Accessed 29 June 2021].

- << Previous: Structure

- Next: Criticality >>

- Last Updated: Nov 18, 2023 10:56 PM

- URL: https://libguides.westminster.ac.uk/literature-reviews

CONNECT WITH US

Literature Syntheis 101

How To Synthesise The Existing Research (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) | August 2023

One of the most common mistakes that students make when writing a literature review is that they err on the side of describing the existing literature rather than providing a critical synthesis of it. In this post, we’ll unpack what exactly synthesis means and show you how to craft a strong literature synthesis using practical examples.

This post is based on our popular online course, Literature Review Bootcamp . In the course, we walk you through the full process of developing a literature review, step by step. If it’s your first time writing a literature review, you definitely want to use this link to get 50% off the course (limited-time offer).

Overview: Literature Synthesis

- What exactly does “synthesis” mean?

- Aspect 1: Agreement

- Aspect 2: Disagreement

- Aspect 3: Key theories

- Aspect 4: Contexts

- Aspect 5: Methodologies

- Bringing it all together

What does “synthesis” actually mean?

As a starting point, let’s quickly define what exactly we mean when we use the term “synthesis” within the context of a literature review.

Simply put, literature synthesis means going beyond just describing what everyone has said and found. Instead, synthesis is about bringing together all the information from various sources to present a cohesive assessment of the current state of knowledge in relation to your study’s research aims and questions .

Put another way, a good synthesis tells the reader exactly where the current research is “at” in terms of the topic you’re interested in – specifically, what’s known , what’s not , and where there’s a need for more research .

So, how do you go about doing this?

Well, there’s no “one right way” when it comes to literature synthesis, but we’ve found that it’s particularly useful to ask yourself five key questions when you’re working on your literature review. Having done so, you can then address them more articulately within your actual write up. So, let’s take a look at each of these questions.

1. Points Of Agreement

The first question that you need to ask yourself is: “Overall, what things seem to be agreed upon by the vast majority of the literature?”

For example, if your research aim is to identify which factors contribute toward job satisfaction, you’ll need to identify which factors are broadly agreed upon and “settled” within the literature. Naturally, there may at times be some lone contrarian that has a radical viewpoint , but, provided that the vast majority of researchers are in agreement, you can put these random outliers to the side. That is, of course, unless your research aims to explore a contrarian viewpoint and there’s a clear justification for doing so.

Identifying what’s broadly agreed upon is an essential starting point for synthesising the literature, because you generally don’t want (or need) to reinvent the wheel or run down a road investigating something that is already well established . So, addressing this question first lays a foundation of “settled” knowledge.

Need a helping hand?

2. Points Of Disagreement

Related to the previous point, but on the other end of the spectrum, is the equally important question: “Where do the disagreements lie?” .

In other words, which things are not well agreed upon by current researchers? It’s important to clarify here that by disagreement, we don’t mean that researchers are (necessarily) fighting over it – just that there are relatively mixed findings within the empirical research , with no firm consensus amongst researchers.

This is a really important question to address as these “disagreements” will often set the stage for the research gap(s). In other words, they provide clues regarding potential opportunities for further research, which your study can then (hopefully) contribute toward filling. If you’re not familiar with the concept of a research gap, be sure to check out our explainer video covering exactly that .

3. Key Theories

The next question you need to ask yourself is: “Which key theories seem to be coming up repeatedly?” .

Within most research spaces, you’ll find that you keep running into a handful of key theories that are referred to over and over again. Apart from identifying these theories, you’ll also need to think about how they’re connected to each other. Specifically, you need to ask yourself:

- Are they all covering the same ground or do they have different focal points or underlying assumptions ?

- Do some of them feed into each other and if so, is there an opportunity to integrate them into a more cohesive theory?

- Do some of them pull in different directions ? If so, why might this be?

- Do all of the theories define the key concepts and variables in the same way, or is there some disconnect? If so, what’s the impact of this ?

Simply put, you’ll need to pay careful attention to the key theories in your research area, as they will need to feature within your theoretical framework , which will form a critical component within your final literature review. This will set the foundation for your entire study, so it’s essential that you be critical in this area of your literature synthesis.

If this sounds a bit fluffy, don’t worry. We deep dive into the theoretical framework (as well as the conceptual framework) and look at practical examples in Literature Review Bootcamp . If you’d like to learn more, take advantage of our limited-time offer to get 60% off the standard price.

