- Research Report: Definition, Types + [Writing Guide]

One of the reasons for carrying out research is to add to the existing body of knowledge. Therefore, when conducting research, you need to document your processes and findings in a research report.

With a research report, it is easy to outline the findings of your systematic investigation and any gaps needing further inquiry. Knowing how to create a detailed research report will prove useful when you need to conduct research.

What is a Research Report?

A research report is a well-crafted document that outlines the processes, data, and findings of a systematic investigation. It is an important document that serves as a first-hand account of the research process, and it is typically considered an objective and accurate source of information.

In many ways, a research report can be considered as a summary of the research process that clearly highlights findings, recommendations, and other important details. Reading a well-written research report should provide you with all the information you need about the core areas of the research process.

Features of a Research Report

So how do you recognize a research report when you see one? Here are some of the basic features that define a research report.

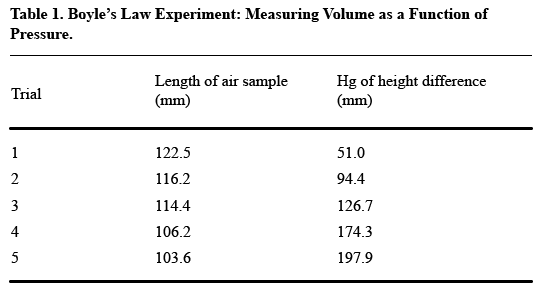

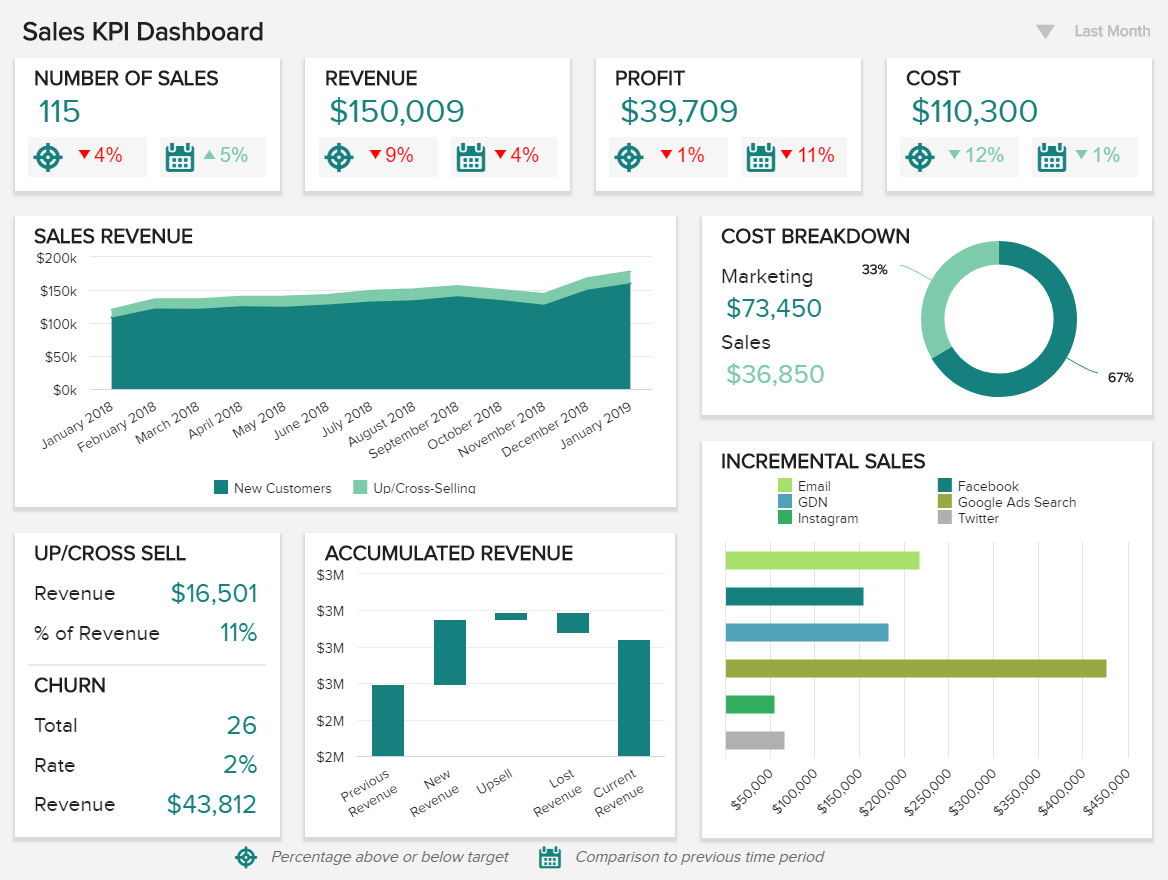

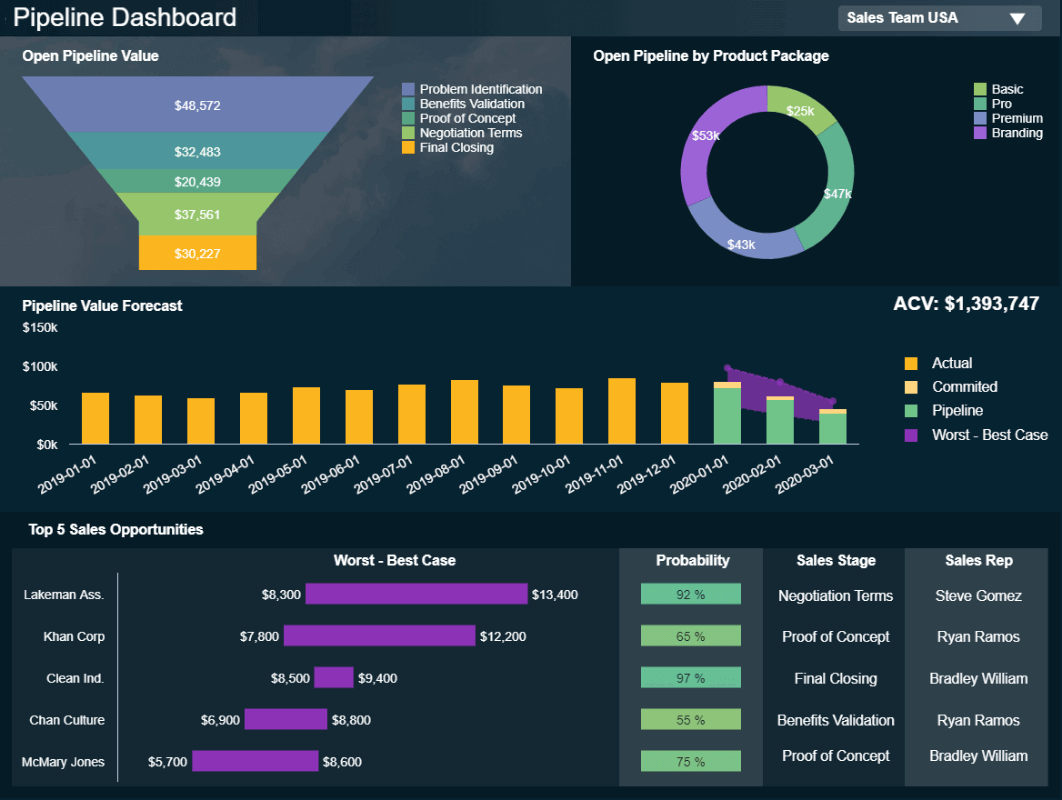

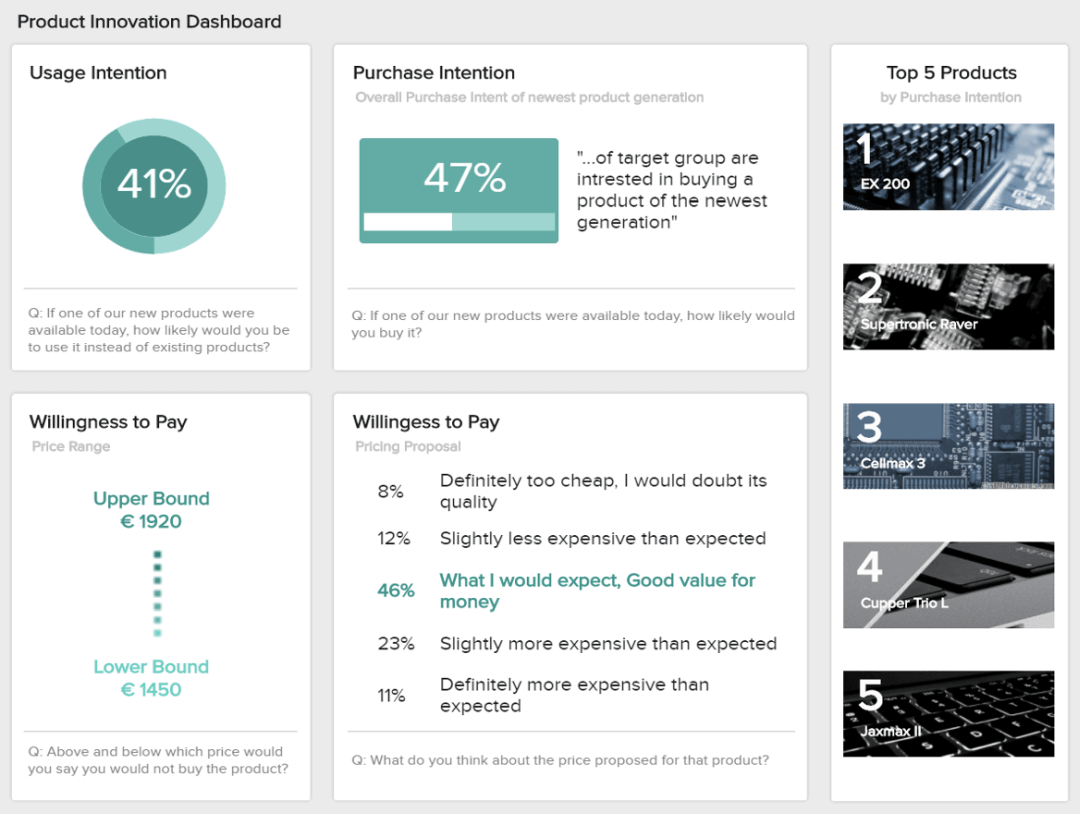

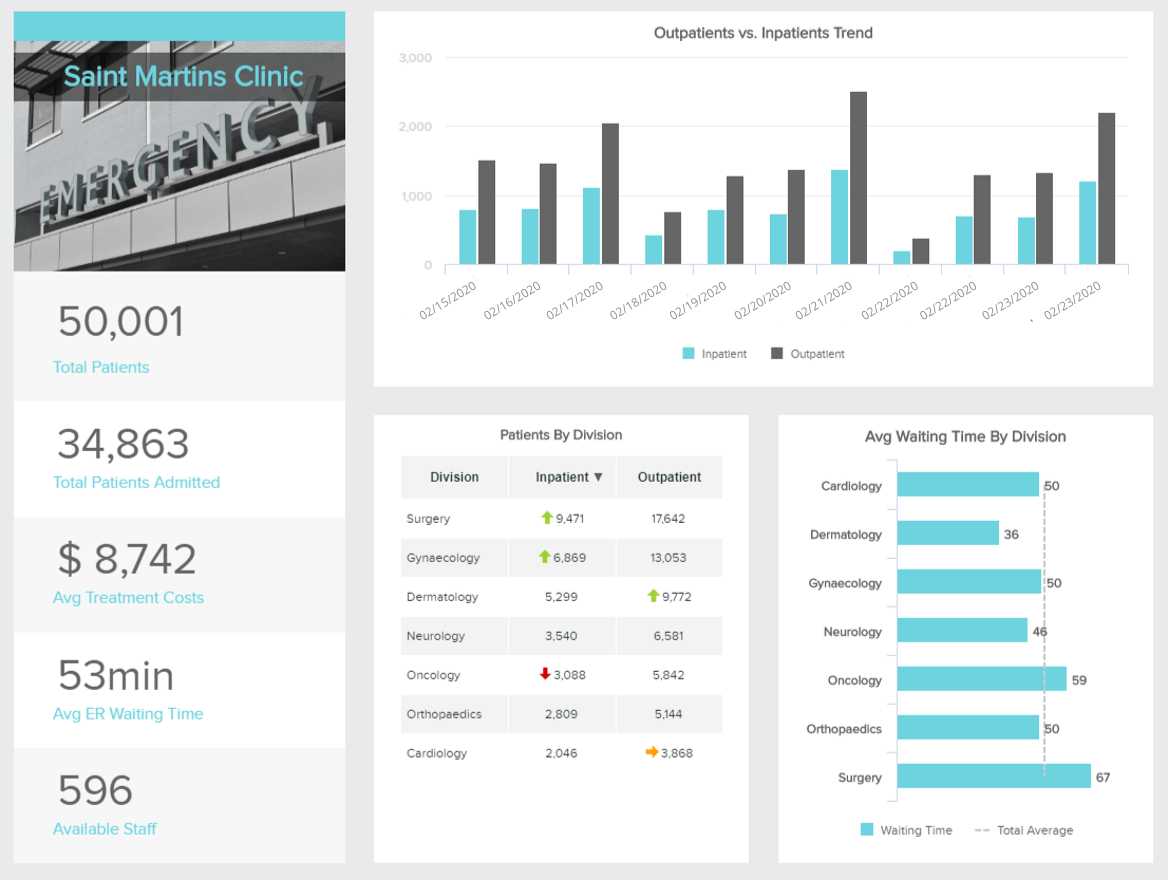

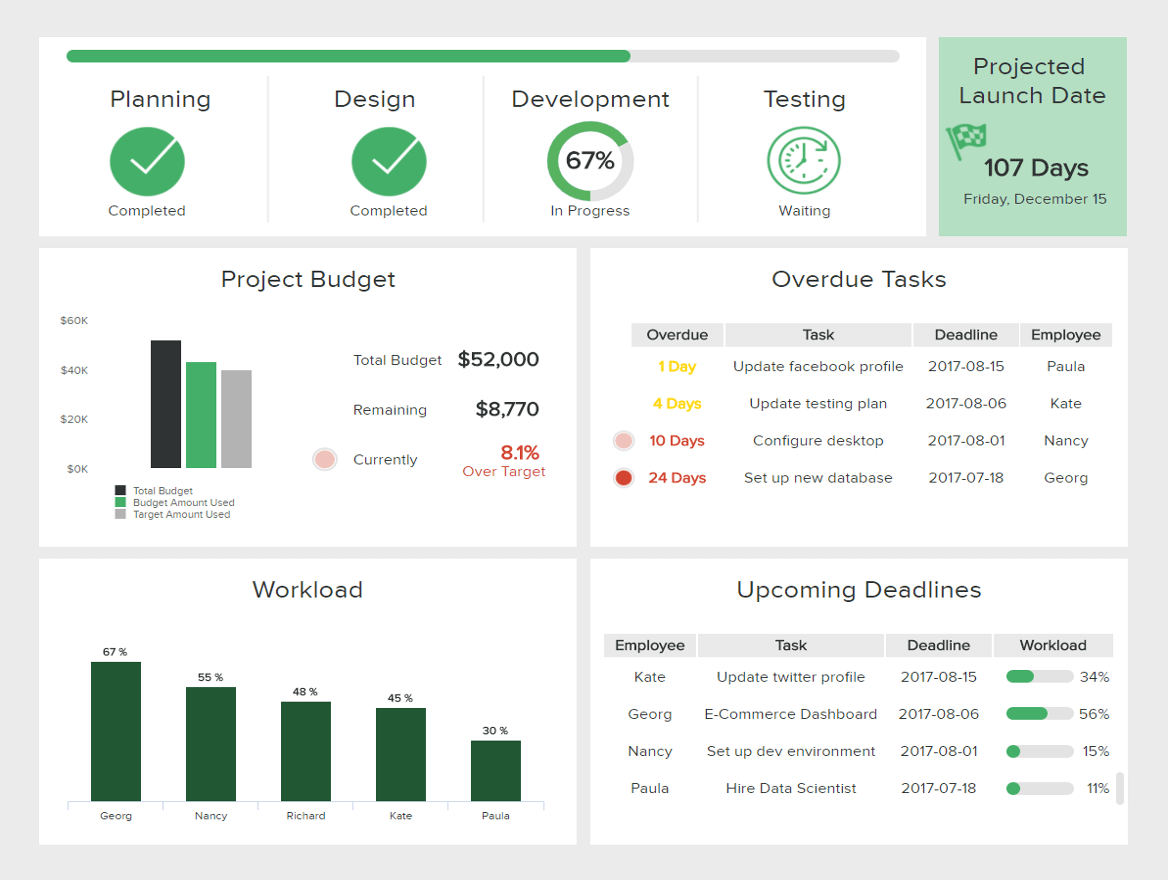

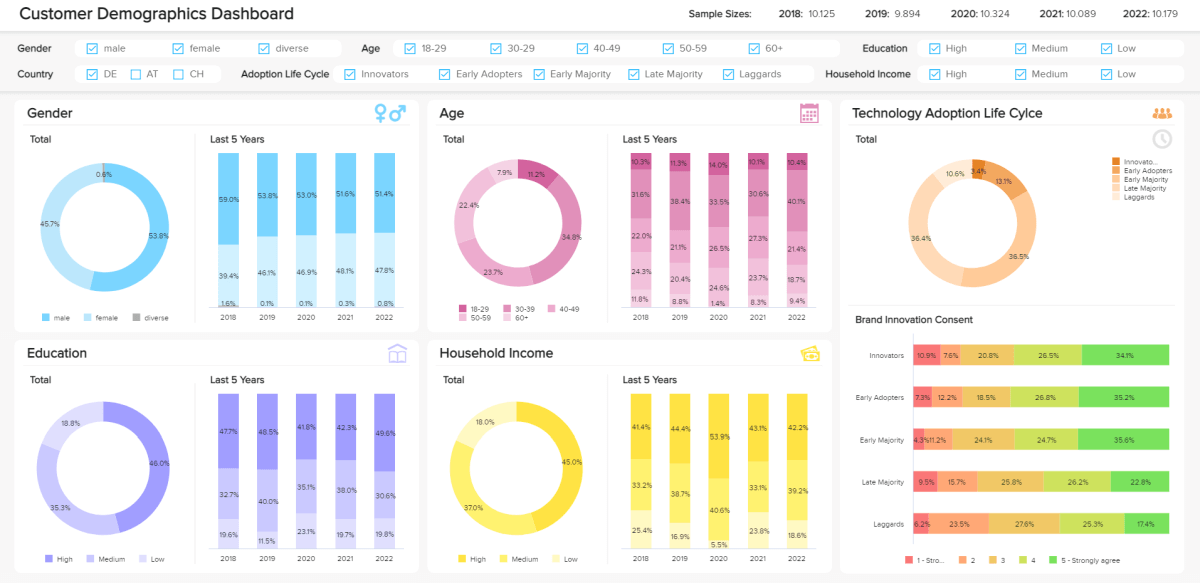

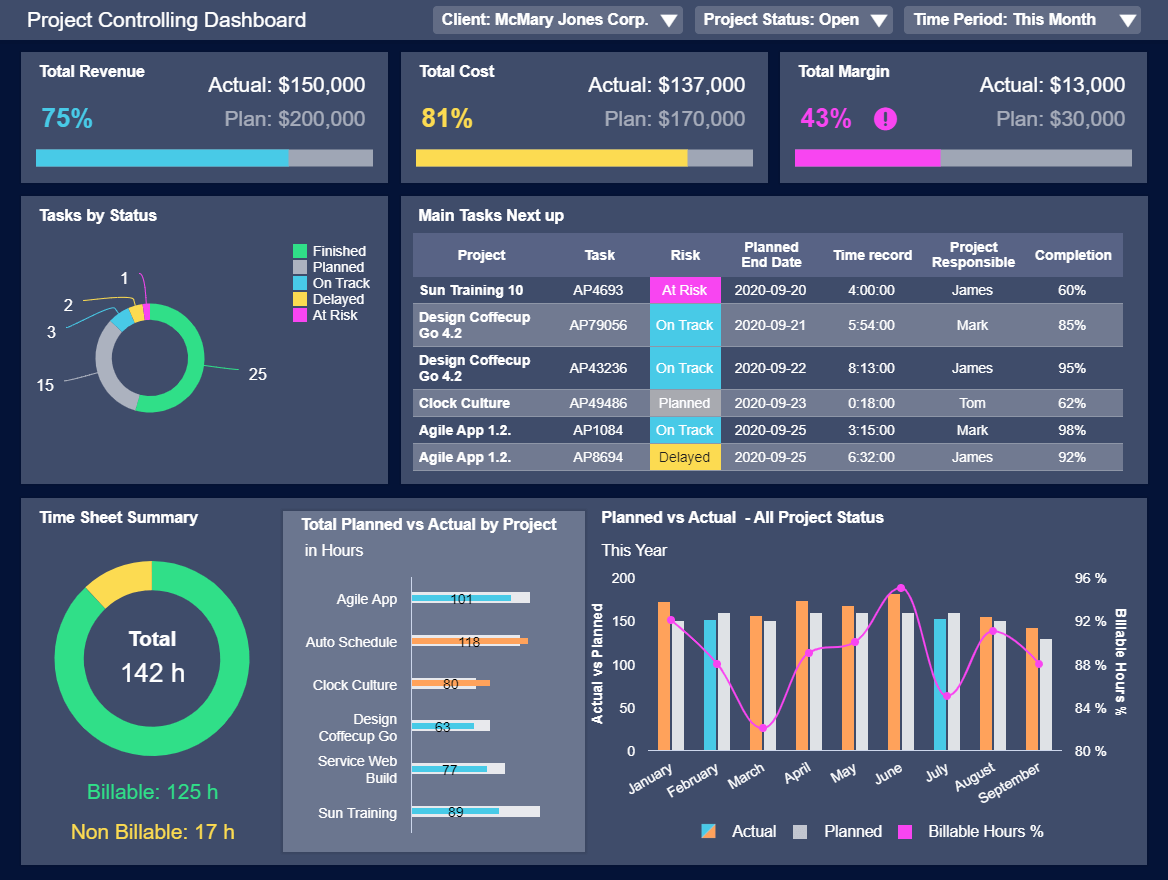

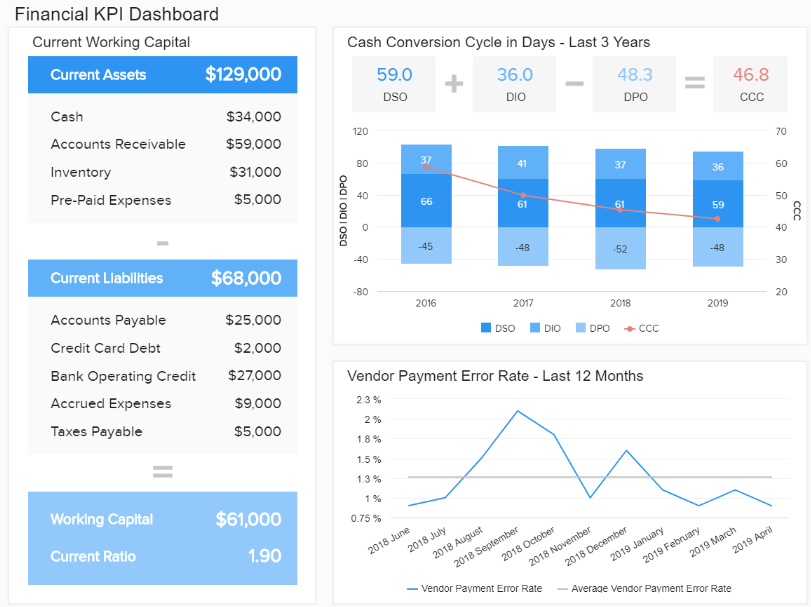

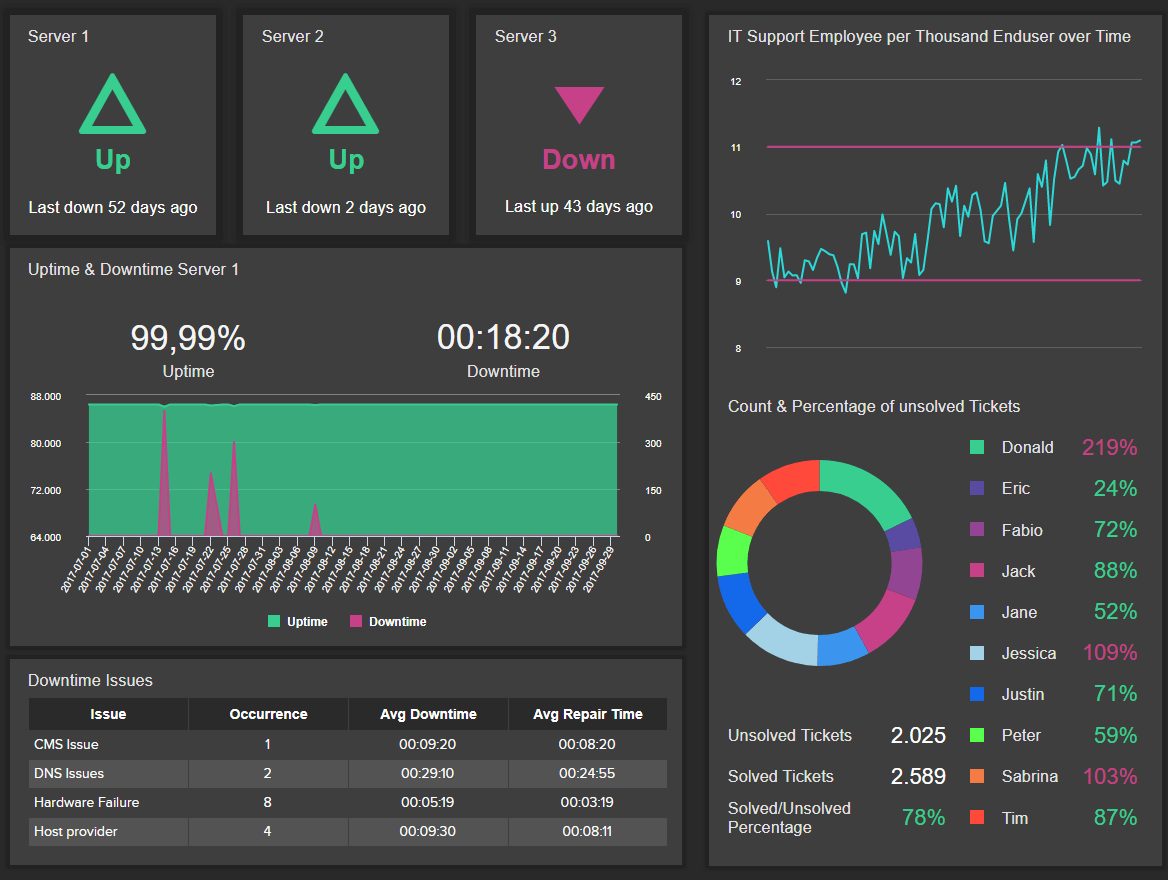

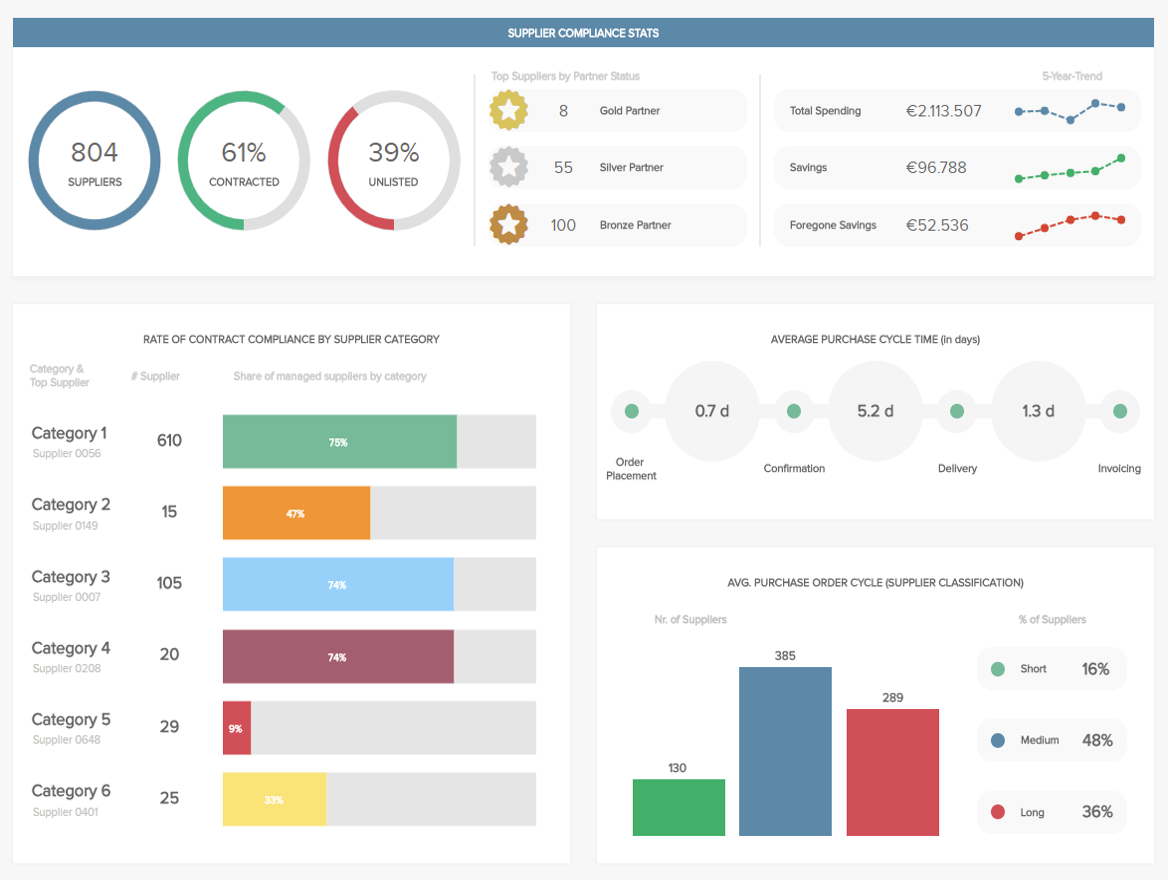

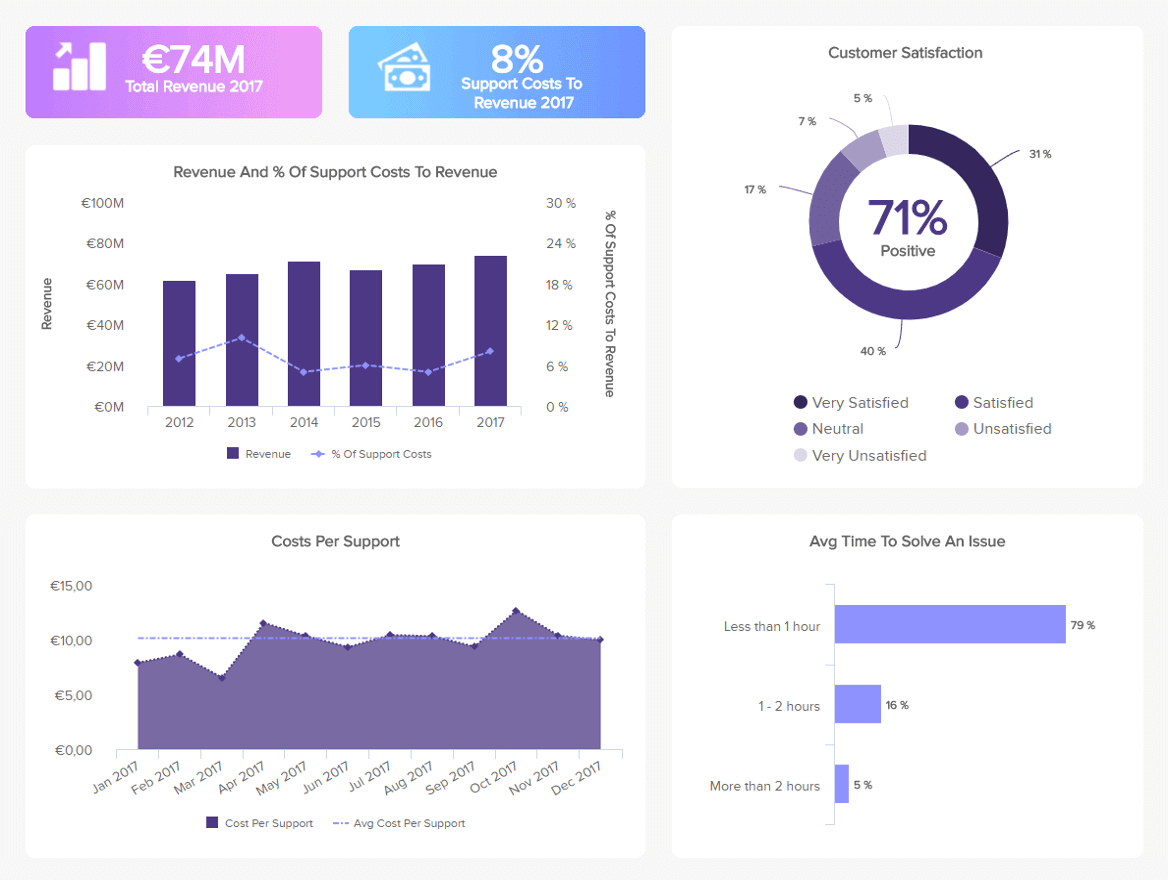

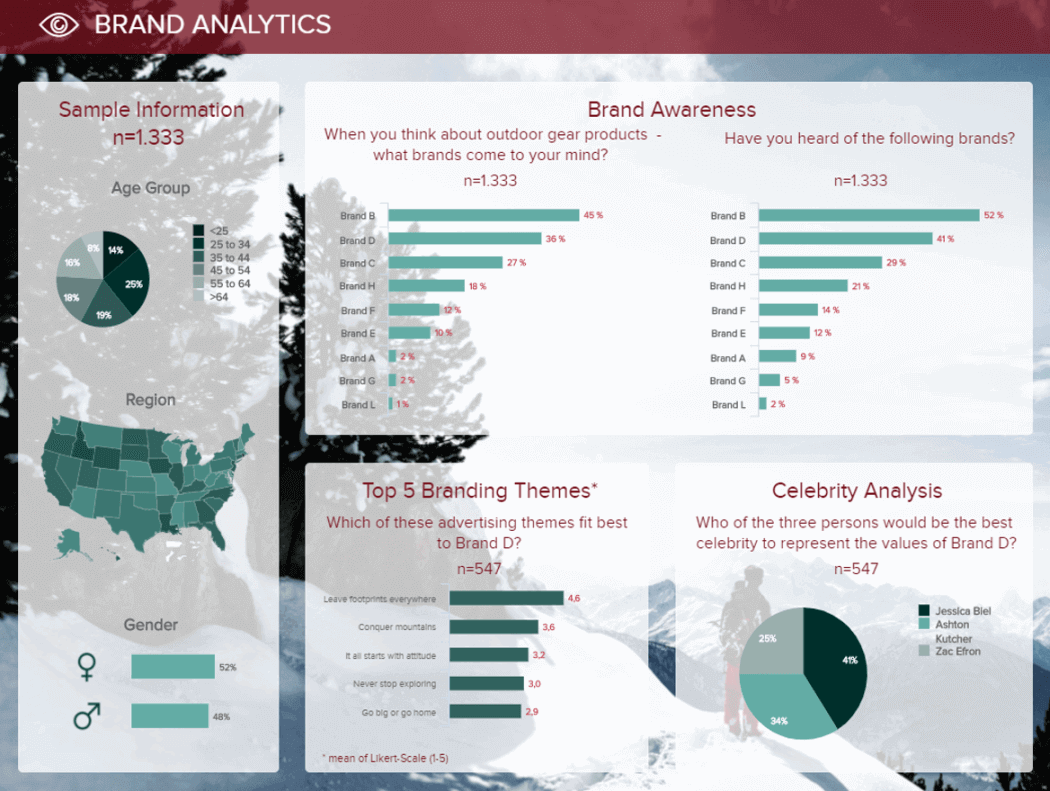

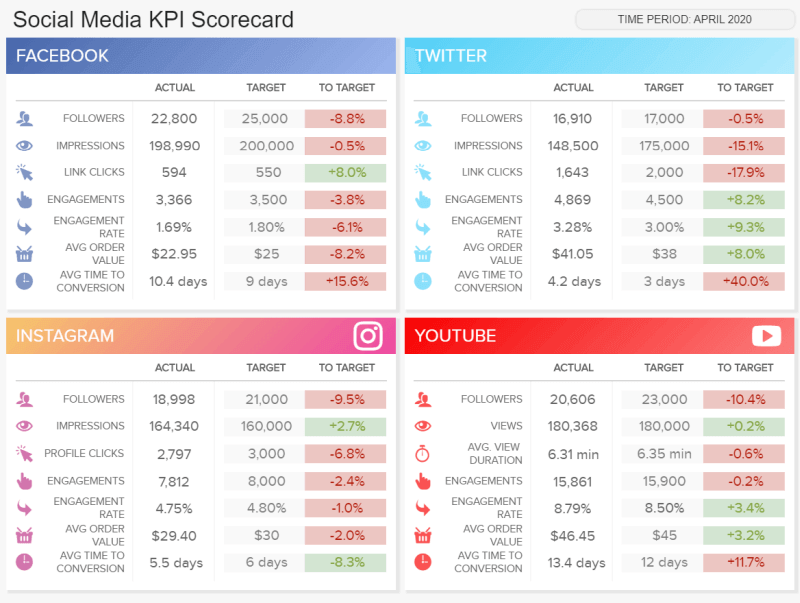

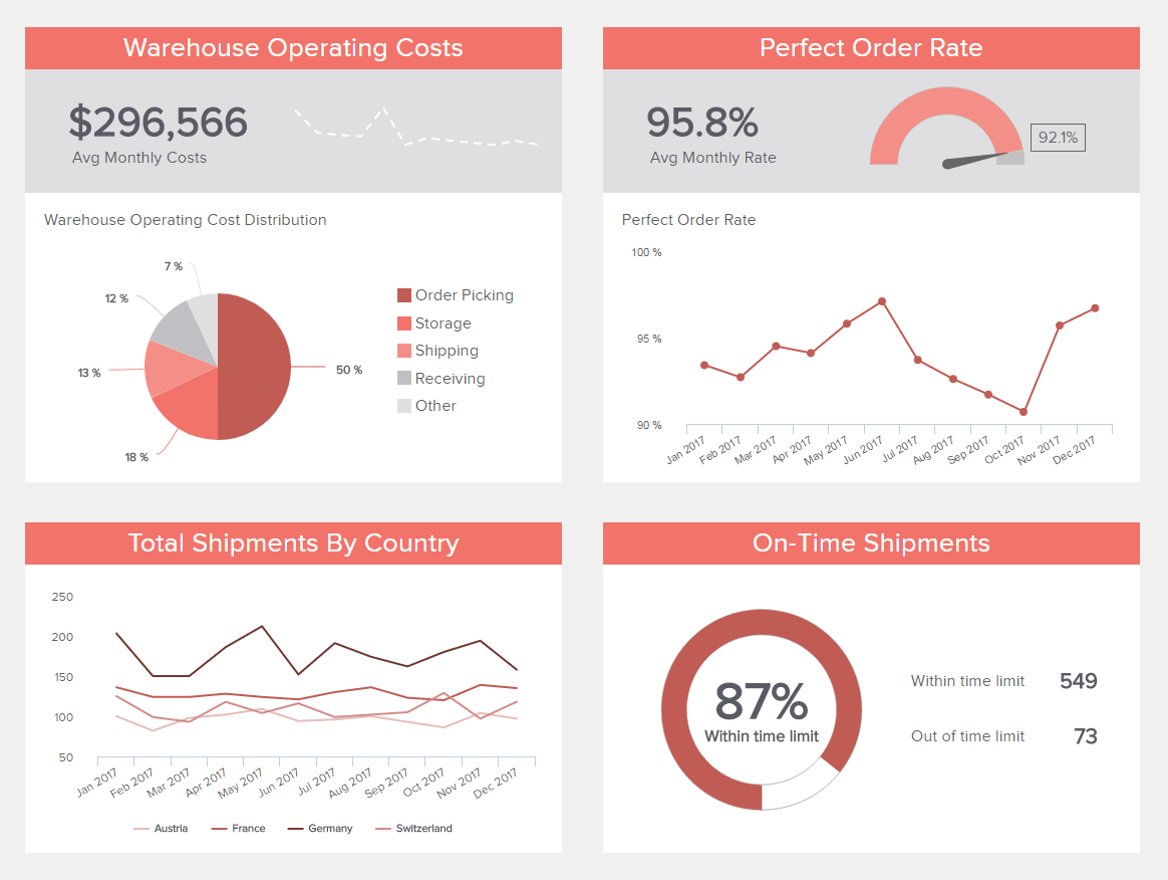

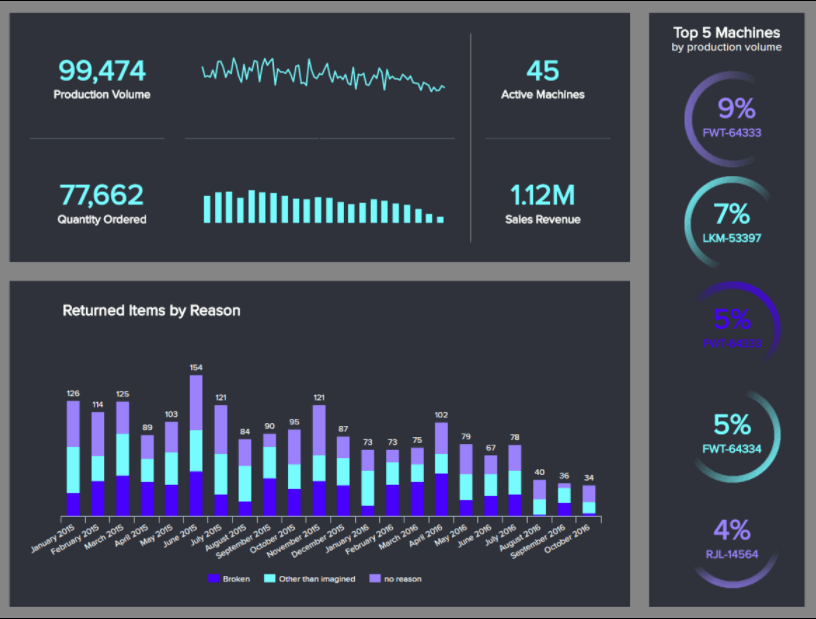

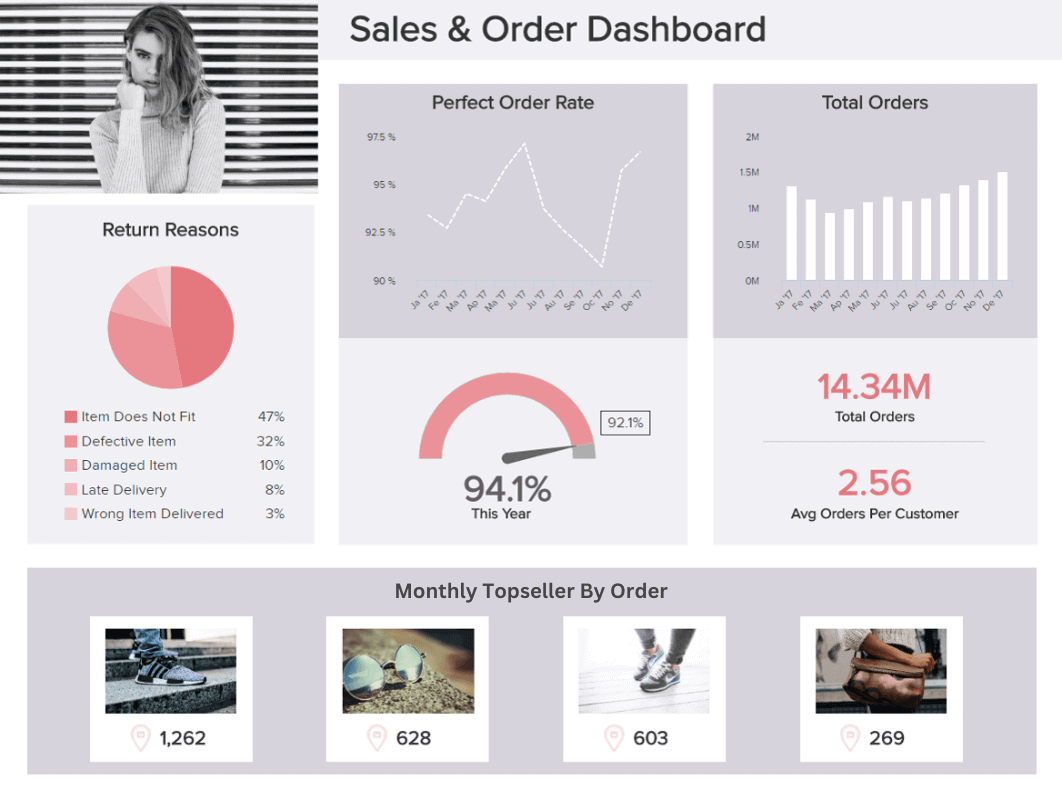

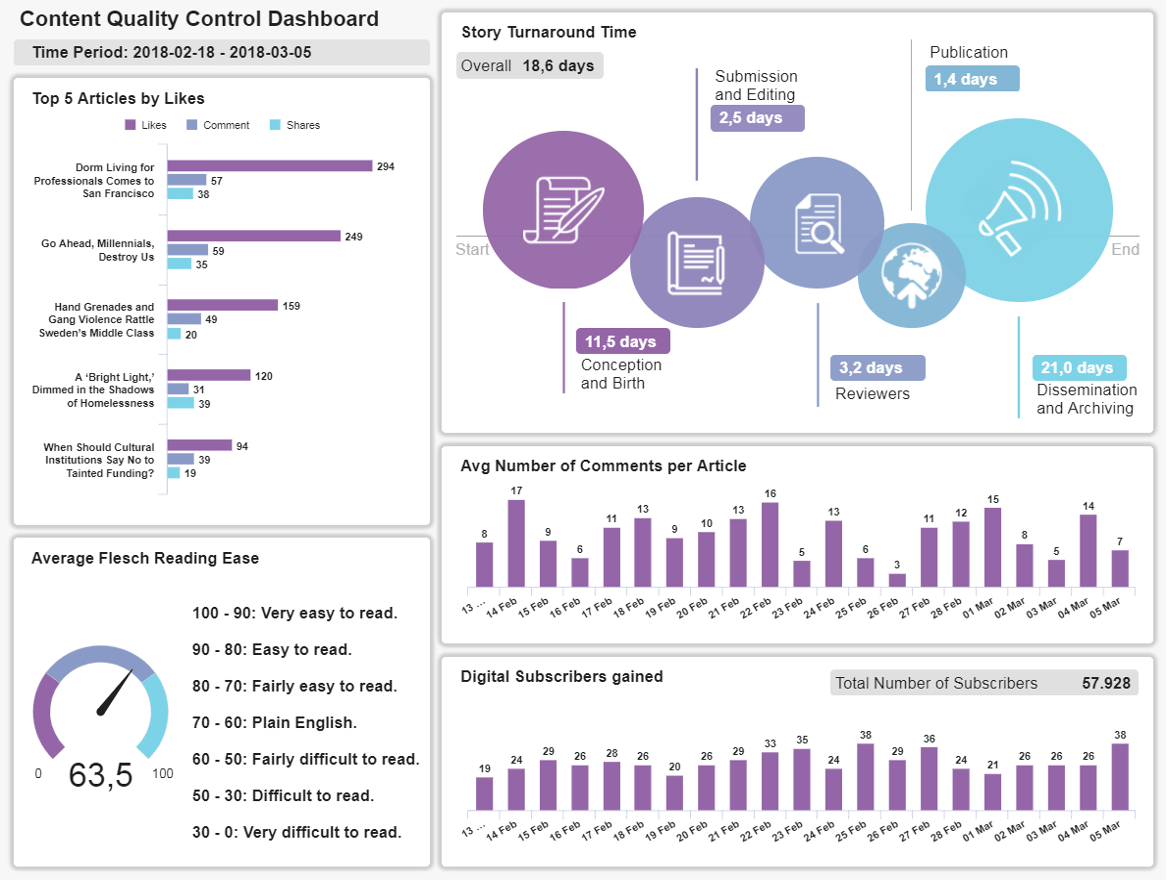

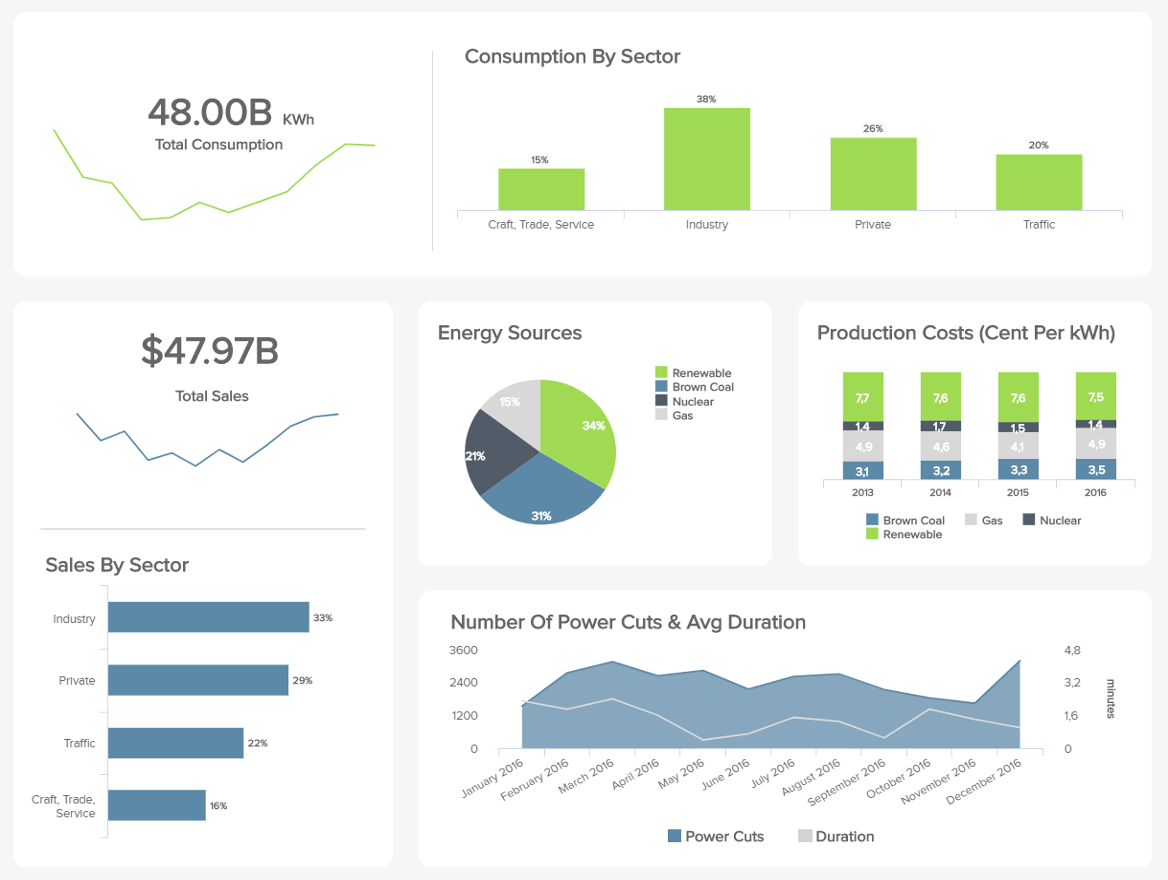

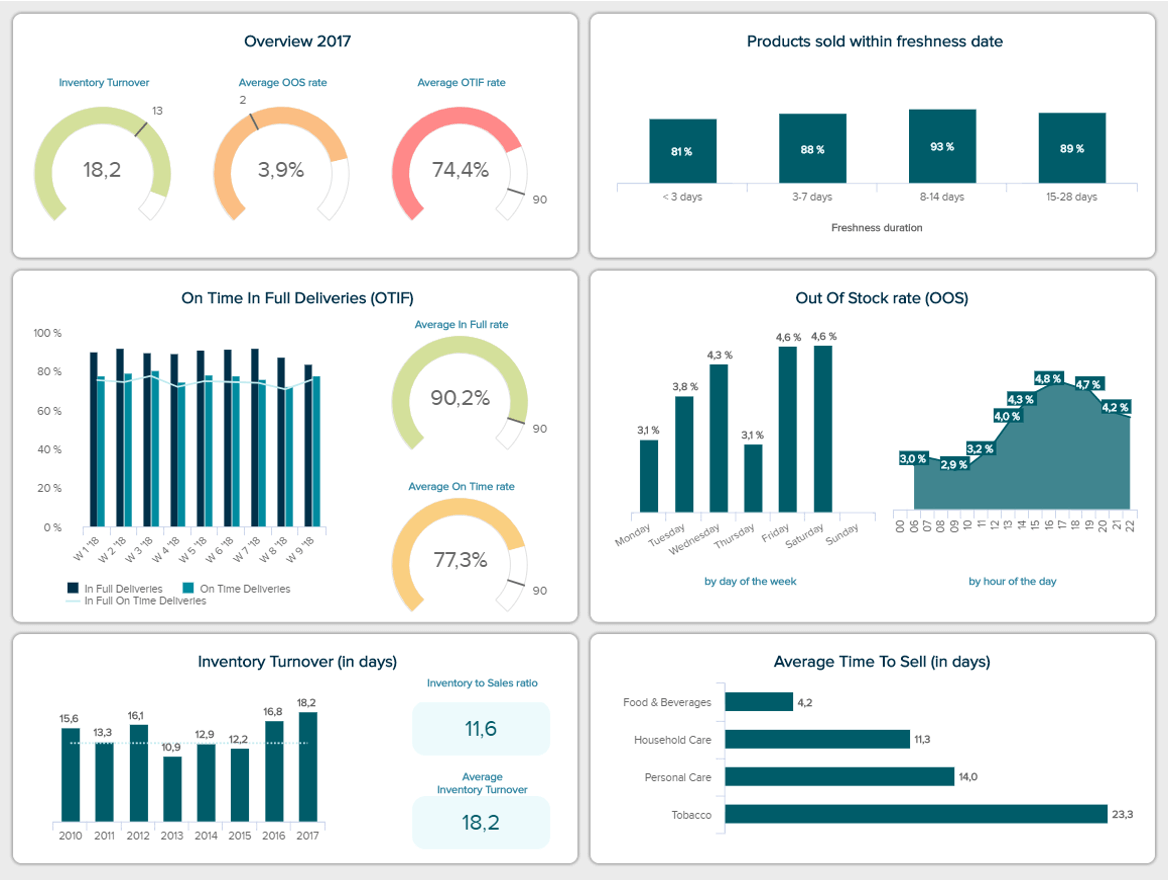

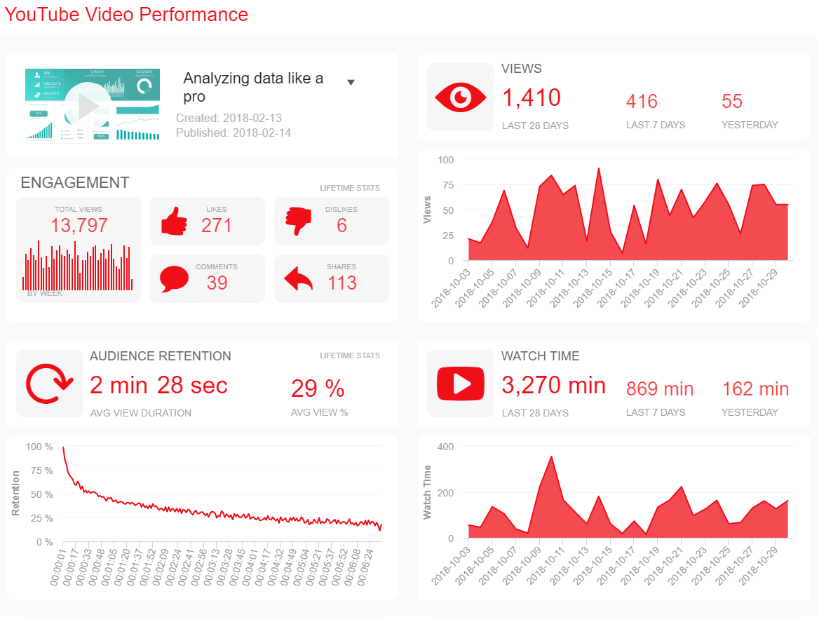

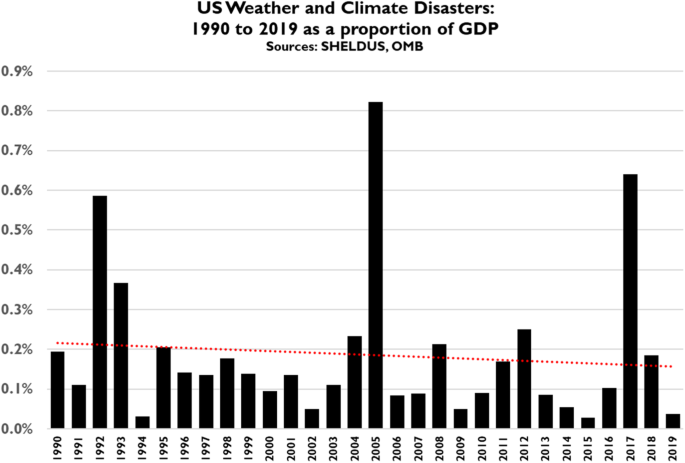

- It is a detailed presentation of research processes and findings, and it usually includes tables and graphs.

- It is written in a formal language.

- A research report is usually written in the third person.

- It is informative and based on first-hand verifiable information.

- It is formally structured with headings, sections, and bullet points.

- It always includes recommendations for future actions.

Types of Research Report

