Digital Learning

How childhood has changed (and how that impacts education), by jeffrey r. young jul 11, 2017.

Vasilyev Alexandr / Shutterstock

It’s easy to forget that notions of childhood have changed radically over the years—and not all for the better, says Steven Mintz, a history professor at the University of Texas at Austin. “Helicopter parenting” and habits around carefully guarding, protecting and scheduling kids have their downsides.

The history of the American family and childhood is an area Mintz has long studied. And he keeps that perspective in mind as he works to keep college teaching practices up to date in his other role, as the executive director of the University of Texas System’s Institute for Transformational Learning.

EdSurge sat down with Mintz a few months ago to talk about kids today, and about why he thinks higher education is going through a once-in-a-generational transformation to respond to how they’ve changed.

The conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity. We encourage you to listen to a complete version below, or on iTunes (or your favorite podcast app).

EdSurge: You’re a historian and still a history professor, in addition to your other duties. And you’ve written acclaimed books about how childhood has changed over the years. What do you think about that changing view of adolescence, and how has that affected the student experience at college?

Mintz: We often think of the history of childhood as the history of its liberation, that is, the kids in the past were servants, or they were apprentices, and that their lives were really regimented. If you were female, you spent your childhood spinning thread or doing menial chores. If you were a boy, you worked in a factory, or you worked in a shop.

We think how much better off kids are today. Abraham Lincoln said that when he was a boy, he was a slave. He was a slave to his father and that it’s not surprising that when his father was dying, Abraham Lincoln made no effort to reach out to him.

But I would at least suggest to you that the story is more ambiguous than a story of liberation. Children and adolescents have much less free, unstructured, unsupervised time than their predecessors did. Parents are putting their kids much more into adult-structured, adult-supervised activities than they did in the past. The geographical range of childhood and youth has contracted over time.

Geographical meaning the landscape they get to play on?

Right, and to ride their bicycle on. A great irony is when we required bicycle helmets, fewer kids were willing to bicycle, because they didn’t want to look like jerks.

Kids spend more time [today] on a screen or more time shopping than they do in what we used to call childhood, which was free, unstructured, outdoor play. That’s a loss, and it’s made it harder for kids to cut the umbilical cord. It’s made it harder to establish an independent identity. It’s made it harder for kids to chart an independent path in life. Sure, it is way better to have a close, intimate relationship with a parent, though I suspect it’s better for the parents than it is for the kids. But it has a cost. One of the values of history is to reject crude, linear notions of progress and to see life really as it is as a much more complicated, ambivalent story.

I think that’s a challenge to parents of young kids—like myself. But it’s hard, right, because there aren’t ... I don’t know. How do you fix that, or what is to be done? Because some of it is changes in density of populations or people’s perceptions of safety. I don’t know.

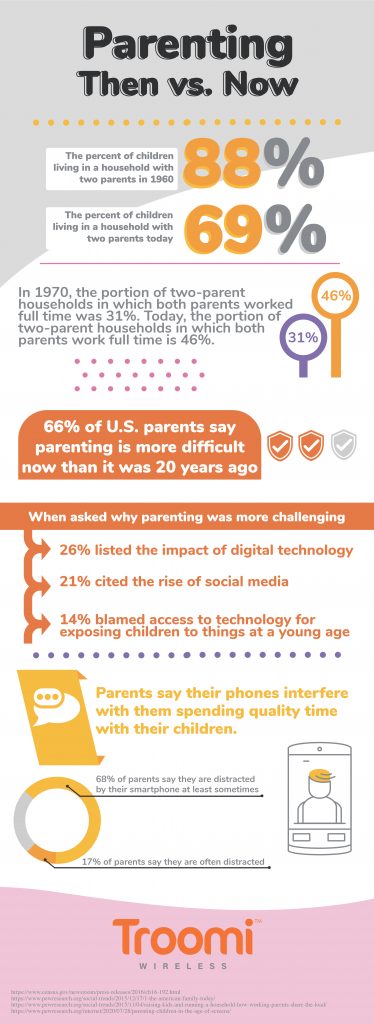

There are structural reasons for why parenting has changed: the decline in birth rates, the growing fear of crime and sexual abuse, what I call the “discovery of risk,” that is, the worry on the part of parents that almost anything can cause some irreparable accident. The fact that parents have fewer children, and that they’re older and better educated, makes them much more sensitive than in the past to the risks and challenges that young people face.

We live in a more psychologized society. We’re way more sensitive to children’s inner states. In many ways, that’s a good thing, but it’s not an unvarnished good. It is not easy to be a parent today. It’s extremely stressful, all complicated by the fact that we have many more single parents and many more dual-worker families, so that there are time stresses that didn’t exist in quite the same way as in the past.

The great challenge for parents is to do the hardest thing of all, and that is to grant your child the freedom to be a child. We have largely rejected the notion of age-appropriate learning—that one day you don’t know how to multiply and then, suddenly, you do. It’s not because the teacher got better. It’s not because you made them read a book or listen to a tape recording. It’s because they grew, and their brain capacity developed.

So they’re ready for it then.

Exactly, and this challenge to let your child take risks and grow and achieve freedom and confidence on their own. That is the hardest thing for parents who are part of a culture of control.

And it probably affects the professor’s role too, by the time children get to college.

For many professors—and I would include myself in this—for 20 odd years, you sat and you listened to lectures, and now it is your turn to lecture. The most important thing that teachers can do, I am convinced, is to treat their students as partners and as creators of knowledge. In other words, to relinquish a little bit of the control of the classroom. Think of yourself as a learning architect, but not as a sage on the stage. Let your students construct knowledge, let them discover insights on their own. It is not easy to do, but that’s how people learn.

You’ve been working on a project at UT Austin called the TEX platform, which is the Total Educational Experience. Can you tell us a little bit about what that is?

TEX is several things at once. First of all, it’s a digital-learning environment that is much more commercial grade, much more immersive, much more interactive than today’s existing learning management systems.

Secondly, it is a system for collecting fine-grained learning data about student performance—that is pace, performance, engagement, persistence and the like. It also has the capability of incorporating information from the student information system, so it can tie student performance data to student profile data—and therefore, allow us to make recommendations, to personalize learning trajectories and to generally improve the educational experience.

Third, TEX is part of a larger educational marketplace. We’re trying to create a platform where multiple institutions can offer courses, and we can provide recommendations so students can develop credentials over time that will help them in the job market.

These are credentials, not the bachelor’s degree, meaning smaller pieces that students can collect even if they’re at different institutions?

Correct. Now, some of these will be degrees, but many of them will be the alternate certifications, like microcredentials or badges and the like. Some will be competencies. We’re extremely interested in the specific knowledge, skills, abilities and capabilities that students acquire through various learning experiences, whether they’re training experiences—like in the military or corporate [world]—or whether they’re academic experiences that take place in a classroom or online.

Give me an example of one or two of those credentials that I might find in your marketplace.

We’re working right now with Army University to try to create what we call a “knowledge graph.” That is, what are the specific skills and knowledge that people acquire in military training programs? This will allow our campuses to award college credit for the skills and competencies that people acquire in the military. Right now, you could be working in nuclear physics in the military, learning a great deal, and find it extremely difficult to transfer that for credit hours. We need to make that simpler. We need to make that more seamless.

In your credentials marketplace, how does someone prove competency?

