Click here to see consultants who can help you with Casper and interview prep!

- March 30, 2024

6 Important Tips for the AMCAS Personal Statement (AMCAS PS)

AcceptedTogether Consultants

We are admissions consultants dedicated to helping you get into your dream school

- Medical School

Recent Posts

Amcas: 5 critical points to make you stand out, aacomas: 6 important steps to stand out, 3 critical tips for the amcas work and activities section, tmdsas application: a 6 point comprehensive guide.

CLICK ON THE SECTION TITLE TO JUMP TO IT!

Introduction

Understanding the amcas personal statement.

Explanation of what the AMCAS Personal Statement is.

Discussion of the character limit and its implications for content.

Crafting a Compelling Narrative

Importance of storytelling in the personal statement.

Tips for selecting experiences that highlight unique qualities.

Show, Don’t Tell: Demonstrating Your Qualities

Strategies for illustrating personal attributes through specific examples.

Avoiding the trap of simply listing achievements.

Addressing Challenges and Setbacks

How to effectively discuss obstacles without dwelling on them.

Balancing honesty with positivity.

Making Your Statement Stand Out

Techniques for creating a memorable and distinctive personal statement.

The role of reflection and personal growth in the narrative.

The Role of Feedback and Revision

Importance of seeking constructive criticism from trusted sources.

The iterative process of refining the personal statement.

The pivotal milestones in your medical school application path is crafting an exceptional AMCAS Personal Statement. This crucial component of your application is more than just a formality; it’s a canvas for your narrative, a platform to showcase your passion for medicine, and a chance to stand out the thousands of aspiring physicians. The AMCAS Personal Statement is your opportunity to go beyond the numbers and give the admissions committee a glimpse into your character, your motivations, and your vision for your future in healthcare.

Navigating the 5,300-character limit can feel like a tightrope walk, balancing between being concise and expressive. It’s about finding that sweet spot where your experiences, aspirations, and the essence of who you are come together to form a compelling story. This narrative is your ticket to capturing the attention of medical school admissions officers and making them see not just an applicant, but a future doctor with a unique perspective and a heart full of determination. Let’s dive into how you can make your personal statement a memorable and impactful part of your medical school application.

Explanation of what the AMCAS Personal Statement is

At its core, the AMCAS Personal Statement is your chance to transcend beyond grades and scores. It’s about telling your story in a way that highlights your passion for medicine, your empathy, your resilience, and your commitment to the field. Through this narrative, you’re given the freedom to illustrate the experiences that have shaped you, the challenges you’ve overcome, and the moments that solidified your decision to pursue medicine. Unlike the quantitative data that fills the rest of your application, this qualitative aspect allows you to connect on a more personal level with those deciding your fate in the medical field.

Crafting a statement that leaves a lasting impression requires introspection and a deep understanding of what drives you. This isn’t about reiterating your resume; it’s about peeling back the layers to reveal the real you. The AMCAS application facilitates this conversation between you and the admissions committee, providing a platform for you to articulate your personal journey towards medicine.

Discussion of the character limit and its implications for content

Navigating the 5,300-character limit of the AMCAS Personal Statement might seem daunting at first. This restriction places a premium on your ability to communicate efficiently and effectively, challenging you to distill your experiences and aspirations into a concise yet powerful narrative. Every word counts, pushing you to think critically about what details are truly essential to your story and which ones can be left unsaid.

This character limit encourages precision. It forces you to prioritize the experiences that best represent your journey, highlighting the resilience, empathy, and dedication that have propelled you toward a career in medicine. In this space, you must strike a balance between depth and brevity, ensuring that each sentence contributes to the overarching narrative you wish to convey. The constraint isn’t just a limit; it’s an opportunity to fine-tune your message, ensuring that your personal statement is both compelling and focused.

Moreover, the character limit underscores the importance of reflection in the application process. Deciding what to include and what to omit isn’t just about storytelling; it’s about understanding yourself and what defines you as a future medical professional. This introspective process can illuminate your path to medicine in ways you hadn’t considered, providing a clearer vision of who you are and the doctor you aspire to be.

In essence, the AMCAS Personal Statement is more than an essay; it’s a narrative mosaic of your journey to medicine. The character limit shapes this narrative, ensuring that each word serves a purpose, each sentence builds your case, and the final product paints a vivid picture of your passion for and commitment to the field of medicine.

The AMCAS Personal Statement is more than just an academic essay; it’s a storytelling opportunity that allows you to weave together the threads of your experiences, aspirations, and personal growth. Crafting a compelling narrative is crucial in making your application stand out in the competitive landscape of medical school admissions.

Importance of storytelling in the personal statement

Storytelling is a powerful tool in the AMCAS Personal Statement because it transforms your application from a mere collection of achievements into a memorable and engaging narrative. A well-crafted story can convey your passion for medicine, demonstrate your resilience, and provide insight into your character in ways that data and statistics cannot. It’s about showing the admissions committee who you are, not just telling them.

Through storytelling, you can connect emotionally with the reader, making your application more relatable and human. This emotional connection can be the difference between a forgettable essay and one that resonates long after it’s been read. A narrative approach allows you to highlight the journey that has led you to pursue a career in medicine, showcasing your growth, challenges overcome, and the moments that have defined your path.

Tips for selecting experiences that highlight unique qualities

When selecting experiences for your narrative, it’s essential to choose those that showcase your unique qualities and align with the values of the medical profession. Here are some tips to help you identify and highlight these experiences in your AMCAS Personal Statement:

1. Reflect on pivotal moments : Think about the experiences that have had a significant impact on your decision to pursue medicine. These could be clinical encounters, volunteer work, research projects, or personal challenges. Focus on moments that sparked your interest in healthcare or reinforced your commitment to the field.

2. Showcase your growth : Select experiences that demonstrate your personal and professional development. Admissions committees are interested in seeing how you’ve evolved over time and how your experiences have shaped your understanding of medicine.

3. Highlight your empathy and compassion : Medicine is a field that requires a deep sense of empathy and compassion. Include experiences that illustrate your ability to connect with others, understand their perspectives, and provide support during difficult times.

4. Demonstrate resilience and adaptability : The journey to and through medical school is challenging. Share experiences that showcase your resilience in the face of adversity and your ability to adapt to changing circumstances.

5. Emphasize teamwork and collaboration : Medicine is inherently collaborative. Highlight experiences that demonstrate your ability to work effectively in teams, communicate clearly, and contribute to shared goals.

6. Be authentic : Choose experiences that genuinely reflect who you are and what matters to you. Authenticity is key to creating a narrative that feels true to your character and resonates with the admissions committee.

By carefully selecting experiences that highlight your unique qualities and weaving them into a cohesive narrative, you can create an AMCAS Personal Statement that not only stands out but also provides a compelling glimpse into your journey to medicine.

In the AMCAS Personal Statement, the statement “show, don’t tell” is a guiding principle that can transform your essay from a mere recitation of accomplishments into a vivid portrayal of your character and potential as a future physician. This section explores strategies to bring your qualities to life and avoid the common pitfall of merely listing achievements.

Strategies for illustrating personal attributes through specific examples

To effectively demonstrate your qualities, you need to provide specific examples that showcase these attributes in action. Here are some strategies to help you do that:

1. Use vivid anecdotes : Share detailed stories from your experiences that highlight your qualities. For example, instead of stating that you are empathetic, describe a moment when you comforted a patient or connected with someone from a different background.

2. Focus on your actions and reactions : Illustrate your qualities through your actions and responses to various situations. Show how you solved a problem, overcame a challenge, or made a positive impact on others.

3. Provide context : Set the scene for your examples by providing enough background information. This helps the reader understand the significance of your actions and the qualities they demonstrate.

4. Reflect on your experiences : Don’t just describe what happened; reflect on what you learned and how it shaped your understanding of medicine or your personal growth. This reflection shows depth and self-awareness.

5. Use specific, concrete details : Rather than using general statements, use specific details to paint a vivid picture of your experiences and the qualities they reveal.

