2.1 Why is Research Important

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how scientific research addresses questions about behavior

- Discuss how scientific research guides public policy

- Appreciate how scientific research can be important in making personal decisions

Scientific research is a critical tool for successfully navigating our complex world. Without it, we would be forced to rely solely on intuition, other people’s authority, and blind luck. While many of us feel confident in our abilities to decipher and interact with the world around us, history is filled with examples of how very wrong we can be when we fail to recognize the need for evidence in supporting claims. At various times in history, we would have been certain that the sun revolved around a flat earth, that the earth’s continents did not move, and that mental illness was caused by possession (figure below). It is through systematic scientific research that we divest ourselves of our preconceived notions and superstitions and gain an objective understanding of ourselves and our world.

Some of our ancestors, across the work and over the centuries, believed that trephination – the practice of making a hole in the skull, as shown here – allowed evil spirits to leave the body, thus curing mental illness and other diseases (credit” “taiproject/Flickr)

The goal of all scientists is to better understand the world around them. Psychologists focus their attention on understanding behavior, as well as the cognitive (mental) and physiological (body) processes that underlie behavior. In contrast to other methods that people use to understand the behavior of others, such as intuition and personal experience, the hallmark of scientific research is that there is evidence to support a claim. Scientific knowledge is empirical : It is grounded in objective, tangible evidence that can be observed time and time again, regardless of who is observing.

We can easily observe the behavior of others around us. For example, if someone is crying, we can observe that behavior. However, the reason for the behavior is more difficult to determine. Is the person crying due to being sad, in pain, or happy? Sometimes, asking about the underlying cognitions is as easy as asking the subject directly: “Why are you crying?” However, there are situations in which an individual is either uncomfortable or unwilling to answer the question honestly, or is incapable of answering. For example, infants would not be able to explain why they are crying. In other situations, it may be hard to identify exactly why you feel the way you do. Think about times when you suddenly feel annoyed after a long day. There may be a specific trigger for your annoyance (a loud noise), or you may be tired, hungry, stressed, or all of the above. Human behavior is often a complicated mix of a variety of factors. In such circumstances, the psychologist must be creative in finding ways to better understand behavior. This chapter explores how scientific knowledge is generated, and how important that knowledge is in forming decisions in our personal lives and in the public domain.

USE OF RESEARCH INFORMATION

Trying to determine which theories are and are not accepted by the scientific community can be difficult, especially in an area of research as broad as psychology. More than ever before, we have an incredible amount of information at our fingertips, and a simple internet search on any given research topic might result in a number of contradictory studies. In these cases, we are witnessing the scientific community going through the process of coming to an agreement, and it could be quite some time before a consensus emerges. In other cases, rapidly developing technology is improving our ability to measure things, and changing our earlier understanding of how the mind works.

In the meantime, we should strive to think critically about the information we encounter by exercising a degree of healthy skepticism. When someone makes a claim, we should examine the claim from a number of different perspectives: what is the expertise of the person making the claim, what might they gain if the claim is valid, does the claim seem justified given the evidence, and what do other researchers think of the claim? Science is always changing and new evidence is alwaus coming to light, thus this dash of skepticism should be applied to all research you interact with from now on. Yes, that includes the research presented in this textbook.

Evaluation of research findings can have widespread impact. Imagine that you have been elected as the governor of your state. One of your responsibilities is to manage the state budget and determine how to best spend your constituents’ tax dollars. As the new governor, you need to decide whether to continue funding the D.A.R.E. (Drug Abuse Resistance Education) program in public schools (figure below). This program typically involves police officers coming into the classroom to educate students about the dangers of becoming involved with alcohol and other drugs. According to the D.A.R.E. website (www.dare.org), this program has been very popular since its inception in 1983, and it is currently operating in 75% of school districts in the United States and in more than 40 countries worldwide. Sounds like an easy decision, right? However, on closer review, you discover that the vast majority of research into this program consistently suggests that participation has little, if any, effect on whether or not someone uses alcohol or other drugs (Clayton, Cattarello, & Johnstone, 1996; Ennett, Tobler, Ringwalt, & Flewelling, 1994; Lynam et al., 1999; Ringwalt, Ennett, & Holt, 1991). If you are committed to being a good steward of taxpayer money, will you fund this particular program, or will you try to find other programs that research has consistently demonstrated to be effective?

The D.A.R.E. program continues to be popular in schools around the world despite research suggesting that it is ineffective.

It is not just politicians who can benefit from using research in guiding their decisions. We all might look to research from time to time when making decisions in our lives. Imagine you just found out that a close friend has breast cancer or that one of your young relatives has recently been diagnosed with autism. In either case, you want to know which treatment options are most successful with the fewest side effects. How would you find that out? You would probably talk with a doctor or psychologist and personally review the research that has been done on various treatment options—always with a critical eye to ensure that you are as informed as possible.

In the end, research is what makes the difference between facts and opinions. Facts are observable realities, and opinions are personal judgments, conclusions, or attitudes that may or may not be accurate. In the scientific community, facts can be established only using evidence collected through empirical research.

THE PROCESS OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH

Scientific knowledge is advanced through a process known as the scientific method . Basically, ideas (in the form of theories and hypotheses) are tested against the real world (in the form of empirical observations), and those observations lead to more ideas that are tested against the real world, and so on. In this sense, the scientific process is circular. We continually test and revise theories based on new evidence.

Two types of reasoning are used to make decisions within this model: Deductive and inductive. In deductive reasoning, ideas are tested against the empirical world. Think about a detective looking for clues and evidence to test their “hunch” about whodunit. In contrast, in inductive reasoning, empirical observations lead to new ideas. In other words, inductive reasoning involves gathering facts to create or refine a theory, rather than testing the theory by gathering facts (figure below). These processes are inseparable, like inhaling and exhaling, but different research approaches place different emphasis on the deductive and inductive aspects.

Psychological research relies on both inductive and deductive reasoning.

In the scientific context, deductive reasoning begins with a generalization—one hypothesis—that is then used to reach logical conclusions about the real world. If the hypothesis is correct, then the logical conclusions reached through deductive reasoning should also be correct. A deductive reasoning argument might go something like this: All living things require energy to survive (this would be your hypothesis). Ducks are living things. Therefore, ducks require energy to survive (logical conclusion). In this example, the hypothesis is correct; therefore, the conclusion is correct as well. Sometimes, however, an incorrect hypothesis may lead to a logical but incorrect conclusion. Consider the famous example from Greek philosophy. A philosopher decided that human beings were “featherless bipeds”. Using deductive reasoning, all two-legged creatures without feathers must be human, right? Diogenes the Cynic (named because he was, well, a cynic) burst into the room with a freshly plucked chicken from the market and held it up exclaiming “Behold! I have brought you a man!”

Deductive reasoning starts with a generalization that is tested against real-world observations; however, inductive reasoning moves in the opposite direction. Inductive reasoning uses empirical observations to construct broad generalizations. Unlike deductive reasoning, conclusions drawn from inductive reasoning may or may not be correct, regardless of the observations on which they are based. For example, you might be a biologist attempting to classify animals into groups. You notice that quite a large portion of animals are furry and produce milk for their young (cats, dogs, squirrels, horses, hippos, etc). Therefore, you might conclude that all mammals (the name you have chosen for this grouping) have hair and produce milk. This seems like a pretty great hypothesis that you could test with deductive reasoning. You go out an look at a whole bunch of things and stumble on an exception: The coconut. Coconuts have hair and produce milk, but they don’t “fit” your idea of what a mammal is. So, using inductive reasoning given the new evidence, you adjust your theory again for an other round of data collection. Inductive and deductive reasoning work in tandem to help build and improve scientific theories over time.