The research report is classified based on two things; nature of research and target audience.

Nature of Research

- Qualitative Research Report

This is the type of report written for qualitative research . It outlines the methods, processes, and findings of a qualitative method of systematic investigation. In educational research, a qualitative research report provides an opportunity for one to apply his or her knowledge and develop skills in planning and executing qualitative research projects.

A qualitative research report is usually descriptive in nature. Hence, in addition to presenting details of the research process, you must also create a descriptive narrative of the information.

- Quantitative Research Report

A quantitative research report is a type of research report that is written for quantitative research. Quantitative research is a type of systematic investigation that pays attention to numerical or statistical values in a bid to find answers to research questions.

In this type of research report, the researcher presents quantitative data to support the research process and findings. Unlike a qualitative research report that is mainly descriptive, a quantitative research report works with numbers; that is, it is numerical in nature.

Target Audience

Also, a research report can be said to be technical or popular based on the target audience. If you’re dealing with a general audience, you would need to present a popular research report, and if you’re dealing with a specialized audience, you would submit a technical report.

- Technical Research Report

A technical research report is a detailed document that you present after carrying out industry-based research. This report is highly specialized because it provides information for a technical audience; that is, individuals with above-average knowledge in the field of study.

In a technical research report, the researcher is expected to provide specific information about the research process, including statistical analyses and sampling methods. Also, the use of language is highly specialized and filled with jargon.

Examples of technical research reports include legal and medical research reports.

- Popular Research Report

A popular research report is one for a general audience; that is, for individuals who do not necessarily have any knowledge in the field of study. A popular research report aims to make information accessible to everyone.

It is written in very simple language, which makes it easy to understand the findings and recommendations. Examples of popular research reports are the information contained in newspapers and magazines.