Avoiding the trap of simply listing achievements

While it’s important to highlight your accomplishments, your AMCAS Personal Statement should not read like a resume. Here’s how to avoid turning your essay into a mere list of achievements:

1. Prioritize quality over quantity : Instead of trying to include every achievement, focus on a few meaningful experiences that showcase your most relevant qualities.

2. Integrate achievements into your narrative : Incorporate your accomplishments naturally into your story, showing how they are a result of your qualities and how they have prepared you for a career in medicine.

3. Explain the significance : Don’t just mention an achievement; explain why it matters. Discuss the skills you developed, the challenges you overcame, and the impact it had on your journey to medicine.

4. Show the journey, not just the destination : Instead of just stating that you received an award or achieved a high grade, describe the effort, dedication, and growth that led to that accomplishment.

5. Balance humility with confidence: Be proud of your achievements, but maintain a tone of humility. Acknowledge the contributions of others and the opportunities that allowed you to succeed.

By focusing on illustrating your qualities through specific examples and integrating your achievements into a cohesive narrative, your AMCAS Personal Statement will provide a compelling and authentic portrayal of who you are and why you are destined for a career in medicine. Remember, the goal is to show the admissions committee the depth of your character, not just the breadth of your accomplishments.

The journey to medical school is often marked by hurdles and setbacks. In your AMCAS Personal Statement, discussing these obstacles is not just about showcasing resilience but also about revealing depth, growth, and a balanced perspective on your journey. Let’s explore how to approach this aspect of your narrative effectively.

How to effectively discuss obstacles without dwelling on them

Discussing challenges in your AMCAS Personal Statement requires a delicate balance. You want to acknowledge the difficulties you’ve faced without letting them overshadow your achievements or the positive aspects of your journey. Here’s how to strike that balance:

1. Focus on the learning experience : When mentioning an obstacle, quickly pivot to what it taught you or how it contributed to your personal or professional growth. This approach shifts the focus from the challenge itself to the positive outcomes of facing it.

2. Keep it relevant : Choose setbacks that have a direct relevance to your path to medicine or your personal development as a future healthcare provider. This ensures that every part of your story ties back to your central narrative of pursuing a medical career.

3. Be concise : While it’s important to provide context, avoid going into unnecessary detail about the obstacle itself. Instead, spend more time on your response to the challenge and the steps you took to overcome it.

4. Demonstrate resilience : Show how facing these challenges has prepared you for the rigorous path of medical education and the demands of a career in healthcare. Highlight qualities like perseverance, adaptability, and strength.

Balancing honesty with positivity

Your AMCAS Personal Statement is a reflection of your authentic self, including how you handle adversity. Here’s how to maintain a balance between being honest about your struggles and maintaining a positive tone:

1. Acknowledge without exaggeration: It’s important to be honest about the challenges you’ve faced, but avoid dramatizing them. A straightforward, factual approach shows maturity and self-awareness.

2. Highlight positive outcomes : For every challenge discussed, ensure there’s a corresponding positive takeaway or outcome. Whether it’s a lesson learned, a skill acquired, or a new perspective gained, make sure the reader sees the silver lining.

3. Maintain a forward-looking perspective : Emphasize how the obstacles you’ve encountered have equipped you for future challenges. This demonstrates optimism and a readiness to tackle the difficulties inherent in medical training and practice.

4. Show gratitude : If appropriate, express appreciation for the support and opportunities that helped you overcome challenges. This not only shows humility but also acknowledges the interconnectedness of your journey with others.

Addressing challenges and setbacks in your AMCAS Personal Statement is not just about recounting difficulties; it’s about illustrating your journey towards resilience, maturity, and a deeper understanding of the medical profession. By focusing on the lessons learned and maintaining a balance between honesty and positivity, you can craft a narrative that resonates with admissions committees and underscores your readiness for the challenges of medical school and beyond. Remember, the way you discuss obstacles can significantly impact how your overall application is perceived, turning potential weaknesses into demonstrations of character strength and determination.

Creating a memorable and impactful AMCAS Personal Statement is crucial for standing out in the competitive medical school application process. Let’s look at techniques that can help you craft a distinctive narrative and the role of reflection and personal growth in your personal statement.

Techniques for creating a memorable and distinctive personal statement

1. Start with a captivating hook : Begin your AMCAS Personal Statement with an engaging story or anecdote that highlights a key aspect of your journey to medicine. This could be a pivotal moment, a challenging experience, or an inspiring encounter that shaped your decision to pursue a career in medicine.

2. Showcase your unique voice: Your personal statement should reflect your individuality. Use a conversational yet professional tone, and avoid overused phrases or clichés. Share your personal experiences, thoughts, and reflections in a way that only you can.

3. Focus on your strengths and passions : Highlight your strengths, achievements, and passions related to medicine. Emphasize what sets you apart from other applicants, whether it’s your dedication to community service, your research accomplishments, or your unique perspective on healthcare.

4. Be specific and concise : Use specific examples to illustrate your points rather than making general statements. This not only makes your personal statement more memorable but also demonstrates your ability to communicate effectively and concisely.

5. Connect your experiences to your future goals : Demonstrate how your past experiences have prepared you for a career in medicine and how they align with your future aspirations. This shows that you have a clear vision and are committed to your path.

The role of reflection and personal growth in the narrative

1. Highlight personal growth : Your AMCAS Personal Statement should showcase your journey of personal growth and development. Reflect on how your experiences have shaped your character, values, and aspirations.

2. Demonstrate self-awareness : Show that you have a deep understanding of yourself and your motivations for pursuing medicine. Discuss how your experiences have challenged you, what you’ve learned from them, and how they have influenced your decision to become a physician.

3. Emphasize resilience and adaptability : Medical school and a career in medicine are challenging. Highlight instances where you’ve overcome obstacles, adapted to change, or persevered through difficult situations. This demonstrates your resilience and readiness for the rigors of medical training.

4. Incorporate introspection : Use your personal statement to share insights gained from your experiences. Discuss how they have impacted your perspective on medicine, healthcare, and serving others.

5. Connect to your values and motivations : Tie your reflections and personal growth to your core values and motivations for entering the medical field. This creates a cohesive narrative that resonates with admissions committees and underscores your commitment to medicine.

By incorporating these techniques and emphasizing reflection and personal growth in your AMCAS Personal Statement, you can create a compelling narrative that stands out. Remember, your personal statement is an opportunity to showcase your unique journey, qualities, and dedication to a career in medicine. Make it count!

Feedback and revision play crucial roles in shaping a narrative for the AMCAS that truly reflects your journey to medicine. Let’s explore the importance of seeking constructive criticism and the iterative process of refining your personal statement.

Importance of seeking constructive criticism from trusted sources

1. Gaining fresh perspectives : Even the most self-aware individuals can benefit from an external viewpoint. Friends, mentors, or professionals who are familiar with the medical school application process can provide insights that you might have overlooked.

2. Identifying weaknesses : Constructive criticism helps pinpoint areas of your AMCAS Personal Statement that may be unclear, unconvincing, or irrelevant. Recognizing these weaknesses is the first step toward addressing them.

3. Enhancing clarity and coherence : Feedback can highlight sections of your personal statement that lack clarity or fail to convey your intended message effectively. This allows you to refine your narrative for better coherence.

4. Validating your strengths : Positive feedback on certain aspects of your personal statement reinforces your strengths. It’s essential to know what works well so you can maintain those elements during revisions.

5. Building confidence : Constructive criticism, when received from trusted sources, can boost your confidence in your personal statement. Knowing that your narrative has been vetted and approved by others can be reassuring.

The iterative process of refining the personal statement

1. Embracing revision : Accept that your first draft is just the starting point. Be open to making changes, reorganizing content, and rephrasing sentences to improve the overall impact of your AMCAS Personal Statement.

2. Focusing on one section at a time : Break down the revision process into manageable sections. Concentrate on refining one part of your personal statement before moving on to the next. This approach prevents feeling overwhelmed and ensures thorough revisions.

3. Seeking multiple rounds of feedback : Don’t settle for feedback from just one source. Approach different individuals at various stages of the revision process. Each round of feedback brings new perspectives and ideas for improvement.

