Difference Between Case Study And Narrative Research

- Success Team

- January 19, 2023

Top-Rated AI Meeting Assistant With Incredible ChatGPT & Qualitative Data Analysis Capabilities

Join 150,000+ individuals and teams who rely on speak ai to capture and analyze unstructured language data for valuable insights. streamline your workflows, unlock new revenue streams and keep doing what you love..

Get a 7-day fully-featured trial!

Research is an important part of any organization or business. There are two main types of research: case studies and narrative research. Both are valuable tools for gathering and analyzing information, but they have some important differences. Understanding the difference between case study and narrative research can help you select the best research method for your particular project.

What is Case Study Research?

Case study research is a type of qualitative research that focuses on a single case, or a small number of cases, to examine in depth. It seeks to understand a phenomenon by examining the context of the case and looking at the experiences, perspectives, and behavior of the people involved. Case study research is often used to explore complex social phenomena, such as poverty, health, education, and social change.

What is Narrative Research?

Narrative research is also a type of qualitative research that focuses on understanding how people make sense of their experiences. It involves collecting and analyzing stories, or narratives, from participants. These stories can be collected through interviews, focus groups, or other data collection techniques. By examining the stories in detail, researchers can gain insights into how people think about and make sense of the world around them.

Differences Between Case Study and Narrative Research

The most important differences between case study and narrative research are the focus and the type of data collected. Case studies focus on a single case or a small number of cases, while narrative research focuses on understanding how people make sense of their experiences. Case studies typically rely on quantitative data, such as surveys and measurements, while narrative research relies on qualitative data, such as interviews, stories, and observations.

Which is Better?

The answer to this question depends on the research question and the type of data needed to answer it. If the goal is to understand a single case in depth, then a case study is the best approach. If the goal is to understand how people make sense of their experiences, then narrative research is the best approach. In some cases, it may be beneficial to use a combination of both approaches.

Case study and narrative research are both valuable tools for gathering and analyzing information. Understanding the difference between the two can help you select the best research method for your particular project. While case studies are useful for understanding a single case in depth, narrative research is better for understanding how people make sense of their experiences. In some cases, it may be beneficial to use a combination of both approaches.

How To Use The Best Large Language Models For Research With Speak

Step 1: Create Your Speak Account

To start your transcription and analysis, you first need to create a Speak account . No worries, this is super easy to do!

Get a 7-day trial with 30 minutes of free English audio and video transcription included when you sign up for Speak.

To sign up for Speak and start using Speak Magic Prompts, visit the Speak app register page here .

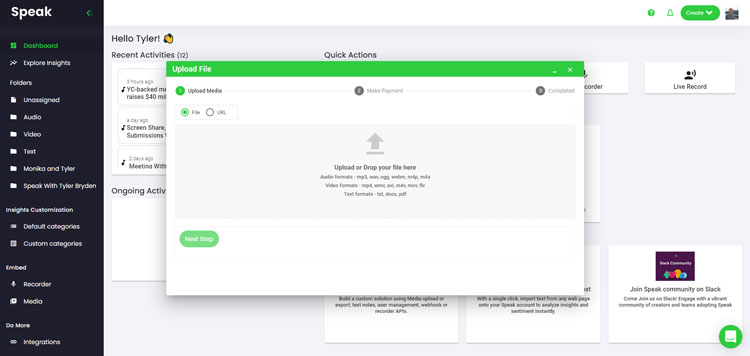

Step 2: Upload Your Research Data

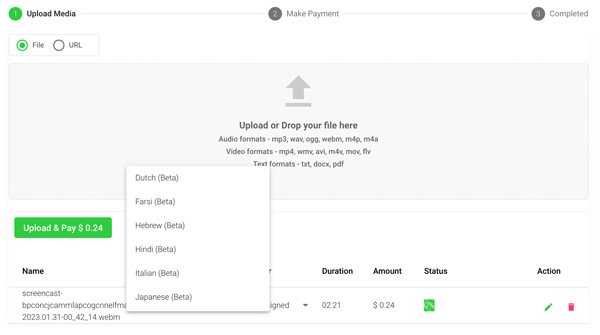

We typically recommend MP4s for video or MP3s for audio.

However, we accept a range of audio, video and text file types.

You can upload your file for transcription in several ways using Speak:

Accepted Audio File Types

Accepted video file types, accepted text file types, csv imports.

You can also upload CSVs of text files or audio and video files. You can learn more about CSV uploads and download Speak-compatible CSVs here .

With the CSVs, you can upload anything from dozens of YouTube videos to thousands of Interview Data.

Publicly Available URLs

You can also upload media to Speak through a publicly available URL.

As long as the file type extension is available at the end of the URL you will have no problem importing your recording for automatic transcription and analysis.