Importance of a Research Report

- Knowledge Transfer: As already stated above, one of the reasons for carrying out research is to contribute to the existing body of knowledge, and this is made possible with a research report. A research report serves as a means to effectively communicate the findings of a systematic investigation to all and sundry.

- Identification of Knowledge Gaps: With a research report, you’d be able to identify knowledge gaps for further inquiry. A research report shows what has been done while hinting at other areas needing systematic investigation.

- In market research, a research report would help you understand the market needs and peculiarities at a glance.

- A research report allows you to present information in a precise and concise manner.

- It is time-efficient and practical because, in a research report, you do not have to spend time detailing the findings of your research work in person. You can easily send out the report via email and have stakeholders look at it.

Guide to Writing a Research Report

A lot of detail goes into writing a research report, and getting familiar with the different requirements would help you create the ideal research report. A research report is usually broken down into multiple sections, which allows for a concise presentation of information.

Structure and Example of a Research Report

This is the title of your systematic investigation. Your title should be concise and point to the aims, objectives, and findings of a research report.

- Table of Contents

This is like a compass that makes it easier for readers to navigate the research report.

An abstract is an overview that highlights all important aspects of the research including the research method, data collection process, and research findings. Think of an abstract as a summary of your research report that presents pertinent information in a concise manner.

An abstract is always brief; typically 100-150 words and goes straight to the point. The focus of your research abstract should be the 5Ws and 1H format – What, Where, Why, When, Who and How.

- Introduction

Here, the researcher highlights the aims and objectives of the systematic investigation as well as the problem which the systematic investigation sets out to solve. When writing the report introduction, it is also essential to indicate whether the purposes of the research were achieved or would require more work.

In the introduction section, the researcher specifies the research problem and also outlines the significance of the systematic investigation. Also, the researcher is expected to outline any jargons and terminologies that are contained in the research.