4. Contexts

The next question that you need to address in your literature synthesis is an important one, and that is: “Which contexts have (and have not) been covered by the existing research?” .

For example, sticking with our earlier hypothetical topic (factors that impact job satisfaction), you may find that most of the research has focused on white-collar , management-level staff within a primarily Western context, but little has been done on blue-collar workers in an Eastern context. Given the significant socio-cultural differences between these two groups, this is an important observation, as it could present a contextual research gap .

In practical terms, this means that you’ll need to carefully assess the context of each piece of literature that you’re engaging with, especially the empirical research (i.e., studies that have collected and analysed real-world data). Ideally, you should keep notes regarding the context of each study in some sort of catalogue or sheet, so that you can easily make sense of this before you start the writing phase. If you’d like, our free literature catalogue worksheet is a great tool for this task.

5. Methodological Approaches

Last but certainly not least, you need to ask yourself the question: “What types of research methodologies have (and haven’t) been used?”

For example, you might find that most studies have approached the topic using qualitative methods such as interviews and thematic analysis. Alternatively, you might find that most studies have used quantitative methods such as online surveys and statistical analysis.

But why does this matter?

Well, it can run in one of two potential directions . If you find that the vast majority of studies use a specific methodological approach, this could provide you with a firm foundation on which to base your own study’s methodology . In other words, you can use the methodologies of similar studies to inform (and justify) your own study’s research design .

On the other hand, you might argue that the lack of diverse methodological approaches presents a research gap , and therefore your study could contribute toward filling that gap by taking a different approach. For example, taking a qualitative approach to a research area that is typically approached quantitatively. Of course, if you’re going to go against the methodological grain, you’ll need to provide a strong justification for why your proposed approach makes sense. Nevertheless, it is something worth at least considering.

Regardless of which route you opt for, you need to pay careful attention to the methodologies used in the relevant studies and provide at least some discussion about this in your write-up. Again, it’s useful to keep track of this on some sort of spreadsheet or catalogue as you digest each article, so consider grabbing a copy of our free literature catalogue if you don’t have anything in place.

Bringing It All Together

Alright, so we’ve looked at five important questions that you need to ask (and answer) to help you develop a strong synthesis within your literature review. To recap, these are:

- Which things are broadly agreed upon within the current research?

- Which things are the subject of disagreement (or at least, present mixed findings)?

- Which theories seem to be central to your research topic and how do they relate or compare to each other?

- Which contexts have (and haven’t) been covered?

- Which methodological approaches are most common?

Importantly, you’re not just asking yourself these questions for the sake of asking them – they’re not just a reflection exercise. You need to weave your answers to them into your actual literature review when you write it up. How exactly you do this will vary from project to project depending on the structure you opt for, but you’ll still need to address them within your literature review, whichever route you go.

The best approach is to spend some time actually writing out your answers to these questions, as opposed to just thinking about them in your head. Putting your thoughts onto paper really helps you flesh out your thinking . As you do this, don’t just write down the answers – instead, think about what they mean in terms of the research gap you’ll present , as well as the methodological approach you’ll take . Your literature synthesis needs to lay the groundwork for these two things, so it’s essential that you link all of it together in your mind, and of course, on paper.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

You Might Also Like:

excellent , thank you

Thank you for this significant piece of information.

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

The Sheridan Libraries

- Write a Literature Review

- Sheridan Libraries

- Find This link opens in a new window

- Evaluate This link opens in a new window

Get Organized

- Lit Review Prep Use this template to help you evaluate your sources, create article summaries for an annotated bibliography, and a synthesis matrix for your lit review outline.

Synthesize your Information

Synthesize: combine separate elements to form a whole.

Synthesis Matrix

A synthesis matrix helps you record the main points of each source and document how sources relate to each other.

After summarizing and evaluating your sources, arrange them in a matrix or use a citation manager to help you see how they relate to each other and apply to each of your themes or variables.

By arranging your sources by theme or variable, you can see how your sources relate to each other, and can start thinking about how you weave them together to create a narrative.

- Step-by-Step Approach

- Example Matrix from NSCU

- Matrix Template

- << Previous: Summarize

- Next: Integrate >>

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 10:25 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.jhu.edu/lit-review

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Using Evidence: Synthesis

Synthesis video playlist.