YouTube URLs

Speak is compatible with YouTube videos. All you have to do is copy the URL of the YouTube video (for example, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qKfcLcHeivc ).

Speak will automatically find the file, calculate the length, and import the video.

If using YouTube videos, please make sure you use the full link and not the shortened YouTube snippet. Additionally, make sure you remove the channel name from the URL.

Speak Integrations

As mentioned, Speak also contains a range of integrations for Zoom , Zapier , Vimeo and more that will help you automatically transcribe your media.

This library of integrations continues to grow! Have a request? Feel encouraged to send us a message.

Step 3: Calculate and Pay the Total Automatically

Once you have your file(s) ready and load it into Speak, it will automatically calculate the total cost (you get 30 minutes of audio and video free in the 7-day trial - take advantage of it!).

If you are uploading text data into Speak, you do not currently have to pay any cost. Only the Speak Magic Prompts analysis would create a fee which will be detailed below.

Once you go over your 30 minutes or need to use Speak Magic Prompts, you can pay by subscribing to a personalized plan using our real-time calculator .

You can also add a balance or pay for uploads and analysis without a plan using your credit card .

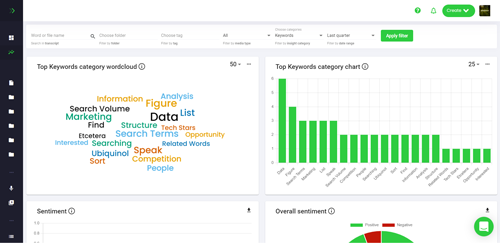

Step 4: Wait for Speak to Analyze Your Research Data

If you are uploading audio and video, our automated transcription software will prepare your transcript quickly. Once completed, you will get an email notification that your transcript is complete. That email will contain a link back to the file so you can access the interactive media player with the transcript, analysis, and export formats ready for you.

If you are importing CSVs or uploading text files Speak will generally analyze the information much more quickly.