In our prototype programs, we’re working with standard-setting organizations in the industry and with assessment specialists, like the Council on Aid for Education, to develop sophisticated project-based assessments that really demonstrate what a student can do with their knowledge.

This is not a multiple-choice test?

Correct. Now, most of the areas that we’re working in right now have accrediting exams or licensing exams, like nursing or the MCATs. And so we need to know that students are acquiring the skills that will allow them to succeed in those domains.

Would it be harder in art history or my own discipline of history? Of course it would be more difficult, but large numbers of students are trying to earn job-related credentials and we need to help them do that. If you ask students what is the most valuable part of their college experience, they’re generally going to talk about their co-curricular or extracurricular activities.

That’s a fancy way of saying clubs, parties, frats or whatever it is, right?

Or internships, study abroad, service learning activities or independent research, which is not well-integrated into the college experience. In other words, it’s the active learning experiences that mean the most to students—not the lectures that they sat through or even the seminars that they sat through or even the books that they read independently.

Does your platform capture some of these extracurriculars?

Well, my view is that too often, even today, after all the talk about the learning sciences, many of our classes consist largely of midterms and a final and maybe a paper. That means that a student will respond rationally. They’re going to cram. In other words, they’re going to devote a lot of energy in a very short time, meaning that they have a lot of free time the rest of the semester, time that they could devote to work, or time they can devote to partying or just socializing.

We need to rethink that academic experience. We want to integrate the co-curricular with the curricular. We want to have the educational experience be more immersive, more engaging than it currently is, more all around the student. That way, I think learning will be more intense, learning will be deeper, learning will be richer and it will benefit in a whole variety of ways—including counteracting some of the negative social aspects of the current college experience.

That’s interesting. You think that some of the binge drinking is actually about not enough academic demands to keep students from that?

It’s not just a question of demands are bigger, but it’s that if you don’t feel immersed in your studies, if you don’t find them fulfilling and meaningful and engaging, then you’re going to find fulfillment and meaning and engagement elsewhere, and sometimes not in the areas we’d most appreciate.

The real issues here are bigger than just a digital tool, I guess.

I am a technophile, and I do believe that technology can serve some really valuable roles in a student’s education. I am a great advocate of simulations. For one of my history classes, we created a simulation where you have to sail from Spain to the New World and back using wind and ocean current information. In other words, be Columbus for a moment and try to sail across the Atlantic and see how hard it is to do. We’re creating virtual laboratories. We’re trying to create powerful social experiences online. You and I have powerful social experiences all the time, often mediated through technology, and we don’t see it a problem.

I’m not calling for a totally technologized educational experience, but let’s take advantage of some of the strengths of technology. For example, one of my colleagues at Columbia University had students create websites on every neighborhood in New York City, collecting oral histories and images and other aspects of material culture.

Many people with ‘academic innovation’ in their titles, like yourself, are in jobs that didn’t exist a few years ago. I’m sensing a little bit of anxiety about whether these jobs will stick around for the long haul. Do you worry that?

In roughly 50-year cycles, since the 1850’s, American higher education has gone through some fundamental transformations. Things like grades or credit hours or departments or 15-week terms are not timeless. They’re not written in stone. They were inventions. We’re in one of those once-in-a-generation moments when higher education is in ferment, and it is our job during this period of flexibility to help create new models. Many of us are in the enviable position of helping to shape the future of public and private higher education. It’s a great opportunity and it’s a great burden at the same time. It’s not forever. We all know that.

But I think when we’re done, you’re going to see some really fundamental changes that are really for the best for our learners. Just wait to see when we have 3D reconstructions of historical sights that you can walk through using your virtual reality goggles. You will have a level of immersion that wasn’t possible in the past. If that can’t bring academics to life, I don’t know what can.

More from EdSurge

Early Learning

Many lack access to quality early education. home visiting programs are bringing it to more families., by emily tate sullivan.

Choosing Wisely: Lessons for Leaders in AI Integration

By wendy mcmahon.

Student Engagement

Is student absenteeism a growing problem at colleges, too, by rebecca koenig.

EdSurge Podcast

‘college for what' high school students want answers before heading to campus, by jeffrey r. young.

Journalism that ignites your curiosity about education.

EdSurge is an editorially independent project of and

- Product Index

- Write for us

- Advertising

FOLLOW EDSURGE

© 2024 All Rights Reserved

Childhood Then Vs Now: Difference Between Kids in 90’s and 2000’s

Every Generation people observe old things and define them in a new way. For every century and generation somewhere down the line people’s childhood memories, things are getting changed. In the olden days, kids used to spend their maximum time with friends outside by playing various types of outdoor games. But in the current generation, kids are spending their highest amount of time in front of gadgets and playing virtual games.

Want to recall all your old memories and know what present generation kids are missing? Then, step into this article and get the full clarity on the difference between Kids in 90’s and 2000’s. By referring to this article you all will definitely memorize your childhood things, funny games, enjoyable time, and many more.

After seeing these 90’s Vs 2000’s differences recreate any of the things that you’d love to do at present with your kids or parents. Okay, let’s dive into the Difference Between Children in then and now!

Difference Between Kids in 90’s and 2000’s

People from 80’s, 90’s to the ones from the 2000’s have seen so many drastic differences in Childhood timings. So, to make them feel their childhood memories again and to educate the ones in 2000’s kids about old fun games, and joyful life let’s take a look at the difference between children in 90’s and 2000’s.

Here we are discussing a few most exciting childhood differences from then to now. So, let’s get started now,

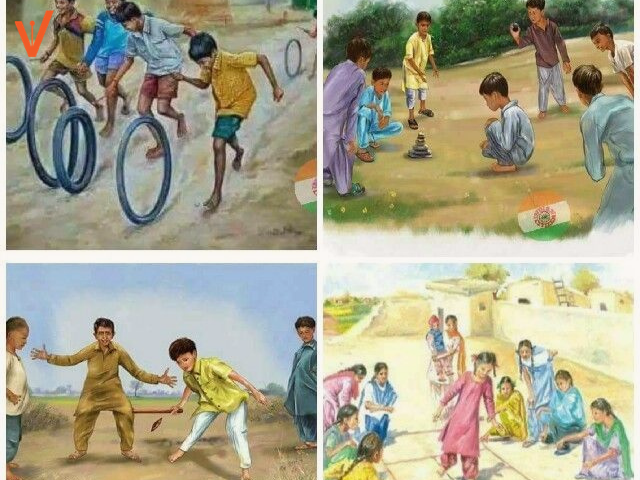

1. Games in 90’s and 2000’s

In 90’s, kids used to play a lot of outdoor games like cricket, shuttle, kho-kho, lock and key, hide and seek, cut the cake, etc. and make joyful memories with their friends.

In 2000s, kids play mobile games like temple run, candy crush, fruit ninja, PUBG, video games, etc. and becoming inactive for other things.

2. Making Class Notes Then and Now

Children in the 90’s always attentive and on point in preparing their notes with pencils/ink pen/gel pen/ballpoint pens/ while classes and study hours.

In 2000s, kids are growing without any correct guidance and becoming addicted to the latest technology and asking their friends to mail the notes instead of preparing on their own before studies.

3. Mobile Phones in 90’s and 2000’s

Those days kids are not even seen phones up to their secondary education and for them holding a mobile phone is big deal.