Note that these videos were created while APA 6 was the style guide edition in use. There may be some examples of writing that have not been updated to APA 7 guidelines.

Basics of Synthesis

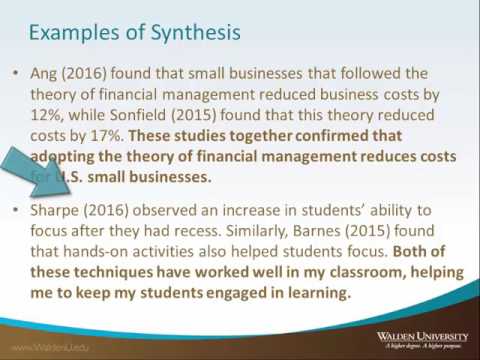

As you incorporate published writing into your own writing, you should aim for synthesis of the material.

Synthesizing requires critical reading and thinking in order to compare different material, highlighting similarities, differences, and connections. When writers synthesize successfully, they present new ideas based on interpretations of other evidence or arguments. You can also think of synthesis as an extension of—or a more complicated form of—analysis. One main difference is that synthesis involves multiple sources, while analysis often focuses on one source.

Conceptually, it can be helpful to think about synthesis existing at both the local (or paragraph) level and the global (or paper) level.

Local Synthesis

Local synthesis occurs at the paragraph level when writers connect individual pieces of evidence from multiple sources to support a paragraph’s main idea and advance a paper’s thesis statement. A common example in academic writing is a scholarly paragraph that includes a main idea, evidence from multiple sources, and analysis of those multiple sources together.

Global Synthesis

Global synthesis occurs at the paper (or, sometimes, section) level when writers connect ideas across paragraphs or sections to create a new narrative whole. A literature review , which can either stand alone or be a section/chapter within a capstone, is a common example of a place where global synthesis is necessary. However, in almost all academic writing, global synthesis is created by and sometimes referred to as good cohesion and flow.

Synthesis in Literature Reviews

While any types of scholarly writing can include synthesis, it is most often discussed in the context of literature reviews. Visit our literature review pages for more information about synthesis in literature reviews.

Related Webinars

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Analysis

- Next Page: Citing Sources Properly

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

- University of Oregon Libraries

- Research Guides

How to Write a Literature Review

- 6. Synthesize

- Literature Reviews: A Recap

- Reading Journal Articles

- Does it Describe a Literature Review?

- 1. Identify the Question

- 2. Review Discipline Styles

- Searching Article Databases

- Finding Full-Text of an Article

- Citation Chaining

- When to Stop Searching

- 4. Manage Your References

- 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

Synthesis Visualization

Synthesis matrix example.

- 7. Write a Literature Review

- Synthesis Worksheet

About Synthesis

Approaches to synthesis.

You can sort the literature in various ways, for example:

How to Begin?

Read your sources carefully and find the main idea(s) of each source

Look for similarities in your sources – which sources are talking about the same main ideas? (for example, sources that discuss the historical background on your topic)

Use the worksheet (above) or synthesis matrix (below) to get organized

This work can be messy. Don't worry if you have to go through a few iterations of the worksheet or matrix as you work on your lit review!

Four Examples of Student Writing

In the four examples below, only ONE shows a good example of synthesis: the fourth column, or Student D . For a web accessible version, click the link below the image.

Long description of "Four Examples of Student Writing" for web accessibility

- Download a copy of the "Four Examples of Student Writing" chart

Click on the example to view the pdf.

From Jennifer Lim

- << Previous: 5. Critically Analyze and Evaluate

- Next: 7. Write a Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: May 3, 2024 5:17 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.uoregon.edu/litreview

Contact Us Library Accessibility UO Libraries Privacy Notices and Procedures

1501 Kincaid Street Eugene, OR 97403 P: 541-346-3053 F: 541-346-3485

- Visit us on Facebook

- Visit us on Twitter

- Visit us on Youtube

- Visit us on Instagram

- Report a Concern

- Nondiscrimination and Title IX

- Accessibility

- Privacy Policy

- Find People

Literature Reviews

- Introduction

- Tutorials and resources

- Step 1: Literature search

- Step 2: Analysis, synthesis, critique

- Step 3: Writing the review

If you need any assistance, please contact the library staff at the Georgia Tech Library Help website .