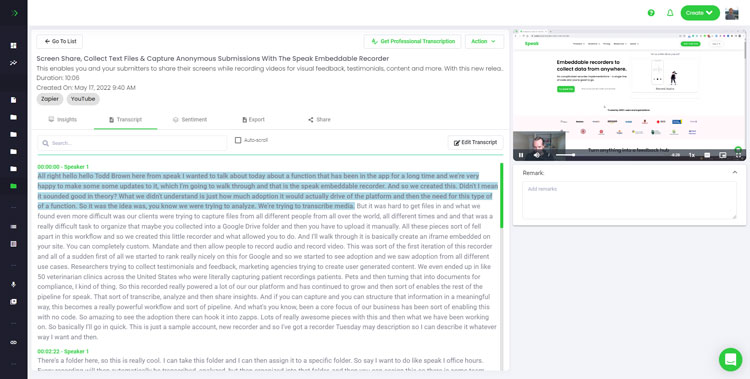

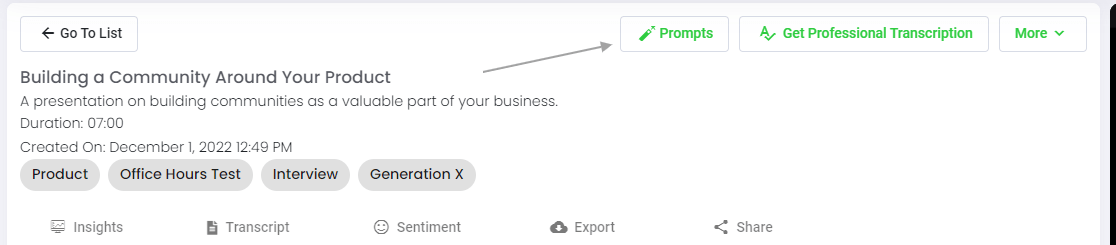

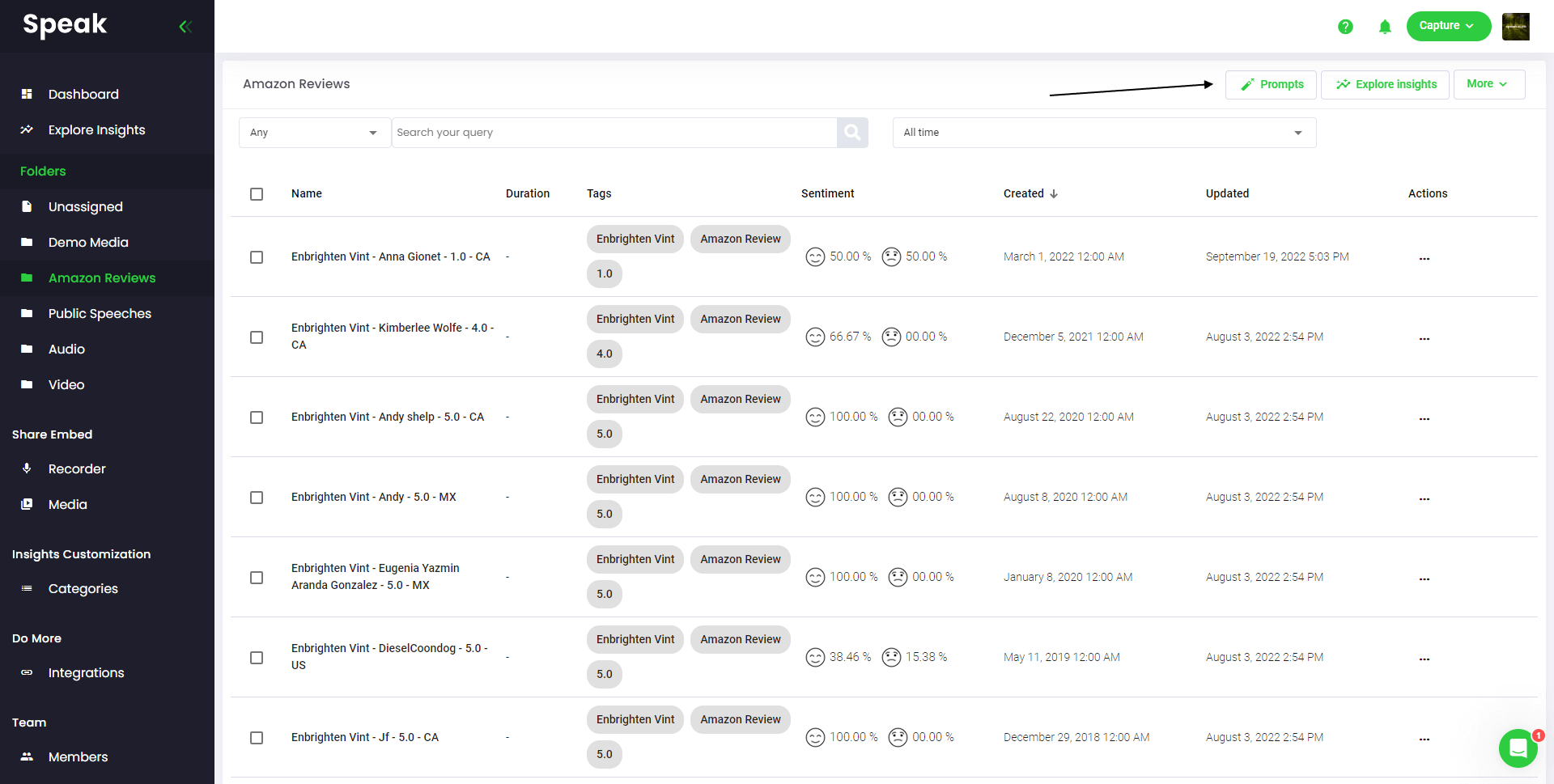

Step 5: Visit Your File Or Folder

Speak is capable of analyzing both individual files and entire folders of data.

When you are viewing any individual file in Speak, all you have to do is click on the "Prompts" button.

If you want to analyze many files, all you have to do is add the files you want to analyze into a folder within Speak.

You can do that by adding new files into Speak or you can organize your current files into your desired folder with the software's easy editing functionality.

