- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

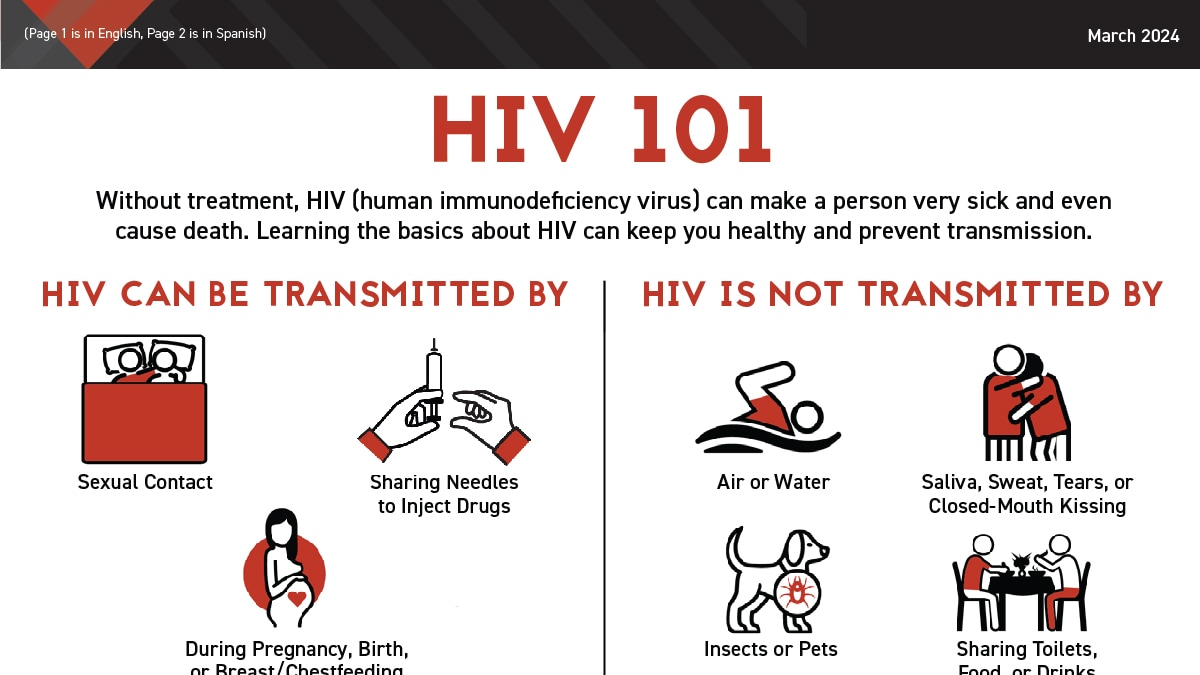

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), is an ongoing, also called chronic, condition. It's caused by the human immunodeficiency virus, also called HIV. HIV damages the immune system so that the body is less able to fight infection and disease. If HIV isn't treated, it can take years before it weakens the immune system enough to become AIDS . Thanks to treatment, most people in the U.S. don't get AIDS .

HIV is spread through contact with genitals, such as during sex without a condom. This type of infection is called a sexually transmitted infection, also called an STI. HIV also is spread through contact with blood, such as when people share needles or syringes. It is also possible for a person with untreated HIV to spread the virus to a child during pregnancy, childbirth or breastfeeding.

There's no cure for HIV / AIDS . But medicines can control the infection and keep the disease from getting worse. Antiviral treatments for HIV have reduced AIDS deaths around the world. There's an ongoing effort to make ways to prevent and treat HIV / AIDS more available in resource-poor countries.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Assortment of Pill Aids from Mayo Clinic Store

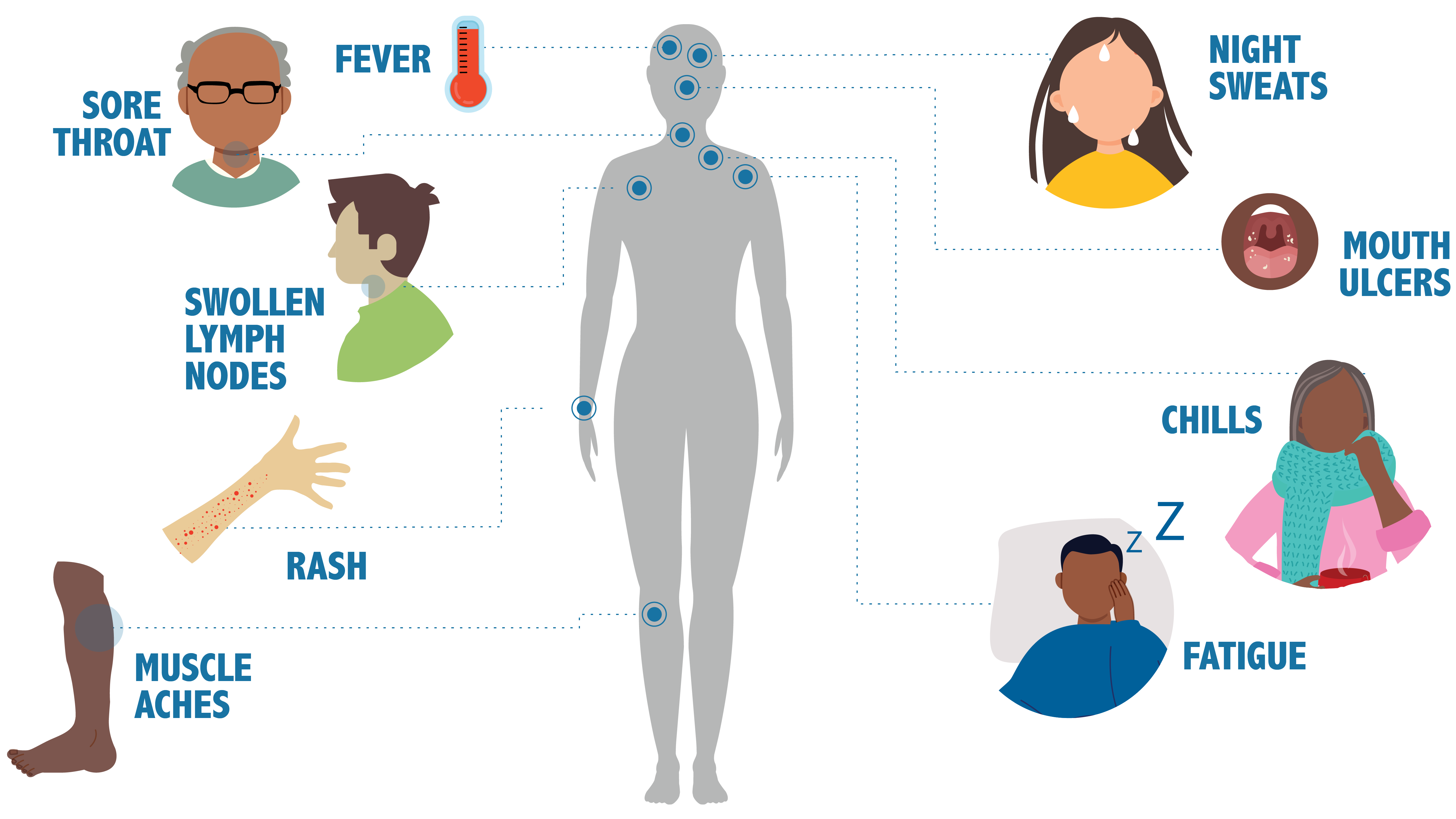

The symptoms of HIV and AIDS vary depending on the person and the phase of infection.

Primary infection, also called acute HIV

Some people infected by HIV get a flu-like illness within 2 to 4 weeks after the virus enters the body. This stage may last a few days to several weeks. Some people have no symptoms during this stage.

Possible symptoms include:

- Muscle aches and joint pain.

- Sore throat and painful mouth sores.

- Swollen lymph glands, also called nodes, mainly on the neck.

- Weight loss.

- Night sweats.

These symptoms can be so mild that you might not notice them. However, the amount of virus in your bloodstream, called viral load, is high at this time. As a result, the infection spreads to others more easily during primary infection than during the next stage.

Clinical latent infection, also called chronic HIV

In this stage of infection, HIV is still in the body and cells of the immune system, called white blood cells. But during this time, many people don't have symptoms or the infections that HIV can cause.

This stage can last for many years for people who aren't getting antiretroviral therapy, also called ART. Some people get more-severe disease much sooner.

Symptomatic HIV infection

As the virus continues to multiply and destroy immune cells, you may get mild infections or long-term symptoms such as:

- Swollen lymph glands, which are often one of the first symptoms of HIV infection.

- Oral yeast infection, also called thrush.

- Shingles, also called herpes zoster.

Progression to AIDS

Better antiviral treatments have greatly decreased deaths from AIDS worldwide. Thanks to these lifesaving treatments, most people with HIV in the U.S. today don't get AIDS . Untreated, HIV most often turns into AIDS in about 8 to 10 years.

Having AIDS means your immune system is very damaged. People with AIDS are more likely to develop diseases they wouldn't get if they had healthy immune systems. These are called opportunistic infections or opportunistic cancers. Some people get opportunistic infections during the acute stage of the disease.

The symptoms of some of these infections may include:

- Fever that keeps coming back.

- Ongoing diarrhea.

- Swollen lymph glands.

- Constant white spots or lesions on the tongue or in the mouth.

- Constant fatigue.

- Rapid weight loss.

- Skin rashes or bumps.

When to see a doctor

If you think you may have been infected with HIV or are at risk of contracting the virus, see a healthcare professional as soon as you can.

More Information

- Early HIV symptoms: What are they?

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

HIV is caused by a virus. It can spread through sexual contact, shooting of illicit drugs or use of shared needles, and contact with infected blood. It also can spread from parent to child during pregnancy, childbirth or breastfeeding.

HIV destroys white blood cells called CD4 T cells. These cells play a large role in helping the body fight disease. The fewer CD4 T cells you have, the weaker your immune system becomes.