Analysis, synthesis, critique

Literature reviews build a story. You are telling the story about what you are researching. Therefore, a literature review is a handy way to show that you know what you are talking about. To do this, here are a few important skills you will need.

Skill #1: Analysis

Analysis means that you have carefully read a wide range of the literature on your topic and have understood the main themes, and identified how the literature relates to your own topic. Carefully read and analyze the articles you find in your search, and take notes. Notice the main point of the article, the methodologies used, what conclusions are reached, and what the main themes are. Most bibliographic management tools have capability to keep notes on each article you find, tag them with keywords, and organize into groups.

Skill #2: Synthesis

After you’ve read the literature, you will start to see some themes and categories emerge, some research trends to emerge, to see where scholars agree or disagree, and how works in your chosen field or discipline are related. One way to keep track of this is by using a Synthesis Matrix .

Skill #3: Critique

As you are writing your literature review, you will want to apply a critical eye to the literature you have evaluated and synthesized. Consider the strong arguments you will make contrasted with the potential gaps in previous research. The words that you choose to report your critiques of the literature will be non-neutral. For instance, using a word like “attempted” suggests that a researcher tried something but was not successful. For example:

There were some attempts by Smith (2012) and Jones (2013) to integrate a new methodology in this process.

On the other hand, using a word like “proved” or a phrase like “produced results” evokes a more positive argument. For example:

The new methodologies employed by Blake (2014) produced results that provided further evidence of X.

In your critique, you can point out where you believe there is room for more coverage in a topic, or further exploration in in a sub-topic.

Need more help?

If you are looking for more detailed guidance about writing your dissertation, please contact the folks in the Georgia Tech Communication Center .

- << Previous: Step 1: Literature search

- Next: Step 3: Writing the review >>

- Last Updated: Apr 2, 2024 11:21 AM

- URL: https://libguides.library.gatech.edu/litreview

Advertisement

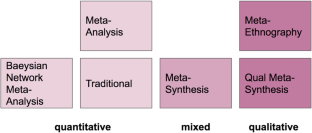

Meta-Analysis and Meta-Synthesis Methodologies: Rigorously Piecing Together Research

- Original Paper

- Published: 18 June 2018

- Volume 62 , pages 525–534, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

- Heather Leary ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2487-578X 1 &

- Andrew Walker 2

5534 Accesses

33 Citations

7 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

For a variety of reasons, education research can be difficult to summarize. Varying contexts, designs, levels of quality, measurement challenges, definition of underlying constructs, and treatments as well as the complexity of research subjects themselves can result in variability. Education research is voluminous and draws on multiple methods including quantitative, as well as, qualitative approaches to answer key research questions. With increased numbers of empirical research in Instructional Design and Technology (IDT), using various synthesis methods can provide a means to more deeply understand trends and patterns in research findings across multiple studies. The purpose of this article is to illustrate structured review or meta-synthesis procedures for qualitative research, as well as, novel meta-analysis procedures for the kinds of multiple treatment designs common to IDT settings. Sample analyses are used to discuss key methodological ideas as a way to introduce researchers to these techniques.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Trends and Issues in Qualitative Research Methods

Educational design research: grappling with methodological fit

Gauging the Effectiveness of Educational Technology Integration in Education: What the Best-Quality Meta-Analyses Tell Us

Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 1 (3), 385–405.

Article Google Scholar

Barnett-Page, E., & Thomas, J. (2009). Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research: a critical review. ESRC National Centre for Research Methods, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, London, 01/09.

Barton, E. E., Pustejovsky, J. E., Maggin, D. M., & Reichow, B. (2017). Technology-aided instruction and intervention for students with ASD: A meta-analysis using novel methods of estimating effect sizes for single-case research. Remedial and Special Education, 38 (6), 371–386.

Beal, C. R., Arroyo, I., Cohen, P. R., & Woolf, B. P. (2010). Evaluation of AnimalWatch: An intelligent tutoring system for arithmetic and fractions. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 9 (1), 64–77.

Google Scholar

Belland, B., Walker, A., Kim, N., & Lefler, M. (2017a). Synthesizing results from empirical research on computer-based scaffolding in STEM education: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 82 (2), 309–344.

Belland, B., Walker, A., & Kim, N. (2017b). A bayesian network meta-analysis to synthesize the influence of contexts of scaffolding use on cognitive outcomes in STEM education. Review of Educational Research, 87 (6), 1042–1081.