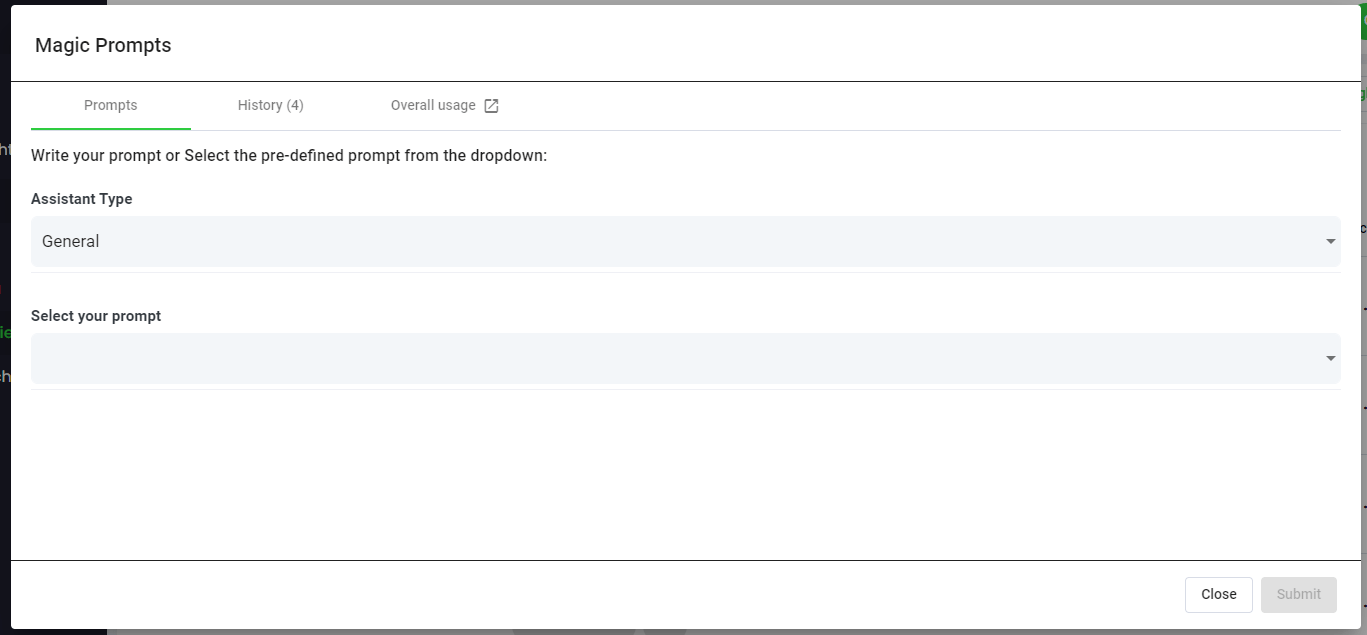

Step 6: Select Speak Magic Prompts To Analyze Your Research Data

What are magic prompts.

Speak Magic Prompts leverage innovation in artificial intelligence models often referred to as "generative AI".

These models have analyzed huge amounts of data from across the internet to gain an understanding of language.

With that understanding, these "large language models" are capable of performing mind-bending tasks!

With Speak Magic Prompts, you can now perform those tasks on the audio, video and text data in your Speak account.

Step 7: Select Your Assistant Type

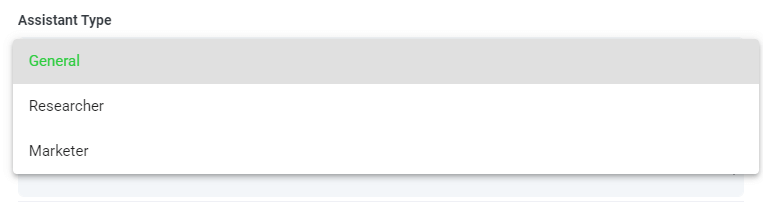

To help you get better results from Speak Magic Prompts, Speak has introduced "Assistant Type".

These assistant types pre-set and provide context to the prompt engine for more concise, meaningful outputs based on your needs.

To begin, we have included:

Choose the most relevant assistant type from the dropdown.

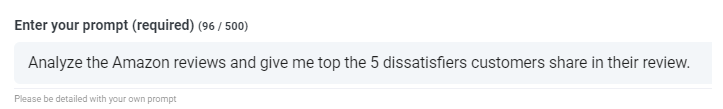

Step 8: Create Or Select Your Desired Prompt

Here are some examples prompts that you can apply to any file right now:

- Create a SWOT Analysis

- Give me the top action items

- Create a bullet point list summary

- Tell me the key issues that were left unresolved

- Tell me what questions were asked

- Create Your Own Custom Prompts

A modal will pop up so you can use the suggested prompts we shared above to instantly and magically get your answers.

If you have your own prompts you want to create, select "Custom Prompt" from the dropdown and another text box will open where you can ask anything you want of your data!

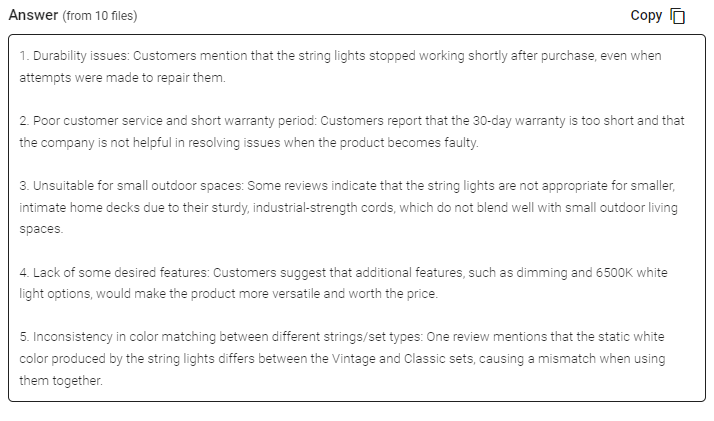

Step 9: Review & Share Responses

Speak will generate a concise response for you in a text box below the prompt selection dropdown.

In this example, we ask to analyze all the Interview Data in the folder at once for the top product dissatisfiers.

You can easily copy that response for your presentations, content, emails, team members and more!