How does HIV become AIDS?

You can have an HIV infection with few or no symptoms for years before it turns into AIDS . AIDS is diagnosed when the CD4 T cell count falls below 200 or you have a complication you get only if you have AIDS , such as a serious infection or cancer.

How HIV spreads

You can get infected with HIV if infected blood, semen or fluids from a vagina enter your body. This can happen when you:

- Have sex. You may become infected if you have vaginal or anal sex with an infected partner. Oral sex carries less risk. The virus can enter your body through mouth sores or small tears that can happen in the rectum or vagina during sex.

- Share needles to inject illicit drugs. Sharing needles and syringes that have been infected puts you at high risk of HIV and other infectious diseases, such as hepatitis.

- Have a blood transfusion. Sometimes the virus may be transmitted through blood from a donor. Hospitals and blood banks screen the blood supply for HIV . So this risk is small in places where these precautions are taken. The risk may be higher in resource-poor countries that are not able to screen all donated blood.

- Have a pregnancy, give birth or breastfeed. Pregnant people who have HIV can pass the virus to their babies. People who are HIV positive and get treatment for the infection during pregnancy can greatly lower the risk to their babies.

How HIV doesn't spread

You can't become infected with HIV through casual contact. That means you can't catch HIV or get AIDS by hugging, kissing, dancing or shaking hands with someone who has the infection.

HIV isn't spread through air, water or insect bites. You can't get HIV by donating blood.

Risk factors

Anyone of any age, race, sex or sexual orientation can have HIV / AIDS . However, you're at greatest risk of HIV / AIDS if you:

- Have unprotected sex. Use a new latex or polyurethane condom every time you have sex. Anal sex is riskier than is vaginal sex. Your risk of HIV increases if you have more than one sexual partner.

- Have an STI . Many STIs cause open sores on the genitals. These sores allow HIV to enter the body.

- Inject illicit drugs. If you share needles and syringes, you can be exposed to infected blood.

Complications

HIV infection weakens your immune system. The infection makes you much more likely to get many infections and certain types of cancers.

Infections common to HIV/AIDS

- Pneumocystis pneumonia, also called PCP. This fungal infection can cause severe illness. It doesn't happen as often in the U.S. because of treatments for HIV / AIDS . But PCP is still the most common cause of pneumonia in people infected with HIV .

- Candidiasis, also called thrush. Candidiasis is a common HIV -related infection. It causes a thick, white coating on the mouth, tongue, esophagus or vagina.

- Tuberculosis, also called TB. TB is a common opportunistic infection linked to HIV . Worldwide, TB is a leading cause of death among people with AIDS . It's less common in the U.S. thanks to the wide use of HIV medicines.

- Cytomegalovirus. This common herpes virus is passed in body fluids such as saliva, blood, urine, semen and breast milk. A healthy immune system makes the virus inactive, but it stays in the body. If the immune system weakens, the virus becomes active, causing damage to the eyes, digestive system, lungs or other organs.

- Cryptococcal meningitis. Meningitis is swelling and irritation, called inflammation, of the membranes and fluid around the brain and spinal cord, called meninges. Cryptococcal meningitis is a common central nervous system infection linked to HIV . A fungus found in soil causes it.

Toxoplasmosis. This infection is caused by Toxoplasma gondii, a parasite spread primarily by cats. Infected cats pass the parasites in their stools. The parasites then can spread to other animals and humans.

Toxoplasmosis can cause heart disease. Seizures happen when it spreads to the brain. And it can be fatal.

Cancers common to HIV/AIDS

- Lymphoma. This cancer starts in the white blood cells. The most common early sign is painless swelling of the lymph nodes most often in the neck, armpit or groin.

- Kaposi sarcoma. This is a tumor of the blood vessel walls. Kaposi sarcoma most often appears as pink, red or purple sores called lesions on the skin and in the mouth in people with white skin. In people with Black or brown skin, the lesions may look dark brown or black. Kaposi sarcoma also can affect the internal organs, including the lungs and organs in the digestive system.

- Human papillomavirus (HPV)-related cancers. These are cancers caused by HPV infection. They include anal, oral and cervical cancers.

Other complications

- Wasting syndrome. Untreated HIV / AIDS can cause a great deal of weight loss. Diarrhea, weakness and fever often happen with the weight loss.

- Brain and nervous system, called neurological, complications. HIV can cause neurological symptoms such as confusion, forgetfulness, depression, anxiety and difficulty walking. HIV -associated neurological conditions can range from mild symptoms of behavior changes and reduced mental functioning to severe dementia causing weakness and not being able to function.

- Kidney disease. HIV -associated nephropathy (HIVAN) is swelling and irritation, called inflammation, of the tiny filters in the kidneys. These filters remove excess fluid and waste from the blood and pass them to the urine. Kidney disease most often affects Black and Hispanic people.

- Liver disease. Liver disease also is a major complication, mainly in people who also have hepatitis B or hepatitis C.

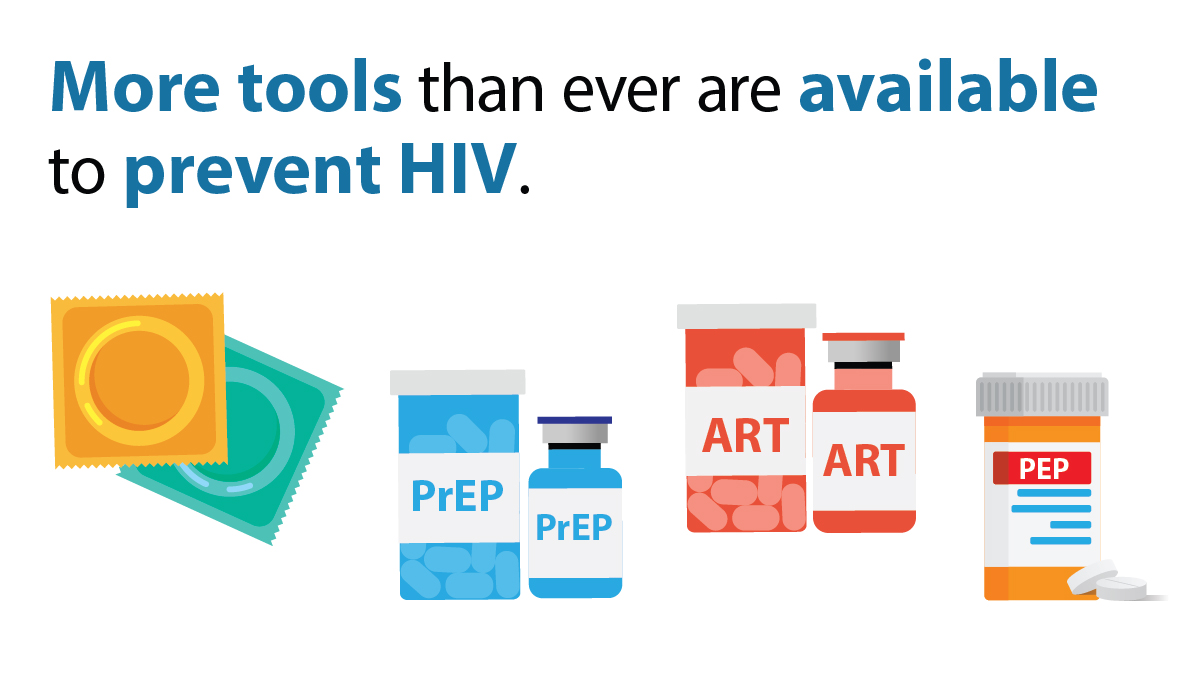

There's no vaccine to prevent HIV infection and no cure for HIV / AIDS . But you can protect yourself and others from infection.

To help prevent the spread of HIV :

Consider preexposure prophylaxis, also called PrEP. There are two PrEP medicines taken by mouth, also called oral, and one PrEP medicine given in the form of a shot, called injectable. The oral medicines are emtricitabine-tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (Truvada) and emtricitabine-tenofovir alafenamide fumarate (Descovy). The injectable medicine is called cabotegravir (Apretude). PrEP can reduce the risk of sexually transmitted HIV infection in people at very high risk.

PrEP can reduce the risk of getting HIV from sex by about 99% and from injecting drugs by at least 74%, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Descovy hasn't been studied in people who have sex by having a penis put into their vaginas, called receptive vaginal sex.

Cabotegravir (Apretude) is the first U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved PrEP that can be given as a shot to reduce the risk of sexually transmitted HIV infection in people at very high risk. A healthcare professional gives the shot. After two once-monthly shots, Apretude is given every two months. The shot is an option in place of a daily PrEP pill.

Your healthcare professional prescribes these medicines to prevent HIV only to people who don't already have HIV infection. You need an HIV test before you start taking any PrEP . You need to take the test every three months for the pills or before each shot for as long as you take PrEP .

You need to take the pills every day or closely follow the shot schedule. You still need to practice safe sex to protect against other STIs . If you have hepatitis B, you should see an infectious disease or liver specialist before beginning PrEP therapy.