4. Balancing between revisions and originality : While it’s essential to incorporate feedback, ensure that your personal statement remains authentically yours. Strike a balance between making revisions and preserving your unique voice and experiences.

5. Setting aside time for reflection: After each round of revisions, take a step back and reflect on the changes you’ve made. Consider how each revision aligns with your overall goals and the message you want to convey in your AMCAS Personal Statement.

6. Finalizing with a critical eye : Before submitting your personal statement, review it critically one last time. Check for coherence, clarity, and conciseness. Ensure that your narrative effectively communicates your journey and aspirations in medicine.

The process of seeking feedback and revising your AMCAS Personal Statement is iterative and essential for crafting a narrative that resonates with admissions committees. Embrace constructive criticism, remain open to change, and refine your statement until it accurately reflects your journey and aspirations in medicine.

Check out our database of medical students/resident physicians who can help you achieve the 4th quartile by clicking below:

In crafting your AMCAS Personal Statement, remember that it’s not just an essay; it’s a reflection of your journey, aspirations, and dedication to medicine. By understanding its significance, weaving a compelling narrative, showcasing your unique qualities, addressing challenges with resilience, and ensuring your statement stands out, you set the stage for a successful application. Receiving feedback and embracing the revision process are integral to refining your story, ensuring it resonates with admissions committees. As you finalize your personal statement, keep in mind that it’s your opportunity to share your voice, your experiences, and your vision for your future in medicine. Make it count.

1. What is the AMCAS Personal Statement?

The AMCAS Personal Statement is a crucial component of your medical school application. It’s your opportunity to share your journey, aspirations, and dedication to medicine with admissions committees. This personal statement is your chance to highlight what makes you unique and why you are an ideal candidate for medical school.

2. How long should my AMCAS Personal Statement be?

Your AMCAS Personal Statement should not exceed 5,300 characters, including spaces. This typically amounts to about one page of text. It’s important to use this space wisely to convey your experiences, qualities, and motivation for pursuing a career in medicine.

3. Can I discuss my MCAT score in my AMCAS Personal Statement?

It’s not advisable to discuss your MCAT score in your AMCAS Personal Statement. This section is intended for you to share your personal journey and qualities, not academic metrics. Your MCAT score will already be visible to admissions committees elsewhere in your application.

4. How should I start writing my AMCAS Personal Statement?

Begin by reflecting on your experiences and what led you to pursue medicine. Consider moments that defined your view of the medical field and your potential place in it. Choose a story or theme that can effectively illustrate your passion for medicine and your unique qualities.

5. Should I address setbacks or challenges in my AMCAS Personal Statement?

Yes, addressing setbacks or challenges can showcase your resilience and growth. However, it’s important to discuss these obstacles without dwelling on them. Focus on how you overcame these challenges and what you learned from them, highlighting your strengths and positive attitude.

6. How can I make my AMCAS Personal Statement stand out?

To make your AMCAS Personal Statement stand out, focus on crafting a compelling narrative that highlights your unique qualities and experiences. Use specific examples to demonstrate your attributes and show your personal growth. Reflect on your journey and how it has shaped your desire to pursue medicine.

7. What is the role of feedback and revision in crafting my AMCAS Personal Statement?

Feedback and revision are essential in crafting an effective AMCAS Personal Statement. Seeking constructive criticism from trusted sources can provide valuable insights and help you refine your narrative. Embrace the iterative process of revising your statement to ensure it accurately reflects your experiences and aspirations.

Related Popular Posts

- Terms & Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Application Writing Guide

- Interview Preparation Guide

- Interview Questions Database

- Financial Assistance

Copyright AcceptedTogether Inc. © 2023. All rights reserved.

YOUR PATH TO SUCCESS STARTS HERE

Find a dedicated consultant to help with applications, personal statements, interviews, Casper, and more!

AMCAS Personal Statement Examples (2024)

by internationalmedicalaid

Why is the AMCAS Personal Statement Important?

Every year, thousands of graduates apply to medical school. Some of them have fantastic GPAs and MCAT scores , others have astounding extracurriculars, shadowing, and volunteering experience, and yet others have both. Yet many of these stellar students who have spent hours doing all this don’t make the cut. Most medical school applicants go through at least 2 or 3 years of applications before getting an acceptance offer from a medical school. Some others do not get accepted even after a couple of rounds and give up their medical school dreams.

What are we missing? How can we tilt this equation and increase the odds of getting in? What are some winning strategies?

Let us put ourselves in the shoes of the people making the decisions and handing out acceptance, rejection, and waitlist letters.

The critical thing to remember is that the admissions committee reviews every candidate qualitatively. This is because while numbers speak for past achievement, the committee is most concerned about future potential: something that may or may not be reflected in those fabulous GPA and MCAT numbers . There are several questions that the committee seeks to find answers to, and one central question is how well a student will fare in their program and beyond.

That brings us to the unknown future. Let us look at some known facts: Even highly successful students will have to give everything they have to thrive in a new environment—one that is much more fast-paced, with varying and several demands, complex challenges, and possible twists and turns that no one can anticipate. At the end of the day, candidates are people. Between fitting the scores and the extracurriculars on the one hand, and the values, perspectives, habits, and attitude of applicants on the other, medical school admissions committees have their work cut out for them.

So they turn to the personal statement. The AMCAS personal statement is one of the tools through which the qualitative review takes place. In a limited personal statement of not more than 5300 characters, including spaces, you get the chance to tell a story that reveals the person you are. It is the only way to tell the admissions committee that you have the conviction, dedication, work ethic, tenacity, and motivation to succeed in medical school and beyond. The AMCAS personal statement provides a window into the unique past of every applicant to showcase future potential.

What do I talk about in the AMCAS Personal Statement?