Speak Magic Prompts As ChatGPT For Research Data Pricing

Our team at Speak Ai continues to optimize the pricing for Magic Prompts and Speak as a whole.

Right now, anyone in the 7-day trial of Speak gets 100,000 characters included in their account.

If you need more characters, you can easily include Speak Magic Prompts in your plan when you create a subscription.

You can also upgrade the number of characters in your account if you already have a subscription.

Both options are available on the subscription page .

Alternatively, you can use Speak Magic Prompts by adding a balance to your account. The balance will be used as you analyze characters.

Completely Personalize Your Plan 📝

Here at Speak, we've made it incredibly easy to personalize your subscription.

Once you sign-up, just visit our custom plan builder and select the media volume, team size, and features you want to get a plan that fits your needs.

No more rigid plans. Upgrade, downgrade or cancel at any time.

Claim Your Special Offer 🎁

When you subscribe, you will also get a free premium add-on for three months!

That means you save up to $50 USD per month and $150 USD in total.

Once you subscribe to a plan, all you have to do is send us a live chat with your selected premium add-on from the list below:

- Premium Export Options (Word, CSV & More)

- Custom Categories & Insights

- Bulk Editing & Data Organization

- Recorder Customization (Branding, Input & More)

- Media Player Customization

- Shareable Media Libraries

We will put the add-on live in your account free of charge!

What are you waiting for?

Refer Others & Earn Real Money 💸

If you have friends, peers and followers interested in using our platform, you can earn real monthly money.

You will get paid a percentage of all sales whether the customers you refer to pay for a plan, automatically transcribe media or leverage professional transcription services.

Use this link to become an official Speak affiliate.

Check Out Our Dedicated Resources📚

- Speak Ai YouTube Channel

- Guide To Building Your Perfect Speak Plan

Book A Free Implementation Session 🤝

It would be an honour to personally jump on an introductory call with you to make sure you are set up for success.

Just use our Calendly link to find a time that works well for you. We look forward to meeting you!

Top-Rated AI Meeting Assistant With Incredible ChatGPT & Qualitative Data Analysis Capabilities

Save 99% of your time and costs!

Use Speak's powerful AI to transcribe, analyze, automate and produce incredible insights for you and your team.

Qualitative Research in Corporate Communication

A blogs@baruch site, chapter 4: five qualitative approaches to inquiry.

In this chapter Creswell guides novice researchers (us) as we work through the early stages of selecting a qualitative research approach. The text outlines the origins, uses, features, procedures and potential challenges of each approach and provides a great overview. Why identify our approach to qualitative inquiry now? To offer a way of organizing our ideas and to ground them in the scholarly literature (69). The author includes a chart on page 104 that provides a convenient comparison of major features.

The 5 approaches are NARRATIVE RESEARCH, PHENOMENOLOGY, GROUNDED RESEARCH, ETHNOGRAPHY, and CASE STUDY.

NARRATIVE RESEARCH

In contrast to the other approaches, narrative can be a research method or an area of study in and of itself. Creswell focuses on the former, and defines it as a study of experiences “as expressed in lived and told stories of individuals” (70). This approach emerged out of a literary, storytelling tradition and has been used in many social science disciplines.

Narrative researchers collect stories, documents, and group conversations about the lived and told experiences of one or two individuals. They record the stories using interview, observation, documents and images and then report the experiences and chronologically order the meaning of those experiences. Other defining features are available on p. 72.

These are the primary types of narrative:

- Biographical study, writing and recording the experiences of another person’s life.

- Autoethnography, in which the writing and recording is done by the subject of the study (e.g., in a journal).

- Life history, portraying one person’s entire life.

- Oral history, reflections of events, their causes and effects.

For all of the research approaches, Creswell first recommends determining if the particular approach is an appropriate tool for your research question. In this case, narrative research methodology doesn’t follow a rigid process but is described as informal gathering of data.

The author provides recommendations for methodologies on pps 74-76 and introduces two interesting concepts unique to narrative research: 1) Restorying is the process of gathering stories, analyzing them for key elements, then rewriting (restorying) to position them within a chronological sequence. 2) Creswell describes a collaboration that occurs between participants and researchers during the collection of stories in which both gain valuable life insight as a result of the process.

Narrative research involves collecting extensive information from participants; this is its primary challenge. But ethical issues surrounding the stories may present weightier difficulties, such as questions of the story’s ownership, how to handle varied impressions of its veracity, and managing conflicting information. For further reading on the activities of narrative researchers Creswell recommends Clandinin and Connelly’s Narrative Inquiry (2000).

PHENOMENOLOGY

Phenomenology is a way to study an idea or concept that holds a common meaning for a small group (3-15) of individuals. The approach centers around lived experiences of a particular phenomenon, such as grief, and guides researchers to distill individual experiences to an essential concept. Phenomenological research generally hones in on a single concept or idea in a narrow setting such as “professional growth” or “caring relationship.”