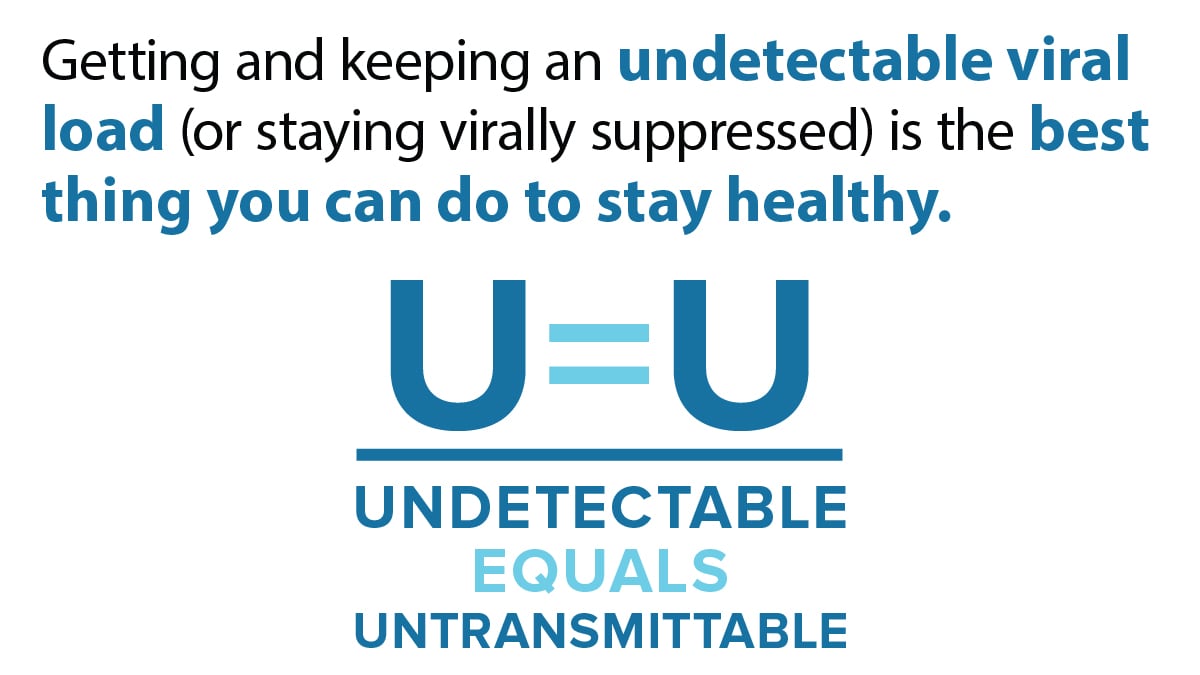

Use treatment as prevention, also called TasP. If you have HIV , taking HIV medicines can keep your partner from getting infected with the virus. If your blood tests show no virus, that means your viral load can't be detected. Then you won't transmit the virus to anyone else through sex.

If you use TasP , you must take your medicines exactly as prescribed and get regular checkups.

- Use post-exposure prophylaxis, also called PEP, if you've been exposed to HIV . If you think you've been exposed through sex, through needles or in the workplace, contact your healthcare professional or go to an emergency room. Taking PEP as soon as you can within the first 72 hours can greatly reduce your risk of getting HIV . You need to take the medicine for 28 days.

Use a new condom every time you have anal or vaginal sex. Both male and female condoms are available. If you use a lubricant, make sure it's water based. Oil-based lubricants can weaken condoms and cause them to break.

During oral sex, use a cut-open condom or a piece of medical-grade latex called a dental dam without a lubricant.

- Tell your sexual partners you have HIV . It's important to tell all your current and past sexual partners that you're HIV positive. They need to be tested.

- Use clean needles. If you use needles to inject illicit drugs, make sure the needles are sterile. Don't share them. Use needle-exchange programs in your community. Seek help for your drug use.

- If you're pregnant, get medical care right away. You can pass HIV to your baby. But if you get treatment during pregnancy, you can lessen your baby's risk greatly.

- Consider male circumcision. Studies show that removing the foreskin from the penis, called circumcision, can help reduce the risk of getting HIV infection.

- About HIV and AIDS . HIV.gov. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/about-hiv-and-aids/what-are-hiv-and-aids. Accessed Oct. 18, 2023.

- Sax PE. Acute and early HIV infection: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Oct. 18, 2023.

- Ferri FF. Human immunodeficiency virus. In: Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2024. Elsevier; 2024. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Oct. 18, 2023.

- Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in adults and adolescents with HIV . HIV.gov. https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/hiv-clinical-guidelines-adult-and-adolescent-opportunistic-infections/immunizations. Accessed Oct. 18, 2023.

- AskMayoExpert. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Mayo Clinic; 2023.

- Elsevier Point of Care. Clinical Overview: HIV infection and AIDS in adults. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Oct. 18, 2023.

- Male circumcision for HIV prevention fact sheet. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/fact-sheets/hiv/male-circumcision-HIV-prevention-factsheet.html. Accessed Oct. 19, 2023.

- Acetyl-L-carnitine. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed. Oct. 19, 2023.

- Whey protein. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed. Oct. 19, 2023.

- Saccharomyces boulardii. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed Oct. 19, 2023.

- Vitamin A. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed Oct. 19, 2023.

- Red yeast rice. Natural Medicines. https://naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.com. Accessed Oct. 19, 2023.

Associated Procedures

- Liver function tests

News from Mayo Clinic

- Unlocking the mechanisms of HIV in preclinical research Jan. 10, 2024, 03:30 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic expert on future of HIV on World AIDS Day Dec. 01, 2023, 05:15 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Minute: Know your status -- the importance of HIV testing June 27, 2023, 03:00 p.m. CDT

- Mayo Clinic Q&A podcast: The importance of HIV testing June 24, 2022, 12:18 p.m. CDT

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

- Español (Spanish)

HIV Overview

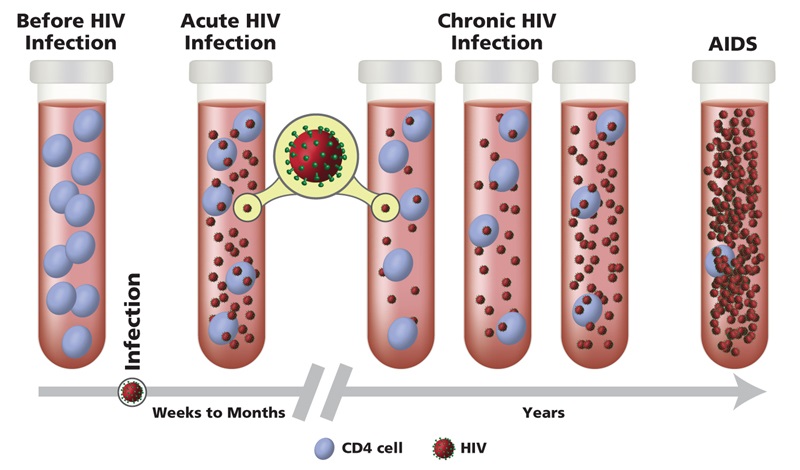

The stages of hiv infection.

- Without treatment with HIV medicines, HIV infection advances in stages, getting worse over time.

- The three stages of HIV infection are (1) acute HIV infection , (2) chronic HIV infection , and (3) acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) .

- There is no cure for HIV, but treatment with HIV medicines (called antiretroviral therapy or ART ) can slow or prevent HIV from advancing from one stage to the next. HIV medicines help people with HIV live longer, healthier lives.

HIV Infection

Without treatment, HIV infection advances in stages, getting worse over time. HIV gradually destroys the immune system and eventually causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) .

There is no cure for HIV, but treatment with HIV medicines (called antiretroviral therapy or ART ) can slow or prevent HIV from advancing from one stage to the next. HIV medicines help people with HIV live longer, healthier lives. One of the main goals of ART is to reduce a person's viral load to an undetectable level. An undetectable viral load means that the level of HIV in the blood is too low to be detected by a viral load test . People with HIV who maintain an undetectable viral load have effectively no risk of transmitting HIV to their HIV-negative partner through sex.

HIV Progression

There are three stages of HIV infection:

Acute HIV Infection

Chronic hiv infection, this fact sheet is based on information from the following sources:.

From HIV.gov:

- What Are HIV and AIDS?

From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC):

Also see the HIV Source collection of HIV links and resources.

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- How It Spreads

- Living with HIV

- HIV Awareness Days

- HIV in the United States

- Resource Library

- Occupational Exposure

- Connect With Us

- HIV Nexus Home

- HIV Public Health Partners

- Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. (EHE)

- Let's Stop HIV Together

- HIV is a virus that attacks the body's immune system.

- The only way to know if you have HIV is to get tested.

- There are many ways to prevent HIV, like using PrEP, PEP, condoms and never sharing needles.

- HIV treatment helps people live long, healthy lives and prevents HIV transmission.

HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) is a virus that attacks the body's immune system. Without treatment, it can lead to AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome).

There is currently no effective cure. Once people get HIV, they have it for life. But proper medical care can control the virus.

People with HIV who get on and stay on effective HIV treatment can live long, healthy lives and protect their partners.

Most people have flu-like symptoms within 2 to 4 weeks after infection. Symptoms may last for a few days or several weeks.

Having these symptoms alone doesn't mean you have HIV. Other illnesses can cause similar symptoms.

Some people have no symptoms at all. The only way to know if you have HIV is to get tested .

How it spreads

Most people who get HIV get it through anal or vaginal sex, or sharing needles, syringes, or other drug injection equipment.

Only certain body fluids can transmit HIV. These fluids include:

- semen ( cum ),

- pre-seminal fluid ( pre-cum ),

- rectal fluids,

- vaginal fluids, and

- breast milk.

These fluids must come in contact with a mucous membrane or damaged tissue or be directly injected into the bloodstream (from a needle or syringe) for transmission to occur.

Factors like a person's viral load, other sexually transmitted infections, and alcohol or drug use can increase the chances of getting or transmitting HIV.

But there are powerful tools that can help prevent HIV transmission .

Today, more tools than ever are available to prevent HIV.

Prevention strategies include:

- Using condoms the right way every time you have sex.

- Never sharing needles, syringes, or other drug injection equipment.

- Using PrEP (pre-exposure prophylaxis) and PEP (post-exposure prophylaxis).

If you have HIV, there are many ways to prevent transmitting HIV to others, including taking HIV treatment to get and keep an undetectable viral load.

The only way to know your HIV status is to get tested. Knowing your status gives you powerful information to keep you and your partner(s) healthy.

There are many options for quick, free, and painless HIV testing. If your test result is positive , you can take medicine to treat HIV to help you live a long, healthy life and protect others. If your test result is negative , you can take actions to prevent HIV .

Get tested for HIV

HIV treatment (antiretroviral therapy or ART) involves taking medicine as prescribed by a health care provider. You should start HIV treatment as soon as possible after diagnosis.