Bhatnagar, N., Lakshmi, P. V. M., & Jeyashree, K. (2014). Multiple treatment and indirect treatment comparisons: An overview of network meta-analysis. Perspectives in Clinical Research, 5 (4), 154–158. https://doi.org/10.4103/2229-3485.140550 .

Boote, D. N., & Beile, P. (2005). Scholars before researchers: On the centrality of the dissertation literature review in research preparation. Educational Researcher, 34 (6), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X034006003 .

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2009). Introduction to meta-analysis . Chichester: Wiley.

Book Google Scholar

Bulu, S., & Pedersen, S. (2010). Scaffolding middle school students’ content knowledge and illstructured problem solving in a problem-based hypermedia learning environment. Educational Technology Research & Development, 58 (5), 507–529.

Cooper, H. (2009). Research synthesis and meta-analysis: A step-by-step approach (applied social research methods) . Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Cooper, H. (2016). Research synthesis and meta-analysis: A step-by-step approach (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage publications.

Cooper, H., & Hedges, L. V. (1994). The handbook of research synthesis . New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Finfgeld, D. L. (2003). Metasynthesis: The state of the art - so far. Qualitative Health Research, 13 (7), 893–904.

Finfgeld-Connett, D. (2010). Generalizability and transferability of meta-synthesis research findings. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66 (2), 246–254.

Finfgeld-Connett, D. (2014). Metasynthesis findings: Potential versus reality. Qualitative Health Research, 24 , 1581–1591. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732314548878 .

Finfgeld-Connett, D. (2016). The future of theory-generating meta-synthesis research. Qualitative Health Research, 26 (3), 291–293.

Finlayson, K., & Dixon, A. (2008). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A guide for the novice. Nurse Researcher, 15 (2), 59–71.

Glass, G. V. (1976). Primary, secondary, and meta-analysis of research. Educational Researcher, 5 (10), 3–8.

Glass, G. V. (2000). Meta-analysis at 25 . http://www.gvglass.info/papers/meta25.html

Gurevitch, J., Koricheva, J., Nakagawa, S., & Stewart, G. (2018). Meta-analysis and the science of research synthesis. Nature, 555 , 175–182.

Harden, A. (2010). Mixed-methods systematic reviews: Integrating quantitative and qualitative findings. Focus Technical Brief, 25 , 1–8.

Heller, R. (1990). The role of hypermedia in education: A look at the research issues. Journal of Research on Computing in Education, 22 , 431–441.

Higgins, S. (2016). Meta-synthesis and comparative meta-analysis of education research findings: Some risks and benefits. Review of Education, 4 (1), 31–53.

Higgins, J. P., & Green, S. (2008). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions . Chichester: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470712184 .

Higgins, J. P. T., Altman, D. G., Gøtzsche, P. C., Jüni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A. D., … Sterne, J. (2011). The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 343 . Retrieved from http://www.bmj.com/content/343/bmj.d5928

Karich, A. C., Burns, M. K., & Maki, K. E. (2014). Updated meta-analysis of learner control within educational technology. Review of Educational Research, 84 (3), 392–410.

Lachal, J., Revah-Levy, A., Orri, M., & Moro, M. R. (2017). Metasynthesis: An original method to synthesize qualitative literature. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8 , 1–9.

Lam, S. K. H., & Owen, A. (2007). Combined resynchronisation and implantable defibrillator therapy in left ventricular dysfunction: Bayesian network meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 335 (7626), 925–928.

Leary, H., Shelton, B. E., & Walker, A. (2010). Rich visual media meta-analyses for learning: An approach at meta-synthesis. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association annual meeting, Denver, CO.

Lin, H. (2015). A meta-synthesis of empirical research on the effectiveness of computer-mediated communication (CMC) in SLA. Language Learning & technology, 19 (2), 85–117 Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/issues/june2015/lin.pdf .