The evolution of phenomenology from its philosophical roots with Heidegger’s and Sartre’s writing often emerges in current researchers’ exploration of the ideas (77). In contrast to the other four approaches, phenomenology’s tradition is important for establishing themes in the data. In addition to its relationship to philosophy, another key phenomenology feature is bracketing, a process by which the researcher identifies and sets aside any personal experience with the phenomena under study (78).

Phenomenology has two main subsets. Hermeneutic, by which a researcher first follows his/her own abiding concern or interest in a phenomenon; then reflects upon the essential themes that constitute the nature of this lived experience; describex the phenomenon; crafts an interpretation and finally mediates the different resultant meanings. The second type, transcendental, is more empirical and focused on a data analysis method outlined on page 80.

Cresswell favors a systematic methodology outlined by Moustakas (1994) in which participants are asked two broad, general questions: 1) What have you experienced in terms of the phenomenon? 2) What context of situations have typically influenced your experiences of the phenomenon? For some researchers, the author believes phenomenology may be too structured. He also mentions the additional challenge of identifying a sample of participants who share the same phenomenon experience.

Creswell recommends two sources for further reading on phenomenology: Moustakas’s Phenomenological Research Methods (1994) and van Manen’s Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy (1990).

GROUNDED THEORY RESEARCH

Grounded theory seeks to generate or discover a theory-a general explanation– for a social process, action or interaction shaped by the views of participants (p. 83). One key factor in grounded theory is that it does not come “off the shelf” but is “grounded” from data collected from a large sample. Creswell recommends an approach to this qualitative research prescribed by Corbin & Strauss (2007).

The author describes several defining features of grounded theory research (85). The first is that it focuses on a process or actions that has “movement” over time. Two examples of processes provided include the development of a general education program or “supporting faculty become good researchers.” An important aspect of data collection in this research is “memoing.” In which the researcher “writes down ideas as data are collected and analyzed,” usually from interviews.

Data collection is best be described as a “zigzag” process of going out to the field to gather information and then back to the office to analyze it and back out to the field. The author discusses various ways of coding the information into major categories of information (p. 86).

Another approach to grounded theory is that of Charmaz (2006). Creswell notes that Charmaz “places more emphasis on the views, values, belief, feelings, assumptions and ideologies of individuals than on the methods of research.” (p. 87)

The author states that this is a good design to use when there isn’t a theory available to “explain or understand a process.” (p. 88). Creswell further notes that the research question will focus on “understanding how individuals experience the process and identify steps in the process” that can often involve 20 to 60 interviews.

Some challenges in using this design is that the researcher must set aside “theoretical ideas or notions so that the analytic, substantive theory can emerge.” (p. 89) It is also important that the researcher understand that the primary outcome of this research is a “theory with specific components: a central phenomenon, causal conditions, strategies, conditions and context, and consequences,” according to Corbin & Strauss’ (p. 90). However, if a researcher wants a less structured approach the Charmaz (2006) method is recommended.

ETHNOGRAPHIC RESEARCH

Ethnography is a qualitative research design in which the unit of analysis is typically greater than 20 participants and focuses on an “entire culture-sharing group.” (Harris, 1968). In this approach, the “research describes and interprets the shared and learned patterns of values, behaviors, beliefs, and language” of the group. The method involves extended observations through “participant observation, in which the researcher is immersed in the day-to-day lives of the people and observes and interviews the group participants.” (p. 90).

Creswell notes that there is a lack of orthodoxy in ethnographic research with many pluralistic approaches. He lists a number of other researchers (p.91) but states that he draws on Fetterman’s (2009) and Wolcott’s (2008a) approaches in this text.

Some defining features of ethnographic research are listed on pages 91 and 92. They include that: it “focuses on developing a complex, complete description of the culture of a group, a culture-sharing group;” that ethnography however “is not the study of a culture, but a study of the social behaviors of an identifiable group of people;” that the group “has been intact and interacting for long enough to develop discernable working patterns,” and that ethnographers start with a theory drawn from “cognitive science to understand belief and ideas” or materialist theories (Marxism, acculturation, innovation, etc.)

Some types of ethnographies include “confessional ethnography, life history, autoethnography, feminist ethnography, visual ethnography,”etc., however, Creswell emphasizes two popular forms. The first is the realist ethnography-used by cultural anthropologists, it is “an objective account of a situation, typically written in the third-person point of view and reporting objectively on the information learned from participants.” (p. 93). The second is the critical ethnography in which the author advocates for groups marginalized in society (Thomas, 1993). This type of research is typically conducted by “politically minded individuals who seek through their research, to speak out against inequality and domination” (Carspecken & Apple, 1992). (p. 94).