But nowadays, even months babies are using mobile phones for entertainment, and kids are handling and using them maximum time for playing games, chatting with friends, sharing photos and videos in social media apps, and for studying.

4. Hanging out with Friends Then and Now

At 90’s girls won’t step out from their houses for playing, movies, parties, etc. but boys do step out for playing games only within 500 meters from their houses.

Right in this generation, kids are not even listening to their parent’s words, 10-12-year-old kids are hanging out in malls and go for movies alone without any fear.

5. Birthday Gifts to Friends in 90’s & 2000s

90’s People in their childhood gifted their friends Rs. 11 or Rs. 21 in an envelop or chocolates on their birthdays and wishes them with their heart touching lines, love, and affection.

2000s kids plan their friend’s birthday parties and gift them a minimum 500 cost of branded items or accessories.

6. Punishments for 90’s and 2000’s Kids

Whenever kids get punishments for silly mistakes they used to not play with their friends in the evening times after their homework.

In the 2000s, parents punishing their kids by banning the use of mobile gadgets, tablets, PlayStation, and Xbox for 2 days.

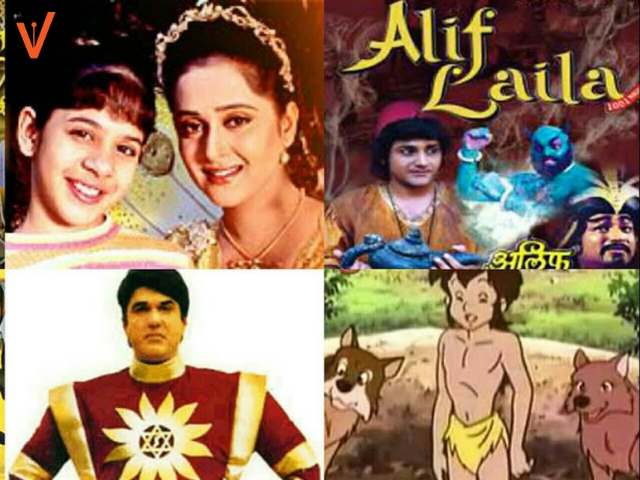

7. Movies From Then to Now

At times of the 90’s, kids are watch movies rarely and then only went for their favorite actors or actress movies like Tollywood actors: NTR, ANR, Chiranjeevi, Bala Krishna, Bollywood Actors – Shah rukh khan, Aamir Khan, Salman Khan.

In the 2000’s, kids love to watch all languages movies like English, Telugu, Hindi, Tamil, Kannada, Malayalam. Now, mostly their favourite actors are Jim Carrey, Gerard Butler, Robert Downey Jr., Leonardo DiCaprio, etc.

For more differences between 90’s and 2000s, please go through this video and cherish your childhood things now and encourage your kids to enjoy your childhood things by recreating those things with your kids.

Well, there are plenty of things that are different between kids in 90s and 2000s. Stay tune to our site for more difference between then and now in childhood. Also, We would love to know your feelings and changes that you’ve seen like these at your times via the below comment section. However, you can get many exciting and interesting articles like this on our website Versionweekly.com

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

ReviseSociology

A level sociology revision – education, families, research methods, crime and deviance and more!

How has childhood changed since the 19th century?

How has childhood in the UK changed since the 19th Century, and have these changes been positive?

Table of Contents

Last Updated on October 4, 2023 by Karl Thompson

There have been several changes to the lives of children since the early 19 th century, and we can break these down as follows:

- Work – Policies which regulated and restricted child labour, leading to the eventual exclusion of children from paid work.

- Education – The introduction of compulsory education and the increase in both funding of education and the raising of the school leaving age.

- The Medicalisation of childbirth and early childcare – Rather than high infant mortality rates, the NHS now provides comprehensive maternity and early childcare to mothers and children.

- Legislation has emerged to exclude children from a whole range of potentially harmful and dangerous acts.

- Parents spend more money on children than ever – a range of specialist products and services have emerged and increased which are specifically aimed at children and child development.

- Parents now spend more time with their children , actively engaged with ‘parenting’.

- Child Welfare – The introduction of child protection and welfare legislation, and its expansion into every aspect of child services through recent Safeguarding policies.

- The recent growth of the idea of ‘rights of the child’ has given children more of a voice in society.

Most people see these changes as representing a ‘March of Progress’. They see such changes as gradually improving the lives of children by giving them more protection from the stresses of adult life. It seems that we have moved towards a ‘child centred society’.

However, there are sociologists who point to the downsides of some changes, especially in the last 50 years.

This post mainly adopts a March of Progress perspective, with the critical perspectives dealt with in my other posts on ‘Toxic Childhood’ and ‘Paranoid Parenting’. I wrote this post primarily for students studying the Families and Households option for A-level Sociology.

Childhood in Victorian Times

During the early 19 th Century, many working-class children worked in factories, mines, and mills. They often worked long-hours and in unsafe conditions, which had negative consequences for their health, and could sometimes even result in children suffering injuries or dying at work.

At home, children were also often required to take on adult-work, doing domestic chores and caring for sick relatives.

Social attitudes towards children started to change in the middle of the 19 th century, and childhood gradually came to be seen more as a distinct phase of life, separate from adulthood, with children needing protecting from the hardships of adult life, especially work and provided with more guidance and nurturing through education.

Along with changing attitudes, social policies and specialist institutions emerged which gradually changed the status of children.

The changes below happened over a long period of time. The changes discussed start from the 1830s, with the first factory acts restricting child labour, right up to the present day, with the emergence of the ‘rights of the child’, spearheaded by the United Nations.

A March of Progress?

One perspective on changes to childhood is that children’s lives have generally got better over time, known as the ‘march of progress’ view of childhood.

This is something of a ‘common sense’ interpretation and students should be critical of it!

There were several ‘factories acts’ throughout the 19 th century, which gradually improved the rights of (typically male) workers by limiting working hours, and many of these acts had clauses which banned factories from employing people under certain ages.

The 1833 Factories Act was the first act to restrict child labour – it made it illegal for textile factories to employ children under the age of nine and required factories to provide any children aged 9-13 with at least 12 hours of education a week.

The 1867 Factories Act extended this idea to all factories – this act made it illegal for any factors to employ children under the age of 8 and provide children aged 8-13 with at least 10 hours of education a week.

The 1878 Factories Act placed a total ban on the employment of children under the age of 10, fitting in nicely with the introduction of education policies.

Today, children can only work full-time from the age of 16, and then they must do training with that employment. Full adult working rights only apply from the age of 18.

Government policy in 2023 discourages younger people from taking on full time work because younger people receive lower wages.

The minimum wage by age in the UK IN 2023:

- £5.28 for under 18s.

- £7.49 for 18-21 year olds.

- £10.18 for 21-22 year olds.

- £10.42 for those aged 23 and over.

This means that those under 18 can’t realistically expect to earn enough to survive, and so are effectively not able to be independent. Those aged up to 21 are in a similar position.

These lower wages encourage young people to stay in education for longer, until at least 21.

Children aged 13-15 can work, but there are restrictions on the number of hours and the types of ‘industry’ they can work in. Babysitting is one of the most common jobs for this age group.

The 1870 Education Act introduced Education for all children aged 5-12, although this was voluntary at the time.

In 1880 it became compulsory for all children to attend school aged 5-12, with the responsibility for attendance falling on the Local Education Authorities.

