Poverty Essay for Students and Children

500+ words essay on poverty essay.

“Poverty is the worst form of violence”. – Mahatma Gandhi.

How Poverty is Measured?

For measuring poverty United nations have devised two measures of poverty – Absolute & relative poverty. Absolute poverty is used to measure poverty in developing countries like India. Relative poverty is used to measure poverty in developed countries like the USA. In absolute poverty, a line based on the minimum level of income has been created & is called a poverty line. If per day income of a family is below this level, then it is poor or below the poverty line. If per day income of a family is above this level, then it is non-poor or above the poverty line. In India, the new poverty line is Rs 32 in rural areas and Rs 47 in urban areas.

Get the huge list of more than 500 Essay Topics and Ideas

Causes of Poverty

According to the Noble prize winner South African leader, Nelson Mandela – “Poverty is not natural, it is manmade”. The above statement is true as the causes of poverty are generally man-made. There are various causes of poverty but the most important is population. Rising population is putting the burden on the resources & budget of countries. Governments are finding difficult to provide food, shelter & employment to the rising population.

The other causes are- lack of education, war, natural disaster, lack of employment, lack of infrastructure, political instability, etc. For instance- lack of employment opportunities makes a person jobless & he is not able to earn enough to fulfill the basic necessities of his family & becomes poor. Lack of education compels a person for less paying jobs & it makes him poorer. Lack of infrastructure means there are no industries, banks, etc. in a country resulting in lack of employment opportunities. Natural disasters like flood, earthquake also contribute to poverty.

In some countries, especially African countries like Somalia, a long period of civil war has made poverty widespread. This is because all the resources & money is being spent in war instead of public welfare. Countries like India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, etc. are prone to natural disasters like cyclone, etc. These disasters occur every year causing poverty to rise.

Ill Effects of Poverty

Poverty affects the life of a poor family. A poor person is not able to take proper food & nutrition &his capacity to work reduces. Reduced capacity to work further reduces his income, making him poorer. Children from poor family never get proper schooling & proper nutrition. They have to work to support their family & this destroys their childhood. Some of them may also involve in crimes like theft, murder, robbery, etc. A poor person remains uneducated & is forced to live under unhygienic conditions in slums. There are no proper sanitation & drinking water facility in slums & he falls ill often & his health deteriorates. A poor person generally dies an early death. So, all social evils are related to poverty.

Government Schemes to Remove Poverty

The government of India also took several measures to eradicate poverty from India. Some of them are – creating employment opportunities , controlling population, etc. In India, about 60% of the population is still dependent on agriculture for its livelihood. Government has taken certain measures to promote agriculture in India. The government constructed certain dams & canals in our country to provide easy availability of water for irrigation. Government has also taken steps for the cheap availability of seeds & farming equipment to promote agriculture. Government is also promoting farming of cash crops like cotton, instead of food crops. In cities, the government is promoting industrialization to create more jobs. Government has also opened ‘Ration shops’. Other measures include providing free & compulsory education for children up to 14 years of age, scholarship to deserving students from a poor background, providing subsidized houses to poor people, etc.

Poverty is a social evil, we can also contribute to control it. For example- we can simply donate old clothes to poor people, we can also sponsor the education of a poor child or we can utilize our free time by teaching poor students. Remember before wasting food, somebody is still sleeping hungry.

Customize your course in 30 seconds

Which class are you in.

- Travelling Essay

- Picnic Essay

- Our Country Essay

- My Parents Essay

- Essay on Favourite Personality

- Essay on Memorable Day of My Life

- Essay on Knowledge is Power

- Essay on Gurpurab

- Essay on My Favourite Season

- Essay on Types of Sports

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Download the App

Jump to main content

Jump to navigation

- Latest News Read the latest blog posts from 1600 Pennsylvania Ave

- Share-Worthy Check out the most popular infographics and videos

- Photos View the photo of the day and other galleries

- Video Gallery Watch behind-the-scenes videos and more

- Live Events Tune in to White House events and statements as they happen

- Music & Arts Performances See the lineup of artists and performers at the White House

- Your Weekly Address

- Speeches & Remarks

- Press Briefings

- Statements & Releases

- White House Schedule

- Presidential Actions

- Legislation

- Nominations & Appointments

- Disclosures

- Cabinet Exit Memos

- Criminal Justice Reform

- Civil Rights

- Climate Change

- Foreign Policy

- Health Care

- Immigration Action

- Disabilities

- Homeland Security

- Reducing Gun Violence

- Seniors & Social Security

- Urban and Economic Mobility

- President Barack Obama

- Vice President Joe Biden

- First Lady Michelle Obama

- Dr. Jill Biden

- The Cabinet

- Executive Office of the President

- Senior White House Leadership

- Other Advisory Boards

- Office of Management and Budget

- Office of Science and Technology Policy

- Council of Economic Advisers

- Council on Environmental Quality

- National Security Council

- Joining Forces

- Reach Higher

- My Brother's Keeper

- Precision Medicine

- State of the Union

- Inauguration

- Medal of Freedom

- Follow Us on Social Media

- We the Geeks Hangouts

- Mobile Apps

- Developer Tools

- Tools You Can Use

- Tours & Events

- Jobs with the Administration

- Internships

- White House Fellows

- Presidential Innovation Fellows

- United States Digital Service

- Leadership Development Program

- We the People Petitions

- Contact the White House

- Citizens Medal

- Champions of Change

- West Wing Tour

- Eisenhower Executive Office Building Tour

- Video Series

- Décor and Art

- First Ladies

- The Vice President's Residence & Office

- Eisenhower Executive Office Building

- Air Force One

- The Executive Branch

- The Legislative Branch

- The Judicial Branch

- The Constitution

- Federal Agencies & Commissions

- Elections & Voting

- State & Local Government

Search form

Six examples of the long-term benefits of anti-poverty programs.

Economists have traditionally argued that anti-poverty policy faces a “great tradeoff”—famously articulated by Arthur Okun—between equity and efficiency. Yet, recent work suggests that Okun’s famous tradeoff may be far smaller in practice than traditionally believed and in many cases precisely the opposite could be the case. As discussed by one of us in today’s New York Times, recent economic research, much of it using large, high-quality administrative data, shows that key income support, education, housing, health care, and nutritional assistance programs improve health outcomes, educational attainment, employment, and earnings in adulthood for individuals who received this support in childhood. This research suggests that the investments in nutrition assistance, health care, housing vouchers and other programs included in the President’s Budget would not only help low-income families today, but would also improve our future economic performance.

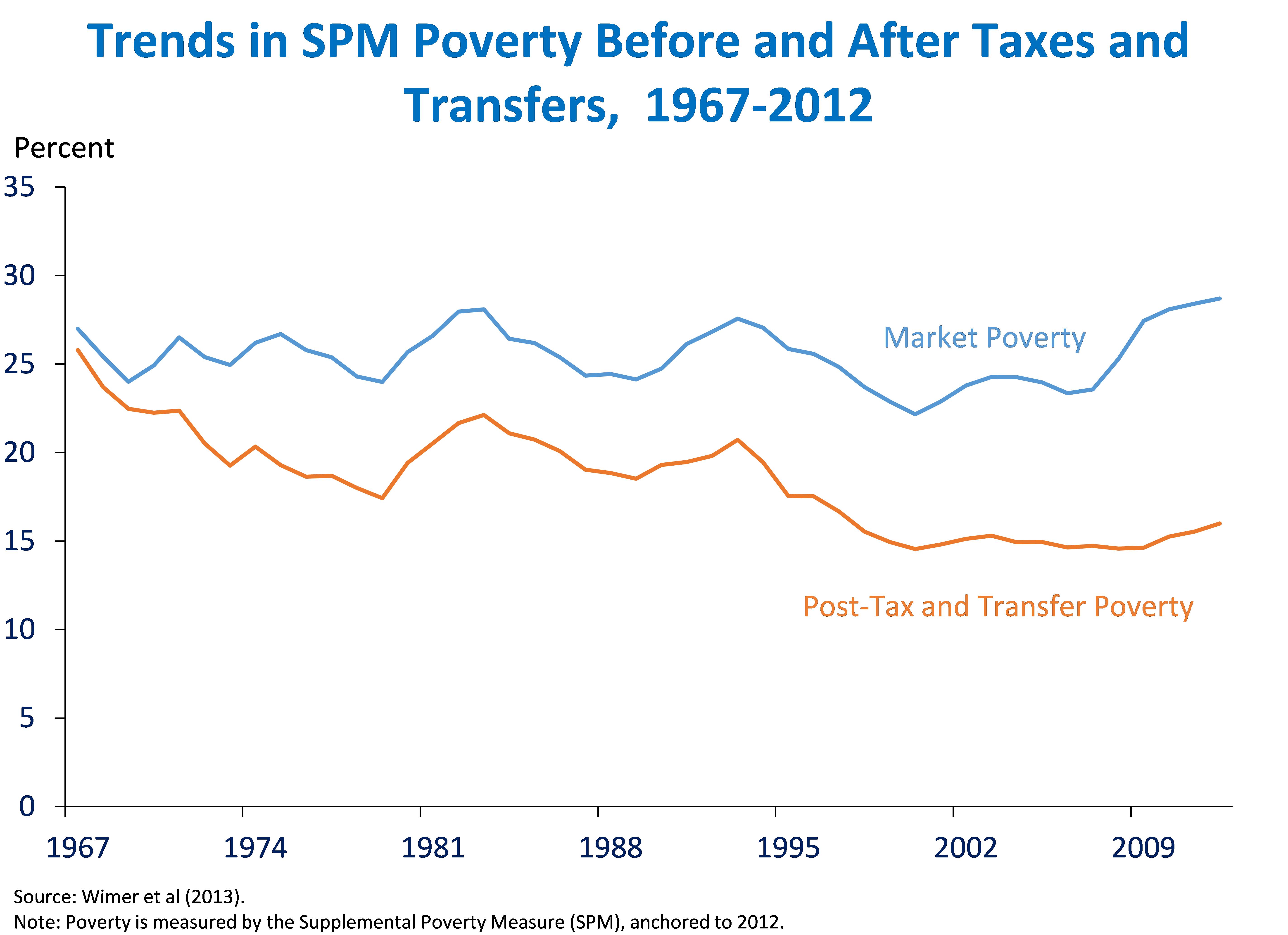

In the half century since President Lyndon B. Johnson declared an unconditional War on Poverty, the Federal Government has invested in strategies that aim to relieve and prevent poverty. Partly as a result of these programs, and a large number of additions and reforms since then, between 1967 and 2012, poverty measured by a measure that accounts for tax and transfer payments fell 9.8 percentage points, or 38 percent. In 2013, income and nutrition assistance programs lifted 46 million people, including 10 million children, out of the poverty. Medicaid has also resulted in better health care for tens of millions of Americans. Another 16 million people have gained coverage following the Affordable Care Act’s coverage expansions, as of early 2015.