HIV treatment reduces the amount of HIV in the blood ( viral load ). HIV treatment can make the viral load so low that a test can't detect it ( undetectable viral load ). If you have an undetectable viral load, you will not transmit HIV to others through sex. Having an undetectable viral load also reduces the risk of HIV transmission through sharing drug injection equipment, and during pregnancy, labor, and delivery.

How it progresses

When people with HIV don't get treatment, they typically progress through three stages. But HIV treatment can slow or prevent progression of the disease. With advances in HIV treatment, progression to Stage 3 (AIDS) is less common today.

Stage 1: Acute HIV Infection

- People have a large amount of HIV in their blood and are very contagious.

- Many people have flu-like symptoms.

- If you have flu-like symptoms and think you may have been exposed to HIV, get tested .

Stage 2: Chronic HIV Infection

- This stage is also called asymptomatic HIV infection or clinical latency.

- HIV is still active and continues to reproduce in the body.

- People may not have any symptoms or get sick during this phase but can transmit HIV.

- People who take HIV treatment as prescribed may never move into Stage 3 (AIDS).

- Without HIV treatment, this stage may last a decade or longer, or may progress faster.

- At the end of this stage, the amount of HIV in the blood ( viral load ) goes up and the person may move into Stage 3 (AIDS).

Stage 3: Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS)

- The most severe stage of HIV infection.

- People receive an AIDS diagnosis when their CD4 cell count drops below 200 cells per milliliter of blood, or they develop certain illnesses (sometimes called opportunistic infections).

- People with AIDS can have a high viral load and may easily transmit HIV to others.

- People with AIDS have damaged immune systems.

- They can get an increasing number of other serious illnesses.

- Without HIV treatment, people with AIDS typically survive about three years.

HIV and AIDS Timeline

Learn about HIV and how the virus is transmitted, how to protect yourself and others, and how to live well with HIV. Also learn how HIV impact the American people.

CAROLYN CHU, MD, MSc, AND PETER A. SELWYN, MD, MPH

Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(10):1239-1244

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Recognition and diagnosis of acute human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection in the primary care setting presents an opportunity for patient education and health promotion. Symptoms of acute HIV infection are nonspecific (e.g., fever, malaise, myalgias, rash), making misdiagnosis common. Because a wide range of conditions may produce similar symptoms, the diagnosis of acute HIV infection involves a high index of suspicion, a thorough assessment of HIV exposure risk, and appropriate HIV-related laboratory tests. HIV RNA viral load testing is the most useful diagnostic test for acute HIV infection because HIV antibody testing results are generally negative or indeterminate during acute HIV infection. After the diagnosis of acute HIV infection is confirmed, physicians should discuss effective transmission risk reduction strategies with patients. The decision to initiate antiretroviral therapy should be guided by consultation with an HIV specialist.

Acute human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, also known as primary HIV infection or acute retroviral syndrome, is the period just after initial HIV infection, generally before seroconversion. Although some patients remain asymptomatic, acute HIV infection often manifests with transient symptoms related to high levels of HIV viral replication and the subsequent immune response. Because symptoms of acute HIV infection (e.g., fever, rash, malaise, sore throat) mimic other, more prevalent conditions, such as influenza, misdiagnosis is common. Furthermore, patterns of care for patients seeking medical attention for acute HIV infection are largely unknown. One study based on a national probability sample of patients presenting to physician offices, emergency departments, and hospital out-patient clinics estimated rates of acute HIV infection to be 0.13 to 0.66 percent among symptomatic ambulatory patients, 1 making detection a clinical and public health challenge.

Acute HIV infection provides a unique opportunity for patient education, health promotion, and prevention; primary care physicians must be able to recognize and diagnose it. This article provides an update to previously published reviews of acute HIV syndrome. 2 – 4

Epidemiology

In the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's most recent HIV/AIDS surveillance report, the number of new adult and adolescent HIV infections in the United States during 2006 was estimated to be 56,300 (a rate of 22.8 per 100,000 persons). 5 There were notable disparities and trends among certain subgroups. The incidence rate in non-Hispanic blacks versus non-Hispanic whites was 83.7 versus 11.5 per 100,000 persons. Also, persons 40 to 49 years of age accounted for 25 percent of all new infections, whereas those 50 years and older accounted for 10 percent. Persons infected through high-risk heterosexual contact represented 31 percent of new infections, compared with 12 percent for those infected through injection drug use. Although such patterns indicate that certain populations are at higher risk of infection, HIV continues to affect every ethnic, age, and risk group and every geographic area in the United States. Physicians must keep acute HIV infection in the differential diagnosis of any patient with otherwise unexplained symptoms.

Clinical Presentation

At least 50 (and up to 90) percent of patients with acute HIV infection develop symptoms consistent with acute infection, 6 , 7 although timing and duration are variable. For most symptomatic patients, acute illness develops within one to four weeks after transmission, and symptoms usually persist for two to four weeks. Acute HIV infection is often described as mononucleosis-or influenza-like, with the most prevalent symptoms being fever, fatigue, myalgias/arthralgias, rash (typically an erythematous maculopapular exanthem), and headache 6 – 10 ( Tables 1 8 , 9 and 2 ) . Patients also may experience anorexia, pharyngitis, lymphadenopathy, mucocutaneous ulcerations, diarrhea, or a combination of these symptoms. Severe manifestations of acute HIV infection (e.g., meningoencephalitis, myelitis), although rare, have been described. 11 CD4 lymphocyte counts exhibit a marked transient decrease during acute infection. There have been case reports of patients with acute infection presenting with opportunistic infections, such as esophageal candidiasis. 12 Physical examination is nondiagnostic but may be notable for hepatosplenomegaly.

Because symptoms are nonspecific, symptom-based algorithms are generally not useful in detecting acute HIV infection in the general U.S. population. However, such algorithms are being combined with clinical risk factors to develop targeted testing strategies in high-risk and high-prevalence groups, such as populations in sub-Saharan Africa. 13 , 14 Physicians should be aware of current HIV transmission patterns in their communities (e.g., men who have sex with men, persons who share needles) but should retain a low threshold to consider acute infection in anyone presenting with any constellation of suggestive symptoms. Evaluation should include a thorough and accurate assessment of all activities that potentially involve HIV exposure, including heterosexual intercourse with a long-term partner.

Testing for Acute HIV Infection

With the evolution of HIV enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA) from first to third generation tests, the window period (i.e., the time between transmission and production of HIV antibodies when an HIV ELISA test result may be falsely negative) for confirming HIV infection through antibody testing has narrowed from approximately 56 to 21 days. However, because acute HIV infection occurs before the appearance of HIV antibodies, it can be diagnosed only by demonstrating the presence of p24 antigen or HIV viral RNA, which can be detected as early as 14 to 15 days and 11 to 12 days after infection, respectively ( Table 3 15 and Figure 1 16 ) .

The usefulness of p24 testing for acute HIV infection is somewhat limited because (1) HIV viral load assays are now more widely available in the United States, and (2) the level of sufficiently detectable p24 antigenemia in patients is inconsistent and short-lived (i.e., serum p24 levels typically decrease as HIV antibody titers increase and immune complexes develop). However, some new rapid HIV tests, which are generally HIV antibody–based, may also include p24 antigen testing. This makes them potentially valuable for point-of-care detection of acute HIV infection. 17

Because of the limitations of p24 antigen testing, HIV RNA viral load is arguably the most useful diagnostic marker for acute HIV infection. It has a sensitivity close to 100 percent and a specificity from 95 to 98 percent, depending on the type of assay. 8 In patients with acute HIV infection, RNA levels typically rise above 100,000 copies per mL. Low viral loads (particularly 1,000 RNA copies per mL or less) in a person with suspected acute HIV infection may indicate a false-positive result. 18 To confirm the diagnosis of acute HIV infection (or rule out infection in patients with a low but detectable RNA level), viral load testing should be repeated with ELISA and Western blot test within four to six weeks. 19 , 20

Initial Management of Acute HIV Infection

One of the most important clinical considerations for patients with acute HIV infection is psychosocial evaluation and stabilization, including a domestic violence screen and referral to counseling or support services if available. Physicians should educate patients about their potentially heightened infectiousness, 21 , 22 and discuss effective transmission risk reduction strategies. 23 , 24 These include consistent and effective condom use, limiting drug and alcohol intake (which may impair the ability to negotiate safe sex), and the incorporation of alternative sexual practices that do not involve the exchange of body fluids. Patients, particularly men who have sex with men, should be warned of the risks of serosorting, which is the identification of sex partners based on their HIV status that may lead to unprotected intercourse. 25 Partner notification should be discussed with all patients with acute HIV infection and carried out promptly per local health department guidelines.

Because symptoms of acute infection are usually self-limited, specific management is often supportive. Treatment may include antipyretics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and close follow-up of significant laboratory abnormalities (e.g., anemia, thrombocytopenia, elevated transaminases). A proportion of patients with severe symptoms or laboratory abnormalities may require hospitalization; steroids have not been consistently effective in these patients. 11 , 26

Several additional laboratory tests should be performed once acute HIV infection is diagnosed: two sets of CD4 lymphocyte counts and HIV viral load levels within four to six weeks to monitor the level of immune suppression and viremia; screening for other sexually transmitted infections (e.g., chlamydia, gonorrhea, syphilis) and hepatitis B and C; and skin testing for tuberculosis. 27 Given the prevalence of primary antiretroviral drug resistance that has been described in some populations, 28 an HIV genotype should be strongly considered to detect transmitted mutations that may cause resistance to future antiretroviral treatment. 27 , 29 A repeat HIV antibody test should also be performed within four to six weeks to document seroconversion ( Figure 2 18 – 20 , 23 , 24 , 27 , 29 – 31 ) .