- Literature Review

A literature review is a written survey of existing knowledge in the field of study. In other words, it is the section where you provide an overview and analysis of different research works that are relevant to your systematic investigation.

It highlights existing research knowledge and areas needing further investigation, which your research has sought to fill. At this stage, you can also hint at your research hypothesis and its possible implications for the existing body of knowledge in your field of study.

- An Account of Investigation

This is a detailed account of the research process, including the methodology, sample, and research subjects. Here, you are expected to provide in-depth information on the research process including the data collection and analysis procedures.

In a quantitative research report, you’d need to provide information surveys, questionnaires and other quantitative data collection methods used in your research. In a qualitative research report, you are expected to describe the qualitative data collection methods used in your research including interviews and focus groups.

In this section, you are expected to present the results of the systematic investigation.

This section further explains the findings of the research, earlier outlined. Here, you are expected to present a justification for each outcome and show whether the results are in line with your hypotheses or if other research studies have come up with similar results.

- Conclusions

This is a summary of all the information in the report. It also outlines the significance of the entire study.

- References and Appendices

This section contains a list of all the primary and secondary research sources.

Tips for Writing a Research Report

- Define the Context for the Report

As is obtainable when writing an essay, defining the context for your research report would help you create a detailed yet concise document. This is why you need to create an outline before writing so that you do not miss out on anything.

- Define your Audience

Writing with your audience in mind is essential as it determines the tone of the report. If you’re writing for a general audience, you would want to present the information in a simple and relatable manner. For a specialized audience, you would need to make use of technical and field-specific terms.

- Include Significant Findings

The idea of a research report is to present some sort of abridged version of your systematic investigation. In your report, you should exclude irrelevant information while highlighting only important data and findings.