Innovative economic research is increasingly finding that these programs have long-run benefits for the children in families that receive them. These studies often drawn upon large “administrative” data sets that are collected in the process of running government programs. These data sources frequently allow researchers to track families over long periods of time with limited attrition, offer much larger sample sizes, and suffer from less missing data than major household surveys. These improvements in data quality have coincided with a “ credibility revolution ” in economics that has greatly expanded the use of randomized trials and “quasi-experimental” research designs that exploit natural experiments to estimate the causal impact of the programs.

The following is a selection of research in this area for five major current programs—early education, the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance (SNAP), housing vouchers, and Medicaid—plus one historical income support program.

1. Early childhood education programs increase earnings and educational attainment.

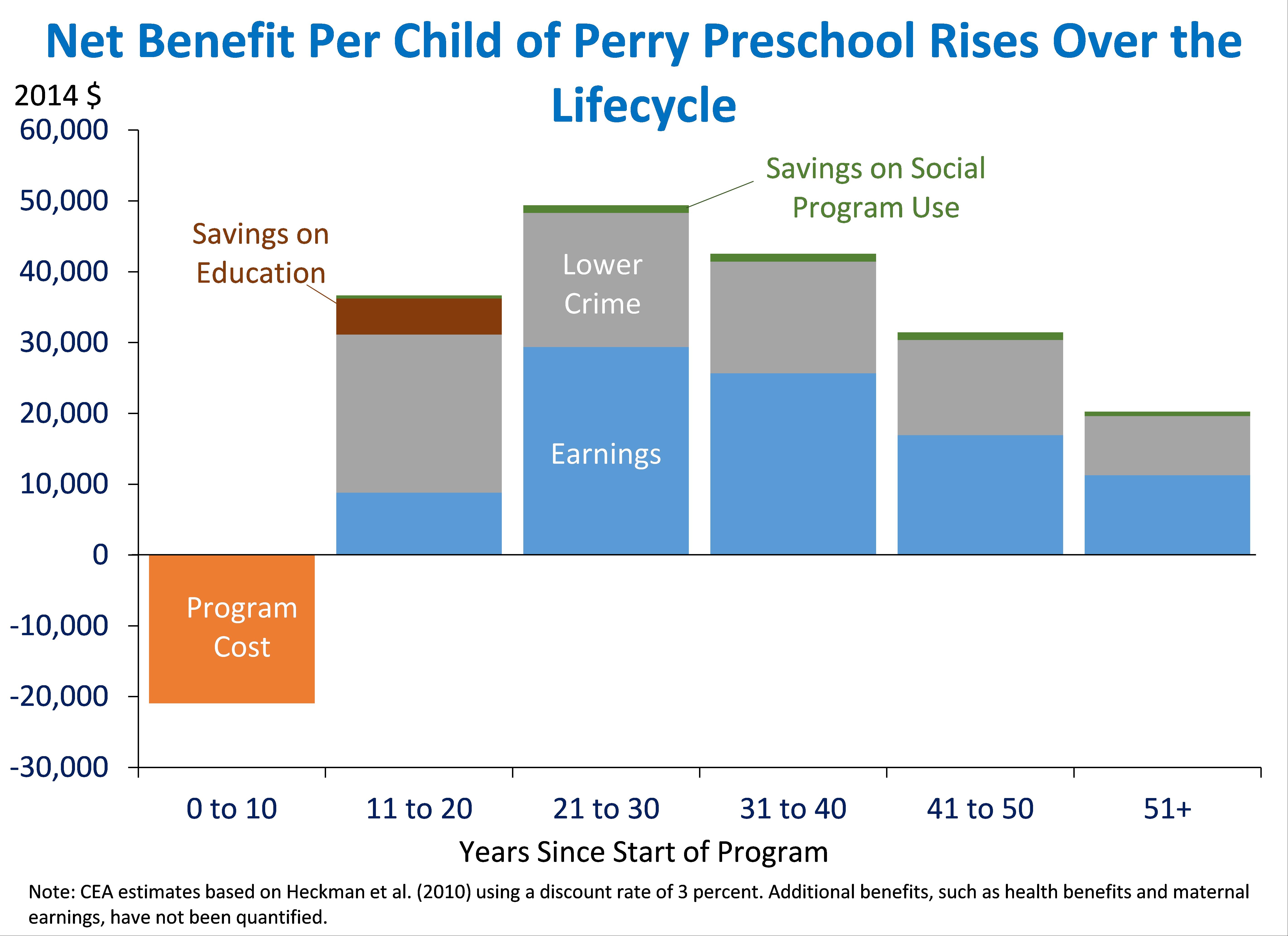

- Two famous randomized trials of relatively small, intensive early education programs targeted to disadvantaged young children were the Abecederian Project and the High/Scope Perry Preschool Study. Both of these programs conducted multiple follow-up surveys of these children through secondary school and into adulthood. A number of studies found that children from these programs saw higher high school graduation and college attendance rates and greater adult earnings, and Perry also showed lower involvement with the criminal justice system. CEA recently summarized this work and concluded early education programs yield positive net benefits of up to $8.60 for every dollar spent.

- Recent work finds that these positive outcomes aren’t limited to narrowly-targeted programs, but that modern programs like Head Start, also show promising results. The Head Start Impact Study (HSIS) is tracking nearly 5,000 children who participated in Head Start as 3- and 4-year olds in 2002-2003. So far, the study has examined children’s outcomes through 3 rd grade. This work showed some positive initial findings, with greater language and literacy outcomes, but these results have become more attenuated over time, as measured by tests in elementary school.

- Even with negligible test score improvements in elementary and middle school, programs can still provide long-term benefits for children. For example, in order to account for differences in all family characteristics (unobserved and observed) David Deming compares differences between siblings in families where one sibling attended Head Start and another did not. Even though this work does show some fade-out, it also shows that in the longer-run, participating children are more likely to graduate high school and attend college.

2. The Earned Income Tax Credit improves early health outcomes, and increases academic achievement and college attendance.

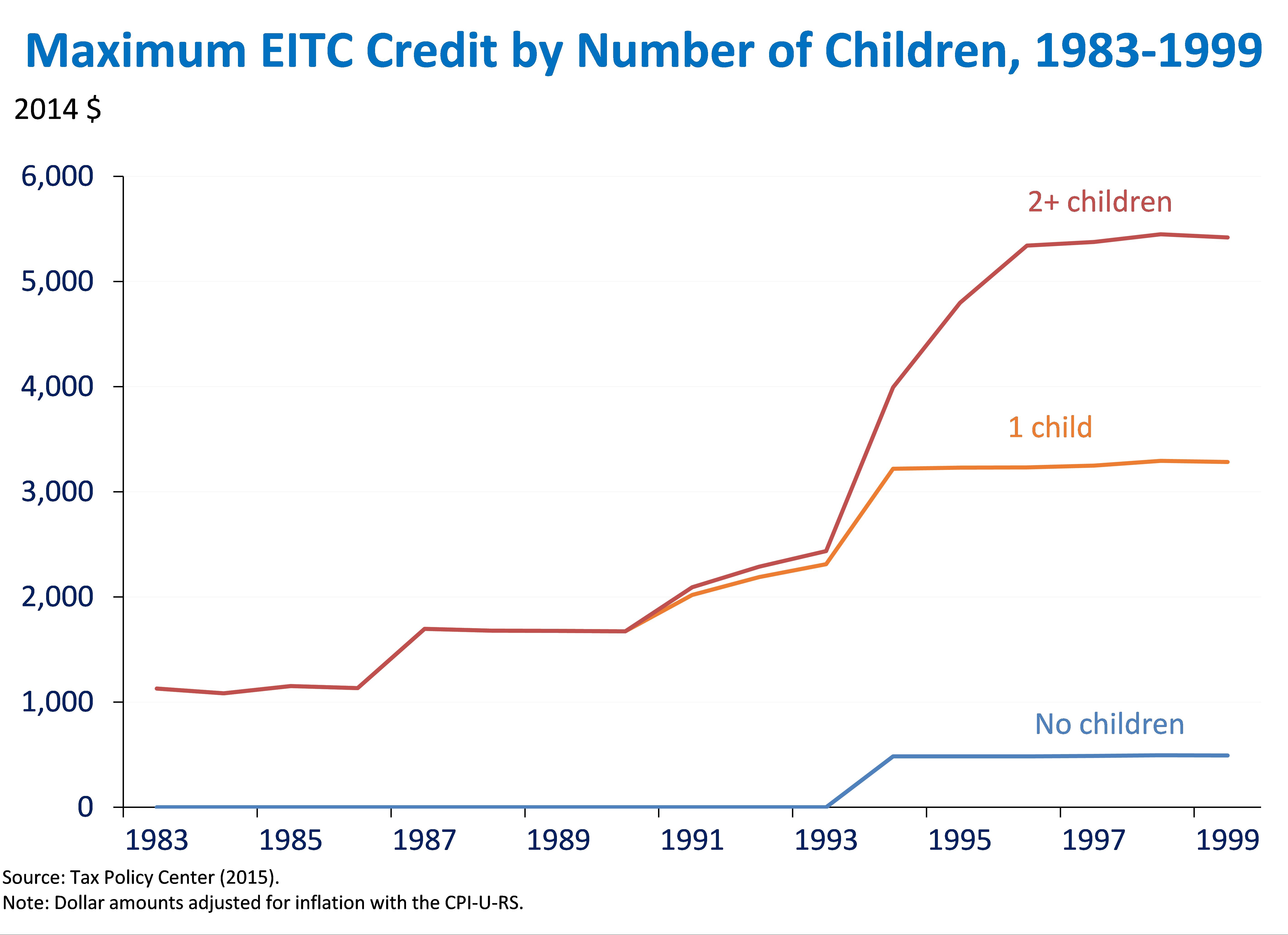

- The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) provides a refundable tax credit to lower-income working families. A family’s credit amount is based on the number of dependent children and its earnings. A long literature shows that the EITC increases labor force participation among single mothers. This work relies on quasi-experimental methods, often comparing families that became eligible for a (larger) credit with families with similar observable characteristics that were ineligible.