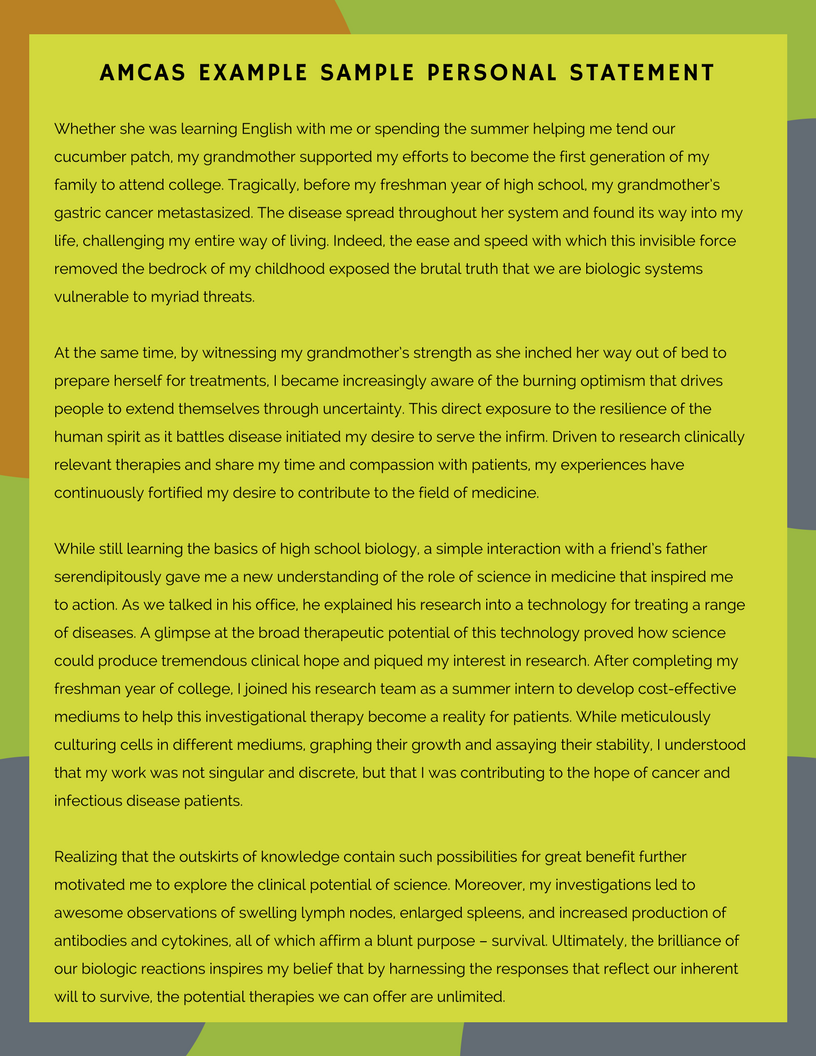

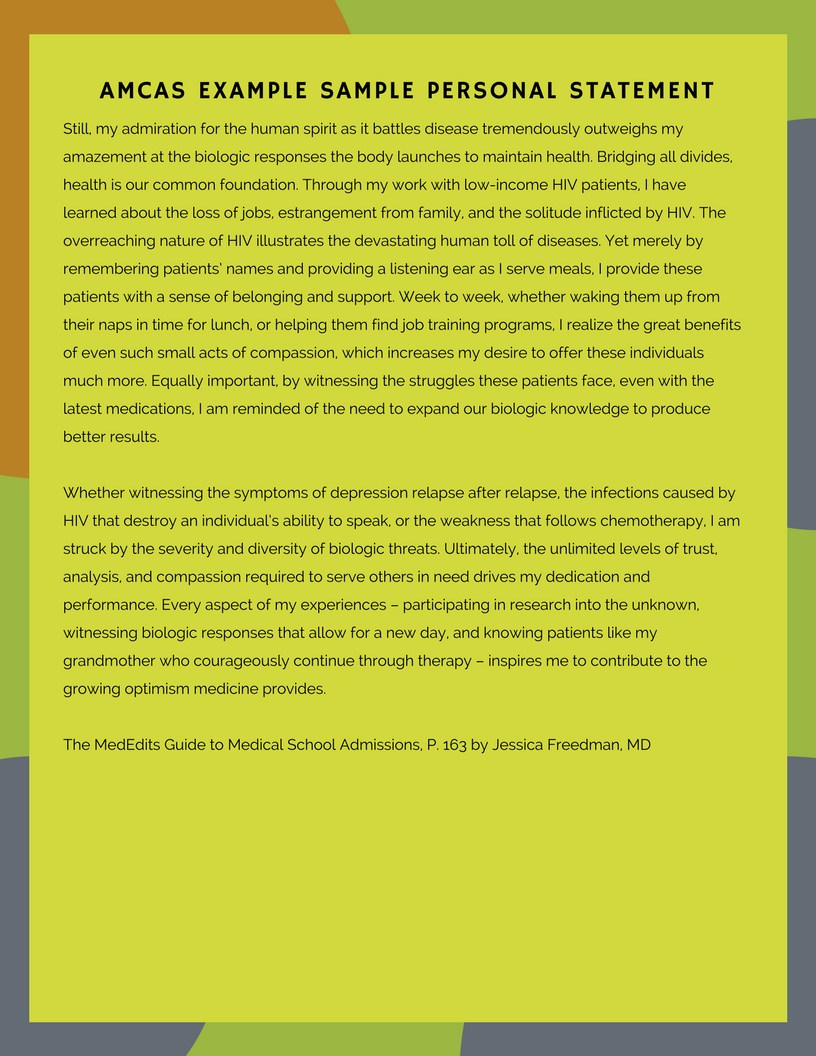

Amcas personal statement sample 1.

Just as every person is unique, each applicant’s personal statement is unique. There is no preferred topic or experience. While the personal statement is anchored around 2 to 3 incidents or life experiences that are personal, the real interest lies in why those incidents are important to the applicant. Let us take an example from an applicant’s AMCAS personal statement:

I grew up in a family where autoimmune diseases were almost synonymous with existence. I watched my diabetic uncle taking two insulin shots each day, avoiding pastries and cakes, and maintaining a stringent routine. I was told that diabetes had afflicted my grandfather as well. At the tender age of 9, when the whole world seemed to be bubbling with opportunities, growth, and promise, I was used to seeing the deterioration in the quality of life that disease can cause.

The strength of this opening statement is that it is deeply personal and suggests that the applicant’s interest in medicine has strong personal roots. Note that it is not necessary to start with clinical or shadowing experience. In some ways, the AMCAS personal statement is a story about your personal quest or self-discovery. Since you are likely to have started your clinical and shadowing work after discovering your career, it is a good idea to start from an earlier point in your life. Even if you start with a clinical experience, tracing back your career interest to an earlier moment is almost a must to give the committee a sense of your journey.

You will also notice that the student continuously connects disease with quality of life (a top concern for patients and doctors alike). Thirdly, the opening remark shows the writer’s concern and empathy which are essential qualities in a doctor.

Let us look at what makes a good personal statement. Like every piece of writing, the AMCAS personal statement has its set of essential ingredients and optional elements. Combined, the two parts should result in a compelling narrative that convinces the school about the applicant’s candidature.

The Essential Components:

Show a key trait or value that is critical to the field: this could be people-centric values such as empathy or helpfulness; it could be more general such as curiosity about life systems, drive to make a difference.

The connection between personal experiences and professional aspirations: The personal statement is a personal account. It seeks to provide personal reasons for pursuing medicine. This indicates that no incident is trivial or significant in and of itself. In AMCAS the personal statement, an event takes on significance in so far as it reveals how it shaped the applicant’s personal journey. Examples of such events could be mundane ones such as:

- Driving through underserved neighborhoods and noticing the lack of health facilities

- Doctor’s visits and becoming curious

- Sitting in a Biology course and being excited about the subject

- Pondering over the effect of sleep on our health and reflecting on daily habits and health

None of these incidents is out of the ordinary. Yet, in the personal statement, they can make a compelling case if presented in the right way. Let us see how the AMCAS personal statement we started with makes such a case:

When I was a freshman in college, I witnessed what hypothyroidism can do to a person. My cousin, who had read so many storybooks to me when I was a kid, loaning her books generously when I became an independent reader myself, was diagnosed with the condition and was severely depressed. Her unaccountable weight gain was baffling, and I sensed she suffered a lot. I was very close to her, and to watch her, after seeing what my uncle had to go through, was to have a déjà vu of how disease can alter a person’s entire lifestyle.

The trait of concern for others’ well-being, which was outlined in the first paragraph, takes center stage here. Also, note the little details about the applicant’s reading interest and the more subtle indication of the writer’s gratitude when she mentions that her cousin had read books to her. The theme of concern for the quality of life is seen again at the end of this paragraph.

So my interest in medicine began when I started to take her little gifts and to spend time chatting with her. Wanting to do more, I started volunteering at the St. Martin Hospital. At first, I helped answer calls. Soon I was allowed to check on supplies and even carry food to patients. Feeling the need to bring a strong scientific perspective to all that I did at the hospital, I selected Biology, Chemistry, and Physics in my sophomore year. I joined with an undeclared major, which gave me the flexibility to explore premed opportunities on campus. As my interest in the health sciences grew, I divided my evenings between volunteering and shadowing doctors.

This paragraph shows a progressive development in the applicant’s interest and the steps she took to address those interests. The key phrase is “a strong scientific perspective” which indicates the applicant’s ability to analyze and identify the most important element in patient care: the science.

The different responsibilities I handled when volunteering and when shadowing showed me the two distinct but complementary sides of medical practice: as a volunteer, I learned to be proactive, to anticipate the needs of patients, nurses, and the administrative staff. Timely help, attention to detail, and working in different departments taught me to be flexible and always alert. I learned that minor tasks were critically important to ensure effective care. As I checked the nutritionist’s instructions on the food tray or ordered a wheelchair for patients, I learned that patient care is at its heart selflessness. Concern for another person’s well-being comes before anything else. The few moments that I had to spare were spent with patients as I chatted with them, talking about their interests, families, the news, or anything else that caught their fancy.

When I shadowed, however, I entered the high realm of diagnostics and treatment. I learned, paying attention to the nuances of the doctor’s analysis of symptoms in the context of family histories, socioeconomic factors, and lifestyle. On the one hand, I learned to see every new case as the latest exemplar that would add to the collective knowledge of doctors. On the other, I realized that medicine called for the ability to creatively connect existing parameters of a known condition with its unique representation in each patient. The dynamic interplay of knowledge, practice, and care enthralled me in the patient rooms every day. Most of the time I was a silent spectator. But occasionally, I would be asked a question to test my knowledge and understanding, and I waited for those moments to learn and to grow.