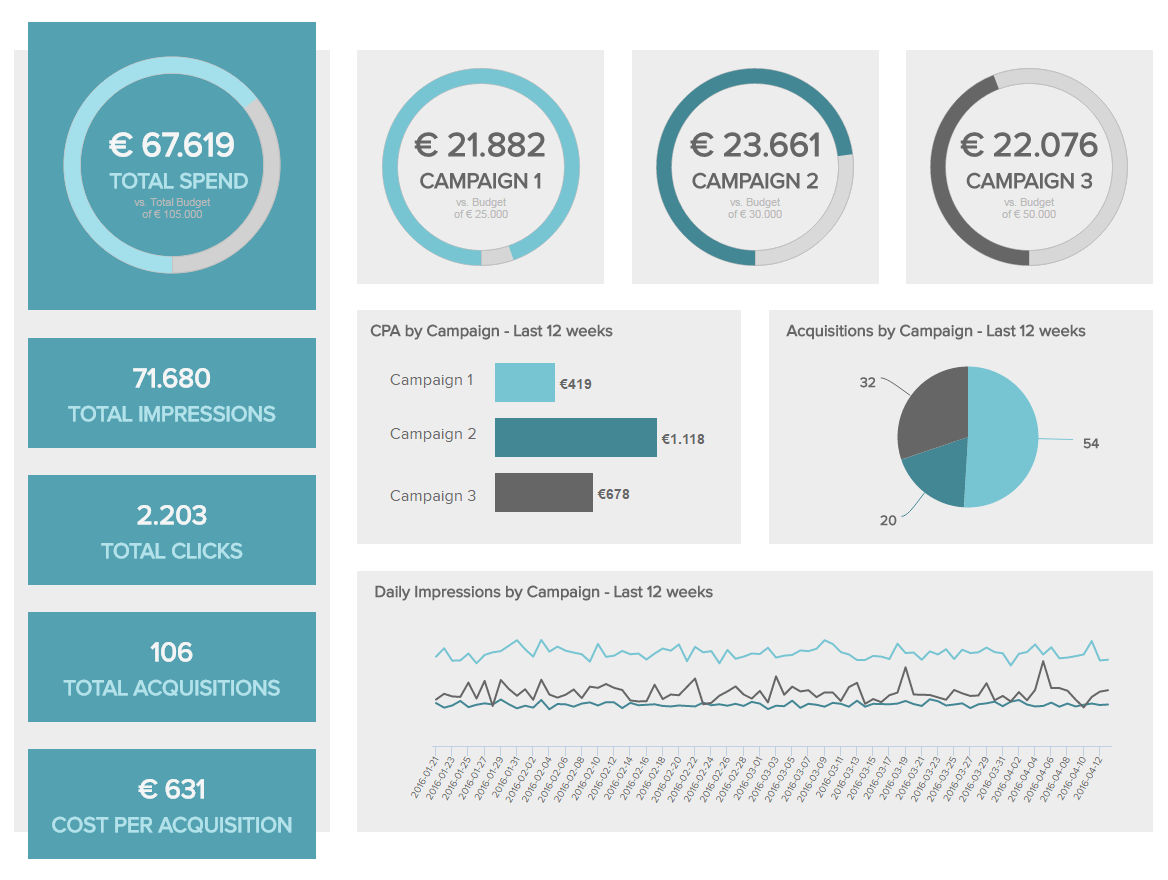

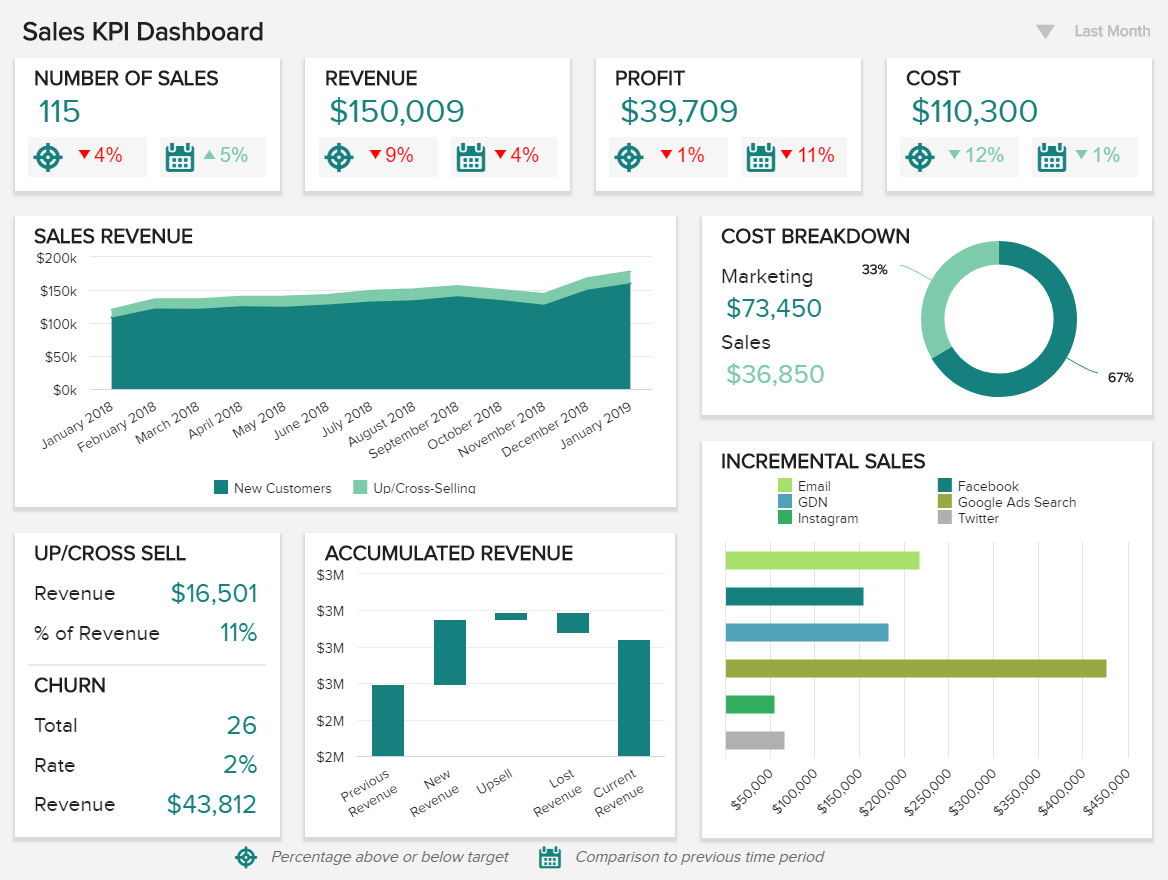

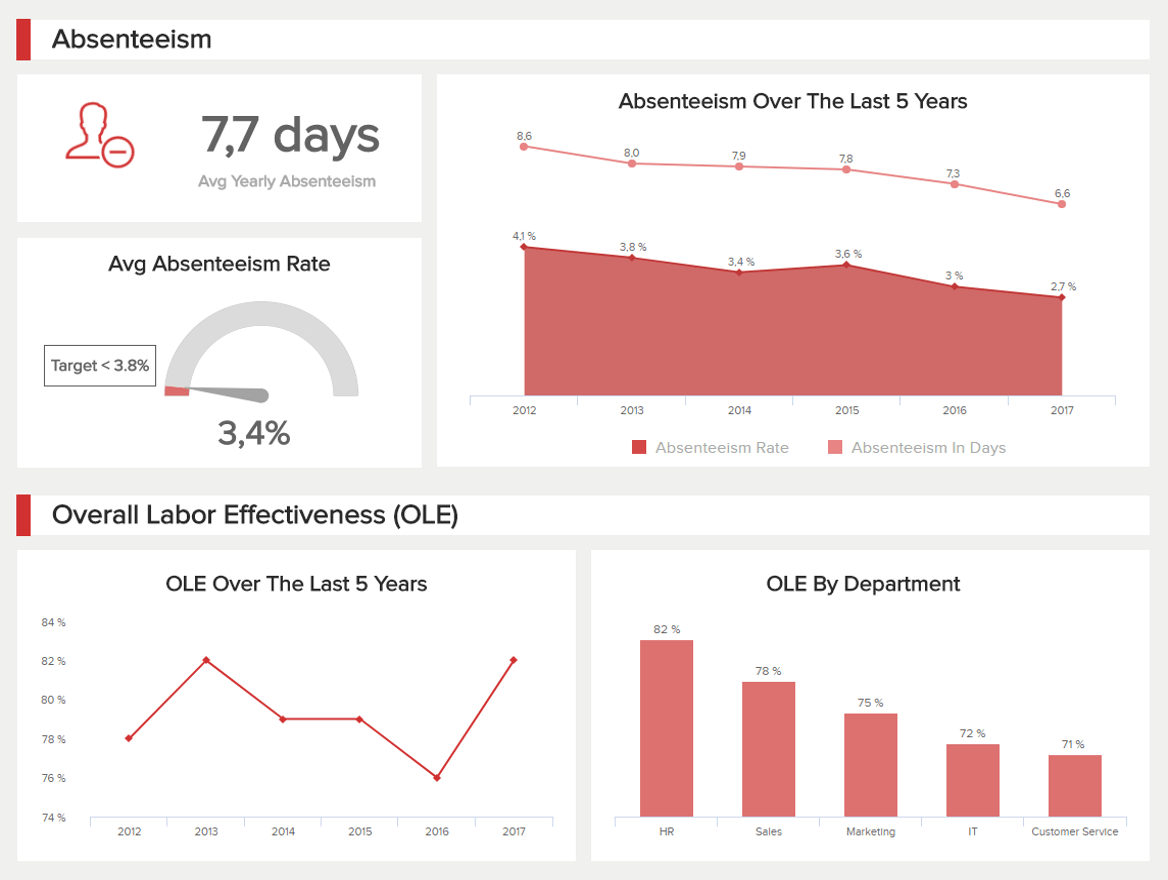

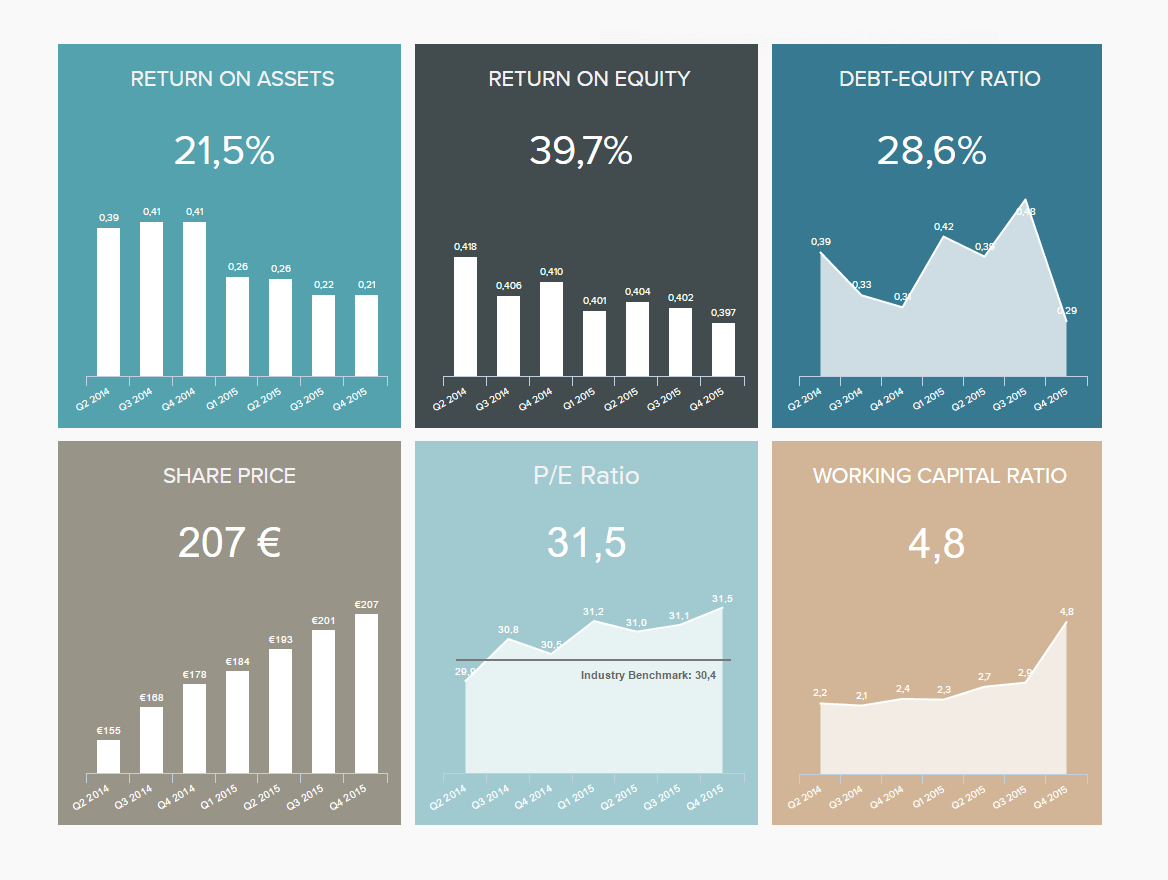

- Include Illustrations

Your research report should include illustrations and other visual representations of your data. Graphs, pie charts, and relevant images lend additional credibility to your systematic investigation.

- Choose the Right Title

A good research report title is brief, precise, and contains keywords from your research. It should provide a clear idea of your systematic investigation so that readers can grasp the entire focus of your research from the title.

- Proofread the Report

Before publishing the document, ensure that you give it a second look to authenticate the information. If you can, get someone else to go through the report, too, and you can also run it through proofreading and editing software.

How to Gather Research Data for Your Report

- Understand the Problem

Every research aims at solving a specific problem or set of problems, and this should be at the back of your mind when writing your research report. Understanding the problem would help you to filter the information you have and include only important data in your report.

- Know what your report seeks to achieve

This is somewhat similar to the point above because, in some way, the aim of your research report is intertwined with the objectives of your systematic investigation. Identifying the primary purpose of writing a research report would help you to identify and present the required information accordingly.

- Identify your audience

Knowing your target audience plays a crucial role in data collection for a research report. If your research report is specifically for an organization, you would want to present industry-specific information or show how the research findings are relevant to the work that the company does.

- Create Surveys/Questionnaires

A survey is a research method that is used to gather data from a specific group of people through a set of questions. It can be either quantitative or qualitative.

A survey is usually made up of structured questions, and it can be administered online or offline. However, an online survey is a more effective method of research data collection because it helps you save time and gather data with ease.

You can seamlessly create an online questionnaire for your research on Formplus . With the multiple sharing options available in the builder, you would be able to administer your survey to respondents in little or no time.

Formplus also has a report summary too l that you can use to create custom visual reports for your research.

Step-by-step guide on how to create an online questionnaire using Formplus

- Sign into Formplus

In the Formplus builder, you can easily create different online questionnaires for your research by dragging and dropping preferred fields into your form. To access the Formplus builder, you will need to create an account on Formplus.

Once you do this, sign in to your account and click on Create new form to begin.

- Edit Form Title : Click on the field provided to input your form title, for example, “Research Questionnaire.”

- Edit Form : Click on the edit icon to edit the form.

- Add Fields : Drag and drop preferred form fields into your form in the Formplus builder inputs column. There are several field input options for questionnaires in the Formplus builder.

- Edit fields

- Click on “Save”

- Form Customization: With the form customization options in the form builder, you can easily change the outlook of your form and make it more unique and personalized. Formplus allows you to change your form theme, add background images, and even change the font according to your needs.

- Multiple Sharing Options: Formplus offers various form-sharing options, which enables you to share your questionnaire with respondents easily. You can use the direct social media sharing buttons to share your form link to your organization’s social media pages. You can also send out your survey form as email invitations to your research subjects too. If you wish, you can share your form’s QR code or embed it on your organization’s website for easy access.

Conclusion

Always remember that a research report is just as important as the actual systematic investigation because it plays a vital role in communicating research findings to everyone else. This is why you must take care to create a concise document summarizing the process of conducting any research.

In this article, we’ve outlined essential tips to help you create a research report. When writing your report, you should always have the audience at the back of your mind, as this would set the tone for the document.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- ethnographic research survey

- research report

- research report survey

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

How to Write a Problem Statement for your Research

Learn how to write problem statements before commencing any research effort. Learn about its structure and explore examples

Ethnographic Research: Types, Methods + [Question Examples]

Simple guide on ethnographic research, it types, methods, examples and advantages. Also highlights how to conduct an ethnographic...

21 Chrome Extensions for Academic Researchers in 2022

In this article, we will discuss a number of chrome extensions you can use to make your research process even seamless

Assessment Tools: Types, Examples & Importance

In this article, you’ll learn about different assessment tools to help you evaluate performance in various contexts

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 11: Presenting Your Research

Writing a Research Report in American Psychological Association (APA) Style

Learning Objectives

- Identify the major sections of an APA-style research report and the basic contents of each section.

- Plan and write an effective APA-style research report.

In this section, we look at how to write an APA-style empirical research report , an article that presents the results of one or more new studies. Recall that the standard sections of an empirical research report provide a kind of outline. Here we consider each of these sections in detail, including what information it contains, how that information is formatted and organized, and tips for writing each section. At the end of this section is a sample APA-style research report that illustrates many of these principles.

Sections of a Research Report

Title page and abstract.

An APA-style research report begins with a title page . The title is centred in the upper half of the page, with each important word capitalized. The title should clearly and concisely (in about 12 words or fewer) communicate the primary variables and research questions. This sometimes requires a main title followed by a subtitle that elaborates on the main title, in which case the main title and subtitle are separated by a colon. Here are some titles from recent issues of professional journals published by the American Psychological Association.

- Sex Differences in Coping Styles and Implications for Depressed Mood

- Effects of Aging and Divided Attention on Memory for Items and Their Contexts

- Computer-Assisted Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Child Anxiety: Results of a Randomized Clinical Trial

- Virtual Driving and Risk Taking: Do Racing Games Increase Risk-Taking Cognitions, Affect, and Behaviour?

Below the title are the authors’ names and, on the next line, their institutional affiliation—the university or other institution where the authors worked when they conducted the research. As we have already seen, the authors are listed in an order that reflects their contribution to the research. When multiple authors have made equal contributions to the research, they often list their names alphabetically or in a randomly determined order.

In some areas of psychology, the titles of many empirical research reports are informal in a way that is perhaps best described as “cute.” They usually take the form of a play on words or a well-known expression that relates to the topic under study. Here are some examples from recent issues of the Journal Psychological Science .

- “Smells Like Clean Spirit: Nonconscious Effects of Scent on Cognition and Behavior”

- “Time Crawls: The Temporal Resolution of Infants’ Visual Attention”

- “Scent of a Woman: Men’s Testosterone Responses to Olfactory Ovulation Cues”

- “Apocalypse Soon?: Dire Messages Reduce Belief in Global Warming by Contradicting Just-World Beliefs”

- “Serial vs. Parallel Processing: Sometimes They Look Like Tweedledum and Tweedledee but They Can (and Should) Be Distinguished”

- “How Do I Love Thee? Let Me Count the Words: The Social Effects of Expressive Writing”

Individual researchers differ quite a bit in their preference for such titles. Some use them regularly, while others never use them. What might be some of the pros and cons of using cute article titles?

For articles that are being submitted for publication, the title page also includes an author note that lists the authors’ full institutional affiliations, any acknowledgments the authors wish to make to agencies that funded the research or to colleagues who commented on it, and contact information for the authors. For student papers that are not being submitted for publication—including theses—author notes are generally not necessary.

The abstract is a summary of the study. It is the second page of the manuscript and is headed with the word Abstract . The first line is not indented. The abstract presents the research question, a summary of the method, the basic results, and the most important conclusions. Because the abstract is usually limited to about 200 words, it can be a challenge to write a good one.

Introduction

The introduction begins on the third page of the manuscript. The heading at the top of this page is the full title of the manuscript, with each important word capitalized as on the title page. The introduction includes three distinct subsections, although these are typically not identified by separate headings. The opening introduces the research question and explains why it is interesting, the literature review discusses relevant previous research, and the closing restates the research question and comments on the method used to answer it.

The Opening

The opening , which is usually a paragraph or two in length, introduces the research question and explains why it is interesting. To capture the reader’s attention, researcher Daryl Bem recommends starting with general observations about the topic under study, expressed in ordinary language (not technical jargon)—observations that are about people and their behaviour (not about researchers or their research; Bem, 2003 [1] ). Concrete examples are often very useful here. According to Bem, this would be a poor way to begin a research report:

Festinger’s theory of cognitive dissonance received a great deal of attention during the latter part of the 20th century (p. 191)

The following would be much better:

The individual who holds two beliefs that are inconsistent with one another may feel uncomfortable. For example, the person who knows that he or she enjoys smoking but believes it to be unhealthy may experience discomfort arising from the inconsistency or disharmony between these two thoughts or cognitions. This feeling of discomfort was called cognitive dissonance by social psychologist Leon Festinger (1957), who suggested that individuals will be motivated to remove this dissonance in whatever way they can (p. 191).

After capturing the reader’s attention, the opening should go on to introduce the research question and explain why it is interesting. Will the answer fill a gap in the literature? Will it provide a test of an important theory? Does it have practical implications? Giving readers a clear sense of what the research is about and why they should care about it will motivate them to continue reading the literature review—and will help them make sense of it.

Breaking the Rules

Researcher Larry Jacoby reported several studies showing that a word that people see or hear repeatedly can seem more familiar even when they do not recall the repetitions—and that this tendency is especially pronounced among older adults. He opened his article with the following humourous anecdote:

A friend whose mother is suffering symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) tells the story of taking her mother to visit a nursing home, preliminary to her mother’s moving there. During an orientation meeting at the nursing home, the rules and regulations were explained, one of which regarded the dining room. The dining room was described as similar to a fine restaurant except that tipping was not required. The absence of tipping was a central theme in the orientation lecture, mentioned frequently to emphasize the quality of care along with the advantages of having paid in advance. At the end of the meeting, the friend’s mother was asked whether she had any questions. She replied that she only had one question: “Should I tip?” (Jacoby, 1999, p. 3)

Although both humour and personal anecdotes are generally discouraged in APA-style writing, this example is a highly effective way to start because it both engages the reader and provides an excellent real-world example of the topic under study.

The Literature Review

Immediately after the opening comes the literature review , which describes relevant previous research on the topic and can be anywhere from several paragraphs to several pages in length. However, the literature review is not simply a list of past studies. Instead, it constitutes a kind of argument for why the research question is worth addressing. By the end of the literature review, readers should be convinced that the research question makes sense and that the present study is a logical next step in the ongoing research process.

Like any effective argument, the literature review must have some kind of structure. For example, it might begin by describing a phenomenon in a general way along with several studies that demonstrate it, then describing two or more competing theories of the phenomenon, and finally presenting a hypothesis to test one or more of the theories. Or it might describe one phenomenon, then describe another phenomenon that seems inconsistent with the first one, then propose a theory that resolves the inconsistency, and finally present a hypothesis to test that theory. In applied research, it might describe a phenomenon or theory, then describe how that phenomenon or theory applies to some important real-world situation, and finally suggest a way to test whether it does, in fact, apply to that situation.

Looking at the literature review in this way emphasizes a few things. First, it is extremely important to start with an outline of the main points that you want to make, organized in the order that you want to make them. The basic structure of your argument, then, should be apparent from the outline itself. Second, it is important to emphasize the structure of your argument in your writing. One way to do this is to begin the literature review by summarizing your argument even before you begin to make it. “In this article, I will describe two apparently contradictory phenomena, present a new theory that has the potential to resolve the apparent contradiction, and finally present a novel hypothesis to test the theory.” Another way is to open each paragraph with a sentence that summarizes the main point of the paragraph and links it to the preceding points. These opening sentences provide the “transitions” that many beginning researchers have difficulty with. Instead of beginning a paragraph by launching into a description of a previous study, such as “Williams (2004) found that…,” it is better to start by indicating something about why you are describing this particular study. Here are some simple examples:

Another example of this phenomenon comes from the work of Williams (2004).

Williams (2004) offers one explanation of this phenomenon.

An alternative perspective has been provided by Williams (2004).

We used a method based on the one used by Williams (2004).

Finally, remember that your goal is to construct an argument for why your research question is interesting and worth addressing—not necessarily why your favourite answer to it is correct. In other words, your literature review must be balanced. If you want to emphasize the generality of a phenomenon, then of course you should discuss various studies that have demonstrated it. However, if there are other studies that have failed to demonstrate it, you should discuss them too. Or if you are proposing a new theory, then of course you should discuss findings that are consistent with that theory. However, if there are other findings that are inconsistent with it, again, you should discuss them too. It is acceptable to argue that the balance of the research supports the existence of a phenomenon or is consistent with a theory (and that is usually the best that researchers in psychology can hope for), but it is not acceptable to ignore contradictory evidence. Besides, a large part of what makes a research question interesting is uncertainty about its answer.

The Closing

The closing of the introduction—typically the final paragraph or two—usually includes two important elements. The first is a clear statement of the main research question or hypothesis. This statement tends to be more formal and precise than in the opening and is often expressed in terms of operational definitions of the key variables. The second is a brief overview of the method and some comment on its appropriateness. Here, for example, is how Darley and Latané (1968) [2] concluded the introduction to their classic article on the bystander effect:

These considerations lead to the hypothesis that the more bystanders to an emergency, the less likely, or the more slowly, any one bystander will intervene to provide aid. To test this proposition it would be necessary to create a situation in which a realistic “emergency” could plausibly occur. Each subject should also be blocked from communicating with others to prevent his getting information about their behaviour during the emergency. Finally, the experimental situation should allow for the assessment of the speed and frequency of the subjects’ reaction to the emergency. The experiment reported below attempted to fulfill these conditions. (p. 378)

Thus the introduction leads smoothly into the next major section of the article—the method section.

The method section is where you describe how you conducted your study. An important principle for writing a method section is that it should be clear and detailed enough that other researchers could replicate the study by following your “recipe.” This means that it must describe all the important elements of the study—basic demographic characteristics of the participants, how they were recruited, whether they were randomly assigned, how the variables were manipulated or measured, how counterbalancing was accomplished, and so on. At the same time, it should avoid irrelevant details such as the fact that the study was conducted in Classroom 37B of the Industrial Technology Building or that the questionnaire was double-sided and completed using pencils.

The method section begins immediately after the introduction ends with the heading “Method” (not “Methods”) centred on the page. Immediately after this is the subheading “Participants,” left justified and in italics. The participants subsection indicates how many participants there were, the number of women and men, some indication of their age, other demographics that may be relevant to the study, and how they were recruited, including any incentives given for participation.

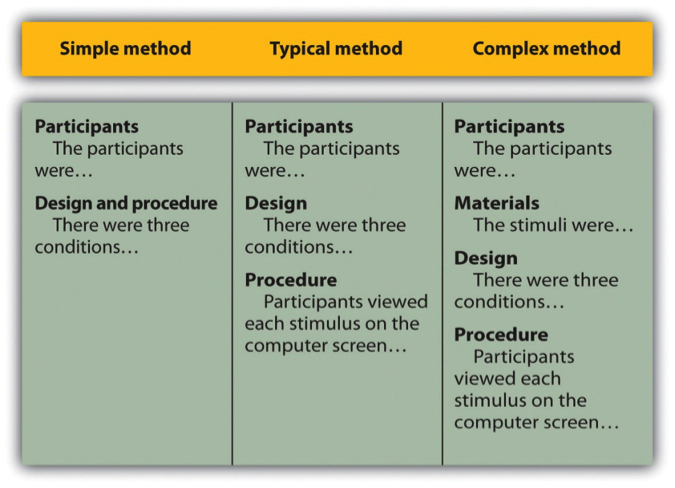

After the participants section, the structure can vary a bit. Figure 11.1 shows three common approaches. In the first, the participants section is followed by a design and procedure subsection, which describes the rest of the method. This works well for methods that are relatively simple and can be described adequately in a few paragraphs. In the second approach, the participants section is followed by separate design and procedure subsections. This works well when both the design and the procedure are relatively complicated and each requires multiple paragraphs.

What is the difference between design and procedure? The design of a study is its overall structure. What were the independent and dependent variables? Was the independent variable manipulated, and if so, was it manipulated between or within subjects? How were the variables operationally defined? The procedure is how the study was carried out. It often works well to describe the procedure in terms of what the participants did rather than what the researchers did. For example, the participants gave their informed consent, read a set of instructions, completed a block of four practice trials, completed a block of 20 test trials, completed two questionnaires, and were debriefed and excused.

In the third basic way to organize a method section, the participants subsection is followed by a materials subsection before the design and procedure subsections. This works well when there are complicated materials to describe. This might mean multiple questionnaires, written vignettes that participants read and respond to, perceptual stimuli, and so on. The heading of this subsection can be modified to reflect its content. Instead of “Materials,” it can be “Questionnaires,” “Stimuli,” and so on.

The results section is where you present the main results of the study, including the results of the statistical analyses. Although it does not include the raw data—individual participants’ responses or scores—researchers should save their raw data and make them available to other researchers who request them. Several journals now encourage the open sharing of raw data online.

Although there are no standard subsections, it is still important for the results section to be logically organized. Typically it begins with certain preliminary issues. One is whether any participants or responses were excluded from the analyses and why. The rationale for excluding data should be described clearly so that other researchers can decide whether it is appropriate. A second preliminary issue is how multiple responses were combined to produce the primary variables in the analyses. For example, if participants rated the attractiveness of 20 stimulus people, you might have to explain that you began by computing the mean attractiveness rating for each participant. Or if they recalled as many items as they could from study list of 20 words, did you count the number correctly recalled, compute the percentage correctly recalled, or perhaps compute the number correct minus the number incorrect? A third preliminary issue is the reliability of the measures. This is where you would present test-retest correlations, Cronbach’s α, or other statistics to show that the measures are consistent across time and across items. A final preliminary issue is whether the manipulation was successful. This is where you would report the results of any manipulation checks.

The results section should then tackle the primary research questions, one at a time. Again, there should be a clear organization. One approach would be to answer the most general questions and then proceed to answer more specific ones. Another would be to answer the main question first and then to answer secondary ones. Regardless, Bem (2003) [3] suggests the following basic structure for discussing each new result:

- Remind the reader of the research question.

- Give the answer to the research question in words.

- Present the relevant statistics.

- Qualify the answer if necessary.

- Summarize the result.

Notice that only Step 3 necessarily involves numbers. The rest of the steps involve presenting the research question and the answer to it in words. In fact, the basic results should be clear even to a reader who skips over the numbers.

The discussion is the last major section of the research report. Discussions usually consist of some combination of the following elements:

- Summary of the research

- Theoretical implications

- Practical implications

- Limitations

- Suggestions for future research

The discussion typically begins with a summary of the study that provides a clear answer to the research question. In a short report with a single study, this might require no more than a sentence. In a longer report with multiple studies, it might require a paragraph or even two. The summary is often followed by a discussion of the theoretical implications of the research. Do the results provide support for any existing theories? If not, how can they be explained? Although you do not have to provide a definitive explanation or detailed theory for your results, you at least need to outline one or more possible explanations. In applied research—and often in basic research—there is also some discussion of the practical implications of the research. How can the results be used, and by whom, to accomplish some real-world goal?

The theoretical and practical implications are often followed by a discussion of the study’s limitations. Perhaps there are problems with its internal or external validity. Perhaps the manipulation was not very effective or the measures not very reliable. Perhaps there is some evidence that participants did not fully understand their task or that they were suspicious of the intent of the researchers. Now is the time to discuss these issues and how they might have affected the results. But do not overdo it. All studies have limitations, and most readers will understand that a different sample or different measures might have produced different results. Unless there is good reason to think they would have, however, there is no reason to mention these routine issues. Instead, pick two or three limitations that seem like they could have influenced the results, explain how they could have influenced the results, and suggest ways to deal with them.

Most discussions end with some suggestions for future research. If the study did not satisfactorily answer the original research question, what will it take to do so? What new research questions has the study raised? This part of the discussion, however, is not just a list of new questions. It is a discussion of two or three of the most important unresolved issues. This means identifying and clarifying each question, suggesting some alternative answers, and even suggesting ways they could be studied.

Finally, some researchers are quite good at ending their articles with a sweeping or thought-provoking conclusion. Darley and Latané (1968) [4] , for example, ended their article on the bystander effect by discussing the idea that whether people help others may depend more on the situation than on their personalities. Their final sentence is, “If people understand the situational forces that can make them hesitate to intervene, they may better overcome them” (p. 383). However, this kind of ending can be difficult to pull off. It can sound overreaching or just banal and end up detracting from the overall impact of the article. It is often better simply to end when you have made your final point (although you should avoid ending on a limitation).

The references section begins on a new page with the heading “References” centred at the top of the page. All references cited in the text are then listed in the format presented earlier. They are listed alphabetically by the last name of the first author. If two sources have the same first author, they are listed alphabetically by the last name of the second author. If all the authors are the same, then they are listed chronologically by the year of publication. Everything in the reference list is double-spaced both within and between references.

Appendices, Tables, and Figures

Appendices, tables, and figures come after the references. An appendix is appropriate for supplemental material that would interrupt the flow of the research report if it were presented within any of the major sections. An appendix could be used to present lists of stimulus words, questionnaire items, detailed descriptions of special equipment or unusual statistical analyses, or references to the studies that are included in a meta-analysis. Each appendix begins on a new page. If there is only one, the heading is “Appendix,” centred at the top of the page. If there is more than one, the headings are “Appendix A,” “Appendix B,” and so on, and they appear in the order they were first mentioned in the text of the report.

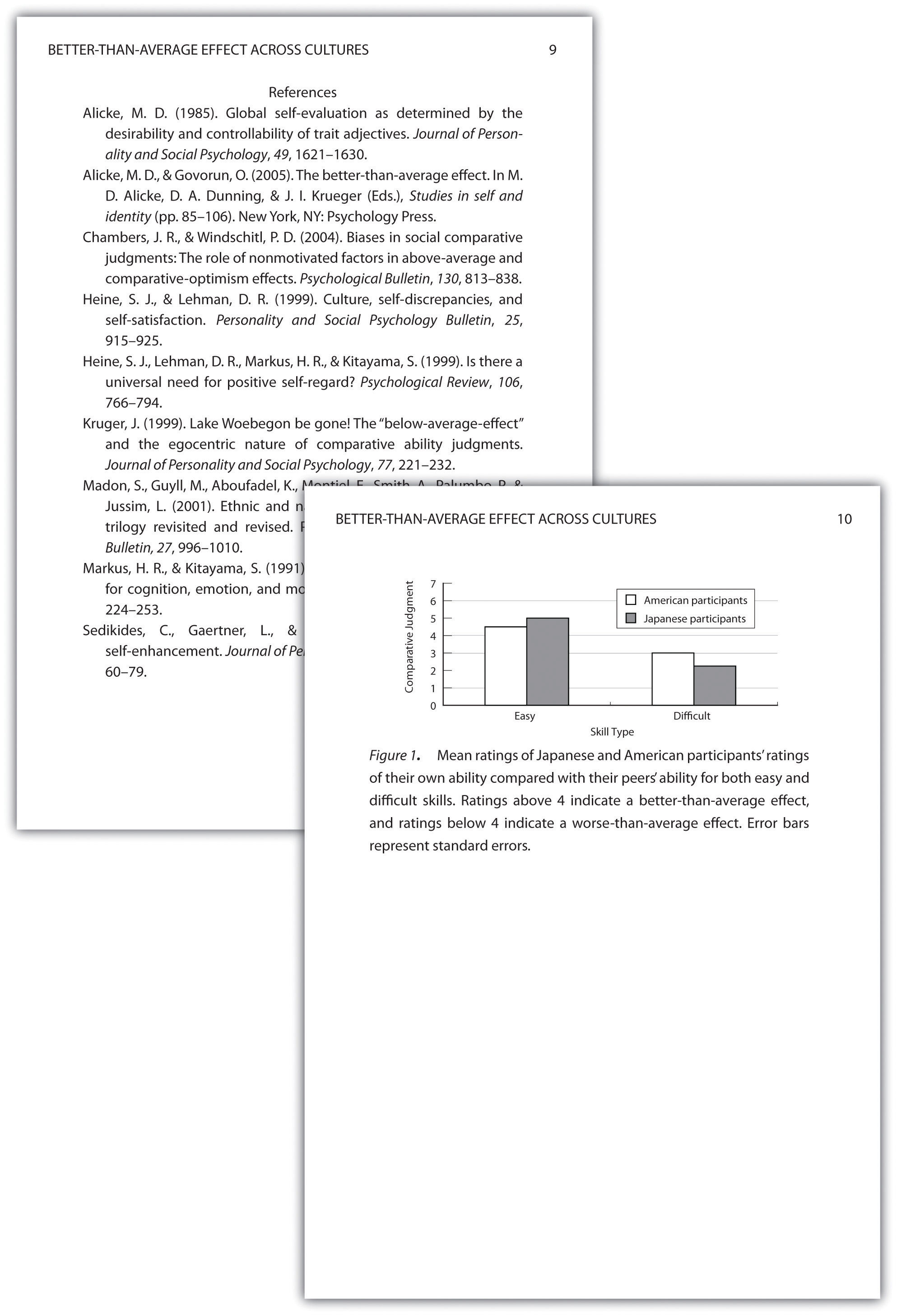

After any appendices come tables and then figures. Tables and figures are both used to present results. Figures can also be used to illustrate theories (e.g., in the form of a flowchart), display stimuli, outline procedures, and present many other kinds of information. Each table and figure appears on its own page. Tables are numbered in the order that they are first mentioned in the text (“Table 1,” “Table 2,” and so on). Figures are numbered the same way (“Figure 1,” “Figure 2,” and so on). A brief explanatory title, with the important words capitalized, appears above each table. Each figure is given a brief explanatory caption, where (aside from proper nouns or names) only the first word of each sentence is capitalized. More details on preparing APA-style tables and figures are presented later in the book.

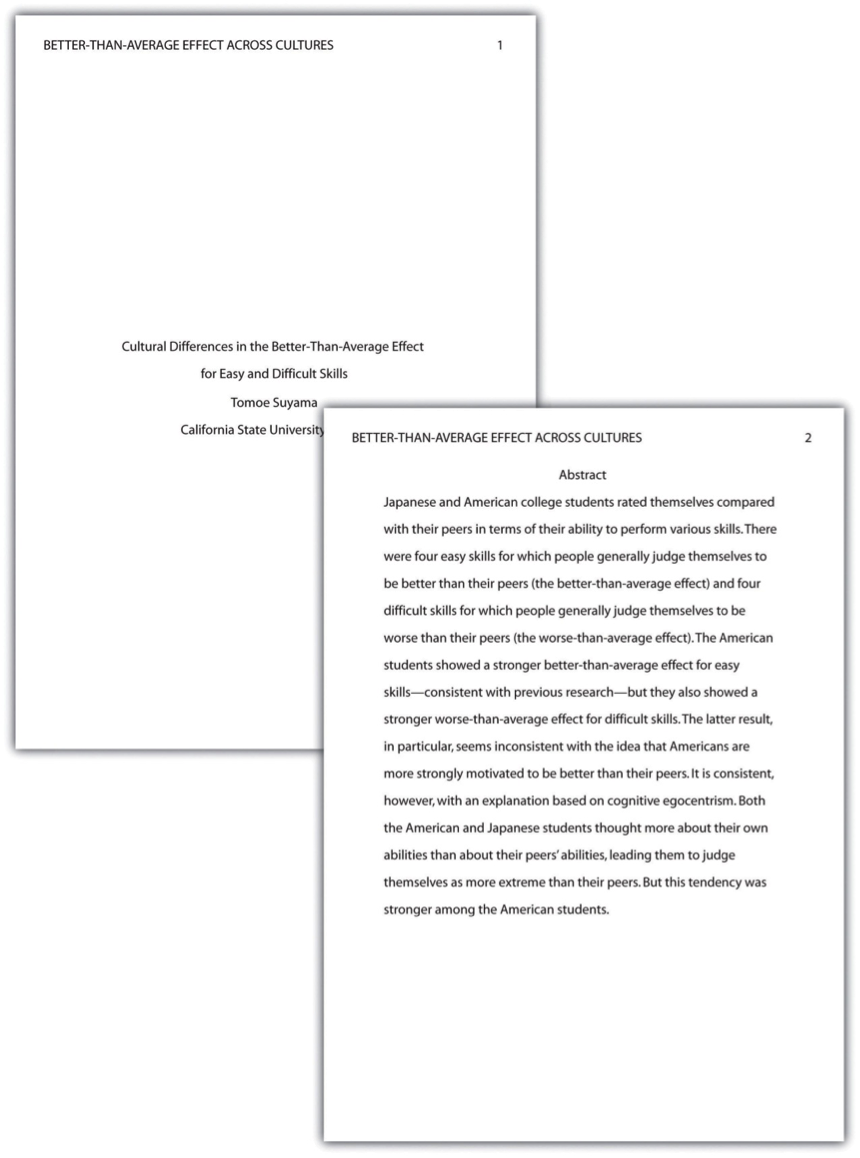

Sample APA-Style Research Report

Figures 11.2, 11.3, 11.4, and 11.5 show some sample pages from an APA-style empirical research report originally written by undergraduate student Tomoe Suyama at California State University, Fresno. The main purpose of these figures is to illustrate the basic organization and formatting of an APA-style empirical research report, although many high-level and low-level style conventions can be seen here too.

Key Takeaways

- An APA-style empirical research report consists of several standard sections. The main ones are the abstract, introduction, method, results, discussion, and references.

- The introduction consists of an opening that presents the research question, a literature review that describes previous research on the topic, and a closing that restates the research question and comments on the method. The literature review constitutes an argument for why the current study is worth doing.

- The method section describes the method in enough detail that another researcher could replicate the study. At a minimum, it consists of a participants subsection and a design and procedure subsection.

- The results section describes the results in an organized fashion. Each primary result is presented in terms of statistical results but also explained in words.

- The discussion typically summarizes the study, discusses theoretical and practical implications and limitations of the study, and offers suggestions for further research.

- Practice: Look through an issue of a general interest professional journal (e.g., Psychological Science ). Read the opening of the first five articles and rate the effectiveness of each one from 1 ( very ineffective ) to 5 ( very effective ). Write a sentence or two explaining each rating.

- Practice: Find a recent article in a professional journal and identify where the opening, literature review, and closing of the introduction begin and end.

- Practice: Find a recent article in a professional journal and highlight in a different colour each of the following elements in the discussion: summary, theoretical implications, practical implications, limitations, and suggestions for future research.

Long Descriptions

Figure 11.1 long description: Table showing three ways of organizing an APA-style method section.

In the simple method, there are two subheadings: “Participants” (which might begin “The participants were…”) and “Design and procedure” (which might begin “There were three conditions…”).

In the typical method, there are three subheadings: “Participants” (“The participants were…”), “Design” (“There were three conditions…”), and “Procedure” (“Participants viewed each stimulus on the computer screen…”).

In the complex method, there are four subheadings: “Participants” (“The participants were…”), “Materials” (“The stimuli were…”), “Design” (“There were three conditions…”), and “Procedure” (“Participants viewed each stimulus on the computer screen…”). [Return to Figure 11.1]

- Bem, D. J. (2003). Writing the empirical journal article. In J. M. Darley, M. P. Zanna, & H. R. Roediger III (Eds.), The compleat academic: A practical guide for the beginning social scientist (2nd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. ↵

- Darley, J. M., & Latané, B. (1968). Bystander intervention in emergencies: Diffusion of responsibility. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 4 , 377–383. ↵

A type of research article which describes one or more new empirical studies conducted by the authors.

The page at the beginning of an APA-style research report containing the title of the article, the authors’ names, and their institutional affiliation.

A summary of a research study.

The third page of a manuscript containing the research question, the literature review, and comments about how to answer the research question.

An introduction to the research question and explanation for why this question is interesting.

A description of relevant previous research on the topic being discusses and an argument for why the research is worth addressing.

The end of the introduction, where the research question is reiterated and the method is commented upon.

The section of a research report where the method used to conduct the study is described.

The main results of the study, including the results from statistical analyses, are presented in a research article.

Section of a research report that summarizes the study's results and interprets them by referring back to the study's theoretical background.

Part of a research report which contains supplemental material.

Research Methods in Psychology - 2nd Canadian Edition Copyright © 2015 by Paul C. Price, Rajiv Jhangiani, & I-Chant A. Chiang is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Research Reports: Definition and How to Write Them

Reports are usually spread across a vast horizon of topics but are focused on communicating information about a particular topic and a niche target market. The primary motive of research reports is to convey integral details about a study for marketers to consider while designing new strategies.

Certain events, facts, and other information based on incidents need to be relayed to the people in charge, and creating research reports is the most effective communication tool. Ideal research reports are extremely accurate in the offered information with a clear objective and conclusion. These reports should have a clean and structured format to relay information effectively.

What are Research Reports?

Research reports are recorded data prepared by researchers or statisticians after analyzing the information gathered by conducting organized research, typically in the form of surveys or qualitative methods .

A research report is a reliable source to recount details about a conducted research. It is most often considered to be a true testimony of all the work done to garner specificities of research.

The various sections of a research report are:

- Background/Introduction

- Implemented Methods

- Results based on Analysis

- Deliberation

Learn more: Quantitative Research

Components of Research Reports

Research is imperative for launching a new product/service or a new feature. The markets today are extremely volatile and competitive due to new entrants every day who may or may not provide effective products. An organization needs to make the right decisions at the right time to be relevant in such a market with updated products that suffice customer demands.

The details of a research report may change with the purpose of research but the main components of a report will remain constant. The research approach of the market researcher also influences the style of writing reports. Here are seven main components of a productive research report:

- Research Report Summary: The entire objective along with the overview of research are to be included in a summary which is a couple of paragraphs in length. All the multiple components of the research are explained in brief under the report summary. It should be interesting enough to capture all the key elements of the report.

- Research Introduction: There always is a primary goal that the researcher is trying to achieve through a report. In the introduction section, he/she can cover answers related to this goal and establish a thesis which will be included to strive and answer it in detail. This section should answer an integral question: “What is the current situation of the goal?”. After the research design was conducted, did the organization conclude the goal successfully or they are still a work in progress – provide such details in the introduction part of the research report.

- Research Methodology: This is the most important section of the report where all the important information lies. The readers can gain data for the topic along with analyzing the quality of provided content and the research can also be approved by other market researchers . Thus, this section needs to be highly informative with each aspect of research discussed in detail. Information needs to be expressed in chronological order according to its priority and importance. Researchers should include references in case they gained information from existing techniques.

- Research Results: A short description of the results along with calculations conducted to achieve the goal will form this section of results. Usually, the exposition after data analysis is carried out in the discussion part of the report.

Learn more: Quantitative Data

- Research Discussion: The results are discussed in extreme detail in this section along with a comparative analysis of reports that could probably exist in the same domain. Any abnormality uncovered during research will be deliberated in the discussion section. While writing research reports, the researcher will have to connect the dots on how the results will be applicable in the real world.

- Research References and Conclusion: Conclude all the research findings along with mentioning each and every author, article or any content piece from where references were taken.

Learn more: Qualitative Observation

15 Tips for Writing Research Reports

Writing research reports in the manner can lead to all the efforts going down the drain. Here are 15 tips for writing impactful research reports:

- Prepare the context before starting to write and start from the basics: This was always taught to us in school – be well-prepared before taking a plunge into new topics. The order of survey questions might not be the ideal or most effective order for writing research reports. The idea is to start with a broader topic and work towards a more specific one and focus on a conclusion or support, which a research should support with the facts. The most difficult thing to do in reporting, without a doubt is to start. Start with the title, the introduction, then document the first discoveries and continue from that. Once the marketers have the information well documented, they can write a general conclusion.

- Keep the target audience in mind while selecting a format that is clear, logical and obvious to them: Will the research reports be presented to decision makers or other researchers? What are the general perceptions around that topic? This requires more care and diligence. A researcher will need a significant amount of information to start writing the research report. Be consistent with the wording, the numbering of the annexes and so on. Follow the approved format of the company for the delivery of research reports and demonstrate the integrity of the project with the objectives of the company.

- Have a clear research objective: A researcher should read the entire proposal again, and make sure that the data they provide contributes to the objectives that were raised from the beginning. Remember that speculations are for conversations, not for research reports, if a researcher speculates, they directly question their own research.

- Establish a working model: Each study must have an internal logic, which will have to be established in the report and in the evidence. The researchers’ worst nightmare is to be required to write research reports and realize that key questions were not included.

Learn more: Quantitative Observation

- Gather all the information about the research topic. Who are the competitors of our customers? Talk to other researchers who have studied the subject of research, know the language of the industry. Misuse of the terms can discourage the readers of research reports from reading further.

- Read aloud while writing. While reading the report, if the researcher hears something inappropriate, for example, if they stumble over the words when reading them, surely the reader will too. If the researcher can’t put an idea in a single sentence, then it is very long and they must change it so that the idea is clear to everyone.

- Check grammar and spelling. Without a doubt, good practices help to understand the report. Use verbs in the present tense. Consider using the present tense, which makes the results sound more immediate. Find new words and other ways of saying things. Have fun with the language whenever possible.

- Discuss only the discoveries that are significant. If some data are not really significant, do not mention them. Remember that not everything is truly important or essential within research reports.

Learn more: Qualitative Data

- Try and stick to the survey questions. For example, do not say that the people surveyed “were worried” about an research issue , when there are different degrees of concern.

- The graphs must be clear enough so that they understand themselves. Do not let graphs lead the reader to make mistakes: give them a title, include the indications, the size of the sample, and the correct wording of the question.

- Be clear with messages. A researcher should always write every section of the report with an accuracy of details and language.

- Be creative with titles – Particularly in segmentation studies choose names “that give life to research”. Such names can survive for a long time after the initial investigation.

- Create an effective conclusion: The conclusion in the research reports is the most difficult to write, but it is an incredible opportunity to excel. Make a precise summary. Sometimes it helps to start the conclusion with something specific, then it describes the most important part of the study, and finally, it provides the implications of the conclusions.

- Get a couple more pair of eyes to read the report. Writers have trouble detecting their own mistakes. But they are responsible for what is presented. Ensure it has been approved by colleagues or friends before sending the find draft out.

Learn more: Market Research and Analysis

MORE LIKE THIS

How Can I Help You? — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Jun 5, 2024

Why Multilingual 360 Feedback Surveys Provide Better Insights

Jun 3, 2024

Raked Weighting: A Key Tool for Accurate Survey Results

May 31, 2024

Top 8 Data Trends to Understand the Future of Data

May 30, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Scientific Reports

What this handout is about.

This handout provides a general guide to writing reports about scientific research you’ve performed. In addition to describing the conventional rules about the format and content of a lab report, we’ll also attempt to convey why these rules exist, so you’ll get a clearer, more dependable idea of how to approach this writing situation. Readers of this handout may also find our handout on writing in the sciences useful.

Background and pre-writing

Why do we write research reports.