The next century saw the gradual increasing of the school leaving age and increase in funding for education:

- 1918 – The school leaving age raised to 14

- 1944 – school leaving age raised to 15 (also the year of the Tripartite system and massive increase in funding to build new secondary modern schools)

- 1973 – The school leaving age increased to 16.

- 2013 – Children required to remain in education or work with training until 18.

Today the UK government spends almost £100 billion a year on education and employs around 500 000 people in education.

Children are expected to attend school for 13 years, with their attendance and progress monitored intensely during that time.

The scope of education has also increased. The curriculum has broadened to include a wide range of academic and vocational subjects. There is also more of a focus on personal well-being and development.

The Medicalisation of childbirth and early childcare

Rather than high infant and child mortality rates as was the case in the Victorian era, the NHS now provides comprehensive maternity and early childcare to mothers and children.

In the United Kingdom today it is standard for pregnant women to have a dozen ante-natal appointments for health checks and ultrasounds with National Health Services.

After birth, the government expects parents to subject their newborn children to extensive health checks to measure their development.

There are several of these in the first weeks after birth and then:

- A monthly health review up to 6 months.

- Every two months up to 12 months.

- Every three months from there on.

During early reviews experts discuss things such as vaccinations and breastfeeding with parents and administer full health checks.

Later reviews are more light touch and may just involve general health checks, height and weight monitoring.

Legislation protecting children

The government introduced several policies over the last century which protect children from engaging in potentially harmful activities:

- Children under the age of 14 cannot work, but at age 14 they can do ‘light work’.

- Children can apply for the armed forces at 15 years and 9 months, but they can’t serve until they are 16.

- 16 years of age is really where children start to get more rights – you can serve. with the armed forces, drive a moped, get a job (with training) and change your name at 16.

- At age of 18, you have reached ‘the age of entitlement’ – you are an adult.

For more details you might like to visit the ‘ at what age can I’ ? timeline.

More money spent on children

This could well be the most significant change in social attitudes to childhood, specifically in relation to the family.

A range of specialist products and services have emerged which are specifically aimed at children and child development.

Children use to be perceived as people who needed to bring money into the family home. Today adults are happy to spend more money on children.

According to one recent survey, the average family spends half their salary on their children .

Expenditure by parents on their first newborn child (on things such as push chairs) increased by almost 20% between 2013 and 2019.

According to CPAG it cost £70 000 for a two parent family to raise a child to 18 in 2022; and it cost £110 000 for a one parent family. This is not including housing or child care costs.

Parents spend more time with their children

Research from 2014 found that fathers spent seven times longer with their children compared to 40 years earlier in 1974.

Statistics from Our World in Data shows an increasing trend too.

Child Welfare

The introduction of child protection and welfare legislation, and its expansion into every aspect of child-services through Safeguarding policies.

The Stats below Public Spending on Children 2000-2020 show how a lot of the recent increase comes from more ‘community spending’ – in light blue.

The ‘rights of the child’

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child outlines several rights children have including the right

- to be heard.

- to an identity

- not to be exploited

- to an education.

There are several more, as outlined in this child friendly version of the document…

A Child Centred Society

Changes such as those outlined above suggest our society has become more child centred over the last century or so. Children today occupy a more central role than ever. The government and parents spend more money on children than ever and children are the ‘primary concern’ of many public services and often the sole thing that gives meaning to the lives of many parents.

According to Cunningham (2006) the child centred society has three main features (which is another way of summarising what’s above)

- Childhood is regarded as the opposite of adulthood – children in particular are viewed as being in need of protection from the adult world.

- Child and adult worlds are separated – they have different social spaces – playground and school for children, work and pubs for adults.

- Childhood is increasingly associated with rights.

If we look at total public expenditure on children, there certainly seems to be evidence that we live in a child centred society! (Source below) .

Criticisms of the March of Progress View of childhood

The common sense view is to see the above changes as ‘progressive’. Most people argue that now children are more protected that their lives are better, but is this actually the case?

The ‘March of Progress’ view argues that yes, children’s lives have improved and they are now much better off than in the Victorian Era and the Middle Ages. They point to all the evidence on the previous page as just self-evidently indicating an improvement to children’s’ lives.

Conflict theorists, however, argue against the view that children’s lives have gradually been getting better – they say that in some ways children’s lives are worse than they used to be. There are three main criticisms made of the march of progress view

1. Recent technological changes have resulted in significant harms to children – what Sociologist Sue Palmer refers to as Toxic Childhood .

2. Some sociologists argue that parents are too controlling of their children. Sociologists such as Frank Furedi argue that parents overprotect their children: we live in the age of ‘Paranoid Parenting’.

3. There are significant inequalities between children, so if there has been progress for some, there certainly has not been equal progress.

A further criticisms lies in the idea that childhood may now be disappearing – for more details check out this post: The Disappearance of Childhood .

Signposting

Childhood makes up part of the families and households option in the first year of A-level Sociology.

To return to the homepage – revisesociology.com

The National Archives

Child Labour: The British Library

UK Child and Labour Laws: a History

Child Employment

Public Spending on Children 2000-2020

National Minimum Wage Rates UK

Office for Budget Responsibility : Welfare Spending

NHS: Your baby’s health and developmental reviews

Children’s Commissioner: Spending on Children in England and Wales .

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

2 thoughts on “How has childhood changed since the 19th century?”

- Pingback: Assess the View that the Family has Become More Child Centred (20) | ReviseSociology

- Pingback: The Social Construction of Chilhoood | ReviseSociology

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from ReviseSociology

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Home — Essay Samples — Psychology — Childhood — How Childhood Has Changed Over The Years

How Childhood Has Changed Over The Years

- Categories: Childhood

About this sample

Words: 1531 |

Published: May 19, 2020

Words: 1531 | Pages: 3 | 8 min read

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Dr. Heisenberg

Verified writer

- Expert in: Psychology

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

2 pages / 736 words

1 pages / 465 words

6 pages / 2878 words

2 pages / 894 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Childhood

Childhood is a socially constructed concept, this means that the only reason that childhood exists is because society makes it that way. Over time childhood has changed as different norms and values over each century of life [...]

Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID), characterized by the presence of two or more distinct identities or personality states within an individual, remains a complex and often misunderstood mental health condition. Notably [...]

Friendship is a fundamental aspect of human life. This memoir reflects on the author's experiences with childhood friends, college friends, and long-distance friendships, highlighting the lessons learned and the power of [...]

The debate between video games and outdoor games as forms of recreation has become increasingly prominent in today's technology-driven society. Both types of games offer unique experiences and benefits, but they also present [...]

Are the childhoods that society reads about in popular works of literature accurate representations of how children lived throughout history, or are the authors of these texts portraying the personalities of their characters in [...]

As a child, teen, and adult we go through many stages of changes and developments from our physical stature to our emotional stages. Even the way we think can sometimes go from wanting to be an artist when we grow up to wanting [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Childhood Then and Now

Kathleen W. Jones

Yet, the same ideas that made it difficult for many families to adopt the trappings of modern childhood also spurred reformers to try to “save” dependent, delinquent, and destitute youngsters.