There is ongoing debate about the role of combination, highly active antiretroviral therapy in acute HIV infection. The relationships between symptom severity, level of viremia, and CD8 lymphocyte activation response in acute infection are complicated. Research suggests these factors are major determinants of subsequent HIV disease progression by affecting the rate of CD4 lymphocyte loss and the viral set point (the rate of HIV virus replication that stabilizes and remains at a particular level after acute infection). 32 – 34 It has been theorized that treatment of acute HIV infection may alter the natural course of HIV infection or delay the need for chronic antiretroviral therapy by preserving immune function. 35 Treatment may also have wider public health implications by reducing transmission. 36 Longitudinal studies have sought to identify the virologic, immunologic, and clinical benefits of antiretroviral therapy initiation during acute infection, but results from these studies have been inconclusive. Current evidence suggests there is not significant long-term or clinically meaningful improvement despite short-term viral suppression and CD4 lymphocyte restoration. 37 – 40 Therefore, antiretroviral therapy for patients with acute HIV infection should be initiated only after consultation with an HIV specialist. 30 , 31

If therapy is initiated, specific guidelines for recommended antiretroviral combinations and follow-up can be found on the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services AIDSinfo Web site at http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/guidelines/ . Physicians may also refer patients to clinical trials on the natural history and treatment outcomes of acute HIV infection. Information on these trials may be found on the AIDSinfo Web site at http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/clinicaltrials/ or by calling 800-HIV-0440.

Coco A, Kleinhans E. Prevalence of primary HIV infection in symptomatic ambulatory patients. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(5):400-404.

Daar ES, Pilcher CD, Hecht FM. Clinical presentation and diagnosis of primary HIV-1 infection. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2008;3(1):10-15.

Taiwo BO, Hicks CB. Primary human immunodeficiency virus. South Med J. 2002;95(11):1312-1317.

Perlmutter BL, Glaser JB, Oyugi SO. How to recognize and treat acute HIV syndrome [published correction appears in Am Fam Physician . 2000;61(2):308]. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60(2):535-542.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cases of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and dependent areas, 2007. HIV/AIDS surveillance report, volume 19. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/2007report/ . Accessed July 1, 2009.

Lavreys L, Thompson ML, Martin HL, et al. Primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection: clinical manifestations among women in Mombasa, Kenya. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(3):486-490.

Schacker T, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic features of primary HIV infection [published correction appears in Ann Intern Med . 1997;126(2):174]. Ann Intern Med. 1996;125(4):257-264.

Hecht FM, Busch MP, Rawal B, et al. Use of laboratory tests and clinical symptoms for identification of primary HIV infection. AIDS. 2002;16(8):1119-1129.

Daar ES, Little S, Pitt J, et al. Diagnosis of primary HIV-1 infection. Los Angeles County Primary HIV Infection Recruitment Network. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(1):25-29.

Vanhems P, Hughes J, Collier AC, et al. Comparison of clinical features, CD4 and CD8 responses among patients with acute HIV-1 infection from Geneva, Seat-tle and Sydney. AIDS. 2000;14(4):375-381.

Douvoyiannis M, Litman N. Acute encephalopathy and multi-organ involvement with rhabdomyolysis during primary HIV infection. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13(5):e299-e304.

Manata MJ, Melo AZ, Quaresma MJ. Esophageal candidiasis in acute HIV infection. Presented at: International Conference on AIDS; August 7–12, 1994; Lisbon, Portugal. Abstract PB0593.

Miller WC, Leone PA, McCoy S, Nguyen TQ, Williams DE, Pilcher CD. Targeted testing for acute HIV infection in North Carolina. AIDS. 2009;23(7):835-843.

Powers KA, Miller WC, Pilcher CD, et al.; Malawi UNC Project Acute HIV Study Team. Improved detection of acute HIV-1 infection in sub-Saharan Africa: development of a risk score algorithm. AIDS. 2007;21(16):2237-2242.

Busch MP, Satten GA. Time course of viremia and anti-body seroconversion following human immuno deficiency virus exposure. Am J Med. 1997;102(5B):117-124.

Pantaleo G, Graziosi C, Fauci AS. New concepts in the immunopathogenesis of human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(5):327-335.

Weber B, Orazi B, Raineri A, et al. Multicenter evaluation of a new 4th generation HIV screening assay Elecsys HIV combi. Clin Lab. 2006;52(9–10):463-473.

Rich JD, Merriman NA, Mylonakis E, et al. Misdiagnosis of HIV infection by HIV-1 plasma viral load testing: a case series. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(1):37-39.

Chou R, Huffman LH, Fu R, Smits AK, Korthuis PT. Screening for HIV: a review of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(1):55-73.

Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Update: serologic testing for HIV-1 antibody—United States, 1988 and 1989. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1990;39(22):380-383.

Lee CC, Sun YJ, Barkham T, Leo YS. Primary drug resistance and transmission analysis of HIV-1 in acute and recent drug-naïve seroconverters in Singapore. HIV Med. 2009;10(6):370-377.

Brenner BG, Roger M, Routy JP, et al.; Quebec Primary HIV Infection Study Group. High rates of forward transmission events after acute/early HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis. 2007;195(7):951-959.

Incorporating HIV prevention into the medical care of persons living with HIV. Recommendations of CDC, the Health Resources and Services Administration the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America [published correction appears in [MMWR Recomm Rep. 2004;53(32):744]. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2003;52(RR-12):1-24.

Healthy Living Project Team. Effects of a behavioral intervention to reduce risk of transmission among people living with HIV: the healthy living project randomized controlled study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44(2):213-221.

Xia Q, Molitor F, Osmond DH, et al. Knowledge of sexual partner's HIV serostatus and serosorting practices in a California population-based sample of men who have sex with men. AIDS. 2006;20(16):2081-2089.

Tambussi G, Gori A, Capiluppi B, et al. Neurological symptoms during primary human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection correlate with high levels of HIV RNA in cerebrospinal fluid. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(6):962-965.

Aberg JA, Gallant JE, Anderson J, et al. Primary care guidelines for the management of persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus: recommendations of the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(5):609-629.

Truong HM, et al. Routine surveillance for the detection of acute and recent HIV infections and transmission of antiretroviral resistance. AIDS. 2006;20(17):2193-2197.

Hirsch MS, Brun-Vézinet F, D'Aquila RT, et al. Antiretroviral drug resistance testing in adult HIV-1 infection: recommendations of an International AIDS Society-USA Panel. JAMA. 2000;283(18):2417-2426.

Landon BE, et al. Physician specialization and the quality of care for human immunodeficiency virus infection. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(10):1133-1139.

Landon BE, Wilson IB, Cohn SE, et al. Physician specialization and antiretroviral therapy for HIV. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(4):233-241.

Kelley CF, Barbour JD, Hecht FM. The relation between symptoms, viral load, and viral load set point in primary HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;45(4):445-448.

Streeck H, Jolin JS, Qi Y, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1-specific CD8+ T-cell responses during primary infection are major determinants of the viral set point and loss of CD4+ T cells. J Virol. 2009;83(15):7641-7648.

Burgers WA, et al.; CAPRISA 002 Acute Infection Study Team. Association of HIV-specific and total CD8+ T memory phenotypes in subtype C HIV-1 infection with viral set point. J Immunol. 2009;182(8):4751-4761.

Oxenius A, Price DA, Easterbrook PJ, et al. Early highly active antiretroviral therapy for acute HIV-1 infection preserves immune function of CD8+ and CD4+ T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(7):3382-3387.

Koopman JS, et al. The role of early HIV infection in the spread of HIV through populations. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1997;14(3):249-258.

Pantazis N, et al.; CASCADE Collaboration. The effect of antiretroviral treatment of different durations in primary HIV infection. AIDS. 2008;22(18):2441-2450.

Voirin N, et al. Effect of early initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy on CD4 cell count and HIV-RNA viral load trends within 24 months of the onset of acute retroviral syndrome. HIV Med. 2008;9(6):440-444.

Hecht FM, Wang L, Collier A, et al.; AIEDRP Network. A multicenter observational study of the potential benefits of initiating combination antiretroviral therapy during acute HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2006;194(6):725-733.

Smith DE, et al. Is antiretroviral treatment of primary HIV infection clinically justified on the basis of current evidence?. AIDS . 2004;18(5):709-718.

Continue Reading

More in AFP

More in pubmed.

Copyright © 2010 by the American Academy of Family Physicians.

This content is owned by the AAFP. A person viewing it online may make one printout of the material and may use that printout only for his or her personal, non-commercial reference. This material may not otherwise be downloaded, copied, printed, stored, transmitted or reproduced in any medium, whether now known or later invented, except as authorized in writing by the AAFP. See permissions for copyright questions and/or permission requests.

Copyright © 2024 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

2.4 Clinical presentation in HIV-infected persons

Among HIV-infected persons, TB is the most common opportunistic infection and a leading cause of morbidity and mortality [1] Citation 1. Ford, N., et al., TB as a cause of hospitalization and in-hospital mortality among people living with HIV worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Journal of the International AIDS Society 2016, 19:20714. https://doi.org/ 10.7448/IAS.19.1.20714 . According to the WHO clinical staging system for HIV/AIDS, individuals with PTB are in clinical stage 3 and patients with EPTB in clinical stage 4 [2] Citation 2. World Health Organization . WHO Case definitions of HIV for Surveillance and Revised Clinical Staging and Immunological Classification of HIV-related disease in adults and children . Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43699 .

In the early stages of HIV infection, when the immune system is functioning relatively normally, the clinical signs of TB are similar to those in non-infected individuals.

As the immune system deteriorates in later stages of the disease, smear-negative PTB, disseminated TB and EPTB become more common. These cases are more difficult to diagnose, and have a higher fatality rate than smear-positive PTB cases. Patients may have difficulty expectorating, so more advanced sputum collection techniques may be necessary ( Chapter 3 and Appendix 3 ).

The algorithm presented in Chapter 5 use clinical criteria combined with laboratory and other investigations to help diagnose TB in HIV-infected persons.

Table 2.2 provides a differential diagnosis of PTB in HIV-infected persons.

Table 2.2 – Differential diagnosis for PTB

The most common EPTB in HIV-infected persons are miliary TB, TB meningitis and diffuse lymphadenopathy in children, and lymph node TB, pleural effusion, pericarditis, TB meningitis and miliary TB in adults.

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) is a clinical presentation of TB in patients starting antiretroviral therapy. For clinical presentation and management of IRIS, see Chapter 12 .

- 1. Ford, N., et al., TB as a cause of hospitalization and in-hospital mortality among people living with HIV worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Journal of the International AIDS Society 2016, 19:20714. https://doi.org/ 10.7448/IAS.19.1.20714

- 2. World Health Organization . WHO Case definitions of HIV for Surveillance and Revised Clinical Staging and Immunological Classification of HIV-related disease in adults and children . Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43699

- Español (Spanish)

clinicalinfo.hiv.gov

Offering information on hiv/aids treatment, prevention, and research, clinical guidelines, drug database, capsid inhibitors.

- Read more about Capsid Inhibitors

Appendix E. Archived Sections

- Read more about Appendix E. Archived Sections

Appendix A. Key to Acronyms

- Read more about Appendix A. Key to Acronyms

Appendix B: Mpox

- Read more about Appendix B: Mpox

Drug-Drug Interactions: Capsid Inhibitors and Other Drugs

- Read more about Drug-Drug Interactions: Capsid Inhibitors and Other Drugs

Study and Trial Names

- Read more about Study and Trial Names

General Terms

- Read more about General Terms

Drug Name Abbreviations

- Read more about Drug Name Abbreviations

Antiretroviral Drug Regimens and Pregnancy Outcomes

- Read more about Antiretroviral Drug Regimens and Pregnancy Outcomes

Teratogenicity

- Read more about Teratogenicity

Clinical presentation and diagnosis of primary HIV-1 infection

Affiliation.

- 1 Department of Medicine, Division of HIV Medicine, Los Angeles Biomedical Research Institute at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, USA.

- PMID: 19372938

- DOI: 10.1097/COH.0b013e3282f2e295

Purpose of review: To describe current findings concerning the clinical manifestations and diagnosis of primary HIV-1 infection.

Recent findings: HIV-1 seroconversion can occur with a variety of clinical manifestations or without symptoms. More severe and numerous symptoms during primary HIV-1 infection predict a higher plasma HIV-1 RNA set-point and faster disease progression. While detection of primary HIV-1 infection is potentially very important for HIV-1 prevention and may offer clinical benefits, the diagnosis is often missed. Diagnosis of symptomatic individuals with antibody-negative HIV-1 infection requires recognition of the diverse signs and symptoms of this syndrome. Diagnostic tests for primary HIV-1 infection include assays for HIV-1 RNA, p24 antigen, and third generation enzyme immunoassay antibody tests capable of detecting IgM antibodies. Targeting these tests using clinical presentation alone will probably miss the diagnosis in many individuals. Consequently, increasing effort has gone into developing strategies to incorporate the use of these assays into routine HIV-1 testing algorithms.

Summary: More numerous and severe primary HIV-1 infection symptoms predict more rapid disease progression. Pooled HIV-1 RNA screening and fourth generation HIV-1 enzyme immunoassay antibody tests with sensitive p24 antigen detection are beginning to be implemented in routine HIV-1 testing algorithms, but further research is needed to define optimal strategies for increasing detection of primary HIV-1 infection.

Learn how UpToDate can help you.

Select the option that best describes you

- Medical Professional

- Resident, Fellow, or Student

- Hospital or Institution

- Group Practice

- Patient or Caregiver

- Find in topic

RELATED TOPICS

INTRODUCTION

The case definition and classification of pediatric HIV infection, clinical manifestations of some of the AIDS-defining conditions ( table 1 ), and outcomes of HIV infection in children are reviewed here. The epidemiology of pediatric HIV, prophylactic treatment of infants born to mothers with HIV, diagnostic testing for HIV in young children, approach to febrile HIV-infected infants and children, and issues related to HIV infection in adolescents are discussed separately:

● (See "Epidemiology of pediatric HIV infection" .)

● (See "Intrapartum and postpartum management of pregnant women with HIV and infant prophylaxis in resource-rich settings", section on 'Infant prophylaxis' .)

● (See "Diagnostic testing for HIV infection in infants and children younger than 18 months" .)

- What Are HIV and AIDS?

- How Is HIV Transmitted?

- Who Is at Risk for HIV?

- Symptoms of HIV

- U.S. Statistics

- Impact on Racial and Ethnic Minorities

- Global Statistics

- HIV and AIDS Timeline

- In Memoriam

- Supporting Someone Living with HIV

- Standing Up to Stigma

- Getting Involved

- HIV Treatment as Prevention

- Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP)

- Post-exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)

- Preventing Sexual Transmission of HIV

- Alcohol and HIV Risk

- Substance Use and HIV Risk

- Preventing Perinatal Transmission of HIV

- HIV Vaccines

- Long-acting HIV Prevention Tools

- Microbicides

- Who Should Get Tested?

- HIV Testing Locations

- HIV Testing Overview

- Understanding Your HIV Test Results

- Living with HIV

- Talking About Your HIV Status

- Locate an HIV Care Provider

- Types of Providers

- Take Charge of Your Care

- What to Expect at Your First HIV Care Visit

- Making Care Work for You

- Seeing Your Health Care Provider

- HIV Lab Tests and Results

- Returning to Care

- HIV Treatment Overview

- Viral Suppression and Undetectable Viral Load

- Taking Your HIV Medicine as Prescribed

- Tips on Taking Your HIV Medication Every Day

- Paying for HIV Care and Treatment

- Other Health Issues of Special Concern for People Living with HIV

- Alcohol and Drug Use

- Coronavirus (COVID-19) and People with HIV

- Hepatitis B & C

- Vaccines and People with HIV

- Flu and People with HIV

- Mental Health

- Mpox and People with HIV

- Opportunistic Infections

- Sexually Transmitted Infections

- Syphilis and People with HIV

- HIV and Women's Health Issues

- Aging with HIV

- Emergencies and Disasters and HIV

- Employment and Health

- Exercise and Physical Activity

- Food Safety and Nutrition

- Housing and Health

- Traveling Outside the U.S.

- Civil Rights

- Workplace Rights

- Limits on Confidentiality

- National HIV/AIDS Strategy (2022-2025)

- Implementing the National HIV/AIDS Strategy

- Prior National HIV/AIDS Strategies (2010-2021)

- Key Strategies

- Priority Jurisdictions

- HHS Agencies Involved

- Learn More About EHE

- Ready, Set, PrEP

- Ready, Set, PrEP Pharmacies

- Ready, Set, PrEP Resources

- AHEAD: America’s HIV Epidemic Analysis Dashboard

- HIV Prevention Activities

- HIV Testing Activities

- HIV Care and Treatment Activities

- HIV Research Activities

- Activities Combating HIV Stigma and Discrimination

- The Affordable Care Act and HIV/AIDS

- HIV Care Continuum

- Syringe Services Programs

- Finding Federal Funding for HIV Programs

- Fund Activities

- The Fund in Action

- About PACHA

- Members & Staff

- Subcommittees

- Prior PACHA Meetings and Recommendations

- I Am a Work of Art Campaign

- Awareness Campaigns

- Global HIV/AIDS Overview

- U.S. Government Global HIV/AIDS Activities

- U.S. Government Global-Domestic Bidirectional HIV Work

- Global HIV/AIDS Organizations

- National Black HIV/AIDS Awareness Day February 7

- HIV Is Not A Crime Awareness Day February 28

- National Women and Girls HIV/AIDS Awareness Day March 10

- National Native HIV/AIDS Awareness Day March 20

- National Youth HIV & AIDS Awareness Day April 10

- HIV Vaccine Awareness Day May 18

- National Asian & Pacific Islander HIV/AIDS Awareness Day May 19

- HIV Long-Term Survivors Awareness Day June 5

- National HIV Testing Day June 27

- Zero HIV Stigma July 21

- Southern HIV/AIDS Awareness Day August 20

- National Faith HIV/AIDS Awareness Day August 27

- National African Immigrant and Refugee HIV/AIDS and Hepatitis Awareness Day September 9

- National HIV/AIDS and Aging Awareness Day September 18

- National Gay Men's HIV/AIDS Awareness Day September 27

- National Latinx AIDS Awareness Day October 15

- World AIDS Day December 1

- Event Planning Guide

- U.S. Conference on HIV/AIDS (USCHA)

- National Ryan White Conference on HIV Care & Treatment

- AIDS 2020 (23rd International AIDS Conference Virtual)

Want to stay abreast of changes in prevention, care, treatment or research or other public health arenas that affect our collective response to the HIV epidemic? Or are you new to this field?

HIV.gov curates learning opportunities for you, and the people you serve and collaborate with.

Stay up to date with the webinars, Twitter chats, conferences and more in this section.

Resources for 2024 HIV Vaccine Awareness Day

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

- Share on LinkedIn

- Share on Email

Resources to highlight HIV Vaccine Awareness Day on May 18, a day to recognize the community members, health professionals, and scientists working together to develop a vaccine for HIV prevention.

This week, on May 18, we observe the 27th annual HIV Vaccine Awareness Day (HVAD ). As we work toward a preventative vaccine, HVAD is an opportunity to learn more about HIV vaccine research and the latest developments. It is also a day to recognize the many volunteers, community members, health professionals, and scientists working together to develop a safe and effective vaccine for HIV prevention.

The National institutes of Health’s National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) leads this day and has spearheaded several initiatives focused on the advancement of HIV research, prevention, and treatment. Please stay tuned for an additional video resource discussing more about this day on HIV.gov.

You can also learn more about HIV vaccines on HIV.gov and find more information about the day on our events page .

You can find more data about HIV in the United States using the AHEAD dashboard .