The procedures for conducting an ethnography are listed on p. 94-96. One key element in these procedures is the gathering of information where the group works or lives through fieldwork (Wolcott, 2008a); and respecting the daily lives of these individuals at the site of study. Some key challenges in this type of research are that one must have an “understanding of cultural anthropology, the meaning of a social-cultural system, and the concepts typically explored by those studying cultures. Also, data collection requires a lot of time on the field. (p. 96)

CASE STUDY RESEARCH

In case study research, defined as the “the study of a case within a real-life contemporary context or setting” Creswell takes the perspective that such research “is a methodology: a type of design in qualitative research that may be an object of study, as well as a product of inquiry.” Further, case studies have bounded systems, are detailed and use multiple sources of information (p. 97). Creswell references the work of Stake (1995) and Yin (2009) because of their systematic handling of the subject.

The author draws attention to several features of the case study approach, but emphasizes a critical element “is to define a case that can be bounded or described within certain parameters, such as a specific place and time.” Other components of the research method include its intent-which may take the form of intrinsic case study or instrumental case study (p. 98); its reliance on in-depth understanding; and its utilization of case descriptions, themes or specific situations. Finally, researchers typically conclude case studies with “assertions” from their learning (p. 99).

The text touches on several types of case studies that can be differentiated by size, activity or intent and that can involve single or multiple cases (p.99). In instances of collective case study design where the researcher may use multiple case studies to examine one issue, the text recommends Yin (2009) logic of replication be used. Creswell goes on to point out that if the researcher wishes to generalize from findings, care needs to be taken to select representative cases. This could be useful, time-saving information for class members considering this method.

In outlining procedures for conducting a case study (p.100), Creswell recommends “that investigators first consider what type of case study is most promising and useful” and advocates cases that show different perspectives on a problem, process or event.” Data analysis can be holistic (considering the entire case) or embedded (using specific aspects of the case).

Some of the challenges of case study research are determining the scope of the research and deciding on the bounded system and determining whether to study the case itself or how the case illustrates an issue. In the instance of multiple cases, the author makes the somewhat counter intuitive assertion that “the study of more than one case dilutes the overall analysis” (p. 101).

THE FIVE APPROACHES COMPARED

Creswell gives an overview of the commonality of the five research methods (p. 102) before explaining key differences among more similar seeming types of research, e.g. narrative research, ethnography. Here the author underlines that “the types of data one would collect and analyze would differ considerably.” He uses the example of the study of a single individual to make his argument, recommending narrative research instead of ethnography, which has a broader scope and case study, which may involve multiple cases.

In considering differences, Creswell puts forth that the research methods accomplish divergent goals, have different origins and employ distinct methods of analyzing data – the author underlines the data analysis stage as being the most exaggerated point of difference (p. 103). The final product, “the result of each approach, the written report, takes shape from all the processes before it.

In Table 4.1 (p. 104) Creswell provides a framework table that contrasts the characteristics of the five qualitative approaches. Given its stated suitability for both “journal-article length study” and dissertation or book-length work, class members may find it a handy reference for the mini study assignment and beyond.

Tricia Chambers, Eric Lugo, Kathryn Lineberger

8 thoughts on “ CHAPTER 4: Five Qualitative Approaches to Inquiry ”

I plan to use Narrative Research in my paper. It would be nice if I can know some recording skills of group conversation. I agree, Hui! There were none detailed in this chapter though. ~KL Haha, guess I can get some from google then.

For the mini-study, I’m hoping to use narrative research. Initially, I was planning on it as well as content analysis for my thesis in the fall, but after reading this chapter, I have some more work to do! Phenomenology or grounded theory might be better suited for what I want to accomplish. Needless to say, this chapter review got me thinking!

It seems to me that my area of interest might be carried out best with an ethnographic study. Since I want to look at communicators in the performing arts industry, I think that fits the description of a culture sharing group. The method also seems to fit what I would hope to do for my study, observe participants in their workplace and conduct interviews.

However, I would like to look more into the idea of overlapping approaches because I think it would also be interesting to look at specific PR campaigns or marketing campaigns carried out by my participants and this would likely fall under the case-study approach.

This chapter is definitely most useful for the initial phase of the research paper. For my research, I want to look into understanding consumer behavior and specific aspects of a company’s behavior/marketing tactics (maybe CSR) that affects its brand perception (using Dole Food Company). In taking this direction for my study, I think I’m stuck somewhere between phenomenology or ethnographic research.

I think my research might align more with phenomenography, because I don’t know if I’ll exactly be looking into any specific subcultures as ethnographic research does.

This chapter definitely got me thinking about what I’d like to accomplish with my mini-study and later on my thesis. What I’ve been exposed to the most in the corporate communications program are case studies because they’re part of learning. Logically it seems that Phenomenology or Ethnographic research is where my research idea will lead me, but I’m still in the phase of getting a refined research question of out my bigger ideas. At least now I know the routes I can go.