What is the meaning of childhood, who is a child, and who decides? Does childhood have a history? And, if so, what does that history have to tell us? These are a few of the questions that drive the comprehensive and skillfully written Huck’s Raft , a new synthesis of the history of American childhood from the colonial era to the twenty-first century by one of the premier historians in the fields of children’s and family history. Steven Mintz has managed a very difficult task with grace and aplomb. Huck’s Raft is a book for many occasions, one that deserves a wide readership among students, history scholars, and child advocates.

The title sets the tone for this book. Mark Twain’s rambunctious lad symbolizes for many the innocence of past childhoods. This nostalgic belief that American youngsters once upon a time had a carefree life is, Mintz argues, one of the myths Americans hold about the history of childhood. A better metaphor for the history of children and youth is the perilousness of Huck’s journey on the raft. Or, as Mintz puts it, “There has never been a time when the overwhelming majority of American children were well cared for and their experiences idyllic. Nor has childhood ever been an age of innocence, at least not for most children” (vii).

Mintz deftly tells the stories of both groups of children, those well cared for as well as the majority who were not. Indeed, the stories reveal that there were many different childhoods in the past, and they draw attention to the familiar inequities of race and gender, as well as ethnic and regional divisions. In Huck’s Raft, childhood is “not an unchanging biological stage of life but is, rather, a social and cultural construct that has changed radically over time” (viii). The biological facts of child development provide continuity to the history of childhood, but in every era, as Mintz shows by marshalling the works of myriad historians, biology has been “modified by history and mediated by culture” (4). Children, like their parents, lived lives constrained by the social, political, and economic context.

Of all the perils children have encountered on the metaphorical raft, however, Mintz believes that class differences have had the greatest impact on the meanings and the experiences of childhood. Different socioeconomic settings led parents to different views on the nature of childhood and the place of children in the family. By determining a child’s educational opportunities, playtime activities, and participation in the work force, class differences shaped different paths to adulthood.

Despite the fundamental role he attributes to broad social and economic forces, Mintz also wants us to recognize that children have helped to make our history. Historians are not accustomed to thinking of children as historical actors, yet this perspective has been one of the principal contributions to the discipline from those who study past childhoods. By mining the existing literature, Mintz is able to mark the times when the beliefs and actions of young people helped to make history.

In Huck’s Raft, the history of childhood is periodized as three broad and overlapping chronological eras. The eras of premodern, modern, and postmodern childhood correspond loosely to the colonial years, the mid-eighteenth century through most of twentieth, and the 1980s to the present. As the author says, each period is “characterized by strikingly different and diverse childhoods” (3). Within each era, however, Mintz takes middle-class childhood as a norm against which other (read: poor, dependent, or racial) childhoods are measured and evaluated.

Readers of Common-place will be most interested, perhaps, in Mintz’s account of colonial, or premodern childhood, in part because Mintz believes the relationships between colonial youths and their elders have much to tell us about the problems facing young people today. Colonial historians have determined that Puritan colonists conceptualized their children as adults in training, with deficiencies of skill and character that proper child rearing would overcome. Adults assumed they had much to teach young people and they hurried the integration of children into adult society through formal apprenticeship and domestic chores. For all the attention to the young, Puritans did not sentimentalize childhood. Rather, the religious sect believed that children were “riddled with corruption” (11), that it was the duty of adults to reform the child, and that the moral development of children was a responsibility of the entire community, not just the parents (a belief that led to support, in theory if not always in fact, for public education).

In discussing the premodern era, Mintz shows how gender, race, and regional differences resulted in different childhood experiences for colonial youths. Boys and girls were trained for the separate duties and tasks required in the gendered world of their day. White children found that childhood among the Indians was often much freer and less filled with drudgery (attested to by the stories of captured children who refused to return to their parents). English children in the Chesapeake colonies grew to adulthood (if they did not die young) along a different path than the one followed in Puritan communities. In part, the disparity emerged because the Chesapeake was a less religious culture (leading parents in this region to place less emphasis on shaping a child’s conscience). Perhaps a more significant contrast was the frequency with which children became orphans in the southern colonies, because these areas experienced a much higher overall death rate than New England.

Regional dissimilarities point to the importance of demography and the role of birthrates, disease, and death in the history of children and youth, issues Mintz returns to and develops in his discussions of other groups and other historical eras. Throughout the book, Mintz underscores the difficulty historians have reconstructing the past of a seemingly voiceless and powerless group, and he makes note of the creative sources used by the historians of childhood. Accounts of antebellum slave childhood, for example, rely on evidence of physical health to gauge the horrors of slavery for the young. Here, as Mintz reports, historians have made use of mortality tables, nutrition studies, and evidence collected from graveyard remains to document the poor physical condition of slave children.

Historians of antebellum middle-class childhood, in contrast, are more likely to examine their subject using psychological determinants. Mintz does not neglect the devastating effects of disease on infant and child mortality rates among all groups throughout the nineteenth century. However, he is more interested in the new emotionality characteristic of the early-nineteenth-century middle-class family. These families, Mintz explains, “invented” modern childhood as one that was sentimentalized and sheltered (76).

The antebellum creators of modern childhood drew on the antiauthoritarian ideals of the American Revolution that encouraged youthful autonomy, on Enlightenment ideas about the malleability of the child’s character, and on Romantic and religious notions of childhood innocence. It was, however, the falling birth rate and the economic comfort of the middle class that in the end allowed for the emergence of the emotionally intense family in which mothers assumed responsibility for child rearing. In this environment, childhood was supposed to be a period of freedom from labor and a time of extended formal education.

It is ironic, as Mintz points out, that this sentimental view of a sheltered childhood that “freed middle-class children from work and allowed them to devote their childhood years to education also made the labor of poor children more essential to their family’s well-being than in the past, and greatly increased the exploitation these children suffered” (92). It took over a century, or until the 1950s, before most children in the United States could be considered living a modern childhood, and even then, when baby boomers remember their innocent and carefree childhoods, their nostalgia bears little resemblance to reality. As individual chapters in the book demonstrate, the lag was due to slavery and racism, to immigration, and to the exigencies of industrial capitalism.

Yet, the same ideas that made it difficult for many families to adopt the trappings of modern childhood also spurred reformers to try to “save” dependent, delinquent, and destitute youngsters. Mintz shows how the invention of the modern child generated an awareness of child abuse, a demand for compulsory education, an end to child labor, and the need for economic assistance for children living in poverty. Clearly the history of childhood has much to contribute to our understanding of the growth of institutional bureaucracy and the rise of the welfare state. The invention of the modern child also resulted in the development of the many child sciences, for the clinical and experimental study and treatment of youth, and as a consequence, the relinquishing of a degree of parental authority to these experts.

Another irony of modern childhood is the youthful autonomy fostered by the intense adult interest in providing a sheltered childhood. Segregated in their own spaces‚from special nurseries at home to age-graded classrooms at school‚and provided with age-appropriate activities, young people developed their own culture, separate from that of adults and seemingly outside their control. The consumer economy of the twentieth century contributed to this autonomy. This, however, is a tale with more irony; the sellers who found a lucrative market among independent youths also provided a degree of informal regulation as their products constrained autonomous decisions and fueled conformity.