HIV.gov regularly blogs on key developments in HIV vaccine research; our goal is to provide user-friendly content informing the general public and scientists researching and working in other health arenas about the research. To keep up with the science, follow the “vaccines” blog tag on HIV.gov and follow @NIAIDNews and @HIVgov on social media.

Join the Conversation:

You can find social media resources here . Use the hashtag #HVAD and follow, like, or share content on these channels:

- Facebook: HIVgov Exit Disclaimer , CDC HIV Exit Disclaimer , @NIAID.NIH Exit Disclaimer

- X/Twitter: @HIVGov Exit Disclaimer , @CDC_HIV Exit Disclaimer , @NIAIDNews Exit Disclaimer

- Instagram: @HIVgov Exit Disclaimer , @stophivtogether Exit Disclaimer , @NIAID Exit Disclaimer

- LinkedIn: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Exit Disclaimer

Related HIV.gov Blogs

- Awareness Days

- HIV Vaccine Awareness Day

- NIAID National Institute of Allergy & Infectious Diseases

- Case report

- Open access

- Published: 25 May 2024

Wandering spleen presenting in the form of right sided pelvic mass and pain in a patient with AD-PCKD: a case report and review of the literature

- Yitagesu aberra shibiru ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3645-9115 1 ,

- Sahlu wondimu 1 &

- Wassie almaw 1

Journal of Medical Case Reports volume 18 , Article number: 259 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

77 Accesses

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Wandering spleen is a rare clinical entity in which the spleen is hypermobile and migrate from its normal left hypochondriac position to any other abdominal or pelvic position as a result of absent or abnormal laxity of the suspensory ligaments (Puranik in Gastroenterol Rep 5:241, 2015, Evangelos in Am J Case Rep. 21, 2020) which in turn is due to either congenital laxity or precipitated by trauma, pregnancy, or connective tissue disorder (Puranik in Gastroenterol Rep 5:241, 2015, Jawad in Cureus 15, 2023). It may be asymptomatic and accidentally discovered for imaging done for other reasons or cause symptoms as a result of torsion of its pedicle and infarction or compression on adjacent viscera on its new position. It needs to be surgically treated upon discovery either by splenopexy or splectomy based on whether the spleen is mobile or not.

Case presentation

We present a case of 39 years old female Ethiopian patient who presented to us complaining constant lower abdominal pain especially on the right side associated with swelling of one year which got worse over the preceding few months of her presentation to our facility. She is primiparous with delivery by C/section and a known case of HIV infection on HAART. Physical examination revealed a right lower quadrant well defined, fairly mobile and slightly tender swelling. Hematologic investigations are unremarkable. Imaging with abdominopelvic U/S and CT-scan showed a predominantly cystic, hypo attenuating right sided pelvic mass with narrow elongated attachment to pancreatic tail and absent spleen in its normal position. CT also showed multiple different sized purely cystic lesions all over both kidneys and the pancreas compatible with AD polycystic kidney and pancreatic disease.

With a diagnosis of wandering possibly infarcted spleen, she underwent laparotomy, the finding being a fully infarcted spleen located on the right half of the upper pelvis with twisted pedicle and dense adhesions to the adjacent distal ileum and colon. Release of adhesions and splenectomy was done. Her post-operative course was uneventful.

Wandering spleen is a rare clinical condition that needs to be included in the list of differential diagnosis in patients presenting with lower abdominal and pelvic masses. As we have learnt from our case, a high index of suspicion is required to detect it early and intervene by doing splenopexy and thereby avoiding splenectomy and its related complications.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

Wandering spleen is a rare clinical entity characterized by hypermobility of the spleen as a result of absence or abnormal laxity of its suspensory ligaments which in turn can be congenital or precipitated by a number of risk factors like repeated pregnancy, trauma, surgery or connective tissue disorder. The spleen therefore migrates from its normal left hypochondriac position, to other parts of the peritoneal cavity especially the pelvis [ 3 ]. Since the first case report in 1667, there have been less than 600 cases reported in the literature so far [ 1 , 3 ].

Wandering spleen can have different clinical presentations ranging from asymptomatic incidental finding on imaging to features of acute abdomen as a result of complete torsion of the pedicle and total infarction of the spleen or complete obstruction of adjacent hollow viscus due to pressure effect. Less dramatic presentation includes chronic lower abdominal pain, swelling and symptoms of partial obstruction of bowel especially of the colon [ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 ].

Diagnosis is confirmed by imaging usually abdominal ultrasound or CT which reveals that the spleen is absent from its normal anatomical position but seen somewhere else in the new location within the peritoneal cavity [ 3 , 9 , 10 ]. Once diagnosed, surgical intervention is required either by splenopexy or splenectomy depending on the viability of the organ [ 3 , 5 ] and can be done laparoscopically or by laparotomy.

Owing to its rarity, a high index of suspicion is required and this condition should always be considered as a possible differential diagnosis in patients presenting with lower abdominal swelling and pain. We present this case to share our experience in diagnosing and managing such a rare pathology and once again bring it to the attention of fellow clinicians handling this sort of abdominal conditions.

Case summary

Our patient is a 39 years old female Primi-para Ethiopian, who presented with lower abdominal dull aching pain of one-year duration which got worse over the last few months associated with right lower abdominal swelling, easy fatigability, LGIF, loss of appetite and weight. She is a known case of RVI on HAART for the past 18yrs and hypertensive for the last 8 years for which she was taking enalapril and atenolol. Her only child was delivered by C/section 10 years ago.

On examination , she looked chronically sick with her vitals in the normal range. The abdomen was flat with a lower midline surgical scar and a visible round mass on the right paraumblical and lower quadrant areas. The mass was well defined, smooth surfaced, slightly tender and mobile (Fig. 1 —black arrow).

Black arrow shows the splenic mass, red arrow shows the stomach, cyan arrow shows previous CS scar

Her hematologic tests revealed WBC of 8.7 × 103, Hgb of 12.3 and PLT count of 544 × 10 3 . Serum electrolyte and liver function tests were all in the normal range. Creatinine was 1.4 mg/dl.

Abdominal ultrasound

Multiple bilateral renal, liver and pancreatic cysts. An ehcocomplex mainly hypoechoic, 13 cmx8cm well defined right sided abdomino-pelvic mass, with absent color Doppler flow. Spleen was not visualized in its normal anatomic site.

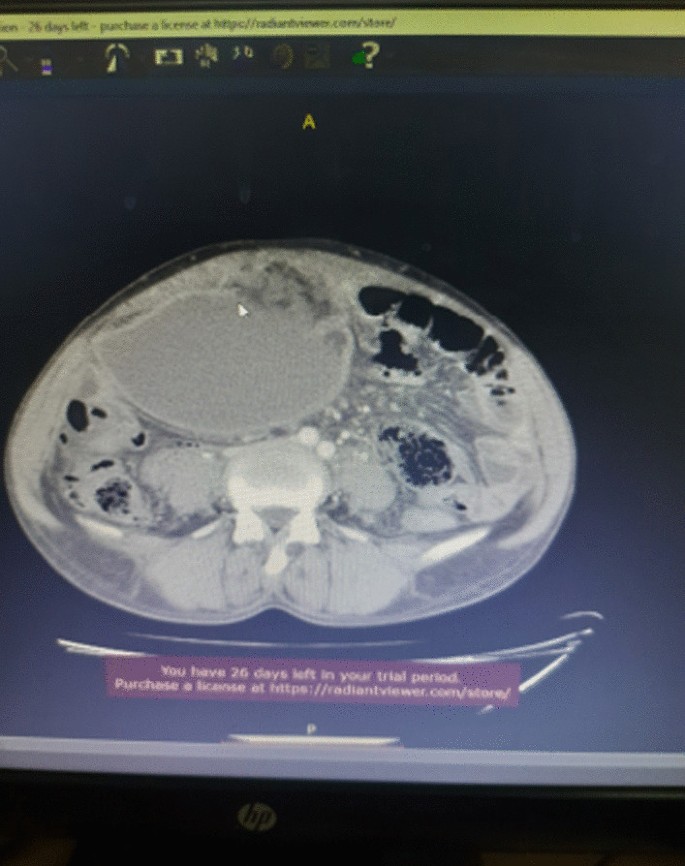

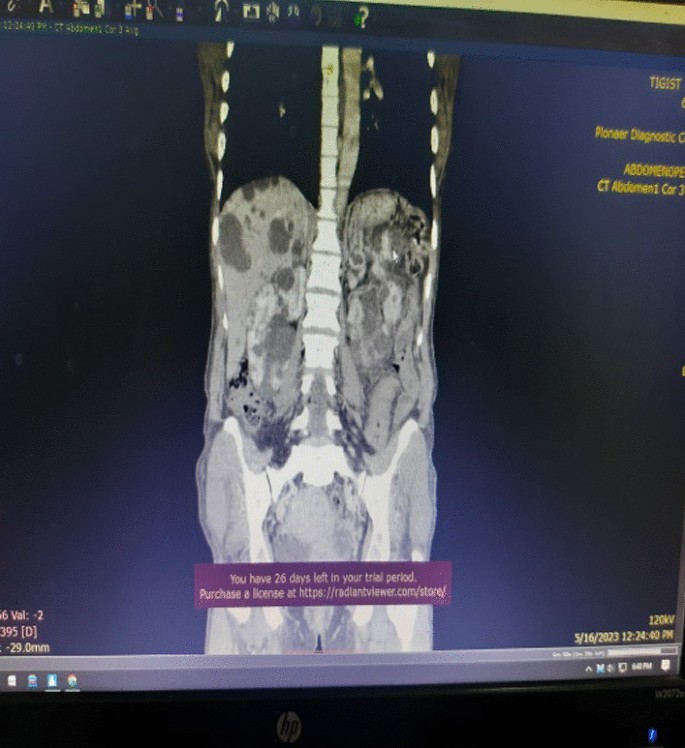

Contrast enhanced abdomino-pelvic CT

Described the mass as a hypoattenuating, well circumscribed lesion with no contrast enhancement located at right abdomino pelvic cavity (Fig. 2 ). Its long torsed pedicle could be traced to the region of the tail of the pancreas and the spleen was missing from its normal location. (Fig. 3 ) Majority of the renal parenchyma is almost replaced with different sized cystic lesions with imperceptible wall causing bilateral renal enlargement. (Fig. 3 ) The liver and the pancreas too is filled with similar cysts. The portal vein were not visualized and replaced by periportal enlarged collateral vessels. (Figs. 3 , 4 ).