We’ve stated that theories and hypotheses are ideas, but what sort of ideas are they, exactly? A theory is a well-developed set of ideas that propose an explanation for observed phenomena. Theories are repeatedly checked against the world, but they tend to be too complex to be tested all at once. Instead, researchers create hypotheses to test specific aspects of a theory.

A hypothesis is a testable prediction about how the world will behave if our theory is correct, and it is often worded as an if-then statement (e.g., if I study all night, I will get a passing grade on the test). The hypothesis is extremely important because it bridges the gap between the realm of ideas and the real world. As specific hypotheses are tested, theories are modified and refined to reflect and incorporate the result of these tests (figure below).

The scientific method of research includes proposing hypotheses, conducting research, and creating or modifying theories based on results.

To see how this process works, let’s consider a specific theory and a hypothesis that might be generated from that theory. As you’ll learn in a later chapter, the James-Lange theory of emotion asserts that emotional experience relies on the physiological arousal associated with the emotional state. If you walked out of your home and discovered a very aggressive snake waiting on your doorstep, your heart would begin to race and your stomach churn. According to the James-Lange theory, these physiological changes would result in your feeling of fear. A hypothesis that could be derived from this theory might be that a person who is unaware of the physiological arousal that the sight of the snake elicits will not feel fear.

A scientific hypothesis is also falsifiable, or capable of being shown to be incorrect. Recall from the introductory chapter that Sigmund Freud had lots of interesting ideas to explain various human behaviors (figure below). However, a major criticism of Freud’s theories is that many of his ideas are not falsifiable. The essential characteristic of Freud’s building blocks of personality, the id, ego, and superego, is that they are unconscious, and therefore people can’t observe them. Because they cannot be observed or tested in any way, it is impossible to say that they don’t exist, so they cannot be considered scientific theories. Despite this, Freud’s theories are widely taught in introductory psychology texts because of their historical significance for personality psychology and psychotherapy, and these remain the root of all modern forms of therapy.

Many of the specifics of (a) Freud’s theories, such ad (b) his division on the mind into the id, ego, and superego, have fallen out of favor in recent decades because they are not falsifiable (i.e., cannot be verified through scientific investigation). In broader strokes, his views set the stage for much psychological thinking today, such as the idea that some psychological process occur at the level of the unconscious.

In contrast, the James-Lange theory does generate falsifiable hypotheses, such as the one described above. Some individuals who suffer significant injuries to their spinal columns are unable to feel the bodily changes that often accompany emotional experiences. Therefore, we could test the hypothesis by determining how emotional experiences differ between individuals who have the ability to detect these changes in their physiological arousal and those who do not. In fact, this research has been conducted and while the emotional experiences of people deprived of an awareness of their physiological arousal may be less intense, they still experience emotion (Chwalisz, Diener, & Gallagher, 1988).

Scientific research’s dependence on falsifiability allows for great confidence in the information that it produces. Typically, by the time information is accepted by the scientific community, it has been tested repeatedly.

Scientists are engaged in explaining and understanding how the world around them works, and they are able to do so by coming up with theories that generate hypotheses that are testable and falsifiable. Theories that stand up to their tests are retained and refined, while those that do not are discarded or modified. IHaving good information generated from research aids in making wise decisions both in public policy and in our personal lives.

Review Questions:

1. Scientific hypotheses are ________ and falsifiable.

a. observable

b. original

c. provable

d. testable

2. ________ are defined as observable realities.

a. behaviors

c. opinions

d. theories

3. Scientific knowledge is ________.

a. intuitive

b. empirical

c. permanent

d. subjective

4. A major criticism of Freud’s early theories involves the fact that his theories ________.

a. were too limited in scope

b. were too outrageous

c. were too broad

d. were not testable

Critical Thinking Questions:

1. In this section, the D.A.R.E. program was described as an incredibly popular program in schools across the United States despite the fact that research consistently suggests that this program is largely ineffective. How might one explain this discrepancy?

2. The scientific method is often described as self-correcting and cyclical. Briefly describe your understanding of the scientific method with regard to these concepts.

Personal Application Questions:

1. Healthcare professionals cite an enormous number of health problems related to obesity, and many people have an understandable desire to attain a healthy weight. There are many diet programs, services, and products on the market to aid those who wish to lose weight. If a close friend was considering purchasing or participating in one of these products, programs, or services, how would you make sure your friend was fully aware of the potential consequences of this decision? What sort of information would you want to review before making such an investment or lifestyle change yourself?

deductive reasoning

falsifiable

hypothesis: (plural

inductive reasoning

Answers to Exercises

Review Questions:

1. There is probably tremendous political pressure to appear to be hard on drugs. Therefore, even though D.A.R.E. might be ineffective, it is a well-known program with which voters are familiar.

2. This cyclical, self-correcting process is primarily a function of the empirical nature of science. Theories are generated as explanations of real-world phenomena. From theories, specific hypotheses are developed and tested. As a function of this testing, theories will be revisited and modified or refined to generate new hypotheses that are again tested. This cyclical process ultimately allows for more and more precise (and presumably accurate) information to be collected.

deductive reasoning: results are predicted based on a general premise

empirical: grounded in objective, tangible evidence that can be observed time and time again, regardless of who is observing

fact: objective and verifiable observation, established using evidence collected through empirical research

falsifiable: able to be disproven by experimental results

hypothesis: (plural: hypotheses) tentative and testable statement about the relationship between two or more variables

inductive reasoning: conclusions are drawn from observations

opinion: personal judgments, conclusions, or attitudes that may or may not be accurate

theory: well-developed set of ideas that propose an explanation for observed phenomena

Share This Book

- Increase Font Size

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services

- Virtual Tour

- Staff Directory

- En Español

You are here

Science, health, and public trust.

September 8, 2021

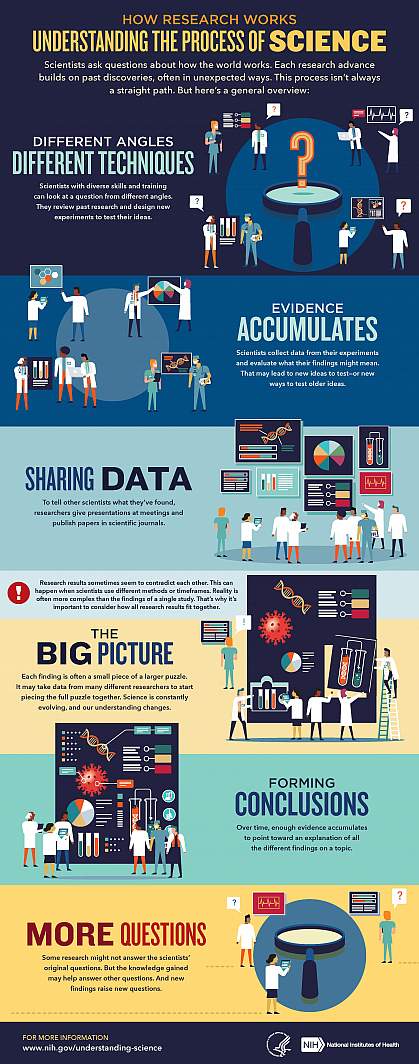

Explaining How Research Works

We’ve heard “follow the science” a lot during the pandemic. But it seems science has taken us on a long and winding road filled with twists and turns, even changing directions at times. That’s led some people to feel they can’t trust science. But when what we know changes, it often means science is working.

Explaining the scientific process may be one way that science communicators can help maintain public trust in science. Placing research in the bigger context of its field and where it fits into the scientific process can help people better understand and interpret new findings as they emerge. A single study usually uncovers only a piece of a larger puzzle.

Questions about how the world works are often investigated on many different levels. For example, scientists can look at the different atoms in a molecule, cells in a tissue, or how different tissues or systems affect each other. Researchers often must choose one or a finite number of ways to investigate a question. It can take many different studies using different approaches to start piecing the whole picture together.

Sometimes it might seem like research results contradict each other. But often, studies are just looking at different aspects of the same problem. Researchers can also investigate a question using different techniques or timeframes. That may lead them to arrive at different conclusions from the same data.

Using the data available at the time of their study, scientists develop different explanations, or models. New information may mean that a novel model needs to be developed to account for it. The models that prevail are those that can withstand the test of time and incorporate new information. Science is a constantly evolving and self-correcting process.

Scientists gain more confidence about a model through the scientific process. They replicate each other’s work. They present at conferences. And papers undergo peer review, in which experts in the field review the work before it can be published in scientific journals. This helps ensure that the study is up to current scientific standards and maintains a level of integrity. Peer reviewers may find problems with the experiments or think different experiments are needed to justify the conclusions. They might even offer new ways to interpret the data.

It’s important for science communicators to consider which stage a study is at in the scientific process when deciding whether to cover it. Some studies are posted on preprint servers for other scientists to start weighing in on and haven’t yet been fully vetted. Results that haven't yet been subjected to scientific scrutiny should be reported on with care and context to avoid confusion or frustration from readers.

We’ve developed a one-page guide, "How Research Works: Understanding the Process of Science" to help communicators put the process of science into perspective. We hope it can serve as a useful resource to help explain why science changes—and why it’s important to expect that change. Please take a look and share your thoughts with us by sending an email to [email protected].

Below are some additional resources:

- Discoveries in Basic Science: A Perfectly Imperfect Process

- When Clinical Research Is in the News

- What is Basic Science and Why is it Important?

- What is a Research Organism?

- What Are Clinical Trials and Studies?

- Basic Research – Digital Media Kit

- Decoding Science: How Does Science Know What It Knows? (NAS)

- Can Science Help People Make Decisions ? (NAS)

Connect with Us

- More Social Media from NIH

10 Reasons Why Research is Important

No matter what career field you’re in or how high up you are, there’s always more to learn . The same applies to your personal life. No matter how many experiences you have or how diverse your social circle, there are things you don’t know. Research unlocks the unknowns, lets you explore the world from different perspectives, and fuels a deeper understanding. In some areas, research is an essential part of success. In others, it may not be absolutely necessary, but it has many benefits. Here are ten reasons why research is important:

#1. Research expands your knowledge base

The most obvious reason to do research is that you’ll learn more. There’s always more to learn about a topic, even if you are already well-versed in it. If you aren’t, research allows you to build on any personal experience you have with the subject. The process of research opens up new opportunities for learning and growth.

#2. Research gives you the latest information

Research encourages you to find the most recent information available . In certain fields, especially scientific ones, there’s always new information and discoveries being made. Staying updated prevents you from falling behind and giving info that’s inaccurate or doesn’t paint the whole picture. With the latest info, you’ll be better equipped to talk about a subject and build on ideas.

#3. Research helps you know what you’re up against

In business, you’ll have competition. Researching your competitors and what they’re up to helps you formulate your plans and strategies. You can figure out what sets you apart. In other types of research, like medicine, your research might identify diseases, classify symptoms, and come up with ways to tackle them. Even if your “enemy” isn’t an actual person or competitor, there’s always some kind of antagonist force or problem that research can help you deal with.

#4. Research builds your credibility

People will take what you have to say more seriously when they can tell you’re informed. Doing research gives you a solid foundation on which you can build your ideas and opinions. You can speak with confidence about what you know is accurate. When you’ve done the research, it’s much harder for someone to poke holes in what you’re saying. Your research should be focused on the best sources. If your “research” consists of opinions from non-experts, you won’t be very credible. When your research is good, though, people are more likely to pay attention.

#5. Research helps you narrow your scope

When you’re circling a topic for the first time, you might not be exactly sure where to start. Most of the time, the amount of work ahead of you is overwhelming. Whether you’re writing a paper or formulating a business plan, it’s important to narrow the scope at some point. Research helps you identify the most unique and/or important themes. You can choose the themes that fit best with the project and its goals.

#6. Research teaches you better discernment

Doing a lot of research helps you sift through low-quality and high-quality information. The more research you do on a topic, the better you’ll get at discerning what’s accurate and what’s not. You’ll also get better at discerning the gray areas where information may be technically correct but used to draw questionable conclusions.

#7. Research introduces you to new ideas

You may already have opinions and ideas about a topic when you start researching. The more you research, the more viewpoints you’ll come across. This encourages you to entertain new ideas and perhaps take a closer look at yours. You might change your mind about something or, at least, figure out how to position your ideas as the best ones.

#8. Research helps with problem-solving

Whether it’s a personal or professional problem, it helps to look outside yourself for help. Depending on what the issue is, your research can focus on what others have done before. You might just need more information, so you can make an informed plan of attack and an informed decision. When you know you’ve collected good information, you’ll feel much more confident in your solution.

#9. Research helps you reach people

Research is used to help raise awareness of issues like climate change , racial discrimination, gender inequality , and more. Without hard facts, it’s very difficult to prove that climate change is getting worse or that gender inequality isn’t progressing as quickly as it should. The public needs to know what the facts are, so they have a clear idea of what “getting worse” or “not progressing” actually means. Research also entails going beyond the raw data and sharing real-life stories that have a more personal impact on people.

#10. Research encourages curiosity

Having curiosity and a love of learning take you far in life. Research opens you up to different opinions and new ideas. It also builds discerning and analytical skills. The research process rewards curiosity. When you’re committed to learning, you’re always in a place of growth. Curiosity is also good for your health. Studies show curiosity is associated with higher levels of positivity, better satisfaction with life, and lower anxiety.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

- Board Members

- Management Team

- Become a Contributor

- Volunteer Opportunities

- Code of Ethical Practices

KNOWLEDGE NETWORK

- Search Engines List

- Suggested Reading Library

- Web Directories

- Research Papers

- Industry News

- Become a Member

- Associate Membership

- Certified Membership

- Membership Application

- Corporate Application

- CIRS Certification Program

- CIRS Certification Objectives

- CIRS Certification Benefits

- CIRS Certification Exam

- Maintain Your Certification

- Upcoming Events

- Live Classes

- Classes Schedule

- Webinars Schedules

- Latest Articles

- Internet Research

- Search Techniques

- Research Methods

- Business Research

- Search Engines

- Research & Tools

- Investigative Research

- Internet Search

- Work from Home

- Internet Ethics

- Internet Privacy

Six Reasons Why Research is Important

Everyone conducts research in some form or another from a young age, whether news, books, or browsing the Internet. Internet users come across thoughts, ideas, or perspectives - the curiosity that drives the desire to explore. However, when research is essential to make practical decisions, the nature of the study alters - it all depends on its application and purpose. For instance, skilled research offered as a research paper service has a definite objective, and it is focused and organized. Professional research helps derive inferences and conclusions from solving problems. visit the HB tool services for the amazing research tools that will help to solve your problems regarding the research on any project.

What is the Importance of Research?

The primary goal of the research is to guide action, gather evidence for theories, and contribute to the growth of knowledge in data analysis. This article discusses the importance of research and the multiple reasons why it is beneficial to everyone, not just students and scientists.

On the other hand, research is important in business decision-making because it can assist in making better decisions when combined with their experience and intuition.

Reasons for the Importance of Research

- Acquire Knowledge Effectively

- Research helps in problem-solving

- Provides the latest information

- Builds credibility

- Helps in business success

- Discover and Seize opportunities

1- Acquire Knowledge Efficiently through Research

The most apparent reason to conduct research is to understand more. Even if you think you know everything there is to know about a subject, there is always more to learn. Research helps you expand on any prior knowledge you have of the subject. The research process creates new opportunities for learning and progress.

2- Research Helps in Problem-solving

Problem-solving can be divided into several components, which require knowledge and analysis, for example, identification of issues, cause identification, identifying potential solutions, decision to take action, monitoring and evaluation of activity and outcomes.

You may just require additional knowledge to formulate an informed strategy and make an informed decision. When you know you've gathered reliable data, you'll be a lot more confident in your answer.

3- Research Provides the Latest Information

Research enables you to seek out the most up-to-date facts. There is always new knowledge and discoveries in various sectors, particularly scientific ones. Staying updated keeps you from falling behind and providing inaccurate or incomplete information. You'll be better prepared to discuss a topic and build on ideas if you have the most up-to-date information. With the help of tools and certifications such as CIRS , you may learn internet research skills quickly and easily. Internet research can provide instant, global access to information.

4- Research Builds Credibility

Research provides a solid basis for formulating thoughts and views. You can speak confidently about something you know to be true. It's much more difficult for someone to find flaws in your arguments after you've finished your tasks. In your study, you should prioritize the most reputable sources. Your research should focus on the most reliable sources. You won't be credible if your "research" comprises non-experts' opinions. People are more inclined to pay attention if your research is excellent.

5- Research Helps in Business Success

R&D might also help you gain a competitive advantage. Finding ways to make things run more smoothly and differentiate a company's products from those of its competitors can help to increase a company's market worth.

6- Research Discover and Seize Opportunities

People can maximize their potential and achieve their goals through various opportunities provided by research. These include getting jobs, scholarships, educational subsidies, projects, commercial collaboration, and budgeted travel. Research is essential for anyone looking for work or a change of environment. Unemployed people will have a better chance of finding potential employers through job advertisements or agencies.

How to Improve Your Research Skills

Start with the big picture and work your way down.

It might be hard to figure out where to start when you start researching. There's nothing wrong with a simple internet search to get you started. Online resources like Google and Wikipedia are a great way to get a general idea of a subject, even though they aren't always correct. They usually give a basic overview with a short history and any important points.

Identify Reliable Source

Not every source is reliable, so it's critical that you can tell the difference between the good ones and the bad ones. To find a reliable source, use your analytical and critical thinking skills and ask yourself the following questions: Is this source consistent with other sources I've discovered? Is the author a subject matter expert? Is there a conflict of interest in the author's point of view on this topic?

Validate Information from Various Sources

Take in new information.

The purpose of research is to find answers to your questions, not back up what you already assume. Only looking for confirmation is a minimal way to research because it forces you to pick and choose what information you get and stops you from getting the most accurate picture of the subject. When you do research, keep an open mind to learn as much as possible.

Facilitates Learning Process

Learning new things and implementing them in daily life can be frustrating. Finding relevant and credible information requires specialized training and web search skills due to the sheer enormity of the Internet and the rapid growth of indexed web pages. On the other hand, short courses and Certifications like CIRS make the research process more accessible. CIRS Certification offers complete knowledge from beginner to expert level. You can become a Certified Professional Researcher and get a high-paying job, but you'll also be much more efficient and skilled at filtering out reliable data. You can learn more about becoming a Certified Professional Researcher.

Stay Organized

You'll see a lot of different material during the process of gathering data, from web pages to PDFs to videos. You must keep all of this information organized in some way so that you don't lose anything or forget to mention something properly. There are many ways to keep your research project organized, but here are a few of the most common: Learning Management Software , Bookmarks in your browser, index cards, and a bibliography that you can add to as you go are all excellent tools for writing.

Make Use of the library's Resources

If you still have questions about researching, don't worry—even if you're not a student performing academic or course-related research, there are many resources available to assist you. Many high school and university libraries, in reality, provide resources not only for staff and students but also for the general public. Look for research guidelines or access to specific databases on the library's website. Association of Internet Research Specialists enjoys sharing informational content such as research-related articles , research papers , specialized search engines list compiled from various sources, and contributions from our members and in-house experts.

of Conducting Research

Latest from erin r. goodrich.

- Enhancing Efficiency: The Role of Technology in Personal Injury Case Management

- The Evolution and Future of Workplace Benefit Administration

- 10 Best People Search Engines and Websites in 2022

Live Classes Schedule

- JUN 14 CIRS Certification Internet Research Training Program Live Classes Online

- JUN 14 Web Search Methods & Techniques Live Training Live Classes Online

World's leading professional association of Internet Research Specialists - We deliver Knowledge, Education, Training, and Certification in the field of Professional Online Research. The AOFIRS is considered a major contributor in improving Web Search Skills and recognizes Online Research work as a full-time occupation for those that use the Internet as their primary source of information.

Get Exclusive Research Tips in Your Inbox

- Privacy Policy

- Terms & Conditions

- Advertising Opportunities

- Knowledge Network

What Is Research and Why We Do It

- First Online: 23 June 2020

Cite this chapter

- Carlo Ghezzi 2

2995 Accesses

2 Altmetric

The notions of science and scientific research are discussed and the motivations for doing research are analyzed. Research can span a broad range of approaches, from purely theoretical to practice-oriented; different approaches often coexist and fertilize each other. Research ignites human progress and societal change. In turn, society drives and supports research. The specific role of research in Informatics is discussed. Informatics is driving the current transition towards the new digital society in which we will live in the future.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

In [ 34 ], P.E. Medawar discusses what he calls the “snobismus” of pure versus applied science. In his words, this is one of the most damaging forms of snobbism, which draws a class distinction between pure and applied science.

Originality, rigor, and significance have been defined and used as the key criteria to evaluate research outputs by the UK Research Excellence Framework (REF) [ 46 ]. A research evaluation exercise has been performed periodically since 1986 on UK higher education institutions and their research outputs have been rated according to their originality, rigor, and significance.

The importance of realizing that “we don’t know” was apparently first stated by Socrates, according to Plato’s account of his thought. This is condensed in the famous paradox “I know that I don’t know.”

This view applies mainly to natural and physical sciences.

Roy Amara was President of the Institute for Future, a USA-based think tank, from 1971 until 1990.

The Turing Award is generally recognized as the Nobel prize of Informatics.

See http://uis.unesco.org/apps/visualisations/research-and-development-spending/ .

Israel is a very good example. Investments in research resulted in a proliferation of new, cutting-edge enterprises. The term start-up nation has been coined by Dan Senor and Saul Singer in their successful book [ 51 ] to characterize this phenomenon.

https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/en/h2020-section/societal-challenges .

https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/en/h2020-section/cross-cutting-activities-focus-areas .

This figure has been adapted from a presentation by A. Fuggetta, which describes the mission of Cefriel, an Italian institution with a similar role of Fraunhofer, on a smaller scale.

The ERC takes an ecumenical approach and calls the research sector “Computer Science and Informatics.”

I discuss here the effect of “big data” on research, although most sectors of society—industry, finance, health, …—are also deeply affected.

Carayannis, E., Campbell, D.: Mode 3 knowledge production in quadruple helix innovation systems. In: E. Carayannis, D. Campbell (eds.) Mode 3 Knowledge Production in Quadruple Helix Innovation Systems: 21st-Century Democracy, Innovation, and Entrepreneurship for Development. SpringerBriefs in Business, New York, NY (2012)

Google Scholar

Etzkowitz, H., Leydesdorff, L.: The triple helix – university-industry-government relations: A laboratory for knowledge based economic development. EASST Review 14 (1), 14–19 (1995)

Harari, Y.: Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind. Random House (2014). URL https://books.google.it/books?id=1EiJAwAAQBAJ

Harari, Y.: Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow. Random House (2016). URL https://books.google.it/books?id=dWYyCwAAQBAJ

Hopcroft, J.E., Motwani, R., Ullman, J.D.: Introduction to Automata Theory, Languages, and Computation (3rd Edition). Addison-Wesley Longman Publishing Co., Inc., USA (2006)

MATH Google Scholar

Medawar, P.: Advice To A Young Scientist. Alfred P. Sloan Foundation series. Basic Books (2008)

OECD: Frascati Manual. OECD Publishing (2015). https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264239012-en . URL https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/9789264239012-en

REF2019/2: Panel criteria and working methods (2019). URL https://www.ref.ac.uk/media/1084/ref-2019_02-panel-criteria-and-working-methods.pdf

Senor, D., Singer, S.: Start-Up Nation: The Story of Israel’s Economic Miracle. McClelland & Stewart, Toronto, Canada (2011)

Stokes, D.E.: Pasteur’s Quadrant: Basic Science and Technological Innovation. Brookings Institution Press, Washington, D.C. (1997)

Thurston, R.H.: The growth of the steam engine. Popular Science Monthly 12 (1877)

Vardi, M.Y.: The long game of research. Commun. ACM 62 (9), 7–7 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1145/3352489 . URL http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/3352489

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Dipartimento di Elettronica, Informazione e Bioingegneria, Politecnico di Milano, Milano, Italy

Carlo Ghezzi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Carlo Ghezzi .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Ghezzi, C. (2020). What Is Research and Why We Do It. In: Being a Researcher. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45157-8_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-45157-8_1

Published : 23 June 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-45156-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-45157-8

eBook Packages : Computer Science Computer Science (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

2.1 Why Is Research Important?

Learning objectives.

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Explain how scientific research addresses questions about behavior

- Discuss how scientific research guides public policy

- Appreciate how scientific research can be important in making personal decisions

Scientific research is a critical tool for successfully navigating our complex world. Without it, we would be forced to rely solely on intuition, other people’s authority, and blind luck. While many of us feel confident in our abilities to decipher and interact with the world around us, history is filled with examples of how very wrong we can be when we fail to recognize the need for evidence in supporting claims. At various times in history, we would have been certain that the sun revolved around a flat earth, that the earth’s continents did not move, and that mental illness was caused by possession ( Figure 2.2 ). It is through systematic scientific research that we divest ourselves of our preconceived notions and superstitions and gain an objective understanding of ourselves and our world.

The goal of all scientists is to better understand the world around them. Psychologists focus their attention on understanding behavior, as well as the cognitive (mental) and physiological (body) processes that underlie behavior. In contrast to other methods that people use to understand the behavior of others, such as intuition and personal experience, the hallmark of scientific research is that there is evidence to support a claim. Scientific knowledge is empirical : It is grounded in objective, tangible evidence that can be observed time and time again, regardless of who is observing.

While behavior is observable, the mind is not. If someone is crying, we can see behavior. However, the reason for the behavior is more difficult to determine. Is the person crying due to being sad, in pain, or happy? Sometimes we can learn the reason for someone’s behavior by simply asking a question, like “Why are you crying?” However, there are situations in which an individual is either uncomfortable or unwilling to answer the question honestly, or is incapable of answering. For example, infants would not be able to explain why they are crying. In such circumstances, the psychologist must be creative in finding ways to better understand behavior. This chapter explores how scientific knowledge is generated, and how important that knowledge is in forming decisions in our personal lives and in the public domain.

Use of Research Information

Trying to determine which theories are and are not accepted by the scientific community can be difficult, especially in an area of research as broad as psychology. More than ever before, we have an incredible amount of information at our fingertips, and a simple internet search on any given research topic might result in a number of contradictory studies. In these cases, we are witnessing the scientific community going through the process of reaching a consensus, and it could be quite some time before a consensus emerges. For example, the explosion in our use of technology has led researchers to question whether this ultimately helps or hinders us. The use and implementation of technology in educational settings has become widespread over the last few decades. Researchers are coming to different conclusions regarding the use of technology. To illustrate this point, a study investigating a smartphone app targeting surgery residents (graduate students in surgery training) found that the use of this app can increase student engagement and raise test scores (Shaw & Tan, 2015). Conversely, another study found that the use of technology in undergraduate student populations had negative impacts on sleep, communication, and time management skills (Massimini & Peterson, 2009). Until sufficient amounts of research have been conducted, there will be no clear consensus on the effects that technology has on a student's acquisition of knowledge, study skills, and mental health.

In the meantime, we should strive to think critically about the information we encounter by exercising a degree of healthy skepticism. When someone makes a claim, we should examine the claim from a number of different perspectives: what is the expertise of the person making the claim, what might they gain if the claim is valid, does the claim seem justified given the evidence, and what do other researchers think of the claim? This is especially important when we consider how much information in advertising campaigns and on the internet claims to be based on “scientific evidence” when in actuality it is a belief or perspective of just a few individuals trying to sell a product or draw attention to their perspectives.

We should be informed consumers of the information made available to us because decisions based on this information have significant consequences. One such consequence can be seen in politics and public policy. Imagine that you have been elected as the governor of your state. One of your responsibilities is to manage the state budget and determine how to best spend your constituents’ tax dollars. As the new governor, you need to decide whether to continue funding early intervention programs. These programs are designed to help children who come from low-income backgrounds, have special needs, or face other disadvantages. These programs may involve providing a wide variety of services to maximize the children's development and position them for optimal levels of success in school and later in life (Blann, 2005). While such programs sound appealing, you would want to be sure that they also proved effective before investing additional money in these programs. Fortunately, psychologists and other scientists have conducted vast amounts of research on such programs and, in general, the programs are found to be effective (Neil & Christensen, 2009; Peters-Scheffer, Didden, Korzilius, & Sturmey, 2011). While not all programs are equally effective, and the short-term effects of many such programs are more pronounced, there is reason to believe that many of these programs produce long-term benefits for participants (Barnett, 2011). If you are committed to being a good steward of taxpayer money, you would want to look at research. Which programs are most effective? What characteristics of these programs make them effective? Which programs promote the best outcomes? After examining the research, you would be best equipped to make decisions about which programs to fund.

Link to Learning

Watch this video about early childhood program effectiveness to learn how scientists evaluate effectiveness and how best to invest money into programs that are most effective.

Ultimately, it is not just politicians who can benefit from using research in guiding their decisions. We all might look to research from time to time when making decisions in our lives. Imagine that your sister, Maria, expresses concern about her two-year-old child, Umberto. Umberto does not speak as much or as clearly as the other children in his daycare or others in the family. Umberto's pediatrician undertakes some screening and recommends an evaluation by a speech pathologist, but does not refer Maria to any other specialists. Maria is concerned that Umberto's speech delays are signs of a developmental disorder, but Umberto's pediatrician does not; she sees indications of differences in Umberto's jaw and facial muscles. Hearing this, you do some internet searches, but you are overwhelmed by the breadth of information and the wide array of sources. You see blog posts, top-ten lists, advertisements from healthcare providers, and recommendations from several advocacy organizations. Why are there so many sites? Which are based in research, and which are not?

In the end, research is what makes the difference between facts and opinions. Facts are observable realities, and opinions are personal judgments, conclusions, or attitudes that may or may not be accurate. In the scientific community, facts can be established only using evidence collected through empirical research.

NOTABLE RESEARCHERS

Psychological research has a long history involving important figures from diverse backgrounds. While the introductory chapter discussed several researchers who made significant contributions to the discipline, there are many more individuals who deserve attention in considering how psychology has advanced as a science through their work ( Figure 2.3 ). For instance, Margaret Floy Washburn (1871–1939) was the first woman to earn a PhD in psychology. Her research focused on animal behavior and cognition (Margaret Floy Washburn, PhD, n.d.). Mary Whiton Calkins (1863–1930) was a preeminent first-generation American psychologist who opposed the behaviorist movement, conducted significant research into memory, and established one of the earliest experimental psychology labs in the United States (Mary Whiton Calkins, n.d.).

Francis Sumner (1895–1954) was the first African American to receive a PhD in psychology in 1920. His dissertation focused on issues related to psychoanalysis. Sumner also had research interests in racial bias and educational justice. Sumner was one of the founders of Howard University’s department of psychology, and because of his accomplishments, he is sometimes referred to as the “Father of Black Psychology.” Thirteen years later, Inez Beverly Prosser (1895–1934) became the first African American woman to receive a PhD in psychology. Prosser’s research highlighted issues related to education in segregated versus integrated schools, and ultimately, her work was very influential in the hallmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional (Ethnicity and Health in America Series: Featured Psychologists, n.d.).

Although the establishment of psychology’s scientific roots occurred first in Europe and the United States, it did not take much time until researchers from around the world began to establish their own laboratories and research programs. For example, some of the first experimental psychology laboratories in South America were founded by Horatio Piñero (1869–1919) at two institutions in Buenos Aires, Argentina (Godoy & Brussino, 2010). In India, Gunamudian David Boaz (1908–1965) and Narendra Nath Sen Gupta (1889–1944) established the first independent departments of psychology at the University of Madras and the University of Calcutta, respectively. These developments provided an opportunity for Indian researchers to make important contributions to the field (Gunamudian David Boaz, n.d.; Narendra Nath Sen Gupta, n.d.).

When the American Psychological Association (APA) was first founded in 1892, all of the members were White males (Women and Minorities in Psychology, n.d.). However, by 1905, Mary Whiton Calkins was elected as the first female president of the APA, and by 1946, nearly one-quarter of American psychologists were female. Psychology became a popular degree option for students enrolled in the nation’s historically Black higher education institutions, increasing the number of Black Americans who went on to become psychologists. Given demographic shifts occurring in the United States and increased access to higher educational opportunities among historically underrepresented populations, there is reason to hope that the diversity of the field will increasingly match the larger population, and that the research contributions made by the psychologists of the future will better serve people of all backgrounds (Women and Minorities in Psychology, n.d.).

The Process of Scientific Research

Scientific knowledge is advanced through a process known as the scientific method . Basically, ideas (in the form of theories and hypotheses) are tested against the real world (in the form of empirical observations), and those empirical observations lead to more ideas that are tested against the real world, and so on. In this sense, the scientific process is circular. The types of reasoning within the circle are called deductive and inductive. In deductive reasoning , ideas are tested in the real world; in inductive reasoning , real-world observations lead to new ideas ( Figure 2.4 ). These processes are inseparable, like inhaling and exhaling, but different research approaches place different emphasis on the deductive and inductive aspects.

In the scientific context, deductive reasoning begins with a generalization—one hypothesis—that is then used to reach logical conclusions about the real world. If the hypothesis is correct, then the logical conclusions reached through deductive reasoning should also be correct. A deductive reasoning argument might go something like this: All living things require energy to survive (this would be your hypothesis). Ducks are living things. Therefore, ducks require energy to survive (logical conclusion). In this example, the hypothesis is correct; therefore, the conclusion is correct as well. Sometimes, however, an incorrect hypothesis may lead to a logical but incorrect conclusion. Consider this argument: all ducks are born with the ability to see. Quackers is a duck. Therefore, Quackers was born with the ability to see. Scientists use deductive reasoning to empirically test their hypotheses. Returning to the example of the ducks, researchers might design a study to test the hypothesis that if all living things require energy to survive, then ducks will be found to require energy to survive.

Deductive reasoning starts with a generalization that is tested against real-world observations; however, inductive reasoning moves in the opposite direction. Inductive reasoning uses empirical observations to construct broad generalizations. Unlike deductive reasoning, conclusions drawn from inductive reasoning may or may not be correct, regardless of the observations on which they are based. For instance, you may notice that your favorite fruits—apples, bananas, and oranges—all grow on trees; therefore, you assume that all fruit must grow on trees. This would be an example of inductive reasoning, and, clearly, the existence of strawberries, blueberries, and kiwi demonstrate that this generalization is not correct despite it being based on a number of direct observations. Scientists use inductive reasoning to formulate theories, which in turn generate hypotheses that are tested with deductive reasoning. In the end, science involves both deductive and inductive processes.

For example, case studies, which you will read about in the next section, are heavily weighted on the side of empirical observations. Thus, case studies are closely associated with inductive processes as researchers gather massive amounts of observations and seek interesting patterns (new ideas) in the data. Experimental research, on the other hand, puts great emphasis on deductive reasoning.

We’ve stated that theories and hypotheses are ideas, but what sort of ideas are they, exactly? A theory is a well-developed set of ideas that propose an explanation for observed phenomena. Theories are repeatedly checked against the world, but they tend to be too complex to be tested all at once; instead, researchers create hypotheses to test specific aspects of a theory.

A hypothesis is a testable prediction about how the world will behave if our idea is correct, and it is often worded as an if-then statement (e.g., if I study all night, I will get a passing grade on the test). The hypothesis is extremely important because it bridges the gap between the realm of ideas and the real world. As specific hypotheses are tested, theories are modified and refined to reflect and incorporate the result of these tests Figure 2.5 .

To see how this process works, let’s consider a specific theory and a hypothesis that might be generated from that theory. As you’ll learn in a later chapter, the James-Lange theory of emotion asserts that emotional experience relies on the physiological arousal associated with the emotional state. If you walked out of your home and discovered a very aggressive snake waiting on your doorstep, your heart would begin to race and your stomach churn. According to the James-Lange theory, these physiological changes would result in your feeling of fear. A hypothesis that could be derived from this theory might be that a person who is unaware of the physiological arousal that the sight of the snake elicits will not feel fear.

A scientific hypothesis is also falsifiable , or capable of being shown to be incorrect. Recall from the introductory chapter that Sigmund Freud had lots of interesting ideas to explain various human behaviors ( Figure 2.6 ). However, a major criticism of Freud’s theories is that many of his ideas are not falsifiable; for example, it is impossible to imagine empirical observations that would disprove the existence of the id, the ego, and the superego—the three elements of personality described in Freud’s theories. Despite this, Freud’s theories are widely taught in introductory psychology texts because of their historical significance for personality psychology and psychotherapy, and these remain the root of all modern forms of therapy.

In contrast, the James-Lange theory does generate falsifiable hypotheses, such as the one described above. Some individuals who suffer significant injuries to their spinal columns are unable to feel the bodily changes that often accompany emotional experiences. Therefore, we could test the hypothesis by determining how emotional experiences differ between individuals who have the ability to detect these changes in their physiological arousal and those who do not. In fact, this research has been conducted and while the emotional experiences of people deprived of an awareness of their physiological arousal may be less intense, they still experience emotion (Chwalisz, Diener, & Gallagher, 1988).

Scientific research’s dependence on falsifiability allows for great confidence in the information that it produces. Typically, by the time information is accepted by the scientific community, it has been tested repeatedly.

As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

This book may not be used in the training of large language models or otherwise be ingested into large language models or generative AI offerings without OpenStax's permission.

Want to cite, share, or modify this book? This book uses the Creative Commons Attribution License and you must attribute OpenStax.

Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Authors: Rose M. Spielman, William J. Jenkins, Marilyn D. Lovett

- Publisher/website: OpenStax

- Book title: Psychology 2e

- Publication date: Apr 22, 2020

- Location: Houston, Texas

- Book URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/1-introduction

- Section URL: https://openstax.org/books/psychology-2e/pages/2-1-why-is-research-important

© Jan 6, 2024 OpenStax. Textbook content produced by OpenStax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License . The OpenStax name, OpenStax logo, OpenStax book covers, OpenStax CNX name, and OpenStax CNX logo are not subject to the Creative Commons license and may not be reproduced without the prior and express written consent of Rice University.

What Is the Importance of Research? 5 Reasons Why Research is Critical

by Logan Bessant | Nov 16, 2021 | Science

Most of us appreciate that research is a crucial part of medical advancement. But what exactly is the importance of research? In short, it is critical in the development of new medicines as well as ensuring that existing treatments are used to their full potential.

Research can bridge knowledge gaps and change the way healthcare practitioners work by providing solutions to previously unknown questions.

In this post, we’ll discuss the importance of research and its impact on medical breakthroughs.

The Importance Of Health Research

The purpose of studying is to gather information and evidence, inform actions, and contribute to the overall knowledge of a certain field. None of this is possible without research.

Understanding how to conduct research and the importance of it may seem like a very simple idea to some, but in reality, it’s more than conducting a quick browser search and reading a few chapters in a textbook.

No matter what career field you are in, there is always more to learn. Even for people who hold a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in their field of study, there is always some sort of unknown that can be researched. Delving into this unlocks the unknowns, letting you explore the world from different perspectives and fueling a deeper understanding of how the universe works.

To make things a little more specific, this concept can be clearly applied in any healthcare scenario. Health research has an incredibly high value to society as it provides important information about disease trends and risk factors, outcomes of treatments, patterns of care, and health care costs and use. All of these factors as well as many more are usually researched through a clinical trial.

What Is The Importance Of Clinical Research?

Clinical trials are a type of research that provides information about a new test or treatment. They are usually carried out to find out what, or if, there are any effects of these procedures or drugs on the human body.

All legitimate clinical trials are carefully designed, reviewed and completed, and need to be approved by professionals before they can begin. They also play a vital part in the advancement of medical research including:

- Providing new and good information on which types of drugs are more effective.

- Bringing new treatments such as medicines, vaccines and devices into the field.

- Testing the safety and efficacy of a new drug before it is brought to market and used in clinical practice.

- Giving the opportunity for more effective treatments to benefit millions of lives both now and in the future.

- Enhancing health, lengthening life, and reducing the burdens of illness and disability.

This all plays back to clinical research as it opens doors to advancing prevention, as well as providing treatments and cures for diseases and disabilities. Clinical trial volunteer participants are essential to this progress which further supports the need for the importance of research to be well-known amongst healthcare professionals, students and the general public.

Five Reasons Why Research is Critical

Research is vital for almost everyone irrespective of their career field. From doctors to lawyers to students to scientists, research is the key to better work.

- Increases quality of life

Research is the backbone of any major scientific or medical breakthrough. None of the advanced treatments or life-saving discoveries used to treat patients today would be available if it wasn’t for the detailed and intricate work carried out by scientists, doctors and healthcare professionals over the past decade.

This improves quality of life because it can help us find out important facts connected to the researched subject. For example, universities across the globe are now studying a wide variety of things from how technology can help breed healthier livestock, to how dance can provide long-term benefits to people living with Parkinson’s.

For both of these studies, quality of life is improved. Farmers can use technology to breed healthier livestock which in turn provides them with a better turnover, and people who suffer from Parkinson’s disease can find a way to reduce their symptoms and ease their stress.

Research is a catalyst for solving the world’s most pressing issues. Even though the complexity of these issues evolves over time, they always provide a glimmer of hope to improving lives and making processes simpler.

- Builds up credibility

People are willing to listen and trust someone with new information on one condition – it’s backed up. And that’s exactly where research comes in. Conducting studies on new and unfamiliar subjects, and achieving the desired or expected outcome, can help people accept the unknown.

However, this goes without saying that your research should be focused on the best sources. It is easy for people to poke holes in your findings if your studies have not been carried out correctly, or there is no reliable data to back them up.

This way once you have done completed your research, you can speak with confidence about your findings within your field of study.

- Drives progress forward

It is with thanks to scientific research that many diseases once thought incurable, now have treatments. For example, before the 1930s, anyone who contracted a bacterial infection had a high probability of death. There simply was no treatment for even the mildest of infections as, at the time, it was thought that nothing could kill bacteria in the gut.

When antibiotics were discovered and researched in 1928, it was considered one of the biggest breakthroughs in the medical field. This goes to show how much research drives progress forward, and how it is also responsible for the evolution of technology .

Today vaccines, diagnoses and treatments can all be simplified with the progression of medical research, making us question just what research can achieve in the future.

- Engages curiosity

The acts of searching for information and thinking critically serve as food for the brain, allowing our inherent creativity and logic to remain active. Aside from the fact that this curiosity plays such a huge part within research, it is also proven that exercising our minds can reduce anxiety and our chances of developing mental illnesses in the future.

Without our natural thirst and our constant need to ask ‘why?’ and ‘how?’ many important theories would not have been put forward and life-changing discoveries would not have been made. The best part is that the research process itself rewards this curiosity.

Research opens you up to different opinions and new ideas which can take a proposed question and turn into a real-life concept. It also builds discerning and analytical skills which are always beneficial in many career fields – not just scientific ones.

- Increases awareness

The main goal of any research study is to increase awareness, whether it’s contemplating new concepts with peers from work or attracting the attention of the general public surrounding a certain issue.

Around the globe, research is used to help raise awareness of issues like climate change, racial discrimination, and gender inequality. Without consistent and reliable studies to back up these issues, it would be hard to convenience people that there is a problem that needs to be solved in the first place.

The problem is that social media has become a place where fake news spreads like a wildfire, and with so many incorrect facts out there it can be hard to know who to trust. Assessing the integrity of the news source and checking for similar news on legitimate media outlets can help prove right from wrong.

This can pinpoint fake research articles and raises awareness of just how important fact-checking can be.

The Importance Of Research To Students

It is not a hidden fact that research can be mentally draining, which is why most students avoid it like the plague. But the matter of fact is that no matter which career path you choose to go down, research will inevitably be a part of it.

But why is research so important to students ? The truth is without research, any intellectual growth is pretty much impossible. It acts as a knowledge-building tool that can guide you up to the different levels of learning. Even if you are an expert in your field, there is always more to uncover, or if you are studying an entirely new topic, research can help you build a unique perspective about it.

For example, if you are looking into a topic for the first time, it might be confusing knowing where to begin. Most of the time you have an overwhelming amount of information to sort through whether that be reading through scientific journals online or getting through a pile of textbooks. Research helps to narrow down to the most important points you need so you are able to find what you need to succeed quickly and easily.

It can also open up great doors in the working world. Employers, especially those in the scientific and medical fields, are always looking for skilled people to hire. Undertaking research and completing studies within your academic phase can show just how multi-skilled you are and give you the resources to tackle any tasks given to you in the workplace.

The Importance Of Research Methodology

There are many different types of research that can be done, each one with its unique methodology and features that have been designed to use in specific settings.

When showing your research to others, they will want to be guaranteed that your proposed inquiry needs asking, and that your methodology is equipt to answer your inquiry and will convey the results you’re looking for.

That’s why it’s so important to choose the right methodology for your study. Knowing what the different types of research are and what each of them focuses on can allow you to plan your project to better utilise the most appropriate methodologies and techniques available. Here are some of the most common types:

- Theoretical Research: This attempts to answer a question based on the unknown. This could include studying phenomena or ideas whose conclusions may not have any immediate real-world application. Commonly used in physics and astronomy applications.

- Applied Research: Mainly for development purposes, this seeks to solve a practical problem that draws on theory to generate practical scientific knowledge. Commonly used in STEM and medical fields.

- Exploratory Research: Used to investigate a problem that is not clearly defined, this type of research can be used to establish cause-and-effect relationships. It can be applied in a wide range of fields from business to literature.

- Correlational Research: This identifies the relationship between two or more variables to see if and how they interact with each other. Very commonly used in psychological and statistical applications.

The Importance Of Qualitative Research

This type of research is most commonly used in scientific and social applications. It collects, compares and interprets information to specifically address the “how” and “why” research questions.

Qualitative research allows you to ask questions that cannot be easily put into numbers to understand human experience because you’re not limited by survey instruments with a fixed set of possible responses.

Information can be gathered in numerous ways including interviews, focus groups and ethnographic research which is then all reported in the language of the informant instead of statistical analyses.

This type of research is important because they do not usually require a hypothesis to be carried out. Instead, it is an open-ended research approach that can be adapted and changed while the study is ongoing. This enhances the quality of the data and insights generated and creates a much more unique set of data to analyse.

The Process Of Scientific Research

No matter the type of research completed, it will be shared and read by others. Whether this is with colleagues at work, peers at university, or whilst it’s being reviewed and repeated during secondary analysis.

A reliable procedure is necessary in order to obtain the best information which is why it’s important to have a plan. Here are the six basic steps that apply in any research process.

- Observation and asking questions: Seeing a phenomenon and asking yourself ‘How, What, When, Who, Which, Why, or Where?’. It is best that these questions are measurable and answerable through experimentation.

- Gathering information: Doing some background research to learn what is already known about the topic, and what you need to find out.

- Forming a hypothesis: Constructing a tentative statement to study.

- Testing the hypothesis: Conducting an experiment to test the accuracy of your statement. This is a way to gather data about your predictions and should be easy to repeat.

- Making conclusions: Analysing the data from the experiment(s) and drawing conclusions about whether they support or contradict your hypothesis.

- Reporting: Presenting your findings in a clear way to communicate with others. This could include making a video, writing a report or giving a presentation to illustrate your findings.

Although most scientists and researchers use this method, it may be tweaked between one study and another. Skipping or repeating steps is common within, however the core principles of the research process still apply.

By clearly explaining the steps and procedures used throughout the study, other researchers can then replicate the results. This is especially beneficial for peer reviews that try to replicate the results to ensure that the study is sound.

What Is The Importance Of Research In Everyday Life?

Conducting a research study and comparing it to how important it is in everyday life are two very different things.

Carrying out research allows you to gain a deeper understanding of science and medicine by developing research questions and letting your curiosity blossom. You can experience what it is like to work in a lab and learn about the whole reasoning behind the scientific process. But how does that impact everyday life?

Simply put, it allows us to disprove lies and support truths. This can help society to develop a confident attitude and not believe everything as easily, especially with the rise of fake news.

Research is the best and reliable way to understand and act on the complexities of various issues that we as humans are facing. From technology to healthcare to defence to climate change, carrying out studies is the only safe and reliable way to face our future.

Not only does research sharpen our brains, but also helps us to understand various issues of life in a much larger manner, always leaving us questioning everything and fuelling our need for answers.

Related Articles:

- What is STEM education?

- How Stem Education Improves Student Learning

- What Are the Three Domains for the Roles of Technology for Teaching and Learning?

- Why Is FIDO2 Secure?

Featured Articles

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.1 The Purpose of Research Writing

Learning objectives.

- Identify reasons to research writing projects.

- Outline the steps of the research writing process.

Why was the Great Wall of China built? What have scientists learned about the possibility of life on Mars? What roles did women play in the American Revolution? How does the human brain create, store, and retrieve memories? Who invented the game of football, and how has it changed over the years?

You may know the answers to these questions off the top of your head. If you are like most people, however, you find answers to tough questions like these by searching the Internet, visiting the library, or asking others for information. To put it simply, you perform research.