Once, we were attending a patient who had had angioplasty a few days before and suffered from prolonged discomfort after being discharged. The doctor and nurses were discussing the fluoroscopy footage and possible stent failure. I had been shadowing for over six months by then and the doctor, whom I had shadowed several times, looked at me over the patient’s bed and asked,” Greta, what do you think?” I was stunned and quickly thought of earlier cases of angioplasty that I had seen. Most of the procedures had been successful, and we only saw the patients for routine follow-up. But I knew that tissue scarring was a risk and spluttered, “is it scarring in the stent?” The patient was sent for reassessment and had to go through another angioplasty before we discharged him. Still, I realized that medical decisions call for an incredible amount of attention to detail, knowledge of an arsenal of known causes and treatments, and the ability to determine the exact cause in each case after weighing in patient histories, statistical studies, research findings, and clinical experience.

This paragraph is clearly the most dramatic section of the AMCAS personal statement: The contrast between trivial but critical tasks as a volunteer and the more demanding learning when shadowing doctors is brought out effectively, and the applicant makes it a point to state that she enjoyed both. The second most important anecdote is also in this section of the essay and shows the applicant’s ability to grasp the complex nature of treatments and the various skills required. The ability to handle the menial and the more skilled dimensions of the profession is effectively highlighted here.

As I enter the hospital every day, I look forward to the all-hands-on-deck nature of my job and know that though it is the same place, the day will turn out to be different from every other day I have spent at the hospital. The myriad challenges, the several demands made upon the staff, and the ongoing endeavors to deliver the best for each patient never cease to motivate me. As a cog in a giant wheel, I dive in, and give all I have every day. My understanding of the deep structures of patient care increases every day as I work, study, observe and converse at the hospital. The tremendous efforts in patient care that are always underway at the hospital never cease to enthrall me, and I look forward to making my contribution as a doctor.

This wrap-up brings the essay to the present. The applicant’s interest is indicated in statements such as “the day will turn out to be different from every other day.” The sense of being part of a much larger healthcare system is effectively brought out through the tone of humility as the applicant makes a case for being admitted to medical school.

AMCAS Personal Statement Sample 2

The narrative of self-discovery through a personal journey is just one of several approaches to the AMCAS personal statement. Another popular theme is a description of a trait that is at the core of the health sciences. The sample below illustrates the applicant’s sociability—a general trait that is very useful in medicine.

Even as a child, I liked to be among people. My mother tells me that I did not cry when she left me in playschool at age two though she had hoped I would. I did sulk however, when I was left out of group activities in middle school, I exalted in the company of classmates when we did projects in high school, and I became an unofficial, self-appointed mentor for new students in college. Through all these enjoyable choices, I have become a person who seeks to make the right decisions by speaking with others and who seeks to correct wrong decisions, again by speaking with others.

The opening paragraph immediately tells the reader the kind of person the applicant is. Touches of humor (my mother hoped I would cry) and modesty (‘unofficial self-appointed mentor’) make the writer likable ( a trait that is usually found in sociable people and which would be very helpful in a doctor).

Though I have made straight As in college, the path forward was never clear to me. My counselor told me that the common path after a Chemistry major was a career in pharmaceuticals or manufacturing. An emerging field was computational Chemistry which would leverage my proficiency in math as well, she enthused. As I read about these fields, each of them as exciting as the other, I started to have some doubts. The idea of spending 40 years in a lab, on a factory floor, or in front of a computer was none too appealing and I had serious questions, bordering on existential angst, about what I would do with my major.

The light vein continues into the second paragraph as the writer talks about his dilemma (“what I would do with my major) even as he deftly rules out options that show clearly that he has gone through some reflection before choosing medicine. The oblique philosophical touch in ‘existential angst’ is also lighthearted though it also captures the student’s dilemma.

It took me some time to realize why I did not warm up to the options the excellent career counselor laid forth for me. I would miss people. I could not work with machines and chemicals in a way that would erode human contact. I would miss the fun people have when thrown together.

The case for medicine is made through the writer’s people-centric world. That he has fun with people shows his aptitude for a highly interactive profession like medicine.

And so it was that one day in my third year, resume in hand, I found myself signing up for shadowing at Elliot Hospital near home. On the first day, I expected the staff to show me the pharmacy; I expected questions about why I did not pursue biology if I wanted to be a doctor. I had prepared myself with several friendly and polite rebuttals: I liked biochemistry a lot but did not like research labs or detergent companies. Armed with that and a fervent prayer, I approached the front desk. Strangely, not a single question was asked about how I fitted, nor was I shown the way to the medicine cabinets. Nurses ushered me into the emergency room, gave me a quick rundown on systolic and diastolic and CPR, and had me help out in bandaging and talking to patients. Every day I would be absorbed into the day’s most urgent tasks. Those were also the days when I spent the most time speaking with patients. I remember Jake, a 50-year-old patient whose appendicitis was causing him a lot of pain. His surgery was scheduled that week, and he had to go through several pre-op tests. As I helped him, I could sense his nervousness which he tried her best to hide. Distracting him while at the same time making sure he completed all the tests showed me the importance of sensitivity and multitasking in patient care. Most of my conversations with patients were about neutral things like news or the neighborhood. I found that intelligent conversations about normal things always made patients feel normal as well. On less busy days, I went around the hospital, looking at the several departments, patient rooms, nurse stations, and doctors’ offices.

After two weeks, encouraged by the staff’s ready acceptance, I ventured into the pharmacy during lunch break. I was thrilled when I found that I understood prescriptions and labels on IV due to my foundational Chemistry courses.

This paragraph emphasizes the writer’s sense of being at home in a hospital—a key detail that will show the admissions committee that he enjoys being in the hospital. His curiosity is also seen in phrases like ‘went around the hospital’. His sensitivity to people’s fears is also captured effectively. Notice also the connections made between a major in Chemistry and medicine. The following paragraph reinforces this further.

When I returned for the next weekend, I felt as if medicine was a common path for Chemistry majors. How else could I explain my ability to understand lab reports so quickly and understand exactly why the doctor was prescribing the medicine that she was? I shadowed every weekend for the rest of the year, got to know most of the staff, was invited when some of them went out, learned about their personal lives and their passion for medicine.

It is not obvious, but this paragraph resolves the central dilemma of what the student wants to do with his major by emphatically stating that medicine is a common path for Chemistry majors. A sense of belonging is effectively built here as the student talks about spending time outside work with the staff.

The time with them taught me that medical professionals love what they do for the same reasons I want to love what I do: being with and helping people. For the hospital staff, work and life were not separate things, and this was not because there was no work-life balance, but rather because their social community was their professional community and because they all shared a common feeling that they could not do enough to help patients. I realized that it did not matter what role you played. In medicine, the most trivial task is as important as the most important one. A simple and small oversight can have drastic consequences that can have a cascading effect. As a result, everyone depended on each other, and this led to the very high level of trust that I experienced myself on my first day.

The applicant addresses a key presupposition about the medical field: the lack of a work-life balance and argues that through shared interests, the boundaries between work and life fade for medical professionals. The applicant also brings up the central element of trust amongst the hospital staff, a point that is all the more authentic because he himself was entrusted with tasks on his very first day.

Luckily, I have found the pathway to professional and personal happiness in medicine. I hope to help patients discover similar pathways to health through medical treatment, trust and communication, paths made possible only when people are thrown together and make decisions by pooling in their collective expertise and skills.

The importance of collective efforts in medical treatment is matched with the writer’s skills with working with people to construct an image of medicine and of medical practitioners through the high level of social interaction that takes place in healthcare.

AMCAS Personal Statement Sample 3

An equally popular theme for the AMCAS personal statement is the applicant’s personal experience as a patient. The example below uses the applicant’s experience on the patient’s side of healthcare to show how his interest in medicine developed.

When I was assessed as being overweight, I started to run a little daily to slim down. I hated having to do what was a meaningless, monotonous chore, especially since I did not see my friends having to undergo similar tribulations. The doctor’s diagnosis was clear: There was no underlying condition, so it was just genetic. That was both bad and good, medically and socially. It meant that I was born with it, and so, no matter what I did to stay slim, I could always go back to being fat. But it also meant that through a prescribed routine, I could fight obesity to be socially accepted.

The basic understanding of genetics and physiology is established here through a highly personal narrative.

Social acceptance was important to me. I led a community band whose highly popular performances meant that every member was a part of an informal fan club. The popularity of our performance made us conscious of our physical appearance, which mattered to our fans. Though I had been gaining some inches for a few months, people had started noticing it lately. Since the prospect of being seen as ‘obese’ hung over me like Damocles’ sword, running had become mandatory.

This paragraph and the next establish the writer’s interest in books. One example alludes to a myth, and the other alludes to a modern novel.

The first week was bad enough. I ran all of 10 minutes every day on the same route from my dorm to the library. Rather like Papillon, I knew by heart every stone, every pillar that I crossed daily. It dawned on me that I would indeed start numbering and naming those new landmarks and so I changed my route. The fresh path brought fresh vigor despite being longer and I started running for 15 minutes, without really minding it. In a few months, I had become a familiar figure on campus, jogging shoes and headphones, a slightly slimmer body and a higher self-esteem in between. I was clocking one hour daily after six months.

The subtle connection between health and self-esteem is made here and will be developed further in the later part of the essay.

Social acceptance and medical treatment are so frequently linked yet so rarely talked about. Only in extreme cases, such as when a patient has to be hospitalized, do we think of social life as something that is affected by the need for medical care. As I jogged daily to maintain my weight, I asked do we see patients as people and people as patients? Yet that is what they are. As a person, I wanted social acceptance, and as a ‘patient’, I wanted a cure for what could only be managed. I realized that doctors do much more than just hand out prescriptions. They enable the social acceptance of patients, allowing them to lead normal lives. They prevent any impairment to the dignity of human life whenever they can. It is this central place of medical treatment in everyday social life that draws me to medicine as a profession.

This paragraph is the centerpiece of the essay: it is the writer’s own definition of what it is to be a doctor. It also shows his passion and vision as a future medical practitioner.

The subtle and strong mechanism of ongoing treatment to help people maintain a normal routine drew me to medicine. As a doctor, I hope to touch people’s lives through effective patient care. I realize that this would be the work of a team of experts who would look into mental health, nutrition, environment, and socioeconomic background. Through ongoing treatment and consultation, people’s lives are enhanced in innumerable ways. The right intervention at the right time has the power to transform what a person is capable of.

I discovered this at Radcliffe Hospital where I volunteered when I met Martha, a 70-year-old patient with severe rheumatoid arthritis. Psychotherapeutic treatment and physical exercises were essential for Martha to help her retain her mobility in the range required for everyday activities. Between her cortisone shots to fight the inflammation and repeated anti-CCP tests, and through her exercises and therapeutic sessions, she managed to find the agility and time to take her grandkids to Disney Park, knit sweaters for herself and her husband, and cook almost every day. Though I found that patients like Martha always looked at their visits to the hospitals as necessary but not enjoyable, when they left with the prescription or with the doctor’s reassurance, their smiling faces showed that their confidence was restored. And that they were ready for yet another phase of normal social life. Restoring happiness by restoring normalcy is the magic of healthcare.

The anecdote of Marth’s rheumatoid arthritis underscores the theme of medicine as a tool for having normal lives–a very compelling and unique argument.

I was also aware that there are people who do not have access to these timely interventions. Perhaps the most significant class difference in society is not between the haves and the have-nots, but rather between those who have easy access to healthcare and those who don’t because healthcare increases our chance at a normal life.

The connections between healthcare and demographics is brought out here.

I can cover 7 miles with ease today, and the scales say that my weight is within range. As I continue jogging, I have my eyes set on the half marathon; the 13 odd miles run reserved for the well-initiated. The training is teaching me the art of goal setting, finding the optimal pace, and staying focused. There are other payoffs as well: fitness, alertness, and most important of all, self-esteem. The treatment has become an expedition, a quest that has transformed me. Is it my persistence that is paying off? Or do I owe it to my doctor, whose accurate and timely diagnosis set me on a path to increased social acceptance, human dignity and a normal social life? As a doctor, I hope to achieve similar transformations in my patients: prescribing the right treatment at the right time and working with them to enable long-range health and happiness.

The paragraph rounds off the essay with a strong statement of personal achievement (the half marathon) and the promise of medicine as enabling normality. By indicating his achievements through persistence, the writer is also stating that he will be as persistent and achieve success in medical school.

AMCAS Personal Statement Sample 4

The curiosity essay works well for the AMCAS personal statement. The following example combines the writer’s increasing curiosity about life sciences with the need to fight gender stereotypes as a female science student.

In a classic case of reverse psychology, I tended to pursue the hard sciences in high school, an area that I was told would be dominated by men. Somehow, the laws of nature fascinated me, but the stereotype that “normal” girls did not pursue science led to varying reactions amongst my friends, ranging from awkward silence whenever I discussed science to outright avoidance by the all-boys science majors. Yet the mysteries of the universe and the scientific explanations for several of them enthralled me.

In college, I had the opportunity to understand the nature and properties of the things around us: by measuring the heat capacity of water, I understood why the seas don’t heat up as quickly as the sand on the beach; by exploring the ability of light to accelerate certain chemical reactions, I understood the reasoning behind the instructions on pickle bottles that ask us to keep them out of sunlight. The incredible satisfaction I felt when an experiment succeeded fed my fascination. At the same time, the rigor of scientific methods made me realize that it was very important to be thorough and exact in my experiments, observations, and conclusions.

After describing the natural curiosity in detail, the essay shows how that curiosity changed into a sense of urgency which the applicant is alert to when attending to patients. Notice key phrases such as ‘saving lives’ and’ passion’ which indicate this transformation.

That fascination took on a sense of urgency when I witnessed reports from bloodwork for patients at Amity Hospital. As a volunteer, I was not allowed to even touch the hypodermic needles, much less the surgical scalpel that nurses and surgeons wielded with such dexterity. Yet the connections between saving lives and scientific processes showed me my true calling: medicine. As my own interest took shape, I started to actively seek opportunities in the hospital’s small dementia ward. Short-term hospitalizations for dementia were peaking, and there was a need for additional help, so I could find plenty of ways to work in the ward. Simultaneously, I picked advanced electives in neurological science in college, and the shuttling between my academic work and my volunteer work became the perfect way to explore my new passion.

The next paragraph takes up the example of Brad, a dementia patient. The anecdote is told in a way that only a close observer or volunteer can.

But it was not until I helped Brad, a vigorous octogenarian who suffered from dementia that I realized the importance of medicine today. Brad had started misplacing things when going through an emotionally stressful period of his life when his wife had passed away. But the forgetfulness had stayed. Even after a year, he forgot to take the keys out of the front door, left the stove on, and even forgot to walk his dog sometimes. His treatment included a strict diet to reduce his cholesterol and daily exercise–his neighbors were keeping a tab on his activities. We assessed his progress every six weeks, but his sometimes risky behavior was alarming. We also saw symptoms of sundowning as he sometimes wandered off during his visits and had to be brought back.

In the next two paragraphs of the AMCAS personal statement, the importance of hope and ongoing care despite critical gaps and hurdles and even in deteriorating patients brings out the passion for medicine.

I returned to my coursework in Neurology and Cognition every day after watching Brad for over four months, and as I tried to incorporate the demographic elements that require attention in any treatment in my academic work, I realized that with an aging population, neuroscience faces increasing challenges in improving our understanding of memory, recognition, and cognition. Yet, thankfully, age is not the only factor, and there were means to slow down the disease for certain individuals. I hoped that Brad would be in that group.

But there were others who were beyond help and had to be kept from harm. For these inpatients, independent living was rapidly becoming a dream, and they could not even be discharged with some assistive technology to help them remember or do the right things. As we struggled to deliver care, the gaps in the information we needed, in the research that depended on that information, and in the treatment plans were reminders of the limitations we faced. However, we tried our best to do what we could to help patients.

The shift from curiosity to the personalization of treatment is a key shift in this essay’s theme. It is central to the argument that the applicant is convinced that medicine is the best career option for her.

The ability of science and scientific research to improve life draws me to medicine. But it is not just the science, or just the research. The personalization of treatment by knowing patients closely and monitoring their health over time will be the greatest challenge and will bring the greatest reward. That is what fascinates me most about medical practice: the tweaking of an earlier prescription, a change in treatment or even the protocol, the keen interest in patient wellness–these ongoing and tireless efforts by doctors, nurses, and surgeons validate the science. I feel particularly thrilled when the doctor makes a change in the treatment plan because a patient shows signs of improvement. In common approaches to mental health, all we have are signs and symptoms that show us an underlying improvement or deterioration.

As I continue my coursework and volunteering, I have become keenly aware of the need for customized and nuanced treatment plans. Our scientific foundation is one of several elements that impact total patient outcome; the others are ongoing monitoring and understanding each patient’s unique circumstances, lifestyle, and habits. As a future neurologist, I will bring this passion for understanding patients and for personalizing the science to each individual’s needs to my practice.

AMCAS Personal Statement Sample 5

The dilemma personal statement is rarer and perhaps harder to pull off. But when done right, it can really make an applicant stand out. The applicant is torn between engineering and medicine in the beginning.

Wheeling patients in and out of their rooms at Dr. Faruk’s clinic did not strike me as an activity that would end in an epiphany, but that is exactly how my daily routine ended one day.

As a high school student, I had gravitated towards the physical and life sciences equally. However, I was in a quandary about which stream within the sciences would be my calling. On the one hand, Physics and Mathematics were compelling examples of the transformative power of engineering. On the other, the personal interest that is involved in patient care drew me to medicine.

The interim compromise through a major in Biotechnology is described next.

To continue to understand my options, I chose Biotechnology as my undergraduate major. For many, the sub-specialties of the field were sufficient pointers to what they wanted to do. For some, research careers in biotech labs were attractive. For others, medical equipment design and manufacturing became the area they sought expertise in. I, however, continued to be divided. After classes in Bioinformatics, Medical Devices, Cell and Molecular Engineering, I spent my evenings volunteering and shadowing at various hospitals, hoping that through these experiences, I would understand what interested me the most.

The quest for the right field shows the applicant as one who perseveres to find what he wants to do.

As I continued to explore options, I realized that what I was looking for were intersections between the several sciences. However, it was as if engineering and medicine were on the opposite sides of my chessboard, with no overlap. My quest for intersections left me without a solid plan for my own future as I vacillated between the choices available to me.

The epiphany that resolves the dilemma mentioned earlier is described next.

Almost as a last resort, I started volunteering at Dr. Faruk’s family medicine practice. Little did I realize that my interactions with patients and with him would help crystallize my aspirations while helping me reflect on my own preferences. Working in the patient transportation department, I accidentally discovered the intersections that I had been looking for. How does mobility–a physical event–improve patient health? This led me to further questions that related to Physics as much as to Biology: what does weight have to do with the prognosis of type 2 diabetes? How much can advances in computer science improve our ability to screen and diagnose medical conditions?

I realized that both computer science and the health sciences advance through synergies, and this made my need to choose a career that much more challenging and interesting. While I was thrilled when I interacted with patients, I was equally astounded by the technological advances that benefit us in so many ways. To gain further insight, I approached Dr. Faruk and asked him for advice. To my surprise, he admitted to having had similar doubts himself. I pressed further, and he explained that he had initially considered a position in engineering. Ultimately, he chose medicine because he was more satisfied when he helped others directly. He urged me to think of my career choice as a deeply personal one not influenced by what others were doing.

The dilemma leads to personal growth as seen below, when the applicant stops seeking answers but rather learns to explore.

What had initially been a feeling of dread at not being able to choose a career changed into an open-minded inquiry into the myriad problems each science seeks to solve. My self-doubts gave way to curiosity–a trait that I had frequently seen in Dr. Faruk himself. While I had previously felt that time was running out and that I had to make a decision quickly, I now took time to reflect and research several areas of science.

The next section answers the key question, “why medicine?” by talking about the personalization of science.

Slowly but surely, I started to spend more time understanding patient conditions, the treatment, the progress and the routine checks. I understood that while the science helped me analyze each patient’s condition, speaking with patients and their families gave deeper insights into how to manage the treatment. I remember in particular Mark, a 40-year-old patient who had to have a kidney stone removed. He was in excruciating pain, and we had to work quickly and refer him to a surgeon. Mark was a security guard at a well-established company that provided comprehensive healthcare to all its employees. As I spoke with him and his wife, I understood the different shifts he worked in, the long commute to work, and his sedentary lifestyle. I understood that patient care has to be holistic and for that, patient communication was vital to understand each patient’s unique situation.

Interestingly, the dilemma is resolved but leads to another smaller dilemma, one that remains unresolved and which shows the applicant’s willingness to continue to explore options.

When I realized that I enjoy interacting with people more than with machines and algorithms, I discovered that my career had to be medicine. To be certain, I tried to imagine the sub-specialty that would sustain my interest for a lifetime–the way family medicine sustained Dr.Faruk. When I asked him how he had made his career decision, I did not realize how powerful his words would be in helping me think through my career. He said, “you’ll just know what feels right, and as time goes on, you may view things differently.”

His words helped me identify my career aspirations and encouraged me to be open-minded to future changes within my career choice. Thanks to Dr. Faruk’s advice, I know that I am making the right choice for the right reasons: I like helping people and making a difference in their lives. What field specifically? I don’t know yet, and I don’t need to know. I’ll view things differently with time, and this will shape my aspirations.

How International Medical Aid Can Help

Providing guides for different aspects of the medical school application process is just one of the many things we do here at IMA. We also offer medical school admissions consulting (including dedicated personal statement reviews) and pre-medicine internships to help you prepare for medical school. Our consulting services mirror that of traditional admissions committees.

Our award-winning Pre-Medicine Internship Programs are like no other, taking you to underserved populations in countries within East Africa, South America and the Caribbean. We are here to help you in any way we can as you progress in your journey to medical school. It’s a long, difficult road, but the passion for medicine makes it all worth it. We’ll be here if you need help on your journey.

While you’re here, check out some of the medical schools we’ve covered here on our blog.

- John A. Burns School of Medicine (JABSOM)

- Kansas College of Osteopathic Medicine (KansasCOM)

- UC Irvine School of Medicine

- Nova Southeastern University College of Allopathic Medicine

- Florida Atlantic University Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine

- Touro University Nevada College of Osteopathic Medicine

- University of Miami Miller School of Medicine

- Arkansas College of Osteopathic Medicine (ARCOM)

- University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS)

- Tulane University School of Medicine

- LSU Health New Orleans School of Medicine

- LSU Shreveport Medical School

- Kirk Kerkorian School of Medicine at UNLV

- University of Nevada Reno School of Medicine

- University of Arizona College of Medicine-Tucson

- University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix

- Burrell College of Osteopathic Medicine (BCOM)

- The University of New Mexico School of Medicine

- Alabama College of Osteopathic Medicine (ACOM)

- University of South Alabama College of Medicine

- University of Alabama School of Medicine

- FIU College of Medicine

- UCF College of Medicine

- USF Morsani College of Medicine

- Florida State University College of Medicine

- Morehouse School of Medicine

- Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University

- Mercer University School of Medicine (MUSM)

- Campbell University School of Osteopathic Medicine (CUSOM)

- ECU Brody School of Medicine

- Edward Via College of Osteopathic Medicine (VCOM)

- University of South Carolina Medical School

- Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC)

- Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University

- Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine (PCOM)

- Geisinger Commonwealth School of Medicine (GCSOM)