You did an experiment or study for your science class, and now you have to write it up for your teacher to review. You feel that you understood the background sufficiently, designed and completed the study effectively, obtained useful data, and can use those data to draw conclusions about a scientific process or principle. But how exactly do you write all that? What is your teacher expecting to see?

To take some of the guesswork out of answering these questions, try to think beyond the classroom setting. In fact, you and your teacher are both part of a scientific community, and the people who participate in this community tend to share the same values. As long as you understand and respect these values, your writing will likely meet the expectations of your audience—including your teacher.

So why are you writing this research report? The practical answer is “Because the teacher assigned it,” but that’s classroom thinking. Generally speaking, people investigating some scientific hypothesis have a responsibility to the rest of the scientific world to report their findings, particularly if these findings add to or contradict previous ideas. The people reading such reports have two primary goals:

- They want to gather the information presented.

- They want to know that the findings are legitimate.

Your job as a writer, then, is to fulfill these two goals.

How do I do that?

Good question. Here is the basic format scientists have designed for research reports:

- Introduction

Methods and Materials

This format, sometimes called “IMRAD,” may take slightly different shapes depending on the discipline or audience; some ask you to include an abstract or separate section for the hypothesis, or call the Discussion section “Conclusions,” or change the order of the sections (some professional and academic journals require the Methods section to appear last). Overall, however, the IMRAD format was devised to represent a textual version of the scientific method.

The scientific method, you’ll probably recall, involves developing a hypothesis, testing it, and deciding whether your findings support the hypothesis. In essence, the format for a research report in the sciences mirrors the scientific method but fleshes out the process a little. Below, you’ll find a table that shows how each written section fits into the scientific method and what additional information it offers the reader.

Thinking of your research report as based on the scientific method, but elaborated in the ways described above, may help you to meet your audience’s expectations successfully. We’re going to proceed by explicitly connecting each section of the lab report to the scientific method, then explaining why and how you need to elaborate that section.

Although this handout takes each section in the order in which it should be presented in the final report, you may for practical reasons decide to compose sections in another order. For example, many writers find that composing their Methods and Results before the other sections helps to clarify their idea of the experiment or study as a whole. You might consider using each assignment to practice different approaches to drafting the report, to find the order that works best for you.

What should I do before drafting the lab report?

The best way to prepare to write the lab report is to make sure that you fully understand everything you need to about the experiment. Obviously, if you don’t quite know what went on during the lab, you’re going to find it difficult to explain the lab satisfactorily to someone else. To make sure you know enough to write the report, complete the following steps:

- What are we going to do in this lab? (That is, what’s the procedure?)

- Why are we going to do it that way?

- What are we hoping to learn from this experiment?

- Why would we benefit from this knowledge?

- Consult your lab supervisor as you perform the lab. If you don’t know how to answer one of the questions above, for example, your lab supervisor will probably be able to explain it to you (or, at least, help you figure it out).

- Plan the steps of the experiment carefully with your lab partners. The less you rush, the more likely it is that you’ll perform the experiment correctly and record your findings accurately. Also, take some time to think about the best way to organize the data before you have to start putting numbers down. If you can design a table to account for the data, that will tend to work much better than jotting results down hurriedly on a scrap piece of paper.

- Record the data carefully so you get them right. You won’t be able to trust your conclusions if you have the wrong data, and your readers will know you messed up if the other three people in your group have “97 degrees” and you have “87.”

- Consult with your lab partners about everything you do. Lab groups often make one of two mistakes: two people do all the work while two have a nice chat, or everybody works together until the group finishes gathering the raw data, then scrams outta there. Collaborate with your partners, even when the experiment is “over.” What trends did you observe? Was the hypothesis supported? Did you all get the same results? What kind of figure should you use to represent your findings? The whole group can work together to answer these questions.

- Consider your audience. You may believe that audience is a non-issue: it’s your lab TA, right? Well, yes—but again, think beyond the classroom. If you write with only your lab instructor in mind, you may omit material that is crucial to a complete understanding of your experiment, because you assume the instructor knows all that stuff already. As a result, you may receive a lower grade, since your TA won’t be sure that you understand all the principles at work. Try to write towards a student in the same course but a different lab section. That student will have a fair degree of scientific expertise but won’t know much about your experiment particularly. Alternatively, you could envision yourself five years from now, after the reading and lectures for this course have faded a bit. What would you remember, and what would you need explained more clearly (as a refresher)?

Once you’ve completed these steps as you perform the experiment, you’ll be in a good position to draft an effective lab report.

Introductions

How do i write a strong introduction.

For the purposes of this handout, we’ll consider the Introduction to contain four basic elements: the purpose, the scientific literature relevant to the subject, the hypothesis, and the reasons you believed your hypothesis viable. Let’s start by going through each element of the Introduction to clarify what it covers and why it’s important. Then we can formulate a logical organizational strategy for the section.

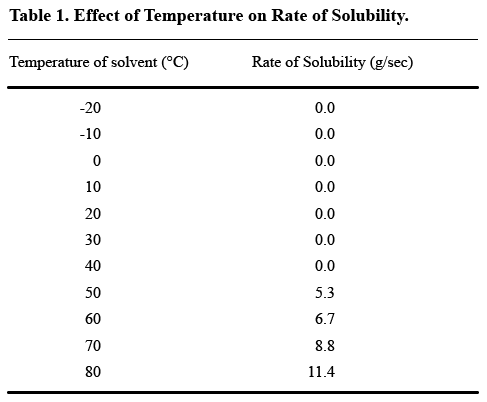

The inclusion of the purpose (sometimes called the objective) of the experiment often confuses writers. The biggest misconception is that the purpose is the same as the hypothesis. Not quite. We’ll get to hypotheses in a minute, but basically they provide some indication of what you expect the experiment to show. The purpose is broader, and deals more with what you expect to gain through the experiment. In a professional setting, the hypothesis might have something to do with how cells react to a certain kind of genetic manipulation, but the purpose of the experiment is to learn more about potential cancer treatments. Undergraduate reports don’t often have this wide-ranging a goal, but you should still try to maintain the distinction between your hypothesis and your purpose. In a solubility experiment, for example, your hypothesis might talk about the relationship between temperature and the rate of solubility, but the purpose is probably to learn more about some specific scientific principle underlying the process of solubility.

For starters, most people say that you should write out your working hypothesis before you perform the experiment or study. Many beginning science students neglect to do so and find themselves struggling to remember precisely which variables were involved in the process or in what way the researchers felt that they were related. Write your hypothesis down as you develop it—you’ll be glad you did.

As for the form a hypothesis should take, it’s best not to be too fancy or complicated; an inventive style isn’t nearly so important as clarity here. There’s nothing wrong with beginning your hypothesis with the phrase, “It was hypothesized that . . .” Be as specific as you can about the relationship between the different objects of your study. In other words, explain that when term A changes, term B changes in this particular way. Readers of scientific writing are rarely content with the idea that a relationship between two terms exists—they want to know what that relationship entails.

Not a hypothesis:

“It was hypothesized that there is a significant relationship between the temperature of a solvent and the rate at which a solute dissolves.”

Hypothesis:

“It was hypothesized that as the temperature of a solvent increases, the rate at which a solute will dissolve in that solvent increases.”

Put more technically, most hypotheses contain both an independent and a dependent variable. The independent variable is what you manipulate to test the reaction; the dependent variable is what changes as a result of your manipulation. In the example above, the independent variable is the temperature of the solvent, and the dependent variable is the rate of solubility. Be sure that your hypothesis includes both variables.

Justify your hypothesis

You need to do more than tell your readers what your hypothesis is; you also need to assure them that this hypothesis was reasonable, given the circumstances. In other words, use the Introduction to explain that you didn’t just pluck your hypothesis out of thin air. (If you did pluck it out of thin air, your problems with your report will probably extend beyond using the appropriate format.) If you posit that a particular relationship exists between the independent and the dependent variable, what led you to believe your “guess” might be supported by evidence?

Scientists often refer to this type of justification as “motivating” the hypothesis, in the sense that something propelled them to make that prediction. Often, motivation includes what we already know—or rather, what scientists generally accept as true (see “Background/previous research” below). But you can also motivate your hypothesis by relying on logic or on your own observations. If you’re trying to decide which solutes will dissolve more rapidly in a solvent at increased temperatures, you might remember that some solids are meant to dissolve in hot water (e.g., bouillon cubes) and some are used for a function precisely because they withstand higher temperatures (they make saucepans out of something). Or you can think about whether you’ve noticed sugar dissolving more rapidly in your glass of iced tea or in your cup of coffee. Even such basic, outside-the-lab observations can help you justify your hypothesis as reasonable.

Background/previous research

This part of the Introduction demonstrates to the reader your awareness of how you’re building on other scientists’ work. If you think of the scientific community as engaging in a series of conversations about various topics, then you’ll recognize that the relevant background material will alert the reader to which conversation you want to enter.

Generally speaking, authors writing journal articles use the background for slightly different purposes than do students completing assignments. Because readers of academic journals tend to be professionals in the field, authors explain the background in order to permit readers to evaluate the study’s pertinence for their own work. You, on the other hand, write toward a much narrower audience—your peers in the course or your lab instructor—and so you must demonstrate that you understand the context for the (presumably assigned) experiment or study you’ve completed. For example, if your professor has been talking about polarity during lectures, and you’re doing a solubility experiment, you might try to connect the polarity of a solid to its relative solubility in certain solvents. In any event, both professional researchers and undergraduates need to connect the background material overtly to their own work.

Organization of this section

Most of the time, writers begin by stating the purpose or objectives of their own work, which establishes for the reader’s benefit the “nature and scope of the problem investigated” (Day 1994). Once you have expressed your purpose, you should then find it easier to move from the general purpose, to relevant material on the subject, to your hypothesis. In abbreviated form, an Introduction section might look like this:

“The purpose of the experiment was to test conventional ideas about solubility in the laboratory [purpose] . . . According to Whitecoat and Labrat (1999), at higher temperatures the molecules of solvents move more quickly . . . We know from the class lecture that molecules moving at higher rates of speed collide with one another more often and thus break down more easily [background material/motivation] . . . Thus, it was hypothesized that as the temperature of a solvent increases, the rate at which a solute will dissolve in that solvent increases [hypothesis].”

Again—these are guidelines, not commandments. Some writers and readers prefer different structures for the Introduction. The one above merely illustrates a common approach to organizing material.

How do I write a strong Materials and Methods section?

As with any piece of writing, your Methods section will succeed only if it fulfills its readers’ expectations, so you need to be clear in your own mind about the purpose of this section. Let’s review the purpose as we described it above: in this section, you want to describe in detail how you tested the hypothesis you developed and also to clarify the rationale for your procedure. In science, it’s not sufficient merely to design and carry out an experiment. Ultimately, others must be able to verify your findings, so your experiment must be reproducible, to the extent that other researchers can follow the same procedure and obtain the same (or similar) results.

Here’s a real-world example of the importance of reproducibility. In 1989, physicists Stanley Pons and Martin Fleischman announced that they had discovered “cold fusion,” a way of producing excess heat and power without the nuclear radiation that accompanies “hot fusion.” Such a discovery could have great ramifications for the industrial production of energy, so these findings created a great deal of interest. When other scientists tried to duplicate the experiment, however, they didn’t achieve the same results, and as a result many wrote off the conclusions as unjustified (or worse, a hoax). To this day, the viability of cold fusion is debated within the scientific community, even though an increasing number of researchers believe it possible. So when you write your Methods section, keep in mind that you need to describe your experiment well enough to allow others to replicate it exactly.

With these goals in mind, let’s consider how to write an effective Methods section in terms of content, structure, and style.

Sometimes the hardest thing about writing this section isn’t what you should talk about, but what you shouldn’t talk about. Writers often want to include the results of their experiment, because they measured and recorded the results during the course of the experiment. But such data should be reserved for the Results section. In the Methods section, you can write that you recorded the results, or how you recorded the results (e.g., in a table), but you shouldn’t write what the results were—not yet. Here, you’re merely stating exactly how you went about testing your hypothesis. As you draft your Methods section, ask yourself the following questions:

- How much detail? Be precise in providing details, but stay relevant. Ask yourself, “Would it make any difference if this piece were a different size or made from a different material?” If not, you probably don’t need to get too specific. If so, you should give as many details as necessary to prevent this experiment from going awry if someone else tries to carry it out. Probably the most crucial detail is measurement; you should always quantify anything you can, such as time elapsed, temperature, mass, volume, etc.

- Rationale: Be sure that as you’re relating your actions during the experiment, you explain your rationale for the protocol you developed. If you capped a test tube immediately after adding a solute to a solvent, why did you do that? (That’s really two questions: why did you cap it, and why did you cap it immediately?) In a professional setting, writers provide their rationale as a way to explain their thinking to potential critics. On one hand, of course, that’s your motivation for talking about protocol, too. On the other hand, since in practical terms you’re also writing to your teacher (who’s seeking to evaluate how well you comprehend the principles of the experiment), explaining the rationale indicates that you understand the reasons for conducting the experiment in that way, and that you’re not just following orders. Critical thinking is crucial—robots don’t make good scientists.

- Control: Most experiments will include a control, which is a means of comparing experimental results. (Sometimes you’ll need to have more than one control, depending on the number of hypotheses you want to test.) The control is exactly the same as the other items you’re testing, except that you don’t manipulate the independent variable-the condition you’re altering to check the effect on the dependent variable. For example, if you’re testing solubility rates at increased temperatures, your control would be a solution that you didn’t heat at all; that way, you’ll see how quickly the solute dissolves “naturally” (i.e., without manipulation), and you’ll have a point of reference against which to compare the solutions you did heat.

Describe the control in the Methods section. Two things are especially important in writing about the control: identify the control as a control, and explain what you’re controlling for. Here is an example:

“As a control for the temperature change, we placed the same amount of solute in the same amount of solvent, and let the solution stand for five minutes without heating it.”

Structure and style

Organization is especially important in the Methods section of a lab report because readers must understand your experimental procedure completely. Many writers are surprised by the difficulty of conveying what they did during the experiment, since after all they’re only reporting an event, but it’s often tricky to present this information in a coherent way. There’s a fairly standard structure you can use to guide you, and following the conventions for style can help clarify your points.

- Subsections: Occasionally, researchers use subsections to report their procedure when the following circumstances apply: 1) if they’ve used a great many materials; 2) if the procedure is unusually complicated; 3) if they’ve developed a procedure that won’t be familiar to many of their readers. Because these conditions rarely apply to the experiments you’ll perform in class, most undergraduate lab reports won’t require you to use subsections. In fact, many guides to writing lab reports suggest that you try to limit your Methods section to a single paragraph.

- Narrative structure: Think of this section as telling a story about a group of people and the experiment they performed. Describe what you did in the order in which you did it. You may have heard the old joke centered on the line, “Disconnect the red wire, but only after disconnecting the green wire,” where the person reading the directions blows everything to kingdom come because the directions weren’t in order. We’re used to reading about events chronologically, and so your readers will generally understand what you did if you present that information in the same way. Also, since the Methods section does generally appear as a narrative (story), you want to avoid the “recipe” approach: “First, take a clean, dry 100 ml test tube from the rack. Next, add 50 ml of distilled water.” You should be reporting what did happen, not telling the reader how to perform the experiment: “50 ml of distilled water was poured into a clean, dry 100 ml test tube.” Hint: most of the time, the recipe approach comes from copying down the steps of the procedure from your lab manual, so you may want to draft the Methods section initially without consulting your manual. Later, of course, you can go back and fill in any part of the procedure you inadvertently overlooked.

- Past tense: Remember that you’re describing what happened, so you should use past tense to refer to everything you did during the experiment. Writers are often tempted to use the imperative (“Add 5 g of the solid to the solution”) because that’s how their lab manuals are worded; less frequently, they use present tense (“5 g of the solid are added to the solution”). Instead, remember that you’re talking about an event which happened at a particular time in the past, and which has already ended by the time you start writing, so simple past tense will be appropriate in this section (“5 g of the solid were added to the solution” or “We added 5 g of the solid to the solution”).

- Active: We heated the solution to 80°C. (The subject, “we,” performs the action, heating.)

- Passive: The solution was heated to 80°C. (The subject, “solution,” doesn’t do the heating–it is acted upon, not acting.)

Increasingly, especially in the social sciences, using first person and active voice is acceptable in scientific reports. Most readers find that this style of writing conveys information more clearly and concisely. This rhetorical choice thus brings two scientific values into conflict: objectivity versus clarity. Since the scientific community hasn’t reached a consensus about which style it prefers, you may want to ask your lab instructor.

How do I write a strong Results section?