Mintz devotes most of the book’s chapters to the history of the modern child. As he moves the discussion on to the postmodern child, past the “youthquake” of the 1960s, the children’s rights revolution of the 1970s, and the moral panics of the 1980s and 1990s (over, for example, stranger abductions and abuse at day care centers), he shifts the focus from historical narrative to social commentary. Mintz wants to challenge today’s adults to create a childhood that reflects the realities of our children’s lives, and he draws his message directly from the history of children and youth. “Superficially,” Mintz writes, “postmodern childhood resembles premodern childhood” (4). Today’s children are in many ways “little adults.” Physiologically mature at an earlier age and initiated earlier into consumer culture, sexual experimentation, and the “realities of the adult world” (4), today’s children are forced to make adultlike decisions. Yet, thanks to the inventors of modern childhood, we postmodern adults continue to think of the young as fundamentally different from us, so we have not provided our young with the skills they need for the process. Instead, we have institutionalized childhood in schools, in after-school jobs, and in opportunities for recreation, and as a consequence, our children spend much more of their time with people of the same age. Ours is a society, Mintz explains, that isolates and juvenilizes young people more than ever before; they spend much less time with adults who can model and explain the “realities” to them. “Our challenge,” he concludes, “is to reverse the process of age segmentation” (383). “Since we cannot insulate children from all malign influences, it is essential that we prepare them to deal responsibly with the pressures and choices they face,” and that means they need knowledge, not sheltering (382). A post-postmodern childhood must address this need; the history of premodern childhood provides a guide. It shows us that when children face adultlike realities, child rearing must involve the community as a whole; it must not be left up to individual parents.

This is a big book, making it easy to quibble about what has been included and what has been slighted. Stanley Fish has just recently informed us that religion will be the next category of analysis to shape historical research, and it would be interesting to see a comprehensive history of childhood that stressed this difference along with class, race, and gender. Then too, in his emphasis on the social construction of childhood, one wonders if, perhaps, Mintz has swung the pendulum too far, dismissed too often the biological continuities in the history of childhood as he highlights the significant differences grounded in time and place. However, these are minor quibbles when set against the powerful argument supported throughout the book. The message of Huck’s Raft is one postmodern parents, child advocates, and historians would be wise to take under advisement.

Further Reading:

For Stanley Fish’s argument about religion, see “One University, Under God?” Chronicle of Higher Education 51:18 (January 7, 2005), C1.

This article originally appeared in issue 5.3 (April, 2005).

Kathleen W. Jones is an associate professor of history at Virginia Tech and author of Taming the Troublesome Child: American Families, Child Guidance, and the Limits of Psychiatric Authority (Cambridge, Mass., 1999).

Chicago Citation

Explore category.

Words to Weapons: A History of the Abolition Movement from Persuasion to Force

William Morgan

With Force and Freedom, Carter Jackson makes a stimulating and insightful debut which will have a major influence on abolition movement scholarship.

Revisiting Restoration

Jonah Estess

Women’s economic labor was essential to state function.

As Deep as it is Vast: An Introduction to The Dawn of Everything in Early America

Sean P. Harvey, Robbie Ethridge, Barbara Alice Mann, Gordon Sayre, Daniel K. Richter, and Keith Pluymers

The Dawn of Everything provides a framework that engages with “big history” or “deep history” while avoiding explanations that flirt with biological, demographic, environmental, or technological determinism.

Land that Could Become Water: Dreams of Central America in the Era of the Erie Canal

Jessica Lepler

Brockmann’s research and her insightful arguments taught me not only that plenty of knowledge production occurred in Central America before the 1820s but also that this “practical” information was designed to serve locals rather than foreigners.

Nature’s Metropolis at 30

Francesca Gamber, Thomas Andrews, Cameron Blevins, Gabriel N. Rosenberg, and Jason L. Newton

William Cronon presents in Nature’s Metropolis an assertion of the fundamental interconnectedness of the city and the countryside. This is figured in the history of Chicago, primarily in the nineteenth century, as the city grew from the commodification of the produce of its rural environs.

Graduate Training: Where Digital Scholarship and Early American Studies Meet

Benjamin Doyle

Insights by four early-career scholars who work at the intersection of early American studies and the digital humanities.

Aaron Burr and the United States Racial Imagination

Melissa Adams-Campbell

A review of Michael Drexler and Ed White’s recent collaboration, The Traumatic Colonel: The Founding Fathers, Slavery, and the Phantasmatic Aaron Burr

James Madison: Constitutional Convention Spin Doctor?

Stuart Leibiger

So mutilated did his Notes become, concludes Bilder, that even Madison himself eventually realized that he had lost forever the original convention proceedings of 1787.

Building Baltimore in Black and White

Lynda Yankaskas

Baltimore grew into America’s third-largest city in these years, and that growth was fueled by runaway slaves and white men driven to the city by changes in rural agriculture as much as by immigration from abroad.

Proslavery’s Captivating Northern Performances

Patricia Ann Lott

Jones focuses on how a proslavery “common sense” was the dominant ideological platform against which black people sought to exercise self-determination.

The Myth of Universal Education

Christina L. Davis

In 1849, Benjamin F. Roberts, an African American shoemaker, filed suit against the Boston School Committee after they […]

Frenchified Fashions and Republican Simplicity

Lynne Zacek Bassett

Clothing studies are too often overlooked by historians and even material culture scholars. Kate Haulman makes an overdue […]

Reform and Reaction: Populism in Early America

Erik J. Chaput

For the People can be profitably read as a sympathetic exposition of the various ways critics of American politics and society and adherents to popular sovereignty have been a mainstay of our political culture.

The Role of Anti-Catholicism in the U.S.-Mexican War

Michael Scott Van Wagenen

As Americans looked westward for new territory, many viewed mixed-raced Mexicans and their Roman Catholic religion as inferior and incompatible with the Anglo-Saxon Protestant republicanism that was fated to sweep the continent.

Atlantic Thermidor

James Alexander Dun

In recovering the vibrant presence of Saint Domingue/Haiti in these American moments, both books exemplify the power and promise of adopting an Atlantic lens in telling a national story…each offers a new view onto the familiar landscape of American political development between the Revolution and Reconstruction.

Related Content

Creative writing.

Excerpts From “Kingdom”

G.C. Waldrep

Welcome to Commonplace , a destination for exploring and exchanging ideas about early American history and culture. A bit less formal than a scholarly journal, a bit more scholarly than a popular magazine, Commonplace speaks—and listens—to scholars, museum curators, teachers, hobbyists, and just about anyone interested in American history before 1900. It is for all sorts of people to read about all sorts of things relating to early American life—from architecture to literature, from politics to parlor manners. It’s a place to find insightful analysis of early American history as it is discussed in scholarly literature, as it manifests on the evening news, as it is curated in museums, big and small; as it is performed in documentary and dramatic films and as it shows up in everyday life.

In addition to critical evaluations of books and websites ( Reviews ) and poetic research and fiction ( Creative Writing ), our articles explore material and visual culture ( Objects ); pedagogy, the writing of literary scholarship, and the historian’s craft ( Teach ); and diverse aspects of America’s past and its many peoples ( Learn ). For more great content, check out our other projects, ( Just Teach One ) and ( Just Teach One African American Print ).

How to cite Commonplace articles:

Author, “Title of Article,” Commonplace: the journal of early American life , date accessed, URL.

Sophie White, “Trading Looks Race, Religion and Dress in French America,” Commonplace: the journal of early American life , accessed September 30, 2019, https://commonplace.online/article/trading-looks-race-religion-dress-french-america/

Joshua R. Greenberg, editor

Read more about Commonplace

If you are looking for a specific Commonplace article from the back catalog and do not see it, or if have any other questions, please contact us directly. Please follow us on Twitter @Commonplacejrnl or Facebook @commonplacejournal and thank you for your support.