Lipsey, M., & Wilson, D. (2001). Practical meta-analysis (Applied social research methods) . Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Liu, Y., Cornish, A., & Clegg, J. (2007). ICT and special educational needs: Using meta-synthesis for bridging the multifaceted divide. In Y. Shi, G. D. van Albada, J. Dongarra, & P. M. A. Sloot (Eds.), Computational science–ICCS 2007. ICCS 2007. Lecture notes in computer science (Vol. 4490). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Ludvigsen, M. S., Hall, E. O. C., Meyer, G., Fegran, L., Aagaard, H., & Uhrenfeldt, L. (2016). Using Sandelowski and Barroso’s meta-synthesis method in advancing qualitative evidence. Qualitative Health Research, 26 (3), 320–329.

Lumley, T. (2002). Network meta-analysis for indirect treatment comparisons. Statistics in Medicine, 21 (16), 2313–2324. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1201 .

Lunn, D., Spiegelhalter, D., Thomas, A., & Best, N. (2009). The BUGS project: Evolution, critique and future directions. Statistics in Medicine, 28 (25), 3049–3067.

McKenney, S., & Reeves, T. C. (2012). Conducting educational design research . London: Routledge.

Mumtaz, S. (2000). Factors affecting teachers’ use of information and communications technology: A review of the literature. Journal of Information Technology for Teacher Education, 9 (3), 319–342.

Noblit, G. W., & Hare, R. D. (1988). Meta-ethnography: Synthesizing qualitative studies . London: Sage.

Paterson, B. L., Thorne, S. E., Canam, C., & Jillings, C. (2001). Meta-study of qualitative health research: A practical guide to meta-analysis and meta-synthesis . London: Sage.

Puhan, M. A., Schünemann, H. J., Murad, M. H., Li, T., Brignardello-Petersen, R., Singh, J. A., … Guyatt, G. H. (2014). A GRADE Working Group approach for rating the quality of treatment effect estimates from network meta-analysis. BMJ, 349, g5630.

Reeves, T., & Oh, E. (2017). The goals and methods of educational technology research over a quarter century (1989–2014). Educational Technology Research & Development, 65 (2), 325–339.

Salanti, G., Giovane, C. D., Chaimani, A., Caldwell, D. M., & Higgins, J. P. T. (2014). Evaluating the quality of evidence from a network meta-analysis. PLOS ONE, 9 (7), e99682.

Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2003). Toward a metasynthesis of qualitative findings on motherhood in HIV-positive women. Research in Nursing and Health, 26 (2), 153–170.

Sandelowski, M., Docherty, S., & Emden, C. (1997). Quality metasynthesis: Issues and techniques. Research in Nursing and Health, 20 , 365–371.

Taquero, J. M. (2011). A meta-ethnographic synthesis of support services in distance learning programs. Journal of Information Technology Education: Innovations in Practice, 10 , 157–179.

Thorne, S., Jensen, L., Kearney, M. H., Noblit, G., & Sandelowski, M. (2004). Qualitative metasynthesis: Reflection on methodological orientation and ideological agenda. Qualitative Health Research, 14 (10), 1342–1365.

Tondeur, J., van Braak, J., Sang, G., Voogt, J., Fisser, P., & Ottenbreit-Lewftwich, A. (2012). Preparing pre-service teachers to integrate technology in education: A synthesis of qualitative evidence. Computers & Education, 59 (1), 134–144.

Torraco, R. J. (2016). Writing integrative literature reviews: Using the past and present to explore the future. Human Resource Development Review, 15 (4), 404–428.

Walker, A., Belland, B., Kim, N., & Lefler, M. (2016). Searching for structure: A bayesian network meta-analysis of computer-based scaffolding research in STEM education. Paper presented at the American Educational Research Association, San Antonio, TX.

Walsh, D., & Downe, S. (2005). Meta-synthesis method for qualitative research: A literature review. Methodological Issues in Nursing Education, 50 (2), 204–211.

Young, J. (2017). Technology-enhanced mathematics instruction: A second-order meta-analysis of 30 years of research. Educational Research Review, 22 , 19–33.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Brigham Young University, 150-G MCKB, Provo, UT, 84602, USA

Heather Leary

Utah State University, 2830 Old Main Hill, Logan, UT, 84322, USA

Andrew Walker

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Heather Leary .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human Studies

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Leary, H., Walker, A. Meta-Analysis and Meta-Synthesis Methodologies: Rigorously Piecing Together Research. TechTrends 62 , 525–534 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-018-0312-7

Download citation

Published : 18 June 2018

Issue Date : September 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-018-0312-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Meta-analysis

- Meta-synthesis

- Synthesis methods

- Education research

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government