- The EITC has been expanded in every Administration since 1975. Examining the 1986, 1990, and 1993 reforms, which expanded the credit parameters, particularly for families with multiple children, Hilary Hoynes, Douglas Miller, and David Simon use Vital Statistics data covering all births from 1984 to 1998. These data provide information on birth weight and birth order, as well as some maternal demographic information. Since families with a first, second, or third and higher-order birth experience a different EITC schedule, the authors compare birth outcomes for single mothers across these groups and find an additional $1,000 in EITC receipt lowers the prevalence of low-birth weight by 2 to 3 percent. Using information from Vital Statistics on doctor visits during pregnancy and from birth certificate records on smoking and drinking during pregnancy, they speculate that one channel for health improvements is through better prenatal care and health.

- The EITC for which a family is eligible increases at very low incomes, then remains flat for families with slightly higher incomes before phasing out. Work by Raj Chetty, John Friedman, and Jonah Rockoff uses these non-linearities in the tax schedule to identify the extent to which the credit improves academic performance. Linking data from a large school district on children’s test scores, teachers, and schools from grades 3 through 8 with administrative tax records on parental earnings, they find that a credit of $1,000 increases elementary and middle school test scores by 6 to 9 percent of a standard deviation. The authors’ related work suggests that the quality of a child’s teacher is correlated with improvements in test scores, but unrelated to other characteristics that might affect earnings (like family characteristics). Using teacher assignment to isolate the causal effect of test scores on future earnings, they estimate that these children’s future earnings gains will exceed the current EITC costs.

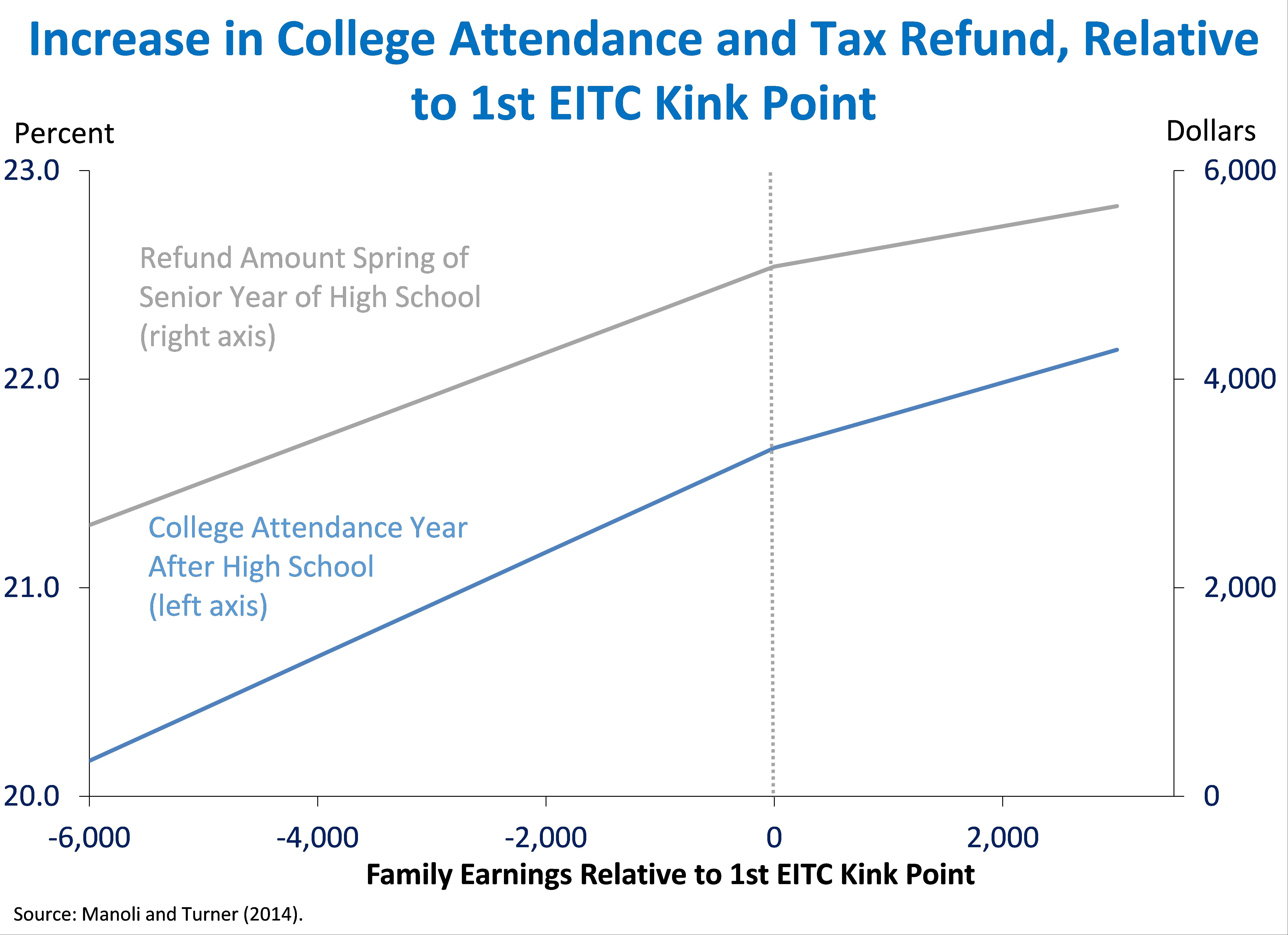

- Using a regression kink design to estimate changes near the EITC’s first kink point and a differences-in-differences estimation using expansions of the EITC’s plateau and phase-out region for married parents, Dayanand Manoli and Nicholas Turner find receiving an additional $1,000 EITC in a student’s senior year of high school increases college enrollment by 0.4 to 0.7 percentage points. While quasi-experimental methods, like regression kink and differences-in-differences strategies, have the potential to provide causal estimates, the validity of these designs often requires very large amounts of data. In this study, tax data provides information on family earnings and composition (from the 1040 form) and subsequent college enrollment (from the 1098-T form) on almost all high school seniors from 2001 to 2011, which enables them to examine how college-attendance behavior changes for children whose families are very close to, but on one side of, the policy change (a flat, rather than increasing, EITC or children of married parents versus single parents).

Even though we do not yet have a fully identified study of long-run earnings data for EITC recipients yet, by improving children’s performance in school, these results suggest the EITC could generate earnings gains in adulthood as well. For example, Chetty, Friedman, and Rockoff estimate that the test score gains will translate into earnings gains of 9 percent.

3. Nutrition assistance programs improve health outcomes and economic self-sufficiency.

- The Food Stamp Program (now SNAP) was rolled out across counties between 1961 and 1975, and the time at which a county implemented the program is largely unassociated with observable county characteristics. Douglas Almond, Hilary Hoynes, and Diane Whitmore Schanzenbach use this phased implementation to compare children from disadvantaged families who were born at similar times, but in different counties, and therefore had differential access to the Food Stamp program. Vital Statistics Natality administrative data that provides information on birth weight and parity and maternal characteristics shows that access to Food Stamps during pregnancy reduces low-birth weight births, with the greatest gains at the lower-end of the birth weight distribution. Related work using similar cross-state variation and linking longitudinal data that follows children throughout adolescence and into adulthood shows that access to Food Stamps before birth and at young ages reduces metabolic syndrome and increases economic self-sufficiency for women.

- Like the Food Stamp program, the Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) was rolled out in stages between 1972 and 1979. Work by Hilary Hoynes, Marianne Page, and Ann Huff Stevens uses this county variation to compare birth information from the Vital Statistics Natality Data among children who were born at similar times, but in different counties (with different in uetro exposure to WIC). These results suggest that WIC increased birthweights among children born to mothers who participated in WIC from the third trimester between 18 to 29 grams, and effects were largest among mothers with low levels of education.