- Penn State Medical School

- CUNY School of Medicine

- SUNY Downstate Medical School

- NYIT College of Osteopathic Medicine

- NYU Long Island School of Medicine

- TOURO College of Osteopathic Medicine

- Albany Medical College

- Norton College of Medicine at Upstate Medical University

- Jacobs School of Medicine at the University at Buffalo

- Hofstra Zucker School of Medicine

- Weill Medical College of Cornell University

- University of Rochester Medical School

- Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai

- Renaissance School of Medicine at Stony Brook University

- Albert Einstein College of Medicine

- Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine

- Northeast Ohio Medical University (NEOMED)

- University of Cincinnati College of Medicine

- University of Toledo College of Medicine

- Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine

- Ohio State University College of Medicine

- Rowan University School of Osteopathic Medicine

- Hackensack Meridian School of Medicine (HMSOM )

- Rutgers New Jersey Medical School (NJMS)

- Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School

- Cooper Medical School of Rowan University (CMSRU)

- A.T. Still University Kirksville College of Osteopathic Medicine

- Saint Louis University School of Medicine

- University of Missouri Medical School

- Kansas City University (KCU)

- UMKC School of Medicine

- New York Medical College

- University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

- University of Wisconsin Medical School

- VCU School of Medicine

- University of Maryland School of Medicine

- Case Western Medical School

- University of North Carolina Medical School

- University of Florida Medical School

- Emory University School of Medicine

- Boston University College of Medicine

- California University of Science and Medicine

- UC San Diego Medical School

- California Northstate University College of Medicine

- Touro University of California

- CHSU College of Osteopathic Medicine

- UC Davis School of Medicine

- Harvard Medical School

- UC Riverside School of Medicine

- USC Keck School of Medicine

- UT Southwestern Medical School

- Long School of Medicine at UT Health San Antonio

- University of the Incarnate Word School of Osteopathic Medicine

- UT Austin’s Dell Medical School

- UTMB School of Medicine

- McGovern Medical School at UT Health

- Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

- The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley School of Medicine

- UNT Texas College of Osteopathic Medicine

- University of Houston College of Medicine

- Texas A&M College of Medicine

- Johns Hopkins Medical School

- Baylor College of Medicine

- George Washington University School of Medicine

- Vanderbilt University School of Medicine

- St. George’s University School of Medicine

- Lake Erie College of Osteopathic Medicine (in Pennsylvania)

- Sidney Kimmel Medical College at Thomas Jefferson University

- Wake Forest University School of Medicine

- Western University of Health Sciences (in California)

- Drexel University College of Medicine

- Stritch School of Medicine at Loyola University Chicago

- Georgetown University School of Medicine

- Yale School of Medicine

- Perelman School of Medicine

- UCLA Medical School

- NYU Medical School

- Washington University School of Medicine

- Brown Medical School

Good luck from IMA! We believe in you.

International Medical Aid provides global internship opportunities for students and clinicians who are looking to broaden their horizons and experience healthcare on an international level. These program participants have the unique opportunity to shadow healthcare providers as they treat individuals who live in remote and underserved areas and who don’t have easy access to medical attention. International Medical Aid also provides medical school admissions consulting to individuals applying to medical school and PA school programs. We review primary and secondary applications, offer guidance for personal statements and essays, and conduct mock interviews to prepare you for the admissions committees that will interview you before accepting you into their programs. IMA is here to provide the tools you need to help further your career and expand your opportunities in healthcare.

Related Posts

All Posts

- Admissions Consulting

- DO School Admissions

- Pre-Medicine

Medical School Tuition in the US and Canada in 2024

Medical school tuition is expensive, regardless of what type of medicine you practice or where you attend medical school. We talk about lots of...

- Medical School Guides

20 Best Medical Schools in US

Do you want to earn your medical degree at one of the best medical schools in the country? Your goal is the same as...

8 Tips to Writing an Excellent Diversity Essay

Here at IMA, we believe in writing strong essays. We provide samples in our medical school guides, and we’ve shown you how to write strong personal...

5 Questions To Ask A Medical School Admissions Consultant

Applying to medical school is a complicated process. While there are free resources available, some will still need additional help. That’s where a medical school admissions...

Applying to Medical School with AMCAS: The Definitive Guide (2024)

Part 1: Introduction If you’re applying to medical school, chances are you’ve heard a lot of terms (like AMCAS) that you don’t understand. Like...

- Internships Abroad

5 Things I Wish I Knew Before Starting Medical School

Knowing in your heart that you want to go to medical school and become a doctor isn’t an easy process. But once you make...

Take the Next Step

- Medical School Application

Medical School Personal Statement Examples That Got 6 Acceptances

Featured Admissions Expert: Dr. Monica Taneja, MD

These 30 exemplary medical school personal statement examples come from our students who enrolled in one of our application review programs. Most of these examples led to multiple acceptance for our students. For instance, the first example got our student accepted into SIX medical schools. Here's what you'll find in this article: We'll first go over 30 medical school personal statement samples, then we'll provide you a step-by-step guide for composing your own outstanding statement from scratch. If you follow this strategy, you're going to have a stellar statement whether you apply to the most competitive or the easiest medical schools to get into .

>> Want us to help you get accepted? Schedule a free strategy call here . <<

Listen to the blog!

Article Contents 36 min read

Stellar medical school personal statement examples that got multiple acceptances, medical school personal statement example #1.

I made my way to Hillary’s house after hearing about her alcoholic father’s incarceration. Seeing her tearfulness and at a loss for words, I took her hand and held it, hoping to make things more bearable. She squeezed back gently in reply, “thank you.” My silent gesture seemed to confer a soundless message of comfort, encouragement and support.

Through mentoring, I have developed meaningful relationships with individuals of all ages, including seven-year-old Hillary. Many of my mentees come from disadvantaged backgrounds; working with them has challenged me to become more understanding and compassionate. Although Hillary was not able to control her father’s alcoholism and I had no immediate solution to her problems, I felt truly fortunate to be able to comfort her with my presence. Though not always tangible, my small victories, such as the support I offered Hillary, hold great personal meaning. Similarly, medicine encompasses more than an understanding of tangible entities such as the science of disease and treatment—to be an excellent physician requires empathy, dedication, curiosity and love of problem solving. These are skills I have developed through my experiences both teaching and shadowing inspiring physicians.

Medicine encompasses more than hard science. My experience as a teaching assistant nurtured my passion for medicine; I found that helping students required more than knowledge of organic chemistry. Rather, I was only able to address their difficulties when I sought out their underlying fears and feelings. One student, Azra, struggled despite regularly attending office hours. She approached me, asking for help. As we worked together, I noticed that her frustration stemmed from how intimidated she was by problems. I helped her by listening to her as a fellow student and normalizing her struggles. “I remember doing badly on my first organic chem test, despite studying really hard,” I said to Azra while working on a problem. “Really? You’re a TA, shouldn’t you be perfect?” I looked up and explained that I had improved my grades through hard work. I could tell she instantly felt more hopeful, she said, “If you could do it, then I can too!” When she passed, receiving a B+;I felt as if I had passed too. That B+ meant so much: it was a tangible result of Azra’s hard work, but it was also symbol of our dedication to one another and the bond we forged working together.

My passion for teaching others and sharing knowledge emanates from my curiosity and love for learning. My shadowing experiences in particular have stimulated my curiosity and desire to learn more about the world around me. How does platelet rich plasma stimulate tissue growth? How does diabetes affect the proximal convoluted tubule? My questions never stopped. I wanted to know everything and it felt very satisfying to apply my knowledge to clinical problems.

Shadowing physicians further taught me that medicine not only fuels my curiosity; it also challenges my problem solving skills. I enjoy the connections found in medicine, how things learned in one area can aid in coming up with a solution in another. For instance, while shadowing Dr. Steel I was asked, “What causes varicose veins and what are the complications?” I thought to myself, what could it be? I knew that veins have valves and thought back to my shadowing experience with Dr. Smith in the operating room. She had amputated a patient’s foot due to ulcers obstructing the venous circulation. I replied, “veins have valves and valve problems could lead to ulcers.” Dr. Steel smiled, “you’re right, but it doesn’t end there!” Medicine is not disconnected; it is not about interventional cardiology or orthopedic surgery. In fact, medicine is intertwined and collaborative. The ability to gather knowledge from many specialties and put seemingly distinct concepts together to form a coherent picture truly attracts me to medicine.