- About PDK International

- About Kappan

- Issue Archive

- Permissions

- About The Grade

- Writers Guidelines

- Upcoming Themes

- Artist Guidelines

- Subscribe to Kappan

Select Page

Childhood, then and now

By Rafael Heller | Mar 25, 2019 | Editor's Note

April 1919 — exactly a century ago, on the nose — marked the end of President Woodrow Wilson’s “Children’s Year,” a national campaign to improve infant and maternal health, provide more social services to needy families, increase school enrollments, and further reduce Americans’ reliance on child labor (which had been declining steadily for two decades).

At the time, the typical American childhood included a lot more sickness (and 1 in 10 babies died in childbirth), a lot less schooling, and a lot more manual labor than it does today. In 1919, roughly a million 10- to 15-year-olds, or roughly 8% of the age group, spent their days working on farms, in factories, or on the street. Close to 80% of children ages 5 to 17 were enrolled in school, but their numbers dwindled in the later grades — only about a quarter of 14- to 17-year-olds attended high school, and only about 1 in 10 graduated (Snyder, 1993; Yarrow, 2009).

As federal initiatives go, the Children’s Year looks to have been fairly productive. A national commission met in Washington, D.C., followed by a series of regional meetings meant to rally public and political support for efforts to help the most vulnerable children. In turn, most states proceeded to create child welfare agencies, while, across the country, millions of women mobilized to collect data on children’s health and advocate for better education and recreational activities for kids.

No doubt, the lives of American children have changed dramatically since then. However, it’s tricky to compare the experience of childhood today with that of previous generations. For example, historians argue that it wasn’t until the early 20th century, as a large middle class began to coalesce, that Americans began to conceive of childhood as the sort of special, happy stage of life that we now take to be the norm. Nor did Americans think of the teen years as a distinct phase of childhood at all until high school enrollments took off in the 1920s and ’30s.

For that matter, contemporary childhoods can look very different depending on the era you define as your point as reference. For instance, in Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis (2016), the political scientist Robert Putnam measures today’s childhoods not against the standards of 1919 but, rather, against his own childhood in the 1950s, a time when rich and poor families lived in the same neighborhood and most poor and working-class kids counted on growing up to be better off than their parents. From that vantage point — and having pored over a massive amount of data on changes in the labor market, residential patterns, family life, and student performance over the last five or six decades — Putnam sees a fracturing of childhood along economic lines, with the lives of rich and poor kids divided by a deep and ever-expanding opportunity gap.

But whatever our point of comparison, one thing is certain about childhood today: American children of all backgrounds now spend much more time in school than at any time in the past — not just dramatically more time than in 1919 but also, given rising trends in high school attendance and graduation, significantly more time than just a few years ago. As the sociologist Annette Lareau points out in this issue, educators have always played an exceptionally important role in children’s lives. Today more than ever.

References

Putnam, R.D. (2016). Our kids: The American dream in crisis. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

Snyder, T.D. (Ed.). (1993). 120 years of American education: A statistical portrait. Collingdale, PA: DIANE Publishing.

Yarrow, A.L (2009). History of U.S. children’s policy. Washington, DC: First Focus. https://firstfocus.org/resources/report/history-u-s-childrens-policy .

Citation: Heller, R. (2019). The editor’s note: C hildhood, then and now . Phi Delta Kappan , 100 ( 7 ), 4.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Rafael Heller

Rafael Heller is the former editor-in-chief of Kappan magazine.

Related Posts

There’s opportunity in the middle

September 26, 2022

Time to invest in rural education

November 29, 2021

Father knows best

March 1, 2014

Learning to lead

May 1, 2014

Recent Posts

History of early childhood education: then and now

- Posted by Steven Bonnay

- February 22, 2022

- in Posted in Leadership & administration / Spotlight

Early childhood education goes as far back as the 1500s. In this article, we explore the origin of early childhood education and the many influences that make the field what it is today. Once we’ve gotten a grasp of the history of early childhood education, we will look at the different curricula available today and assess the differences in approaches when applied to programming.

A history of early childhood education

Martin luther.

The roots of early childhood education go as far back as the early 1500s, where the concept of educating children was attributed to Martin Luther (1483-1546). Back then, very few people knew how to read and many were illiterate. Martin Luther believed that education should be universal and made it a point to emphasize that education strengthened the family as well as the community. Luther believed that children should be educated to read independently so that they could have access to the Bible. This meant that teaching children how to read at an early age would be a strong benefit to society.

John Amos Comenius

Building on this idea, the next individual who contributed to the early beginnings of early childhood education was John Amos Comenius (1592- 1670), who strongly believed that learning for children is rooted in sensory exploration . Comenius wrote the first children’s picture book to promote literacy.

Then there was John Locke (1632- 1704), who penned the famous term “blank slate”, also known as tabula rasa, which postulated that is how children start out and the environment fills their metaphorical “slate”.

Friedrich Froebel

A major influencer was Friedrich Froebel (1782 – 1852), who believed that children learn through play . He designed teacher training where he emphasized the importance of observation and developing programs and activities based on the child’s skill level and readiness. Froebel formalized the early childhood setting as well as founded the first kindergarten.

Maria Montessori

Further building from this concept, Maria Montessori (1870-1952) viewed children as a source of knowledge and the educator as a social engineer. She reviewed education as a means to enhance children’s lives, meaning the learning environment is just as important as learning itself. She took the position that children’s senses should be educated first and then the children’s intellect afterward. The Montessori Method is an internationally recognized model of educating children.

Jean Piaget

Jean Piaget (1896-1980) established a theory of learning where children’s development is broken down into a series of stages (sensory-motor, preoperational, concrete operation). Piaget theorized that children learn through direct and active interaction with the environment.

Lev Vygotsky

Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) proposed a socio-cultural position for the development of children. He believed that social interaction provides a medium for cognitive, social, and linguistic development in children. Vygotsky believed that children learn through scaffolding their skills; this meant a more capable member of the community/society would assist the child in completing tasks that were within or just above the child’s capability, which is also known as the zone of proximal development. Vygotsky emphasized collaboration and the implementation of mixed-age groupings of children to support knowledge/skill acquisition.

John Dewey (1859-1952) strongly believed that learning should originate from the interests of children, which is foundational to the project’s approach. The educator is there to promote their interests for discovery and inquiry. Dewey saw the classroom as a place to foster social consciousness and thus the classroom should be democratically run.

Rudolf Steiner

Rudolf Steiner (1861-1925), the creator of what is now known as the Waldorf education philosophy and schools, focused on developing free and morally responsible individuals with a high level of social competence. Steiner broke this down into three developmental stages; preschool to age 6 (experiential education), age 6-14 (formal education), and ages 14+ (conceptual/academic education).

Erik Erikson

Erik Erikson (1902-1994) developed psychosocial stages of development for children where the parent and educator play a pivotal role in supporting the child’s success in every stage for a positive outcome. Erikson stressed that the ordinance of social-emotional development is a key component of the early childhood curriculum.