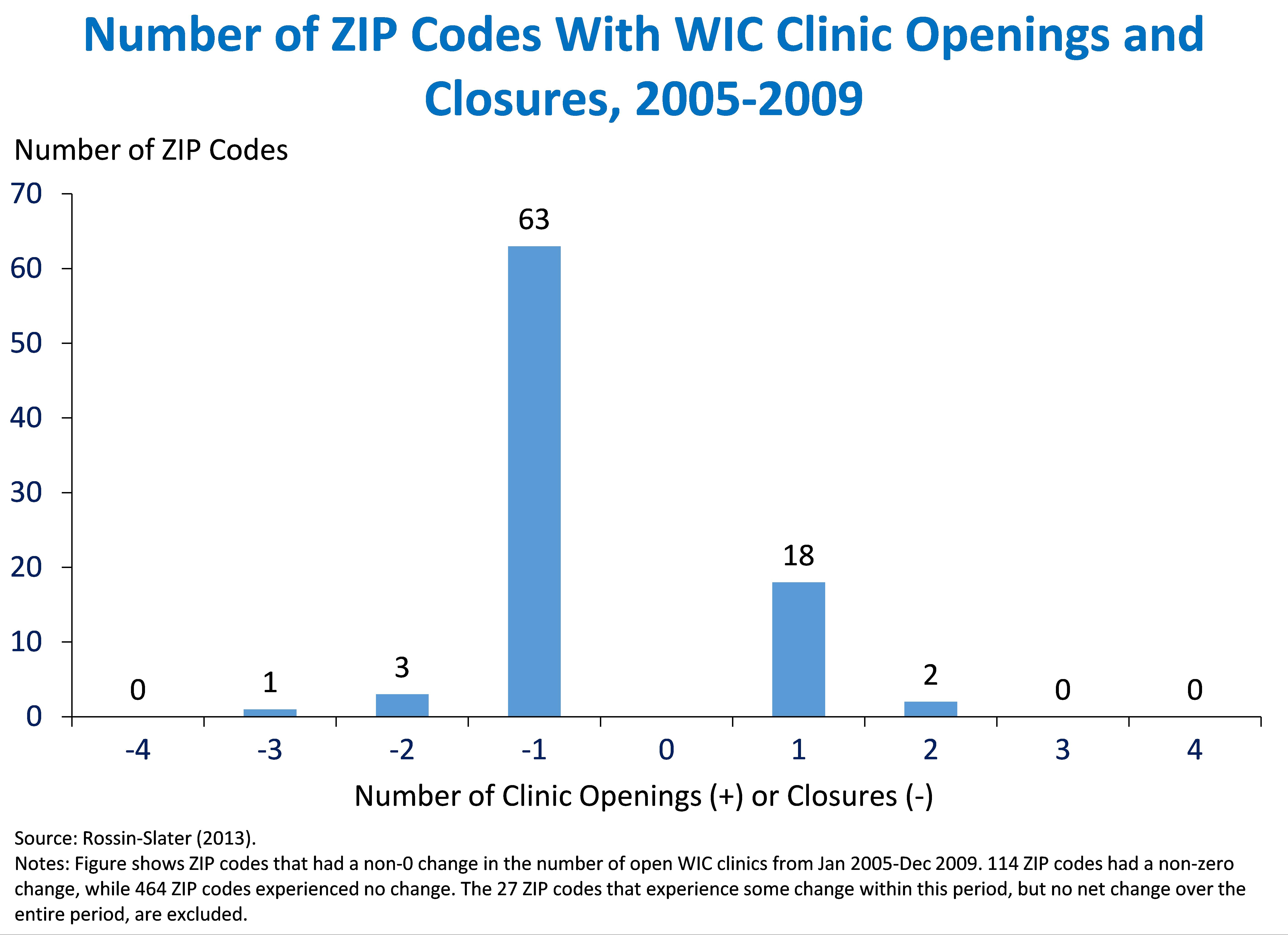

- Other work uses more recent data on access to WIC at finer geographies. In some states, like Texas, clients must apply for WIC in person, and distance to a clinic can present a barrier to access. Maya Rossin-Slater examines data from the Texas Department of State Health Services on WIC clinic openings, which includes operating dates and ZIP codes for all clinics in the state, and birth record data which includes information on birth outcomes and maternal characteristics. In order to isolate the causal effect of WIC access, she compares birth outcomes between siblings, where one sibling was born when a clinic was open nearby but another was born without access to a nearby clinic. This work shows that WIC access increased maternal weight gain during pregnancy, children’s birth weights, and the likelihood of initiating breastfeeding upon discharge from the hospital following birth.

4. Housing assistance that enables families to move to areas with high levels of upward mobility improves college enrollment, adult earnings, and marriage rates.

- From 1994 to 1998, the Moving to Opportunity demonstration project (MTO) randomly selected low-income families living in public housing in areas of concentrated poverty to receive housing vouchers. The experimental voucher group was required to move to neighborhoods with poverty rates below 10 percent, but Section 8 voucher recipients faced no location restrictions. Randomized control trials, such as MTO, are considered the “gold-standard” in economic research since treatment status is, by definition, random, and not correlated with characteristics that might influence future outcomes. As such, randomized experiments can credibly isolate the causal effect of a program. Interim results from the experiment found some benefits to moving to low-poverty neighborhoods, like improvements in mental and physical health among adults and teenage girls , but the fact that it did not lead to earnings increases for adults or test score improvements for children was disappointing.

- In contrast to the earlier literature, work released last week by Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, and Lawrence Katz links the MTO data with administrative earnings data for participating children. Previous work had relied on test score results to infer that the program would have little effect on achievement-related outcomes, or relied on earnings records from the oldest participants, but actual earnings records from a greater share of participants show substantial earnings gains. Among children who were younger than 13 when their families moved, Section 8 vouchers increased earnings by 15 percent and experimental vouchers increased earnings by 31 percent. In addition, MTO increased college attendance by 32 percent and, among children who attended college, children whose families received vouchers went to higher-quality schools. While the program did not affect significantly either overall birth rates or teen birth rates, experimental vouchers did increase the fraction of births where a father was present, and both Section 8 and experiment vouchers increased female marriage rates between ages 24 and 30. In contrast to the results for younger children, older children did not see these positive outcomes, suggesting that the amount of time a child spends in a neighborhood matters for adult outcomes, and providing a reconciliation with the earlier literature.

5. Medicaid/CHIP receipt in childhood improves adult economic and health outcomes.

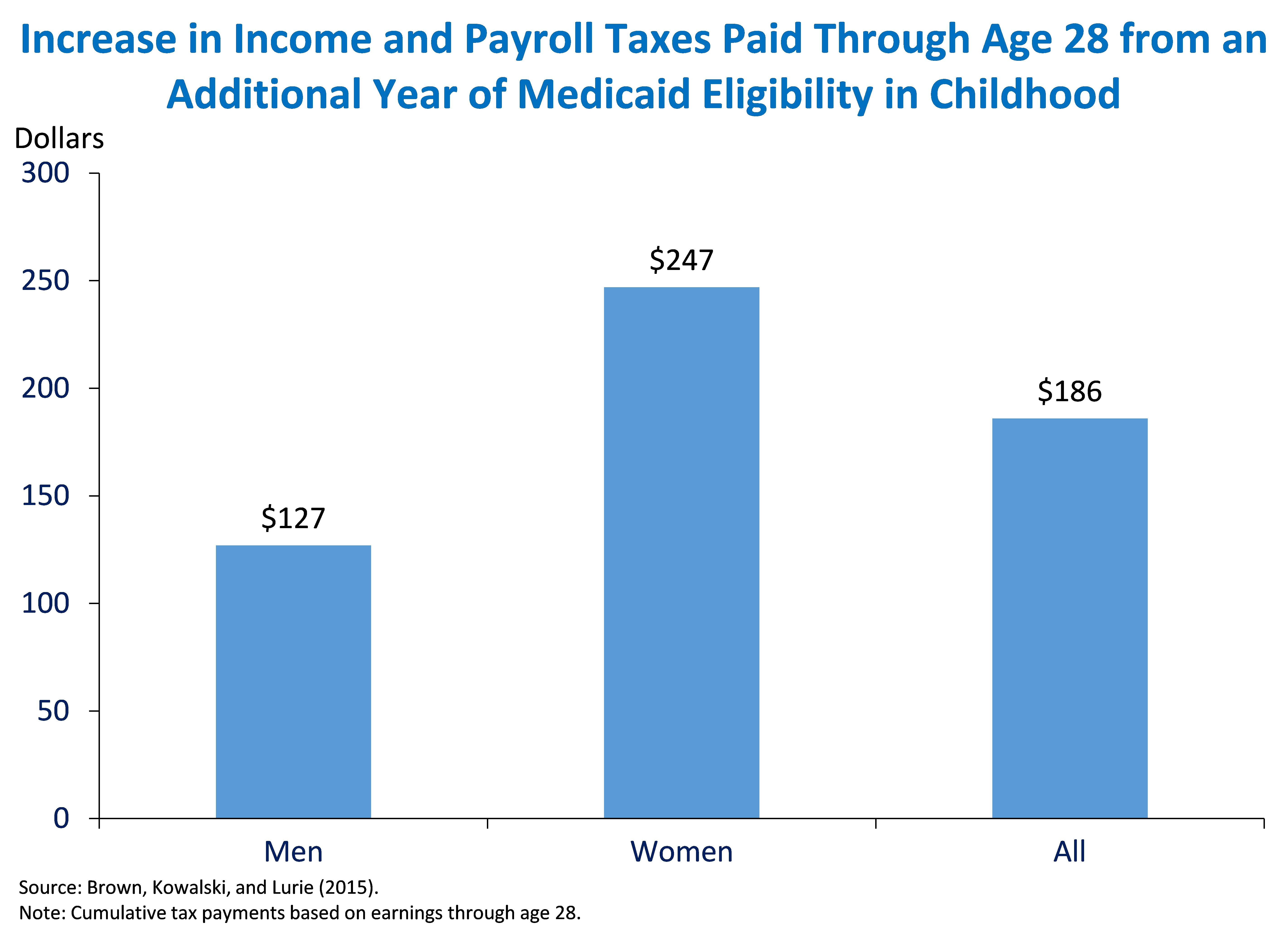

- States expanded access to health insurance for children through Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) at different times and to different extents since the 1980s. Using this variation and administrative data that connect individuals’ adult earnings and tax information to their residence and family income in childhood, David Brown, Amanda Kowalski, and Ithai Lurie estimate that a single additional year of Medicaid/CHIP eligibility in childhood increased cumulative tax payments through just age 28 by $186, a substantial fraction of the cost of that coverage; increasing Medicaid/CHIP eligibility also increased female earnings through age 28.

- Related work by Sarah Cohodes, Daniel Grossman, Samuel Kleiner, and Michael Lovenheim uses similar variation across States and time in Medicaid/CHIP eligibility rules. They find that individuals who were eligible for Medicaid/CHIP in childhood were more likely to complete high school and graduate from college.

- One possible explanation for the improvements in economic outcomes due to Medicaid receipt in childhood is that Medicaid generates long-lasting improvements in health status. Two studies by Bruce Meyer, Laura Wherry, and co-authors examine changes in Federal Medicaid eligibility rules caused children born in October 1983 or later to be more likely to qualify for Medicaid coverage between ages 8 and 14 than children born before October 1983. These studies find that, in the groups most affected by the discontinuity in coverage eligibility, children born during or after October 1983 experience lower mortality in their late teen years and are substantially less likely to be hospitalized as adults.

6. Cash assistance programs that help low-income families make ends meet increase earnings, educational attainment, and longevity.

- Anna Aizer, Shari Eli, Joseph Ferrie, and Adriana Lleras-Muney examined the Mothers’ Pension, a cash assistance program in effect from 1911 to 1935, and a precursor to Temporary Assistance to Needy Families. The authors use data from World War II enlistment records, the Social Security Death Master File through 2012, and 1940 Census records on 16,000 men to compare mortality of children who benefited from the program to similar children of the same age living in the same county whose mothers applied, but were denied benefits. They find that the program reduced mortality through age 87 among recipient children, and that the lowest-income children experienced the largest benefits. Census and enlistment records suggest that these improvements may be at least partly due to the improvements in nutritional status (measured by underweight status in adulthood), educational attainment, and income in early-to-mid adulthood. Documenting that the most common reason for rejection was “insufficient need,” the authors argue their results provide a lower-bound estimate of the program’s effects.

These six examples show that programs can have large and real long-term benefits, even if in some cases interim results based on indirect measures like test scores suggest little effect. They also show how credible research designs and greater access to data can overcome some of the limitations of previous work. Finally, these results suggest that, in some circumstances, greater equity does not necessarily come at the cost of lower economic efficiency. In fact, in instances where cost-benefit analyses are available, the additional tax revenue from the higher long-run earnings stemming from these programs is sufficient to cover most or all of the initial cost. This work shows that many investments proposed in the President’s Budget would help both participants and the overall economy.

Jason Furman is the Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers. Krista Ruffini is a Research Economist for the Council of Economic Advisers.

Watch President Obama's final State of the Union address.

Read what the President is looking for in his next Supreme Court nominee.

Take a look at America's three newest national monuments.

What do you think? Leave a respectful comment.

Laura Santhanam Laura Santhanam

- Copy URL https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/why-the-u-s-is-rethinking-its-approach-to-poverty

Why the U.S. is rethinking its approach to poverty

At least one Saturday each month, Arlean Younger volunteers handing out boxes of donated food at church. Last time, she helped distribute provisions to more than 100 people. At the end of the shift, she took home a box, too — for herself and Mylie Jai, the little girl she has been taking care of since infancy.

Before the coronavirus pandemic, the number of American households in poverty was shrinking. In 2019, 34 million people lived in poverty , a decrease of 4.2 million individuals from a year earlier, according to the Census Bureau. Children made up a substantial portion of those in low-income households, according to the latest available data from a recent National Academies of Sciences study. A year since the coronavirus began its deadly rampage in the U.S., economic stresses have pushed millions more households to the brink, with some estimates suggesting it also forced an additional 2.5 million more children into poverty.

At the end of 2020, more than 50 million people were facing hunger, up 15 million from the year before, according to data from Feeding America , an anti-hunger organization. Millions of Americans have turned to food banks, with four out of 10 doing so for the first time during the pandemic.

Each month, Younger earns roughly $2,000 from her job at a company that hires home health aides. But the money is spent almost as soon as her deposit clears. Rent gobbles up $800. Utilities cost $300. Water adds $130. And $400 goes for the gas she needs to reach her health care clients. There are credit card bills and the new cost of daycare for Mylie Jae, whose school, the cost of which is normally subsidized by the state, shut down. The COVID-19 pandemic has made everything more precarious, including her own work.

Younger’s role is usually that of a manager but often demands more than overseeing client needs and people’s schedules. She supervises eight employees. Because of pandemic-driven demand, Younger said she often cares for clients herself, working far more than 40 hours, sometimes seven days a week. She drives up to 40 minutes each way to reach the clients farthest from her house; the costs are always greater than what her company reimburses her. She feels like she is struggling to provide a good home for the girl who calls her “Mama.”

Lawmakers in the U.S. have for years debated how to track poverty, and child poverty in particular. Now, in the midst of a pandemic, when the country is caught in a deep recession that has forced families deeper into financial difficulty amid widening inequalities, “it’s not surprising” that politicians have found renewed interest in curbing this hardship, said Rebecca Blank, a macroeconomist who worked on anti-poverty policy for the the Clinton and Obama administrations and now serves as chancellor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Chart by Megan McGrew

Along with what it provides in COVID relief, the $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan signed into law by President Joe Biden this month offers one of the most sweeping anti-poverty packages in recent memory. Along with one-time stimulus checks to most children and adults and an extension of unemployment benefits, the legislation increases the child tax credit to between $3,000 and $3,600, depending on the age of the child, and makes that money available over the course of the year rather than only at tax-filing time. It offers housing vouchers for those nearing homelessness, as well as health care subsidies for people whose states have not expanded Medicaid.

One estimate by the Urban Institute suggests these measures will cut child poverty in half for children, and significantly for families experiencing job loss.

READ MORE: How to help kids build resilience amid COVID-19 chaos

In the pandemic, advocates have an opportunity to generate sufficient political will for the U.S. to not only sew up some of the holes in its social safety net, but make it big enough to catch more families and individuals in need. “One thing we know out of American history is when we expand these programs, it tends to be in response to more than just the very poor having need,” Blank said. “When need is more expansive, people are more willing to think about new things.”

The bill only guarantees the expanded tax credit for a year, though Democrats have promised to extend the benefit. The question now: Could this become permanent? If the tax credit expires, the child poverty rate will double again by 2022. Many Republicans, who are seeking to regain control of Congress in the next midterm elections, have voiced concerns about supporting continued assistance, citing costs or because the measures don’t do enough to incentivize work. But advocates say the idea of a long-standing safety net has now entered the conversation, and there are a number of small models of success across the country and over time that lawmakers can draw from when considering solutions.

How the U.S. has attempted to address poverty

For years, the United States has maintained a stubbornly high rate of child poverty compared to other developed countries, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development reported in November 2019 . Traditionally, Americans have bristled at giving taxpayer money to alleviate poverty, especially if that means the government will assume a greater role in people’s daily lives. But not making a serious investment in solving the problem comes with major costs.

Lack of a political will has obstructed greater progress on child poverty are cold and straightforward, said Cara Baldari, vice president, family economics, housing and homelessness at First Focus on Children, a child advocacy organization. “Kids can’t vote,” she said. That has helped perpetuate a trend in the U.S. where children are more likely than adults to live in poverty because a child’s fortune matches that of the grown-up who cares for them.

Child poverty affects an estimated 9.6 million children and costs the U.S. as much as $1.1 trillion each year, according to a 2019 report from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine . Studies suggest children accumulate these costs over the course of a lifetime due to worse health outcomes that end up adding up to expensive treatment and lost productivity in the job market. Children who grow up in poverty are more likely to report lower incomes, worse health outcomes and less likely to experience social and emotional turmoil.

In the 2016 National Survey on Children’s Health, parents reported that 25.5 percent of children have experienced economic hardship “somewhat” or “very often.” By that measure, poverty is the most common adverse childhood experience in the United States — more common than divorce or separation of parents or living with someone struggling with alcohol or substance use. These events offer a heightened risk of trauma that can have potentially lasting effects on a child’s physical, mental and emotional health, according to Child Trends , a research organization focused on studying child development and well-being.

Other countries have made explicit moves in recent years to tackle those kinds of issues. In 2019, Canada’s Poverty Reduction Act became law , part of a $22 billion package to create poverty reduction targets and funnel resources toward programs that can help meet the social and economic need. The country is on track to reduce child poverty by half, according to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. New Zealand has also released intermediate and long-term targets designed to cut child poverty dramatically within a decade. In both countries, people receive direct monthly payments to give families a cushion against poverty.

The U.S. hasn’t yet gotten that far, instead operating multiple policies entangled in a way that sometimes pits them against one another. To stem hunger, the federal government funds Supplement Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP benefits. To help working families, the Earned Income Tax Credit refunds money to individuals based on what was earned and household need. And those who qualify to receive Temporary Assistance for Needy Families are often flagged to receive job training or help securing employment. But families often bump up against income thresholds, earning too little to live comfortably but too much to receive government benefits. Younger, 49, has been caring for Mylie Jai for five years, ever since she offered help to a friend who had just given birth and was hopping between rundown motels in Jackson, Mississippi, without a stable home, car or job. Mylie Jai is now in preschool, and Younger is her official legal guardian. Younger was told she earns too much money to qualify for SNAP benefits, she said.

The Mississippi Department of Human Services normally covers the cost of Mylie Jai’s school, but in late February, the building was shut down after pipes burst in a historic snowfall and ice storm. Younger was forced to instead send Mylie Jae to a small daycare operated by a friend, but the state’s vouchers got caught in bureaucratic red tape, so she said she had to come up with $90 per week out of pocket.

Medicaid covers Mylie Jai’s doctor visits, Younger said, but she herself visits a community health center if she gets sick and cannot afford health insurance, despite being a health care worker.

Arlean Younger, 49, of Jackson, Mississippi, works full-time (and often logging extra hours) for a company that hires home health aides. But she struggles to make ends meet for herself and Mylie Jai, 5, for whom she is the legal guardian. Photos courtesy of Arlean Younger

Those ill-fitting pieces are problematic, said Beryl Levinger, a child policy expert and professor at Middlebury Institute, and policymakers need to take a more holistic approach, rather than hunt for a silver bullet that doesn’t exist.

Levinger also served as a researcher on a new report from child advocacy group Save the Children that used data to analyze which states offered kids the best and worst COVID-19 responses . Minnesota, Utah and Washington state ranked highest while Louisiana, Mississippi and Texas were among the lowest. This latest report suggested 6 million more children endured hunger during the pandemic, and a quarter of children lacked resources for remote learning, which made completing school work virtually impossible for many families. The report urged states to protect child care, which has unraveled during the pandemic, and address child hunger through SNAP and other federal programs.

“This problem will not end even when the last of the vaccine is distributed,” the report said. “The additional benefits and supports for these children and families will need to be made permanent until all children have access to the food they need.”

The debate over cash payments

Created as part of the Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997, the child tax credit offered a $500-per-child nonrefundable credit to ease the tax burden of middle-income households. Since then, it has become more tightly woven into the U.S. social safety net over time, said Elaine Maag, who studies programs for low-income families and children for the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center at the Urban Institute. Decades later, she said the policy has evolved and holds the potential to become a permanent fixture to help families.

But government programs, no matter how well designed or executed to fit a certain set of circumstances, often miss the mark, Maag said, because life is messy. She pointed to SNAP benefits as an example. With them, a person may have food, but if they get sick, do they have money to pay for a doctor’s visit or to fill a drug prescription? A mountain of research that suggests direct cash payments are the most effective way to alleviate poverty and documents a “growing understanding that people know how to solve their problems the best way,” Maag said. “Cash can be used to meet all your needs.”

Of all of the provisions in the latest relief bill, the $1,400 cash payments have the most potential to reduce poverty, according to the Urban Institute’s analysis. In recent years, there has been growing discussion of using a universal income to alleviate poverty, but it is not politically popular. Democratic presidential candidate and philanthropist Andrew Yang campaigned on this idea, but just a fraction of Democrats supported it, much less the country overall. In a July 2019 poll from PBS NewsHour, NPR and Marist , only 26 percent of Americans said they supported giving each U.S. adult $1,000 per month, a proposal that was more popular among Democrats than Republicans.

Despite robust evidence supporting the use of direct payments, Americans historically do not like to give people tax-payer dollars unless society deems them to be deserving, Maag said. Since the Great Depression, older adults, people with disabilities or some survivors of people who die have received cash benefits. But distributing cash payments to families or other more specific groups is an easier political sales pitch than to do so for all able-bodied adults, Maag said.

So for generations, the U.S. has pursued anti-poverty policies that are very specific about how people spend their resources, said Aisha Nyandoro, chief executive of Springboard to Opportunities, a direct service organization. “Why not try something different?”

That is what Nyandoro’s organization did in 2018 when it founded the Magnolia Mother’s Trust. The project gave $1,000 per month for 12 months to Black mothers living in extreme poverty in Jackson, Mississippi. The goal was to target systemic problems by empowering women with cash payments so they could decide how to improve their lives. The project has grown from helping 20 women to more than 200. During that time, Nyandoro said she has witnessed women pay off debt, return to school, cook more nutritious meals for their families and become better parents.

Tamara Ware was one of those women. In late February 2020, she had to leave her job at a child care facility, afraid she might bring the coronavirus home to her three daughters, ages 13, 14 and 17, who were struggling in school even before the virus forced classrooms to close and instruction to go virtual. She had been earning $11 per hour and had no savings to pay for food or housing.

When the COVID-19 pandemic forced Tamara Ware, 36, of Jackson, Mississippi, out of her job at a child care facility, Ware said she did not know how she could afford to raise her three daughters, age 13, 14 and 17. But when she received $1,000 per month for a year from the Magnolia Mother’s Trust, Ware said she could focus on being a more patient, present and understanding parent. For the first time in years, she threw a birthday party for her daughter, Erianna, in July. Photos courtesy of Tamara Ware

Within weeks, Ware was accepted into the trust. She found tutoring help for her daughters and counselors for them to address trauma they had endured, including the grief and loss of Ware’s twin sister, who had been shot and killed eight years earlier. She threw a party to celebrate her daughters’ birthdays, something she hadn’t been able to afford to do in years. She became a more patient and understanding mother, she said, and developed a deep sense of community with other mothers who worked to overcome struggles that had ensnared them for years.

“I could be in the moment,” Ware said. “Look, I ain’t gotta worry about nothing this month.”

She graduated from the program last month, and it gave her a chance to build her own business as a child care provider.

“My head is in the right direction,” Ware said. “I have the tools I need now.”

Many women in the program report feelings of joy, Nyandoro said. Often, that is because they struggled to survive. With a guaranteed income in place, the women’s focus could broaden beyond meeting basic needs and tapping to what they actually wanted in life.

“If you have lived a life of scarcity so often, joy is something you feel like you haven’t been allowed either. You’re constantly trying to survive,” she said. “You tell yourself dreams are something for other people.”

What works?

After the implementation of the “Great Society” programs in the 1960s, such as Medicaid and federal funding for education, the U.S. saw its child poverty rate cut in half. If successful, advocates say the American Rescue Plan could help bring the U.S. and other countries closer to a global goal set in motion by the United Nations (long before COVID-19) to end extreme child poverty by 2030 and cut child poverty rates in half worldwide.

Researchers behind a pilot universal income program that gave participants in Stockton, California, $500 a month released data that showed a 12 percent increase in full-time employment after one year, and 62 percent reported paying off debt, a 10 percent increase from before the program began.

The biggest spending category was food, their research showed, followed by merchandise, utilities and auto costs, which all have an impact on someone’s ability to get and keep a job, researchers said.

More than 40 mayors across the country who are part of a Mayors for Guaranteed Income initiative are launching similar programs.

“COVID-19 has made it very, very clear that you could play by all the rules, that you could be working, and that still may not be enough,” Michael Tubbs, the mayor of Stockton, told the PBS NewsHour in December.

Some economists reviewing Stockton’s pilot have also pointed out the complicated questions that arise around deciding who is eligible for these kinds of programs and how to reach them. Certain requirements may unintentionally cut out people who need help most, in favor of people who don’t have as much need. And cash can only go so far in solving structural issues like access to health care and education.

During the pandemic, fighting poverty has drawn some bipartisan support. Sen. Mitt Romney, R-Utah, proposed the $254 billion Family Security Act to replace some existing programs with a monthly child allowance — $350 for each young child and $250 for every school-aged child. But the cost of this program would mean making choices about discontinuing others, and some experts have raised concerns about the possible unintended consequences of replacing programs, such as TANF, that have been used to connect families to other services. That could lead to families falling through the cracks and needs going unmet.

But some critics say these programs don’t go far enough to incentivize work as a way to alleviate poverty. Robert Rector, a welfare policy expert for the conservative Heritage Foundation, said he doesn’t think the pandemic justifies the child poverty policies passed into law. Instead, he said, the U.S. already has “a very large welfare state,” adding that roughly $500 billion he said is currently devoted to poverty-alleviation programs should be “more efficient” and “targeted to be more supportive of work.”

READ MORE: How the economic relief law narrows the equity gap for farmers of color

The policies targeting child poverty in the American Rescue Plan represent “an enormous expansion of the welfare state” and are only exceeded by the Affordable Care Act, Rector said.

“You want to be compassionate to be people who need assistance, but you don’t want free handouts where an individual can take advantage of the charity extended to them,” he said.

In the 2019 report, researchers suggested expanding benefits to target food and housing insecurity, along with the earned income tax credit and the child tax credit, and creating a child allowance, as Romney’ proposed, which the study found would have the biggest impact on low-income households. Families who claim children as dependents could receive these funds as deposits from the Social Security Administration or even the Internal Revenue Service, according to proposals currently before policymakers. They predicted that those measures could stabilize families in need and reduce child poverty by almost half in the U.S. On a basic level, putting targets in place would help policymakers see if programs like these are making a difference in reducing child poverty, such as how many children and households receive SNAP benefits or if the Census Bureau develops a more accurate measure of poverty based on who actually gets benefits or has health care coverage due to household income.

Rep. Danny Davis, D-Ill., said he sees increased interest in alleviating child poverty as “investing in the future of our country.” While U.S. politics are still intensely polarized, people can still rally behind children, added Davis, who authored the Child Poverty Reduction Act.

“We are at a tremendous crossroads right now in the future of our country, and so, this will help to move America forward and not move America backwards,” Davis said.

That includes people like Younger. She said she feels one major setback away from economic catastrophe, and doesn’t know how long she can keep herself and Mylie Jai afloat.

“Any help at the time of need we’re in right now, I’m thankful for,” Younger said.

She doesn’t allow Mylie Jai to attend birthday parties because she is afraid she might get sick. Her daughter plays with baby dolls and imaginary friends, and loves to play in the park.

For Younger, having a little more money could release her from being pinned down into survival mode each day. She could focus more fully on the moments she spends with Mylie Jai and be empowered to help her secure a better future.

“What would help me is to make sure the little girl I take care of every day grows up to be a prosperous adult,” Younger said.

Laura Santhanam is the Health Reporter and Coordinating Producer for Polling for the PBS NewsHour, where she has also worked as the Data Producer. Follow @LauraSanthanam

Support Provided By: Learn more

Educate your inbox

Subscribe to Here’s the Deal, our politics newsletter for analysis you won’t find anywhere else.

Thank you. Please check your inbox to confirm.

Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Poverty in America — Argumentative Paper: Poverty in The United States

Argumentative Paper: Poverty in The United States

- Categories: Poverty in America

About this sample

Words: 510 |

Published: Mar 16, 2024

Words: 510 | Page: 1 | 3 min read

Table of contents

Root causes of poverty, impact on individuals and society, potential solutions.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr Jacklynne

Verified writer

- Expert in: Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

3 pages / 1528 words

1 pages / 681 words

1 pages / 477 words

2 pages / 1071 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Poverty in America

Poverty in the United States is a complex and multi-faceted issue that affects millions of Americans every day. Despite being one of the wealthiest countries in the world, the United States has a high poverty rate compared to [...]

Homelessness is a pressing issue that affects millions of individuals worldwide. It is a complex problem that arises from a variety of factors, including economic hardship, lack of affordable housing, mental illness, substance [...]

Poverty is a pervasive issue that affects millions of people worldwide. It is a complex problem with no easy solution, but there are several strategies that can be implemented to help alleviate poverty. In this essay, we will [...]

Poverty is a complex and multifaceted issue that has plagued societies for centuries. It has been linked to a myriad of negative effects on individuals, families, and communities. From economic instability to social [...]

At the turn of the 19th century, a Danish immigrant by the name of Jacob Riis set out to change New York City’s slums. Jacob, born in Denmark in the year 1849, emigrated to America when he was 21, carrying little money in his [...]

A small boy tugs at his mother’s coat and exclaims, “Mom! Mom! There’s the fire truck I wanted!” as he gazes through the glass showcase to the toy store. The mother looks down at the toy and sees the price, she pulls her son [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- 20th Century: Post-1945

- 20th Century: Pre-1945

- African American History

- Antebellum History

- Asian American History

- Civil War and Reconstruction

- Colonial History

- Cultural History

- Early National History

- Economic History

- Environmental History

- Foreign Relations and Foreign Policy

- History of Science and Technology

- Labor and Working Class History

- Late 19th-Century History

- Latino History

- Legal History

- Native American History

- Political History

- Pre-Contact History

- Religious History

- Revolutionary History

- Slavery and Abolition

- Southern History

- Urban History

- Western History

- Women's History

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

America’s wars on poverty and the building of the welfare state.

- David Torstensson David Torstensson David Torstensson was awarded his doctoral degree in American history from Oxford University in 2009. The title of his dissertation is “The Politics of Failure: Community Action and the Meaning of Great Society Liberalism.”

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.276

- Published online: 03 March 2016

On January 5, 2014—the fiftieth anniversary of President Lyndon Johnson’s launch of the War on Poverty—the New York Times asked a panel of opinion leaders a simple question: “Does the U.S. Need Another War on Poverty?” While the answers varied, all the invited debaters accepted the martial premise of the question—that a war on poverty had been fought and that eliminating poverty was, without a doubt, a “fight,” or a “battle.”

Yet the debate over the manner—martial or not—by which the federal government and public policy has dealt with the issue of poverty in the United States is still very much an open-ended one.

The evolution and development of the postwar American welfare state is a story not only of a number of “wars,” or individual political initiatives, against poverty, but also about the growth of institutions within and outside government that seek to address, alleviate, and eliminate poverty and its concomitant social ills. It is a complex and at times messy story, interwoven with the wider historical trajectory of this period: civil rights, the rise and fall of a “Cold War consensus,” the emergence of a counterculture, the Vietnam War, the credibility gap, the rise of conservatism, the end of “welfare,” and the emergence of compassionate conservatism. Mirroring the broader organization of the American political system, with a relatively weak center of power and delegated authority and decision-making in fifty states, the welfare model has developed and grown over decades. Policies viewed in one era as unmitigated failures have instead over time evolved and become part of the fabric of the welfare state.

- Great Society

- War on Poverty

- America’s welfare state

- President Johnson

- Community Action Program

Since President Lyndon B. Johnson left office in 1969 competition between America’s two major political parties has in many ways centered on their relationship to the conflicts of the late 1960s. On most major issues, whether it is how the United States is governed, what role the federal government should play vis-à-vis the states, how minorities—ethnic or sexual—should be treated, or the role of the Supreme Court in interpreting the Constitution, the real and imaginary divisions the 1960s spawned continue to profoundly shape American politics. By and large these divisions have discredited American liberalism, making the 1960s known as the decade of “liberal overreach.” 1 American conservatives have for decades argued that the expansion of government through the Great Society programs was a mistake and often failed to help its intended recipients, the poor and underprivileged. 2 Charles Murray in his mid-1980s social policy blockbuster Losing Ground flatly stated that: “We tried to provide more for the poor and produced more poor instead. We tried to remove the barriers to escape from poverty, and inadvertently built a trap.” 3

While historians and social scientists have generally been more nuanced in their assessment of the Great Society, there is still a distinct sense in the literature that if not outright failures, the Johnson administration’s social programs did not live up to their expectations and were, at the very least, a missed opportunity. 4 Indeed, in one of the leading textbooks on American postwar history William Chafe has argued that the antipoverty effort was fundamentally flawed because policy makers never realized that what was really needed to fight poverty was a massive jobs program and redistribution of income. Other historians have agreed. They have argued that a massive program of employment and/or large-scale income redistribution would have been much more successful and desirable than the War on Poverty. 5

This broadly negative judgment on the Great Society (and in particular the War on Poverty) has become part of the wider narrative on the American welfare state. Ramshackle and largely ineffective, it is often accused of and criticized for not living up to the size and standards set by other developed countries, most notably in Europe. The manner in which the United States fights (or doesn’t fight) poverty is an important example often referred to as illustrating this broader point. Negative pronouncements are made every year in conjunction with the Census Bureau’s publication of the official poverty rates. The perennial questions asked are variations on if America needs a new war on poverty or why decades on (since the original 1964 launch) the war is still being lost. 6 Indeed, critics of varying political colors point to how rates of poverty have barely budged since the mid-1960s and that compared to European countries the United States is far behind and spends ever less on the poor. 7 In the late 1950s and early 1960s the poverty rate stood at over 20 percent. 8 By the early 1970s this had fallen to close to 10 percent and the U.S. Census Bureau’s latest ( 2013 ) estimated rate is 14.5 percent. 9 For example, noted economist and public policy doyen Jeffrey Sachs in 2006 argued in Scientific American that the United States (and other “Anglo Saxon” modeled countries) had fallen behind the high-tax and high-spend Nordic region on most indicators of economic performance. 10 He claimed that “the U.S. spends less than almost all rich countries on social services for the poor and disabled, and it gets what it pays for: the highest poverty rate among the rich countries and an exploding prison population.” 11 Others have argued a similar point. In 2001 a National Bureau of Economic Research paper argued that the United States was indeed much less generous to its poor and did not fight poverty as well as many European countries. 12 The authors argued that this was primarily a result of a political system that by and large was geared against income redistribution and a concomitant lack of broad public support for income redistribution primarily due to racism.

The Great Society and War on Poverty programs offer a fascinating prism for understanding the evolution of the 20th-century American welfare state. Its postwar development is not only a story about a number of “wars” or individual political initiatives against poverty, but also about the growth of institutions within and outside government to address, alleviate, and eliminate poverty and its concomitant social ills. From the New Deal to modern-day reform efforts including the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 , the expansion of Medicare and Medicaid coverage through Medicare Part D and the most recent Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, one of the key characteristics of the American welfare state is its piecemeal and gradual evolution. While there have been a number of “big bang” reform efforts, overall the story of the postwar period is the incremental development of a welfare state that has evolved and changed as part of other major political and socioeconomic changes and processes. This development has not been driven only by a policy or reform initiative’s perception of success; more intriguingly, policies and reforms considered as grave political errors or failures in a particular era have over time become staples of American social policy. In this respect the Johnson administration’s War on Poverty initiative is instructive. It was largely discredited at the time and since, and few would argue that the Great Society and War on Poverty have an enviable reputation—political or otherwise. Yet the faith of its biggest and most maligned component—the Community Action Program—illustrates how a social policy can fail politically and by reputation, yet survive. Over the long-term the program itself and the ideas underpinning it have become an institutionalized and elemental part of the American welfare state.

“Fighting Man’s Ancient Enemies”: The War on Poverty and Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society

I want to be the President who educated young children to the wonders of their world. I want to be the President who helped feed the hungry and to prepare them to be taxpayers instead of taxeaters. I want to be the President who helped the poor to find their own way and who protected the right of every citizen to vote in every election … This great, rich, restless country can offer opportunity and education and hope to all: black and white, North and South, sharecropper and city dweller. These are the enemies: poverty, ignorance, disease. They are the enemies and not our fellow man, not our neighbor. And these enemies too, poverty, disease, and ignorance, we shall overcome. 13 — Lyndon Johnson, Special Message to the Congress, March 15, 1965 Johnson’s cause—the thing for which he hoped to be remembered—was the Great Society, his effort to outpace the New Deal, outflank group conflict, override class structure, and improve the lot of everybody in America. 14 — Richard Neustadt, in Presidential Power , 1976 edition

When he spoke about poverty, Lyndon Johnson spoke with passion. Whether it be from his childhood growing up in rural Texas, his experience from a year out from college teaching destitute Mexican schoolchildren in Cotulla, south Texas, or in his first major political assignment during the mid to late 1930s managing the Texas National Youth Administration, the 36th president of the United States had a deeply personal relationship with poverty. Throughout his years in public office, in speeches and on the campaign trail, Johnson would frequently—no matter what the topic—revert back to images of the poor and of the basic needs and wants of all peoples, regardless of their color or background. In his public and private remarks the president expressed his belief that most people had the same basic wants and desire for education, medical care, and an opportunity to lift themselves out of poverty. Because this conviction was absolutely central to his presidential program, Johnson never saw the War on Poverty and poverty itself as being discrete policy issues isolated from his overall domestic program. On the contrary, most of the Great Society’s legislative goals and victories—the extension of civil rights, voting rights legislation, setting federal standards and providing funding for elementary and secondary education, funding health care for the elderly and poor through Medicare and Medicaid—were part of the same idea of building on the New Deal to provide and extend equality of opportunity to all. 15

But poverty was never defeated. Instead of leading the fight on poverty, the President’s Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) and its local staff were accused of playing an active part in the Newark riots of 1967 , funding criminal gangs in Chicago, supporting the staging of racist theater performances in New York City, and embezzling federal money in Mississippi. Such key War on Poverty components as Community Action, the Job Corps, Legal Services, Upward Bound, and even the popular Head Start, were often mentioned in sensational news stories of violence, corruption, and financial mismanagement. Almost as quickly as it had risen to the top of the national policy agenda, the War on Poverty and its programs became one of the topics the president and White House least wanted to discuss. By the end of LBJ’s presidential term when poverty as an issue did present itself, it was in the context of the growing welfare rights movement and the newfound militancy of the poor. Revealingly, for these the president did not have much sympathy. For example, during the summer of 1968 the Poor People’s Campaign—originally a campaign idea by Martin Luther King Jr.—marched and set up a camp in Washington DC. Giving speeches and meeting with administration officials, the campaign demanded that the federal government and Congress do more for minorities and the poor. But the president was not moved. Illustrating just how much the times had changed from four years earlier, when the antipoverty campaign had been launched and Johnson had laid out his Great Society vision, LBJ complained to Agriculture Secretary Freeman: “the very people we are seeking to help in Medicare and education and welfare and Food Stamps are protesting louder and louder and giving no recognition or allowance for what’s been done.” 16 In a remarkable glimpse of the subsequent staple conservative criticism that was to define the Great Society in a post-LBJ world, the president lamented the undesirable social consequences that his programs seemed to have resulted in: “Our efforts seem only to have resulted in anarchy … The women no longer bother to get married, they just keep breeding. The men go their way and the women get relief—why should they work?” 17 If Vietnam became LBJ’s foreign policy albatross, the War on Poverty was viewed by many as his domestic one. Indeed, Time magazine in 1966 wrote that “next to the shooting war in Viet Nam, the spending war against home-front poverty is perhaps the most applauded, criticized, and calumniated issue in the U.S.” 18

Not much has changed since the 1960s. Ronald Reagan’s famous 1987 sound bite—“we had a war on poverty—poverty won” 19 —if not a wholly accepted verdict, still rings true to a lot of subsequent observers and the American public. Indeed, the chief political legacy of the Great Society and War on Poverty programs can best be understood through this prism of chaotic failure. Politically the results have been stark and largely negative for the Democratic Party. Drained by the war in Vietnam and the general perception that although government programs were not directly responsible for urban rioting and student militancy, they were not doing enough to discourage them, the Johnsonian brand of consensus politics that had so dominated the Democratic Party for nearly two decades fell apart. Beginning in 1968 Democrats in a post-Johnson world embraced what many voters deemed social and political radicalism and abandoned the center ground. Indeed, presidential elections since have often been fought on the issues and perception of the issues permeating from the 1960s. In the words of former presidential speech writer to George W. Bush David Frum, Republicans have been “reprising Nixon’s 1972 campaign against McGovern for a third of a century.” 20 The results have been profound: since 1968 virtually no Democratic presidential candidate either running as a self-described liberal or labeled as one by his Republican opponent has won an election. In fact, those who have run as outspoken liberals—George McGovern in 1972 and Walter Mondale in 1984 —lost forty-nine states each and were beaten in some of the biggest landslides in American electoral history.

For the American welfare state the political legacy and poor reputation of the Great Society programs have meant that it has often found itself facing criticism of not doing enough for its intended recipients while maintaining a deep unpopularity with the general public. As sociologist John Myles has put it, there is a general perception that “for middle-aged, middle-income Americans, the welfare state is virtually all cost and no benefit.” 21 Yet while critical in contributing to these negative perceptions of the welfare state, the negative political history and legacy of the Great Society is only half of the story. Paradoxically, many of the most heavily criticized anti-poverty programs are the most misunderstood, as they have had, and continue to have, a long-lasting impact on social and welfare services in the United States.

Maximum Feasible Misunderstanding: The Community Action Program and the Divisions of the 1960s

While more famous programs, such as Project Head Start and Legal Services, have achieved higher levels of visible success and entrenchment within the American social policy framework, it is arguable whether any of the War on Poverty programs have been more influential on American social policy than the Community Action Program (CAP).

When it was launched in the mid-1960s, Community Action was meant to be a way of funneling federal support directly to local communities and involving these communities in the design and implementation of local anti-poverty action programs. It was in many ways intended to bypass conventional interest groups and involve a multitude of stakeholders. Indeed, communities consisting of the poor, local government, and business and labor interests would come together and form not-for-profit Community Action Agencies (CAAs) to coordinate, engage, and devise plans for tackling the problems of local poverty. The CAP designers believed that locally planned and implemented programs would stand a better chance of successfully fighting poverty and coordinating existing federal, state, and local efforts than any program that was centrally designed and managed through existing federal departments. In particular this was a view supported and promulgated by the president’s economic counselors including Walter Heller and Charles Schultze of the Council of Economic Advisors (CEA) and Bureau of the Budget (BOB), respectively. Yet the CAP quickly became one of the Johnson administration’s most heavily criticized and maligned programs. At root was a basic and unresolved disagreement over what Community Action actually meant.

To some the idea of Community Action was simply a management vehicle, a way of coordinating the many disparate and overlapping anti-poverty programs existing within the federal, state, and local bureaucracies. Community Action was in this light viewed as a deliverer and coordinator of services to combat poverty. Certainly, consultation with the poor and participation of the poor were elemental parts of this approach, but this version of Community Action was not about political or social empowerment. It was simply a new way of more efficiently coordinating programs and engaging the poor in an effort to help them help themselves. 22 Bypassing state government and distributing federal funds directly to the CAAs was administratively a relatively new approach, 23 but one based on what the White House and administration viewed as the “traditional and time-tested American methods of organized community effort to help individuals, families and whole communities to help themselves.” 24 This was also the view held by many in Congress. For example, Republican congressman Albert Quie was a staunch supporter of the Community Action concept, if harsh critic of the OEO, arguing that the Community Action concept devolved power locally. 25 Similarly, Carl Perkins, a member of the House Education and Labor Committee to which the poverty bill was referred to in March 1964 , supported the idea of local community involvement and participation of the poor. 26

But to others, Community Action translated into direct political empowerment—a way of forcefully confronting political and economic power structures. It was a way of taking, and giving, power to the poor by means of confrontation. This type of Community Action was closely associated with the thinking of Saul Alinsky, a former Chicago academic and community organizer who ran several independent community organizations around the country and later became associated with some of the more radical OEO-funded programs in Syracuse and Chicago. Crucially, this brand of Community Action became the popularized perception of the program and was extensively covered by major news outlets and in Congress throughout the 1960s. 27

President Johnson’s views on what Community Action would do to shake up social policy and local government appear to be very different and certainly a lot less radical than those of other proponents of Community Action. As he would later reveal in his memoirs: “This plan [community action] had the sound of something brand new and even faintly radical. Actually, it was based on one of the oldest ideas of our democracy, as old as the New England town meeting—self determination at the local level.” 28 The tragedy of Community Action, the OEO, and the War on Poverty is that these efforts never had the type of leadership and clarity of purpose that could have made this vision a political reality and from the beginning effectively sidelined the noisy minority of radicals both within the OEO and on the ground. The anti-poverty director Sargent Shriver was never wholeheartedly committed to the Johnsonian view of the War on Poverty and Community Action. While this does not mean that he was committed to a more radical view of Community Action, Shriver’s political ambitions and willingness to cater to some of his more radical constituents and own staff meant that the fundamental confusion about the purpose of Community Action and the War on Poverty—highlighted in management survey after management survey of the agency—was never resolved. 29 When the anti-poverty director finally attempted to grapple with this fundamental problem in 1967 by amending the anti-poverty legislation to include more representation of local government, the OEO had already reached a political endgame. Once the ghettos started burning and conflict and militancy firmly replaced consensus and peaceful civil rights, neither the OEO director nor the White House were in any position to stem the tide.

When CAP was launched, Shriver expressed the sentiment that it relied “on the traditional and time-tested American methods of organized community effort to help individuals, families and whole communities to help themselves.” 30 While this was certainly the view that the president took, Shriver never consistently or convincingly maintained this position. Norbert Schlei, Department of Justice lawyer and drafter of the original Economic Opportunity Act in 1964 , has argued that relatively early on there was a real shift in the emphasis of the poverty program, a shift that came from the anti-poverty director himself:

I think the whole concept [of maximum feasible participation and Community Action] began to evolve and it got to be much more this matter of putting the target population in charge, putting the local people in charge of the federal money … I really hadn’t understood that that was part of it … I think that even while it was not yet passed [the EOA] there appeared some drift in the whole thinking about community action … Some of it came out of Shriver. I would hear Shriver say things that made me feel that there had been some evolution in thinking since I was directly involved … the idea of putting the target population in a power position and the idea of putting the local government people in a power position seemed to me to be talked about like they were much more integral to the whole idea than I had understood originally. 31

Other OEO insiders have supported this view. For example, Eric Tolmach, who worked on CAP in the OEO, has also described Shriver as sending very mixed messages to those within the agency who supported radical Community Action. Tolmach argued that Shriver felt that by supporting radical CAPs “it separated him from the average bureaucrat in town, and it gained him some credibility on the one hand with large groups of people who were for doing this kind of thing, and with the poor.” 32 This is an important aspect of the history of the War on Poverty as it ties in with the bigger narrative of the changing politics of poverty and the Democratic Party during the mid to late 1960s.

Ambitious Democratic politicians such as Sargent Shriver and Bobby Kennedy—and even some Republicans like New York mayor John Lindsay 33 —saw the radicalization of the political discourse that permeated this period as an opportunity as well as a shift in how future elections and voters would be won. For Shriver, building up and maintaining a natural constituency through the poverty programs was a way of connecting with this new type of politics and its new constituents. Indeed, some have argued that this was in fact Shriver’s raison d’être for staying on as OEO director. In his oral history interview for the Johnson library, Ben Heinemann (chairman of one of the internal White House policy task forces) described Shriver’s and the president’s working relationship as “terrible” and commented that the only reason Shriver stayed on was “ambition” and a desire to “remain in the public view.” 34 The anti-poverty director, Heinemann said, “didn’t have a good alternative [to the War on Poverty] that would still have been in the public eye.” 35 That he was intent on running for office was clear to Heinemann, who described Shriver in 1967 as being “anxious to talk … about the possibilities of his running for Governor in Illinois in ’68.” 36

But Shriver’s constituency and brand of New Politics did not have the kind of national electoral impact for which he had hoped. In 1968 the Democratic presidential coalition fell apart with Richard Nixon and George Wallace combining to shave off almost 20 percentage points off LBJ’s 1964 margin of victory over Goldwater. The New Politics never emerged as a winning electoral force; instead, it created the bedrock for the success of the Republican coalition. In no small measure this was caused by the perceived radicalism of the New Politics constituents: younger voters, Vietnam protesters, and radical civil rights and welfare activists. Many of these groups took their roots in the poverty programs and the type of militancy that became the public image of the OEO. These groups contributed to splitting the Democratic Party by pushing white blue-collar voters into the GOP and shaping subsequent winning Republican presidential coalitions. When Shriver finally ran as George McGovern’s vice presidential candidate in 1972 , Richard Nixon leaned heavily on his opposition to this New Politics coalition and scored a historic victory on par with Johnson’s eight years earlier. Similarly, in 1976 when Shriver was a candidate for the Democratic presidential nomination, he did not win a single primary; his best showing was in Vermont, where he came in second, gaining 28 percent of the vote and losing to the eventual nominee, Jimmy Carter.