Infarcted spleen

Absent spleen in the splenic fossa

Spleen seen in the abdomino-pelvic cavity

With a diagnosis of wandering spleen located in the right abdomino pelvic region with torsion of the pedicle and infarction, she was admitted and underwent laparotomy. Intraoperatively, dense adhesion encountered between the anterior abdominal wall, omentum, the wandering spleen and small bowel. The spleen was whitish, distended and grossly infarcted with its long stalk torsed > 360°. (Fig. 5 ) Adhesions were gently released and splenectomy done. The splenic mass was sent for biopsy.

The intra-op picture of our patient upon exploration

She was discharged on the 3rd postoperative day and her post-operative course was uneventful. She was seen after a month on follow up clinic with no report of complication. Her biopsy result showed splenic tissue. She got her pentavelant vaccine on the third week.

Wandering spleen is a rare clinical entity characterized by splenic hypermobility from its left hypochondriac position to any other abdominal or pelvic position caused by absent or abnormal laxity of the suspensory ligaments [ 1 , 2 ].

The first case of wandering spleen was reported by Von Horne in 1667. So far less than 600 cases are reported world wide [ 1 , 3 ].

Anatomically a normal spleen is found in the left hypochondriac region suspended by ligaments to the stomach, kidney, pancreas, colon and left hemi-diaphram by the gastrosplenic, splenorenal, pancreaticosplenic, splenocolic, splenophreni ligaments and presplenic folds [ 1 ]. Our patient presented with RLQ palpable abdominal mass which is against the commonest presentation being in the LLQ of the abdomen (Fig. 1 ).

It could result from either a developmental failure of the embryonic septum transversum to fuse properly with the posterior abdominal wall which results in absent/lax ligaments [ 4 ] or from acquired conditions that result in lax suspensory ligaments as in pregnancy or connective tissue disorders [ 3 ]. The spleen is found in any quadrant of the abdomen or the pelvis though mostly in the left quadrants attached only by a long and loose vascular pedicle. Our patient presented with RLQ mass.

It is mostly seen in multiparous women [ 4 ] though the incidence is found to be nearly equal in both sexes in the prepubertal age group [ 3 ]. Our patient was a Para 1 mother and presented with 01 year history of abdominal pain which got worse in the past 06 months. Otherwise she had no any other pressure symptoms. She had visible umbilical area mass which was mobile up on examination

Wandering spleen can have different presentation ranging from asymptomatic incidental finding on imaging or upon surgical exploration for other surgical conditions to a presentation that mimics acute abdomen [ 3 , 5 ]. Mostly it presents as an on and of type acute/ subacute non-specific abdominal pain due to torsion and spontaneous de-torsion of the loose splenic pedicle [ 3 , 4 ]. This chronic torsion results in congestion and splenomegaly [ 3 , 5 ]. Hence patients could have palpable mobile mass [ 6 ] which is the typical presentation of this patient. The other presentations are usually related to the mass effect of the enlarged spleen and patients could present with GOO, bowel obstruction, pancreatitis and urinary symptoms [ 3 , 6 ].

In some cases it is reported to be associated with some other disorders like gastric volvulus [ 7 ] and distal pancreatic volvulus [ 8 ].

Ultrasound is one of the imaging modalities to investigate patients whom we suspect had wandering spleen. It usually shows absent spleen in the splenic fossa and a comma shaped spleen in the abdomen or pelvis [ 9 ]. Doppler study might help us see the vascular condition and ads up to a better preoperative plan. CT scan shows absence of the spleen in the left upper quadrant, ovoid or comma-shaped abdominal mass, enlarged spleen, a whirled appearance of non-enhancing splenic vessels and signs of splenic hypo-perfusion: homogenous or heterogeneous decreased enhancement depending on the degree of infarction [ 3 , 9 , 10 ].

Our patient was scanned with US and showed 13*8 cm large midline abdomino-pelvic well defined oval mass which was predominantly solid with areas of cystic component with absent color Doppler flow. Otherwise the spleen was not visualized in the splenic fossa. Bilateral kidney and liver has multiple different sized cystic lesions. With this image Abdomino-pelvic CT was done and shows spleen is located in the lower abdomen and appears to have torsed vascular pedicle and the whole splenic parenchyma is hypodense and no enhancement seen. Majority of the renal parenchyma is almost replaced with different sized cystic lesions with imperceptible wall causing bilateral renal enlargement. The whole liver is filled with cystic lesions with imperceptible wall. The portal veins were not visualized and replaced by periportal enlarged collateral vessels (Figs. 6 , 7 ).

Usually surgical management is the rule once a patient is diagnosed with wandering spleen [ 3 , 5 ]. Most patients; 65% as reported in some studies will have torsion of the vascular pedicle at some point of their life [ 5 , 6 ]. Hence splenopexy or splenectomy shall be considered when a wandering spleen is found incidentally up on surgical exploration for some other purposes [ 6 ]. Complicated wandering spleen like infarcted, signs of hypersplenism, huge in size and splenic vein thrombosis needs splenectomy while others can be managed with splenopexy [ 3 , 5 , 6 ]. Nowadays though laparoscopic technique is the gold standard, open technique can be used for splenopexy and splenectomy [ 3 , 5 ].

Partial infraction of a wandering spleen might necessitate partial splenectomy and splenopexy or splenectomy and splenic implantation [ 6 , 11 ].

The spleen might get fixed by different methods [ 8 , 9 ].

Simple splenic fixation involves simple tacking the splenic capsule to the peritoneum

Retroperitoneal pouch splenopexy- Tissue [ 11 , 12 ]/Mesh splenopexy (sandwich technique) [ 13 ].

Omental and peritoneal pouch splenic fixation [ 14 ].

In our case, Spleen was absent from the normal anatomic splenic fossa and the spleen in the abdomino-pelvic area looks infarcted. Hence she was managed with splenectomy and the patient was extubated on table and having a stable postoperative course .

Wandering spleen is a rare form of splenic pathology. Such a rare pathology presents commonly as an acute torsion with infarction. Spleen in the RLQ with chronic torsion and infarction is a very rare presentation for wandering spleen. In addition there is no report of such a presentation in a patient with AD-PCKD.

Recommendation

We recommend Clinicians to consider wandering spleen in their differential diagnosis in a patient presenting with RLQ abdominal mass and chronic abdominal pain.

Availability of supporting data

Data related with this case report is available at Addis ababa university, Tikur Ambesa Tertiary Hospital.

Abbreviations

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease

Blood pressure

Low grade intermittent fever

High active anti-retroviral therapy

Right lower quadrant

Retro viral infection

Hypertension

White blood cell count

Puranik AK, et al . Wandering spleen: a surgical enigma. Gastroenterol Rep. 2015;5:241.

Google Scholar

Evangelos K, et al . Wandering spleen volvulus: a case report and literature review of this diagnostic challenge. Am J Case Rep. 2020;21: e925301.

Jawad M. Wandering spleen: a rare case from the emergency department. Cureus. 2023;15(1): e33246.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ayaz UY, et al . Wandering spleen in a child with symptoms of acute abdomen. Med Ultrasonogr. 2012;14:64.

Masroor M, Sarwari MA. Torsion of the wandering spleen as an abdominal emergency: a case report. BMC Surg. 2021;21:289.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Blouhos K, et al . Ectopic spleen: an easily identifiable but commonly undiagnosed entity until manifestation of complications. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;8:451–4.

Article Google Scholar

Uc A. Gastric volvulus and wandering spleen. Am J Gastroenrterol. 1998;93:1146–8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Alqadi GO, Saxena AK. Is laparoscopic approach for wandering spleen in children an option? J Min Access Surg. 2019;15:93.

Awan M, et al . Torsion of wandering spleen treated by laparoscopic splenopexy. Int J Surgery Case Rep. 2019;62:58.

Taori K, et al . Wandering spleen with torsion of vascular pedicle: early diagnosis with multiplaner reformation technique of multislice spiral CT. Abdom Imaging. 2004;29:09428925.

Fonseca AZ, et al . Torsion of a wandering spleen treated with partial splenectomy and splenopexy. J Emerg Med. 2013;44:e33.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Seashore JH, McIntosh S. Elective splenopexy for wandering spleen. J Pediatr Surg. 1990;25:270–2.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Soleimani M. Surgical treatment of patients with wandering spleen: report of six cases with a review of the literature. Surg Today. 2007;37:261.

Peitgen K. Laparoscopic splenopexy by peritoneal and omental pouch construction for intermittent splenic torsion (“wandering spleen”). Surg Endosc. 2001;15:413.

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the managing team of this patient including all the ward staffs who played a great role in the peri-operative management of this patient. We also appreciate the support of our consultants, residents and member of the department of surgery and HPB unit. Our kind gratitude goes to the family of this patient for their unreserved support in post-operative period that helped for the fast recovery of this patient

Funding is not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Addis Ababa University, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Yitagesu aberra shibiru, Sahlu wondimu & Wassie almaw

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Dr. Yitagesu Aberra, Main author of this case report, is an HPB surgery fellow in the department of surgery, college of health science, Addis Ababa University who was the leading surgeon in the management of this patient. Dr. Sahlu Wendimu is an HPB surgery subspecialist and Assistant professor of General Surgery who was the consultant in duty during the management of this patient. Dr.Wassie Almaw is a 2nd year pediatric surgery resident attaching at HPB surgery unit who took part in the management of this patient.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Yitagesu aberra shibiru .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethical clearance is not applicable but we took oral and written consent from the patient for case presentation and publication.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Competing interests

There is no competing interest in this case presentation.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.