Loris Malaguzzi

Loris Malaguzzi (1920-1994), the founder of the Reggio Emilia approach, based on the original childcare center opened in the town of Reggio Emilia, was a strong believer in documenting the children’s learning and interests which the educators would base their programming around on for the following days.

David Weikart

David Weikart (1931-2003), the founder of HighScope, which drew from the theories of Piaget, Dewey, and Vygotsky, primarily focused on the child’s intellectual maturation. The landmark study that earned HighScope validity was the Perry Preschool Project in 1962. A randomized controlled study of 123 children of similar skill levels entered the study, split into two groups; one receiving HighScope instruction while the control group did not receive it, but continued the traditional process. Results indicated an increase in academic success, academic adherence, and an increase in wages.

In general, the theorists for early education all would like to see the achievement of a common goal—to see the successful development of children in their primary years. How that goal is achieved differs in the structure of each curriculum.

Childcare Curriculum Today: A Brief Guide

Theme-based learning.

This educational method is based on certain topics that may arise from different sources, such as seasonal/weather changes, upcoming events, interests of the educator, and religious events. Theme-based learning can also have direct instruction roots. Learning is not based on the qualitative interests of the child, but rather the quantitative delivery of content by the teacher. That means program planning can be done weeks and months ahead of time. The advantage of this is that the educator knows exactly what they’re teaching. A disadvantage is that what they’re teaching may not be of interest to the child at the moment, causing them to be disengaged. Classroom learning is very structured and contingent on the current theme. That means that all the material in the classroom would have some relevance/connection to the theme at hand.

Montessori-based childcare centers are available globally. Since Montessori is a very specific style, there is also a governing body for Montessori schools and educators through which they should have their certification. This is important to note since centers may declare themselves as “Montessori” while not really adhering to the true delivery of the Montessori Method. When considering putting your child in a Montessori classroom , be aware that the classroom is structured towards the individual child and their interests. This means that the children in the classroom are given the autonomy to learn and use the material in the classroom independently. This may not be effective for all children, who may require more of a structured learning environment. There may also be transitional challenges later on when moving onto traditional or “mainstream” schools.

This method is also very unique where learning opportunities are broken down into three major components—the “plan-do-review” process to learning. Children will take a certain amount of time to plan out what they will do before acting upon it. This involves describing the materials they will use to other children they will be interacting with. When the children “do”, they execute their plan in a very purposeful way. Following the activity, they “review” or discuss with an adult and/or other children what they did and what they learned.

HighScope looks to assess the child based on anecdotal notes broken down by the following categories:

- approaches to learning

- social and emotional development

- physical development and health

- language/literacy/communication

- mathematics

- creative arts

- science and technology

- social studies

At parent conferences, these anecdotes are shared with the parents to demonstrate learning is happening within these different categories. HighScope centers should be accredited through the HighScope governing body much the same as Montessori schools, where they can label themselves as HighScope yet not truly adhere to or be recognized as accredited.

Reggio Emilia / Emergent

This approach focuses heavily on documenting the children’s learning as well as allowing the children to really take on their interests. The parents and educators as a community are there to support the learning process of the child over time that they are there at a Reggio-inspired centre . The learning is broken up into projects that are open-ended. Children are given certain concepts that they need to solve through research, questioning and experimentation. There is a strong focus on the arts, which is a vehicle to allow the child to express their thoughts and emotions through multiple mediums. Reggio also looks to expose the children to nature, which means there is a lot of outdoor play in environments that promote using natural items from the environment to be incorporated into their play. There are no standardized tests and learning is demonstrated through the projects that they explored, which is documented by the educators.

In this educational method, children are exposed to a humanitarian, socially responsible and compassionate mode of approaching the world. Typically the educator that works with one group of children will be with that same group as they get older and go from one grade to the next. The arts and academics are fused together within the lessons. These schools are also zero technology in the classroom and exposure for the children. This methodology does, however, only focus on reading when the child reaches the age of seven, with emphasis on storytelling and learning through play. Part of the Waldorf teacher training is learning about anthroposophy, developed by Rudolf Steiner.

Applications in Programming: Blended versus Traditional Approach

Given the variety of approaches to early childhood education, it begs the question: which one is the best? Or, more appropriately, does one method hold sway over another? The short, and perhaps frustrating answer is: it depends. Some programs prefer a traditional approach, adhering to a pure curriculum. Montessori and Waldorf are both approaches that can be sustained well beyond the early childhood level and into high school.

That being said, it is important to understand that methods and pedagogies are frameworks that can inspire practice rather than be a cut-and-dry rubric. In the present moment, it is increasingly the case where programs adopt a blended approach incorporating two or more methods in their program. This is due to the fact that there are distinct advantages to curating aspects from each available method, and adapting it to engage children.

Imagine a curriculum built from a combination of the different methods that allows teachers to strike a balance between instructional teaching and constructive learning. Taking this experiment further, one could technically draw on Reggio for its community and documentation; Montessori for its independent self-directed studies; Waldorf for its integration of the arts and social consciousness and lastly; High Scope for its invaluable three-step process to ensure purposeful, planned and reflected learning processes.

Ultimately, the choice of curriculum boils down to the mission of a center. Is the goal to foster community, or to bring structure and process, or to bring children back to nature, or something entirely new? These are the questions that will help curate a curriculum!

No matter which learning philosophy is followed, all of them share one very important practice: observation. Check out our posts on the importance of observation in early childhood and on childcare facts to learn more!

Steven Bonnay is a Registered Early Childhood Educator who contributes to our blog as a feature writer. He completed his ECE diploma and postgrad certificate in autism and behavior studies at Seneca College. Steven has worked both at the Seneca Lab School and as a part-time field placement professor before joining our team.

Learn how HiMama can transform your center

HiMama brings parents, teachers and directors closer together and saves everyone time.

In 15 minutes you could be on your way with HiMama - it doesn't take longer than that!

HiMama help you foster a stronger and happier community at your child care center.

- Daily reports and messaging

- Staff management and billing

- Lesson planning

14 comments

Very interesting, I had seen some preschools that were teaching with the themed curriculum as Maria Montessori is associated with, i just was not aware of the theory behind it.

i am a trained Montessori teacher and I can tell you that finding an authentic Montessori school is key to the success of the child. Prior to my training, I had my son in a a so called “Montessori” school and it was just the name, needless to say he wasted 3 years in a method that was not Montessori and he wasn’t trained properly, he’s still in Montessori and I took the training because of this experience and to advocate for authentic Montessori. The name is sadly not trademarked and anyone can call themselves Montessori school.

It really depends on the child and their unique needs and learning style. While the Montessori approach is highly regarded, it may not be the best fit for every child. For some children, expressive arts may be a crucial tool for understanding and interpreting the world around them. It’s important to consider each child’s individual strengths and needs when choosing an educational environment.

Wow thie information is exactly what i need my students to find. Short and sweet. I teach Early Childhood Education as a pathway at a high school.

hi, diane… im tharika. i also doing my diploma in these days. its early childhood education. i need some extra information about that. can u help me.. please… thank you

This is what I have been searching for all along

Wow! That is a very good one. I am a student in the university of education winneba

Wooow, this is just the perfect information I have been looking out for

Very interesting

In homeschooling, they can choose to work through their curriculum as quickly or slowly as they feel comfortable doing, establishing their own pace. A child who struggle in one or more areas academically should consider homeschooling as an excellent one-to-one environment to learn the skills necessary to catch up.