I would like to know if the five categories of the attributes related to illness representation were defined through the research, or beforehand? You mention the researchers were able to use these attributes to formulate their hypothesis and I was wondering if it was defined by them then how would this effect results because I think I want to define some factors myself, but I don’t want to introduce any bias? Should I even worry about this?

Hi Sheena, you might ask the Chapter 5 team about this. ~KL

That was a great break down of the different types of studies presented in the book. This was very helpful to me as I was unsure of what type of study I was going to do, but after reading this summary I have a much better idea. I want to study putting loved ones in a nursing home versus seeking out home-based alternatives, and I think a phenomenological study is where I am leaning towards.

I feel strongly pulled to the phenomenological framework, even though it’s definition is causing me the most confusion! I Anti-corporate sentiment is a human experience, and I think it would be interesting to find a small group of anarchists or anti-capitalists or just young people who participated in the Occupy movement and understand their concept of this phenomena.

I will need to determine whether a phenomenological study allows for methods interpretation outside interviews or focus groups. I feel that much of what I am studying is a phenomenon perpetuated by the media, and I would like to incorporate content analysis and document research into my analysis.

Comments are closed.

Narrative Inquiry, Phenomenology, and Grounded Theory in Qualitative Research

- First Online: 27 October 2022

Cite this chapter

- Rabiul Islam 4 &

- Md. Sayeed Akhter 5

2632 Accesses

Narrative inquiry, phenomenology, and grounded theory are the basic types of qualitative research. This chapter discusses the three major types of qualitative research—narrative inquiry, phenomenology, and grounded theory. Firstly, this chapter briefly discusses the issue of qualitative research and types. Secondly, it offers a conceptual understanding of narrative inquiry, phenomenology, and grounded theory including their basic characteristics. Finally, the chapter provides an outline of how these three types of qualitative research are applied in the field.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Aspers, P. (2009). Empirical phenomenology: A qualitative research approach (The Cologne Seminars). Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology, 9 (2), 1–12.

Article Google Scholar

Birks, M., & Mills, J. (2015). Grounded theory: A practical guide . Sage.

Google Scholar

Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis . Thousand Oaks.

Chun Tie, Y., Birks, M., & Francis, K. (2019). Grounded theory research: A design framework for novice researchers. SAGE Open Medicine, 7 , 1–8.

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (2000). Narrative inquiry: Experience and story in qualitative research . Jossey-Bass.

Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2014). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory . Sage Publications.

Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions . Sage.

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative research . Pearson Education Inc.

Groenewald, T. (2004). A phenomenological research design illustrated. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3 (1), 42–55.

Husserl, E. (1970). Logical investigations (Vol. 1). Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd.

Josselson, R. (2010). Narrative research. In N. J. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopedia of research design (Vol. 1). Sage.

Lester, S. (1999). An introduction to phenomenological research . Stan Lester Developments.

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation . Jossey-Bass.

Nussbaum, M. C. (2000). Women and human development: The capabilities approach . Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Padilla-Díaz, M. (2015). Phenomenology in educational qualitative research: Philosophy as science or philosophical science. International Journal of Educational Excellence, 1 (2), 101–110.

Patton, M. Q. (2014). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice . Sage publications.

Rassi, F., & Shahabi, Z. (2015). Husserl’s phenomenology and two terms of Noema and Noesis. International Letters of Social and Humanistic Sciences, 53 , 29–34.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom . Oxford University Press.

Sloan, A., & Bowe, B. (2014). Phenomenology and hermeneutic phenomenology: The philosophy, the methodologies, and using hermeneutic phenomenology to investigate lecturers’ experiences of curriculum design. Quality & Quantity, 48 (3), 1291–1303.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Social Work, University of Rajshahi, Bangladesh and Macquarie School of Social Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, Australia

Rabiul Islam

Department of Social Work, University of Rajshahi, Rajshahi, Bangladesh

Md. Sayeed Akhter

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rabiul Islam .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Centre for Family and Child Studies, Research Institute of Humanities and Social Sciences, University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

M. Rezaul Islam

Department of Development Studies, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Niaz Ahmed Khan

Department of Social Work, School of Humanities, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa

Rajendra Baikady

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this chapter

Islam, R., Sayeed Akhter, M. (2022). Narrative Inquiry, Phenomenology, and Grounded Theory in Qualitative Research. In: Islam, M.R., Khan, N.A., Baikady, R. (eds) Principles of Social Research Methodology. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5441-2_8

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-5441-2_8

Published : 27 October 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-19-5219-7

Online ISBN : 978-981-19-5441-2

eBook Packages : Social Sciences

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO